Abstract

There is often over 50% carbon loss during the thermal conversion of biomass into biochar, leading to it controversy for the biochar formation as a carbon sequestration strategy. Sometimes the biochar also seems not to be stable enough due to physical, chemical, and biological reactions in soils. In this study, three phosphorus-bearing materials, H3PO4, phosphate rock tailing (PRT), and triple superphosphate (TSP), were used as additives to wheat straw with a ratio of 1: 0.4–0.8 for biochar production at 500°C, aiming to alleviate carbon loss during pyrolysis and to increase biochar-C stabilization. All these additives remarkably increased the biochar yield from 31.7% (unmodified biochar) to 46.9%–56.9% (modified biochars). Carbon loss during pyrolysis was reduced from 51.7% to 35.5%–47.7%. Thermogravimetric analysis curves showed that the additives had no effect on thermal stability of biochar but did enhance its oxidative stability. Microbial mineralization was obviously reduced in the modified biochar, especially in the TSP-BC, in which the total CO2 emission during 60-d incubation was reduced by 67.8%, compared to the unmodified biochar. Enhancement of carbon retention and biochar stability was probably due to the formation of meta-phosphate or C-O-PO3, which could either form a physical layer to hinder the contact of C with O2 and bacteria, or occupy the active sites of the C band. Our results indicate that pre-treating biomass with phosphors-bearing materials is effective for reducing carbon loss during pyrolysis and for increasing biochar stabilization, which provides a novel method by which biochar can be designed to improve the carbon sequestration capacity.

Introduction

Turning biomass into biochar through pyrolysis is being actively explored as a tool for long-term carbon sequestration in soil and as a promising strategy to mitigate global warming [1], [2]. The thermal conversion of biomass into biochar is a carbonization process which generally involves an initial carbon loss followed by aromatization. Thus, the carbon sequestration efficiency of biochar depends on both the carbon loss during pyrolysis and the stability of the final product leading to carbon emission over time [3], [4].

In general, over 50% of the carbon present in biomass is lost during pyrolysis due to thermal decomposition and volatilization. This results in low yields of biochar production, especially during the conversion of some plant-based biomasses [5]. Our recent study shows that yields of biochar produced at 500°C from twelve different biomass feedstocks ranged from 27.8% to 58.4%, but the yield of plant-based biomasses such as sawdust or crop wastes was generally low, between 27.8–32.0% [5]. In another study, Hossain et al. (2011) attained biochar yields from sludge ranging from 72.3% to 52.4% with temperatures increasing from 300°C to 700°C [6].

On the other hand, though biochar is regarded as being stable for 1000 years in soil, it still undergoes a slow cumulative degradation, which determines the dispute of biochar as a tool for long-term carbon sequestration. The potential biotic or abiotic mineralization of biochars has been reported by many researchers [6], [7]. Carbon release from abiotic incubations of biochar was 50–90% that of microbially inoculated incubations, and carbon release from both incubations generally decreased with increasing charring temperature [6]. An accelerated aging method which models the long-term stability of biochar indicated that carbon loss ranged between 41.6% and 76.1% [8].

It has been reported that rapid oxidation on the surface of biochar may have important implications for its environmental stability, because aromatic ring structures in biochar may be more available to further microbial decomposition following surface oxidation [9]. Certain chemical substances may be able to strengthen the oxidative resistance of lignocellulosic materials. For example, H3PO4 is often used during the production of activated carbon because it facilitates the generation of thermally stable phosphorus complexes on the surface of activated carbons (C–O–PO3/(CO)2PO2) [10]. These phosphorus complexes could reduce the reactivity of active sites on carbon and act as a physical barrier for oxygen diffusion in micropores [11], [12]. To the best of our knowledge, no studies have previously been conducted to study this effect on biochar yield and carbon stability of chemical or mineral additives to biomass feedstock prior to pyrolysis.

The overall objective of this study is develop a chemical pre-modification method to improve the potential carbon sequestration capacity of biochar. Thus, three P-bearing substances, including H3PO4, phosphate rock tailings (PRT), and triple superphosphate (TSP) were used as additives during biochar production. H3PO4 was chosen because it has been shown to enhance the oxidative resistance of lignin in woodchips [9]. PRT and TSP may coexist with biochar in the soil since these two phosphorus materials are widely used in soil remediation for inactivation of heavy metals [13], [14].

The specific objectives of this study were (i) to determine carbon loss during pyrolysis of the pretreated biomass, (ii) evaluate the effects of these additives on biochar chemical and biological stability, and (iii) to explore the formation mechanisms of these designed biochars.

Materials and Methods

Biomass and chemical materials

Wheat straw, a typical plant-based biomass was chosen for this study. Samples were collected from a farm located in Baoshan district in Shanghai, China. No specific field permits were required for this study. The land accessed is not privately owned or protected. No protected species were sampled. All locations used in our study did not involve endangered or protected species. The samples was air-dried to a moisture content of <2% and ground to <1 mm prior to pyrolysis. PRT and TSP are rich in P (14.1% and 20.2%, respectively) and their main constituents are Ca5(PO4)3F and Ca(H2PO4)2·2H2O, respectively [15]. PRT is alkaline and slightly soluble in water, while TSP is acidic and highly water soluble [15]. The ground wheat straw was immersed in the water slurry of these materials and mixed homogenously. After 24 h, the pretreated wheat straw was air-dried and put into pyrolysis system to produce biochars [11], [12]. The biomass/additive ratios were within a range of 1: 0.4–0.8: wheat straw/H3PO4 (g/g) 1: 0.86; wheat straw/PRT (g/g) 1: 0.5; and wheat straw/TSP (g/g) 1: 0.4. The ratios were chosen to ensure that the P composition is enough for mixing with the biomass completely for their full contact in the process of biochar formation.

Biochar production

Biochar production was conducted in a laboratory-scale pyrolysis system with a stainless steel column of about 3.5 L in a muffle furnace [16]. The production was performed under N2 gas with the highest treatment temperature at 500°C. Briefly, about 100 g unmodified or chemically modified wheat straw was weighed into the pyrolyzer, and the heating temperature was then raised at 15°C·min−1 to reach four settled gradient temperatures (200°C, 300°C, 400°C and 500°C). At each gradient temperature, the heat temperature was held for 1 h, respectively, to allow enough time for carbonization. Biochar production is an aromatization process, in which volatile compounds are separated from biomass and the rest of carbon is converted to chemically and biological recalcitrant forms. Upon heating, the organic compounds are initially cracked at different temperatures to smaller and unstable fragments. These highly reactive fragments, mainly free radicals with a very short average lifetime, can polymerize into a recalcitrant aromatic structure. Thus it is assumed the gradual temperature enabled biomass components to thoroughly carry out the decomposition and aromatization process. After the pyrolysis treatment was completed, the carbon-rich solid left in the pyrolyzer was the biochar product [5]. For simplicity, the biochars without pre-modification and pre-modified with H3PO4, PRT, and TSP were referred to as BC, H3PO4-BC, PRT-BC, and TSP-BC, respectively. The experiments were conducted in three replicates.

Characterization

Biochar pH was measured in de-ionized water with a solid/liquid ratio of 1∶20 (w/v) after 48 h equilibrium (EUTECH pH510, USA). The elements concentration was measured using an element analyzer (Vario EL III, Elementar, Germany). The bonding environments of P and C atoms (P 2p, C 1s) on the surface of biochar particles were determined using XPS (AXIS UltraDLD, Shimadzu, Japan) with a beam diameter of 200.0 mm and a pass energy of 26 eV. The solid phases of biochar were characterized by X-ray diffraction (D/max-2200/PC, Japan Rigaku Corporation) operated at 35 kV and 20 mA. Data was collected over 2θ range from 10 to 50 using Cu Kα radiation with a scan speed of 2o per minute.

Carbon loss and residue during biochar formation in pyrolysis

Biochar yield (%) was calculated based on the weight of biomass and additives lost during pyrolysis (eq. 1).

| (1) |

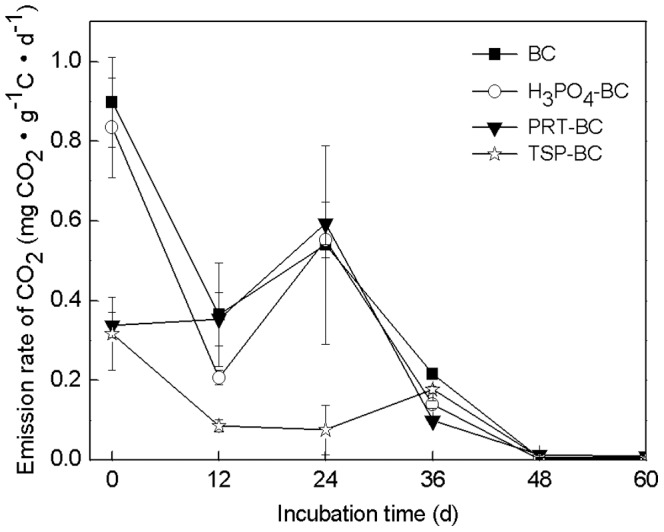

Carbon loss after pyrolysis was calculated based on yield and total carbon content (eq. 2).

|

(2) |

TCbiomass, TCadditive and TCbiochar refer to the total carbon (TC) content in biomass, additive, and biochar, respectively. Wbiomass and Wadditive refer to the weight of biomass and additive, respectively; whereas, additives were inorganic substances and contained negligible amounts of TC.

Fixed carbon (FC) represents a relatively stable fraction of carbon in char as calculated by proximate analysis [17]. The FC calculation is shown in eq 3.

| (3) |

Volatile solid (VS) is calculated as the weight loss of material under N2 atmosphere at 900°C, and ash is evaluated as the weight loss of material under air atmosphere at 900°C.

Measurement of biochar carbon stability

Three methods were applied to test carbon stability of biochar including heat-resistance stability, oxidation-resistance stability, and microbe-resistance stability. Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) of the materials under N2 and air were used as quick and convenient methods to evaluate the heat-resistance stability and oxidation-resistance stability of each material, respectively [18]. The TGA curves were obtained by heating biochar from 25°C to 900°C at 20°C·min-1 on the machine (PerkinElmer Pyris 1 TGA) under both N2 flow and atmospheric air. The TGA analysis can simultaneously provide data for analysis of material constituents. For example, the weight loss before 200°C is generally regarded as moisture removal, and the subsequent weight loss can be largely attributed to the decomposition of organic matter [19].

The biological carbon stability of biochar was measured by performing microbial mineralization analysis in sterilized 20 mL borosilicate vials with rubber septa. This method used a simulated microbial soil condition which was widely used in previous reports [7], [9]. Before incubation, the biochars were washed several times to eliminate the volatile smaller molecules from the decomposition of organic matters attached on the surface of the biochars and equalize their initial pH values. For each treatment, three replicate incubations of 0.05–0.30 g of biochar and clean quartz sand with 0.3 mL aqueous nutrient solution [60 g·L−1 of (NH4)2SO4 +6 g·L−1 of KH2PO4] were conducted [7]. The addition of sand served to increase permeability, thus increasing the water and oxygen accessibility for the biochar. To culture the bacteria for inoculation, a soil containing bird droppings was taken from a university forest and extracted with deionized water at a 1∶50 solid/liquid ratio (W/V). The supernatant was used for inoculation, and 0.3 mL of inoculation solution was added into the biochar-sand system. The materials were at 30°C. Headspace CO2 was measured every 6–10 days using gas chromatography (GC-2010AF, Shimadzu, Japan). Before each measurement, the vials were vacuumed evacuated and 20 mL simulated air (O2 and N2) with CO2 removed was injected into the vials. After 3 days of closed incubation, the released CO2 due to decomposition was measured.

Results and Discussion

Selected properties of biomass and modified biochars

The compositions of all biochars were presented in Table 1. The C content of H3PO4-BC and PRT-BC were relative low (28.3% and 29.8%) because of the contribution of the additives residue to the total biochar weight. The N content was a little higher in the PRT-BC and TSP-BC than in other biochars because these two minerals contain a fraction of N. It indicates that the PRT- and TSP-modified biochars may have a better fertility than the unmodified ones. The wheat straw contained a high O content as 41.5%, and biochars contained less O (7.84–29.6%). In H3PO4-BC, O content is relative high (29.6%), compared with the unmodified biochar (11.6%), which was due to the formation of calcium metaphosphate. P content was 12.5%, 5.98% and 6.78% in the H3PO4-BC, PRT-BC and TSP-BC, while the value was low in BC. Biochar yields were elevated with the addition of additives, increasing from 31.7% (unmodified biochar) to 40.3%–56.9% (modified biochars) (Table 1). Both PRT-BC and TSP-BC contained higher ash contents (69.3% and 51.9%, respectively) than H3PO4-BC (25.2%) (Table 1).

Table 1. Selected properties of biomass and biochars.

| Wheat straw | BC | H3PO4-BC | PRT-BC | TSP-BC | |

| pH | 6.01 | 7.77 | 1.51 | 8.04 | 3.89 |

| C (%) | 46.8a | 69.1 | 28.3 | 29.8 | 40.8 |

| H (%) | 0.151 | 0.285 | 0.023 | 0.655 | 0.541 |

| N (%) | 0.329 | 0.691 | 0.227 | 1.97 | 2.03 |

| O (%) | 41.5 | 11.6 | 29.6 | 7.84 | 14.3 |

| P (%) | 0.112 | 0.116 | 12.5 | 5.98 | 6.78 |

| Yield (%) | - | 31.7 | 56.9 | 54.4 | 46.9 |

| ASH (%) | 4.35 | 27.1 | 25.2 | 69.3 | 51.9 |

| VS (%) | 78.6 | 13.0 | 57.6 | 12.8 | 12.0 |

| FC (%) | 17.1 | 59.9 | 17.2 | 17.9 | 36.1 |

PRT: phosphate rock tailing; TSP: triple superphosphate; TC: total carbon; VS: volatile solid; FC: fixed carbon. a Mean value (n = 3)

The inclusion of different additives in the process of biochar production resulted in changes in their properties (Table 1). The pH value of unmodified biochar was 7.77, falling within the general alkaline pH range of biochars, between 7.5–10.5 [5], [20]. H3PO4 and TSP addition resulted in biochars with stronger acidity (pH = 1.51 and 3.89, respectively), and PRT-BC was alkaline (pH = 8.04). The pH of the modified biochars likely resulted largely from the acidity or alkalinity of the additive itself.

The physicochemical properties of the modified biochars such as point of zero net charge, cation exchange capacity, specific surface area, etc, were not investigated because carbon residue and carbon stability of biochar are the main focuses of this study. These properties will be investigated in detail in future studies.

Carbon conversion during pyrolysis

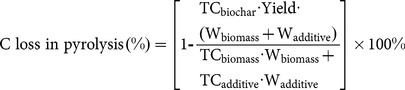

Routine yield which is calculated only from the weight change during the biomass conversion (i.e., eq 1) does not represent the real carbon-negativity of biomasses; thus, the entire carbon budget was evaluated in this study. The total carbon loss calculated from eq. 2 is presented in Fig. 1. There was 51.7% carbon loss during wheat straw conversion into biochar. However, addition of all P-containing chemicals greatly alleviated the carbon loss to 35.5–47.7%, with the carbon loss reduced by 7.74–31.4% compared to the unmodified biochar. The underlying mechanisms for carbon loss alleviation will be discussed in the next sections. The extent of the alleviation may differ with different feedstock and production conditions, which needs separate investigation.

Figure 1. Carbon loss during pyrolysis for biochar production from wheat straw at 500°C with different modifications.

The FC content of the biochars is presented in Table 1. FC is a fraction of biochar and represents a relatively stable fraction in biochar which enables it to be the “sequestrated C”. FC partially originates from feedstock carbon, but it is also a conversion product from pyrolysis processes [20]. FC was calculated as the non-ash fraction that could be burned in air but not be lost in N2 at 900°C. The FC values for H3PO4-BC, PRT-BC and TSP-BC were 17.2%, 17.9% and 36.1%, respectively, which were lower than that of the control BC (59.9%). Note that the relative low FC values were due to the high ASH content in PRT-BC and the high VS fraction in H3PO4-BC.

Thermal and oxidation stability of modified biochars

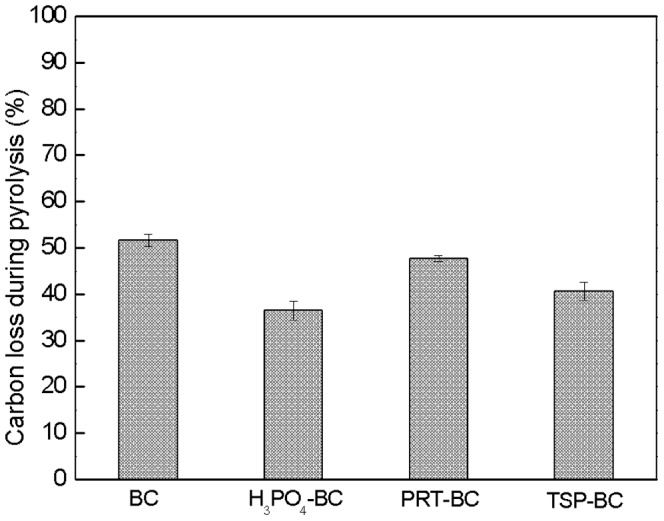

TGA curves of biochars over the temperature ranging from 25°C to 900°C under N2 conditions are shown in Fig. 2a, which reflects the thermal stability of biochar. The modified biochars had similar TGA curves to the unmodified biochar. The majority of weight loss occurred from 600°C to 900°C after a minor weight loss from 200°C to 500°C (Fig. 2a). H3PO4-BC showed a larger initial weight loss than the other biochars. The main weight loss of biochar was most likely due to the decomposition of either organic fractions of the carbon skeleton or some combination of carbon and additives (see section 3.5). Overall, there was not much difference in the temperature at which the main weight loss occurred between the unmodified and modified biochars, indicating that these additives had no influence on the thermal stability of biochars.

Figure 2. TGA curves of the biochars in N2 (a) and air (b) atmosphere.

The mass loss of biochars in air is generally related to their oxidative stability, and it is believed that the more stable a substance is, the higher the temperature needs to be for decomposition [21]. Fig. 2b shows TGA curves of biochars under normal air conditions. All the modified biochars decomposed at higher temperatures (490°C–650°C) than the unmodified ones (400°C), especially the H3PO4-BC (650°C). The results indicate that these additives could increase the oxidative stability of biochar. Significant oxidation inhibition by phosphorus has also been observed in many other carbon materials production [22], [23], [24] and possible mechanisms will be discussed in section 3.5.

Microbe-resistance stability of modified biochars

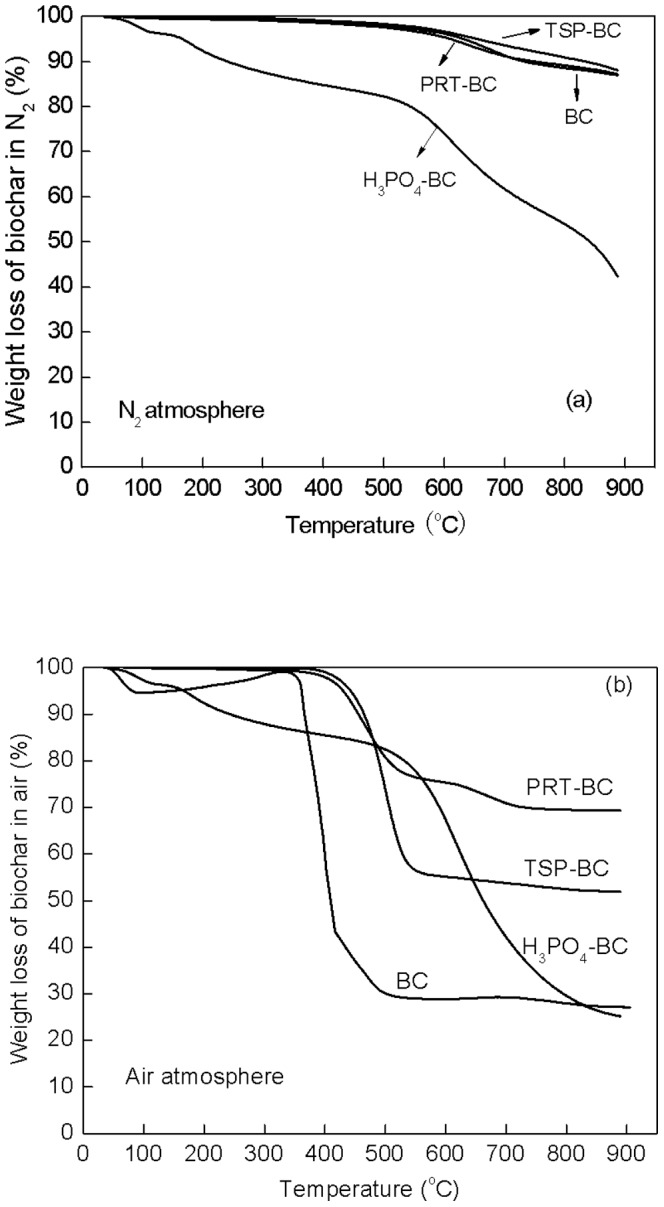

The emission rate of CO2 from biochar during aerobic incubation represents its biological mineralization stability [25], [26]. The pH of these materials fluctuated in the range of 5.5–6.5, which was appropriate for the microbial activity. All additives were observed to reduce the CO2 emission rate from biochar to some extent (Fig. 3). TSP-BC showed the lowest mineralization rate. The decrease in mineralization rate by H3PO4 and PRT was also significant. The majority of change in the CO2 emission rates occurred within the first 36 days. After the 48th day, the CO2 emission of all samples decreased to a very low level, and the differences among the unmodified and modified biochar seemed unremarkable. However, because biochar can be oxidized in the soil for many years, small differences in CO2 emissions may have a significant effect if summed over a long period of time, thus, long-term stability of modified biochar needs further investigation. Note that the evaluation of biological stability was made in this work using a simulated microbial soil condition [7], [9]. However, the stability of biochar may also be influenced by soil properties such as soil pH, soil carbon content and the presence of other organic substances. Therefore, incubation tests of modified biochar in a real soil system should be conducted in a future study [27].

Figure 3. Emission rates of CO2 from the biochars during aerobic incubation.

The cumulative CO2 emission amount during the 60-day aerobic incubation was calculated according to the average emission rates every 12 days, which were 18.9, 15.8, 14.8 and 6.09 mg CO2· g C−1 for BC, H3PO4-BC, PRT-BC, and TSP-BC, respectively. H3PO4, PRT, and TSP treatments reduced microbial CO2 emission of biochar by 16.4%, 21.7%, and 67.8%, compared to unmodified biochar. Many studies concluded that the main CO2 emission occurred in the first 60 days [7], [28]; thus, the obvious decrease in CO2 emission during the 60-day incubation period in this study suggests that the three additives could enhance the biological mineralization stability of biochar. The effectiveness followed the trend TSP>PRT>H3PO4.

Interference of phosphorus on biomass pyrolysis

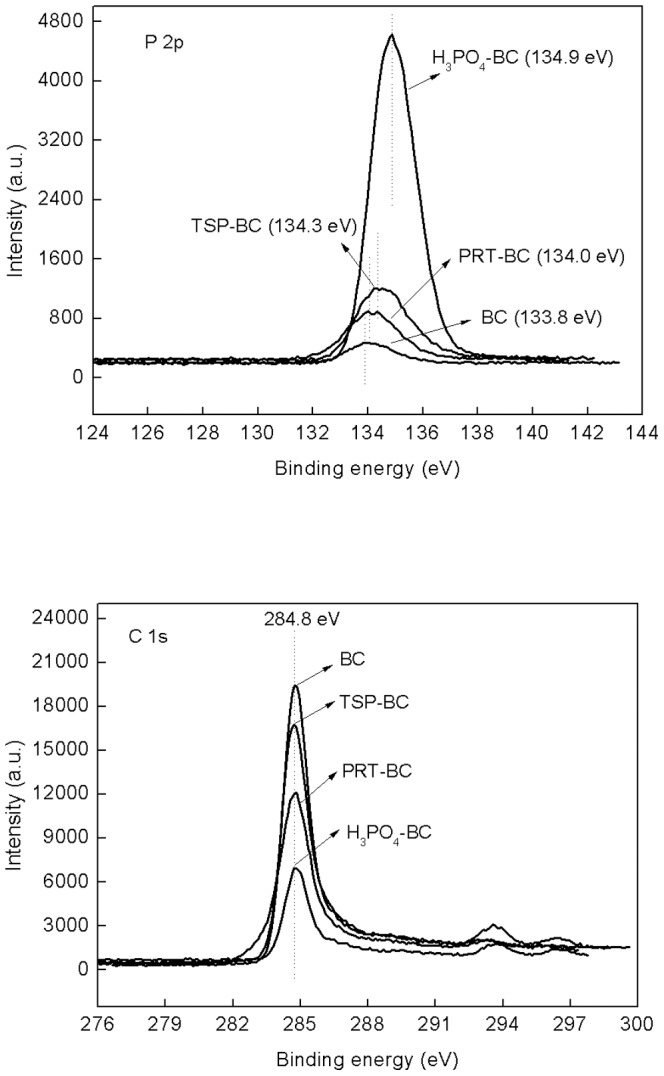

It is not surprising that inorganic substances have influence on the charcoal yield, product distribution, or product selectivity during pyrolysis [29]–[32]. For example, iron improved the O-containing functional groups of biochar [33]. In this study, the exact reactions between the additives and wheat straw cannot yet be determined, but potential mechanisms of modification effects on biochar carbon residue and stability could be proposed according to the results obtained from this study. Fig. 4 shows the XPS spectra of P 2p and C 1s electron (spin-orbit) for the unmodified and modified biochars. The additives made the peak of P 2p shift from low binding energy (BC: 133.8 eV) to higher binding energy (H3PO4: 134.9 eV; PRT: 134.0 eV; TSP: 134.3 eV). The binding energy intensity of the main C 1s peak at 284.8 eV was almost not changed (Fig. 4b), while the height of the peaks was decreased by the introduction of the additive materials. This indicates that the surface C content was reduced.

Figure 4. XPS spectra of P 2p and C 1s electron for the unmodified and modified biochars.

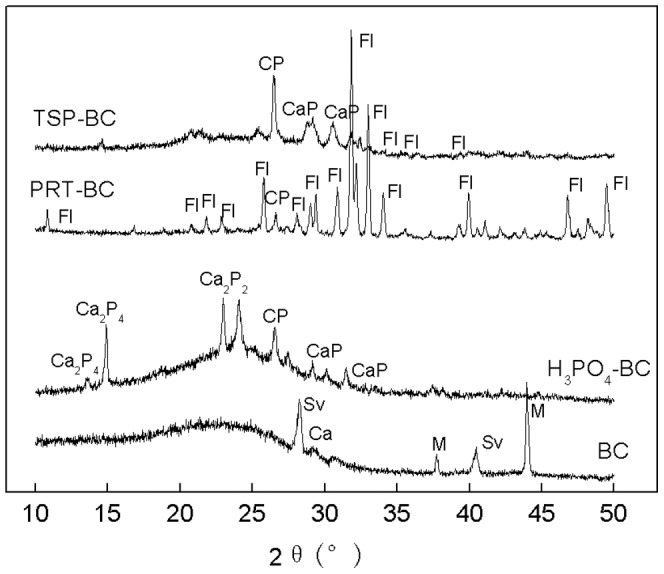

A P 2p peak around 135.0 eV is generally assigned to metaphosphate or C-O-PO3 type groups [34], [35]. Addition of chemicals, especially H3PO4, increased the P 2p peak from 133.8 eV in unmodified BC to about 135 eV, indicative of the P-C compounds formation. This observation agrees with previous findings that H3PO4 addition mainly resulted in the formation of oxygen-containing phosphorus groups which may include metaphosphates, C–O–PO3 groups, or C–PO3 groups [34], [35]. These groups are suggested to act as a physical barrier against carbon decomposition, as well as to block the active carbon sites [22], [18], resulting in reduced oxidation and mineralization of biochar. Formation of P-C compounds was further evidenced by X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis (Fig. 5). Compared to the unmodified BC, a new peak at 2θ0 = 26.6, most likely corresponding to the P-C compounds was observed in the H3PO4-BC and TSP-BC. Although PRT is also rich in P, it is less soluble, allowing it behave differently from soluble TSP and H3PO4. A weak peak of P-C compounds was observed at 2θ0 = 26.6 in the PRT-BC (Fig. 5). Qian et al. (2014) pointed out that the P-containing radicals react with the aromatic rings produced by the pyrolysis of lignin to form P-containing species, which is an important factor influencing the distribution and stabilization of P in char [36]. Uchimiya and Hiradate (2014) indicated that orthophosphate such as CH3−O−PO3 2− and phenyl−O−PO3 2− formed in pyrolysis were stable [37]. Klupfel et al. (2014) also proposed that biochar has redox properties and acts as electron-donating [38]. This indicated that P has potential to react with the carbon in biochar. Overall, all three P-bearing additives induced the formation of P-C compounds.

Figure 5. X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of the unmodified and modified biochars.

According to the results of this study, the P-bearing additives seemed to have no influence on the thermal stability of biochar products, but they did improve oxidative stability and biological degradation. Thermal stability is a function of bond energy, while both the incineration of volatile matters and the carbon to CO2 conversion require contact between C and O2 or bacteria. Thus it could be speculated that the bond energy of the reaction products from additives is low, and these additives could also form a physical layer to hinder the contact of C with O2 or bacteria or occupy the active sites of the carbon band.

Implications in application of biochar as a carbon fixer

Although biochar has been considered as a multi-functional material for improving the environment in many different ways, its primary environmental significance has always been carbon sequestration [39], [40]. However, challenges for the effectiveness of biochar as a carbon fixer still remain. About half of the initial carbon from the biomass is not converted to biochar during pyrolysis, and the final biochar product is still not as stable as necessary for long-term carbon sequestration, which causes biochar to remain a controversial carbon fixer [41].

This study presents a novel idea that biochars with high carbon content residue and stability can be designed using pre-modification during the feedstock preparation. The P-containing materials chosen did show a tendency to act as passivators to reduce carbon loss during pyrolysis and enhance the stability of biochar, though the two effect extents were not consistent with one specific additive. The potential capacity of carbon sequestration is expected to be improved through the regulation of process conditions. Additionally, these modifications might change biochar's physicochemical properties, which may affect the soil environment when biochar is applied into soil as a carbon sequestration tool. Additional benefits to the soil may also be obtained; for example, the modified PRT-BC and TSP-BC contain high P which may be effective in immobilizing heavy metals in contaminated soils [42], [43]. Of course, it must be noted that the low pH value of the H3PO4-BC biochar may limit its soil application in acidic soils.

Overall, there is some promise that biochar can be designed to provide multi-win effects, i.e., carbon sequestration, soil improvement, and contamination remediation.

Conclusions

During the charring process of biomass to biochar, over 50% carbon is typically lost, and the generated biochar may not be stable enough in soil due to physical, chemical, and biological reactions. In this study, the biomass precursor was pre-treated using three P-bearing chemical substances including H3PO4, PRT and TSP, aiming to reduce carbon loss during charring and simultaneously increase the carbon stability of the final biochar product. The results show that these chemicals reduced the carbon loss, improved the oxidation stability and reduced the microbial mineralization. This study put forward the novel idea that people can design biochar to improve its carbon residue and stability through passivator addition during feedstock preparation, which enables it to be a prospective tool for carbon sequestration.

Data Availability

The authors confirm that all data underlying the findings are fully available without restriction. All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 21107070, 21377081), Shanghai Science and Technology Commission (13231202502), and Shanghai Education Commission (14ZZ026). This work was also partially supported by State Key Laboratory of Pollution Control and Resource Reuse Foundation (NO. PCRRF12009). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Whitman T, Nicholson CF, Torres D, Lehmann J (2011) Climate change impact of biochar cook stoves in western Kenyan farm households: System dynamics model analysis. Environ. Sci. Technol. 45:3687–3694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Meyer S, Bright RM, Fischer D, Schulz H, Glaser B (2012) Albedo impact on the suitability of biochar systems to mitigate global warming. Environ. Sci. Technol. 46:12726–12734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mathews JA (2008) Carbon-negative biofuels. Energy Policy 36:940–945. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Matovic D (2011) Biochar as a viable carbon sequestration option: Global and Canadian perspective. Energy 36:2011–2016. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zhao L, Cao XD, Masek Q, Zimmerman A (2013) Heterogeneity of biochar properties as a function of feedstock and production temperatures. J Hazard Mater. 256:1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hossain MK, Strezov V, Chan KY, Ziolkowski A, Nelson PF (2011) Influence of pyrolysis temperature on production and nutrient properties of wastewater sludge biochar. J Environ Manage. 92:223–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zimmerman AR (2010) Abiotic and microbial oxidation of laboratory-produced black carbon (Biochar). Environ. Sci. Technol. 44 1295–1301:4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cross A, Sohi SP (2013) A method for screening the relative long-term stability of biochar. GCB Bioenergy 5:215–220. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cheng CH, Lehmann J, Thies JE, Burton SD, Engelhard MH (2006) Oxidation of black carbon by biotic and abiotic processes. Org. Geochem. 37:1477–1488. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Rosas JM, Ruiz-Rosas R, Rodriguez-Mirasol J, Cordero T (2012) Kinetic study of the oxidation resistance of phosphorus-containing activated carbons. Carbon 50:1523–1537. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lu WM, Chung DDL (2002) Oxidation protection of carbon materials by acid phosphate impregnation. Carbon 40:1249–1254. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wu XX, Radovic LR (2006) Inhibition of catalytic oxidation of carbon/carbon composites by phosphorus. Carbon 44:141–151. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cao XD, Ma LQ, Singh SP, Chen M, Harris WG (2003) Phosphate induced metal immobilization in a contaminated site. Environ. Pollut. 122:19–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Park JH, Bolan N, Megharaj M, Naidu R (2011) Isolation of phosphate solubilizing bacteria and their potential for lead immobilization in soil. J. Hazard. Mater. 185:829–836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Cao XD, Liang Y, Zhao L, Le HY (2013) Mobility of Pb, Cu, and Zn in the phosphorus-amended contaminated soils under simulated landfill and rainfall conditions. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 20:5913–5921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Cao XD, Ma LQ, Liang Y, Harris W (2011) Simultaneous immobilization of lead and atrazine in contaminated soils using dairy-manure biochar. Environ. Sci. Technol. 45:4884–4889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. ASTM D 3172–07a Standard practice for proximate analysis of coal and coke (2007) [Google Scholar]

- 18. Li KZ, Song Q, Qi Q, Ren C (2012) Improving the oxidation resistance of carbon/carbon composites at low temperature by controlling the grafting morphology of carbon nanotubes on carbon fibres. Corros. Sci. 60:314–317. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cao XD, Harris W (2010) Properties of dairy-manure-derived biochar pertinent to its potential use in remediation. Bioresour. Technol. 101:5222–5228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cantrell KB, Hunt PG, Uchimiya M, Novak JM, Ro KS (2012) Impact of pyrolysis temperature and manure source on physic-chemical characteristics of biochar. Bioresour. Technol. 107:419–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Harvey OR, Kuo LJ, Zimmerman AR, Louchouarn P, Amonette JE, et al. (2010) An index-based approach to assessing recalcitrance and soil carbon sequestration potential of engineered black carbons (Biochars). Environ. Sci. Technol. 46:1415–1421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lee YJ, Radovic LR (2003) Oxidation inhibition effects of phosphorus and boron in different carbon fabrics. Carbon 41:1987–1997. [Google Scholar]

- 23. McKee DW, Spiro CL, Lamby EJ (1984) The inhibition of graphite oxidation by phosphorous additives. Carbon 22:285–290. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Oh SG, Rodriguez NM (1993) In situ electron microscopy studies of the inhibition of graphite oxidation by phosphorus. J. Hazard. Mater. 8:2879–2888. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Spokas KA, Koskinen WC, Baker JM, Reicosky DC (2009) Impacts of woodchip biochar additions on greenhouse gas production and sorption/degradation of two herbicides in a Minnesota soil. Chemosphere 77:574–581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Novak JM, Busscher WJ, Watts DW, Laird DA, Ahmedna MA, et al. (2010) Short-term CO2 mineralization after additions of biochar and switchgrass to a Typic Kandiudult. Geoderma 154:281–288. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kuzyakov Y, Subbotina I, Chen HQ, Bogomolova I, Xu XL (2009) Black carbon decomposition and incorporation into soil microbial biomass estimated by 14C labeling. Soil Biol. Biochem. 41:210–219. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bruun S, Jensen ES, Jensen LS (2008) Microbial mineralization and assimilation of black carbon: Dependency on degree of thermal alteration. Org. Geochem. 39:839–845. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Richards GN, Zheng G (1991) Influence of metal ions and of salts on products from pyrolysis of wood: applications to thermochemical processing of newsprint and biomass. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 21:133–146. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Antal MJ Jr, Mok WSL, Varhegyi G, Szekely T (1990) Review of methods for improving the yield of charcoal from biomass. Energy & Fuels 4:221–225. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wan YQ, Chen P, Zhang B, Yang CY, Liu YH, et al. (2009) Microwave-assisted pyrolysis of biomass: Catalysts to improve product selectivity. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 86:161–167. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Trompowsky PM, Benites VDM, Madari BE, Pimenta AS, Hockaday WC, et al. (2005) Characterization of humic like substances obtained by chemical oxidation of eucalyptus charcoal. Org. Geochem. 36:1480–1489. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Peng L, Ren YQ, Gu JD, Qin PF, Zeng QR, et al. (2014) Iron improving bio-char derived from microalgae on removal of tetracycline from aqueous system. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 21:7631–7640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Yao FX, Arbestain MC, Virgel S, Blanco F, Arostegui J, et al. (2010) Simulated geochemical weathering of a mineral ash-rich biochar in a modified soxhlet reactor. Chemosphere 80:724–732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. LeCroy C, Masiello CA, Rudgers JA, Hockaday WC, Silberg JJ (2013) Nitrogen, biochar, and mycorrhizae: Alteration of the symbiosis and oxidation of the char surface. Soil Biol. Biochem. 58:248–254. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Qian TT, Li DC, Jiang H (2014) Thermochemical behavior of Tris (2-Butoxyethyl) phosphate (TBEP) during co-pyrolysis with biomass. Environ. Sci. Technol. 48:10734–10742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Uchimiya M, Hiradate S (2014) Pyrolysis temperature-dependent changes in dissolved phosphorus speciation of plant and manure biochars. J. Agric. Food. Chem. 62:1802–1809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Klupfel L, Keiluweit M, Kleber M, Sander M (2014) Redox properties of plant biomass-derived black carbon (biochar). Environ. Sci. Technol. 48:5601–5611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Meyer S, Glaser B, Quicker P (2011) Technical, economical, and climate-related aspects of biochar production technologies: a literature review. Environ. Sci. Technol. 45:9473–9483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lehmann J, Joseph S (2009) Biochar for environmental management: science and technology. Earthscan London. 73p.

- 41. Bruun S, Luxhoi J (2008) Is biochar production really carbon-negative? Environ. Sci. Technol. 42:1388–1388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Cao XD, Wahbi A, Ma LQ, Li B, Yang YL (2009) Immobilization of Zn, Cu, and Pb in contaminated soils using phosphate rock and phosphoric acid. J. Hazard. Mater. 164:555–564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Fang YY, Cao XD, Zhao L (2012) Effects of phosphorus amendments and plant growth on the mobility of Pb, Cu, and Zn in a multimetal-contaminated soil. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 19:1659–1667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The authors confirm that all data underlying the findings are fully available without restriction. All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.