Failed back surgery syndrome refers to persistent back pain following back surgery. The optimal course of treatment for this syndrome varies according to the patient and the etiology of the pain. This study describes the application of a treatment algorithm for failed back surgery syndrome, focusing on the use of epiduroscopy, a novel technique that is useful for diagnosis and treatment of this syndrome. Diagnoses and treatment success after one year of follow-up are reported.

Keywords: Epiduroscopy, Failed back surgery, Pain management, Spinal cord

Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Failed back surgery syndrome (FBSS) is a major clinical problem. Different etiologies with different incidence rates have been proposed. There are currently no standards regarding the management of these patients. Epiduroscopy is an endoscopic technique that may play a role in the management of FBSS.

OBJECTIVE:

To evaluate an algorithm for management of severe FBSS including epiduroscopy as a diagnostic and therapeutic tool.

METHODS:

A total of 133 patients with severe symptoms of FBSS (visual analogue scale score ≥7) and no response to pharmacological treatment and physical therapy were included. A six-step management algorithm was applied. Data, including patient demographics, pain and surgical procedure, were analyzed. In all cases, one or more objective causes of pain were established. Treatment success was defined as ≥50% long-term pain relief maintained during the first year of follow-up. Final allocation of patients was registered: good outcome with conservative treatment, surgical reintervention and palliative treatment with implantable devices.

RESULTS:

Of 122 patients enrolled, 59.84% underwent instrumented surgery and 40.16% a noninstrumented procedure. Most (64.75%) experienced significant pain relief with conventional pain clinic treatments; 15.57% required surgical treatment. Palliative spinal cord stimulation and spinal analgesia were applied in 9.84% and 2.46% of the cases, respectively. The most common diagnosis was epidural fibrosis, followed by disc herniation, global or lateral stenosis, and foraminal stenosis.

CONCLUSIONS:

A new six-step ladder approach to severe FBSS management that includes epiduroscopy was analyzed. Etiologies are accurately described and a useful role of epiduroscopy was confirmed.

Abstract

HISTORIQUE :

Le syndrome d’échec postchirurgical rachidien (SÉPCR) est un problème clinique majeur. Différentes étiologies aux divers taux d’incidence sont proposées. Il n’y a pas de norme de traitement pour ces patients. L’épiduroscopie est une technique endoscopique qui pourrait jouer un rôle dans la prise en charge du SÉPCR.

OBJECTIF :

Évaluer un algorithme pour traiter un grave SÉPCR incluant une épiduroscopie comme outil diagnostique et thérapeutique.

MÉTHODOLOGIE :

Au total, 133 patients ayant de graves symptômes de SÉPCR (indice d’au moins 7 à l’échelle visuelle analogique) et ne répondant pas au traitement pharmacologique et à la physiothérapie ont participé à l’étude. Un algorithme de prise en charge en six étapes a été utilisé. Les chercheurs ont analysé les données, y compris la démographie, la douleur et les interventions chirurgicales des patients. Dans tous les cas, ils ont établi au moins une cause objective de douleur. Ils ont défini la réus-site du traitement comme un soulagement à long terme de la douleur d’au moins 50 %, maintenu pendant la première année de suivi. Ils ont consigné la répartition finale des patients : bons résultats grâce à un traitement prudent, nouvelle intervention chirurgicale et traitement palliatif à l’aide de dispositifs implantables.

RÉSULTATS :

Sur les 122 patients participants, 59,84 % ont subi une opération appareillée et 40,16 %, une opération non appareillée. La plupart (64,75 %) profitaient d’un soulagement marqué de la douleur à l’aide de traitements cliniques classiques de la douleur, et 15,57 % ont dû subir un traitement chirurgical. La stimulation palliative de la moelle épinière et l’analgésie rachidienne ont été utilisées dans 9,84 % et 2,46 % des cas, respectivement. La fibrose péridurale était le diagnostic le plus courant, suivie d’une hernie discale, d’une sténose globale ou latérale, puis d’une sténose du foramen.

CONCLUSIONS :

Des chercheurs ont analysé une nouvelle approche graduée en six étapes de la prise en charge d’une grave SÉPCR qui inclut l’épiduroscopie analysée. Ils ont décrit les étiologies avec précision et confirmé le rôle utile de l’épiduroscopie.

Failed back surgery syndrome (FBSS), postlumbar surgery syndrome, postlaminectomy syndrome or failed back syndrome are terms used to describe patients who have undergone lumbar spine surgery with unsatisfactory outcomes. It should be properly referred to as ‘back surgery with persistent pain syndrome’ because pain persistence is, in fact, the common feature in these patients.

Presumed causes of FBSS include epidural fibrosis, canal stenosis (global or lateral), foraminal stenosis, retained disc fragment, recurrent disc herniation, spinal instability, facet joint pain, sacroiliac joint pain, discitis, arachnoiditis and others (1–3). The rate of FBSS can range from 10% to 50%, depending on the evaluation criteria used. On the other hand, success rates may fall to approximately 30% after the second surgery and 15% after the third (4).

Epiduroscopy is a relatively new, minimally invasive endoscopic technique that allows diagnostic and therapeutic approaches in FBSS. Epiduroscopy can offer a better understanding of the cause of pain and improve the quality and efficacy of drug injections or lysis of adhesions when needed (5). It can be performed via caudal or interlaminar routes (6). Although the effectiveness of spinal endoscopic adhesiolysis has been proven (7,8), the appropriate use of epiduroscopy in the process of diagnosis and treatment of patients with FBSS is not clear.

There are no controlled studies to guide the physician in the management of FBSS, and retrospective data are also limited (9,10). Results in the literature are confusing and most of the works analyze the relative efficacy of isolated interventional procedures (11,12).

In the current article, we present the results of a prospective study testing our algorithm of FBSS management, including epiduroscopy, with a long-term follow-up period of one year. We accurately evaluated the different causes of pain and the final outcome of each patient. The potential of epiduroscopy as a diagnostic and therapeutic tool is evaluated and its place in the algorithm of management FBSS discussed.

METHODS

The present observational study was performed over a two-year period at the Pain Clinic, Hospital Universitario de Madrid and Hospital Sanitas La Moraleja, Madrid, Spain. The management protocol was approved by the institutional research ethics board. At the end of the study, data were retrospectively collected and analyzed (from the prospectively collected databases). Patients (≥18 years of age) with a history of severe FBSS (visual analogue scale score ≥7), defined as back pain or pain in the distribution of a lumbar nerve root with or without lumbar pain, were included. Duration of pain was at least six months from the last surgery. All patients selected in the present study had received conventional pharmacological treatments including multimodal analgesia (opioids, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and coadjuvants) and physical therapy. Exclusion criteria were pregnancy, malignancy, morbid obesity, previous treatment in other pain clinics, workers’ compensation claims and history of stroke. The patients accepted the protocol of study and written informed consent was obtained. Patients were followed up for ≥1 year.

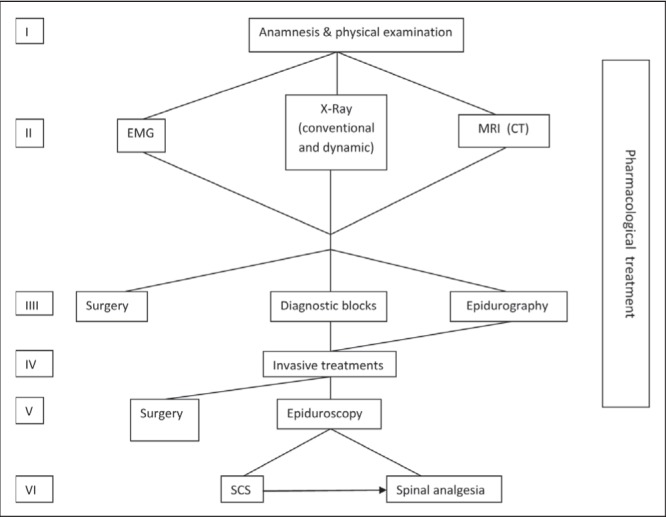

The following six-step algorithm was used in all cases (Figure 1):

The approach to the patient started with a clinical history and physical examination investigating clues to the origin of persistent back pain and evidence of radicular involvement.

Imaging studies included, in all cases, conventional and dynamic lumbar x-ray, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and/or computed tomography when needed or when MRI was contraindicated. If radicular pain was present, electromyography was conducted. Others studies, such as gammagraphy, vertical and dynamic MRI, evoked potentials and blood sampling, were performed when needed (suspicion of instability, cord compression or discitis, respectively).

Common invasive diagnostic procedures used were epidurography, nerve root blocks, facet blocks and blocks of the medial branch nerves, sacroiliac blocks and hip blocks.

Invasive treatments included the most common approaches in interventional back pain management, eg, epidural blocks (interlaminar or transforaminal), facet blocks (articular or medial branch technique), epidurolysis, caudal epidural blocks, radiofrequency (conventional and pulsed), paravertebral muscle blocks, sacroiliac joint injections and temporary epidural catheters with patient-controlled analgesia systems.

Epiduroscopy (via interlaminar or caudal) was used when all conventional treatments failed, eg, epidural fibrosis with no response to conventional epidurolysis with the Racz technique, or when there was persistent pain without final diagnosis in spite of all previous procedures used.

Patients with no response to all previous treatments and without surgical indication underwent palliative treatment with spinal cord stimulation (SCS) or spinal analgesia.

Figure 1).

Six-step algorithm of failed back surgery syndrome management. CT Computed tomography; EMG Electromyography; MRI Magnetic resonance imaging; SCS Spinal cord stimulation

In all cases, one or more objective cause(s) of pain were established as a result of data obtained from clinical, radiological and neurophysiological explorations, or epiduroscopy findings.

Treatment success was defined as ≥50% long-term pain relief maintained during the first year of follow-up. Data are expressed as mean (range) or percentage.

RESULTS

The initial study population consisted of 133 patients. Eleven patients did not complete the one-year follow-up in the authors’ pain clinic and were not included in the study. Of the 122 patients enrolled in the present study, 69 (56.56%) were women and 53 (43.44%) were men. The mean age was 57.9 years (range 19 to 82 years).

Patients were referred to the authors’ centre by different physicians (neurosurgeons and orthopedic surgeons) from Madrid (72.13%), from other cities in Spain (22.13%) and from other countries (5.74%). The authors’ hospital provided approximately >18% of all patients enrolled. Seventy-three (59.84%) patients had received instrumented surgery and 49 (40.16%) noninstrumented surgery.

The most common symptom of consultation was “leg or sciatic pain” (86.89%). Low back pain without radiculopathy was present in only 13.11% of patients. According to electromyographic studies, most cases had L5 root damage (67.21%), followed by S1 (52.46%) and L4 (8.20%). The visual analogue scale (VAS) score was 7.68 (range 7 to 9).

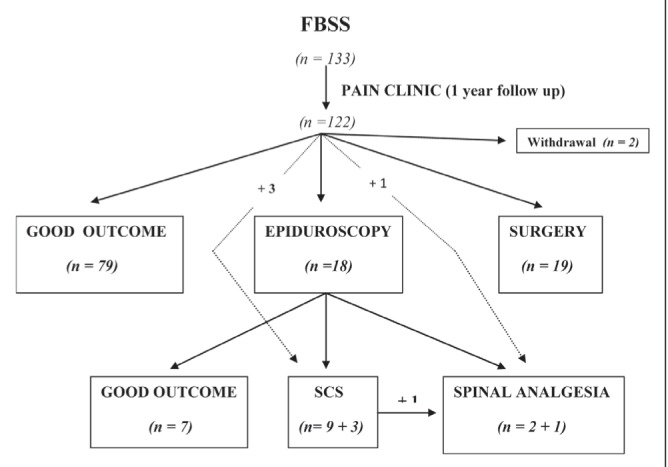

Figure 2 describes the flow chart of patients in the present study and their final prognosis. Most (64.75%) achieved significant pain relief (>50% reduction in VAS maintained during a one-year follow-up period) with conventional treatments at the pain clinic. A total of 15.57% required surgical treatment, including two patients who required total hip arthroplasty due to severe coxarthrosis (Table 1). Of 18 patients who underwent epiduroscopy, seven (5.74% from the study population) achieved adequate relief. SCS devices were used in 9.84% and spinal analgesia was applied in only 2.46% of patients. Two patients considered for surgical reintervention or palliative treatment rejected any treatment and did not continue the study. Three patients were directly recommended for SCS: two were elderly patients with evidence of stenosis who were rejected by two surgeons for a new surgical procedure, and the other had epidural fibrosis and refused epiduroscopy. One patient was directly recommended for spinal analgesia: he had a pacemaker and global spinal stenosis, and surgical treatment had been previously rejected.

Figure 2).

Flow chart of patients. FBSS Failed back surgery syndrome; SCS Spinal cord stimulation

TABLE 1.

Diagnosis of patients who underwent surgical reintervention

| Diagnosis | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Disc prolapse/herniation | 7 (36.84) |

| Stenosis (central or lateral) | 6 (31.58) |

| Instability | 5 (26.32) |

| Foraminal stenosis | 8 (15.79) |

| Coxarthrosis | 2 (10.53) |

Percentage is calculated using the total number of patients. The total percentage is >100%. There were 19 patients submitted to surgery with 28 diagnoses

There were several minor complications: three patients experienced postdural puncture headache (two after conventional epidurolysis and the other one after epiduroscopy) and required hospital admission for two to four days. No postprocedure infection or major complications were observed.

Final diagnosis of the causes of pain persistence were established based on clinical, radiological and epiduroscopy findings. Patients had more than one diagnosis in many cases. Epidural fibrosis was the most common diagnosis (39.34%), followed by disc herniation (22.13%), global or lateral canal stenosis (16.39%) and foraminal stenosis (6.56%) (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Etiologies of failed back surgery syndrome

| Diagnosis | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Epidural fibrosis | 48 (39.34) |

| Disc prolapse/herniation | 27 (22.13) |

| Stenosis (central or lateral) | 20 (16.39) |

| Foraminal stenosis | 8 (6.56) |

| Facet syndrome | 8 (6.56) |

| Instability | 5 (4.10) |

| Arachnoiditis | 4 (3.28) |

| Trocanteritis | 4 (3.28) |

| Sacroileitis | 2 (1.64) |

| Vertebral collapse | 2 (1.64) |

| Discitis | 2 (1.64) |

| Coxarthrosis | 2 (1.64) |

| Myofascial pain | 1 (0.82) |

Percentage is calculated using the total number of patients. The total percentage is >100%. There were 122 patients with 133 diagnoses

DISCUSSION

FBSS is a clinical problem consisting of numerous surgical and nonsurgical etiologies. There are no systematic studies to guide the physician in its treatment. The first step in the management of pain is to determine its etiology because the choice of the most appropriate treatment depends on the cause of the persistent pain. We propose a six-step algorithm for FBSS management including a rational use of diagnostic and therapeutic procedures. In the present study, we included epiduroscopy as a useful tool in the treatment of these patients.

Our study was performed at a single private institution; however, we received patients from different hospitals in our country, and from other countries. Patients were referred to us by both neurosurgeons and orthopedic surgeons. Consequently, a possible bias due to involvement of a single hospital was avoided.

There are many studies examining the etiologies of FBSS with different results; however, most are retrospective and were not the result of a systematic management of these patients. The list of causes of FBSS is extensive. The most common causes listed are spinal stenosis, herniated disc and epidural fibrosis (3). In our study, epidural fibrosis was the most common cause of pain persistence. The diagnosis of epidural fibrosis after back surgery is usually made using MRI with gadolinium; however, this technique may not accurately diagnose the presence of epidural adhesions (13). Epidurography and epiduroscopy, as used in our study, can offer a better diagnosis of epidural scarring. On the other hand, epidural fibrosis also occurs in patients who respond well to back surgery. When epidural fibrosis is a major cause of pain, the patients report pain on manipulation in areas of fibrosis and they describe it as very similar to their usual pain.

Currently, provocative discography is not usually used in our pain clinic. It was not included in our algorithm because of its uncertain reliability as a diagnostic procedure.

In our study, most patients (65%) had good outcome with usual treatments applied in a conventional pain clinic setting, >15% required surgical treatment and, finally, <6% improved with epiduroscopy.

Most patients who needed surgical treatment exhibited disc pathology or stenosis with poor or no response to conventional treatment (epidural blockades, radicular blocks) (Table 1). Interestingly, two patients experienced a previously unknown severe coxarthrosis and were operated for hip replacement, with very good outcomes.

Following our algorithm, only 18 patients required epiduroscopy. We suggest that this technique is indicated only in cases of epidural fibrosis with poor outcome with conventional treatments (including epidurolysis) and in patients without a clear diagnosis. The cause of pain was resolved in seven patients (38.9%). This result is similar to other series published by our group (6,14) and others (15). Epiduroscopy, used as a last resort in the management of FBSS, solves <40% of the cases. However, these cases are patients who would need expensive devices (SCS, spinal pumps) for palliative pain treatment. From another point of view, in our study, 15 patients needed SCS or spinal analgesia, but seven other patients who would have required the same treatment successfully recovered after epiduroscopy. Moreover, in all cases, epiduroscopy offered an accurate diagnosis of pathologies such as epidural fibrosis extension and severity, inflammation, arachnoiditis and root hypotrophia.

A recent review by Kallewaard et al (16) confers a positive recommendation for epiduroscopy based on the published evidence for FBSS treatment, and also proposes a clinical pathway that includes epiduroscopy as a final step before palliative procedures, such as spinal cord stimulation or intrathecal drug delivery, as we have recommended.

There is a growing body of research indicating that psychosocial factors can strongly influence spine surgery outcome. A number of studies have shown that spinal surgery outcome is worse in patients receiving workers’ compensation and disability payments (17). These patients were excluded from the present study for this reason. However, a possible limitation to the present study is that a psychological screening for detection of other psychosocial factors contributing to poor outcome was not performed.

FBSS is a major clinical problem and there are currently no standards regarding the management of these patients. In the present study, we analyzed the long-term results of an algorithm of FBSS management that includes epiduroscopy. Etiologies were accurately described and the role of epiduroscopy in patients refractory to conservative therapy and minimally invasive therapeutic procedures was supported.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES: No support has been received. No benefits in any form have been or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Waguespack A, Schofferman J, Slosar P, Reynolds J. Etiology of long-term failures of lumbar spine surgery. Pain Med. 2002;3:18–22. doi: 10.1046/j.1526-4637.2002.02007.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Slipman CW, Shin CH, Patel RK, et al. Etiologies of failed back surgery syndrome. Pain Med. 2002;3:200–14. doi: 10.1046/j.1526-4637.2002.02033.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schofermann J, Reynolds J, Herzog R, Covington E, Dreyfuss P, O’Neill C. Failed back surgery: Etiology and diagnostic evaluation. Spine J. 2003;3:400–3. doi: 10.1016/s1529-9430(03)00122-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hazard RG. Failed back surgery syndrome: Surgical and non-surgical approaches. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2006;443:228–32. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000200230.46071.3d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Trescot AM. Diagnostic spinal endoscopy. Seminars in Anesthesia, Perioperative Medicine and Pain. 2003;3:186–96. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Avellanal M, Diaz-Reganon G. Interlaminar approach for epiduroscopy in patients with failed back surgery syndrome. Br J Anaesth. 2008;101:244–9. doi: 10.1093/bja/aen165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hayek SM, Standford H, Benyamin RM, Singh V, Bryce DA, Smith HS. Effectiveness of spinal endoscopic adhesiolysis in post lumbar surgery syndrome: A systematic review. Pain Physician. 2009;12:419–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Takeshima N, Miyakawa H, Okuda K, et al. Evaluation of the therapeutic results of epiduroscopic adhesiolysis for failed back surgery syndrome. Br J Anesth. 2009;102:400–7. doi: 10.1093/bja/aen383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martin BI, Mirza SK, Comstock BA, Gray DT, Kreuter W, Deyo RA. Reoperation rates following lumbar spine surgery and the influence of spinal fusion procedures. Spine. 2007;32:382–7. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000254104.55716.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ragab A, deShazo RD. Management of back pain in patients with previous back surgery. Am J Med. 2008;121:272–8. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Datta S, Manchikanti L, Falco FJ, et al. Diagnostic utility of selective nerve root blocks in the diagnosis of lumbosacral radicular pain: Systematic review and update of current evidence. Pain Physician. 2013;16:SE97–SE124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van Kleef M, Mekhail N, van Zundert J. Evidence-based guidelines for interventional pain medicine according to medical diagnoses. Pain Practice. 2009;9:247–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1533-2500.2009.00297.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bosscher HA, Heavner JE. Incidence and severity of epidural fibrosis after back surgery: An endoscopic study. Pain Practice. 2010;10:18–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1533-2500.2009.00311.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fai KR, Engleback M, Norman JB, Griffiths R. Interlaminar approach for epiduroscopy in patients with failed back surgery syndrome. Br J Anaesth. 2009;102:280. doi: 10.1093/bja/aen371. author reply 280–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Manchikanti L, Singh V, Falco FJ, et al. Spinal endoscopic adhesiolysis in postlumbar surgery syndrome: An update of assessment of evidence. Pain Physician. 2013;16:SE151–SE184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kallewaard JW, Vanelderen P, Richardson J, Van Zundert J, Heavner J, Groen GJ. Epiduroscopy for patients with lumbosacral radicular pain. Pain Practice. 2014;14:365–77. doi: 10.1111/papr.12104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Greenough CG, Fraser RD. The effects of compensation on recovery from low-back injury. Spine. 1989;12:765–71. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198909000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]