Abstract

Hypoxia plays a critical role in development and the wound healing process, as well as a number of pathological conditions. Here, we report dextran–based hypoxia–inducible (Dex–HI) hydrogels formed with in situ oxygen consumption via laccase–medicated reaction. Oxygen levels and gradients were accurately predicted by mathematical simulation. We demonstrate that Dex–HI hydrogels provide prolonged hypoxic conditions up to 12 h. The Dex–HI hydrogel offers an innovative approach to delineate not only the mechanism by which hypoxia regulates cellular responses, but may facilitate the discovery of new pathways involved in the generation of hypoxic and oxygen gradient environments.

Keywords: dextran, oxygen controllable hydrogels, injectable hydrogels, laccase-mediated crosslinking reaction, and hypoxia

Hydrogel materials have been increasingly utilized as engineered artificial microenvironments to recapitulate complex and dynamic in vivo environments due to their structural similarity and tunable properties.[1] In particular, in situ forming hydrogels have received much attention as a therapeutic delivery vesicle and a regenerative matrix for tissue regeneration, owing to easy application based on minimally invasive technique.[2] A representative natural polysaccharide, Dextran (Dex), has emerged as a material for in situ cross–linkable hydrogels for biomedical applications due to its properties, such as hydrophilicity, biocompatibility and biodegradability. Although numerous physical and chemical reactions (e.g., stereocomlexation[3], photo–polymerization[4], Michael–type addition[5], Diels–Alder reaction[6], and enzymatic reaction[7]) have been utilized to generate injectable Dex–based hydrogels, in situ oxygen (O2)–controllable Dex hydrogel materials have not been demonstrated.

It is well known that O2 plays a critical role in regulating cell metabolism, proliferation, and survival, as well as angiogenesis.[8] In particular, O2 depravation (below 5% partial pressure of O2, defined as hypoxia) is an important physiological signal, which presents in the native extracellular matrix (ECM) in various tissues.[9] In fact, O2 tension in the mammalian reproductive tract is in the range of 1.5–8%.[10] During embryonic development and adult tissue regeneration and remodeling, cellular differentiation is regulated by generation of hypoxic microenvironments.[11] Indeed, hypoxia occurs in pathological conditions, such as tissue ischemia and inflammation as well as in solid tumors.[12] Furthermore, hypoxia is a crucial physiological signal in wound healing and regeneration.[13] In fact, the O2 tension in the wound area decreases due to the disruption of the local microvasculature, which induces acute local hypoxia. Acute hypoxia plays a role as an important physiological signal during all phases of wound healing as it regulates cellular proliferation, migration, and differentiation through the induction of cytokines and diverse intracellular signaling pathways.[14] In order to activate downstream signaling pathways and to facilitate accumulation of relevant transcription factors, hypoxic conditions must be maintained for several hours (>1 hour).[15]

In a previous study, we reported a novel approach to generate hypoxia–inducible (HI) hydrogels through in situ O2 consumption in a laccase–mediated reaction.[16] We utilized gelatin–based HI (Gtn–HI) hydrogels as 3D artificial hypoxic microenvironments in vitro to promote vascular morphogenesis of endothelial progenitor cells. Also, we demonstrated that Gtn–HI hydrogels stimulated rapid neovascularization from the host during wound healing when injected in vivo. While through the previous study we established and confirmed the potential of HI hydrogels for hypoxia–related applications, O2 concentration and gradients over prolonged periods of time could only be achieved depending on non-material variables such as O2 consumption by encapsulated cells and O2 levels in surrounding tissue. This is probably due to the limited conjugation efficiency of phenolic molecules that can consume O2 during hydrogel formation. Controlling and maintaining prolonged hypoxic conditions will allow us to study and understand how varying hypoxic levels modulate cellular responses.

The goal of this study is to develop Dex–based HI (Dex–HI) hydrogels that can induce prolonged hypoxic conditions. We demonstrate in situ hydrogel formation kinetics with O2 consumption in a laccase–mediated crosslinking reaction and precise prediction of dissolved O2 (DO) levels and gradients within the HI hydrogels. To our knowledge, this is the first hydrogel material with precisely prolonged and controlled DO levels and gradients, which may induce prolonged hypoxic conditions (up to 12 hours), with potential for a wide range of hypoxia–related applications.

We hypothesized that conjugating tyramine (TA), as a phenolic moiety, to a Dex polymer backbone using polyethylene glycol (PEG) as a hydrophilic linker would allow us to fabricate a Dex–HI hydrogel by a laccase–mediated O2 consuming reaction. We selected Dex and PEG as the polymer backbone for their modifiability, bioactivity and hydrophilicity as well as the similarity of their properties to those of various soft tissues. In particular, we chose the Dex molecule because of its high content of hydroxyl functional groups that can be converted or modified easily with other molecules. A chain of Dex polymer includes three hydroxyl groups per repeat unit, which can allow for a high degree of substitution (DS) of target molecules.[7] In addition, Dex has excellent water solubility that enables easy control of the precursor solutions.

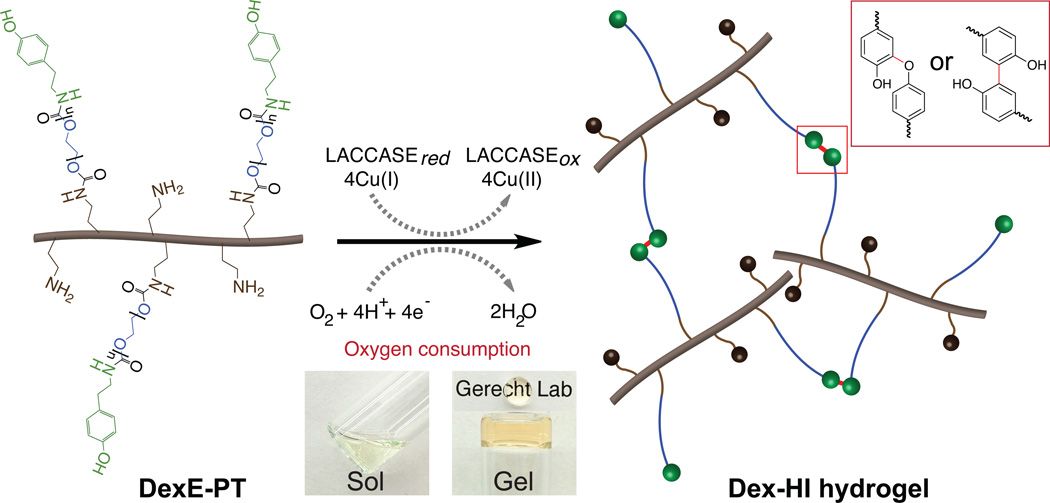

We synthesized Dex–HI hydrogels by conjugating TA molecules to Dex using PEG as a linker to enhance crosslinking reactivity in a laccase–mediated reaction. Following the Gtn–HI hydrogel synthesis procedure[16], we first attempted to generate Dex–HI hydrogels by conjugating ferulic acid (FA) to the Dex polymer backbone (DexFA) without the PEG linker. However, these attempts did not exhibit a phase transition from sol to gel during the laccase–mediated chemical reaction, even though Dex–FA exhibited a higher DS of FA (120.2 ± 0.7 µmol/g of polymer, DS120) compared to Gtn–FA molecules (44.70 ± 0.5 µmol/g of polymer, DS45). The phase transition may have been prevented by the molecular structure of the Dex polymer, as Dex has a relatively low molecular weight (~70 kDa) compared to Gtn molecular weight (~100 kDa) and decreased molecular mobility due to its more complex, branched molecular structure. The decreased molecular mobility of the Dex polymer may impede crosslinking reaction and gel formation. Thus, we introduced PEG as a hydrophilic linker between the Dex polymer backbone and the TA molecules to improve crosslinking reactivity, as we previously reported.[17] We synthesized Dex–HI hydrogels by conjugating primary amine groups of TA and aminated–Dex (DexE) using amine reactive PEG molecules (PEG–(PNC)2) to give DexE–PEG–TA (DexE–PT) (Figure S1) and characterized the chemical structure of the DexE–PT using a proton nuclear magnetic resonance (1H NMR) spectrometer, showing the specific peaks of the aromatic protons of TA (300 MHz, d2O, δ6.8–7.2 ppm), the methylene protons of PEG repeating units (300 MHz, d2O, δ3.4–3.8 ppm), and the anomeric protons of dextran repeating units (300 MHz, d2O, δ4.95 ppm) (Figure S2a–c). We also measured TA contents (170.8 ± 4.6 µmol/g of polymer, DS170) using a ultraviolet–visible (UV/Vis) spectrophotometry as previously described.[16–17] Notably, we found that while we used a lower feed amount of phenolic molecules (0.8 mmol of TA) for Dex–HI compared to that for Gtn–HI hydrogels (4.0 mmol of FA), phenolic content of Dex–HI was higher (170.8 ± 4.6 µmol/g of polymer) than that of Gtn–HI (44.70 ± 0.5 µmol/g of polymer) mostlikely due to its high content of functional groups as discussed above. We fabricated Dex–HI hydrogels through conjugation of TA molecules that yielded polymer networks in laccase–mediated reaction (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1. Dextran–based hypoxia–inducible hydrogels.

Schematic representation of Dex–HI hydrogel formation. Dex–HI hydrogels are prepared through an in situ O2 consuming in laccase–mediated reaction (inset micrographs of sol–gel transition of the transparent Dex–HI hydrogels). In this reaction, laccase catalyzes the reduction of O2 into water (H2O) molecules, resulting in conjugation of TA molecules through either carbon–carbon bonds at the ortho positions or carbon–oxygen bonds between the ortho carbon and the phenoxy oxygen (illustrated in RED box).

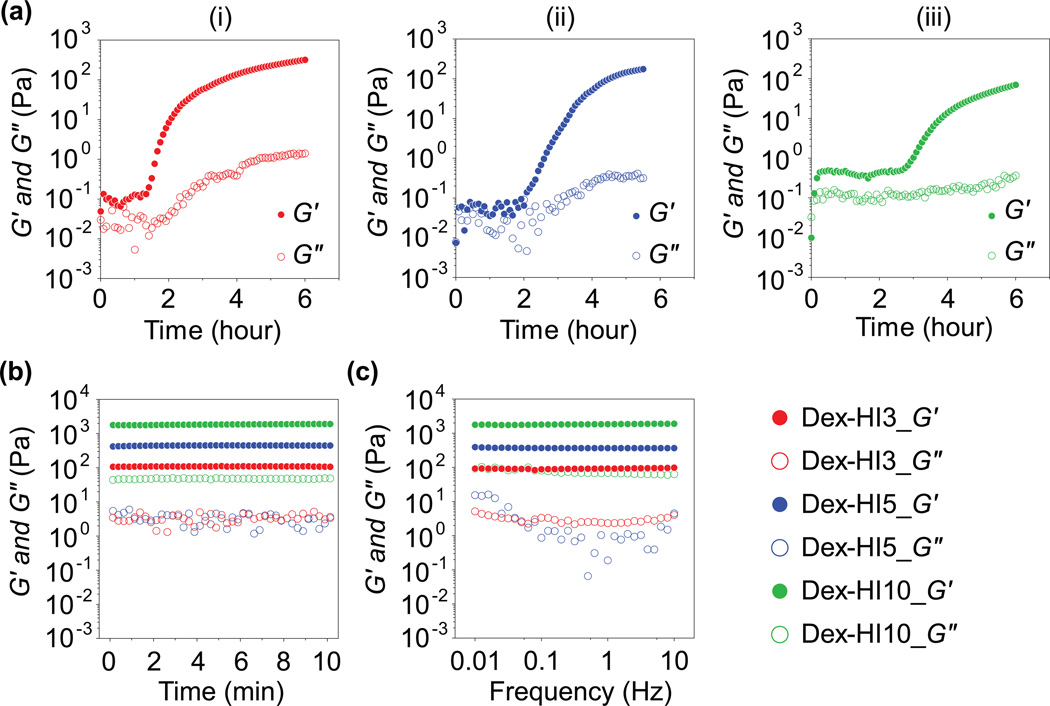

To assess the hydrogel formation kinetics and the mechanical properties of Dex–HI hydrogels, we performed rheological analyses, including dynamic time sweep and frequency sweep of hydrogels with varying polymer concentrations. Interestingly, as the polymer concentrations increased from 3 w/v% to 10 w/v%, hydrogels exhibited slower phase transition rate (Figure 1a). For example, G′ values of Dex–HI3 hydrogel increased dramatically after 1.3 hours, whereas G′ of Dex–HI10 hydrogels increased after 2.7 hours, suggesting that higher polymer concentrations induce slower hydrogel formation. These results could be explained by differences in O2 diffusivity of precursor solutions, since increasing polymer concentration induces lower O2 diffusion in the solutions (data not shown), resulting in a slower laccase–mediated crosslinking reaction. However, these slow phase transitions depending on polymer concentration might present some limitations of our hydrogel systems in specific applications. Toward this, Dex–HI hydrogels can be generated using lower molecular weight Dex (<70 kDa) and higher molecular weight PEG (>4 kDa) molecules to decrease polymer viscosity and to promote the crosslinking reactivity in future studies.

Figure 1. Hydrogel network formation kinetics and viscoelastic properties of Dex–HI hydrogels.

a) Viscoelastic modulus (G2, filled symbols; G3, open symbols) of Dex–HI hydrogels with dynamic time sweep. The rheological analysis shows dynamic network formation of Dex–HI hydrogels with different polymer concentrations; (i) Dex–HI3, (ii) Dex–HI5, and (iii) Dex–HI10. b) Dynamic time sweep at the equilibrium swelling state of hydrogels. The viscoelastic measurements exhibit the tunable mechanical properties of the Dex–HI hydrogels (Dex–HI3, 110 Pa; Dex–HI5, 450 Pa; Dex–HI10, 1840 Pa) by varying polymer concentrations. c) Dynamic frequency sweep at the equilibrium swelling state of hydrogels, showing hydrogel network stability after gelation.

In order to determine the effect of polymer concentration on the final mechanical strength of Dex–HI hydrogels, we performed a dynamic time sweep at the equilibrium swelling state. Viscoelastic measurements exhibited tunable mechanical properties of the Dex–HI hydrogels (Dex–HI3, 110 Pa; Dex–HI5, 450 Pa; Dex–HI10, 1840 Pa) by varying polymer concentrations (Figure 1b). To confirm stability of the hydrogel network formation, we also measured viscoelastic properties with a dynamic frequency sweep (0.01–10 Hz). We observed that increasing frequency did not affect the elastic modulus (Figure 1c), demonstrating that the hydrogel network structures of Dex–HI hydrogels are stable after hydrogel formation. Taken together, we demonstrated that the Dex–HI hydrogels were successfully prepared with tunable mechanical properties, as well as the stable network formations. The physicochemical properties of Dex–HI hydrogels were summarized in table 1.

Table 1.

Hydrogel preparation and characterizations.

| Sample | Polymer conc. (w/v%) |

TA Conc. (mM) |

Michaelis-Meten parameters | Elastic modulus (G′, Pa) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Vmax (µM sec−1) |

Km (µM) |

||||

| Dex-HI3 | 3 | 5.1 | 0.26 | 64.82 | 110 |

| Dex-HI5 | 5 | 8.5 | 0.26 | 73.93 | 450 |

| Dex-HI10 | 10 | 17.0 | 0.33 | 98.86 | 1840 |

In addition to rheological analysis, we examined the biocyocompatibility of the DexE–PT polymer using human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs). We observed no significant cytotoxicity in the polymer (day 1, 100 ± 9.1 % of control; day 3, 114.7 ± 8.6 % of control) and the cells proliferated well up to day 3 (Figure S3a–b). This result demonstrated that our DexE–PT polymer is cytocompatible and hence, has potential for in vivo applications.

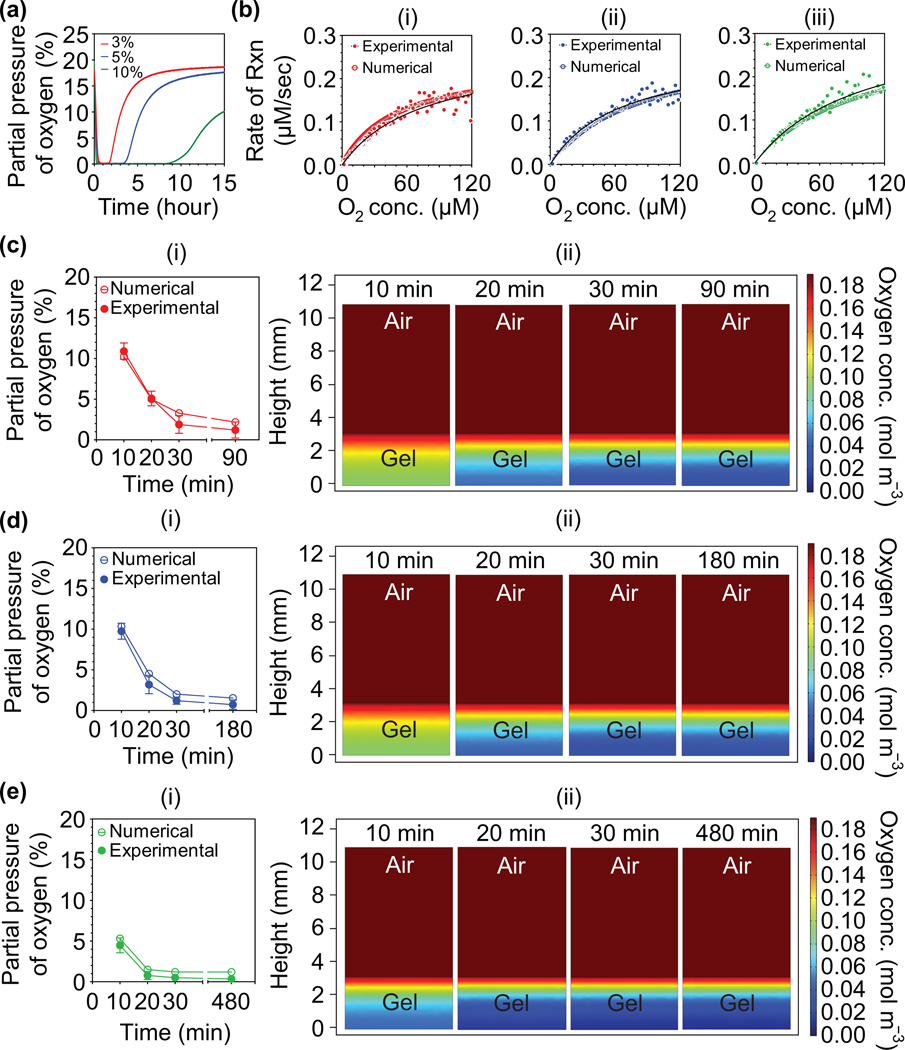

To determine accurate O2 levels, we measured DO levels within Dex–HI hydrogels using a noninvasive O2 patch and simulated a DO gradient within the hydrogels through mathematical model prediction using the Michealis–Menten equation, as we previously reported.[16, 18] DO levels decreased dramatically during the initial 30 minutes, and maintained low O2 tension (<0.5%, defined as the steady state) up to 1.5 hours for Dex–HI3, 3 hours for Dex–HI5, and 8 hours for Dex–HI10, suggesting an ongoing chemical reaction. After steady state was reached, the DO levels increased gradually, demonstrating that the chemical reaction was complete. We also found that the higher polymer concentrations induce rapid O2 consumption and maintain prolonged hypoxic conditions. For example, as polymer concentrations were increased from 3 w/v% (Dex–HI3) to 10 w/v% (Dex–HI10), the hydrogels showed faster O2 consumption rate during the initial 30 minutes and longer hypoxic conditions (up to 12 hours) (Figure 2a). This pattern was expected because TA contents that can consume O2 molecules increased from 5.1 mM to 17.0 mM, which induce a much faster chemical reaction. Importantly, we found that Dex–HI hydrogels generated longer hypoxic conditions (up to 12 hours) compared to Gtn–HI hydrogels (up to 1 hour;[16]). This is a meaningful advantage of Dex–HI hydrogels as prolonged hypoxic conditions promote accumulation and stabilization of HIFs, which regulate myriad gene expression affecting cellular activities.[9b, 11, 19] The prolonged hypoxic conditions in the Dex–HI can be achieved based on the chemical reaction parameters and thus can be easily tuned.

Figure 2. O2 measurements and model predictions of DO levels in Dex-HI hydrogels.

a) DO levels at the bottom of Dex–HI hydrogels (3–10 w/v%, 3.13 mm thickness, and 25 U mL−1 laccase) as a function of time. b) Model prediction of DO levels at the bottom of hydrogels with different polymer concentrations; (i) Dex–HI3, (ii) Dex–HI5, and (iii) Dex–HI10. O2 consumption rate of laccase–mediated crosslinking reactions follows Michaelis–Menten equation. c–e) Model prediction and computer simulation of DO levels and gradient. We compared model numerical prediction (open symbols) and the experimental values (filled symbols) to confirm the reliability of the given Vmax and Km values; c(i) Dex–HI3, d(i) Dex–HI5, and e(i) Dex–HI10. Simulation of DO gradient within the hydrogels in the two–layer model (air–hydrogel) as a function of time; c(ii) Dex–HI3, d(ii) Dex–HI5, and e(ii) Dex–HI10.

To simulate DO levels and gradients within Dex–HI hydrogels, we used a mathematical model developed in our previous studies.[16, 18] We assumed that O2 consumption kinetics during hydrogel formation follow Michaelis–Menten kinetics (Equation 1). To accurately estimate DO gradients within Dex–HI hydrogels, we first determined the Michaelis–Menten parameter values (defined as Vmax and Km). We measured DO levels at the bottom of hydrogels (3, 5, and 10 w/v%, DS170, and 25 U mL−1 laccase) until they reached steady state. We then plotted the O2 consumption rate of the laccase–mediated reaction (defined as experimental data) and the theoretical Michaelis–Menten equation (defined as a numerical model) using the initial Vmax and Km values. We then used GraphPad Prism 4.02 to determine the best fit for the experimental values of DO (Figure 2b).The curve fitting suggested that O2 consumption kinetics follow the theoretical Michaelis–Menten equation. We determined that the Vmax and Km values of Dex–HI hydrogels were 0.26 µM sec−1 and 64.82 µM for Dex–HI3, 0.26 µM sec−1 and 73.93 µM for Dex–HI5, and 0.33 µM sec−1 and 98.86 µM for Dex–HI10, respectively. Interestingly, we found that the Vmax values of Dex–HI hydrogels were lower than that of Gtn–HI hydrogels (0.43 µM sec−1) even though Dex–HI hydrogels contain higher concentrations of phenolic molecules (5.1–17.0 mM) compared to Gtn–HI hydrogels (1.35 mM). This is because the O2 consumption rate of the laccase–mediated reaction using FA is faster than that of the enzymatic reaction using TA molecules.[20] Overall, although Gtn–HI hydrogels showed faster Vmax values, Dex–HI hydrogels exhibit lower O2 levels and prolonged hypoxic environments due to the high content of phenolic molecules that can consume O2 during hydrogel formation.

To confirm the reliability of the given Michaelis–Menten parameters, we compared the experimental values and numerical values at different time points up to the end of the steady state. As shown in Figure 2c–e, the experimental values are similar to the values of the numerical model predicted by using the given parameters. These results demonstrated that the kinetics of the laccase–mediated chemical reaction follows the theoretical equation. We also found that increasing polymer concentration induced lower O2 levels (Dex–HI3, 1.2 ± 1.1%; Dex–HI5, 1.2 ± 0.4%; Dex–HI10, 0.5 ± 0.4%) and a broad range of O2 gradient after 30 minutes (Dex–HI3, 1.2%–20.3%; Dex–HI5, 1.2%–20.0%; Dex–HI10, 0.5%–20.3%). Dex–HI hydrogels exhibited lower O2 levels and a wider range of O2 gradient compared to Gtn–HI hydrogels (O2 levels at the bottom of Gtn–HI hydrogel; 1.8%; O2 gradient, 1.8–21%[16]).

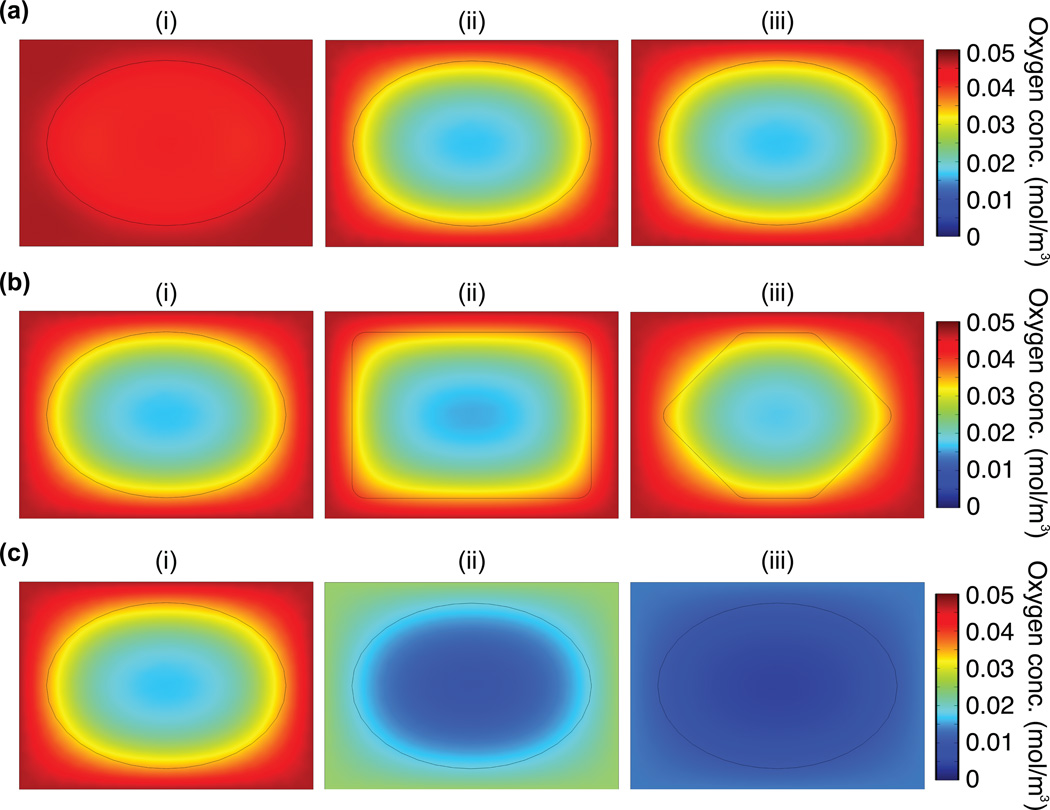

Using the given parameters, we estimated DO levels and gradients after theoretical in vivo injection of Dex–HI10 hydrogels. We first simulated DO levels at different time points up to 8 hours (the end of the steady state of Dex–HI10). For this model prediction, we assumed a partial pressure of O2 (pO2)in subcutaneous tissue of 40 mmHg, following previous reports.[10, 21] As can be seen Figure 3a, the DO gradient from the core to the interface between the hydrogel and the tissue decreased during the initial 30 minutes:10 minutes after injection, DO level of the hydrogel core is 4.3 × 10−2 mol m−3 and the DO level of the interface is 4.5 × 10−2 mol m−3; 30 minutes after injection, DO levels of the hydrogel core is 1.6 × 10−2 mol m−3 and the DO level of the interface is 3.6 × 10−2 mol m−3). Moreover, low O2 levels were maintained for up to 8 hours where DO level of the hydrogel core is 1.6 × 10−2 mol m−3; DO level of the interface is 3.6 ×10−2 mol m−3. After 8 hours, the DO levels may increase gradually, possibly through increased O2 diffusion as the chemical reaction is completed as mentioned above, suggesting that the hypoxic effects may be diminished after this time point. We also simulated DO levels with different hydrogel geometries (e.g., ellipse, rectangle, and polygonal shape), as we needed to consider that the hydrogels form irregular shapes following injection into dynamic in vivo environments. We found that after 30 minutes, the DO gradient within the hydrogels was independent of the hydrogel geometry (Figure 3b). We then simulated the O2 gradients upon theoretical injection into tissue with pathological O2 levels (< 40 mmHg) that are already ischemic and hence, hypoxic. Notably, we observed that DO levels at the edge of the hydrogels were lower than the surrounding in vivo environment (Figure 3b). Taken together, these results suggest that Dex–HI hydrogels can induce an acute hypoxic environment (up to 12 hours) that can stimulate surrounding tissues in dynamic in vivo environments.

Figure 3. Model prediction of the DO levels of Dex–HI hydrogel in in vivo environments.

a) Model prediction of DO gradient at different time points in physiological in vivo conditions (pO2, 40 mmHg): (i) after 10 minutes of injection (DO levels of the hydrogel core, 4.3 × 10−2 mol m−3; DO levels of the interface, 4.5 × 10−2 mol m−3), (ii) after 30 minutes of injection (DO levels of the hydrogel core, 1.6 × 10−2 mol m−3; DO levels of the interface, 3.6 × 10−2 mol m−3); (iii) after 8 hours of injection (DO levels of the hydrogel core, 1.6 × 10−2 mol m−3; DO levels of the interface, 3.6 ×10−2 mol m−3). b) Model prediction of DO gradients within the Dex–HI hydrogels after 1 hour of injection in physiological in vivo conditions (pO2, 40 mmHg) depending on their shape: (i) ellipse, (ii) rectangle, and (iii) polygonal shapes. c) DO gradients of the ellipse–shaped Dex–HI hydrogels after 1 hour of injection in different pO2 environments: (i) 40 mmHg (DO levels of the hydrogel core, 1.6 × 10−2 mol m−3; DO levels of the interface, 3.4 × 10−2 mol m−3), (ii) 20 mmHg (DO levels of the hydrogel core, 7.8 × 10−3 mol m−3; DO levels of the interface, 1.8 × 10−2 mol m−3), and (iii) 10 mmHg (DO levels of the hydrogel core, 3.7 × 10−3 mol m−3; DO levels of the interface, 9.0 × 10−3 mol m−3).

In the present study, we present in situ crosslinkable Dex–HI hydrogels as injectable O2 controlling materials that can induce an acute hypoxic condition upto 12 h. We successfully synthesized Dex–HI hydrogels via an in situ O2 consuming in laccase–mediated reaction and characterized the kinetics of hydrogel network formation as they changed with increasing polymer concentrations. We can accurately predict O2 levels and gradients within the Dex–HI hydrogel matrix using mathematical modeling. Varying polymer concentrations enabled control of O2 levels and gradients within the hydrogels. Finally, our unique conjugation system allowed us to generate the Dex–HI hydrogels, which can induce acute hypoxic conditions up to 12 h, and may stimulate the surrounding tissues in dynamic in vivo environments. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first Dex–based injectable biomaterial, which is capable of controlling or manipulating prolonged hypoxia. Although hypoxia has been shown to play a pivotal role in many developmental and regenerative processes as well as in some diseased tissues, research in vivo has been largely limited to genetic manipulation of the signaling cascade. The Dex–HI hydrogel provides an innovative approach to delineate not only the mechanism by which hypoxia regulates these cellular responses, but may facilitate the discovery of new pathways involved in the generation of hypoxic and O2 gradient environments. In future studies, we will assess in vivo O2 levels after injection by using needle–type O2 sensors and investigate the effect of the acute hypoxic conditions generated by the Dex–HI hydrogels on the hypoxia–related signaling pathways of surrounding tissues.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NIH grants R01HL107938 and U54CA143868 and National Science Foundation grant 1054415 (to S.G).

Footnotes

Supporting Information

Supporting Information is available from the Wiley Online Library or from the author.

References

- 1.a) Cushing MC, Anseth KS. Science. 2007;316:1133. doi: 10.1126/science.1140171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Place ES, Evans ND, Stevens MM. Nat. Mater. 2009;8:457. doi: 10.1038/nmat2441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Annabi N, Tamayol A, Uquillas JA, Akbari M, Bertassoni LE, Cha C, Camci-Unal G, Dokmeci MR, Peppas NA, Khademhosseini A. Adv. Mater. 2014;26:85. doi: 10.1002/adma.201303233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Malda J, Visser J, Melchels FP, Jungst T, Hennink WE, Dhert WJ, Groll J, Hutmacher DW. Adv. Mater. 2013;25:5011. doi: 10.1002/adma.201302042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Thiele J, Ma Y, Bruekers SM, Ma S, Huck WT. Adv. Mater. 2014;26:125. doi: 10.1002/adma.201302958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ko DY, Shinde UP, Yeon B, Jeong B. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2013;38:672. [Google Scholar]

- 3.De Jong S, De Smedt S, Demeester J, Van Nostrum C, Kettenes-Van Den Bosch J, Hennink W. J. Controlled Release. 2001;72:47. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(01)00261-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.a) Sun G, Shen YI, Kusuma S, Fox-Talbot K, Steenbergen CJ, Gerecht S. Biomaterials. 2011;32:95. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.08.091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Sun G, Zhang X, Shen YI, Sebastian R, Dickinson LE, Fox-Talbot K, Reinblatt M, Steenbergen C, Harmon JW, Gerecht S. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2011;108:20976. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1115973108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Peng G, Wang J, Yang F, Zhang S, Hou J, Xing WL, Lu X, Liu CS. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2013;127:577. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wei Z, Yang JH, Du XJ, Xu F, Zrinyi M, Osada Y, Li F, Chen YM. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2013;34:1464. doi: 10.1002/marc.201300494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jin R, Hiemstra C, Zhong Z, Feijen J. Biomaterials. 2007;28:2791. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.02.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Semenza GL. Science. 2007;318:62. doi: 10.1126/science.1147949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.a) Simon MC, Keith B. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2008;9:285. doi: 10.1038/nrm2354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Keith B, Simon MC. Cell. 2007;129:465. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fischer B, Bavister BD, Reprod J. Fertil. 1993;99:673. doi: 10.1530/jrf.0.0990673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Semenza GL. Trends Mol. Med. 2001;7:345. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4914(01)02090-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maltepe E, Simon MC. J. Mol. Med. 1998;76:391. doi: 10.1007/s001090050231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.a) LaVan FB, Hunt TK. Clin. Plast. Surg. 1990;17:463. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Du J, Liu L, Lay F, Wang Q, Dou C, Zhang X, Hosseini SM, Simon A, Rees DJ, Ahmed AK, Sebastian R, Sarkar K, Milner S, Marti GP, Semenza GL, Harmon JW. Gene Ther. 2013;20:1070. doi: 10.1038/gt.2013.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.a) Hong WX, Hu MS, Esquivel M, Liang GY, Rennert RC, McArdle A, Paik KJ, Duscher D, Gurtner GC, Lorenz HP. Adv. Wound Care. 2014 doi: 10.1089/wound.2013.0520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) O'Toole EA, Marinkovich MP, Peavey CL, Amieva MR, Furthmayr H, Mustoe TA, Woodley DT. J. Clin. Invest. 1997;100:2881. doi: 10.1172/JCI119837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stroka DM, Burkhardt T, Desbaillets I, Wenger RH, Neil DAH, Bauer C, Gassmann M, Candinas D. FEBS J. 2001;15:2445. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0125com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Park KM, Gerecht S. Nat. Commun. 2014;5:4075. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Park KM, Ko KS, Joung YK, Shin H, Park KD. J. Mater. Chem. 2011;21:13180. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abaci HE, Truitt R, Tan S, Gerecht S. Am. J. Physiol.: Cell Physiol. 2011;301:C431. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00074.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.a) Heddleston JM, Li Z, Lathia JD, Bao S, Hjelmeland AB, Rich JN. Br. J. Cancer. 2010;102:789. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Mazumdar J, Dondeti V, Simon MC. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2009;13:4319. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2009.00963.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mattinen ML, Kruus K, Buchert J, Nielsen JH, Andersen HJ, Steffensen CL. FEBS J. 2005;272:3640. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2005.04786.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang YN, Wilson GS. Anal. Chim. Acta. 1993;281:513. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.