Abstract

Between 2002 and 2007, the nonmedical use of prescription pain relievers grew from 11.0 million to 12.5 million people in the United States. Societal costs attributable to prescription opioid abuse were estimated at $55.7 billion in 2007. The purpose of this study was to comprehensively review the recent clinical and economic evaluations of prescription opioid abuse. A comprehensive literature search was conducted for studies published from 2002 to 2012. Articles were included if they were original research studies in English that reported the clinical and economic burden associated with prescription opioid abuse. A total of 23 studies (183 unique citations identified, 54 articles subjected to full text review) were included in this review and analysis. Findings from the review demonstrated that rates of opioid overdose-related deaths ranged from 5528 deaths in 2002 to 14,800 in 2008. Furthermore, overdose reportedly results in 830,652 years of potential life lost before age 65. Opioid abusers were generally more likely to utilize medical services, such as emergency department, physician outpatient visits, and inpatient hospital stays, relative to non-abusers. When compared to a matched control group (non-abusers), mean annual excess health care costs for opioid abusers with private insurance ranged from $14,054 to $20,546. Similarly, the mean annual excess health care costs for opioid abusers with Medicaid ranged from $5874 to $15,183. The issue of opioid abuse has significant clinical and economic consequences for patients, health care providers, commercial and government payers, and society as a whole. (Population Health Management 2014;17:372–387)

In the United States, prescription opioid abuse continues to be a significant and growing problem.1,2 In 2010, an estimated 12.2 million people reported using pain relievers non-medically for the first time within the past 12 months.3 Further, between 2002 and 2007, the nonmedical use of prescription pain relievers grew from 11.0 million to 12.5 million in the United States.2 According to the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) Survey, nonmedical use of prescription drugs is the second most prevalent type of drug abuse, after marijuana1; prescription drug abuse has been reported 56% more frequently than cocaine, heroin, hallucinogens, and inhalant abuse combined.1

A similar increasing trend in treatment admission rates for prescription opioid abuse has been observed. According to the Treatment Episode Data Set, the treatment admission rate for individuals abusing opiates other than heroin increased from 7 per 100,000 population in 1997 to 36 per 100,000 population in 2007 (an increase of 414%).4 Results from a survey conducted by Batten et al5 showed prescription drugs as the principal drug of abuse for nearly 10% of US patients in treatment. The most commonly reported abused drugs in the SAMHSA survey included oxycodone, hydrocodone, hydromorphone, methadone, morphine, and codeine.1

Over the past 7 years, prescription opioid abuse has gained nationwide attention. In 2005, Congress stated its concern about the diversion of controlled pharmaceuticals and approved the spending of $60 million from fiscal years 2006 to 2010 to help establish or improve prescription monitoring programs.1 Consequently, multiple congressional committees have been formed to address the misuse and abuse of controlled substances.1 A report based on testimony before the Subcommittee on Criminal Justice, Drug Policy, and Human Resources in 2006 described the epidemic of prescription drug abuse as “steadily, but sharply rising.”1

The increasing number of unintentional opioid overdose deaths in the United States has largely contributed to the growing clinical burden associated with prescription opioid abuse. An increase of 124% in the rate of unintentional overdose deaths was reported between 1999 and 2007, with a majority of this increase attributed to prescription opioid overdose deaths.6 From 1999 to 2009, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported that the number of opioid-related poisoning deaths has more than tripled.2 Furthermore, in 2012, the National Center for Health Statistics reported that opioid analgesic pain relievers were involved in more drug poisoning deaths than other specified drugs, including heroin and cocaine.7

From an economic perspective, prescription opioid abuse creates a substantial cost to society. Rice et al reported total losses to the economy related to drug abuse to be approximately $58.3 billion in 1985.8 A study conducted by Birnbaum et al provided a lower bound estimate of prescription opioid abuse of $8.6 billion in 2006. Contributing factors included health care costs ($2.6 billion), criminal justice costs ($1.4 billion), and workplace costs ($4.6 billion).9 More recently, Birnbaum et al conducted another study that estimated the societal costs of prescription opioid abuse to be $55.7 billion in 2007.2

In the existing literature, there are several estimates of the overall burden of illicit drug use. However, prior literature reviews focused specifically on the clinical and economic burden of prescription opioid abuse are limited. The objective of this study was to perform a comprehensive review of the literature to synthesize the current findings and understanding of the clinical and economic burden of prescription opioid abuse.

Methods

Literature search

The study team conducted a comprehensive literature search of MEDLINE through PubMed. The search strategy combined concepts related to prescription opioids, opioid-related disorders, burden of illness, economics, quality of life, and complications of prescription opioids or opioid-related disorders. The search was limited to articles published in English from October 2002 to October 2012. In addition to the MEDLINE search, a review of the bibliographies/reference lists of review articles was conducted to identify additional publications that were relevant for this review.

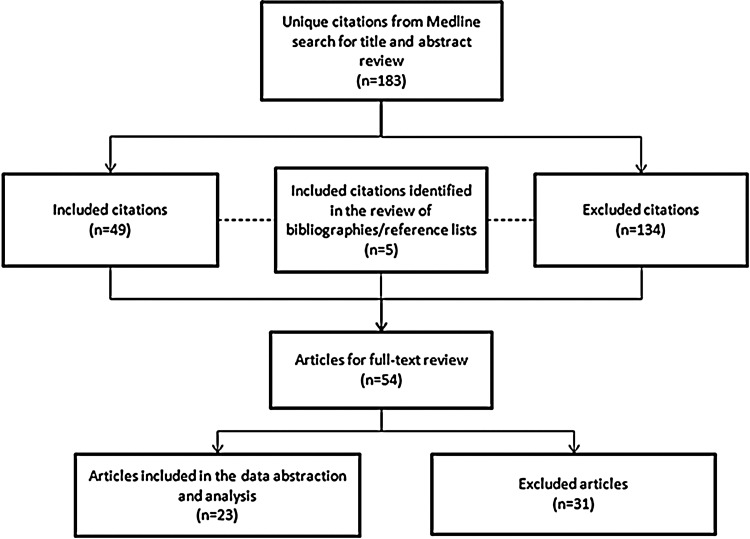

The search identified 183 unique citations. Articles were excluded (n=134) if they were of the following publication types: editorial, letter, case report, comment, news, or portrait, the title/abstract was focused on illicit drug use (ie, heroin, cocaine), or the article was an older version of another article captured in the search that studied identical outcomes. Articles were included (n=49) if they described the clinical (including overdose deaths and quality of life) and/or economic (including health care/resource utilization and cost) burden of prescription opioid abuse or the clinical and/or economic burden of prescription opioid abuse treatment. An additional 5 articles were identified in the review of bibliographies/reference lists. These 54 articles were subjected to full-text review; of these, 31 articles were excluded because they did not focus specifically on prescription opioid abuse. At the conclusion of the full-text review, a total of 23 articles were included in the data abstraction and analysis (Figure 1).

FIG. 1.

Overview of citation evaluation.

Data abstraction

Data abstraction focused on relevant study data including study design, population, and clinical and economic burden outcomes. Characteristics are outlined in Table 1.

Table 1.

Data Abstraction: Data of Interest

| Prescription Opioid Abuse Clinical Burden Studies | Prescription Opioid Abuse Economic Burden Studies | Treatment of Prescription Opioid Abuse | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data collected | Author(s) Publication year Publication source Study design Study population Type of insurance (where applicable) Focus of study: Opioid abuse, misuse, or diversion, where reported Main outcomes measure(s) Follow-up period Main findings: Findings of interest included disorders commonly associated with opioid abuse, opioid prescription patterns, and opioid overdose-related deaths |

Author(s) Publication year Publication source Study design Study population Type of insurance (where applicable) Focus of study: Opioid abuse, misuse, or diversion, where reported Costing/currency year: Perspective Costing period Resource utilization Total cost(s) |

Author(s) Publication year Publication source Study design Treatment type Costing/currency year: Costing period Study population Type of insurance (where applicable) Resource utilization Total cost(s) |

Results

Of the 23 studies included in this review, 7 discussed the clinical burden of prescription opioid abuse, 5 discussed the economic burden, 9 discussed both clinical and economic burden, and 2 discussed the treatment of prescription opioid abuse. There were 4 reports, 5 retrospective studies, 1 observational study, 1 trend analysis, 4 claims analyses, 1 literature review, 1 longitudinal study, 1 historical case control study, 4 cost studies, and 1 cost and utilization study (Table 2).

Table 2.

Study Characteristics

| Study Category | Author, Year | Study Design | Study Data and/or Population (n)/Type of Insurance (if applicable) | Follow-up Period | Abuse, Misuse, Diversion* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical Burden Studies | CDC, 201110 | Report of data from various agencies/surveys | Patients with data in one of the following: National Vital Statistics System multiple cause of death files, NSDUH, Kaiser Family Foundation, or TEDS (n=36,450 deaths) |

1999–2008, with data comparisons made between 2009/2010 and 1999 | Abuse |

| Volkow et al, 201111 | Data analysis report (prescription practices) | Opioid prescription data from the VONA database from SDI Health (Plymouth Meeting, Pennsylvania) (n=79.5 million opioid prescriptions) |

1 year (2009) | Abuse (possible contributors) | |

| Paulozzi et al, 200912 | Retrospective study | People in WV whose deaths involved methadone and those whose deaths involved OOA (methadone [n=87]; OOA [n=163]) | 1 year (2006) | Abuse, misuse and diversion | |

| Wesiner et al, 200913 | Retrospective study | Adult enrollees of 2 health plans, KPNC (n=12,517 and GH (n=2292) of Seattle, WA | 1997–2005 for GH and 1999–2005 for KPNC | Abuse | |

| Hall et al, 200814 | Population-based, observational study | All WV state residents who died of unintentional pharmaceutical overdoses in 2006 (n=295) | 1 year | Diversion | |

| Paulozzi et al, 200615 | Trend analysis | Data from the CDC and the US Drug Enforcement Administration | 1979–2002 | Abuse, misuse, diversion | |

| Franklin et al, 200516 | Retrospective study | Workers in WA | 1995–2002 | Abuse (potential) | |

| Economic Burden Studies | Birnbaum et al, 20112 | Cost study | Administrative claims data and data from publicly available secondary sources | 1 year (2007) | Abuse, misuse and diversion |

| Hansen et al, 201117 | Cost study | NSDUH | 1 year (2006) | Abuse, misuse and diversion | |

| Braden et al, 201018 | Retrospective study | Adult enrollees in Arkansas Medicaid (n=38,491) and HealthCore (n=10,159) | 12 months prior to and following the index date (first day of the opioid use episode) | Abuse | |

| DAWN, 2010 (Report)19 | Report | DAWN | Comparisons from 2004–2008 | Abuse | |

| Birnbaum et al, 20069 | Cost study | Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, other government data (NSDUH, TEDS, and DAWN) and a proprietary administrative claims database for an employed population | 1 year (2001) | Abuse | |

| Clinical AND Economic Burden Studies | CDC/Paulozzi et al, 201220 | Report | Patients who died of prescription drug overdose | NA | Abuse, misuse and diversion |

| White et al, 201121 | Retrospective claims analysis | Opioid abuse patients and demographically matched controls (Privately insured, opioid abuse patients [n=4474]/Controls [n=4474]; Florida Medicaid, opioid abuse patients [n=4667]/Controls [n=4667]) |

Costing study for a 12-month period; index date is 2003-2007 period | Abuse | |

| Baldasare, 2011, Brief Report/White Paper22 | Literature review | Online informational sources and numerous electronic databases for scholarly articles | 2000–2010 | Abuse | |

| Buse et al, 201123 | 2-phase, longitudinal, population-based study | Survey data (n=5796) | 4 years (2005–2009) | Abuse/dependence | |

| McAdam-Marx et al, 201024 | Historical case-control study | MAX data (n=37.5 million) | January 1, 2002, to December 31, 2003 | Abuse/dependence | |

| Braker et al, 200925 | Retrospective study | Patients in a Michigan Medicaid HMO and a large family medical practice (n=61) | 6 months | Misuse (potential) | |

| Cicero et al, 200926 | Claims analysis | Medical and drug benefit claims for privately (ie, no Medicare of Medicaid) insured people in a Midwest state (n=611,801) | 12 months (2004) | Abuse/dependence (proportion of patients in study) | |

| GAO testimonial, 200927 | Claims analysis | Medicaid beneficiaries in CA, IL, NY, NC, and TX | Fiscal years 2006 and 2007 | Abuse | |

| White et al, 200528 | Retrospective medical and pharmacy claims analysis | Self-insured employer health plans (abusers [n=740], non-abusers [n=2220]) | Costing study was 12-month period; 1998–2002 period | Abuse and dependence | |

| Treatment of Prescription Opioid Abuse Studies | Barnett, 200929 | Cost and utilization study | Individuals with opioid addiction receiving buprenorphine and methadone therapy (buprenorphine [n=606]; methadone [n=8191]) |

Federal fiscal year ending 30 September 2005 | NA |

| Ettner et al, 200630 | Cost study | Primary and administrative data from 43 substance abuse treatment providers in 13 counties in CA (main sample [n=2567]; sensitivity analysis cohort [n=6545]) |

2000–2001 | NA |

Not applicable for treatment studies.

CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; NSDUH, National Surveys on Drug Use and Health; TEDS, Treatment Episodes Data Set; VONA, Vector One: National; WV, West Virginia; OOA, other opioid analgesics; KPNC, Kaiser Permanente of Northern California; GH, Group Health Cooperative; WA, Washington; DAWN, Drug Abuse Warning Network; NA, not applicable; MAX, Medicaid Analytic eXtract; GAO, Government Accountability Office; HMO, health maintenance organization; CA, California; IL, Illinois; NY, New York; NC, North Carolina; TX, Texas.

Clinical burden of prescription opioid abuse

Opioid overdose-related deaths

Deaths related to opioid overdose were examined in 7 studies (Table 3). The number of opioid overdose-related deaths ranged from 5528 of the total 15,125 drug overdose deaths in 2002 (37%) to 14,800 of the 36,450 drug overdose deaths in 2008 (41%).9,15 From 1999 to 2002, a 129.2% increase in the number of deaths attributed to unintentional opioid analgesic overdose was observed. A majority of the individuals who died of an unintentional opioid overdose were male smokers with a mean age of 40 years.16 Overdose reportedly results in 830,652 years of potential life lost before age 65 years, which is comparable to the years of potential life lost from motor vehicle crashes.10

Table 3.

Opioid Overdose-related Death Studies

| Author, Year | Opioid Overdose-related Outcome Measure(s) | Overdose Rates | Overdose Demographics and Contributing Factors | Relationship between Prescriptions/Opioid Use and Overdose Death Rates |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Paulozzi et al/CDC, 201220 (Report) | Prescription drug overdoses | NR | In WV, UT, and OH, 25%–66% of those who died of pharmaceutical overdoses used opioids originally prescribed to someone else. | 80% are prescribed low doses (<100 mg morphine equivalent dose per day) by a single practitioner; account for 20% of all prescription drug overdoses. 10% of patients are prescribed high doses (≥100 mg morphine equivalent dose per day) of opioids by single prescribers; account for 40% of prescription opioid overdoses. 10% seek care from multiple doctors and are prescribed high daily doses; account for 40% of opioid overdoses. |

| Baldasare, 201122 (Brief Report/ White Paper) | Unintentional drug poisoning rates in the United States | From 1999–2004, the increase in unintentional drug poisoning rates was 62.5%, the majority of which were associated with prescription opioids. | NR | Increase in supply of prescription opioids coincides with 62.5% percent increase in unintentional drug poisoning rates. |

| CDC, 201110 | Fatal OPR overdoses | In 2008, OPR were involved in 14,800 (73.8%) of the 20,044 prescription drug overdose deaths. | NR | NR |

| Paulozzi et al, 200912 | Deaths related to methadone or OOA | NR | Most decedents were male; decedents in the methadone group were significantly younger than those in the OOA group: more than a quarter were 18–24 years of age. For both groups: ∼50% had a history of pain; ∼80% had a history of substance abuse. |

Methadone deaths: ever prescribed=32 (36.8%); prescribed within 30 days of death=28 (87.5%). Hydrocodone deaths: ever prescribed=48 (87.3%); prescribed within 30 days of death=30 (62.5%). Oxycodone deaths: ever prescribed=37 (68.5%); prescribed within 30 days of death=28 (75.7%). |

| Hall et al, 200814 | Prevalence of specific drugs and proportion prescribed to decedents; associations between demographics; substance abuse indicators and evidence of pharmaceutical diversion | NR | Substance abuse indicators were identified in 279 decedents (94.6%); 198 (67.1%) decedents were men; 271 (91.9%) were aged 18–54 years. Prevalence of diversion was highest among decedents 18–24 years; pharmaceutical diversion was associated with 186 (63.1%) deaths, 63 (21.4%) were accompanied by evidence of doctor shopping. |

Prescriptions for a controlled substance from 5 or more clinicians in the year prior to death was more common among women (30 [30.9%]) and decedents aged 35 through 44 years (23 [30.7%]) compared with men (33 [16.7%]) and other age groups (40 [18.2%]). Opioid analgesics were taken by 275 decedents (93.2%) but only 122 (44.4%) had ever been prescribed these drugs. |

| Paulozzi et al, 200615 | Deaths related to opioid analgesics (poisoning/overdose) | Unintentional drug poisoning mortality rates increased on average 5.3% per year from 1979 to 1990 and 18.1% per year from 1990 to 2002. Between 1999 and 2002, the number of opioid analgesic (all types) poisonings on death certificates increased 91.2%; listed in 5528 of the 15,125 drug overdose deaths (2002). |

NR | Total sales in kg:* 1999=33,381.7; 2002=56,752.3 Death occurrences/total sales:* 1999=0.08; 2002=0.07 |

| Franklin et al, 200516 | Opioid prescribing patterns and accidental death | 32 deaths definitely or probably related to accidental overdose of opioids. | 84% of deaths involved men 69% of deaths involved smokers |

NR |

Sales of other opioid type (codeine, oxycodone, hydrocodone, morphine and hydromorphone).

CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; WV, West Virginia; UT, Utah; OH, Ohio; NR, not reported; OPR, opioid pain relievers; OOA, other opioid analgesics.

Patients receiving prescriptions for higher opioid doses have been shown to have an increased risk of opioid overdose death.20 A study by Paulozzi et al reported that although only 10% of patients are prescribed high doses of opioids by a single prescriber, these patients account for approximately 40% of overdose deaths.20 Studies also have found that a significant proportion of individuals who have died of unintentional opioid overdose did not have a prescription for the opioid that caused their death. Substance abuse indicators were identified in almost all deaths and multiple contributory substances were reported in almost 80% of deaths.14

Prescription trends

A total of 7 studies assessed opioid prescription trends (Table 4). From 1997 to 2005, there was a 933% increase in methadone prescriptions, a 588% increase in oxycodone prescriptions, and a 198% increase in hydrocodone prescriptions.22 In 2009, there were a reported 79.5 million prescriptions for opioid analgesics in the United States. Of these, hydrocodone- and oxycodone-containing products accounted for almost 85% (67.5 million) of the total prescriptions.11 In a study of 61 Medicaid patients who received 3 or more prescriptions from 2 or more providers in a 6-month period for January through June 2003, the number of prescriptions per patient ranged from 3 to 28 (mean=8.4; standard deviation [SD]=5.5) and 64% had more than 6 prescriptions.25 The proportion of prescriptions dispensed increased with age, with 11.7% of prescriptions for patients 10–29 years of age, and 45.7% for those 40–59 years of age.11 The US Government Accountability Office (GAO) reported that approximately 65,000 Medicaid beneficiaries from selected states (California, Illinois, New York, North Carolina, and Texas) visited 6 or more doctors to acquire prescriptions for the same type of controlled substances during fiscal years 2006 and 2007. Furthermore, an analysis of Medicaid claims within these states found that at least 400 beneficiaries visited up to 112 medical practitioners and 46 different pharmacies for the same controlled substance.27

Table 4.

Prescription Trends Studies

| Author, Year | Prescription Pattern Outcome Measure(s) | Prescription Rates | Patient Demographics | Prescriber Demographics/Prescription Filling and Trends |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baldasare, 2011,22 Brief Report/White Paper | Opioid prescription rates | Methadone prescriptions=933% increase Oxycodone prescriptions=588% increase Hydrocodone prescriptions=198% increase |

NR | NR |

| Volkow et al, 201111 | Physician specialty, patient age, duration of prescription, and whether the patient had filled a prior prescription | 79.5 million prescriptions for opioid analgesics (2009). Most prescriptions were for hydrocodone- and oxycodone-containing products (84.9%, 67.5 million) and issued for short treatment courses (19.1% for <2 weeks, 65.4% for 2–3 weeks). |

The percentage of prescriptions dispensed increased with age: • 0–9 years=0.7% • 10–29 years=11.7% • 40–59 years=45.7% • ≥60 years=28.3% |

• Primary care physicians=28.8% (22.9 million) of total prescriptions • Internists (14.6%, 11.6 million) • Dentists (8.0%, 6.4 million) • Orthopedic surgeons (7.7%, 6.1 million) 56.4% (44.8 million) of opioid prescriptions were dispensed to patients who had already filled another opioid prescription within the past month. |

| White et al, 201121 | Number of prescriptions filled | Prescription drug use, % with ≥1 claim • Any prescription opioid: Privately insured=66.3/controls=20.1; Florida Medicaid=74.2/controls=30.2 • Any SAO: Privately insured=64.8 / controls=20.1; Florida Medicaid=72.2 / controls=29.7 • Any LAO: Privately insured=24.4/controls=0.9; Florida Medicaid=32.7/controls=3.6 Both SAO and LAO: Privately insured=22.9/controls=0.9; Florida Medicaid=30.7/controls=3.1 |

NR | Prescription opioids, number filled – Mean (SD) Privately insured: • Opioid abuse patients (n=4474)=9.5 (13.4) ∘ LAOs=2.1 (5.1); SAOs=7.4 (11.0) • Controls (n=4474)=0.6 (2.8) ∘ LAOs=0.1 (0.9); SAOs=0.6 (2.4) Florida Medicaid: • Opioid abuse patients (n=4667)=10.0 (11.2) ∘ LAOs=2.6 (5.1); SAOs=7.5 (8.8) • Controls (n=4667)=2.1 (5.3) ∘ LAOs=0.3 (1.8); SAOs=1.8 (4.5) |

| Braker et al, 200925 | Number of prescriptions and prescribers | Prescriptions for opioids ranged from 3–28/patient; mean of 8.4 (SD=5.5) >6 prescriptions=64% patients |

NR | Number of prescribers ranged from 2–10; mean of 3.7 (SD=1.8) • Number of providers was positively correlated with prescription number (β=1.16, r2=0.15, P=0.002) 2 patients had ≥4 different types of opioid medications but had on average 7.5 providers (P=0.04). |

| GAO, 200927 (Testimonial) | Medicaid claims paid in fiscal years 2006 and 2007 | NR | NR | Approximately 65,000 Medicaid beneficiaries visited ≥6 doctors to acquire prescriptions for the same type of controlled substances (2006 and 2007). At least 400 beneficiaries visited 21–112 medical practitioners and up to 46 different pharmacies for the same controlled substance. |

| Wesiner et al, 200913 | Opioid use episodes, long-term opioid episodes, medication use profiles | KPNC prescription rates increased from 44.1% to 51.1%; GH prescription rates increased from 15.7% to 52.4%. |

Long-term opioid users with a prior substance abuse diagnosis received higher dosage levels, were more likely to use Schedule II and LAOs, and were more often frequent users of sedative-hypnotic medications in addition to their opioid use. | KPNC prevalence of long-term use increased from 11.6% to 17.0% for those with substance use disorder histories and from 2.6% to 3.9% for those without; respective GH rates, increased from 7.6% to 18.6% and from 2.7% to 4.2%. |

| Franklin et al, 200516 | Opioid prescribing patterns and accidental death | The total number of paid prescriptions for Schedule II–IV opioids: ∼120,000 prescriptions annually in 1996 to ∼150,000 annually in 2002. Prescriptions for Schedule II opioids increased 2.5 times, from ∼23,000 annually in 1996 to ∼57,000 annually in 2002. As a percent of all scheduled opioids (II–IV), Schedule II prescriptions increased from 19.3% in 1996 to 37.2% in 2002. |

NR | NR |

SAOs, short-acting opioids; LAOs, long-acting opioids; NR, not reported; SD, standard deviation; GAO, Government Accountability Office; KPNC, Kaiser Permanente of Northern California; GH, Group Health Cooperative.

The prevalence of long-term opioid use has been reported to be as high as 18.6% in 2005 among patients with substance use disorders in a Washington State health care plan (n=3900).13 These patients received higher dosage levels, were more likely to use Schedule II and long-acting opioids,13,16 and frequently used sedative-hypnotic medications in addition to opioids.13

Comorbid conditions

Comorbid conditions were assessed in 4 studies (Table 5). Among individuals with opioid abuse/dependence or chronic use, approximately 50% reported a pain-related comorbidity. The percentage of individuals with a comorbid psychiatric disorder ranged from 11.4–71.1%.28,31 Among the 4 studies, comorbidities were reported to occur at a higher rate in individuals who chronically use or abuse opioids compared to those who do not use opioids.24,26,28,31

Table 5.

Comorbid Conditions Studies

| Author, Year | Comorbidities: Main Findings |

|---|---|

| Buse et al, 201131 | • Probable dependence users: depression=51.0%; anxiety=25.5%; rate of CVD risk factors and events=61.4%. |

| McAdam-Marx et al, 201024 | • 84% of abuse/dependence patients and 52% of control patients had at least 1 of the predefined comorbidities. The most common comorbidities in the abuse/dependence group included psychiatric disorders (49%), any pain-related diagnosis (49%), and substance abuse (45%). • Comorbidities potentially related to risky behaviors, such as any substance abuse (45%) and HIV/AIDS (15%), were notably present in the abuse/dependence patients compared to the control group (8% prevalence for both). |

| Cicero et al, 200926 | • Muscle, joint, and limb pain were the most frequent pain diagnoses in all 3 groups (diagnosed in more than 50% of the chronic opioid group); back pain (51%), arthritis (33.3%), abdominal pain (21%), neck pain (20%), and headaches (19%). • The chronic opioid use group had a significantly greater burden of physical ailments than either the acute or non-opioid groups; mental health disorders were found in 35% of all chronic opioid users. |

| White et al, 200528 | • Among the opioid abusers group, psychiatric diagnoses=71.1%, other substance abuse=50.4%, any painful comorbidity=47.6%, trauma=36.5%, low back pain=19.3%, non-opioid poisoning=17.6%, other chronic pain=17.3%, arthritis=15.0%, skin infections/abscesses=10.1%, sexually transmitted diseases=8.0%, headache/migraine=7.7%, hepatitis (A, B, and C)=6.5%, other musculoskeletal pain=5.9%. |

CVD, cardiovascular disease; HIV/AIDS, human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome.

Economic burden of prescription opioid abuse

Resource utilization

Eight studies examined resource utilization among the prescription opioid abuse population (Table 6). These studies found that when compared to non-abusers, opioid abusers were generally more likely to utilize medical services, such as the emergency department (ED), physician or mental health outpatient visits, and inpatient hospital stays.18,19,21–23,25,26,28 Compared to non-abusers, opioid abusers were found to be 4 times as likely to visit the ED, 11 times as likely to have had a mental health outpatient visit, and 12 times as likely to have had an inpatient hospital day.22

Table 6.

Resource Utilization Studies

| Resource Utilization: Main Findings | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Author, Year | ED | Outpatient | Inpatient |

| Baldasare, 201122 | Opioid abusers are 4 times as likely to visit the ED. | Opioid abusers are 11 times as likely to have had a mental health outpatient visit. | Opioid abusers are 12 times as likely to have had an inpatient hospital stay. |

| Buse et al, 201131 | Encounters in the previous 12 months: Current Probable Dependent Opioid User (n=153) – Mean (SD): ED/UCC visits=1.2 (3.65) |

Health care encounters in the previous 12 months: Current Probable Dependent Opioid User (n=153) – Mean (SD): PCP/OB-GYN visits=2.07 (3.75); PA/NP visits=0.48 (1.23); Neurologist/specialist visits=0.77 (1.52); Mental/alternative HCP visits=1.17 (2.65) |

NR |

| White et al, 201121 | Medical service use, % with ≥1 claim: Privately insured=64.6/controls=19.6; Florida Medicaid=80.8/controls=26.8 | Medical service use, % with ≥1 claim • Physician/outpatient: Privately insured=97.1/ controls=82.3; Florida Medicaid=98.6/controls=65.9 • Psychiatric facility visits: Privately insured=53.7/controls=6.2; Florida Medicaid=NR/controls=NR |

Medical service use, % with ≥1 claim • Privately insured=60.4/controls=7.0; Florida Medicaid=89.2/controls=46.6 Hospital inpatient, length of stay, days, Mean (SD) • Privately insured=12.9 (18.4)/controls=5 (7.0); Florida Medicaid=37.2 (39.6)/controls=14.7 (18.8) |

| Braden et al, 201018 | ED visits: 24.2% of the HealthCore group (n=38,491); 28.2% of the Arkansas Medicaid group (n=10,159) | NR | NR |

| DAWN, 201019 (Report) | The estimated number of ED visits was 144,644 in 2004 and 305,885 in 2008; increase of 111% ED visits involving oxycodone products, hydrocodone products, and methadone increased 152%, 123%, and 73%, respectively. |

NR | NR |

| Braker et al, 200925 | NR | ≥3 telephone messages related to opioid medication=13 patients (23%); these patients had: • on average 2 more prescriptions per 6 months than other patients (p=0.04) • 17 times more likely to request early refills (OR=17.6, 95% CI=2.9–105.2) • more likely to receive increasing doses of medication (OR=6.5, 95% CI=1.6–27.4) |

NR |

| Cicero et al, 200926 | Chronic opioid group=0.62 | Office visits: chronic opioid group=16.91 | Hospital days: chronic opioid group=1.66 |

| White et al, 200528 | Percentage of opioid abuse patients with ≥1 visit=17.4% | Percentage of opioid abuse patients with ≥1 visit or claim: • Physician's visits=97.3% • Mental health outpatient=45.5% • Other place of service=61.5% • Mental disorders=71.1% • Trauma=36.5% • Substance abuse treatment outpatient=9.2% |

Percentage of opioid abuse patients with ≥1 visit or claim: • Hospital inpatient=67.8% • Substance abuse treatment inpatient=14.6% • Mental health inpatient=12.6% |

ED, emergency department; SD, standard deviation; UCC, urgent care center; PCP, primary care physician; OB-GYN, obstetrician-gynecologist; NR, not reported; PA, physician assistant; NP, nurse practitioner; HCP, health care professional; DAWN, Drug Abuse Warning Network; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

In a study assessing a privately insured population and opioid use measured in days of supply (DOS), defined as the number of therapy days, study subjects were divided into 3 groups: acute opioid, chronic opioid, and non-opioid use. The acute opioid use group was defined as individuals who received 1 prescription for less than 10 DOS of opioid analgesics in the calendar year, whereas chronic opioid use consisted of individuals who received 180 DOS or more per year. The non-opioid group comprised individuals who filed 1 or more non-opioid insurance claims in the calendar year and did not file an opioid insurance claim. Results found that the chronic opioid group on average had 0.62 ED visits, compared with 0.31 and 0.11 ED visits in the acute opioid and non-opioid groups, respectively. In addition, the chronic opioid group had, on average, 16.91 physician office visits, compared with 8.67 and 5.06 office visits in the acute opioid and non-opioid groups, respectively. Similarly, the chronic opioid group had 1.66 inpatient hospital days, whereas the acute opioid and non-opioid groups had 0.56 and 0.22 inpatient days, respectively.26

Opioid abuse or dependence is strongly related to ED utilization.18 The Drug Abuse Warning Network (DAWN) estimated that the number of ED visits involving nonmedical use of opioids increased 111% from 2004 (144,644 visits) to 2008 (305,885 visits).19 Furthermore, studies showed that the proportion of patients with 1 or more ED visit claims ranged from 17.4%–80.8% within a 12-month study period.21,28

Cost of prescription opioid abuse

The cost of prescription opioid abuse in the United States was examined in 8 studies (Table 7). In 2006, reported total costs of nonmedical use for individual opioids ranged from $30 million for fentanyl to $12.7 billion for hydrocodone.17 Total annual costs ranged from $8.6 billion in 2001 (or $9.5 billion in 2005 US dollars [USD]) to $55.7 billion in 2007 (in 2009 USD).2,22 Workplace costs accounted for a majority of total costs, followed by health care costs, and criminal justice costs.2,17,22 When compared to a matched control group (non-abusers), mean annual excess health care costs for opioid abusers with private insurance ranged from $14,054 to $20,546.21,22,24,28 White and colleagues21 assessed opioid abuse patients and demographically matched controls using privately insured (Ingenix Employer Solutions Data) and Florida Medicaid administrative claims data from 2003 to 2007. Privately insured opioid abuse patients (n=4474) incurred $24,193 in total direct health care costs per patient; in contrast, privately insured non-opioid abuse controls (n=4474) incurred only $3647 in total direct health care costs per patient, amounting to a mean annual excess of $20,546 in health care costs for opioid abusers. The privately insured population in this analysis was obtained from a database covering 9 million lives during 1999 to 2007 and comprised information from 40 self-insured companies operating nationwide in a myriad of industries. For the Medicaid study population, opioid abuse patients (n=4667) incurred $26,724 in total direct health care costs per patient, compared to $11,541 for matched controls (n=4667). Studies in this review showed that the mean annual excess health care costs for opioid abusers with Medicaid ranged from $5874 to $15,183.21,22,24,28

Table 7.

Cost Studies

| Author, Year | Costing/Currency Year, Perspective, Costing Period | Health Care Costs | Criminal Justice | Workplace Costs | Total Costs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baldasare, 201122 (Brief Report/White Paper) | US$, currency year varies | $2.6 billion (2001) | $1.4 billion (2001) | $4.6 billion (2001) | $8.6 billion in 2001 The annual medical costs for opioid abusers were $14,054 higher than non-abusers with private insurance and $6650 higher than non-abusers with Medicaid. |

| Birnbaum et al, 20112 | 2009 US$, societal perspective, 1 year (2007) | $25 billion | $5.1 billion | $25.6 billion | $55.7 billion |

| Hansen et al, 201117 | 2006 US$ | $2.2 billion (misuse treatment) $944 million (medical complications: HIV/AIDS, chronic hepatitis C, neonatal care) |

$8.2 billion | $42 billion | $53.4 billion Total costs for prescription opioids of interest:* • Hydrocodone, $12.7 billion • Propoxyphene, $8.7 billion • OxyContin, $7.3 billion • Methadone, $6.2 billion • Oxycodone, $6.0 billion |

| White et al, 201121 | 2009 US$, Private Payer, Medicaid; 12-month period | Mean annual health care costs for caregivers per patient=$4171; controls=$3161. Prescription drug costs per patient=$1038; controls=$689. Medical costs per patient=$3133; controls=$2472. |

NR | NR | Total direct health care costs per patient (Mean [±SD]): Privately insured=$24,193 (±$41,578); privately insured controls=$3,647 (±$11,512). Medicaid=$26,724 (±$33,935); Medicaid controls=$11,541 (±$21,666). |

| McAdam-Marx et al, 201024 | 2002–2003 US$, Medicaid payer perspective; January 1, 2002, to December 31, 2003 | NR | NR | NR | Mean total costs (±SD) Abuse/dependence patients=$14,537 (±$18,211). Control group=$8663 (±$27,632); difference of $5874); (P<.001). Abuse/dependence patients also had significantly higher costs when LTC claims were excluded (subtotal costs) with excess costs of $6651 (P<.001). |

| GAO, 200927 (Testimonial) | NR, fiscal year 2006–2007 | NR | NR | NR | State programs paid over $200,000 for controlled substances during fiscal years 2006 and 2007 for post-death controlled substance prescription claims. Medicaid paid ∼$500,000 in Medicaid claims based on controlled substance prescriptions “written” by over 1200 doctors after they died. |

| Birnbaum et al, 20069 | 2001 US$ (Costs in discussion inflated to 2005 US$), societal perspective; 1 year (2001) | $2.61 billion | $1.43 billion | $4.54 billion | Total societal costs of prescription opioid analgesic abuse=$8.58 billion |

| White et al, 200528 | 2003 US$; private payer; 12-month period 1998–2002 period | NR | NR | NR | Opioid abusers=$15,884; non-abusers=$1,830 (P<0.01) |

Selected costs >$6 billion are presented in this table.

HIV/AIDS, human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome; SD, standard deviation; LTC, long-term care; GAO, Government Accountability Office.

Treatment of prescription opioid abuse

Cost of treatment

Two studies examined the cost of prescription opioid abuse treatment (Table 8). An analysis conducted in 200929 found that the mean cost of care for the 6 months after treatment initiation was $11,597 for buprenorphine treatment and $14,921 for methadone treatment (P<0.001). Findings in this study showed that there was an average of 67 to 157 ambulatory visits and 9 to 12 hospitalization days for patients receiving methadone, buprenorphine, or both treatments. Average ambulatory care costs for patients ranged from $1203 (methadone) to $1287 (buprenorphine). When neither treatment was given, the average cost of ambulatory care was $984.29 Another study conducted by Ettner et al30 reported that substance abuse treatment costs over the 9 months post baseline averaged $1583.

Table 8.

Treatment of Prescription Opioid Abuse: Cost Studies

| Author, Year | Costing Period/Currency Year | Total Cost/Currency Year |

|---|---|---|

| Barnett, 200929 | Federal FY ending 30 September 2005; 2005 US$ | • Mean cost of care for the 6 months after treatment initiation was $11,597 for buprenorphine and $14,921 for methadone (P<0.001). |

| • Average ambulatory care cost was $1287/month when buprenorphine therapy was under way, $1203 when methadone treatment was under way, and $984 when neither treatment was given. | ||

| Ettner et al, 200630 | 2000–2001; 2001 US$ | • On average, substance abuse treatment costs $1583 and was found to be associated with a monetary benefit of $11,487 to society, representing a greater than 7:1 ratio of benefits to costs. These benefits were primarily because of reduced costs of crime and increased employment earnings. |

FY=fiscal year.

Discussion

In a recent study assessing trends in visits for noncancer pain and strong opioid (morphine-related) medication from 2000 to 2010, researchers utilized the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NAMCS), a nationally representative database of US physician office visits, and found that there was no significant change in the proportion of pain-related physician visits.32 Throughout the 10-year period, pain was consistently reported and diagnosed by physicians at approximately one fifth of all visits. Although non-opioid pain-relieving drugs remained stable between 26%–29% throughout the decade, the rate of opioid prescriptions significantly increased from 11.3% in 2000 to 19.6% in 2010. After adjustment of covariates, few patient, physician, or practice characteristics were related to higher or lower rates of opioid use; hence, findings showed that increases in opioid prescribing occurred non-selectively. The authors concluded that non-opioid prescribing decreased despite a lack of clear evidence demonstrating that opioids are safer and more effective in treating noncancer pain.32

A growing awareness of the increasing prevalence and ramifications of pain within the health care community has driven efforts to improve both the identification and management of the condition. The inadvertent impact of these well-meaning efforts may have led to an increase in opioid use and abuse as well as a high economic burden in terms of health care costs and lost productivity. The staggering increase observed in prescription methadone (933%), oxycodone (588%), and hydrocodone (198%)22 reflects these efforts and also suggests several phenomena and trends in expanded pain guidelines, which in part have led to inappropriate utilization. Many researchers have asserted that drug therapy with opioid analgesics maintains an important role in pain management and should be available when needed.33–35 The Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) reinforced this notion, stating that clinicians should not hesitate to prescribe opioids when they are the best choice of treatment and clinicians should be knowledgeable about using opioids to treat pain.36 Moreover, the perception that pain is often undertreated and is a major public health problem has catalyzed a movement of patient advocacy groups, and legislature-enacted pain treatment acts to ensure immunity for physicians who prescribe opioids within the statute requirements.1 Because of perceived undertreatment for pain, advocacy groups and professional organizations also have been formed to develop guidelines to improve pain management.37 However, some guidelines have not been developed from evidence-based medicine, and physicians often are not adequately trained in pain management, leading to unparalleled demand and subsequent growth in opioid prescriptions to manage pain. Since 2001, California physicians have been required to complete 12 hours of continuing education training for pain management.38 Unfortunately, not all states have this minimal requirement of management and physicians appear to provide prescriptions for opioids without the appropriate training. Hence, this may contribute to the ease of “doctor shopping,” whereby an individual visits several physicians complaining of a range of symptoms as a means to obtain prescriptions. The DEA has stated that the diversion and abuse of legitimately produced controlled pharmaceuticals comprises a worldwide multibillion dollar illicit market.39,40 There are various modes of diversion in which drugs are diverted from their lawful purpose to illicit use; these are usually attributed to doctor shopping, theft, illegal Internet pharmacies, prescription forgeries, and illicit prescriptions by physicians. Doctor shopping is the most common method of obtaining prescriptions33–35,41,42 as evidenced by the GAO report of 65,000 Medicaid beneficiaries visiting 6 or more doctors to acquire prescriptions for the same type of controlled substances during fiscal years 2006 and 2007.27 Furthermore, an analysis of Medicaid claims found that at least 400 beneficiaries visited up to 112 medical practitioners and 46 different pharmacies for the same controlled substance.27 In addition, sales of prescription drugs over the Internet are a major business and present many challenges in preventing drug abuse.43

Drug abuse poses a substantial impact to society in terms of clinical and economic burden. Overdose reportedly results in 830,652 years of potential life lost before age 65, which is comparable to the years of potential life lost from motor vehicle crashes.10 The increase of 129.2% in deaths attributable to unintentional opioid analgesic overdose from the period of 1999 to 2002 in the Paulozzi study15 not only suggests the widespread prevalence of opioid abuse, but also the potential misunderstanding of the risks of opioid use. As previously described, one study found that approximately 50% of patients who misuse opioids report a pain-related comorbidity.28

From an economic perspective, pain prescription drug spending has skyrocketed in the United States. Currently, more than $9 billion is spent on opioids in a year.44 In addition, the White House Budget Office has estimated that drug abuse costs the US government nearly $300 billion a year.1 Furthermore, prevalence rates for inpatient hospital visits were more than 12 times higher for opioid abusers compared with non-abusers (P<0.01), demonstrating that opioid abusers are more likely to have higher levels of medical and prescription drug utilization.28 Mean annual direct health care costs for opioid abusers ($15,884) were more than 8 times higher than for non-abusers ($1830).28 Similarly, mean annual excess health care costs for opioid abusers with Medicaid ranged from $5874 to $15,183.22 Direct costs and increased resource utilization related to nonmedical opioid use are considerable, with treatment for opioid abuse bearing significant costs. A study by Barnett showed mean 6-month costs of $11,597 and $14,921 for buprenorphine and methadone treatment, respectively.29 Another study reported that substance abuse treatment costs over the 9 months post baseline averaged $1583.30 This cost was associated with a monetary benefit to society of $11,487, which translated to a greater than 7:1 ratio of benefits to costs.29 Reduced costs for crime and an increase in employment earnings primarily contributed to these benefits. Although the treatment of opioid abuse has an overall beneficial net effect to society, the costs inflicted upon payers in both the public and private sectors are significant.

The Food and Drug Administration and the DEA are working to minimize abuse, misuse, and diversion of controlled substances.1 Monitoring programs like Researched Abuse, Diversion, and Addiction-Related Surveillance System (RADARS) and prescription drug monitoring programs (PDMPs) provide insight into the trends of opioid abuse as well as help curtail prescription fraud and doctor shopping. In addition, payers may be able to monitor the number of pharmacies and physicians utilized by patients who are prescribed opioids as a proxy for potential misuse. Finally, tamper-resistant formulations as well as medications that have multiple mechanisms of action to alleviate pain may help to decrease the likelihood for opioid abuse.

In a similar effort to monitor opioid utilization and potentially minimize opioid abuse, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services recently introduced the Medicare Part D Overutilization Monitoring System (OMS). The OMS uses 3 types of outlier metrics to identify patients with potential overutilization issues: (1) opioid outliers (noncancer patients whose daily morphine equivalent dose is greater than 120mg for at least 90 consecutive days, and who used more than 3 prescribers and more than 3 pharmacies; (2) acetaminophen outliers (patients who may be taking more than 4g of acetaminophen per day for more than 30 days); and (3) referral outliers (beneficiaries referred by the Medicare Center for Program Integrity for review of possible utilization issues).45

Pharmacies also are making efforts to help prevent and minimize opioid abuse. A major US retail pharmacy has instituted a “Good Faith Dispensing” policy that requires pharmacists to contact the prescribing physician and ensure that the diagnosis, billing code, previous medications tried and failed, and expected length of therapy are correct in order to verify prescriptions for controlled substances. This new policy is speculated to be related to the DEA's concentrated effort on the company in their scandal regarding “pill mills.” These “pill mills” were elaborate schemes where “patients” and physicians diverted massive quantities of prescription pain relievers through fake clinics.46 Monitoring programs such as OMS, RADARS, and PDMP, and retail pharmacies have developed specific initiatives with the objective of assisting with identifying overutilization of prescribed medications, which in turn may also help prevent opioid abuse, misuse, and diversion.

Limitations

There are several limitations to this study. First, the study team did not assess the quality of the studies and included studies and reports varying in quality. Although every effort was made to include only studies that clearly described the methodologies and results, studies also were included that discussed the topic of opioid abuse to be comprehensive in this review. Second, the study team was unable to differentiate studies of abuse, misuse, or diversion because studies often did not report the difference between the 3. In fact, abuse, misuse or diversion may result in different clinical and economic burdens. Presently, definitions between these 3 phenomena are unclear. Therefore, this review of opioid abuse also encompasses misuse and diversion. Future research is warranted to disentangle the effects of these 3 separate but intertwined topics. In addition, because International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) codes for opioid abuse often are not utilized, there is likely an underreporting of opioid abuse in published claims-based studies. Therefore, the rates of diagnosed opioid abuse reported herein are expected to be much lower than the actual rate of opioid abuse in a given population. In addition, because the cost estimates from these studies were frequently obtained from claims databases, the true economic impact may be underreported. Many patients also pay with cash to avoid detection by managed care and, as such, any likely opioid abuse would be underreported. Lastly, the study team did not adjust reported costs to current year because of the varied methodologies and currency years used by studies to arrive at cost estimates, which introduces uncertainty when drawing comparisons between study results. However, cost findings from this review provide the relative range and magnitude of the economic impact of opioid abuse.

Implications

Findings from this review highlight the significant clinical and economic burden of opioid abuse on the health care system and, in particular, payers from both the government and private sectors. According to results from the 2002 National Survey on Drug Use and Health,45,47,48 Medicare, Medicaid, the military, and other government health care paid or supplemented payments for opioid abuse treatment in at least 80% of the population, whereas private health insurance supplemented 30% of the population. Although more than 1 source of payment was reported by survey subjects for these estimates, this survey provides an overview of the magnitude of social costs and impact sustained by payers to treat opioid abuse. In light of limited resources, these additional costs borne by payers could be minimized and funneled toward more critical public health and disease areas that need to be addressed.

Conclusion

The issue of opioid abuse has significant clinical and economic consequences for patients, health care providers, commercial and government payers, and society as a whole. Future quality improvements to prevent and minimize abuse, misuse, and diversion must focus on better utilizing clearly defined International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) codes to report this problem and to better characterize what abuse entails. The recent need for health care providers to transition from the use of ICD-9 to ICD-10 diagnosis and procedure codes may provide an opportunity to increase awareness regarding the appropriate use of codes for these patients. Educational programs for both health care providers and the community, along with PDMPs, also may play an important role.49

Additional research is needed to further study the effects and differences between abuse, misuse, and diversion. More importantly, there is a clear need to assess and develop technology for opioids, such as tamper-resistant formulations, to lower and minimize the risk of abuse.

Author disclosure statement

Drs. Meyer, Quock, and Mody, Ms. Patel, and Ms. Rattana declared the following conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Dr. Meyer is an employee of Janssen Scientific Affairs and stockholders of Johnson & Johnson; Ms. Patel was a fellow at Janssen Scientific Affairs during manuscript development; Ms. Rattana and Dr. Quock are consultants to Janssen; and Dr. Mody was an employee of Janssen Scientific Affairs during manuscript development and a stockholder of Johnson & Johnson.

Funding for this study was provided by Janssen Scientific Affairs.

References

- 1.Manchikanti L. Prescription drug abuse: what is being done to address this new drug epidemic? Testimony before the Subcommittee on Criminal Justice, Drug Policy and Human Resources. Pain Physician 2006;9:287–321 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Birnbaum HG, White AG, Schiller M, Waldman T, Cleveland JM, Roland CL. Societal costs of prescription opioid abuse, dependence, and misuse in the United States. Pain Med 2011;12:657–667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.The National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH). 2010 NSDUH Table 1.18A—Nonmedical use of pain relievers in lifetime, past year, and past month, by detailed age category: numbers in thousands, 2009 and 2010. <http://www.samhsa.gov/data/NSDUH/2k10ResultsTables/NSDUHTables2010R/HTM/Sect1peTabs1to46.htm#Tab1.18A>. Accessed January31, 2013

- 4.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Office of Applied Studies. Treatment episode data set (TEDS): 1997–2007. National Admissions to Substance Abuse Treatment Services, DASIS Series: S-47. Rockville, MD: Department of Health and Human Services, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Batten HL, Horgan CM, Protas JM, et al. Drug services research survey. Phase II final report. Waltham, MA: Submitted to the National Institute on Drug Abuse. Institute for Health Policy. Brandeis University, February12, 1993 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bohnert AS, Valenstein M, Bair MJ, et al. Association between opioid prescribing patterns and opioid overdose-related deaths. JAMA 2011;305:1315–1321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.The National Center for Health Statistics. NCHS data on drug poisoning deaths. December2012. <http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/factsheets/factsheet_drug_poisoning.pdf>. Accessed August21, 2013

- 8.Rice DP, Kelman S, Miller LS. Estimates of economic costs of alcohol and drug abuse and mental illness, 1985 and 1988. Public Health Rep 1991;106:280–292 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Birnbaum HG, White AG, Reynolds JL, et al. Estimated costs of prescription opioid analgesic abuse in the United States in 2001: a societal perspective. Clin J Pain 2006;22:667–676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Vital signs: overdoses of prescription opioid pain relievers—United States, 1999–2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2011;60:1487–1492 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Volkow ND, McLellan TA, Cotto JH, Karithanom M, Weiss SR. Characteristics of opioid prescriptions in 2009. JAMA 2011;305:1299–1301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Paulozzi LJ, Logan JE, Hall AJ, McKinstry E, Kaplan JA, Crosby AE. A comparison of drug overdose deaths involving methadone and other opioid analgesics in West Virginia. Addiction 2009;104:1541–1548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weisner CM, Campbell CI, Ray GT, et al. Trends in prescribed opioid therapy for non-cancer pain for individuals with prior substance use disorders. Pain 2009;145:287–293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hall AJ, Logan JE, Toblin RL, et al. Patterns of abuse among unintentional pharmaceutical overdose fatalities. JAMA 2008;300:2613–2620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Paulozzi LJ, Budnitz DS, Xi Y. Increasing deaths from opioid analgesics in the United States. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2006;15:618–627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Franklin GM, Mai J, Wickizer T, Turner JA, Fulton-Kehoe D, Grant L. Opioid dosing trends and mortality in Washington State workers' compensation, 1996-2002. Am J Ind Med 2005;48:91–99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hansen RN, Oster G, Edelsberg J, Woody GE, Sullivan SD. Economic costs of nonmedical use of prescription opioids. Clin J Pain 2011;27:194–202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Braden JB, Russo J, Fan MY, et al. Emergency department visits among recipients of chronic opioid therapy. Arch Intern Med 2010;170:1425–1432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Office of Applied Studies. The DAWN report: trends in emergency department visits involving nonmedical use of narcotic pain relievers. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Office of Applied Studies, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Paulozzi L, Baldwin G, Franklin G, et al. CDC grand rounds: prescription drug overdoses—a U.S. epidemic. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2012;61(1):10–13 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.White AG, Birnbaum HG, Schiller MA, Waldman T, Cleveland JM, Roland CM. Economic impact of opioid abuse, dependence, and misuse. Am J Pharm Benefits 2011;3(4):e59–e70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baldasare A. The cost of prescription drug abuse: a literature review. <http://www.docstoc.com/docs/98740436/20110106-cost-of-prescription-drug-abuse>. Accessed March4, 2014

- 23.Buse D, Manack A, Serrano D, et al. Headache impact of chronic and episodic migraine: results from the American Migraine Prevalence and Prevention study. Headache 2011;52(1):3–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McAdam-Marx C, Roland CL, Cleveland J, Oderda GM. Costs of opioid abuse and misuse determined from a Medicaid database. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother 2010;24(1):5–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Braker LS, Reese AE, Card RO, Van Howe RS. Screening for potential prescription opioid misuse in a Michigan Medicaid population. Fam Med 2009;41:729–734 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cicero TJ, Wong G, Tian Y, Lynskey M, Todorov A, Isenberg K. Co-morbidity and utilization of medical services by pain patients receiving opioid medications: data from an insurance claims database. Pain 2009;144(1–2):20–27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.US Government Accountability Office (GAO). Medicaid: fraud and abuse related to controlled substances identified in selected states. <http://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-09-1004T>. Accessed March4, 2014

- 28.White AG, Birnbaum HG, Mareva MN, et al. Direct costs of opioid abuse in an insured population in the United States. J Manag Care Pharm 2005;11:469–479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barnett PG. Comparison of costs and utilization among buprenorphine and methadone patients. Addiction 2009;104:982–992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ettner SL, Huang D, Evans E, et al. Benefit-cost in the California treatment outcome project: does substance abuse treatment “pay for itself”? Health Serv Res 2006;41(1):192–213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Buse DC, Pearlman SH, Reed ML, Serrano D, Ng-Mak DS, Lipton RB. Opioid use and dependence among persons with migraine: results of the AMPP study. Headache 2012;52(1):18–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Daubresse M, Chang HY, Yu Y, et al. Ambulatory diagnosis and treatment of nonmalignant pain in the United States, 2000–2010. Med Care 2013;51:870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Manchikanti L, STAATS PS, Singh V, et al. Evidence-based practice guidelines for interventional techniques in the management of chronic spinal pain. Pain Physician 2003;6:3–80 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gureje O, Von Korf M, Simon GE, Gater R. Persistent pain and well-being: a World Health Organization study in primary care. JAMA 1998;280:147–151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bressler HB, Keyes WJ, Rochon PA, Badley E. The prevalence of low back pain in the elderly. A systemic review of the literature. Spine 1999;24:1813–1819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.United States Department of Justice, Drug Enforcement Administration, Office of Diversion Control. Practitioner's manual: an informational outline of the Controlled Substances Act of 1970. <http://www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov/pubs/manuals/pract/index.html>. Accessed March4, 2014

- 37.Commonwealth of Kentucky, Cabinet for Health and Family Services, Office of the Inspector General. Kentucky All Schedule Prescription Electronic Reporting (KASPER). A comprehensive report on Kentucky's prescription monitoring program. <http://chfs.ky.gov/nr/rdonlyres/7057e43d-e1fd-4552-a902-2793f9b226fc/0/kaspersummaryreportversion2.pdf>. Accessed March4, 2013

- 38.Drug Strategies. Internet Drugs: Testimony before the US House of Representatives. Statement of Barbara Van Rooyan, July6, 2006. <http://www.drugstrategies.com/int_rooyan.html>. Accessed March4, 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 39.US Government Accountability Office. Prescription drugs: state monitoring programs provide useful tool to reduce diversion. <http://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-02-634>. Accessed March4, 2014

- 40.United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC). World drug report 2005. <http://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/data-and-analysis/WDR-2005.html>. Accessed January31, 2013

- 41.Trescot AM, Boswell MV, Atluri SL, et al. Opioid guidelines in the management of chronic non-cancer pain. Pain Physician 2006;9:1–40 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lawrence RC, Helmick CG, Arnett FC, et al. Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and selected musculoskeletal disorders in the United States. Arthritis Rheum 1998;41:778–799 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Drug Strategies. Internet Drugs: Testimony before the US House of Representatives. Statement of Mathea Falco President, Drug Strategies, July26, 2006. <http://www.drugstrategies.com/int_falco.html>. Accessed March4, 2014

- 44.Catan T, Perez E. A pain-drug champion has second thoughts. <http://online.wsj.com/news/articles/SB10001424127887324478304578173342657044604>. Accessed March4, 2014

- 45.Tudor CG; Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Memo to all Part D sponsors: Medicare Part D overutilization monitoring system. <http://www.amcp.org/uploadedFiles/Production_Menu/Policy_Issues_and_Advocacy/Letters,_Statements_and_Analysis_-_docs/2013/OMS%20HPMS%20Announcement%20Memo_FINAL_070513.pdf>. Accessed March4, 2014

- 46.Foreman J. Backlash against Walgreen's new painkiller crackdown. <http://commonhealth.wbur.org/2013/08/walgreens-painkiller-crackdown>. Accessed January17, 2013

- 47.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Office of Applied Studies. National survey of substance abuse treatment services (NSSATS): 2002. <http://www.samhsa.gov/data/DASIS/02nssats/nssats2002report.pdf>. Accessed March4, 2014

- 48.US Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services, Office of Applied Studies. Results from the 2003 national survey on drug use and health: national findings. <http://www.samhsa.gov/data/nhsda/2k3nsduh/2k3ResultsW.pdf>. Accessed March4, 2014

- 49.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Strategies and interventions for reducing nonmedical use of prescription drugs: a review of literature (2006–2013). <http://captus.samhsa.gov/access-resources/strategies-and-interventions-reducing-nonmedical-use-prescription-drugs-review-lite>. Accessed November20, 2013