Abstract

AIM: To assess the effects of 3-field lymphadenectomy for esophageal carcinoma.

METHODS: We conducted a computerized literature search of the PubMed, Cochrane Controlled Trials Register, and EMBASE databases from their inception to present. Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) or observational epidemiological studies (cohort studies) that compared the survival rates and/or postoperative complications between 2-field lymphadenectomy (2FL) and 3-field lymphadenectomy (3FL) for esophageal carcinoma with R0 resection were included. Meta-analysis was conducted using published data on 3FL vs 2FL in esophageal carcinoma patients. End points were 1-, 3-, and 5-year overall survival rates and postoperative complications, including recurrent nerve palsy, anastomosis leak, pulmonary complications, and chylothorax. Subgroup analysis was performed on the involvement of recurrent laryngeal lymph nodes.

RESULTS: Two RCTs and 18 observational studies with over 7000 patients were included. There was a clear benefit for 3FL in the 1- (RR = 1.16; 95%CI: 1.09-1.24; P < 0.01), 3- (RR = 1.44; 95%CI: 1.19-1.75; P < 0.01), and 5-year overall survival rates (RR = 1.37; 95%CI: 1.18-1.59; P < 0.01). For postoperative complications, 3FL was associated with significantly more recurrent nerve palsy (RR = 1.43; 95%CI: 1.28-1.60; P = 0.02) and anastomosis leak (RR = 1.26; 95%CI: 1.05-1.52; P = 0.09). In contrast, there was no significant difference for pulmonary complications (RR = 0.93; 95%CI: 0.75-1.16, random-effects model; P = 0.27) or chylothorax (RR = 0.77; 95%CI: 0.32-1.85; P = 0.69).

CONCLUSION: This meta-analysis shows that 3FL improves overall survival rate but has more complications. Because of the high heterogeneity among outcomes, definite conclusions are difficult to draw.

Keywords: Oesophagus, Cancer, Lymph node dissection, Survival, Complication

Core tip: Surgery for esophageal cancer includes removal of the primary lesion and lymph node dissection; however, there is a long-standing debate concerning the application of 3-field lymphadenectomy (3FL). The main purpose of the present meta-analysis was to present all available evidence in a systematic, quantitative, and unbiased fashion to establish the following 3 points: the effect of 3FL on the overall survival rate, identification of postoperative complications of 3FL compared to 2-field lymphadenectomy, and description of patient characteristics of those who will likely benefit from 3FL.

INTRODUCTION

Esophageal cancer is one of the most lethal malignancies and has a long-term overall survival (OS) rate of only approximately 25% in most Western series[1], while in some Japanese series, the 5-year OS rate was reported to be approximately 50%[2]. Extensive research has been conducted to improve treatment options, especially for the optimal extent of lymph node dissection. Since 1983, several Japanese institutions[3,4] have employed radical 3-field lymphadenectomy (3FL) of the bilateral cervical, mediastinal, and abdominal regions, with the theoretical justification that relapse of cervical lymph node occurs frequently[5,6].

After almost 30 years, however, 3FL is not widely applied because its advantages and disadvantages remain controversial, resulting in an increasing amount of research focusing on identifying optimal patients and clarifying indications for 3FL recently. Nevertheless, esophagectomy remains technically demanding, and few centers can recruit a sufficient number of patients to perform clinical trials that can withstand scrutiny.

The present meta-analysis aimed to investigate the following 3 primary points: (1) the effect of 3FL on the OS rate; (2) a comparison of postoperative complications between 2FL and 3FL, and (3) identification of optimal patients who will most likely benefit from 3FL. To comprehensively and credibly answer these queries, we conducted a detailed meta-analysis using data from currently available studies that compared 3FL with 2FL, including 2 randomized controlled trials (RCTs)[7,8] and 18 observational studies[9-26]. The meta-analysis was performed on data from 1-, 3-, and 5-year OS rates, complications (recurrent nerve palsy, anastomosis leak, chylothorax, and pulmonary complications), and subgroups of recurrent laryngeal lymph node involvement. The article was arranged using a guide for reporting meta-analysis of observational studies[27].

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ethics

This work has been carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (2000) of the World Medical Association. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center.

Search strategy

To identify relevant studies, we conducted a computerized literature search of the PubMed, Cochrane Controlled Trials Register, and EMBASE databases from their inception to present. The search terms included the following: (1) “three-field”, “3-field”, “three field”, “3 field”, “extended cervical”, “cervical lymph node dissection”, “cervical lymphadenectomy”, “neck lymph node dissection”, “neck lymphadenectomy”, “3-F”, “3F”, and “3FL”; (2) esophageal neoplasms (MeSH); and (3) a combination of (1) and (2).

The titles and abstracts of the identified studies were scanned to exclude any study that was clearly irrelevant. The full texts of the remaining articles were read to determine whether they contained information on the topic of interest. The reference lists of articles with relevant information were reviewed to identify citations to other studies on the same topic.

Selection criteria

The reports considered in this meta-analysis were either RCTs or observational epidemiological studies (cohort studies) that compared the survival rates and/or postoperative complications between 2FL and 3FL for esophageal carcinoma with R0 resection. There was no restriction regarding the language of articles. Articles were excluded from the analyses if they (1) contained insufficient published data for determining an estimate of relative risk (RR) or confidence interval (CI); (2) included special restrictions to types and/or stages of esophageal carcinoma (restriction to squamous carcinoma was not included because almost all tumors are of this type); (3) randomly applied 2FL or 3FL to the included patients; (4) did not apply curative resection to all included patients; and/or (5) were of poor quality and led to large biases in the analysis. In addition, for studies with multiple publications from the same population, only one with the largest data set was included. We did not assess the methodological quality of the primary studies because quality assessment in meta-analysis is controversial. Scores constructed in an ad-hoc fashion may lack demonstrated validity, and results may not be associated with quality[28].

Information extraction

Two reviewers independently extracted data using predefined criteria from each study, including the following: (1) Basic information comprising the first author’s last name, year of publication, journal name, study region, study design, type and stage of esophageal tumor, and inclusion and/or exclusion criteria; (2) Published data, including the 1-, 3-, and 5-year OS rates (collected by 2 methods provided by the author or measurement of the Kaplan-Meier survival curve with the software Engauge.exe), study population, operation time, complications, and subgroup data.

When more than one estimate of effect (RR) was presented in observational studies, the most adjusted estimate was chosen. Differences in data extraction were resolved by consensus and reference to the original articles.

Statistical analysis

We performed 3 comparisons between 3FL and 2FL for esophageal carcinoma-the OS rate, complications, and subgroups. For OS, 1-, 3-, and 5-year rates were compared; for complications, recurrent nerve palsy, anastomosis leak, pulmonary complications, and chylothorax were included; and for subgroup analysis, studies with recurrent laryngeal lymph node positivity/negativity were included.

Data from each study were analyzed using Review Manager software (RevMan version 5.0; http://ims.cochrane.org/revman/download). Treatment effects were expressed as RRs with 95%CIs for dichotomous outcomes. Because mortality or morbidity was not a small probability event in the participants, the Mantel-Haenszel analysis method was used[29].

We separately pooled RR estimates from each study for each outcome using random-effects meta-analysis. Statistical heterogeneity of the RRs was evaluated using the χ2-test with significance set at P < 0.01, and the I2 statistic was calculated; publication bias was assessed using funnel plots. Low, moderate, and high degrees of heterogeneity correspond to I2 values of 25%, 50%, and 75%, respectively. Sensitivity analyses were used to evaluate whether the results could have been markedly affected by a single study.

RESULTS

Search results

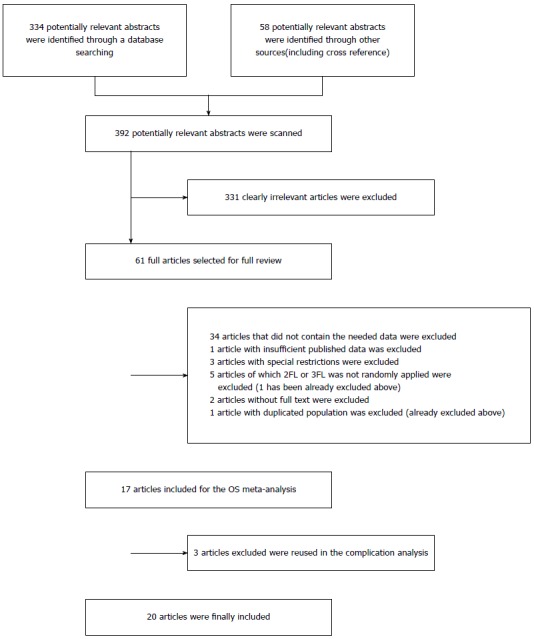

The references (n = 334) were retrieved by the original search strategy or by manual searches (n = 58). The abstracts were reviewed, and 61 articles were selected for full-text evaluation. After applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 20 articles were finally included (Table 1). The flow chart of the study inclusion process is shown in Figure 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the studies include in the meta-analysis

| Study | Year | Journal | Study design | Region | Study population, n | Operation time |

| Li et al[10] | 2012 | J Surg Oncol | Obser. | China | 3FL: 136; 2FL: 227 | 2003-2010 |

| Thakur et al[9] | 2011 | Indian J Cancer | Obser. | Nepal | 3FL: 61; 2FL: 21 | 2003-2011 |

| Shim et al[12] | 2010 | J Thorac Oncol | Obser. | South Korea | 3FL: 57; 2FL: 34 | 1994-2007 |

| Zhang et al[11] | 2008 | Zhonghua Zhongliu Zazhi | Obser. | China | 3FL: 60; 2FL: 62 | 2001-2006 |

| Igaki et al[13] | 2004 | Ann Surg | Obser. | Japan | 3FL: 101; 2FL: 55 | 1988-1997 |

| Noguchi et al[14] | 2004 | Dis Esophagus | Obser. | Japan | 3FL: 68; 2FL: 78 | 1990-2001 |

| Hagry et al[15] | 2003 | Eur J Cardiothorac Surg | Obser. | Belgium | 3FL: 34; 2FL: 38 | 1975-2001 |

| Gradauskas et al[16] | 2002 | Medicina (Kaunas) | Obser. | Lithuania | 3FL: 23; 2FL: 19 | 1997-2002 |

| Shiozaki et al[17] | 2001 | Dis Esophaguss | Obser. | Japan | 3FL: 129; 2FL: 123 | 1985-1998 |

| Tabira et al[18] | 1999 | J Cardiovasc Surg | Obser. | Japan | 3FL: 66; 2FL: 86 | 1983-1996 |

| Kawahara et al[19] | 1998 | J Surg Oncol | Obser. | Japan | 3FL: 44; 2FL: 44 | 1974-1995 |

| Nishihira et al[7] | 1998 | Am J Surg | RCT. | Japan | 3FL: 32; 2FL: 30 | 1987-1994 |

| Fujita et al[20] | 1995 | Ann Surg | Obser. | Japan | 3FL: 63; 2FL: 65 | 1986-1991 |

| Kakegawa et al[21] | 1995 | Gan To Kagaku Ryoho | Obser. | Japan | 3FL: 124; 2FL: 107 | 1985-1994 |

| Kato et al[22] | 1995 | Ann Chir Gynaecol | Obser. | Japan | 3FL: 100; 2FL: 410 | 1962-1993 |

| Akiyama et al[23] | 1994 | Ann Surg | Obser. | Japan | 3FL: 324; 2FL: 393 | 1973-1993 |

| Fujita et al[24] | 1992 | Kurume Med J | Obser. | Japan | 3FL: 27; 2FL: 100 | 1982-1988 |

| Isono et al[25] | 1991 | Oncology | Obser. | Japan | 3FL: 1740; 2FL: 2671 | 1983-1989 |

| Kato et al[8] | 1991 | Ann Thorac Surg | RCT | Japan | 3FL: 77; 2FL: 73 | 1985-1989 |

| Ando et al[26] | 1989 | Nihon Geka Gakkai Zasshi | Obser. | Japan | 3FL: 22; 2FL: 56 | 1984-1988 |

Obser: Observational studies; 3FL: 3-field lymphadenectomy; 2FL: 2-field lymphadenectomy.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the search strategy and study selection.

Meta-analysis of studies on the OS rates

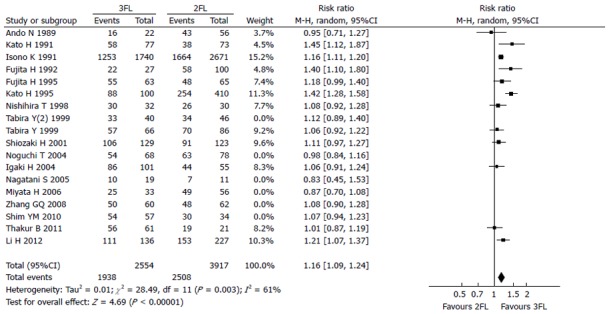

Twelve studies were used for 1-year OS rate analysis, including 2554 3FL patients and 3917 2FL patients. Only 5 studies reported a statistically significant difference between 2FL and 3FL, with a better OS rate in the 3FL group. Among studies with no statistical significance, 6 reported a higher 1-year OS rate in the 3FL group, whereas 1 reported a lower rate, which raised concerns regarding the significance of 3FL. Meta-analysis of all 12 studies showed a statistically significant difference between 3FL and 2FL, with a pooled RR of 1.16 (95%CI: 1.09-1.24; P < 0.00001; random-effects model) and statistical heterogeneity (P = 0.0003; I2 = 61%). 3FL showed a significant improvement in the 1-year OS rate.

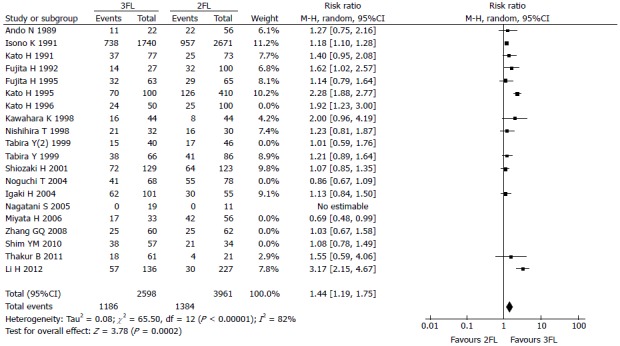

The 3-year OS rate presented in 13 studies included 2598 3FL patients and 3961 2FL patients. Four studies reported a statistically significant difference with a better OS rate in the 3FL group. Studies with no statistical significance reported a higher 3-year OS rate. Meta-analysis of all 13 studies showed statistically significant differences between 3FL and 2FL with a pooled RR of 1.44 (95%CI: 1.19-1.75, P < 0.00001, random-effects model) and statistical heterogeneity (P < 0.00001; I2 = 82%). 3FL showed a significantly higher 3-year OS rate.

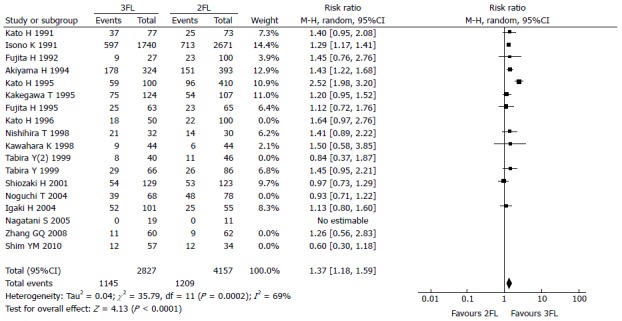

The 5-year OS rate reported in 12 studies included 2827 3FL patients and 4157 2FL patients. Only 3 studies reported a statistically significant difference with a better OS rate in the 3FL group. Among the 9 studies with no statistical significance, 8 reported a higher 5-year OS rate in the 3FL group, while 1 reported a lower rate. Meta-analysis of all 12 studies showed a statistically significant difference between 3FL and 2FL with a pooled RR of 1.37 (95%CI: 1.18-1.59; P = 0.0002; random-effects model) and statistical heterogeneity (P < 0.00001; I2 = 69%). 3FL showed a significant improvement in the 3-year OS rate. The forests plots are shown in Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4.

Figure 2.

Forest plot of the 1-year overall survival rate. 3FL: 3-field lymphadenectomy; 2FL: 2-field lymphadenectomy.

Figure 3.

Forest plot of the 3-year overall survival rate. 3FL: 3-field lymphadenectomy; 2FL: 2-field lymphadenectomy.

Figure 4.

Forest plot of the 5-year overall survival rate. 3FL: 3-field lymphadenectomy; 2FL: 2-field lymphadenectomy.

Meta-analysis of studies on postoperative complications

After reviewing the postoperative complications, we included the 4 most common complications for analysis; these complications included recurrent nerve palsy, anastomosis leak, chylothorax, and pulmonary complications. The meta-analysis results from all studies demonstrated that 3FL was associated with more complications than 2FL with respect to anastomosis leakage and recurrent nerve palsy (Table 2). Chylothorax and pulmonary complications were not statistically significantly different between 3FL and 2FL.

Table 2.

Results of meta-analysis of studies for postoperative complications

| Complications | Studies |

Participants |

Fixed-effects model |

Random-effects model |

Tests of homogeneity |

||||||

| 3FL | 2FL | RR | 95%CI | RR | 95%CI | Q | df | P | I2 (%) | ||

| Recurrent nerve palsy | 10 | 2320 | 3534 | 1.43 | 1.28 to 1.60 | 1.48 | 1.13-1.92 | 19.05 | 9 | 0.02 | 53 |

| Anastomosis leak | 10 | 608 | 926 | 1.26 | 1.05 to 1.52 | 1.32 | 0.97-1.81 | 14.53 | 9 | 0.09 | 38 |

| Pulmonary complications | 12 | 2370 | 3653 | 0.88 | 0.80 to 0.98 | 0.93 | 0.75-1.16 | 13.38 | 11 | 0.27 | 18 |

| Chylothorax | 6 | 458 | 699 | 0.77 | 0.32 to 1.85 | 0.87 | 0.33-2.26 | 3.05 | 5 | 0.69 | 0 |

3FL: 3-field lymphadenectomy; 2FL: 2-field lymphadenectomy.

Meta-analysis of studies on subgroups

There were insufficient data available for subgroup analysis; therefore, only data pertaining to recurrent laryngeal lymph node positivity/negativity were integrated for meta-analysis. Three studies were included in the positive group[10,17,18], including 107 3FL patients and 92 2FL patients. Meta-analysis of these 3 studies showed statistically significant differences between 3FL and 2FL because the OS rate in the 3FL group was superior with a pooled 1-year RR of 1.29 (95%CI: 1.08-1.53; P = 0.004; fixed-effects model) and statistical heterogeneity (P = 0.80, I2 = 0%), and a 3-year RR of 6.80 (95%CI: 2.99-15.46; P < 0.00001; fixed-effects model) and statistical heterogeneity (P = 0.98; I2 = 0%). For the negative group, 2 studies were analyzed[10,17], including 176 3FL patients and 271 2FL patients. Meta-analysis of the 2 studies showed statistically significant differences between 3FL and 2FL with a better OS rate in the 3FL group, a pooled 1-year RR of 1.14 (95%CI: 1.03-1.27; P = 0.01, fixed-effects model) with statistical heterogeneity (P = 0.86, I2 = 0%), and a 3-year RR of 1.92 (95%CI: 0.56-6.53; P = 0.30; random-effects model) with statistical heterogeneity (P = 0.003; I2 = 89%). For the other subgroups: (1) carcinoma in the upper or middle third esophagus had a survival advantage with 3FL[20,23,30]; (2) early superficial carcinoma confined to the mucosa had an equal OS rate between 3FL and 2FL[31]; and (3) poor prognostic subgroups had metastatic nodes in all 3 fields and the lower-third of tumors had positive cervical nodes with the involvement of ≥ 5 lymph nodes. The subgroups had equal OS rates between 3FL and 2FL[32].

DISCUSSION

Surgery for esophageal cancer includes removal of the primary lesion and lymph node dissection; however, there is a long-standing debate concerning application of 3FL, which was initiated at Chiba University (Chiba-shi, Japan) in 1983[25]. This method was based on the observation that the relapse rates at the cervical nodes were 30%-40%, which presented a significant obstacle in the improvement of surgical results[5,6]. After 1983, 3FL was widely employed in Japan, but not worldwide until recently because of lack of evidence. As mentioned above, esophagectomy is technically demanding, and few centers can recruit a sufficient number of patients to perform randomized clinical trials that can withstand scrutiny; thus, only 2 randomized trials to date have been published that compared 3FL with 2FL. One trial showed a survival advantage for 3FL; however, patients treated with 2FL were older and had more proximal tumors[8]. In the second trial, the 5-year OS rates were not statistically different between 3FL and 2FL (66.2% and 48%, respectively)[7]. These limited randomized trials were, however, insufficient to conclude that 3FL was advantageous. As there are many observational studies comparing 3FL and 2FL, we performed the present meta-analysis to synthesize data to yield more comprehensive and credible results.

Meta-analysis serves as a valuable tool for studying rare and unintended treatment effects and extends prior randomized and nonrandomized studies by permitting synthesis of data and providing more stable estimates of effects. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first meta-analysis of published studies to compare 3FL and 2FL for esophageal cancer and provide evidence for the comparison of OS, postoperative complications, and subgroups.

This meta-analysis brings together all currently available data from randomized trials and observational studies comparing 2FL and 3FL in esophageal carcinoma patients, thereby providing reliable assessment of the role of 3FL. Through this meta-analysis, we discussed the 3 queries mentioned above. First, regarding the effect of 3FL on the OS rate, the present study revealed that 3FL had a significant improvement in the 1-, 3-, and 5-year OS rates (RR = 1.16, 1.44, and 1.37, respectively). However, we questioned the credibility of the 3 aspects of these results. The first was the high degree heterogeneity of all the 3 outcomes. For meta-analysis of mostly observational studies, when outcome heterogeneity is particularly problematic, a single summary measure is likely inappropriate. Thus, evaluating heterogeneity becomes a key issue. Although we did our best to exclude articles that did not meet the selection criteria, the heterogeneity may be because of the following factors: (1) different types, stages, and locations of esophageal carcinoma in each observational study; (2) different patient ethnicities with different genotypes and proportion of tumor types; and (3) different institutions, surgeons with unequal skills, and different operative durations. However, the amount of information was not sufficient for stratifying or regression analysis. The second aspect was derived from theoretical justification. Although we could not perform 3FL analysis because of frequent recurrence in the cervical lymph nodes, 2 studies on recurrence patterns after esophagectomy reported recurrence rates of 7% and 1%, which were both significantly lower than the 30% incidence rate expected from cervical metastases[33,34]. Finally, on the basis of the funnel plot results, we concluded that publication bias occurred in all the 3 outcomes.

The second part of this analysis compared postoperative complications between 2FL and 3FL. Our results determined that 3FL had more complications than 2FL in anastomosis leak and recurrent nerve palsy, while the incidences of chylothorax and pulmonary complications were not significantly different. Heterogeneity was not high because less mixed factors may have affected the result. The result was much less controversial and presents an obvious disadvantage of 3FL.

Treatment complications are often detrimental. For example, recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy due to extensive dissection of the recurrent laryngeal nerve chain remains the main concern and can affect up to 70% of cases[20]. Recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy impedes not only immediate postoperative recovery but also long-term quality of life in terms of speech, swallowing, and respiratory functions.

For the last query, we identified patients who would likely benefit from 3FL. As previously mentioned, much current research has focused on identifying optimal patients through subgroup analysis. An important study that evaluated recurrent nerve nodal involvement in 86 3FL patients identified a relationship between thoracic recurrent nerve nodal involvement and cervical metastases. Only 11% of the 63 patients without thoracic recurrent nodal involvement had positive cervical nodes, in contrast to 43% of the 23 patients with recurrent thoracic nodal disease and positive cervical nodes. A “sentinel node” concept was proposed to guide the addition of cervical lymphadenectomy[35]. However, from our results, we could not conclude that 3FL benefited only positive, but not negative, cervical nodes based on the available data. As to the other subgroups, limited data were derived from published studies; thus, they were insufficient to draw definite conclusions.

The main purpose of the present meta-analysis was to present all available evidence in a systematic, quantitative, and unbiased fashion to establish the following 3 points: the effect of 3FL on the OS rate, identification of postoperative complications of 3FL compared to 2FL, and description of patient characteristics of those who will likely benefit from 3FL. However, because of limitations of the available data, only the second query was clearly answered. For the first query, we could only determine that 3FL had better 1-, 3-, and 5-year OS rates compared to 2FL, when all currently available data were integrated. However, the credibility of the results remains controversial. Clinicians can make treatment decisions based on this evidence and consultations with patients on their perceived treatment outcomes.

COMMENTS

Background

Debate about the application of 3-field lymphadenectomy (3FL) for esophageal cancer has been heated for a long time, because the advantages and disadvantages still remain controversial when compared to the traditional 2-field lymphadenectomy (2FL).

Research frontiers

Over the decades, many observational studies comparing 3FL and 2FL have been performed to figure out whether 3FL was advantageous. Moreover, a few randomized trials were recently performed to investigate it. However, those are insufficient to reach a precise conclusion.

Innovations and breakthroughs

This is a meta-analysis of published studies to compare 3FL and 2FL for esophageal cancer and provide evidence for the comparison of overall survival, postoperative complications, and subgroups. Based on this meta-analysis, 3FL had better 1-, 3-, and 5-year overall survival rates compared to 2FL while 3FL had more complications than 2FL in anastomosis leak and recurrent nerve palsy.

Applications

3FL has better overall survival rates but more complications. Clinicians can make treatment decisions based on this evidence and consultations with patients on their acceptable treatment outcomes.

Terminology

3FL is dissecting lymph node of the bilateral cervical, mediastinal, and abdominal regions, with the theoretical justification that relapse of cervical lymph node occur frequently.

Peer review

The authors present a meta-analysis using published data on 3FL vs 2FL in esophageal carcinoma patients. End points of this meta-analysis were 1-, 3-, and 5-year overall survival rates and postoperative complications. This is an important clinical question and the results of this analysis will likely have an impact on clinical decisions in the future. The meta-analysis was conducted properly, objectively and the results are valid and significant. The conclusions of the manuscript are accurate, and supported by the data.

Footnotes

Supported by Grants from the Science and Technology Planning Project of Guangdong Province, China, No. 2010B31500010, No. 2012B031800463 and No. 2013B022000040; and the National High Technology Research and Development Program of China (863 Program), No. 2009AA02Z421

P- Reviewer: Amornyotin S, Dovat S, Shao R S- Editor: Yu J L- Editor: Wang TQ E- Editor: Liu XM

References

- 1.Daly JM, Fry WA, Little AG, Winchester DP, McKee RF, Stewart AK, Fremgen AM. Esophageal cancer: results of an American College of Surgeons Patient Care Evaluation Study. J Am Coll Surg. 2000;190:562–572; discussion 572-573. doi: 10.1016/s1072-7515(00)00238-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nakagawa S, Kanda T, Kosugi S, Ohashi M, Suzuki T, Hatakeyama K. Recurrence pattern of squamous cell carcinoma of the thoracic esophagus after extended radical esophagectomy with three-field lymphadenectomy. J Am Coll Surg. 2004;198:205–211. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2003.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Isono K, Ochiai T, Okuyama K, Onoda S. The treatment of lymph node metastasis from esophageal cancer by extensive lymphadenectomy. Jpn J Surg. 1990;20:151–157. doi: 10.1007/BF02470762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sannohe Y, Hiratsuka R, Doki K. Lymph node metastases in cancer of the thoracic esophagus. Am J Surg. 1981;141:216–218. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(81)90160-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Isono K, Onoda S, Okuyama K, Sato H. Recurrence of intrathoracic esophageal cancer. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 1985;15:49–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Isono K, Onoda S, Ishikawa T, Sato H, Nakayama K. Studies on the causes of deaths from esophageal carcinoma. Cancer. 1982;49:2173–2179. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19820515)49:10<2173::aid-cncr2820491032>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nishihira T, Hirayama K, Mori S. A prospective randomized trial of extended cervical and superior mediastinal lymphadenectomy for carcinoma of the thoracic esophagus. Am J Surg. 1998;175:47–51. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(97)00227-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kato H, Watanabe H, Tachimori Y, Iizuka T. Evaluation of neck lymph node dissection for thoracic esophageal carcinoma. Ann Thorac Surg. 1991;51:931–935. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(91)91008-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thakur B, Zhang CS, Meng XL, Bhaktaman S, Bhurtel S, Khakural P. Eight-year experience in esophageal cancer surgery. Indian J Cancer. 2011;48:34–39. doi: 10.4103/0019-509X.75821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li H, Yang S, Zhang Y, Xiang J, Chen H. Thoracic recurrent laryngeal lymph node metastases predict cervical node metastases and benefit from three-field dissection in selected patients with thoracic esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. J Surg Oncol. 2012;105:548–552. doi: 10.1002/jso.22148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang GQ, Han F, Sun W, Pang ZL, SiKanDaer AB, Wang HJ. [Impact of different extents of lymph node dissection on the survival in stage III esophageal cancer patients] Zhonghua Zhongliu Zazhi. 2008;30:858–862. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shim YM, Kim HK, Kim K. Comparison of survival and recurrence pattern between two-field and three-field lymph node dissections for upper thoracic esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. J Thorac Oncol. 2010;5:707–712. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181d3ccb2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Igaki H, Tachimori Y, Kato H. Improved survival for patients with upper and/or middle mediastinal lymph node metastasis of squamous cell carcinoma of the lower thoracic esophagus treated with 3-field dissection. Ann Surg. 2004;239:483–490. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000118562.97742.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Noguchi T, Wada S, Takeno S, Hashimoto T, Moriyama H, Uchida Y. Two-step three-field lymph node dissection is beneficial for thoracic esophageal carcinoma. Dis Esophagus. 2004;17:27–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2004.00353.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hagry O, Coosemans W, De Leyn P, Nafteux P, Van Raemdonck D, Van Cutsem E, Hausterman K, Lerut T. Effects of preoperative chemoradiotherapy on postsurgical morbidity and mortality in cT3-4 +/- cM1lymph cancer of the oesophagus and gastro-oesophageal junction. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2003;24:179–186; discussion 186. doi: 10.1016/s1010-7940(03)00274-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gradauskas P, Rubikas R, Petrauskas V. [Early results of esophageal resections, performed due to carcinoma] Medicina (Kaunas) 2002;38 Suppl 2:61–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shiozaki H, Yano M, Tsujinaka T, Inoue M, Tamura S, Doki Y, Yasuda T, Fujiwara Y, Monden M. Lymph node metastasis along the recurrent nerve chain is an indication for cervical lymph node dissection in thoracic esophageal cancer. Dis Esophagus. 2001;14:191–196. doi: 10.1046/j.1442-2050.2001.00206.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tabira Y, Kitamura N, Yoshioka M, Tanaka M, Nakano K, Toyota N, Mori T. Significance of three-field lymphadenectomy for carcinoma of the thoracic esophagus based on depth of tumor infiltration, lymph nodal involvement and survival rate. J Cardiovasc Surg (Torino) 1999;40:737–740. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kawahara K, Maekawa T, Okabayashi K, Shiraishi T, Yoshinaga Y, Yoneda S, Hideshima T, Shirakusa T. The number of lymph node metastases influences survival in esophageal cancer. J Surg Oncol. 1998;67:160–163. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9098(199803)67:3<160::aid-jso3>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fujita H, Kakegawa T, Yamana H, Shima I, Toh Y, Tomita Y, Fujii T, Yamasaki K, Higaki K, Noake T. Mortality and morbidity rates, postoperative course, quality of life, and prognosis after extended radical lymphadenectomy for esophageal cancer. Comparison of three-field lymphadenectomy with two-field lymphadenectomy. Ann Surg. 1995;222:654–662. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199511000-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kakegawa T, Yamana H. [Progress in surgical treatment of carcinoma of the intrathoracic esophagus] Gan To Kagaku Ryoho. 1995;22:855–862. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kato H. Lymph node dissection for thoracic esophageal carcinoma. Two- and 3-field lymph node dissection. Ann Chir Gynaecol. 1995;84:193–199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Akiyama H, Tsurumaru M, Udagawa H, Kajiyama Y. Radical lymph node dissection for cancer of the thoracic esophagus. Ann Surg. 1994;220:364–372; discussion 372-373. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199409000-00012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fujita H, Kakegawa T, Yamana H, Shima I, Rikitake H, Hyodo M, Yokoyama T, Fujii T, Toh U, Tsugane S. Cervico-thoraco-abdominal (3-field) lymph node dissection for carcinoma in the thoracic esophagus. Kurume Med J. 1992;39:167–174. doi: 10.2739/kurumemedj.39.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Isono K, Sato H, Nakayama K. Results of a nationwide study on the three-field lymph node dissection of esophageal cancer. Oncology. 1991;48:411–420. doi: 10.1159/000226971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ando N, Shinozawa Y, Kikunaga H, Koyama Y, Nagashima A, Osaku M, Abe O. [An assessment of extended lymphadenectomy including cervical node dissection for cancer of the thoracic esophagus] Nihon Geka Gakkai Zasshi. 1989;90:1616–1618. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, Olkin I, Williamson GD, Rennie D, Moher D, Becker BJ, Sipe TA, Thacker SB. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA. 2000;283:2008–2012. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.15.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jüni P, Witschi A, Bloch R, Egger M. The hazards of scoring the quality of clinical trials for meta-analysis. JAMA. 1999;282:1054–1060. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.11.1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mantel N, Haenszel W. Statistical aspects of the analysis of data from retrospective studies of disease. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1959;22:719–748. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Löhlein D. [Esophageal carcinoma: surgical treatment concepts; access and resectability] Schweiz Med Wochenschr. 1999;129:1211–1216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nishimaki T, Tanaka O, Suzuki T, Aizawa K, Watanabe H, Muto T. Tumor spread in superficial esophageal cancer: histopathologic basis for rational surgical treatment. World J Surg. 1993;17:766–771; discussion 771-772. doi: 10.1007/BF01659091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nishimaki T, Suzuki T, Suzuki S, Kuwabara S, Hatakeyama K. Outcomes of extended radical esophagectomy for thoracic esophageal cancer. J Am Coll Surg. 1998;186:306–312. doi: 10.1016/s1072-7515(98)00013-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Law SY, Fok M, Wong J. Pattern of recurrence after oesophageal resection for cancer: clinical implications. Br J Surg. 1996;83:107–111. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800830134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dresner SM, Wayman J, Shenfine J, Harris A, Hayes N, Griffin SM. Pattern of recurrence following subtotal oesophagectomy with two field lymphadenectomy. Br J Surg. 2000;87:362–373. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.2000.01383-5.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tabira Y, Yasunaga M, Tanaka M, Nakano K, Sakaguchi T, Nagamoto N, Ogi S, Kitamura N. Recurrent nerve nodal involvement is associated with cervical nodal metastasis in thoracic esophageal carcinoma. J Am Coll Surg. 2000;191:232–237. doi: 10.1016/s1072-7515(00)00348-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]