Abstract

Background

HIV is hyperendemic in Swaziland with a prevalence of over 25% among those between the ages of 15 and 49 years old. The HIV response in Swaziland has traditionally focused on decreasing HIV acquisition and transmission risks in the general population through interventions such as male circumcision, increasing treatment uptake and adherence, and risk-reduction counseling. There is emerging data from Southern Africa that key populations such as female sex workers (FSW) carry a disproportionate burden of HIV even in generalized epidemics such as Swaziland. The burden of HIV and prevention needs among FSW remains unstudied in Swaziland.

Methods

A respondent-driven-sampling survey was completed between August-October, 2011 of 328 FSW in Swaziland. Each participant completed a structured survey instrument and biological HIV and syphilis testing according to Swazi Guidelines.

Results

Unadjusted HIV prevalence was 70.3% (n = 223/317) among a sample of women predominantly from Swaziland (95.2%, n = 300/316) with a mean age of 21(median 25) which was significantly higher than the general population of women. Approximately one-half of the FSW(53.4%, n = 167/313) had received HIV prevention information related to sex work in the previous year, and about one-in-ten had been part of a previous research project(n = 38/313). Rape was common with nearly 40% (n = 123/314) reporting at least one rape; 17.4% (n = 23/314)reported being raped 6 or more times. Reporting blackmail (34.8%, n = 113/314) and torture(53.2%, n = 173/314) was prevalent.

Conclusions

While Swaziland has a highly generalized HIV epidemic, reconceptualizing the needs of key populations such as FSW suggests that these women represent a distinct population with specific vulnerabilities and a high burden of HIV compared to other women. These women are understudied and underserved resulting in a limited characterization of their HIV prevention, treatment, and care needs and only sparse specific and competent programming. FSW are an important population for further investigation and rapid scale-up of combination HIV prevention including biomedical, behavioral, and structural interventions.

Background

Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) is hyperendemic in Swaziland with a prevalence of approximately 26.1% in 2007 among reproductive age adults [1]. This equates to an estimated 170,000 adults living with HIV in 2012. In addition, HIV prevalence in Swaziland is higher among women, who represent 59% of the people living with HIV (PLWHIV), an increase since 2001 when 57% of the PLWHIV were women [2]. While the prevalence of HIV has increased, similar to other generalized epidemic settings the incidence rate likely peaked in approximately 1999 at almost 6% [3]. There appears to have been declines in incidence with 6,054 person years (PY) of follow up data from 11,880 HIV-negative individuals enrolled into a longitudinal cohort and followed from December 2010 – June 2011 as part of the Swaziland HIV Incidence Measurement Survey (SHIMS) study [4], [5]. Incidence was nearly twice as high among women as compared to men (3.14/100PY vs. 1.65/100PY) with overall incidence of approximately 2.4% (95% CI 2.1–2.7%). The highest incidence rate of 4.2% was observed among women 20–24 years old, with a second peak of incidence at 4.2% in women 35–39 years old. While sex work was not assessed in the SHIMS study, higher number of partners and self-reported pregnancy were strongly associated with incident HIV infection. In addition, women who reported not being married or living with partner were also at higher risk of HIV acquisition (adjusted Hazard Ratio of 3.1, 95% CI 1.6–5.7) [4].

There have been limited epidemiologic studies evaluating the burden of HIV among FSW in the generalized epidemics of Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) [6]. However, where data are available, there is a consistent trend of high burdens of HIV among female sex workers (FSW). A meta-analysis of HIV prevalence studies including 21,421 FSW across SSA demonstrated FSW had more than 14 times increased odds of living with HIV compared to other women [7]. Specifically, the HIV prevalence among FSW in SSA was 36.9% compared to 7.4% among reproductive age women. In a study of 1,050 women in Swaziland and Botswana, 5% reported transactional sex, and this was significantly associated with food insecurity [8]. There are also some data highlighting the higher HIV prevalence of women with a greater number of sexual partners, including the most recent Swaziland Demographic Health Survey (DHS) which found that HIV prevalence was 52.3% among women reporting two or more partners in the preceding 12 months as compared to 38.8% in those reporting zero partners [9]. The report did not assess sex work, making it impossible to assess to what extent commercial sex may have been involved in these higher numbers of sexual partners. Small rapid assessments exploring the dynamics and practices of FSW were conducted in Swaziland in 2002 and 2007 [10]. While sample sizes were small, these two studies highlighted a population at high risk for HIV acquisition and transmission. In a qualitative study among 20 FSW living with HIV in Swaziland, Fielding-Miller (2014) describes a cyclical pathway of hunger, food insecurity, social stigma, sex work, and HIV infection{Fielding-Miller, 2014 #62}. A recent study of FSW from Botswana, Namibia, and South Africa also demonstrated high levels of risk for both HIV and human rights abuses among FSW [11]. Specifically, participatory methods were used to identify high levels of sexual and physical abuse, as well as extortion, from law enforcement officers such as police and border guards [11]. The prevalence of these abuses experienced by FSW in Swaziland, where sex work is criminalized, is unknown. A study of sex workers in east and southern Africa found that participants had unmet health needs such as diagnosis and treatment of sexually transmitted infection and access to condoms [12]. Many sex workers in the same study reported they were denied treatment for injuries following physical or sexual assault or faced hostility from health providers.

The 2009 Swaziland Modes of Transmission (MoT) study reported that major drivers of HIV incidence included multiple concurrent partnerships before and during marriage as well as low levels of male circumcision [3]. The MoT suggested that both sex work and male-male sexual behaviors are infrequently reported and are potentially minor drivers of HIV risk in the widespread epidemic of Swaziland [3]. The MoT further highlighted that it is difficult to accurately conclude the role of key populations in larger transmission dynamics as well as their respective vulnerabilities and health care needs because of limited data.

While there has been no targeted HIV prevalence study among FSW in Swaziland, there are several emerging studies exploring concentrated HIV subepidemics in the context of broadly generalized HIV epidemics in other countries in the region [13]. Taken together, these studies suggest that even in a generalized epidemic setting such as Swaziland, these women likely carry a disproportionate burden of HIV due to a confluence of biological, behavioural, and structural risks for HIV infection. This study aimed to describe an unbiased estimate of HIV prevalence among FSW in Swaziland and characterize behavioral factors associated with HIV infection, including individual sexual practices, the composition of sexual networks, concurrent partnerships, substance use, and access to clinical health care and prevention services.

Methods

Sampling methods have been previously described [14]. Briefly, a respondent-driven-sampling (RDS) survey was completed between August and October, 2011 of 328 adult women who reported selling sex for money in the previous 12 months in Swaziland [15]. Each participant completed a structured survey instrument and biological HIV and syphilis testing and counseling according to Swazi national guidelines. The survey instrument included a comprehensive assessment of HIV risk with modules including demographics, human rights issues, sexual practices, HIV-related knowledge, condom negotiation, social capital, and reproductive history [16]. Interviews lasted approximately one hour and were conducted in private rooms with trained staff and with no personally identifiable information collected at any point.

Analysis

Population weights were computed separately for each variable by the data-smoothing algorithm using RDS for Stata [17]. The weights were used to estimate RDS-adjusted univariate estimates with bootstrapped 95% confidence intervals. Crude bivariate analysis was also conducted to assess the association of HIV status with demographic variables as well as selection of variables that were either expected or have been shown to be associated with HIV status in the literature [16]. All demographic variables were then included in the multivariate logistic regression model regardless of estimated strength of their crude bivariate association with HIV status. Non-demographic variables were included in the multivariate model if the chi-square p-value of association with HIV status was less than or equal to 0.25.

Although regression analyses of RDS data using sample weights is complicated due to the fact that weights are variable-specific, as noted by Johnston et al., we conducted RDS-adjusted bivariate and multivariate analyses and used the estimates in our sensitivity analyses of the crude estimates [18]. The adjusted odds ratio estimates differed little from the unweighted estimates in both bivariate and multivariate analyses, and therefore we only report the unweighted odds ratios.

The last column in Table 1 shows homophily estimates - a measure of the extent to which participants were likely to recruit participants with a similar characteristic to themselves rather than at random [19]. Homophily values range from −1 to +1. A value of 0 represents random recruitment, negative values represent less likely to recruit from one's own group, and positive values mean more likely to recruit from one's own group. The results show that participants who were 18 to 21 years old, those who have been selling sex for less than two years, and those who grew up in urban areas were slightly more likely to recruit from their own groups than at random. FSW who earn more than fifty percent of their income from selling sex were less likely to recruit from their own group.

Table 1. Selected Sociodemographic Characteristics among FSW in Swaziland, 2011.

| n | Crude | RDS-adjusted | Homophily | |||

| Variable | Categories (n = observed participants row total) | Percent | Percent | [95% CI] | ||

| Age in years | 18–20 | 62 | 19.6 | 33.0 | [20.2,45.7] | 0.254 |

| 21–25 | 100 | 31.5 | 30.4 | [22.4,38.4] | 0.144 | |

| 26–30 | 84 | 26.5 | 22.8 | [13.8,31.7] | 0.088 | |

| >31 | 71 | 22.4 | 13.9 | [08.3,19.5] | 0.133 | |

| Number of years selling sex | Under 2 | 90 | 28.8 | 38.3 | [27.5,49.1] | 0.190 |

| 3–5 | 98 | 31.3 | 32.1 | [23.6,40.7] | 0.055 | |

| 6–10 | 82 | 26.2 | 20.2 | [13.2,27.1] | 0.087 | |

| 11 or more | 43 | 13.7 | 9.4 | [04.4,14.4] | 0.001 | |

| Education | < = Primary | 104 | 32.8 | 32.3 | [24.1,40.4] | 0.021 |

| > = Secondary | 213 | 67.2 | 67.7 | [59.6,75.8] | 0.005 | |

| Marital status | Single, never married | 278 | 88.8 | 90.6 | [86.3,94.9] | −0.132 |

| Married, cohabitate or widowed | 35 | 11.2 | 9.4 | [05.0,37.4] | −0.025 | |

| Emp. income other than SW | No | 212 | 66.9 | 73.2 | [66.3,80.0] | −0.136 |

| Yes | 105 | 33.1 | 26.8 | [19.9,33.7] | 0.171 | |

| % of total income from SW | < = 50% | 26 | 8.5 | 6.5 | [03.1,09.9] | −0.022 |

| >50% | 280 | 91.5 | 93.5 | [90.1,96.9] | −0.389 | |

| Growing up urban vs. rural | Urban | 154 | 49.0 | 45.4 | [36.4,54.3] | 0.234 |

| Rural | 149 | 47.5 | 50.4 | [41.3,59.5] | 0.052 | |

| Children | None | 77 | 24.4 | 25.9 | [18.7,33.0] | −0.026 |

| One | 97 | 30.7 | 35.6 | [27.0,44.2] | −0.085 | |

| Two | 81 | 25.6 | 24.5 | [16.2,32.8] | 0.010 | |

| Three or more | 61 | 19.3 | 14.0 | [09.2,18.9] | 0.082 | |

All data processing and analyses were conducted using Stata 12.1 [20].

Missing data

There were only three variables in the final model with missing data: whether a participant experienced symptoms of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) in the last six months (6 missing cases), whether a participant disclosed to a health care worker that she sells sex (1 missing case) and the age at which a participant started selling sex (4 missing cases). Because of the small number of cases with missing data (a combined total of 11 participants), no effort was made to impute the missing data. The eleven cases were excluded in the multivariate regression models.

Ethical Review

Informed consent was obtained from all participants in either Siswati or English depending on the choice of the participant. Given the anonymous nature of this study, verbal consent was deemed appropriate by the ethical review committees. To note consent, the interviewer initialed the consent statement after verbal consent was obtained. Participants were informed that consent could be withdrawn at any time throughout the study. The study protocol was approved by the National Ethics Committee of Swaziland and the Institutional Review Board of the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

Results

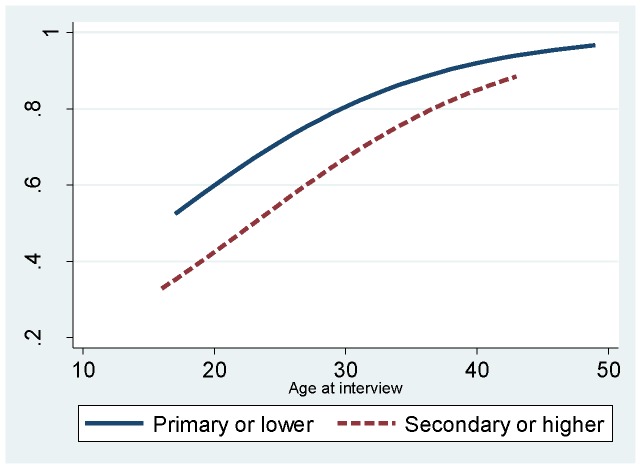

Overall, 223/317 women sampled were living with HIV for a crude prevalence of 70.3% and a RDS-adjusted estimate of 61.0% (95% CI 51.4–70.5%) which is significantly higher than reproductive age women in Swaziland across age categories (Fig. 1). The sample of FSW was predominantly from Swaziland (95.2%, n = 300/316) with a mean age of 21(median 25, results not shown). Approximately three-quarters of the FSW living with HIV were aware of their status, with about 40% receiving either antiviral therapy or co-trimoxazole prophylaxis. Those who were aware of their status as living with HIV did not have fewer partners and were no more likely to wear condoms than those not aware of their status or those who were HIV-negative. Among those who reported they had been diagnosed with HIV, 5.8% tested negative for HIV in this study. The sample was young with over three quarters of the sample being 30 years old or younger (Table 1). The majority of FSW had never been married (88.8%, n = 278/313), over 90% made more than 50% of their total income from sex work (91.5%, 280/306), and more than three-quarters reported having at least one child (75.6%, 239/316).

Figure 1. Prevalence of HIV among FSW in Swaziland by age at interview in 2011.

Just over 40% of the sample had more than 6 clients per week (41.0%, 127/310), with 41% (126/309) reporting more than 7 regular clients per month (Table 2). New clients were common, with 85.4% of the sample (258/302) reporting at least two or more new clients and over a quarter of the sample reporting more than 4 new clients in the last month. Condom use at last sex with both regular and new clients was significantly higher than always wearing condoms with clients in the previous month (p<0.01, data not shown). Nearly 90% of the sample reported at least one non-paying partner within the same time frame with lower condom use than observed in commercial sex (p<0.01, data not shown). More than one quarter (29.1%, 92/316) of the sample reported having been to jail or prison, and slightly more than 5% reported injecting drug use in the preceding 12 months.

Table 2. HIV-related risk practices among Female Sex Workers in Swaziland, 2011.

| Crude | RDS-adjusted | ||||

| Variable | Categories | n | Percent | Percent | [95% CI] |

| # of clients per week | 1–5 | 183 | 59.0 | 66.5 | [57.6,75.4] |

| 6–10 | 76 | 24.5 | 18.8 | [13.3,24.2] | |

| 11 or more | 51 | 16.5 | 14.7 | [08.3,21.2] | |

| Any sex without condom in last six months | No | 101 | 32.0 | 31.3 | [23.7,38.8] |

| Yes | 215 | 68.0 | 68.7 | [61.2,76.3] | |

| # of new clients in last 30 Days | One or less | 44 | 14.6 | 16.4 | [09.8,23.0] |

| Two | 124 | 41.1 | 43.4 | [33.3,53.5] | |

| Three | 56 | 18.5 | 15.2 | [09.6,20.9] | |

| Four | 40 | 13.2 | 13.1 | [07.0,19.2] | |

| Five | 38 | 12.6 | 11.8 | [06.0,17.6] | |

| Condom at last sex with new client | No | 37 | 12.6 | 15.2 | [07.6,22.8] |

| Yes | 257 | 87.4 | 84.8 | [77.2,92.4] | |

| Always condom use with new clients in last 30 days | Not always | 137 | 43.2 | 43.3 | [34.4,52.2] |

| Always | 180 | 56.8 | 56.7 | [47.8,65.6] | |

| # of regular clients in last 30 days | 0–1 | 26 | 8.4 | 10.0 | [01.9,18.1] |

| Two | 24 | 7.8 | 8.5 | [03.2,13.8] | |

| Three | 35 | 11.3 | 15.9 | [09.8,21.9] | |

| Four | 34 | 11.0 | 10.0 | [04.5,15.6] | |

| Five | 32 | 10.4 | 8.1 | [03.8,12.3] | |

| Six | 32 | 10.4 | 10.7 | [05.8,15.5] | |

| 7 plus | 126 | 40.8 | 36.9 | [26.4,47.3] | |

| Condom at last sex with regular client | No | 54 | 17.8 | 17.1 | [09.9,24.2] |

| Yes | 250 | 82.2 | 82.9 | [75.8,90.0] | |

| Always condom use with regular clients in last 30 days | Not always | 200 | 63.1 | 61.4 | [52.3,70.4] |

| Always | 117 | 36.9 | 38.6 | [29.5,47.7] | |

| # of non-paying partners in last 30 days | None | 37 | 11.7 | 12.5 | [04.8,20.1] |

| One | 167 | 53.0 | 50.8 | [42.9,58.7] | |

| Two | 73 | 23.2 | 23.6 | [16.8,30.3] | |

| 3 plus | 38 | 12.1 | 13.2 | [07.2,19.1] | |

| Condom at last sex with non-paying partners in last 30 days | No | 138 | 51.1 | 48.9 | [39.6,58.2] |

| Yes | 132 | 48.9 | 51.1 | [41.8,60.4] | |

| Always condom use with non-paying partners | Not always | 247 | 77.9 | 79.2 | [73.1,85.3] |

| Always | 70 | 22.1 | 20.8 | [14.7,26.9] | |

| Injected illicit drugs in last 12 months | No | 297 | 94.3 | 96.3 | [93.7,98.9] |

| Yes | 18 | 5.7 | 3.7 | [01.1,06.3] | |

| Non-injected illicit drug use in last 12 months (marijuana, powdered cocaine, and narcotics) | No | 212 | 67.9 | 78.5 | [72.4,84.5] |

| Yes | 100 | 32.1 | 21.5 | [15.5,27.5] | |

| Been to jail/prison | No | 224 | 70.9 | 81.9 | [76.5,87.2] |

| Yes | 92 | 29.1 | 18.1 | [12.8,23.5] | |

Knowledge of safe sex practices was limited; only 3 participants knew that anal sex is the highest risk form of sexual transmission, that water-based lubricants are the safest form of lubricant, and that injecting drug use is associated with HIV risk (0.9%, 3/317) (Table 3). While 86% (271/315) reported receiving information about HIV prevention in the last 12 months, approximately half the sample had received HIV prevention information specific to sex work (53.4%, 167/313), and about 10% had ever participated in any research about sex work before (12.1%, 38/313). Over 50% reported peri-anal or peri-genital symptoms consistent with an STI in the last 12 months though less than 15% reported having been diagnosed with an STI in the same timeframe.

Table 3. Knowledge of Safe Sex Practices/HIV Risk and Coverage of Prevention Services among FSW in Swaziland, 2011.

| Crude | RDS-adjusted | ||||

| Variable | Categories | n | Percent | Percent | [95% CI] |

| Knowledge that anal sex is highest risk for acquisition | No | 278 | 89.1 | 90.0 | [86.3,92.8] |

| Yes | 34 | 10.9 | 10.0 | [7.2,13.7] | |

| Safest types of lubricant to use during sex | Petroleum jelly/Vaseline | 51 | 28.5 | 30.9 | [24.2,38.5] |

| Body/fatty creams | 10 | 5.6 | 2.9 | [1.5,5.4] | |

| Water-based lubricant | 38 | 21.2 | 17.9 | [13.1,23.9] | |

| Saliva | 22 | 12.3 | 3.2 | [2.1,5.0] | |

| No lubricant use | 58 | 32.4 | 45.1 | [37.2,53.1] | |

| Knowledge about HIV acquisition risk from injecting illicit drugs | No | 12 | 3.8 | 4.4 | [2.5,7.6] |

| Yes | 302 | 96.2 | 95.6 | [92.4,97.5] | |

| All three correct | No | 314 | 99.1 | 99.9 | [99.8,100.0] |

| Yes | 3 | 0.9 | 0.1 | [0.0,0.2] | |

| Diagnosed with non-HIV STI in last 12 months | No | 259 | 85.2 | 91.2 | [88.3,93.5] |

| Yes | 45 | 14.8 | 8.8 | [6.5,11.7] | |

| Symptoms of genital or anal STI in last 12 months | No | 153 | 49.2 | 51.9 | [46.3,57.4] |

| Yes | 158 | 50.8 | 48.1 | [42.6,53.7] | |

| Tested for HIV in last 12 months | No | 82 | 25.9 | 38.3 | [32.5,44.4] |

| Yes | 234 | 74.1 | 61.7 | [55.6,67.5] | |

| Given diagnosis of HIV infection in last 12 months | No | 140 | 44.7 | 55.0 | [49.4,60.5] |

| Yes | 173 | 55.3 | 45.0 | [39.5,50.6] | |

| Access to condoms when needed | No, difficult, little access | 27 | 8.6 | 5.3 | [3.6,7.6] |

| Somewhat difficult access | 27 | 8.6 | 7.7 | [5.3,11.0] | |

| Somewhat easy access | 50 | 16.0 | 24.9 | [19.7,31.0] | |

| Very easy access | 209 | 66.8 | 62.1 | [56.2,67.8] | |

| Use of lubricants during sex | No | 245 | 78.0 | 77.9 | [72.9,82.2] |

| Yes | 69 | 22.0 | 22.1 | [17.8,27.1] | |

| Access to lubricants when needed | No Access | 21 | 22.6 | 11.7 | [7.4,18.1] |

| Difficult or little access | 27 | 29.0 | 15.8 | [10.5,23.1] | |

| Somewhat difficult access | 11 | 11.8 | 23.7 | [13.9,37.4] | |

| Somewhat easy access | 11 | 11.8 | 8.7 | [4.7,15.5] | |

| Very easy access | 23 | 24.7 | 40.1 | [28.8,52.6] | |

| Type of lubricant use during sex | No WBL | 290 | 93.5 | 96.1 | [94.0,97.5] |

| Uses WBL | 20 | 6.5 | 3.9 | [2.5,6.0] | |

| Received any information about HIV prevention in last 12 months | No | 44 | 14.0 | 15.1 | [11.4,19.7] |

| Yes | 271 | 86.0 | 84.9 | [80.3,88.6] | |

| Received information about HIV prevention for SW in last 12 months | No | 146 | 46.6 | 61.7 | [56.3,66.8] |

| Yes | 167 | 53.4 | 38.3 | [33.2,43.7] | |

| Ever participated in research about SW before | No | 275 | 87.9 | 92.0 | [89.1,94.2] |

| Yes | 38 | 12.1 | 8.0 | [5.8,10.9] | |

| Ever disclosed SW to any family member | No | 220 | 69.6 | 75.7 | [71.0,79.9] |

| Yes | 96 | 30.4 | 24.3 | [20.1,29.0] | |

| Ever disclosed SW to any health care worker | No | 234 | 74.1 | 86.6 | [83.4,89.3] |

| Yes | 82 | 25.9 | 13.4 | [10.7,16.6] | |

| Any experienced stigma (12 months) | No | 86 | 27.1 | 30.1 | [25.1,35.6] |

| Yes | 231 | 72.9 | 69.9 | [64.4,74.9] | |

| Any perceived stigma (12 months) | No | 39 | 12.3 | 13.9 | [10.3,18.4] |

| Yes | 278 | 87.7 | 86.1 | [81.6,89.7] | |

Human rights abuses were prevalent in this sample. Rape was common with nearly 40% (n = 123/314) reporting at least one rape; 17.4% (n = 23/314) reported being raped 6 or more times. Reporting blackmail (34.8%, n = 113/314) and torture (53.2%, n = 173/314) was also prevalent. Overall, 87.7% (278/317) reported perceived stigma and 72.9% (231/317) reported any experienced event of stigma. Disclosure of sex work to family (30.4%, 96/316) or health care workers (25.9%, 82/316) was reported by only a minority of participants.

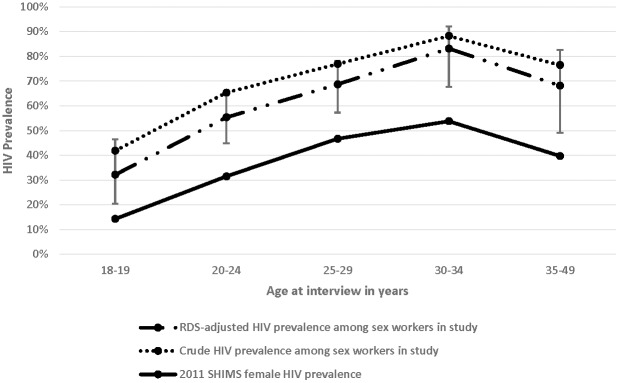

Statistically significant bivariate associations with HIV included higher age with 83.1% of the 71 women over the age 31 living with HIV (Table 4). In addition, more years selling sex, being less educated, growing up in rural areas, having more children, having been to jail or prison, having had STI symptoms, and ever disclosing sex work involvement to a health care worker were all significantly associated with HIV infection. Significant independent associations found in the multivariate regression model included older age, less education, always wearing condoms with new clients, having had symptoms consistent with an STI in the last year, and disclosing status as a sex worker to a health care worker (Fig. 2, Table 4).

Table 4. Significant bivariate and independent associations with HIV serostatus among FSW in Swaziland, 2011.

| HIV test | OR | Adjusted OR1 | |||||||

| Variable | Categories (n = observed participants total) | n | % Negative | % Positive | Pvalue | Estimate | [95% CI] | Estimate | [95% CI] |

| Age in years | 20 years or younger | 62 | 54.8 | 45.2 | <0.001 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 21–25 | 100 | 30.0 | 70.0 | 2.83** | [1.47,5.47] | 2.42* | [1.07,5.47] | ||

| 26–30 | 84 | 21.4 | 78.6 | 4.45*** | [2.16,9.17] | 3.62** | [1.39,9.43] | ||

| 31 and older | 71 | 16.9 | 83.1 | 5.97*** | [2.69,13.25] | 4.40* | [1.38,14.07] | ||

| Numbers of years selling sex | Under 2 | 90 | 44.4 | 55.6 | <0.001 | 1 | --- | ||

| 3–5 | 98 | 32.7 | 67.3 | 1.65 | [0.91,2.98] | --- | |||

| 6–10 | 82 | 18.3 | 81.7 | 3.57*** | [1.78,7.18] | --- | |||

| 11 or more | 43 | 16.3 | 83.7 | 4.11** | [1.66,10.22] | --- | |||

| Highest level of education | Primary or lower | 104 | 20.2 | 79.8 | 0.010 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Secondary or higher | 213 | 34.3 | 65.7 | 0.49* | [0.28,0.85] | 0.49* | [0.26,0.92] | ||

| Marital status | Single never married | 278 | 31.3 | 68.7 | 0.084 | 1 | |||

| Married, cohabitate or widowed | 35 | 17.1 | 82.9 | 2.20 | [0.88,5.50] | --- | |||

| Where did you grow up? | Urban | 154 | 34.4 | 65.6 | 0.016 | 1 | |||

| Rural | 149 | 22.8 | 77.2 | 1.77* | [1.07,2.95] | ||||

| # of Living Children | None | 77 | 42.9 | 57.1 | 0.012 | 1 | |||

| One | 97 | 28.9 | 71.1 | 1.85 | [0.98,3.47] | --- | |||

| Two | 81 | 25.9 | 74.1 | 2.14* | [1.10,4.19] | ||||

| Three or more | 61 | 18.0 | 82.0 | 3.41** | [1.54,7.54] | ||||

| Always uses condom with new clients | Not always | 137 | 24.1 | 75.9 | 0.058 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Always | 180 | 33.9 | 66.1 | 0.62 | [0.38,1.02] | 0.50 | [0.27,0.94] | ||

| Always uses condom regular clients | Not always | 200 | 30.0 | 70.0 | 0.860 | 1 | |||

| Always | 117 | 29.1 | 70.9 | 1.05 | [0.63,1.73] | --- | |||

| Always uses condom non- paying partner | Not always | 247 | 29.1 | 70.9 | 0.713 | 1 | |||

| Always | 70 | 31.4 | 68.6 | 0.90 | [0.51,1.59] | --- | |||

| Been to Jail or Prison | No | 224 | 34.4 | 65.6 | 0.005 | 1 | |||

| Yes | 92 | 18.5 | 81.5 | 2.31** | [1.28,4.19] | --- | |||

| Diagnosed with STI in last 12 mts. | No | 259 | 33.2 | 66.8 | 0.007 | 1 | |||

| Yes | 45 | 13.3 | 86.7 | 3.23* | [1.32,7.93] | --- | |||

| Had STI-symptoms in last 12 mts. | No | 153 | 38.6 | 61.4 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Yes | 158 | 21.5 | 78.5 | 0.001 | 2.29** | [1.39,3.77] | 2.80*** | [1.56,5.02] | |

| Tested for HIV in last 12 mts. | No | 82 | 40.2 | 59.8 | 1 | ||||

| Yes | 234 | 25.6 | 74.4 | 0.013 | 1.95* | [1.15,3.32] | --- | ||

| Diagnosed with HIV | No | 140 | 58.6 | 41.4 | 1 | ||||

| Yes | 173 | 5.8 | 94.2 | <0.001 | 23.04*** | [11.2,47.42] | |||

| Received any HIV prevention info in last 12 mts. | No | 44 | 40.9 | 59.1 | 0.084 | 1 | |||

| Yes | 271 | 28.0 | 72.0 | 1.78 | [0.92,3.43] | — | |||

| Ever disclosed SW to any family member | No | 220 | 30.9 | 69.1 | 0.494 | 1 | |||

| Yes | 96 | 27.1 | 72.9 | 1.20 | [0.71,2.05] | — | |||

| Ever disclosed SW to any health care worker | No | 234 | 33.3 | 66.7 | 0.018 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Yes | 82 | 19.5 | 80.5 | 2.06* | [1.12,3.80] | 2.22* | [1.09,4.50] | ||

Note: Exponentiated coefficients; 95% confidence intervals in brackets.

Adjusted for age, education, always using condoms with new clients, STI symptoms in the last 12 months, and ever disclosing sex work to any health care worker.

*p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001.

Figure 2. Predicted probabilities of being HIV positive from a crude logistic regression model, by education level, adjusted for age at interview among FSW in Swaziland, 2011.

Discussion

Swaziland has been long recognized as a country with among the highest relative HIV burden in the world [21]. Because there is sustained transmission in the general population with average acquisition and transmission risks, the role of key populations with specific acquisition and transmissions risks such as sex workers has been assumed to be minimal [22]. However, Fig. 1 demonstrates that even in the context of a generalized epidemic, there is a concentrated epidemic among FSW. Few women in this study had any occupation outside of sex work, and even among those who did, the majority of their income was derived from sex work. Thus, these women represent a distinct population from other women who may report occasional transactional sex. While the prevalence of HIV among FSW is high, it is consistent with the few data points available characterizing the burden of HIV in other Southern African countries [7]

The relative contribution or population attributable fraction of sex workers to generalized HIV epidemics is characterized based on two primary components [23], [24]. The first is related to the size of the sexual networks of these women. The second is related to acquisition and transmission risk associated with each sexual act; an outcome of condom usage, type of sexual act, presence of genital or anal ulcerative diseases, and the viral load of the person living with HIV having sex [25]–[28]. Overall, in this sample, sexual networks were large across both commercial and non-paying partners. While periodicity of sexual acts was not measured, assessments of number of partners highlighted that most women had multiple new clients each month, existing or regular clients, and non-paying partners. Further, there were significantly different levels of condom use between partner types with the highest among new clients and lowest among non-paying partners. Always wearing condoms was independently associated with 50% lower odds of living with HIV among FSW, suggesting that in the context of a population with high testing rates and relatively good awareness of HIV-status, the risk may come from new clients where status is unknown. Study participants were less likely to report always wearing condoms as compared to wearing condoms at last sex across partner types, suggesting that always wearing condoms may be a more representative measure of actual condom use. Lastly, even when condoms were used, petroleum-based lubricants were often used which can cause breakdown of the available latex condoms or no lubricant was used, likely associated with the high rates of breakage and slippage of condoms reported by participants (data not shown). While the distribution of condom-compatible lubricants has focused on men who have sex with men, anal sex as a common practice as well as high numbers of partners suggest that this commodity is equally important for FSW.

The burden of HIV in this sample of sex workers is high though no CD4 testing was done to assess eligibility for treatment. Thus, while it is not possible to know the antiretroviral treatment (ART) eligibility of the 60% of FSW in this sample who are not on ART, it is likely that their community viral load was high. Approximately a third of women reported anal sex in the last month in this study with about a tenth of women knowing that this was a high risk act for sexual transmission of HIV (data not shown). A recent review demonstrated that transmission rates in penile-anal sex are approximately 18 times higher than that of penile-vaginal intercourse irrespective of gender [29]. Moreover, reporting symptoms of a peri-anal or peri-genital STI was both common and independently associated with HIV infection in this study. Given large sexual networks, high prevalence of HIV, limited condom usage, and a likely high per-act transmission rate of HIV, the population attributable fraction of HIV among FSW in the widespread epidemic of Swaziland is likely significant.

While most participants were exposed to some form of HIV prevention information in the previous year, most of this was from the media. However, only about half of the women reported access to HIV prevention programs specifically for sex workers and few reported participating in a research project related to sex work before. In addition, disclosure of sex work status to both health care workers and family was uncommon. There are providers of education and safe HIV testing services for sex workers in Swaziland, but these data suggest that coverage remains limited. Limited coverage is likely due to both suboptimal levels of the provision of services but also limited uptake of services because of fear related to inadvertent disclosure of sex work status. Criminalization of sex work across Africa including in Swaziland may impede FSW access to health services [30]. These results highlight the need to address both the quantity and quality of service provision by increasing the clinical and cultural competence in addressing the health care needs of sex workers in a rights-affirming manner [31], [32].

The interpretation of these data reported here appear to somewhat contrast with those of the 2009 Swaziland MoT study. To date, there were limited quantitative inputs for the MoT study including the size and density of sexual networks of FSW, the burden of HIV, sexual practices, and population size. Additionally, the existing MoT studies do not dynamically assess relative contribution of sex work given the limited ability to fully characterize chains of HIV transmission among these women and clusters of infection. Advanced methods of MoT such as those suggested by Mishra et al in this collection may better characterize the actual contribution of sex workers and their clients to generalized HIV epidemics.

There are several limitations to the methods used in this study. Causality of the associations with HIV cannot be firmly established using cross-sectional data. The use of RDS increases the external validity of the findings by adjusting for network size, homophily, and by limiting accrual by any one participant [15]. However, RDS is not probability sampling as there is no sampling frame from which to accrue participants, which limits the generalizability of findings [33]. To be conservative, we presented the crude and weighted analyses for prevalence estimates but used unweighted data for bivariate and multivariate modeling [34]. However, we also completed sensitivity analyses by comparing these results to those results obtained when using weighted results in the modeling and found little difference. Swaziland is geographically a small country, and seed participants were accrued in different regions of the country. However, the site was in a central location in the country, and the majority of the participants were from one of the two large urban centers in the country, which may overestimate the levels of service access and education levels for sex workers in the country.

Conclusions

The 2011 Swaziland HIV Incidence Measurement Survey (SHIMS) demonstrated 54.5% HIV prevalence among women in Swaziland with equal to or greater than two sexual partners in the previous 6 months and 43.2% among those who were not married and ever had sex [35]. While our study only measured prevalence among FSW, the demographic characteristics of the highest risk women in the SHIMS survey matches that of the FSW sampled for this study. While there are not population size data available for FSW or their male clients in Swaziland, the speed and ease of accrual of 328 participants suggests that there is a sizable population of FSW in the country though this should be confirmed with appropriate methods. Moreover, the population attributable fraction of the total HIV epidemic in the country attributable to sex work has likely been underestimated. While Swaziland has a highly generalized HIV epidemic, reconceptualizing the needs of key populations such as FSW suggests that these women represent a distinct population with specific vulnerabilities and a high burden of HIV compared to other women. These women are understudied and underserved resulting in a limited characterization of their HIV prevention, treatment, and care needs and only sparse specific and competent programming. FSW are an important population for further investigation and rapid scale-up of combination HIV prevention including biomedical, behavioral, and structural interventions.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the female sex workers that participated in this study with little personal benefit and potential harm. We would like to acknowledge Rebecca Fielding-Miller for her leadership in the implementation of this project, and Virginia Tedrow, and Mark Berry for their additional support. We would also like to acknowledge Edward Okoth and Babazile Dlamini of Population Services International/Swaziland for their direction in operationalizing study activities. We thank all the members of the Swaziland Most-at-Risk Populations (MARPS) technical working group, the Swaziland Ministry of Health, and other Swazi government agencies that provided valuable guidance and helped ensure the success of this study. From USAID in Swaziland, Jennifer Albertini, and Natalie Kruse-Levy provided significant technical input to this project. Alison Cheng and Sarah Sandison from USAID in Washington provided oversight and technical assistance for the project.

Funding Statement

The USAID | Project SEARCH, Task Order No. 2, is funded by the U.S. Agency for International Development under Contract No. GHH-I-00-07-00032-00, beginning September 30, 2008, and supported by the President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief. The Research to Prevention (R2P) Project is led by the Johns Hopkins Center for Global Health and managed by the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health Center for Communication Programs (CCP). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.UNAIDS, NERCHA, Swaziland Ministry of Health, UNICEF (2010) Monitoring the Declaration of the Commitment on HIV and AIDS (UNGASS): Swaziland Country Report Mbanane: UNGASS. http://www.unaids.org/en/dataanalysis/knowyourresponse/countryprogressreports/2010countries/swaziland_2010_country_progress_report_en.pdf Last accessed: 8 May 2014.

- 2.UNAIDS (2012) Report on the Global AIDS Epidemic. Geneva: UN. http://www.unaids.org/en/media/unaids/contentassets/documents/epidemiology/2012/gr2012/20121120_unaids_global_report_2012_with_annexes_en.pdf Last accessed: 22 May 2014.

- 3.Swaziland National Emergency Response Council on HIV/AIDS (2009) Swaziland: HIV Prevention Response and Modes of Transmission Analysis. Mbabane, Swaziland: World Bank. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/3046/483580SR0P1113101same0box101PUBLIC1.pdf?sequence=1 Last accessed: 8 May 2014.

- 4.Reed JB, Justman J, Bicego G, Donnell D, Bock N, et al. Estimating national HIV incidence from directly observed seroconversions in the Swaziland HIV Incidence Measurement Survey (SHIMS) longitudinal cohort (FRLBX02); 2012; Washington, D.C. http://pag.aids2012.org/Abstracts.aspx?AID=21447 Last accessed: 8 May 2014.

- 5.Swaziland Ministry of Health (2012) Swaziland HIV Incidence Measurement Survey (SHIMS) First Findings Report. Swaziland: ICAP. https://www.k4health.org/sites/default/files/SHIMS_Report.pdf Last accessed: 22 May 2014

- 6. Ngugi EN, Roth E, Mastin T, Nderitu MG, Yasmin S (2012) Female sex workers in Africa: epidemiology overview, data gaps, ways forward. SAHARA J 9:148–153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Baral S, Beyrer C, Muessig K, Poteat T, Wirtz AL, et al. (2012) Burden of HIV among female sex workers in low-income and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infectious Diseases 12:538–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Weiser SD, Leiter K, Bangsberg DR, Butler LM, Percy-de KF, et al. (2007) Food insufficiency is associated with high-risk sexual behavior among women in Botswana and Swaziland. PLoS Medicine 4:1589–1597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Macro International Inc., Swaziland Central Statistical Office (2008) Swaziland: Demographic and Health Survey 2006–2007. Mbabane, Swaziland: USAID. http://catalog.ihsn.org/index.php/catalog/2463 Last accessed: 8 May 2014.

- 10.UNFPA, UNAIDS, Swaziland Ministry of Health and Social Welfare, Swaziland National Emergency Response Council on HIV/AIDS (2007) Situation analysis on commercial sex work in Swaziland. November-December 2007. Mbabana, Swaziland: UNFPA. http://www.infocenter.nercha.org.sz/sites/default/files/SDComSexSitAnalysis.pdf Last accessed: 8 May 2014.

- 11.Arnott J, Crago AL (2009) Rights not Rescure: A Report on Female, Male, And Trans Sex Workers' Human Rights in Botswana, Nambiia, and South Africa. New York City, USA: OSI. http://www.opensocietyfoundations.org/sites/default/files/summary_20081114.pdf Last accessed: 8 May 2014.

- 12. Scorgie F, Nakato D, Harper E, Richter M, Maseko S, et al. (2013) ‘We are despised in the hospitals’: sex workers' experiences of accessing health care in four African countries. Culture, Health & Sexuality 15:450–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tanser F, de Oliveira T, Maheu-Giroux M, Barnighausen T (2014) Concentrated HIV subepidemics in generalized epidemic settings. Current Opinion in HIV and AIDS 9 (2):115–125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Yam EA, Mnisi Z, Sithole B, Kennedy C, Kerrigan DL, et al. (2013) Association between condom use and use of other contraceptive methods among female sex workers in Swaziland: a relationship-level analysis of condom and contraceptive use. Sexually Transmitted Diseases 40:406–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Heckathorn DD (1997) Respondent-driven sampling: a new approach to the study of hidden populations. Social Problems 44:174–199. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Baral S, Logie CH, Grosso A, Wirtz AL, Beyrer C (2013) Modified social ecological model: a tool to guide the assessment of the risks and risk contexts of HIV epidemics. BMC Public Health 13:482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Schonlau M, Liebau E (2012) Respondent-driven sampling. The Stata Journal 12:21. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Johnston L, O'Bra H, Chopra M, Mathews C, Townsend L, et al. (2010) The associations of voluntary counseling and testing acceptance and the perceived likelihood of being HIV-infected among men with multiple sex partners in a South African township. AIDS and Behavior 14:922–931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Heckathorn D, Semaan S, Broadhead R, Hughes J (2002) Extensions of respondent-driven sampling: a new approach to the study of injection drug users aged 18–25. AIDS and Behavior 6:55–67. [Google Scholar]

- 20.StataCorp (2010) Stata Statistical Software: Release 11.1. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP. http://www.stata.com/Last accessed: 22 May 2014.

- 21. Wright J, Walley J, Philip A, Petros H, Ford H (2010) Research into practice: 10 years of international public health partnership between the UK and Swaziland. Journal of Public Health 32:277–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Semugoma P, Beyrer C, Baral S (2012) Assessing the effects of anti-homosexuality legislation in Uganda on HIV prevention, treatment, and care services. SAHARA J 9:173–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Schwartlander B, Stover J, Hallett T, Atun R, Avila C, et al. (2011) Towards an improved investment approach for an effective response to HIV/AIDS. Lancet 377:2031–2041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kerrigan D, Wirtz A, Baral S, Decker MR, Murray L, et al. (2012) The Global HIV Epidemics among Sex Workers. Washington, DC:. doi: 10.1596/978-0-8213-9774-9 doi: 10.1596/978-0-8213-9774-9. http://www.worldbank.org/content/dam/Worldbank/document/GlobalHIVEpidemicsAmongSexWorkers.pdf Last accessed: 8 May 2014.

- 25.Anglemyer A, Rutherford GW, Horvath T, Baggaley RC, Egger M, et al. (2013) Antiretroviral therapy for prevention of HIV transmission in HIV-discordant couples. Cochrane database of systematic reviews 4: CD009153. http://apps.who.int/rhl/reviews/CD009153.pdf Last accessed: 8 May 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26. Baggaley RF, Fraser C (2010) Modelling sexual transmission of HIV: testing the assumptions, validating the predictions. Current Opinion in HIV and AIDS 5:269–276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Baggaley RF, White RG, Boily MC (2010) HIV transmission risk through anal intercourse: systematic review, meta-analysis and implications for HIV prevention. International Journal of Epidemiology 39:1048–1063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Baggaley RF, White RG, Boily MC (2008) Systematic review of orogenital HIV-1 transmission probabilities. International Journal of Epidemiology 37:1255–1265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Baggaley RF, White RG, Boily MC (2010) HIV transmission risk through anal intercourse: systematic review, meta-analysis and implications for HIV prevention. International Journal of Epidemiology 39(4):1048–1063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Chersich MF, Luchters S, Ntaganira I, Gerbase A, Lo YR, et al. (2013) Priority interventions to reduce HIV transmission in sex work settings in sub-Saharan Africa and delivery of these services. Journal of the International AIDS Society 16:17980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Beyrer C, Baral S, Kerrigan D, El-Bassel N, Bekker LG, et al. (2011) Expanding the space: inclusion of most-at-risk populations in HIV prevention, treatment, and care services. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes 57 Suppl 2S96–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Mtetwa S, Busza J, Chidiya S, Mungofa S, Cowan F (2013) "You are wasting our drugs": health service barriers to HIV treatment for sex workers in Zimbabwe. BMC Public Health 13:698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. McCreesh N, Frost SD, Seeley J, Katongole J, Tarsh MN, et al. (2012) Evaluation of respondent-driven sampling. Epidemiology 23:138–147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Salganik MJ (2012) Commentary: Respondent-driven Sampling in the Real World. Epidemiology 23:148–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Bicego GT, Nkambule R, Peterson I, Reed J, Donnell D, et al. (2013) Recent Patterns in Population-Based HIV Prevalence in Swaziland. PLoS One 8:e77101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]