Abstract

We have isolated from calf serum a protein with an apparent Mr of 120,000. The protein was detected by using antibodies against major acute-phase protein in pigs with acute inflammation. The amino acid sequence of an internal fragment revealed that this protein is the bovine counterpart of ITIH4, the heavy chain 4 of the inter-alpha-trypsin inhibitor family. The response of this protein in the sera was determined for animals during experimental bacterial and viral infections. In the bacterial model, animals were inoculated with a mixture of Actinomyces pyogenes, Fusobacterium necrophorum, and Peptostreptococcus indolicus to induce an acute-phase reaction. All animals developed moderate to severe clinical mastitis and exhibited remarkable increases in ITIH4 concentration in serum (from 3 to 12 times the initial values, peaking at 48 to 72 h after infection) that correlated with the severity of the disease. Animals with experimental infections with bovine respiratory syncytial virus (BRSV) also showed increases in ITIH4 concentration (from two- to fivefold), which peaked at around 7 to 8 days after inoculation. Generally, no response was seen after a second infection of the same animals with the virus. Because of the significant induction of the protein in the animals in the mastitis and BRSV infection models, we can conclude that ITIH4 is a new positive acute-phase protein in cattle.

The acute-phase response occurs in animals as a consequence of infection, inflammation, or trauma. It is a nonspecific response mediated by inflammation-related cytokines (mainly by interleukin-6 [IL-6], IL-1, and tumor necrosis factor alpha) and is characterized by several systemic reactions, including fever, catabolism of muscle protein, alterations in sleep and appetite patterns, and changes in the concentrations of a group of serum proteins called acute-phase proteins (APP) (3, 22, 27, 40).

APP have been studied extensively in humans and in many animal species, mostly rats (38), though the panel of these proteins is probably not complete. The APP response differs among species. For domestic animals, the studies on APP are relatively recent (reviewed in reference 18). For cattle, several APP, including serum amyloid A, haptoglobin, alpha-1-acid glycoprotein, and alpha-1-proteinase inhibitor (alpha-1-antitrypsin), have been shown to increase in different inflammatory processes, in both in vivo (9, 14, 18, 20, 23, 25, 32) and in vitro models (2, 31). The course of infection in human patients is monitored by the determination of APP in blood samples (43), and a similar clinical use has been proposed for veterinary medicine (15, 18, 26) as well as for monitoring the health status of animals during farm production and at slaughter (42).

In previous works from our laboratory, a new 120-kDa plasma glycoprotein, designated major acute-phase protein or pig MAP, was described as an APP occurring in pigs with turpentine-induced inflammation (16, 29). This protein, which is also called porcine inter-alpha-trypsin inhibitor human-related protein (pig IHRP) (19), is the porcine counterpart of human plasma kallikrein-sensitive protein (PK-120; also called human IHRP) (33, 35). The amino acid sequences obtained from the pig, human, and rat proteins show significant homology for over two-thirds of the amino-terminal sequences with the heavy chains (H1, H2, and H3) of the inter-alpha-trypsin inhibitor (ITI) protein family (19, 33, 35, 36, 39). Pig MAP or pig IHRP, PK-120 or human IHRP, and the homologous rat protein have been designated ITIH4, a new member of the heavy-chain ITI family (36). However, the homology with the other H chains is low for one-third of the carboxy-terminal sequence of the polypeptide chain (33, 35, 36). The heavy chains H1, H2, and H3 are bound through glycosaminoglycan bridges to bikunin (which contains two Kunitz-type protease inhibitor domains), but H4 lacks the signal sequence for bikunin assembling (reviewed in references 5 and 36).

It has been reported that ITIH4 expression is induced under different pathological situations in vivo and in vitro in pigs (1, 16, 17, 21, 29), in rats (12, 16, 39), and in humans (34). Nothing is known at the moment about the behavior of ITIH4 in bovines.

The purpose of the present work was the isolation and characterization of the response of the plasma protein ITIH4 in bovines. The acute-phase response of the protein was studied in experimental infection models in adult and young cattle: cows with induced summer mastitis (23, 24) and calves inoculated with the common pathogen bovine respiratory syncytial virus (BRSV) (41).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Experimental models and sample collection. (i) Summer mastitis model.

Ten pregnant heifers (eight Ayrshires and two Friesians) due to calve in 1 or 2 months were experimentally infected as previously described (23). Briefly, two hindquarters of each heifer were inoculated with a suspension prepared by combining 1 ml of each of the following bacterial strains (9 × 108 CFU/ml) recently isolated from field cases of summer mastitis (24): Actinomyces pyogenes AHP 13199, Fusobacterium necrophorum AHN 8155, and Peptostreptococcus indolicus AHC 5732.

Blood samples from the jugular veins were taken before bacterial inoculation and at 8, 18, 24, and 32 h and 2, 3, 5, 7, and 14 days after inoculation. Serum was separated by centrifugation at 1,000 × g for 10 min and stored at −70°C until the analyses were performed.

The development of mastitis was monitored by the assessment of systemic and local clinical signs and by bacteriological examination of udder secretion samples. Several clinical parameters, including body temperature and udder swelling, were also monitored (23). Antibiotic treatment of the heifers started 32 h after bacterial challenge and lasted for 3 days (23, 24). The acute-phase response of the heifers was investigated using conventional APP, and the results were published earlier (23).

(ii) BRSV model.

Six 13- to 21-week-old male Jersey calves from two herds, all testing negative for infection with bovine diarrhea virus, were challenged with a BRSV inoculum consisting of a third or fourth passage of BRSV strain 2022 in fetal bovine lung cell culture, as previously described (41). The original BRSV material, from lung lavage fluid from a 1-month-old field calf with severe BRSV-related pneumonia, was passaged once in a 1-month-old colostrum-deprived calf before inoculation into fetal bovine lung cells. The calves were inoculated once by combined aerosol exposure (5 ml in phosphate-buffered saline administered for 10 min through a mask covering the animals' nostrils and mouth) and intratracheal injection (20 ml in phosphate-buffered saline). The inoculum was 104.6 to 105.2 50% tissue culture infective doses of BRSV for each type of inoculation. Four of the calves (calves 1023, 1026, 1888, and 1892) were inoculated on day 0 and reinoculated 14 weeks later (on day 98), while calves 1025 and 1895 were inoculated only on day 98. Clinical signs (rectal temperature and respiratory rate) were monitored daily. Blood samples were obtained regularly after infection by jugular venipuncture (Veno-ject tubes). After the blood was allowed to clot at 4°C, the sera were extracted and stored at −20°C. Calves were anesthetized on day 112 (14 days after the second infection of the reinfected animals) with pentobarbital (50 mg/kg of body weight) and euthanized by exsanguination. The lungs were examined for the presence of BRSV and other viruses and bacteria as previously described (41).

The experiments were approved by the animal experimentation committees or ethics committees in each institute and were compliant with all relevant European Union guidelines on animal experimentation.

Purification of ITIH4.

As starting material, 50 ml of pooled calf serum (from the local slaughterhouse) was used, and 0.1% NaN3 and the following protease inhibitors were added: 6 mM EDTA, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 3 mg of Polybrene (hexadimethrine bromide)/ml, and 10 mM lysine-HCl. Bovine serum was dialyzed against 0.05 M Tris-HCl-0.02 M NaCl (pH 7.5) buffer (Tris buffer) and applied to a 10- by 3-cm DEAE-Sephadex A-50 column (Pharmacia LKB, Madrid, Spain) equilibrated in the same buffer. Proteins were eluted with a saline linear gradient containing NaCl (up to 0.5 M) in Tris buffer (total volume, 600 ml). After Western blot analysis, fractions enriched in ITIH4 were selected by using antisera against pig MAP (16) that recognize the homologous bovine protein. The fractions were then dialyzed against the Tris buffer and applied to a 10- by 2-cm column of Sepharose 4B (Pharmacia)-immobilized Cibacron blue equilibrated in the same buffer. A fraction that contained ITIH4 with albumin as the major contaminant was eluted with Tris buffer containing 0.5 M NaCl. Finally, this fraction was dialyzed against 0.15 M NaCl-0.01 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) containing 0.1% NaN3 and concentrated by ultrafiltration (PM-10000 membranes; Amicon, Madrid, Spain), and chromatography was performed with a 100- by 2-cm Sephadex G-150 column (Pharmacia) equilibrated in this phosphate buffer. The concentration of the isolated protein was determined as described by Lowry (30). Samples were aliquoted and stored at −20°C.

Antiserum against ITIH4.

Antiserum against ITIH4 was produced in two healthy adult female New Zealand White rabbits (3 to 3.5 kg) by subcutaneous injections of the purified protein, following a previously reported protocol (16, 29).

Electrophoresis and Western blotting.

Protein samples were analyzed by reducing sodium dodecyl sulfate-10% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-10% PAGE) (28). The separated proteins were blotted from the gel onto nitrocellulose membranes (Hybond-C super; Amersham, Madrid, Spain), at 20 V, for 1 h in a semidry transfer cell (TransBLOT SD; Bio-Rad, Madrid, Spain). After blotting, the membranes were incubated first with the specific antisera (1:2,000 dilution) and then with alkaline phosphatase-conjugated sheep anti-rabbit-immunoglobulin G (Sigma, Madrid, Spain) (1/10,000 dilution). The immunocomplexes were visualized with a fresh solution of 0.1 mg of nitroblue tetrazolium chloride (Sigma)/ml and 0.06 mg of 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolylphosphate (Sigma)/ml in 0.2 M Tris-1 mM MgCl2 (pH 9.6) buffer. An SDS-7B protein kit (Sigma) was used for molecular weight markers.

Microsequencing.

As reported for the homologous human and pig proteins (16, 33, 35), purified ITIH4 exhibits spontaneous proteolysis during the purification and storage of the protein at 4°C for extended periods of time. A preparation of purified ITIH4 (100 μg) was electrophoresed in a reducing SDS-10% PAGE gel, blotted onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Immobilon P; Millipore), and then stained with Coomassie brilliant blue R. As a specific control, the same sample was electrophoresed and blotted but visualized by using specific antisera against ITIH4. The zones corresponding to the 120-kDa band and to a fragment of the protein band around 80 kDa in the Coomassie brilliant blue R-stained membrane were cut out and directly subjected to NH2-terminal amino acid sequencing, which was carried out as a commercial service by the Institute of Animal Physiology and Genetics Research (Babraham, Cambridge, United Kingdom).

Determination of ITIH4 in serum samples.

The concentration of ITIH4 in serum was determined by radial immunodiffusion in 1% agarose gels containing the specific rabbit antiserum against the protein. The results were expressed in milligrams per milliliter with respect to the acute-phase bovine serum used as a secondary standard. The concentration of ITIH4 in this serum was previously determined by radial immunodiffusion with purified bovine ITIH4 as the primary reference standard.

Statistical analysis.

Statistical differences between the severely and moderately affected heifers in the mastitis infection model were tested with Student's t tests, using the statistical computer program SPSS. Logarithmic transformation of the data was used to normalize the distribution of values.

RESULTS

Analysis of bovine ITIH4.

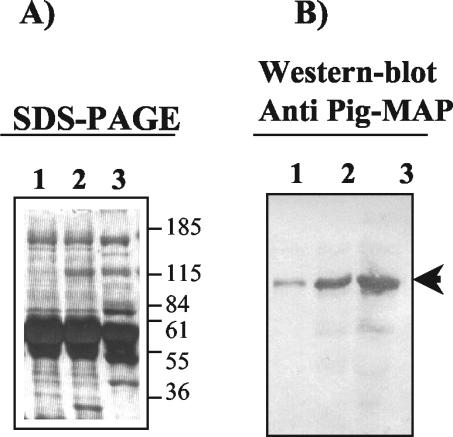

By SDS-PAGE, a band with an Mr of about 120,000 was observed to be significantly increased in sera from animals with experimentally induced mastitis compared to that in sera obtained before infection (Fig. 1A). A band with an Mr of 120,000 was revealed in the bovine sera after Western blotting using specific anti-pig MAP/ITIH4 polyclonal antibodies, indicating the presence of a homologous protein of pig MAP in the bovine sera. The intensity of the band was clearly higher in the sera from cows with mastitis (Fig. 1B).

FIG. 1.

(A) Reducing SDS-10% PAGE gel of bovine sera. Lane 1, 10 μl of pooled sera (dilution, 1:20) from healthy heifers; lane 2, 10 μl of pooled sera (dilution, 1:20) from heifers with experimental mastitis; lane 3, 10 μl of serum (dilution, 1:20) from a pig 48 h after turpentine-induced inflammation. The gel was stained with Coomassie brilliant blue R. Molecular weight markers (in thousands) are indicated on the right side of the gel. (B) Western blot with specific antibodies against pig MAP (ITIH4). Lanes are the same as those for panel A, but sera were diluted 1:30. The arrow indicates the position of pig MAP and the homologous bovine ITIH4 in the blot.

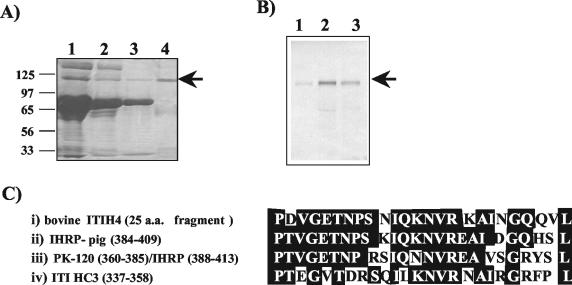

Figure 2A shows the protein patterns in reducing SDS-PAGE gels of samples collected at different steps during the purification of ITIH4 from pooled calf sera. The purified protein shows a major band of around 120 kDa (lane 4) and minor bands of lower masses corresponding to fragments of the protein, since they react with specific antibodies to pig MAP (ITIH4) when analyzed by Western blotting (data not shown). The purified bovine protein was injected into rabbits to prepare specific polyclonal antisera. The antibodies that were produced recognized, by Western blotting, a unique band of p120 in acute-phase bovine serum (Fig. 2B, lane 2), which was detected with less intensity in bovine serum from healthy animals (Fig. 2B, lane 1). These antibodies also recognized the homologous protein in pig serum (Fig. 2B, lane 3).

FIG. 2.

(A) Reducing SDS-10% PAGE gel of samples obtained during bovine ITIH4 purification. Lane 1, 5 μl of the fraction obtained after DEAE-Sephadex A-50 chromatography of the starting pooled calf serum (dilution, 1:5); lanes 2 and 3, unbound and eluted fractions, respectively, from the Sepharose 4B-immobilized Cibacron blue column (5 μl; dilution, 1:5); lane 4, purified bovine ITIH4 fraction obtained after Sephadex G-150 chromatography (15 μl). The arrow indicates the position of the protein. Molecular weight markers (in thousands) are indicated on the left side of the gel. (B) Western blot with specific antibodies against bovine ITIH4 of 10 μl of pooled calf sera (dilution, 1:30) from healthy heifers (lane 1) and from heifers suffering from clinical mastitis (lane 2). Lane 3, 10 μl of serum (dilution, 1:30) from a pig 48 h after turpentine-induced inflammation. (C) Amino acid (a.a.) sequence alignments of (i) the 25-polypeptide fragment of bovine ITIH4, (ii) pig IHRP (19), (iii) human PK-120 (32) or IHRP (33, 35), and (iv) human ITI-HC3 (6). White letters on a black background correspond to residues showing identity with ITIH4 (sequence analysis performed with the FASTA/EIB data bank). Numbers in parentheses are the residue positions in the amino acid sequences of the proteins.

The native protein, a 120-kDa band, did not generate an optimal NH2-terminal amino acid sequence, because the terminal amino acid is blocked. A sequence of 25 amino acids was obtained from an internal fragment spontaneously produced from the purified bovine ITIH4 (Fig. 2C). A search of the FASTA protein database showed high homology with the deduced amino acid sequence of human PK-120 (human IHRP) (33, 35) and pig MAP (pig IHRP) (19). Figure 2C also shows the moderate homology found with the heavy chain H3 of the human ITI family (6).

ITIH4 response in heifers with experimental mastitis.

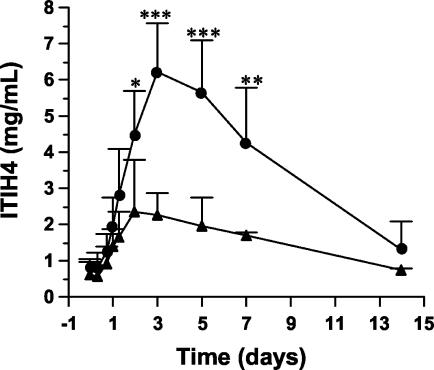

As a result of the infusion of bacteria, all 10 heifers developed clinical signs of moderate to severe mastitis, including fever, increased pulse rate, udder swelling, and changes in the appearance of the udder secretion (23). The body temperatures of nine of the heifers exceeded 40°C 8 h after bacterial inoculation. On the day following inoculation, the body temperature of four heifers returned to normal, while it was still high in the remaining six heifers after 3 days. The local signs were more severe in the six heifers with prolonged fever, which also had depressed rumen motility and poor appetite. These animals suffered from chronic purulent mastitis, whereas the other four animals were completely recovered and started normal milk production after calving (23). Figure 3 shows the time course profile of ITIH4, expressed in milligrams per milliliter. All heifers responded to the challenge with increased ITIH4 concentrations. The six severely infected heifers showed maximum ITIH4 concentrations at 72 h after bacterial injection. The concentration of the protein in serum was 6- to 12-fold higher than before the bacterial challenge. In the four animals with milder clinical mastitis, the protein exhibited only a three- to fourfold increase during the infection process and had reached a plateau by 48 h after the challenge. In both cases, the ITIH4 concentrations decreased to normal values about 2 weeks after the injection. Statistically significant differences in ITIH4 concentration between the groups of severely and moderately infected heifers were observed on days 2 to 7 postinfection (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Time course of ITIH4 concentration in plasma in heifers with experimentally induced mastitis before (day 0) and on the indicated days after bacterial infection. ▴, heifers (n = 4) with moderate outcome of the disease; •, heifers (n = 6) showing acute symptoms; *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001.

ITIH4 responses in animals with experimental infection with BRSV.

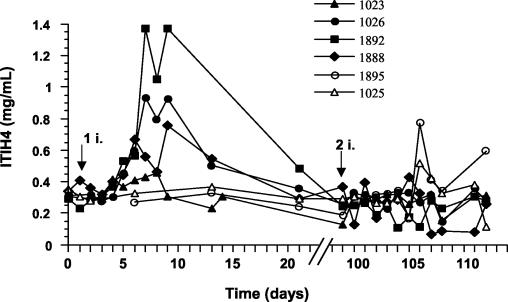

Increases in ITIH4 concentration followed the development of disease in BRSV-inoculated animals. Clinical signs of disease (febrile response and increased respiratory rate) were noticed 4 to 5 days after the inoculation of the virus. A rectal temperature above 40°C and a respiratory rate above 60 respirations/min were observed in three of four infected animals (bovines 1026, 1888, and 1892). The clinical signs in calf 1023 were less pronounced (rectal temperature lower than 39°C and respiratory rate below 60 respirations/min) (S. N. Grell, K. Tjønehøj, L. E. Larsen, and P. M. H. Heegaard, submitted for publication). All animals exhibited increases in ITIH4 concentration, ranging from 1.5 to 4.5 times normal values depending on the degree of infection (Fig. 4). Peak values were observed on days 7 to 9 after infection. During the same period, the concentration of the protein remained around 0.3 mg/ml in noninfected animals (animals 1025 and 1895). Animals 1023, 1026, 1888, and 1892 received a second dose of BRSV 98 days after the first infection, and animals 1025 and 1895 received their first dose at the same time. None of the reinfected animals showed clinical signs of disease. Only animal 1895 had an elevated rectal temperature and a respiratory rate above the baseline. Both calves (animals 1025 and 1895) excreted the virus at low levels (Grell et al., submitted). On day 7 postinoculation, increases in ITIH4 concentration were observed in sera from animals that had had no previous contact with the virus (2.5 times for animal 1895 and 1.5 times for animal 1025).

FIG. 4.

Time course of ITIH4 concentration in plasma in calves, before (day 0) and on indicated days after inoculation with BRSV. Arrows indicate the first and second virus inoculations (i). Animals 1025 and 1895 were inoculated only on day 98.

DISCUSSION

In a previous work, a novel APP, named pig MAP, was detected in pigs with experimentally induced acute inflammation (29). This protein proved to be a new member of the ITI heavy-chain family and is also known as ITIH4. Analysis by Western blotting using anti-pig MAP/ITIH4 antibodies revealed the presence of a homologous protein in the bovine serum. ITIH4 was isolated here from calf serum by a method similar to that previously reported for the purification of the homologous porcine protein. The native protein did not generate an optimal amino acid sequence, probably because the NH2-terminal amino acid was blocked, as previously observed for pig MAP/ITIH4 (unpublished results). The sequence obtained from an internal fragment of bovine ITIH4, which was spontaneously generated during purification and storage of the protein, showed a high homology (more than 85%) with the corresponding region of human or pig ITIH4 (33, 35). A notable susceptibility to proteolysis has also been reported for the homologous human and porcine proteins (16, 19, 33, 35).

The acute-phase response of bovine ITIH4 has been studied in our laboratory in two experimental infection models, with animals with induced summer mastitis (23, 24) and with animals inoculated with the common bovine respiratory pathogen BRSV. The experimental mastitis model used in this work resulted in clinical mastitis in all 10 heifers that were treated. ITIH4 increased in all animals (between 3- and 12-fold), and the time course of the response was similar to that found for haptoglobin in this experimental model (23), although the response was more protracted. The clinical symptoms divided the heifers into two groups: six animals became severely infected, and the other four animals became moderately infected. Statistically significant differences in rectal temperature (between 18 and 32 h postinfection; P < 0.01 to 0.001) and udder swelling (between 18 and 120 h postinfection; P < 0.05 to 0.001) were found between the two groups (23). The division into six severely and four moderately infected animals by clinical findings was further confirmed by the ITIH4 profile. The severity of the disease correlated positively with ITIH4 levels, and ITIH4 was also an indicator to predict recovery from the disease, as observed with the four heifers that recovered early from the mastitis infection and were healthy after calving. During days 2 to 7 postinfection, the concentration of ITIH4 in this group was 2 to 3 times lower than in the group of severely infected animals (P < 0.05 to 0.001). This result was consistent with the results previously found for haptoglobin in this experimental model. The haptoglobin responses were intense in the group of animals that exhibited fever and severe clinical symptoms and moderate in the group of animals with a better course of the disease. Additional parameters such as white blood cell counts had no predictive value for the severity of disease (23). Other authors have also found haptoglobin and serum amyloid A to be useful prognostic indicators in diseased cattle (10, 13, 14, 15, 20). Proteins such as fibrinogen, alpha-1-antitrypsin, and acid-soluble glycoproteins responded moderately in this and other infection models (8, 10, 23).

Viral infections generally lead to weak acute-phase reactions (44), a fact that has been used in human clinical medicine to discriminate between viral and bacterial infections, e.g., in respiratory infections (43). In BRSV-inoculated animals, the maximum concentration of ITIH4 (ranging from 1.5 to 4.5 times the normal values) was observed at days 7 to 9 after infection. Based on clinical signs (respiratory rate and body temperature) and the haptoglobin acute-phase response, calves 1026 and 1892 were the most severely infected, followed by calves 1888 and 1023 (Grell et al., submitted). In the second infection, none of the four reinfected animals showed any clinical signs or haptoglobin response, while the two calves being infected for the first time (calves 1025 and 1895) showed a high (calf 1895) and a moderate (calf 1025) haptoglobin response. Only calf 1895 showed any clinical signs, corresponding well with the fact that this calf was the only of the two calves showing pathological changes in the lung (Grell et al., submitted). Regarding ITIH4, the response of the protein most closely resembled that of haptoglobin and the clinical data. In the case of haptoglobin, the increases in concentration in BRSV-infected calves were, in general, comparable to those previously reported for bacterial models (20). However, the magnitude of the ITIH4 response was moderate when compared to that observed in animals experimentally infected with mastitis. This behavior of ITIH4 in BRSV infection is in agreement with previous results with ITIH4 in pigs experimentally infected with the Aujeszky virus (1). In this model, the concentration of the porcine ITIH4 was between 2 and 5 times higher than that in noninfected animals, whereas larger increases (12- to 15-fold) were reported for pigs with bacterial infections (21). Postmortem inspection (at day 14 after the second infection) revealed no bacteria and no mycoplasmas except for animal 1895, which had Mycoplasma dispar (data not shown). However, this agent was previously found not to be associated with acute-phase responses of haptoglobin and serum amyloid A protein (20).

Differences in ITIH4 concentration before pathogen infection were observed between the animals of the two experimental models used here. In the case of the homologous porcine protein, higher levels of ITIH4 have been observed in weaning pigs and in sows at parturition than in healthy pigs from a farm cited as a “model farm” after veterinary monitoring (1). More studies are necessary to determine the dependence of the basal levels of bovine ITIH4 on factors such as age, gender, or genetic background.

In view of the significant inductions of ITIH4 in the infected animals, we can conclude that ITIH4 is a new APP in the bovine. The members of the ITI family are differently regulated during the acute-phase response: the H2 and bikunin chains are down-regulated, whereas the H3 chain is an up-regulated APP in human patients with acute inflammation and in human HepB3 hepatocarcinoma cells after IL-6 treatment (11). Increased expression of the mRNA for H1 and H3, together with a simultaneous decrease in the H2 messenger, was also observed after IL-6 stimulation of HepG2 cells (37). Similar observations, of up-regulation of H3 mRNA and down-regulation of bikunin and H2 mRNA hepatic expression, were found in rats during turpentine-induced inflammation (12). In rats, H4 mRNA (12, 39) and the secreted protein (16) are also up-regulated in the liver during acute inflammation. The expression levels of human and pig H4 mRNA and the secreted proteins are highly up-regulated by IL-6 in HepG2 hepatoma cells and in isolated porcine hepatocytes (17, 34).

Several functions for different APP have been described previously (43). The biological function of ITIH4 is still unknown. A possible role of the protein related to modulation of cell migration and proliferation during the development of the acute-phase response has been discussed. Thus, interaction of ITI members with components of the extracellular matrix has been described (5). Inhibition of actin polymerization and phagocytosis has also been reported as a consequence of the action of the protein in polymorphonuclear cells (7). Additional functions involving roles in liver development and regeneration have recently been reported for ITIH4 (4). The facts that kallikrein acting upon PK-120 may release peptides with kinin activity (33) and that ITIH4 is an APP in different species open a new gate to the study of the complex process of inflammation and infection.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by research grant PM95-0081 from the Spanish Ministerio de Educación y Cultura. S.C. holds a collaboration fellowship from the Spanish Education Ministry.

We thank Nieves González-Ramón and Javier Salamero for their contributions to this work.

Editor: S. H. E. Kaufmann

REFERENCES

- 1.Alava, M. A., N. González-Ramón, P. Heegaard, S. Guzylack, M. J. M. Toussaint, C. Lipperheide, F. Madec, E. Gruys, P. D. Eckersall, F. Lampreave, and A. Piñeiro. 1997. Pig-MAP, porcine acute phase proteins and standardisation of assays in Europe. Comp. Haematol. Int. 7:208-213. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alsemgeest, S. P. M., G. A. van't Klooster, A. S. van Miert, C. K. Hulskamp-Koch, and E. Gruys. 1996. Primary bovine hepatocytes in the study of cytokine induced acute-phase protein secretion in vitro. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 53:179-184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baumann, H., and J. Gauldie. 1994. The acute phase response. Immunol. Today 15:74-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bhanumathy, C. D., Y. Tang, S. P. S. Monga, V. Katuri, J. A. Cox, B. Mishra, and L. Mishra. 2002. Itih-4, a serine protease inhibitor regulated in interleukin-6-dependent liver formation: role in liver development and regeneration. Dev. Dyn. 223:59-69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bost, F., M. Diarra-Mehrphour, and J. P. Martin. 1998. Inter-alpha-trypsin inhibitor proteoglycan family. A group of proteins binding and stabilizing the extracellular matrix. Eur. J. Biochem. 252:339-346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bourguignon, J., M. Diarra-Mehrpour, L. Thiberville, F. Bost, R. Sesboue, and J.-P. Martin. 1993. Human pre-α-trypsin inhibitor-precursor heavy chain cDNA and deduced amino acid sequence. Eur. J. Biochem. 212:771-776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Choi-Miura, N. H., K. Takahashi, M. Yoda, K. Saito, M. Hori, H. Ozaki, T. Mazda, and M. Tomita. 2000. The novel acute phase protein, IHRP, inhibits actin polymerization and phagocytosis of polymorphonuclear cells. Inflamm. Res. 49:305-310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Conner, J. G., P. D. Eckersall, M. Doherty, M., and T. A. Douglas. 1986. Acute phase response and mastitis in the cow. Res. Vet. Sci. 41:126-128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Conner, J. G., P. D. Eckersall, A. Wiseman, T. C. Aitchison, and T. A. Douglas. 1988. Bovine acute phase response following turpentine injection. Res. Vet. Sci. 44:82-88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Conner, J. G., P. D. Eckersall, A. Wiseman, R. K. Bain, and T. A. Douglas. 1989. Acute phase response in calves following infection with Pasteurella haemolytica, Ostertagia ostertagi and endotoxin administration. Res. Vet. Sci. 47:203-207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Daveau, M., P. Rouet, M. Scotte, L. Faye, M. Hiron, J. P. Lebreton, and J. P. Salier. 1993. Human inter-alpha-inhibitory family in inflammation: simultaneous synthesis of positive and negative acute-phase proteins. Biochem. J. 292:485-492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Daveau, M. J., E. Soury, E. Olivier, S. Masson, S. Lyoumi, P. Chan, M. Hiron, J. P. Lebreton, A. Husson, S. Jegour, H. Vaudry, and J. P. Salier. 1998. Hepatic and extra-hepatic transcription of inter-alpha-inhibitor family genes under normal or acute inflammatory conditions in rat. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 350:315-323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eckersall, P. D., F. J. Young, C. McComb, C. J. Hogarth, S. Safi, A. Weber, T. McDonald, A. M. Nolan, and J. L. Fitzpatrick. 2001. Acute phase proteins in serum and milk from dairy cows with clinical mastitis. Vet. Rec. 148:35-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eckersall, P. D., H. Parton, J. G. Conner, A. S. Nash, T. Watson, and T. A. Douglas. 1988. Acute reactants in diseases of dog and cattle, p. 225-230. In D. J. Blackmore (ed.), Animal clinical biochemistry. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom.

- 15.Godson, D. L., M. Campos, S. K. Attah-Poku, M. J. Redmond, D. M. Cordeiro, M. S. Sethi, R. J. Harland, and L. A. Babiuk. 1996. Serum haptoglobin as an indicator of acute phase response in bovine respiratory disease. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 51:277-292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.González-Ramón, N., M. A. Alava, J. A. Sarsa, M. Piñeiro, M. Escartín, A. García-Gil, F. Lampreave, and A. Piñeiro. 1995. The major acute phase serum protein in pigs is homologous to human plasma kallikrein sensitive PK-120. FEBS Lett. 371:227-230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.González-Ramón, N., K. Hoebe, M. A. Alava, L. van Leengoed, M. Piñeiro, M. Iturralde, F. Lampreave, and A. Piñeiro. 2000. Pig-MAP/pig IHRP is an interleukin-6 dependent acute-phase plasma protein in porcine primary cultured hepatocytes. Eur. J. Biochem. 267:1878-1885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gruys, E., M. J. Obwolo, and M. J. M. Toussaint. 1994. Diagnostic significance of the major acute phase proteins in veterinary clinical chemistry: a review. Vet. Bull. 64:1009-1018. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hashimoto, K., T. Tobe, J. Sumiya, Y. Sano, N. H. Choi-Miura, A. Ozawa, H. Yasue, and M. Tomita. 1996. Primary structure of the pig homologue of human IHRP: inter-alpha-trypsin inhibitor family chain-related protein. J. Biochem. (Tokyo) 119:577-584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heegaard, P. M. H., D. L. Godson, M. J. M. Toussaint, K. Tjornehoj, L. E. Larsen, B. Viuff, and L. Ronsholt. 2000. The acute phase response of haptoglobin and serum amyloid A (SAA) in cattle undergoing experimental infection with bovine respiratory syncytial virus. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 77:151-159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heegaard, P. M. H., J. Klausen, J. P. Nielsen, N. González-Ramón, M. Piñeiro, F. Lampreave, and M. A. Alava. 1998. The porcine acute-phase response to infection with Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae. Haptoglobin, C-reactive protein, major acute-phase protein and serum amyloid A protein are sensitive indicators of infection. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. B 119:365-373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heinrich, P. C., J. V. Castell, and T. Andus. 1990. Interleukin-6 and the acute phase response. Biochem. J. 265:621-636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hirvonen, J., S. Pyörälä, and H. Jousimies-Somer. 1996. Acute phase response in heifers with experimentally induced mastitis. J. Dairy Res. 63:351-360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hirvonen, J., S. Pyörälä, A. Heinäsuo, and H. Jousimies-Somer. 1994. Penicillin G and penicillin G-tinidazole treatment of experimentally induced summer mastitis—effect on elimination rates of bacteria and outcome of the disease. Vet. Microbiol. 42:307-315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Horadagoda, A., P. D. Eckersall, J. C. Hodgson, H. A. Gibbs, and G. M. Moon. 1994. Immediate response in serum TNF alpha and acute phase protein concentrations to infection with Pasteurella haemolytica A1 in calves. Res. Vet. Sci. 57:129-132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kent, J. 1992. Acute phase proteins: their use in veterinary diagnosis. Br. Vet. J. 148:279-282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kushner, I. 1982. The phenomenon of the acute phase response. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 389:39-49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Laemmli, U. K. 1970. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 227:680-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lampreave, F., N. González-Ramón, S. Martínez-Ayensa, M. Hernández, H. K. Lorenzo, A. García-Gil, and A. Piñeiro. 1994. Characterization of the acute phase serum protein response in pigs. Electrophoresis 15:672-676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lowry, O. H., N. J. Rosebrough, A. I. Farr, and R. J. Randall. 1951. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J. Biol. Chem. 193:265-275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nakagawa-Tosa, N., M. Morimatsu, M. Kawasaki, H. Nakatsuji, B. Syuto, and M. Saito. 1995. Stimulation of haptoglobin synthesis by interleukin-6 and tumor necrosis factor, but not by interleukin-1, in bovine primary cultured hepatocytes. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 57:219-223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nakajima, Y., E. Momotani, T. Murakami, Y. Ishikawa, M. Morimatsu, M. Saito, H. Suzuki, and K. Yasukawa. 1992. Induction of acute phase protein by recombinant human interleukin-6 (IL-6) in calves. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 35:385-391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nishimura, H., I. Kakizaki, T. Muta, N. Sasaki, X. P. Pu, T. Yamashita, and S. Nagasawa. 1995. cDNA and deduced amino acid sequence of human PK-120, a plasma kallikrein-sensitive glycoprotein. FEBS Lett. 357:207-211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Piñeiro, M., M. A. Alava, N. González-Ramón, J. Osada, P. Lasierra, L. Larrad, A. Piñeiro, and F. Lampreave. 1999. ITIH4 serum concentration increases during acute phase processes in human patients and is upregulated by interleukin 6 in hepatocarcinoma HepG2 cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 263:224-229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Saguchi, K., T. Tobe, K. Hashimoto, Y. Sano, Y. Nakano, N.-H. Miura, and M. Tomita. 1995. Cloning and characterization of cDNA of inter-alpha-trypsin inhibitor family heavy chain related protein, a novel human plasma glycoprotein. J. Biochem. (Tokyo) 117:14-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Salier, J.-P., P. Rouet, G. Raguenez, and M. Daveau. 1996. The inter-α-inhibitor family: from structure to regulation. Biochem. J. 315:1-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sarafan, N., J.-P. Martin, J. Bourguignon, H. Borghi, A. Callé, R. Sesboüe, and M. Diarra-Mehrpour. 1995. The human inter-alpha-trypsin inhibitor genes respond differently to interleukin-6 in HepG2 cells. Eur. J. Biochem. 227:808-815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schreiber, G., G. Howlett, M. Nagashima, A. Millership, H. Martin, J. Urban, and L. Kotler. 1982. The acute phase response of plasma protein synthesis during experimental inflammation. J. Biol. Chem. 257:10271-10277. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Soury, E., E. Olivier, M. Daveau, M. Hiron, S. Claeyssens, J. L. Risler, and J. P. Salier. 1998. The H4P heavy chain of inter-alpha inhibitor family largely differs in the structure and synthesis of its proline-rich region from rat to human. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 243:522-530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tilg, H., C. A. Dinarello, and J. W. Mier. 1997. IL-6 and APPs: anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive mediators. Immunol. Today 18:428-432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tjønehøj, K., Å. Uttenthal, B. Viuff, L. E. Larsen, C. Røntved, and L. Rønsholt. 2003. An experimental infection model for reproduction of calf pneumonia with bovine respiratory syncytial virus (BRSV) based on one combined exposure of calves. Res. Vet. Sci. 74:55-65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Toussaint, M. J. M., A. M. van Ederen, and E. Gruys. 1995. Implication of clinical pathology in assessment of animal health and in animal production and meat inspection. Comp. Haematol. Int. 5:149-157. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Van Leeuwen, M. A., and M. H. van Rijswijk. 1994. Acute phase proteins in the monitoring of inflammatory disorders. Balliere's Clin. Rheumatol. 8:531-552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Whicher, J. T., R. E. Banks, D. Thompson, et al. 1993. The measurement of acute phase proteins as disease markers, p. 633-650. In A. Mackiewicz, I. Kushner, and H. Baumann (ed.), Acute phase proteins. CRC Press, Boca Raton, Fla.