Abstract

The relationship between anxiety and alcohol use in adolescence remains unclear, with evidence for no association, as well as risk and protective effects of anxiety. Considering developmental trajectories may be important for understanding the association between anxiety and alcohol use, and may help clarify prior mixed findings. The present study examined trajectories of alcohol use, social anxiety and general anxiety symptoms in early to middle adolescence using univariate and parallel process growth models. Social anxiety and general anxiety symptoms declined, while alcohol use increased with age. Parallel process growth models suggested that less rapid declines in social anxiety and general anxiety symptoms were associated with more rapid escalation in alcohol use. These results suggest that young adolescents who do not show normative declines in social anxiety or general anxiety symptoms may be at risk for more rapid increases in alcohol use.

Keywords: adolescence, alcohol use, generalized anxiety, social anxiety

Anxiety, most commonly generalized and social anxiety symptoms, is often discussed as a risk factor for adolescent drinking, typically via a self-medication pathway whereby alcohol use is posited to be motivated to relieve emotional distress. However, the literature documents mixed findings regarding the link between anxiety and adolescent alcohol use (Blumenthal, Leen-Feldner, Badour & Babson, 2012). General and social anxiety symptoms and alcohol use show age-related changes during adolescence (Van Oort et al., 2009; LaGreca, 1999). Understanding the dynamics of normative developmental trajectories of anxiety and alcohol use may help clarify the mixed literature, yet limited research has examined this issue. The present study addresses this gap by examining age-related changes in anxiety and adolescent alcohol use, and dynamic associations between these constructs.

The role of anxiety in the etiology of adolescent alcohol use may vary with age and stage of drinking, such that anxiety protects youth from alcohol use in early adolescence when drinking is typically initiated, but after initiation, anxiety predicts escalation of alcohol use (Colder, Chassin, Lee & Villalta, 2010). There is evidence that generalized anxiety symptoms are associated with escalation, but not initiation of alcohol use (Sung, Erkanli, Angold & Costello, 2004; Sartor, Lynsky, Heath, Jacob & True, 2007; Frojd et al., 2011). The pattern of findings is less clear for social anxiety, such that social anxiety may be unrelated to early adolescent alcohol use (Blumenthal et al., 2012), or may operate as a protective factor (Wu et al., 2010; Frojd et al., 2011) or as a risk factor (Marmorstein, White, Loeber & Stouthamer-Loeber, 2010). Yet by late adolescence there is consistent support for social anxiety as a risk factor for alcohol use (Burke & Stevens, 1999). In sum, the literature suggests some support for anxiety showing different associations with alcohol in early versus late adolescence, but the evidence is stronger for generalized anxiety than social anxiety.

When considering the impact of anxiety on the development of adolescent alcohol use, it is important to consider that both alcohol use and anxiety symptoms show normative changes during adolescence. Most youth begin using alcohol in early adolescence, with use escalating into late adolescence (Chen & Kandel, 1995; Colder et al., 2002; Johnson et al., 2010). Social and general anxiety symptoms decline modestly during early adolescence, and then increase from middle adolescence through late adolescence (Van Oort et al., 2009; LaGreca, 1999). Considering developmental changes in anxiety may help elucidate the link between anxiety and adolescent alcohol use, yet no studies to our knowledge have examined potential associations between trajectories of anxiety and alcohol use during adolescence.

Adolescents who are elevated on social anxiety in early adolescence may be delayed in onset of alcohol use because the associated social withdrawal and avoidance may protect them from peer contexts where drinking is most likely to occur (Hussong, 2000). Early generalized anxiety symptoms may protect youth from drinking because of worry about harm or getting into trouble for engaging in an illegal activity. As alcohol use becomes more normative in middle and late adolescence, increased modeling of alcohol use by peers coupled with greater access to alcohol may result in increased risk for alcohol use by adolescents with anxiety symptomology (Hussong, Jones, Stein, Baucom & Boeding, 2011). Through learning, drinking may come to be viewed as a means of facilitating social relationships, conforming to perceived social norms, and self-medicating distress, particularly among anxious youth, resulting in escalation of alcohol use (Blumenthal, Leen-Feldner, Frala, Badour & Ham, 2010; Burke & Stephens, 1999; Ham, Hope, White & Rivers, 2002; Buckner, Eggleston & Schmidt, 2006). Indeed, coping and conformity drinking motives have been shown to mediate the relationship between social anxiety (particularly fear of negative evaluation) and alcohol use in late adolescence, as well as general distress and alcohol use in adolescence (Stewart, Morris, Mellings & Komar, 2006; Stewart, Zvolensky, & Eifert, 2001; Cooper, Frone, Russell & Mudar, 1995). Thus, anxiety may protect against alcohol use in early adolescence, but may be associated with escalation of drinking.

The present study examined associations between alcohol use and two facets of anxiety in a longitudinal community sample of early to middle adolescents. We modeled growth in generalized anxiety and social anxiety symptoms and alcohol use, and examined associations between initial levels of anxiety symptoms and initial levels of alcohol use as well as growth in alcohol use. Hypotheses are presented in Table 1. Although we expected social anxiety and general anxiety to have similar associations with alcohol use, we separated the constructs given stronger evidence in the literature for developmental shifts in association with alcohol for general anxiety. Given the considerable overlap between generalized anxiety and social anxiety (Costello & Angold, 1995), we considered the prediction of general anxiety on alcohol use controlling for social anxiety and vice versa.

Table 1.

Hypotheses

| Initial level of anxiety | Association with alcohol |

| 1.High initial social or general anxiety | Low initial alcohol use a |

| 2.High initial social or general anxiety | Increasing alcohol use b |

| Initial level of alcohol use | Association with anxiety |

| 3. High initial alcohol use | No association with changes in social or general anxiety |

| Changing levels of anxiety | Associations with growth in alcohol |

| No hypotheses offered c | |

Due to social avoidance or worry about the potential negative consequences of drinking.

Perhaps reflecting attempts to cope with distress associated with excessive worry or social concerns by drinking.

Given the dearth of studies on growth in anxiety and alcohol use in early adolescence

Method

Participants and procedures

The community sample included 387 adolescent-caregiver pairs interviewed annually for three years as part of a longitudinal project examining behavior problems and the development of substance use. The sample was recruited by means of random digit dialing within Erie County, NY (see Sample 1, Colder et al., 2012 for further details on recruitment and sample description). At wave 1, 55% of the adolescents were female and 83% were White/non-Hispanic. At the first assessment, the mean age was 12.09 (range 11 – 13) and median family income was $70,000 (range $1,500-$500,000). Retention was strong, with a combined attrition rate across waves 2 and 3 of 4.4%. Most follow-up interviews (90%) occurred within two months of the year anniversary of the previous assessment. Measures were computer administered by trained research assistants on a university campus over approximately 2.5 hours. Families received $75 (Wave 1), $85 (Wave 2), and $125 (Wave 3).

Measures

Social Anxiety

Social anxiety was assessed using the Social Anxiety Scale for Children, Revised (adolescent report; SASC-R; La Greca, 1999). Cronbach's alpha was .90, .92, and .93 at waves 1-3, respectively.

Generalized Anxiety

Generalized anxiety was assessed using the Youth Self Report (YSR; Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001), and scored using Lengua's system that distinguishes DSM categories of anxiety (Lengua, Sadowski, Friedrich & Fisher, 2001). Cronbach's alpha was .67, .70 and .76 at Waves 1-3, respectively.

Alcohol Use

Quantity and frequency of past year alcohol use was assessed using two items taken from the National Youth Survey (NYS; Huizinga & Elliott, 1983). Rates of use in the past year were 14%, 19%, and 29%, respectively at Waves 1-3. A quantity x frequency index (total drinks in the past year) was computed and converted into a three-level ordinal variable (no use in the past year, one to five drinks in the past year, and five or more drinks in the past year) to accommodate the expected low frequency of use.

Data analytic plan

Latent growth curve modeling with individually-varying ages of observation (modeling growth as a function of age) was used to account for variability in age at the first assessment and variability in follow-up intervals. This approach yielded an age range of 11.0 to 15.5 years over three waves. Analyses were performed using Mplus 6.1 (Muthen & Muthen, 2010), using full information maximum likelihood estimation when modeling anxiety symptoms (as they showed acceptable levels of skew) and weighted least squares when modeling the ordinal alcohol use variable. Because these models do not generate traditional model fit indices, nested likelihood ratio tests were used to evaluate if adding random linear trends improved model fit. The models included linear trends with the intercept specified to represent levels of the outcome (anxiety or alcohol use) at age 11. We began with unconditional growth models for each variable (social anxiety, general anxiety, and alcohol use). Next we ran a growth model for social anxiety and included generalized anxiety symptoms as a time-varying covariate so that we could examine change in social anxiety above and beyond generalized anxiety. We ran a similar model for generalized anxiety symptoms controlling for social anxiety symptoms. Finally, we ran parallel process models that included alcohol use and one symptom variable (social anxiety or general anxiety).

Results

Correlations, stabilities and descriptive statistics are presented in Table 2. Means suggest that social anxiety and general anxiety decline modestly over time. Cross-sectional correlations between social anxiety and general anxiety are moderate (.44 to .51).

Table 2.

Correlations, stabilities and descriptive statistics

| 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Social Anxiety (Tl) | 1.000 | |||||

| 2. Social Anxiety (T2) | 0.663** | 1.000 | ||||

| 3. Social Anxiety (T3) | 0.536** | 0.708** | 1.000 | |||

| 4. General Anxiety (Tl) | 0.443** | 0.376** | 0.320** | 1.000 | ||

| 5. General Anxiety (T2) | 0.331** | 0.491** | 0.449** | 0.548** | 1.000 | |

| 6. General Anxiety (T3) | 0.305** | 0.417** | 0.510** | 0.504** | 0.710** | 1.000 |

| M | 2.163 | 2.077 | 2.033 | 0.365 | 0.315 | 0.302 |

| SD | 0.613 | 0.599 | 0.629 | 0.302 | 0.302 | 0.318 |

Note. Possible range of the social anxiety measure is one to five, and for general anxiety range is zero to two.

p < .01

* p < .05

† p < .10

Multiple group models suggested no gender differences, and therefore we report results for the males and females combined. Nested chi square tests supported a random linear trend for social anxiety (X2 (3, N=387) = 23.53, p<.05), general anxiety (X2 (3, N=387) = 19.61, p<.05), and alcohol use (X2 (3, N=387) = 69.58, p<.05). Univariate models suggested that, on average, both social anxiety and generalized anxiety declined with age with statistically reliable individual variability in both initial levels and rates of change (Tables 3 and 4). Alcohol increased with age with statistically reliable individual variability in both the intercept and slope (Table 5).1

Table 3.

Parameter estimates from growth curve model of social anxiety

| Model 1 a | Model 2 b | |

|---|---|---|

| Intercept Mean | 2.208** | 2.209** |

| Slope Mean | −.058** | −0.059** |

| Intercept Variance | .319** | 0.242** |

| Slope Variance | 0.029** | 0.022** |

| Intercept Slope Covariance | −0.047* | −0.040* |

| Beta for time-varying covariate (generalized anxiety) | ||

| Time 1 | 0.699** | |

| Time 2 | 0.743** | |

| Time 3 | 0.806** |

Note. Residual variances were specified as uncorrelated and freely estimated.

Linear growth model – no covariates.

Linear growth model – general anxiety as a time-varying covariate.

p < .01

p < .05

† p < .10

Table 4.

Parameter estimates from growth curve model of general anxiety

| Model 1 a | Model 2 b | |

|---|---|---|

| Intercept Mean | 0.377** | 0.379** |

| Slope Mean | −0.025** | −0.025** |

| Intercept Variance | .066** | 0.049** |

| Slope Variance | 0.006** | 0.005* |

| Intercept Slope Covariance | −.008† | −0.008 |

| Beta for time-varying covariate (social anxiety) | ||

| Time 1 | 0.011** | |

| Time 2 | 0.011** | |

| Time 3 | 0.010** |

Note. Residual variances were specified as uncorrelated and freely estimated.

Linear growth model – no covariates.

Linear growth model – social anxiety as a time-varying covariate.

p < .01

p < .05

p < .10

Table 5.

Parameter probabilities from growth curve model of alcohol use

| Age | Category 1 a | Category 2 b |

|---|---|---|

| 11 | 0.009 | 0.0002 |

| 12 | 0.025 | 0.0006 |

| 13 | 0.065 | 0.0016 |

| 14 | 0.155 | 0.0043 |

| 15 | 0.32 | 0.011 |

Note. Mean of intercept and slope factors = −4.619 and 0.975, respectively. Variance of intercept and slope factors = 11.996 and 1.382, respectively. All means and variances statistically significant (p<.05). Residual variances were specified as uncorrelated and freely estimated.

Probability of being in category 1 (reporting 1-5 drinks consumed over the past 12 months).

Probability of being in category 2 (reporting >5 drinks consumed over the past 12 months).

Next, we examined growth models for the symptom variables with time-varying covariates. Results were similar when general anxiety was included as a time-varying covariate in the social anxiety growth model and when social anxiety was included as a covariate in the general anxiety growth model (Tables 3 & 4). 2

In the parallel process models, slopes were regressed on intercepts, and covariances were estimated between slope factors and between intercept factors. Results for social anxiety are shown in Figure 1. First, slower than average declines in social anxiety symptoms were associated with more rapid increases in alcohol use (slope covariance). Second, in contrast to hypotheses, higher levels of social anxiety symptoms at age 11 were associated with higherinitial levels of alcohol use, but this association fell short of conventional criteria for statistical significance (intercept to intercept covariance). Third, in contrast to hypotheses, higher levels of social anxiety symptoms at age 11 were associated with less rapid increases in alcohol use (intercept to slope path), but this association fell short of conventional criteria for statistical significance. Cross-construct associations were weakened and none were statistically or marginally reliable when general anxiety was included as a covariate.

Figure 1.

Parallel process growth curve model of social anxiety symptoms and alcohol use with regression. Partial coefficients in parentheses. Parameter estimates are unstandardized. Residual variances were specified as uncorrelated and freely estimated. **p < .01, * p < .05, † p < .10

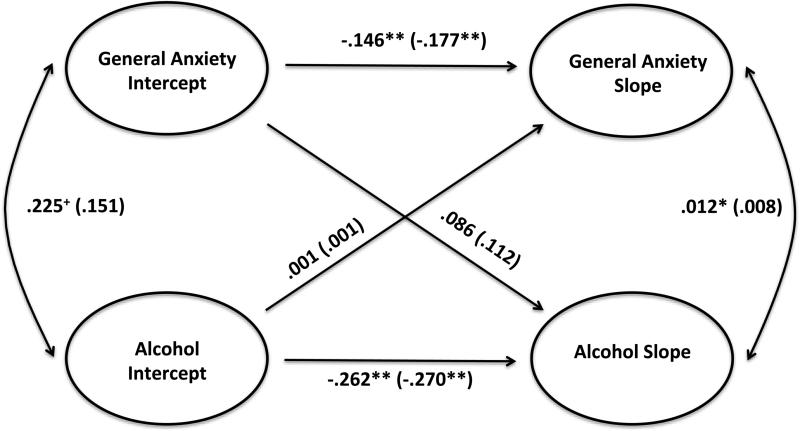

Results for general anxiety symptoms are shown in Figure 2. Slower than average declines in general anxiety symptoms were associated with more rapid increases in alcohol use (slope covariance). In contrast to hypotheses, higher levels of generalized anxiety symptoms at age 11 were associated with higher initial levels of alcohol use (intercept covariance), but this association fell short of conventional criteria for statistical significance. When social anxiety symptoms were included as a covariate, all cross-construct associations were weakened and no longer statistically reliable. Effect sizes were generally small (see Table 6).

Figure 2.

Parallel process growth curve model of generalized anxiety symptoms and alcohol use with regression. Partial coefficients in parentheses. Parameter estimates are unstandardized. Residual variances were specified as uncorrelated and freely estimated. **p < .01, * p < .05, † p < .10

Table 6.

Effect sizes for parallel process growth models

| Regression paths | ΔR2 |

|---|---|

| Social anxiety slope on alcohol intercept | 3.45% |

| Alcohol slope on social anxiety intercept | 1.25% |

| General anxiety slope on alcohol intercept | 1.66% |

| Alcohol slope on general anxiety intercept | 1.52% |

| Covariances | r(x,y) |

|---|---|

| Social anxiety slope to alcohol slope | .37 |

| Social anxiety intercept to alcohol intercept | .22 |

| General anxiety slope to alcohol slope | .14 |

| General anxiety intercept to alcohol intercept | .28 |

Discussion

This study examined the association between trajectories of alcohol use and those of social and generalized anxiety in early to middle adolescence. Alcohol use increased, whereas both social anxiety and general anxiety symptoms declined modestly with age. The nature of the relationship between anxiety and alcohol use differed for cross-sectional (intercept to intercept), prospective (intercept to slope), and dynamic (slope to slope) associations, and differed slightly for type of anxiety. Associations were small, suggesting that anxiety does not play a major role in early adolescent alcohol use. These findings will be discussed in turn.

Other studies (LaGreca, 1999; Van Oort et al., 2009), have similarly found that social and general anxiety symptoms decline in early adolescence. This decline may be related to increases in novelty seeking and shifting social goals that are characteristic of early to middle adolescents, which in turn, promote independence from adults and affiliation with peers (Crawford, Pentz, Chou, Li & Dwyer, 2003; Steinberg, 2008). Our finding that alcohol use increased is consistent with prior epidemiological studies (Chen & Kandel, 1995; Johnson et al., 2010). Overall, these findings suggest that both anxiety and alcohol use change during early to middle adolescence.

We also found support for anxiety symptomatology (both social and general anxiety symptoms) and alcohol use changing together, such that slower than normative declines in both general and social anxiety symptoms were associated with more rapid escalation in alcohol use. These dynamic associations may reflect changes in social context and also self-medication motives for drinking. Desire for peer affiliation increases and youth become more responsive to social stimuli during adolescence (Collins & Steinberg, 2006), yet high levels of anxiety are associated with peer difficulties. Thus, anxious adolescents may experience both a push away and pull toward peer relationships. Escalation of alcohol use may be motivated by a desire to gain entrée into social relationships for adolescents who do not show normative declines in anxiety. Another possibility is that adolescents who do not experience normative declines in anxiety symptomatology may be motivated to use alcohol to relieve emotional distress (a self-medication mechanism) as alcohol comes to be more normative with age. The opposing drives to affiliate with peers but also to withdraw due to anxiety may make alcohol an appealing coping strategy as youth learn about the effects of alcohol. Thus, self-medication may be intertwined with strong motives for affiliation for some youth, as is evident from the prominent role that social facilitation and tension reduction beliefs play in the etiology of adolescent drinking (Burke & Stephens, 1999; Smith, Goldman, Greenbaum & Christiansen, 1995). Finally, biologic mechanisms are likely at play as well, given emerging evidence of common neuroanatomical pathways and neurochemical systems involved in alcohol and anxiety-related behavior (Sharko, Fadel & Wilson, 2013).

It should be noted that direction of effects cannot be determined based on the observation that change in anxiety symptoms is associated with change in alcohol use during the same period (slope to slope covariances). It is also possible that increases in alcohol use disrupt normative declines of social and general anxiety symptoms. This alternative cannot be ruled out, but this direction is less plausible given the young ages and low levels of alcohol use in our sample.

Higher initial levels of social anxiety symptoms marginally predicted slower increases in alcohol use, suggesting a trend towards a protective effect of high initial levels of social anxiety. The contrast between the social anxiety-alcohol slope to slope covariance (suggestive of social anxiety being a risk factor) versus the intercept to slope path coefficient (suggestive of anxiety being a protective factor) implies that considering developmental trajectories can help clarify the mixed findings in the literature. Alcohol use during adolescence most often occurs in the context of peers, who provide access to and social reinforcement for drinking (Harford & Spiegler, 1983; Beck, Thombs, & Summons, 1993). A hallmark feature of social anxiety is social avoidance (Watson & Friend, 1969; Beidel, Turner & Morris, 1995), and thus, high levels of social anxiety in early adolescence may protect youth from peer contexts that promote drinking (Fite, Colder & O'Connor, 2006). However, as social relationships become increasingly important with age, adolescents who do not show normative declines in social anxiety symptoms may come to use alcohol as a way of medicating distress and fostering peer relationships as discussed above. Ignoring developmental changes in anxiety would likely obscure these important differences.

This study also examined the unique associations with alcohol use for each facet of anxiety. There was no evidence for unique associations with alcohol use after controlling for the other symptom facet. This suggests that what is common to generalized and social anxiety (e.g., general distress, anxious apprehension, and physiological arousal) (Clark & Watson, 1991; Bogels & Zigterman, 2000) plays a role in the etiology of adolescent alcohol use and that when these overlapping elements are removed, what remains unique to social or generalized anxiety symptoms does not appear to be germane to adolescent alcohol use.

However, specific effects may play a modest role as indicated by a trend towards different patterns of association for social and generalized anxiety. Slope to slope covariation with alcohol was similar for social and general anxiety, suggesting that what is common to these domains of anxiety underlies the dynamic associations. However, there also seems to be a relevant component of social anxiety (i.e., distress and impairment in social relationships) that operates along with what is shared with generalized anxiety (general worry and distress) that serves as a protective factor (the marginal intercept to slope effect seen in social anxiety but not general anxiety parallel process models). This suggests that facets of anxiety may be important in investigating developmental trajectories of adolescent alcohol use, but that unique effects are not informative.

Limitations and Conclusions

This study has several limitations. First, other domains of anxiety not considered in this study may also be germane to adolescent alcohol use such as post-traumatic stress (Kilpatrick, Acierno & Saunders, 2000; Read et al., 2013). Second, our findings may not generalize beyond early to middle adolescence, clinical samples or at risk youth. By adulthood, both general anxiety and social anxiety are more clearly linked to alcohol use (Kushner, Abrams & Borchardt, 2000), and thus, extending trajectories into late adolescence may yield different patterns of association. Additionally, we relied on self-report of youth internalizing and alcohol use (as is typical), and this introduces possibility of common method variance. Finally, our study was predominantly white, and we did not have adequate group sizes to test for race or ethnicity differences. Despite these limitations, the present study fills an important gap in the literature by considering adolescent anxiety and alcohol use in a developmental context. Current developmental models of adolescent alcohol use focus on externalizing symptoms (Hussong et al., 2011; Zucker, 2003). Our findings suggest the importance of considering the normative development of anxiety as well as separating anxiety symptomology into specific domains in clarifying the etiological role of anxiety in adolescent alcohol use.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01 DA019631) awarded to Craig R. Colder.

Footnotes

The alcohol growth model and the parallel process models below were also analyzed with an alternate categorization of alcohol use: no use (abstainers), a few sips to two drinks (triers), and more than two drinks (experimenters) in order to evaluate whether small cell sizes in the highest category of alcohol use were unduly influencing the results. The pattern of findings remained consistent with original results, suggesting the observed effects are robust to different thresholds of the drinking categories.

Given that depression is correlated with anxiety (Brady & Kendall, 1992), we also included depressive symptoms (as assessed using Lengua et al., 2001 depression scoring of the YSR) as an additional time-varying covariate, and results did not change.

References

- Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA. Manual for the ASEBA School-Age forms & Profiles. University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, & Families; Burlington, VT: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Beck KH, Thombs DL, Summons TG. The social context of drinking scales: Construct validation and relationship to indicants of abuse in an adolescent population. Addictive Behaviors. 1993;18(2):159–169. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(93)90046-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beidel DC, Turner SM, Morris TL. A new inventory to assess childhood social anxiety and phobia: The Social Phobia and Anxiety Inventory for Children. Psychological Assessment. 1995;7:73–79. [Google Scholar]

- Blumenthal H, Leen-Feldner EW, Badour CL, Babson KA. Anxiety psychopathology and alcohol use among adolescents: A critical review of the empirical literature and recommendations for future research. Journal of Experimental Psychopathology. 2012;2(3):318–353. doi: 10.5127/jep.012810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumenthal H, Leen-Feldner EW, Frala JL, Badour CL, Ham LS. Social anxiety and motives for alcohol use among adolescents. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2010;24(3):529–254. doi: 10.1037/a0019794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogels SM, Zigterman D. Dysfunctional cognitions in children with social phobia, separation anxiety disorder, and generalized anxiety disorder. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2000;28(2):205–211. doi: 10.1023/a:1005179032470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brady EU, Kendall PC. Comorbidity of anxiety and depression in children and adolescents. Psychological Bulletin. 1992;111:244–255. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.111.2.244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brook JS, Cohen P, Brook DW. Longitudinal study of co-occurring psychiatric disorders and substance use. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1998;37(3):322–330. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199803000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckner JD, Eggleston AM, Schmidt NB. Social anxiety and problematic alcohol consumption: The mediating role of drinking motives and situations. Behavior Therapy. 2006;37:381–391. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2006.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke RS, Stephens RS. Social anxiety and drinking in college students: A social cognitive theory analysis. Clinical Psychology Review. 1999;19(5):513–530. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(98)00058-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen K, Kandel D. The natural history of drug use in a general population sample from adolescence to the mid-thirties. American Journal of Public Health. 1995;85(1):41–47. doi: 10.2105/ajph.85.1.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark LA, Watson D. Tripartite model of anxiety and depression: Psychometric evidence and taxonomic implications. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1991;100(3):316–336. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.100.3.316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colder CR, Campbell RT, Ruel E, Richardson JL, Flay BR. A finite mixture model of growth trajectories of adolescent alcohol use: Predictors and consequences. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2002;70(4):976–985. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.70.4.976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colder CR, Chassin L, Lee MR, Villalta IK. Developmental perspectives: Affect and adolescent substance use. In: Kassel J, editor. Substance abuse and emotion. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC: 2010. pp. 109–136. [Google Scholar]

- Colder CR, Hawk LW, Lengua LJ, Wieczorek WF, Eiden RD, Read JP. Trajectories of reinforcement sensitivity during adolescence and risk for substance use. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2012 doi: 10.1111/jora.12001. DOI: 10.1111/jora.12001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins WA, Steinberg L. Adolescent development in interpersonal context. In: Eisenberg N, editor. Handbook of child psychology (6th edition): Social, emotional, and personality development. Wiley; New York: 2006. pp. 619–700. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML, Frone MR, Russell M, Mudar P. Drinking to regulate positive and negative emotions: A motivational model of alcohol use. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1995;69(5):990–1005. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.69.5.990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costello EJ, Angold A. Epidemiology. In: Marsh JS, editor. Anxiety disorders in children and adolescents. The Guilford Press; New York: 1995. pp. 109–124. [Google Scholar]

- Crawford AM, Pentz MA, Chou C, Li C, Dwyer JH. Parallel trajectories of sensation seeking and regular substance use in adolescents. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2003;17:179–192. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.17.3.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fite PJ, Colder CR, O'Connor RM. Childhood behavior problems and peer selection and socialization: Risk for adolescent alcohol use. Addictive Behaviors. 2006;31(8):1454–1459. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frojd S, Ranta K, Kaltiala-Heino R, Marttunen M. Associations of social phobia and general anxiety with alcohol and drug use in a community sample of adolescents. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 2011;46(2):192–199. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agq096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant JD, Sherrer JF, Lynskey MT, Lyons MJ, Eisen SA, Tsuang MT, True WR, Bucholz KK. Adolescent alcohol use is a risk factor for adult alcohol and drug dependence: evidence from a twin design. Psychological Medicine. 2006;36(1):109–118. doi: 10.1017/S0033291705006045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hale WW, Raaijmakers Q, Muris P, Van Hoof A, Meeus W. Developmental trajectories of adolescent anxiety disorder symptoms: A 5-year prospective community study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2008;47(5):556–564. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181676583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ham LS, Hope DA, White CS, Rivers PC. Alcohol expectancies and drinking behavior in adults with social anxiety disorder and dysthymia. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2002;26(2):275–288. [Google Scholar]

- Harford T, Spiegler DL. Developmental trends in adolescent drinking. Journal of Sudies on Alcohol. 1983;44:181–188. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1983.44.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huizinga D, Elliott DS. National Youth Survey Project Report 27: A preliminary examination of the reliability and validity of the national youth survey self-reported delinquency indices. Behavioral Research Institute; Boulder, CO: 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Hussong AM. The settings of adolescent alcohol and drug use. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2000;29(1):107–109. [Google Scholar]

- Hussong AM, Jones DJ, Stein GL, Baucom DH, Boeding S. An internalizing pathway to alcohol use and disorder. Psychology of Addictive Behavior. 2011;25(3):390–404. doi: 10.1037/a0024519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson LD, O'Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the Future national results on adolescent drug use: Overview of key findings, 2009. National Institute on Drug Abuse; Bethesda, MD: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplow JB, Curran PJ, Angold A, Costello EJ. The prospective relation between dimensions of anxiety and the initiation of adolescent alcohol use. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 2001;30(3):316–326. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3003_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilpatrick DG, Acierno R, Saunders B. Risk factors for adolescent substance abuse and dependence: Data from a national sample. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68:19–30. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.68.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kushner MG, Abrams K, Borchardt C. The relationship between anxiety disorders and alcohol use disorders: A review of major perspectives and findings. Clinical Psychology Review. 2000;20(2):149–171. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(99)00027-6. 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kushner MG, Sher KJ, Erickson DJ. Prospective analysis of the relation between DSM-III anxiety disorders and alcohol use disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1999;156:723–732. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.5.723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lengua LJ, Sadowski CA, Friedrich WN, Fisher J. Rationally and empirically derived dimensions of children's symptomatology: Expert ratings and confirmatory factor analysis of the CBCL. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2001 Aug;69(4):683–698. 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Greca AM. Manual for the Social Anxiety Scales for Children and Adolescents. Author; Miami, FL: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Marmorstein NR, White HR, Loeber R, Stouthamer-Loeber M. Anxiety as a predictor of age at first use of substances and progression to substance use problems among boys. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2010;38:211–224. doi: 10.1007/s10802-009-9360-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers MG, Aarons GA, Tomlinson K, Stein MB. Social anxiety, negative affectivity, and substance use among high school students. Psychology of addictive behaviors. 2003;17(4):277–183. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.17.4.277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthen LK, Muthen BO. Mplus: The comprehensive modeling program for applied researchers (Version 6.1) Muthen & Muthen; Los Angeles, CA: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Read JP, Colder CR, Merrill JE, Oimette P, White J, Swartout A. Trauma and posttraumatic stress symptoms predict alcohol and other drug consequence trajectories in the first year of college. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2013;80(3):426–439. doi: 10.1037/a0028210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sartor C, Lynsky M, Heath A, Jacob T, True W. The role of childhood risk factors in initiation of alcohol use and progression to alcohol dependence. Addiction. 2007;102:216–225. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01661.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharko AC, Fadel JR, Wilson MA. Mechanisms and mediators of the relationship between anxiety disorders and alcohol use disorders: Focus on amygdalar NPY. Journal of Addiction Research & Therapy. 2013;S4:14–023. [Google Scholar]

- Sher KJ, Grekin ER. Alcohol and affect regulation. In: Gross JE, editor. Handbook of Emotion Regulation. Guilford Press; New York: 2007. pp. 560–580. [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L. Social neuroscience perspective on adolescent risk-taking. Developmental Review. 2008;28:78–106. doi: 10.1016/j.dr.2007.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith GT, Goldman MS, Greenbaum PE, Christiansen BA. Expectancy for social facilitation from drinking: The divergent paths of high-expectancy and low-expectancy adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1995;104:32–40. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.104.1.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart SH, Morris E, Mellings T, Komar J. Relations of social anxiety variables to drinking motives, drinking quantity and frequency, and alcohol-related problems in undergraduates. Journal of Mental Health. 2006;15(6):671–682. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart SH, Zvolensky MJ, Eifert GH. Negative-reinforcement drinking motives mediate the relationship between anxiety sensitivity and increased drinking behavior. Personality and Individual Differences. 2001;31(2):157–171. [Google Scholar]

- Sung M, Erkanli A, Angold A, Costello EJ. Effects of age at first substance use and psychiatric comorbidity on the development of substance use disorders. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2004;75(3):287–299. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Oort FVA, Greaves-Lord K, Verhulst FC, Ormel J, Huizink AC. The developmental course of anxiety symptoms during adolescence: The TRIALS study. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2009;50(10):1209–1217. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2009.02092.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Friend R. Measurement of social-evaluative anxiety. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1969;33:448–457. doi: 10.1037/h0027806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Windle M. A retrospective measure of childhood behavior problems and its use in predicting adolescent problem behaviors. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1993;54(4):422–431. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1993.54.422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Windle M. Alcohol use among adolescents and young adults. Alcohol Research and Health. 2003;27(1):79–85. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu P, Goodwin RD, Fuller C, Liu X, Comer JS, Cohen P, Howen CW. The relationship between anxiety disorders and substance use among adolescents in the community: Specificity and gender differences. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2010;39(2):177–188. doi: 10.1007/s10964-008-9385-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zucker RA. Causal structure of alcohol use and problems in early life: Mulitlevel etiology and implications for prevention. In: Biglan A, Wang MC, Walberg HJ, editors. Preventing Youth Problems. Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers; New York: 2003. pp. 33–61. [Google Scholar]