Abstract

Burkholderia cenocepacia (formerly Burkholderia cepacia complex genomovar III) causes chronic lung infections in patients with cystic fibrosis. In this work, we used a modified signature-tagged mutagenesis (STM) strategy for the isolation of B. cenocepacia mutants that cannot survive in vivo. Thirty-seven specialized plasposons, each carrying a unique oligonucleotide tag signature, were constructed and used to examine the survival of 2,627 B. cenocepacia transposon mutants, arranged in pools of 37 unique mutants, after a 10-day lung infection in rats by using the agar bead model. The recovered mutants were screened by real-time PCR, resulting in the identification of 260 mutants which presumably did not survive within the lungs. These mutants were repooled into smaller pools, and the infections were repeated. After a second screen, we isolated 102 mutants unable to survive in the rat model. The location of the transposon in each of these mutants was mapped within the B. cenocepacia chromosomes. We identified mutations in genes involved in cellular metabolism, global regulation, DNA replication and repair, and those encoding bacterial surface structures, including transmembrane proteins and cell surface polysaccharides. Also, we found 18 genes of unknown function, which are conserved in other bacteria. A subset of 12 representative mutants that were individually examined using the rat model in competition with the wild-type strain displayed reduced survival, confirming the predictive value of our STM screen. This study provides a blueprint to investigate at the molecular level the basis for survival and persistence of B. cenocepacia within the airways.

Isolates of the Burkholderia cepacia complex are gram-negative opportunistic pathogens. Usually harmless while surviving in the soil, these bacteria can cause devastating infections in patients with cystic fibrosis (CF) and chronic granulomatous disease (3, 23, 24, 30, 31). Pseudomonas aeruginosa is the predominant respiratory pathogen in CF patients (23), but the disease risk for infection with B. cepacia complex in patients with CF is substantially higher than with P. aeruginosa alone or with other bacteria (13). Although the clinical outcome among CF patients infected with B. cepacia complex varies greatly, infections in some patients result in a rapidly progressive and fatal bacteremic disease (30). Furthermore, isolates of the B. cepacia complex have the potential for patient-to-patient spread, both within and outside the hospital (22, 32, 41, 51, 52). Recent taxonomic studies demonstrated that strains identified as B. cepacia comprise a complex of closely related species or genomovars, collectively called the B. cepacia complex (43, 67). This complex consists of at least nine species sharing a high degree of 16S rDNA and recA sequence similarity and moderate levels of DNA-DNA hybridization (for a recent review, see reference 10). Strains of each of the species within the B. cepacia complex have been isolated from CF patients; however, some are more common than others. Burkholderia multivorans (formerly genomovar II) and Burkholderia cenocepacia (formerly genomovar III) isolates comprise about 10 and 83%, respectively, of all B. cepacia complex isolated from CF patients in Canada (62).

Isolates of the B. cepacia complex are inherently resistant to many antimicrobial agents (49, 54, 55). The widespread antibiotic resistance of these microorganisms has proven extremely problematic for the treatment of infections. Furthermore, the lack of sensitivity to antibiotics commonly used for genetic selection complicates genetic studies in this pathogen by drastically limiting the choice of antibiotic resistance gene markers for mutagenesis and complementation experiments (38).

Several bacterial factors may play a role in the infections caused by isolates of the B. cepacia complex. Some isolates have the ability to survive intracellularly within eukaryotic cells such as macrophages, respiratory epithelial cells, and amoebae (6, 34, 44, 46, 56). Other potential virulence factors that have been described include cable pili (57), flagella (65), a type III secretion system (50, 64), surface exopolysaccharide (7, 9), production of melanin (71), catalase (37), up to four types of iron-chelating siderophores (16), proteases and other secreted enzymes (12, 29, 47, 68), quorum-sensing systems (40, 42), and the ability to form biofilms (66). Not all strains produce each of the proposed virulence factors and, to date, none of these individual factors has been clearly demonstrated to be a major contributor to human disease.

Signature-tagged mutagenesis (STM) was originally developed to facilitate the detection of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium genes required for in vivo survival (28). STM has since been applied to several different bacteria and fungal pathogens (for a recent review, see reference 48). STM is a comparative hybridization technique that employs a collection of transposons, each modified by the incorporation of a unique DNA sequence tag (28). These transposons are introduced into the pathogen to be studied and, following random transposition, insertional mutants are isolated. Mutants containing a transposon insertion in a gene which codes for a function required for in vivo growth or survival will fail to pass through the in vivo selection. Individual mutants can be distinguished from each other based on unique tags carried by the transposon insertions of each strain. By comparing the tags present in the input pool of mutants initially inoculated into the animal model with those unique tags present in the bacteria recovered after infection, it is possible to identify mutants that fail to grow exclusively in vivo. Subsequently, the DNA sequence surrounding the insertion can be analyzed to identify the gene or genes required for virulence. Traditional STM involves using randomly generated tags that can be detected by conventional hybridization techniques (28), which may result in cross-hybridization signals and high background, increasing the proportion of false positives (53). This was a significant concern in the case of B. cenocepacia due to the high moles percent G+C content of the genome. A PCR-based modification of STM can potentially eliminate pitfalls inherent to hybridization and increase the specificity during the PCR screening step (39).

In this study, we describe a modified STM procedure to isolate and identify candidate genes of B. cenocepacia required for the in vivo survival in 102 transposon mutants that could not be recovered from intratracheal lung infections in rats. The modifications to the STM strategy included the use of a real-time PCR-based screening step for the detection of each transposon mutant within a pool. In addition, we used a plasposon backbone instead of a classical transposon to facilitate the identification of flanking chromosomal regions once the element is integrated onto the chromosome, since the transposable element within the plasposon contains an Escherichia coli plasmid replication origin (18). Inherent problems of STM such as cross-amplifying tags were removed prior to preparing the pools for the in vivo passage, thereby making these modifications useful as a general screening method to identify genes required for survival in vivo.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

Unless otherwise indicated, all strains were grown at 37°C. B. cenocepacia strain K56-2 (16) was grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium. This strain is a CF isolate that belongs to the same clonal group as the strain J2315, whose genome has recently been sequenced (http://www.sanger.ac.uk/Projects/B_cenocepacia/), and it was previously shown to cause a chronic lung infection in the agar bead rat model (61). E. coli DH5α [F− φ80 lacZΔM15 endA1 recA1 hsdR17(rK− mK+) supE44 thi-1 ΔgyrA96 (ΔlacZYA-argF)U169 relA1] was used as a host for the plasposon constructs and for the helper plasmid pRK2013 (see below). Transposon mutants were grown in Typticase soy agar, Vogel-Bonner minimal medium (VBM) (69), or LB medium as required, all of which were supplemented with trimethoprim at a final concentration of 100 μg/ml. E. coli strains were grown in LB medium supplemented with 50 μg of trimethoprim/ml or 40 μg of kanamycin/ml, as appropriate. All chemicals were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo., unless otherwise indicated.

Construction of a library of plasposons carrying unique oligonucleotide tags.

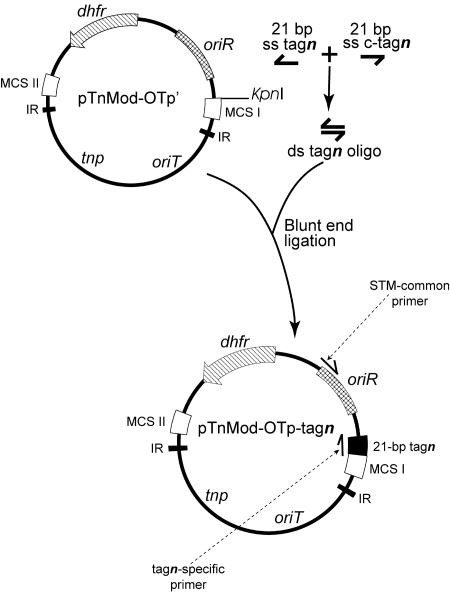

Forty-one plasposons (designated pTnMod-OTp-tag1 to pTnMod-OTp-tag41) were constructed as depicted in Fig. 1. The plasposon backbone was from pTnMod-OTp′ (18). Forty-one different oligonucleotides of 21 bp (Table 1) were annealed to complementary molecules to yield double-stranded oligonucleotides. The ends of the double-stranded oligonucleotides were phosphorylated and separately ligated into the blunted KpnI site of pTnMod-OTp′ to produce 41 different plasposons pTnMod-OTp-tagn, where n is the oligonucleotide tag number 1 to 41. Ligations were verified by PCR using each of the 21-bp oligonucleotides (Table 1) as one primer and primer STM-common (5′-TCGATTTCGTTCCACTGAGCG-3′) as the second primer. PCR amplifications were performed in a PTC-0200 DNA engine (MJ Research, Incline Village, Nev.) by using Taq polymerase (Roche Diagnostics, Laval, Quebec, Canada). The 811-bp product was amplified as follows: 7 min at 95°C, two cycles of 95°C for 1 min, 65°C for 2 s (followed by decreases of 0.2°C per second up to 55°C), and 72°C for 1 min; and then 10 cycles of 95°C for 1 min, 55°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 1 min. The product was visualized on a 0.7% (wt/vol) agarose gel.

FIG. 1.

Construction of the tag plasposons. The transposons pTnMod-OTp-tagn were constructed using the backbone of pTnMod-OTp′ by digesting this plasposon at the unique KpnI site and blunting the ends. The KpnI site was chosen because it is located in one of the two multiple cloning sites (MCS) within the inverted repeats (IR) and therefore within the transposable element portion of the plasposon. The 21-bp tag oligonucleotides (tagn) were separately annealed to the complementary sequences (c-tagn), and the ends were phosphorylated. The double-stranded oligonucleotides were separately blunt-end ligated into the blunted KpnI site to yield the plasposons pTnMod-OTp-tagn. This procedure was followed for each of the 41 tags. oriR is the E. coli origin of replication, dhfr is the trimethoprim resistance cassette, tnp is the transposase, and oriT is the origin of transfer. Arrows in pTnMod-OTp-tagn denote the location of the STM common primer (STM-common) and the tagn-specific primers used for PCR amplifications. ds, double stranded; ss, single stranded.

TABLE 1.

Nucleotide sequences of tags for STM

| Tag no. | Sequencea |

|---|---|

| tag1 | 5′-GTACCGCGCTTAAACGTTCAG-3′ |

| tag2 | 5′-GTACCGCGCTTAAATAGCCTG-3′ |

| tag3 | 5′-GTACCGCGCTTAAAAGTCTCG-3′ |

| tag4 | 5′-GTACCGCGCTTAATAACGTGG-3′ |

| tag5 | 5′-GTACCGCGCTTAAACTGGTAG-3′ |

| tag6 | 5′-GTACCGCGCTTAAGCATGTTG-3′ |

| tag7 | 5′-GTACCGCGCTTAATGTAACCG-3′ |

| tag8 | 5′-GTACCGCGCTTAAAATCTCGG-3′ |

| tag9 | 5′-GTACCGCGCTTAATAGGCAAG-3′ |

| tag10 | 5′-GTACCGCGCTTAACAATCGTG-3′ |

| tag11 | 5′-GTACCGCGCTTAATCAAGACG-3′ |

| tag12 | 5′-GTACCGCGCTTAACTAGTAGG-3′ |

| tag13b | 5′-GTACCGCGCTTAAACGTTCAG-3′ |

| tag14 | 5′-GTACCGCGCTTAATGACATGG-3′ |

| tag15 | 5′-GTACCGCGCTTAATACTGGAG-3′ |

| tag16 | 5′-GTACCGCGCTTAAGTTCACTG-3′ |

| tag17 | 5′-GTACCGCGCTTAAATGCAGAG-3′ |

| tag18 | 5′-GTACCGCGCTTAACATAGCTG-3′ |

| tag19 | 5′-GTACCGCGCTTAAAGTAGAGG-3′ |

| tag20 | 5′-GTACCGCGCTTAAGTACCTAG-3′ |

| tag21b | 5′-GTACCGCGCTTAATAGAGCAG-3′ |

| tag22 | 5′-GTACCGCGCTTAACCTAGATG-3′ |

| tag23 | 5′-GTACCGCGCTTAACTACTGTG-3′ |

| tag24b | 5′-GTACCGCGCTTAAGTAACAGG-3′ |

| tag25 | 5′-GTACCGCGCTTAATGAACTCG-3′ |

| tag26 | 5′-GTACCGCGCTTAAGGTATCAG-3′ |

| tag27 | 5′-GTACCGCGCTTAACGAACTAG-3′ |

| tag28 | 5′-GTACCGCGCTTAACTGACATG-3′ |

| tag29 | 5′-GTACCGCGCTTAATCTGATGG-3′ |

| tag30b | 5′-GTACCGCGCTTAATTGACGTG-3′ |

| tag31 | 5′-GTACCGCGCTTAACTGTGAAG-3′ |

| tag32 | 5′-GTACCGCGCTTAACGTGATAG-3′ |

| tag33 | 5′-GTACCGCGCTTAATCGAATCG-3′ |

| tag34 | 5′-GTACCGCGCTTAACATGCTTG-3′ |

| tag35 | 5′-GTACCGCGCTTAAGATATCGG-3′ |

| tag36 | 5′-GTACCGCGCTTAACAGTTGAG-3′ |

| tag37 | 5′-GTACCGCGCTTAACGTATGTG-3′ |

| tag38 | 5′-GTACCGCGCTTAAGTATCACG-3′ |

| tag39 | 5′-GTACCGCGCTTAAATATCGCG-3′ |

| tag40 | 5′-GTACCGCGCTTAAACTACTGG-3′ |

| tag41 | 5′-GTACCGCGCTTAACTAGAACG-3′ |

The constant region is shown in normal font and the 7-bp variable region is in bold. The 5′ sequence is conserved for each tag to facilitate the binding of the primers to the template during the annealing step while the variable region is at the 3′ end to give specificity during the elongation step of the PCR reaction.

Tags that cross-reacted with other tags which were eliminated from the study.

Transposon mutant library.

Transposon mutagenesis of B. cenocepacia K56-2 was performed 41 separate times using each pTnMod-OTp-tagn plasposon to produce 96 individual K56-2 transposon mutants for each tagged transposon. Triparental matings were carried out as previously reported (15) to mobilize each plasposon into K56-2 with E. coli DH5α(pRK2013) as a helper strain (21). After transposition, insertion mutants were plated on minimal VBM media supplemented with trimethoprim to prevent the recovery of auxotrophic mutants, and finally the individual mutants were stored in 96-well plates.

Animal infections.

Infections were done using the agar bead model of chronic lung infection in rats as previously described (61). Two Sprague-Dawley male rats (150 to 160 g; Charles River Canada) were used for each infection pool of 37 B. cenocepacia transposon mutants containing 105 viable bacteria embedded in agar beads. The lungs were removed 10 days following intratracheal instillation into the left pulmonary lobe and homogenized using a Polytron homogenizer (Brinkman Instruments, Westbury, N.Y.). Serial dilutions in phosphate-buffered saline were plated on tryptic soy agar and on B. cepacia selective agar (BCSA) (27) containing 100 μg of trimethoprim/ml. The CFU were counted and bacteria collected for further analysis following incubation at 37°C overnight.

CI.

To determine the competitive index (CI) of selected STM mutants, mutant and wild-type bacteria were grown overnight and adjusted to the same optical density at 600 nm. Agar beads prepared from a mixture of parent and mutant combined to give approximately equal numbers (5 × 105 CFU of each strain) were used to inoculate groups of five rats. The ratio of mutant to wild-type bacteria in the inoculum was verified by plating agar beads containing bacteria on BCSA medium with and without trimethoprim to determine viable counts. At 10 days postinfection the lungs were removed, homogenized, diluted, and plated in triplicate on BCSA and BCSA containing 100 μg of trimethoprim/ml. The CI was calculated as the mean output ratio of mutant to wild type divided by the input ratio of mutant to wild-type organisms.

Screening of mutants by real-time PCR.

Real-time PCR was performed on B. cenocepacia transposon mutants recovered from lung homogenates using the Light Cycler (Roche Diagnostics). Chromosomal DNA was extracted from the bacterial pools and used as a template for real-time PCR using a Faststart DNA Master SYBR Green I kit for DNA amplification and detection (Roche Diagnostics). The forward primers used are listed in Table 1, and the reverse primer was STM-LC (5′-AAGGGAGAAAGGCGGACAGGTA-3′). The conditions used for real-time PCR to amplify the 342-bp product were as follows: activation for 10 min at 95°C, followed by 35 cycles of 95°C for 15 s, 55°C for 5 s, and 72°C for 11 s. A melting curve was generated by decreasing the temperature to 65°C, followed by a 0.2°C per second increase in the temperature up to 95°C. Quantitation curves and melting curves were generated for each 35-sample PCR run and analyzed using the Light Cycler software version 3.5 (Roche Diagnostics). Real-time PCR screening for the second screen was performed exactly the same as for the initial screen.

Identification and analysis of transposon insertion sites.

The chromosomal sequences surrounding the transposon insertions were identified using the self-cloning strategy as described previously (18). Briefly, chromosomal DNA from the B. cenocepacia transposon mutants that passed through the second screen was isolated and subjected to restriction endonuclease digestion by either SalI or NotI (Roche Diagnostics). The digests were ligated under dilute conditions to favor intramolecular ligations with T4 DNA ligase (Roche Diagnostics) and transformed into competent E. coli JM109 (70). Transformants were selected on LB agar supplemented with trimethoprim (50 μg/ml). Plasmid DNA was isolated using a High Pure plasmid isolation kit (Roche Diagnostics) and sequenced at the Core Molecular Biology Facility (York University, Ontario, Canada) using primers OTp-3′ (5′-TGTGGCTGCACTTGAACG-3′) or pTnMod (5′-TTCCTGGTACCGTCGACA-3′). The sequences obtained were compared to the GenBank database by BLAST to identify homologous sequences and to data from the B. cenocepacia sequencing group at the Sanger Institute for B. cenocepacia strain J2315 (http://www.sanger.ac.uk/Projects/B_cenocepacia/).

Analysis of B. cenocepacia proteins by two-dimensional gel electrophoresis.

Cytosolic proteins were obtained for two-dimensional gel electrophoresis by two passages in a French press (American Instrument Co., Inc., Silver Spring, Md.) at 20,000 lb/in2, and the protein concentration was estimated by Bradford assays (4) using Bio-Rad protein assay dye reagent concentrate. Protein from cell lysates (300 μg) was precipitated with 10% trichloroacetic acid, and the pellet was washed first with 5% trichloroacetic acid and then with acetone (25). Precipitated proteins were then subjected to rehydration on Immobiline DryStrip (pH 3 to 10, 13 cm; Amersham Biosciences, Uppsala, Sweden) for 10 h in rehydration solution (8 M urea, 2% 3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)-dimethylammonio]-1-propanesulfonate [CHAPS] and IPG buffer [Amersham Biosciences], pH 3 to 10) containing dithiothreitol, followed by isoelectric focusing for 1 h at 500 V, 1 h at 1,000 V, 5 h at 5,000 V, and 6.25 h at 8,000 V (IPGphor; Amersham Biosciences). After isoelectric focusing, IPG strips were equilibrated in equilibration buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.8, 6 M urea, 30% (vol/vol) glycerol, 2% (wt/vol) SDS, trace bromophenol blue) and applied to a 1-mm thick 12.5% polyacrylamide gel to resolve the second dimension. The gel was overlaid with 0.125% (wt/vol) agarose in SDS electrophoresis buffer containing bromophenol blue (3.02 g of Tris base/liter, 14.42 g of glycine/liter, 1% (wt/vol) SDS in distilled water). Gels were run at 10 mA per gel for 15 min followed by 20 mA for 5 h in SDS electrophoresis buffer. Proteins were visualized by SYPRO orange (Bio-Rad Laboratories) according to the manufacturer's instructions and then stained with Coomassie brilliant blue (0.25% Coomassie brilliant blue, 45% methanol, 10% glacial acetic acid; distained with 45% methanol and 10% glacial acetic acid). Gels were dried using a Bio-Rad gel dryer model 583 (Bio-Rad Laboratories). To assess reproducibility and standardize the preparation of extracts and the conditions for running the two-dimensional gel electrophoresis, gels with samples from the wild-type strain K56-2 were run four times, and those with samples from the mutants strains were run twice. Spots were analyzed using ImageMaster 2D Elite software (NonLinear Dynamics, Durham, N.C.).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Construction and characterization of the tagn plasposon derivatives.

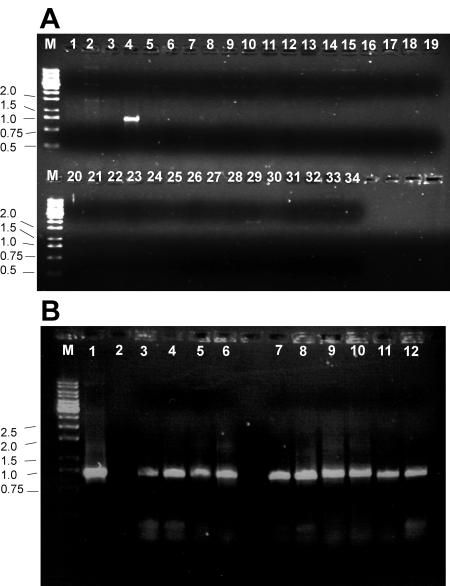

To distinguish individual transposon mutants within a pool, 41 oligonucleotide tags, each consisting of 21 bp, were incorporated into the transposon backbone of pTnMod-OTp′ near one of the inverted repeats to generate 41 unique plasposons pTnMod-OTp′-tagn (Fig. 1). The 21-bp oligonucleotides were designed such that the 14 residues at the 5′ end were identical, while the 7-bp region near the 3′ end was unique to each tag (Table 1) (39). The pTnMod-OTp′ plasposon was previously shown to successfully integrate at random into the chromosome of B. cepacia complex isolates following mobilization from an E. coli host strain (18-20). The presence of a dhfr gene within the transposable element confers resistance to trimethoprim, one of the few antibiotics to which most strains of the B. cepacia complex are sensitive (38, 49). Prior to the construction of the transposon mutant library for infection in the animal model, we examined each of the 41 plasposons by PCR to investigate possible cross-amplification among the individual tags. This control was necessary since cross-amplifications would be detrimental to the STM experiment, as potential mutants unable to survive in the in vivo animal model would be misidentified. We tested each of the 41 pTnMod-OTp-tagn plasmids against each other using a primer set consisting of an upstream primer that anneals 811 bp upstream of the 21-bp oligonucleotide tag within the transposon (STM-common) and a downstream primer which was the 21-bp oligonucleotide tag itself (Fig. 1). Figure 2A shows a representative gel in which the PCR was performed with the tag2-specific and STM-common primers, with the various pTnMod-OTp-tagn plasmids as DNA templates. The absence of PCR amplification in the reactions with all the plasposons not containing tag2 indicated that this tag did not cross-amplify with any of the other tag oligonucleotides. A series of PCRs was performed for each tag primer in a similar manner as with tag2. These experiments allowed us to eliminate four pTnMod-OTp-tagn plasposons carrying the oligonucleotide tags 13, 21, 24, and 30, which cross-amplified with other tags (Table 1 and data not shown). The tags in the remaining 37 pTnMod-OTp-tagn plasposons did not cross-amplify during PCR amplifications and were thus used for further steps in the STM procedure.

FIG. 2.

Representative gels of control experiments testing specificity of the tags and sensitivity of the PCR amplification to detect the tags on the chromosome. (A) The tag2 plasposon does not cross-amplify with the other tag oligonucleotides. PCR was performed using the plasposon pTnMod-OTp-tag2 as a template. The primer STM-common was used with a different tag-specific primer in each reaction. Lane M: 1-kb ladder molecular weight markers; lane 1, distilled H2O template with tag2 primer (reaction negative control); lane 2, pTnMod-OTp′ lacking tag insertions with tag2 primer (template negative control). Lanes 3 to 34 were loaded with amplification products from the reactions containing pTnMod-OTp-tag2 template and each of the various tagn primers, beginning with lane 3 using tag1 until lane 34 using tag32. PCR amplification is specific for tag2 as indicated by the lack of PCR amplification in all lanes except lane 4. (B) Tag oligonucleotides can be detected from the B. cepacia chromosome by PCR after transposition. For each PCR amplification, the primer STM-common was used in combination with the indicated tagn-specific primer. Lane M: 1-kb ladder molecular weight markers; lane 1, pTnMod-OTp-tag1 with the tag1 primer (template positive control); lane 2, pTnMod-OTp′ with the tag1 primer (template negative control); lanes 3 to 6, PCR amplifications with the tag1 primer using chromosomal DNA from four independent K56-2::tag1 transposon mutants; lanes 7 to 10, PCR amplifications with the tag2 primer using chromosomal DNA from four independent K56-2::tag2 transposon mutants; lanes 11 and 12, PCR amplifications with the tag1 (lane 11) and tag2 (lane 12) primers using chromosomal DNA from a mixed culture containing K56-2::tag1 and K56-2::tag2 mutants.

An additional control was done to ensure that the oligonucleotide tags could be detected once the transposon was inserted in the B. cenocepacia chromosome. Because the genome of B. cenocepacia has an approximate G+C content of 67 mol%, PCR using chromosomal DNA as a template can often yield no amplification products or several nonspecific bands, possibly due to mispriming. In addition, high stringency conditions are required for the PCR amplifications due to the high sequence similarity between the oligonucleotide tags. PCR was performed using the STM-common and tag-specific primers to demonstrate, as shown in Fig. 2B, that the appropriate tag could be detected from B. cenocepacia chromosomal DNA. Furthermore, specific tags could also be detected when DNA from mixed cultures was used as a template (Fig. 2B). These preliminary tests demonstrated that the tags and plasposon constructed could be used for the STM screening in B. cenocepacia.

Identification of survival-defective mutants by real-time PCR screening.

The 37 plasposons were then separately mobilized into B. cenocepacia K56-2 by triparental conjugation to produce 96 transposon mutants for each of the tags. The 37 banks of B. cenocepacia transposon mutants were next arranged into pools such that any individual pool contained one of each of the tag-specific transposon mutants. Thus, each pool contained 37 distinct transposon mutants which could be individually distinguished from one another by the presence of the unique 21-bp oligonucleotide tag within the integrated transposon. The pools of transposon mutants were separately incorporated into agar beads, and the beads were used for intratracheal lung infection in rats. Each infection was performed in duplicate and allowed to proceed for 10 days, an interval which results in chronic lung infection (C. Kooi and P. A. Sokol, unpublished data). After the 10-day infection, the lungs were removed and the recovered bacteria were collected for DNA preparation and PCR screening to identify the surviving mutants in each original pool.

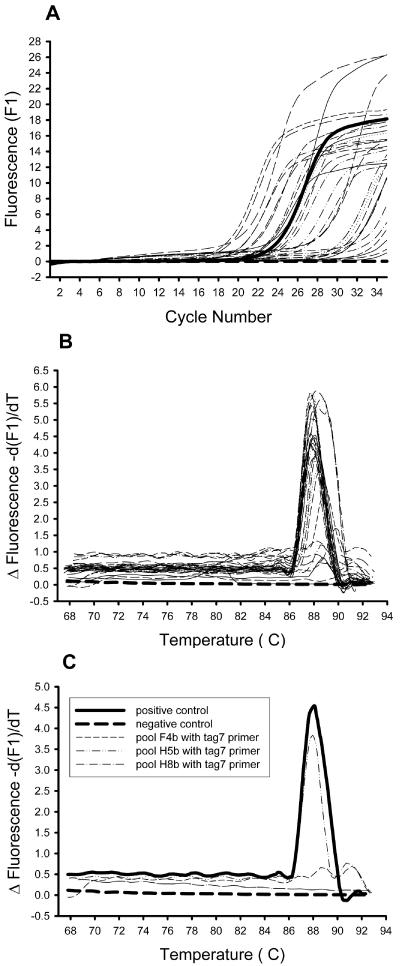

The 21-bp oligonucleotide tags containing unique sequences within each transposon enabled differentiation of mutants that were present from those mutants which were absent from each of the output pools. DNA from the B. cenocepacia mutants that were recovered from the lung infections served as templates for PCR amplification. Because infections with each pool of mutants were carried out in duplicate, screening of mutants was done with the infection that exhibited the highest bacterial yield, as this would result in the lowest probability of false negatives. We used real-time PCR amplification with primer sets similar to those employed to test cross-reactivity (STM-LC and each specific tag oligonucleotide). Quantitation and melting curves were generated for each of the PCR amplifications. Figure 3 illustrates the data analysis of one PCR run. For each run, a positive and a negative control were included together with 33 sample reactions. The product quantitation curve (Fig. 3A) indicated the amount of double-stranded PCR product generated following each cycle. In the case of DNA prepared from bacteria recovered from rat lungs, we observed quantitation curves ranging from no product to more product than with the positive control. After each round of PCR amplification, a melting curve was generated for each run of 35 samples (Fig. 3B). This demonstrated whether a PCR product generated was specific, by comparing it with the product from the positive control reaction, which consistently had a peak at about 88°C. The melting curve was more informative than the quantitation curve because it indicated whether or not the observed amplification was specific. Figure 3C shows a subset of the melting curves in Fig. 3B, including the positive and negative control plus three sample reactions. In this example, the tag7 mutant in pools F4b and H8b did not amplify with the tag7-specific primer, and therefore these mutants were not present in the pool and would pass through this screening procedure. Seventy-one pools of B. cenocepacia transposon mutant chromosomes were screened in this manner with the 37 tag primers. One important limitation of STM for in vivo screening is that the inoculated pool must have a dose such that each mutant is well represented and is able to establish an infection. To determine if this was the case with our pools, the input pools were randomly examined by real-time PCR, and the amplified DNA from the mutants in these pools gave similar quantitation curves, suggesting that the individual mutants were present at similar concentrations (data not shown). Mutants attenuated for survival in the animal model were scored as those whose genomic DNA did not reveal any PCR amplification after 28 cycles on the quantitation curve or, alternatively, had low or nonspecific melting peaks (peaks not at about 88°C) on the melting curve. According to these criteria, 260 of the 2,627 mutants that we assayed were putatively identified as having a survival defect in the animal model.

FIG. 3.

Sample real-time PCR results from the STM screen. An example of one run of 35 samples is shown with 33 output pools plus a positive and negative control sample. (A) Quantitative curve showing the PCR amplification (measured as relative fluorescence units) in real time after each cycle. (B) Melting curve showing the change in fluorescence as the temperature is increased from 68 to 94°C. The specific PCR product can be seen as a sharp peak at approximately 88°C. For panels A and B, the positive control is shown as a thick solid line and the negative control as a thick dashed line. (C) A subset of the PCR amplifications shown in panels A and B were taken, and a melting curve was generated. The positive and negative controls are shown along with three representative output pools. The melting curve of pool H5b is similar to the positive control and therefore does not contain a mutant important for survival in vivo. The melting curves of pools F4b and H8b indicate no PCR amplification, and therefore the mutants are not in the pools and contain transposon insertions in genes important for survival in the animal model.

To eliminate potential false positives due to the large number of mutants in each pool, the 260 mutants obtained from the first screen were rearranged into 30 smaller pools containing 6 to 13 mutants per pool. Each pool was encased into agar beads and used to infect duplicate rats for 10 days as before. The output pools were reanalyzed by real-time PCR as for the first screen, except that this second screen was much more stringent. Only those mutants that did not show any amplification after 35 cycles in the quantitation curve and had no demonstrable peak in the melting curve were considered to pass this second screen. After the second screen, 102 mutants were identified, each containing transposon insertions in candidate genes required for the survival of B. cenocepacia in the rat agar bead model. Our finding that 102 out of 2,627 mutants (3.8%) were unable to survive in an in vivo model correlated well with figures obtained from previous STM experiments using other bacterial pathogens, which have detected a frequency of survival-defective mutants ranging from 0.2 to 13% (48). The survival-defective mutants did not appear to have growth defects in vitro, as all of them grew in nutrient broth at levels comparable with the wild-type K56-2 (data not shown).

Identification of genes required for survival in vivo and confirmation of the predictive value of the STM screen.

The nucleotide sequence of the DNA flanking the site of transposon insertion obtained for each of the 102 attenuated mutants was used to search the GenBank databases for homologous genes. The results of this analysis are shown in Table 2, located within a putative replication region. We speculate that these insertions may result in the instability of the 90-kb plasmid in vivo. It is possible that the instability or even loss of the plasmid in vivo may impair the survival of the plasmid-free bacterial cells by mechanisms involving killing or growth reduction of these cells (for a recent review, see reference 26). Further research is currently under way in our laboratory to explore this possibility. In addition, four survival-attenuated mutants had insertions within two rRNA clusters. While the role of rRNA clusters in virulence is not known at this time, others have found that five of the seven rRNA operons present in E. coli are necessary to support near-optimal growth on complex media, while all seven operons are necessary for rapid adaptation to nutrient and temperature changes (11). Therefore, it is conceivable that a similar situation occurs for B. cenocepacia, and adaptation to the environmental conditions found in vivo may require a full complement of rRNA operons.

TABLE 2.

Identification of the genes with transposon insertions in the survival-defective mutants of B. cenocepacia K56-2

| Class | Mutant | Location or similarity [gene (species); accession no.]a | Known or putative functionf | Type of insertionb | Location in J2315 | % DNA identity to J2315 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metabolism | 1A5 | RSp0749 (Ralstonia solanacearum); NP_522310 | ClpA, chaperone, ATPase | INT | Chromosome 1 | 100 |

| 2A5 | Rsc0772 (Ralstonia solanacearum); NP_518893 | Cytochrome c (oxidoreductase/dehydrogenase) | CDS | Chromosome 2 | 99 | |

| 3F4 | Bcep0615 (Burkholderia sp.)c; ZP_00027845 | Phosphate starvation-inducible protein | CDS | Chromosome 1 | 94 | |

| 3A6 | Bcep4150 (Burkholderia sp.)c; ZP_00031317 | xdhA, xanthine dehydrogenase subunit A | CDS | Chromosome 1 | 99 | |

| 4A7 | Bcep0315 (Burkholderia sp.)c; ZP_00027557 | paaE, ferredoxin reductase | CDS | Chromosome 1 | 100 | |

| 4F9 | Bcep0165 (Burkholderia sp.)c; ZP_00027409 | Long-chain fatty acid CoA ligase | CDS | Chromosome 1 | 94 | |

| 6E9 | Bcep1341 (Burkholderia sp.)c; ZP_00028560 | tdh, Zn2+-dependent threonine-3-dehydrogenase | CDS | Chromosome 2 | 77 | |

| 9F3 | blr0281 (Bradyrhizobium japonicum); BAC455546 | oxd, oxalate decarboxylase | CDS | Chromosome 2 | 99 | |

| 17D8 | CAC3312 (Clostridium acetobutylicum); NP_349904 | fkbH, methoxymalonyl-ACP biosynthesis | UP | Chromosome 1 | 83 | |

| 18D2 | Bcep7606 (Burkholderia sp.)c; ZP_00034711 | Succinyl-diamino-pimelate desuccinylase | CDS | Chromosome 2 | 99 | |

| 20D2 | Bcep3497 (Burkholderia sp.)c; ZP_00030674 | d-lactate-dehydrogenase/oxidoreductase | INT | Chromosome 1 | 98 | |

| 28D9 | Bcep033 (Burkholderia sp.)c; ZP_00027284 | Translation initiation inhibitor, TdcF and yjgF family and just upstream from phenazine biosynthesis protein (epimerase) | CDS | Chromosome 1 | 98 | |

| 31C5 | Chlo1457 (Chlorofexus aurantiacus); ZP_00018467 | Acetyltransferase of the GNAT family | CDS | Chromosome 3 | 99 | |

| 31F1 | Bcep5460 (Burkholderia sp.)c; ZP_00032601 | xdhC, xanthine dehydrogenase chaperone | UP | Chromosome 1 | 100 | |

| 31E2 | Bcep2710 (Burkholderia sp.)c; ZP_00029902 | amiC, N-acetyl-muramoyl-l-alanine-amidase | CDS | Chromosome 1 | 97 | |

| 33G2d | Bcep4417 (Burkholderia sp.)c; ZP_00031577 | Enoyl-CoA hydratase | CDS | Chromosome 1 | 88 | |

| 33G4 | Reut3200 (Ralstonia metallidurans); ZP_00024228 | tyrB, aromatic amino acid transferase | CDS | Chromosome 2 | 95 | |

| 38E2d | Bcep3466 (Burkholderia sp.)c; ZP_00030645 | hemK, methyl transferase | CDS | Chromosome 1 | 99 | |

| 39H6 | Rsc1246 (Ralstonia solanacearum); NP_519367 | iolG, myo-inositol 2-dehydrogenase | CDS | Chromosome 1 | 100 | |

| 39A8 | Bcep0325 (Burkholderia sp.)c; ZP_00027566 | NADPH quninone oxidoreductase | CDS | Chromosome 1 | 99 | |

| 40C2 | Bcep6429 (Burkholderia sp.)c; ZP_00033555 | glk, gluconate kinase 2 (thermoresistant) | CDS | Chromosome 1 | 99 | |

| DNA repair/replication/translation | 7C6 | Bb3088 (Bordetella bronchiseptica); NP_889624 | dnaE, DNA polymerase III alpha chain | CDS | Plasmid | 99 |

| 7F4 | BVI17805 (Burkholderia vietnamiensis); Y18705 | 23S rRNA gene | CDS | Chromosome 1 | 100 | |

| 9A2 | BVI17805 (Burkholderia vietnamiensis); Y18705 | 23S rRNA gene | CDS | Chromosome 1 | 100 | |

| 9D5 | PC23RRNA (Burkholderia cepacia); X16368 | 23S rRNA gene | CDS | Chromosome 1 | 100 | |

| 33D9 | PC23RRNA (Burkholderia cepacia); X16368 | 23S rRNA gene | CDS | Chromosome 1 | 100 | |

| 11F4 | XAC1107 (Xanthomonas axonopodis); NP_641445 | Integrase/resolvase/recombinase | CDS | Chromosome 1 | 96 | |

| 15B2 | RSc3441 (Ralstonia solanacearum); NP_521560 | dnaN, DNA polymerase III beta chain | UP | Chromosome 1 | 92 | |

| 16E1 | hsdM1 (Chlorobium tepidum); NP_661571 | Type I restriction system adenine methylase | INT | Chromosome 1 | 99 | |

| 27B2 | retA (Serratia marcescens incL/M plasmid R471a); AAC82519 | Reverse transcriptase | CDS | Plasmid | 96 | |

| 27C6 | PCRRN5S (Burkholderia cepacia); X02629 | 5S rRNA gene | CDS | Chromosome 3 | 95 | |

| 28F4 | repA (Pseudomonas fluorescens pAM10.6 plasmid); AAG23805 | Replication protein | UP | Chromosome 2 | 98 | |

| 28G3 | Bcep2527 (Burkholderia sp.)c; ZP_00029720 | gidA, glucose-inhibited protein division A | CDS | Chromosome 1 | 100 | |

| 31B3 | DNA methylase (Burkholderia multivorans); BAC65265 | DNA methyl-transferase | CDS | Chromosome 2 | 99 | |

| 40C1 | Bcep6969 (Burkholderia sp.)c; ZP_00034082 | Phosphoesterase; DNA repair exonuclease | CDS | Chromosome 2 | 96 | |

| Regulatory | 1H4 | nasR (Klebsiella oxytoca); Q48468 | Nitrate/nitrite response regulator | UP | Chromosome 1 | 99 |

| 4G5 | hns (Ralstonia solanacearum); NP_591826 | H-NS transcriptional regulator (histone family) | CDS | Chromosome 1 | 99 | |

| 4H4 | Bcep6214 (Burkholderia sp.); ZP_00033342 | LysR family of transcriptional regulators | CDS | Chromosome 1 | 97 | |

| 14B8 | Bcep5162 (Burkholderia sp.); ZP_00032313 | LysR family of transcriptional regulators | UP | Chromosome 2 | 98 | |

| 11E2 | Bcep2955 (Burkholderia sp.)c; ZP_00030142 | Sensory protein with Rtn domain | UP | Chromosome 1 | 99 | |

| 18B2d | Bcep2486 (Burkholderia sp.)c; ZP_00029679 | OmpR family response regulator | CDS | Chromosome 1 | 96 | |

| 34A1 | Bcep4207 (Burkholderia sp.)c; ZP_00031373 | Transcriptional regulator, sigma factor 54 | CDS | Chromosome 1 | 98 | |

| 38C6 | Bcep8011 (Burkholderia sp.)c; ZP_00035109 | cspC, cold shock protein transcriptional regulator | CDS | Chromosome 1 | 90 | |

| 39H4 | Bcep8011 (Burkholderia sp.)c; ZP_00035109 | cspC, cold shock protein transcriptional regulator | CDS | Chromosome 1 | 90 | |

| 40H2 | tetR (Salmonella enteritidis); AAN40999 | Tetracycline resistance repressor | CDS | Chromosome 1 | 75 | |

| Cell surface | 6A5 | Bcep1318 (Burkholderia sp.)c; ZP_00028537 | arnC; polymyxin resistance, glycosyl transferase | CDS | Chromosome 1 | 98 |

| 7C5 | yggB (Burkholderia mallei); AAK26451 | Small-conductance mechanosensitive channel | CDS | Chromosome 1 | 99 | |

| 28D8 | galU (Burkholderia pseudomallei); AAG24457 | UTP-glucose-1-phosphate uridylyltransferase | UP | Chromosome 2 | 92 | |

| 32D2 | wbiF (Burkholderia mallei); AAK27402 | Glycosyltransferase, LPS synthesis | CDS | Chromosome 1 | 91 | |

| 33H3d | wbiI (Burkholderia mallei); AAK27405 | Epimerase/dehydratase, LPS synthesis | CDS | Chromosome 1 | 99 | |

| 34C6 | RS01942 (Ralstonia solanacearum); NP_522327 | Transmembrane protein, cell wall biogenesis | CDS | Chromosome 1 | 99 | |

| 34D8 | rmlD (Burkholderia mallei); AAK27394 | dTDP-4-keto-l-rhamnose reductase, LPS synthesis | CDS | Chromosome 1 | 99 | |

| 36B4 | cpxA (Neisseria meningitidis); NP_283042 | Capsule polysaccharide export ATP-binding protein | CDS | Chromosome 1 | 99 | |

| 38C2 | SYNW0645 (Synechococcus sp.); NP_896738 | Glycosyltransferase, LPS synthesis | CDS | Chromosome 1 | 99 | |

| 41H5 | Bcep6693 (Burkholderia sp.)c; ZP_00033811 | pbp1, penicillin binding protein (cell wall synthesis) | CDS | Chromosome 2 | 99 | |

| Transport | 3A3 | CV1105 (Chromobacterium violaceum); NP_900675 | Cation efflux protein | UP | Chromosome 1 | 96 |

| 26H6 | CV1105 (Chromobacterium violaceum); NP_900675 | Cation efflux protein | UP | Chromosome 1 | 99 | |

| 6C3 | Bcep6477 (Burkholderia sp.)c; ZP_00033603 | Permease, major facilitator superfamily | UP | Chromosome 1 | 68 | |

| 6E3 | Bcep6966 (Burkholderia sp.)c; ZP_00034080 | mgtC, magnesium transport ATPase protein | CDS | Chromosome 2 | 94 | |

| 6F7 | Bcep4313 (Burkholderia sp.)c; ZP_00031476 | Na+-dependent transporter | UP | Chromosome 2 | 98 | |

| 14D9 | YPO2237 (Yersinia pestis); NP_405778 | uhpC, sugar phosphate permease | CDS | Chromosome 2 | 98 | |

| 16H2 | BPP0439 (Bordetella parapertussis); NP_882791 | Potassium channel protein | UP | Chromosome 2 | 98 | |

| 16H8 | Bcep3454 (Burkholderia sp.)c; ZP_00030633 | ugpB, glycerol-3-P binding periplasmic protein | CDS | Chromosome 1 | 94 | |

| 18F4 | RS03722 (Ralstonia solanacearum); NP_521805 | Outer membrane hemin binding receptor | UP | Chromosome 2 | 94 | |

| 28D5 | Bcep1249 (Burkholderia sp.)c; ZP_00028468 | Low-pH inducible transmembrane protein | CDS | Chromosome 2 | 98 | |

| 33B1 | Reut5126 (Ralstonia metallidurans); ZP_00026117 | Mechanosensitive ion channel | CDS | Chromosome 2 | 93 | |

| 38C1 | Reut0257 (Ralstonia metallidurans); ZP_00021356 | ABC transporter transmembrane permease | CDS | Chromosome 1 | 97 | |

| 38E2d | PP3940 (Pseudomonas putida); NP_746070 | uhpC, sugar phosphate permease | CDS | Chromosome 2 | 95 | |

| 41H4 | oxlT2 (Archaeoglobus fulgidus); NP_069203 | Oxalate/formate antiporter | CDS | Chromosome 1 | 96 | |

| UNknown | 9C1 | Bcep1803 (Burkholderia sp.)c; ZP_00029009 | Hypothetical protein | CDS | Chromosome 1 | 98 |

| 10F1 | jhp0052 (Helicobacter pylori); NP_222774 | Hypothetical protein (same gene as in 33F9) | UP | Chromosome 1 | 98 | |

| 10H4 | CAC2823 (Clostridium acetobutylicum; AAK80767 | Conserved protein | CDS | Chromosome 1 | 99 | |

| 17A3 | Bcep4709 (Burkholderia sp.)c; ZP—00031868 | Hypothetical protein | DS | Chromosome 1 | 90 | |

| 17C6 | Bcep1157 (Burkholderia sp.)c; ZP—00028378 | Hypothetical protein | UP | Chromosome 1 | 96 | |

| 18B2d | No matches in databases | Hypothetical protein | CDS | Chromosome 3 | 92 | |

| 23F5 | Bcep0344 (Burkholderia sp.)c; ZP_00027585 | Hypothetical protein | UP | Chromosome 2 | 99 | |

| 31G1 | Bcep2682 (Burkholderia sp.)c; ZP_00029874 | Hypothetical protein | CDS | Chromosome 3 | 98 | |

| 33G2d | Bcep5345 (Burkholderia sp.)c; ZP_00032488 | Conserved hypothetical protein | CDS | Chromosome 2 | 94 | |

| 33H3d | No matches in databases | Hypothetical protein | CDS | Chromosome 2 | 99 | |

| 33F4 | Bcep6478 (Burkholderia sp.)c; ZP_00033604 | Hypothetical protein; lipoprotein? | UP | Chromosome 1 | 99 | |

| 33F9 | jhp0052 (Helicobacter pylori); NP_222774 | Hypothetical protein (same gene as in 10F1) | UP | Chromosome 1 | 94 | |

| 34C4 | RSp0741 (Ralstonia solanacearum); NP_522302 | Hypothetical transmembrane protein | UP | Chromosome 1 | 92 | |

| 37G5 | RSp0747 (Ralstonia solanacearum); NP_522308 | Conserved bacterial protein | INT | Chromosome 1 | 99 | |

| 38H2 | yfiI (Escherichia coli CFTG073); AAN82100 | Hypothetical protein | CDS | Chromosome 1 | 99 | |

| 38F5 | Just downstream of replication protein gene trfA | Putative plasmid replication ori | Plasmid | 99 | ||

| 38H5 | Unknown, not near any predicted open reading frames | Chromosome 3 | ||||

| 39G4 | PP2099 (Pseudomonas putida); NP_744249 | Conserved bacterial protein | INT | Chromosome 1 | ||

| Undeterminedc | 4A6 | Unknown location | INT | |||

| 20C7 | Unknown location; near an IS407 insertion | INT | ||||

| 20E9 | Unknown location | INT | ||||

| 20H6 | Unknown location; near an IS407 insertion | INT | ||||

| 23G8 | Unknown location | INT | ||||

| 25A3 | Unknown location; near 23S rRNA cluster and IS407 | INT | ||||

| 33B4 | Unknown location; near 5S rRNA cluster | INT | ||||

| 36C2 | Unknown location; near 5S rRNA cluster | INT | ||||

| 37A8 | Unknown location | INT | ||||

| 37E1 | Unknown location; near an IS407 insert | INT | ||||

| 37H8 | Unknown location | INT | ||||

| 38F4 | Unknown location; near 23S rRNA cluster and IS407 | INT | ||||

| 39C9 | Unknown location | INT | ||||

| 39D7 | Unknown location | INT | ||||

| 39D8 | Unknown location | INT | ||||

| 41A6 | Unknown location; near 23S rRNA cluster and IS407 | INT | ||||

| 41C6 | Unknown location; near 5S rRNA cluster | INT | ||||

| 41C9 | Unknown location | INT | ||||

| 41F7 | Unknown location; near 23S rRNA cluster and IS407 | INT |

Sequenced gene in public databases with the highest similarity to STM sequences. Names of source bacteria are shown in parentheses. In some instances, gene designations are from whole genome sequences, giving a two-letter code for the bacterium followed by the sequence number (e.g., NP_522310).

UP, transposon insertion upstream of gene (possibly within promoter region); CDS, transposon insertion within coding region; INT, entire plasposon integrated in the K56-2 chromosome or plasmid.

This isolate is erroneously designated in the databases as B. fungorum strain LB400.

Two insertions in different locations were found in the same mutant strain.

These mutants have all of the entire plasposon integrated into the genome of B. cenocepacia K56-2, but the precise location of the integration could not be determined.

ACP, acyl carrier protein; LPS, lipopolysaccharide.

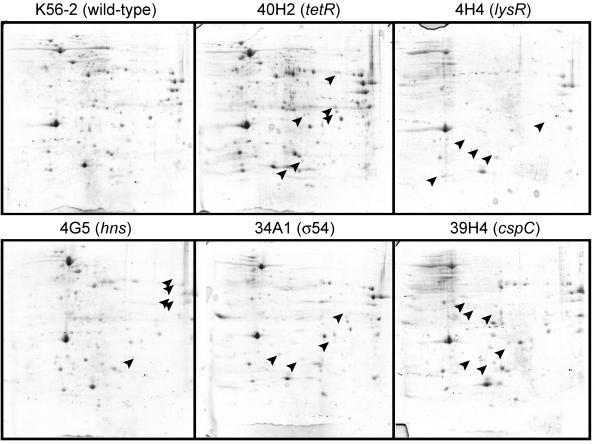

We detected several mutants with insertions in putative regulatory genes, including members of the LysR family of transcriptional regulators, an H-NS-like protein, a TetR repressor, a regulator from the cold shock family, and two members of the sensor kinase two-component regulatory systems. It is conceivable that the survival-defective phenotype of these mutants may be due to the dysregulation of effector genes whose expression is controlled or modulated by these proteins rather than the lack of the regulator itself. To determine whether these regulatory genes indeed encode global regulators, we compared the profiles of cytosolic proteins of each mutant and the K56-2 parental isolate by two-dimensional gel electrophoresis (Fig. 5). The profiles of mutants 4H4 (predicted LysR transcriptional regulator homologue), 4G5 (predicted H-NS regulatory gene), 34A1 (σ54 homologue), 38C6 and 39H4 (cold shock family of transcriptional regulator), and 40H2 (Tet-repressor regulator homologue) were compared to that of the wild-type K56-2. The mutant 40H2, containing an insertion in the TetR family repressor homologue, revealed additional protein spots not observed in the parental K56-2 lysate, whereas mutants containing insertions in positive regulators lacked several protein spots that are present in the lysate from the parental K56-2 strain (Fig. 5). These results are consistent with the predicted roles for these regulatory proteins. Ongoing research is underway to confirm that these regulators are indeed involved in the different protein expression profiles observed, to characterize the regulated proteins from the proteome of K56-2, and to determine the components of each regulon.

FIG. 5.

Two-dimensional gel electrophoresis analysis of the parental B. cenocepacia K56-2 (wild type) and STM mutants predicted to contain insertions in regulatory genes (Table 2). Isoelectric focusing from pH 3 to 10 was performed for the first dimension (left to right, horizontal), and SDS-PAGE was performed for the second dimension (vertical) for each gel. Proteins were stained with Coomassie brilliant blue for visualization. Arrowheads in 40H2, which has an insertion in a gene encoding a putative protein repressor of the TetR family, indicate protein spots not present in the wild-type strain K56-2. Arrowheads in the gels from the other mutants indicate the most obvious protein spots that are present in K56-2 but absent in the mutant strains, all of which have insertions in genes encoding putative positive regulators.

We found 14 attenuated mutants with insertions compromising genes involved in transport functions, including a cation efflux protein (mutants 3A3 and 26H6), several permeases, and ABC transporters (Table 2). One other insertion was found just upstream of a gene encoding a predicted 96-kDa outer membrane heme-binding receptor protein (mutant 18F4). This is the first gene of a putative operon that may be involved in heme uptake. Heme-binding proteins of molecular masses ranging from 96 to 100 kDa have been recently described in many strains of the B. cepacia complex (60). Expression of heme-binding proteins leading to heme binding and accumulation is associated with virulence in several gram-negative pathogens (36). For example, in Porphyromonas gingivalis the accumulation of heme appears to protect bacterial cells against damage from hydrogen peroxide (59). Thus, an outer membrane heme-binding protein may contribute to in vivo survival by enabling B. cenocepacia to withstand oxidative stresses in inflammatory exudates in the lung.

Mutant 6E3 has an insertion interrupting a gene that encodes a homologue of the MgtC protein. This protein is required in S. enterica and Mycobacterium tuberculosis for growth under Mg2+-limiting environments, as well as for survival within macrophages and virulence in vivo (2, 5). Preliminary experiments indicate that, unlike the wild-type strain K56-2, the growth of this mutant is drastically reduced at Mg2+ concentrations of 25 μM or lower (K. Maloney and M. A. Valvano, unpublished data). Since B. cepacia complex strains can survive intracellularly within amoebae and macrophages (44, 56), we speculate that the MgtC protein homologue may be required for survival in vivo during lung infection in the rat model.

Additional mutants within this category had insertions in genes encoding enzymes required for the synthesis of O-antigen LPS (mutants 32D2, 33H3, 34D8, and 38C2). The isolation of genes involved in LPS synthesis for survival in vivo is not unexpected, as nearly all STM studies of gram-negative pathogens have reported similar findings (8, 17, 28, 33, 63). The detailed characterization of the O-antigen LPS biosynthesis cluster in K56-2 and J2315 strains will be described in detail elsewhere (X. Ortega, T. A. Hunt, and M. A. Valvano, manuscript in preparation).

Conclusion.

The majority of the genes identified in our STM screen do not correspond to classical virulence factors proposed by others for B. cenocepacia. Given the large size of the B. cenocepacia genome (8.056 Mbp), it is possible that our screen has not uncovered all the genes required for in vivo survival. Also, it is important to point out that our screen was specifically designed to detect factors involved with in vivo survival and persistence in the lungs from our rat model. Early colonization steps are bypassed in our lung infection model, as bacteria instilled intratracheally are previously encased in agar beads. Thus, we did not expect to find mutants in genes involved with mucosal colonization. Also, STM screens do not usually detect extracellular factors that may be required for infection, since these factors may be provided by other mutants in the pool. The real-time PCR screening described in this study greatly reduced the time required for the screening step while increasing the sensitivity and specificity by allowing quantification of the PCR products produced. In addition, the plasposons and the bank of transposon mutants we generated will permit us to screen for bacterial genes required for survival in other in vivo models. An important limitation of STM screens is that the insertions may cause polar effects on the expression of downstream genes, which is especially true for those insertions in genes that are part of operons and those located upstream of coding regions, which may affect promoter elements or other regulatory elements. Therefore, our results should not be overinterpreted, as they provide a list of genes that are prime candidates as survival genes but that requires a gene-by-gene detailed analysis. We are currently investigating the survival of B. cenocepacia mutants in various infection models including alfalfa (1), amoebae (44), and the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans (35), which represent different habitats that can all be potentially encountered by B. cepacia complex isolates. Elucidation of the genes required for B. cepacia survival in these models will provide us with a more complete picture of requirements for infection of this opportunistic pathogen.

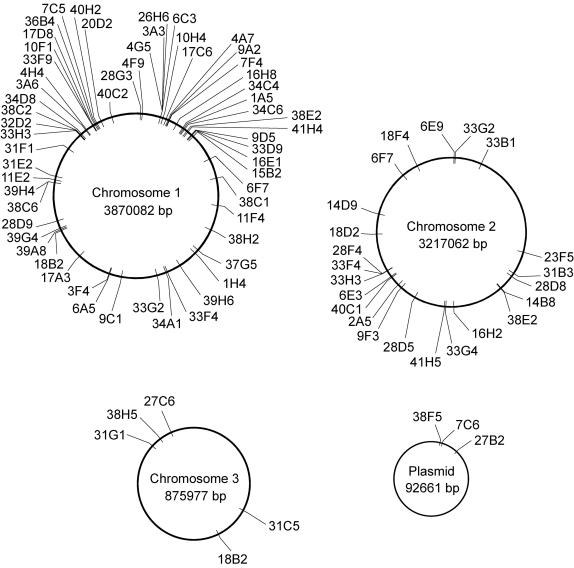

FIG. 4.

Schematic representation of the chromosomal locations of the transposon insertions of B. cenocepacia K56-2 survival-defective mutants. This genome map is based on sequence information generated for B. cenocepacia strain J2315 by the B. cepacia Sequencing Group at the Sanger Institute and can be obtained at http://www.sanger.ac.uk/Projects/B_cepacia.

Acknowledgments

We thank J. Vicarioli, M. Visser, and K. Maloney for useful comments and technical assistance.

This work was supported by the Thompson Family Fund (to M.A.V.) from the Canadian Cystic Fibrosis Foundation and by the Special Program Grant Initiative “In Memory of Michael O'Reilly” funded by the Canadian Cystic Fibrosis Foundation and the Cardiovascular and Respiratory Health Institute of the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (to M.A.V. and P.A.S.). T.A.H. was supported by a fellowship from the Canadian Cystic Fibrosis Foundation. M.A.V. holds a Canada Research Chair in Infectious Diseases and Microbial Pathogenesis.

Editor: J. N. Weiser

REFERENCES

- 1.Bernier, S. P., L. Silo-Suh, D. E. Woods, D. E. Ohman, and P. A. Sokol. 2003. Comparative analysis of plant and animal models for characterization of Burkholderia cepacia virulence. Infect. Immun. 71:5306-5313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blanc-Potard, A. B., and E. A. Groisman. 1997. The Salmonella selC locus contains a pathogenicity island mediating intramacrophage survival. EMBO J. 16:5376-5385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bottone, E. J., S. D. Douglas, A. R. Rausen, and G. T. Keusch. 1975. Association of Pseudomonas cepacia with chronic granulomatous disease. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1:425-428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bradford, M. M. 1976. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 72:248-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buchmeier, N., A. Blanc-Potard, S. Ehrt, D. Piddington, L. Riley, and E. A. Groisman. 2000. A parallel intraphagosomal survival strategy shared by Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Salmonella enterica. Mol. Microbiol. 35:1375-1382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burns, J. L., M. Jonas, E. Y. Chi, D. K. Clark, A. Berger, and A. Griffith. 1996. Invasion of respiratory epithelial cells by Burkholderia (Pseudomonas) cepacia. Infect. Immun. 64:4054-4059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cerantola, S., J. Bounery, C. Segonds, N. Marty, and H. Montrozier. 2000. Exopolysaccharide production by mucoid and non-mucoid strains of Burkholderia cepacia. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 185:243-246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chiang, S. L., and J. J. Mekalanos. 1998. Use of signature-tagged transposon mutagenesis to identify Vibrio cholerae genes critical for colonization. Mol. Microbiol. 27:797-805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chung, J. W., E. Altman, T. J. Beveridge, and D. P. Speert. 2003. Colonial morphology of Burkholderia cepacia complex genomovar III: implications in exopolysaccharide production, pilus expression, and persistence in the mouse. Infect. Immun. 71:904-909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coenye, T., and P. Vandamme. 2003. Diversity and significance of Burkholderia species occupying diverse ecological niches. Environ. Microbiol. 5:719-729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Condon, C., D. Liveris, C. Squires, I. Schwartz, and C. L. Squires. 1995. rRNA operon multiplicity in Escherichia coli and the physiological implications of rrn inactivation. J. Bacteriol. 177:4152-4156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Corbett, C. R., M. N. Burtnick, C. Kooi, D. E. Woods, and P. Sokol. 2003. An extracellular zinc metalloprotease gene of Burkholderia cepacia. Microbiology 149:2263-2271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Corey, M., and V. Farewell. 1996. Determinants of mortality from cystic fibrosis in Canada, 1970-1989. Am. J. Epidemiol. 143:1007-1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Coulter, S. N., W. R. Schwan, E. Y. Ng, M. H. Langhorne, H. D. Ritchie, S. Westbrock-Wadman, W. O. Hufnagle, K. R. Folger, A. S. Bayer, and C. K. Stover. 1998. Staphylococcus aureus genetic loci impacting growth and survival in multiple infection environments. Mol. Microbiol. 30:393-404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Craig, F. F., J. G. Coote, R. Parton, J. H. Freer, and N. J. Gilmour. 1989. A plasmid which can be transferred between Escherichia coli and Pasteurella haemolytica by electroporation and conjugation. J. Gen. Microbiol. 135:2885-2890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Darling, P., M. Chan, A. D. Cox, and P. A. Sokol. 1998. Siderophore production by cystic fibrosis isolates of Burkholderia cepacia. Infect. Immun. 66:874-877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Darwin, A. J., and V. L. Miller. 1999. Identification of Yersinia enterocolitica genes affecting survival in an animal host using signature-tagged transposon mutagenesis. Mol. Microbiol. 32:51-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dennis, J. J., and G. J. Zylstra. 1998. Plasposons: modular self-cloning minitransposon derivatives for rapid genetic analysis of gram-negative bacterial genomes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:2710-2715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fehlner-Gardiner, C. C., T. M. Hopkins, and M. A. Valvano. 2002. Identification of a general secretory pathway in a human isolate of Burkholderia vietnamiensis (formerly B. cepacia complex genomovar V) that is required for the secretion of hemolysin and phospholipase C activities. Microb. Pathog. 32:249-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fehlner-Gardiner, C. C., and M. A. Valvano. 2002. Cloning and characterization of the Burkholderia vietnamiensis norM gene encoding a multi-drug efflux protein. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 215:279-283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Figurski, D. H., and D. R. Helinski. 1979. Replication of an origin-containing derivative of plasmid RK2 dependent on a plasmid function provided in trans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 76:1648-1652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Govan, J. R., P. H. Brown, J. Maddison, C. J. Doherty, J. W. Nelson, M. Dodd, A. P. Greening, and A. K. Webb. 1993. Evidence for transmission of Pseudomonas cepacia by social contact in cystic fibrosis. Lancet 342:15-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Govan, J. R., and V. Deretic. 1996. Microbial pathogenesis in cystic fibrosis: mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Burkholderia cepacia. Microbiol. Rev. 60:539-574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Govan, J. R., J. E. Hughes, and P. Vandamme. 1996. Burkholderia cepacia: medical, taxonomic and ecological issues. J. Med. Microbiol. 45:395-407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guy, G. R., R. Philip, and Y. H. Tan. 1994. Analysis of cellular phosphoproteins by two-dimensional gel electrophoresis: applications for cell signaling in normal and cancer cells. Electrophoresis 15:417-440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hayes, F. 2003. Toxins-antitoxins: plasmid maintenance, programmed cell death, and cell cycle arrest. Science 301:1496-1499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Henry, D. A., M. E. Campbell, J. J. LiPuma, and D. P. Speert. 1997. Identification of Burkholderia cepacia isolates from patients with cystic fibrosis and use of a simple new selective medium. J. Clin. Microbiol. 35:614-619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hensel, M., J. E. Shea, C. Gleeson, M. D. Jones, E. Dalton, and D. W. Holden. 1995. Simultaneous identification of bacterial virulence genes by negative selection. Science 269:400-403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hutchison, M. L., I. R. Poxton, and J. R. Govan. 1998. Burkholderia cepacia produces a hemolysin that is capable of inducing apoptosis and degranulation of mammalian phagocytes. Infect. Immun. 66:2033-2039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Isles, A., I. Maclusky, M. Corey, R. Gold, C. Prober, P. Fleming, and H. Levison. 1984. Pseudomonas cepacia infection in cystic fibrosis: an emerging problem. J. Pediatr. 104:206-210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jarvis, W. R., D. Olson, O. Tablan, and W. J. Martone. 1987. The epidemiology of nosocomial Pseudomonas cepacia infections: endemic infections. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 3:233-236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Johnson, W. M. 1994. Intercontinental spread of a highly transmissible clone of Pseudomonas cepacia proved by multilocus enzyme electrophoresis and ribotyping. Can. J. Infect. Dis. 5:86-88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Karlyshev, A. V., P. C. Oyston, K. Williams, G. C. Clark, R. W. Titball, E. A. Winzeler, and B. W. Wren. 2001. Application of high-density array-based signature-tagged mutagenesis to discover novel Yersinia virulence-associated genes. Infect. Immun. 69:7810-7819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Keig, P. M., E. Ingham, and K. G. Kerr. 2001. Invasion of human type II pneumocytes by Burkholderia cepacia. Microb. Pathog. 30:167-170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Köthe, M., M. Antl, B. Huber, K. Stoecker, D. Ebrecht, I. Steinmetz, and L. Eberl. 2003. Killing of Caenorhabditis elegans by Burkholderia cepacia is controlled by the cep quorum-sensing system. Cell. Microbiol. 5:343-351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee, B. C. 1995. Quelling the red menace: haem capture by bacteria. Mol. Microbiol. 18:383-390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lefebre, M., and M. Valvano. 2001. In vitro resistance of Burkholderia cepacia complex isolates to reactive oxygen species in relation to catalase and superoxide dismutase production. Microbiology 147:97-109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lefebre, M. D., and M. A. Valvano. 2002. Construction and evaluation of plasmid vectors optimized for constitutive and regulated gene expression in Burkholderia cepacia complex isolates. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:5956-5964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lehoux, D. E., F. Sanschagrin, and R. C. Levesque. 1999. Defined oligonucleotide tag pools and PCR screening in signature-tagged mutagenesis of essential genes from bacteria. BioTechniques 26:473-478, 480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lewenza, S., B. Conway, E. P. Greenberg, and P. A. Sokol. 1999. Quorum sensing in Burkholderia cepacia: identification of the LuxRI homologs CepRI. J. Bacteriol. 181:748-756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.LiPuma, J. J., S. E. Dasen, D. W. Nielson, R. C. Stern, and T. L. Stull. 1990. Person-to-person transmission of Pseudomonas cepacia between patients with cystic fibrosis. Lancet 336:1094-1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lutter, E., S. Lewenza, J. J. Dennis, M. B. Visser, and P. A. Sokol. 2001. Distribution of quorum-sensing genes in the Burkholderia cepacia complex. Infect. Immun. 69:4661-4666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mahenthiralingam, E., T. Coenye, J. W. Chung, D. P. Speert, J. R. Govan, P. Taylor, and P. Vandamme. 2000. Diagnostically and experimentally useful panel of strains from the Burkholderia cepacia complex. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:910-913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Marolda, C. L., B. Hauröder, M. A. John, R. Michel, and M. A. Valvano. 1999. Intracellular survival and saprophytic growth of isolates from the Burkholderia cepacia complex in free-living amoebae. Microbiology 145:1509-1517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Maroncle, N., D. Balestrino, C. Rich, and C. Forestier. 2002. Identification of Klebsiella pneumoniae genes involved in intestinal colonization and adhesion using signature-tagged mutagenesis. Infect. Immun. 70:4729-4734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Martin, D. W., and C. D. Mohr. 2000. Invasion and intracellular survival of Burkholderia cepacia. Infect. Immun. 68:24-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.McKevitt, A. I., S. Bajaksouzian, J. D. Klinger, and D. E. Woods. 1989. Purification and characterization of an extracellular protease from Pseudomonas cepacia. Infect. Immun. 57:771-778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mecsas, J. 2002. Use of signature-tagged mutagenesis in pathogenesis studies. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 5:33-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nzula, S., P. Vandamme, and J. R. Govan. 2002. Influence of taxonomic status on the in vitro antimicrobial susceptibility of the Burkholderia cepacia complex. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 50:265-269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Parsons, Y. N., K. J. Glendinning, V. Thornton, B. A. Hales, C. A. Hart, and C. Winstanley. 2001. A putative type III secretion gene cluster is widely distributed in the Burkholderia cepacia complex but absent from genomovar I. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 203:103-108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pegues, C. F., D. A. Pegues, D. S. Ford, P. L. Hibberd, L. A. Carson, C. M. Raine, and D. C. Hooper. 1996. Burkholderia cepacia respiratory tract acquisition: epidemiology and molecular characterization of a large nosocomial outbreak. Epidemiol. Infect. 116:309-317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pegues, D. A., L. A. Carson, O. C. Tablan, S. C. FitzSimmons, S. B. Roman, J. M. Miller, W. R. Jarvis, et al. 1994. Acquisition of Pseudomonas cepacia at summer camps for patients with cystic fibrosis. J. Pediatr. 124:694-702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Perry, R. D. 1999. Signature-tagged mutagenesis and the hunt for virulence factors. Trends Microbiol. 7:385-389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Poole, K. 2001. Multidrug efflux pumps and antimicrobial resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa and related organisms. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 3:255-264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Prince, A. 1986. Antibiotic resistance of Pseudomonas species. J. Pediatr. 108:830-834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Saini, L. S., S. B. Galsworthy, M. A. John, and M. A. Valvano. 1999. Intracellular survival of Burkholderia cepacia complex isolates in the presence of macrophage cell activation. Microbiology 145:3465-3475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sajjan, U. S., L. Sun, R. Goldstein, and J. F. Forstner. 1995. Cable (Cbl) type II pili of cystic fibrosis-associated Burkholderia (Pseudomonas) cepacia: nucleotide sequence of the cblA major subunit pilin gene and novel morphology of the assembled appendage fibers. J. Bacteriol. 177:1030-1038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sha, J., E. V. Kozlova, A. A. Fadl, J. P. Olano, C. W. Houston, J. W. Peterson, and A. K. Chopra. 2004. Molecular characterization of a glucose-inhibited division gene, gidA, that regulates cytotoxic enterotoxin of Aeromonas hydrophila. Infect. Immun. 72:1084-1095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Smalley, J. W., A. J. Birss, and J. Silver. 2000. The periodontal pathogen Porphyromonas gingivalis harnesses the chemistry of the μ-oxo bishaem of iron protoporphyrin IX to protect against hydrogen peroxide. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 183:159-164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Smalley, J. W., P. Charalabous, A. J. Birss, and C. A. Hart. 2001. Detection of heme-binding proteins in epidemic strains of Burkholderia cepacia. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 8:509-514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sokol, P. A., P. Darling, D. E. Woods, E. Mahenthiralingam, and C. Kooi. 1999. Role of ornibactin biosynthesis in the virulence of Burkholderia cepacia: characterization of pvdA, the gene encoding l-ornithine N5-oxygenase. Infect. Immun. 67:4443-4455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Speert, D. P., D. Henry, P. Vandamme, M. Corey, and E. Mahenthiralingam. 2002. Epidemiology of Burkholderia cepacia complex in patients with cystic fibrosis, Canada. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 8:181-187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Struve, C., C. Forestier, and K. A. Krogfelt. 2003. Application of a novel multi-screening signature-tagged mutagenesis assay for identification of Klebsiella pneumoniae genes essential in colonization and infection. Microbiology 149:167-176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tomich, M., A. Griffith, C. A. Herfst, J. L. Burns, and C. D. Mohr. 2003. Attenuated virulence of a Burkholderia cepacia type III secretion mutant in a murine model of infection. Infect. Immun. 71:1405-1415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tomich, M., C. A. Herfst, J. W. Golden, and C. D. Mohr. 2002. Role of flagella in host cell invasion by Burkholderia cepacia. Infect. Immun. 70:1799-1806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tomlin, K. L., O. P. Coll, and H. Ceri. 2001. Interspecies biofilms of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Burkholderia cepacia. Can. J. Microbiol. 47:949-954. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Vandamme, P., B. Holmes, M. Vancanneyt, T. Coenye, B. Hoste, R. Coopman, H. Revets, S. Lauwers, M. Gillis, K. Kersters, and J. R. Govan. 1997. Occurrence of multiple genomovars of Burkholderia cepacia in cystic fibrosis patients and proposal of Burkholderia multivorans sp. nov. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 47:1188-1200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Vasil, M. L., D. P. Krieg, J. S. Kuhns, J. W. Ogle, V. D. Shortridge, R. M. Ostroff, and A. I. Vasil. 1990. Molecular analysis of hemolytic and phospholipase C activities of Pseudomonas cepacia. Infect. Immun. 58:4020-4029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Vogel, H. J., and D. M. Bonner. 1956. Acetylornithase of Escherichia coli: partial purification and some properties. J. Biol. Chem. 218:97-106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yanisch-Perron, C., J. Vieira, and J. Messing. 1985. Improved M13 phage cloning vectors and host strains: nucleotide sequences of the M13mp18 and pUC19 vectors. Gene 33:103-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zughaier, S. M., H. C. Ryley, and S. K. Jackson. 1999. A melanin pigment purified from an epidemic strain of Burkholderia cepacia attenuates monocyte respiratory burst activity by scavenging superoxide anion. Infect. Immun. 67:908-913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]