Abstract

Patients and physicians may defer unrelated donor hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) as curative therapy due to mortality risk associated with the procedure. Therefore, it is important for physicians to know the current outcomes data when counseling potential candidates. To provide this information, we evaluated 15,059 unrelated donor HCT recipients between 2000-2009. We compared outcomes before and after 2005 for four cohorts: age <18 years with malignant diseases (N=1,920), 18-59 years with malignant diseases (N=9,575), ≥60 years with malignant diseases (N=2,194), and non-malignant diseases (N=1,370). Three-year overall survival in 2005-2009 was significantly better in all four cohorts (<18 years: 55% vs. 45%, 18-59 years: 42% vs. 35%, ≥60 years: 35% vs. 25%, non-malignant diseases: 69% vs. 60%, P<0.001 for all comparisons). Multivariate analyses in leukemia patients receiving HLA 7-8/8 matched transplants showed significant reduction in overall and non-relapse mortality in the first 1-year after HCT among patients transplanted in 2005-2009; however, risks for relapse did not change over time. Significant survival improvements after unrelated donor HCT have occurred over the recent decade and can be partly explained by better patient selection (e.g., HCT earlier in the disease course and lower disease risk), improved donor selection (e.g., more precise allele-level matched unrelated donors) and changes in transplant practices.

Keywords: Hematopoietic cell transplantation, unrelated donors, survival, treatment related mortality, National Marrow Donor Program

INTRODUCTION

Allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) using an unrelated donor is curative therapy for patients with high-risk hematologic diseases who need a transplant but lack a human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-identical sibling donor. Survival after unrelated donor HCT has nearly doubled since the first unrelated donor transplants in the late 1980's.1,2 Currently, 1-year survival of 60-70% can be expected for patients with high-risk acute leukemia who receive an unrelated donor HCT relatively early in their disease course.3,4 For some diseases, survival after HLA-matched unrelated donor transplantation has been shown to be comparable to HCT using HLA-identical sibling donors.5-10 However, patient and physician perceptions of the risks and efficacy of unrelated donor transplantation may prevent some patients from being referred for this procedure, especially at an early stage when transplant outcomes are optimal.11,12 Several advances in transplantation technology and supportive care have occurred in recent years and a considerably larger number of HLA-matched unrelated donors are now available. Analyses of unrelated donor transplant outcomes in the contemporary period are lacking. To provide an upto-date analysis of the risks and benefits of this therapeutic option, we studied a large cohort of patients who underwent HCT between 2000 and 2009 facilitated by the National Marrow Donor Program (NMDP).

METHODS

Data Source

Data were obtained from the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research (CIBMTR), the research arm of the NMDP. Transplant centers in the NMDP network are required to submit patient outcomes data for all NMDP-facilitated unrelated donor transplants to the CIBMTR. Patients are followed longitudinally. Computerized checks for discrepancies, physicians’ review of submitted data, and on-site audits of participating centers ensure data quality and completeness. This study was performed in compliance with all applicable federal regulations pertaining to the protection of human research participants and under guidance of the NMDP Institutional Review Board.

Study Population

We selected our cohort to enable examination of trends in survival over a recent period that reflected current unrelated donor transplant practices. Thus, we included all NMDP-facilitated first unrelated donor transplants using peripheral blood stem cells (PBSC) or bone marrow (BM) between 2000 and 2009. The NMDP facilitated >90% of all unrelated donor HCT in the US during this time period.13 Umbilical cord blood recipients were excluded. Patients from all age groups and with any diagnosis were considered and our cohort consisted of recipients of myeloablative and non-myeloablative/reduced-intensity conditioning (NMA/RIC) regimens.

Statistical Analysis

We compared outcomes for two 5-year periods (2000-04 vs. 2005-09). Analyses were conducted for four separate groups stratified by age and diagnosis because of known differences in survival by these variables4: (1) age <18 years, malignant diseases, (2) age 18-59 years, malignant diseases, (3) age ≥60 years, malignant diseases, and (4) non-malignant diseases (all ages). The primary endpoint of our study, overall survival at 3-years, was selected as most deaths will have occurred by this time period.4 Non-relapse mortality (NRM), relapse, acute graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) and chronic GVHD were secondary endpoints.

Patient-, disease-, and transplantation-related characteristics were compared by using the Chi-square test for categorical variables and the Kruskal-Wallis test for continuous variables. Probability of overall survival was calculated with the Kaplan-Meier estimator and probabilities of NRM, relapse and GVHD were calculated using the cumulative incidence function.14,15 Relapse was considered a competing risk for NRM while death in remission was considered a competing risk for relapse. Where sample size permitted, we conducted additional subset analyses in more homogeneous populations that were defined based on variables that routinely affect unrelated donor HCT outcomes such as relapse risk, conditioning intensity and HLA match. To further enhance their utility for clinical decision making, whenever possible these subgroups were constructed to reflect common clinical scenarios.

We conducted multivariate analyses using Cox proportional hazards regression to better understand the contribution of changes in patient and disease characteristics as well as practice factors on survival, NRM and relapse.16 We minimized the impact of factors resulting from changes in the proportions of diseases transplanted and the introduction of high resolution DNA-based tissue typing that occurred during the time frame studied by restricting this analysis to a more homogenous subset of patients who had received 8/8 or 7/8 HLA-matched graft for selected malignant diseases (acute myeloid leukemia [AML], acute lymphoblastic leukemia [ALL], chronic myeloid leukemia [CML] or myelodysplastic syndromes [MDS], N=8,531). Models were constructed in two steps. The initial models were adjusted for patient and disease characteristics. Variables considered included patient age at HCT, gender, ethnicity/race, Karnofsky/Lansky performance score, cytomegalovirus serological status, coexisting diseases, diagnosis, time since diagnosis and disease risk. In the second step, variables that represented changes in transplant practices were introduced. These included HLA-match, graft type, conditioning intensity, GVHD prophylaxis regimens and use of T-cell depletion. Patient and disease characteristics noted to be significant in the first model remained significant in the subsequent model that adjusted for transplant practice factors. Results of this final model are presented. Potential risk factors were checked for proportional hazards by using a time-dependent covariate approach, and a stratified model was used when there were non-proportional hazards. First-order interactions between time period of transplantation and other variables were assessed. P-values are two-sided. Analyses were performed using SAS software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

Our final cohort consisted of 15,059 patients who had received their first unrelated donor HCT using either PBSC or BM between 2000 and 2009. There were 1,920 patients age <18 years with malignant diseases, 9,575 age 18-59 years with malignant diseases, 2,194 age ≥60 years with malignant diseases, and 1,370 with non-malignant diseases (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics by age, diagnosis and time period

| Characteristic | Age <18 years, malignant diseases | Age 18-59 years, malignant diseases | Age ≥ 60 years, malignant diseases | Non-malignant diseases | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000-04 | 2005-09 | P-value* | 2000-04 | 2005-09 | P-value* | 2000-04 | 2005-09 | P-value* | 2000-04 | 2005-09 | P-value* | |

| Number of recipients | 904 | 1016 | 3827 | 5748 | 410 | 1784 | 477 | 893 | ||||

| Number of centers | 97 | 103 | 138 | 152 | 76 | 115 | 83 | 133 | ||||

| Followup (months), median (range) | 91 (3-147) | 47 (4-78) | <0.001 | 95 (3-145) | 42 (3-84) | <0.001 | 76 (9-121) | 36 (3-82) | <0.001 | 82 (4-147) | 39 (2-85) | <0.001 |

| Recipient gender, N (%) | 0.90 | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.20 | ||||||||

| Female | 362 (40) | 410 (40) | 1618 (42) | 2557 (44) | 125 (30) | 628 (35) | 197 (41) | 337 (38) | ||||

| Male | 542 (60) | 606 (60) | 2209 (58) | 3191 (56) | 285 (70) | 1156 (65) | 280 (59) | 556 (62) | ||||

| Recipient race/ethnicity, N (%) | 0.06 | 0.003 | 0.80 | 0.58 | ||||||||

| White | 632 (70) | 694 (68) | 3324 (87) | 4896 (85) | 391 (95) | 1671 (94) | 328 (68) | 599 (67) | ||||

| Hispanic | 137 (15) | 178 (18) | 220 (6) | 356 (6) | 8 (2) | 41 (2) | 70 (15) | 131 (15) | ||||

| Black/African American | 85 (9) | 65 (6) | 167 (4) | 255 (4) | 6 (1) | 31 (2) | 41 (9) | 79 (9) | ||||

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 29 (3) | 39 (4) | 64 (2) | 104 (2) | 1 (<1) | 17 (1) | 28 (6) | 47 (5) | ||||

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 4 (<1) | 7 (1) | 6 (<1) | 23 (<1) | 0 | 1 (<1) | 1 (<1) | 8 (1) | ||||

| Other/multiple race | 10 (1) | 22 (2) | 22 (1) | 31(1) | 1 (<1) | 8 (<1) | 5 (1) | 18 (2) | ||||

| Declined/unknown | 7 (1) | 11 (1) | 24 (1) | 83 (1) | 3 (1) | 15 (1) | 4 (1) | 11 (1) | ||||

| Karnofsky/Lansky score at HCT, N (%) | 0.005 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.008 | ||||||||

| 90 to 100 | 691 (76) | 822 (81) | 2313 (60) | 3521 (61) | 236 (58) | 1031 (58) | 337 (71) | 675 (76) | ||||

| 10 to 80 | 115 (13) | 126 (12) | 1098 (29) | 1853 (32) | 120 (29) | 639 (36) | 101 (21) | 180 (20) | ||||

| Unknown | 98 (11) | 68 (7) | 416 (11) | 374 (7) | 54 (13) | 114 (6) | 39 (8) | 38 (4) | ||||

| Recipient CMV status, N (%) | 0.01 | 0.009 | 0.58 | 0.16 | ||||||||

| Negative | 504 (56) | 500 (49) | 1698 (44) | 2383 (41) | 137 (33) | 633 (36) | 220 (46) | 395 (44) | ||||

| Positive | 395 (44) | 507 (50) | 2097 (55) | 3300 (57) | 269 (66) | 1127 (63) | 246 (52) | 488 (55) | ||||

| Unknown | 5 (1) | 9 (1) | 32 (1) | 65 (1) | 4 (1) | 24 (1) | 11 (2) | 10 (1) | ||||

| Co-existing disease at HCT, N (%) | 269 (30) | 376 (37) | <0.001 | 1858 (49) | 3644 (63) | <0.001 | 296 (72) | 1398 (78) | 0.02 | 196 (41) | 443 (50) | 0.008 |

| Diagnosis, N (%) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.002 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| AML | 279 (31) | 290 (29) | 1409 (37) | 2412 (42) | 202 (49) | 884 (50) | - | - | ||||

| ALL | 383 (42) | 462 (45) | 667 (17) | 973 (17) | 18 (4) | 65 (4) | - | - | ||||

| CML | 85 (9) | 44 (4) | 620 (16) | 421 (7) | 20 (5) | 32 (2) | - | - | ||||

| Other leukemia | 26 (3) | 32 (3) | 230 (6) | 381 (7) | 38 (9) | 193 (11) | - | - | ||||

| MDS | 57 (6) | 99 (10) | 355 (9) | 634 (11) | 59 (14) | 293 (16) | - | - | ||||

| Myeloproliferative diseases | 39 (4) | 44 (4) | 98 (3) | 210 (4) | 20 (5) | 93 (5) | - | - | ||||

| NHL | 30 (3) | 38 (4) | 352 (9) | 622 (11) | 46 (11) | 211 (12) | - | - | ||||

| Hodgkin lymphoma | 1 (<1) | 3 (<1) | 24 (1) | 48 (1) | 0 | 3 (<1) | - | - | ||||

| Plasma cell disorders | - | - | 46 (1) | 33 (1) | 2 (<1) | 7 (<1) | - | - | ||||

| Other malignant diseases | 4 (<1) | 4 (<1) | 26 (1) | 14 (<1) | 5 (1) | 3 (<1) | - | - | ||||

| SAA | - | - | - | - | - | - | 186 (39) | 402 (45) | ||||

| Inherited erythrocyte disorders | - | - | - | - | - | - | 95 (20) | 137 (15) | ||||

| Inherited immune system disorders | - | - | - | - | - | - | 70 (15) | 177 (20) | ||||

| Inherited disorders of metabolism | - | - | - | - | - | - | 71 (15) | 59 (7) | ||||

| Histiocytic disorders | - | - | - | - | - | - | 43 (9) | 96 (11) | ||||

| Inherited platelet disorders | - | - | - | - | - | - | 10 (2) | 8 (1) | ||||

| Other non-malignant diseases | - | - | - | - | - | - | 2 (<1) | 14 (2) | ||||

| Disease risk, N (%)† | 0.03 | <0.001 | 0.04 | |||||||||

| Standard | 546 (60) | 644 (63) | 1632 (43) | 2810 (49) | 141 (34) | 700 (39) | - | - | ||||

| High | 278 (31) | 261 (26) | 1740 (45) | 2139 (37) | 198 (49) | 738 (41) | - | - | ||||

| Other | 80 (9) | 111 (11) | 455 (12) | 799 (14) | 71 (17) | 346 (19) | - | - | ||||

| Time from diagnosis to HCT (months), N (%) | 0.03 | <0.001 | 0.003 | |||||||||

| 0 to 6 | 259 (29) | 360 (35) | 862 (23) | 1779 (31) | 84 (20) | 519 (29) | - | - | ||||

| 6 to 12 | 195 (22) | 191 (19) | 1076 (28) | 1426 (25) | 136 (33) | 470 (26) | - | - | ||||

| 12 to 24 | 178 (20) | 189 (19) | 878 (23) | 1098 (19) | 77 (19) | 300 (17) | - | - | ||||

| >24 | 265 (29) | 271 (27) | 973 (25) | 1394 (24) | 111 (27) | 478 (27) | - | - | ||||

| Unknown | 7 (<1) | 5 (<1) | 38 (1) | 51(1) | 2 (<1) | 17 (<1) | - | - | ||||

| Product type, N (%) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.03 | ||||||||

| Bone marrow | 696 (77) | 682 (67) | 2021 (53) | 1244 (22) | 93 (23) | 234 (13) | 377 (79) | 658 (74) | ||||

| PBSC | 208 (23) | 334 (33) | 1806 (47) | 4504 (78) | 317 (77) | 1550 (87) | 100 (21) | 235 (26) | ||||

| Conditioning regimen, N (%)‡ | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| MA, no TBI | 93 (10) | 272 (27) | 739 (19) | 2118 (37) | 55 (13) | 417 (23) | 99 (21) | 243 (27) | ||||

| MA, TBI | 726 (80) | 659 (65) | 1912 (50) | 1935 (34) | 17 (4) | 55 (3) | 81 (17) | 48 (5) | ||||

| NMA/RIC, no TBI | 67 (7) | 67 (7) | 867 (23) | 1329 (23) | 212 (52) | 933 (52) | 140 (29) | 280 (31) | ||||

| NMA/RIC, TBI | 18 (2) | 18 (2) | 309 (8) | 365 (6) | 126 (31) | 379 (21) | 157 (33) | 322 (36) | ||||

| Unknown | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (<1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||||

| HLA match, N (%)$ | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| 8/8 allele level | 338 (37) | 604 (59) | 1705 (45) | 3890 (68) | 202 (49) | 1328 (74) | 193 (40) | 571 (64) | ||||

| 7/8 allele level | 174 (19) | 299 (29) | 735 (19) | 1274 (22) | 59 (15) | 308 (17) | 92 (19) | 220 (25) | ||||

| ≥ 6/8 Allele level | 162 (18) | 80 (8) | 426 (11) | 180 (3) | 26 (6) | 16 (1) | 86 (18) | 62 (7) | ||||

| Well-matched | 115 (13) | 23 (2) | 567 (15) | 295 (5) | 80 (20) | 98 (5) | 38 (8) | 27 (3) | ||||

| Partially-matched | 98 (11) | 8 (1) | 351 (9) | 97 (2) | 35 (9) | 28 (2) | 59 (12) | 12 (1) | ||||

| Mismatched | 17 (2) | 1 (<1) | 43 (1) | 12 (<1) | 8 (2) | 6 (<1) | 9 (2) | 1 (<1) | ||||

| Unknown | 0 (0) | 1 (<1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||||

| GVHD prophylaxis, N (%) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| TAC+MMF | 22 (2) | 78 (8) | 387 (10) | 1024 (18) | 65 (16) | 425 (24) | 20 (4) | 78 (9) | ||||

| TAC+MTX (no MMF) | 192 (21) | 281 (28) | 1402 (37) | 2881 (50) | 116 (28) | 692 (39) | 62 (13) | 171 (19) | ||||

| TAC+other (no MMF/MTX) | 44 (5) | 88 (9) | 213 (5) | 473 (8) | 32 (8) | 162 (9) | 29 (6) | 66 (7) | ||||

| CSA+MMF | 30 (3) | 62 (6) | 382 (10) | 342 (6) | 138 (34) | 249 (14) | 44 (9) | 99 (11) | ||||

| CSA+MTX (no MMF) | 417 (46) | 360 (35) | 1133 (30) | 602 (10) | 28 (7) | 87 (5) | 160 (34) | 282 (32) | ||||

| CSA+other (no MMF/ MTX) | 151 (17) | 70 (7) | 204 (5) | 106 (2) | 19 (5) | 42 (2) | 144 (30) | 145 (16) | ||||

| Other | 46 (5) | 74 (7) | 100 (3) | 309 (5) | 12 (3) | 124 (7) | 16 (3) | 35 (4) | ||||

| Unknown | 2 (<1) | 3 (<1) | 6 (<1) | 10 (<1) | 0 (0) | 3 (<1) | 2 (<1) | 17 (2) | ||||

| In-vivo T-cell depletion, N (%) | 370 (41) | 482 (47) | 0.02 | 985 (26) | 2086 (36) | <0.001 | 156 (38) | 820 (46) | 0.01 | 393 (82) | 742 (83) | 0.74 |

| Ex-vivo T-cell depletion | 167 (18) | 85 (8) | <0.001 | 271 (7) | 72 (1) | <0.001 | 5 (1) | 29 (2) | 0.83 | 120 (25) | 49 (5) | <0.001 |

Abbreviations: HCT – hematopoietic cell transplantation; CMV - cytomegalovirus; AML – acute myeloid leukemia; ALL – acute lymphoblastic leukemia; CML – chronic myeloid leukemia; MDS – myelodysplastic syndrome; NHL – non-Hodgkin lymphoma; SAA – severe aplastic anemia; PBSC – peripheral blood stem cells; MA – myeloablative; TBI – total body irradiation; NMA/RIC – non-myeloablative/reduced intensity; HLA – human leukocyte; GVHD – graft-versus-host disease; MMF – mycophenolate mofetil; MTX – methotrexate; TAC – tacrolimus; CSA – cyclosporine

Pearson chi-square test for categorical variables and Kruskal-Wallis test for continuous variables.

Standard risk diseases included AML or ALL in first or second complete remission, CML in first chronic phase and low-risk MDS. High risk diseases comprised of AML or ALL in third or greater complete remission, relapse or primary induction failure, CML in second or greater chronic, accelerated or blast phase, high-risk MDS and NHL. All other diseases were classified under the other risk category.

Conditioning regimen intensity was classified according to CIBMTR criteria.23

HLA-matching status was classified as well matched, partially matched, or mismatched in patients for whom high-resolution HLA typing was not available.24

Over the decade ranging from 2000 to 2009, there was a 141% increase in the number of unrelated donor HCT (963 HCT in 2000 compared to 2,318 HCT in 2009). The number of unrelated donor HCT increased in all four cohorts, but the most dramatic increase was seen in the age ≥60 years malignant disease cohort (an increase from 33 transplants in 2000 to 574 transplants in 2009), reflecting the introduction and increased utilization of NMA/RIC regimens.

Patient, donor and transplant practices evolved during the observation period (Table 1). After 2005, patients were less likely to have high risk disease and more likely to receive their transplant within six months of diagnosis. Donors were more likely to provide PBSC as a graft source, especially in patients 18-59 years with malignant disease. The proportion of donors who were matched to the patient for the eight most clinically relevant HLA loci (A, B, C and DR) increased significantly. More patients transplanted in the latter time period had co-existing diseases/comorbidities at the time of transplantation. Transplant practices also evolved. First, after 2005, patients were more likely to receive less toxic, non-total body irradiation (TBI) conditioning regimens. Second, GVHD prophylaxis choices shifted; the use of cyclosporine-based GVHD prophylaxis declined coincident with increased use of tacrolimus-based GVHD prophylaxis. Simultaneously, in-vivo T-cell depletion increased, especially for malignant diseases, while use of ex-vivo T-cell depletion declined over time.

Outcomes in Patients Age <18 Years with Malignant Diseases

Three-year probabilities of survival, NRM and relapse were significantly better after 2005 in children with malignant disease (Table 2, Figure 1). The 10% absolute improvement in 3-year survival (45% to 55%, p<0.001) is explained by significant decreases in both NRM (27% to 21%, p<0.001) and relapse (33% to 27%, p=0.007). Because GVHD is the major cause of NRM, we tested for differences in the incidence of acute and chronic GVHD between the two time periods. The 100-day cumulative incidence of moderate to severe grade 2-4 acute GVHD (47% vs. 41%, p=0.01) and severe grade 3-4 acute GVHD (23% vs. 16%, p=0.001) was significantly lower in the more recent time period. The 2-year incidence of chronic GVHD increased (39% vs. 44%, p=0.03) but was not sufficient to offset the improvements in 3-year outcomes.

Table 2.

Comparison of univariate outcomes after unrelated donor hematopoietic cell transplantation between the two time periods

| Endpoint | Age <18 years, malignant diseases |

Age 18-59 years, malignant diseases |

Age ≥ 60 years, malignant diseases |

Non-malignant diseases |

||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000-04 | 2005-09 | P- value |

2000-04 | 2005-09 | P- value |

2000-04 | 2005-09 | P- value |

2000-04 | 2005-09 | P- value |

|||||||||

| N | Prob (95% CI) |

N | Prob (95% CI) |

N | Prob (95% CI) |

N | Prob (95% CI) |

N | Prob (95% CI) |

N | Prob (95% CI) |

N | Prob (95% CI) |

N | Prob (95% CI) |

|||||

| Overall survival (3-years) | 904 | 45 (42-49) | 1016 | 55 (52-58) | <0.001 | 3827 | 35 (33-37) | 5748 | 42 (41-44) | <0.001 | 410 | 25 (21-30) | 1784 | 35 (33-37) | <0.001 | 477 | 60 (55-64) | 893 | 69 (66-72) | <0.001 |

| Non-relapse mortality* (3-years) | 872 | 27 (25-30) | 973 | 21 (18-23) | <0.001 | 3511 | 37 (35-39) | 5424 | 28 (27-29) | <0.001 | 378 | 35 (30-40) | 1711 | 31 (29-33) | 0.19 | -- | -- | |||

| Relapse* (3-years) | 872 | 33 (30-36) | 973 | 27 (24-30) | 0.007 | 3511 | 32 (31-34) | 5424 | 34 (33-36) | 0.02 | 378 | 46 (41-51) | 1711 | 39 (37-41) | 0.01 | -- | -- | |||

| Grade 2-4 acute GVHD* (100-days) | 892 | 47 (44-50) | 750 | 41 (33-44) | 0.01 | 3776 | 45 (43-47) | 4398 | 44 (43-46) | 0.41 | 407 | 36 (31-41) | 1220 | 38 (35-41) | 0.51 | 473 | 33 (29-37) | 735 | 28 (25-31) | 0.07 |

| Grade 3-4 acute GVHD* (100-days) | 893 | 23 (20-26) | 751 | 16 (14-19) | 0.001 | 3783 | 24 (22-25) | 4400 | 19 (18-20) | <0.001 | 407 | 17 (14-21) | 1221 | 15 (13-18) | 0.45 | 473 | 18 (15-22) | 736 | 14 (12-17) | 0.10 |

| Chronic GVHD (2-years) | 891 | 39 (36-42) | 844 | 44 (41-48) | 0.03 | 3774 | 46 (45-48) | 5062 | 57 (55-58) | <0.001 | 408 | 45 (40-50) | 1471 | 56 (54-59) | <0.001 | 471 | 33 (28-37) | 778 | 37 (34-41) | 0.11 |

Prob – probability, CI – confidence intervals, GVHD – graft-versus-host disease

Cumulative incidence estimate

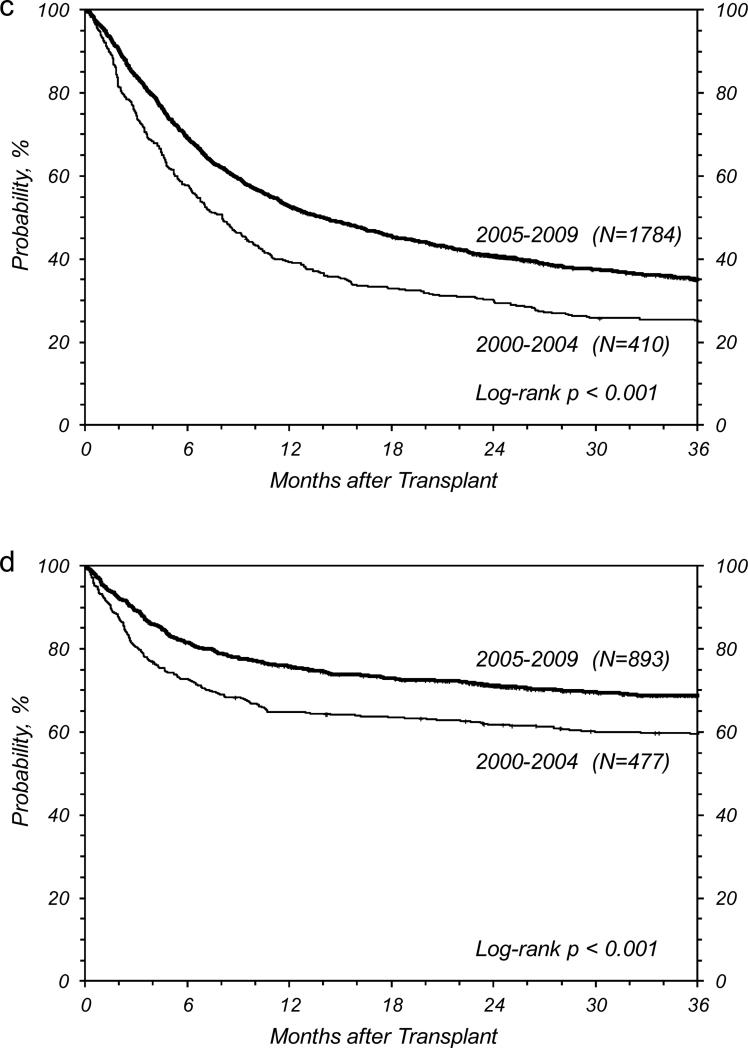

Figure 1.

Overall survival at 3 years for (a) age <18 years, malignant diseases, (b) age 18-59 years, malignant diseases, (c) age ≥ 60 years, malignant diseases, and (d) non-malignant diseases.

We considered the possibility that the observed improvements in outcomes were a result of the significantly lower proportion of patients with high-risk disease or the significantly increased use of well-matched donors after 2005. Therefore, we examined unadjusted outcomes in the following three relatively homogeneous subgroups: patients with standard-risk disease, patients with high-risk disease, and recipients of HLA 8/8 matched grafts (Table 3). NRM significantly decreased by a similar degree for patients with standard-risk and high-risk disease, which translated into significantly improved survival for both of these subgroups. This finding suggests that fewer high-risk disease transplants is insufficient to explain the gains in survival. NRM did not change in recipients of HLA 8/8 matched grafts, which suggests that increasing the proportion of transplant from matched donors did contribute to the improved outcomes observed. We further explored these issues in the multivariate analyses below.

Table 3.

Unadjusted 3-year probabilities of overall survival, non-relapse mortality and relapse for selected subgroups of unrelated donor hematopoietic cell transplant recipients

| Subgroup | Overall survival, 3-years |

Non-relapse mortality, 3-years |

Relapse, 3-years |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000-04 | 2005-09 | P-value | 2000-04 | 2005-09 | P-value | 2000-04 | 2005-09 | P- value |

|||||||

| N | Prob (95% CI) |

N | Prob (95% CI) |

N | Prob (95% CI) |

N | Prob (95% CI) |

N | Prob (95% CI) |

N | Prob (95% CI) |

||||

| Age <18 years, malignant diseases | |||||||||||||||

| Standard risk disease | 546 | 51 (47-56) | 644 | 60 (56-64) | 0.002 | 537 | 27 (23-31) | 627 | 21 (18-24) | 0.02 | 537 | 27 (24-31) | 627 | 23 (20-26) | 0.08 |

| High risk disease | 278 | 35 (30-41) | 261 | 44 (38-50) | 0.04 | 262 | 29 (24-35) | 248 | 20 (15-25) | 0.02 | 262 | 42 (37-48) | 248 | 37 (31-43) | 0.19 |

| HLA 8/8 matched donor* | 338 | 54 (49-60) | 601 | 60 (56-64) | 0.18 | 329 | 18 (14-22) | 582 | 16 (13-19) | 0.51 | 329 | 34 (29-39) | 582 | 27 (24-31) | 0.04 |

| Age 18-59 years, malignant diseases | |||||||||||||||

| MA regimen, standard risk disease | 1251 | 43 (40-46) | 2209 | 49 (47-51) | <0.001 | 1194 | 39 (36-42) | 2142 | 29 (27-31) | <0.001 | 1194 | 21 (19-23) | 2142 | 25 (24-27) | 0.002 |

| MA regimen, high risk disease | 1193 | 25 (22-27) | 1482 | 31 (29-33) | <0.001 | 1100 | 40 (38-43) | 1377 | 31 (28-33) | <0.001 | 1100 | 37 (35-40) | 1377 | 40 (38-43) | 0.14 |

| NMA/RIC regimen, standard risk disease | 381 | 45 (40-50) | 601 | 44 (40-48) | 0.69 | 371 | 31 (27-36) | 585 | 27 (24-31) | 0.21 | 371 | 30 (26-35) | 585 | 36 (32-40) | 0.08 |

| NMA/RIC regimen, high risk disease | 547 | 31 (27-35) | 657 | 41 (37-45) | <0.001 | 483 | 32 (28-36) | 611 | 23 (20-26) | <0.001 | 483 | 43 (38-47) | 611 | 43 (39-47) | 0.83 |

| AML/CML/MDS, HLA 8/8 matched donor | 1058 | 42 (39-45) | 2358 | 45 (43-47) | 0.11 | 1008 | 31 (28-34) | 2294 | 25 (24-27) | <0.001 | 1008 | 31 (28-34) | 2294 | 34 (32-36) | 0.10 |

| AML/CML/MDS, HLA 7/8 matched donor | 463 | 34 (30-39) | 776 | 35 (31-38) | 0.92 | 441 | 41 (37-46) | 735 | 36 (33-40) | 0.07 | 441 | 29 (25-33) | 735 | 32 (28-35) | 0.30 |

| Age ≥ 60 years, malignant diseases | |||||||||||||||

| NMA/RIC regimen, malignant diseases* | 331 | 27 (23-32) | 1303 | 36 (33-39) | 0.003 | 308 | 31 (26-36) | 1259 | 30 (27-32) | 0.68 | 308 | 48 (43-54) | 1259 | 41 (38-43) | 0.01 |

| Non-malignant diseases | |||||||||||||||

| Any non-malignant disease, age <18 years | 351 | 62 (57-67) | 584 | 73 (69-77) | <0.001 | -- | -- | -- | -- | ||||||

| Severe aplastic anemia | 100 | 58 (48-67) | 257 | 64 (58-70) | 0.27 | -- | -- | -- | -- | ||||||

Prob – probability, CI – confidence intervals, MA – myeloablative, NMA/RIC – non-myeloablative/reduced intensity conditioning, AML – acute myeloid leukemia, CML – chronic myeloid leukemia, MDS – myelodysplastic syndrome, HLA – human leukocyte antigen

Excluded plasma cell disorders and solid tumors from this subgroup analysis

Outcomes in Patients Age 18-59 Years with Malignant Diseases

The 3-year probability of survival significantly improved over time (35% to 42%, p<0.001) in this group (Table 2, Figure 1). The 7% improvement in survival is entirely explained by a 9% decrease in NRM (37% vs. 28%, p<0.001), which was partially offset by a 2% increase in relapse (32% vs. 34%, p=0.02). Similar to the pediatric malignant disease cohort, we observed a reduction in the 100-day cumulative incidence of grade 3-4 acute GVHD (24% vs. 19%, p<0.001), even though there was virtually no change in the incidence of grade 2-4 acute GVHD (45% vs. 44% p=0.41). As in the pediatric population, the observed increase in 2-year cumulative incidence of chronic GVHD (46% vs. 57% p<0.001) was not of a sufficient magnitude to offset the improvements in 3-year outcomes.

Again, we performed additional analyses in homogenous subgroups. Patients were divided into standard- and high-risk disease groups as before. However, unlike children where NMA/RIC regimens are not common, but which might impact both NRM and relapse risks we also accounted for conditioning regimen intensity in these strata. Furthermore, there were sufficient numbers of patients to assess whether improvements in outcomes occurred in both well-matched (8/8 HLA-matched) and single-allele-mismatched (7/8 HLA-matched) transplants. For these latter subgroups, we created the most homogenous groups possible given the numbers of patients available. Thus, we restricted these analyses to patients with AML, CML, or MDS only (Table 3). NRM improved significantly in all subgroups except recipients of NMA/RIC with standard risk disease, whose NRM rates were already relatively low.

None of the subgroups demonstrated a reduction in the cumulative incidence of relapse over time. In fact, recipients of myeloablative conditioning with standard risk disease experienced an unexpected higher relapse rate (21% to 25%, p=0.002). Hence, survival improvements were only seen in subgroups with a substantial (9-10%) decrease in NRM.

Outcomes in Patients Age≥60 Years with Malignant Diseases

The 3-year probability of survival in this cohort also significantly improved over time (Table 2, Figure 1). Unlike other age cohorts, however, the 10% absolute improvement in 3-year survival (25% to 35%, p<0.001) was primarily explained by a large reduction in the cumulative incidence of relapse (46% vs. 39%, p=0.01). Improvements in NRM were not statistically significant (35% vs. 31%, p=0.19) which may be due, in part, to a lack of improvement in the cumulative incidence of acute grade 2-4 GVHD (36% vs. 38%, p=0.51) or acute grade 3-4 GVHD, (17% vs. 15%, p=0.45). As in the other cohorts, the 2-year cumulative incidence of chronic GVHD was significantly higher in the most recent time period (45% vs. 56%, p<0.001). Although the number of patients ≥60 years increased dramatically during 2000-2009, we were only able to create one homogenous group for further analysis - NMA/RIC HCT recipients with malignant disease (excluding plasma-cell disorders and solid tumors). In this more homogenous population, outcomes were similar to those seen in the larger cohort (Table 3).

Outcomes in Patients with Non-malignant Diseases

Patients with non-malignant diseases had the best survival among all four cohorts. Similar to other cohorts, overall survival at 3-years improved significantly over time (60% to 69%, p<0.001) in this group (Table 2, Figure 1). This was also reflected by analyses restricted to homogeneous subsets of pediatric patients (data not shown). Survival rates for adult patients with severe aplastic anemia (58% to 64%, p=0.27) were not significantly different (Table 3). We did not observe a significant decrease in the cumulative incidence of acute grade 2-4 GVHD (33% vs. 28%, p=0.07) or acute grade 3-4 GVHD (18% vs. 14%, p=0.10). The cumulative incidence of chronic GVHD at 2-years was also not significantly different (33% vs. 37%, P=0.11).

Multivariate Analyses

We examined the association of time period of transplantation with outcomes in multivariate models that adjusted for all patient and transplant risk factors available (Table 4). We performed this analysis in a relatively homogenous subset of patients with AML, ALL, CML, and MDS who received their transplant from HLA 8/8 or 7/8 matched donors. Patients transplanted after 2005 continued to experience better survival and lower NRM even after adjustment for these other risk factors (see supplemental materials). Interestingly, the NRM benefit from a more recent transplant was limited to the first 12 months after HCT (HR 0.65, p<0.001). This early benefit was partially offset by an increase in NRM risk after 12 months, which suggests that some of the changes in practices delayed rather than prevented mortality. Furthermore, in this subset analysis, after accounting for these risk factors, we found no difference in risk of relapse for patients transplanted more recently (HR 0.99, p=0.816).

Table 4.

Results of multivariate analyses evaluating the association of time period with outcomes in a subset of patients with AML, ALL, CML, and MDS who received unrelated donor transplant from HLA 8/8 or 7/8 matched donor

| Outcomes | N | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall mortality*† | |||

| Early effect (≤ 12 months post-transplant) | |||

| 2000-2004 | 2574 | 1.00 | <0.001 |

| 2005-2009 | 5957 | 0.77 (0.72-0.83) | |

| Late effect (>12 months post-transplant) | |||

| 2000-2004 | 1320 | 1.00 | <0.001 |

| 2005-2009 | 3459 | 1.29 (1.14-1.46) | |

| Non-relapse mortality*‡ | |||

| Early effect (≤ 12 months post-transplant) | |||

| 2000-2004 | 2467 | 1.00 | <0.001 |

| 2005-2009 | 5751 | 0.65 (0.58-0.72) | |

| Late effect (>12 months post-transplant) | |||

| 2000-2004 | 1093 | 1.00 | <0.001 |

| 2005-2009 | 2948 | 1.56 (1.28-1.90) | |

| Relapse$ | |||

| 2000-2004 | 2467 | 1.00 | 0.816 |

| 2005-2009 | 5751 | 0.99 (0.90-1.08) |

Non-proportional hazards (hazard ratios were different for ≤ 12 months and >12 months after transplantation)

Other factors significantly associated with overall mortality included: recipient age, recipient sex, recipient ethnicity/race, Karnofsky/Lansky status at transplant, recipient CMV status, coexisting disease, diagnosis, disease risk (malignancies), time from diagnosis to transplant, HLA match and GVHD prophylaxis regimen

Other factors significantly associated with non-relapse mortality included: recipient age, recipient sex, recipient ethnicity/race, Karnofsky/Lansky status at transplant recipient CMV status, coexisting disease, diagnosis, disease risk (malignancies), time from diagnosis to transplant, HLA match and GVHD prophylaxis regimen

Other factors significantly associated with relapse included: recipient age, Karnofsky/Lansky status at transplant, coexisting disease, diagnosis, disease risk (malignancies), time form diagnosis to transplant and GVHD prophylaxis regimen

DISCUSSION

A major strength of this study is that the inclusion of nearly all unrelated donor HCT in the US provided sufficient statistical power to permit restricting the analysis to the most recent decade with 3 year follow-up. Substantial improvement in survival has occurred after unrelated donor HCT over a relatively short time span (since 2005). The absolute survival improvement of 7-10% at three years is clinically meaningful. Deaths are relatively uncommon after three years,17 and a substantial number of patients alive at 3 years are potentially cured by unrelated donor HCT. Previous reports showed that HCT survival after 2000 was better than survival in the 1990s.18,19 This present study shows that survival has not only continued to improve, it has done so even when compared to the recent past.

In this study, improvement in survival after unrelated donor HCT for children and adults <60 years was primarily a result of decreases in NRM. Multiple factors explain the significant improvements observed. These include better matching technologies, increased use of NMA/RIC regimens, and better control of severe acute GVHD. The benefit of undergoing transplantation in the more recent era appears to be mainly driven by a decrease in non-relapse related deaths in the first 12 months post-HCT, and late deaths offset some of the early gains. This may be due to more chronic GVHD associated with the greater use of peripheral blood stem cell as a graft source. While speculative, this concern was also raised by a recent randomized clinical trial that found significantly greater rates of chronic GVHD with the use of peripheral blood stem cells from unrelated donors.20

Our findings also reflect the advances in patient selection, transplantation technology and supportive care practices over the past decade that has made HCT safer. Patients transplanted more recently had better performance status, lower disease risk and received HCT earlier in their disease course. A substantially greater proportion of patients used HLA-matched unrelated donors in the later time period in all four cohorts. This is a direct reflection of advances in HLA-typing and a greater availability of well-matched donors who have been typed using high-resolution DNA sequence based methods. For example, the NMDP's Be The Match® Registry presently includes approximately 12 million donors compared to only 4 million in 2000. We also observed a notable decrease in the use of TBI as part of myeloablative conditioning regimens, which likely has decreased transplant-related toxicity. The greatest increase in unrelated donor HCT utilization occurred in the older patient cohort. This reflects the now routine use of NMA/RIC regimens, which were introduced in the 1990's, and allow HCT in older recipients and in patients with comorbidities with acceptable risks of complications and NRM. Indeed, we observed an increase in the number of patients transplanted who had coexisting diseases and comorbidities at the time of HCT in 2005-09 compared to 2000-04. Survival, NRM and relapse probabilities for the older age group in our study are comparable to what has been reported in the literature recently and should reassure clinicians about the improvement in outcomes of unrelated donor HCT in this population.21,22

Our study has the usual limitations of a registry-based retrospective cohort study. Our study population was highly heterogeneous and included a wide spectrum of diagnoses, conditioning, and GVHD prophylaxis regimens. However, these broad inclusion criteria represent the ‘real world’ practice of HCT and highlight the generalizability of our findings. To enhance the utility of this report, we constructed subgroups that represent some common scenarios (e.g., adults with standard risk malignancy) encountered by physicians in clinical practice and provide current 3-year survival, NRM and relapse rates. It is our hope that clinicians will find these statistics useful when counseling patients regarding treatment options. We did not compare the results of our cohort with patients receiving HLA-identical sibling donor HCT, although for some diseases, survival after HLA-matched unrelated and HLA-identical sibling donor transplantation has been shown to be comparable.5-10

In summary, significant improvement in survival after unrelated donor HCT has occurred over the past decade for all patient groups. Advances in patient selection and practices such as HCT earlier in the disease course, availability of better matched donors, safer conditioning regimens and improved supportive care have contributed to this improvement. Our findings should reassure clinicians and patients about the efficacy of unrelated donor HCT for patients in need of HCT who do not have a suitable HLA-identical sibling donor, and these patients should be referred to a transplant center early in their disease course. Outcomes achieved with other alternative donor sources, such as umbilical cord blood and haploidentical donors should be compared to the new baseline established in this study.

Supplementary Material

We evaluated outcomes in 15,059 unrelated donor HCT recipients between 2000-2009

Four cohorts of different ages and diseases before and after 2005 were studied

There was an absolute ~10% increase in survival among all four cohorts

Non-relapse mortality improved over time while relapse risk did not change

Acknowledgments

Funding Source:

The CIBMTR is supported by Public Health Service Grant/Cooperative Agreement U24-CA76518 from the National Cancer Institute (NCI), the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI) and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID); a Grant/Cooperative Agreement 5U01HL069294 from NHLBI and NCI; a contract HHSH234200637015C with Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA/DHHS); two Grants N00014-06-1-0704 and N00014-08-1-0058 from the Office of Naval Research; and grants from Allos, Inc.; Amgen, Inc.; Angioblast; Anonymous donation to the Medical College of Wisconsin; Ariad; Be the Match Foundation; Blue Cross and Blue Shield Association; Buchanan Family Foundation; CaridianBCT; Celgene Corporation; CellGenix, GmbH; Children's Leukemia Research Association; Fresenius-Biotech North America, Inc.; Gamida Cell Teva Joint Venture Ltd.; Genentech, Inc.; Genzyme Corporation; GlaxoSmithKline; HistoGenetics, Inc.; Kiadis Pharma; The Leukemia & Lymphoma Society; The Medical College of Wisconsin; Merck & Co, Inc.; Millennium: The Takeda Oncology Co.; Milliman USA, Inc.; Miltenyi Biotec, Inc.; National Marrow Donor Program; Optum Healthcare Solutions, Inc.; Osiris Therapeutics, Inc.; Otsuka America Pharmaceutical, Inc.; RemedyMD; Sanofi; Seattle Genetics; Sigma-Tau Pharmaceuticals; Soligenix, Inc.; StemCyte, A Global Cord Blood Therapeutics Co.; Stemsoft Software, Inc.; Swedish Orphan Biovitrum; Tarix Pharmaceuticals; Teva Neuroscience, Inc.; THERAKOS, Inc.; and Wellpoint, Inc. The views expressed in this article do not reflect the official policy or position of the National Institute of Health, the Department of the Navy, the Department of Defense, or any other agency of the U.S. Government.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest Statement: None of the authors has a relevant financial conflict of interest to disclose.

Author Contributions

Navneet Majhail, John Levine, Pintip Chitphakdithai and Brent Logan designed the study, and analyzed the results; Navneet Majhail and John Levine wrote the first draft of the manuscript; Pintip Chitphakdithai and Brent Logan performed statistical analysis; all authors contributed to the study design, interpreted data and critically reviewed the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Karanes C, Nelson GO, Chitphakdithai P, et al. Twenty years of unrelated donor hematopoietic cell transplantation for adult recipients facilitated by the National Marrow Donor Program. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2008;14(9 Suppl):8–15. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2008.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.MacMillan ML, Davies SM, Nelson GO, et al. Twenty years of unrelated donor bone marrow transplantation for pediatric acute leukemia facilitated by the National Marrow Donor Program. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2008;14(9 Suppl):16–22. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2008.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hahn T, McCarthy PL, Jr., Hassebroek A, et al. Significant improvement in survival after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation during a period of significantly increased use, older recipient age, and use of unrelated donors. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(19):2437–2449. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.46.6193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pasquini MC, Wang Z. Current use and outcome of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: CIBMTR Summary Slides. 2013 Available at: http://www.cibmtr.org.

- 5.Schetelig J, Bornhauser M, Schmid C, et al. Matched unrelated or matched sibling donors result in comparable survival after allogeneic stem-cell transplantation in elderly patients with acute myeloid leukemia: a report from the cooperative German Transplant Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(32):5183–5191. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.5184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gupta V, Tallman MS, He W, et al. Comparable survival after HLA-well-matched unrelated or matched sibling donor transplantation for acute myeloid leukemia in first remission with unfavorable cytogenetics at diagnosis. Blood. 2010;116(11):1839–1848. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-04-278317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yakoub-Agha I, Mesnil F, Kuentz M, et al. Allogeneic marrow stem-cell transplantation from human leukocyte antigen-identical siblings versus human leukocyte antigen-allelic-matched unrelated donors (10/10) in patients with standard-risk hematologic malignancy: a prospective study from the French Society of Bone Marrow Transplantation and Cell Therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(36):5695–5702. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.0952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moore J, Nivison-Smith I, Goh K, et al. Equivalent survival for sibling and unrelated donor allogeneic stem cell transplantation for acute myelogenous leukemia. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2007;13(5):601–607. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2007.01.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eapen M, Rubinstein P, Zhang MJ, et al. Comparable long-term survival after unrelated and HLA-matched sibling donor hematopoietic stem cell transplantations for acute leukemia in children younger than 18 months. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(1):145–151. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.4612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Walter RB, Pagel JM, Gooley TA, et al. Comparison of matched unrelated and matched related donor myeloablative hematopoietic cell transplantation for adults with acute myeloid leukemia in first remission. Leukemia. 2010;24(7):1276–1282. doi: 10.1038/leu.2010.102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Majhail NS, Omondi NA, Denzen E, Murphy EA, Rizzo JD. Access to hematopoietic cell transplantation in the United States. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2010;16(8):1070–1075. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2009.12.529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pidala J, Craig BM, Lee SJ, Majhail N, Quinn G, Anasetti C. Practice variation in physician referral for allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2013;48(1):63–67. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2012.95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Majhail NS, Murphy EA, Omondi NA, et al. Allogeneic transplant physician and center capacity in the United States. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2011;17(7):956–961. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2011.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaplan EL, Meier P. Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. J Am Stat Assoc. 1958;53:457–481. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Klein JP, Moeschberger ML. Survival analysis: techniques for censored and truncated data. ed 2nd Springer Verlag; New York: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cox DR. Regression models and life tables. J R Stat Soc. 1972;34:187–202. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wingard JR, Majhail NS, Brazauskas R, et al. Long-term survival and late deaths after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(16):2230–2239. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.33.7212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gooley TA, Chien JW, Pergam SA, et al. Reduced mortality after allogeneic hematopoietic-cell transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(22):2091–2101. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1004383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Horan JT, Logan BR, Agovi-Johnson MA, et al. Reducing the risk for transplantation-related mortality after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation: how much progress has been made? J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(7):805–813. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.32.5001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Anasetti C, Logan BR, Lee SJ, et al. Peripheral-blood stem cells versus bone marrow from unrelated donors. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(16):1487–1496. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1203517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McClune BL, Weisdorf DJ, Pedersen TL, et al. Effect of age on outcome of reduced-intensity hematopoietic cell transplantation for older patients with acute myeloid leukemia in first complete remission or with myelodysplastic syndrome. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(11):1878–1887. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.4821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lim Z, Brand R, Martino R, et al. Allogeneic hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation for patients 50 years or older with myelodysplastic syndromes or secondary acute myeloid leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(3):405–411. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.21.8073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bacigalupo A, Ballen K, Rizzo D, et al. Defining the intensity of conditioning regimens: working definitions. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2009;15(12):1628–1633. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2009.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weisdorf D, Spellman S, Haagenson M, et al. Classification of HLA-matching for retrospective analysis of unrelated donor transplantation: revised definitions to predict survival. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2008;14(7):748–758. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2008.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.