Abstract

Background: Approximately 20% of seniors live with five or more chronic medical illnesses. Terminal stages of their lives are often characterized by repeated burdensome hospitalizations and advance care directives are insufficiently addressed. This study reports on the preliminary results of a Palliative Care Homebound Program (PCHP) at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota to service these vulnerable populations.

Objective: The study objective was to evaluate inpatient hospital utilization and the adequacy of advance care planning in patients who receive home-based palliative care.

Methods: This is a retrospective pilot cohort study of patients enrolled in the PCHP between September 2012 and March 2013. Two control patients were matched to each intervention patient by propensity scoring methods that factor in risk and prognosis. Primary outcomes were six-month hospital utilization including ER visits. Secondary outcomes evaluated advance care directive completion and overall mortality.

Results: Patients enrolled in the PCHP group (n=54) were matched to 108 controls with an average age of 87 years. Ninety-two percent of controls and 33% of PCHP patients were admitted to the hospital at least once. The average number of hospital admissions was 1.36 per patient for controls versus 0.35 in the PCHP (p<0.001). Total hospital days were reduced by 5.13 days. There was no difference between rates of ER visits. Advanced care directive were completed more often in the intervention group (98%) as compared to controls (31%), with p<0.001. Goals of care discussions were held at least once for all patients in the PCHP group, compared to 41% in the controls.

Introduction

Seniors with multiple chronic illnesses comprise a large proportion of the growing frail elders. Eighty percent of all older adults suffer from at least one chronic condition, and 50% with at least two.1,2 As disease progresses, these patients often begin to suffer increasing symptom burden and disability while care coordination becomes more complex and fragmented. Terminal stages of their lives are often met with repeated institutionalization, burdensome transitions, and insufficient understanding of goals of care.3–5 Patterns of health outcomes are more defined by chronic illnesses that require frequent needs for higher levels of care. Those with chronic illness account for approximately 32% of total Medicare spending during the last two years of life, the majority going towards repeated hospitalizations.6

Increasingly, institutions are developing new models of care delivery for the vulnerably ill in all health care settings.7 Palliative care homebound programs consist of an integrated model of services to provide comprehensive palliative care including assessment and management of symptom burden and goals of care. Promising results have surfaced, including reductions in ER visits, 30-day readmission rates, skilled nursing placement, inpatient length of stay, improved quality of life, and patient satisfaction.8–10 It is important to identify the key elements to these services that have brought such successful results. This remains underinvestigated in the literature. This study also brings into harmony the importance of advance care planning and individual goals of care discussions as the key potential ingredient towards reducing unwanted burdens in the chronically ill.

In particular, the oldest and most frail individuals have more choices to consider, and often experience other burdens outside of physical symptoms. This includes end-of-life transitions between facilities, which are also associated with poor quality of end-of-life care.5 Decision aids have also been developed to better prioritize health-related preferences in older adults.11 However, this does not address specific life-sustaining interventions.

Advance care planning is a crucial process that should be initiated early on at the time of chronic diagnosis.12 Patients' understanding of their disease may ultimately affect their preferences about the rehospitalization process and other decisions regarding interventions towards the end of life. There currently is limited evidence to demonstrate that palliative care home-based programs have effectively addressed patients' goals of care or advance care directives. Our hypothesis is that advance care planning and individual goals of care discussions are a key element to reduce unwanted burdens and ineffective interventions in advanced illness.

This study sought to investigate the effectiveness of a home-based palliative care service model for vulnerable patients with life-limiting disease in Rochester, Minnesota in reducing the frequency of hospitalizations, length of hospital stays, and proper addressing of advance care directives.

Methods

Study design and setting

This retrospective cohort pilot study evaluated patient outcomes of those enrolled in a program providing home-based palliative care for a six-month observation period, compared with a matched control group that did not receive the intervention. This study was conducted in Employee and Community Health (ECH) at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota. ECH is a primary care practice enrolled in the Minnesota Medical Home program with over 21,000 individuals 60 years of age and older. This is a combined internal medicine and family medicine practice with several sites in the Rochester area.10 This study was approved by the Mayo Clinic's institutional review board.

Subjects

Intervention group

Patients enrolled in the PCHP from September 2012 to March 2013 were identified through the Mayo Clinic unified health enterprise platform database. Patients in this program are homebound, high risk, and frail individuals with life-limiting illnesses. Enrollment criteria include Elder Risk Assessment (ERA) score cutoff >16, four-year mortality prognostic index >14, and Centers for Medicare and Medicaid services definition of homebound.13

1. The ERA is a risk stratification tool used to identify patients in the upper decile risk for hospital readmission, emergency department visit, skilled nursing facility placement, and mortality. This score is automatically calculated for all patients in the General Disease Management System.

2. The index for four-year mortality in older adults developed by Lee, et al. is a prognostic index instrument for older adults, incorporating independent predictors of mortality including specific comorbid diseases and functional variables. A total score of 14 or more predicts a 64% risk of death within four years.14

Most PCHP patients were recruited from its sister service, the Care Transitions Program (CTP). This program targets hospitalized patients with ERA scores above 16 for a post-acute home-based intervention to reduce hospitalization. Additionally, all patients expressed wishes not to pursue life-sustaining measures and were established as a do-not-resuscitate (DNR) order. No patients were currently enrolled in hospice or skilled nursing facility prior to matriculation. Other exclusion criteria included transplant patients, dialysis patients, and those who had repeated inpatient psychiatric admissions.

Control group

For each PCHP enrolled patient, two control patients were identified through Mayo Clinic electronic database for Care Transitions Program (CTP) eligibility. The control patients were matched through propensity scoring methods where age, gender, CTP eligibility, and 4 year Mortality prognosis index scores were similar. All mortality prognosis indexes were calculated through chart abstraction. Patients in the control group continued with their usual, standard care through primary care visits, subspecialty visits, and care coordination offered outside of program responsibilities. A retrospective chart review of matched control patients was also conducted in the same six-month timeframe as PCHP patients.

Palliative Care Homebound Program intervention

This program provides a home-visit service delivering medical and symptom based care in the months to years preceding hospice eligibility.15 Care is focused on optimizing symptom management and maximizing quality of life. Referrals are generally made by primary care physicians or hospital discharge patients who fit criteria. The service structure includes an interdisciplinary care team involving registered nurses (RNs), nurse practitioners (NPs), geriatricians, and palliative care consultants. Social services, pharmacists and case management services are also readily available. In terms of staffing, one full time NP typically covers a panel of 20–35 high-acuity patients at a time. One RN for two NP panels are assigned to service hospital enrollment, phone triage, follow-up calls, scheduling, and liaison with community based organizations. An MD is assigned to the weekly one-hour interdisciplinary team meeting for each NP. The MD will also provide a home visit twice annually on average for the palliative care homebound patient. Acute visits were also performed within one business day of an acute symptom report. Critical aspects of the program include consistent advanced care planning and goals of care discussions. Other program responsibilities include chronic disease management, home safety assessments, community resource referrals, education on self-management of illness, and contingency planning strategies such as reviewing specific protocols the patients and caregivers may follow, as well as emergency contacts if their symptoms are not under control. The team also provides education and support for the patient and family, with intermittent reassessment of care.

Primary and secondary outcomes

The primary outcomes were hospital admissions, total hospital days and ER visits following six months from program entry compared to controls in similar time frame. Secondary outcomes were the difference in the amount of advance directive planning between PCHP versus control group at six months. Previously charted advance directive documents including Minnesota advance directive forms, Mayo Clinic health directives, Living Wills were also abstracted, including those that were newly established during intervention period. Physician Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment (POLST) outlined specific direction about resuscitation status including additional limited interventions in the setting of reversible disease. Any of the above files that were scanned into EMR within the past ten years was documented as present or absent. Secondary outcomes also looked at mortality between the two groups. Date of death was observed outside of the six month cohort and analyze through time to even analysis curve.

Data collection

Data were abstracted from the EMR through chart review and verified twice by the primary investigator (CYC) for all patients. Baseline data for both groups contained demographic information including age, gender, comorbid health conditions, code status, ERA and four-year mortality index score eligibility for program entry. Other chart-abstracted information included previously documented advance directives, POLST forms that were scanned into the EMR as well as the number of verbal discussions involving patient's health related goals of care. Goals of care discussions include any documented dialogue held by any care team member that involved addressing or readdressing the patient's specific health care wishes. The number of hospital admissions, ER visits and total number of hospital days were separately totaled during the six-month observation period.

Analysis

Baseline characteristics of all patients including age, gender, comorbid illnesses, ERA scores, four-year mortality scores, body mass index (BMI) were summarized using mean (±SD) or frequency where appropriate. They were compared between groups using McNemar's test or conditional logistic regression analysis. The primary outcomes of six-month hospital admission rate, total number of hospital days and ER admissions and goals of care discussions were also summarized using mean (±SD). Advance care directives, hospice utilization were assessed as percentages.

The comparison analyses were first handled by the two-sample t-test or Pearson chi square test, given that controls were matched based on propensity scoring methods incorporating prognosis measures, and there were not any significant differences between the two groups at baseline. Kaplan-Meier survival curves were evaluated and compared by log-rank statistics between the two groups. Generalized linear model, multivariate logistic model, and Cox proportional hazard model were used to compare the group difference after adjusting for dementia severity and CHF.

In all cases, p values<0.05 were considered statistically significant. All statistical analysis were performed by SAS (SAS version 9.3; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Power analysis

This study was done to evaluate the difference between hospitalization rates of PCHP patients and control patients. A two-group t-test with a 0.05 two-sided significance level had 80% power to detect an effect size of 0.470, which is a small difference, when the sample sizes in the two groups were 54 and 108, respectively.

Results

Subjects and patient characteristics

PCHP had enrolled 116 patients, of which 54 matriculated between the months of September 2012 through March 2013 and were used as intervention patients. The average age of PCHP patients was 87.94 years (±6.56 SD), 56% were female with an average ERA score of 18.47±6.28 SD, and average 4 Year Mortality index score was 16.41±1.88 SD. The matched comparison group had 108 patients. Comparison of the two groups revealed no significant difference between age, gender, hospital readmission risk, and four-year prognosis risk assessment scores. Patients in the PCHP group had a higher proportion of patients with moderate to advanced degrees of dementia. Congestive heart failure appeared to be more prevalent in the control group (64% versus 43%). The remainder of comorbidities did not show any differences between the two groups (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of 54 Patients in PCHP Program, 108 in Control Group

| Controls (N=108) | PCHP group (N=54) | p value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 87.19 | ±6.66 | 87.94 | ±6.56 | 0.49 |

| Gender, n (%) | 0.91 | ||||

| Female | 60 | 56% | 30 | 56% | |

| Male | 48 | 44% | 24 | 44% | |

| ERA | 19.23 | ±3.64 | 18.47 | ±6.28 | 0.43 |

| Lee Score | 16.12 | ±2.03 | 16.41 | ±1.88 | 0.39 |

| BMI | 26.92 | ±94.27 | 24.88 | ±1.22 | 0.19 |

| Code Status (DNR) | 58 | 53.7% | 52 | 96.3% | <0.001 |

| Comorbid conditions: | |||||

| Dementia, n (%) | <0.001 | ||||

| Advanced | 6 | 6% | 21 | 39% | |

| Moderate | 28 | 26% | 24 | 44% | |

| Mild | 42 | 39% | 8 | 15% | |

| None | 32 | 30% | 1 | 2% | |

| DM, n (%) | 28 | 26% | 17 | 31% | 0.46 |

| CHF, n (%) | 69 | 64% | 23 | 43% | 0.01 |

| Stroke, n (%) | 0.78 | ||||

| N | 85 | 79% | 43 | 80% | |

| Y | 23 | 21% | 11 | 20% | |

| COPD, n (%) | 36 | 33% | 14 | 26% | 0.34 |

| Cancer, n (%) | 16 | 15% | 7 | 13% | 0.75 |

ERA, elder risk assessment; BMI, body mass index; DNR, do not resuscitate; DM, diabetes mellitus; CHF, congestive heart failure; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Primary outcomes

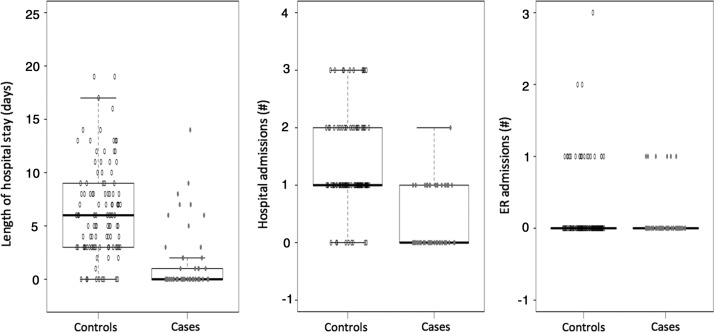

In the control group, 92% of patients were admitted to the hospital at least one time over six months, as compared to 33% in the PCHP group (p<0.001). The average number of hospital admissions was statistically significantly higher at 1.36 admissions in the control group versus 0.35 in PCHP (p<0.001). Average total hospital days was also statistically different between the two groups, PCHP patients averaging 1.46 (±2.93 SD) days in an inpatient setting compared to 6.59 (±4.86 SD) in the control group (p<0.001). There was no significant difference between the numbers of ER visits that did not result in hospital inpatient admission. This was a separate index from hospital admissions since many patients who were admitted usually required inpatient stay. The analysis adjusted for dementia severity and CHF showed similar results (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Primary Outcomes: Health Care Utilization

| Controls (N=108) | PCHP group (N=54) | p value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of hospital admits in 6 months, n (%) | <0.001 | ||||

| 0 | 9 | 8% | 36 | 67% | |

| 1 | 65 | 60% | 17 | 31% | |

| 2 | 22 | 20% | 1 | 2% | |

| 3 | 11 | 10% | 0 | 0% | |

| 5 | 1 | 1% | 0 | 0% | |

| Average hospital admit | 1.36±0.85 | 0.35±0.52 | <0.001 | ||

| Adjusted by CHF/dementia | 1.33 | 0.32 | <0.001 | ||

| Average total hospital stays (d) | 6.59±4.86 | 1.46±2.93 | <0.001 | ||

| Adjusted by CHF/Dementia | 6.62 | 1.03 | <0.001 | ||

| ER Admissions: | |||||

| 0 | 87 | 81% | 48 | 89% | 0.46 |

| 1 | 18 | 17% | 6 | 11% | |

| 2 | 2 | 2% | 0 | 0% | |

| 3 | 1 | 1% | 0 | 0% | |

| Average ER admissions: | 0.23±0.52 | 0.11±0.32 | 0.1364 | ||

| Adjusted by CHF/dementia | 0.24 | 0.12 | 0.1889 | ||

| Went to hospice, n (%) | 0.06 | ||||

| N | 104 | 96% | 48 | 89% | |

| Y | 4 | 4% | 6 | 11% | |

| Death, n (%) | 0.07 | ||||

| N | 89 | 82% | 37 | 69% | |

| Y | 19 | 18% | 17 | 31% | |

CHF, congestive heart failure; ER, emergency room.

Secondary outcomes

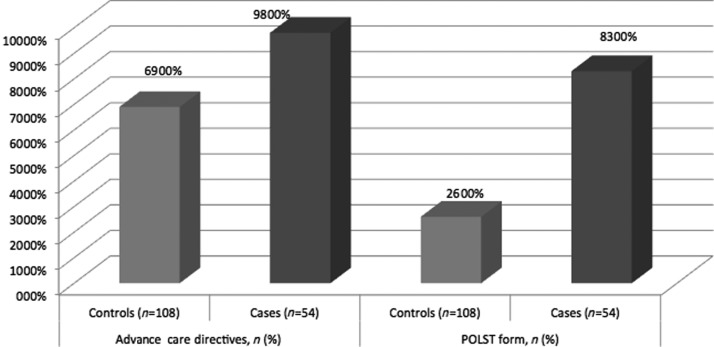

Secondary analysis evaluated the adequacy of addressing advance care directives in the form of paper documentation and goals of care discussions. Of the 54 patients enrolled in the PCHP group, 98% of patients had scanned advance care directive documentation on file in EMR, as compared to 69% in the control group (p<0.001). Verbal goals of care discussions were held at least one time for all PCHP patients by various members of the care coordination team, and occurred on three or more separate encounters for 31% of these individuals. In the control group, 59% of patients did not have any documented discussions in regards to their health-related goals of care during this six-month time frame. A much higher percentage of POLST forms was completed for the intervention group (83% versus 26%), approximately a third of which was completed for the first time, and 19% involved specific changes or updates to the form in regards to the patient's health care wishes during the intervention period. All of these comparisons showed statistical significance (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Advance Care Directive Documentation

| Controls (N=108) | PCHP group (N=54) | p value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Documented advanced directives, n (%) | <0.001 | ||||

| No | 34 | 31% | 1 | 2% | |

| Yes | 74 | 69% | 53 | 98% | |

| Adjusted analysis | 0.0048 | ||||

| Goals of care discussions, n (%) | <0.001 | ||||

| 0 | 64 | 59% | 0 | 0% | |

| 1 | 44 | 41% | 9 | 17% | |

| 2 | 0 | 0% | 28 | 52% | |

| 3 | 0 | 0% | 11 | 20% | |

| 4 | 0 | 0% | 6 | 11% | |

| Average goals of care discussions | 0.41±0.49 | 2.26±0.87 | <0.001 | ||

| POLST documentation, n (%) | <0.001 | ||||

| No | 80 | 74% | 9 | 17% | |

| Yes | 28 | 26% | 45 | 83% | |

| Adjusted analysis | <0.001 | ||||

| Changes made to POLST form, n (%) | <.001 | ||||

| No | 97 | 90% | 29 | 54% | |

| Yes | 11 | 10% | 10 | 19% | |

| First-time forms | 0 | 0% | 15 | 28% | |

POLST, physician order for life sustaining treatment.

FIG. 1.

Primary outcomes: Hospital admissions, length of hospital stay, ER admissions between cases and controls.

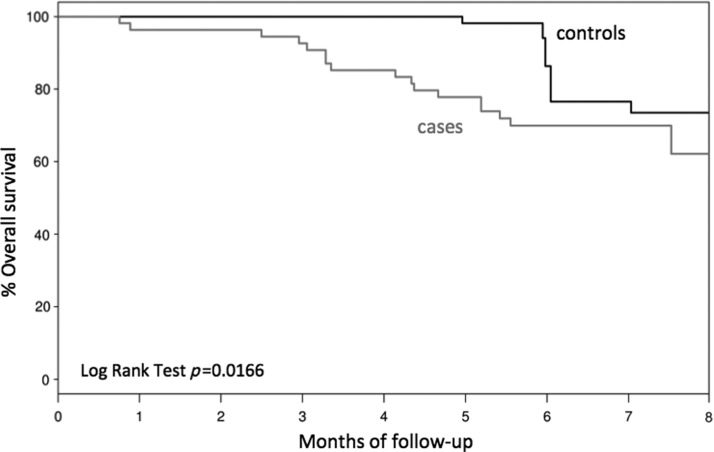

Mortality was also evaluated by time to event analysis curve. The date of death was documented and graphed on the Kaplain-Meier curve for both patient groups, including those who died after the six-month follow-up. Survival curves showed a steeper decline in overall survival among PCHP patients within the first five months, which then appear to merge closer around the eight-month mark (see Fig. 3). The Cox proportional hazard model showed that the cases and controls were not different on survival (p=0.78) after adjusting for CHF and dementia.

FIG. 3.

Survival curve.

FIG. 2.

Advance care directives.

Discussion

The results of this pilot retrospective cohort study demonstrate that PCHP was associated with decreased hospital admission rate and average total hospital days. Other studies have demonstrated similar results, showing those who do not receive palliative care intervention averaged four times as many hospital visits in one year.9 This study design involved a control group matched with advanced risk assessment tools that also factor in a four-year prognostic morbidity indicator.

PCHP was associated with a reduction of the six-month hospitalization rate and an average of 5.13 days reduction in hospital days. Although previous literature has also shown a reduction in ER visits, we did not see a significant difference, though the numbers were very small in both groups.

We found that early involvement in the palliative care model helped patients address choices about specific medical interventions and plan for future health-related decisions in line with their goals of care. Almost all patients in the PCHP group had some form of advanced care documentation previously filed, including 83% of patients with completed POLST forms indicating very specific treatment preferences. Goals of care discussions were held at least once for all patients in the PCHP group, as compared to 41% in the control group. Many care discussions (31%) occurred at least three or more times on separate occasions involving members of the care team. Of the POLST forms that were completed, 37% were forms that were done for the first time, or involved specific changes and updates at least once during the six-month intervention period. Most importantly, our results indicate that discussions took place frequently between care team members and program enrollees to ensure that all parties continue to understand the goals that are in line with their disease progression.

This study is unique because it brings the importance of advance care planning in harmony with one's medical decisions surrounding health care utility. Previous studies funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality show that less than 50% of terminally ill patients had an advance directive in their medical record, and only 12% of patients with advance care directives received input from their medical team in its development, suggesting that there is insufficient guidance.16,17 Our study shows that early palliative care involvement is associated with an improvement in the advance care planning process throughout the continuum of one's disease. Patient-centered goals of care and expectations should be reassessed frequently as health conditions change. Most advance directives forms such as living will and healthcare proxy do not anticipate the specific circumstances surrounding critical decisions and many patients change their mind throughout the process. Patients may require more intimate collaborative decision making with family and providers, involving repeated reassessments during different points of one's health trajectory.18,19 The use of this documentation needs to be clear and specific, as it has an impact not only on the patient, but also on the health care team.20 With this in mind, reduced hospital admissions may be a reflection of properly understanding one's advance care directives.

Mortality was 18% in the control group and 31% in the PCHP group (p<0.007). Time to event analysis demonstrated a larger gap between death rates in the first three to six months. We suspect that the initial steeper death rates of the PCHP group may be a reflection of patients who were better informed about their prognosis and therefore made decisions in preference of quality over quantity of life. A higher percentage of patients had more moderate to advanced dementia in the palliative care group. Patients with advanced cognitive impairment have an end-of-life trajectory marked by particularly high rates of functional impairment nearing time of death,21 partially explaining the difference between raw and unadjusted comparisons, possibly reflecting the steeper time to event analysis curve.

Table 4.

Results Adjusted for CHF and Dementia

| LOS | # admission | # ER admission | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | Controls | Cases | Controls | Cases | Controls | Cases |

| N_USED | 108 | 54 | 108 | 54 | 108 | 54 |

| MEDIAN | 6 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| MEAN | 6.59 | 1.46 | 1.36 | 0.35 | 0.23 | 0.11 |

| SD | 4.86 | 2.93 | 0.85 | 0.52 | 0.52 | 0.32 |

| MIN | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| MAX | 31 | 14 | 5 | 2 | 3 | 1 |

| 2-sample t-test | p<0.0001 | p<0.0001 | p=0.1200 | |||

| Result from generalized linear model after adjusting CHF and dementia | ||||||

| LS mean | 6.62 | 1.03 | 1.33 | 0.32 | 0.24 | 0.12 |

| Type III SS | p-value | p-value | p-value | |||

| Cases vs control | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.1889 | |||

| CHF | 0.8744 | 0.8210 | 0.0659 | |||

| Dementia degree | 0.1262 | 0.0502 | 0.4863 | |||

LOS, length of stay; ER, emergency room; SD, standard deviation; LS mean, least squares mean; Type III SS, sum of squares; CHF, congestive heart failure.

There are potential limitations in our study. The most important is that all patients in the PCHP were DNR and therefore had expressed understanding of their prognosis and preferences in care. Despite advanced matching methods with controls based on assessment scores and prognostic indicators, patients who are in the PCHP are inherently different. Matching still left a disparity between comorbidities such as dementia and congestive heart failure. Therefore, the differences were adjusted for through generalized linear model, multivariate logistic model, and Cox proportional hazard model. Many patients who were enrolled in the PCHP were also transitioned from the hospital-based care transition program; therefore much of the care coordination and advance care planning may have already been partially established prior to program matriculation. In a retrospective cohort study, there is the possibility of missed outcomes if patients traveled outside the region. It would not be expected to have a differential effect for either group with this limitation. Furthermore, the sample was drawn in a small population in Minnesota over a six-month period of time, which limits its generalizability to other populations, organizational systems, and communities.

The findings in this study provide important information as we move towards a medical home model with emphasis on population health. By integrating palliative care early into the framework of one's disease management, several benefits may be achieved. Providers and caretakers will be able to better understand the patient's wishes and goals of care. Chronically ill individuals may be more equipped to manage their own illnesses, potentially reducing unnecessary hospitalizations and time away from loved ones at home. This translates to potentially reduced cost and better quality of life, with reduction in repeated institutionalization. Our target population of homebound advanced medical illness patients are the most likely to benefit given their isolation from accessible outpatient medical care. More studies are needed to evaluate the generalizability of these programs across different communities and organizations with varying resource availabilities.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Dr. Gregory Hanson and supporting staff for their dedicated work towards the Palliative Care Homebound Program and its continued development. This project was made possible by CTSA Grant UL1 TR000135 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Ladha A, et al. : Care of the frail elder: The nexus of geriatrics and palliative care. Minnesota Med 2013;96:39–42 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.http://www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/resources/publications/AAG/aging.htm Accessed October2013

- 3.Mudge AM, Shakhovskoy R, Karrasch A: Quality of transitions in older medical patients with frequent readmissions: Opportunities for improvement. Eur J Intern Med 2013;24:779–783 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kass-Bartelmes B, Hughes R: Advance Care Planning: Preferences for Care at the End of Life. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gozalo P, et al. : End-of-life transitions among nursing home residents with cognitive issues. N Engl J Med 2011;365:1212–1221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.http://www.dartmouthatlas.org/keyissues/issue.aspx?con=2944 Accessed October2013

- 7.Crews DE, Zavotka S: Aging, disability, and frailty: Implications for universal design. J Physiol Anthropol 2006;25:113–118 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brumley R, et al. : Increased satisfaction with care and lower costs: Results of a randomized trial of in-home palliative care. J Am Geriatr Soc 2007;55:993–1000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brumley RD, Enguidanos S, Cherin DA: Effectiveness of a home-based palliative care program for end-of-life. J Palliat Med 2003;6:715–724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Takahashi PY, et al. : 30-day hospital readmission of older adults using care transitions after hospitalization: A pilot prospective cohort study. Clin Interv Aging 2013;8:729–736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fried TR, et al. : Health outcome prioritization to elicit preferences of older persons with multiple health conditions. Patient Educ Couns 2011;83:278–282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bomba PA, Vermilyea D: Integrating POLST into palliative care guidelines: A paradigm shift in advance care planning in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2006;4:819–829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.http://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/Manuals/downloads/bp102c07.pdf Accessed October2013

- 14.Lee SJ, et al. : Development and validation of a prognostic index for 4-year mortality in older adults. JAMA 2006;295:801–808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.http://intranet.mayo.edu/charlie/employee-community-health-rst/home/specialties-programs/ctp-about-us/ Accessed October2013

- 16.Teno J, et al. : Advance directives for seriously ill hospitalized patients: Effectiveness with the patient self-determination act and the SUPPORT intervention. SUPPORT Investigators. Study to Understand Prognoses and Preferences for Outcomes and Risks of Treatment. J Am Geriatr Soc 1997;45:500–507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Teno JM, et al. : Do advance directives provide instructions that direct care? SUPPORT Investigators. Study to Understand Prognoses and Preferences for Outcomes and Risks of Treatment. J Am Geriatr Soc 1997;45:508–512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fried TR, et al. : Inconsistency over time in the preferences of older persons with advanced illness for life-sustaining treatment. J Am Geriatr Soc 2007;55:1007–1014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sharp T, et al. : Do the elderly have a voice? Advance care planning discussions with frail and older individuals: A systematic literature review and narrative synthesis. Br J Gen Pract 2013;63:657–668 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Perez MD, Macchi MJ, Agranatti AF: Advance directives in the context of end-of-life palliative care. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care 2013;7:406–410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Covinsky KE, et al. : The last 2 years of life: Functional trajectories of frail older people. J Am Geriatr Soc 2003;51:492–498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]