Abstract

Alcohol consumption is a predominant etiological factor in the pathogenesis of chronic liver diseases, resulting in fatty liver, alcoholic hepatitis, fibrosis/cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Although the pathogenesis of alcoholic liver disease (ALD) involves complex and still unclear biological processes, the oxidative metabolites of ethanol such as acetaldehyde and reactive oxygen species (ROS) play a preeminent role in the clinical and pathological spectrum of ALD. Ethanol oxidative metabolism influences intracellular signaling pathways and deranges the transcriptional control of several genes, leading to fat accumulation, fibrogenesis and activation of innate and adaptive immunity. Acetaldehyde is known to be toxic to the liver and alters lipid homeostasis, decreasing peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors and increasing sterol regulatory element binding protein activity via an AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK)-dependent mechanism. AMPK activation by ROS modulates autophagy, which has an important role in removing lipid droplets. Acetaldehyde and aldehydes generated from lipid peroxidation induce collagen synthesis by their ability to form protein adducts that activate transforming-growth-factor-β-dependent and independent profibrogenic pathways in activated hepatic stellate cells (HSCs). Furthermore, activation of innate and adaptive immunity in response to ethanol metabolism plays a key role in the development and progression of ALD. Acetaldehyde alters the intestinal barrier and promote lipopolysaccharide (LPS) translocation by disrupting tight and adherent junctions in human colonic mucosa. Acetaldehyde and LPS induce Kupffer cells to release ROS and proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines that contribute to neutrophils infiltration. In addition, alcohol consumption inhibits natural killer cells that are cytotoxic to HSCs and thus have an important antifibrotic function in the liver. Ethanol metabolism may also interfere with cell-mediated adaptive immunity by impairing proteasome function in macrophages and dendritic cells, and consequently alters allogenic antigen presentation. Finally, acetaldehyde and ROS have a role in alcohol-related carcinogenesis because they can form DNA adducts that are prone to mutagenesis, and they interfere with methylation, synthesis and repair of DNA, thereby increasing HCC susceptibility.

Keywords: Alcohol metabolism, Acetaldehyde, Reactive oxygen species, Alcoholic liver disease, Protein adducts, Hepatic stellate cells, Liver fibrosis, CYP2E1

Core tip: The goal of this article is to review the mechanisms of alcohol-mediated toxicity in parenchymal and non-parenchymal cells of the liver. Specifically, we highlight the effect of oxidative ethanol metabolites such as acetaldehyde and reactive oxygen species in the development of fat accumulation, fibrosis and deranged immune response.

INTRODUCTION

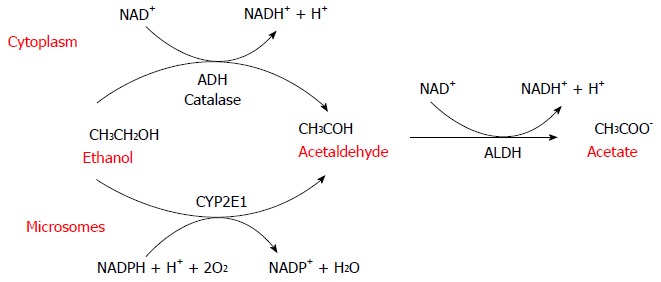

Alcoholic liver disease (ALD) is one of the major cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide and its clinical spectrum includes steatosis, fibrosis, alcoholic hepatitis (AH), cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)[1]. Multiple factors (sex, obesity and genetic) are involved in the progression of ALD but how these aspects influence the clinical outcome remain unclear. More than 90% of heavy drinkers develop fatty accumulation but only 30% of alcoholics develop severe forms of ALD. Ethanol and the products of its metabolism have toxic effects on the liver and in recent decades, significant progress has been made in understanding the molecular mechanisms by which ethanol oxidative metabolism contributes to the pathogenesis of ALD[2]. Ethanol oxidation to acetate is a two-step process carried out by the enzymes alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH) and aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH). These enzymes use NAD+ as a cofactor (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Alcohol metabolism. Alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH) is the main cytosolic enzyme that converts alcohol to acetaldehyde. The inducible microsomal enzyme also forms acetaldehyde. The toxic metabolite acetaldehyde is then further oxidized to acetate by the mitochondrial aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH).

ADH first oxidizes ethanol to acetaldehyde, which is then further oxidized to acetate by ALDH. In humans, there are at least eight isoenzymes of ADH and four of ALDH. ADH is a family of cytosolic enzymes mainly present in the liver but also in the gastrointestinal tract, kidney, nasal mucosa, testis and uterus. They are classified into five classes (ADH1-5) that differ in their structural and kinetic characteristics. ADH1 plays the major role in the metabolism of ethanol in the liver[3-7]. As a result of its electrophilic nature, acetaldehyde[8] can bind and form covalent chemical adducts with proteins, lipids and DNA[9-13]. These adducts are broadly pathogenic because they alter cell homeostasis, changing protein structure[11,12,14,15] and promoting DNA damage and mutation.

ADH and ALDH reactions lead to an accumulation of NADH and the consequent reduction of NAD+/NADH ratio that has a significant effect on important biochemical pathways such as glycolysis, citric acid cycle, fatty acid oxidation, and glucogenesis. NADH is mainly reoxidized to NAD+ by the mitochondrial electron transfer chain[16,17]. During the electrons transfer to oxygen, different reactive oxygen species (ROS) such as superoxide anion (O2-∙), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), and the hydroxyl radical (OH.) are formed[16]. These species are unstable and rapidly react with additional electrons and protons. Although most of these ROS are converted to water before they can damage cells[18], a small proportion can generate toxic effects as lipid peroxidation, enzymes inactivation, DNA mutations, and destruction of cell membranes[19-21].

Another metabolic system involved in ethanol metabolism is the microsomal ethanol oxidizing system (MEOS) constituted by the cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzymes. These proteins are a superfamily of heme enzymes involved in oxidation of numerous endogenous substrate such as steroids, fatty acid and xenobiotics[22]. They catalyze many different reactions, such as mono-oxygenation, peroxidation, dealkylation, epoxidation, and dehalogenation in order to convert different chemical molecules in more polar metabolites to be excreted. An ethanol-inducible form of P450[23] catalyzes ethanol oxidation at rates much higher than other CYP enzymes. In physiological conditions only a small amount of ethanol, about 10%, is oxidized to acetaldehyde by CYP2E1[24] but during chronic alcohol abuse there is induction of the microsomal system[25,26], and an increase in CYP2E1 protein expression. The increase in CYP2E1 during chronic ethanol intake is correlated with a decrease in proteasomal degradation, which increases CYP2E1 protein stability[27,28]. Multiple factors such as insulin, acetone, leptin, adiponectin and cytokines regulate CYP2E1 mRNA and protein expression[29] and CYP2E1 expression levels depend on nutritional and metabolic conditions. For example, genetic obese mice or high-fat-diet-fed rats have high levels of CYP2E1[30,31]. Furthermore, increased CYP2E1[32] is found in diabetes, probably due to insulin post-transcriptional modulation[33,34]. CYP2E1 catalyzes the oxidation of ethanol to acetaldehyde and it can catalyze the oxidation of the latter to acetate[35] but this reaction is disadvantageous in the presence of ethanol[36]. The catalytic reaction of CYP2E1 generates a significant amounts of ROS, such as O2-∙, H2O2, OH. and the hydroxyethyl radical (HER)[29,37].

H2O2 can react with metal ions to produce highly reactive OH. radicals[37,38] and determine a broad range of adverse biological responses[37,39]. Lipid peroxidation is probably the most important reaction involved in alcohol-induced liver damage[40,41] by the formation of toxic aldehydes, including malondialdehyde (MDA) and 4-hydroxynonenal (4-HNE), which, similar to acetaldehyde are able to react with DNA to form exocyclic DNA adducts. DNA adducts such as N2-ethyldeoxyguanosine (N2-Et-dG)[40] and 1,N(2)-propano-2’-deoxyguanosine (PdG) are detectable in livers of alcohol-exposed mice, and in alcohol-associated cancers[42] in humans. They generate DNA-protein and DNA interstrand crosslinks[12] and produce replication errors and mutations in oncogenes or oncosuppressor genes[43] with genotoxic, mutagenic and carcinogen effects[43]. Aldehydes generated by ethanol metabolism can also crossreact to form hybrid adducts. For example, MDA/acetaldehyde hybrid adducts (MAAs) potentiate carcinogenic effect of single adducts[10,44,45], thereby perpetuating their genotoxic effects. Autoantibodies against MMA were significantly elevated in sera of chronic alcohol-exposed animals[46] and in patients with ALD, and the titers are correlated with the severity of liver damage[11,47,48] and progression of liver fibrosis. Interestingly, adducts accumulate in perivenous regions both in alcohol-fed rats[49,50] and in the liver of alcoholics[51,52], overlapping with the distribution of fatty accumulation.

Peroxisomal catalase is an additional metabolic pathway involved in ethanol oxidation. Catalase is a heme-containing enzyme that normally catalyzes the removal of H2O2 but it can catalyze the oxidation of alcohol to acetaldehyde. This pathway is not significant in the liver, but seems to be important in the brain. In fact acetaldehyde produced from catalase-dependent oxidation of ethanol seems to play a role in tolerance and alcohol addiction interfering with catecholamine neurotransmission[53-55].

MECHANISMS OF ALCOHOLIC FATTY LIVER

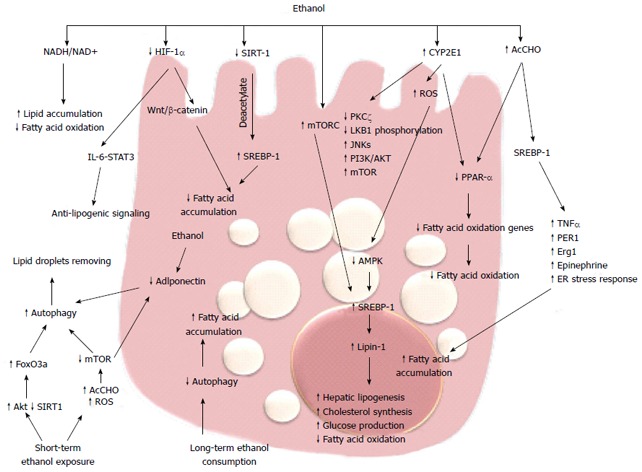

The earliest response of the liver to alcohol abuse is characterized by lipid accumulation in hepatocytes, which is a reversible condition but can progress to inflammation and fibrosis. The mechanism of triglyceride and fatty acid accumulation in the liver during alcohol consumption involves regulatory pathways that control lipid synthesis, oxidation and very-low density lipoprotein exportation. Short-term studies on isolated hepatocytes or perfused liver have shown that ethanol reduces the rate of β-oxidation and stimulates fatty acid uptake[56]. The increased production of reducing equivalents (NADH) from ethanol oxidation by ADH is believed to cause a shift in the cytosolic NADH/NAD+ ratio, which in turn increased NADH/NAD+ ratio in the mitochondria. Many of the enzymes of fatty acid oxidation are pyridine nucleotide dependent, thus, their activities are inhibited by NADH, resulting in reduced ability to oxidize fatty acids[57,58]. Although generation of reducing equivalents by ADH is sufficient to cause lipid accumulation[59], the finding that fat infiltration in the liver persists despite normalization of NADH/NAD+ ratio, and that antioxidants prevent it in rats chronically fed alcohol, suggest that additional mechanisms are involved[60] (Figure 2). The role of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs) in fatty liver disease has been investigated in the past decade. These receptors are members of steroid/retinoid nuclear receptor superfamily of transcription factors[61,62]. PPARα regulates transcription of genes involved in the esterification and export of fatty acids and oxidizing them in the mitochondria, peroxisomes, and microsomes.

Figure 2.

Molecular mechanisms of alcoholic fatty liver. Alcohol consumption via multiple pathways increases the expression of SREB-1 and downregulates PPAR-α, promoting fatty acid synthesis and impairing β-oxidation, thus resulting in fatty acid accumulation. Long-term ethanol consumption promotes fatty acid accumulation through decreased autophagy, while short-term ethanol exposure promotes autophagy and degradation of lipid droplets. HIF: Hypoxia inducible factor; ROS: Reactive oxygen species.

PPARα-null mice fed with Lieber-DeCarli diet exhibited hepatomegaly, macrovesicular steatosis, hepatocyte apoptosis, and hepatic fibrosis; all aspects resembling the pathological features of ALD[62], and suggesting that inhibition of PPARα transcriptional activity is implicated in fat accumulation. Ethanol metabolism, by way of acetaldehyde, interferes with the transcriptional activity of PPARα in hepatoma cells[62]. This effect is accompanied by a reduction in the ability of this receptor to bind its DNA consensus sequence, reflecting a possible covalent modification by acetaldehyde or changes in its phosphorylation state. Accordingly, chronic ethanol feeding in mice inhibited PPARα DNA binding activity and decreased PPARα target genes[63,64]. In mouse models of ALD, treatment with PPARα ligands such as WY14, 643 and clofibrate, restores receptor activity and significantly ameliorates fat accumulation and necroinflammation[63,64]. In addition, ethanol can also inhibit PPARα via upregulation of CYP2E1-derived oxidative stress[65].

Sterol regulatory element-binding proteins (SREBPs) are a family of transcription factors strictly correlated with PPARs and they control a set of enzymes involved in the synthesis of fatty acids and triglycerides. acetaldehyde produced from ethanol metabolism enhances the levels of SREBP-1 in hepatoma cells[66] and SREBP-1 protein levels are increased in animal models of alcohol-induce hepatic fat accumulation[66,67]. The role of SREBP-1 in alcoholic steatosis has been confirmed by several studies that couple the levels of this transcription factor with the ability to promote alcoholic fat accumulation by tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α[68], circadian gene Per-1[69], early growth response (Egr)-1[70], epinephrine[71] and ER stress response[72]. In response to acute and chronic ethanol exposure, mitogen-activated protein kinase family members, including c-Jun N-terminal protein kinase (JNK), are activated and JNK inhibitors blunt steatosis, reducing oxidative stress and blocking SREBP-1 expression in hepatoma cells[73]. Recent studies have demonstrated that phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/AKT pathway activation is involved in acute ethanol-induced fatty liver in mice, and specifically inhibits the phosphorylation and degradation of SREBP-1[74]. SREBP-1 is also modulated by AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK).

AMPK is a key player in the regulation of cellular energy homoeostasis by limiting anabolic pathways (to prevent further ATP consumption) and by facilitating catabolic pathways (to increase ATP generation). AMPK is a metabolic sensor by phosphorylation of enzymes involved in lipid metabolism. Chronic ethanol exposure inhibits AMPK activity in cultured rat hepatocytes through the inhibition of protein kinase (PK)Cζ and liver kinase (LK)B1 phosphorylation[75], and impaired AMPK activity was shown in hepatocytes isolated from rats fed with ethanol[76]. This inhibition plays a key role in the development of steatosis by the activation of hepatic lipogenesis, cholesterol synthesis, and glucose production in parallel with the decrease in fatty acid oxidation[74]. In rat hepatoma cells, overexpression of a constitutively active form of AMPK blocked the effect of ethanol, but in contrast, a dominant negative form augmented the effect through regulating SREBP-1[77]. Recent data have demonstrated that Lipin-1, a Mg2+ phosphatidate phosphatase involved in the biosynthesis of triacylglycerol and the transcriptional regulation of lipid homeostasis, is upregulated by ethanol through inhibition of AMPK and activation of SREBP-1[78]. Increased intracellular concentrations of ROS may represent a general mechanism for the enhancement of AMPK-mediated cellular adaptation, including the maintenance of redox homeostasis. AMPK activation by ROS can promote cell survival by inducing autophagy, mitochondrial biogenesis, and expression of genes involved in antioxidant defense.

Autophagy is a genetically programmed, evolutionarily conserved process of cellular catabolism that serves to maintain a balance among protein synthesis, degradation, and recycling. Autophagy implies degradation of damaged organelles and cellular protein in order to promote cell survival[79]. The mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) is a key regulator of autophagy. During deprivation of nutrients or other cause of cellular stress, there is inhibition of the mTOR/rapamycin pathway and consequent activation of autophagy in hepatocytes[80,81]. There are contrasting data regarding the effect of ethanol metabolism on autophagy. Long-term alcohol consumption inhibits autophagy[82] but one recent study has shown that ethanol metabolism upregulates autophagy in cultured hepatoma cells[83]. Short-term ethanol exposure activates autophagy by generating acetaldehyde and ROS and inhibiting mTOR. These data indicate that acute ethanol activation of autophagy could have a compensatory role that prevents development of steatosis during the early stages of alcoholic liver injury[84]. Beyond mTOR, there are several other pathways involved in the induction of autophagy. Recently, Ni et al[84] demonstrated that in vivo and in vitro acute ethanol treatment activates nuclear translocation of forkhead box (Fox)O3a and expression of FoxO3a target genes. The authors suggest that the ethanol activation of FoxO3a could be mediated by Akt activation. In primary hepatocytes, expression of a dominant negative form of FoxO3a inhibits ethanol-induced, autophagy-related genes and improves ethanol-induced cell death, suggesting that FoxO3a is a key factor in regulating ethanol-induced autophagy and cell survival[85,86]. In addition, Sirtuin (SIRT)-1, the NAD+-dependent protein deacetylase is indicated as an intermediary between autophagy and transcriptional regulation of lipid metabolism. In rat hepatoma cells expressing alcohol-metabolizing enzymes, ethanol reduces SIRT-1 expression and impairs SIRT-1-induced deacetylation of SERBP-1, leading to an increase in fatty acid synthesis[87]. The findings that the master regulator of autophagy mTOR complex 1 (mTORC1) regulates SERBP-1 by controlling the nuclear entry of lipin-1[88], and that adiponectin protects liver cells from ethanol-induced apoptosis via induction of autophagy[89,90], indicate that ethanol metabolism affects different metabolic targets of a complex transcriptional network that controls hepatic lipid homeostasis.

Recent intriguing data correlate ethanol-induced fat accumulation with the hypoxia-inducible factors (HIFs). HIFs are the master regulators of oxygen homeostasis and regulate the expression of many genes involved in glycolysis, glucose transport, and synthesis of inflammatory and proangiogenic cytokines[89-91]. The HIF-1α protein is rapidly degraded under normoxic conditions, whereas hypoxia enhances HIF-1α levels by inhibiting its degradation[92-94]. HIF-1α has been implicated in many models of liver injury[95] and it has been reported that feeding mice for 4 wk with the Lieber-DeCarli diet increases HIF-1α mRNA, protein, and DNA-binding activity in the liver. In addition, mice lacking HIF-1α in hepatocytes have a reduced hepatic steatosis and hypertriglyceridemia[96]. Conversely, Nishiyama et al[96], with a similar molecular technology, found that activation of HIF-1α suppresses ethanol-induced fatty liver. These discordant results between the two studies is difficult to explain, although recent data in a methionine- and choline-deficient diet model showed that upregulation of HIF-1α correlated with steatotic infiltration and activation of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway[97,98]. Furthermore, the link between HIF-1α expression and the anti-lipogenic interleukin (IL)-6/signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT)3 signaling[99-101] suggests that further studies are needed to clarify the role of hypoxia and the HIF pathway in alcoholic fatty liver.

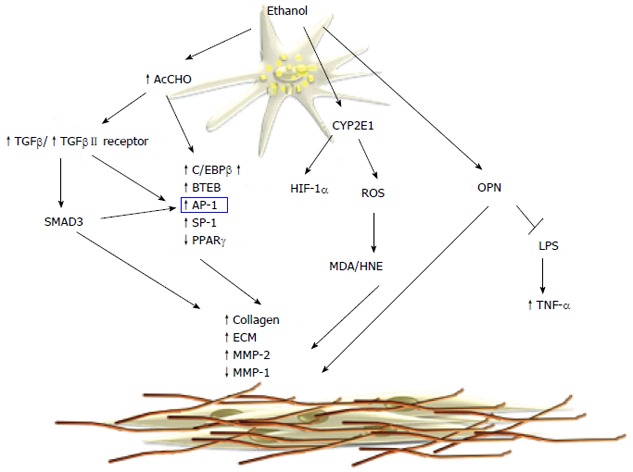

MECHANISM OF ALCOHOL-INDUCED FIBROGENESIS

Hepatic fibrosis is a major histological feature associated with the progression of chronic liver disease to cirrhosis; it is characterized by increased deposition of components of the extracellular matrix (ECM), in particular fibrillar collagens types I and III[102,103]. This process is associated with an upheaval of hepatic architecture, decreased number of endothelial cell fenestrations, and portal hypertension. The key event in hepatic fibrogenesis is hepatic stellate cell (HSC) activation. HSCs are one of the major sources of ECM in the liver and they have been identified as the precursor cell type mainly responsible for the development of liver fibrosis. Following liver injury, HSCs undergo activation that leads to the loss of the typical star-shape, fat-storing phenotype and acquisition of a myofibroblast-like phenotype consisting of increased cell proliferation, enhanced cytokine expression, and synthesis of ECM components[104,105]. Acetaldehyde is one of the main mediators of alcohol-induced fibrogenesis in the liver[106,107]. Early studies have shown that acetaldehyde can stimulate synthesis of fibrillar-forming collagens and structural glycoproteins of ECM in HSCs[108]. In addition, acetaldehyde promotes ECM remodeling by upregulation of the interstitial collagenase matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-2 and downregulation of the fibrillary collagenase MMP-1, thus resulting in the substitution of the normal ECM components with a sclerotic matrix[109,110]. In human HSCs, acetaldehyde directly induces the transcription of the α1(I) and α2(I) procollagen genes by a PKC-dependent pathway, which is involved in rapid activation of activator protein (AP)-1 transcription factors[111] (Figure 3). In human HSCs, PKC phosphorylates p70s6k by a mechanism that involves extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK)1/2 and PI3K, and all these pathways lead to collagen α2(I) gene expression[112]. Both collagen α1(I) and α2(I) promoters have an acetaldehyde-responsive element (AcRE) that includes binding sites for different transcription factors including AP-1 and specificity protein (SP)-1. AP-1 activation is postulated to be involved in the acetaldehyde-induced expression of the basic transcription element binding protein (BTEB), which is able to transactivate the rat α1(I) collagen promoter[113,114]. In addition, acetaldehyde modulates collagen α1(I) expression with a mechanism involving members of the CAAT/enhanced binding protein (C/EBP) family of transcription factors. Acetaldehyde increases DNA binding and transcriptional activity of C/EBPβ[115,116] with a mechanism that requires H2O2 production[117]. Similarly, acetaldehyde exerts its profibrogenic action by inhibition of the PPARγ transcriptional activity in HSCs[118]. PPARγ is a member of the nuclear receptor superfamily of ligand-dependent transcription factors that is predominantly expressed in adipose tissue, where it has been shown to have a key role in adipogenesis and in regulation of insulin resistance[117]. Acetaldehyde inhibits PPARγ transcriptional activity in H2O2-dependent phosphorylation of the receptor[119-121]. Acetaldehyde stimulates H2O2 production that induces a signal transduction cascade that involves cAbl, PKCδ and ERK1/2. Acetaldehyde does not induce collagen synthesis in quiescent HSCs[122] and it is not able to modulate PPARγ phosphorylation in these cells. The molecular events involved in the unresponsiveness of quiescent HSCs to fibrogenic stimuli[64], including acetaldehyde, remain speculative.

Figure 3.

Molecular mechanisms of alcoholic fibrosis. Acetaldehyde causes increased synthesis of collagen and extracellular matrix (ECM) components through the activation of the transforming growth factor (TGF)-β/SMAD3 signaling pathway. The microsomal metabolism of ethanol leads to protein adduct formation that upregulates collagen synthesis. MDA: Malondialdehyde; OPN: Osteopontin; LPS: Lipopolysaccharide; TNF-α: Tumor necrosis factor-α; MMP: Metalloproteinase; HNE: Hydroxynonenal; AP-1: Activator protein-1; SP-1: Specificity protein-1.

A different mechanism of acetaldehyde-induced fibrogenesis involved transforming growth factor (TGF)-β/small mother against decapentaplegic (SMAD) signaling. Acetaldehyde increases the secretion of TGF-β1 and induces TGF-β type II receptor expression in HSCs[123]. In cultured human HSCs it has been shown that acetaldehyde upregulates collagen α1(I) mRNA expression via two distinct mechanisms[115,124]. An early TGF-β-independent response occurs within 3 h of acetaldehyde administration in human HSCs and selectively is correlated to SMAD3 phosphorylation[107]. On the contrary, longer acetaldehyde incubation induces a TGF-β-dependent late-phase response[125] characterized by induction of latent TGF-β1 secretion, as well as type II TGF-β receptor expression[126]. Recently, acetaldehyde was shown to modulate β-catenin signaling[126] by a mechanism that inactivates nucleoredoxin (NXN) and release disheveled (DVL) from the NXN/DVL complex, leading to inactivation of glycogen synthase kinase (GSK)3B, and thereby blocks β-catenin phosphorylation and degradation. Thus, the stabilized β-catenin translocates to the nucleus where it upregulates fibrogenic genes[44,51,127,128]. It is still unclear whether the profibrogenic effects of acetaldehyde are mediated by its ability to form protein adducts. However, elevated levels of acetaldehyde-protein adducts correlate with the progression of liver fibrosis in alcoholic patients and animal experimental models[129]. Furthermore, neutrophil-derived ROS are able to induce lipid peroxidation and MDA/HNE protein adducts in HSCs, resulting in increased collagen synthesis[130].

The role of ROS and lipid peroxidation in hepatic fibrogenesis is well documented in cellular and animal models. CYP2E1-dependent generation of ROS increases collagen I protein synthesis in cocultures of hepatocytes and HSCs[131].

Recent work has shown that CYP2E1 activity correlates with ethanol-induced liver injury, lipid peroxidation, and collagen deposition[132]. CYP2E1 deletion effectively blocks ethanol-mediated lipid peroxidation and reduces liver injury, as shown in CYP2E-/- mice[133]. In contrast, transgenic mice overexpressing CYP2E1[134] enhance oxidant stress and hepatic fibrogenesis. Recently, it has been shown that that protein levels of HIF-1α and its downstream targets were elevated in the ethanol-fed CYP2E1-knock-in mice compared to the wild-type and CYP2E1 knockout mice, suggesting that CYP2E1 plays a role in ethanol-induced hypoxia. Angiogenesis is coupled with fibrogenesis during liver injury and HIF-1α contributes to CYP2E1-dependent collagen deposition and ECM remodeling. Recent studies have highlighted the role of osteopontin (OPN) in ALD and its correlation with hepatic fibrogenesis. OPN is a multifunctional protein, involved in different pathological conditions and it is associated with inflammation, autoimmunity, angiogenesis, fibrosis and cancer progression in various tissues. The OPN levels in the liver are correlated with fibrosis in patients with ALD[135]. OPN is profibrogenic by promoting HSC activation and ECM deposition in vitro and in vivo. Opn-/- mice have a significant delay in fibrosis resolution and a decreased expression of inflammatory cytokines[136]. Hepatic expression and serum levels of OPN are markedly increased in AH, compared to normal livers and other types of chronic liver diseases, and correlate with disease severity and short-term survival. Recent data show that OPN binds lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and protects against early alcohol-induced liver injury by blocking the TNF-α effects in the liver[137]. Furthermore, OPN is reported to be a downstream effector of the Hedgehog pathway, which modulates fibrosis and is involved in peculiar aspects of hepatic carcinogenesis[138].

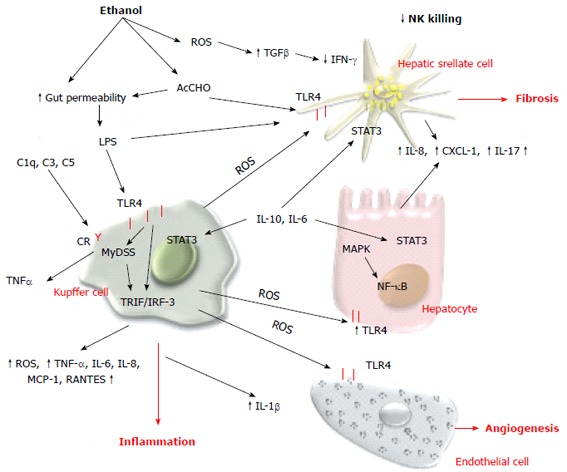

ETHANOL OXIDATION AND ACTIVATION OF INNATE AND ADAPTIVE IMMUNITY

Innate immunity has a central role in the pathogenesis of ALD, and in recent decades significant progress has been made in understanding the molecular mechanism contributing to the alcohol-dependent activation of innate immunity and inflammation. Evidence indicates that alcohol consumption causes enteric dysbiosis and bacterial overgrowth[139,140] that leads to a significant increase in gut permeability and consequently high levels of LPS in the portal circulation[141-143]. Acetaldehyde contributes to alter intestinal barrier function and to promote endotoxin translocation by disrupting tight and adherens junctions in human colonic mucosa[144] via increasing tyrosine phosphorylation of occludin and E-cadherin. The mechanism of acetaldehyde-induced alteration of gut permeability remains unclear, although acute ethanol exposure upregulates miRNA-212 in enterocytes and this is correlated with zonula occludens-1 protein downregulation[145-150]. LPS interacts with toll-like receptor (TLR)4 to activate the MyD88-dependent and -independent (TRIF/IRF-3) signaling pathways and induces Kupffer cells to release ROS and an array of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines including IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-6, IL-8, macrophage chemotactic protein (MCP)-1, and RANTES (regulated normal T cell expressed and secreted)[151]. ROS produced by Kupffer cells in response to endotoxin induces hepatic expression of TLR4[152,153], enhances transduction of TLR4-mediated signals through nuclear factor (NF)-κB, and activates mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathways[154-157]. Several data indicate that TLR4 is the main player in the development and progression of ALD. TLR4 is also expressed in HSCs and endothelial cells, and regulates alcohol-induced proangiogenic and profibrogenic responses[158].

Kupffer cell activation contributes to intrahepatic recruitment and activation of granulocytes[159-161]. Acetaldehyde and LPS[162-164] stimulate parenchymal and non-parenchymal cells to produce IL-8, chemokine CXC ligand (CXCL)1 (Gro-α) and IL-17 that directly or indirectly contribute to neutrophil infiltration and severity of AH[165-167]. An alternative pathway that contributes to expression of inflammatory cytokines is the complement system. Ethanol oxidation activates C1q, C3 and C5 components that in turn stimulate Kupffer cells to produce TNF-α[168].

A recent study indicated that IL-1β has an important role in alcohol-induced steatohepatitis. IL-1β is a potent proinflammatory cytokine whose levels are increased in patients with ALD and correlated with oxidative stress. IL-1β maturation is dependent on caspase 1 in the multiprotein complex named inflammasome. In vivo intervention with a recombinant IL-1β receptor antagonist ameliorates inflammosome-dependent alcoholic steatohepatitis in mice, suggesting a potential role of IL-1 inhibition in the treatment of ALD[169-171].

On the contrary, convincing data demonstrate that activation of innate immunity also induces elevation of anti-inflammatory and hepatoprotective cytokines such as IL-10 and IL-6. These cytokines activate STAT3 in hepatocytes and Kupffer and endothelial cells, preventing alcohol-induced liver injury and inflammation[172]. As a matter of fact, the effect of ethanol oxidative metabolism on STAT3 in the liver is complex. STAT3 is a cell survival signal and protects against hepatocellular damage. STAT3 in the liver is significantly impaired in chronic alcoholic patients compared with other different liver diseases such as chronic hepatitis C and autoimmune disease. Furthermore, ethanol oxidation is correlated with suppression of natural killer (NK) cell function in the liver. NK cells have important antifibrotic function in chronic liver disease and several studies have indicated that during liver injury there is an elevated expression of NK cell ligands. Active crosstalk between HSCs and NK cells via TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL)-TRAIL receptor interactions and a consequent production of interferon (IFN)-γ results in NK cell cytotoxicity of HSCs, thereby limiting hepatic fibrogenesis[173]. Oxidative stress in chronic ethanol consumption induces increased levels of TGF-β and reduces IFN-γ signaling, blocking NK cell killing of activated HSC[174] (Figure 4). Cell-mediated adaptive immunity is another important aspect of host defense that can be altered by alcohol and its metabolites. The mechanisms by which alcohol triggers adaptive immunity are still incompletely characterized. Chronic alcohol ingestion can interfere with antigen presentation that is required to activate T and B cells and can impair dendritic cell differentiation[175-178]. Patients with AH have increased levels of circulating antibodies against modified protein adducts with HER and lipid-peroxidation-derived aldehydes, justifying the activation of the adaptive immune response[179,180]. HER and MDA antibodies have been detected in chronically ethanol-fed rats as well as in alcohol abusers, and they are associated with detection of peripheral blood CD4+ T cells that are responsive to these adducts. The cytokines released by activated CD4+ T cells can then further stimulate Kuppfer cell activation, contributing to parenchymal injury, hepatic inflammation, and fibrogenesis.

Figure 4.

Alcohol and innate immune response. Both alcohol and acetaldehyde increase the intestinal permeability and lipopolysaccharide (LPS) level in the portal circulation. LPS binds to TLR4 and induces the proinflammatory phenotype of Kupffer cells. Acetaldehyde and LPS also stimulate parenchymal and nonparenchymal cells to produce proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines. The innate immune system also releases anti-inflammatory and hepatoprotective cytokines that activate STAT3 signaling in liver cells. ROS: Reactive oxygen species; LPS: Lipopolysaccharide; TLR4: Toll-like receptor 4; TNF-α: Tumor necrosis factor-α; IFN-γ: Interferon-γ; IL: Interleukin; NF-κB: Nuclear factor-κB.

Ethanol oxidation impairs proteasome function in macrophages through impairment of IFN-γ signaling, suppression of chymotrypsin-like proteasome activity, and the consequent composition of the immunoproteasome subunit LMP7. The proteasome suppression can alter the processing of antigenic proteins and in turn affect the presentation of these antigens to cells of adaptive immunity[181]. Furthermore, altered antigen presentation has also been shown in dendritic cells where ethanol inhibits exogenous and allogeneic antigen presentation and affects the formation of peptide-major histocompatibility complex (MHC)-II complexes, as well as altering co-stimulatory molecule expression on the cell surface[182]. Chronic ethanol consumption downregulates the number of F4/80+ cells expressing MHC-I and -II. Elimination of TLR4 abolishes the effects of ethanol on the adaptive inflammatory response in macrophages, suggesting that alterations in TLR4 function might modulate interaction between innate and adaptive immune responses in ALD[183].

ALCOHOL AND HEPATOCARCINOGENESIS

Alcohol consumption is a risk factor for epithelial cancers including HCC. Although DNA-adducts with aldehydes generated from ethanol oxidation are involved in mutagenesis and carcinogenesis[184], cirrhosis is the principal risk factor for HCC. The mechanisms that contribute to development of HCC in patients with cirrhosis are complex and include telomere shortening, activation of pathways that promote tumor cell survival, proliferation, loss of cell cycle checkpoints, and activation of oncogenes[185,186].

In addition, the immunosuppressive effects of alcohol[185,186] contribute to the development of HCC in patients with ALD[187-189]. Recently, interesting data about epigenetic regulation in ALD have been published. Epigenetic alterations by alcohol include histone modifications such as changes in acetylation, phosphorylation, hypomethylation of DNA, and alterations in different miRNAs. Deregulation of miRNA biogenesis has been found in nonviral HCC subtypes, and ethanol oxidation influences the expression of miR-217, miR-155 and miR-212[190]. These modifications can be induced by oxidative stress that results in altered recruitment of transcriptional machinery and abnormal gene expression. Epigenetic mechanisms play an extensive role in the development of liver cancer, contributing to the reversion of normal liver cells into progenitor and stem cells. In the alcohol-preferring rat model, heavy alcohol ingestion amplifies age-related hepatocarcinogenesis but does not cause appreciable liver inflammation or fibrosis. In these animals, alcohol exposure activates the Hedgehog pathway and induces related procarcinogenic processes such as deregulated progenitor expansion, and epithelial-mesenchymal transition[190,191]. In vivo and in vitro alcohol exposure induces chromosomal aberration and mitotic targets such as cyclin B, aurora kinase A, and phosphorylation of γ-tubulin[191].

THERAPEUTIC OPTIONS

Alcohol cessation is the mainstay of therapy for patients with all stages of ALD, however different drugs that target specific pathways have been proposed for ALD treatment. Oxidative stress plays a central role in the pathogenesis of ALD, and several preclinical and clinical trials with antioxidant agents have been performed. N-acetylcysteine (NAC), S-adenosyl methionine (SAMe), Silybum marianum (Cardus marianum L.), and vitamin E have been tested either in combination with glucocorticoids or as a monotherapy. NAC and SAMe have failed to demonstrate any benefit in the outcome of ALD[192,193] but may offer additional incremental benefit when combined with prednisolone[194]. S. marianum or milk thistle (MT) is the most well-researched plant in the treatment of liver disease and has been used to treat ALD and acute and chronic viral hepatitis. In baboons, the active principle called silymarin, administered for 3 years, retarded the development of alcohol-induced hepatic fibrosis[195]. The major mechanism of its hepatoprotective activity is the inhibition of hepatic NF-κB activation. In addition, silymarin has antifibrotic activity in rodents and inhibits the expression of pro-collagen-α1(I) and tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1 via downregulation of TGF-β1 mRNA[196]. Silymarin acts as antioxidant; it reduces free radical production and lipid peroxidation and markedly increases the expression of superoxide dismutase in lymphocytes of patients with alcoholic cirrhosis[197,198]. Silymarin also shows anti-inflammatory and antiangiogenic effects[199]. However, clinical trials have not been encouraging. In a double-blind comparative study of 106 patients with histological alcoholic hepatitis, MT showed no positive effects on liver biopsy[200]. The Cochrane Library does not recommend the use of MT for acute or chronic alcoholic liver injury and recommends conducting new randomized controlled clinical trials[201].

Studies with other antioxidants such as vitamin E and propylthiouracil have likewise been disappointing[194,202-204], while animal data on Isoorientin[205] and Notoginseng[206] are encouraging but further studies are needed.

Deregulation of PPAR transcriptional activity during alcohol consumption suggests a possible role of PPAR agonists for ALD treatment. In alcohol-treated mice, the PPARγ agonists, rosiglitazone and pioglitazone, increase circulating levels of adiponectin and expression of its receptors in the liver that is associated with SIRT1-AMPK signaling activation. This pathway correlates with the enhanced expression of fatty acid oxidation enzymes and reduction of alcohol-induced steatosis[207-213]. In addition, PPARγ agonists have anti-inflammatory effects that reduce cytokine expression such as TNF-α, IL-6 and MCP-1 in alcohol-fed mice[207].

The altered intestinal microflora during chronic alcohol consumption has recently been focused as a therapeutic target in ALD. Chronic ethanol feeding causes a decline in the abundance of Bacteriodetes and Firmicutes phyla, with a proportional increase in the Gram-negative Proteobacteria. Oral administration of Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG attenuates the established alcohol-induced hepatic steatosis and liver injury in mouse models of ALD[208]. Probiotics create an anti-inflammatory milieu, decrease production of proinflammatory bacterial products, and improve barrier integrity leading to a decrease of endotoxin release. These protective effects are correlated with the prevention of alcohol-induced oxidative stress, suppression of CYP2E1 expression, inactivation of TLR4, and inhibition of p38 MAPK phosphorylation, which leads to a significant decrease in NF-κB activation and TNF-α production[209]. Results from a placebo-controlled trial have recently shown that the nonabsorbable antibiotic rifaximin modifies the gut microbiota, and protects alcoholic patients from hepatic encephalopathy[210,211]. Similar results have been seen with TLR4 antagonists, which have been recently studied as therapeutic agents for chronic liver diseases, including ALD[212].

Anti-inflammatory therapy remains the most attractive approach for ALD. Glucocorticoid therapy was first demonstrated to be beneficial in patients with severe AH in 1978[213]. Steroids ameliorate liver inflammation and systemic inflammatory responses, however, this treatment inhibits liver regeneration and does not promote liver repair in patients with ALD, which may contribute to the lack of long-term survival benefit in patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis. On the contrary, Anti-TNF-α therapy has demonstrated positive effects in animal models of alcoholic liver injury. Patients with severe AH have high concentrations of TNF-α[214] and the serum levels of this cytokine predict short-[215] and long-term survival[216]. In rats with experimental alcoholic steatohepatitis, infliximab, an anti-TNF-α mouse/human chimeric antibody, acts as an effective hepatoprotective and anti-inflammatory agent, and significantly improves hepatic inflammation[217]. However, a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial in patients with AH, using etanercept, a p75-soluble TNF receptor, failed because of the high mortality rate[218]. In severe AH, single-dose infliximab is associated with improved survival, but infection remains the main complication and large randomized controlled trials are needed before this anti-TNF-α agent can be recommended for AH[219]. A moderate effect on TNF-α levels was also demonstrated using pentoxifylline, a nonselective phosphodiesterase inhibitor[220-222] that exerts antifibrogenic action via downregulation of TGF-β1 expression[223].

Interesting data about the protective role of IL-22 in ALD have recently been published. IL-22 is a member of the IL-10-like cytokine family that is produced by T-helper 17 and NK cells. IL-22 has an important role in controlling bacterial infection, homeostasis, and tissue repair[224,225]. The biological effects of IL-22 are mediated through binding to IL-22 receptors and consequent activation of the STAT3 signaling pathway[224]. IL-22 protects against liver injury[226-231], reduces fat accumulation and collagen deposition[231-234] and promotes liver regeneration[235,236] in rodent models of ALD. The antifibrotic properties of IL-22 depend on the significant increase of STAT-mediated HSC senescence, as demonstrated by the increase of β-galactosidase-positive HSCs in IL-22-treated animals[237]. Data showing elevated IL-22 expression in ALD patients suggest that IL-22 administration might be an ideal therapy for alcoholic liver injury[238].

Inhibition of hepatocyte apoptosis was recently suggested as an alternative and attractive approach to reduce liver inflammation during alcohol consumption. The pan-caspase inhibitor emricasan was found to suppress hepatocyte apoptosis, inhibit proinflammatory caspases, and prevent fibrogenesis in murine models of ethanol-induced liver injury[239].

Many other chemokines (e.g., CXCL5, CXCL6 and CXCL4) and cytokines (e.g., IL-1, IL-8 and OPN) are markedly upregulated in AH and are implicated in the hepatic neutrophil infiltration[162-164]. Reagents that target CXC chemokines are currently under investigation in different stages of ALD.

CONCLUSION

Chronic alcohol consumption is a major cause of advanced liver disease worldwide. In this review, we have highlighted the role of alcohol abuse in liver disease by examining ethanol metabolism. Both acetaldehyde and ROS act directly on the transcriptional network that regulates lipid metabolism and fibrogenic response during liver injury. These toxic agents alter the intestinal permeability and consequently increase LPS, which leads to the activation of innate and adaptive immunity. LPS activation of TRL4 stimulates Kupffer cells to release ROS and cytokines that attract neutrophils, inhibits NK function, and alter allogenic antigen presentation. In addition, acetaldehyde and ROS promote a chronic inflammatory state that has a direct role in the development of HCC. Furthermore, lipid peroxidation products and the formation of protein and DNA adducts interfere with methylation, synthesis and repair of DNA and promote mutagenesis. The specific pathways involved in ethanol-induced liver damage select new therapeutic agents such as thiazolidinediones, anti-TNF-α molecules and IL-22 that have shown promising effects in basic and translational research studies. Future efforts should be directed to test the new therapeutic approaches in controlled clinical trials in patients with moderate and severe ALD.

Footnotes

P- Reviewer: Bubnov RV, Guerrieri F, Gatselis NK, Lukacs-Kornek V S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: Kerr C E- Editor: Liu XM

References

- 1.Miller AM, Horiguchi N, Jeong WI, Radaeva S, Gao B. Molecular mechanisms of alcoholic liver disease: innate immunity and cytokines. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2011;35:787–793. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01399.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wilfred de Alwis NM, Day CP. Genetics of alcoholic liver disease and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Semin Liver Dis. 2007;27:44–54. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-960170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kimura M, Miyakawa T, Matsushita S, So M, Higuchi S. Gender differences in the effects of ADH1B and ALDH2 polymorphisms on alcoholism. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2011;35:1923–1927. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01543.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bosron WF, Ehrig T, Li TK. Genetic factors in alcohol metabolism and alcoholism. Semin Liver Dis. 1993;13:126–135. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1007344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Crabb DW. Ethanol oxidizing enzymes: roles in alcohol metabolism and alcoholic liver disease. Prog Liver Dis. 1995;13:151–172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eriksson CJ, Fukunaga T, Sarkola T, Chen WJ, Chen CC, Ju JM, Cheng AT, Yamamoto H, Kohlenberg-Müller K, Kimura M, et al. Functional relevance of human adh polymorphism. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2001;25:157S–163S. doi: 10.1097/00000374-200105051-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zintzaras E, Stefanidis I, Santos M, Vidal F. Do alcohol-metabolizing enzyme gene polymorphisms increase the risk of alcoholism and alcoholic liver disease? Hepatology. 2006;43:352–361. doi: 10.1002/hep.21023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Freeman TL, Tuma DJ, Thiele GM, Klassen LW, Worrall S, Niemelä O, Parkkila S, Emery PW, Preedy VR. Recent advances in alcohol-induced adduct formation. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2005;29:1310–1316. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000171484.52201.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Niemelä O. Acetaldehyde adducts in circulation. Novartis Found Symp. 2007;285:183–192; discussion 193-197. doi: 10.1002/9780470511848.ch13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tuma DJ. Role of malondialdehyde-acetaldehyde adducts in liver injury. Free Radic Biol Med. 2002;32:303–308. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(01)00742-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tuma DJ, Casey CA. Dangerous byproducts of alcohol breakdown--focus on adducts. Alcohol Res Health. 2003;27:285–290. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brooks PJ, Theruvathu JA. DNA adducts from acetaldehyde: implications for alcohol-related carcinogenesis. Alcohol. 2005;35:187–193. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2005.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Seitz HK, Becker P. Alcohol metabolism and cancer risk. Alcohol Res Health. 2007;30:38–41, 44-47. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Biewald J, Nilius R, Langner J. Occurrence of acetaldehyde protein adducts formed in various organs of chronically ethanol fed rats: an immunohistochemical study. Int J Mol Med. 1998;2:389–396. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2.4.389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Seitz HK, Meier P. The role of acetaldehyde in upper digestive tract cancer in alcoholics. Transl Res. 2007;149:293–297. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2006.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bondy SC. Ethanol toxicity and oxidative stress. Toxicol Lett. 1992;63:231–241. doi: 10.1016/0378-4274(92)90086-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bailey SM, Cunningham CC. Contribution of mitochondria to oxidative stress associated with alcoholic liver disease. Free Radic Biol Med. 2002;32:11–16. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(01)00769-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chance B, Sies H, Boveris A. Hydroperoxide metabolism in mammalian organs. Physiol Rev. 1979;59:527–605. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1979.59.3.527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.de Groot H. Reactive oxygen species in tissue injury. Hepatogastroenterology. 1994;41:328–332. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nakazawa H, Genka C, Fujishima M. Pathological aspects of active oxygens/free radicals. Jpn J Physiol. 1996;46:15–32. doi: 10.2170/jjphysiol.46.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Toyokuni S. Reactive oxygen species-induced molecular damage and its application in pathology. Pathol Int. 1999;49:91–102. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1827.1999.00829.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guengerich FP, Beaune PH, Umbenhauer DR, Churchill PF, Bork RW, Dannan GA, Knodell RG, Lloyd RS, Martin MV. Cytochrome P-450 enzymes involved in genetic polymorphism of drug oxidation in humans. Biochem Soc Trans. 1987;15:576–578. doi: 10.1042/bst0150576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lieber CS. Metabolism of ethanol and alcoholism: racial and acquired factors. Ann Intern Med. 1972;76:326–327. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-76-2-326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lieber CS, DeCarli LM. The role of the hepatic microsomal ethanol oxidizing system (MEOS) for ethanol metabolism in vivo. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1972;181:279–287. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lieber CS. Cytochrome P-4502E1: its physiological and pathological role. Physiol Rev. 1997;77:517–544. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1997.77.2.517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hansson T, Tindberg N, Ingelman-Sundberg M, Köhler C. Regional distribution of ethanol-inducible cytochrome P450 IIE1 in the rat central nervous system. Neuroscience. 1990;34:451–463. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(90)90154-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Donohue TM, Cederbaum AI, French SW, Barve S, Gao B, Osna NA. Role of the proteasome in ethanol-induced liver pathology. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2007;31:1446–1459. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00454.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Osna NA, Donohue TM. Implication of altered proteasome function in alcoholic liver injury. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:4931–4937. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i37.4931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lu Y, Cederbaum AI. CYP2E1 and oxidative liver injury by alcohol. Free Radic Biol Med. 2008;44:723–738. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yun YP, Casazza JP, Sohn DH, Veech RL, Song BJ. Pretranslational activation of cytochrome P450IIE during ketosis induced by a high fat diet. Mol Pharmacol. 1992;41:474–479. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Raucy JL, Lasker JM, Kraner JC, Salazar DE, Lieber CS, Corcoran GB. Induction of cytochrome P450IIE1 in the obese overfed rat. Mol Pharmacol. 1991;39:275–280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Woodcroft KJ, Hafner MS, Novak RF. Insulin signaling in the transcriptional and posttranscriptional regulation of CYP2E1 expression. Hepatology. 2002;35:263–273. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.30691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.De Waziers I, Garlatti M, Bouguet J, Beaune PH, Barouki R. Insulin down-regulates cytochrome P450 2B and 2E expression at the post-transcriptional level in the rat hepatoma cell line. Mol Pharmacol. 1995;47:474–479. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Peng HM, Coon MJ. Regulation of rabbit cytochrome P450 2E1 expression in HepG2 cells by insulin and thyroid hormone. Mol Pharmacol. 1998;54:740–747. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Terelius Y, Norsten-Höög C, Cronholm T, Ingelman-Sundberg M. Acetaldehyde as a substrate for ethanol-inducible cytochrome P450 (CYP2E1) Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1991;179:689–694. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(91)91427-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wu YS, Salmela KS, Lieber CS. Microsomal acetaldehyde oxidation is negligible in the presence of ethanol. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1998;22:1165–1169. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brooks PJ. DNA damage, DNA repair, and alcohol toxicity--a review. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1997;21:1073–1082. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cederbaum AI. CYP2E1--biochemical and toxicological aspects and role in alcohol-induced liver injury. Mt Sinai J Med. 2006;73:657–672. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Breen AP, Murphy JA. Reactions of oxyl radicals with DNA. Free Radic Biol Med. 1995;18:1033–1077. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(94)00209-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nagata K, Suzuki H, Sakaguchi S. Common pathogenic mechanism in development progression of liver injury caused by non-alcoholic or alcoholic steatohepatitis. J Toxicol Sci. 2007;32:453–468. doi: 10.2131/jts.32.453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Albano E. Free radical mechanisms in immune reactions associated with alcoholic liver disease. Free Radic Biol Med. 2002;32:110–114. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(01)00773-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Balbo S, Hashibe M, Gundy S, Brennan P, Canova C, Simonato L, Merletti F, Richiardi L, Agudo A, Castellsagué X, et al. N2-ethyldeoxyguanosine as a potential biomarker for assessing effects of alcohol consumption on DNA. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17:3026–3032. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Druesne-Pecollo N, Tehard B, Mallet Y, Gerber M, Norat T, Hercberg S, Latino-Martel P. Alcohol and genetic polymorphisms: effect on risk of alcohol-related cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:173–180. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70019-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tuma DJ, Thiele GM, Xu D, Klassen LW, Sorrell MF. Acetaldehyde and malondialdehyde react together to generate distinct protein adducts in the liver during long-term ethanol administration. Hepatology. 1996;23:872–880. doi: 10.1002/hep.510230431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Niemelä O. Aldehyde-protein adducts in the liver as a result of ethanol-induced oxidative stress. Front Biosci. 1999;4:D506–D513. doi: 10.2741/niemela. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Duryee MJ, Klassen LW, Jones BL, Willis MS, Tuma DJ, Thiele GM. Increased immunogenicity to P815 cells modified with malondialdehyde and acetaldehyde. Int Immunopharmacol. 2008;8:1112–1118. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2008.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Viitala K, Israel Y, Blake JE, Niemelä O. Serum IgA, IgG, and IgM antibodies directed against acetaldehyde-derived epitopes: relationship to liver disease severity and alcohol consumption. Hepatology. 1997;25:1418–1424. doi: 10.1002/hep.510250619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rolla R, Vay D, Mottaran E, Parodi M, Traverso N, Aricó S, Sartori M, Bellomo G, Klassen LW, Thiele GM, et al. Detection of circulating antibodies against malondialdehyde-acetaldehyde adducts in patients with alcohol-induced liver disease. Hepatology. 2000;31:878–884. doi: 10.1053/he.2000.5373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Li CJ, Nanji AA, Siakotos AN, Lin RC. Acetaldehyde-modified and 4-hydroxynonenal-modified proteins in the livers of rats with alcoholic liver disease. Hepatology. 1997;26:650–657. doi: 10.1002/hep.510260317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Niemelä O, Parkkila S, Pasanen M, Iimuro Y, Bradford B, Thurman RG. Early alcoholic liver injury: formation of protein adducts with acetaldehyde and lipid peroxidation products, and expression of CYP2E1 and CYP3A. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1998;22:2118–2124. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1998.tb05925.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Holstege A, Bedossa P, Poynard T, Kollinger M, Chaput JC, Houglum K, Chojkier M. Acetaldehyde-modified epitopes in liver biopsy specimens of alcoholic and nonalcoholic patients: localization and association with progression of liver fibrosis. Hepatology. 1994;19:367–374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Niemelä O. Distribution of ethanol-induced protein adducts in vivo: relationship to tissue injury. Free Radic Biol Med. 2001;31:1533–1538. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(01)00744-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Thurman RG, Handler JA. New perspectives in catalase-dependent ethanol metabolism. Drug Metab Rev. 1989;20:679–688. doi: 10.3109/03602538909103570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zimatkin SM, Liopo AV, Deitrich RA. Distribution and kinetics of ethanol metabolism in rat brain. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1998;22:1623–1627. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Deng XS, Deitrich RA. Putative role of brain acetaldehyde in ethanol addiction. Curr Drug Abuse Rev. 2008;1:3–8. doi: 10.2174/1874473710801010003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Grunnet N, Jensen F, Kondrup J, Dich J. Effect of ethanol on fatty acid metabolism in cultured hepatocytes: dependency on incubation time and fatty acid concentration. Alcohol. 1985;2:157–161. doi: 10.1016/0741-8329(85)90035-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Crabb DW, Liangpunsakul S. Alcohol and lipid metabolism. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;21 Suppl 3:S56–S60. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2006.04582.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Baraona E, Lieber CS. Effects of ethanol on lipid metabolism. J Lipid Res. 1979;20:289–315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Galli A, Price D, Crabb D. High-level expression of rat class I alcohol dehydrogenase is sufficient for ethanol-induced fat accumulation in transduced HeLa cells. Hepatology. 1999;29:1164–1170. doi: 10.1002/hep.510290420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Salaspuro MP, Shaw S, Jayatilleke E, Ross WA, Lieber CS. Attenuation of the ethanol-induced hepatic redox change after chronic alcohol consumption in baboons: metabolic consequences in vivo and in vitro. Hepatology. 1981;1:33–38. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840010106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Everett L, Galli A, Crabb D. The role of hepatic peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs) in health and disease. Liver. 2000;20:191–199. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0676.2000.020003191.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Crabb DW, Galli A, Fischer M, You M. Molecular mechanisms of alcoholic fatty liver: role of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha. Alcohol. 2004;34:35–38. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2004.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Fischer M, You M, Matsumoto M, Crabb DW. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha (PPARalpha) agonist treatment reverses PPARalpha dysfunction and abnormalities in hepatic lipid metabolism in ethanol-fed mice. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:27997–28004. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302140200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nanji AA, Dannenberg AJ, Jokelainen K, Bass NM. Alcoholic liver injury in the rat is associated with reduced expression of peroxisome proliferator-alpha (PPARalpha)-regulated genes and is ameliorated by PPARalpha activation. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2004;310:417–424. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.064717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lu Y, Zhuge J, Wang X, Bai J, Cederbaum AI. Cytochrome P450 2E1 contributes to ethanol-induced fatty liver in mice. Hepatology. 2008;47:1483–1494. doi: 10.1002/hep.22222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.You M, Fischer M, Deeg MA, Crabb DW. Ethanol induces fatty acid synthesis pathways by activation of sterol regulatory element-binding protein (SREBP) J Biol Chem. 2002;277:29342–29347. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202411200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ji C, Kaplowitz N. Betaine decreases hyperhomocysteinemia, endoplasmic reticulum stress, and liver injury in alcohol-fed mice. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:1488–1499. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(03)00276-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wang T, Yang P, Zhan Y, Xia L, Hua Z, Zhang J. Deletion of circadian gene Per1 alleviates acute ethanol-induced hepatotoxicity in mice. Toxicology. 2013;314:193–201. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2013.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Thomes PG, Osna NA, Davis JS, Donohue TM. Cellular steatosis in ethanol oxidizing-HepG2 cells is partially controlled by the transcription factor, early growth response-1. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2013;45:454–463. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2012.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sharara-Chami RI, Zhou Y, Ebert S, Pacak K, Ozcan U, Majzoub JA. Epinephrine deficiency results in intact glucose counter-regulation, severe hepatic steatosis and possible defective autophagy in fasting mice. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2012;44:905–913. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2012.02.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Galligan JJ, Smathers RL, Shearn CT, Fritz KS, Backos DS, Jiang H, Franklin CC, Orlicky DJ, Maclean KN, Petersen DR. Oxidative Stress and the ER Stress Response in a Murine Model for Early-Stage Alcoholic Liver Disease. J Toxicol. 2012;2012:207594. doi: 10.1155/2012/207594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yang L, Wu D, Wang X, Cederbaum AI. Cytochrome P4502E1, oxidative stress, JNK, and autophagy in acute alcohol-induced fatty liver. Free Radic Biol Med. 2012;53:1170–1180. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2012.06.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zeng T, Zhang CL, Song FY, Zhao XL, Yu LH, Zhu ZP, Xie KQ. PI3K/Akt pathway activation was involved in acute ethanol-induced fatty liver in mice. Toxicology. 2012;296:56–66. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2012.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.You M, Matsumoto M, Pacold CM, Cho WK, Crabb DW. The role of AMP-activated protein kinase in the action of ethanol in the liver. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:1798–1808. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.09.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.García-Villafranca J, Guillén A, Castro J. Ethanol consumption impairs regulation of fatty acid metabolism by decreasing the activity of AMP-activated protein kinase in rat liver. Biochimie. 2008;90:460–466. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2007.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Tomita K, Tamiya G, Ando S, Kitamura N, Koizumi H, Kato S, Horie Y, Kaneko T, Azuma T, Nagata H, et al. AICAR, an AMPK activator, has protective effects on alcohol-induced fatty liver in rats. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2005;29:240S–245S. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000191126.11479.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hu M, Wang F, Li X, Rogers CQ, Liang X, Finck BN, Mitra MS, Zhang R, Mitchell DA, You M. Regulation of hepatic lipin-1 by ethanol: role of AMP-activated protein kinase/sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1 signaling in mice. Hepatology. 2012;55:437–446. doi: 10.1002/hep.24708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Yang Z, Klionsky DJ. Eaten alive: a history of macroautophagy. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12:814–822. doi: 10.1038/ncb0910-814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Czaja MJ. Functions of autophagy in hepatic and pancreatic physiology and disease. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:1895–1908. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.04.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Wu D, Wang X, Zhou R, Yang L, Cederbaum AI. Alcohol steatosis and cytotoxicity: the role of cytochrome P4502E1 and autophagy. Free Radic Biol Med. 2012;53:1346–1357. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2012.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Donohue TM. Autophagy and ethanol-induced liver injury. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:1178–1185. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.1178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Dolganiuc A, Thomes PG, Ding WX, Lemasters JJ, Donohue TM. Autophagy in alcohol-induced liver diseases. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2012;36:1301–1308. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2012.01742.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Ding WX, Li M, Chen X, Ni HM, Lin CW, Gao W, Lu B, Stolz DB, Clemens DL, Yin XM. Autophagy reduces acute ethanol-induced hepatotoxicity and steatosis in mice. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:1740–1752. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.07.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ni HM, Du K, You M, Ding WX. Critical role of FoxO3a in alcohol-induced autophagy and hepatotoxicity. Am J Pathol. 2013;183:1815–1825. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2013.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.You M, Liang X, Ajmo JM, Ness GC. Involvement of mammalian sirtuin 1 in the action of ethanol in the liver. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2008;294:G892–G898. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00575.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Lieber CS, Leo MA, Wang X, Decarli LM. Effect of chronic alcohol consumption on Hepatic SIRT1 and PGC-1alpha in rats. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;370:44–48. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Peterson TR, Sengupta SS, Harris TE, Carmack AE, Kang SA, Balderas E, Guertin DA, Madden KL, Carpenter AE, Finck BN, et al. mTOR complex 1 regulates lipin 1 localization to control the SREBP pathway. Cell. 2011;146:408–420. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.06.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Nepal S, Park PH. Activation of autophagy by globular adiponectin attenuates ethanol-induced apoptosis in HepG2 cells: involvement of AMPK/FoxO3A axis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1833:2111–2125. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2013.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Formenti F, Constantin-Teodosiu D, Emmanuel Y, Cheeseman J, Dorrington KL, Edwards LM, Humphreys SM, Lappin TR, McMullin MF, McNamara CJ, et al. Regulation of human metabolism by hypoxia-inducible factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:12722–12727. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002339107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Semenza GL. Regulation of mammalian O2 homeostasis by hypoxia-inducible factor 1. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1999;15:551–578. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.15.1.551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Semenza GL. Hypoxia-inducible factors in physiology and medicine. Cell. 2012;148:399–408. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Nath B, Szabo G. Hypoxia and hypoxia inducible factors: diverse roles in liver diseases. Hepatology. 2012;55:622–633. doi: 10.1002/hep.25497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Copple BL, Bai S, Burgoon LD, Moon JO. Hypoxia-inducible factor-1α regulates the expression of genes in hypoxic hepatic stellate cells important for collagen deposition and angiogenesis. Liver Int. 2011;31:230–244. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2010.02347.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Copple BL, Bustamante JJ, Welch TP, Kim ND, Moon JO. Hypoxia-inducible factor-dependent production of profibrotic mediators by hypoxic hepatocytes. Liver Int. 2009;29:1010–1021. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2009.02015.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Nath B, Levin I, Csak T, Petrasek J, Mueller C, Kodys K, Catalano D, Mandrekar P, Szabo G. Hepatocyte-specific hypoxia-inducible factor-1α is a determinant of lipid accumulation and liver injury in alcohol-induced steatosis in mice. Hepatology. 2011;53:1526–1537. doi: 10.1002/hep.24256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Nishiyama Y, Goda N, Kanai M, Niwa D, Osanai K, Yamamoto Y, Senoo-Matsuda N, Johnson RS, Miura S, Kabe Y, et al. HIF-1α induction suppresses excessive lipid accumulation in alcoholic fatty liver in mice. J Hepatol. 2012;56:441–447. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Yang YY, Lee PC, Huang YT, Lee WP, Kuo YJ, Lee KC, Hsieh YC, Lee TY, Lin HC. Involvement of the HIF-1α and Wnt/β-catenin pathways in the protective effects of losartan on fatty liver graft with ischaemia/reperfusion injury. Clin Sci (Lond) 2014;126:163–174. doi: 10.1042/CS20130025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Anglesio MS, George J, Kulbe H, Friedlander M, Rischin D, Lemech C, Power J, Coward J, Cowin PA, House CM, et al. IL6-STAT3-HIF signaling and therapeutic response to the angiogenesis inhibitor sunitinib in ovarian clear cell cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:2538–2548. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-3314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Milani S, Herbst H, Schuppan D, Hahn EG, Stein H. In situ hybridization for procollagen types I, III and IV mRNA in normal and fibrotic rat liver: evidence for predominant expression in nonparenchymal liver cells. Hepatology. 1989;10:84–92. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840100117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Bataller R, Sancho-Bru P, Ginès P, Brenner DA. Liver fibrogenesis: a new role for the renin-angiotensin system. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2005;7:1346–1355. doi: 10.1089/ars.2005.7.1346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Friedman SL. Mechanisms of hepatic fibrogenesis. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:1655–1669. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Guyot C, Lepreux S, Combe C, Doudnikoff E, Bioulac-Sage P, Balabaud C, Desmoulière A. Hepatic fibrosis and cirrhosis: the (myo)fibroblastic cell subpopulations involved. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2006;38:135–151. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2005.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Gressner AM. Transdifferentiation of hepatic stellate cells (Ito cells) to myofibroblasts: a key event in hepatic fibrogenesis. Kidney Int Suppl. 1996;54:S39–S45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Mello T, Ceni E, Surrenti C, Galli A. Alcohol induced hepatic fibrosis: role of acetaldehyde. Mol Aspects Med. 2008;29:17–21. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2007.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Lieber CS. Hepatic, metabolic, and nutritional disorders of alcoholism: from pathogenesis to therapy. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci. 2000;37:551–584. doi: 10.1080/10408360091174312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Moshage H, Casini A, Lieber CS. Acetaldehyde selectively stimulates collagen production in cultured rat liver fat-storing cells but not in hepatocytes. Hepatology. 1990;12:511–518. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840120311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Casini A, Cunningham M, Rojkind M, Lieber CS. Acetaldehyde increases procollagen type I and fibronectin gene transcription in cultured rat fat-storing cells through a protein synthesis-dependent mechanism. Hepatology. 1991;13:758–765. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Casini A, Ceni E, Salzano R, Schuppan D, Milani S, Pellegrini G, Surrenti C. Regulation of undulin synthesis and gene expression in human fat-storing cells by acetaldehyde and transforming growth factor-beta 1: comparison with fibronectin. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1994;199:1019–1026. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1994.1331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Casini A, Galli G, Salzano R, Ceni E, Franceschelli F, Rotella CM, Surrenti C. Acetaldehyde induces c-fos and c-jun proto-oncogenes in fat-storing cell cultures through protein kinase C activation. Alcohol Alcohol. 1994;29:303–314. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Anania FA, Womack L, Potter JJ, Mezey E. Acetaldehyde enhances murine alpha2(I) collagen promoter activity by Ca2+-independent protein kinase C activation in cultured rat hepatic stellate cells. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1999;23:279–284. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Svegliati-Baroni G, Ridolfi F, Di Sario A, Saccomanno S, Bendia E, Benedetti A, Greenwel P. Intracellular signaling pathways involved in acetaldehyde-induced collagen and fibronectin gene expression in human hepatic stellate cells. Hepatology. 2001;33:1130–1140. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.23788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Chen A, Davis BH. The DNA binding protein BTEB mediates acetaldehyde-induced, jun N-terminal kinase-dependent alphaI(I) collagen gene expression in rat hepatic stellate cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:2818–2826. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.8.2818-2826.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Attard FA, Wang L, Potter JJ, Rennie-Tankersley L, Mezey E. CCAAT/enhancer binding protein beta mediates the activation of the murine alpha1(I) collagen promoter by acetaldehyde. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2000;378:57–64. doi: 10.1006/abbi.2000.1803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Anania FA, Potter JJ, Rennie-Tankersley L, Mezey E. Effects of acetaldehyde on nuclear protein binding to the nuclear factor I consensus sequence in the alpha 2(I) collagen promoter. Hepatology. 1995;21:1640–1648. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Greenwel P, Domínguez-Rosales JA, Mavi G, Rivas-Estilla AM, Rojkind M. Hydrogen peroxide: a link between acetaldehyde-elicited alpha1(I) collagen gene up-regulation and oxidative stress in mouse hepatic stellate cells. Hepatology. 2000;31:109–116. doi: 10.1002/hep.510310118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.García-Trevijano ER, Iraburu MJ, Fontana L, Domínguez-Rosales JA, Auster A, Covarrubias-Pinedo A, Rojkind M. Transforming growth factor beta1 induces the expression of alpha1(I) procollagen mRNA by a hydrogen peroxide-C/EBPbeta-dependent mechanism in rat hepatic stellate cells. Hepatology. 1999;29:960–970. doi: 10.1002/hep.510290346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Ceni E, Crabb DW, Foschi M, Mello T, Tarocchi M, Patussi V, Moraldi L, Moretti R, Milani S, Surrenti C, et al. Acetaldehyde inhibits PPARgamma via H2O2-mediated c-Abl activation in human hepatic stellate cells. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:1235–1252. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Kintscher U, Law RE. PPARgamma-mediated insulin sensitization: the importance of fat versus muscle. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2005;288:E287–E291. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00440.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Sato T, Gordon GR, Murayama N, Kato R, Tyson CA. Influence of acetaldehyde and ethanol on rat hepatic lipocyte characteristics in primary culture. Cell Biol Int. 1995;19:879–881. doi: 10.1006/cbir.1995.1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Friedman SL. Acetaldehyde and alcoholic fibrogenesis: fuel to the fire, but not the spark. Hepatology. 1990;12:609–612. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840120326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Maher JJ, Zia S, Tzagarakis C. Acetaldehyde-induced stimulation of collagen synthesis and gene expression is dependent on conditions of cell culture: studies with rat lipocytes and fibroblasts. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1994;18:403–409. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1994.tb00033.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Anania FA, Potter JJ, Rennie-Tankersley L, Mezey E. Activation by acetaldehyde of the promoter of the mouse alpha2(I) collagen gene when transfected into rat activated stellate cells. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1996;331:187–193. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1996.0297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Svegliati-Baroni G, Inagaki Y, Rincon-Sanchez AR, Else C, Saccomanno S, Benedetti A, Ramirez F, Rojkind M. Early response of alpha2(I) collagen to acetaldehyde in human hepatic stellate cells is TGF-beta independent. Hepatology. 2005;42:343–352. doi: 10.1002/hep.20798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Weng HL, Liu Y, Chen JL, Huang T, Xu LJ, Godoy P, Hu JH, Zhou C, Stickel F, Marx A, et al. The etiology of liver damage imparts cytokines transforming growth factor beta1 or interleukin-13 as driving forces in fibrogenesis. Hepatology. 2009;50:230–243. doi: 10.1002/hep.22934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Chen A. Acetaldehyde stimulates the activation of latent transforming growth factor-beta1 and induces expression of the type II receptor of the cytokine in rat cultured hepatic stellate cells. Biochem J. 2002;368:683–693. doi: 10.1042/BJ20020949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Arellanes-Robledo J, Reyes-Gordillo K, Shah R, Domínguez-Rosales JA, Hernández-Nazara ZH, Ramirez F, Rojkind M, Lakshman MR. Fibrogenic actions of acetaldehyde are β-catenin dependent but Wingless independent: a critical role of nucleoredoxin and reactive oxygen species in human hepatic stellate cells. Free Radic Biol Med. 2013;65:1487–1496. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2013.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Niemelä O, Parkkila S, Ylä-Herttuala S, Villanueva J, Ruebner B, Halsted CH. Sequential acetaldehyde production, lipid peroxidation, and fibrogenesis in micropig model of alcohol-induced liver disease. Hepatology. 1995;22:1208–1214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Casini A, Galli A, Pignalosa P, Frulloni L, Grappone C, Milani S, Pederzoli P, Cavallini G, Surrenti C. Collagen type I synthesized by pancreatic periacinar stellate cells (PSC) co-localizes with lipid peroxidation-derived aldehydes in chronic alcoholic pancreatitis. J Pathol. 2000;192:81–89. doi: 10.1002/1096-9896(2000)9999:9999<::AID-PATH675>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Casini A, Ceni E, Salzano R, Biondi P, Parola M, Galli A, Foschi M, Caligiuri A, Pinzani M, Surrenti C. Neutrophil-derived superoxide anion induces lipid peroxidation and stimulates collagen synthesis in human hepatic stellate cells: role of nitric oxide. Hepatology. 1997;25:361–367. doi: 10.1053/jhep.1997.v25.pm0009021948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Nieto N, Friedman SL, Cederbaum AI. Cytochrome P450 2E1-derived reactive oxygen species mediate paracrine stimulation of collagen I protein synthesis by hepatic stellate cells. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:9853–9864. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110506200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Bell LN, Temm CJ, Saxena R, Vuppalanchi R, Schauer P, Rabinovitz M, Krasinskas A, Chalasani N, Mattar SG. Bariatric surgery-induced weight loss reduces hepatic lipid peroxidation levels and affects hepatic cytochrome P-450 protein content. Ann Surg. 2010;251:1041–1048. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181dbb572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Bardag-Gorce F, Yuan QX, Li J, French BA, Fang C, Ingelman-Sundberg M, French SW. The effect of ethanol-induced cytochrome p4502E1 on the inhibition of proteasome activity by alcohol. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;279:23–29. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.3889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Butura A, Nilsson K, Morgan K, Morgan TR, French SW, Johansson I, Schuppe-Koistinen I, Ingelman-Sundberg M. The impact of CYP2E1 on the development of alcoholic liver disease as studied in a transgenic mouse model. J Hepatol. 2009;50:572–583. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2008.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]