Abstract

The serum opacity factor (SOF) of Streptococcus pyogenes is a serotyping tool and pathogenesis factor. Using SOF-coated latex beads in cell adherence assays and antiserum directed against SOF in S. pyogenes-HEp-2 cell adherence inhibition experiments, we demonstrate SOF involvement in the fibronectin-mediated adherence of S. pyogenes to epithelial cells. SOF exclusively targets the 30-kDa N-terminal region of fibronectin. The interaction revealed association and dissociation constants 1 order of magnitude lower than those of other S. pyogenes fibronectin-binding proteins.

Streptococcus pyogenes bacteria (group A streptococci [GAS]) cause a large array of diseases in humans, ranging from mild superficial infections (tonsillitis, impetigo) to severe infections of deeper-seated connective tissues (necrotizing fasciitis). Only occasionally do these bacteria cause life-threatening septicemia and toxic shock-like syndrome with mostly fatal outcomes (12).

As the initial step of S. pyogenes colonization and infection, the bacteria adhere specifically to epithelial cells. Among several possible molecular pathways for the adherence process, fibronectin binding is currently favored as the most important one. Among many other GAS MSCRAMMs (microbial surface components recognizing adhesive matrix molecules) (38), at least 10 different fibronectin-binding proteins were discovered, of which SfbI (also known as PrtF1) is the best-studied molecule. Like MSCRAMMs in general (38), SfbI is composed of structural modules. Typical signal sequences, targeting the molecule for the export machinery, and cell wall-membrane regions, providing signature sequences for covalent surface anchoring, could be found at the N and C termini, respectively. A variable number of repetitive units and one nonrepetitive module with a unique sequence mediating fibronectin binding are located in the C-terminal region of the molecule (17, 44-46). The large N-terminal domain of the molecule was shown to bind to the extracellular plasma protein fibrinogen (23). The gene encoding SfbI is present in about 50 to 80% of the isolates tested (3, 16, 25, 27, 34, 50).

Numerous studies have demonstrated that GAS adhere to a large number of different cell types and tissues (7) and that these organisms could be internalized by epithelial cells (4, 13, 28, 29). More recent studies have unequivocally proved the role and importance of the GAS M1 protein (11, 13) and SfbI for the internalization process (18, 32, 33, 35). Binding of fibronectin by S. pyogenes via SfbI served as a bridge linking bacteria to the fibronectin-binding integrin α5β1 (33, 35). This finally initiates the internalization process.

Another fibronectin-binding surface protein is SOF, the serum opacity factor of GAS, which has served as a marker for serotyping and distinguishes two S. pyogenes lineages. The typing scheme is based on type-specific determinants of the SOF protein. This molecule exhibited N-terminal sequence variation similar to that of the GAS M protein (22, 30). Like the gene encoding the M protein, sof is under the positive transcriptional regulation of Mga, the global positive-acting response regulator (31). The sof gene was found in 30 to 55% of the GAS isolates tested (16, 27), and mainly the N terminus of the expressed molecule was found to elicit type-specific immune responses (15).

Recently, a study revealed the presence of a gene (sfbX) encoding another fibronectin-binding protein downstream of the sof gene in all of the SOF+ isolates tested (20). Both genes are cotranscribed as a bicistronic message, a fact overlooked in previous studies. Elegant mutational analysis and heterologous expression experiments confirmed earlier observations from biochemical analysis and demonstrated the exclusive responsibility of SOF for the serum opacification reaction (20). The authors further concluded that the SOF− GAS lineage probably developed by deletion of the sof-sfbX gene locus (20).

The enzymatic activity of SOF generates opalescence of sera from several mammalian species (51) via specific cleavage of the apolipoprotein AI component of the high-density lipoprotein fraction of serum (42, 43). Thus, SOF is a bifunctional protein with an enzymatic domain localized to the N terminus and a fibronectin-binding module located at the C terminus (24, 26, 27, 40). Together with the presence of the signal sequence and wall-membrane region, SOF displays the typical architecture of MSCRAMMs.

Courtney and coworkers have demonstrated the importance of SOF in a mouse intraperitoneal infection model (8). However, conclusions were drawn without knowledge of the sfbX gene located downstream of sof, which was most likely also affected by the mutation strategy. An additional matrix-binding activity of fibrinogen was found to map to the repetitive domain at the C terminus of the SOF molecule (6), and SOF was shown to elicit antibodies with opsonizing activity toward heterologous SOF types (9). SOF and SfbX are both involved in adherence of GAS to immobilized fibronectin (20). However, there is no direct experimental evidence of SOF-mediated adherence of GAS to host cells. Therefore, our experiments were done to investigate this hypothesis.

Mapping of the SOF-binding region on the fibronectin molecule.

Fibronectin could be present either in a soluble form contained in human plasma or as an integrin-bound form on the surface of eukaryotic cells. Depending on the form encountered by GAS, different modules on the fibronectin molecule could be accessible for the interaction. In order to test which fibronectin domain is targeted by SOF, we investigated the binding of radioactively labeled fibronectin fragments (30, 45, 70, and 120 kDa; all from Sigma) (for the methods used, refer to reference 46) to a recombinant SOF fragment (HT1) (26) that was composed of the enzymatic domain and the fibronectin-binding repeat region but did not include the signal sequence and the wall-membrane region. Purified recombinant HT1 (10 μg) was separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and blotted onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes by semidry protocols. Each iodinated fibronectin fragment was incubated with HT1 on membranes. After thorough washing, bound fragments were visualized by autoradiography. HT1 only bound whole fibronectin and the 70- and 30-kDa fragments (data not shown).

For a more detailed analysis of the SOF-fibronectin interaction and determination of biochemical parameters, we performed real-time biospecific interaction analysis by using surface plasmon resonance measurements and the BIAcore system (Biosensor, La Jolla, Calif.). Whole fibronectin (220 kDa) and the 70-, 45-, and 30-kDa fibronectin fragments were immobilized as ligands on CM5 sensor chips in accordance with standard methods (28). The recombinant HT1 fragment of SOF75 was used at increasing concentrations as an analyte in the liquid phase, thereby allowing kinetic measurements and calculation of the association and dissociation constants of the SOF75-fibronectin interaction. The representative sensorgrams revealed the binding kinetics and concentration dependence of rates of binding of fibronectin and its fragments to HT1 (data not shown). There was no interaction between HT1 and the 45-kDa fibronectin fragment, which corresponded to the Western blotting results mentioned above. The data of the BIAcore sensorgrams were locally fitted by using the one-step biomolecular association reaction model (1:1 Langmuir model: A + B ↔ AB), which resulted in optimum mathematical fits reflected by the lowest chi values. From the data shown in Table 1, it can be concluded that the association (KA) and dissociation (KD) constants are in the range of 107 and 10−8, respectively, which confirms a specific interaction of SOF75 with fibronectin. However, the binding strength is 1 order of magnitude lower, as described for other relevant MSCRAMMs of gram-positive cocci and their binding to human matrix proteins (2, 14, 21, 28, 37, 49). It is possible that SOF is important for establishment of initial low-strength contact between the GAS and fibronectin, prior to high-affinity binding of SfbI or PrtF2 in SfbI-negative strains (28). Alternatively, SOF-fibronectin interaction could be important at times when expression of other fibronectin-binding MSCRAMMs is downregulated or such proteins are shed from the bacterial surface.

TABLE 1.

Surface plasmon resonance measurement of the interaction of SOF75 (HT1 fragment) with fibronectin and fibronectin domainsa

| Analyte | Ligand | ka (M−1 s−1, 104) | kd (s−1, 10−3) | KA (M−1, 107) | KD (M, 10−8) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SOF75 (HT1) | Whole Fnb | 2.9 | 2.6 | 3.5 | 2.7 |

| SOF75 (HT1) | Fn 70 kDa | 1.8 | 1.5 | 1.2 | 8.5 |

| SOF75 (HT1) | Fn 30 kDa | 1.7 | 2.5 | 0.68 | 0.14 |

The binding data of the interaction were fitted locally by using the one-step biomolecular association reaction model (1:1 Langmuir model: A + B ↔ AB), which resulted in optimum mathematical fits reflected by the lowest chi values. The association (ka) and dissociation (kd) rates and association (KA) and dissociation (KD) constants were calculated from the binding data with the BIAevaluation software.

Fn, fibronectin.

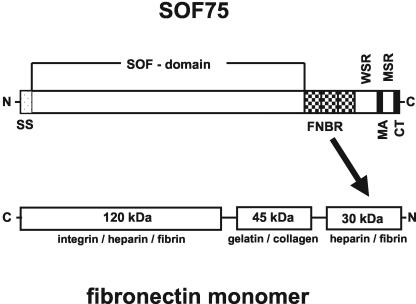

As schematically summarized in Fig. 1, SOF strongly bound the 30-kDa N-terminal heparin-fibrin-binding domain of fibronectin and consequently also the 70-kDa N-terminal domain, composed of the fibrin-heparin- and collagen-gelatin-binding domains. Interaction of the 45-kDa collagen-gelatin-binding module and the 120-kDa integrin-heparin-fibrin-binding module of fibronectin with HT1 could not be detected.

FIG. 1.

Schematic drawing of the interaction of SOF with the fibronectin monomer. Abbreviations: SS, signal sequence; FNBR, fibronectin-binding repeats; WSR, wall-spanning region; MA, membrane anchor; MSR, membrane-spanning region; CT, charged tail.

This binding pattern was also found for PrtF2 and distinguished SOF and PrtF2 from SfbI (28, 36, 47). SOF did not target the 45-kDa collagen-gelatin region of fibronectin, unlike SfbI. Thus, the SOF-fibronectin interaction may not involve a two-step binding mechanism, followed by structural changes and initiation of bacterial internalization into host cells as described for SfbI (47).

Different from the two fibronectin-binding domains of SfbI, the lack of a second fibronectin-binding region on the SOF molecule could explain the missing affinity for the 45-kDa fibronectin domain. There is clearly a redundancy in the presence of fibronectin-binding proteins among GAS. However, the differences in the modes and affinities of fibronectin binding could explain the biological background of this redundancy. GAS could interact with fibronectin in different ways, a fact which in turn could be crucial for the various types of pathogenesis induced by the presence of GAS in diverse human tissues.

SOF-mediated adherence and internalization of latex beads.

Many GAS isolates carry more than one fibronectin-binding MSCRAMM, of which SfbI (17, 45, 46) is the best studied. Among the others are PrtF2 (19, 28), PFBP (41), FBP54 (5), Fba (OrfX) and FbaB (39, 48, 49), the M1 protein (10, 11), and SOF (6, 20, 24, 26, 27). Only for SfbI, PrtF2, FBP54, the M1 protein, Fba, and FbaB has direct experimental evidence of involvement in adherence to and internalization into host cells been presented (5, 10, 17, 28, 33, 35, 48, 49). The role of SOF in these processes still needs to be determined.

To circumvent the functional background of multiple fibronectin-binding MSCRAMMs in a single GAS strain, we used an indirect approach to study SOF activities. In accordance with previously published methods (13, 33) and control experiments, latex beads (3 μm; Sigma) were coated with (i) purified recombinant pGBK6 and pGBK2 glutathione S-transferase fusion proteins that included the N-terminal half of SOF75 and the repetitive fibronectin-binding region of SOF75 (27), respectively, and (ii) purified recombinant HT1 and HT2 His tag fusion proteins (26) that contained the entire mature protein, i.e., the SOF enzymatic domain plus the fibronectin-binding repeat region and the SOF enzymatic domain without the fibronectin-binding repeat region, respectively.

Briefly, 108 bead particles in 20 μl of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) were incubated with 50 μl of purified proteins (100 μg/ml) in PBS overnight at 4°C. After washing steps, free binding sites on the bead surface were blocked by incubation in 200 μl of bovine serum albumin (10 mg/ml in PBS) for 1 h at room temperature. The efficiency of particle loading was verified by fluorescence-activated cell sorter analysis with specific antibodies against SOF and fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled secondary antibodies (data not shown). Beads were washed, and the volume was adjusted to 1.8 ml of Dulbecco modified Eagle medium. The target cells were seated in six-well plates at 0.8 × 106 to 1.2 × 106 cells per well (Nunc) and, after addition of 300 μl of the bead suspension (approximately 17 × 106 beads per well, 17 beads per cell), incubated for 1 h at 37°C under a 5% CO2 atmosphere. Unbound beads were washed away, and cells were either inspected by light microscopy or further processed for scanning electron microscopy.

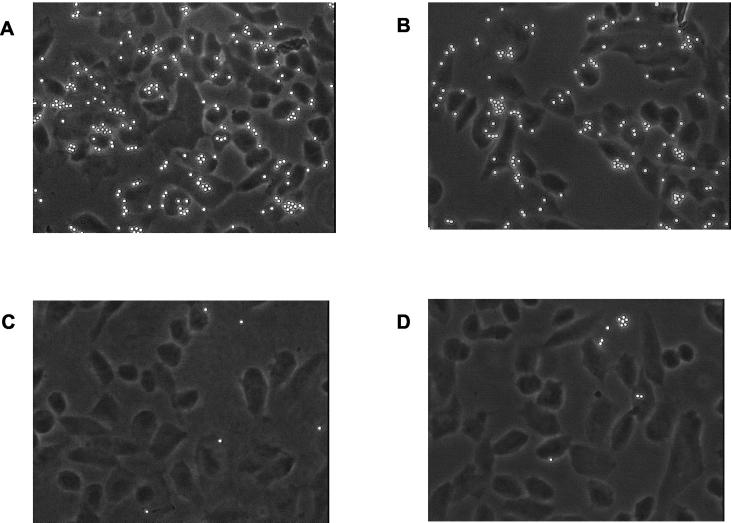

In a first experimental series, HEp-2 cells were incubated with particles coated with different SOF domains. The qualitative results shown in Fig. 2 revealed that only the fibronectin-binding repeat region of SOF, contained in pGBK2 (Fig. 2A) and HT1 (Fig. 2B), mediated substantial adherence of the beads to the HEp-2 cells. All recombinant SOF subdomains lacking this module did not support adherence of the beads (Fig. 2C and D).

FIG. 2.

Adherence of SOF-coated latex beads to HEp-2 cells. (A) Adherence of latex beads coated with the recombinant fibronectin-binding repeat domain of SOF75 (pGBK2). (B) Adherence of latex beads coated with the mature recombinant SOF75 domain (HT1, including the fibronectin-binding repeats). (C) Adherence of latex beads coated with the recombinant N-terminal SOF75 domain (pGBK6). (D) Adherence of latex beads coated with the entire recombinant SOF75 enzymatic domain (HT2). pGBK6 and HT2 do not contain the fibronectin-binding repeat region.

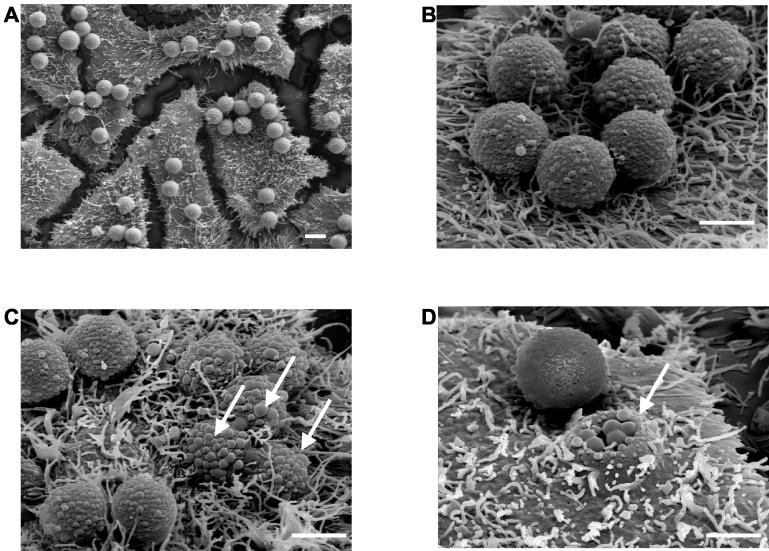

Scanning electron microscopic pictures (Fig. 3) allowed a closer look at HT1-coated bead particles interacting with HEp-2 cell monolayers (for the methods used to prepare the cells for scanning electron microscopy, see reference 33). These pictures, taken at different magnifications, demonstrated again the targeting of cells by SOF-coated beads (Fig. 3A and B) and also revealed the putative involvement of SOF in the internalization process (Fig. 3C and D). The white arrows in Fig. 3C and D point to particles that are at various stages of the internalization process. The specificity of the interaction was confirmed by incubation of bovine serum albumin-coated beads with HEp-2 cells, which neither adhered to cells in significant numbers nor were internalized (data not shown).

FIG. 3.

Scanning electron microscopic analysis of the interaction of SOF75 (recombinant HT1)-coated latex beads with HEp-2 cells. Beads are at different stages of adherence (A, B) and internalization (C, D). White arrows point to internalized beads. Bars, 2 μm.

In summary, these experiments indirectly indicated the function of SOF as a eukaryotic cell adhesin. The presence of the fibronectin-binding repeat region of SOF appeared to be crucial for the adherence process. No other SOF domain could support this adherence function. This again distinguished SOF from the SfbI MSCRAMM and suggested that the adherence process is fibronectin dependent. On the basis of our experiments, it is not possible to finally decide whether SOF is also involved in host cell internalization mechanisms, as described as a major function of SfbI. However, if SOF plays a role in host cell internalization, the process probably differs from the SfbI-mediated pathway (47) because in the case of SfbI the fibronectin-binding spacer region was required in addition to the repeat region for efficient uptake. This domain was not present on any of the SOF molecules described so far (1, 8, 26, 40).

In subsequent qualitative experiments, particles coated with recombinant HT1 were tested for adherence to different cell lines (all seated in six-well plates at 106 cells per well) in order to investigate the cell type specificity of the adherence process. SOF supported the adherence of beads to Ptk2 cells, 3T3 fibroblasts, and WI38 fibroblasts in addition to its function in HEp-2 cell adherence (data not shown). HeLa and A549 epithelial cells did not provide a substrate for particle adherence (data not shown). A possible explanation could be that these cell lines did not express fibronectin on their surface or did not acquire fibronectin from the cell culture medium, thereby lacking the target matrix molecule for adherence.

Cell surface-bound fibronectin is the target for adherence of bead-coated SOF75.

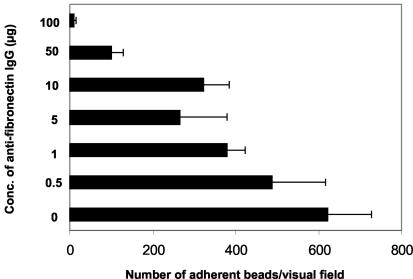

To distinctly link the SOF-bead adherence with the presence of fibronectin as the cellular binding partner, which bridges the SOF-coated beads to the respective integrins on the cell surface, we used antifibronectin antibodies as an inhibitor of this interaction. HEp-2 cells were preincubated with increasing amounts of antifibronectin immunoglobulin G (IgG; Biomol GmbH, Hamburg, Germany) for 1 h before the beads were allowed to adhere to the cells. The number of adherent beads per microscopic field was determined in three fields per assay in three independent experiments. The data summarized in Fig. 4 showed that increasing amounts of the inhibitor led to a reduced number of adherent beads. This clearly identifies fibronectin as a cellular component of adherence of SOF-coated beads and again confirms that SOF75 is a fibronectin-binding MSCRAMM.

FIG. 4.

Inhibition of SOF-coated latex bead adherence to HEp-2 cell monolayers with increasing amounts of antifibronectin IgGs (Biomol GmbH, Hamburg, Germany). Cell monolayers were pretreated with the antibodies for 1 h prior to bead adherence. Data represent the means of three individual assays, and error bars represent the standard deviation. The total number of beads from three microscopic fields (×400 magnification) was determined per IgG concentration (Conc.) and assay.

Inhibition of GAS adherence to HEp-2 cells by specific SOF antibodies.

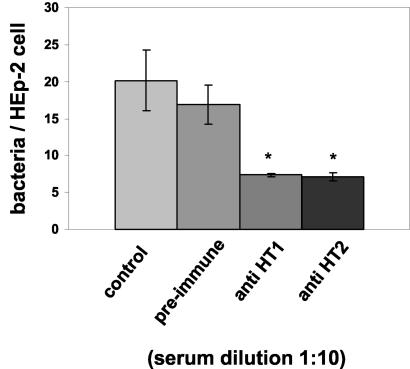

In order to directly evaluate the involvement of SOF in GAS adherence, we performed adherence assays with a strain (A27, tonsillitis isolate) that lacked SfbI expression. Owing to the redundancy of fibronectin-binding proteins in GAS, we anticipated to observe more specific effects of SOF in this genetic background. For the assay, confluent monolayers of HEp-2 cells were infected with GAS strain A27 at a multiplicity of infection of 25, incubated for 1 h, and subsequently stained with Giemsa. The number of adherent bacteria per 50 cells was determined by light microscopy. For inhibition experiments, bacteria were pretreated either with antibodies generated against recombinant HT1 or HT2 or with preimmune serum as a control.

A 50% reduction in the number of adherent bacteria was observed for inhibition with both types of anti-SOF sera (Fig. 5). The anti-HT2 antiserum only recognized the SOF enzymatic domain. Its effectiveness at inhibition could be attributed to specific binding to the SOF enzymatic domain on the surface of the bacteria, thereby causing a steric hindrance for the SOF fibronectin-binding repeat region, which was not accessible for fibronectin interaction. The anti-HT1 antiserum is directed against the entire mature protein, and therefore the observed effect on adherence could be a mixture of specific blockage of the SOF fibronectin-binding domain and unspecific steric hindrance of the adhesion process.

FIG. 5.

Inhibition of GAS adherence to HEp-2 cells by anti-SOF antibodies. Bacteria were preincubated with preimmune serum or anti-HT1 or anti-HT2 antiserum prior to HEp-2 cell adherence. Data shown as bars marked with asterisks are significantly different (α, 5%) from controls according to Mann-Whitney U tests.

Conclusions.

The results from this study strongly indicate that SOF fulfills some function in the GAS-host cell adherence process. The SOF molecule contains a domain to specifically target the N-terminal 30-kDa portion of the fibronectin molecule, as shown by binding experiments, latex particle adherence assays, and inhibition experiments. However, the 45-kDa gelatin-collagen-binding module of fibronectin was no target for the SOF-mediated attachment. Thus, unlike SfbI, which binds to both fibronectin portions, SOF-mediated internalization may not require the 45-kDa fibronectin fragment. The association and dissociation constants of the SOF-fibronectin binding process revealed a less tight and lasting interaction compared to the kinetic data of other GAS MSCRAMMs. The question remains of whether SOF plays a major or minor role in GAS adherence to and internalization in epithelial cells in general. As shown here, anti-SOF antibodies moderately inhibited the adherence of GAS strain A27 to HEp-2 cells. If this was a strain-specific result or could be found with SOF molecules from different M serotype strains needs to be elucidated in future experiments. GAS with double and triple mutations in genes encoding fibronectin-binding proteins, as well as complemented strains expressing single genes in the isogenic background, should aid in dissecting the precise role of each of the known fibronectin-binding proteins in GAS pathogenesis.

Acknowledgments

We thank Singh Chhatwal, Susanne Talay, Manfred Rohde, Peter Valentin-Weigand, and Gabriella Molinari for helpful comments and Jana Normann, Yvonne Humbold, and Britta Becizszka for expert technical assistance.

This work was supported by grants from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (Kr1765/2-1, Po391/8-2, and Po391/9-1).

Editor: V. J. DiRita

REFERENCES

- 1.Beall, B., G. Gherardi, M. Lovgren, R. R. Facklam, B. A. Forwick, and G. J. Tyrrell. 2000. emm and sof gene sequence variation in relation to serological typing of opacity-factor-positive group A streptococci. Microbiology (Reading) 146:1195-1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bergmann, S., D. Wild, O. Diekmann, R. Frank, D. Bracht, G. S. Chhatwal, and S. Hammerschmidt. 2003. Identification of a novel plasmin(ogen)-binding motif in surface displayed α-enolase of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Mol. Microbiol. 49:411-423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brandt, C. M., F. Allerberger, B. Spellerberg, R. Holland, R. Lütticken, and G. Haase. 2001. Characterization of consecutive Streptococcus pyogenes isolates from patients with pharyngitis and bacteriological treatment failure: special reference to prtF1 and sic/drs. J. Infect. Dis. 183:670-674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cleary, P. P., and D. Cue. 2000. High frequency invasion of mammalian cells by β-haemolytic streptococci. Subcell. Biochem. 33:137-166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Courtney, H. S., J. B. Dale, and D. L. Hasty. 1996. Differential effects of the streptococcal fibronectin-binding protein, FBP54, on adhesion of group A streptococci to human buccal cells and HEp-2 tissue culture cells. Infect. Immun. 64:2415-2419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Courtney, H. S., J. B. Dale, and D. L. Hasty. 2002. Mapping the fibrinogen-binding domain of serum opacity factor of group A streptococci. Curr. Microbiol. 44:236-240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Courtney, H. S., D. L. Hasty, and J. B. Dale. 2002. Molecular mechanisms of adhesion, colonization, and invasion of group A streptococci. Ann. Med. 34:77-87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Courtney, H. S., D. L. Hasty, Y. Li, H. C. Chiang, J. L. Thacker, and J. B. Dale. 1999. Serum opacity factor is a major fibronectin-binding protein and a virulence determinant of M type 2 Streptococcus pyogenes. Mol. Microbiol. 32:89-98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Courtney, H. S., D. L. Hasty, and J. B. Dale. 2003. Serum opacity factor (SOF) of Streptococcus pyogenes evokes antibodies that opsonize homologous and heterologous SOF-positive serotypes of group A streptococci. Infect. Immun. 71:5097-5103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cue, D., H. Lam, and P. P. Cleary. 2001. Genetic dissection of the Streptococcus pyogenes M1 protein: regions involved in fibronectin binding and intracellular invasion. Microb. Pathog. 31:231-242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cue, D., P. E. Dombek, H. Lam, and P. P. Cleary. 1998. Streptococcus pyogenes serotype M1 encodes multiple pathways for entry into human epithelial cells. Infect. Immun. 66:4593-4601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cunningham, M. W. 2000. Pathogenesis of group A streptococcal infections. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 13:470-511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dombek, P. E., D. Cue, J. Sedgewick, H. Lam, S. Ruschkowski, B. B. Finlay, and P. P. Cleary. 1999. High-frequency intracellular invasion of epithelial cells by serotype M1 group A streptococci: M1 protein-mediated invasion and cytoskeletal rearrangements. Mol. Microbiol. 31:859-870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frick, I. M., P. Akesson, J. Cooney, U. Sjöbring, K. H. Schmidt, H. Gomi, S. Hattori, C. Tagawa, F. Kishimoto, and L. Björck. 1994. Protein H—a surface protein of Streptococcus pyogenes with separate binding sites for IgG and albumin. Mol. Microbiol. 12:143-151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gillen, C. M., R. J. Towers, D. J. McMillan, A. Delvecchio, K. S. Sriprakash, B. Currie, B. Kreikemeyer, G. S. Chhatwal, and M. J. Walker. 2002. Immunological response mounted by aboriginal Australians living in the Northern Territory of Australia against Streptococcus pyogenes serum opacity factor. Microbiology (Reading) 148:169-178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goodfellow, A. M., M. Hibble, S. R. Talay, B. Kreikemeyer, B. J. Currie, K. S. Sriprakash, and G. S. Chhatwal. 2000. Distribution and antigenicity of fibronectin binding proteins (SfbI and SfbII) of Streptococcus pyogenes clinical isolates from the Northern Territory, Australia. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:389-392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hanski, E., and M. Caparon. 1992. Protein F, a fibronectin-binding protein, is an adhesin of the group A streptococcus (Streptococcus pyogenes). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89:6172-6176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jadoun, J., V. Ozeri, E. Burstein, E. Skutelsky, E. Hanski, and S. Sela. 1998. Protein F1 is required for efficient entry of Streptococcus pyogenes into epithelial cells. J. Infect. Dis. 178:147-158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jaffe, J., S. Natanson-Yaron, M. G. Caparon, and E. Hanski. 1996. Protein F2, a novel fibronectin-binding protein from Streptococcus pyogenes, possesses two binding domains. Mol. Microbiol. 21:373-384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jeng, A., V. Sakota, Z. Li, V. Datta, B. Beall, and V. Nizet. 2003. Molecular genetic analysis of a group A Streptococcus operon encoding serum opacity factor and a novel fibronectin-binding protein, SfbX. J. Bacteriol. 185:1208-1217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Joh, H. J., K. House-Pompeo, J. M. Patti, S. Gurusiddappa, and M. Hook. 1994. Fibronectin receptors from gram-positive bacteria: comparison of active sites. Biochemistry 33:6086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johnson, D. R., and E. L. Kaplan. 1988. Microtechnique for serum opacity factor characterization of group A streptococci adaptable to the use of human sera. J. Clin. Microbiol. 26:2025-2030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Katerov, V., A. Andreev, C. Schalen, and A. A. Totolian. 1998. Protein F, a fibronectin-binding protein of Streptococcus pyogenes, also binds human fibrinogen: isolation of the protein and mapping of the binding region. Microbiology (Reading) 144:119-126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Katerov, V., P. E. Lindgren, A. A. Totolian, and C. Schalen. 2000. Streptococcal opacity factor: a family of bifunctional proteins with lipoproteinase and fibronectin-binding activities. Curr. Microbiol. 40:149-156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kreikemeyer, B., S. Beckert, A. Braun-Kiewnick, and A. Podbielski. 2002. Group A streptococcal RofA-type global regulators exhibit a strain-specific genomic presence and regulation pattern. Microbiology (Reading) 148:1501-1511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kreikemeyer, B., D. R. Martin, and G. S. Chhatwal. 1999. SfbII protein, a fibronectin binding surface protein of group A streptococci, is a serum opacity factor with high serotype-specific apolipoproteinase activity. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 178:305-311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kreikemeyer, B., S. R. Talay, and G. S. Chhatwal. 1995. Characterization of a novel fibronectin-binding surface protein in group A streptococci. Mol. Microbiol. 17:137-145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kreikemeyer, B., S. Oehmcke, M. Nakata, R. Hoffrogge, and A. Podbielski. 28. January 2004. Streptococcus pyogenes fibronectin-binding protein F2: expression profile, binding characteristics and impact on eukaryotic cell interactions. J. Biol. Chem. 10.1074/jbc.M313613200. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.LaPenta, D., C. Rubens, E. Chi, and P. P. Cleary. 1994. Group A streptococci efficiently invade human respiratory epithelial cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91:12115-12119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maxted, W. R., J. P. Widdowson, C. A. M. Fraser, L. C. Ball, and D. J. C. Bassett. 1973. The use of the serum opacity reaction in the typing of group A streptococci. J. Med. Microbiol. 6:83-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McLandsborough, L. A., and P. P. Cleary. 1995. Insertional inactivation of virR in Streptococcus pyogenes M49 demonstrates that VirR functions as a positive regulator of ScpA, FcRA, OF, and M protein. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 128:45-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Molinari, G., and G. S. Chhatwal. 1999. Streptococcal invasion. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2:56-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Molinari, G., S. R. Talay, P. Valentin-Weigand, M. Rohde, and G. S. Chhatwal. 1997. The fibronectin-binding protein of Streptococcus pyogenes, SfbI, is involved in the internalization of group A streptococci by epithelial cells. Infect. Immun. 65:1357-1363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Neeman, R., N. Keller, A. Barzilai, Z. Korenman, and S. Sela. 1998. Prevalence of internalization-associated gene, prtF1, among persisting group-A Streptococcus strains isolated from asymptomatic carriers. Lancet 352:1974-1977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ozeri, V., I. Rosenshine, D. F. Mosher, R. Fässler, and E. Hanski. 1998. Roles of integrins and fibronectin in the entry of Streptococcus pyogenes into cells via protein F1. Mol. Microbiol. 30:625-637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ozeri, V., A. Tovi, I. Burstein, S. Natanson-Yaron, M. G. Caparon, K. M. Yamada, S. K. Akiyama, I. Vlodavsky, and E. Hanski. 1996. A two-domain mechanism for group A streptococcal adherence through protein F to the extracellular matrix. EMBO J. 15:989-998. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Patti J. M., J. O., Boles, and M. Hook. 1993. Identification and biochemical characterization of the ligand binding domain of the collagen adhesin from Staphylococcus aureus. Biochemistry 32:11428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Patti, J. M., B. L. Allen, M. J. McGavin, and M. Höök. 1994. MSCRAMM-mediated adherence of microorganisms to host tissue. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 48:585-617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Podbielski, A., M. Woischnik, B. Pohl, and K. H. Schmidt. 1996. What is the size of the group A streptococcal vir regulon? The Mga regulator affects expression of secreted and surface virulence factors. Med. Microbiol. Immunol. 185:171-181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rakonjac, J. V., J. C. Robbins, and V. A. Fischetti. 1995. DNA sequence of the serum opacity factor of group A streptococci: identification of a fibronectin-binding repeat domain. Infect. Immun. 63:622-631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rocha, C. L., and V. A. Fischetti. 1999. Identification and characterization of a novel fibronectin-binding protein on the surface of group A streptococci. Infect. Immun. 67:2720-2728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Saravani, G. A., and D. R. Martin. 1990a. Characterization of opacity factor from group A streptococci. J. Med. Microbiol. 33:55-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Saravani, G. A., and D. R. Martin. 1990b. Opacity factor from group A streptococci is an apoproteinase. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 68:35-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sela, S., A. Aviv, A. Tovi, I. Burstein, M. G. Caparon, and E. Hanski. 1993. Protein F: an adhesin of Streptococcus pyogenes binds fibronectin via two distinct domains. Mol. Microbiol. 10:1049-1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Talay, S. R., P. Valentin-Weigand, P. G. Jerlström, K. N. Timmis, and G. S. Chhatwal. 1992. Fibronectin-binding protein of Streptococcus pyogenes: sequence of the binding domain involved in adherence of streptococci to epithelial cells. Infect. Immun. 60:3837-3844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Talay, S. R., P. Valentin-Weigand, K. N. Timmis, and G. S. Chhatwal. 1994. Domain structure and conserved epitopes of Sfb protein, the fibronectin-binding adhesin of Streptococcus pyogenes. Mol. Microbiol. 13:531-539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Talay, S. R., A. Zock, M. Rohde, G. Molinari, M. Oggioni, G. Pozzi, C. A. Guzman, and G. S. Chhatwal. 2000. Co-operative binding of human fibronectin to SfbI protein triggers streptococcal invasion into respiratory epithelial cells. Cell. Microbiol. 2:521-535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Terao, Y., S. Kawabata, E. Kunitomo, J. Murakami, I. Nakagawa, and S. Hamada. 2001. Fba, a novel fibronectin-binding protein from Streptococcus pyogenes, promotes bacterial entry into epithelial cells, and the fba gene is positively transcribed under the Mga regulator. Mol. Microbiol. 42:75-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Terao, Y., S. Kawabata, M. Nakata, I. Nakagawa, and S. Hamada. 2002. Molecular characterization of a novel fibronectin-binding protein of Streptococcus pyogenes strains isolated from toxic shock-like syndrome patients. J. Biol. Chem. 277:47428-47435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Valentin-Weigand, P., S. R. Talay, A. Kaufhold, K. N. Timmis, and G. S. Chhatwal. 1994. The fibronectin binding domain of the Sfb protein adhesin of Streptococcus pyogenes occurs in many group A streptococci and does not cross-react with heart myosin. Microb. Pathog. 17:111-120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ward, H. K., and G. V. Rudd. 1938. Studies on hemolytic streptococci from human sources. Aust. J. Exp. Biol. Med. Sci. 16:181-192. [Google Scholar]