Abstract

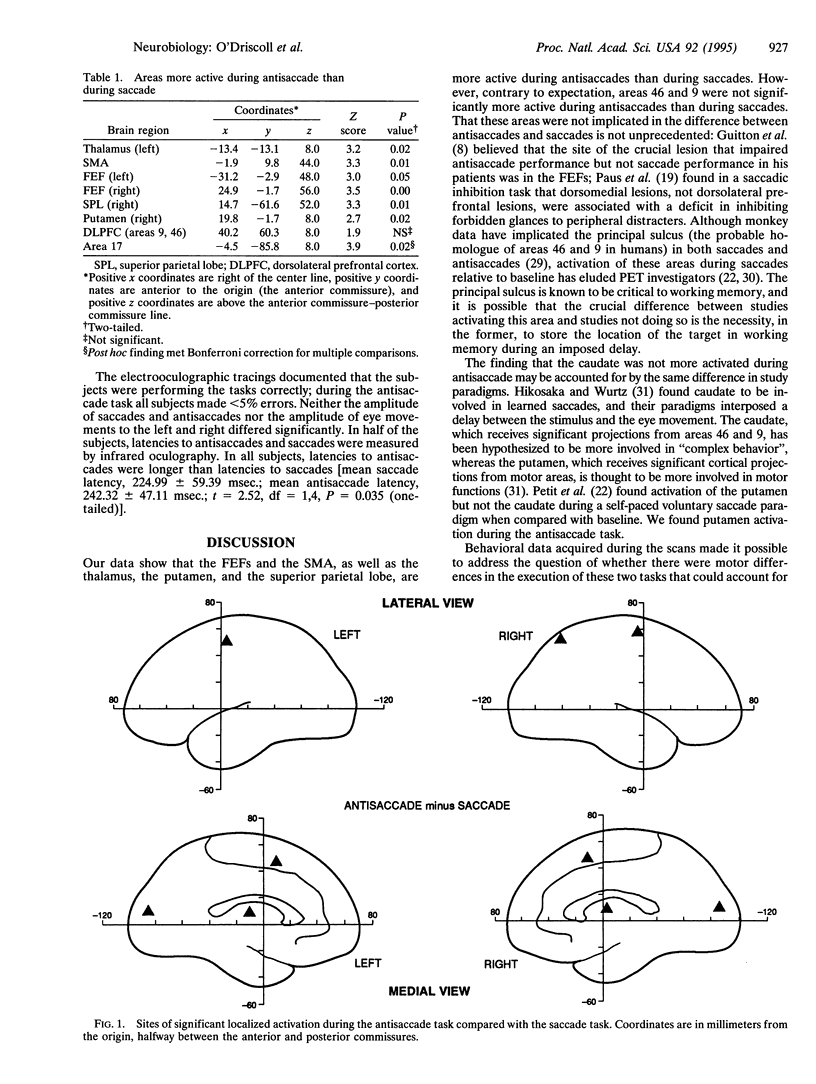

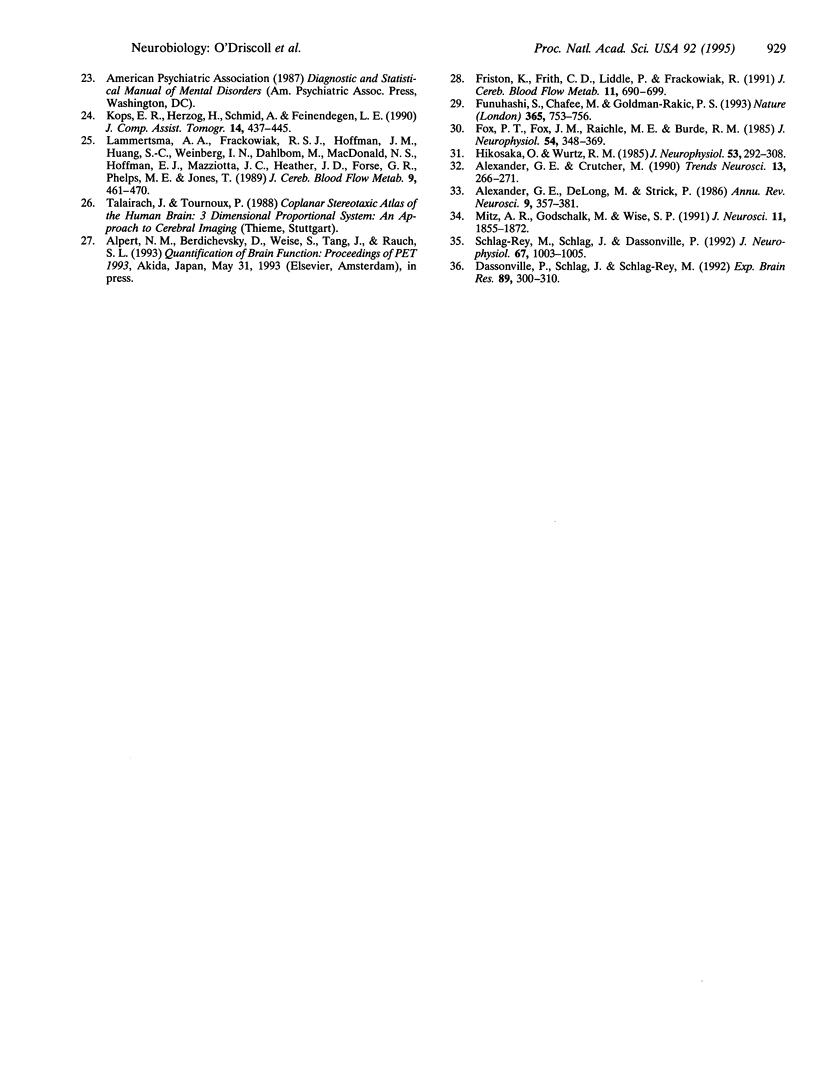

Increasing interest in the role of the frontal lobe in relation to psychiatric and neurologic disorders has popularized tests of frontal function. One of these is the antisaccade task, in which both frontal lobe patients and schizophrenics are impaired despite normal performance on (pro)saccadic tasks. We used position emission tomography to examine the cerebral blood flow changes associated with the performance of antisaccades in normal individuals. We found that the areas of the brain that were more active during antisaccades than saccades were highly consistent with the oculomotor circuit, including frontal eye fields (FEFs), supplementary motor area, thalamus, and putamen. Superior parietal lobe and primary visual cortex were also significantly more active. In contrast, prefrontal areas 46 and 9 were not more active during antisaccades than during saccades. Performance of some frontal patients on the antisaccade task has been likened to a bradykinesia, or the inability to initiate a willed movement. It is the necessity to will the movement and inhibit competing responses that intuitively linked this task to the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in frontal patients. Our data suggest that it is the FEFs in prefrontal cortex that differentiate between conditions in which the required oculomotor response changes while the stimulus remains the same, rather than areas 46 and 9, which, in human studies, have been linked to the performance of complex cognitive tasks. Such a conclusion is consistent with single-unit studies of nonhuman primates that have found that the FEFs, the executive portion of the oculomotor circuit, can trigger, inhibit, and set the target of saccades.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Alexander G. E., Crutcher M. D. Functional architecture of basal ganglia circuits: neural substrates of parallel processing. Trends Neurosci. 1990 Jul;13(7):266–271. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(90)90107-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander G. E., DeLong M. R., Strick P. L. Parallel organization of functionally segregated circuits linking basal ganglia and cortex. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1986;9:357–381. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.09.030186.002041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dassonville P., Schlag J., Schlag-Rey M. The frontal eye field provides the goal of saccadic eye movement. Exp Brain Res. 1992;89(2):300–310. doi: 10.1007/BF00228246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deiber M. P., Passingham R. E., Colebatch J. G., Friston K. J., Nixon P. D., Frackowiak R. S. Cortical areas and the selection of movement: a study with positron emission tomography. Exp Brain Res. 1991;84(2):393–402. doi: 10.1007/BF00231461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox P. T., Fox J. M., Raichle M. E., Burde R. M. The role of cerebral cortex in the generation of voluntary saccades: a positron emission tomographic study. J Neurophysiol. 1985 Aug;54(2):348–369. doi: 10.1152/jn.1985.54.2.348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friston K. J., Frith C. D., Liddle P. F., Frackowiak R. S. Comparing functional (PET) images: the assessment of significant change. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1991 Jul;11(4):690–699. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1991.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukushima J., Fukushima K., Morita N., Yamashita I. Further analysis of the control of voluntary saccadic eye movements in schizophrenic patients. Biol Psychiatry. 1990 Dec 1;28(11):943–958. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(90)90060-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukushima J., Morita N., Fukushima K., Chiba T., Tanaka S., Yamashita I. Voluntary control of saccadic eye movements in patients with schizophrenic and affective disorders. J Psychiatr Res. 1990;24(1):9–24. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(90)90021-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funahashi S., Chafee M. V., Goldman-Rakic P. S. Prefrontal neuronal activity in rhesus monkeys performing a delayed anti-saccade task. Nature. 1993 Oct 21;365(6448):753–756. doi: 10.1038/365753a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgopoulos A. P., Lurito J. T., Petrides M., Schwartz A. B., Massey J. T. Mental rotation of the neuronal population vector. Science. 1989 Jan 13;243(4888):234–236. doi: 10.1126/science.2911737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgopoulos A. P., Massey J. T. Cognitive spatial-motor processes. 1. The making of movements at various angles from a stimulus direction. Exp Brain Res. 1987;65(2):361–370. doi: 10.1007/BF00236309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg T. E., Berman K. F., Mohr E., Weinberger D. R. Regional cerebral blood flow and cognitive function in Huntington's disease and schizophrenia. A comparison of patients matched for performance on a prefrontal-type task. Arch Neurol. 1990 Apr;47(4):418–422. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1990.00530040062020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guitton D., Buchtel H. A., Douglas R. M. Frontal lobe lesions in man cause difficulties in suppressing reflexive glances and in generating goal-directed saccades. Exp Brain Res. 1985;58(3):455–472. doi: 10.1007/BF00235863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallett P. E., Adams B. D. The predictability of saccadic latency in a novel voluntary oculomotor task. Vision Res. 1980;20(4):329–339. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(80)90019-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallett P. E. Primary and secondary saccades to goals defined by instructions. Vision Res. 1978;18(10):1279–1296. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(78)90218-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hikosaka O., Sakamoto M., Usui S. Functional properties of monkey caudate neurons. I. Activities related to saccadic eye movements. J Neurophysiol. 1989 Apr;61(4):780–798. doi: 10.1152/jn.1989.61.4.780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hikosaka O., Wurtz R. H. Modification of saccadic eye movements by GABA-related substances. II. Effects of muscimol in monkey substantia nigra pars reticulata. J Neurophysiol. 1985 Jan;53(1):292–308. doi: 10.1152/jn.1985.53.1.292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonides J., Smith E. E., Koeppe R. A., Awh E., Minoshima S., Mintun M. A. Spatial working memory in humans as revealed by PET. Nature. 1993 Jun 17;363(6430):623–625. doi: 10.1038/363623a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaBerge D., Buchsbaum M. S. Positron emission tomographic measurements of pulvinar activity during an attention task. J Neurosci. 1990 Feb;10(2):613–619. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.10-02-00613.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lammertsma A. A., Frackowiak R. S., Hoffman J. M., Huang S. C., Weinberg I. N., Dahlbom M., MacDonald N. S., Hoffman E. J., Mazziotta J. C., Heather J. D. The C15O2 build-up technique to measure regional cerebral blood flow and volume of distribution of water. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1989 Aug;9(4):461–470. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1989.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lurito J. T., Georgakopoulos T., Georgopoulos A. P. Cognitive spatial-motor processes. 7. The making of movements at an angle from a stimulus direction: studies of motor cortical activity at the single cell and population levels. Exp Brain Res. 1991;87(3):562–580. doi: 10.1007/BF00227082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitz A. R., Godschalk M., Wise S. P. Learning-dependent neuronal activity in the premotor cortex: activity during the acquisition of conditional motor associations. J Neurosci. 1991 Jun;11(6):1855–1872. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-06-01855.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardo J. V., Pardo P. J., Janer K. W., Raichle M. E. The anterior cingulate cortex mediates processing selection in the Stroop attentional conflict paradigm. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990 Jan;87(1):256–259. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.1.256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paus T., Kalina M., Patocková L., Angerová Y., Cerný R., Mecir P., Bauer J., Krabec P. Medial vs lateral frontal lobe lesions and differential impairment of central-gaze fixation maintenance in man. Brain. 1991 Oct;114(Pt 5):2051–2067. doi: 10.1093/brain/114.5.2051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petit L., Orssaud C., Tzourio N., Salamon G., Mazoyer B., Berthoz A. PET study of voluntary saccadic eye movements in humans: basal ganglia-thalamocortical system and cingulate cortex involvement. J Neurophysiol. 1993 Apr;69(4):1009–1017. doi: 10.1152/jn.1993.69.4.1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierrot-Deseilligny C., Rivaud S., Pillon B., Fournier E., Agid Y. Lateral visually-guided saccades in progressive supranuclear palsy. Brain. 1989 Apr;112(Pt 2):471–487. doi: 10.1093/brain/112.2.471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posner M. I., Walker J. A., Friedrich F. J., Rafal R. D. Effects of parietal injury on covert orienting of attention. J Neurosci. 1984 Jul;4(7):1863–1874. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.04-07-01863.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rezai K., Andreasen N. C., Alliger R., Cohen G., Swayze V., 2nd, O'Leary D. S. The neuropsychology of the prefrontal cortex. Arch Neurol. 1993 Jun;50(6):636–642. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1993.00540060066020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rota Kops E., Herzog H., Schmid A., Holte S., Feinendegen L. E. Performance characteristics of an eight-ring whole body PET scanner. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1990 May-Jun;14(3):437–445. doi: 10.1097/00004728-199005000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlag-Rey M., Schlag J., Dassonville P. How the frontal eye field can impose a saccade goal on superior colliculus neurons. J Neurophysiol. 1992 Apr;67(4):1003–1005. doi: 10.1152/jn.1992.67.4.1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tien A. Y., Pearlson G. D., Machlin S. R., Bylsma F. W., Hoehn-Saric R. Oculomotor performance in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1992 May;149(5):641–646. doi: 10.1176/ajp.149.5.641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberger D. R., Berman K. F., Zec R. F. Physiologic dysfunction of dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in schizophrenia. I. Regional cerebral blood flow evidence. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1986 Feb;43(2):114–124. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1986.01800020020004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]