Abstract

Identifying who among problem drinkers is best suited for moderation and has the greatest likelihood to control drinking has important public health implications. The current study aimed to identify profiles of problem drinkers who may be more or less successful in moderating drinking within the context of a randomized clinical trial of a brief treatment for alcohol use disorder. A person-centered approach was implemented, utilizing composite, baseline daily diary values of confidence and commitment to reduce drinking. Problem drinkers (N=89) were assessed, provided feedback about their drinking, and randomly assigned to one of three conditions: two brief AUD treatments or a third group asked to change on their own. Global self-report assessments were administered at baseline and week 8 (end of treatment). Daily diary composites were created from data collected via an Interactive Voice Recording system during the week prior to baseline. A K-means cluster analysis identified three groups: High, Moderate, and Low confidence and commitment to change drinking. Group differences were explored, and then group membership was entered into generalized estimating equations (GEE) to predict drinking trajectories over time. Findings revealed that the groups differentially reduced their drinking, such that the High group had greater reduction in drinking and a faster rate of reduction than the other two groups, and the Moderate group had greater reduction than the Low group. Findings suggest that baseline motivation and self-efficacy are important to predicting prognoses related to successful moderated drinking. Limitations and arenas for future research are discussed.

Keywords: moderation, controlled drinking, alcohol, problem drinkers, motivation, self-efficacy, person-centered approach, ecological momentary assessment

Alcohol use disorders (AUD) are highly prevalent and a costly public health problem (Department of Health and Human Services, 2000). Among those with AUD, problem drinkers make up an estimated 16% of drinkers (Dawson et al., 2005; National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, 2013a) and are characterized by mild-to-moderate alcohol problem severity, low rates of co-morbid disorders, and a higher level of psychosocial functioning than those with severe alcohol dependence (Hester, 1995). Problem drinkers generally prefer moderation rather than abstinence as a treatment goal, and evidence suggests that moderation is a viable and achievable goal for problem drinkers, both within (Saladin & Santa Ana, 2004; Walters, 2000) and outside of (L. C. Sobell, Ellingstad, & Sobell, 2000) AUD treatment (Kuerbis, Morgenstern, & Hail, 2012).

Despite having success rates with moderation on par with abstinence based treatments, many problem drinkers maintain or return to problematic drinking (e.g., Ilgen, Wilbourne, Moos, & Moos, 2008; Mendoza, Walitzer, & Connors, 2012; Mertens, Kline-Simon, Delucchi, Moore, & Weisner, 2012; Morgenstern et al., 2007; Morgenstern, Kuerbis, Amrhein, et al., 2012; Morgenstern, Kuerbis, Chen, et al., 2012). Therefore identifying who among problem drinkers is best suited for moderation and has the greatest likelihood to control drinking has important public health implications. Creating profiles can offer a number of advantages, as they can: can help to determine short-term and long-term prognoses for treatment; can be utilized by clinicians to successfully facilitate the goal setting process; can help to select appropriate treatment approaches; and can potentially determine how to tailor treatments for optimal outcomes.

Research on Drinkers who Successfully Moderate

Clear profiles of individuals who can successfully moderate have yet to fully emerge. Demographics, such as age and education, have yielded mixed findings (Kuerbis et al., 2012; Rosenberg, 1993). Two of the most consistent predictors of successfully moderating are goal choice (choosing moderation as a goal versus abstinence) (Adamson & Sellman, 2001; Al-Otaiba, Worden, McCrady, & Epstein, 2008; Bujarski, O'Malley, Lunny, & Ray, 2013; Rosenberg, 1993) and drinking and drinking problem severity (the greater the severity leading to inability to moderate or to relapse) (Ambrogne, 2002; Cunningham, 1999; Kuerbis et al., 2012; Mertens et al., 2012). Other factors with initial empirical support are: belief in the possibility of moderation (Heather, Rollnick, & Winton, 1983; Rosenberg, 1993), a greater sensitivity to longer-term consequences of drinking (e.g., an individual’s ability to allocate money to savings rather than drinking) (Tucker, Vuchinich, Black, & Rippens, 2006), and impaired control (Heather & Dawe, 2005). Surprisingly absent from this literature are findings that motivation and self-efficacy at baseline identify profiles of individuals with the best prognoses for moderation.

Motivation and Self-Efficacy as Profile Factors

Widely applied theories of change, such as social cognitive theory (Bandura, 1977; Bargh, Gollwitzer, & Oettingen, 2010) and the transtheoretical model (Prochaska, DiClemente, & Norcross, 1992), posit that both motivation (often defined as readiness for, desire, reason, need, intention or commitment to change, DiClemente, Schlundt, & Gemmell, 2004) and self-efficacy (also defined as belief in one's ability or confidence, Bandura, 1977, 1982) to change are necessary for successful and maintained behavior change. As a result, both constructs have been extensively researched as mechanisms of change in the abstinence-based addiction treatment literature and are demonstrated predictors of substance use and other addictive behavior outcomes, with self-efficacy as a more consistent predictor than motivation (Amrhein, Miller, Yahne, Palmer, & Fulcher, 2003; Apodaca & Longabaugh, 2009; Brown, Seraganian, Tremblay, & Annis, 2002; Campbell, Adamson, & Carter, 2010; Heather, McCambridge, & Ukatt Research Team, 2013; Hodgins, Ching, & McEwen, 2009; Kelly, Magill, & Stout, 2009; Kuerbis, Armeli, Muench, & Morgenstern, 2013; Litt, Kadden, Cooney, & Kabela, 2003; Moyers, Martin, Houck, Christopher, & Tonigan, 2009; Project MATCH Research Group, 1997, 1998; Witkiewitz, Hartzler, & Donovan, 2010). In cases where profiles have been identified, it has been useful in helping to determining differential treatment efficacy (e.g., Witkiewitz et al., 2010), such that those with low motivation are better helped by motivational enhancement therapy than cognitive behavioral therapy or 12-step facilitation. In two studies, using both motivation and self-efficacy to define profiles successfully predicted long term drinking outcomes (Carbonari & DiClemente, 2000; DiClemente & Huges, 1990).

Despite the prominence of these constructs in the abstinence-based literature, very few studies have examined them with respect to controlled or moderated drinking (e.g., Miller & Munoz, 2005; Rosenberg, 1993). In one of the few studies to examine motivation in the context of moderation, Campbell and colleagues (2010) demonstrated that strength of in-session client commitment statements significantly predicted reduced drinking within and across four sessions of a motivational interviewing intervention. While some studies provide support for higher self-efficacy predicting moderated drinking outcomes, which often includes some abstinence (Campbell et al., 2010; Connors & Walitzer, 2001; Moos & Moos, 2006; Sitharthan, Job, Kavanagh, Sitharthan, & Hough, 2003; Sitharthan & Kavanagh, 1990; Sitharthan, Kavanagh, & Sayer, 1996), there are also studies that show little to no relationship when controlling for other factors (e.g., Kavanagh, Sitharthan, & Sayer, 1996; Tucker et al., 2006). Guidelines for baseline levels of motivation and self-efficacy that predict successful and sustained moderation have yet to be identified. To our knowledge, no studies have examined them as potential contributors to profiles of individuals who can successfully moderate.

Issue of Measurement

A potential limiting factor in identifying profiles based on baseline motivation and self-efficacy is the use of global self-report measures—the historical gold standard for measuring both these constructs. Global self-report measures, such as the Readiness to Change Questionnaire (RCQ, Heather & Rollnick, 2000) and the Situational Confidence Questionnaire (SCQ, Annis & Graham, 1988), are often administered at a single time point. Vague, hypothetical scenarios and statements (devoid of much context) are described, and participants respond to how much those scenarios or statements reflects their experience. Theories of addiction describe motivation and self-efficacy as context-specific—in relation to both environment and time. Global self-report measures that remain anchored in time or do not provide adequate context to a scenario potentially provide an invalid or inadequate frame of reference for measurement.

Ecological momentary assessment (EMA) can address this limitation by evaluating individuals in context. EMA is a methodology defined as “repeated collection of real-time data on subjects’ behavior and experience in their natural environment” (Shiffman, Stone, & Hufford, 2008, p. 3), and the term is used here to encompass all methods that fall under daily process or micro-longitudinal designs in which constructs are assessed daily (or more intensely) in daily life. This unique approach has the ability to capture the motivation and self-efficacy in context over time—thus providing a more accurate measurement of these two constructs. By measuring constructs in context, it has the potential to eliminate retrospective bias, a common limitation of global self report measures (Shiffman et al., 2008), which enhances the validity of the measurement. The result is that even a composite variable created from daily diary data could be a more reliable and valid measure of these constructs than a global self report measure.

In a previous study, baseline global self-report and composite daily diary measures of confidence and commitment to change were compared in their ability to predict drinking outcomes in a pilot randomized clinical trial of brief moderation-focused treatment for problem drinkers (Kuerbis et al., 2013). The purpose of the study was to understand the unique contributions of each measurement type to yield information about participants’ change trajectories and drinking outcomes. For the composite daily diary measure, participants were asked three questions about their confidence and commitment to change on a daily basis for seven days prior to the baseline visit, and their responses were averaged to yield a composite score. Global self-report measures were standardized, well-validated measures administered at a single time point at the baseline visit. Results demonstrated that baseline composite, daily diary measures predicted end of treatment outcomes, whereas global self-report measures did not, even when controlling for receipt of treatment.

The Current Study

The current exploratory study was implemented in response to the aforementioned gaps in the literature: the limited research delineating profiles of individuals who can successfully moderate, the theoretical stance that both motivation and self-efficacy together are crucial to change, and the absence of identifying profiles of individuals based on both motivation and self efficacy. The aim of this study was to explore whether and how baseline composite daily diary values of confidence and commitment to reduce drinking identify profiles of individuals who may be more or less successful in moderating drinking using a person-centered approach.

METHOD

This study is a secondary data analysis of data collected from a pilot study of 89 problem drinkers interested in moderation recruited to participate in a randomized controlled trial for a brief intervention for AUD. Detailed procedures are reported elsewhere (Morgenstern, Kuerbis, Amrhein, et al., 2012) and reviewed here briefly. The pilot’s aim was to test the mechanisms of action with Motivational Interviewing (MI) by disaggregating the intervention into its relational (client-counselor relationship with unique therapist stance) and directive (technical strategies) elements (Miller & Rose, 2009). Results of the original study demonstrated no condition differences on end of treatment drinking outcomes, even when therapy conditions were aggregated and compared to a self-monitoring condition (Morgenstern, Kuerbis, Amrhein, et al., 2012).

Participants

Recruitment

Online and local media advertising was used to recruit 89 participants seeking to reduce but not quit drinking. Advertisements emphasized client choice and a moderation approach. Participants were initially screened on the phone and, if eligible, were scheduled for an in-person screen assessment.

Study eligibility

Participants were eligible if they were: (1) between ages 18 and 65; (2) consumed an estimated weekly average of greater than 15 or 24 standard drinks per week for women and men, respectively, during the prior 8 weeks, and (3) had a current AUD. Participants were excluded if they had: (1) had a substance use disorder (for any substance other than alcohol, marijuana, nicotine) or were regular (greater than weekly) drug users; (2) a serious psychiatric disorder or suicide or violence risk; (3) physical withdrawal symptoms or reported a history of serious withdrawal symptoms; (4) a legal mandate to substance abuse treatment; (5) social instability (e.g., homeless); (6) a desire to achieve abstinence at baseline; or (7) a desire or intent to pursue additional substance abuse treatment during the eight week study period .

Procedures

Eligible participants completed a baseline assessment one week after the screen assessment. Participants were then randomly assigned to one of three conditions: MI, Spirit Only MI (SOMI), and Self Change (SC), described further below. Participants assigned to either MI or SOMI received four sessions of psychotherapy over seven weeks. Those in the SC condition were encouraged to change on their own, and, at the end of the seven-week treatment period, they were offered four sessions of MI. All participants completed a Week 8 (end of treatment) assessment.

Daily Diary: Daily Interactive Voice Recording Survey

In addition to standard assessments, participants responded to a 2–5 minute daily survey delivered via interactive voice recording (IVR, TELESAGE, 2005) at the end of each day for a total of eight weeks—one week prior to the baseline assessment/randomization through the end of the seven week treatment period. Participants were asked to complete the survey between 4:00 pm and 10:00 p.m. If participants failed to call into the system by 8:00 p.m., an automated reminder call was made.

Study Interventions

All participants received normative feedback from a member of the research staff during their baseline assessment immediately prior to randomization. Feedback included an estimated average weekly consumption of alcohol and their score from the Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test (AUDIT, Babor, Higgins-Biddle, Saunders, & Monteiro, 2001) with a description of AUDIT risk categories. They were then assigned to one of the conditions described below. There was high fidelity to conditions and clear discriminability between conditions (Morgenstern, Kuerbis, Amrhein, et al., 2012). All goals within treatment were geared towards moderation rather than abstinence.

Motivational Interviewing (MI)

The MI protocol was adapted from the motivational enhancement therapy used in Project MATCH (Miller, Zweben, DiClemente, & Rychtarik, 1992; Project MATCH Research Group, 1993) and included structured personalized feedback.

Spirit only MI (SOMI)

The SOMI protocol consisted of the relational elements of MI, specifically: therapist stance (warmth, genuineness, egalitarianism), emphasis on client responsibility for change, use of reflective listening skills focused on client affect, and avoidance of MI-inconsistent behaviors. Technical or directive elements (e.g., amplified or double-sided reflections) were proscribed to avoid the selective reinforcement of change talk.

Self Change (SC)

The SC protocol emphasized personal responsibility for change. Participants were asked to attempt to change on their own and told that research shows some individuals reduce drinking without professional help. Participants were offered treatment (four sessions of MI) at the end of the Week 8 assessment.

Measures

Screening and substance use diagnosis

The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test-C (AUDIT-C) was used to determine preliminary eligibility for the study in regards to quantity and frequency of drinking, and it has demonstrated adequate psychometric properties (Bush, Kivlahan, & McDonell, 1998). The Composite International Diagnostic Instrument, Substance Abuse Module (Cottler, Robins, & Helzer, 1989) was used to evaluate substance dependence exclusion criteria and the number of AUD criteria a participant satisfied. It is a well-established diagnostic interview with excellent reliability and validity (Wittchen et al., 1991). Number of DSM-IV dependence criteria satisfied were summed into in a continuous score.

Variables on Which Clusters were Based

Commitment to reduce drinking or abstain

Two items on the daily diary IVR questionnaire measured commitment to change. The first was “How committed are you not to drink heavily (that is, not to drink more than 5 drinks) over the next 24 hours?”, and the second was “How committed are you not to drink at all over the next 24 hours?” The response set for the items ranged from 0 “not at all” to 4 “totally.” It is important that, for women, drinking heavily was specified as “no more than 4 drinks.”

Confidence to reduce drinking

One item on the daily diary IVR questionnaire measured confidence to change. The participant was asked “How confident are you that you can resist drinking heavily (that is, resist drinking more than 5 drinks) over the next 24 hours?” Responses ranged from 0 “not at all” to 4 “totally.” For women, drinking heavily was specified as “no more than 4 drinks.”

Variables Used for Comparing Cluster Groups

Sociodemographics

A self-report, demographic questionnaire collected data on age, gender, educational and occupational information, race and ethnicity, medical history, family psychiatric and substance abuse history, and the participant’s substance abuse treatment history.

AUD symptoms, risks, and problems

In order to assess the approximate level of genetic risk for alcohol dependence, participants reported the number of relatives with an alcohol or drug problem, with parents or siblings scored as two points and all others scored with one, yielding a cumulative sum score.

The AUDIT-C (described above, Bush et al., 1998) was used to indicate particularly heavy drinkers among this problem drinking sample. Those who scored 12 (the maximum score) on the AUDIT-C were categorized as heavy problem drinkers.

Severity of AUD was measured using the Alcohol Dependence Scale (ADS, Skinner & Allen, 1982). The ADS is a 25 item self report measure of various symptoms and intensity of alcohol dependence as defined by the DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). It demonstrates strong reliability and validity across studies and populations (Kahler, Strong, Hayaki, Ramsey, & Brown, 2003; Skinner & Horn, 1984). For this study, internal consistency was adequate (Cronbach’s alpha = .73).

The Short Inventory of Problems (SIP, Miller, Tonigan, & Longabaugh, 1995) is a 15-item self-report measure of lifetime or past three months’ negative consequences of drinking. The SIP has demonstrated strong psychometric properties (Kenna et al., 2005) and for this sample yielded strong reliability (Cronbach’s alpha=.87).

An adapted, 10-item version of the Obsessive Compulsive Drinking Scale (OCDS, Anton, 2000; Morgan, Morgenstern, Blanchard, Labouvie, & Bux, 2004) was used to measure obsessionality and compulsivity of craving and drinking behavior. The scale demonstrated strong reliability within this sample (Cronbach’s alpha of .79).

The Readiness to Change Questionnaire (RCQ, Heather & Rollnick, 2000) is a 12-item instrument for measuring “stage of change” of the participant in changing his or her drinking. The RCQ has demonstrated good psychometric properties including predictive validity, and it consists of three subscales: precontemplation, contemplation, and action. For the purposes of this study, we utilized the action subscale, and its internal consistency was strong (Cronbach’s alpha=.81).

Coping

The Processes of Change Scale-27 (POC) is an adapted version (Morgenstern, Labouvie, McCrady, Kahler, & Frey, 1997) of the 40-item self-report measure assessing frequency of coping strategies for avoiding heavy drinking. This 27 item scale uses a 5-point Likert scale response set, with strongly agree and strongly disagree as anchors. The POC contains two subscales that delineate different forms of coping: cognitive and behavioral. With this sample, Cronbach’s alpha was .83 for the behavioral subscale and .85 for the cognitive subscale.

Self-efficacy

The Situational Confidence Questionnaire (SCQ, Annis & Davis, 1988) is a 39-item questionnaire that measures self efficacy related to drinking behavior, specifically the ability to resist the urge to drink heavily. Internal consistency for this scale with this sample was very strong (Cronbach’s alpha = .95). For this analysis, a total composite score was utilized by summing the scores of each of the items.

Past treatment

Participants were asked whether they had ever received any type of formal treatment for AUD in their lifetime. This was a dichotomous variable, with answers yes and no.

Symptoms of depression and anxiety

Depressive symptoms were measured using the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI, Beck, Steer, & Brown, 1996). The BDI is a self-report, 21-item questionnaire, which yields a continuous score, ranging from 0 to 63. Mild depression is indicated starting at 14 and severe depression at 29. Internal consistency of the BDI-II for this sample was very strong (Cronbach’s alpha = .90). Anxiety symptoms were assessed using the state subscale of the Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI, Spielberger, 1983). The STAI State Subscale is a 20-item scale that assesses temporary anxiety symptoms. Trait items were excluded. For the purposes of this analysis, only the items indicating the presence of anxiety (as opposed to the absence) were used. These ten items were summed for a total continuous score. Internal consistency of the scale was very strong in this sample, with a Cronbach’s alpha of .91.

Alcohol use outcomes

For this analysis, alcohol use patterns were measured using the Timeline Followback interview (TLFB, M. B. Sobell et al., 1980). It assessed frequency and quantity of alcohol use during the nine weeks prior to baseline/randomization, and it was also administered at the end of treatment assessment (at week 8). The TLFB has demonstrated good test-retest reliability (Carey, Carey, Maisto, & Henson, 2004), agreement with collateral reports of alcohol (Dillon, Turner, Robbins, & Szapocznik, 2005), convergent validity, and reliability across mode of administration (i.e., in person or over the phone) (Vinson, Reidinger, & Wilcosky, 2003). For this analysis, TLFB data was aggregated into summary variables that described frequency and intensity of drinking on a weekly basis, including the 9 weeks pre-treatment and the 7 weeks during treatment. Aggregate variables included mean sum of standard drinks (SSD), number of drinking days (NDD), and drinks per drinking day (DDD). These variables were created to facilitate comparison with guidelines for safe drinking from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) and for specificity with respect to the changes in drinking patterns—information particularly important in the context of moderated drinking.

Analytic Plan

This analysis combined person-centered and variable-centered approaches (Laursen & Hoff, 2006). The first step of the analysis was to create composites of daily reports of confidence to resist heavy drinking, commitment not to drink heavily and commitment not to drink at all. Each item was aggregated across the week prior to the baseline assessment to form three mean level composites for each person. Composites were created in order to reduce error and increase reliability of the measures, and reliability estimates of these baseline composites and their correlation with one another were reported elsewhere (Kuerbis et al., 2013). Reliability coefficients are reproduced here for ease of reference (Table 1). It is important to note that the composites were based on a mean of 5.27 (SD = 2.00; Median = 6.00) reporting days per person in the week prior to baseline. In order to eliminate any undue influence that greater or lesser compliance with the IVR might have on model results, all individuals missing more than three days of data in the week were excluded. The sample size for this analysis was N=84.

Table 1.

Non-standardized descriptives of variables used to create cluster groups

| Composite Variable | Cluster Group | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reliability Coefficient |

Low (N=33) M (SD) |

Moderate (N=38) M (SD) |

High (N=12) M (SD) |

(N=84) M (SD) |

|

| Confidence to not drink heavily | .74 | 1.2 (.55) | 2.7 (.62) | 2.9 (.86) | 2.2 (.96) |

| Commitment to not drink heavily | .76 | 1.4 (.57) | 2.7 (.65) | 3.2 (.65) | 2.3 (.95) |

| Commitment to not drink at all | .75 | .40 (.41) | .86 (.57) | 2.5 (.73) | .94 (.88) |

Next, composite scores were standardized into z scores to equate the item variances (Aldenderfer & Blashfield, 1984). Using the standardized composites, K means cluster analysis was performed to identify cluster groups. K-means cluster analysis offered certain advantages to other cluster analysis methods, such as hierarchical agglomerative methods, in that clusters are mutually exclusive and it minimizes the variance within each cluster (Aldenderfer & Blashfield, 1984). Based on the profile literature above (e.g., DiClemente & Huges, 1990), the procedure was performed repeatedly by first specifying three and then up to six classes. The results yielding between four and six clusters had fewer than 3 cases in some of the cluster groups, suggesting poor cluster partitioning. Ultimately, the analyses revealed that three clusters yielded the most informative and clinically relevant profiles, which were then further validated, as required (Garson, 2012), by the next step in the analysis. Using cluster membership, descriptive statistics were generated across demographics (age, gender, education, income, employment, and relationship status), psychiatric scales (for depression and anxiety), and variables related to alcohol use and patterns of use to identify other attributes or behavioral markers of cluster membership. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and chi-square tests were used for continuous and categorical variables respectively.

In the final stage of the analysis and cluster verification, cluster membership was entered as a predictor of weekly drinking using generalized estimating equations (GEE, Liang and Zeger, 1986), controlling for baseline drinking and time. First, clusters were Helmert contrast coded to compare outcomes across clusters. GEE were then used to analyze the non-normal, longitudinal data for each of the dependent variables (SSD, NDD, and DDD). Next, interaction terms (cluster group x time) were entered into the models to test for differences in rates of reduction. For this analysis, a Poisson distribution with log link function was specified for NDD, and a negative binomial distribution with logit link function was specified for SSD and DDD. These distribution specifications were chosen based on distributions (e.g., for NDD, variance was less than the mean) of the outcome variables, which also provided good model fit for each of the variables respectively, according to the model fit statistics (e.g., QIC, QICu). In addition, an exchangeable working correlation matrix was specified for all models (Stokes et al., 2000). Due to exceedingly small sample sizes, no analyses could be performed on how cluster membership may have moderated treatment efficacy. All analyses were conducted using SAS statistical software program (SAS Institute Inc, 1997).

RESULTS

Clusters Identified

Three clusters were identified in the K-means cluster analysis. For ease of interpretation and clinical application, Table 1 demonstrates the differences on each of the items using non-standardized values. Cluster 1 (n=12) was characterized by high confidence and commitment to change, most notably commitment to not drink at all. This group reported responses well above the mean on all three items and is referred to as the High group. Cluster 2 (n=38) was characterized by moderate confidence and commitment to reduce drinking. While participants in this group reported high confidence and commitment to control their drinking in relation to the sample mean, they reported below the mean on commitment to abstain. This group is referred to as the Moderate group. Cluster 3 (n=33) was characterized by low confidence and commitment to reduce drinking across all items and is referred to as the Low group.

Demographics and Other Characteristics by Cluster Membership

Clusters were compared on demographic variables, alcohol use related scales, coping, past treatment, and symptoms of depression and anxiety (see Table 1). There were no significant demographic differences between the clusters. There were almost no significant differences between clusters in terms of their relationship to alcohol. One exception was the AUDIT-C, in which a far greater proportion in the Low group reported a score of 12, indicating a greater frequency and intensity of drinking than the other two groups (x2(2) = 13.0, p < .01).

Baseline drinking quantity, SSD, differed at the trend level only (F (2, 81) = 2.79, p = .067) between cluster groups. Frequency of drinking, NDD, was significantly different across cluster groups (F(2, 81) = 6.87, p <.01). A post hoc Tamhane’s test was performed due to unequal variance revealing a significant difference between the High group and the other two groups (mean difference compared to Moderate = −1.42, p < .05; mean difference compared to Low = −1.98, p < .001), but there was no significant difference between the Moderate and Low groups (see Table 1). Intensity of drinking, DDD, was not significantly different across cluster groups.

Significant differences also emerged on both the POC behavioral and cognitive subscales (see Table 1). On the behavioral scale (F(2, 80) = 3.97, p < .05), individuals in the High group demonstrated higher scores, indicating greater use of behavioral coping mechanisms than the other two groups. On the cognitive scale (F(2, 80) = 3.12, p < .05), the Low group yielded a significantly lower score than the other two groups, indicating less use of cognitive coping mechanisms. As expected, significant differences emerged on the SCQ (F(2, 80) = 3.57, p < .05), with the Low group demonstrating substantially lower scores, indicating less self-efficacy to not drink heavily.

Significant differences were also found for receipt of AUD treatment in the past (x2(2) = 7.55, p < .05) (see Table 1). Over 33% of individuals in the Low group had received AUD treatment in the past, as compared to 15.4% of the High group and 7.9% of the Moderate group.

There were no significant differences between groups on symptoms of depression or anxiety (see Table 1). All groups had mean scores that demonstrated subclinical level symptoms.

Prediction of Drinking Outcomes

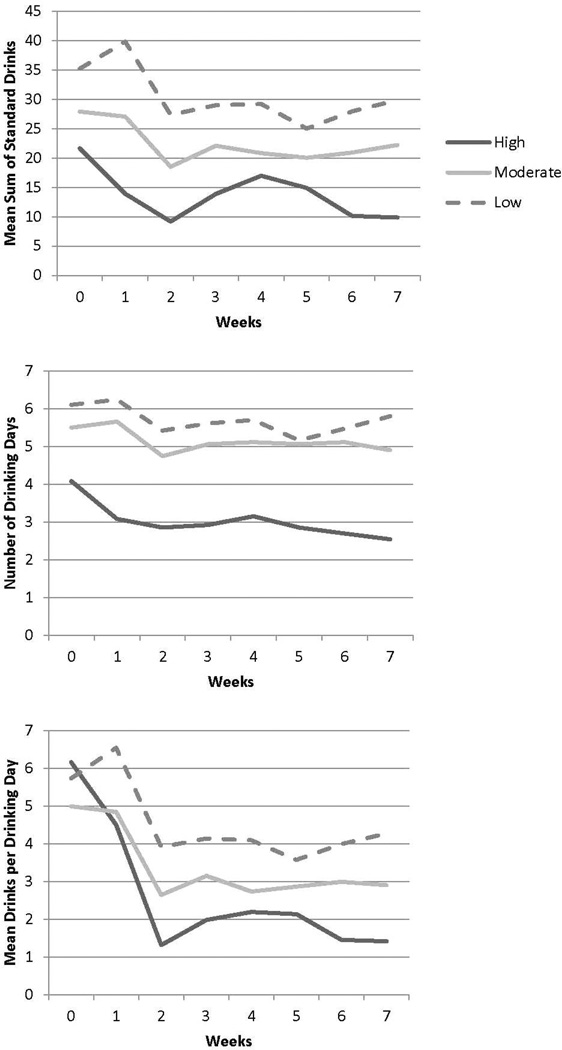

Results from the GEE analyses are provided in Table 2 and displayed graphically in Figure 1. For SSD, both baseline SSD and time were independently significant across all models. Additionally, belonging to the High group predicted a greater reduction in SSD than belonging to either of the other two groups—28% less than the Low group and 20% less than the Moderate group on average. The Low group also demonstrated significantly less reduction in SSD than the Moderate group. Interaction terms (group x time) were not significant for SSD.

Table 2.

Characteristics of cluster groups

| Cluster | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low (N=33) M (SD) or % |

Moderate (N=38) M (SD) or % |

High (N=12) M (SD) or % |

Total (N=84) M (SD) or % |

|

| Demographics | ||||

| Age in years | 42 (13.3) | 39 (11.0) | 37 (8.3) | 39.7 (11.7) |

| Female | 48.5 | 52.6 | 61.5 | 52.4 |

| Education: Some college or more | 87.9 | 100 | 92.3 | 94.0 |

| In a relationship | 39.4 | 55.3 | 53.8 | 48.8 |

| Living with partner | 21.2 | 34.2 | 46.2 | 31.0 |

| Relationship to Alcohol | ||||

| AUDIT-C Score of 12** | 78.8 | 36.8 | 46.2 | 54.8 |

| Total AUDIT Score | 20.9 (4.1) | 19.7 (5.3) | 21.2 (6.4) | 20.4 (5.0) |

| No. of Dependence Criteria | 4.2 (1.6) | 4.0 (1.6) | 3.7 (1.4) | 4.0 (1.6) |

| Genetic risk for AUD | 5.3 (3.9) | 5.1 (4.1) | 8 (5.7) | 5.6 (4.4) |

| Alcohol Dependence Scale | 13.1 (5.6) | 11.8 (5.0) | 13.2 (4.3) | 12.5 (5.1) |

| Short Inventory of Problems | 15.0 (8.3) | 14.2 (6.1) | 16.9 (8.4) | 15.0 (7.4) |

| Obsessive Compulsive Drinking Scale | 13.2 (5.0) | 12.2 (5.0) | 11.3 (5.0) | 12.5 (5.0) |

| RCQ Action Subscale | 12.3 (3.4) | 11.8 (3.6) | 13.1 (3.1) | 12.2 (3.5) |

| Baseline SSDa | 35.2 (19.7) | 27.9 (20.6) | 21.6 (7.7) | 29.8 (19.2) |

| Baseline NDD** | 6.1 (1.3) | 5.5 (1.9) | 4.1 (1.5) | 5.5 (1.7) |

| Baseline DDD | 5.7 (2.6) | 5.0 (3.1) | 6.2 (3.6) | 5.5 (3.0) |

| Coping | ||||

| POC Behavioral Subscale* | 26.9 (7.6) | 27.8 (7.9) | 33.9 (8.0) | 28.4 (8.1) |

| POC Cognitive Subscale* | 31.3 (7.9) | 35.7 (8.4) | 36.8 (9.9) | 34.1 (8.7) |

| Situational Confidence Questionnaire* | 99.3 (29.9) | 118.2 (29.8) | 117.9 (39.1) | 110.6 (32.4) |

| Past treatment* | 33.3 | 7.9 | 15.4 | 19.0 |

| Depression and Anxiety | ||||

| BDI-II Score | 13.5 (9.2) | 13.1 (8.5) | 11.7 (8.1) | 13.0 (8.6) |

| STAI State Presence Score | 15.6 (5.7) | 15.8 (6.2) | 15.7 (6.3) | 15.7 (6.0) |

Note. AUDIT = Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test. AUD = Alcohol Use Disorder. POC= Processes of Change Scale. RCQ Action = Action subscale on the Readiness to Change Questionnaire, Treatment Version. BDI-II = Beck Depression Inventory II. STAI State Presence Score = the 10 items that measure the presence of anxiety on the Spielberger State Trait Anxiety Inventory.

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001

Figure 1.

Trajectories of drinking by cluster

For NDD, both baseline NDD and time were independently significant across all models. Belonging to the High group predicted 20% greater reduction in NDD than belonging to the Low group and a 19% greater reduction in NDD for the Moderate group. The Low group did not demonstrate less reduction in NDD than the Moderate group. Again, the interaction terms (group x time) with time were not significant.

For DDD, baseline DDD and time were both independently significant across all models. Belonging to the High group predicted greater reduction in DDD—30% greater reduction than the Low group and 19% greater reduction than the Moderate group. In this instance, interaction terms with time were significant, such that belonging to the High group predicted a faster rate of reduction in DDD than belonging to either the Moderate or the Low groups. The Low group also demonstrated less reduction in DDD than the Moderate group. The interaction term comparing the rates of reduction for the Moderate and Low groups was not significant.

Post Hoc Analyses

Because confidence and commitment to reduce heavy drinking were highly correlated (r=.79, p<.001, Kuerbis et al., 2013), we repeated these analyses with only the two items related to commitment—both to abstain and to not drink heavily--to determine if the same profiles might be identified. While the K-means cluster again identified three profiles, cluster membership no longer predicted drinking outcomes within the GEE analyses.

DISCUSSION

Overall results from this exploratory study suggest that unique profiles can be identified based on baseline levels of confidence and commitment to reduce or quit drinking as measured by daily diary methods and that these predict drinking trajectories. Furthermore, both questions assessing commitment and confidence were required to predict drinking trajectories. While all three groups lowered their drinking significantly and substantially over the seven week treatment period, there were noticeable differences in how this was accomplished. Individuals clustered in the High group had drinking trajectories such that they drank within NIAAA safety guidelines for drinking by Week 8, whereas the Moderate and Low groups remained drinking beyond safety guidelines. Interestingly, most of the change that occurred to moderate drinking was related to drinking intensity. All three groups were able to lower their DDD substantially from baseline values during the seven week treatment period and in the expected order, with the High group lowering it the most, followed by the Moderate group, and then the Low group the least. Relatively little change occurred in relation to NDD for any of the groups. This suggests that regardless of group, participants attempted to moderate by maintaining their routines in terms of drinking frequency and tried to drink less per episode.

The High group distinguished itself in several ways. In relation to the other two groups, the High cluster group was unique in its relatively high level of commitment to abstain. This can be seen in their NDD—which, on average, was two days fewer than the other two groups. Additionally, the High cluster group had the highest POC behavioral coping score—indicating that compared to the other two groups, individuals in the High group were more likely to implement behavioral tactics to cope with drinking less or not all. It is possible that abstaining at least some days during the week is a specific behavioral tactic used to maintain control over drinking. These attributes suggest an overall lower behavioral severity of AUD, though the group members report an equivalent level of alcohol related consequences as the other two groups. In the context of a brief AUD treatment study, this is the group would be expected to succeed equally well in all conditions or with limited intervention. It is interesting to note that this group was by far the smallest cluster, making up just under 15% of the sample.

Individuals in the Low cluster group were characterized by the lowest scores on all three items. Unlike the other two groups, the Low cluster group reported the least amount of confidence and commitment to reduce their drinking—with mean scores well below the general group mean. The mean z score of the Low group for commitment to abstain was the lowest among the three groups, potentially suggesting a commitment to daily drinking. Interestingly, the Low cluster group distinguished itself from the other two groups by having the highest proportion of individuals who had previously received treatment for AUD. Given their level of exposure to treatment, it is interesting to note that the Low group also had the lowest scores on both the POC behavioral and cognitive scales. In the context of a brief AUD treatment, this is the group that would be expected to be most helped by interventions that attempted to enhance commitment and confidence to change.

The Moderate cluster group was perhaps the most puzzling. Rather than distinguishing itself as a group directly between the High and Low groups in its attributes, it appears to be more a combination of the two groups. While one could conclude from this that the moderate group is an indicator of a poor clustering solution, the drinking outcomes of the moderate group suggest otherwise, as they are clinically consistent with this group’s commitment and confidence to change. The Moderate group’s commitment to abstain is low and similar to the Low group, again demonstrating a desire to continue daily drinking. While their intensity and frequency of drinking at baseline are similar to the Low group, their confidence and commitment to reduce drinking are similar to the High group. This elevated confidence and commitment to drink reduction may be in part due to the small proportion of individuals in this group who have exposure to previous AUD treatment. It may be also that these individuals have yet to attempt to cut back. Consistent with this theory is the fact that the Moderate group has a POC behavioral coping score akin to the Low group. It is unclear how this group might respond to brief AUD treatments, given that their confidence and commitment to reduce drinking is as high as the High group. Even with their low commitment to abstain, the moderate group still achieves a substantial reduction in their daily drinks.

There are a number of important clinical implications that can be gleaned from this study. First, baseline values of confidence and commitment to particular behaviors (e.g., abstinence, reduction) can have important prognostic implications for successful goal achievement and brief interventions for AUD. Second, these findings suggest possibilities for treatment matching (Longabaugh, Wirtz, DiClemente, & Litt, 1994), with individuals low in confidence and commitment to reduce their drinking benefiting from interventions that target those constructs, as found in Witkiewitz et al. (2010). Third, the drinking trajectories of each of the groups point to possible points of intervention. Across groups, individuals were able to reduce their DDD without skills training. Given the particular approach to moderation of the High group, a next level of care or a stepped up care intervention might therefore include skills training around abstaining at least one or two days per week. While recommendations for reducing drinking days are a component of most moderation programs (e.g., National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, 2013b), it may be that drinking fewer days is a particularly good strategy for reducing drinking to safe levels. Finally, the findings point to the fact that participants entering a treatment study (at least one that is focused on drink reduction rather than abstinence) are already implementing some strategies to reduce drinking. Understanding what those strategies are is crucial for optimizing interventions to facilitate further change.

Limitations

There are a number of limitations to this exploratory study. A primary limitation of the study is that the reliability of these classes is unknown. Replication is required in order to determine if these classes would emerge in other samples of problem drinkers. Furthermore, the use of cluster analysis here is a simple and limited approach due to its reliance on decisions made by investigators for clustering. While we defined the number of classes based on previous research and clinical information and we attempted to verify the group membership, there are more sophisticated approaches, such as latent class analysis, that could be applied with this data that might be less inherently biased; however, those approaches usually require a larger sample size (e.g., larger than 100) than what we had available (Wurpts, 2012), and it would not have addressed the problem of reliability. Sample size and resulting lack of power limit: the interpretation of our analyses, the generalizability, and our ability to test for a moderating effect of the differing levels of confidence and commitment on treatment efficacy. All our conclusions about the High group are limited due to an N of only 12. The daily diary method was limited to one time point for data collection each day. More sophisticated methods of EMA measure constructs at multiple, random time points throughout the day. Such data could illustrate a different relationship between motivation, self-efficacy, and drinking.

Future Research

Results suggest the importance of using ecological momentary assessment, even when using the data in aggregate, to obtain important information about participants in intervention research and clinical settings that has implications for prognosis and treatment outcome. The data obtained via daily diary methods and other forms of ecological momentary assessment can provide a level of richness, even when used in composite form, that can help better understand the nuances across individual drinking patterns and trajectories that can help us to hone interventions to be increasingly effective and efficient. Additionally, future research should explore the possibility of better treatment matching by using EMA as a way to assess an individual’s needs within treatment, as done by Litt et al. (2003).

Conclusion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to use ecological momentary assessment at baseline to create profiles of problem drinkers that inform potential prognoses for successful moderated drinking. Understanding the motivation and self-efficacy to moderate drinking in a way that better captures their qualities in context over time can provide important information about the individuals appropriate for and able to moderate drinking. While more tedious than standard global self reports, collecting information about patients over a seven day period could be cost beneficial in the long run, as clinicians can better facilitate goal setting and optimize treatment selection.

Table 3.

Results of GEE models for each of the drinking outcome variables

| B | SE | IRR | 95% CI | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sum of Standard Drinks (SSD) | |||||

| MODEL 1 | |||||

| STEP 1 | |||||

| Baseline SSD | .012 | .00 | 1.01 | 1.01–1.02 | < .0001 |

| High v Low | −.323 | .07 | .72 | .64–.82 | < .0001 |

| Moderate v Other 2 groups | .040 | .03 | 1.04 | .99–1.10 | .14 |

| Time | −.031 | .01 | .97 | .95–.99 | < .001 |

| STEP 2 | |||||

| High v Low*Time | .004 | .02 | 1.00 | .97–1.04 | .80 |

| Moderate v Others*Time | .003 | .01 | 1.00 | .99–1.02 | .66 |

| MODEL 2 | |||||

| STEP 1 | |||||

| Baseline SSD | .012 | .00 | 1.01 | 1.01–1.02 | < .0001 |

| High v Moderate | −.222 | .06 | .80 | .71–.90 | < .001 |

| Low v Other 2 groups | .141 | .03 | 1.15 | 1.08–1.22 | < .0001 |

| Time | −.031 | .01 | .97 | .95–.99 | < .001 |

| STEP 2 | |||||

| High v Moderate*Time | −.002 | .02 | 1.00 | .97–1.03 | .89 |

| Low v Others*Time | −.004 | .01 | 1.00 | .98–1.01 | .61 |

| MODEL 3 | |||||

| STEP 1 | |||||

| Baseline SSD | .012 | .00 | 1.01 | 1.01–1.02 | < .0001 |

| Low v Moderate | .101 | .04 | 1.10 | 1.02–1.20 | < .02 |

| High v Other 2 groups | −.181 | .04 | .83 | .77–.90 | < .0001 |

| Time | −.031 | .01 | .97 | .95–.99 | < .001 |

| STEP 2 | |||||

| Low v Moderate*Time | −.006 | .01 | .99 | .98–1.01 | .44 |

| High v Others*Time | .001 | .01 | 1.00 | .98–1.02 | .95 |

| Number of Drinking Days (NDD) | |||||

| MODEL 4 | |||||

| STEP 1 | |||||

| Baseline NDD | .116 | .02 | 1.12 | 1.07–1.17 | < .0001 |

| High v Low | −.219 | .06 | .80 | .71–.91 | < .001 |

| Moderate v Other 2 groups | .064 | .02 | 1.06 | 1.01–1.15 | < .01 |

| Time | −.013 | .01 | .99 | .98–1.00 | < .05 |

| STEP 2 | |||||

| High v Low*Time | −.005 | .01 | 1.00 | .97–1.02 | .74 |

| Moderate v Others*Time | .004 | .01 | 1.00 | .99–1.01 | .49 |

| MODEL 5 | |||||

| STEP 1 | |||||

| Baseline NDD | .116 | .02 | 1.12 | 1.07–1.17 | < .0001 |

| High v Moderate | −.206 | .06 | .81 | .72–.92 | < .001 |

| Low v Other 2 groups | .077 | .02 | 1.08 | 1.03–1.13 | .001 |

| Time | −.013 | .01 | .99 | .98–1.00 | < .05 |

| STEP 2 | |||||

| High v Moderate*Time | −.008 | .01 | .99 | .97–1.02 | .56 |

| Low v Others*Time | .000 | .01 | 1.00 | .99–1.01 | .94 |

| MODEL 6 | |||||

| STEP 1 | |||||

| Baseline NDD | .116 | .02 | 1.12 | 1.07–1.17 | < .0001 |

| Low v Moderate | .013 | .02 | 1.01 | .96–1.06 | .60 |

| High v Other 2 Groups | −.142 | .04 | .87 | .80–.94 | < .001 |

| Time | −.013 | .01 | .99 | .98–1.00 | < .05 |

| STEP 2 | |||||

| Low v Moderate*Time | −.003 | .01 | 1.00 | .98–1.01 | .60 |

| High v Others*Time | −.004 | .01 | 1.00 | .98–1.01 | .64 |

| Drinks per Drinking Day (DDD) | |||||

| MODEL 7 | |||||

| STEP 1 | |||||

| Baseline DDD | .063 | .02 | 1.06 | 1.03–1.10 | < .001 |

| High v Low | −.350 | .07 | .70 | .61–.81 | < .0001 |

| Moderate v Other 2 groups | .025 | .03 | 1.02 | .97–1.08 | .38 |

| Time | −.072 | .01 | .93 | .91–.95 | < .0001 |

| STEP 2 | |||||

| High v Low*Time | −.045 | .02 | .96 | .92–.99 | .02 |

| Moderate v Others*Time | .014 | .01 | 1.01 | 1.00–1.02 | .10 |

| MODEL 8 | |||||

| STEP 1 | |||||

| Baseline DDD | .063 | .02 | 1.06 | 1.03–1.10 | < .001 |

| High v Moderate | −.213 | .07 | .81 | .71–.92 | < .01 |

| Low v Other 2 groups | .163 | .03 | 1.18 | 1.11–1.25 | < .0001 |

| Time | −.072 | .01 | .93 | .91–.95 | < .0001 |

| STEP 2 | |||||

| High v Med*Time | −.043 | .020 | .96 | .92–.996 | .03 |

| Low v Others*Time | .016 | .008 | 1.01 | .998–1.03 | .05 |

| MODEL 9 | |||||

| STEP 1 | |||||

| Baseline DDD | .063 | .02 | 1.06 | 1.03–1.10 | < .001 |

| Low v Moderate | .138 | .04 | 1.15 | 1.06–1.24 | < .001 |

| High v Other 2 groups | −.188 | .04 | .83 | .76–.90 | < .0001 |

| Time | −.072 | .01 | .93 | .91–.95 | < .0001 |

| STEP 2 | |||||

| Low v Moderate*Time | .002 | .010 | 1.00 | .98–1.02 | .85 |

| High v Others*Time | −.029 | .013 | .97 | .95–.995 | .02 |

IRR = Incidence Rate Ratio

Acknowledgments

This study was supported with funding from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (grants R21 AA 017135, R01 AA020077; PI: Morgenstern).

Contributor Information

Alexis Kuerbis, Research Foundation for Mental Hygiene, Inc. and Columbia University Medical Center.

Stephen Armeli, Fairleigh Dickinson University.

Frederick Muench, Research Foundation for Mental Hygiene, Inc. and Columbia University Medical Center.

Jon Morgenstern, Columbia University Medical Center.

References

- Adamson SJ, Sellman JD. Drinking goal selection and treatment outcome in out-patients with mild-moderate alcohol dependence. Drug and Alcohol Review. 2001;20(4):351–359. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Otaiba Z, Worden BL, McCrady BS, Epstein EE. Accounting for self-selected drinking goals in the assessment of treatment outcome. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2008;22(3):439–443. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.22.3.439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aldenderfer M, Blashfield R. Cluster analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Ambrogne JA. Reduced-risk drinking as a treatment goal: What clinicians need to know. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2002;22:45–53. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(01)00210-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed., text revision ed. Washington, DC: Author; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Amrhein PC, Miller WR, Yahne CE, Palmer M, Fulcher L. Client commitment language during motivational interviewing predicts drug use outcomes. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71(5):862–878. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.71.5.862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Annis HM, Davis CS. Self-efficacy and the prevention of alcoholic relapse: Initial findings from treatment trial. In: Baker TB, Cannon DS, editors. Assessment and treatment of addictive disorders. New York: Praeger; 1988. pp. 88–112. [Google Scholar]

- Annis HM, Graham JM. A Situational Confidence Questionnaire (SCQ 39) users guide. Toronto: Addiction Research Foundation; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Anton RF. Obsessive-compulsive aspects of craving: Development of the Obsessive Compulsive Drinking Scale. Addiction. 2000;95(Supp. 2):S211–S217. doi: 10.1080/09652140050111771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apodaca TR, Longabaugh R. Mechanisms of change in motivational interviewing: A review and preliminary evaluation of the evidence. Addiction. 2009;104(5):705–715. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02527.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babor TF, Higgins-Biddle JC, Saunders JB, Monteiro MG. The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): Guidelines for use in primary care. 2nd ed. Geneva, Switzerland: Department of Mental Health and Substance Dependence, World Health Organization; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review. 1977;84(2):191–215. doi: 10.1037//0033-295x.84.2.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Self-efficacy mechanism in human agency. American Psychologist. 1982;37(2):122–147. [Google Scholar]

- Bargh JA, Gollwitzer PM, Oettingen G. Motivation. In: Fiske ST, Gilbert DT, Lindzey G, editors. Handbook of Social Psychology. 5th ed. Vol. 2. New York: Wiley; 2010. pp. 268–316. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Beck Depression Inventory. Second Edition Manual. San Diego, CA: Harcourt Brace; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Brown TG, Seraganian P, Tremblay J, Annis HM. Process and outcome changes with relapse prevention versus 12-step aftercare programs for substance abusers. Addiction. 2002;97:677–689. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bujarski S, O’Malley SS, Lunny K, Ray LA. The effects of drinking goal on treatment outcome for alcoholism. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2013;81(1):13–22. doi: 10.1037/a0030886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bush K, Kivlahan DR, McDonell MB. The AUDIT Alcohol Consumption Questions (AUDIT-C): An effective brief screening test for problem drinking. Archives of Internal Medicine. 1998;3:1789–1795. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.16.1789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell SD, Adamson SJ, Carter JD. Client language during motivational enhancement therapy and alcohol use outcome. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy. 2010;38:399–415. doi: 10.1017/S1352465810000263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carbonari JP, DiClemente Carlo C. Using transtheoretical model profiles to differentiate levels of alcohol abstinence success. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology. 2000;68(5):810–817. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey KB, Carey MP, Maisto SA, Henson JM. Temporal stability of the Timeline Followback Interview for alcohol and drug use with psychiatric outpatients. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2004;65:774–781. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2004.65.774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connors GD, Walitzer KS. Reducing alcohol consumption among heavily drinking women: Evaluating the contributions of life-skills training and booster sessions. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2001;125(1–2):67–74. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.69.3.447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cottler LB, Robins LN, Helzer JE. The reliability of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview Substance Abuse Module-(CIDI-SAM): A comprehensive substance abuse interview. British Journal of Addiction. 1989;84:801–814. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1989.tb03060.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham JA. Resolving alcohol-related problems with and without treatment: The effects of different problem criteria. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1999;60(4):463–466. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1999.60.463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson DA, Grant BF, Stinson FS, Chou PS, Huang B, Ruan WJ. Recovery from DSM-IV alcohol dependence: United States, 2001–2002. Addiction. 2005;100:281–292. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00964.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health and Human Services. Tenth special report to the U.S. Congress on alcohol and health. Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- DiClemente CC, Huges SO. Stages of change profiles in outpatient alcoholism treatment. Journal of Substance Abuse. 1990;2:217–235. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(05)80057-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiClemente CC, Schlundt D, Gemmell L. Readiness and stages of change in addiction treatment. American Journal on Addictions. 2004;13(2):103–119. doi: 10.1080/10550490490435777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dillon FR, Turner CW, Robbins MS, Szapocznik J. Concordance among biological, interview, and self-report measures of drug use among African American and Hispanic adolescents referred for drug abuse treatment. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2005;19(4):404–413. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.19.4.404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garson GD. Cluster Analysis. Asheboro, NC: Statistical Associates Publishing; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Heather N, Dawe S. Level of impaired control predicts outcome of moderation-oriented treatment for alcohol problems. Addiction. 2005;100(7):945–952. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01104.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heather N, McCambridge J, Ukatt Research Team. Post-treatment Stage of Change Predicts 12-month Outcome of Treatment for Alcohol Problems. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 2013;48(3):329–336. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agt006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heather N, Rollnick S. Readiness to change questionnaire: User's manual. Newcastle, England: University of Northumbria at Newcastle; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Heather N, Rollnick S, Winton M. A comparison of objective and subjective measures of alcohol dependence as predictors of relapse following treatment. British Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1983;22:11–17. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8260.1983.tb00574.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hester RK. Self-control training. In: Hester RK, Miller WR, editors. Handbook of alcoholism treatment approaches: Effective alternatives. 2nd ed. Needham Heights, MA: Allyn & Bacon; 1995. pp. 148–159. [Google Scholar]

- Hodgins DC, Ching LE, McEwen J. Strength of commitment language in Motivational Inteviewing and gambling outcomes. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2009;23(1):122–130. doi: 10.1037/a0013010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ilgen MA, Wilbourne PL, Moos BS, Moos RH. Problem-free drinking over 16 years among individuals with alcohol use disorders. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2008;92(1–3):116–122. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahler CW, Strong DR, Hayaki J, Ramsey SE, Brown RA. An item response analysis of the Alcohol Dependence Scale in treatment-seeking alcoholics. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2003;64:127–136. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2003.64.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kavanagh DJ, Sitharthan T, Sayer G. Prediction of results from correspondence treatment for controlled drinking. Addiction. 1996;91(10):1539–1545. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly JF, Magill M, Stout RL. How do people recover from alcohol dependence? A systematic review of the research on mechanisms of behavior change in Alcoholics Anonymous. Addiction Research and Theory. 2009;17(3):236–259. [Google Scholar]

- Kenna GA, Longabaugh R, Gogineni A, Woolard RF, Nirenberg TD, Becker B, Karolczuk K. Can the Short Index of Problems (SIP) be improved? Validity and reliability of the 3-Month SIP in an emergency department sample. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2005;66(3):433–437. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuerbis A, Armeli S, Muench F, Morgenstern J. Motivation and self-efficacy in the context of moderated drinking: Global self-report and ecological momentary assessment. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2013;27(4):934–943. doi: 10.1037/a0031194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuerbis A, Morgenstern J, Hail LA. Predictors of moderated drinking in a primarily alcohol dependent sample of men who have sex with men. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2012;26(3):484–495. doi: 10.1037/a0026713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laursen B, Hoff E. Person-centered and variable-centered approaches to longitudinal data. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. 2006;52(3):377–389. [Google Scholar]

- Litt M, Kadden R, Cooney N, Kabela E. Coping skills and treatment outcomes in cognitive-behavioral and interactional group therapy for alcoholism. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71(1):118–128. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.71.1.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longabaugh R, Wirtz P, DiClemente CC, Litt MD. Issues in the development of client-treatment matching hypotheses. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1994;55(Suppl 12):46–59. doi: 10.15288/jsas.1994.s12.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendoza NS, Walitzer KS, Connors GJ. Use of treatment strategies in a moderated drinking program for women. Addictive Behaviors. 2012;37(9):1054–1057. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mertens JR, Kline-Simon AH, Delucchi KL, Moore C, Weisner CM. Ten-year stability of remission in private alcohol and drug outpatient treatment: Non-problem users versus abstainers. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2012;125(1–2):67–74. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Munoz RF. Controlling your drinking. New York: The Guilford Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Rose GS. Toward a theory of Motivational Interviewing. American Psychologist. 2009;64(6):527–537. doi: 10.1037/a0016830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Tonigan JS, Longabaugh R. NIAAA Project MATCH Monograph Series Volume 4. Rockville, MD: NIAAA Project MATCH Monograph Series Volume 4; 1995. The Drinker Inventory of Consequences (DrInC): An instrument for assessing adverse consequences of alcohol abuse. Test manual. [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Zweben A, DiClemente CC, Rychtarik RG. Rockville, MD: National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; 1992. Motivational Enhancement Therapy manual: A clinical research guide for therapists treating individuals with alcohol abuse and dependence. [Google Scholar]

- Moos RH, Moos BS. Rates and predictors of relapse after natural and treated remission alcohol use disorders. Addiction. 2006;101(2):212–222. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01310.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan TJ, Morgenstern J, Blanchard K, Labouvie E, Bux DA. Development of the OCDS-Revised: A measure of alcohol and drug urges with outpatient substance abuse clients. Psychology of Addictive Behavior. 2004;18(4):316–321. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.18.4.316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgenstern J, Irwin TW, Wainberg ML, Parsons JT, Muench F, Bux DA, Schulz-Heik J. A randomized controlled trial of goal choice interventions for alcohol use disorders among men-who-have-sex-with-men. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2007;75(1):72–84. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.1.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgenstern J, Kuerbis A, Amrhein PC, Hail LA, Lynch KG, McKay JR. Motivational interviewing: A pilot test of active ingredients and mechanisms of change. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2012;26(4):859–869. doi: 10.1037/a0029674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgenstern J, Kuerbis A, Chen A, Kahler CW, Bux DA, Kranzler H. A randomized clinical trial of naltrexone and behavioral therapy for problem drinking men-who-have-sex-with-men. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2012;80(5):863–875. doi: 10.1037/a0028615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgenstern J, Labouvie E, McCrady BS, Kahler CW, Frey R. Affiliation with Alcoholics Anonymous after treatment: A study of its therapeutic effects and mechanisms of action. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1997;65(5):768–777. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.5.768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moyers TB, Martin T, Houck JM, Christopher PJ, Tonigan JS. From in-session behaviors to drinking outcomes: A causal chain for Motivational Interviewing. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77(6):1113–1124. doi: 10.1037/a0017189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Drinking statistics. 2013a Retrieved from National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism website: http://www.niaaa.nih.gov/alcohol-health/overview-alcohol-consumption.

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Rethinking drinking. Bethesda, MD: Author; 2013b. [Google Scholar]

- Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC, Norcross JC. In search of how people change: Applications to addictive behaviors. American Psychologist. 1992;47:1102–1114. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.47.9.1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Project MATCH Research Group. Project MATCH: Rationale and methods for a multisite clinical trial matching patients to alcoholism treatment. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1993;17:1130–1145. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1993.tb05219.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Project MATCH Research Group. Matching alcoholism treatments to client heterogeneity: Project MATCH posttreatment drinking outcomes. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1997;58(1):7–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Project MATCH Research Group. Matching alcoholism treatments to client heterogeneity: Project MATCH three-year drinking outcomes. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1998;22:1300–1311. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1998.tb03912.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg H. Prediction of controlled drinking by alcoholics and problem drinkers. Psychological Bulletin. 1993;113(1):129–139. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.113.1.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saladin ME, Santa Ana EJ. Controlled drinking: More than just a controversy. Current Opinion in Psychiatry. 2004;17:175–187. [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S, Stone AA, Hufford MR. Ecological momentary assessment. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2008;4:1–32. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sitharthan T, Job RFS, Kavanagh DJ, Sitharthan G, Hough M. Development of a controlled drinking self-efficacy scale and appraising its relation to alcohol dependence. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2003;59(3):351–362. doi: 10.1002/jclp.10127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sitharthan T, Kavanagh DJ. Role of self-efficacy in predicting outcomes from a programme for controlled drinking. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1990;27:87–94. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(91)90091-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sitharthan T, Kavanagh DJ, Sayer G. Moderating drinking by correspondence: An evaluation of a new method of intervention. Addiction. 1996;91(3):345–355. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1996.9133455.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner HA, Allen BA. Alcohol dependence syndrome: Measurement and validation. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1982:199–209. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.91.3.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner HA, Horn JL. Alcohol Dependence Scale: Users guide. Toronto, Ontario, Canada: Addiction Research Foundation; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, Ellingstad TP, Sobell MB. Natural recovery from alcohol and drug problems: Methodological review of the research with suggestions for future directions. Addiction. 2000;95(5):749–764. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2000.95574911.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell MB, Maisto SA, Sobell LC, Cooper AM, Cooper T, Saunders B. Developing a prototype for evaluating alcohol treatment effectiveness. In: Sobell LC, Ward E, editors. Evaluating alcohol and drug abuse treatment effectiveness: Recent advances. New York: Pergamon; 1980. pp. 129–150. [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger DC. The State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologist Press; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- TELESAGE, Inc. SmartQ 5.2 automated telephone survey software. Chapel Hill, NC: Author; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Tucker JA, Vuchinich RE, Black BC, Rippens PD. Significance of a behavioral economic index of reward value in predicting drinking problem resolution. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74(2):317–326. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.2.317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinson DC, Reidinger C, Wilcosky T. Factors affecting the validity of a Timeline Followback Interview. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2003;64:733–740. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2003.64.733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walters GD. Behavioral self-control training for problem drinkers: A meta-analysis of randomized control studies. Behavior Therapy. 2000;31:135–149. [Google Scholar]

- Witkiewitz K, Hartzler B, Donovan D. Matching motivation enhancement treatment to client motivation: re-examining the Project MATCH motivation matching hypothesis. Addiction. 2010;105(8):1403–1413. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.02954.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittchen HU, Robins LN, Cottler LB, Sartorius N, Burke JD, Regier D trials, Participants in the multicentre WHO/ADAMHA field. Cross-cultural feasibility, reliability and sources of variance of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) British Journal of Psychiatry. 1991;159:645–653. doi: 10.1192/bjp.159.5.645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wurpts IC. Testing the limits of latent class analysis. MA: Arizona State University; 2012. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/1013441463 (1509188) [Google Scholar]