Abstract

Recently, we identified a fimbrial usher gene in uropathogenic Escherichia coli strain CFT073 that is absent from an E. coli laboratory strain. Analysis of the CFT073 genome indicates that this fimbrial usher gene is part of a novel fimbrial gene cluster, aufABCDEFG. Analysis of a collection of pathogenic and commensal strains of E. coli and related species revealed that the auf gene cluster was significantly associated with uropathogenic E. coli isolates. For in vitro expression analysis of the auf gene cluster, RNA was isolated from CFT073 bacteria grown to the exponential or stationary phase in Luria-Bertani broth and reverse transcriptase PCR (RT-PCR) with oligonucleotide primers specific to the major subunit, aufA, was performed. We found that aufA is expressed in CFT073 only during the exponential growth phase; however, no expression of AufA protein was observed by Western blotting, indicating that under these conditions, the expression of the auf gene cluster is low. To determine if the auf gene cluster is expressed in vivo, RT-PCR was performed on bacteria from urine samples of mice infected with CFT073. Out of three independent experiments, we were able to detect expression of aufA at least once at 4, 24, and 48 h of infection, indicating that the auf gene cluster is expressed in the murine urinary tract. Furthermore, antisera from mice infected with CFT073 reacted with recombinant AufA in an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. To identify the structure encoded by the auf gene cluster, a recombinant plasmid containing the auf gene cluster under the T7 promoter was introduced into the E. coli BL-21 (AI) strain. Immunogold labeling using AufA antiserum revealed the presence of amorphous material extending from the surface of BL-21 cells. No hemagglutination or cellular adherence properties were detected in association with expression of AufA. Deletion of the entire auf gene cluster had no effect on the ability of CFT073 to colonize the kidney, bladder, or urine of mice. In addition, no significant histological differences between the parent and aufC mutant strain were observed. Therefore, Auf is a uropathogenic E. coli-associated structure that plays an uncertain role in the pathogenesis of urinary tract infections.

Uropathogenic Escherichia coli (UPEC) strains are responsible for 70 to 90% of the seven million cases of acute cystitis and 250,000 cases of pyelonephritis reported annually in the United States (13). These strains, also known as extraintestinal pathogenic E. coli, differ from commensal E. coli because they possess specific virulence factors that allow them to colonize host mucosal surfaces, to circumvent host defenses, and to invade the normally sterile urinary tract. Unfortunately, surprisingly few of the many putative virulence factors that might contribute to the propensity of UPEC strains to cause acute urinary tract infections (UTIs) have been verified according to the criteria of molecular Koch's postulates in animal studies. Among these proven virulence factors are type 1 fimbriae, the iron-transporting outer membrane protein TonB, the transcriptional regulator RfaH, and the toxin cytotoxic necrotizing factor 1 (1, 3, 7, 32, 35, 40). Thus, very little is known about the pathogenesis of UPEC infection.

Successful colonization of the bladder and kidney is presumed to be critical to the establishment of UTIs by UPEC and other uropathogens and may be mediated by fimbriae. Fimbriae that have been epidemologically associated with UPEC strains include type 1 fimbriae, P fimbriae, S fimbriae, and the Dr family of adhesins (4, 9).

Type 1 fimbriae are found among other genera of the family Enterobacteriaceae and are a proven virulence factor for E. coli in the urinary tract. These fimbriae bind to mannose-containing oligosaccharides found on host glycoproteins, such as the Tamm-Horsfall protein secreted by the human bladder mucosa and uroplakins deposited on the uroepithelial cell surface in the lower urinary tract, via the FimH adhesive tip protein. Connell et al. (7) demonstrated that a mutation within the fimH adhesin gene of a clinical isolate reduced its virulence in the mouse urinary tract and that virulence could be restored by complementation with a plasmid containing a functional fim operon. Using signature-tagged mutagenesis, we identified several independent attenuated mutants of the pyelonephritogenic strain of E. coli, CFT073, which had insertions in the fim operon encoding type 1 fimbriae (3). These fim mutants were outcompeted approximately 1,000-fold by the wild-type strain in the mouse urinary tract. In addition, the regulation of type 1 fimbriae by an invertible element is also important for UTIs. This invertible element contains the promoter responsible for transcription of the structural subunit gene (fimA) and other accessory genes required for the assembly of type 1 fimbriae (1). During the course of UTIs, this element switches between phase on and phase off and is controlled by recombinases FimB and FimE (14, 27, 39). A locked-off mutant of CFT073 was phenotypically incapable of expressing type 1 fimbriae and was attenuated as compared to wild-type CFT073, while a locked-on mutant constitutively expressed type 1 fimbriae and demonstrated enhanced colonization as compared to the wild-type strain (15). Moreover, we showed that a fimB promoter mutant was retarded in its ability to turn the invertible element from the off phase to the on phase and was at a disadvantage relative to the wild-type strain in colonization of the mouse urinary tract (3). Therefore, the ability to modulate expression of type 1 fimbriae is important for the pathogenesis of UTI.

Expression of P fimbriae is mainly associated with pyelonephritogenic isolates of UPEC. P fimbriae mediate binding to the glob series of αGal(1-4)βGal-containing glycolipids (6, 28). The specific role of P fimbriae as a colonization factor in the urinary tract remains to be fully elucidated. In an experimental primate model, a pyelopnephritic UPEC isolate persisted in the urinary tract significantly longer than a papG mutant strain and caused pyelonephritis at a higher frequency (36). However, no difference in bladder colonization was observed between the papG mutant and wild-type strain, and genetic complementation was not performed. Moreover, Mobley et al. (31) constructed an isogenic mutant that had deletions of the tip adhesins encoded by both copies of the pap operon found in E. coli CFT073, but could find no difference between the ability of this mutant and that of wild-type E. coli CFT073 to colonize the kidneys, bladder, and urine in the mouse urinary tract after 1 week. Using volunteers, it was shown that E. coli strain 83972 transformed with the pap gene operon colonized better and established bacteriura faster than wild-type E. coli 83972 (44). E. coli 83972 is a clinical isolate associated with asymptomatic bacteriuria and harbors the pap and fim operons; however, expression of functional type 1 and P fimbriae under in vivo or in vitro conditions has not been detected (2, 19, 28). Recently, it was demonstrated that isogenic papG and papG fimH mutants of E. coli 83972 maintained the capacity to colonize the human bladder after 3 months, suggesting that neither P nor type 1 fimbriae are required for persistence of this E. coli strain in the human urinary tract (18).

The fact that pap and fim mutants are still able to colonize and to survive in the human, mouse, and primate urinary tracts suggests that additional fimbrial systems or other adhesins are required for the colonization and/or persistence and virulence of E. coli in the urinary tract. In a previous study aimed at identifying genes present in E. coli strain CFT073 but absent from E. coli K-12, we reported the identification of a novel fimbrial usher gene (5). Using data obtained from the genome sequence of E. coli CFT073, we determined that this novel usher gene is part of a fimbrial gene cluster we term auf. In this study, we describe the molecular cloning and characterization of the auf gene cluster and assess the role of Auf in UTIs by using a murine model of ascending infection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, media, and growth conditions.

The principal bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. E. coli strain CFT073 was isolated from the blood and urine of an otherwise healthy woman with the clinical syndrome of acute pyelonephritis admitted to the University of Maryland Medical Center. CFT073 is highly virulent in the murine urinary tract (30). The non-E. coli enteric strains and diarrheagenic E. coli strains used in this study have been described previously (26). Pyelonephritis, catheter-associated, and fecal isolates used in hybridization studies were kindly provided by Harry Mobley (University of Maryland), and cystitis isolates were provided by A. Stapleton (University of Washington) and have been described previously (24, 38). Bacteria were stored at −70°C in 50% Luria-Bertani (LB) broth and 50% glycerol and were routinely grown at 37°C in LB broth or on Luria agar supplemented with appropriate antibiotics. Antibiotics were used at the following concentrations unless otherwise indicated: ampicillin, 50 μg/ml; chloramphenicol, 50 μg/ml; kanamycin, 50 μg/ml; nalidixic acid, 50 μg/ml; and rifampin, 50 μg/ml.

TABLE 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this study

| E. coli strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristics | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli strains | ||

| CFT073 | Pyelonephritis isolate, fim+pap+hly+ | 31 |

| CFT073Rif | Spontaneous rifampin-resistant mutant of CFT073 | This study |

| UMD100 | CFT073 aufC::pSSP104, ampicillin resistant | This study |

| UMD132 | CFT073 Δ(aufABCDEFG), nalidixic and chloramphenicol resistant | This study |

| UMD133 | CFT073 Δ(aufABCDEFG), nalidixic resistant | This study |

| ORN172 | Δ(fimBEACDFGH), kanamycin resistant | 43 |

| HB101 | F− (gpt-proA)62 leu supe44 ara-14 galK2 lacY1 (mcrC-mrr) rpsL20 xyl-5 mtl-1 recA13 | 37 |

| TOP10F′ | F′[lacIq Tn10(TetR)] mrcA Δ(mrr-hsdRMS-mrcrBC) φ80 lacZΔM15 ΔφlacX74 recA1 araD139 Δ(ara-leu)7697 galU galk rpsL(Strr) endA1 nupG | Invitrogen |

| BL21-AI | F−ompT hsdSB(rB−mB−) gal dcm (DE3) araB::T7RNAP-tetA | Invitrogen |

| BL21 (DE3)pLysS | F−ompT hsdSB(rB−mB−) gal dcm (DE3) pLysS (Camr) | Invitrogen |

| S17-λ pir | pro thi recA hsdR; chromosomal RP4-2 (Tn1::ISR1 tet::Mu Km::Tn7); λpir | 17 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pcosmid 12A | Cosmid clone of CFT073 that contains the entire auf operon | |

| pELB1 | pCRScript Cam (SK+) with the 8.6-kb BsiWI/KasI fragment containing the auf operon | This study |

| pELB2 | pBlueScript-II KS(+) with the 9-kb NotI/XhoI fragment containing auf operon under T7 promoter control | This study |

| pAufA | pCR T7/NT-TOPO with the aufA gene lacking the codons for the signal sequence | This study |

| pPCRScript Cam (SK+) | Cloning vector, chloramphenicol resistant | Stratagene |

| pBlueScript-II KS (+) | Cloning vector, ampicillin resistant | Stratagene |

| pCR T7/NT-TOPO | Cloning vector, ampicillin resistant | Invitrogen |

| pGP704 | Suicide vector, ampicillin resistant, R6K origin | 29 |

| pT-Aadv | Cloning vector, ampicillin resistant | Clonetech |

| pSSP102 | pT-Adv with the 1.2-kb aufC fragment | Stratagene |

| pSSP104 | pGP704 with the 1.2-kb XabI/KpnI aufC fragment, ampicillin resistant | This study |

| PKD46 | Low-copy-number plasmid encoding the phage λ Red recombinase expressing γ, β, and exo from the arabinose-inducible ParaB | 8 |

| pFT-A | Helper plasmid, carrying the FLP recombinase, ampicillin resistant | 34 |

| pKD3 | Plasmid containing an FRT-flanked cat gene, ampicillin and chloramphenicol resistant | 8 |

Recombinant DNA methods.

All DNA manipulations were carried out by standard procedures (37). The enzymes and chemicals used for DNA manipulation were purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, Calif.) and New England Biolabs (Beverly, Mass.). DNA fragments used in the cloning procedures and PCR products were isolated from agarose gels with the Quiaquick gel extraction kit (QIAGEN, Ltd.). Plasmid DNA from E. coli was isolated and purified with a Wizard Plus minipreps DNA purification system (Promega) or a QIAGEN plasmid midi kit. Plasmids were introduced into E. coli by electroporation or by chemical methods. Primers used in this study were synthesized at the University of Maryland School of Medicine Biopolymer Laboratory (Baltimore, Md.) and are listed in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Oligonucleotides used in this study

| Oligonucleotide | Sequence |

|---|---|

| Buckles 7 | 5′-CCACCAATCTGAACGGAACGCCTAC-3′ |

| Buckles 9 | 5′-GAGATATAACTTATTAACGCAG-3′ |

| Donne 464 | 5′-TTGGCCAATATCGAGGCAATAGC-3′ |

| Donne 465 | 5′-GTTTGACTCGGAGAAACATCACC-3′ |

| Donne 470 | 5′-GTGGGAAGTGATATCCAGTTCAGT-3′ |

| Donne 473 | 5′-GACAGTGTTAGTATTCGTGGCAT-3′ |

| Donne 476 | 5′-CACATGTGGAATTGTGAGCGGAT-3′ |

| Donne 477 | 5′-CGAAAAGTGCCACCTGCAGATCT-3′ |

| Donne 538 | 5′-GCAGTTGGCAATCGTAATATCCACGC-3′ |

| Donne 539 | 5′-GTTATATGTGAGTATAAACTCACTTATTGCGGCTTTG-3′ |

| Donne 591 | 5′-CTCGTACAGCACAACGGGACTTGCTGTTG-3′ |

| Donne 592 | 5′-GCACCCGGCGATGCAACACAATTTGG-3′ |

| Donne 607 | 5′-GGTCGCATCCGCATTAGCAGCACCTGGG-3′ |

| Donne 608 | 5′-GCCGCTTGCGCAGTTGATGCAGGCTCTG-3′ |

| Donne 619 | 5′-CCTCTTCGCTGATCTCCTCGCCGAACAG-3′ |

| Donne 620 | 5′-GGTTCGCAAGCCGACCCTGGACCTTCCGC-3′ |

| Donne 777 | 5′-GCATTATAACGACCTGCCGCAGGCAC-3′ |

| Donne 813 | 5′-CAGAATGTAAAAACACCAATGTTGCTTGGATTTTTTAACAAAAGGAAAGGTATAAATGTGTGTAGGCTGGAGCTGCTTCG-3′ |

| Donne 814 | 5′-CAGTTGTACTAACAGGTAAAGTCAGAAAAGTAACATCAGCAGTTTGCGCAGAAGCAGCCTACATATGAATATCCTCCTTAG-3′ |

| Donne 953 | 5′-GGGGCGAGAACGTGCATATTGTTATCCGGG-3′ |

RNA isolation and RT-PCR.

Total RNA was isolated from bacteria by using the RNeasy Mini kit (QIAGEN, Ltd.). Contaminating DNA was digested with the RNase-free DNase kit (Ambion) according to the manufacturer's instructions. cDNA was then synthesized from total RNA by using Ready-To-Go reverse transcriptase PCR (RT-PCR) beads in the one-step protocol according to the manufacturer's instructions (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). As a negative control, a reaction tube heated at 95°C for 10 min to inactivate the RT was included to test for DNA contamination of the RNA sample. In addition, the genes in question were amplified from genomic DNA by PCR, using the same primers as a positive control of the PCR to ensure the presence of sufficient bacteria for amplification and as a size marker. The primers used for RT-PCR were locus specific for aufA (Donne 591 and Donne 592), aufG (Donne 953 and Buckles 7), fimA (Donne 607 and Donne 608), and uphT (Donne 619 and Donne 620).

Identification of auf cosmid clones and subcloning of the auf operon.

A previously described genomic library of CFT073 chromosomal DNA, consisting of size-fractionated DNA partially digested with Sau3A cloned into pHC79 and packaged in vitro, was screened for the presence of the auf operon by PCR (31). The CFT073 genomic library consists of ∼1,824 clones arranged in 19 microtiter plates. The PCR primers used for screening, Donne 539 and Donne 538, correspond to sequences located approximately 1 kb upstream and downstream of the auf operon. In the initial PCR round, the 96 clones from each plate were pooled, plasmid DNA was isolated, and PCR was performed by using the eLongase enzyme system to identify plates containing auf cosmid clones. After identification of positive plates, plasmid DNA was then prepared and pooled from each row and each column of positive plates and PCR amplified to locate the auf cosmid clones. Cosmid clone 12A containing auf sequences was digested with restriction enzymes BsiWI and KasI. The 8.6-kb BsiWI/KasI fragment containing the auf operon was isolated from an agrose gel, the ends were polished with Pfu polymerase, and the fragment was ligated into the pCRScript Cam SK(+) cloning vector to yield pELB1. Plasmid pELB1 was then digested with NotI and XhoI, yielding an approximately 9-kb fragment containing the auf operon. This fragment was gel purified and ligated into the NotI- and XhoI-digested pBluescript II KS(+). The ligated products were transformed into E. coli TOP10F′ cells, and a recombinant clone, pELB2, containing the auf operon in the same orientation as the T7 promoter, was selected after restriction digest analysis.

Cloning, expression, and purification of AufA recombinant protein.

The pCR T7/NT TOPO TA expression system (Invitrogen) was used to express recombinant AufA. The region of aufA encoding residues 1 to 243 of the mature AufA protein (lacking its putative signal sequence) was amplified from pCosmid 12A by PCR using primers Donne 591 and Donne 592. The PCR product was gel purified, cloned into the vector, and transformed into E. coli TOP10F′ cells. Plasmid preparations from the resultant transformants were analyzed by restriction enzyme digestion to determine the orientation of aufA. A single plasmid, designated pAufA, that allows for expression of an AufA protein containing an N-terminal His tag without the signal sequence was selected.

For expression and purification of AufA, plasmid pAufA was transformed into E. coli BL21(D3E)pLysS according to the manufacturer's instructions and grown overnight in LB medium containing 100-μg/ml ampicillin and 34-μg/ml chloramphenicol at 37°C with shaking. The following day, 200 ml of the same medium was inoculated with 4 ml of the overnight culture and allowed to grow to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.5. Cultures were then induced with 1 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) and grown for another 5 h, and the cells were harvested by centrifugation at 3,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. The pellet was suspended in 10 ml of lysis buffer (50 mM NaH2PO4, 300 mM NaCl, 10 mM imidazole, pH 8.0) and lysed in a French press. Following centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 20 min at 4°C to remove insoluble debris, recombinant His-tagged AufA was initially purified by nickel affinity column chromatography (Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid [NTA] agarose resins; QIAGEN) under native conditions according to the manufacturer's instructions. Fractions (500 μl) were collected and analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and Western blotting with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated anti-HisG and anti-Xpress-HRP antibody (Invitrogen). Following Ni-NTA purification, fractions containing the His-tagged AufA protein were further purified by gel filtration chromatography on a Sephacryl S-200 (16/60 column; Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, N.J.), using phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for elution. Recombinant His-AufA obtained following gel filtration was more than 90% pure, as assessed by silver staining after SDS-PAGE. Protein concentrations were measured with the bicinchoninic acid protein assay kit purchased from Pierce with bovine serum albumin as a standard. Proteins were stored at −20°C until used.

AufA antibody production.

An aliquot of partially purified AufA protein obtained by Ni chromatography was separated on a preparative SDS-PAGE gel. The band corresponding to the His-tagged AufA protein was cut from the gel after Coomassie blue staining. Gel slices were homogenized by passage through a 27-gauge needle with complete Freund's adjuvant (Sigma) and administered subcutaneously to New Zealand White rabbits. Booster immunizations were given three times at 3-week intervals with Freund's incomplete adjuvant. The AufA antisera were extensively preabsorbed with an acetone powder preparation of E. coli BL21(DE3)pLysS containing the pCR T7/NT TOPO vector to remove nonspecific reactivity.

Extraction of surface proteins.

Crude extracts of bacterial surface proteins were prepared as described by Khan and Schifferli (25). BL21-AI cells harboring pELB2 or pBluescript were grown in LB broth for 5 h under induced (0.2% arabinose) or repressed (0.2% glucose) conditions at 37°C with shaking. Bacteria were harvested by centrifugation and resuspended in a solution of 75 mM NaCl-0.5 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4). The cell suspension was incubated for 60 min at 60°C to separate bacterial surface proteins from bacterial cells. After removal of bacteria and debris by centrifugation, thermoeluted proteins were concentrated from the supernatant by precipitation with trichloroacetic acid and dissolved in SDS-PAGE sample buffer.

Proteinase K treatment.

BL21-AI(pELB2) cells were grown under induced or repressed conditions. Following several washes with PBS-5 mM MgCl2, cells were resuspended in PBS-5 mM MgCl2 containing 200-μg/ml proteinase K or in PBS-5 mM MgCl2 and incubated at 37°C for 1 h. Proteinase K treatment was stopped by the addition of phenylmethylsufonyl fluoride (1.6 mg/ml). Following several washes with PBS, bacterial surface proteins were isolated as described above. Supernatants and pellet fractions were then analyzed by immunoblot analysis for the presence of AufA, using anti-AufA antibodies.

SDS-PAGE and immunoblot analysis.

Whole-cell lysates and crude extracts of bacterial surface proteins were denatured by boiling for 5 min in SDS-PAGE sample buffer. Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to an Immobilon P polyvinylidene fluoride membrane by using a semi-dry Multiphor II NovaBlot transfer apparatus (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). After incubation overnight at 4°C in blocking reagent (5% dried skim milk in PBS and 0.1% Tween 20), the membrane was probed with primary antibodies and HRP-conjugated antimouse serum (Sigma) as the secondary antibody when needed. The membranes were thoroughly washed and developed with the enhanced chemiluminescent detection kit (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). The primary antibodies used were anti-AufA (1:5,000), anti-HisG-HRP (1:5,000), anti-Xpress-HRP (1:5,000), and anti-GroEL-HRP (1:80,000).

Dot blot hybridizations and generation of an aufC probe.

A 1.2-kb KpnI/XbaI fragment of the aufC usher gene was labeled by using enhanced chemiluminescence with the ECL RPN3000 kit (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) according to the manufacturer's protocol. For preparation of dot blots, E. coli strains were grown overnight in 100 μl of LB broth in 96-well microtiter dishes. Bacterial cultures were lysed and placed on Hybond-N+ membrane (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). Hybridization and washes were performed as instructed by the ECL kit. E. coli K-12 MG1655 and E. coli CFT073 were used as negative and positive controls, respectively.

Construction of aufC insertion mutants of CFT073.

A suicide vector was used to prepare an aufC insertion mutant strain of CFT073. An internal 1.2-kb KpnI/XbaI fragment of the aufC gene was subcloned from pSSP102 into the KpnI/XbaI site of the suicide vector pGP704, resulting in pSSP104. Plasmid pSSP104 was transformed into E. coli S17 λ pir and mobilized into CFT073 by conjugation. Transconjugates were selected on ampicillin and nalidixic acid plates. Disruption of the aufC was confirmed by Southern hybridization of chromosomal DNA from potential mutants by using a digoxigenin-labeled 1.2-kb KpnI/XbaI aufC fragment as a probe and PCR with the following primer pairs: Donne 477 and Donne 465, Donne 477 and Donne 470, Donne 476 and Donne 473, and Donne 476 and Donne 464. The aufC mutant of CFT073 was designated UMD100.

Construction of auf gene cluster deletion mutants.

To construct mutants of strain CFT073 with deletion of the entire auf gene cluster, the auf gene cluster was replaced with the chloramphenicol resistance gene by using the lambda red recombinase system (8). The chloramphenicol resistance gene was amplified from plasmid pKD3 by PCR using primers Donne 813 and Donne 814. Both primers contain 21 bp of sequence homologous to pKD3 and 54 bp of sequence homologous to regions flanking the auf operon. The PCR product was gel purified, treated with DpnI to remove the pKD3 template, and repurified. The purified PCR product was electroporated into CFT073 containing the lambda red recombinase expression plasmid, pKD46. Electrocompetent CFT073(pKD46) cells were prepared by culturing the bacteria at 30°C in SOB broth containing 100 mM l-arabinose to induce expression of lambda red recombinase. Following electroporation, transformants were recovered at 30°C for 2 h in SOC broth and plated on LB agar containing chloramphenicol for overnight growth at 37°C to select for transformants and to induce the loss of pKD46. Chloramphenicol-resistant colonies were then tested by PCR for replacement of the auf operon by the chloramphenicol resistance marker. To eliminate the chloramphenicol resistance marker, UMD132 was transformed with plasmid pFT-A, which encodes the FLP recombinase under the control of the tetracycline repressor from Tn10. Induction of the FLP recombinase was performed as previously described (34). Briefly, exponentially growing UMD132(pFT-A) cells were supplemented with heat-inactivated chlortetracycline and allowed to grow for an additional 4 h to allow expression of FLP. Cells were plated on LB agar without antibiotics and grown at 37°C to eliminate pFT-A. Elimination of the chloramphenicol resistance marker in strain UMD132 was confirmed by PCR using primers Donne 777 and Buckles 9 and checking selected transformants for chloramphenicol sensitivity. The resulting strain was named UMD133.

Analysis of antibody response to AufA in mice following experimental UTI.

Mice were challenged transurethrally with 109 CFU of wild-type CFT073 or UMD100 and rechallenged on days 16 and 42. Mice were sacrificed and exsanguinated on day 56. An enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) was used to assess immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibody reactivity to the purified His-Auf protein. Ninety-six-well Maxisorb Immunoplates (Nunc, Naperville, Ill.) were coated with 100 ng of purified recombinant protein in 0.1 M Na2HPO4 (pH 9.0) buffer and incubated at 4°C overnight. Plates were then blocked with 10% nonfat dry milk in PBS-0.5% Tween 20 at 4°C overnight. Following several washes, twofold serial dilutions (1/50 to 1/6,400) of sera from CFT073-infected mice were added to each well incubated at 37°C for 1 h. One hundred microliters of goat anti-mouse IgG heavy and light peroxidase conjugate (Sigma) diluted 1:5,000 in 10% nonfat dry milk in PBS-0.5% Tween 20 was added, and the plates were incubated for 1 h at 37°C. The substrate 3,3′,5,5′ tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) (Sigma) was added, the reaction was stopped with 1 M H2SO4 acid, and the absorbance was measured by determining the OD450. The OD450s specific for antibody reactivity to the Auf protein were obtained by subtracting average OD450s for blank wells from average OD450s for Auf proteins. The cutoff value was calculated by determining the mean OD450 + 2 standard deviations that was obtained from preimmune mouse sera. The data reported are the means ± the standard errors of the means from three experiments.

Mouse experimental infections.

A CBA mouse model of ascending UTI was used as described previously (24). Briefly, CBA mice were transurethrally challenged with 108 CFU of bacteria per mouse. After 2 days, the mice were sacrificed and bacteria recovered from the urine, bladder, and kidney were enumerated on plates containing appropriate antibiotics. For cochallenge infections, mice were inoculated with a mixture of 5 × 107 CFU of the wild-type strain CFT073 and 5 × 107 CFU of the mutant (a total of 108 CFU per inoculum), which had been grown separately overnight. After 48 h, urine was collected; bladder and kidneys were removed, weighed, and homogenized; and dilutions were plated on selective media using a spiral plater. After overnight growth, the viable counts were determined as CFU per milliliter of urine or CFU per gram of tissue. As the lower limit of detection was 102 CFU, samples yielding no colonies were scored as having this value. A competitive index was calculated for each mutant as the geometric mean of the ratios of the mutant to the wild-type strains recovered from each sample site divided by the ratios of the mutant to the wild-type strains in the inoculum.

Statistical analysis.

The Mann-Whitney test was used to compare the distributions of the number of CFU per milliliter or gram in independent infection assays and to compare the mean pathology scores of mice challenged with the wild type or the mutant. A repeated measure analysis of variance with rank order data (STATA software) was used for statistical analysis of the cochallenge experimental data as previously described (3). P values of ≤0.05 were considered significant.

Histology.

Kidney and bladder tissues were sectioned and stained with hematoxylin and eosin for histological analysis by light microscopy. The severity of renal pathology was determined by a semiquantitative score of bladder and kidney damage as previously described (16).

Hemagglutination assays.

Hemagglutination assays were performed by a routine procedure using human, sheep, and guinea pig erythrocytes (3).

Electron microscopy.

A carbon-coated Formvar copper grid (300 mesh; Electron Microscopy Sciences) was placed on a drop of bacterial suspension for 2 min. The grid was then negative stained with 1% phosphotungstic acid, washed twice with distilled water, and finally air-dried. For immunoelectron microscopy, bacteria were reacted with anti-AufA antibodies (dilution 1:20) and anti-rabbit IgG (H+L)-gold conjugate (10-nm diameter; diluted 1:200), and stained with 1% phosphotungstic acid. Grids were examined under a JEOL 1200 EX transmission electron microscope.

RESULTS

Identification and properties of a novel fimbrial gene cluster in E. coli CFT073.

Recently, we identified by subtractive cloning a new fimbrial usher gene in pyelonephritogenic E. coli strain CFT073 that is absent from E. coli K-12 (5). This same fimbrial usher gene was also identified in a cystitis strain of E. coli and was shown to be more common among cystitis than fecal strains (46). Since the cloning of this novel usher gene, the sequence of the entire genome of uropathogenic E. coli strain CFT073 has been published (42). Sequence analysis of the region surrounding the novel fimbrial usher gene revealed genes that are predicted to encode chaperone-usher fimbrial biosynthesis systems and resemble members of the type 1 pilus family in their organization. Therefore, we conclude that this novel fimbrial usher gene is part of a novel fimbrial gene cluster in UPEC CFT073 that we term the auf genes.

The auf gene cluster contains seven open reading frames (ORFs), designated aufABCDEFG, with the same transcriptional orientation, which may constitute an operon (Fig. 1). The major features of the auf genes and their putative functions are summarized in Table 3. The auf gene cluster is inserted at 76.7 min relative to the E. coli K-12 chromosome, flanked at the 5′ end by glgP encoding a protein with 97% identity to a glycogen phosphorylase enzyme of E. coli K-12 and at the 3′ end by three ORFs with no homology to E. coli K-12 genes that encode proteins of unknown functions. Further downstream of these ORFs are genes found adjacent to glpD in E. coli K-12. No evidence of tRNA genes, insertion elements, or other mobile genetic elements adjacent to the auf gene cluster was observed. The overall G+C content of the auf gene cluster is 39.98%, which is significantly lower than normally found in E. coli (50.80%). This low G+C content is also common for virulence-associated genes of E. coli and is presumed to indicate a foreign origin.

FIG. 1.

Schematic representation of the organization of the auf gene cluster in the chromosome of E. coli CFT073. The predicated auf genes are shown as arrows with diagonal lines, non-auf and non-E. coli K-12 ORFs are represented by checkered arrows, and solid arrows represent genes shared with E. coli K-12. Arrows indicate transcriptional direction.

TABLE 3.

Properties of the auf genes and deduced proteins

| Gene

|

Deduced protein

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Length (bp) | G+C content (%) | Length (amino acids) | Mass (kDa) | pI | Predicated function |

| aufA | 705 | 47.6 | 234 | 24.2 | 4.1 | Major subunit |

| aufB | 780 | 38.2 | 259 | 29.2 | 10.2 | Chaperone |

| aufC | 2,595 | 41.9 | 864 | 95.7 | 5.6 | Usher |

| aufD | 390 | 40.0 | 129 | 13.7 | 3.9 | Minor subunit |

| aufE | 558 | 35.6 | 185 | 20.0 | 4.4 | Minor subunit |

| aufF | 798 | 38.8 | 265 | 29.8 | 9.9 | Chaperone |

| aufG | 1,011 | 38.4 | 336 | 36.6 | 4.8 | Adhesin |

Prevalence of the fimbrial usher-like gene.

Colony blot hybridization was used to determine whether the usher-related sequence was present in other strains of pathogenic E. coli and in other bacterial species. A 1.2-kb fragment of aufC representing sequences that reside within the bounds of the usher gene was used as the probe to examine 247 strains of E. coli and 8 strains of non-E. coli enteric bacteria. Hybridization showed the presence of the aufC usher gene in 114 of the 247 (46%) E. coli strains tested, whereas none of the non-E. coli enteric strains contained the usher-related sequence (Table 4). Among the E. coli strains, a significantly greater proportion of pathogenic E. coli than fecal isolates yielded a positive result. Among the pathogenic E. coli strains, the aufC sequence was common in UPEC strains, but was no more common among diarrheagenic strains than among strains isolated from the feces of healthy individuals. The distributions of the fimbrial usher-like gene among UPEC strains were as following: 70% for pyelonephritis strains, 51% for catheter-associated strains, and 50% for cystitis strains. It should be noted that the cystitis strains probed in this study are different from those probed by Zhang et al. (46). Thus, aufC is associated with UPEC strains.

TABLE 4.

Prevalence of the aufC gene in E. coli and other Enterobacteriaceae examined by colony blot hybridization

| Source | No. (%) positive/no. testeda |

|---|---|

| All E. coli | 114/247 (46) |

| Non-E. coli enteric strains | 0/8 (0) |

| Fecal E. coli | 9/29 (31) |

| Pathogenic E. coli | 105/218 (48)* |

| UPEC | 89/148 (60)† |

| Non-UPEC pathogenic | 16/70 (23)‡ |

| Pyelonephritis isolates | 49/70 (70) |

| Cystitis isolates | 6/12 (50) |

| Cather-associated isolates | 34/66 (52) |

*, P = 0.112 versus fecal; †, P = 0.003 versus fecal; ‡, P = 0.001 versus UPEC.

Ten of the positive aufC strains were randomly chosen for analysis of the entire auf gene cluster by PCR using primers Donn 589 and Donn 590. A fragment of approximately 8 kb was amplified from all 10 strains (data not shown). In contrast, two probe-negative strains, CFT205 and HB101, yielded no PCR product as expected (data not shown).

Expression and purification of recombinant AufA.

To study the expression of AufA, an antibody to the AufA protein was generated. The aufA gene lacking its signal sequence was amplified and cloned into the pCR T7 NT TOPO TA expression vector (pAufA). The protein was overexpressed in E. coli BL21(DE3)pLysS, and expression of the recombinant fusion protein was examined by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting after induction with IPTG. BL21(DE3)pLysS(pAufA) cells express a protein of approximately 32 kDa, whereas BL21 (DE3)pLysS cells without a plasmid and BL21(DE3)pLysS containing the control expression vector do not express the 32-kDa protein (data not shown). The observed size of the recombinant protein was slightly larger than the predicated mass of AufA, presumably because of the presence of hexahistidine and additional sequences. Because of the additional bands observed after nickel affinity purification, AufA was further purified by gel filtration. Fractions containing the AufA protein were identified by Western blotting with anti-His and anti-Xpress antibodies as probes. The His-AufA protein was purified to >90% homogeneity (data not shown). Purified recombinant AufA was separated by preparative electrophoresis, excised from the gel, and used to immunize New Zealand White rabbits to generate specific antiserum.

Cloning and expression of the auf fimbrial gene cluster.

A CFT073 cosmid libriary was screened for the presence of the entire auf operon by PCR using primers approximately 1 kb upstream and downstream of the operon. Cosmid 12A was selected for expression analysis of the auf fimbrial gene cluster. Cosmid 12A was digested with BsiWI and KasI restriction enzymes, and the 8.6-kb DNA fragment containing the auf gene cluster was cloned into pCRScript cloning vector, to obtain plasmid pEB1 under the lac promoter control. To determine whether cosmid 12A and plasmid pEB1 contain all of the information needed for biogenesis of Auf pili, cosmid12A and pEB1 were introduced into the nonfimbriated E. coli strains ORN172 and HB101. However, no pili were detected by electron microscopy following phosphotungstic acid staining on either ORN172 or HB101 harboring either cosmid 12A or pEB1 (induced with IPTG) (data not shown). The inability to detect fimbriae under these conditions suggests one or more of the following: additional genes may be required for the biogenesis of the Auf fimbriae, the Auf fimbriae are produced at low levels under these conditions, or the auf gene cluster encodes a very thin fimbria or surface structure not revealed by negative staining.

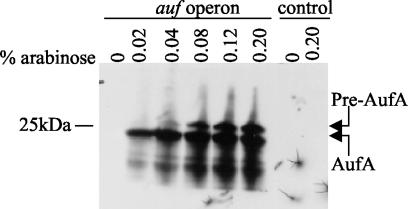

To increase expression of the Auf fimbriae, the auf gene cluster was subcloned into pBluescript II KS+ under the control of the strong T7 promoter, resulting in plasmid pEB2. Plasmid pEB2 was then electroporated into BL21-AI cells. In BL21-AI cells, the T7 RNA polymerase is inserted into the araB locus under the control of the araBAD promoter in the chromosome, thus allowing for tight regulation of the T7 polymerase expression by l-arabinose and glucose. BL21-AI cells containing pEB2 or pBluescript vector were grown overnight in LB broth supplemented with 0.1% glucose to repress basal levels of the T7 polymerase. Crude cell lysates of E. coli strain BL21-AI(pEB2) or BL21-AI(pBluescript) were prepared after continued glucose repression or induction with various concentrations of arabinose and then separated by SDS-PAGE. Western blot analysis showed that the antiserum raised against purified recombinant His-AufA reacted with bands of approximately 23 and 27 kDa from strain BL21-AI(pEB2) under inducing conditions (Fig. 2). These bands presumably represent the prepilin and mature forms of AufA. The antiserum did not react with any bands in BL21-AI(pEB2) grown under glucose repression or with BL21-AI(pBluescript) whether induced or repressed, demonstrating the specificity of the antiserum for AufA.

FIG. 2.

Overexpression of AufA in E. coli BL21-AI. The auf gene cluster was cloned into pBluescript under the control of the T7 promoter and expressed in BL21-AI cells by using various concentrations of arabinose. Glucose (0.2%) was added to the samples lacking arabinose to repress auf expression. Whole-cell lysates of BL21-AI harboring either pELB2 or the control plasmid pBluescript were separated on a SDS-PAGE and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes for Western blotting with absorbed AufA antiserum (1:5,000). The prepilin and mature pilin forms of AufA are indicated by arrows. The position and mass of a molecular mass marker are noted on the left side.

Surface localization and immunogold labeling of AufA.

To determine whether AufA is surface exposed, BL21-AI(pEB2) cells were grown under inducing or repressing conditions and bacterial surface proteins were extracted as described in Materials and Methods. The isolated surface proteins and crude cell lysates were separated on an SDS-PAGE (12% polyacrylamide) gel, and AufA expression was detected by Western blotting with the anti-AufA antiserum. Western blot analysis showed that the bands corresponding to the prepilin and pilin forms of AufA were detected in the cell-associated pellet of BL21-AI(pELB2)-induced cells after incubation at 60°C (Fig. 3A). However, only the mature pilin form of AufA was observed in the supernatants of induced BL21-AI(pELB2) cells incubated at 60°C, suggesting that mature AufA is surface exposed. No bands were observed in the pellets or supernatants of repressed BL21-AI(pELB2) cells or the BL21-AI(pBluescript) control cells after incubation at 60°C. To further confirm that AufA is surface exposed, the susceptibility of AufA on BL21-AI(pELB2) to proteinase K digestion was determined. As shown in Fig. 3B, proteinase K completely digested the mature form of Auf in the supernatants of induced BL21-AI(pELB2), whereas the prepilin and mature forms of AufA in the crude lysates of induced BL21-AI(pELB2) were not affected by proteinase K digestion, thus confirming that AufA is surface exposed. The increased abundance of the prepilin form relative to the pilin form in Fig. 3B was not a consistent finding. As expected, no bands were observed in the pellets or supernatants of repressed BL21-AI(pELB2) cells (data not shown).

FIG. 3.

Surface localization of AufA on E. coli BL21-AI cells. (A) BL21-AI cells harboring either pELB2 or pBluescript were grown under repressed (R) or inducing (I) conditions using 0.2% arabinose. Surface proteins were isolated by heating at 60°C followed by vortexing and centrifugation. Isolated surface proteins (S) and crude cell lysates (P) were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes for Western blotting with absorbed AufA antiserum (1:5,000). (B) Sensitivity of AufA to proteinase K treatment. Induced BL21-AI cells containing the auf operon plasmid were treated with or without proteinase K (200 μg/ml) for 1 h at 37°C followed by the addition of phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (1.6 mg/ml). Surface localization was performed as for panel A. Arrows indicate the prepilin and mature pilin forms of AufA.

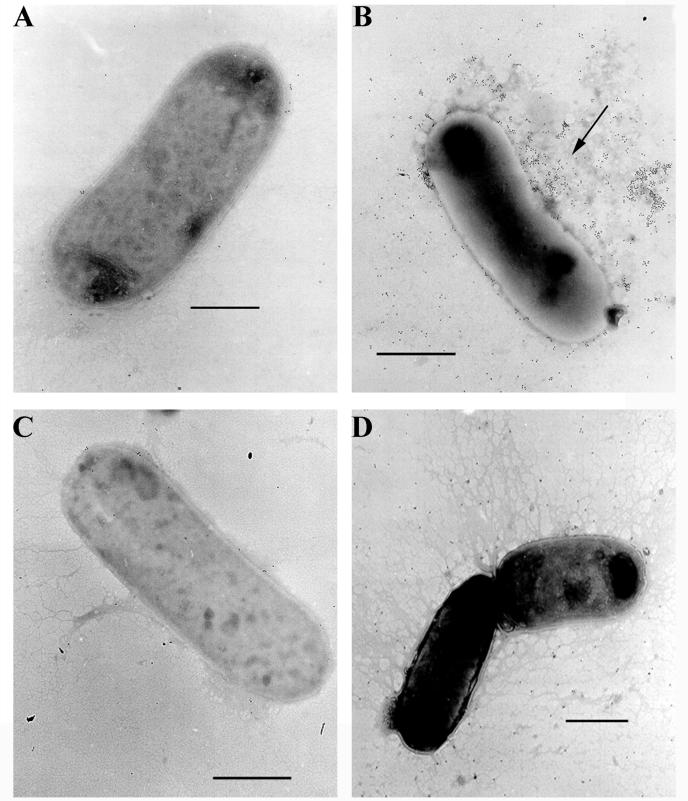

To determine whether AufA is assembled into pili, immunoelectron microscopy was performed. Immunogold labeling with AufA serum showed that gold particles bound to a mesh of amorphous material extending from the surface of BL21-AI(pELB2)-induced cells (Fig. 4). BL21-AI(pELB2)-repressed cells and BL21-AI(pBluescript)-repressed or -induced cells lacked the amorphous material and associated gold labeling. Taken together with the heat extraction and proteinase K digestion experiments, these data show that the auf gene cluster is sufficient to mediate the expression of an amorphous surface structure in E. coli BL21-AI cells and that AufA is a component of this structure.

FIG. 4.

Immunoelectron microscopy of BL21-AI cells expressing Auf. BL21-AI cells harboring either the auf gene cluster plasmid pELB2 (A and B) or the control plasmid pBluescript (C and D) were grown under repressing (A and C) or inducing (B and D) conditions with 0.2% arabinose. Bacteria were reacted first with absorbed AufA antiserum (1:20 dilution) and then with anti-rabbit IgG conjugated to 10-nm-diameter gold particles (1:200 dilution) followed by negative staining with phosphotungstic acid. The arrow in panel B indicates the amorphous material extending from the surface of BL21-AI(pELB2)-induced cells bound by gold particles. BL21-AI(pELB2)-repressed cells and BL21-AI(pBluescript)-repressed or -induced cells lacked the amorphous material and associated gold labeling. Bars represent 1 μm.

Hemagglutination and adherence assays.

Many fimbrial antigens have been shown to agglutinate the erythrocytes of different species. However, induced E. coli BL21-AI cells transformed with pELB2 did not agglutinate erythrocytes from humans, guinea pig, or sheep (data not shown).

To investigate whether the auf gene cluster mediates adherence to epithelial cells, T24 bladder and HEp-2 laryngeal carcinoma cells were incubated with BL21(pELB2) cells or BL21(pBluescript) cells. After 2 h of infection, the cells were fixed, Giemsa stained, and visualized by phase-contract microscopy. We observed no differences in the ability of BL21-AI(pELB2)-induced and -repressed cells and control BL21-AI cells to adhere to T24 and HEp-2 cells in vitro (data not shown).

Analysis of aufA expression by UPEC strain CFT073.

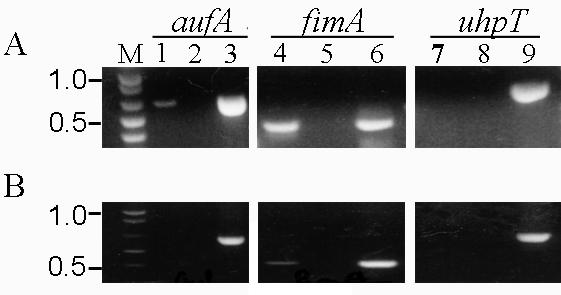

To determine whether the auf operon is expressed by wild-type CFT073, transcription of the aufA gene was examined by RT-PCR. The RT reactions were carried out with specific primers to the aufA gene, using total RNA from exponentially growing or stationary cells. Transcript analyses of fimA, which encodes the major subunit protein of the type 1 pili, and uhpT, which encodes a sugar phosphate transporter, was performed as positive and negative controls, respectively. An aufA transcript was detected only during the exponential growth phase, whereas transcripts for fimA were detected during both the exponential and stationary phases (Fig. 5). No transcript was detected for uhpT during either growth phase in agreement with the finding that the uphT gene is not expressed by E. coli K-12 during the exponential or stationary growth phase in LB broth (41). Control reactions in which the RT was heat inactivated yielded no product, confirming the absence of contaminating DNA. No difference in the amount of aufA cDNA amplified was observed between cells grown in various media at 37 or at 28°C (data not shown). Despite the detection of an aufA transcript, we were unable to detect expression of AufA protein by Western blot analysis using anti-Auf antiserum on crude lysates of wild-type CFT073 grown under the same conditions (data not shown). To exclude the possibility that the lack of fimbrial expression is a characteristic only of strain CFT073, from which the auf gene cluster had been cloned, we investigated 10 other strains of UPEC that were shown to harbor the entire auf gene cluster. As in the case of strain CFT073, we were also unable to detect AufA protein by immunoblot analysis in these strains (data not shown). These results indicate that the aufA gene is transcribed by strain CFT073 under a variety of conditions, but the AufA protein is not expressed at detectable levels under the same conditions.

FIG. 5.

RT-PCR analysis of aufA expression in vitro. Total RNA was extracted from CFT073 grown to the exponential (A) or stationary (B) phase. RT-PCR was performed with specific primers for aufA, fimA, and uhpT (lanes 1, 4, and 7, respectively). As a negative control, each RT-PCR was run with heat-inactivated RT to check for contaminating DNA (lanes 2, 5, and 8). Amplification of each band from CFT073 genomic DNA demonstrated the specificity of the PCR and the size of the expected band for each reaction (lanes 3, 6, and 9).

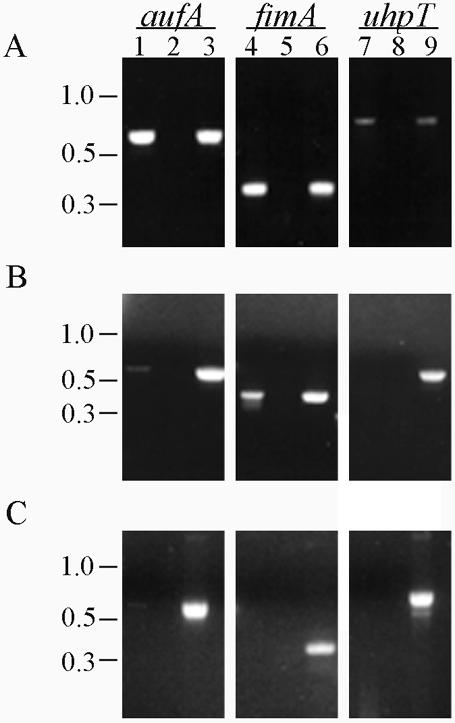

To analyze the expression of aufA in vivo, three series of 10 mice each were infected with 108 CFU from stationary cultures of CFT073, and urine samples were collected at 4, 24, and 48 h. The samples from all 10 mice from each time point were pooled to yield a sufficient number of bacteria for analysis. After centrifugation, total RNA was isolated and RT-PCR was performed as described in Materials and Methods. From three independent experiments, an aufA transcript was detected at least once at each time point, indicating that aufA can be transcribed in the mouse urinary tract (Fig. 6). The fact that an aufA transcript was not detected consistently suggests that aufA transcription may be under complex control or that aufA may be expressed at levels near the limit of detection.

FIG. 6.

RT-PCR analysis of aufA expression in vivo. Total RNA was extracted from combined urine samples of 10 CFT073-infected mice at 4 (A), 24 (B), and 48 (C) h. RT-PCR was performed with specific primers for aufA, fimA, and uhpT (lanes 1, 4, and 7, respectively). As a negative control, each RT-PCR was run with heat-inactivated RT to check for contaminating DNA (lanes 2, 5, and 8). Amplification of each band from CFT073 genomic DNA demonstrated the specificity of the PCR and the size of the expected band for each reaction (lanes 3, 6, and 9).

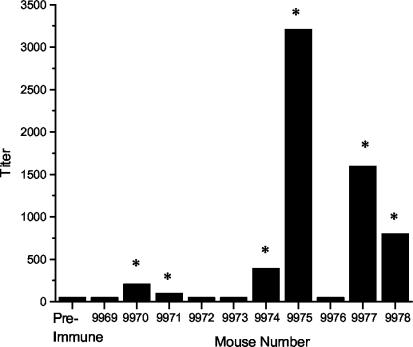

To determine whether AufA is produced during infection of the mouse urinary tract, sera from mice repeatedly infected with either wild type CFT073 or aufC mutant UMD100 (see below) were examined by ELISA for antibodies reactive to purified His-AufA. Sera from 6 of the 10 mice infected with wild-type CFT073 showed a broad range of reactivity to the His-AufA fusion protein above the cutoff values, whereas only 1 out of 10 mice infected with UMD100 had an immune response to AufA antigen (Fig. 7). The median titer value obtained with sera from the mice infected with wild-type CFT073 was 500. A response to AufA by a single mouse infected with UMD100 was not unexpected, since this mutant has an insertion in the gene for the putative usher protein and could remain able to produce intracellular AufA. The significantly higher prevalence (P = 0.027) of responses by mice infected with the wild-type strains indicates that AufA is expressed by UPEC during the course of UTI.

FIG. 7.

AufA-specific serum IgG responses in CFT073-infected mice. Mice were challenged with 109 CFU of wild-type strain CFT073 and rechallenged on days 16 and 32. For the ELISA, recombinant His-AufA was the antigen, pooled preimmune and individual postimmune sera were used as primary antibodies, and an antimouse IgG-HRP conjugate was used as a secondary antibody as described in Materials and Methods. The mean end point titers are shown as the reciprocal of the dilution for the last positive well for each mouse serum analyzed. The asterisks indicate an immune response fourfold higher than preimmune.

Assessment of the role of Auf in the colonization of the mouse urinary tract by UPEC CFT073.

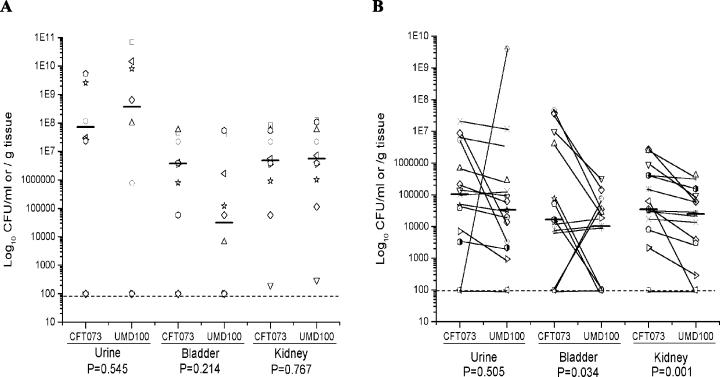

To assess the role of Auf in CFT073 colonization of the mouse urinary tract, wild-type and aufC mutant stains were compared for their ability to colonize the kidneys, bladder, and urine of mice. A suspension of 108 CFU of the wild-type or mutant strain was transurethrally inoculated into the bladders of mice. Mice were sacrificed after 2 days of infection, and the bladders and kidneys were removed and used to determine the number of CFU per gram of tissue for each strain. Prior to sacrifice, urine samples were collected from mice and used to quantify the number of CFU per milliliter of urine. When administered alone, aufC mutant strain UMD100 was able to colonize the mouse urinary tract at a level comparable to the level of colonization by wild-type strain CFT073 (Fig. 8A).

FIG. 8.

Assessment of the virulence of an aufC mutant in the CBA mouse model of ascending UTIs. (A) Independent challenge experiment. Ten mice were transurethrally challenged with 108 CFU of the wild-type strain CFT073 or the aufC mutant UMD100. (B) Cochallenge experiment. Fifteen mice were transurethrally challenged with a 1:1 mixture of CFT073 and UMD100. After 2 days, the mice were sacrificed and the quantitative bacterial counts in the urine, bladders, and kidneys were calculated (see Materials and Methods). Each unique symbol connected by a diagonal line represents the CFU per milliliter of urine or CFU per gram of tissue from an individual mouse. Horizontal bars represent the median of the colony counts. The lower limit of detection (102) in this assay is indicated by a dashed line. P values are indicated at the bottom.

As a more sensitive test of the role of Auf in colonization of the mouse urinary tract, we performed competition colonization experiments in which the wild type and mutant strain UMD100 were administered together in a 1:1 ratio to individual mice. Bacteria were recovered from urine, bladder, and kidneys after 48 h, and CFU were enumerated on selective medium. In these experiments, mutant UMD100 was significantly less competitive than the wild type in the ability to colonize the mouse urinary tract (Fig. 8B).

Studies have shown that in the absence of the usher, periplasmic chaperone-pilus subunit complexes accumulate in the periplasm (22). The accumulation and aggregation of denatured and misfolded proteins in the membranes and periplasm cause extracytoplasmic stress in bacteria. Therefore, we could not exclude the possibility that the diminished ability of UMD100 to compete with CFT073 in the mouse urinary tract could be due to extracytoplasmic stress. To address this concern, mutant UMD133, which contains a deletion of the entire auf gene cluster, was constructed as described in Materials and Methods and tested in competition colonization experiments. The mutant strain UMD133 was recovered at significantly higher levels than wild-type strain CFT073 in the bladder (P = 0.006). Levels of colonization of the kidney and urine by mutant UMD133 tended to be lower than those of colonization by wild-type strain CFT073; however significance at a level of ≤0.05 was not achieved (P = 0.330 and 0.686, respectively). Overall, mutant strain UMD133 was able to colonize the mouse urinary tract as well as wild-type strain CFT073. Figure 9 shows the distribution data for each animal at each site tested. Taken together, the results of the mouse challenge experiments do not support a significant contribution of Auf in CFT073 colonization of the murine urinary tract.

FIG. 9.

Cochallenge of wild-type CFT073 and auf gene cluster deletion mutant UMD133 in the CBA mouse model of ascending UTI. Mice were transurethrally challenged with 108 CFU containing a 1:1 mixture of wild-type strain CFT073 and mutant strain UMD133. After 2 days, the mice were sacrificed and the quantitative bacterial counts in the urine, bladders, and kidneys were calculated (see Materials and Methods). Each unique symbol connected by a diagonal line represents the CFU per milliliter of urine or CFU per gram of tissue from an individual mouse. Horizontal bars represent the median of the colony counts. The lower limit of detection (102) in this assay is indicated by a dashed line. P values are indicated at the bottom.

Histological analysis of mouse kidney and bladder tissue following infection with E. coli CFT073 and UMD100.

To determine the degree of pathological changes associated with infection, bladder and kidney sections from mice infected with either wild-type CFT073 or the aufC mutant UMD100 were examined for histopathological changes. No significant difference in histology scores between mutant and wild-type infection were found (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we describe the identification of a novel chromosomal fimbrial gene cluster in UPEC strain CFT073 termed auf. An examination of the distribution of the auf gene cluster among other pathogenic E. coli strains and enteric pathogens revealed that auf is specifically found in uropathogenic E. coli. Thus, Auf represents another UTI-associated fimbrial operon and joins the list of potential UTI virulence factors.

The DNA sequences of the seven ORFs comprising the auf gene cluster and their predicted amino acid sequences display similarities to members of various chaperone-usher fimbrial operons. A distinctive future of the auf gene cluster is the presence of dual chaperone proteins. The CS5 pili from human enterotoxigenic E. coli (ETEC) and the 987P pili from porcine ETEC are other fimbrial systems that have dual chaperones. In the biogenesis of CS5 and 987P pili, one chaperone appears to be responsible for stabilizing and delivering the major subunit protein and the other is specifically responsible for stabilizing and delivering minor subunits to the outer membrane (11, 12). We have not yet directly demonstrated the roles of Auf chaperones but suggest that they may function in similar ways. The auf gene cluster is a genomic insertion in E. coli CFTO73 compared to the respective region between the glycogen phosphorylase and sn-glycerol 3-phosphate dehydrogenase genes. Although no mobile genetic elements were found surrounding the auf region, two features suggest that CFT073 may have acquired the auf operon by horizontal gene transfer. First, the auf gene cluster is not uniformly present throughout the species, as only 46% of E. coli strains of diverse origins tested positive for aufC by hybridization studies. Second, the average G+C content of the auf gene cluster is much lower than that of E. coli as a whole.

It was not possible to detect AufA protein by immunoblot analysis of wild-type CFT073 under standard laboratory conditions by using an antiserum raised against recombinant AufA. However, we were able to detect transcription of the aufA gene in CFT073 during the exponential growth phase under the same conditions as well as in bacteria recovered from the urine of mice, indicating that the aufA gene is transcribed during infection of the mouse urinary tract. Expression of AufA protein itself was assessed by infecting mice with wild-type CFT073 and analyzing the sera for antibodies reactive to recombinant AufA. Sera from mice infected with wild-type CFT073 contained antibodies recognizing recombinant AufA, thus confirming that AufA protein is expressed in vivo and is most likely surface exposed by CFT073 during infection. We therefore conclude that AufA protein may only be expressed at detectable levels under conditions not mimicked in the laboratory and that apparently include those encountered in vivo.

To study the structure encoded by the auf gene cluster, the auf gene cluster was subcloned under the T7 promoter and expressed in BL21-AI cells. We demonstrated that the Auf protein migrated with apparent molecular masses of 27 and 24 kDa, representing the prepilin and pilin forms, respectively, and heat extraction of surface proteins from BL21-AI cells indicated that mature AufA is surface exposed. Immunogold labeling revealed that the AufA protein adopts an amorphous structure on the surface of BL21-AI cells rather than being assembled as linear fimbriae, indicating that the auf gene cluster is sufficient for production and export of this surface structure. However, we do not know whether all the auf genes or other genes located elsewhere on the chromosome are necessary for Auf biogenesis. This morphology of recombinant Auf fimbriae resembles that of nonfimbrial adhesins assembled via the FGL chaperone-usher pathway (21). The FGL subfamily of periplasmic chaperones are characterized by the possession of two conserved cysteine residues and a variable long sequence between the F1 and G1 β-strands (21, 45). All members of the FGL subfamily are involved in the assembly of surface structures composed of only one or two different subunits polymerized either into very thin flexible fibers that form bundles or aggregates or into surface polymers that have no clearly identifiable structure (21, 45). Examples of the former include the Myf fibrillae of Yersinia enterocolitica and the aggregative adherence fimbriae of enteroaggregative E. coli (23, 33). Examples of the latter are the CS31A of enterotoxigenic and septicemic E. coli and the F1 capsular antigen of Yersinia pestis (10, 21). In contrast, FGS chaperones, which have a relatively short F1-G1 loop with three hydrophobic residues in the G1 β-strands, are used for the assembly of rigid pili composed of up to six different subunits, such as the Pap and type 1 fimbriae (45). Chaperones of the auf gene cluster lack the conserved cysteine residues and have a shorter F1-G1 loop and therefore can be classified as members of the FGS chaperone subfamily. Thus, Auf seems to be exceptional in that it belongs to the FGS family but does not have rigid fimbrial morphology. Because we were unable to directly visualize the production of Auf in CFT073, we cannot rule out the possibility that the native auf operon may direct production of a rigid fimbrial structure under conditions not examined.

Many fimbriae mediate adherence of bacteria to host cells. Expression of the auf gene cluster in BL21-AI cells did not increase the in vitro adherence to HEp-2 laryngeal carcinoma or T24 bladder cells nor mediate hemagglutination of erythrocytes from various species. RT-PCR analysis indicated that BL2-AI cells harboring the auf gene cluster contained an aufG transcript, indicating that the putative adhesin is transcribed and most likely expressed (data not shown). Thus, we have no evidence that recombinant Auf serves as an adhesin. Similarly, the F1 capsule antigen does not mediate the binding of Y. pestis to macrophages but rather serves an antiadhesive and antiphagocytic function (10).

To assess the role of Auf fimbriae in CFT073 colonization of the urinary tract, we insertionally inactivated the aufC usher gene and compared its virulence with that of wild-type strain CFT073 in the murine model of ascending UTI. In single-infection assays, quantitative cultures of urine, bladder, and kidney revealed that the aufC mutant strain UMD100 colonized the mouse urinary tract as well as wild-type strain CFT073. In addition, no quantitative differences in renal pathology were noted between mutant UMD100 and wild-type CFT073, indicating that mutant UMD100 retained the ability to cause pyelonephritis. In competitive colonization experiments, the aufC mutant strain was outcompeted by the wild-type strain in the kidneys and bladders, suggesting that Auf may have a role in colonization. To verify the competition colonization results obtained with the aufC mutant strain and the wild-type strain, additional cochallenge experiments were performed with mutant UMD133, which contains a deletion of the entire auf fimbrial gene cluster. Unlike the aufC mutant strain, mutant UMD133 was able to compete with wild-type strain CFT073 in cochallenge experiments. Thus, despite its association with UPEC strains, we were unable to assign a definite role for Auf in UTI pathogenesis. These studies indicate that the poor ability of aufC insertion mutant UMD100 to compete in the mouse urinary tract was not due to its inability to make Auf and highlight the pitfalls of using mutants unable to export pilin to study pathogenesis.

The results of the mouse challenge experiments with the auf mutants are reminiscent of the observations made by Mobley et al. (31) with respect to P fimbriae of CFT073. These authors were unable to detect a difference in the ability of wild-type strain CFT073 and a double pap mutant strain to colonize the murine urinary tract in single-infection experiments. These results and the results reported here are consistent with the notion that loss of a single fimbrial operon might have only a moderate effect or no effect on colonization because the lack of a single adhesin can be compensated for by the presence of other adhesins (20).

The recent completion of the CFT073 genome revealed the coding capacity for no less than 12 distinct fimbriae (42). Thus, a simultaneous loss of several fimbrial adhesins would be expected to reduce CFT073 colonization to a greater degree than mutation in individual fimbrial operons. Currently, we are constructing single-deletion mutants of the remaining fimbrial operons as well as mutants with multiple fimbrial deletions to determine their effect and synergistic effect on the ability of CFT073 to colonize the murine urinary tract.

Acknowledgments

We thank Harry Mobley for generously providing the E. coli CFT073 cosmid library, Jean-Philippe Nougayrède and Wensheng Luo for technical assistance and helpful discussions, and Richard Hebel for providing statistical analysis of the mice infection data.

This work was supported by NIH Program Project grant no. 2P01 DK49720 and, in part, by the Department of Veterans Affairs, Baltimore, Md. E.L.B. was supported by the United Negro College Fund/Merck Postdoctoral Fellowship, and F.B.-M. was supported by Fellowship Training Program in Vaccinology grant no. T32 AI07524.

Editor: D. L. Burns

REFERENCES

- 1.Abraham, J. M., C. S. Freitag, J. R. Clements, and B. I. Eisenstein. 1985. An invertible element of DNA controls phase variation of type 1 fimbriae of Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 82:5724-5727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andersson, P., I. Engberg, G. Lidin-Janson, K. Lincoln, R. Hull, S. Hull, and C. Svanborg. 1991. Persistence of Escherichia coli bacteriuria is not determined by bacterial adherence. Infect. Immun. 59:2915-2921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bahrani-Mougeot, F. K., E. L. Buckles, C. V. Lockatell, J. R. Hebel, D. E. Johnson, C. M. Tang, and M. S. Donnenberg. 2002. Type-1 fimbriae and extracellular polysaccharides are preeminent uropathogenic Escherichia coli virulence determinants in the murine urinary tract. Mol. Microbiol. 45:1079-1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bahrani-Mougeot, F. K., N. W. Gunther IV, M. S. Donnenberg, and H. L. T. Mobley. 2002. Uropathogenic Escherichia coli, p. 239-268. In M. S. Donnenberg (ed.), Escherichia coli: virulence mechanisms of a versatile pathogen. Academic Press, San Diego, Calif.

- 5.Bahrani-Mougeot, F. K., S. Pancholi, M. Daoust, and M. S. Donnenberg. 2001. Identification of putative urovirulence genes by subtractive cloning. J. Infect. Dis. 183(Suppl. 1):S21-S23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bock, K., M. E. Breimer, A. Brignole, G. C. Hannsson, K. A. Karlsson, G. Larson, H. Leffler, B. E. Samuelsson, N. Stromberg, C. Svanborg Eden, and J. Thurin. 1985. Specificity of binding of a strain of uropathogenic Escherichia coli to Galα1-4Gal-containing glycosphingolipids. J. Biol. Chem. 260:8545-8551. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Connell, H., W. Agace, P. Klemm, M. Schembri, S. Mårild, and C. Svanborg. 1996. Type 1 fimbrial expression enhances Escherichia coli virulence for the urinary tract. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:9827-9832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Datsenko, K. A., and B. L. Wanner. 2000. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:6640-6645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Donnenberg, M. S., and R. A. Welch. 1996. Virulence determinants of uropathogenic Escherichia coli, p. 135-174. In H. L. T. Mobley and J. W. Warren (ed.), Urinary tract infections: molecular pathogenesis and clinical management. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 10.Du, Y., R. Rosqvist, and Å. Forsberg. 2002. Role of fraction 1 antigen of Yersinia pestis in inhibition of phagocytosis. Infect. Immun. 70:1453-1460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Duthy, T. G., P. A. Manning, and M. W. Heuzenroeder. 2002. Identification and characterization of assembly proteins of CS5 pili from enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 184:1065-1077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Edwards, R. A., J. Cao, and D. M. Schifferli. 1996. Identification of major and minor chaperone proteins involved in the export of 987P fimbriae. J. Bacteriol. 178:3426-3433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Foxman, B., R. Barlow, H. D'Arcy, B. Gillespie, and J. D. Sobel. 2000. Urinary tract infection: self-reported incidence and associated costs. Ann. Epidemiol. 10:509-515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gunther, N. W., IV, V. Lockatell, D. E. Johnson, and H. L. Mobley. 2001. In vivo dynamics of type 1 fimbria regulation in uropathogenic Escherichia coli during experimental urinary tract infection. Infect. Immun. 69:2838-2846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gunther, N. W., IV, J. A. Snyder, V. Lockatell, I. Blomfield, D. E. Johnson, and H. L. T. Mobley. 2002. Assessment of virulence of uropathogenic Escherichia coli type 1 fimbrial mutants in which the invertible element is phase-locked on or off. Infect. Immun. 70:3344-3354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guyer, D. M., S. Radulovic, F.-E. Jones, and H. L. T. Mobley. 2002. Sat, the secreted autotransporter toxin of uropathogenic Escherichia coli, is a vacuolating cytotoxin for bladder and kidney epithelial cells. Infect. Immun. 70:4539-4546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hensel, M., J. E. Shea, C. Gleeson, M. D. Jones, E. Dalton, and D. W. Holden. 1995. Simultaneous identification of bacterial virulence genes by negative selection. Science 269:400-403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hull, R. A., W. H. Donovan, M. Del Terzo, C. Stewart, M. Rogers, and R. O. Darouiche. 2002. Role of type 1 fimbria- and P fimbria-specific adherence in colonization of the neurogenic human bladder by Escherichia coli. Infect. Immun. 70:6481-6484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hull, R. A., D. C. Rudy, W. H. Donovan, I. E. Wieser, C. Stewart, and R. O. Darouiche. 1999. Virulence properties of Escherichia coli 83972, a prototype strain associated with asymptomatic bacteriuria. Infect. Immun. 67:429-432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Humphries, A. D., S. M. Townsend, R. A. Kingsley, T. L. Nicholson, R. M. Tsolis, and A. J. Baumler. 2001. Role of fimbriae as antigens and intestinal colonization factors of Salmonella serovars. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 201:121-125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hung, D. L., S. D. Knight, R. M. Woods, J. S. Pinkner, and S. J. Hultgren. 1996. Molecular basis of two subfamilies of immunoglobulin-like chaperones. EMBO J. 15:3792-3805. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hung, D. L., T. L. Raivio, C. H. Jones, T. J. Silhavy, and S. J. Hultgren. 2001. Cpx signaling pathway monitors biogenesis and affects assembly and expression of P pili. EMBO J. 20:1508-1518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Iriarte, M., J. C. Vanooteghem, I. Delor, R. Diaz, S. Knutton, and G. R. Cornelis. 1993. The Myf fibrillae of Yersinia enterocolitica. Mol. Microbiol. 9:507-520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Johnson, D. E., C. V. Lockatell, R. G. Russell, J. R. Hebel, M. D. Island, A. Stapleton, W. E. Stamm, and J. W. Warren. 1998. Comparison of Escherichia coli strains recovered from human cystitis and pyelonephritis infections in transurethrally challenged mice. Infect. Immun. 66:3059-3065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khan, A. S., and D. M. Schifferli. 1994. A minor 987P protein different from the structural fimbrial subunit is the adhesin. Infect. Immun. 62:4233-4243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Klapproth, J.-M., I. C. A. Scaletsky, B. P. McNamara, L.-C. Lai, C. Malstrom, S. P. James, and M. S. Donnenberg. 2000. A large toxin from pathogenic Escherichia coli strains that inhibits lymphocyte activation. Infect. Immun. 68:2148-2155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lim, J. K., N. W. Gunther IV, H. Zhao, D. E. Johnson, S. K. Keay, and H. L. T. Mobley. 1998. In vivo phase variation of Escherichia coli type 1 fimbrial genes in women with urinary tract infection. Infect. Immun. 66:3303-3310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lindberg, U., L. Å. Hanson, U. Jodal, G. Lidin-Janson, K. Lincoln, and S. Olling. 1975. Asymptomatic bacteriuria in schoolgirls. II. Differences in Escherichia coli causing asymptomatic bacteriuria. Acta Paediatr. Scand. 64:432-436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miller, V. L., and J. J. Mekalanos. 1988. A novel suicide vector and its use in construction of insertion mutations: osmoregulation of outer membrane proteins and virulence determinants in Vibrio cholerae requires toxR. J. Bacteriol. 170:2575-2583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mobley, H. L. T., D. M. Green, A. L. Trifillis, D. E. Johnson, G. R. Chippendale, C. V. Lockatell, B. D. Jones, and J. W. Warren. 1990. Pyelonephritogenic Escherichia coli and killing of cultured human renal proximal tubular epithelial cells: role of hemolysin in some strains. Infect. Immun. 58:1281-1289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mobley, H. L. T., K. G. Jarvis, J. P. Elwood, D. I. Whittle, C. V. Lockatell, R. G. Russell, D. E. Johnson, M. S. Donnenberg, and J. W. Warren. 1993. Isogenic P-fimbrial deletion mutants of pyelonephritogenic Escherichia coli: the role of αGal(1-4)βGal binding in virulence of a wild-type strain. Mol. Microbiol. 10:143-155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nagy, G., U. Dobrindt, G. Schneider, A. S. Khan, J. Hacker, and L. Emody. 2002. Loss of regulatory protein RfaH attenuates virulence of uropathogenic Escherichia coli. Infect. Immun. 70:4406-4413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nataro, J. P., and T. Steiner. 2002. Enteroaggregative and diffusely adherent Escherichia coli, p. 189-207. In M. S. Donnenberg (ed.), Escherichia coli: virulence mechanisms of a versatile pathogen. Academic Press, San Diego, Calif.

- 34.Pósfai, G., M. D. Koob, H. A. Kirkpatrick, and F. R. Blattner. 1997. Versatile insertion plasmids for targeted genome manipulations in bacteria: isolation, deletion, and rescue of the pathogenicity island LEE of the Escherichia coli O157:H7 genome. J. Bacteriol. 179:4426-4428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rippere-Lampe, K. E., A. D. O'Brien, R. Conran, and H. A. Lockman. 2001. Mutation of the gene encoding cytotoxic necrotizing factor type 1 (cnf1) attenuates the virulence of uropathogenic Escherichia coli. Infect. Immun. 69:3954-3964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Roberts, J. A., B.-I. Marklund, D. Ilver, D. Haslam, M. B. Kaack, G. Baskin, M. Louis, R. Möllby, J. Winberg, and S. Normark. 1994. The Gal(α1-4)Gal-specific tip adhesin of Escherichia coli P-fimbriae is needed for pyelonephritis to occur in the normal urinary tract. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91:11889-11893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 38.Stapleton, A., S. Moseley, and W. E. Stamm. 1991. Urovirulence determinants in Escherichia-coli isolates causing first-episode and recurrent cystitis in women. J. Infect. Dis. 163:773-779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Struve, C., and K. A. Krogfelt. 1999. In vivo detection of Escherichia coli type 1 fimbrial expression and phase variation during experimental urinary tract infection. Microbiology 145:2683-2690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Torres, A. G., P. Redford, R. A. Welch, and S. M. Payne. 2001. TonB-dependent systems of uropathogenic Escherichia coli: aerobactin and heme transport and TonB are required for virulence in the mouse. Infect. Immun. 69:6179-6185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wei, Y., J.-M. Lee, C. Richmond, F. R. Blattner, J. A. Rafalski, and R. A. LaRossa. 2001. High-density microarray-mediated gene expression profiling of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 183:545-556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Welch, R. A., V. Burland, G. Plunkett III, P. Redford, P. Roesch, D. Rasko, E. L. Buckles, S. R. Liou, A. Boutin, J. Hackett, D. Stroud, G. F. Mayhew, D. J. Rose, S. Zhou, D. C. Schwartz, N. T. Perna, H. L. Mobley, M. S. Donnenberg, and F. R. Blattner. 2002. Extensive mosaic structure revealed by the complete genome sequence of uropathogenic Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:17020-17024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Woodall, L. D., P. W. Russell, S. L. Harris, and P. E. Orndorff. 1993. Rapid, synchronous, and stable induction of type 1 piliation in Escherichia coli by using a chromosomal lacUV5 promoter. J. Bacteriol. 175:2770-2778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wullt, B., G. Bergsten, H. Connell, P. Rollano, N. Gebretsadik, R. Hull, and C. Svanborg. 2000. P fimbriae enhance the early establishment of Escherichia coli in the human urinary tract. Mol. Microbiol. 38:456-464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zavialov, A. V., J. Berglund, A. F. Pudney, L. J. Fooks, T. M. Ibrahim, S. MacIntyre, and S. D. Knight. 2003. Structure and biogenesis of the capsular F1 antigen from Yersinia pestis: preserved folding energy drives fiber formation. Cell 113:587-596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang, L., B. Foxman, S. D. Manning, P. Tallman, and C. F. Marrs. 2000. Molecular epidemiologic approaches to urinary tract infection gene discovery in uropathogenic Escherichia coli. Infect. Immun. 68:2009-2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]