Abstract

Holloway, Cameron J., Andrew J. Murray, Kay Mitchell, Daniel S. Martin, Andrew W. Johnson, Lowri E. Cochlin, Ion Codreanu, Sundeep Dhillon, George W. Rodway, Tom Ashmore, Denny Z.H. Levett, Stefan Neubauer, Hugh E. Montgomery, Michael P.W. Grocott, and Kieran Clarke, on behalf of the Caudwell Xtreme Everest 2009 Investigators. Oral Coenzyme Q supplementation does not prevent cardiac alterations during a high altitude trek to Everest Base Camp. High Alt Med Biol 15:000—000, 2014.—Exposure to high altitude is associated with sustained, but reversible, changes in cardiac mass, diastolic function, and high-energy phosphate metabolism. Whilst the underlying mechanisms remain elusive, tissue hypoxia increases generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), which can stabilize hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) transcription factors, bringing about transcriptional changes that suppress oxidative phosphorylation and activate autophagy. We therefore investigated whether oral supplementation with an antioxidant, Coenzyme Q10, prevented the cardiac perturbations associated with altitude exposure. Twenty-three volunteers (10 male, 13 female, 46±3 years) were recruited from the 2009 Caudwell Xtreme Everest Research Treks and studied before, and within 48 h of return from, a 17-day trek to Everest Base Camp, with subjects receiving either no intervention (controls) or 300 mg Coenzyme Q10 per day throughout altitude exposure. Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging and echocardiography were used to assess cardiac morphology and function. Following altitude exposure, body mass fell by 3 kg in all subjects (p<0.001), associated with a loss of body fat and a fall in BMI. Post-trek, left ventricular mass had decreased by 11% in controls (p<0.05) and by 16% in Coenzyme Q10-treated subjects (p<0.001), whereas mitral inflow E/A had decreased by 18% in controls (p<0.05) and by 21% in Coenzyme Q10-treated subjects (p<0.05). Coenzyme Q10 supplementation did not, therefore, prevent the loss of left ventricular mass or change in diastolic function that occurred following a trek to Everest Base Camp.

Key Words: : altitude, Coenzyme Q10, cardiac metabolism, heart function, hypoxia

Introduction

Exposure to high altitude is associated with sustained, but reversible, changes in cardiac mass, diastolic function, and high-energy phosphate metabolism in healthy, young individuals (Holloway et al., 2011). The mechanism(s) underlying this response remain elusive, though the loss of left ventricular mass may be an autophagic process analogous to the wasting of skeletal muscle mass after hypoxic exposure (Howald et al., 2003). The diastolic impairment may result from the energetic impairment in the hearts of the same individuals (Holloway et al., 2011), since cardiac diastole depends on ATP (Tian et al., 1997). Diastolic dysfunction has also been noted in humans exposed to simulated altitude in hypoxic chambers (Boussuges et al., 2000; Kjaergaard et al., 2006).

In hypoxic human skeletal muscle, downregulation of electron transport chain complex I and loss of mitochondrial density (Murray 2009; Levett et al., 2012) underlie a suppression of tissue oxygen demand, associated with altered energetics (Edwards et al., 2010). Whilst it is not known whether similar responses underlie the impaired energetics of the hypoxic human heart, decreased mitochondrial respiration rates and decreased complex I were found in the mitochondria of the chronically-hypoxic rat heart (Heather et al., 2012).

The cellular response to hypoxia is regulated by the hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) transcription factors (Semenza, 2007). Oxidative stress enhances HIF stabilisation (Guzy et al., 2006), and thus we sought to investigate if oral antioxidant supplementation could prevent the cardiac perturbations that occur in humans at high altitude. Coenzyme Q10 is a lipid-soluble quinone, present in all cell membranes, and is particularly enriched in the inner mitochondrial membrane where it forms a component of the electron transport chain (Crane, 2001). In its predominant ubiquinol form, Coenzyme Q10 accepts electrons from complexes I and II, but can additionally scavenge free radicals (Crane, 2001). Lipid peroxidation is enhanced in Coenzyme Q10-deficient yeast (Poon et al., 1997), demonstrating this antioxidant function, whilst Coenzyme Q10 supplementation improved physical performance in humans on a cycle ergometer (Mizuno et al., 2008).

The aim of this study was to test the hypothesis that, in human subjects, oral Coenzyme Q10 would reduce the falls in cardiac mass, diastolic function, and cardiac energetics that are observed following a trek to Everest Base Camp (Holloway et al., 2011). Alongside these primary outcome measures, secondary measures included body composition analysis, heart rate, blood pressure, cardiac volumes, plasma metabolite levels, and blood composition.

Methods

Summary

In an assessor-blinded controlled trial, we measured cardiac morphology, function, and high-energy phosphate metabolism in the hearts of healthy human subjects before a trek to Mt. Everest Base Camp, Nepal, following an identical ascent profile to that used in our previous study (Levett et al., 2010; Holloway et al., 2011). Following baseline testing, subjects were randomly allocated to receive either no intervention (control) or Coenzyme Q10 throughout the duration of the trek. Subjects were then studied within 48 h of returning to the UK post-trek with investigators blinded throughout as to treatment group.

Subjects and setting

Twenty-three volunteers (10 male, 13 female, aged 46±3 years) were recruited from the 2009 Caudwell Xtreme Everest Research Treks. The subjects underwent two independent medical assessments prior to acceptance for participation in the study and were healthy, recreationally-active, nonsmokers. No subjects were recreational climbers or had ascended above 1500 m within 1 year of baseline tests. Throughout the study, subjects refrained from taking any AMS prophylactic medications, steroids, diuretics, or vitamin supplements. The research was carried out according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. All subjects gave written informed consent and approval was obtained from the University College London Ethics Committee.

Baseline studies took place at the University of Oxford Centre for Clinical Magnetic Resonance Research (OCMR) within 1 month before leaving the UK (pre-trek). All subjects were tested after an overnight fast, but drinking water was encouraged. Assessment included blood sampling for biochemical analysis, body weight and composition measurements, electrocardiography, transthoracic echocardiography, and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging and spectroscopy. Following baseline testing, subjects received either no treatment (controls, n=11) or 300 mg Coenzyme Q10 per day orally (n=12), commencing upon arrival in Kathmandu (1300 meters) and continuing throughout their exposure to high altitude until return to Kathmandu. During this time and prior to both testing days, all subjects refrained from taking other vitamins and supplements with possible antioxidant roles. Subjects ascended to Everest Base Camp (17,388 feet, 5300 m) over 11 days on an identical ascent profile to that used previously (Fig. 1) (Levett et al., 2010; Holloway et al., 2011). Subjects then spent 3 nights at Everest Base Camp before descending over 4 days and returning to London within 2 days. All study protocols were repeated within 48 h of the subjects returning to the UK (post-trek). Investigators in Oxford, who performed all assessments and analyses, were blinded to treatment status.

FIG. 1.

Ascent profile of subjects trekking to Everest Base Camp (5300 m).

Body weight and composition

Each subject was weighed upon arrival at OCMR and height was recorded for body mass index (BMI) and body surface area calculation. Body fat mass, lean mass, basal metabolic rate (BMR), and water percentage were measured using a bioimpedence analyzer (Bodystat, Douglas, UK).

Measurement of blood pressure, and cardiac volumes, mass, and function

Resting heart rate and systolic and diastolic blood pressure were measured after 10 min of lying flat. Left and right ventricular cardiac volumes, mass, and function were assessed using cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in a 1.5-T Siemens Sonata clinical scanner (Siemens, Erlangen, Germany). With the subjects in a supine position, pilot images were acquired, followed by horizontal and vertical long-axis cine images. A stack of steady-state, free precession (SSFP), short-axis cine images were subsequently obtained using breath holding and cardiac gating (Hudsmith et al., 2006). The short-axis images were obtained in a prospective manner from the base to the apex, in 1 cm-thick slices. Manual contouring of the left and right ventricular endocardium and epicardium of the short-axis cine images was performed. Using Argus processing, left and right ventricular volumes, ejections fractions, and left ventricular mass were obtained (Hudsmith et al., 2006). On average, 19 phases over each cardiac cycle were studied. Analysis was blinded and performed independently by two clinicians.

Assessment of mitral inflow patterns were made by transthoracic echocardiography using a Phillips 5000 sonograph (Phillips, Amsterdam, The Netherlands). Peak E- and A-wave velocities were obtained at the mitral valve tips in a four-chamber view with the subject in the left lateral position. Tissues Doppler velocities (E’) were additionally obtained from the basal septum in a four-chamber view. Twelve lead electrocardiograms were performed for accurate heart rate assessment.

Cardiac MR spectroscopy

31P-Magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) was used to determine cardiac PCr/ATP on a Siemens 3-T Tim Trio MR system (Siemens). Subjects lay prone with the left ventricle positioned over the center of a modified Siemens heart/liver 31P coil in the isocenter of the magnet. 31P-MRS was performed using 3-D acquisition-weighted chemical shift imaging (AW-CSI), using the UTE-CSI technique (TE=0.3 ms) in conjunction with an optimized radio frequency pulse centred between γ and α ATP resonances to maximize the signal-to-noise ratio, improve baseline artifacts, and to ensure uniform excitation of all spectral peaks (Tyler et al., 2009). The acquisition matrix size was 16×16×8 voxels, and the field of view was 240×240×200 mm, with 10 averages at k-space centre. All acquisitions were prospectively cardiac gated with data acquisition during diastole. Nuclear Overhauser enhancement (NOE) was used to increase the signal-to-noise ratio (Tyler et al., 2009).

Proton localization images were used to obtain short-axis left ventricular planes (Fig. 2). To reduce signal to noise, two saturation bands were placed over the anterior chest wall to decrease signal from PCr in skeletal muscle. The CSI grid was positioned on a slice designated as the first short-axis slice in which the papillary muscle became visible, and rotated to obtain three voxels containing midventricular septum (Fig. 2) (Tyler et al., 2009).

Fig. 2.

Voxel selection for 31P magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Voxel selection for cardiac 31P magnetic resonance spectroscopy, showing (A) two chamber cardiac image, (B) a four chamber image, and (C) a short axis image with the central voxel highlighted in the interventricular septum of a midventricular slice.

All analyses of cardiac spectra were performed by two independent spectroscopists after data masking. All PCr/ATP calculations between both spectroscopists were within 10% agreement, so all initial PCr/ATP measurements from the primary operator were reported. Nonlocalized inversion recovery spectra were acquired to measure the flip angle at a reference vial containing phenylphosphonic acid (PPA) located inside the radio frequency (RF) coil housing. This information was used in conjunction with a calculated RF field profile to determine and correct for the flip angle of the spectral voxels for every acquisition, using software developed in house in Matlab 6.5 (Mathworks, Natick, MA). The selected spectra were summed, pre-processed (DC and baseline correction), and fitted using the automated processing algorithm AMARES with the jMRUI software packages (Fig. 2). NOE, RF saturation correction factors (identified in previous experiments) and blood contamination correction factors were applied (Tyler et al., 2009).

Fasting plasma metabolites and blood composition analysis

Fasting blood samples were taken for metabolite analysis pre- and post-trek. Blood samples were immediately centrifuged at 1000 g at 4°C and plasma supernatant frozen at −80°C, with a final concentration of 30 μg/mL of tetrahydrolipstatin (a lipoprotein lipase inhibitor) added to one aliquot of samples for NEFA evaluation, as described previously (Murray et al., 2011). Plasma levels of glucose, lactate, triacylglycerol, cholesterol (total and HDL), β-hydroxybutyrate, and creatinine were measured using an ABX Pentra Clinical Chemistry bench-top analyser (Horiba, ABX, Montpellier, France). Plasma levels of nonesterified fatty acids (NEFA) were measured using an assay kit (Wako Chemicals, Neuss, Germany).

Whole blood samples were analyzed for hemoglobin content using a portable device (Hemocue, Dionfield, UK). Hematocrit and cell counts were performed at the University of Oxford NHS Trust commercial hematology laboratory, and no other measures of hematopoetic activation, such as erythropoietin concentrations (EPO), were made. Post-trek blood samples were not obtained from one subject in the control group and consequently this subject's pre-trek samples were excluded from analysis, decreasing the group size for these results to n=10.

Statistics

Power calculations, carried out a priori and informed by data acquired in our previous study, indicated that in order to measure biologically-significant changes in the primary endpoints (15% lower PCr/ATP, 15% lower early-to-late LV filling rates (E/A), and 10% loss of LV mass), 10–12 subjects were required per group. Results are expressed as means±standard deviation (SD). Mann-Whitney U tests were used to assess inter-group differences pre-trek. Paired Student's t tests were used within the subject groups to test for differences occurring as a result of exposure to altitude. ANCOVA analysis was used to test for an effect of condition (i.e., Coenzyme Q10 treatment) by examining post-test data between the subject groups, whilst controlling for pre-test scores. Differences were considered statistically significant when p≤0.05.

Results

Subjects

The subject groups were well-matched for age, sex, height (Table 1), weight, and body composition (Table 2). Cardiac morphology, function and energetics, hemodynamics, plasma metabolite concentrations, and blood composition were the same for both groups at baseline (Tables 3 and 4), with the exception of plasma lactate concentrations, which were higher (p<0.05) in the control group.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Subjects Assigned to Treatment Groups Prior to a Trek to Everest Base Camp

| Control (n=11) | Coenzyme Q10 (n=12) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 43.1±15.5 | 48.5±14.9 |

| Males/Females | 4/7 | 6/6 |

| Height (m) | 168±8 | 169±8 |

Data are expressed as means±SD.

Table 2.

Body Weight and Composition and Basal Metabolic Rate Analysis in Subjects Before and After a Trek to Everest Base Camp

| Control (n=11) | Coenzyme Q10 (n=12) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-Trek | Post-Trek | Pre-Trek | Post-Trek | |

| Body mass and composition | ||||

| Total body mass (kg) | 70±17 | 67±16*** | 70±14 | 67±12*** |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 24.7±4.6 | 23.8±4.3*** | 24.3±3.6 | 23.3±3.1*** |

| Lean body mass (kg) | 50.5±12.0 | 50.8±11.1 | 51.1±11.8 | 50.8±10.6 |

| Fat body mass (kg) | 19.0±9.9 | 16.5±8.7* | 18.5±4.3 | 16.2±4.2** |

| Water % of body weight | 54.8±6.7 | 57.6±6.8 | 55.4±4.7 | 57.8±6.3 |

| Basal metabolic rate | ||||

| BMR (kcal) | 1600±295 | 1588±266 | 1602±302 | 1591±278 |

| BMR (kcal/kg) | 23.4±3.4 | 24.0±3.0 | 23.2±1.9 | 23.8±2.2 |

Data are expressed as means±SD. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001 compared with corresponding Pre-Trek value within the same treatment group.

Table 3.

Hemodynamic, Cardiac Volume, and Cardiac Energetic Analysis in Subjects Before and After a Trek to Everest Base Camp

| Control (n=11) | Coenzyme Q10 (n=12) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-Trek | Post-Trek | Pre-Trek | Post-Trek | |

| Hemodynamics | ||||

| Heart rate (b.p.m.) | 58±7 | 60±9 | 59±10 | 60±9 |

| Systolic B.P. (mmHg) | 125±15 | 119±11 | 118±8 | 120±13 |

| Diastolic B.P. (mmHg) | 83±10 | 78±12* | 77±7 | 77±7 |

| Left ventricular volumes | ||||

| End diastolic volume (mL) | 126±31 | 122±22 | 131±33 | 125±37 |

| End systolic volume (mL) | 38±10 | 35±11 | 37±14 | 39±15 |

| Stroke volume (mL) | 89±21 | 87±14 | 95±22 | 86±24 |

| Ejection fraction (%) | 70±3 | 72±5 | 72±6 | 69±5 |

| Right ventricular volumes | ||||

| End diastolic volume (mL) | 136±35 | 134±29 | 142±31 | 133±38 |

| End systolic volume (mL) | 50±15 | 49±18 | 52±13 | 52±21 |

| Stroke volume (mL) | 86±21 | 84±15 | 90±18 | 82±22 |

| Ejection fraction (%) | 63±6 | 64±7 | 63±3 | 62±8 |

| Cardiac energetics | n=7 | n=11 | ||

| PCr/ATP | 1.77±0.38 | 1.68±0.31 | 1.67±0.29 | 1.51±0.28 |

Data are expressed as means±SD. *p<0.05 compared with corresponding Pre-Trek value within the same treatment group.

Table 4.

Plasma Metabolite and Blood Composition Analysis in Subjects Before and After a Trek to Everest Base Camp

| Control (n=10) | Coenzyme Q10 (n=12) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-Trek | Post-Trek | Pre-Trek | Post-Trek | |

| Plasma metabolites | ||||

| Glucose (mmol/L) | 4.8±0.3 | 4.7±0.2 | 4.9±0.4 | 4.8±0.4 |

| Lactate (mmol/L) | 0.9±0.3 | 0.6±0.2** | 0.5±0.2† | 0.6±0.5 |

| NEFA (mmol/L) | 0.46±0.25 | 0.25±0.11** | 0.40±0.35 | 0.37±0.28 |

| Triacylglycerol (mmol/L) | 1.0±0.4 | 1.2±0.7 | 1.1±0.8 | 1.0±0.7 |

| Total cholesterol (mmol/L) | 4.9±0.4 | 4.5±1.0 | 5.1±0.8 | 4.3±0.7*** |

| HDL-cholesterol (mmol/L) | 1.8±0.3 | 1.5±0.3 | 1.7±0.4 | 1.4±0.3** |

| β-Hydroxybutyrate (mmol/L) | 0.07±0.08 | 0.06±0.08 | 0.12±0.11 | 0.15±0.27 |

| Creatinine (μmol/L) | 92±9 | 91±11 | 89±10 | 88±10 |

| Blood composition | ||||

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 14.4±1.6 | 14.8±1.3 | 13.9±1.4 | 14.3±1.9 |

| Hematocrit (%) | 43.1±4.4 | 44.3±3.3 | 41.6±3.2 | 43.2±5.1 |

| Red blood cell count (1012/L) | 4.7±0.6 | 4.8±0.5 | 4.6±0.4 | 4.8±0.5 |

| White blood cell count (109/L) | 6.9±1.3 | 7.3±2.8 | 6.7±1.3 | 7.4±4.0 |

| Platelet count (109/L) | 233±30 | 265±42* | 242±34 | 277±65* |

Data are expressed as means±SD. †p<0.05 compared with corresponding Pre-Trek value in control group. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001 compared with corresponding Pre-Trek value within the same treatment group.

All subjects successfully completed the trek to Everest Base Camp in compliance with the planned ascent profile. No subject became unwell or required supplemental oxygen during the study.

Body weight and composition

Total body mass fell by 3 kg on average in subjects during the trek (p<0.001), with no difference between the controls and those receiving Coenzyme Q10, resulting in a fall in BMI (p<0.001; Table 2). According to the bioimpedence analyses, subjects did not lose lean body mass or body water as a result of the trek, although fat mass fell by 13% and 12% in the control (p<0.05) and Coenzyme Q10-treated (p<0.01) groups, respectively (Table 2). Coenzyme Q10 treatment did not affect the changes in body mass (p=0.795) or composition associated with high-altitude exposure (p=0.872 for fat mass). Basal metabolic rate did not change in either group following the trek (Table 2).

Blood pressure, cardiac volumes, mass, and function

Heart rate and systolic blood pressure did not change in either group as a result of the trek. Diastolic blood pressure fell by 6% in the control group (p<0.05) and did not significantly change in the Coenzyme Q10-treated group (Table 3). However, according to ANCOVA analysis, which accounts for differences in pre-test scores, diastolic blood pressure was not significantly altered by Coenzyme Q10 supplementation (p=0.07).

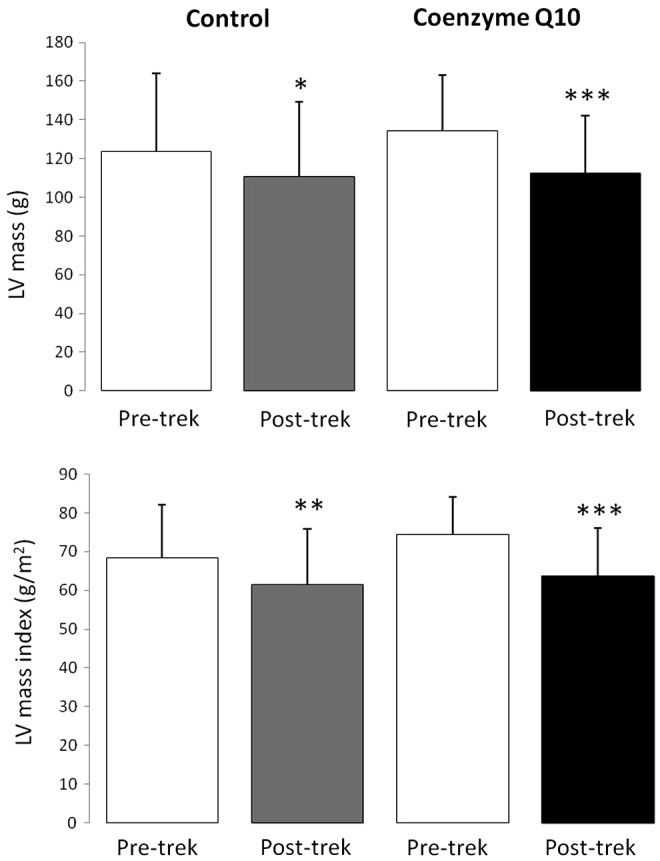

After return from Everest Base Camp, absolute left ventricular mass had decreased by 11% in the control group (p<0.05) and by 16% in the Coenzyme Q10-treated group (p<0.001), whilst left ventricular mass corrected for body surface area decreased by 10% in the control group (p<0.01) and 14% in the Coenzyme Q10-treated group (p<0.001; Fig. 3). Thus, Coenzyme Q10 treatment did not prevent the loss of LV mass associated with high-altitude exposure (p=0.234).

FIG. 3.

Absolute left ventricular mass (upper panel) and left ventricular mass corrected for body surface area (lower panel) in subjects before and after a trek to Everest Base Camp. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001 compared with corresponding Pre-Trek value within the same treatment group.

Left and right ventricular end diastolic volumes, end systolic volumes, stroke volumes, and ejection fractions did not change in either group post-trek (Table 3). Left ventricular diastolic filling parameters were altered in subjects post-trek (Fig. 4). Including all subjects from both groups, the average E/A decreased 24% (p<0.01) and E’ decreased 13% from 11 to 9.7 cm/sec (p=0.01). In the control group alone, mitral inflow E/A decreased by 18% post-trek (p<0.05), with no significant changes in either peak E-wave or A-wave velocities. In the Coenzyme Q10-treated group, E/A fell by 21% (p<0.05) alongside an 18% fall in peak E-wave velocity in this group (p<0.01) but no change in the peak A-wave velocity. Coenzyme Q10 did not alter the pattern of ventricular filling associated with high altitude exposure (p=0.593 for an effect on E/A). There were borderline significant septal tissue Doppler (E’) changes in the control group after the trek (11.6 to 9.8 cm/sec, p=0.05), whereas there were similar changes in the Coenzyme Q10 group from 10.3 to 9.6 cm/s, which did not reach significance (p=0.08). E/E’ measurements were not calculated due to concerns regarding validity of interpretation of this ratio in healthy subjects (Firstenberg et al., 2000).

FIG. 4.

Left ventricular diastolic filling parameters in subjects before and after a trek to Everest Base Camp. *p<0.05, **p<0.01 compared with corresponding Pre-Trek value within the same treatment group.

Cardiac high-energy phosphate metabolism

Due to technical issues (unrelated to the subjects), pre- and post-trek MR spectra for cardiac high-energy phosphate analysis were obtained on fewer subjects (n=7 for the control group, n=11 for the Coenzyme Q10 group), making this measurement statistically underpowered. Nevertheless, there was a nonsignificant fall in cardiac PCr/ATP post-trek in both groups (Table 3), with 5 of the 7 control subjects and 8 of the 11 Coenzyme Q10-treated subjects showing decreased myocardial PCr/ATP post-trek.

Plasma metabolites and blood composition

Plasma glucose, triacylglycerol, β-hydroxybutyrate, and creatinine levels were not altered in either subject group following exposure to hypobaric hypoxia. Plasma lactate and NEFA levels fell by 33% (p<0.01) and 46% (p<0.01), respectively, in the control subjects, but were unaltered in those receiving Coenzyme Q10 (Table 4). Meanwhile, total and HDL-cholesterol fell in the Coenzyme Q10-treated group by 16% (p<0.001) and 18% (p<0.01), respectively, but were unaltered in the control group (Table 4). Coenzyme Q10 supplementation did not, however, affect any of these measures (p=0.204 for an effect on lactate, p=0.181 for an effect on NEFA, p=0.811 for an effect on total cholesterol, p=0.844 for an effect on HDL-cholesterol) or any other plasma metabolite.

Circulating hemoglobin concentration, hematocrit, red blood cell count, and white blood cell count did not significantly increase in either group following high-altitude exposure, however circulating platelets increased by 14% in both groups post-trek (p<0.05; Table 4). Coenzyme Q10 supplementation did not have a significant effect on any aspect of blood composition.

Discussion

In agreement with our previous findings, exposure to high altitude a trek to Everest Base Camp led to decreased cardiac mass and alterations in diastolic parameters in human subjects. Changes in mass and diastolic function were associated with decreased cardiac energetics in most subjects, as measured by a lower PCr/ATP post-trek. Coenzyme Q10 supplementation, however, did not alter any of the cardiac changes associated with high altitude exposure.

A strength of this study lies in the use of a rigorously-implemented, consistent ascent profile identical to that of our previous study (Holloway et al., 2011; Levett et al., 2010). The same techniques and equipment were used on the same site to assess cardiac function, morphology, and energetics in the subjects, and the same lead investigator oversaw all testing. Additional measures performed on these subjects included measurement of blood plasma metabolites, blood composition, and basal metabolic rates, in order to give a more complete picture of the metabolic response to high altitude exposure. The average age of subjects recruited into this study was higher than that in our previous study (46±3 years compared with 38±3 years) and this, along with the higher proportion of female subjects, probably resulted in differences in baseline values. Moreover, the greater range of subject ages in the current study may have increased the data variability at baseline, although ANCOVA analysis allows this to be accounted for. A weakness of the present study is that, as a consequence of practical difficulties, the sample size was probably inadequate to detect changes in high energy phosphate metabolism using MRS techniques (n=7 and 11 per group), compared with our previous study (n=14). Due to these technical problems, a full complement of pre- and post-trek 31P-spectra could only be acquired on this limited number of the subjects. Based on the changes in left ventricular mass and diastolic function from the previous study, however, we were adequately powered to determine differences in both controls and the Coenzyme Q10-treated groups on these measures. This investigation took place during the Caudwell Xtreme Everest 2009 Research Treks, which involved fewer subjects and investigators than Caudwell Xtreme Everest 2007 and with more limited research facilities in the field. As a consequence, we were unable to preserve blood samples during the expedition, and we can therefore only present data from blood samples collected at sea-level before and after the trek to Everest Base Camp. With a smaller number of subjects available, we were only able to test one dose of Coenzyme Q10, which is a limitation of the study, however the dose tested (300 mg) is at the higher end of those used experimentally and has been previously shown to be effective in allaying the onset of fatigue in humans when cycling (Mizuno et al., 2008). Unlike our previous study (Holloway et al., 2011), we did not perform follow-up studies on the subjects to investigate the possible reversal of the altitude-induced changes, and neither did we investigate parallel changes in skeletal muscle metabolism or energetics (Edwards et al., 2010; Levett et al., 2012). Finally, we recognize that there are potential confounding factors involved with carrying out studies in a high-altitude environment in a developing nation, compared with controlled studies in a hypobaric or normobaric hypoxia chamber at sea level.

Nevertheless, the findings of the present study show good agreement with our previous findings in healthy, young, untreated subjects following an ascent to Everest Base Camp. For instance, the degree to which left ventricular mass was lost in both controls and Coenzyme Q10-treated subjects in this study was very similar to the 11% loss in our previous study (Holloway et al., 2011). Meanwhile, the 18%–21% reduction of mitral inflow E/A agreed well with 17% reduction observed previously (Holloway et al., 2011). Moreover, in the whole group, we also saw reduced septal tissue Doppler measurements, in line with changes in diastolic function. It is worth noting that mitral inflow changes with loading conditions, being affected by hydration and pulmonary pressures, and the changes in E/A and E’ measured here are within normal ranges. More detailed MRI assessment of LV diastolic parameters with accompanying invasive right heart catheters and direct measurements of cardiac hemodynamics may provide more insight into the changes in mitral inflow patterns following high altitude exposure. In contrast to our previous study, we did not find a significant decrease in left ventricular stroke volume in either group of subjects post-trek (Holloway et al., 2011), although it is worth noting that baseline stroke volumes were lower in this study, possibly due to different subject characteristics. A similar degree of whole body weight loss in the present study was accompanied by a loss of body fat mass, which was not significant in our previous study (Holloway et al., 2011).

No significant elevations in hemoglobin concentration or hematocrit were observed in the subjects following exposure to altitude. This may be due a partial reversal of altitude-induced hemoconcentration once the subjects returned to sea level, and the small number of subjects in each group, or the exposure may have been too brief to induce such an increase. Notably, however, platelet counts were elevated in both groups post-trek. Finally, although we did observe statistically significant differences in plasma NEFA and cholesterol levels between the groups, we are not aware of a mechanism that might underlie these observations.

Coenzyme Q10 supplementation did not alter the cardiac response to a trek to Everest Base Camp, and there are a number of possible reasons for this. First, it is not clear what mechanism(s) underlie the cardiac response during ascent to 5300 m, and oxidative stress may not in fact be a critical factor. Indeed, the degree of oxidative stress may have been limited by a deliberately slow ascent profile that was designed to aid acclimatization and minimize incidence of acute mountain sickness. In subjects on an identical ascent profile, we previously reported elevated levels of three plasma biomarkers of oxidative stress, namely increased levels of 8-iso-prostaglandin F2a and 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal and a decrease in the ratio of reduced/oxidized glutathione (Levett et al., 2011). Curiously, all three markers peaked at altitudes lower than 5300 m, perhaps suggesting that antioxidant compensation is a key facet of acclimatization during a gradual ascent. Alternatively, oxidative stress may be a factor and the dose of Coenzyme Q10 used in this study, whilst effective in allaying fatigue in humans following an exercise challenge (Mizuno et al., 2008), may not have provided sufficient antioxidant protection against the levels of ROS generated at extreme high altitude.

In the present study, we did not have the infrastructure in place to collect, centrifuge, freeze, and maintain blood samples in the field, so we are unfortunately unable to report any plasma-borne biomarkers of ROS metabolism. Moreover, it is clearly not possible to measure the degree of cardiac oxidative stress in humans in the field and thus we could not assess the efficacy of Coenzyme Q10 supplementation as an antioxidant therapy for the heart. Studies of animal models of hypoxia, plasma biomarkers of oxidative stress at altitude, or even oxidative stress levels in more readily accessible human tissues such as skeletal muscle, which can be safely biopsied in the field (Levett et al., 2012; Murray 2013), might prove to be fruitful in this regard in future investigations. Finally, whilst it is possible that any beneficial effects of Coenzyme Q10 could be masked by consumption of a diet which is exceptionally high in antioxidants, this was unlikely in our subjects due to the paucity of fresh fruit and vegetables available during the trek to Everest Base Camp.

At present, we are therefore unable to confirm or refute the potential mechanism of ROS-mediated HIF-stabilization underlying the cardiac response to altitude, and as such the efficacy of alternative antioxidant therapies should not be inferred from these findings. Indeed, Coenzyme Q10, whilst naturally enriched in mitochondrial membranes, accumulates in all cellular membranes (Crane, 2001) and a mitochondrial-targeted antioxidant might prove more effective as a therapeutic strategy. Notably, MitoQ, a mitochondrial matrix-targeted Coenzyme Q10 derivative, was found to completely abolish superoxide-activated mitochondrial uncoupling in rat kidney mitochondria, even at low doses, whilst nontargeted antioxidants, including other lipid-soluble quinone derivatives, were ineffective in this regard (Echtay et al., 2002).

In summary, we have found that Coenzyme Q10 supplementation does not prevent the loss of left ventricular mass or altered diastolic function during a trek to Everest Base Camp. Whilst our findings do not disprove a mechanistic role for ROS-mediated HIF-stabilization and downstream mitochondrial abnormalities in the cardiac response to high altitude exposure, further work is required to establish the underlying mechanism before alternative therapies are tested.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Mrs. Emma Carter for performing analysis on blood samples, and Mr. Blaine Landis for his advice on statistical analysis. AJM thanks the Research Councils UK for supporting his Academic Fellowship. CJH is currently funded by the Australian Heart Foundation, although he was funded by the BHF to run this study. The authors thank the Caudwell Xtreme Everest 2009 trekker subjects who trekked to Everest Base Camp and contributed their time, data, and money to support this study.

MPWG holds the British Oxygen Company Chair of Anaesthesia at the Royal College of Anaesthetists. DSM and DZHL were Critical Care Scholars of the London Clinic. MPWG and KM are funded in part by the University Hospitals Southampton NHS Foundation Trust–University of Southampton Respiratory Biomedical Research Unit, which received a portion of its funding from the United Kingdom Department of Health's National Institute of Health Research Biomedical Research Unit funding scheme. DSM and HEM are funded in part by the University College London Hospital–University College London Biomedical Research Centre, which received a portion of its funding from the United Kingdom Department of Health's National Institute of Health Research Biomedical Research Centre funding scheme.

Supported by Mr John Caudwell, BOC Medical (now part of Linde Gas Therapeutics), Eli Lilly, the London Clinic, Smiths Medical, Deltex Medical, and the Rolex Foundation (unrestricted grants), the Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland, the United Kingdom Intensive Care Foundation, the Sir Halley Stewart Trust, UCL Centre of Altitude, Space and Extreme Environment Medicine, and the Portex Unit, Institute of Child Health. The British Heart Foundation funded this study via Programme Grant number RG/07/004.

Caudwell Xtreme Everest 2009 is a research project coordinated by the Centre for Altitude, Space, and Extreme Environment Medicine, University College London. Membership, roles, and responsibilities of the Caudwell Xtreme Everest 2009 Research Group can be found at www.caudwell-xtreme-everest.co.uk/team. Members of the Caudwell Xtreme Everest 2009 Research Group: Sundeep Dhillon, Mike Grocott, Maryam Koshravi, Daniel Martin, Kay Mitchell (leader). Alan Richardson, George Rodway, Liesl Wandrag.

Author Disclosure Statement

MPWG, KM, DSM, and DZHL serve on the executive board of the Caudwell Xtreme Everest Research Group. AJM, KM, DZHL, DSM, HEM, and MPWG are members of the Scientific Strategy Board of the Caudwell Xtreme Everest Research Group.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- Boussuges A, Molenat F, Burnet H, et al. (2000). Operation Everest III (Comex ‘97): Modifications of cardiac function secondary to altitude-induced hypoxia. An echocardiographic and Doppler study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 161:264–270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crane FL. (2001). Biochemical functions of Coenzyme Q10. J Am Coll Nutr 20:591–598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Echtay KS, Murphy MP, Smith RA, Talbot DA, and Brand MD. (2002). Superoxide activates mitochondrial uncoupling protein 2 from the matrix side. Studies using targeted antioxidants. J Biol Chem 277:47129–47135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards LM, Murray AJ, Tyler DJ, et al. (2010). The effect of high-altitude on human skeletal muscle energetics: P-MRS results from the Caudwell Xtreme Everest expedition. PLoS One 5:e10681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Firstenberg MS, Levine BD, Garcia MJ, et al. (2000). Relationship of echocardiographic indices to pulmonary capillary wedge pressures in healthy volunteers. J Am Coll Cardiol 36:1664–1669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guzy RD, Schumacker PT. (2006). Oxygen sensing by mitochondria at complex III: The paradox of increased reactive oxygen species during hypoxia. Exp Physiol 91:807–819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heather LC, Cole MA, Tan JJ, et al. (2012). Metabolic adaptation to chronic hypoxia in cardiac mitochondria. Basic Res Cardiol 107:268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holloway CJ, Montgomery HE, Murray AJ, et al. (2011). Cardiac response to hypobaric hypoxia: Persistent changes in cardiac mass, function, and energy metabolism after a trek to Mt. Everest Base Camp. FASEB J 25:792–796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howald H, and Hoppeler H. (2003). Performing at extreme altitude: Muscle cellular and subcellular adaptations. Eur J Appl Physiol 90:360–364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudsmith LE, Petersen SE, Tyler DJ, et al. (2006). Determination of cardiac volumes and mass with FLASH and SSFP cine sequences at 1.5 vs. 3 Tesla: A validation study. J Magn Reson Imaging 24:312–318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karamitsos TD, Hudsmith LE, Selvanayagam JB, Neubauer S, and Francis JM. (2007). Operator induced variability in left ventricular measurements with cardiovascular magnetic resonance is improved after training. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 9:777–783 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kjaergaard J, Snyder EM, Hassager C, Olson TP, Oh JK, and Johnson BD. (2006). The effect of 18 h of simulated high altitude on left ventricular function. Eur J Appl Physiol 98:411–418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levett DZ, Fernandez BO, Riley HL, et al. (2011). The role of nitrogen oxides in human adaptation to hypoxia. Sci Rep 1:109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levett DZ, Martin DS, Wilson MH, et al. (2010). Design and conduct of Caudwell Xtreme Everest: An observational cohort study of variation in human adaptation to progressive environmental hypoxia. BMC Med Res Methodol 10:98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levett DZ, Radford EJ, Menassa DA, et al. (2012). Acclimatization of skeletal muscle mitochondria to high-altitude hypoxia during an ascent of Everest. FASEB J 26:1431–1441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizuno K, Tanaka M, Nozaki S, et al. (2008). Antifatigue effects of Coenzyme Q10 during physical fatigue. Nutrition 24:293–299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray AJ. (2009). Metabolic adaptation of skeletal muscle to high altitude hypoxia: How new technologies could resolve the controversies. Genome Med 1:117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray AJ. (2013). Of mice and men (and muscle mitochondria). Exp Physiol 98:879–880 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray AJ, Knight NS, Little SE, Cochlin LE, Clements M, and Clarke K. (2011). Dietary long-chain, but not medium-chain, triglycerides impair exercise performance and uncouple cardiac mitochondria in rats. Nutr Metab (Lond) 8:55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poon WW, Do TQ, Marbois BN, and Clarke CF. (1997). Sensitivity to treatment with polyunsaturated fatty acids is a general characteristic of the ubiquinone-deficient yeast coq mutants. Mol Aspects Med 18Suppl:S121–127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semenza GL. (2007). Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 (HIF-1) pathway. Sci STKE 2007:cm8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian R, Nascimben L, Ingwall JS, and Lorell BH. (1997). Failure to maintain a low ADP concentration impairs diastolic function in hypertrophied rat hearts. Circulation 96:1313–1319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyler DJ, Emmanuel Y, Cochlin LE, et al. (2009). Reproducibility of 31P cardiac magnetic resonance spectroscopy at 3 T. NMR Biomed 22:405–413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]