Abstract

Amniotic Fluid Stem (AFS) cells are broadly multipotent fetal stem cells derived from the positive selection and ex vivo expansion of amniotic fluid CD117/c-kitpos cells. Considering the differentiation potential in vitro toward cell lineages belonging to the three germ layers, AFS cells have raised great interest as a new therapeutic tool, but their immune properties still need to be assessed. We analyzed the in vitro immunological properties of AFS cells from different gestational age in coculture with T, B, and natural killer (NK) cells. Nonactivated (resting) first trimester-AFS cells showed lower expression of HLA class-I molecules and NK-activating ligands than second and third trimester-AFS cells, whose features were associated with lower sensitivity to NK cell-mediated lysis. Nevertheless, inflammatory priming with interferon gamma (IFN-γ) and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) enhanced resistance of all AFS cell types to NK cytotoxicity. AFS cells modulated lymphocyte proliferation in a different manner according to gestational age: first trimester-AFS cells significantly inhibited T and NK cell proliferation, while second and third trimester-AFS cells were less efficient. In addition, only inflammatory-primed second trimester-AFS cells could suppress B cell proliferation, which was not affected by the first and third trimester-AFS cells. Indolamine 2,3 dioxygenase pathway was significantly involved only in T cell suppression mediated by second and third trimester-AFS cells. Overall, this study shows a number of significant quantitative differences among AFS cells of different gestational age that have to be considered in view of their clinical application.

Introduction

Amniotic fluid is a rich stem cell (SC) source easily achievable through amniocentesis, during standard diagnostic procedure of prenatal care. Several authors have shown the presence of different SC subpopulations inside the amniotic fluid [1–3], but the isolation and characterization of CD117pos (c-kitpos) amniotic fluid stem (AFS) cells through immune selection is relatively recent [4,5]. We focused our attention on CD117pos AFS cells that represent a subpopulation of fetal SCs expressing the type III-tyrosine kinase receptor of the stem cell factor (c-kit), and are considered as excellent candidates for the SC based-approaches in regenerative medicine. AFS cells display some multipotent mesenchymal stromal cell (MSC) markers, such as CD73, CD90, and CD105 and some pluripotency-associated markers, such as Oct4 and NANOG and the stage-specific embryonic antigen (SSEA-4). Although AFS cells have been shown to differentiate in vitro toward cell lineages deriving from the three germ layers, including adipose, osteoblastic, myogenic, endothelial, neuronal, and hepatic cells, these properties were not unequivocally confirmed in vivo; moreover, AFS cells do not induce teratoma formation when injected into mice [4,6,7]. Both first and second trimester-derived AFS cells revert to a functional pluripotent state when cultured in small molecule cocktail, that is, chemically induced pluripotent stem cells [8,9]. Furthermore, AFS cells cross the endothelial barrier after systemic injection, thus engrafting into injured tissues [10–13].

The therapeutic efficacy of AFS cells has been recently verified in in vivo preclinical studies showing their capabilities to regenerate and improve the functionality of injured tissues and to restore cell niche homeostasis in muscle, bone, lung, and kidney [10,13–16]. In addition and similar to MSCs—an already thoroughly characterized immune regulatory cell type [17], AFS cells possess significant immune modulatory properties, as they may both suppress in vitro inflammatory responses, mainly through soluble factors [18], and modulate in vivo cellular immune response and distant organ damage during sublethal endotoxemia in animal models [19].

Our group has recently reported that AFS cells display similar immune modulatory properties than other SCs derived from different tissues, including MSCs, thus showing that immunomodulation is not a peculiar behavior of MSC-like cells, but is shared by different SC types [20]. Indeed, unselected MSCs from amniotic fluid have been shown to be a relatively homogeneous population of immature MSCs with long telomeres and immunosuppressive properties similar to their postnatal counterpart [21]. However, AFS cells can be collected at different gestational age and their phenotype and differentiation potential may vary accordingly. Recently, Moschidou et al. have performed a microarray-based transcriptome comparative gene profile analysis of first and second trimester-AFS cells and embryonic SCs, thus showing a more pronounced overlap between first trimester-AFS cells and embryonic SCs in cell-specific expression of pluripotency molecules, such as NANOG, SSEA-3, TRA-1-60, and TRA-1-81, and organ-specific genes [22]. Thus, we asked whether AFS immune modulatory properties could change along gestational age. To this aim, we used standardized approaches, previously applied to characterize MSCs and other SCs [20,23] and including immunophenotyping and assessment of immunogenicity and immunomodulatory functions toward T, B, and natural killer (NK) cells, to investigate the immunological profile of AFS cells isolated at different gestational age.

Materials and Methods

AFS cells

AFS cell samples were harvested after mother's informed consent through human amniocentesis carried out for diagnostic purposes (cytogenetic analysis) between 10th and 12th weeks of gestation (first trimester-AFS cells, four samples), between 16th and 18th weeks (second trimester-AFS cells, four samples) and during caesarian section at 37th–40th weeks (third trimester-AFS cells, five samples). The starting volumes of amniotic fluid were 0.1 mL for isolation of first trimester-AFS cells, and 1–2 mL for the isolation of second and third trimester-AFS cells. The collection of second and third trimester-AFS samples were approved by the Ethical Committee of Azienda Ospedaliera of Padua, Italy—protocol number 451P/32887, June 2002, “Stem cells isolation from left over samples of amniotic fluid”; first trimester-AFS cell collection was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Hammersmith & Queen Charlotte's Hospital (ref 2001/6234) “Characterisation, differentiation, transduction, engraftment and reparative potential of fetal mesenchymal stem cells.” Amniotic cells were seeded in culture, expanded, and processed by immunoselection, as previously reported [5]. Sorted c-kitpos AFS cells were cultured in α-MEM medium (Gibco) containing heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 U/mL penicillin, and 10 μg/mL streptomycin (all from Gibco), supplemented with 18% Chang B and 2% Chang C (Irvine Scientific) [4].

All AFS cells were harvested (0.05% Tripsin-EDTA; Gibco) when almost 80% confluent, and then either seeded at 103/cm2 cell concentration or frozen until use. All experiments were performed between passages 4 and 10.

Immunophenotyping

For inflammatory priming, AFS cells at 80% confluence were treated or not for 48 h with 10 ng/mL interferon gamma (IFN-γ) and 15 ng/mL tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) (R&D Systems) [20]. To assess the expression of different markers, resting and primed AFS cells were labeled with the following monoclonal antibodies: IgG1κ-PE, CD31-PE, CD34-PE, CD45-PE, CD73-PE, CD90-PE, CD105-PE, CD146-PE, CD107a-PE, CD54-PE, CD86-PE, CD106-PE, CD200-PE, and HLA-ABC-PE, all from BD Biosciences; IgG1κ-PE, CD80-PE, neuron-glial antigen 2 (NG2)-PE, IgG1κ-FITC, and HLA-DR-FITC (Beckman Coulter); IgG1κ-PE, CD112-PE, CD155-PE, IgG2b-PE, and CD274-PE all from Biolegend; IgG1-PE, IgG2a-PE, IgG2b-PE, unconjugated IgG2a, normal unconjugated goat IgG, MICA/B-PE, ULBP-1-PE, ULBP-2-PE, CCR7-PE, CXCR3, CXCR5, and unconjugated ULBP-3 (R&D Systems), IgG1-FITC and HLA-G from Exbio, IgG2aκ-PE, IgG1-PE, TLR-4-PE, and CD178-PE (FasL) from eBioscience, goat-anti-mouse-PE from Dako and donkey-anti-goat-PE from Abcam.

For staining, 105 AFS cells were incubated with the selected antibody or appropriate isotype control in phosphate-buffered saline for 15 min at room temperature. For ULBP-3 and Jagged-1 staining, PE-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG F(ab′)2 and PE-conjugated donkey F(ab′)2 polyclonal secondary antibodies were added, respectively. According to manufacturer's instruction, ULBP-1 expression was validated by intracellular staining using the Cytofix/Cytoperm kit (BD Biosciences). Data were analyzed by FACSCantoII (BD Biosciences) and expressed as ratio of relative mean fluorescence intensity (rMFI) obtained for each marker and its isotype-matched negative control.

Proliferation and survival assays

Immune effector cells (IECs), including CD3pos T cells, CD19pos B cells, and CD56pos NK cells were purified from peripheral blood using appropriate negative selection kits (Miltenyi Biotec), and cell purity (at least 95%) was assessed by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis.

To evaluate AFS cell immunomodulation of IEC proliferation, resting and primed AFS cells were cocultured with T, B, and NK cells at either 2×104 cell concentration (high ratio, corresponding to a confluent monolayer), or 2×103 cell concentration (low ratio), as previously shown [20,23]. We considered both AFS cell batch and IEC variability and we tested the immunomodulatory properties on a number of IEC donors to obtain consistent data. However, to minimize the variables, we followed standardized methods to select, activate and characterize IECs [20,23]. Following AFS cell adhesion, 2×105 T cells, 2×104 B cells, or 2×104 NK cells, previously stained with 1 μM carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester (CFSE; Life Technologies), were added to AFS cells. T cells were activated for 6 days with 0.5 μg/mL cross-linking anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 antibodies (Sanquin), in Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI) supplemented with 10% human AB serum. B cells were activated for 4 days with 2 μg/mL F(ab′)2 anti-human IgM/IgA/IgG (Jackson Immunoresearch), 20 IU/mL rhIL-2 (Proleukin; Novartis), 50 ng/mL polyhistidine-tagged CD40 ligand, 5 μg/mL anti-polyhistidine antibody (R&D Systems), and 2.5 μg/mL CpG B (Invivogen), in RPMI supplemented with 10% FBS (Invitrogen, Life Technologies). NK cells were activated for 6 days with 100 IU/mL rhIL-2 in Iscove modified Dulbecco medium supplemented with 10% human AB serum.

At the end of coculture, cells were harvested and labeled with PerCP-conjugated mouse anti-human CD45 monoclonal antibody (BD Biosciences) and TOPRO-3 Iodide (Invitrogen, Life Technologies); the percentage of proliferating cells was evaluated on viable TOPRO-3negCD45pos cells by FACS analysis as percentage of cells undergoing at least one cell division. The proliferation rate was obtained according to the following formula: (percentage of TOPRO-3negCD45pos cell proliferation with AFS cells)/(percentage of TOPRO-3negCD45pos cell proliferation without AFS cells)×100.

To understand which molecules were involved in immunomodulation, the following specific inhibitors were added to AFS/T cell cocultures: 1 mM L-N-monomethylarginin (LNMMA) to inhibit inducible NO synthase (iNOS); 5 μM NS-398 (Cayman Chemicals) to inhibit cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2, PGE2 synthesis inducing factor); 1 mM L-1-methyltryptophan (L-1MT) to inhibit indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) pathway (Sigma-Aldrich); 2 μM tin-protoporphyrin (SnPP) to inhibit HO-1 pathway (Frontier Scientific); and 10 μg/mL purified anti-human IFN-γ NA/LE mouse and IgG1 as control (BD Biosciences).

To determine the effect of AFS cells on IEC survival, resting and primed AFS cells were cocultured with IECs at the same concentrations described above for the immunomodulatory assays: 2×104 AFS cells (high ratio, corresponding to a confluent monolayer) or 2×103 AFS cells (low ratio), with 2×105 T cells, 2×104 B cells, or 2×104 NK cells. The analysis of IEC apoptosis was performed after either 4 days of coculture with B and NK cells, or 6 days of coculture with T cells; then, cells were detached with trypsin and stained with Allophycocyanin (APC)-conjugated mouse anti-human CD45 (BD Biosciences). IEC apoptosis quantification was assessed following manufacturer's instructions (PE active caspase-3 apoptosis kit; BD Biosciences); briefly, cells were fixed, permeabilized, and labeled with PE-anti-caspase-3 antibodies; cell apoptosis was assessed through FACS analysis as percentage of active-caspase-3negCD45pos viable cells.

Immunogenicity assay

AFS cell immunogenicity was assessed by using a non-radioactive cytotoxicity assay (Delfia Cytotoxicity kit; PerkinElmer), following manufacturer's instructions. NK cells were activated for 48 h with 100 IU/mL rhIL-2 and used as effector cells; AFS cells were then labeled with bis-acetoxymethyl terpyridine dicarboxylate (BATDA) fluorescent dye and used as target cells at different NK:AFS cell ratios (ranging from 1:1 to 50:1). After 3 h, cytotoxicity was quantified by assessing fluorescence release in coculture supernatants by a time-resolved fluorimeter (Victor™×4; PerkinElmer).

Statistical analysis

Data were expressed as mean±standard deviation, except for immunophenotype data that were expressed as mean±standard error. Statistical analysis was performed by Prism software (GraphPad) using the Wilcoxon test to compare the inflammatory priming effect on the same AFS cells, while one-way ANOVA test was used to assess the differences among AFS derived from different trimesters. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Morphologic and immunophenotypic differences among AFS cells

We compared first, second, and third trimester-AFS cells in terms of morphology and expression of typical stromal markers, by using the same experimental conditions and collecting the cells at the same culture passage. All the different AFS cell types showed their usual morphology ranging from fibroblast-like to oval-round shape (Fig. 1A), as described in literature [4,6]. We did not observe significant morphological differences, but a clear distinction was detected in terms of cell size: in particular, the forward scatter median of first trimester-AFS cells was significantly lower than that showed by second and third trimester-AFS cells, which displayed similar dimensions (Supplementary Fig. S1; Supplementary Data are available online at www.liebertpub.com/scd).

FIG. 1.

Heterogeneity of amniotic fluid stem (AFS) cells isolated at different gestational age. (A) Microscopy images showing morphologic features of the AFS cell types (the scale bar indicates 100 μm). Arrowheads show oval-round shaped cells. Images were obtained by Axiovert ObserverZ1, Zeiss. (B) Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis of AFS cells showing the expression profile of hematopoietic and mesenchymal stromal cell markers. The histograms display the isotopic controls (open curve) and specific markers (filled curve) in four (first and second trimester-AFS cells) and five (third trimester-AFS cells) different donors. The relative mean fluorescence intensity (rMFI)±SEM are reported in Table 1.

Immunophenotyping revealed some peculiarities along with gestational age (Table 1). In particular, CD31, and CD45 were undetectable in all AFS cell types, while CD34 was weakly expressed only by resting first trimester-AFS cells. As for mesenchymal markers, third trimester-AFS cells showed the higher espression of CD73, while all AFS cell types were brightly positive for CD90 and weakly positive for CD105. NG2 was highly, moderately, and poorly expressed by first, third, and second trimester-AFS cells, respectively. All AFS cell types expressed CD146, with higher intensity by third trimester-AFS cells (Fig. 1B).

Table 1.

Phenotypic Analysis of Amniotic Fluid Stem Cells Derived from Different Gestational Age

| First trimester | Second trimester | Third trimester | First trimester | Second trimester | Third trimester | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-MSC markers | Immunomodulatory molecules | ||||||

| CD31 | 1.0±0 | 1.0±0 | 1.0±0 | CD200 | 1.0±0 | 2.2±0.9 | 1.1±0.3 |

| 1.0±0 | 1.0±0 | 1.0±0 | 1.0±0 | 1.6±0.3 | 1.0±0 | ||

| CD34 | 1.6±0.4 | 1.1±0.1 | 1.1±0.1 | CD274 (PD-L1) | 13.8±3.7 | 24.8±5.5 | 26.5±6.6 |

| 1.1±0.1 | 1.1±0.1 | 1.0±0 | 56.0±7.2 | 75.8±19.2 | 86.5±13.8 | ||

| CD45 | 1.0±0 | 1.0±0 | 1.0±0 | NKG2D ligands | |||

| 1.0±0 | 1.0±0 | 1.0±0 | ULBP-1 | 3.6±0.2 | 1.2±0.1 | 1.4±0.1 | |

| MSC markers | 3.6±0.1 | 1.3±0.1 | 1.6±0.2 | ||||

| CD73 | 41.0±5.9 | 37.5±10.0 | 86.6±30.0 | ULBP-2 | 2.6±0.2 | 1.7±0.2 | 3.3±0.5 |

| 43.3±8.5 | 35.0±8.4 | 86.1±25.5 | 2.0±0.4 | 1.6±0.3 | 2.0±0.2 | ||

| CD90 | 339.0±92.0 | 95.0±69.4 | 328.3±71.3 | ULBP-3 | 1.8±0.7 | 1.2±0.1 | 1.84±0.6 |

| 277.5±138.3 | 134.3±100.5 | 247.8±45.4 | 1.3±0.3 | 2.1±0.7 | 1.8±0.6 | ||

| CD105 | 4.0±0.5 | 2.8±0.4 | 4.1±1.0 | MICA/B | 2.7±0.9 | 2.3±0.7 | 3.6±0.1 |

| 2.3±0.1 | 2.9±0.5 | 3.1±0.4 | 1.6±0.2 | 1.7±0.4 | 2.5±0.9 | ||

| MHC molecules | DNAM ligands | ||||||

| HLA-ABC | 4.2±0.6 | 7.9±1.1 | 12.0±2.7 | CD112 | 18.1±2.2 | 19.1±2.6 | 23.6±2.5 |

| 7.8±1.8 | 17.7±2.2 | 25.9±4.6 | 18.3±1.9 | 27.2±4.5 | 36.4±8.4 | ||

| HLA-DR | 1.0±0 | 1.1±0 | 1.0±0 | CD155 | 26.3±5.1 | 86.3±17.5 | 95.6±19.0 |

| 3.1±1.2 | 2.3±1.1 | 3.7±1.1 | 38.3±9.6 | 107.0±7.2 | 135.0±34.8 | ||

| Costimulatory molecules | Other molecules | ||||||

| CD40 | 1.1±0.1 | 2.9±0.2 | 1.9±0.2 | NG2 | 26.1±12.1 | 3.5±0.6 | 7.3±1.3 |

| 1.1±0.1 | 3.0±0.5 | 2.9±0.5 | 17.4±6.1 | 12.0±9.2 | 12.0±6.5 | ||

| CD80 | 1.2±0.1 | 1.0±0 | 1.0±0 | CD119 | 2.6±0.4 | 2.9±1.2 | 4.6±0.4 |

| 1.0±0 | 1.0±0 | 1.0±0 | 1.6±0.1 | 2.4±0.3 | 3.2±0.4 | ||

| CD86 | 1.1±0.1 | 1.1±0 | 1.4±0.2 | TLR-4 | 1.1±0 | 2.3±0.8 | 2.5±0.3 |

| 1.0±0 | 1.1±0.1 | 1.1±0 | 1.4±0.2 | 2.4±0.7 | 2.1±0.1 | ||

| Adhesion molecules | |||||||

| CD54 | 23.4±10.2 | 25.5±8.9 | 11.1±4.6 | ||||

| 519.9±57.0 | 582.7±52.6 | 728.4±17.9 | |||||

| CD106 | 1.5±0.5 | 2.1±0.3 | 1.4±0.3 | ||||

| 3.3±0.5 | 28.4±8.7 | 17.1±7.6 | |||||

| CD146 | 22.1±3.4 | 27.3±2 | 57.9±14.4 | ||||

| 16.8±3.9 | 22.2±1.4 | 30.7±5.2 | |||||

Resting and inflammatory-primed AFS cells were cultured in presence or not of IFN-γ and TNF-α for 48 h. AFS cells were then harvested and labeled with different antibodies (as reported in Materials and Methods section). The expression of HLA-G, CXCR3, CCR7, CXCR5, CD107a, and Jagged-1 was also evaluated, but rMFI was not significant as compared to control. Data are shown as rMFI±SEM of four (first and second trimester-AFS cells) or five (third trimester-AFS cells) experiments derived from resting (upper) and inflammatory-primed (below, bold) cells for each marker.

AFS, amniotic fluid stem; DNAM, DNAX accessory molecule; IFN-γ, interferon gamma; MSC, mesenchymal stromal cell; rMFI, relative mean fluorescence intensity; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor alpha.

Effect of inflammatory priming on AFS cells

The immunomodulatory assays, with either resting or inflammatory-primed AFS cells from different gestational age, were carried out in parallel with immunophenotyping to evaluate the expression of different molecules involved in MSC immunomodulation (Table 1 and Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Expression of specific markers involved in immunomodulation. AFS cells were cultured with or without inflammatory priming; after 48 h, the expression of CD40, CD80, CD86, HLA-ABC, HLA-DR, CD274, CD54, and CD106 was evaluated by FACS analysis. The results are expressed as rMFI±SEM of four (first and second trimester-AFS cells) or five (third trimester-AFS cells) independent experiments. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001.

First, we studied a panel of molecules involved in antigen presentation and costimulation of IECs. HLA-ABC expression by first trimester-AFS cells not only was significantly lower at resting conditions (P<0.05), but also raised less remarkably following inflammatory priming (1.87-, 2.23-, and 2.15-fold in first, second, and third trimester-AFS cells, respectively; P<0.05). HLA-DR was not detectable at resting conditions, but following inflammatory priming a variable expression of this molecule was induced in all the AFS cell types. CD80 and CD86 costimulatory molecules were undetectable, regardless of culture conditions. By contrast, only in second and third trimester-AFS cells CD40 expression was evident at resting conditions and weakly inducible by inflammatory priming (Fig. 2).

Then, we tested the expression of a number of adhesion molecules that are involved in different physiological mechanisms, such as migration, tethering with IECs, and modulation of inflammatory responses [24]. At resting conditions, CD54 was constitutively expressed by all AFS cell types. Following inflammatory priming, CD54 was variably upregulated in first (22.17-fold), second (11.53-fold), and third (65.62-fold) trimester-AFS cells. CD106 was undetectable at resting conditions in all AFS cell types, but was inducible by inflammatory cytokines only in second and third, but not in first trimester-AFS cells (Fig. 2).

Finally, we assessed the expression of two immunosuppressive molecules, CD274 (PD-L1) and CD200 (OX-2), which are involved in the modulation of T cell proliferation [25–27]. CD274 was expressed by all AFS cells at resting conditions, but variably upregulated by inflammatory priming (4.04-fold in first trimester, 3.06-fold in second trimester, and 3.2-fold in third trimester, respectively) (Fig. 2). Conversely, CD200 was detectable only in second trimester AFS cells, and inflammatory priming did not modify its expression (Table 1).

The analysis of other markers, including cytokine and chemokine receptors, Toll-like receptors, HLA-G, CD107a, Jagged-1, and NK cell-activating receptors did not show significant differences in the three AFS cell types, with the exception of CD155 (and partially CD112, both NK cell-activating DNAM-1 ligands) that resulted progressively expressed and further inducible by inflammatory priming along gestational age (Table 1).

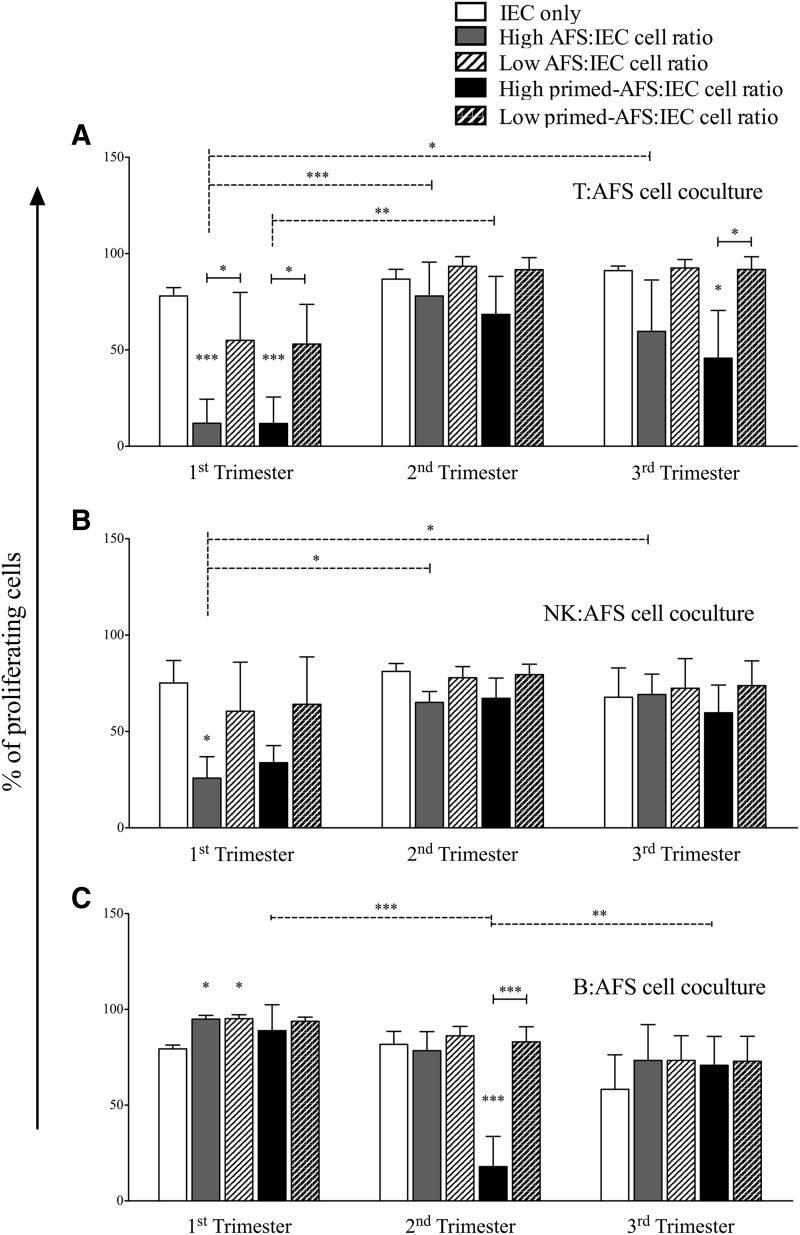

We then assessed the immunomodulatory properties of AFS cells toward different IECs. To this purpose, resting and inflammatory-primed AFS cells were cocultured at different ratios with purified T, B, and NK cells, in presence or not of specific stimuli. None of the AFS cell types induced the activation of unstimulated IECs (Supplementary Fig. S2), in agreement with the lack of expression of HLA class II and co-stimulatory molecules. AFS cells did not show modulatory effects on IECs at low ratio (100:1 for T cells, and 10:1 for B and NK cells, respectively), except for first trimester-AFS cells that displayed a nonstatistically significant trend of inhibition toward T and NK cell, but not B cell, proliferation (Fig. 3). Conversely, at high ratio (10:1 for T cells, and 1:1 for B and NK cells) AFS cell types exerted a variable degree of inhibition toward stimulated IECs. In fact, while both resting and primed first trimester-AFS cells strongly inhibited T cell (Fig. 3A) and NK cell (Fig. 3B) proliferation, only primed third trimester-AFS cells significantly inhibited T cell proliferation (Fig. 3A), and only primed second trimester-AFS cells inhibited B cell proliferation (Fig. 3C). By contrast, all AFS cell types at resting conditions supported, rather than suppress, B cell proliferation (Fig. 3C); this effect is probably related to the lack of IFN-γ release, the main cytokine involved in MSC activation, by B cells [28].

FIG. 3.

Immunomodulatory effect of different AFS cells on immune effector cell (IEC) proliferation. Carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester (CFSE)-labeled IECs, activated by specific stimuli, were cultured alone or in presence of resting and primed AFS cells. All experiments were carried out at high and low IEC:AFS cell ratios, that is 10:1 (corresponding to 2×105 IECs and 2×104 AFS cells) and 100:1 (corresponding to 2×105 T cells and 2×103 AFS cells) for T cells (A), and 1:1 (corresponding to 2×104 IECs and 2×104 AFS cells) and 10:1 (corresponding to 2×104 IECs and 2×103 AFS cells) for natural killer (NK) (B) and B cells (C). Data are represented as IEC proliferation percentage, corresponding to the mean±SD of CD45pos TOPRO-3neg cell proliferation derived from four independent experiments. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001.

Molecular mechanisms involved in T cell immunomodulation

We explored the molecular mechanisms underlying the immunosuppressive effect of AFS cells on T cell proliferation. To this aim, we inhibited the function of IDO, iNOS, COX-2, HO-1, and IFN-γ using specific inhibitors and neutralizing anti-IFN-γ antibody, respectively. All inhibitors were previously tested on MSCs at concentrations that do not alter T cell viability and proliferation [20,23].

The crucial role of IDO on T cell inhibition was largely shown by different groups [29,30]. When added to T cell cocultures with both resting and primed second and third trimester-AFS cells, L-1MT led to a complete rescue of T cell proliferation (Fig. 4). Quite surprisingly, first trimester-AFS cells did not exhibit IDO activity, regardless of the strong inhibitory effect toward T cell proliferation (Fig. 3A). Indeed, first trimester-AFS cells could induce T cell apoptosis, as shown by the decrease at the end of AFS/T cocultures of viable (TOPRO-3neg CD45pos) cells, which instead did not change in presence of second and third trimester-AFS cells (Supplementary Fig. S3A). However, apoptotic mechanism does not rely on Fas ligand (FasL), as none of the AFS cell types displayed detectable levels of this molecule either at resting conditions or following inflammatory priming (Supplementary Fig. S3B).

FIG. 4.

Role of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) on T cell inhibition. CFSE-labeled T cells, stimulated with anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 monoclonal antibodies, were cultured alone or in presence of resting or primed AFS cells. L-1-methyltryptophan (L-1MT), the specific inhibitor of IDO was added to cocultures to evaluate the involvement of IDO on AFS-mediated immunosuppression. At the end of coculture (6 days), cell proliferation was analyzed by FACS. Graphs represent the dot plots of CFSE fluorescence (log scale) and proliferation was evaluated as percentage of T cells undergoing at least one cell division. Each box represents the mean±SD of proliferating CD45pos TOPRO-3neg cells derived from four independent experiments. *P<0.05, **P<0.01.

When IFN-γ was specifically blocked, only a partially rescue of T cell proliferation was observed, while LNMMA, NS-398, and snPP did not hamper AFS cell-mediated T cell suppression (Supplementary Fig. S4).

Inflammatory-primed AFS cells are refractory to NK cytotoxicity

With the aim to assess whether AFS cells are susceptible to NK cell-mediated lysis, BATDA-labeled AFS cells were used as target cells and cultured in presence of interleukin-2 (IL-2) prestimulated NK cells at different NK:AFS ratios, which ranged from 1:1 to 50:1 (Fig. 5A). As expected, resting AFS cells were sensitive to NK cell-mediated lysis in a dose-dependent manner. Nevertheless, all AFS cell types acquired resistance to NK cells following inflammatory priming. We therefore assessed whether these results were related to the different expression of NK cell-activating ligands on primed AFS cell surface (Table 1 and Fig. 5B), as compared to resting conditions. To this aim, we tested the expression of Nectin-2 (CD112) and Poliovirus receptor (PVR, CD155), which bind the NK cell-activating DNAX accessory molecule-1 (DNAM-1), and the MHC class I-related A and B molecule (MICA/B) and UL16-binding proteins (ULBPs), which instead interact with NK cell-activating NKG2D receptor. CD112 and CD155 were constitutively expressed in all AFS cells. At resting conditions, CD112 was higher in third trimester-AFS cells and was upregulated after inflammatory priming in all AFS cell types but first trimester-AFS cells (Fig. 5B). At resting conditions, CD155 was expressed strongly by second and third trimester-AFS cells and modestly by first trimester-AFS cells; however a strong upregulation was observed following inflammatory priming in all AFS cell types (Fig. 5B). No significant expression of ULBPs and MICA/B, in terms of mean fluorescence intensity, was detected in any AFS cell type either at resting conditions or following inflammatory priming (Fig. 5B).

FIG. 5.

Inflammatory microenvironment reduces AFS sensitivity to NK cell-mediated lysis. (A) Interleukin-2 (IL-2)-activated NK cells were cocultured in the presence of bis-acetoxymethyl terpyridine dicarboxylate (BATDA)-labeled AFS cells at different ratios. The cytotoxic effect on resting and inflammatory-primed AFS cells was expressed as release of fluorescence by lysed cells and quantified by time-resolved fluorimeter (Victor×4 Multilabel Plate Reader; PerkinElmer). Data are showed as percentage of fluorescence release. Error bars represent the mean±SD of four (first trimester-AFS cells) or five (second and third trimester-AFS cells) experiments. As internal control, we measured spontaneous and maximum release of BATDA and then normalized the values. (B) AFS cells were cultured in presence or not of inflammatory cytokines. At day 2 the expression of CD112, CD155, MHC class I-related A and B molecule (MICA/B), UL16-binding proteins (ULBPs) was analyzed by FACS. The results are expressed as rMFI±SEM of four (first and second trimester-AFS cells) or five (third trimester-AFS cells) different experiments. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001.

Regardless NK cell-activating ligand expression, second and third trimester-AFS cells were resistant to NK cell cytotoxicity. It has been widely demonstrated that the overexpression of HLA class I, which is the crucial NK inhibitory ligand, prevail over NK activating ligands, thus eventually preventing NK cell-mediated cytotoxicity [31]. Interestingly, first trimester-AFS cells did not show a significant increase of HLA-ABC expression following inflammatory priming (Fig. 2). Moreover, they displayed a weak expression of ULBP-1 and ULBP-2 both at resting and primed conditions (Fig. 5B). The lack of HLA-ABC overexpression by first trimester-AFS cells paralleled their lower capability to become resistant to NK cell-mediated cytotoxicity, compared with the other AFS cell types (Fig. 5A).

Antiapoptotic effect of AFS cells on resting IECs

A number of SC types, including AFS cells, may favor the survival of unstimulated IECs [20,32]. To verify whether AFS cells retain their supportive effect along gestational age, resting, and inflammatory primed AFS cells were cocultured in presence of unstimulated IECs at different ratios, and IEC viability (as percentage of caspase-3neg CD45pos cells) was assessed at the end of coculture. T cell survival was not significantly enhanced by AFS cells of any gestational age, both at resting and primed conditions (Fig. 6A). By contrast, a significant improvement of NK cell survival was evident only in cocultures with second and third trimester-AFS cells, while B cells were rescued by all AFS cell types regardless of their resting or primed status (Fig. 6B, C).

FIG. 6.

Antiapoptotic effect of AFS cells on resting IECs. Resting and inflammatory-primed AFS cells were cultured in presence of unstimulated IECs at different ratios, that is 10:1 (corresponding to 2×105 IECs and 2×104 AFS cells) and 100:1 (corresponding to 2×105 T cells and 2×103 AFS cells) for T cells (A), and 1:1 (corresponding to 2×104 IECs and 2×104 AFS cells) and 10:1 (corresponding to 2×104 IECs and 2×103 AFS cells) for NK (B) and B cells (C). At the end of coculture (4 days for NK and B cells, and 6 days for T cells) cells were harvested and labeled with anti-CD45 and anti-cytoplasmic active-caspase-3 antibodies to evaluate the percentage of apoptotic IECs by FACS analysis. Data are expressed as percentage of caspase-3neg CD45pos cells. Error bars represent the mean±SD of four different experiments for each (first, second and third trimester) AFS cell types. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001.

Discussion

SC based-approaches are promising tools for the treatment of different human degenerative, inflammatory, and autoimmune diseases. There are several reports regarding the beneficial roles of the immunomodulatory effects of different adult SC types, mainly MSCs, in different disease models such as graft-versus-host disease [33], experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis [34], inflammatory bowel disease [35], and systemic lupus erythematosus [36]. The safety and efficacy of MSC treatments have been validated in clinical trials [37–40] and many others are currently in progress. In addition, several SC types of fetal origin have been identified as possible candidates to novel therapeutic approaches.

Fetal MSCs can be isolated from different gestational tissues, such as umbilical cord lining and blood [41], Wharton's Jelly [42], amniotic fluid [4], and amnion and chorion layers [43]. Among them, c-kitpos AFS cells resulted as broadly multipotent SCs with intermediate features between embryonic SCs and MSCs, as they are capable of differentiating in vitro into cells of the three germ layers [4] and forming embryoid bodies [44]. In addition, AFS cells display a number of differences compared with adult, embryonic or induced pluripotent SCs: (i) AFS cell collection is carried out through amniocentesis, which is a standard diagnostic procedure of prenatal care. (ii) AFS cells have greater expansion capacity in vitro than adult SCs and maintain a constant telomere length between early and late passages [4,44]. (iii) AFS cells do not form tumors when injected into severe combined immunodeficient (SCID) mice [4,8,45]. (iv) AFS cells possess significant immunomodulatory properties both in vitro [18] and in vivo [19], thus suggesting that AFS could be successfully used as immunomodulatory cell therapy in inflammatory and autoimmune diseases, similar to MSCs, as long as a further characterization of their immune properties is carried out.

As AFS cells can be collected at different gestational age and their phenotype and differentiation status seem to depend on fetal development, our study compared for the first time the immunological properties of AFS cells of different gestational age. So far, only gene expression comparative studies between first and second trimester-AFS cells are available, showing that cKit+ first trimester-AFS cells belong to the most undifferentiated portion of amniotic fluid cells displaying pluripotency molecules, such as NANOG, SSEA-3, TRA-1-60, and TRA-1-81, and higher expression of organ-specific genes [22]. Accordingly, we found that first trimester-AFS cells express NG2 and CD34, two molecules normally expressed by undifferentiated SC subsets and embryonic SC-derived MSCs with enhanced self-renewal, higher colony forming unit efficiency, and long-term proliferative capacity [46,47].

In addition, our data highlighted specific peculiarities of the first trimester-AFS cells in terms of immunological phenotype, supportive effects toward unstimulated IECs, response to IFN-γ- and TNF-α-mediated inflammatory priming, immunomodulatory capacity toward activated IECs, and intracellular mechanisms involved in these effects.

In fact, first trimester-AFS cells resulted to be poor antigen-presenting cells (HLA-ABClow, HLA-DRneg, CD80neg, CD86neg, and CD40neg), both at resting and primed conditions, with a partial expression of adhesion (CD54pos and CD106low, only after inflammatory priming) and inhibitory molecules (CD274pos and CD200neg, only after inflammatory priming). By contrast, second and third trimester-AFS cells shared, at resting conditions, a very similar surface antigen-presenting cell-like pattern (HLA-ABCpos, HLA-DRneg, CD80neg, CD86neg, and CD40pos), further enhanced by inflammatory priming that led also to the increase of adhesion (CD54pos and CD106pos) and inhibitory molecules (CD274pos and CD200pos, the latter only in second trimester-AFS cells). The immunophenotypic pattern parallels with the expression of some NK cell-activating ligands (CD155 and CD112), which resulted progressively expressed and further inducible by inflammatory priming along gestational age. Although the inflammatory priming-dependent loss of sensitivity to NK cell lysis was more evident in second and third trimester-AFS cells and probably associated to the stronger upregulation of HLA-ABC, as previously described for MSCs [31], it also occurred in first trimester-AFS cells, regardless of their weak expression of ULBPs and MICA/B that are the main activating ligands of NK cells. Thus, it is likely that other mechanisms are involved in first trimester-AFS cell resistance to NK cell-mediated lysis.

Finally, while second and third trimester-AFS cells at resting and primed conditions enhanced the viability of unstimulated NK, B, and—less—T cells, first trimester-AFS cells only increased the survival of B cells, being less efficient in rescuing unstimulated T and NK cells from apoptosis. Nevertheless, none of the AFS cell types induced the activation of unstimulated IECs, in agreement with the lack of expression of HLA class II and costimulatory molecules. Other gestational age-related differences concerned also the immunosuppression mechanisms: the strong inhibitory effect on activated T cell proliferation by first trimester-AFS cells, both at resting and primed conditions, was related to their capability of inducing T cell death through a FasL-independent mechanism, rather than to IDO-pathway activation; the latter was instead the typical inhibitory pathway in second and third trimester-AFS cells, similar to MSCs [20,28,29]. In addition, only resting and primed first trimester-AFS cells strongly inhibited NK cell proliferation, while only primed second trimester-AFS cells inhibited B cell proliferation.

In summary, first trimester-AFS cells present some peculiar mechanisms of immune regulation that could be related to an early embryonic stage, while second and third trimester-AFS cells share many of the adult MSC immunomodulatory features. In addition, our data further confirm the pivotal role of IFN-γ- and TNF-α-mediated inflammatory priming for the acquisition of the immunomodulatory profile by AFS cells of different gestational age, as previously shown by our group in MSCs and SCs of different origin [20].

The immunomodulatory properties observed in this study, particularly in first trimester-AFS cells, could have a synergic effect with their broad differentiation potential in favoring injured tissue regeneration, by directly regulating the inflammatory microenvironment or through the release of trophic and immunomodulatory molecules playing a fundamental role in tissue homeostasis. Therefore, further understanding of these mechanisms could help to identify novel therapeutic approaches for the treatment of inflammatory diseases.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from CARIVERONA, Bando 2013–2015; 7th Framework Program of the European Commission: CASCADE (FP7-HEALTH-233236), and REBORNE (FP7-HEALTH-241879); Fondazione Istituto di Ricerca Pediatrica Città della Speranza Project number: 12/01; Great Ormond Street Hospital Children's Charity. The authors would also like to thank Dr. Eric Cosmi and Dr. Silvia Visentin, Department of Woman and Child Health, University of Padova, who kindly provided the samples of AFS from II trimester. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the article.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Prusa AR, Marton E, Rosner M, Bernaschek G. and Hengstschlager M. (2003). Oct-4-expressing cells in human amniotic fluid: a new source for stem cell research?. Hum Reprod 18:1489–1493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Karlmark KR, Freilinger A, Marton E, Rosner M, Lubec G. and Hengstschlager M. (2005). Activation of ectopic Oct-4 and Rex-1 promoters in human amniotic fluid cells. Int J Mol Med 16:987–992 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tsai MS, Hwang SM, Tsai YL, Cheng FC, Lee JL. and Chang YJ. (2006). Clonal amniotic fluid-derived stem cells express characteristics of both mesenchymal and neural stem cells. Biol Reprod 74:545–551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.De Coppi P, Bartsch G, Jr., Siddiqui MM, Xu T, Santos CC, Perin L, Mostoslavsky G, Serre AC, Snyder EY, et al. (2007). Isolation of amniotic stem cell lines with potential for therapy. Nat Biotechnol 25:100–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pozzobon M, Piccoli M, Schiavo AA, Atala A. and De Coppi P. (2013). Isolation of c-Kit+ human amniotic fluid stem cells from second trimester. Methods Mol Biol 1035:191–198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cananzi M. and De Coppi P. (2012). CD117(+) amniotic fluid stem cells: state of the art and future perspectives. Organogenesis 8:77–88 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sedrakyan S, Da Sacco S, Milanesi A, Shiri L, Petrosyan A, Varimezova R, Warburton D, Lemley KV, De Filippo RE. and Perin L. (2012). Injection of amniotic fluid stem cells delays progression of renal fibrosis. J Am Soc Nephrol 23:661–673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moschidou D, Mukherjee S, Blundell MP, Drews K, Jones GN, Abdulrazzak H, Nowakowska B, Phoolchund A, Lay K, et al. (2012). Valproic acid confers functional pluripotency to human amniotic fluid stem cells in a transgene-free approach. Mol Ther 20:1953–1967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moschidou D, Mukherjee S, Blundell MP, Jones GN, Atala AJ, Thrasher AJ, Fisk NM, De Coppi P. and Guillot PV. (2013). Human mid-trimester amniotic fluid stem cells cultured under embryonic stem cell conditions with valproic acid acquire pluripotent characteristics. Stem Cells Dev 22:444–458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carraro G, Perin L, Sedrakyan S, Giuliani S, Tiozzo C, Lee J, Turcatel G, De Langhe SP, Driscoll B, et al. (2008). Human amniotic fluid stem cells can integrate and differentiate into epithelial lung lineages. Stem Cells 26:2902–2911 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ghionzoli M, Cananzi M, Zani A, Rossi CA, Leon FF, Pierro A, Eaton S. and De Coppi P. (2010). Amniotic fluid stem cell migration after intraperitoneal injection in pup rats: implication for therapy. Pediatr Surg Int 26:79–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bollini S, Pozzobon M, Nobles M, Riegler J, Dong X, Piccoli M, Chiavegato A, Price AN, Ghionzoli M, et al. (2011). In vitro and in vivo cardiomyogenic differentiation of amniotic fluid stem cells. Stem Cell Rev 7:364–380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Piccoli M, Franzin C, Bertin E, Urbani L, Blaauw B, Repele A, Taschin E, Cenedese A, Zanon GF, et al. (2012). Amniotic fluid stem cells restore the muscle cell niche in a HSA-Cre, Smn(F7/F7) mouse model. Stem Cells 30:1675–1684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Riccio M, Maraldi T, Pisciotta A, La Sala GB, Ferrari A, Bruzzesi G, Motta A, Migliaresi C. and De Pol A. (2012). Fibroin scaffold repairs critical-size bone defects in vivo supported by human amniotic fluid and dental pulp stem cells. Tissue Eng Part A 18:1006–1013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rodrigues MT, Lee BK, Lee SJ, Gomes ME, Reis RL, Atala A. and Yoo JJ. (2012). The effect of differentiation stage of amniotic fluid stem cells on bone regeneration. Biomaterials 33:6069–6078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rota C, Imberti B, Pozzobon M, Piccoli M, De Coppi P, Atala A, Gagliardini E, Xinaris C, Benedetti V, et al. (2012). Human amniotic fluid stem cell preconditioning improves their regenerative potential. Stem Cells Dev 21:1911–1923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Krampera M. (2011). Mesenchymal stromal cell ‘licensing’: a multistep process. Leukemia 25:1408–1414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moorefield EC, McKee EE, Solchaga L, Orlando G, Yoo JJ, Walker S, Furth ME. and Bishop CE. (2011). Cloned, CD117 selected human amniotic fluid stem cells are capable of modulating the immune response. PLoS One 6:e26535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gosemann JH, Kuebler JF, Pozzobon M, Neunaber C, Hensel JH, Ghionzoli M, de Coppi P, Ure BM. and Holze G. (2012). Activation of regulatory T cells during inflammatory response is not an exclusive property of stem cells. PLoS One 7:e35512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Di Trapani M, Bassi G, Ricciardi M, Fontana E, Bifari F, Pacelli L, Giacomello L, Pozzobon M, Feron F, et al. (2013). Comparative study of immune regulatory properties of stem cells derived from different tissues. Stem Cells Dev 22:2990–3002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sessarego N, Parodi A, Podesta M, Benvenuto F, Mogni M, Raviolo V, Lituania M, Kunkl A, Ferlazzo G, et al. (2008). Multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells from amniotic fluid: solid perspectives for clinical application. Haematologica 93:339–346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moschidou D, Drews K, Eddaoudi A, Adjaye J, De Coppi P. and Guillot PV. (2013). Molecular signature of human amniotic fluid stem cells during fetal development. Curr Stem Cell Res Ther 8:73–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Menard C, Pacelli L, Bassi G, Dulong J, Bifari F, Bezier I, Zanoncello J, Ricciardi M, Latour M, et al. (2013). Clinical-grade mesenchymal stromal cells produced under various good manufacturing practice processes differ in their immunomodulatory properties: standardization of immune quality controls. Stem Cells Dev 22:1789–1801 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ren G, Zhao X, Zhang L, Zhang J, L'Huillier A, Ling W, Roberts AI, Le AD, Shi S, Shao C. and Shi Y. (2010). Inflammatory cytokine-induced intercellular adhesion molecule-1 and vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 in mesenchymal stem cells are critical for immunosuppression. J Immunol 184:2321–2328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Augello A, Tasso R, Negrini SM, Amateis A, Indiveri F, Cancedda R. and Pennesi G. (2005). Bone marrow mesenchymal progenitor cells inhibit lymphocyte proliferation by activation of the programmed death 1 pathway. Eur J Immunol 35:1482–1490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Luz-Crawford P, Noel D, Fernandez X, Khoury M, Figueroa F, Carrion F, Jorgensen C. and Djouad F. (2012). Mesenchymal stem cells repress Th17 molecular program through the PD-1 pathway. PLoS One 7:e45272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Najar M, Raicevic G, Kazan HF, De Bruyn C, Bron D, Toungouz M. and Lagneaux L. (2012). Immune-related antigens, surface molecules and regulatory factors in human-derived mesenchymal stromal cells: the expression and impact of inflammatory priming. Stem Cell Rev 8:1188–1198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Krampera M, Cosmi L, Angeli R, Pasini A, Liotta F, Andreini A, Santarlasci V, Mazzinghi B, Pizzolo G, et al. (2006). Role for interferon-gamma in the immunomodulatory activity of human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells 24:386–398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Meisel R, Zibert A, Laryea M, Gobel U, Daubener W. and Dilloo D. (2004). Human bone marrow stromal cells inhibit allogeneic T-cell responses by indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase-mediated tryptophan degradation. Blood 103:4619–4621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Su J, Chen X, Huang Y, Li W, Li J, Cao K, Cao G, Zhang L, Li F, et al. (2014). Phylogenetic distinction of iNOS and IDO function in mesenchymal stem cell-mediated immunosuppression in mammalian species. Cell Death Differ 21:388–396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Spaggiari GM, Capobianco A, Becchetti S, Mingari MC. and Moretta L. (2006). Mesenchymal stem cell-natural killer cell interactions: evidence that activated NK cells are capable of killing MSCs, whereas MSCs can inhibit IL-2-induced NK-cell proliferation. Blood 107:1484–1490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Benvenuto F, Ferrari S, Gerdoni E, Gualandi F, Frassoni F, Pistoia V, Mancardi G. and Uccelli A. (2007). Human mesenchymal stem cells promote survival of T cells in a quiescent state. Stem Cells 25:1753–1760 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Polchert D, Sobinsky J, Douglas G, Kidd M, Moadsiri A, Reina E, Genrich K, Mehrotra S, Setty S, Smith B. and Bartholomew A. (2008). IFN-gamma activation of mesenchymal stem cells for treatment and prevention of graft versus host disease. Eur J Immunol 38:1745–1755 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rafei M, Birman E, Forner K. and Galipeau J. (2009). Allogeneic mesenchymal stem cells for treatment of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Mol Ther 17:1799–1803 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gonzalez MA, Gonzalez-Rey E, Rico L, Buscher D. and Delgado M. (2009). Adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells alleviate experimental colitis by inhibiting inflammatory and autoimmune responses. Gastroenterology 136:978–989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sun L, Akiyama K, Zhang H, Yamaza T, Hou Y, Zhao S, Xu T, Le A. and Shi S. (2009). Mesenchymal stem cell transplantation reverses multiorgan dysfunction in systemic lupus erythematosus mice and humans. Stem Cells 27:1421–1432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ball LM, Bernardo ME, Roelofs H, Lankester A, Cometa A, Egeler RM, Locatelli F. and Fibbe WE. (2007). Cotransplantation of ex vivo expanded mesenchymal stem cells accelerates lymphocyte recovery and may reduce the risk of graft failure in haploidentical hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation. Blood 110:2764–2767 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Le Blanc K, Frassoni F, Ball L, Locatelli F, Roelofs H, Lewis I, Lanino E, Sundberg B, Bernardo ME, et al. (2008). Mesenchymal stem cells for treatment of steroid-resistant, severe, acute graft-versus-host disease: a phase II study. Lancet 371:1579–1586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Duijvestein M, Vos AC, Roelofs H, Wildenberg ME, Wendrich BB, Verspaget HW, Kooy-Winkelaar EM, Koning F, Zwaginga JJ, et al. (2010). Autologous bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stromal cell treatment for refractory luminal Crohn's disease: results of a phase I study. Gut 59:1662–1669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ciccocioppo R, Bernardo ME, Sgarella A, Maccario R, Avanzini MA, Ubezio C, Minelli A, Alvisi C, Vanoli A, et al. (2011). Autologous bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stromal cells in the treatment of fistulising Crohn's disease. Gut 60:788–798 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stubbendorff M, Deuse T, Hua X, Phan TT, Bieback K, Atkinson K, Eiermann TH, Velden J, Schroder C, et al. (2013). Immunological properties of extraembryonic human mesenchymal stromal cells derived from gestational tissue. Stem Cells Dev 22:2619–2629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Weiss ML, Anderson C, Medicetty S, Seshareddy KB, Weiss RJ, VanderWerff I, Troyer D. and McIntosh KR. (2008). Immune properties of human umbilical cord Wharton's jelly-derived cells. Stem Cells 26:2865–2874 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yamahara K, Harada K, Ohshima M, Ishikane S, Ohnishi S, Tsuda H, Otani K, Taguchi A, Soma T, et al. (2014). Comparison of angiogenic, cytoprotective, and immunosuppressive properties of human amnion- and chorion-derived mesenchymal stem cells. PLoS One 9:e88319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Valli A, Rosner M, Fuchs C, Siegel N, Bishop CE, Dolznig H, Madel U, Feichtinger W, Atala A. and Hengstschlager M. (2010). Embryoid body formation of human amniotic fluid stem cells depends on mTOR. Oncogene 29:966–977 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ma X, Zhang S, Zhou J, Chen B, Shang Y, Gao T, Wang X, Xie H. and Chen F. (2012). Clone-derived human AF-amniotic fluid stem cells are capable of skeletal myogenic differentiation in vitro and in vivo. J Tissue Eng Regen Med 6:598–613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bottai D, Scesa G, Cigognini D, Adami R, Nicora E, Abrignani S, Di Giulio AM. and Gorio A. (2014). Third trimester NG2-positive amniotic fluid cells are effective in improving repair in spinal cord injury. Exp Neurol 254:121–133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sidney LE, Branch MJ, Dunphy SE, Dua HS. and Hopkinson A. (2014). Concise review: evidence for CD34 as a common marker for diverse progenitors. Stem Cells 32:1380–1389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.