Abstract

Objectives

To determine whether gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms (abdominal pain, non-pain GI symptoms, nausea) and/or psychosocial distress differ between children with/without gastroparesis, and secondarily whether the severity of GI symptoms and/or psychosocial distress are related to the degree of gastroparesis.

Study design

Children 7 – 18 yr. of age (n=100; 63 female) undergoing a 4-hour gastric emptying scintigraphy (GES) study completed questionnaires evaluating GI symptoms, anxiety, and somatization for this prospective study. Spearman correlation, Mann-Whitney, t-test, and chi-square tests were utilized as appropriate for statistical analysis.

Results

Children with gastroparesis (n=25) were younger than those with normal emptying (12.6 ± 3.5 yr. vs. 14.3 ± 2.6, P=0.01). Because questionnaire responses from 7–10-year-old children were inconsistent, only patient-reported symptoms from 11–18-year-olds were used. Within this older group (n=83), children with gastroparesis (n=17) did not differ from children with normal emptying in severity of GI symptoms or psychosocial distress. In children with gastroparesis, gastric retention at 4 hr was related inversely to vomiting (r=−0.506, P=0.038), nausea (r=−0.536, P=0.019), difficulty finishing a meal (r=−0.582, P=0.014), and CSI-24 score (r=−0.544, P=0.024) and positively correlated with frequency of waking from sleep with symptoms (r=0.551, P=0.022).

Conclusions

The severity of GI symptoms and psychosocial distress do not differ between children with/without gastroparesis who are undergoing GES. In those with gastroparesis, gastric retention appears to be inversely related to dyspeptic symptoms and somatization, and positively related to waking from sleep with symptoms.

Keywords: Gastroparesis, gastric emptying, gastric scintigraphy, dyspepsia, abdominal pain

Gastroparesis is a gastrointestinal (GI) motor disorder in which the emptying of the stomach is abnormally delayed in the absence of an anatomic obstruction. The reported prevalence of gastroparesis in adults varies widely, ranging from ~ 0.04% to 4%.1–4 The pediatric prevalence of gastroparesis is unknown.

Normal GI motility depends on the integrity of the central, autonomic, and enteric nervous systems, along with the interstitial cells of Cajal and smooth muscle cells of the GI tract.5 Compromise of any of these components can potentially alter GI motility, causing such disorders as gastroparesis, intestinal pseudoobstruction, and intractable constipation.6–8 More than 70% of gastroparesis cases in children are idiopathic but likely post-infectious in nature.9,10

Gastroparesis symptoms in adults and children are nonspecific and may include abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, bloating, and early satiety.11–13 Hence, the nature of these symptoms often makes gastroparesis difficult to diagnose, as other disease processes, both GI and psychosocial, can manifest with the same symptomatology.14 The clinical diagnosis of gastroparesis in children can be challenging because of young children’s difficulty describing and reporting symptoms.

Gastric emptying scintigraphy (GES) provides an objective measure of gastric emptying.15 The use of a standardized meal in GES has allowed the determination of normal GES values in adults.16, 17 Children can easily complete the same protocol and use the same established values.18 However, GES does not necessarily reveal which symptoms, if any, are related to gastroparesis. Studies in adults have yielded conflicting results in regard to the potential relationship between gastroparesis and GI symptoms or psychosocial distress which also can affect motility.12, 13, 19, 22–24 Additionally, these studies did not assess the GI symptoms of abdominal pain or discomfort, which are thought to be common complaints in gastroparesis.3, 20, 21

Our primary aims were to determine whether GI symptoms (abdominal pain, non-pain GI symptoms, nausea) and/or psychosocial distress (anxiety, somatization) differed between children with/without gastroparesis. Our secondary aims were to determine if the severity of GI symptoms and/or psychosocial distress were related to the severity of gastroparesis.

METHODS

Children 7–18 years of age undergoing a standard solid meal GES study for outpatient evaluation of GI symptoms were prospectively included. Children with a history of GI surgery or organic GI disease (e.g., inflammatory bowel disease) were excluded. We also excluded children with any degree of learning disability, neurocognitive delay, or disability that might affect their ability to complete the questionnaires.

Children scheduled for a GES study were identified via electronic medical records. Parental consent and child assent were obtained the day of the GES study. After the radiolabeled meal was consumed and the initial scintigraphic image was captured (see below), children completed questionnaires addressing GI symptoms (e.g. abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting) (Multidimensional Measurement of Recurrent Abdominal Pain [MM-RAP]25, Supplemental Dyspepsia Questionnaire) and psychosocial comorbidities (State Trait Anxiety Inventory for Children [STAI-C]26, Children’s Somatization Inventory [CSI-24]27). The investigator read the questionnaires to children 7–10 years of age in order to control for reading comprehension difficulties. Child and parent were separated while the child completed the questionnaires and the investigator was present at all times to address any questions. Questionnaires were scored as previously described and GES results recorded.25–27

Children fasted for at least eight hours. All GES studies utilized the recommended meal of 2 pieces of white toast, 120 mL of scrambled egg substitute, a 0.5 oz packet of jelly, and 120 mL of water.17 Technetium-99-labeled sulfur colloid was mixed in the egg substitute prior to cooking. Meals were consumed within a 10-minute period after which the first scintigraphic image was obtained. Subsequent images were taken at 1-hour intervals over a 4-hour period. Children unable to consume the entire meal within a 10-minute period or who vomited within the 4-hour duration of the GES study were disqualified. Radiologists were blinded to questionnaire results. GES results were reported as the percentage of the meal remaining in the stomach at the 1-, 2-, 3-and 4-hour time points of the study (ie, gastric retention values). Gastroparesis was defined as a gastric retention value > 10% at 4 hours.17

To evaluate abdominal pain and other GI symptoms, the MM-RAP and a Supplemental Dyspepsia Questionnaire (see below) were utilized. The MM-RAP is a 32-item scale of GI symptom severity covering both upper and lower GI symptoms, disability, and pain developed and validated for use in the pediatric population with the primary focus on children with recurrent abdominal pain.25 As recommended, composite scores were calculated for the scales of the MM-RAP (abdominal pain, other GI symptoms, and disability), and a total MM-RAP score was calculated by averaging the scores from the these scales.25 Because we focused on GI symptoms, the non-GI symptom portion of the MM-RAP is not reported.

To evaluate nausea, we used the Baxter Retching Faces (BARF) scale, a validated visual rating of nausea in children.28 Both average and maximum ratings of nausea were calculated.28

None of the above scales includes a measure of vomiting alone. Thus, we created a Supplemental Dyspepsia Questionnaire which included not only vomiting but additional symptoms we believed clinically important (Table I; online). Furthermore, because the MM-RAP has dual-symptoms listed under some individual items (eg, nausea/vomiting), separate items addressing each symptom were added to the Supplemental Questionnaire.

Table I.

Results from MM-RAP Scales, Baxter Retching Faces (BARF) Scale, and Supplemental Dyspepsia Questionnaire in Children with Normal Gastric Emptying versus Gastroparesis

| Normal Emptying (n=66) |

Gastroparesis (n=17) |

P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| MM-RAP Scales | |||

| Abdominal Pain | |||

| Wong-Baker Faces | 42.8* | 38.9 | 0.53 |

| Average Pain Level | 40.5 | 47.8 | 0.26 |

| Maximum Pain Level | 41.2 | 45.0 | 0.57 |

| Composite Abdominal Pain Score | 41.1 | 45.4 | 0.52 |

| Non-Pain GI Symptoms | |||

| Abdominal Pain/Discomfort | 42.0 | 41.9 | 0.99 |

| Nausea/Vomiting | 43.3 | 36.9 | 0.31 |

| Loss of Appetite | 43.0 | 38.0 | 0.43 |

| Burping/Belching | 41.7 | 43.0 | 0.84 |

| Passing Gas | 41.1 | 45.4 | 0.49 |

| Bloating/Abdominal Distention/Fullness | 42.3 | 40.9 | 0.83 |

| Constipation/Hard Stools | 41.2 | 45.0 | 0.53 |

| Diarrhea | 43.6 | 35.6 | 0.16 |

| Wakes From Sleep | 41.3 | 44.7 | 0.59 |

| Heartburn | 40.9 | 46.3 | 0.38 |

| Sour Taste | 42.5 | 39.9 | 0.64 |

| Bad Breath | 41.7 | 43.0 | 0.83 |

| Composite Non-Pain GI Symptom Score | 41.5 | 44.1 | 0.39 |

| Disability | |||

| School Days Missed | 41.8 | 42.8 | 0.87 |

| Symptoms Interfering with Daily Activities | 40.6 | 47.5 | 0.28 |

| Symptoms Interfering with Weekend or Play Activities | 42.1 | 41.4 | 0.91 |

| Doctor Visits | 42.0 | 42.0 | 1.00 |

| Composite Disability Score | 41.6 | 43.6 | 0.51 |

| MM-RAP Total Score** | 41.1 | 45.5 | 0.74 |

| Baxter Retching Faces (BARF) Scale | |||

| Average Nausea Level | 43.5 | 36.1 | 0.25 |

| Maximum Nausea Level | 43.7 | 35.5 | 0.20 |

| Supplemental Dyspepsia Questionnaire | |||

| Pain/Discomfort Duration | 43.5 | 0.77 | |

| Pain/Discomfort Wakes from Sleep | 41.2 | 45.2 | 0.52 |

| Amount Weight Loss | 42.4 | 40.3 | 0.70 |

| Retching | 43.2 | 37.5 | 0.38 |

| Vomiting | 44.0 | 34.4 | 0.14 |

| Not Able to Finish a Normal-sized meal | 43.6 | 35.7 | 0.22 |

| Excessively Full After Meals | 40.9 | 46.2 | 0.41 |

| Loss of Appetite | 42.2 | 41.1 | 0.86 |

| Bloating | 40.7 | 47.0 | 0.32 |

Mean Rank Score (Mann-Whitney Test)

Calculation does not include Non-GI Symptom Scale Score (data not shown)

The State Trait Anxiety Inventory for Children (STAI-C) and the Children’s Somatization Inventory (CSI-24) were utilized to assess the levels of psychosocial distress.26, 27

Statistical Analyses

We calculated that to discern a 35% difference in the MM-RAP abdominal pain scale between groups (gastroparesis vs. normal emptying) with 80% power and an alpha error of < 0.5, a total sample size of 75 subjects would be required. Mann-Whitney U testing or Student’s t-test were used as appropriate to the data for comparisons between children with and without gastroparesis. Chi-square analysis was used when comparing nominal data between groups. Spearman correlation analysis was used to evaluate the potential relationships between gastric emptying and individual GI symptoms, the 3 scales of the MM-RAP, and psychosocial distress scores. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was utilized to identify groups of symptoms and/or scores that might be predictive of gastric emptying results. IBM statistical Package for the Social Sciences (Armonk, New York) version 19 software was used for all statistical analysis. Data are shown as mean ± SD or median and range as appropriate.

RESULTS

Over the 16-month study period, 100 children (63 females, 13.3 ± 3.2 years of age) were enrolled. Twenty-five (25%) children were diagnosed with gastroparesis. Children with gastroparesis were younger than those with normal gastric emptying but did not differ in sex, anthropometrics, or ethnicity (Table II).

TABLE II.

Demographics of Children with Normal Gastric Emptying Versus Gastroparesis

| Overall Group | (n=75) | (n=25) | |

| Sex | 46F (61%) | 17F (68%) | 0.55 |

| Age (years) | 14.3 ± 2.6* | 12.6 ± 3.4 | 0.011 |

| Body mass index | 21.7 ± 4.5 | 20.5 ± 5.0 | 0.28 |

| Ethnicity (n) | |||

| Caucasian | 48 | 17 | |

| Black | 6 | 0 | |

| Hispanic | 17 | 5 | |

| Asian | 1 | 2 | |

| Mixed | 3 | 1 | |

| 7–10-year-old group | (n=9) | (n=8) | |

| Sex | 3F (33%) | 4F (50%) | 0.49 |

| Age (years) | 9.4 ± 0.8 | 8.7 ± 1.2 | 0.15 |

| 11–18-year-old group | (n=66) | (n=17) | |

| Sex | 43F (65%) | 13F (76%) | 0.37 |

| Age (years) | 15.0 ± 2.0 | 14.5 ± 2.4 | 0.36 |

Mean ± SD

More children in the 7–10-year-old group (47%) had gastroparesis than in the 11–18-year-old group (20.5%, Table II). In both age groups, children with gastroparesis did not differ from those with normal gastric emptying in regard to sex, age (Table II), anthropometrics, or ethnicity (data not shown).

GI Symptom Score Exclusions

Children in the 7–10-year-old group provided inconsistent answers to similar questions spread throughout the MM-RAP and Supplemental Dyspepsia questionnaires. For example, Spearman correlation analysis between the 4 different “Nausea” items detected 1 significant correlation, and only 2 significant correlations were noted between the 4 different “Abdominal Pain” items (data not shown). In contrast, all answers to similar items provided by the 11–18-year-old group were significantly correlated (data not shown). In addition, the discordance in responses to similar questions within the younger age group was observed by the interviewer when administering the questionnaires. Because the study was predicated upon patient-reported symptoms and answers, the questionnaire responses provided by the 7–10-year-old group were not included in any of the questionnaire data analyses (GI symptoms and psychosocial distress). Therefore, only questionnaire responses from the children 11–18 years of age (n=83) were used in evaluating the possible relationship between GES results and GI symptoms/psychological distress.

GI Symptoms (11–18-year-old group) – Gastroparesis vs. Normal Gastric Emptying

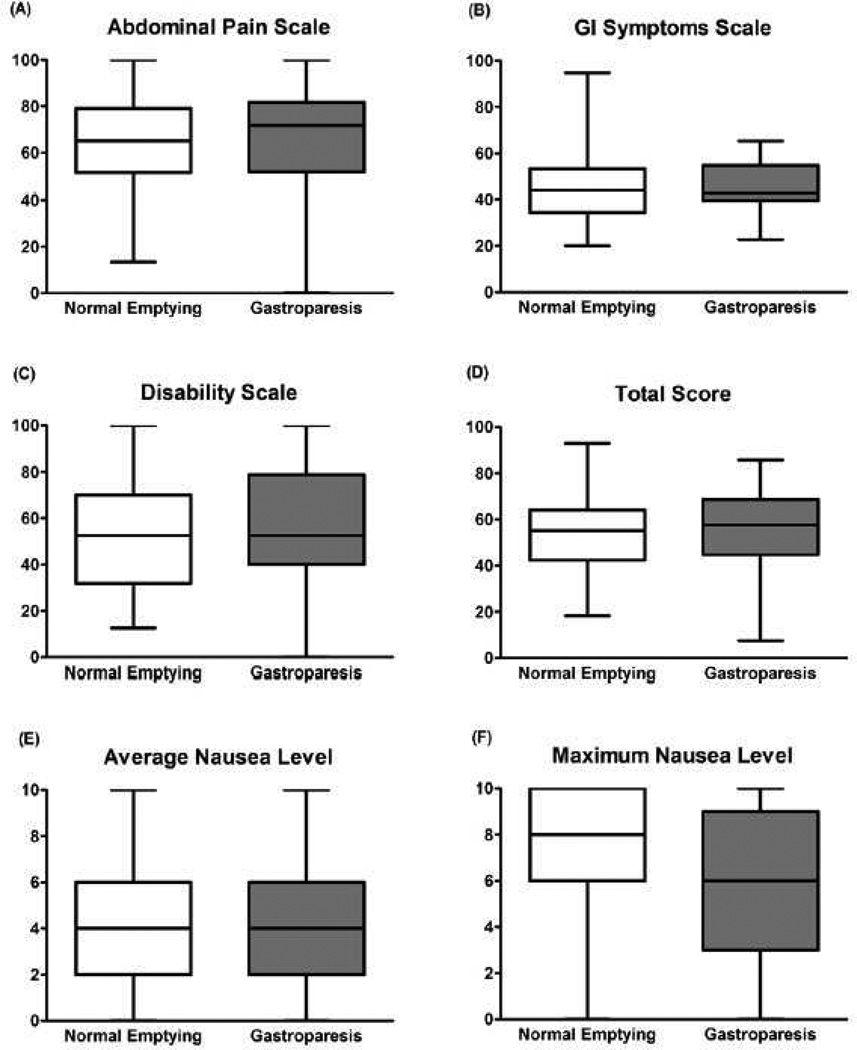

In evaluating the first primary aim, we found that scores for the GI scales of the MM-RAP questionnaire (Abdominal Pain, Non-pain GI symptoms) did not differ between children with/without gastroparesis (Figure 1). Similarly, disability (MM-RAP questionnaire) did not differ between groups (Figure 1). Univariate data analysis showed that the two groups did not differ in individual measures of abdominal pain, non-pain GI symptoms (e.g., burping/belching, heartburn) or disability (Table I).

Figure 1. GI Symptom Scores.

Based on the Multidimensional Measurement of Recurrent Abdominal Pain (MM-RAP) Composite Scores, children with normal gastric emptying (n=66) did not differ from those with gastroparesis (n=17) in regard (A) abdominal pain, (B) non-pain GI symptom, or (C) disability composite scores. (D) Total MM-RAP scores (Non-GI symptom composite scores not included in calculation) did not differ between groups. Based on the Baxter Retching Faces (BARF) scale, (E) average and (F) maximum levels of nausea did not differ between children with normal emptying (n=66) and children with gastroparesis (n=17). Figures show median, 25th and 75th percentiles, and ranges

Based upon the BARF scale, both average and maximum levels of nausea also were similar in children with gastroparesis compared with those with normal gastric emptying (Figure 1).

Similarly, individual responses to the Supplemental Dyspepsia Questionnaire did not differ between children with and without gastroparesis (Table I). There was a trend toward less vomiting (P=0.14) in the gastroparesis group (Table I). However, significance and trends for all variables from both the MM-RAP and Supplemental Dyspepsia Questionnaires were lost in the multivariate analysis.

Psychosocial Distress (11–18-year-old group)

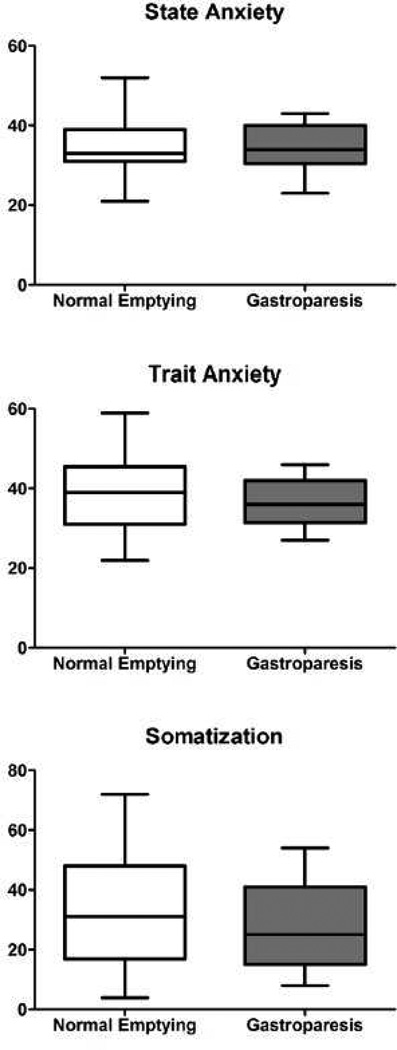

State anxiety, trait anxiety, and somatization (CSI-24) scores did not differ between children with and without gastroparesis (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Psychological Distress Scores.

Children with normal gastric emptying did not differ from those with gastroparesis in regard to State Anxiety, Trait Anxiety, and Children’s Somatization Inventory (CSI-24) scores. Figures show median, 25th and 75th percentiles, and ranges

Relationships between Gastric Retention Values and GI Symptom Severity (11–18-year-old group)

For the group as a whole (children with/without gastroparesis), Spearman correlation analysis did not detect any significant correlations between gastric retention values and each of the individual GI symptoms based on MM-RAP responses, or with any of the 3 scales of the MM-RAP (data not shown). Similarly, no correlations were detected between gastric retention values and individual GI symptoms based on the Supplemental Dyspepsia Questionnaire (data not shown). Neither of the two nausea measures, based upon the BARF scale, correlated with gastric retention values (data not shown). In analyzing only children diagnosed with gastroparesis (n=17) however, gastric retention values were inversely correlated to vomiting (Supplemental Dyspepsia Questionnaire), average nausea level (BARF Scale), difficulty finishing a normal meal (Supplemental Dyspepsia Questionnaire), and bad breath (MM-RAP) (Figure 3). In contrast, a positive correlation was noted between gastric retention values and waking from sleep due to symptoms (Supplemental Dyspepsia Questionnaire) (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Spearman Correlation Analysis of Gastric Retention Values versus Gastrointestinal Symptoms and Somatization in Children with Gastroparesis.

In children with gastroparesis (n=17), gastric retention values were inversely related to (A) vomiting (Supplemental Dyspepsia Questionnaire), (B) average nausea level (BARF scale), (C) difficulty finishing a normal meal (Supplemental Dyspepsia Questionnaire), and (D) bad breath (MM-RAP). Gastric retention values were positively related to (E) the frequency of waking from sleep due to symptoms (Supplemental Dyspepsia Questionnaire). Gastric retention was inversely related to (F) somatization (Children’s Somatization Inventory scores, CSI-24).

Relationships between Gastric Retention Values and Psychosocial Distress Scores (11–18-year-old group)

Spearman correlation analysis did not detect any significant relationships between gastric retention values and each of the psychosocial distress scores for the group as a whole (data not shown). In analyzing only children diagnosed with gastroparesis, gastric retention values were inversely related to the somatization (CSI-24) score (Figure 3), but not to the other psychosocial distress scores.

DISCUSSION

GES has long been the gold standard tool for making the diagnosis of gastroparesis. Clinically, several specific symptoms historically have been associated with gastroparesis (e.g., abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, bloating). We investigated the potential relationship between GES results, GI symptoms, and measures of psychosocial distress. In regard to our primary aims, we were not able to detect a difference in GI symptom scores (abdominal pain, non-pain GI symptoms, nausea) between children with/without gastroparesis. Similarly, psychosocial distress levels were similar between the two groups (Figure 2).

In adults, only severe vomiting symptoms were related to delayed gastric emptying.12 Using the Gastroparesis Cardinal Symptom Index (GCSI), Cassilly et al found that adult subjects with gastroparesis at 4 hours did not differ in symptoms from those without gastroparesis.11 Similar findings at 4 hours were reported by Pasricha et al using the GCSI.19 Although the GCSI is a validated clinical measure of gastroparesis in adults, the GCSI does not contain items addressing abdominal pain or discomfort.3, 20, 21

Psychosocial factors have been shown to affect GI motility in human and animal studies.14, 22–24 Although Pasricha et al reported that subjects with gastroparesis had significantly higher levels of anxiety (based on the State Trait Anxiety Index) than those without gastroparesis.19 This is in contrast to a similar study by Hasler et al.21

As secondary aims, we assessed if the severity of GI symptoms and/or psychosocial distress were related to the degree of gastroparesis (gastric retention value). Spearman correlation analysis did not reveal any significant relationships between specific GI symptom scores and gastric retention values for the 11–18-year-old group as a whole. However, in those with gastroparesis, gastric retention values were found to be negatively correlated with vomiting, average BARF scores, bad breath, and difficulties finishing a normal meal. These results came as somewhat of a surprise, as it could be argued that vomiting, nausea (BARF score), bad breath, and difficulties finishing normal meals could be a result of poor gastric emptying. We hypothesize this inverse relationship may be related in part to the child’s relative gastric size, as well as to dysfunction in proximal (fundic) gastric accommodation. This postulate is based upon studies demonstrating that adult patients with functional dyspepsia have an impaired proximal accommodation reflex in response to antral distention with a more distal distribution of intragastric food contents compared with healthy controls.29, 30 Bredenoord et al reported that 43% of 214 adults with endoscopy-negative dyspepsia had impaired gastric accommodation versus only 14% with delayed gastric emptying, thus suggesting impaired proximal stomach accommodation may better account for the dyspeptic symptoms.31 Whether gastric size and/or poor proximal gastric accommodation have an effect on symptoms more than that of gastroparesis requires further study.

In the group as a whole, Spearman correlation analysis did not detect any relationship between psychosocial distress measures and gastric retention values. However, in children with gastroparesis, somatization scores (CSI-24) were inversely related to gastric retention values. This might suggest that somatic complaints may become less contributory as the severity of true gastroparesis increases. Whether these findings imply that symptoms in the majority of the children with normal gastric emptying may have been more functional in nature requires further study. Geeraerts et al have demonstrated that with increasing levels of anxiety (measured by STAI) there is a decrease in gastric accommodation (measured by barostat testing).32, 33 However, to our knowledge, the potential relationship between somatization and gastric accommodation has not been studied in children.

Our findings suggest that symptoms often attributed to gastroparesis are not highly predictive of the actual presence of gastroparesis. As such, a diagnosis of gastroparesis based on symptoms may be difficult clinically and formal testing (i.e., gastric emptying scan) may be helpful. For those children in whom gastroparesis is identified (ie, by gastric emptying scan), symptoms do appear to correlate with the degree of gastric retention. Hence, in a patient with gastroparesis, the degree of symptomatology (eg, vomiting, nausea, etc.) may help guide management.

There are some limitations to our study. Although it appeared that the frequency of gastroparesis in children 7–10 years of age was greater than that in the older children, the relatively small number of subjects in the younger group limits interpretation. We discovered that children in the younger age group did not provide consistent responses to similar questions. Thus, we were not able to reliably assess the potential relationships between GI symptoms and GES results in the youngest children. Future studies will require questionnaires validated for use in younger children or validated parent-report questionnaires. However, the consistency between child vs parent report also must be evaluated.34 Another limitation is that the 10% gastric retention value for the diagnosis of gastroparesis has been validated for adults but validation studies have not been done in children. Analyzing our data using different gastric residual value cut-off points ranging from 10–20% for the diagnosis of gastroparesis did not significantly alter our findings (data not shown). The study was not powered to definitively address our secondary aims because of potential issues with multiple testing. Thus, the findings will need to be confirmed.

There are a number of strengths to the study. These include the prospective design, use of validated pediatric questionnaires (MM-RAP, BARF scale), the relatively large sample size, the blinded design of the study, the inclusion of psychosocial measures, and the use of a single investigator to present the questionnaires. We also limited the number of GI symptoms (abdominal pain, non-pain GI symptoms, nausea) and psychosocial distress measures (anxiety, somatization) that we compared between groups (gastroparesis vs. normal emptying) to reduce the chance of a type 1 error. The observation that correlations between gastric retention values and symptom severity and somatization were only found in children with gastroparesis and not in the total population supports that they are not due to chance. However, independent confirmation from other studies will be required.

In summary, in children with dyspepsia undergoing gastric emptying scintigraphy, those with gastroparesis do not have more severe gastrointestinal symptoms or psychosocial distress as compared with children with normal gastric emptying. However, in those with identified gastroparesis, the severity of gastroparesis may be related to several dyspeptic symptoms and somatization.

Acknowledgments

Supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH; R01 NR05337), the Daffy’s Foundation, the US Department of Agriculture’s Agricultural Research Service (6250-51000-043 to RJS), and NIH/National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Disease (P30 DK56338 to the Texas Medical Center Digestive Disease Center). B.C. was funded by the NASPGHAN Foundation/Nestle Nutrition Young Investigator Development Award. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or the US Department of Agriculture; mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations does not imply endorsement by the US Government.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abell TL, Bernstein RK, Cutts T, Farrugia G, Forster J, Hasler WL, et al. Treatment of gastroparesis: a multidisciplinary clinical review. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2006 Apr;18:263–283. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2006.00760.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jung HK, Choung RS, Locke GR, 3rd, Schleck CD, Zinsmeister AR, Szarka LA, et al. The incidence, prevalence, and outcomes of patients with gastroparesis in Olmsted County, Minnesota, from 1996 to 2006. Gastroenterology. 2009 Apr;136:1225–1233. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.12.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Parkman HP, Yates K, Hasler WL, Nguyen L, Pasricha PJ, Snape WJ, et al. Clinical features of idiopathic gastroparesis vary with sex, body mass, symptom onset, delay in gastric emptying, and gastroparesis severity. Gastroenterology. 2011 Jan;140:101–115. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Soykan I, Sivri B, Sarosiek I, Kiernan B, McCallum RW. Demography, clinical characteristics, psychological and abuse profiles, treatment, and long-term follow-up of patients with gastroparesis. Dig Dis Sci. 1998 Nov;43:2398–2404. doi: 10.1023/a:1026665728213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huizinga JD. Neural injury, repair, and adaptation in the GI tract. IV. Pathophysiology of GI motility related to interstitial cells of Cajal. Am J Physiol. 1998;275:G381–G386. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1998.275.3.G381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vinik AI, Maser RE, Mitchell BD, Freeman R. Diabetic autonomic neuropathy. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:1553–1579. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.5.1553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ziegler D, Schadewaldt P, Pour Mirza A, Piolot R, Schommartz B, Reinhardt M, et al. [13C] octanoic acid breath test for non-invasive assessment of gastric emptying in diabetic patients: validation and relationship to gastric symptoms and cardiovascular autonomic function. Diabetologia. 1996;39:823–830. doi: 10.1007/s001250050516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ordog T, Takayama I, Cheung WK, Ward SM, Sanders KM. Remodeling of networks of interstitial cells of Cajal in a murine model of diabetic gastroparesis. Diabetes. 2000;49:1731–1739. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.49.10.1731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sigurdsson L, Flores A, Putnam PE, Hyman PE, Di Lorenzo C. Postviral gastroparesis: Presentation, treatment and outcome. J Pediatrics. 1997;131:751–754. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(97)70106-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chumpitazi BP, Nurko S. Pediatric gastrointestinal motility disorders: challenges and a clinical update. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y) 2008;4:140–148. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cassilly DW, Wang YR, Friedenberg FK, Nelson DB, Maurer AH, Parkman HP. Symptoms of gastroparesis: use of the gastroparesis cardinal symptom index in symptomatic patients referred for gastric emptying scintigraphy. Digestion. 2008;78:144–151. doi: 10.1159/000175836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stanghellini V, Tosetti C, Paternico A, Barbara G, Morselli-Labate AM, Monetti N, et al. Risk indicators of delayed gastric emptying of solids in patients with functional dyspepsia. Gastroenterology. 1996;110:1036–1042. doi: 10.1053/gast.1996.v110.pm8612991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sarnelli G, Caenepeel P, Geypens B, Janssens J, Tack J. Symptoms associated with impaired gastric emptying of solids and liquids in functional dyspepsia. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:783–788. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07389.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Geeraerts B, Vandenberghe J, Van Oudenhove L, Gregory LJ, Aziz Q, Dupont P, et al. Influence of experimentally induced anxiety on gastric sensorimotor function in humans. Gastroenterology. 2005 Nov;129:1437–1444. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Camilleri M, Hasler W, Parkman HP, Quigley EM, Soffer E. Measurement of gastroduodenal motility in the GI laboratory. Gastroenterology. 1998;115:747–762. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70155-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abell TL, Camilleri M, Donohoe K, Hasler WL, Lin HC, Maurer AH, et al. Consensus recommendations for gastric emptying scintigraphy: a joint report of the American Neurogastroenterology and Motility Society and the Society of Nuclear Medicine. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008 Mar;103:753–763. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01636.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tougas G, Eaker EY, Abell TL, Abrahamsson H, Biovin M, Chen J, et al. Assessment of gastric emptying using a low fat meal: Establishment of international control values. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:1456–1462. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.02076.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chogle A, Saps M. Gastroparesis in children, cost and benefit of conducting 4 hours scintigraphic gastric emptying studies. JPGN. 2013 Apr;56:439–442. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e31827a789c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pasricha PJ, Colvin R, Yates K, Hasler WL, Abell TL, Unalp-Arida A, et al. Characteristics of patients with chronic unexplained nausea and vomiting and normal gastric emptying. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011 Jul;9:567–576. e1–e4. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2011.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cherian D, Sachdeva P, Fisher RS, Parkman HP. Abdominal pain is a frequent symptom of gastroparesis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010 Aug;8:676–681. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2010.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hasler WL, Wilson LA, Parkman HP, Koch KL, Abell TL, Nguyen L, et al. Factors related to abdominal pain in gastroparesis: contrast to patients with predominant nausea and vomiting. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2013 May;25:427–438. doi: 10.1111/nmo.12091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Taché Y, Perdue MH. Role of peripheral CRF signalling pathways in stress-related alterations of gut motility and mucosal function. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2004 Apr;16(Suppl 1):137–142. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-3150.2004.00490.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Van Oudenhove L, Vandenberghe J, Geeraerts B, Vos R, Persoons P, Fischler B, et al. Determinants of symptoms in functional dyspepsia: gastric sensorimotor function, psychosocial factors or somatisation? Gut. 2008 Dec;57:1666–1673. doi: 10.1136/gut.2008.158162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hasler WL, Parkman HP, Wilson LA, Pasricha PJ, Koch KL, Abell TL, et al. Psychological dysfunction is associated with symptom severity but not disease etiology or degree of gastric retention in patients with gastroparesis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010 Nov;105:2357–2367. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Malaty HM, Abudayyeh S, O'Malley KJ, Wilsey MJ, Fraley K, Gilger MA, et al. Development of a multidimensional measure for recurrent abdominal pain in children: population-based studies in three settings. Pediatrics. 2005 Feb;115:e210–e215. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Spielberger CD, Gorsuch RL, Lushene RE. Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (Self-Evaluation Questionnaire) Palo Alto: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1970. revised 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Walker LS, Beck JE, Garber J, Lambert W. Children's Somatization Inventory: psychometric properties of the revised form (CSI-24) J Pediatr Psychol. 2009 May;34:430–440. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsn093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baxter AL, Watcha MF, Baxter WV, Leong T, Wyatt MM. Development and validation of a pictorial nausea rating scale for children. Pediatrics. 2011 Jun;127:e1542–e1549. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-1410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Caldarella MP, Azpiroz F, Malagelada JR. Antro-fundic dysfunctions in functional dyspepsia. Gastroenterology. 2003 May;124:1220–1229. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(03)00287-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Troncon LE, Bennett RJ, Ahluwalia NK, Thompson DG. Abnormal intragastric distribution of food during gastric emptying in functional dyspepsia patients. Gut. 1994 Mar;35:327–332. doi: 10.1136/gut.35.3.327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bredenoord AJ, Chial HJ, Camilleri M, Mullan BP, Murray JA. Gastric accommodation and emptying in evaluation of patients with upper gastrointestinal symptoms. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2003 Jul;1:264–272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Geeraerts B, Vandenberghe J, Van Oudenhove L, Gregory LJ, Aziz Q, Dupont P, et al. Influence of experimentally induced anxiety on gastric sensorimotor function in humans. Gastroenterology. 2005 Nov;129:1437–1444. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Van Oudenhove L, Vandenberghe J, Geeraerts B, Vos R, Persoons P, Demyttenaere K, et al. Relationship between anxiety and gastric sensorimotor function in functional dyspepsia. Psychosom Med. 2007 Jun;69:455–463. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3180600a4a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Czyzewski DI, Lane MM, Weidler EM, Williams AE, Swank PR, Shulman RJ. The interpretation of Rome III criteria and method of assessment affect the irritable bowel syndrome classification of children. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011 Feb;33:403–411. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2010.04535.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]