Abstract

Background

The purported advantage of ABO-incompatible (ABO-I) listing is to reduce wait times and wait-list mortality among infants awaiting heart transplantation. We sought to describe recent trends in ABO-I listing for US infants and to determine the impact of ABO-I listing on wait times and wait-list mortality.

Methods and Results

In this multicenter retrospective cohort study using Organ Procurement and Transplant Network data, infants <12 months of age listed for heart transplantation between 1999 and 2008 (n=1331) were analyzed. Infants listed for an ABO-I transplant were compared with a propensity score–matched cohort listed for an ABO-compatible transplant through the use of a Cox shared-frailty model. The primary end point was time to heart transplantation. The percentage of eligible infants listed for an ABO-I heart increased from 0% before 2002 to 53% in 2007 (P<0.001 for trend). Compared with infants listed exclusively for an ABO-compatible heart, infants with a primary ABO-I listing strategy (n=235) were more likely to be listed 1A, to have congenital heart disease and renal failure, and to require extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. For the propensity score–matched groups (n=197 matched pairs), there was no difference in wait-list mortality; however, infants with blood type O assigned an ABO-I listing strategy were more likely to undergo heart transplantation by 30 days (31% versus 16%; P=0.007) with a less pronounced effect for infants with other blood types.

Conclusions

The proportion of US infants listed for an ABO-I heart transplantation has risen dramatically in recent years but still appears to be preferentially used for sicker infant candidates. The ABO-I listing strategy is associated with a higher likelihood of transplantation within 30 days for infants with blood group O and may benefit a broader range of transplantation candidates.

Keywords: heart defects, congenital heart failure, immunology, pediatrics, transplantation

Infants listed for heart transplantation (HT) face the single highest waiting list mortality rate compared with all other age groups listed for HT in the United States.1,2 Because a growing number of studies are reporting posttransplantation outcomes for infants receiving an ABO blood group–incompatible (ABO-I) donor heart that are similar to those receiving an ABO-compatible (ABO-C) donor heart,3–7 the number of infants assigned an ABO-I HT listing strategy nationwide has purportedly surged. This listing strategy allows infants to receive offers for a heart from an ABO-I donor in addition to offers for the ABO-C donor hearts that they remain eligible to receive.

Limited information is available on the actual trends in ABO-I listing among US transplant centers since the first deliberate ABO-I HT was performed in the United States in 2002. Moreover, although the purported advantage of ABO-I HT listing is to reduce waiting list times, and by extension waiting list mortality, limited data are available on whether there has been an actual reduction in wait times for a donor organ or the secondary impact on waiting list mortality.8 One of the primary threats to validity is selection bias introduced by the confounding effect of illness severity on the association between ABO-I transplant listing and waiting list mortality,3 given that until recently ABO-I listing has generally been reserved for the sickest infants. Nevertheless, a more precise estimate of the actual reduction in waiting time would be helpful not only to better characterize the risk-benefit profile of this emerging treatment strategy but also to examine the role of candidate blood type on the benefit of the ABO-I listing strategy. Therefore, the primary purposes of this study were to describe recent trends in ABO-I listing among US transplant programs and to estimate the impact of ABO-I listing on organ wait times and waiting list mortality after adjustment for patient differences.

Methods

Study Population and Data Source

All children <12 months of age listed for first orthotopic HT in the United States between January 1, 2000 (2 years before the first ABO-I HT was performed in the United States), and August 20, 2008, were identified retrospectively through the Organ Procurement and Transplant Network (OPTN). The OPTN is an internally audited, mandatory, government-sponsored solid-organ transplant registry that collects information on all solid-organ transplants in the United States. Demographic and clinical information is reported by transplanting centers to the OPTN. Patients with blood type AB and those listed for heart retransplantation or multiviscera transplant were excluded. All patients were followed up from the time of listing for HT until removal from the waiting list because of transplantation, death, or recovery or on the day of last observation (August 20, 2008).

Study Definitions and Outcome Measures

The primary study hypothesis was that infants assigned an ABO-I listing strategy have shorter HT waiting times compared with infants assigned an ABO-C listing strategy after adjustment for patient characteristics. For the propensity analysis, ABO-I listing strategy was defined as infants listed as eligible to receive a potential ABO-I HT at the time of initial listing as recorded by the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS). This group was compared with infants assigned an ABO-C listing strategy, defined as infants listed as eligible to receive a heart exclusively from an ABO-C donor throughout the duration of their wait period. Time on the waiting list was defined as the duration from initial listing for HT to the time of removal from the waiting list because of transplantation, death, or recovery. Subjects were censored at the time of death or recovery or on August 20, 2008, the last day of the study. A secondary composite outcome of death on the waiting list or removal from the waiting list because of clinical deterioration was also assessed.

All clinical and demographic variables were defined at the time of listing for HT unless otherwise specified. UNOS listing status was defined as 1A (highest urgency), 1B, and 2 according to revised criteria adopted by UNOS in 1999.9 The level of hemodynamic support was defined as extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), ventilator, or neither. Race/ethnicity data (categories included black, white, Hispanic, Asian, American Indian/Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, multiracial, and other) were analyzed as reported by the transplanting center. Glomerular filtration rate was estimated with the Schwartz formula.10

Statistical Analysis

Summary statistics are presented as median (first and third quartiles) or number (percent). Baseline patient characteristics were compared between infants listed for a potential ABO-I HT on day of listing and those listed exclusively for an ABO-C HT using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test for continuous variables and the χ2 test for categorical variables. As a result of an imbalance in baseline characteristics between the 2 groups and to avoid potential selection bias, a propensity score–matched pair analysis was then performed.11 For this analysis, a multivariable logistic regression model using 12 patient variables at listing (age, weight, year, race/ethnicity, listing status, diagnosis, sternotomy, inotrope, ventilator, ECMO, prostaglandin, dialysis) with the outcome “ABO-I listing strategy” was used to generate a propensity score (the probability of being assigned an ABO-I listing strategy) for each infant in the entire cohort. Infants assigned an ABO-C listing strategy (ie, those never assigned an ABO-I listing strategy at any time while on the waiting list) were matched to those assigned an ABO-I listing strategy using an optimal matching algorithm without replacement stratified by blood type; the difference in propensity scores between matched infants could not exceed 0.05. The matched groups were compared for baseline characteristics through the use of conditional logistic regression. The impact of listing strategy on clinical outcomes was assessed with a Cox shared-frailty model (assuming a γ distribution) that accounted for the propensity matching. The proportion of patients who died, were transplanted, recovered, or remained on the waiting list at 30 and 90 days past listing were displayed for the matched groups as competing risks graphs. All tests were 2 sided. The expected probability of ABO-I HT was calculated as the product of the probability of transplantation and the probability of receiving an ABO-I organ conditional on being transplanted for each blood type. The data were analyzed with SAS version 9.1 statistical software (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC) and STATA version 10.0 (StataCorp LP, College Station, Tex).

The authors had full access to and take responsibility for the integrity of the data. All authors have read and agree to the manuscript as written.

Results

Study Cohort

Between January 2000 and August 2008, 1382 infants were listed in the United States for primary HT. Of these, 51 infants were excluded because of AB blood type. The remaining 1331 infants formed the study cohort. Of these, 235 inants (17.7%) were assigned an ABO-I listing strategy at the time of initial listing, and 313 (23.5%) were listed for ABO-I HT at some point during their waiting period. The proportion of infants assigned an ABO-I listing strategy did not differ by blood type (17.4% of infants with blood type A and O, 19.5% of infants with blood type B), nor did the proportion of infants “ever assigned” an ABO-I listing strategy vary by blood type.

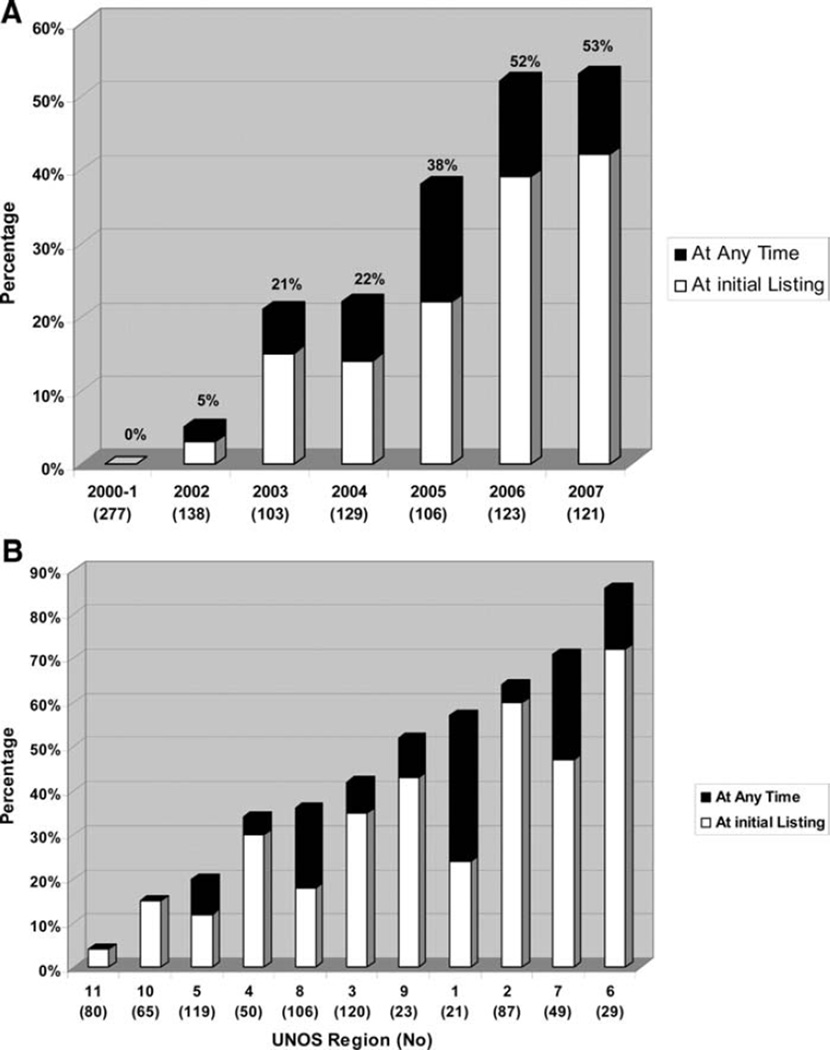

Figure 1 summarizes the US trends in the ABO-I listing of infant HT candidates during the 8-year study period by time and by geographic region. For patients <6 months of age (a cohort presumed immunologically eligible for an ABO-I listing strategy), the proportion of infants assigned an ABO-I listing strategy increased steadily from 0 before 2002 to just over 50% in 2006 and 2007 (P<0.001 for trend) (Figure 1A). There was a substantial variation by geographic (UNOS) region in the clinical practice of listing infants for a potential ABO-I HT, ranging from 4% to 86% (Figure 1B). For infants listed status 1A, the prevalence of ABO-I listing was higher, especially for infants listed since 2004 (data not shown).

Figure 1.

US trends in ABO-I listing of infants <6 months of age (age at which infants are generally presumed immunologically eligible for ABO-I HT) awaiting HT by year (A) and by region (B).

Table 1 summarizes the baseline characteristics of the study cohort according to ABO listing strategy at the time of HT listing. For all infants, the median age at listing was 57 days (quartiles 1 and 3, 11 and 157 days), and the median weight was 4.0 kg (quartiles 1 and 3, 3.2 and 5.6 kg); 603 (45.3%) were female, and 553 (41.5%) were nonwhite. The primary cardiac diagnosis leading to HT listing was congenital heart disease in 855 (64.2%; of whom 172 [12.9%] were on prostaglandin E and 385 [28.9%] had a prior surgical repair reported) and cardiomyopathy in 329 (24.7%). Overall, 265 (19.9%) were supported on ECMO, and 441 (33.1%) were supported on mechanical ventilation. Comparing the 2 cohorts showed that infants assigned an ABO-I listing strategy were significantly younger, smaller, more likely to be supported with ECMO, more likely to be listed as status 1A, and less likely to be receiving prostaglandin E than infants assigned an ABO-C listing strategy (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Patients

| Variable | ABO-I Group (n=235), % |

ABO-C Group (n=1096), % |

P |

|---|---|---|---|

| *Median (first to third quartiles). | |||

| Age, mo* | 1 (0–3) | 2 (0–5) | <0.001 |

| <1 | 51 | 40 | <0.001 |

| 1–2 | 18 | 18 | |

| 3–5 | 18 | 19 | |

| ≥6 | 12 | 23 | |

| Weight, kg* | 3.6 (3.0–4.9) | 4.0 (3.2–5.7) | <0.001 |

| Weight categories, kg | 0.01 | ||

| <3 | 20 | 14 | |

| 3–5 | 66 | 64 | |

| ≥6 | 14 | 22 | |

| Female | 49 | 45 | 0.28 |

| Nonwhite race | 38 | 42 | 0.27 |

| UNOS listing status | 0.001 | ||

| 1A | 90 | 80 | |

| 1B | 6 | 9 | |

| 2 | 4 | 11 | |

| Cardiac diagnosis | <0.001 | ||

| 21 | 31 | ||

| Cardiomyopathy/myocarditis | |||

| CHD | |||

| PGE | 5 | 15 | |

| Repair reported | 42 | 21 | |

| Repair not reported | 23 | 27 | |

| Other | 9 | 6 | |

| Blood type | 0.79 | ||

| A | 35 | 35 | |

| B | 14 | 12 | |

| O | 51 | 52 | |

| Invasive hemodynamic support | <0.001 | ||

| ECMO support | 37 | 16 | |

| Ventilator support | 27 | 34 | |

| Neither | 36 | 49 | |

| Inotropic support | 50 | 56 | 0.11 |

| Dialysis | 5 | 2 | 0.02 |

| Creatinine, mg/dL* | 0.5 (0.3–0.7) | 0.4 (0.3–0.6) | 0.16 |

| GFR <50 mL/1.73 m2 | 53 | 42 | 0.004 |

| Year of listing | <0.001 | ||

| 2000–2003 | 9 | 51 | |

| 2004–2008 | 91 | 49 |

CHD indicates congenital heart disease; PGE, prostaglandin E infusion; and GFR, glomerular filtration rate.

Median (first to third quartiles).

The median follow-up of the entire study cohort was 32 days (quartiles 1 and 3, 11 and 77 days), during which time 49% were transplanted, 20% died, 9% recovered, and 7% remained listed and waiting. Overall, 28% patients reached the composite secondary end point of death or delisting because of clinical deterioration. The median time to transplantation was 69 days (quartiles 1 and 3, 25 and 460 days) and was longer for infants with blood type O compared with infants with blood type A or B.

Table 2 compares baseline characteristics of 197 pairs of patients matched by their propensity for ABO-l listing and by their blood type. Of these, 108 pairs (55%) had blood type O, 68 (35%) had blood type A, and 21 (11%) had blood type B. There were no significant differences in baseline characteristics between the ABO-I and ABO-C matched cohorts. No match could be found for 38 infants listed for ABO-I HT who were likely to be younger and to have congenital heart disease and more likely to require ECMO support at the time of listing because there were insufficient patients in ABO-C group with this prognostic profile. Thus, these patients were not included in the outcome analysis of the propensity-matched cohorts.

Table 2.

Baseline Characteristics of the Propensity-Matched Patients

| Variable | ABO-I Group (n=197), % | ABO-C Group (n=197), % | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| *Median (first to third quartiles). | |||

| Age, mo* | 1 (0–4) | 1 (0–4) | 0.27 |

| <1 | 49 | 45 | 0.66 |

| 1–2 | 17 | 21 | |

| 3–5 | 20 | 19 | |

| ≥6 | 14 | 15 | |

| Weight, kg* | 3.7 (3.0–5.0) | 3.9 (3.1–5.3) | 0.30 |

| Weight categories, kg | 0.63 | ||

| <3 | 20 | 17 | |

| 3–5 | 65 | 64 | |

| ≥6 | 15 | 18 | |

| Female | 49 | 53 | 0.44 |

| Nonwhite race | 37 | 43 | 0.26 |

| UNOS listing status | 0.60 | ||

| 1A | 89 | 91 | |

| 1B | 6 | 6 | |

| 2 | 5 | 3 | |

| Cardiac diagnosis | 0.80 | ||

| Cardiomyopathy/myocarditis | 22 | 25 | |

| CHD | |||

| PGE | 6 | 5 | |

| Repair reported | 39 | 39 | |

| Repair not reported | 26 | 26 | |

| Other | 7 | 5 | |

| Invasive hemodynamic support | 0.55 | ||

| ECMO support | 33 | 29 | |

| Ventilator support | 29 | 32 | |

| Neither | 38 | 39 | |

| Inotropic support | 53 | 58 | 0.26 |

| Dialysis | 6 | 3 | 0.19 |

| GFR <50 mL/1.73 m2 | 51 | 46 | 0.48 |

| Year of listing | 0.59 | ||

| 1999–2003 | 11 | 12 | |

| 2004–2008 | 89 | 88 |

Abbreviations as in Table 1.

Median (first to third quartiles)

Outcome for Matched Cohorts

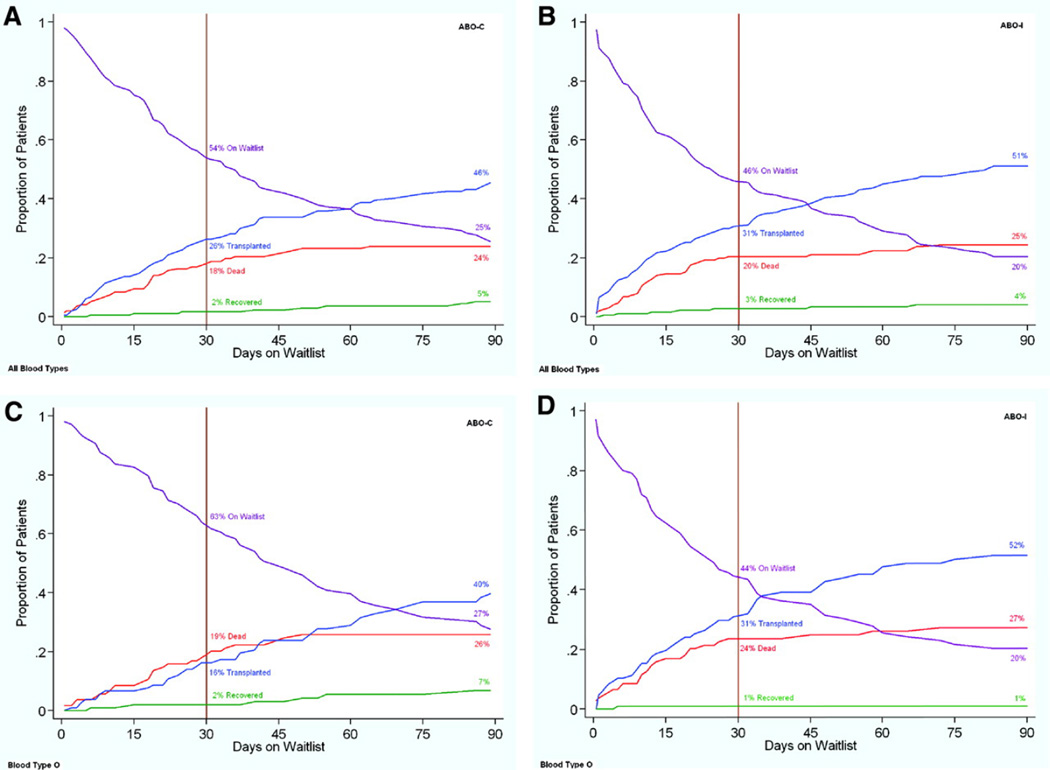

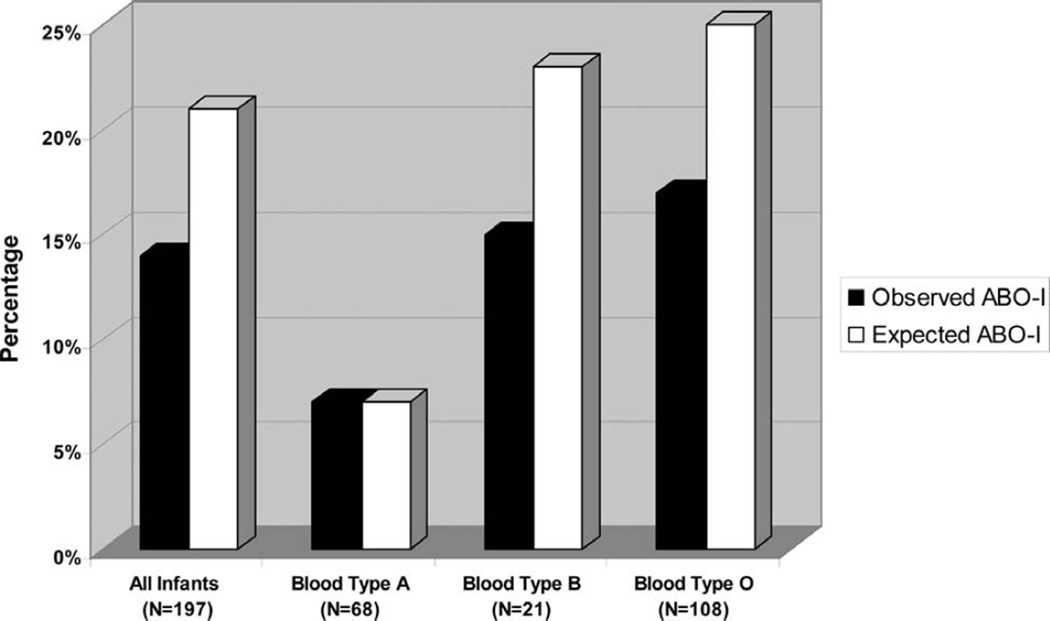

Figure 2 illustrates the competing outcomes for infants wait-listed for HT according to ABO listing strategy for the overall propensity-matched cohorts (Figure 2A and 2B) and for infants with blood type O (Figure 2C and 2D). Overall, infants assigned an ABO-I listing strategy appeared more likely to undergo HT by 30 days, although the difference did not reach statistical significance (31% for ABO-I versus 26% for ABO-C; P=0.14). The reduction in the median wait time for a donor heart (72 days for the ABO-C versus 54 days for ABO-I group; P=0.21) was also not significant but suggested a trend. However, for infants with blood type O, twice as many infants had undergone HT by 30 days (31% versus 16%; P=0.007) with a median waiting time that decreased from 87 days (95% confidence interval, 61 to 125 days) to 48 days (95% confidence interval, 33 to 65 days). There was no appreciable difference in waiting times for infants with blood type A or B. Overall, only 14% of 197 infants listed for an ABO-I HT received a heart from a donor with ABO-I blood type (7% for infants with blood type A, 15% for infants with blood type B, and 17% with blood type O). Because under current UNOS policy donor hearts are allocated to ABO-I candidates only if no ABO-C candidate can be found first, we also calculated the expected probability of ABO-I HT if donor hearts were allocated without a preference to compatibility status (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Competing outcomes for propensity-matched infants awaiting HT using an ABO-C (A) vs ABO-I (B) listing strategy.

Figure 3.

Observed vs. expected proportion of infants receiving an ABO-I HT. The expected probability of ABO-I HT was calculated as the product of the probability of transplantation and the probability of receiving an ABO-I organ conditional on being transplanted for each blood type.

Table 3 summarizes the impact of ABO-I listing strategy on waiting list mortality for the propensity-matched cohorts. Overall, there was no observable difference in waiting list mortality for infants listed for an ABO-I versus an ABO-C HT, regardless of patient blood type or whether the primary outcome was death or a composite outcome of death or permanent delisting because of clinical deterioration.

Table 3.

Hazard Ratios for Death on the Waiting List or Permanent Delisting Because of Clinical Deterioration Comparing the ABO-C and ABO-I Listing Strategy

| Unadjusted HR (95% CI) | Propensity-Matched HR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|

| All subjects | 1.6 (1.2–2.0) | 1.1 (0.8–1.6) |

| Blood type O | 1.7 (1.2–2.3) | 1.4 (0.9–2.2) |

| Blood type A | 1.6 (1.0–2.6) | 0.8 (0.5–1.5) |

| Blood type B | 1.1 (0.5–2.4) | 0.9 (0.3–3.2) |

HR indicates hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Because the observed probability of receiving an ABO-I HT appeared low (14%) and, under current UNOS policy, donor hearts are allocated to ABO-I candidates only if no ABO-C candidate can be found first, we calculated the expected probability of ABO-I HT in the United States if donor hearts were allocated in a manner that was neutral with respect to ABO compatibility (Figure 3).

Because there were infants in whom the listing strategy changed after the initial listing for HT (ie, assignment changed from an ABO-C listing strategy to an ABO-I listing—a group of infants not included in either of the propensity-matched cohorts), we performed a secondary analysis that included all infants who had ever been listed for an ABO-I HT during the wait-list period in the ABO-I group and found results similar to those reported above.

Discussion

In this study, we report that the US practice of listing infants for a potential ABO-I HT has risen dramatically over the past several years—to the point where, as of 2006, just over half of eligible infants have been assigned to an ABO-I listing strategy at some point during the waiting period, a proportion that is even higher among higher-risk infants. Infants with blood group O were most likely to benefit from being assigned an ABO-I listing strategy and, as a group, were twice as likely to be transplanted by 30 days after listing with an overall reduction in waiting time by as much as 45% (ie, 87 to 48 days). Although the benefit for infants with other blood types did not reach statistical significance, infants assigned an ABO-I listing strategy likely experience a 20% to 25% reduction in waiting time (or 2 to 3 weeks) for a donor heart.

This is the first report to document this fundamental change in clinical practice for US infants awaiting HT, which follows in the wake of the landmark report by West and colleagues4 in 2001 first describing successful transplantation of 10 infants with ABO-I cardiac allografts. Before 2001, ABO-I HT was generally performed only in the context of a medical error12 and generally resulted in a catastrophic outcome because of hyperacute rejection mediated by ABO isohemagglutinin antibodies.13 The present study describes how the prevalence of ABO-I listing has grown from a rare event strenuously avoided to the predominant clinical practice for at-risk infants in the contemporary era within a short 5-year time span. The present study is also the first to describe the reduction in waiting times attributable to ABO-I listing in a large multicenter cohort of patients, a benefit that has been largely presumed and poorly quantified until now.

As expected, the potential benefit of being assigned to an ABO-I listing strategy depends heavily on patient blood type. Infants with blood type O stand the most to gain from an ABO-I listing strategy because they are eligible for the fewest hearts when assigned to an ABO-C listing strategy (ie, blood type O hearts alone). If the same patient is assigned to an ABO-I HT listing strategy, the pool of donor hearts more than doubles (to include blood types A, B, and AB donor hearts). In contrast, infants with blood type A have the least to gain from an ABO-I listing strategy because the pool of donor hearts increases by only 15% to 20%. The benefit of an ABO-I listing strategy for infants with blood type B lies somewhere in between (expansion of the donor pool by ≈35%) but is difficult to demonstrate statistically because the low population prevalence of blood type B. Despite a pronounced difference in wait-list time for the propensity score–matched blood group O patients, we did not observe a significant reduction in waiting list mortality. This finding can be explained in large part by the smaller proportion of infants who ultimately reach the end point of death as opposed to transplantation, thus increasing the chance of a type II error. The lower frequency of death relative to transplantation likely stems from the presence of multiple competing outcomes for patients who have not received a transplant at a given time point, which effectively dilutes the strength of association between time to transplantation and waiting list mortality.

The findings of this study have several implications. First, our findings suggest that the practice of listing infants for a potential ABO-I HT may be emerging as a new standard of care for at-risk infants awaiting HT. The relatively rapid adoption of this listing practice across the United States likely stems from widespread appreciation for the high waiting list mortality facing US infants,2,14–16 combined with greater confidence in the outcomes of ABO-I HT3,4,8 and the reliability of therapeutic techniques to prevent or reduce the alloantibodies responsible for severe antibody-mediated rejection in children.3,4,8,17–20

Second, our findings suggest that the practice of listing infants for a potential ABO-I HT may actually be underused in many US centers if, indeed, outcomes after ABO-C and ABO-I HT are comparable. It could be argued that if the total number of donor hearts for infant candidates is limited, universal adoption of an ABO-I listing strategy for all infants would simply redirect scarce donor hearts to a different recipient cohort without an actual change in wait-list mortality. However, because a finite quantity of infant donor hearts are discarded each year in the US, it is likely that some wait-list deaths could be prevented by expanding the listing practice to most, if not all, eligible infants whose heart disease is judged severe enough to merit listing for an HT. According to data provided by UNOS, between 1999 and 2008, there were 246 infant organ donors in whom the heart was not recovered. Donor quality was not in question for at least 20% of these hearts. Even if only 5 to 10 additional donor hearts were transplanted rather than discarded each year, the impact on wait-list mortality could be significant (eg, ≥20% reduction), given the absolute number of infants who die annually waiting for a donor heart (ie, 30 to 40 infants in the United States).

Lastly, our findings suggest that the current organ allocation practice of prioritizing ABO-C hearts ahead of ABO-I hearts for infants awaiting HT may be outdated. The current allocation policy in the United States allows a donor heart to be directed to an ABO-I HT candidate only after no ABO-C candidate can be located. This may account for our observation that the percentage of infants actually receiving an ABO-I HT is lower than the theoretical rate (ie, 13% versus 21%) if ABO-I and ABO-C hearts were allocated with equal priority (Figure 3). Yet, because of the tendency to reserve the ABO-I listing strategy for sicker infants,3 allocating hearts to ABO-C candidates first effectively disadvantages infants assigned to an ABO-I listing strategy without compelling justification. If true, the current allocation practice may be working at cross-purposes with the Final Rule on Organ Allocation to allocate organs on the basis of medical urgency21 and net benefit. Ultimately, examining the net benefit of any proposed changes to organ allocation practice serves to ensure that overall survival surrounding organ transplantation—rather than simply wait-list survival or posttransplantation survival—is optimized, which can often lead to conflicting recommendations for organ allocation policy.

The findings of this study have several limitations related to the study design. First, our primary analysis did not account for changes in ABO-I listing status after the time of initial listing. However, secondary analyses looking at all patients listed for an ABO-I at any point yielded similar findings. Second, retrospective studies are susceptible to selection bias if a nonrepresentative sample of patients is selected for analysis. However, UNOS captures all patients listed for organ transplantation, making it less unlikely that the original study cohort is made up of a skewed population. The selection of propensity score– matched cohorts for direct comparison allowed us to address the imbalance in distribution of risk factors that existed between ABO-C– and ABO-I–listed infants in the entire cohort. Our findings are consistent in direction and magnitude with the predicted reduction in waiting times. Finally, the relatively small sample size of propensity-matched cohorts and the current allocation policy (which preferentially directs hearts to ABO-C–listed candidates) did not allow the comparisons to consistently achieve statistical significance. Nonetheless, this analysis provides us with a critical mass of evidence to responsibly support timely and important inferences.

Conclusions

The clinical practice of listing infants for a potential ABO-I HT has increased dramatically in recent years in the United States but still appears to be preferentially used for sicker infant candidates. Eligible infants listed for a potential ABO-I heart, especially infants with blood type O, can expect a meaningful reduction in waiting time for a donor heart and potentially a higher probability of surviving to transplantation. The ABO-I listing strategy may be currently underused by many US centers and may benefit a broader range of transplantation candidates.

CLINICAL PERSPECTIVE.

Unlike older children and adults awaiting heart transplantation, infants are unique in their capacity to safely receive a heart transplant from an ABO-incompatible donor. Although the purported advantage of ABO-incompatible (ABO-I) listing is to reduce wait times and secondarily waiting list mortality, limited data are available on actual waiting list outcomes for infants listed for a potential ABO-I HT or recent changes in clinical practice in the willingness of US institutions to list infants for an ABO-I heart transplantation. The present study describes recent trends in the US practice of listing infants for an ABO-I heart transplantation using data from the Organ Procurement and Transplant Network and analyzes the impact of ABO-I listing on organ waiting times after adjustment for patient factors. In short, the clinical practice of listing infants for a potential ABO-I HT has risen dramatically in recent years in the United States but still appears to be used preferentially for sicker infant candidates. Eligible infants listed for a potential ABO-I heart, especially infants with blood type O, can expect a meaningful reduction in waiting time for a donor heart and potentially a higher probability of surviving to transplantation. The ABO-I listing strategy may be currently underused by many US centers and may benefit a broader range of transplant candidates.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding

This study was supported in part by the Alexia Clinton Family and the National Institutes of Health under award number: T32HL007572. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

The data reported here are based on Organ Procurement Transplant Network (OPTN) data as of August 20, 2008. The data reported here have been supplied by the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) as the contractor for the OPTN. The interpretation and reporting of these data are the responsibility of the authors and in no way should be seen as an official policy of or interpretation by the OPTN or the US government.

Disclosures

None

References

- 1.McDiarmid S. Death on the pediatric waiting list: scope of the problem. Paper presented at: Summit on Organ Donation and Transplantation; April 19–20, 2007; San Antonio, Tex. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mah D, Singh TP, Thiagarajan RR, Gauvreau K, Piercey GE, Blume ED, Fynn-Thompson F, Almond CS. Incidence and risk factors for mortality in infants awaiting heart transplantation in the USA. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2009;28:1292–1298. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2009.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Patel ND, Weiss ES, Scheel J, Cameron DE, Vricella LA. ABO-incompatible heart transplantation in infants: analysis of the united network for organ sharing database. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2008;27:1085–1089. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2008.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.West LJ, Pollock-Barziv SM, Dipchand AI, Lee KJ, Cardella CJ, Benson LN, Rebeyka IM, Coles JG. ABO-incompatible heart transplantation in infants. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:793–800. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200103153441102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schmoeckel M, Dabritz SH, Kozlik-Feldmann R, Wittmann G, Christ F, Kowalski C, Meiser BM, Netz H, Reichart B. Successful ABO-incompatible heart transplantation in two infants. Transpl Int. 2005;18:1210–1214. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-2277.2005.00181.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rao JN, Hasan A, Hamilton JR, Bolton D, Haynes S, Smith JH, Wallis J, Kesteven P, Khattak K, O'Sullivan J, Dark JH. ABO-incompatible heart transplantation in infants: the Freeman Hospital experience. Transplantation. 2004;77:1389–1394. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000121766.35660.b2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Daebritz SH, Schmoeckel M, Mair H, Kozlik-Feldmann R, Wittmann G, Kowalski C, Kaczmarek I, Reichart B. Blood type incompatible cardiac transplantation in young infants. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2007;31:339–343. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2006.11.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.West LJ, Karamlou T, Dipchand AI, Pollock-BarZiv SM, Coles JG, McCrindle BW. Impact on outcomes after listing and transplantation, of a strategy to accept ABO blood group-incompatible donor hearts for neonates and infants. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2006;131:455–461. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2005.09.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Renlund DG, Taylor DO, Kfoury AG, Shaddy RS. New UNOS rules: historical background and implications for transplantation management: United Network for Organ Sharing. J Heart Lung Transplant. 1999;18:1065–1070. doi: 10.1016/s1053-2498(99)00075-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schwartz GJ, Haycock GB, Edelmann CM, Jr, Spitzer A. A simple estimate of glomerular filtration rate in children derived from body length and plasma creatinine. Pediatrics. 1976;58:259–263. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.D'Agostino RB., Jr Propensity score methods for bias reduction in the comparison of a treatment to a non-randomized control group. Stat Med. 1998;17:2265–2281. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19981015)17:19<2265::aid-sim918>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grady D, Altman LK. Doctors say girl in donor mix-up has permanent brain damage. The New York Times. 2003 Mar 12; [Google Scholar]

- 13.Paul LC, Baldwin WM., III Humoral rejection mechanisms and ABO incompatibility in renal transplantation. Transplant Proc. 1987;19:4463–4467. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morrow WR, Naftel D, Chinnock R, Canter C, Boucek M, Zales V, McGiffin DC, Kirklin JK. Outcome of listing for heart transplantation in infants younger than six months: predictors of death and interval to transplantation: the Pediatric Heart Transplantation Study Group. J Heart Lung Transplant. 1997;16:1255–1266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mital S, Addonizio LJ, Lamour JM, Hsu DT. Outcome of children with end-stage congenital heart disease waiting for cardiac transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2003;22:147–153. doi: 10.1016/s1053-2498(02)00670-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Almond CS, Thiagarajan RR, Piercey GE, Gauvreau K, Blume ED, Bastardi HJ, Fynn-Thompson F, Singh TP. Waiting list mortality among children listed for heart transplantation in the United States. Circulation. 2009;119:717–727. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.815712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pollock-BarZiv SM, den Hollander N, Ngan BY, Kantor P, McCrindle B, Dipchand AI, West LJ. Pediatric heart transplantation in human leukocyte antigen sensitized patients: evolving management and assessment of intermediate-term outcomes in a high-risk population. Circulation. 2007;116(suppl):I-172–I-178. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.709022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Holt DB, Lublin DM, Phelan DL, Boslaugh SE, Gandhi SK, Huddleston CB, Saffitz JE, Canter CE. Mortality and morbidity in pre-sensitized pediatric heart transplant recipients with a positive donor crossmatch utilizing peri-operative plasmapheresis and cytolytic therapy. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2007;26:876–882. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2007.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wright EJ, Fiser WP, Edens RE, Frazier EA, Morrow WR, Imamura M, Jaquiss RD. Cardiac transplant outcomes in pediatric patients with pre-formed anti-human leukocyte antigen antibodies and/or positive retrospective crossmatch. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2007;26:1163–1169. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2007.07.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roche SL, Burch M, O'Sullivan J, Wallis J, Parry G, Kirk R, Elliot M, Shaw N, Flett J, Hamilton JR, Hasan A. Multicenter experience of ABO-incompatible pediatric cardiac transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2008;8:208–215. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2007.02040.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Department of Health and Human Services. Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network: final rule. Vol Fed Reg 42 CFR. 1999:56649–56661. [Google Scholar]