Abstract

AIM: To provide a comprehensive evaluation of the role of a protective stoma in low anterior resection (LAR) for rectal cancer.

METHODS: The PubMed, EMBASE, and MEDLINE databases were searched for studies and relevant literature published between 2007 and 2014 regarding the construction of a protective stoma during LAR. A pooled risk ratio (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) was used to assess the outcomes of the studies, including the rate of postoperative anastomotic leakage and reoperations related to leakage. Funnel plots and Egger’s tests were used to evaluate the publication biases of the studies. P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS: A total of 11 studies were included in the meta-analysis. In total, 5612 patients were examined, 2868 of whom had a protective stoma and 2744 of whom did not. The sample size of the studies varied from 34 to 1912 patients. All studies reported the number of patients who developed an anastomotic leakage and required a reoperation related to leakage. A random effects model was used to calculate the pooled RR with the corresponding 95%CI because obvious heterogeneity was observed among the 11 studies (I2 = 77%). The results indicated that the creation of a protective stoma during LAR significantly reduces the rate of anastomotic leakage and the number of reoperations related to leakage, with pooled RRs of 0.38 (95%CI: 0.30-0.48, P < 0.00001) and 0.37 (95%CI: 0.29-0.48, P < 0.00001), respectively. The shape of the funnel plot did not reveal any evidence of obvious asymmetry.

CONCLUSION: The presence of a protective stoma effectively decreased the incidences of anastomotic leakage and reoperation and is recommended in patients undergoing low rectal anterior resections for rectal cancer.

Keywords: Protective stoma, Low anterior resection, Rectal cancer, Complication, Meta-analysis

Core tip: The use of a protective stoma is an effective application that can reduce the rate of anastomotic leakage in patients who receive low anterior resection for rectal cancer. The morbidity associated with protective stomas and the complications of stoma closure are negligible compared with the reoperations required for anastomosis leakage in the absence of a protective stoma. Therefore, the presence of a non-functioning stoma can be useful for patients undergoing rectal surgery and is recommended during low anterior resections for rectal cancer.

INTRODUCTION

Low anterior resection (LAR) is the standard operation for rectal cancer and allows an anastomosis to be created at a lower level, thereby preserving the anal sphincter[1]. Nonetheless, anastomotic leakage remains one the most significant complications after LAR. Anastomotic leakage is defined as a communication between the intra- and extraluminal compartments owing to a defect in the integrity of the intestinal wall at the anastomosis between the colon and rectum or the colon and anus[2]. In the last decade, the problem of anastomotic leakage has been widely addressed in multiple symposia and many publications[3]. Leakage rates from 3% to > 20% leading to substantial postoperative morbidity and mortality have been reported[4,5]. Even experienced surgeons sometimes find it difficult to predict which patients will develop an anastomotic leak, and such leaks may occur even when the anastomosis is technically sound or when the risk factors for leakage are absent. Studies have demonstrated that such low anastomoses carry a considerably higher risk of anastomotic leakage[6]. Leakage can increase morbidity and mortality, prolong the duration of the hospital stay, and affect short- or long-term quality of life[7,8]. There is also evidence for an increased risk of local cancer recurrence and decreased long-term survival after leakage[9-11].

Many solutions have been sought to prevent or diminish anastomotic leakage, such as mechanical bowel preparation, drains, and intra-luminal devices. Some surgeons use a protective stoma after LAR to prevent anastomotic leakage in the hope that by diverting the fecal stream and keeping the anastomosis free of material, leakage will be less likely. While other surgeons have reported that covering the protective stoma had no influence on anastomotic leakage and reoperation rates, the further complications that can be caused by the stoma itself should not be ignored, as they include discomfort and inconvenience, high output with consequent dehydration, and anastomotic complications at the stoma closure site[12-18].

Although protective stomas are widely used in LAR for rectal cancer, it remains unclear whether such protective stomas are useful for patients. Therefore, we performed this meta-analysis to investigate whether a protective stoma affects the outcomes of patients undergoing LAR for rectal cancer.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Publication search

The PubMed, EMBASE, and MEDLINE databases and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials were searched to locate articles (published between January 2007 and January 2014), including articles referenced in the publications. The search strategy included the following keywords in various combinations: “low anterior resection”, “stoma”, “protective stoma”, “rectal cancer”, and “anastomotic leakage”. Internet search engines were also used to perform a manual search for abstracts from international meetings, which were then downloaded and studied.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria were as follows: studies that compared LAR with or without a protective stoma and recent clinical trials from 2007 to 2014. When a study reporting the same patient cohort was included in several publications, only the most recent or most complete study was selected. The exclusion criteria were as follows: studies of case reports, letters, or reviews without original data; non-English papers; animal or laboratory studies; non-rectal cancer proctectomy; and articles that were not full-text or non-comparative studies. If any doubt of suitability remained after the abstract was examined, the full manuscript was obtained[19].

Data extraction

Two review authors assessed the methodological quality of the potentially eligible studies without considering the results. The extracted data were then crosschecked between the two authors to rule out any discrepancies. Data were extracted independently from each of the included studies regarding the following: first authors’ surname, publication year, sample size, number of patients who developed an anastomotic leak and required a reoperation related to leakage after LAR, and whether a protective stoma was involved. Disagreements were discussed by the authors and resolved by consensus.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the Review Manager (RevMan) software, version 5.0 (The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, Copenhagen, Denmark). A pooled risk ratio (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) was used to assess the outcomes of the studies. I2 statistics were used to evaluate the between-study heterogeneity analysis in this meta-analysis[20]. The random effects model was used when obvious heterogeneity was observed among the included studies (I2 > 50%). The fixed effects model was used when there was no significant heterogeneity between the included studies (I2 ≤ 50%). Publication bias was estimated using a funnel plot with an Egger’s linear regression test; funnel plot asymmetry on the natural logarithm scale of the RR was measured using a linear regression approach.

RESULTS

Study characteristics

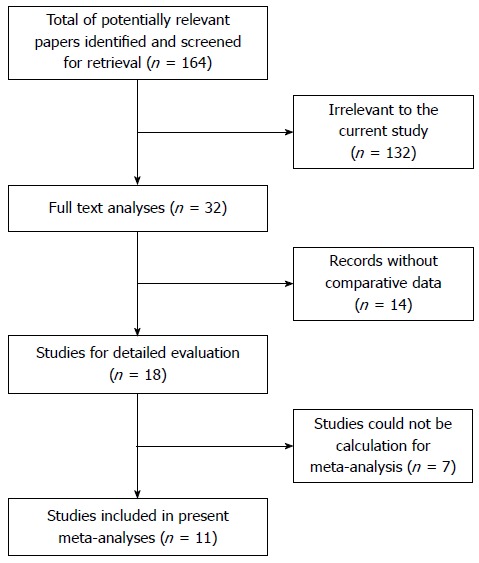

The initial search retrieved a total of 164 references, and after screening the titles and abstracts of the identified articles, 132 studies were excluded because they were not related to the current study. Of these studies, 56 were reviews, 35 were case reports, 11 were animal studies, and 20 included cases of non-rectal cancer proctectomy. Upon further review, 14 additional studies were excluded because they did not include comparative data. We evaluated 18 potential candidate studies in the full text, 7 of which were not published in English. Finally, 11 studies[21-31] were included in this meta-analysis, all of which were published between 2007 and 2014. The flow chart of study selection is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of study selection.

There were three RCTs and eight non-randomized studies involving a total population of 5612 patients, among whom 2868 had a protective stoma and 2744 did not. The sample sizes of the studies varied from 34 to 1912 patients. All studies reported the number of patients who developed an anastomotic leak and required a reoperation after LAR. Moreover, some studies reported the risk factors for anastomotic leakage and short-term mortality following LAR, although these data were not compared in this meta-analysis. The main characteristics of the included studies are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Main characteristics of the five included studies

| Ref. | Year | No. of patients |

n |

Type of operation |

Leakage |

Reoperation |

|||

| Stoma | No stoma | Stoma | No stoma | Stoma | No stoma | ||||

| Beirens et al[21] | 2012 | 1912 | 1183 | 729 | LAR | 51 | 74 | 40 | 69 |

| Chude et al[22] | 2008 | 256 | 136 | 120 | LAR | 3 | 12 | 0 | 2 |

| Gong et al[23] | 2012 | 62 | 36 | 26 | uLAR | 0 | 5 | 0 | 2 |

| Karahasanoglu et al[24] | 2011 | 77 | 23 | 54 | LAR | 0 | 3 | - | - |

| Lefebure et al[25] | 2008 | 132 | 42 | 90 | LAR | 3 | 10 | 1 | 5 |

| Ma et al[26] | 2013 | 56 | 30 | 26 | LAR | 2 | 7 | 0 | 5 |

| Matthiessen et al[27] | 2007 | 234 | 116 | 118 | LAR | 12 | 33 | 12 | 32 |

| Nurkin et al[28] | 2013 | 1791 | 958 | 833 | LAR | 17 | 26 | 37 | 63 |

| Seo et al[29] | 2013 | 836 | 246 | 590 | uLAR | 1 | 22 | - | - |

| Shiomi et al[30] | 2010 | 222 | 80 | 142 | LAR | 3 | 17 | 0 | 14 |

| Ulrich et al[31] | 2009 | 34 | 18 | 16 | LAR | 1 | 6 | 0 | 6 |

LAR: Low anterior resection; uLAR: Ulter-low anterior resection.

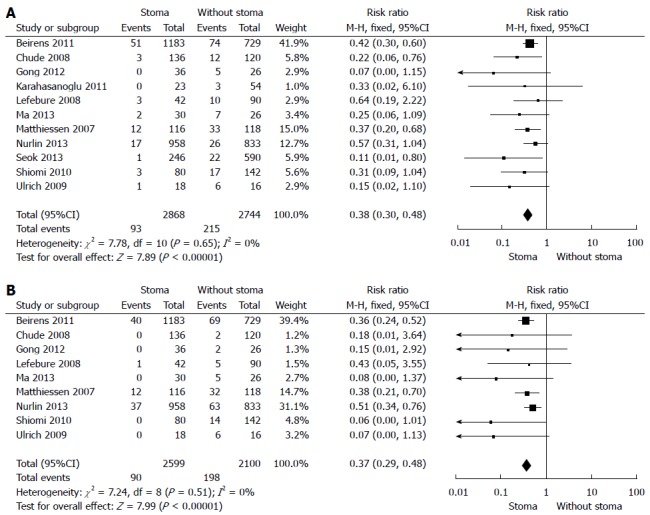

Meta-analysis results

All of the studies reported results on clinical anastomotic leakage and reoperation. The random effects model was used to calculate the pooled RR with the corresponding 95%CI because obvious heterogeneity was observed among those 11 studies (I2 = 77%). The results indicated that the absence of a protective stoma was associated with a higher incidence of anastomotic leakage and reoperation, with pooled RRs of 0.38 (95%CI: 0.30-0.48, P < 0.00001, Figure 2A) and 0.37 (95%CI: 0.29-0.48, P < 0.00001, Figure 2B), respectively. The present meta-analysis revealed that a statistically significant advantage was conferred by a protective stoma in patients undergoing LAR.

Figure 2.

Forest plot. A: Forest plot for a comparison of the study outcomes of low anterior resection with or without stoma vs anastomotic leakage; B: Forest plot of the study outcomes of low anterior resection with or without stoma vs reoperation rate. Risk ratios are shown with 95%CIs.

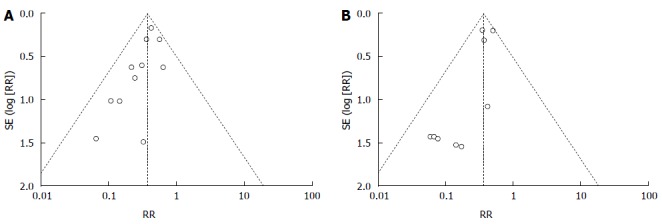

Publication bias

Funnel plots and Egger’s tests were used to evaluate the publication bias within the literature. The shape of the funnel plot did not reveal any evidence of obvious asymmetry (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Funnel plot. A: Funnel plot for the publication bias test of outcomes of low anterior resection with or without stoma vs anastomotic leakage; B: Funnel plot for the publication bias test regarding outcomes of low anterior resection with or without stoma vs reoperation rate. RR: Risk ratio.

DISCUSSION

Total mesorectal excision (TME) in combination with LAR plays an important role in the treatment of patients with rectal cancer[32]. Considering the incidence of rectal cancer, the improvements in medical instruments, and the higher requirements of patients regarding quality of their post-surgical lives, ultralow anterior rectal resection has become the primary low sphincter-preserving procedure. However, this procedure can also increase the risk of anastomotic leakage[33]. Possible factors contributing to an increased leakage rate include the reduced blood supply of the anorectal remnant and the large pelvic space after TME, which may predispose a patient to fluid accumulation and pelvic infection[34]. Symptomatic anastomotic leakage is the most feared complication and has been reported to occur in 1% to 24% of patients[35]; when present, the associated risk of postoperative mortality is increased to 6% to 22%[36].

The use of a non-functioning stoma in LAR has been considered to decrease the leakage rate and its fatal consequences by keeping the distal anastomosis relatively “clean” and reducing the intraluminal pressure of the bowel[33,37]. Moreover, a protective stoma can mitigate its inherent consequences[38]. Nonetheless, the value of a protective stoma has been the subject of controversy for many years. Some surgeons do not choose fecal diversion because fecal diversion requires the patient to undergo two surgeries and because a protective stoma does not reduce the leakage rate after LAR. Previous publications have reported that the overall leakage and reoperation rates were similar in patients with or without a protective stoma[39]. In addition, ostomy construction and closure is associated with considerable morbidity and increased costs[40]. The potential disadvantages of a protective stoma include the need for another operation, a longer hospital stay, and ostomy-related complications, such as prolapse, retraction, necrosis, stenosis, peristomal abscess, parastomal hernia, and skin problems. Therefore, the benefits of a protective stoma in decreasing the rate of anastomotic leakage must be balanced against the morbidity of its construction and closure. Furthermore, even when a non-functioning stoma is constructed, there remains a considerable risk of anastomotic leakage[41]. Thus, the benefits conferred by a protective stoma have not been unequivocally demonstrated. To further evaluate this argument, we completed the present meta-analysis including all of the relevant data available. The straightforward conclusion of the 11 included studies is that the creation of a protective stoma in LAR significantly reduces the rate of anastomotic leakage and the number of reoperations related to leakage.

Overall, this meta-analysis has certain limitations. First, there was only a small number of RCTs available for inclusion. Although no detectable publication bias was observed in the funnel plot, the overall methodological quality and reporting of the included studies were poor. Because of limitations of medical ethics, not all of the studies were randomized controlled trials, and the sample size of some studies was rather low[42]. Second, among the studies included in the analysis, some included only patients undergoing elective surgery, whereas others included patients undergoing elective or emergency surgery for colorectal anastomoses. This discrepancy may have introduced some bias that would have contributed significantly to the analysis. Third, considerable selection bias existed in some of the included studies. Surgeons relied on their personal experiences to predict the patients who were at high risk of an anastomotic leakage, which may have been inaccurate and is suggestive of a potential selection bias among those who underwent stoma formation. Anastomotic leakage is unpredictable, as it can also occur in patients with no obvious risk factors. However, in some of the retrospective and prospective studies, the so-called high-risk patients were included in the protective stoma group.

In the light of these findings, the use of a protective stoma is an effective approach for reducing the rate of anastomotic leakage in patients who undergo LAR for rectal cancer. The morbidity associated with protective stoma and the complications of stoma closure are negligible compared with the reoperations required for anastomosis leakage in the absence of protective stoma. Therefore, non-functioning stoma can be useful for patients undergoing rectal surgery and is recommended during a LAR for rectal cancer. Future randomized controlled trials are needed to address the long-term mortality and quality of life issues related to protective stoma in LAR for rectal cancer.

COMMENTS

Background

Anastomotic leakage remains one the most significant complications after low anterior resection (LAR). Recent studies have demonstrated that the use of a protective stoma can reduce morbidity in LAR for rectal cancer, but the necessity of this procedure remains controversial.

Research frontiers

Over the last decade, the problem of anastomotic leakage has been widely addressed in multiple symposia and many publications. Although the use of a protective stoma is widely applied in LAR for rectal cancer, it remains unclear whether the protective stoma is useful for patients. Therefore, we performed this meta-analysis to investigate whether a protective stoma affects the outcomes of patients undergoing LAR for rectal cancer.

Innovations and breakthroughs

Based on this meta-analysis, the use of a protective stoma is an effective means of reducing the rate of anastomotic leakage in patients who receive LAR for rectal cancer. The morbidity associated with protective stoma usage and the complications of stoma closure are negligible compared with the reoperations required for anastomosis leakage in the absence of a protective stoma.

Applications

A protective stoma can be useful for patients undergoing rectal surgery and is recommended during LAR for rectal cancer. Future randomized controlled trials are needed to address the long-term mortality and quality of life issues related to protective stoma usage in LARs for rectal cancer.

Peer review

This is a meta-analysis study on the necessity of protective stoma in low anterior resection with total mesorectal excision (TME) for rectal cancer.Its publication seems important in a time of intense and controversial discussion about the necessity of protective stoma in low anterior resection with TME for rectal cancer.

Footnotes

P- Reviewer: Gaertner W, Kanellos I, Parellada CM, Sgourakis G, Ukleja, Xia HHX S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wang CH

References

- 1.Griffen FD, Knight CD, Whitaker JM, Knight CD. The double stapling technique for low anterior resection. Results, modifications, and observations. Ann Surg. 1990;211:745–751; discussion 751-752. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199006000-00014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rahbari NN, Weitz J, Hohenberger W, Heald RJ, Moran B, Ulrich A, Holm T, Wong WD, Tiret E, Moriya Y, et al. Definition and grading of anastomotic leakage following anterior resection of the rectum: a proposal by the International Study Group of Rectal Cancer. Surgery. 2010;147:339–351. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2009.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bruce J, Krukowski ZH, Al-Khairy G, Russell EM, Park KG. Systematic review of the definition and measurement of anastomotic leak after gastrointestinal surgery. Br J Surg. 2001;88:1157–1168. doi: 10.1046/j.0007-1323.2001.01829.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bertelsen CA, Andreasen AH, Jørgensen T, Harling H. Anastomotic leakage after curative anterior resection for rectal cancer: short and long-term outcome. Colorectal Dis. 2010;12:e76–e81. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2009.01935.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eberl T, Jagoditsch M, Klingler A, Tschmelitsch J. Risk factors for anastomotic leakage after resection for rectal cancer. Am J Surg. 2008;196:592–598. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2007.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lipska MA, Bissett IP, Parry BR, Merrie AE. Anastomotic leakage after lower gastrointestinal anastomosis: men are at a higher risk. ANZ J Surg. 2006;76:579–585. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.2006.03780.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McArdle CS, McMillan DC, Hole DJ. Impact of anastomotic leakage on long-term survival of patients undergoing curative resection for colorectal cancer. Br J Surg. 2005;92:1150–1154. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nesbakken A, Nygaard K, Lunde OC. Outcome and late functional results after anastomotic leakage following mesorectal excision for rectal cancer. Br J Surg. 2001;88:400–404. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.2001.01719.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jung SH, Yu CS, Choi PW, Kim DD, Park IJ, Kim HC, Kim JC. Risk factors and oncologic impact of anastomotic leakage after rectal cancer surgery. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008;51:902–908. doi: 10.1007/s10350-008-9272-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Law WL, Choi HK, Lee YM, Ho JW, Seto CL. Anastomotic leakage is associated with poor long-term outcome in patients after curative colorectal resection for malignancy. J Gastrointest Surg. 2007;11:8–15. doi: 10.1007/s11605-006-0049-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ptok H, Marusch F, Meyer F, Schubert D, Gastinger I, Lippert H. Impact of anastomotic leakage on oncological outcome after rectal cancer resection. Br J Surg. 2007;94:1548–1554. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bakx R, Busch OR, Bemelman WA, Veldink GJ, Slors JF, van Lanschot JJ. Morbidity of temporary loop ileostomies. Dig Surg. 2004;21:277–281. doi: 10.1159/000080201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cipe G, Erkek B, Kuzu A, Gecim E. Morbidity and mortality after the closure of a protective loop ileostomy: analysis of possible predictors. Hepatogastroenterology. 2012;59:2168–2172. doi: 10.5754/hge12115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hallböök O, Matthiessen P, Leinsköld T, Nyström PO, Sjödahl R. Safety of the temporary loop ileostomy. Colorectal Dis. 2002;4:361–364. doi: 10.1046/j.1463-1318.2002.00398.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaiser AM, Israelit S, Klaristenfeld D, Selvindoss P, Vukasin P, Ault G, Beart RW. Morbidity of ostomy takedown. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12:437–441. doi: 10.1007/s11605-007-0457-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Laurent C, Nobili S, Rullier A, Vendrely V, Saric J, Rullier E. Efforts to improve local control in rectal cancer compromise survival by the potential morbidity of optimal mesorectal excision. J Am Coll Surg. 2006;203:684–691. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2006.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Law WL, Chu KW, Choi HK. Randomized clinical trial comparing loop ileostomy and loop transverse colostomy for faecal diversion following total mesorectal excision. Br J Surg. 2002;89:704–708. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.2002.02082.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van Westreenen HL, Visser A, Tanis PJ, Bemelman WA. Morbidity related to defunctioning ileostomy closure after ileal pouch-anal anastomosis and low colonic anastomosis. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2012;27:49–54. doi: 10.1007/s00384-011-1276-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bradburn MJ, Deeks JJ, Berlin JA, Russell Localio A. Much ado about nothing: a comparison of the performance of meta-analytical methods with rare events. Stat Med. 2007;26:53–77. doi: 10.1002/sim.2528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Beirens K, Penninckx F. Defunctioning stoma and anastomotic leak rate after total mesorectal excision with coloanal anastomosis in the context of PROCARE. Acta Chir Belg. 2012;112:10–14. doi: 10.1080/00015458.2012.11680789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chude GG, Rayate NV, Patris V, Koshariya M, Jagad R, Kawamoto J, Lygidakis NJ. Defunctioning loop ileostomy with low anterior resection for distal rectal cancer: should we make an ileostomy as a routine procedure? A prospective randomized study. Hepatogastroenterology. 2008;55:1562–1567. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gong H, Yu Y, Yao Y. Clinical value of preventative ileostomy following ultra-low anterior rectal resection. Cell Biochem Biophys. 2013;65:491–493. doi: 10.1007/s12013-012-9445-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Karahasanoglu T, Hamzaoglu I, Baca B, Aytac E, Erenler I, Erdamar S. Evaluation of diverting ileostomy in laparoscopic low anterior resection for rectal cancer. Asian J Surg. 2011;34:63–68. doi: 10.1016/S1015-9584(11)60021-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lefebure B, Tuech JJ, Bridoux V, Costaglioli B, Scotte M, Teniere P, Michot F. Evaluation of selective defunctioning stoma after low anterior resection for rectal cancer. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2008;23:283–288. doi: 10.1007/s00384-007-0380-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ma CC, Wu SW. Retrospective analysis of protective stoma after low anterior resection for rectal cancer with total mesorectal excision: three-year follow-up results. Hepatogastroenterology. 2013;60:420–424. doi: 10.5754/hge12830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Matthiessen P, Hallböök O, Rutegård J, Simert G, Sjödahl R. Defunctioning stoma reduces symptomatic anastomotic leakage after low anterior resection of the rectum for cancer: a randomized multicenter trial. Ann Surg. 2007;246:207–214. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3180603024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nurkin S, Kakarla VR, Ruiz DE, Cance WG, Tiszenkel HI. The role of faecal diversion in low rectal cancer: a review of 1791 patients having rectal resection with anastomosis for cancer, with and without a proximal stoma. Colorectal Dis. 2013;15:e309–e316. doi: 10.1111/codi.12248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Seo SI, Yu CS, Kim GS, Lee JL, Yoon YS, Kim CW, Lim SB, Kim JC. The Role of Diverting Stoma After an Ultra-low Anterior Resection for Rectal Cancer. Ann Coloproctol. 2013;29:66–71. doi: 10.3393/ac.2013.29.2.66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shiomi A, Ito M, Saito N, Hirai T, Ohue M, Kubo Y, Takii Y, Sudo T, Kotake M, Moriya Y. The indications for a diverting stoma in low anterior resection for rectal cancer: a prospective multicentre study of 222 patients from Japanese cancer centers. Colorectal Dis. 2011;13:1384–1389. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2010.02481.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ulrich AB, Seiler C, Rahbari N, Weitz J, Büchler MW. Diverting stoma after low anterior resection: more arguments in favor. Dis Colon Rectum. 2009;52:412–418. doi: 10.1007/DCR.0b013e318197e1b1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wibe A, Eriksen MT, Syse A, Myrvold HE, Søreide O. Total mesorectal excision for rectal cancer--what can be achieved by a national audit? Colorectal Dis. 2003;5:471–477. doi: 10.1046/j.1463-1318.2003.00506.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Peeters KC, Tollenaar RA, Marijnen CA, Klein Kranenbarg E, Steup WH, Wiggers T, Rutten HJ, van de Velde CJ. Risk factors for anastomotic failure after total mesorectal excision of rectal cancer. Br J Surg. 2005;92:211–216. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rullier E, Laurent C, Bretagnol F, Rullier A, Vendrely V, Zerbib F. Sphincter-saving resection for all rectal carcinomas: the end of the 2-cm distal rule. Ann Surg. 2005;241:465–469. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000154551.06768.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Law WL, Chu KW. Anterior resection for rectal cancer with mesorectal excision: a prospective evaluation of 622 patients. Ann Surg. 2004;240:260–268. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000133185.23514.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Matthiessen P, Hallböök O, Andersson M, Rutegård J, Sjödahl R. Risk factors for anastomotic leakage after anterior resection of the rectum. Colorectal Dis. 2004;6:462–469. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2004.00657.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen J, Wang DR, Yu HF, Zhao ZK, Wang LH, Li YK. Defunctioning stoma in low anterior resection for rectal cancer: a meta- analysis of five recent studies. Hepatogastroenterology. 2012;59:1828–1831. doi: 10.5754/hge11786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moran BJ. Predicting the risk and diminishing the consequences of anastomotic leakage after anterior resection for rectal cancer. Acta Chir Iugosl. 2010;57:47–50. doi: 10.2298/aci1003047m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gastinger I, Marusch F, Steinert R, Wolff S, Koeckerling F, Lippert H. Protective defunctioning stoma in low anterior resection for rectal carcinoma. Br J Surg. 2005;92:1137–1142. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tsunoda A, Tsunoda Y, Narita K, Watanabe M, Nakao K, Kusano M. Quality of life after low anterior resection and temporary loop ileostomy. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008;51:218–222. doi: 10.1007/s10350-007-9101-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pakkastie TE, Ovaska JT, Pekkala ES, Luukkonen PE, Järvinen HJ. A randomised study of colostomies in low colorectal anastomoses. Eur J Surg. 1997;163:929–933. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ng TT, McGory ML, Ko CY, Maggard MA. Meta-analysis in surgery: methods and limitations. Arch Surg. 2006;141:1125–1130; discussion 1131. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.141.11.1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]