Abstract

Tritrichomonas foetus is a serious veterinary pathogen, causing bovine trichomoniasis, a sexually transmitted disease leading to infertility and abortion. T. foetus infects the mucosal surfaces of the reproductive tract. Infection with T. foetus leads to apoptotic cell death of bovine vaginal epithelial cells (BVECs) in culture. An affinity-purified cysteine protease (CP) fraction yielding on sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis a single band with an apparent molecular mass of 30 kDa (CP30) also induces BVEC apoptosis. Treatment of CP30 with the protease inhibitors TLCK (Nα-p-tosyl-l-lysine chloromethyl ketone) and E-64 [l-trans-epoxysuccinyl-leucylamide-(4-guanido)-butane] greatly reduces induction of BVEC apoptosis. Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time-of-flight MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry analysis of CP30 reveals a single peak with a molecular mass of 23.7 kDa. Mass spectral peptide sequence analysis of proteolytically digested CP30 reveals homologies to a previously reported cDNA clone, CP8 (D. J. Mallinson, J. Livingstone, K. M. Appleton, S. J. Lees, G. H. Coombs, and M. J. North, Microbiology 141:3077-3085, 1995). Induction of apoptosis is highly species specific, since the related human parasite Trichomonas vaginalis and associated purified CPs did not induce BVEC death. Fluorescence microscopy along with the Cell Death Detection ELISAPLUS assay and flow cytometry analyses were used to detect apoptotic nuclear condensation, DNA fragmentation, and changes in plasma membrane asymmetry in host cells undergoing apoptosis in response to T. foetus infection or incubation with CP30. Additionally, the activation of caspase-3 and inhibition of cell death by caspase inhibitors indicates that caspases are involved in BVEC apoptosis. These results imply that apoptosis is involved in the pathogenesis of T. foetus infection in vivo, which may have important implications for therapeutic interference with host cell death that could alter the course of the pathology in vivo.

The protozoan parasite Tritrichomonas foetus causes a major sexually transmitted disease in cattle, trichomoniasis. Bovine trichomoniasis causes considerable economic loss in the United States, Canada, and South America, as well as in other parts of the world where open range management and natural breeding are practiced (3, 8, 10, 11, 15, 48). The disease is characterized by chronic genital tract infection with inflammation and reproductive failure (3, 11, 15). The parasites initially adhere to and infect the vagina, causing vaginitis, and then move to the uterus and oviduct. Endometriosis and catarrh may result in transient or permanent infertility. Infection proceeds slowly, without interfering with either fertilization or early development of the fetus, but with time the infection may overtake the developing fetus, resulting in abortion and sterility (3, 11, 15). The mechanisms by which parasites cause these alterations are not fully understood. Although the symptomology and consequences of T. foetus infections are well known, the mechanisms of parasite infection remain to be established.

It has been suggested that soluble cytotoxins (perhaps cysteine proteases [CPs]), which are released from parasites, play a role in the pathogenic effects on host cells and infection (6, 31, 36, 38, 42, 46). With reference to trichomonads, it has been suggested that they play roles as virulence factors (5, 6, 26, 27, 34, 46) and as adherence factors (2, 13, 31), and it has been suggested that CPs contribute to pathogenesis when released into the host mucosal surface (8, 45, 48). A role in evasion of the host immune response (14, 20, 32, 37) has also been suggested. However, the effects of these proteases on natural host cells have not been examined.

Recently, we established bovine vaginal epithelial cell (BVEC) and human vaginal epithelial cell (HVEC) culture systems which display host-parasite specificity (18, 43). That is, T. foetus damages BVECs but not HVECs, and Trichomonas vaginalis damages only HVECs (18, 43). T. foetus infection of BVECs in vitro results in cell detachment followed by cell destruction and death. Cytopathogenicity is a function of parasite density.

Cytotoxicity does not indicate a specific cellular death mechanism. Cell death can occur by either of two distinct mechanisms, necrosis or apoptosis. Apoptosis is an important and well-regulated form of cell death that occurs under a variety of physiological and pathological conditions (9). Microbes have developed mechanisms to stimulate the host cell apoptotic signal transduction cascade, which likely play a role in pathogenesis (33). Apoptotic cell death has been studied in detail as a response to several bacterial and viral infections (50), but relatively little is known regarding apoptotic cell death as a response to parasitic infections. There are only a few published reports which show that apoptosis occurs in response to infection with parasitic pathogens, i.e., Acanthamoeba histolytica (1), Plasmodium falciparum (7), Trypanosoma cruzi (25), Cryptosporidium parvum (29), and Entamoeba histolytica (19, 38). Although damage to host cells leading to cell death due to infection by these parasites has been reported, the complete mechanisms of cell death have not been elucidated. Several lines of evidence indicate that CPs are essential for E. histolytica-induced pathology, where CPs destroy host tissue (38).

Recently, we reported the cytopathogenic effects of T. foetus on BVECs (43). Addition of live parasites to BVEC cultures leads to destruction of the host cells within a matter of hours. At that time we did not know the mechanism of parasite-induced BVEC cytotoxicity. Since CPs have been shown to be involved in microbial pathogenesis, including that of trichomonads, we decided to examine the possible roles of CPs in induction of trichomonad pathology. In this report we demonstrate that host cells infected with T. foetus die through the induction of apoptosis and, furthermore, that a CP with an approximate molecular mass of 30 kDa (CP30) purified from parasite conditioned medium also induces BVEC apoptosis. CP30 appears to be homologous to one of the T. foetus CP clones reported in Gen Bank, CP8 (accession no. X87781) (26)

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Parasites.

T. foetus (strain D1, obtained from L. Corbeil [University of California, San Diego]) was grown in Diamond's medium (pH 7.2) as previously described (43). Parasites were harvested in late log phase (24 h) by centrifugation and washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (pH 7.2). The trichomonads were suspended in Williams medium for experimental purposes as previously described (18, 43).

T. foetus SF.

T. foetus soluble fraction (SF) was prepared as follows: parasites were grown as described above, harvested, washed in PBS, resuspended in trichomonad incubation buffer (TIB) (PBS with 10 mM HEPES and 0.05% l-ascorbic acid [pH 7.2]), and incubated at 37°C for 2.5 h as reported earlier (44, 46). This represents a modification from earlier procedures (44, 46), in which l-cysteine was included in TIB. Preparations were used only when >95% parasites were motile after incubation. The suspension was centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 15 min, and the supernatant was filtered sequentially through 0.45- and 0.2-μm-pore-size filters, followed by additional centrifugation for 2 h at 200,000 × g. The soluble fraction (devoid of membrane debris) was lyophilized and resuspended in a known volume of William's medium.

Purification of CP30 from SF.

SF was concentrated by centrifugal filtration (Centricon Plus-20; 5,000-molecular-weight cutoff). Active components in SF were purified by bacitracin affinity chromatography according to methods reported earlier (35, 46), except that Affi-Gel 10 (Bio-Rad) was used as the support matrix. Concentrated SF in TIB was diluted (1:3) with sodium acetate buffer (20 mM, pH 4.0) and applied to a column (1 by 30 cm) of the affinity matrix equilibrated in sodium acetate buffer at a flow rate of 0.3 ml/min. The column was washed (0.8 ml/min.) with 20 mM sodium acetate buffer until the A280 read zero. Material bound to the column was eluted (0.6 ml/min.) with 0.1 M Tris-HCl (pH 7.0)-1.0 M NaCl-25% 2-propanol as described by Thomford et al. (46). The peak (A280) was collected and dialyzed for 2 h against water. The protein was concentrated by using a centrifugal filtration device (Centricon Plus-20; 5,000-molecular-weight cutoff). Preparations typically yielded 1.1 to 1.5 mg of protein per 4 liters of parasite culture (∼5 × 1010 parasites). For control experiments T. vaginalis CP30 was isolated and purified in the same way, except that it was further purified by Bio-Gel P-60 chromatography (unpublished data).

Purified CP30 was subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) analysis on 12% polyacrylamide gels, using a 3% stacking gel as described by to Laemmli (21). In addition, CP30 was analyzed by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time-of-flight (MALDI-TOF) mass spectrometry (MS). One microliter (∼5 μg) of sample was diluted with water to 40 μl and desalted by drop dialysis (41). One microliter of 2,5-dihydroxybenzoic acid (9 mg/ml)-5-methoxysalicylic acid (1 mg/ml) in acetonitrile-water-trifluoroacetic acid (50:50:1) and 1 μl of the dialyzed sample were mixed on a Bruker Anchorchip target. The data were acquired with a Bruker Reflex IV MALDI-TOF instrument, with irradiation from a nitrogen laser (337 nm). The mass scale was calibrated with bovine serum albumin and myoglobin. Interpretation was done with XTOF 5.1.1 (Bruker).

For peptide sequencing, CP30 was reduced with dithiothreitol (DTT), alkylated with iodoacetamide, and digested overnight with trypsin (trypsin/protein ratio of 1:100), endo-Glu-C (1:300), or endo-Asp-N (1:300). The samples were purified on C18 ZipTips column (Millipore). Sequencing was performed by using electrospray ionization (ESI)-MS. For electrospray, the samples were sequenced with an Applied Biosystems Sciex Qstar Pulsari quadrupole orthogonal TOF MS. Sequence alignment was performed with the Accelerys software package.

CP assays.

CP activity was assayed essentially as described by Thomford et al. (46), using Z-RR-AMC (n-carbobenzoxyl-arginyl-arginyl-7-amido-4-methylcoumarin) as the substrate. Briefly, 10-μl aliquots were added to 980 μl of 0.5 M Tris-HCl-0.15 M NaCl-5 mM DTT (pH 7.6) and 10 μl of Z-RR-AMC (1 mg/ml in dimethyl sulfoxide; 15 μM final concentration) and left for the indicated times or were continuously monitored at an excitation wavelength of 380 nm and an emission wavelength of 450 nm. Specific conditions are indicated in the relevant figure legends.

Culture of host cells.

BVECs were cultured as reported earlier (43). Host cells were maintained at 37°C in an atmosphere of 5% CO2 in William's complete medium (18, 43). Once cells were approaching confluence, contaminating fibroblasts were removed by differential trypsinization (18, 43). Once the purity of the cells had been established, epithelial cells were subcultured in 96-, 48-, 24-, or 6-well plates. In some experiments, the cells were also cultured on a glass coverslip (Fisher Scientific) placed in a six-well plate or a glass eight-chamber slide containing Williams medium. All experiments were performed when cells were 70 to 80% confluent and proliferating.

When included as control cells, HVECs were cultured similarly, as described previously (18).

When BVECs were prepared for flow cytometry assays, they were subjected to trypsinization by treatment with 0.5% trypsin-5.3 mM EDTA for 3 min at 37°C. The trypsin was inactivated by addition of Williams medium, cells were collected by centrifugation at 200 × g, and the pellet was washed with cold PBS and prepared for each procedure as described below.

Cytotoxicity and induction of apoptotic cell death of host cells.

BVECs were exposed to trichomonad parasites, SF, or CP30 for 4 to 20 h at 37°C. In control experiments, parasites or SF was omitted. In other experiments, BVECs were treated with an SF preparation obtained from the human parasite T. vaginalis or with an SF from Pentatrichomonas hominis, a noninfectious pentatrichomonad. The CellTiter 96 AQueous assay (Promega Corp., Madison, Wis.) was used to measure cytotoxicity and viability of host cells. Cytotoxicity is calculated as 1 − E/C, where E/C is the ratio of the absorbances of formazan at 490 nm for experimental (E) versus control (C) samples. In some cases, the WST-1 assay (Boehringer-Mannheim Corp.) was used to measure cytotoxicity and viability of BVECs, according to the manufacturer's instructions. Data were expressed as the mean absorbance value derived from quadruplicate samples in three separate experiments.

In some experiments protease inhibitors such as aprotinin (Sigma) (0.3 to 1.2 μg/ml), leupeptin (Sigma) (0.3 to 1.2 μg/ml), phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (Sigma) (0.6 to 100 μg/ml), TLCK (Nα-p-tosyl-l-lysine chloromethyl ketone) (Calbiochem) (50 to 200 μg/ml), and E-64 [l-trans-epoxysuccinyl-leucylamide-(4-guanido)-butane] (Calbiochem) (50 to 100 μg/ml) were added to wells containing BVECs immediately before the start of the experiments. At the end of the incubation period, the wells were washed and cytotoxicity was measured as described above. Also, in some experiments CP30 was pretreated with E-64 at room temperature for 30 min in order to achieve maximum inhibition.

Apoptosis assays.

Various methods, described below, were employed to evaluate BVEC apoptosis. Camptothecin (Fluka) (10 μg/ml) was used to induce apoptosis as a positive control.

(i) DNA fragmentation.

Two different methods were used to examine DNA fragmentation: (a) quantification of DNA fragments by an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and (b) examination of morphological characteristics that appear upon cell death, such as appearance of nuclear fragmentation and segregation of chromatin into dense masses, as judged by staining with a DNA binding dye.

(a) Cell Death Detection ELISAPLUS.

Apoptotic cell death in BVECs was evaluated by ELISA (Cell Death Detection ELISAPLUS; Boehringer Mannheim/Roche) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The enrichment of mono- and oligonucleosomes released into the cytoplasm is calculated as the ratio of the absorbance of the sample cells to the absorbance of control cells. The enrichment factor was used as a parameter of apoptosis (4) and is shown on the y axis as the mean ± standard deviation from triplicate experiments performed in quadruplicate. An enrichment factor of 1 represents background or spontaneous apoptosis (generally about 8 to 15%). BVECs were grown in 48- or 24-well plates and exposed to parasites, SF, CP30, or camptothecin for 8 to 12 h. The supernatant was collected and centrifuged, and the pellet was washed with PBS. The cell pellet and the remaining washed cells in wells were lysed and added to microtiter plates as described in the ELISA kit. The supernatant was not used when BVECs were infected with parasites, because it would contain parasites along with dead BVECs.

(b) DNA binding dye.

BVECs on a glass coverslip were formalin fixed and stained with bisbenzamide dye (Hoechst 33258) as described previously (29). After staining, the coverslip was washed, mounted on a glass slide, and observed under a fluorescence microscope with excitation at 360 nm.

(ii) Plasma membrane asymmetry.

Plasma membrane asymmetry was measured by using an Annexin V-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) apoptosis detection kit (BD PharMingen). BVECs were collected following treatment with CP30 or SF in a six-well plate; three wells of untreated cells and three wells of treated cells were collected individually. Washed cells were resuspended in the binding buffer, stained with both Annexin V-FITC and propidium iodide (PI) according to the manufacturer's protocol, and analyzed by flow cytometry. The FACStar plus flow cytometer was set for FL 1 (Annexin) versus FL 2 (PI) bivariate analysis. Data from 10,000 cells/sample were collected. The quadrants were set based on the population of healthy, unstained cells in untreated samples. CellQuest analysis of the data revealed the percentage of the cells in the respective quadrants.

(iii) Caspase involvement.

The involvement of caspases in BVEC apoptosis was assessed by the incubation of BVECs with the apoptosis inhibitors Z-VAD-FMK or Q-VD(Ome)-Oph (Enzyme Systems Product, Inc.). The inhibitors (70 to 100 μM final concentration) were added and left for 45 min prior to addition of CP30. Control BVECs received only dimethyl sulfoxide. Cytotoxicity and apoptosis were evaluated by the WST-1 and ELISAPLUS assays, respectively.

Anti-ACTIVE caspase-3 polyclonal antibody (Promega Corp.) was employed to detect the active form of caspase-3 in apoptotic BVECs according to the manufacturer's instructions. BVECs cultured on an eight-chamber glass slide were exposed to parasites, SF, CP30, or camptothecin; washed after incubation; and fixed with buffered formalin. Cells were incubated with anti-ACTIVE caspase-3 polyclonal antibody, followed by washing and incubation with secondary fluorescein-labeled goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G antibody (Kirkegaard & Perry Laboratories) (1:250) and the DNA binding dye DAPI (4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole). Cells were observed under a fluorescence microscope.

In addition, activated caspase-3 in CP30-treated and untreated BVECs was assayed fluorometrically by using Ac-DEVD-AFC (Bio-Rad) as the substrate. BVEC lysates were incubated with the substrates in cell lysis buffer as recommended by the manufacturer.

Statistical analysis.

For experiments yielding quantitative results, groups were compared by one-way analysis of variance. Differences, when exposed, were further investigated by use of the Student-Neuman-Keuls post hoc test. Alpha was set at 0.05. Results are expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean throughout.

RESULTS

T. foetus SF is cytotoxic to BVECs.

SF prepared as described by Singh et al. (44) is cytotoxic to BVECs (data not shown), as reported earlier for live T. foetus (43). The presence of protease activity in SF was demonstrated following SDS-PAGE on 12% acrylamide gels copolymerized with 0.2% gelatin as described (12, 22) (data not shown). A series of protease inhibitors were tested for their effect on SF-induced BVEC cytotoxicity. The serine protease inhibitors aprotinin, leupeptin, and phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride had no effect. However, TLCK and E-64 inhibited the cytotoxic activity present in SF (data not shown). These results suggest that a CP(s) present in SF is the cytotoxic agent(s), as E-64 is a specific CP inhibitor and TLCK inhibits both serine proteases and CPs. In addition, SF cytotoxicity required the presence of a reducing agent, with a concentration of approximately 10 mM cysteine yielding maximal activity (data not shown). Together these results strongly imply that the active component(s) of SF is a CP.

Purification of a cytotoxic CP from SF.

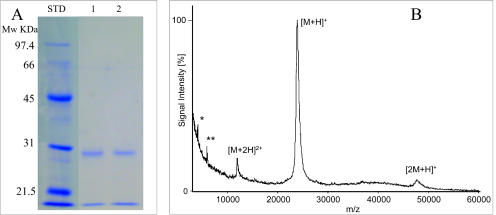

The purification of the active SF component(s) was initiated by using bacitracin affinity chromatography as reported for CPs (35, 46). The vast majority of the material absorbing at 280 nm in SF did not bind to the bacitracin affinity column (data not shown) and contained no cytotoxic activity. The bound material was eluted as described in Materials and Methods. SDS-PAGE analysis of the bacitracin-bound fraction revealed a single Coomassie blue-positive band at a molecular mass of ca. 30 kDa (Fig. 1A). The purification resulted in a 12- to 15-fold increase in specific activity as determined with the WST-1 cytotoxicity assay. A sample of the purified fraction was analyzed by MALDI-TOF MS. A major symmetrical peak with a molecular mass of 23.7 kDa was observed (Fig. 1B). In addition to the (M + H)+ peak, low-abundance peaks, corresponding to the dimer (2M + H)+ and the doubly charged monomer (M + 2H)2+ were observed, confirming the molecular mass.

FIG. 1.

Analysis of affinity-purified CP30. (A) The concentrated protein (7 μg) was analyzed by SDS-PAGE on 12% polyacrylamide gels. The results from two preparations are shown. (B) MALDI-TOF MS of CP30. CP30 was prepared in the presence of TLCK to eliminate autolysis observed during sample preparation for MS. The mass values for the (M + H)+, the (M + 2H)2+, and the (2 M + H)+ ion signals were found at m/z 23736, 11899, and 47499, respectively. The signals marked * and ** at m/z 4127 and 5955 probably originate from minor contaminants.

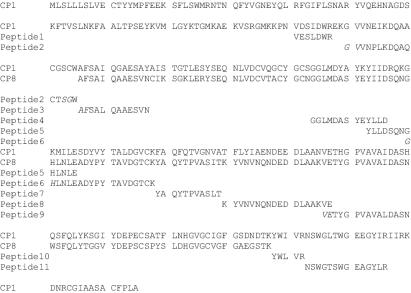

A number of peptides derived from CP30 were sequenced by ESI MS-MS, as described in Materials and Methods. Alignment of the peptides with a previously cloned T. foetus CP (CP8, accession no. X87781) reported by Mallinson et al. (26) is shown in Fig. 2. Over 90 amino acids align exactly with CP8, with 77 in a row showing exact homology. It should be noted that the reported CP8 is not a full-length clone, with probably 25 to 40% of the sequence missing, based on the MALDI-TOF molecular mass.

FIG. 2.

Sequence alignment of CP30 peptides. CP30 peptides were obtained by enzymatic digestion and analyzed by ESI MS-MS, as described in Materials and Methods. The sequence alignments were determined by using the Accelerys sequence analysis package. CP8 is one of the CPs cloned by Mallinson et al. (26). CP1, derived from a full-length cDNA clone for a T. foetus CP (accession number U13153), is shown for alignment of peptides lying outside the CP8 sequence (46). In several places, our alignment programs automatically place an L, which cannot be discriminated from I because their molecular weights are identical. It is almost a certainty that I is the correct identity.

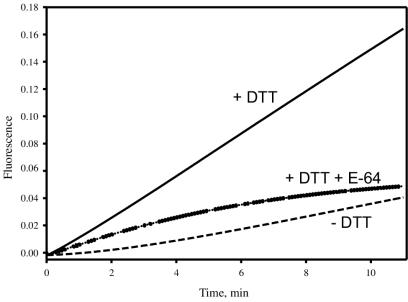

The purified protein has CP activity as demonstrated by assays with synthetic substrates, e.g., Bz-FVR-NA and Z-RR-AMC. Protease activity required the presence of reducing agents such as cysteine (data not shown) or DTT and was inhibited by E-64 (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Proteolytic activity of purified CP30. CP30 (1 μg) was incubated with Z-RR-AMC in the absence (dotted line) or presence (solid line) of DTT at 20°C or in the presence of DTT and E-64 (20 μg/ml) (dashed line). Fluorescence was monitored continuously as described in Materials and Methods.

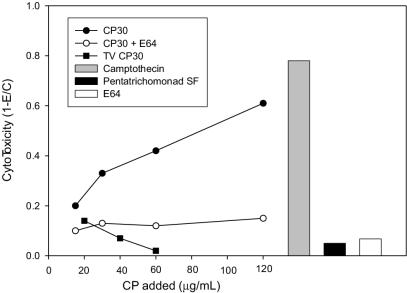

BVECs were destroyed by incubation with CP30 in a dose-dependent manner and the cytotoxicity was inhibited by E-64 (Fig. 4). CP30 from the human parasite T. vaginalis and an SF fraction obtained from the noninfectious pentatrichomonad P. hominis showed no cytotoxicity toward BVECs. It was confirmed that P. hominis SF contains CP activity by directly assaying an aliquot with Z-RR-AMC (data not shown).

FIG. 4.

Cytotoxicity of purified CP30. BVECs were incubated for 15 h at 37°C with various concentrations of CP30, CP30 pretreated with E64 (100 μg/ml), or T. vaginalis CP30. Cytotoxicity was measured by using the WST-1 cell proliferation reagent. In addition, the cytotoxic effects of camptothecin (10 μg/ml), P. hominis SF (25 μg), and E64 were measured. Experiments were performed in quadruplicate and repeated twice.

T. foetus, SF, and CP30 induce BVEC apoptosis.

Having shown that T. foetus, SF, and CP30 are cytotoxic to BVECs, we investigated whether the host cell death is the result of apoptosis. Because BVECs are not as well characterized as other, more established mammalian cultured cells, we employed a variety of methods to assay for BVEC apoptosis. These included DNA fragmentation (bisbenzamide staining and Cell Death Detection ELISAPLUS), alteration in plasma membrane asymmetry (Annexin V-FITC), changes in mitochondrial membrane potential (Mitocapture), detection of active caspase-3, and the use of caspase inhibitors. Not all of the assays are shown here, but the results of each of them were totally consistent with the same conclusion: coincubation of BVECs with T. foetus, SF, or CP30 induces BVEC apoptosis. Although the data shown here are limited to CP30, each of the assays was performed with live parasites with the same results.

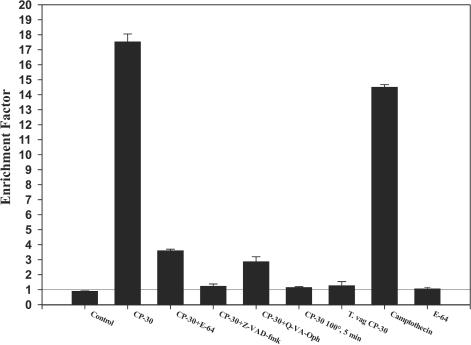

The Cell Death Detection ELISAPLUS was used to quantify DNA fragmentation in apoptotic cells, based on the detection of mono- and oligonucleosomes in the cytoplasmic fractions of cell lysates. As shown in Fig. 5, incubation of BVECs with CP30 caused significant apoptosis. In fact, the level of apoptosis was similar to that found with camptothecin, an apoptosis inducer used as a positive control. However, there was no increase above background in BVECs incubated with CP30 obtained from the human pathogen T. vaginalis. These results are consistent with our previous observations regarding species specificity. Similar results were observed when BVECs were treated with T. foetus and SF. Heat-treated CP30 did not induce cell death.

FIG. 5.

Quantification of nucleosomal DNA fragmentation. The Cell Death Detection ELISAPLUS was used to quantify DNA fragmentation in BVECs undergoing apoptosis in the presence of CP30 (24 μg), CP30 treated at 100°C for 5 min, camptothecin (10 μg/ml), and CP30 in the presence of caspase inhibitors (100 μg/ml). Cell were grown in 48-well plates and incubated for 12 h. As a control, BVECs were treated with CP30 plus E64 (100 μg/ml), E64 (100 μg/ml), or T. vaginalis CP30 (25 μg). The rate of apoptosis is reflected by the enrichment of nucleosomes in the cytoplasm shown on the y axis; an enrichment factor of 1, indicated by a line, is equivalent to background apoptosis. Experiments were performed in triplicate and repeated three times.

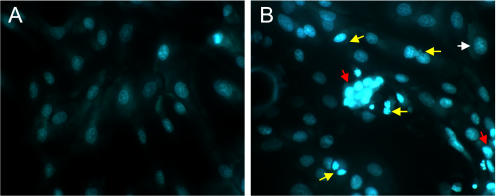

The DNA binding dye bisbenzamide binds to normal and condensed chromatin; the resulting patterns in the nuclei of intact cells can be visualized by fluorescence microscopy. BVECs incubated with CP30 showed cell and nuclear shrinkage with chromatin condensation, nuclear fragmentation, and segregation of chromatin into dense masses when examined with bisbenzamide (Fig. 6). Untreated cells displayed intact, regularly shaped nuclei and a normal chromatin distribution.

FIG. 6.

Fluorescence microscopy of BVECs stained with DNA binding dye. Fluorescence microscopic images of normal BVECs (A) and BVECs undergoing apoptosis (B) in the presence of CP30 (15 μg, 6 h) are shown. Cells were stained with bisbenzamide (Hoechst 33258) as described in Materials and Methods. In panel B, the white arrow indicates normal cells, yellow arrows indicate cells undergoing apoptosis, and red arrows indicate apoptotic cells with chromatin condensation. Magnification, ×40.

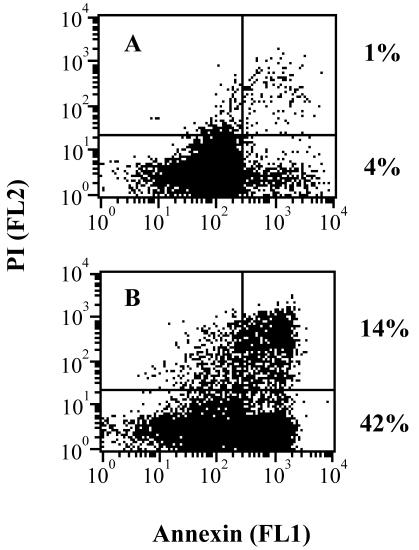

Most cell types undergoing apoptosis translocate phosphatidyl serine from the inner face of the plasma membrane to the cell surface (28, 47), where it can be detected by staining with Annexin V-FITC. Flow cytometry analyses of CP30-treated BVECs showed a significant increase in the Annexin-positive cell population (Fig. 7). Cells undergoing apoptosis showed Annexin+ PI+ and Annexin+ PI− cell populations. Thus, total apoptosis is represented by the two right quadrants and increases from 5 to 56% in response to CP30. Similar results were observed when BVECs were treated with SF.

FIG. 7.

Flow cytometry analysis of Annexin V-FITC staining. Representative dot plots of untreated BVECs (A) and CP30 (100 μg/ml, 6 h)-treated BVECs (B) show a significant increase in the Annexin V-positive apoptotic cell population (lower right quadrant). The upper right quadrant represents apoptotic or necrotic cells positive for both Annexin and PI. Data from 104 cells per sample were collected.

One of the earlier intracellular events to occur following induction of apoptosis is the disruption of the mitochondrial membrane potential (40). The shift in mitochondrial membrane potential in BVECs treated with SF or CP30 was quantified by flow cytometry analysis (data not shown). There was at least a fourfold increase in green fluorescence, indicating that the dye does not accumulate in the mitochondria. The JC-1 dye was also used to confirm changes in mitochondrial membrane potential by fluorescence with live parasites, SF, CP30, and camptothecin (data not shown).

CP30-induced activation of caspase-3.

Apoptosis is mediated by caspases (39, 49). To demonstrate that activation of caspases is involved in BVEC death, the effect of caspase inhibitors on CP-30-induced cell death was investigated by using the ELISAPLUS and WST-1 cytotoxicity assays. As shown in Fig. 5, CP30-induced BVEC death was significantly blocked when BVECs were preincubated with either Z-VAD-FMK or Q-VD(Ome)-Oph (Enzyme Systems Product, Inc.), which are general caspase inhibitors. Similar results were observed when intact parasites were incubated with host cells. In addition, BVECs incubated with the caspase inhibitors remained attached to the wells and showed normal morphology when visualized under the microscope. Furthermore, caspase-3, the ultimate caspase in the apoptotic cascade, was also activated during incubation of BVECs with CP30. Caspase-3 activation was determined by using anti-ACTIVE antibody and by direct enzymatic measurement of caspase-3, as described in Materials and Methods (data not shown). These data clearly indicate that CP30 induces activation of BVEC caspases, in particular caspase-3, resulting in apoptosis.

DISCUSSION

Our study is the first to demonstrate that in vitro infection with T. foetus induces apoptotic cell death in normal BVECs. Our recent development of in vitro culture systems for HVECs and BVECs allows us to study the infection mechanisms of T. foetus and T. vaginalis and host-parasite specificity in detail at the cellular and molecular levels (18, 43). We previously showed that coincubation of T. foetus parasites with BVECs resulted in host cell cytotoxicity in a species-specific manner. In the present study, we extended our observations to demonstrate that a CP (CP30) elaborated by T. foetus into TIB (SF) induces apoptosis in BVECs.

The evidence that CP30 is a CP is based on direct enzymatic assays with synthetic substrates, the requirement for a reducing agent in the assays, and inhibition by a specific CP inhibitor, E-64. CP30 induces apoptosis in BVECs but not HVECs. The ability to induce apoptosis is closely coupled to CP activity, as it, too, is inhibited by E-64 and requires a reducing agent for full activity.

In addition to the direct enzymological data, peptide sequence analysis reveals strong homologies to a previously reported CP, CP8 (26). The sequence alignments shown in Fig. 2 show a nearly perfect match to CP8, with two peptides falling outside the reported CP8 sequence. In addition, two of the peptides are homologous to peptides reported by Thomford et al. (46). Mallinson et al. (26, 27) cloned CPs from T. foetus and T. vaginalis based on homologies to highly conserved sequences in the broader family of mammalian CPs. They reported up to seven species of CP from T. foetus and four species from T. vaginalis. Two additional CPs from T. vaginalis are reported in GenBank. Most of the trichomonad CP clones reported in the literature are not full-length, and therefore a direct comparison with CP30 is limited. Our data suggest, however, that the purified CP30 represents the naturally expressed protein product of CP8.

During the past decade or so, there has been considerable interest in parasite CPs and their role in the infection process (42). McLaughlin and Müller (30) first reported CPs from T. foetus in 1979, and Lockwood et al. and others studied a number of secreted proteases from both T. vaginalis and T. foetus (16, 17, 22-24).

The data described here clearly demonstrate that CP30 from T. foetus is cytotoxic to BVECs and that the toxicity is due to the induction of apoptosis. Furthermore, the induction of apoptosis is correlated with protease activity, as the specific CP inhibitor E-64 inhibits both apoptosis and protease activity. BVEC apoptosis due to CP30 is a specific event: a purified CP and the SF from T. vaginalis, the human parasite, do not induce BVEC apoptosis, nor does the routine handling of the cell cultures, including treatment with trypsin. Conversely, T. foetus CP30 does not induce apoptosis in HVECs. Although proteases are generally thought of as broad-spectrum enzymes, there are many examples of highly specific proteases, e.g., the blood clotting factors and the caspases. The mechanism by which CP30 induces BVEC apoptosis remains to be established.

The present findings offer compelling evidence that apoptosis contributes to trichomonad-mediated cytopathic effects. Moreover, the morphological changes characteristic of apoptosis are evident in cells exposed to either live parasites or CP30. The expression of distinctly recognized morphological features of apoptosis, including changes in mitochondrial potential and plasma membrane asymmetry (distinct from necrosis), cell shrinkage, and chromatin condensation were observed following parasite invasion or exposure to CP30. These classical cytoarchitectural modifications, in conjunction with induction of DNA fragmentation, represent definitive hallmarks of apoptotic cell death in BVECs during infection. In addition, detection of caspase-3 activation and inhibition of BVEC apoptosis by caspase inhibitors clearly suggest the involvement of caspases in CP30-induced cell death. These observations alone suggest possible mechanisms of the induction of apoptosis in BVECs for future study. Recently, Huston et al. (19) demonstrated apoptotic killing of host cells by E. histolytica, which involved activation of caspase-3.

The biological relevance of BVEC apoptosis in the response to parasite infection is not known. Induction of apoptosis, rather than necrosis, may benefit the parasites by limiting the host inflammatory response, which could be detrimental to the survival of the parasite. Apoptotic cells are removed by phagocytes before they undergo lysis and spilling of cell contents, which may generate an inflammatory response. On the other hand, deletion of infected BVECs by apoptosis may benefit the host, since it allows maintenance of epithelial cell barrier integrity.

The results presented here clearly demonstrate that T. foetus parasites and a purified CP secreted by the parasites induce apoptosis in cells derived from the bovine reproductive tract. This is the first report to demonstrate apoptosis in BVECs and therefore will open up new lines of investigation into the mechanism of parasite infection. Furthermore, developments of rational new treatments or a vaccine for bovine trichomoniasis depend upon the understanding of the basic infection process and the role of specific parasite molecule such as CP30.

Acknowledgments

We thank John Longo for flow cytometry analyses, Bryant Carruth and Charles Mango for technical assistance in some of the cell death studies, and Robert H. BonDurant (University of California, Davis) for providing us the P. hominis culture. We are grateful to Suzanne Klaessig, Department of Population Medicine and Diagnostic Sciences, College of Veterinary Medicine, Cornell University, Ithaca, N.Y., for culturing all of the cells. We also thank Barbara H. Nevaldine for assisting in preparation of fluorescence microscopic slides.

The Boston University School of Medicine Mass Spectrometry Resource is supported by NIH/NCRR grants P41-RR10888 and S10 RR015942 (to C.E.C.). This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant AI47334, USDA grant 97-2615, a SUNY Upstate Medical University intramural research grant, and the Women's Health Fund, SUNY Upstate Medical Foundation (to B.N.S.).

Editor: J. F. Urban, Jr.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alizadeh, H., M. S. Pidherney, J. P. McCulley, and J. Y. Niederkorn. 1994. Apoptosis as a mechanism of cytolysis of tumor cells by a pathogenic free-living amoeba. Infect. Immun. 62:1298-1303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alvarez-Sanchez, M. E., L. Avila-Gonzalez, C. Becerril-Garcia, L. V. Fattel-Facenda, J. Ortega-Lopez, and R. Arroyo. 2000. A novel cysteine proteinase (CP65) of Trichomonas vaginalis involved in cytotoxicity. Microb. Pathog. 28:193-202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson, M. L., R. H. BonDurant, R. R. Corbeil, and L. B. Corbeil. 1996. Immune and inflammatory responses to reproductive tract infection with Tritrichomonas foetus in immunized and control heifers. J. Parasitol. 82:594-600. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aragane, Y., D. Kulms, D. Metze, G. Wilkes, B. Poppelmann, T. A. Luger, and T. Schwarz. 1998. Ultraviolet light induces apoptosis via direct activation of CD95 (FAS/APO-1) independently of its ligand CD95L. J. Cell Biol. 140:171-182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arroyo, R., and J. F. Alderete. Trichomonas vaginalis surface proteinase activity is necessary for parasite adherence to epithelial cells. Infect. Immun. 57:2991-2997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Arroyo, R., and J. F. Alderete. 1995. Two Trichomonas vaginalis surface proteinases bind to host epithelial cells and are related to levels of cytoadherence and cytotoxicity. Arch. Med. Res. 26:279-285. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Balde, A., J. L. Sarthou, G. Aribot, P. Michel, J. F. Trape, C. Rogier, and C. Roussilhon. 1996. Plasmodium falciparum induces apoptosis in human mononuclear cells. Infect. Immun. 64:744-750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bastida-Corcuera, F., J. E. Butler, H. Heyermann, J. W. Thomford, and L. B Corbeil. 2000. Tritrichomonas foetus extracellular cysteine proteinase cleavage of bovine IgG2 allotypes. J. Parasitol. 86:328-332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bellanny, C. O. C., R. D. G. Malcomson, D. J. Harrison, and A. H. Wyllie. 1995. Cell death in health and disease: the biology and regulation of apoptosis. Cancer Biol. 6:3-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.BonDurant, R. H., and B. M. Honigberg. 1994. Trichomonads of veterinary importance, p. 111-188. In J. N. Krieger (ed.), Parasitic protozoa, vol. 9. Academic Press, New York, N.Y. [Google Scholar]

- 11.BonDurant, R. H. 1997. Pathogenesis, diagnosis and management of trichomoniasis in cattle. Vet. Clin. N. Am. Food Anim. Pract. 13:345-361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coombs, G. H., and M. J. North. 1983. An analysis of Trichomonas vaginalis by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Parasitology 86:1-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Crouch, M. L., and J. F. Alderete. 1999. Trichomonas vaginalis interactions with fibronectin and laminin. Microbiology 145:2835-2843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Draper, D., W. Donohoe, L. Mortimer, and R. P. Heine. 1998. Cysteine proteases of Trichomonas vaginalis degrade secretory leucocyte protease inhibitor. J. Infect. Dis. 178:815-819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Felleisen, R. S. J. 1999. Host-parasite interaction in bovine infection with Tritrichomonas foetus. Microb. Infect. 1:807-816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garber, G. E., and L. T. Lemchuk-Favel. 1989. Characterization and purification of extracellular proteases of Trichomonas vaginalis. Can. J. Microbiol. 35:903-909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Garber, G. E., and L. T. Lemchuk-Favel. 1994. Analysis of the extracellular proteases of Trichomonas vaginalis. Parasitol. Res. 80:361-365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gilbert, R. O., G. Elia, D. H. Beach, S. Klaessig, and B. N. Singh. 2000. Cytopathogenic effect of Trichomonas vaginalis on human vaginal epithelial cells cultured in vitro. Infect. Immun. 68:4200-4206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huston, C. D., E. R. Houpt, B. J. Mann, C. S. Hahn, and W. A. Petri. 2000. Caspase-3-dependent killing of host cells by the parasite Entamoeba histolytica. Cell Microbiol. 2:617-625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kania, S. A., S. L. Reed, J. W. Thomford, R. H. BonDurant, K. Hirata, R. R. Corbeil, M. J. North, and L. B. Corbeil. 2001. Degradation of bovine complement C3 by trichomonad extracellular proteinase. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 78:83-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Laemmli, U. K. 1970. Cleavage of structural proteins during assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 227:680-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lockwood, B. C., K. I. Scott, A. F. Bremner, and G. H. Coombs. 1987. The use of highly sensitive electrophoretic methods to compare the proteinases of trichomonads. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 24:89-95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lockwood, B. C., M. J. North, and G. H. Coombs. 1984. Trichomonas vaginalis, Tritrichomonas foetus, and Trichomonas batrachorum: comparative proteolytic activity. Exp. Parasitol. 58:245-253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lockwood, B. C., M. J. North, and G. H. Coombs. 1988. The release of hydrolases from Trichomonas vaginalis and Tritrichomonas foetus. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 24:89-95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lopes, M. F., V. F. da Veiga, A. R. Santos, M. E. Fonseca, and G. A. DosReis. 1995. Activation-induced CD4+ T cell death by apoptosis in experimental Chagas' disease. J. Immunol. 154:744-752. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mallinson, D. J., J. Livingstone, K. M. Appleton, S. J. Lees, G. H. Coombs, and M. J. North. 1995. Multiple cysteine proteinases of the pathogenic protozoon Tritrichomonas foetus: identification of seven diverse and differentially expressed genes. Microbiology 141:3077-3085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mallinson, D. J., B. C. Lockwood, G. H. Coombs, and M. J. North. 1994. Identification and molecular cloning of four cysteine proteinase genes from the pathogenic protozoon Trichomonas vaginalis. Microbiology 140:2725-2735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Martin, S. J., C. P. M. Reutelingsperger, A. J. McGahon, J. A. Rader, C. A. A. van Schie, D. M. LaFace, and D. R. Green. 1995. Early redistribution of plasma membrane phosphatidylserine is a general feature of apoptosis regardless of the initiating stimulus: inhibitory over expression of Bcl-2 and Ab1. J. Exp. Med. 182:1545-1556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McCole, D. F., L. Eckmann, F. Laurent, and M. F. Kagnoff. 2000. Intestinal epithelial cell apoptosis following Cryptosporidium parvum infection. Infect. Immun. 68:1710-1713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McLaughlin, J., and M. Müller. 1979. Purification and molecular characterization of a low molecular weight thiol proteinase from the flagellate protozoon Tritrichomonas foetus. J. Biol. Chem. 254:1526-1533. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mendoza-Lopez, M. R., C. Becerril-Garcia, L. V. Fattel-Facenda, L. Avila-Gonzalez, M. E. Rutz-Tachiquin, J. Ortega-Lopez, and R. Arroyo. 2000. CP30, a cysteine proteinase involved in Trichomonas vaginalis cytoadherence. Infect. Immun. 68:4907-4912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Min, D. Y., K. H. Hyun, J. S. Ryu, M. H. Ahn, and M. H. Cho. 1998. Degradation of human immunoglobins and hemoglobin by 60 kDa cysteine proteinase of Trichomonas vaginalis. Korean J. Parasitol. 36:361-368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moss, J. E., A. O. Aliprantis, and A. Zychlinsky. 1999. The regulation of apoptosis by microbial pathogens. Int. Rev. Cytol. 187:203-259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Neale, K. A., and J. F. Alderete. 1990. Analysis of the proteinases of representative Trichomonas vaginalis isolates. Infect. Immun. 58:157-162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.North, M. J. 1994. Cysteine endopeptidases of parasitic protozoa. Methods Enzymol. 244:523-539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Petrin, D., K. Degaty, R. Bhatt, and G. Garber. 1998. Clinical and microbiological aspects of Trichomonas vaginalis. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 11:300-317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Prevenzano, D., and J. F. Alderete. 1995. Analysis of human immunoglobulin-degrading cysteine proteinases of Trichomonas vaginalis. Infect. Immun. 63:3388-3395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Que, X., and S. L. Reed. 2000. Cysteine proteinases and the pathogenesis of amebiosis. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 13:196-206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Reed, J. C. 2001. Apoptosis-regulating proteins as targets for drug discovery. Trends Mol. Med. 7:314-319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Reers, M., S. T. Smiley, C. Mottola-Hartshorn, A. Chen, M. Lin, and L. B. Chen. 1995. Mitochondrial membrane potential monitored by JC-1 dye. Methods Enzymol. 260:406-417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rouse, J. C., and J. E. Vath. 1996. On-the-probe sample cleanup strategies for glycoprotein-released carbohydrates prior to matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry. Anal. Biochem. 238:82-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sajid, M., and J. H. McKerrow. 2002. Cysteine proteases of parasitic organisms. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 120:1-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Singh, B. N., J. J. Lucas, D. H. Beach, S. T. Shin, and R. O. Gilbert. 1999. Adhesion of Tritrichomonas foetus to bovine vaginal epithelial cells. Infect. Immun. 67:3847-3854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Singh, B. N., R. H. BonDurant, C. M. Campero, and L. B. Corbeil. 2000. Immunological and biochemical analysis of glycosylated surface antigens and lipophosphoglycan of Tritrichomonas foetus. J. Parasitol. 87:770-777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Talbot, J. A., K. Neilsen, and L. B. Corbeil. 1991. Cleavage of proteins of reproductive secretions by extracellular proteinases of Tritrichomonas foetus. Can. J. Microbiol. 37:384-390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Thomford, J. W., J. A. Talbot, J. S. Ikeda, and L. B. Corbeil. 1996. Characterization of extracellular proteinases of Tritrichomonas foetus. J. Parasitol. 82:112-117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.van Engeland, M., F. C. S. Ramaekers, B. Schutte, and C. P. M. Reutelingsperger. 1996. A novel assay to measure loss of plasma membrane asymmetry during apoptosis of adherent cells in culture. Cytometry 24:131-139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Youle, A., S. Z. Skirrow, and R. H. BonDurant. 1989. Bovine trichomoniasis. Parasitol. Today 5:373-377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zheng, T. S., S. F. Schlosser, T. Dao, R. Hingorani, I. N. Crispe, J. L. Boyer, and R. A. Flavell. 1998. Caspase-3 controls both cytoplasmic and nuclear events associated with Fas-mediated apoptosis in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:13618-13623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zychlinsky, A., and P. J. Sansonetti. 1997. Host/pathogen interactions apoptosis in bacterial pathogenesis. J. Clin. Investig. 100:493-496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]