Abstract

Burkholderia pseudomallei is the causative agent of melioidosis. Burkholderia thailandensis is a closely related species that can readily utilize l-arabinose as a sole carbon source, whereas B. pseudomallei cannot. We used Tn5-OT182 mutagenesis to isolate an arabinose-negative mutant of B. thailandensis. Sequence analysis of regions flanking the transposon insertion revealed the presence of an arabinose assimilation operon consisting of nine genes. Analysis of the B. pseudomallei chromosome showed a deletion of the operon from this organism. This deletion was detected in all B. pseudomallei and Burkholderia mallei strains investigated. We cloned the B. thailandensis E264 arabinose assimilation operon and introduced the entire operon into the chromosome of B. pseudomallei 406e via homologous recombination. The resultant strain, B. pseudomallei SZ5028, was able to utilize l-arabinose as a sole carbon source. Strain SZ5028 had a significantly higher 50% lethal dose for Syrian hamsters compared to the parent strain 406e. Microarray analysis revealed that a number of genes in a type III secretion system were down-regulated in strain SZ5028 when cells were grown in l-arabinose, suggesting a regulatory role for l-arabinose or a metabolite of l-arabinose. These results suggest that the ability to metabolize l-arabinose reduces the virulence of B. pseudomallei and that the genes encoding arabinose assimilation may be considered antivirulence genes. The increase in virulence associated with the loss of these genes may have provided a selective advantage for B. pseudomallei as these organisms adapted to survival in animal hosts.

Burkholderia pseudomallei is an environmental saprophyte that has been isolated widely from soil in Southeast Asia, and the relationship between environmental contamination and clinical melioidosis has been established. White and colleagues reported that two distinct types of B. pseudomallei, differentiated by the ability to assimilate l-arabinose but with similar morphologies and antigenicities, could be isolated from soil in Thailand and that the arabinose assimilation property of B. pseudomallei was one of the determinants indicating virulence of this organism (31). Subsequently, our investigators designated the arabinose-positive B. pseudomallei biotype as a separate species, Burkholderia thailandensis, based upon a number of significant genetic and phenotypic dissimilarities between B. pseudomallei and B. thailandensis, including differences in 16S rRNA, arabinose assimilation, ethanol assimilation, and secreted protein profiles (8).

Ongoing discussions surround the evolutionary relationships among the Burkholderia spp., particularly regarding the origins of B. thailandensis, B. pseudomallei, and B. mallei and their relationships to one another. The most prevalent view is that B. pseudomallei and B. thailandensis evolved from a common ancestor, probably a soil saprophyte. Spratt and colleagues have recently proposed that B. mallei is a clone of B. pseudomallei, based upon results from multilocus sequence typing of a large number of B. pseudomallei strains but only a small number of B. mallei strains (17). Thus, it is conceivable that B. mallei could have evolved from B. pseudomallei. What is clear, however, is that B. pseudomallei and B. mallei are significant pathogens while B. thailandensis is not, and neither B. pseudomallei nor B. mallei assimilates arabinose.

In the present studies, we provide experimental data that arabinose assimilation is an antivirulence property, and the genes encoding arabinose assimilation should be termed antivirulence genes. Maurelli and colleagues initially defined the concept of gene loss in the evolution of bacterial pathogens from commensals as a mechanism of fine-tuning pathogen genomes for maximal fitness in new host environments (22). In our studies, we have examined the nature of the genes comprising the B. thailandensis arabinose assimilation operon and how deletion of these genes has contributed to the evolution of B. pseudomallei and B. mallei as pathogens.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are described in Table 1. In addition to those listed in Table 1, the following B. pseudomallei strains were used: K96243, 1026b, 576, E8, E12, E13, 112c, 238, 295, 296, 713, and 730. Additional B. thailandensis strains included E27, E30, E32, E96, E100, E105, E111, E120, E125, E132, and E135. Additional B. mallei strains included NCTC 10248, NCTC 10229, NCTC 10260, NCTC 10247, NCTC 120, and ATCC 23344. Bacterial strains were routinely grown at 37°C in Luria-Bertani broth (LB) or on LB agar plates. In some cases M9 broth (Difco) or M9 agar was used with filter-sterilized carbon sources added to a final concentration of 0.4 or 1.0%. Bacteria used for microarray analysis were grown in M9 supplemented with the appropriate carbon source at 1.0% and harvested during exponential growth. Antibiotics were used at the following concentrations for B. pseudomallei and B. thailandensis: polymyxin B (PXB), 100 μg/ml; gentamicin (GEN) and kanamycin, 25 μg/ml; and tetracycline (TET), 50 μg/ml. For Escherichia coli the following antibiotics were used: ampicillin and carbenicillin, 100 μg/ml; GEN and kanamycin, 25 μg/ml; and TET, 15 μg/ml.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Description | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli strains | ||

| HB101 | General cloning | 6 |

| TOP10 | General cloning and blue-white screening | Invitrogen |

| SM10λpir | SM10 with a λ prophage carrying the π protein; Kmr | 30 |

| B. thailandensis strains | ||

| E264 | Soil isolate from central Thailand | 7 |

| DW503 | E264 derivative; Δ(amr-oprA) rpsL (Smr) Tcs | 9 |

| DD5026 | E264::pDD157; Tcr | This study |

| RM600 | DW503 derivative; araC::Tn-5OT182 Ara− Tcr | This study |

| RM601 | DW503 derivative; araC::pGSV3-lux Gmr | This study |

| RM602 | DW503 derivative; araE::pGSV3-lux Gmr | This study |

| RM603 | DW503 derivative; araI::pGSV3 Gmr | This study |

| RM604 | DW503 derivative; araA::pGSV3 Gmr | This study |

| B. pseudomallei strains | ||

| 1026b | Clinical isolate; AGr Tcs | 12 |

| K96243 | ||

| DD503 | 1026b derivative; Δ(amrR-oprA) rpsL (Smr) AGs Tcs | 24 |

| 406e | Tcs | Clinical isolate, Thailand |

| 316c | Tcs | Clinical isolate, Thailand |

| SZ5026 | 406e::pDD157; Tcr | This study |

| SZ5028 | 406e::pDD5026H; Tcr | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pDD157 | 1,136-bp araA cloned into pSKM11; Apr Tcr | This study |

| pDD5026H | 13.5-kb arabinose assimilation operon from DD5026 in pSKM11 via self-cloning; Apr Tcr | This study |

| pCR2.1-TOPO | 3.9-kb TA cloning vector; pMB1 oriR; Apr Kmr | Invitrogen |

| pGSV3 | Mobilizable suicide vector; OriT Gmr | 10 |

| pGSV3-lux | Mobilizable suicide vector containing lux operon from pSC26; OriT Gmr | This study |

| pCS26-Pac | Reporter plasmid containing luxCDABE of Photorhabdus luminescens | 4 |

| pRM601Int | pGSV3-lux containing 465-bp internal fragment from araC, used to construct RM601 | This study |

| pRM602Int | pGSV3-lux containing 676-bp internal fragment from araE, used to construct RM602 | This study |

| pRK2013 | Self-transmissible helper plasmid; Kmr | 16 |

| pSKM11 | Mobilizable suicide vector; Tcr Ampr | 23 |

Tn5-OT182 mutagenesis and isolation of an l-arabinose utilization mutant.

To identify genes involved in arabinose utilization, B. thailandensis E264 was mutagenized with Tn5-OT182 (12), and mutants unable to grow using l-arabinose as a sole carbon source were identified. Tn5-OT182 mutagenesis was performed as previously described, except that transposon mutants were selected on LB agar containing PXB and TET. Mutants were subsequently replica plated to LB-TET and M9-TET-arabinose agar plates. Colonies unable to grow on arabinose plates were tested for growth on M9-glucose to eliminate mutants which were generally defective in carbohydrate metabolism. One mutant, RM600, was isolated that was able to grow on LB and M9-glucose but not on M9-arabinose.

DNA sequencing and analysis.

DNA flanking the Tn5-OT182 integration in RM600 was isolated by self-cloning and was sequenced by the University Core DNA Services (University of Calgary, Calgary, Alberta, Canada) and by ACGT, Inc. (Northbrook, Ill.). BLAST analysis (1) of the sequenced DNA was performed using programs provided by the National Center for Biotechnology Information.

Construction of pGSV3 insertional inactivation mutants.

Specific arabinose assimilation operon genes were insertionally inactivated using the GEN-resistant suicide vector pGSV3 (Table 1) (10). Typically, an approximately 500-bp internal region of the target gene was PCR amplified and cloned into pCR2.1-TOPO (Invitrogen). The cloned fragment was excised using EcoRI, gel purified, and ligated into EcoRI-restricted, calf intestinal phosphatase (CIP)-treated pGSV3. A portion of the ligation was transformed into chemically competent E. coli TOP10 cells, and cells were plated onto LB-GEN selective medium. Transformants were screened for the pGSV3-containing insert, and plasmid DNA from positive clones was then used to transform E. coli SM10λpir. Plasmids were then conjugated into B. thailandensis DW503, and transconjugants with pGSV3 integrated in the chromosome via homologous recombination were selected on LB-GEN-PXB medium. Confirmation of the proper insertional inactivation event was performed by PCR with one of the primers originally used to amplify the internal fragment and a primer internal to pGSV3.

Construction of pGSV3-lux and lux fusions.

The lux-based suicide vector pGSV3-lux was constructed by excising the lux operon from pCS26-Pac and ligating it into the NotI Site in pGSV3. pCS26-Pac was digested with NotI and electrophoresed on a 1% agarose gel. A 5.8-kb band corresponding to the lux operon was excised from the gel, purified, and ligated into NotI-digested, CIP-treated pGSV3. The ligation mix was used to transform chemically competent E. coli TOP10 cells, and transformants were subsequently screened for lux-mediated light production to identify clones containing a functional lux operon. Light production was measured from 200 μl of cells using a SystemSure luminometer (Nova Biomedical, Waltham, Mass.). The orientation of the lux operon was determined using PCR.

lux fusions were constructed in a similar manner as the pGSV3 insertional inactivation mutants. An internal region of approximately 500 bp was PCR amplified from the sequence encoding arabinose dehydogenase (araE) and the sequence encoding α-ketoglutarate semialdehyde dehydrogenase (α-KSAD; araC) and cloned into pCR2.1-TOPO. The PCR products were excised from pCR2.1-TOPO and ligated into EcoRI-digested, CIP-treated pGSV3-lux as described above and transformed into E. coli SM10λpir. Conjugations with E. coli SM10λpir(pRM602Int) and E. coli SM10λpir(pRM601Int) with B. thailandensis DW503 were performed, and transconjugants were selected on LB-GEN-PXB agar. Transconjugants were screened for lux-mediated light production by assaying 200 μl of overnight broth cultures of individual colonies. Cultures which displayed light production were then tested for insertion of pGSV3-lux into the target gene using PCR as described above. Representative mutants RM601 and RM602 were chosen for further study.

Induction of arabinose dehydrogenase and α-KSAD in B. thailandensis.

Five-hundred-milliliter flasks containing 50 ml of LB broth were inoculated with 1 ml of an overnight culture of RM601 or RM602 grown in LB broth. The cultures were allowed to grow for 3 h, at which point glucose alone, glucose and arabinose, or arabinose alone was added to a final concentration of 0.2%. Optical density at 600 nm and lux-mediated light production were measured hourly for 6 h.

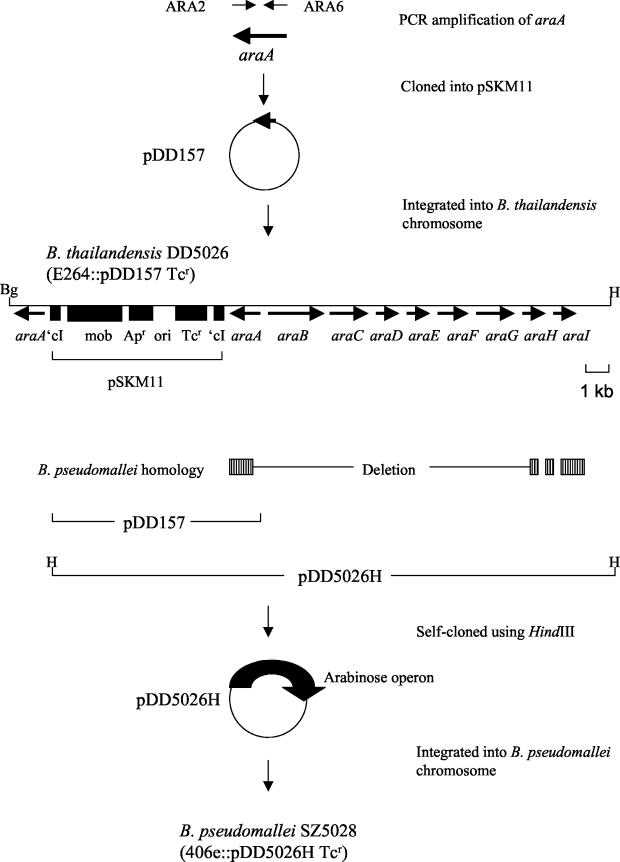

Construction of B. pseudomallei SZ5026 and SZ5028.

The construction of B. pseudomallei strains harboring arabinose genes from B. thailandensis E264 DNA integrated into their chromosomes is shown schematically in Fig. 5, below. The transcriptional regulator gene (araA) from the B. thailandensis arabinose assimilation operon was PCR amplified. A 1,133-bp PCR product was generated with primers ARA2 and ARA6 and E264 chromosomal DNA. This PCR product was cloned into pCR2.1-TOPO (Invitrogen) and then cloned as an EcoRI fragment into the mobilizable suicide vector pSKM11 to produce the plasmid pDD157. E. coli TOP10(pDD157) was conjugated to B. thailandensis E264 using the triparental mating protocol described below. The resulting B. thailandensis strain DD5026 was generated by integrating pDD157 into the E264 chromosome. The plasmid pDD5026H containing pSKM11 and the entire arabinose assimilation operon from B. thailandensis was obtained by self-cloning with the restriction enzyme HindIII, which acts outside of the arabinose assimilation operon (see Fig. 5). This plasmid was transformed into E. coli TOP10 and conjugated into B. pseudomallei 406e to produce an arabinose-utilizing strain of B. pseudomallei. The resulting arabinose-utilizing strain, B. pseudomallei SZ5028, was obtained after integration of pDD5026H into a homologous region of the 406e chromosome (see Fig. 5).

FIG. 5.

Construction of the arabinose-utilizing B. pseudomallei strain SZ5028. The transcriptional regulator gene (araA) from the B. thailandensis arabinose assimilation operon was amplified using PCR. A 1,133-bp PCR product was generated with primers ARA6 and ARA2 and E264 chromosomal DNA. This PCR product was cloned into the suicide vector pSKM11 to produce the plasmid pDD157. The B. thailandensis strain DD5026 was generated by integrating pDD157 into the E264 chromosome. The plasmid pDD5026H was obtained by self-cloning with the restriction enzyme HindIII. This plasmid contains pSKM11 and the entire arabinose assimilation operon from B. thailandensis. pDD5026H was transformed and conjugated to B. pseudomallei 406e to produce an arabinose-utilizing strain of B. pseudomallei. The resulting strain, B. pseudomallei SZ5028, was obtained by integrating pDD5026H into the 406e chromosome. The locations and names of the arabinose genes from B. thailandensis are indicated, and the direction of transcription is represented by arrows. The region of homology between B. thailandensis and B. pseudomallei is indicated. The plasmids pDD157 and pDD5026H are illustrated. The locations of relevant restriction endonuclease recognition sites (Bg, BglII; H, HindIII) are shown.

Conjugal transfer of plasmids pDD157 and pDD5026H into B. pseudomallei.

The strains E. coli TOP10(pDD157) and E. coli TOP10(pDD5026H) were mated with B. pseudomallei using a triparental mating procedure. Briefly, 200 μl of an overnight culture of E. coli HB101(pRK2013), B. pseudomallei 406e, and either E. coli TOP10(pDD157) or E. coli TOP10(pDD5026H) was centrifuged separately at 1,600 × g for 1 min and washed two times with sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (13). Each pellet was resuspended in a final volume of 100 μl of PBS, and the three resuspended pellets, corresponding to the mating being performed, were combined into one microcentrifuge tube and mixed well. The entire mixture was spread onto an LB-10 mM MgSO4 plate, and the plate was incubated at 37°C for 24 h. The next day, bacteria were scraped off the plate and resuspended in 1 ml of PBS, and 100-μl aliquots were plated onto LB plates containing PXB (100 μg/ml) and TET (50 μg/ml) and incubated at 37°C for 48 h. The Pxr Tcr transconjugants were then plated on M9 medium containing 0.4% arabinose as the sole carbon source to determine if the conjugations resulted in an arabinose-utilizing strain of B. pseudomallei.

Utilization of arabinose by B. pseudomallei and B. thailandensis.

Bacteria were inoculated from LB plates into M9 medium containing 0.4% arabinose as the sole carbon source or onto M9 plus 0.4% arabinose plates. After 24 and 48 h of growth at 37°C with shaking, the absorbance values (optical density at 600 nm [OD600]) of the M9 plus 0.4% arabinose cultures were determined. Growth on arabinose plates was determined following incubation of the plates at 37°C for 48 h.

PCR amplification.

The araA gene was amplified from B. thailandensis E264 chromosomal DNA via PCR. The oligodeoxyribonucleotide primers used for the amplification of araA were ARA6 (5′-GAATCTGAGCGCAGCTATTG-3′) and ARA2 (5′-CATGGGTGCCGAACCATTGG-3′). PCR amplification was performed in a 50-μl reaction mixture containing 1× HotStarTaq PCR Master mix (QIAGEN, Missiauga, Ontario, Canada), 1× Q-solution (QIAGEN), a 0.5 μM concentration of each primer, and 100 ng of genomic DNA. The mixture was placed in a GeneAmp PCR system 9600 (Perkin-Elmer Cetus) thermal cycler and subjected to a 5-min denaturation step at 95°C followed by 30 cycles of 95°C for 45 s, 56°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 90 s. The reaction mixture was held at 72°C for 10 min and then placed at 4°C until analyzed on a 1% agarose gel. ARA1 (5′-ACGACGACGTCGAGCTTGTC-3′) and ARA3 (5′-CGACGAAGCCGACGATGTTG-3′) were used to amplify the deletion termini of the arabinose utilization genes of B. pseudomallei K96243 and B. mallei ATCC 23344. A PCR experiment was performed to confirm the integration of pDD5026H (arabinose assimilation operon) into the B. pseudomallei SZ5028 chromosome. ARA6 and ARA2 primers were used to amplify the 1,136-bp araA gene from B. pseudomallei SZ5026 and SZ5028 and B. thailandensis E264. B. pseudomallei 406e was used as a negative control. The primers ARA-F (5′-GCGGTACCGAATCTGAGCGCAGCTATTG-3′) and ARA-R2 (5′-GCGGTACCTGCCATCGGCGATTTGTAAT-3′) were used to amplify the entire arabinose operon from B. pseudomallei SZ5028 and B. thailandensis E264. B. pseudomallei SZ5028 and 406e were used as negative controls. Long-distance PCR was performed using the FailSafe PCR PreMix selection kit (EpiCenter, Madison, Wis.). Reaction mixtures were cycled in a GeneAmp PCR system 9600 thermal cycler and subjected to a 2-min denaturation step at 95°C followed by 30 cycles of 95°C for 45 s, 59°C for 45 s, and 72°C for 1 min/kb of expected PCR product. The reaction mixture was held at 72°C for 10 min and then held at 4°C until analyzed.

DNA manipulation.

Restriction enzymes and T4 DNA ligase were purchased from Invitrogen Life Technologies (Burlington, Ontario, Canada) and New England BioLabs (Mississauga, Ontario, Canada) and used according to the manufacturers' instructions. Chromosomal DNA was isolated using a Wizard genomic DNA purification kit (Promega Corporation, Madison, Wis.). Plasmid DNA was isolated using a QIAprep Spin miniprep kit (QIAGEN). DNA fragments used in cloning procedures were excised from agarose gels and purified using a QIAGEN gel extraction kit. PCR products were cloned into pCR2.1-TOPO using the TOPO TA cloning kit and chemically competent E. coli TOP10 cells (Invitrogen Life Technologies) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The self-cloning of DNA from Tn5-OT182 mutants and from the insertion of pDD157 in B. thailandensis DD5026 was performed as described previously (14).

Animal studies.

The animal model of acute B. pseudomallei infection has been previously described (11). Bacteria were grown overnight in LB broth and LB plus 0.4% arabinose with 50 μg of TET/ml for B. pseudomallei SZ5026 and SZ5028 at 37°C with shaking. The following day, 3 ml of medium was inoculated with 100 μl of the overnight cultures, and the bacteria were grown to logarithmic phase (4 to 5 h). The OD600 values were determined, and the cultures were adjusted to an OD600 of approximately 0.55 (5 × 108 CFU/ml). Serial dilutions of the cultures were prepared in sterile PBS, and female hamsters 6 to 8 weeks old were inoculated intraperitoneally with 100 μl of bacteria corresponding to inoculum sizes of 10, 50, 100, and 1,000 CFU. Hamsters were also injected intraperitoneally with 1 mg (100 μl of a 10-mg/ml solution) of TET at time zero and at 24 h to ensure the stability of the plasmids pDD157 and pDD5026H integrated in the B. pseudomallei chromosome. After 48 h, the 50% lethal dose (LD50) values were calculated (27).

Microarray analysis: total RNA isolation.

Total bacterial RNA was isolated from liquid culture using the RNAwiz reagent (Ambion Inc.) with some modifications. Prior to harvesting the cells, RNAlater solution (Ambion Inc.) was added to the broth culture (1:100 [vol/vol]), in order to protect the RNA from degradation. Bacteria were collected by centrifugation at 3,000 × g for 5 min at 4°C. One milliliter of RNAwiz reagent was added to the cell pellet (approximately 1010 cells), mixed thoroughly by pipetting, and incubated at room temperature for 5 min. Chloroform (0.5 ml) was added to the tube, mixed thoroughly, and incubated at room temperature for 10 min. The tube was centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 15 min at 4°C. After centrifugation, the mixture was separated into three phases. A 350-μl aliquot of the upper aqueous phase was transferred to a new tube and diluted with 150 μl of RNase-free distilled water. The RNA was then precipitated by adding 1 ml of isopropanol and incubated at room temperature for 10 min. The tube was centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 15 min at 4°C. The RNA pellet was washed once in 1 ml of cold 75% ethanol and centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 5 min. The RNA pellet was dried at room temperature. The pellet was resuspended in 30 μl of the RNase-free distilled water and treated with DNase I (DNA-free; Ambion Inc). The RNA concentration was quantified by using a spectrophotometer, and samples were electrophoresed in a formaldehyde agarose gel to confirm the quantity and quality of RNA. RNA was considered suitable for microarray analysis if the A260/A280 ratio was greater than 1.8.

Labeling of the samples.

Equal amounts of total RNA (3 to 10 μg) from two RNA samples (under different growth conditions) were mixed separately with an equal amount of the random hexamer, pd(N)6 (Amersham Bioscience), and the total volume was adjusted to 15 μl with RNase-free distilled water. The mixture was incubated at 70°C for 10 min and was maintained on ice. The cDNA was generated in a reverse transcription reaction using 100 U of StrataScript reverse transcriptase, 2 μl of 10× StrataScript reaction buffer, 1 μl of 20× deoxynucleoside triphosphate mix with an amino allyl dUTP, 1.5 μl of 0.1 M dithiothreitol, and 0.5 μl of a 40-U/μl solution of RNase block (Stratagene Inc.). The reaction mixture was incubated at 48°C for 1.5 h. The amino allyl-labeled cDNA was treated with 10 μl of 1 M NaOH and incubated at 70°C for 10 min to hydrolyze the RNA strand. A 10-μl aliquot of 1 M HCl and 4 μl of 3 M sodium acetate (pH 4.5) were added to the mixture to equilibrate the pH. The cDNA was precipitated by adding 1 μl of a 20-mg/ml solution of glycogen and 100 μl of cold 95% ethanol and incubating at −20°C overnight. The tube was centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 15 min at 4°C. The supernatant was carefully removed, and the cDNA pellet was washed once in 0.5 ml of cold 70% ethanol followed by centrifugation for 5 min at 4°C. The supernatant was carefully removed, and the pellet was left to dry at room temperature. The cDNA was resuspended in 5 μl of 2× coupling buffer (Stratagene Inc.) and incubated at 37°C for 10 min. The two cDNA samples were labeled separately with 5 μl of either Cy3 or Cy5 (CyTM3 and CyTM5 monofunctional dyes; Amersham Bioscience) and incubated in the dark at room temperature for 30 min before further purification. The uncoupled dye was removed from the fluorescent dye-labeled cDNA by using a microspin cup and DNA binding solution (Stratagene Inc.). The eluate from the microspin cup (50 μl) was reduced to approximately 3 μl by vacuum centrifugation.

Hybridization.

Each of the Cy3- and Cy5-labeled cDNA samples was diluted with 9 μl of DIG Easy Hyp solution (Roche Inc.) containing 5% (vol/vol) each of yeast tRNA and salmon sperm DNA as the blocking agents. Both hybridization solutions were combined and mixed carefully by pipetting and then heated at 95°C for 3 min. The hybridization solution was left to cool at room temperature and mixed thoroughly by centrifugation.

The hybridization was performed with 35-mer oligo microarray slides. The slides contained 200 genes, and each gene had four replicated spots. A whole-genome B. mallei open reading frame array was also used for microarray analysis. To use the array for B. pseudomallei samples, we compared the amplicon sequences representing the 5,244 genes in the array to the identified open reading frames in the B. pseudomallei genome using Blastn (WU-BLAST; Washington University). We selected a total of 4,375 sequences that matched at over 90% identity (average, ∼99%) to a single B. pseudomallei gene over its full length. Only the data from the microarray spots of these amplicons were used for this study.

The hybridization solution was applied onto the microarray and covered with a plastic coverslip (Hybri-Slips; Sigma Corp.). The slide was incubated at 42°C in a slide hybridization chamber (Boekel Scientific) for 18 h. Following incubation, the slide was washed with three solutions: solution 1, 2× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate) and 0.2% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) for 4 min; solution 2, 0.2× SSC for 1 min; solution 3, 0.1× SSC for 1 min at room temperature. The slide was spin dried in a centrifuge at 550 rpm for 5 min and scanned immediately.

Scanning and data analysis.

Scanning of the 200-gene oligonucleotide microarray hybridized slides was performed with a Virtek chip reader (Virtek Biotech Canada Inc.). The fluorescence signals were quantified using the QuantArray microarray analysis software (Packard Bioscience). Normalization and data analysis were performed with the GeneTraffic software (Iobion Informatics).

The whole-genome hybridized slides were scanned using the Axon GenePix 4000B microarray scanner, and the independent TIFF images from each channel were analyzed using TIGR Spotfinder (The Institute for Genomic Research [TIGR], Rockville, Md. [http://www.tigr.org/software/]) to obtain relative expression levels. Data from TIGR Spotfinder (28) were stored in AGED, a relational database designed to effectively capture and store microarray data.

Data were normalized using LOWESS local regression implemented in the MIDAS (28) software tool (TIGR [http://www.tigr.org/software/]). All calculated gene expression ratios were log2 transformed and averaged over dye-swapped arrays and again averaged over the biological replicate sets. Differentially expressed genes at the 95% confidence level were determined using intensity-dependent Z-scores (with Z = 1.96) as implemented in MIDAS.

Northern blot analysis.

Equal amounts (between 3 and 10 μg) of total RNA from different growth conditions used in the microarray studies were denatured at 95°C and electrophoresed onto a 1.2% formaldehyde agarose gel in 1× MOPS buffer (0.4 M morpholinopropanesulfonic acid, 0.1 M sodium acetate, 10 mM EDTA; pH 7.2) at 100 V for 45 min. RNA was transferred to GeneScreen hybridization membranes (NEN Life Science Products) using a vacuum blotter (Bio-Rad) as per the manufacturer's instructions. Following transfer, the membrane was baked at 80°C for 2 h.

Seven DNA probes (two genes of the type III secretion system [TTSS], bsaN and bsaP; the araC gene of the arabinose operon; and four selected genes, bpss0766, bpss0769, bpss0780, and bpss0782) located in the flanking regions of the inserted arabinose operon were obtained by PCR amplification of the following primers: bsaN primers, 5′-CGCGATGTCCCATGCCGTTT-3′ and 5′-GACGCGAAGCCGTTGCTCAT-3′; bsaP primers, 5′-TGCGCGATTTCATCCGGCAG-3′ and 5′-CCACAGCGACAGCTCGATCT-3′; araC primers, 5′-TGCGACCTCGACTTC-3′ and 5′-TCGTCAGTGCGTCCT-3′; bpss0766 primers, 5′-GCGTGAGGGCTTTCTCGAA-3′ and 5′-CTGCTCCATGTGATCGCGAT-3′; bpss0769 primers, 5′-TTCCCGACGAAACGATTCCG-3′ and 5′-ATCGGATCGTCGAACGCATG-3′; bpss0780 primers, 5′-TCGACAGACGGATGCTGATC-3′ and 5′-ACGATTCCTCGCGATAGAGC-3′; bpss0782 primers, 5′-TCGAGTTTCGCGATGCTCGT-3′ and 5′-AGCGCATAGAGCACCGATTG-3′. All PCR products were purified with QIAquick Spin (QIAGEN). For 32P labeling, 1 μg of DNA was denatured by heating for 3 min at 95 to 100°C and immediately placed on ice for 2 min before mixing with 50 μCi of [α-32P]dCTP (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). The mixture was incubated at 37°C for 40 min. The probe was heated to 95 to 100°C and immediately placed on ice before adding to the hybridization solution.

Membranes blotted with RNA were soaked in 2× SSC for 1 min before prehybridizing in the hybridization buffer (1% SDS, 10% [wt/vol] dextran sulfate) for 1 h at 65°C. The denatured DNA probe solution was added to the hybridization buffer. Hybridization was performed for 16 h at 65°C with rotation in a hybridization oven (Robbins Scientific Inc.). Following hybridization, the membrane was washed twice with an excess amount of 2× SSC for 5 min at room temperature, three times in a mixture of 2× SSC and 1% SDS at 60°C for 15 to 30 min, and three times with 0.1× SSC at room temperature. After the final wash, the damp membrane was wrapped securely in plastic wrap and exposed to X-ray film for 1 to 3 h.

RESULTS

Tn5-OT182 mutagenesis and isolation of an l-arabinose utilization mutant.

To identify genes involved in arabinose utilization, B. thailandensis E264 was mutagenized with Tn5-OT182, and mutants unable to grow using l-arabinose as a sole carbon source were identified. One mutant, RM600, was isolated and studied further. DNA flanking the transposon insertion in RM600 was isolated via self-cloning and sequenced. BLAST analysis revealed that the transposon integration was located in a gene with strong homology to α-KSAD from several bacterial species. The enzyme expressed from this gene is part of an l-arabinose assimilation pathway found in a variety of soil bacteria, including Herbaspirillum seropedicae (21), Rhizobium spp. (15), Azospirillum brasiliense (25), and Pseudomonas saccharophilia (33).

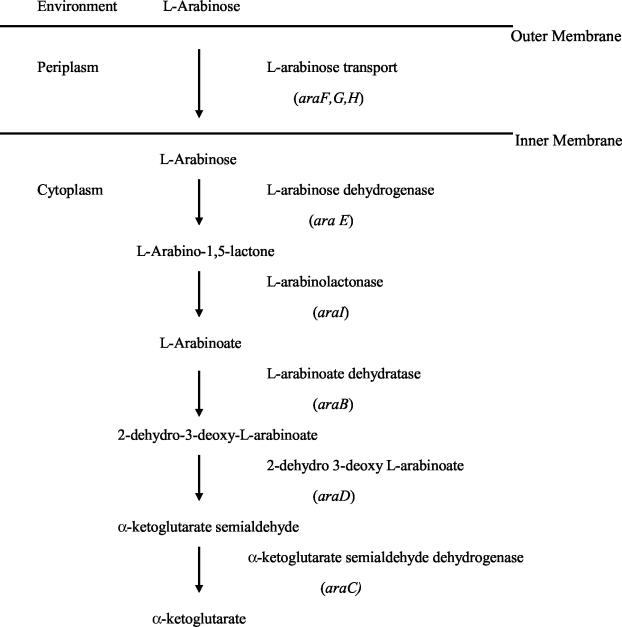

Identification of the arabinose assimilation operon in B. thailandensis.

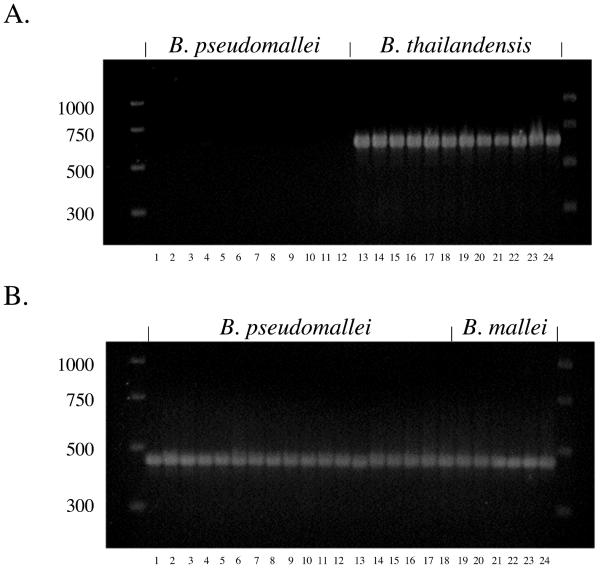

We identified a total of nine genes which are likely to be involved in l-arabinose metabolism and suggest a probable assimilation pathway (Fig. 1) based on known l-arabinose assimilation pathways in other bacteria (15, 21, 25, 33). pGSV3 or pGSV3-lux knockout mutants were constructed in the B. thailandensis DW503 l-arabinose assimilation genes, araA, araC, araI, and araE. None of these mutants was able to grow on M9-arabinose agar (Table 2). The inability of RM604 (araA mutant) to grow on l-arabinose suggests that the regulatory protein encoded by this gene acts as a positive regulator for the arabinose assimilation operon. In silico analysis of the genomes of B. pseudomallei K96243 (http://www.sanger.ac.uk/) and B. mallei ATCC 23344 (http://www.tigr.org/) did not reveal an intact arabinose assimilation operon. However, both contained DNA flanking the arabinose assimilation operon, suggesting that a deletion occurred which removed araA-araH from these genomes. The l-arabinose assimilation operon in B. thailandensis and the corresponding deleted regions in B. pseudomallei and B. mallei are shown schematically in Fig. 2.

FIG. 1.

Arabinose assimilation pathway in B. thailandensis.

TABLE 2.

Growth of B. thailandensis on M9 agar plates supplemented with 0.4% d-glucose or 0.4% l-arabinose as sole carbon sources

| B. thailandensis strain | Growth on carbon source

|

|

|---|---|---|

| d-Glucose | l-Arabinose | |

| E264 (wild type) | + | + |

| DW503 | + | + |

| RM600 (DW503 derivative; araC::Tn-5OT182 Ara− Tcr) | + | − |

| RM601 (DW503 derivative; araC::pGSV3-lux Gmr) | + | − |

| RM602 (DW503 derivative; araE::pGSV3-lux Gmr) | + | − |

| RM603 (DW503 derivative; araI::pGSV3 Gmr) | + | − |

| RM604 (DW503 derivative; araA::pGSV3 Gmr) | + | − |

FIG. 2.

Arrangement of arabinose assimilation genes on chromosome 2 (Chr2) in B. thailandensis (Bt). The corresponding regions on B. pseudomallei (Bp) Chr2 and B. mallei (Bm) Chr2 are also shown, including the location of the araA-araH deletion. The percent amino acid (AA) identity was determined using tBlastn, and the results are color coded. The figure also depicts the duplication and movement of araF, araG, and araH to chromosome 1 in both B. pseudomallei and B. mallei. The gene order is conserved, but the identity has decayed to lower than 60%. The exact chromosomal locations of all genes are shown in parentheses.

The B. pseudomallei and B. mallei araA remnants (5′ truncated) have several frameshift mutations relative to B. thailandensis araA. Likewise, the araH remnants (5′ truncated) have frameshift mutations in both B. pseudomallei and B. mallei relative to B. thailandensis araH. Interestingly, araF, araG, and araH have duplicated and moved from chromosome 2 to chromosome 1 in both B. pseudomallei and B. mallei (Fig. 2). The gene order is conserved, but the amino acid identity of the encoded proteins has dropped to lower than 60%. The similarity of the araFGH genes on chromosome 1 of B. pseudomallei and B. mallei suggests that this duplication occurred before B. mallei diverged from B. pseudomallei.

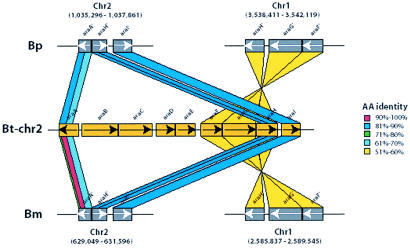

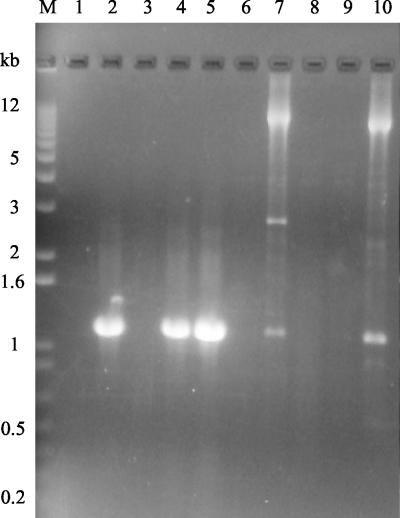

PCR survey for the presence of ara genes in B. pseudomallei and B. thailandensis isolates.

PCR primers ARA1 and ARA2 were designed to amplify a 638-bp product spanning the araA-araB intergenic region of the arabinose utilization locus. Twelve B. thailandensis strains yielded a PCR product of the correct size when tested with this primer pair (Fig. 3A, lanes 13 to 24). On the other hand, no B. pseudomallei strains yielded a positive PCR result with ARA1 and ARA2 (Fig. 3A, lanes 1 to 12). Thus, there is a correlation with the presence of the araA-araI genes and the ability to assimilate arabinose in these species. The ARA1 and ARA2 primer pair may be useful for differentiating B. pseudomallei and B. thailandensis in future studies.

FIG. 3.

PCR amplification of ara genes. (A) PCR survey for the presence of ara genes in B. pseudomallei and B. thailandensis isolates. PCR primers ARA1 and ARA2 were used to amplify a 638-bp product spanning the araA-araB intergenic region of the arabinose utilization locus. Lanes: 1, K96243; 2, 1026b; 3, 576; 4, E8; 5, E12; 6, E13; 7, 112c; 8, 238; 9, 295; 10, 296; 11, 713; 12, 730; 13, E27; 14, E30; 15, E32; 16, E96; 17, E100; 18, E105; 19, E111; 20, E120; 21, E125; 22, E132; 23, E135; 24, E264. (B) All B. pseudomallei and B. mallei strains examined contained the Δ(araA-araH) mutation. The PCR primer pair ARA1 and ARA3 was used to amplify a 454-bp product flanking the Δ(araA-araH) mutation in B. pseudomallei and B. mallei strains. Lanes: 1, K96243; 2, 1026b; 3, 576; 4, E8; 5, E12; 6, E13; 7, 112c; 8, 238; 9, 295; 10, 296; 11, 713; 12, 730; 13, 423; 14, 439a; 15, 465a; 16, 487; 17, 503; 18, 644; 19, NCTC 10248; 20, NCTC 10229; 21, NCTC 10260; 22, NCTC 10247; 23, ATCC 23344; 24, NCTC 120.

All B. pseudomallei and B. mallei strains examined contained the Δ(araA-araH) mutation.

The PCR primer pair ARA1 and ARA3 was designed to amplify a 454-bp product flanking the deletion termini of the arabinose utilization genes of B. pseudomallei K96243 and B. mallei ATCC 23344. Eighteen clinical and environmental B. pseudomallei isolates from Australia and Thailand yielded PCR products of the predicted size with this primer pair (Fig. 3B, lanes 1 to 18). Furthermore, six B. mallei strains also yielded a positive PCR result with the ARA1 and ARA3 primer pair (Fig. 3B, lanes 19 to 24). The nucleotide sequences of all of the PCR products were determined, and all contained the same deletion termini that are present in B. pseudomallei K96243 and B. mallei ATCC 23344. The fact that geographically diverse strains all contain the same Δ(araA-araH) mutation suggests that the loss of arabinose assimilation genes occurred early in the evolution of B. pseudomallei. Since B. mallei is a host-adapted clone of B. pseudomallei, it is not surprising that it also harbors this deletion. Although not shown, B. pseudomallei 406e gave identical results as those obtained for all other B. pseudomallei strains tested.

Induction of genes involved in arabinose metabolism.

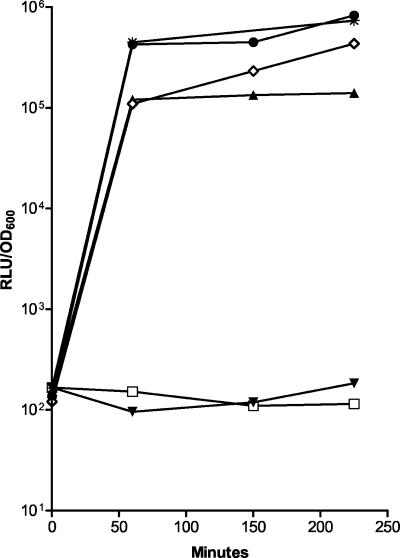

The expression levels of arabinose dehydrogenase and α-KSAD were examined using the pGSV3-lux knockout mutants B. thailandensis RM601 and B. thailandensis RM602. Growing cultures of each mutant received either arabinose, glucose, or both, and induction of arabinose utilization genes was followed via lux-mediated light production. The results of these experiments are shown in Fig. 4 and demonstrate that both arabinose dehydrogenase and α-KSAD were rapidly induced by the addition of arabinose or arabinose in the presence of glucose, but not by glucose alone.

FIG. 4.

Induction of arabinose assimilation genes in B. thailandensis RM601 (DW503 derivative; araC::pGSV3-lux Gmr)and RM602 (DW503 derivative; araE::pGSV3-lux Gmr). ▾, RM601 in glucose; □, RM602 in glucose; ⋄, RM601 in arabinose; ★, RM602 in arabinose; ▴, RM601 in glucose plus arabinose; •, RM602 in glucose plus arabinose. RLU, relative light units (luminescence).

The arabinose assimilation operon is present in the chromosome of B. pseudomallei SZ5028.

An l-arabinose-utilizing B. pseudomallei strain, SZ5028, was constructed as outlined in Fig. 5. Two PCR experiments were performed to confirm the integration of pDD5026H and the presence of the arabinose assimilation operon in the chromosome of B. pseudomallei SZ5028. In the first set of reactions, the ARA6 and ARA2 primers were used in an attempt to amplify the 1,136-bp araA gene from B. pseudomallei 1026b, 406e, SZ5026, and SZ5028 and B. thailandensis E264. In the second set of reactions, the ARA-F and ARA-R2 primers were used in an attempt to amplify the entire arabinose assimilation operon from these strains. The araA gene was amplified only from B. pseudomallei SZ5026 and SZ5028 and B. thailandensis E264, as indicated by a band corresponding to the predicted size of 1,136 bp (Fig. 6). As expected, the araA gene could not be amplified from wild-type B. pseudomallei strains 1026b or 406e due to the deletion of the arabinose assimilation operon, including part of this gene, from the chromosome (Fig. 2). The presence of the entire araA gene in B. pseudomallei SZ5026 and SZ5028 confirms the integration of pDD157 into the chromosome of SZ5026 and the integration of pDD5026H into the chromosome of SZ5028. Using the primers ARA-F and ARA-R2, the arabinose assimilation operon was successfully amplified from the positive control B. thailandensis E264 as well as from B. pseudomallei SZ5028. The presence of an approximately 11-kb band on the gel corresponding to the expected 11,789-bp PCR product indicated that the arabinose assimilation operon is present in SZ5028 (Fig. 6). There was no amplification of the arabinose assimilation operon from wild-type B. pseudomallei 406e or 1026b, nor could the operon be amplified from B. pseudomallei SZ5026, which only contains the araA gene inserted into the chromosome (Fig. 6).

FIG. 6.

PCR amplification of the araA gene and the arabinose assimilation operon from B. thailandensis and B. pseudomallei chromosomal DNA. Lanes 1 to 5, PCR amplification of the araA gene using primers ARA6 and ARA2. Lanes 6 to 10, PCR amplification of the arabinose assimilation operon using primers ARA-F and ARA-R2. Lane M, 1-kb Plus DNA ladder (Invitrogen Life Technologies); lanes 1 and 6, B. pseudomallei 1026b; lanes 2 and 7, B. thailandensis E264; lanes 3 and 8, B. pseudomallei 406e; lanes 4 and 9, B. pseudomallei SZ5026; lanes 5 and 10, B. pseudomallei SZ5028.

Amplification of the arabinose assimilation operon also produced two nonspecific PCR products from E264 and SZ5028 DNA, indicated by a 2,700-bp band and a 1,000-bp band in the E264 sample and a 1,000-bp band in the SZ5028 sample (Fig. 5). The sequence identity of these PCR products is unknown, but these bands were consistently present in previous PCR amplifications of the arabinose assimilation operon from B. thailandensis.

Utilization of l-arabinose by B. pseudomallei SZ5028.

B. pseudomallei 406e, SZ5026, and SZ5028 and B. thailandensis E264 were grown in M9 medium containing 0.4% l-arabinose as the sole carbon source or on M9 plus 0.4% arabinose plates. After 24 and 48 h of growth with shaking, the absorbance values (OD600) of the M9 plus 0.4% arabinose cultures were determined. Growth on arabinose plates was determined following incubation of the plates at 37°C for 48 h. As expected, B. pseudomallei 406e was not able to utilize arabinose. The OD600 values for this strain cultured in M9 plus 0.4% arabinose were 0.016 at 24 h and 0.030 at 48 h, and there was no detectable growth of this strain when grown on M9 plus 0.4% arabinose agar plates. The positive control, B. thailandensis E264, grew on the M9 plus 0.4% arabinose agar plates and in the M9 plus 0.4% arabinose medium, demonstrating OD600 values of 0.289 at 24 h and 1.374 at 48 h. The strain resulting from the integration of pDD5026H into the 406e chromosome, SZ5028, was found to utilize arabinose at a level comparable to that of B. thailandensis E264. The OD600 values for SZ5028 grown in M9 plus 0.4% arabinose medium were 0.528 at 24 h and 0.901 at 48 h. In addition, SZ5028 was able to grow on M9 plus 0.4% l-arabinose agar plates, confirming that this strain was capable of arabinose assimilation. The growth of B. pseudomallei SZ5026, the vector control strain, was greater in M9 plus 0.4% arabinose medium compared to growth of 406e, but the growth did not increase between 24 and 48 h compared to that of SZ5028 and E264, the arabinose-assimilating strains. In addition, SZ5026 did not grow on the M9 plus 0.4% l-arabinose agar.

B. pseudomallei SZ5028 is attenuated for virulence in the Syrian hamster model of melioidosis.

B. pseudomallei 406e, SZ5026, and SZ5028 and B. thailandensis E264 were grown in the presence of LB and LB plus 0.4% l-arabinose and tested for virulence in the Syrian hamster model of melioidosis. The LD50 for SZ5028 after 48 h was 198 CFU when grown in the presence of LB and 94 CFU when grown in LB plus 0.4% l-arabinose medium, compared to LD50 values with 406e and SZ5026 of <10 CFU when grown in either medium, representing an approximately 25- to 50-fold decrease in virulence (Table 3). In these experiments, B. thailandensis E264 had an LD50 value of >1,000, although the actual LD50 value for this strain was previously calculated to be 1.8 × 106 CFU (7). Although SZ5028 was more virulent than B. thailandensis E264, it was attenuated for virulence compared to wild-type B. pseudomallei 406e. This suggests that the presence of the arabinose assimilation operon in B. pseudomallei may affect the expression of virulence genes, contributing to decreased virulence of the organism. The difference in virulence between 406e and SZ5028 cannot be attributed to differences in growth rates, since the growth curves of 406e, SZ5026, and SZ5028 were found to be similar (data not shown). When the mutant strain B. thailandensis RM600 (able to grow on LB and M9-glucose but not on M9-arabinose) was tested for virulence in the hamster model, it was found not to be significantly altered in its virulence properties relative to E264 (data not shown).

TABLE 3.

Virulence of arabinose-utilizing B. pseudomallei strain SZ5028 in the Syrian hamster model of infection

| Strain | Growth medium | LD50 (CFU) |

|---|---|---|

| B. pseudomallei 406e | LB | <10 |

| LB + 0.4% arabinose | <10 | |

| B. thailandensis E264 | LB | >1,000 |

| LB + 0.4% arabinose | >1,000 | |

| B. pseudomallei SZ5026 | LB | <10 |

| LB + 0.4% arabinose | <10 | |

| B. pseudomallei SZ5028 | LB | 198 |

| LB + 0.4% arabinose | 94 |

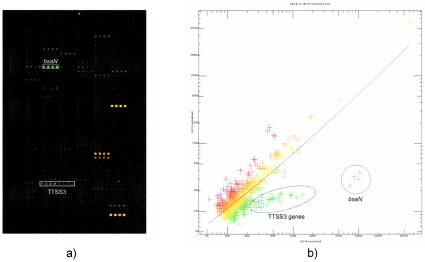

Growth on l-arabinose down-regulates type III secretion genes in B. pseudomallei SZ5028.

Microarray analysis of gene regulation in B. pseudomallei SZ5028 grown in the presence of arabinose or glucose using 200-gene microarrays demonstrated that a number of genes involved in one of the TTSSs were down-regulated during growth in M9 plus 1.0% arabinose compared to growth in M9 plus 1.0% glucose (Fig. 7). Of the total of 200 genes examined, 4 genes showed decreased expression. All four genes belonged to a TTSS (TTSS3) homologous with the Salmonella SPI-1 pathogenicity island (3), with the greatest difference (7.7-fold) being noted for a gene encoding an AraC-like transcriptional regulator (28) (Table 4). The putative regulator is a homologue of the TTSS positive regulator InvF in Salmonella, MxiE in Shigella, and VirF in Yersinia and was recently named bsaN (32). Furthermore, other TTSS genes encoding structural proteins were significantly down-regulated (2.0- to 3.1-fold) (Table 4), although they were not reduced to the same extent as the bsaN regulator gene. This result suggests that bsaN is a positive transcriptional regulator of the B. pseudomallei TTSS3 cluster whose activity is decreased directly or indirectly by the presence of arabinose or the absence of glucose.

FIG. 7.

Gene expression profiles of the arabinose-assimilating B. pseudomallei strain SZ5028 grown in M9 medium containing 1% arabinose versus that with 1% glucose. (a) Microarray image showing up-regulated (red) and down-regulated (green) genes. (b) Scatter plot of the normalized data, showing genes involved in TTSS3 that were significantly down-regulated. LEX.R, intensities of the reference sample (cells grown in 1% glucose); LEX.E, intensities of the evaluated sample (cells grown in 1% arabinose). The plotted data were normalized using the LOWESS smoothing (subgrid) method based on the GeneTraffic software, and the regression line shows the 1:1 ratio of 100% LOWESS smoothing factor.

TABLE 4.

Comparative expression of B. pseudomallei strain SZ5028 type III secretion genes in response to growth in M9 media containing 1.0% l-arabinose or d-glucose from analysis of 200-gene microarrays

| Gene | Putative function | Mean log2(IAra/IGlu) ± SD |

|---|---|---|

| bsaN | Possible TTSS transcriptional regulator, similar to the AraC family regulatory protein | −2.94 ± 1.30 |

| bsaP | TTSS secreted protein similar to mxiC gene in Shigella spp. | −1.61 ± 0.91 |

| bsaM | Similar to prgH gene in Chromobacteria violaceum; TTSS inner membrane protein | −1.02 ± 0.65 |

| bprA | Possible TTSS transcriptional regulator, similar to the H-NS DNA binding protein | −1.29 ± 0.49 |

Mean log2(IAra/IGlu) = average value of the log2-based ratio of intensities from two channels of the microarray: growth in arabinose versus growth in glucose. A negative number denotes down- regulation in arabinose. Only genes which displayed at least a twofold decrease [log2(IAra/IGlu) ≤ −1] in expression are listed. Results are the average of two independent RNA isolations with reverse labeling of each sample (dye swap), resulting in a total of four analyses.

Interestingly, results from analysis of the whole-genome microarrays were similar to those obtained from the 200-gene microarrays. Of a total of 4,375 genes examined using the whole-genome arrays, 211 genes showed differentiated expression. We found that 24 out of the 32 linked genes located in chromosome 2 (coordinates from 2073665 to 2105918) were significantly down-regulated, with 95% confidence, in M9 plus 1.0% arabinose compared to M9 plus 1.0% glucose (Table 5), and as seen with the results from the 200-gene microarray experiments, these are homologous with TTSS genes. It was, however, interesting that a significant number of putative TTSS genes were newly identified from this analysis. In particular, the genes corresponding to footnote a in Table 5 are located outside of the projected boundaries for the B. pseudomallei and B. mallei type III secretion operons. Further, two of the coordinately regulated TTSS genes are annotated as putative exported proteins and may be genes coding for the secreted effector molecules of this TTSS.

TABLE 5.

Comparative expression of B. pseudomallei strain SZ5028 genes in response to growth in M9 media containing 1.0% l-arabinose or d-glucose from analysis of whole-genome microarrays

| Mean log2(IAra/IGlu)d | Gene | Common name | Other name |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3.660567716 | BPSL2188 | Isocitrate lyase | |

| 2.872528528 | BPSS1799 | Conserved hypothetical protein | |

| 2.396046588 | BPSL0638 | Putative membrane protein | |

| 2.30341532 | BPSS1802 | Putative membrane protein | |

| 2.214457543 | BPSL0688 | Putative glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase | |

| 2.166956925 | BPSS0772 | MarR family regulatory protein | |

| 2.134310112 | BPSL0687 | Putative glycerol kinase | |

| 1.892752921 | BPSS1801 | Hypothetical transposon protein | |

| 1.876541084 | BPSS1800 | Putative dehydrogenase | |

| 1.82906867 | BPSS1575 | α-Ketoglutarate-dependent taurine dioxygenase | |

| 1.709388586 | BPSS1485b | Conserved hypothetical protein | |

| 1.704217668 | BPSS0310 | Hypothetical protein | |

| 1.604675546 | BPSL3396 | ATP synthase beta chain | |

| 1.492801878 | BPSS0190 | Putative O-acetylhomoserine phosphate transport system, substrate binding exported | |

| 1.491778582 | BPSL1359 | Periplasmic protein | |

| 1.485378831 | BPSS0153 | Glutamate-aspartate periplasmic binding protein | |

| 1.479761295 | BPSS1571 | Probable NADH oxidoreductase | |

| 1.447509585 | BPSS1553a | Putative membrane protein | |

| 1.41337407 | BPSS1415 | Putative dehydrogenase-oxidoreductase protein | |

| 1.334014629 | BPSS1417 | Putative l-fuculose phosphate aldolase | |

| 1.284925131 | BPSS0973 | Mg2+ transport ATPase, P-type 2 | |

| 1.277778343 | BPSL2336 | Putative glutamine synthetase | |

| 1.274610271 | BPSS0031 | Putative anaerobic growth regulatory protein | |

| 1.256584401 | BPSS0257 | Putative ribose ABC transport system, substrate binding exported protein | |

| 1.255907584 | BPSL3401 | ATP synthase c chain | |

| 1.177272863 | BPSL2500 | Electron transfer flavoprotein beta-subunit | |

| 1.157434208 | BPSS0260 | Putative kinase | |

| 1.131859522 | BPSS0885 | N-Acylhomoserine lactone synthesis protein | |

| 1.084088768 | BPSS1572 | Permease component of taurine ABC transporter | |

| 1.072310657 | BPSL1363 | Phosphate transport system-related protein | |

| 1.065265887 | BPSL1362 | Phosphate transport system ATP-binding protein | |

| 1.053551864 | BPSS0519 | Conserved hypothetical protein | |

| 1.051120355 | BPSS0524 | Conserved hypothetical protein | |

| 1.049706097 | BPSS0771 | Hypothetical protein | |

| 1.038876362 | BPSS0977 | Putative cytochrome c subunit II | |

| 1.012236689 | BPSS0316 | Putative ACB transport system, membrane protein | |

| 0.993355473 | BPSL2611 | Maltose-binding protein | |

| 0.975444214 | BPSL2925 | Glutamate dehydrogenase | |

| 0.973999816 | BPSL1489 | Putative membrane protein | |

| 0.947238343 | BPSL2068 | Putative two-component system, response regulator | |

| 0.939612293 | BPSS0259 | Putative dehydrogenase | |

| 0.928566139 | BPSS0329 | Putative fatty aldehyde dehydrogenase | |

| 0.909462198 | BPSS0528 | Conserved hypothetical protein | |

| 0.905799795 | BPSS1638 | Putative hydratase | |

| 0.898099586 | BPSL3104 | Conserved hypothetical protein | |

| 0.888963775 | BPSL3399 | ATP synthase delta chain | |

| 0.88606119 | BPSS0034 | Putative fatty aldehyde dehydrogenase | |

| 0.875598331 | BPSL2970 | KDPG/KHG aldolase, putative | |

| 0.86945211 | BPSL2972 | Transcriptional regulator, IclR family | |

| 0.83562524 | BPSL2967 | l-arabinose ABC transporter, ATP-binding protein | |

| 0.810672159 | BPSL1364 | Phosphate regulon two-component system response regulator | |

| 0.80527425 | BPSL3416 | Putative branched-chain amino acid ABC transporter, periplasmic substrate binding protein | |

| 0.799179699 | BPSS0156 | Putative dehydrogenase | |

| 0.794669183 | BPSL1961 | Putative electron transport protein | |

| 0.777504798 | BPSS0265 | Putative porin-related exported protein | |

| 0.755403028 | BPSS1356 | Hypothetical protein | |

| 0.750869748 | BPSS0526 | Hypothetical protein | |

| 0.747026223 | BPSS0154 | d-Amino acid dehydrogenase small subunit | |

| 0.743456855 | BPSL2028 | Putative fimbriae assembly chaperone | |

| 0.73331917 | BPSL2177 | Hypothetical protein | |

| 0.711866447 | BPSL3021 | Cell division protein FtsA | |

| 0.695228684 | BPSL2024 | Putative two-component regulatory system, response regulator | |

| 0.668360942 | BPSS0308 | Putative aminotransferase | |

| 0.655842301 | BPSS1637 | 4-Hydroxybutyrate coenzyme A transferase | |

| 0.637379273 | BPSS0262 | Putative aminoglycoside 6′-N-acetyltransferase | |

| 0.628790939 | BPSS0303 | Putative diaminopimelate decarboxylase | |

| 0.625501197 | BPSS0307 | Putative aldehyde dehydrogenase | |

| 0.596306364 | BPSL2309 | Respiratory nitrate reductase alpha chain | |

| 0.590151581 | BPSL2066 | Putative exported protein | |

| 0.587354108 | BPSL0373 | Putative isocitrate dehydrogenase | |

| 0.583575109 | BPSL2189 | Conserved hypothetical protein | |

| 0.561185706 | BPSL1361 | Phosphate transport system permease protein | |

| 0.535335317 | BPSS1428 | Hypothetical protein | |

| 0.528600905 | BPSS0799 | Hypothetical protein | |

| 0.502223307 | BPSL0415 | Zinc-binding dehydrogenase (partial) | |

| 0.48860634 | BPSL1029 | Putative exported outer membrane porin protein | |

| 0.451071772 | BPSL1345 | Putative exported transglycosylase protein | |

| 0.447920038 | BPSS1911 | Putative membrane protein | |

| 0.43439967 | BPSL1876 | Putative phospholipase | |

| 0.415997942 | BPSS0945 | Putative lipoprotein | |

| 0.414734465 | BPSS0880 | Putative transcription elongation factor | |

| 0.39974228 | BPSL2315 | Endonuclease/exonuclease/phosphatase family | |

| 0.392807392 | BPSL1278 | Putative ABC transport system, iron-binding exported protein | |

| 0.386719733 | BPSL2027 | Putative fimbriae-related protein | |

| 0.37758332 | BPSS0974 | Subtilase family protease | |

| 0.376154287 | BPSL0812 | TetR family regulatory protein | |

| 0.372701224 | BPSL2840 | Putative flavohemoglobin like protein | |

| 0.369640959 | BPSS0944 | LysR family regulatory protein | |

| 0.350896899 | BPSL1904 | Putative exported protein | |

| −0.265546681 | BPSL2397 | Hypothetical protein | |

| −0.375599667 | BPSL1062 | Translation initiation factor IF-1 | |

| −0.385629165 | BPSS0648 | AraC family regulatory protein | |

| −0.401476867 | BPSS2146 | Putative LysR family transcriptional regulator | |

| −0.410106054 | BPSL2368 | Putative membrane protein | |

| −0.418904592 | BPSL0600 | Hypothetical protein | |

| −0.42521041 | BPSL0474 | Putative transporter protein | |

| −0.461122926 | BPSS1508b | Hypothetical protein | |

| −0.470627995 | BPSL3368 | Putative AraC family transcriptional regulator | |

| −0.477031398 | BPSL0491 | Putative acyl carrier protein | |

| −0.489581077 | BPSL2946 | C4-dicarboxylate transport protein | |

| −0.500094955 | BPSS1867 | Putative membrane protein | |

| −0.508615787 | BPSL1762 | Precorrin-3b C17-methyltransferase | |

| −0.534798524 | BPSS1510b | Putative membrane protein | |

| −0.540333178 | BPSL1442 | Putative membrane protein | |

| −0.551488165 | BPSS1004 | Putative acyl transferase | |

| −0.578510311 | BPSS1240 | Putative penicillin-binding protein | |

| −0.591347751 | BPSL1191 | Putative exported protein | |

| −0.60912439 | BPSL0296 | Conserved hypothetical protein | |

| −0.623616771 | BPSS1754 | Putative membrane protein | |

| −0.62533172 | BPSS1535a | Surface presentation of antigens protein | bsaY |

| −0.626547891 | BPSL1174 | Two-component system, sensor kinase protein | |

| −0.634381721 | BPSL1170 | Putative membrane protein | |

| −0.659601302 | BPSS1614c | Putative type III secretion protein | bpscD2 |

| −0.661862496 | BPSS0227 | Putative membrane protein | |

| −0.666184002 | BPSS1744 | Putative cytochrome b561 | |

| −0.666845101 | BPSS1620c | Putative type III secretion protein | bpscV2 |

| −0.673719979 | BPSL2399 | Putative glycosyltransferase | |

| −0.679727251 | BPSS1811c | Conserved hypothetical protein | hrpV (TTSS2) |

| −0.682518126 | BPSL2034 | Putative hydrolase | |

| −0.684480069 | BPSL2540 | Putative inner membrane protein | |

| −0.688717244 | BPSL2213 | Conserved hypothetical protein (pseudogene) | |

| −0.692369046 | BPSS0008 | Putative TetR family regulatory protein | |

| −0.693886932 | BPSS1489b | Putative exported protein | |

| −0.730982339 | BPSS1509b | Conserved hypothetical protein | |

| −0.7331972 | BPSL2322 | Putative membrane protein | |

| −0.744510147 | BPSS1501b | Conserved hypothetical protein | |

| −0.766096437 | BPSL3310 | Flagellar regulon master regulator subunit FlhC | |

| −0.770676455 | BPSS1504b | Putative exported protein | |

| −0.772200497 | BPSL1173 | Potassium-transporting ATPase c chain | |

| −0.775876851 | BPSL2657 | Urease gamma subunit | |

| −0.783460065 | BPSS2091 | Hypothetical protein | |

| −0.796888021 | BPSS1117 | Conserved hypothetical protein | |

| −0.810417894 | BPSS1613c | Putative type III secretion protein | bpscE2 |

| −0.826702179 | BPSL0192 | NADP-dependent alcohol dehydrogenase | |

| −0.828794009 | BPSS1728 | Putative hemolysin activator | |

| −0.852588312 | BPSS0692 | Fumarylacetoacetate hydrolase family | |

| −0.856506201 | BPSL1591 | Conserved hypothetical protein | |

| −0.881132891 | BPSS1118 | Putative HlyD family protein | |

| −0.888650117 | BPSL1185 | Putative membrane protein | |

| −0.925094352 | BPSL2111 | Putative LysR-family transcriptional regulator | |

| −0.937413375 | BPSL2035 | Putative regulatory protein | |

| −0.960146058 | BPSS1496b | Conserved hypothetical protein | |

| −0.984330728 | BPSS1550a | TTSS protein | bsaJ |

| −0.986561024 | BPSS1507b | Hypothetical protein | |

| −0.996980632 | BPSS0966 | Putative manganese transport protein | |

| −1.003770427 | BPSS1500b | Conserved hypothetical protein | |

| −1.004140376 | BPSS1497b | Conserved hypothetical protein | |

| −1.006872551 | BPSS1896 | Ubiquinol oxidase polypeptide I | |

| −1.022502983 | BPSS1551a | TTSS protein | sctKBp3 |

| −1.023479736 | BPSS1782 | Organic hydroperoxide resistance protein | |

| −1.035169118 | BPSL1322 | Putative heat shock protein | |

| −1.036142443 | BPSL2301 | Pyruvate dehydrogenase E1 component | |

| −1.038757904 | BPSL3369 | Acetaldehyde dehydrogenase | |

| −1.045056203 | BPSL0494 | LysR family regulatory protein | |

| −1.056941766 | BPSL2929 | Thermoresistant gluconokinase | |

| −1.071013189 | BPSS1612c | Hypothetical protein | bpscF2 |

| −1.125942579 | BPSL2489 | 50S ribosomal protein L19 | |

| −1.12671761 | BPSS0752 | Putative lipoprotein | |

| −1.135350706 | BPSS2051 | Putative DNA-binding protein | |

| −1.164923297 | BPSL1172 | Potassium-transporting ATPase b chain | |

| −1.171472171 | BPSS1515b | Putative transposase (partial) | |

| −1.206749612 | BPSL1323 | Putative heat shock protein | |

| −1.242957236 | BPSS1119 | Putative RND efflux transporter | |

| −1.258189419 | BPSL2323 | Putative exported protein | |

| −1.296885852 | BPSL3427 | Putative two-component sensor kinase | |

| −1.357746981 | BPSS1363 | Putative exported protein | |

| −1.36533721 | BPSS0910 | Conserved hypothetical protein | |

| −1.42123191 | BPSS1534a | Surface presentation of antigens protein | bsaZ |

| −1.467766735 | BPSL1171 | Potassium-transporting ATPase a chain | |

| −1.467876647 | BPSL0024 | LrgA family protein | |

| −1.507840263 | BPSS1491b | Conserved hypothetical protein | |

| −1.558631442 | BPSS1503b | Hypothetical protein | |

| −1.638155545 | BPSS1514b | GTP cyclohydrolase I | |

| −1.653768643 | BPSS0289 | Putative exported protein | |

| −1.670203034 | BPSS1917 | Putative crp-family transcriptional regulator | |

| −1.702728184 | BPSS0965 | Putative oxalate decarboxylase | |

| −1.704025718 | BPSS1536a | Surface presentation of antigens protein | bsaX |

| −1.725537375 | BPSS1748 | Hypothetical protein | |

| −1.730257516 | BPSS1783 | Hypothetical protein | |

| −1.756482379 | BPSL0025 | Putative membrane protein | |

| −1.818503841 | BPSS1513b | Hypothetical protein | |

| −1.820198806 | BPSS1532d | Putative cell invasion protein | bapB |

| −1.842067577 | BPSS1541a | Surface presentation of antigens protein | bsaS |

| −1.917238884 | BPSS1519b | Transposase | |

| −2.04912008 | BPSS0514 | Acetyl coenzyme A hydrolase/transferase | |

| −2.08878765 | BPSS1520a | Putative AraC-family transcriptional regulator | bprC |

| −2.136822097 | BPSS1498b | Conserved hypothetical protein | |

| −2.147227432 | BPSS1537a | Surface presentation of antigens protein | bsaW |

| −2.147273814 | BPSS0756 | Putative exported protein | |

| −2.209090551 | BPSS1543a | TTSS protein | bsaQ |

| −2.412295713 | BPSS1549d | TTSS protein | bsaK |

| −2.447592658 | BPSS0753 | Hypothetical protein | |

| −2.500150544 | BPSS1542a | Surface presentation of antigens protein | bsaR |

| −2.772712922 | BPSS1526a | Putative invasion protein | bapC |

| −2.80293907 | BPSS1523a | Putative chaperone | bicP |

| −2.868102303 | BPSS1545a | TTSS protein | bsaO |

| −2.87670536 | BPSS1493a | Hypothetical protein | |

| −2.928005448 | BPSS0755 | LysR family regulatory protein | |

| −2.99669704 | BPSS1547a | TTSS protein | bsaM |

| −3.023822001 | BPSS1494b | Putative two-component response regulator | |

| −3.166688057 | BPSS1548a | TTSS protein | bsaL |

| −3.220777282 | BPSS1525a | Putative G-nucleotide exchange factor | bopE |

| −3.2758023 | BPSS1522a | Putative two-component response regulator | bprB |

| −3.330120749 | BPSS1546a | Putative AraC-family regulator of type III secretion system | bsaN |

| −3.42729804 | BPSS1524a | Putative intercellular spread protein | bopA |

| −4.034898051 | BPSS1521a | Hypothetical protein | |

| −4.307254378 | BPSS1530a | Putative HNS-like regulatory protein | bprA |

| −4.349596738 | BPSS1529a | Putative membrane antigen | bipD |

| −4.43240846 | BPSS1533a | Surface presentation of antigens protein | bicA |

| −5.391462205 | BPSS1516b | Hypothetical protein | |

| −5.818423748 | BPSS1517b | Hypothetical protein |

TTSS3 gene.

Putative TTSS3 additional gene.

TTSS gene.

Mean log2(IAra/IGlu) = average value of the log2-based ratio of intensities from two channels of the microarray: growth in arabinose versus growth in glucose.

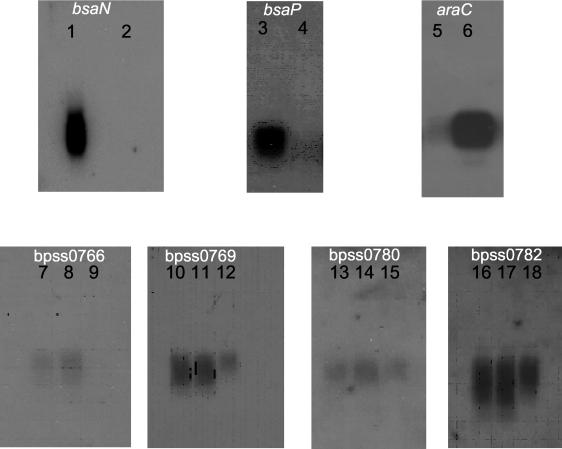

Northern blot analysis confirmed the microarray data.

Figure 8 represents the results from the Northern blot analyses of specific gene expression. These data confirmed the results from the microarray analyses in that specific type III secretion genes were repressed in B. pseudomallei strain SZ5028 when the organisms were grown in arabinose versus glucose. Additionally, the data indicate that strains B. pseudomallei 406e and SZ5028 are isogenic and that the difference in virulence between these strains was not due to effects from the integration of a plasmid which is >13 kb in size, as genes flanking the integration site were not altered in their expression.

FIG. 8.

Northern blot analysis of gene expression. Lanes 1, 3, 5, 8, 11, 14, and 17, total RNA from strain SZ5028 grown in M9 medium supplemented with 1% glucose; lanes 2, 4, 6, 9, 12, 15, and 18, total RNA from strain SZ5028 grown in M9 medium supplemented with 1% arabinose; lanes 7, 10, 13, and 16, total RNA from strain 406e grown in M9 medium supplemented with 1% glucose. The RNA blots were probed with the genes bsaN, bsaP, araC, bpss0766, bpss0769, bpss0780, and bpss0782.

DISCUSSION

Arabinose metabolism has historically been a primary means of distinguishing between virulent and avirulent strains of Burkholderia spp. isolated from the soils of northern Thailand. We now know that two closely related Burkholderia species reside in the soil and that the ability to metabolize arabinose distinguishes avirulent B. thailandensis from its virulent close relative, B. pseudomallei (31).

In this study we characterized arabinose metabolism in B. thailandensis and examined the role of the l-arabinose assimilation operon in the virulence of B. pseudomallei. We were able to generate a transposon mutant in B. thailandensis that was unable to utilize l-arabinose as a sole carbon source. Using this mutant, we identified an l-arabinose assimilation operon consisting of nine genes, including a transcriptional regulator. The presence of these genes suggested a metabolic pathway similar to that found in a variety of soil bacteria. Using lux-fusion constructs, we were able to demonstrate that the operon is inducible by l-arabinose but not by d-glucose. Although unable to utilize arabinose as a sole carbon source, sequence data have shown that the B. pseudomallei chromosome contains at least two regions of the arabinose assimilation operon found in B. thailandensis. These regions include a portion of araA, which encodes the arabinose assimilation operon regulator, and a portion of araH (involved in l-arabinose transport) and araI (l-arabinolactonase). These observations suggest that at one time, the B. pseudomallei chromosome contained an intact l-arabinose assimilation operon.

To examine what effect l-arabinose assimilation genes might have on the virulence of B. pseudomallei, we introduced the l-arabinose assimilation operon from B. thailandensis into B. pseudomallei 406e, generating the strain SZ5028. B. pseudomallei SZ5028 was able to grow in minimal medium containing l-arabinose as the sole carbon source. The presence of the l-arabinose assimilation operon in SZ5028 reduced virulence in this strain. Using the Syrian hamster model of B. pseudomallei infection, we found that SZ5028 had a significantly higher LD50 than did the parent strain, B. pseudomallei 406e (198 CFU versus <10 CFU), although SZ5028 remained much more virulent than B. thailandensis (LD50 = 1.8 × 106 CFU). A similar increase in LD50 values has also been observed in mutant strains of B. pseudomallei which were singly deficient in other virulence factors, including serum resistance (13), motility (14), or type III secretion (J. Warawa and D. E. Woods, submitted for publication). Given the detrimental effects of arabinose upon B. pseudomallei virulence, we found it interesting that the growth of B. pseudomallei with arabinose as the sole carbon source resulted in the down-regulation of genes of TTSS3—the Salmonella-like gene cluster required for virulence in hamsters. The microarray results have provided a direct link between the attenuation of virulence associated with arabinose utilization and down-regulation of TTSS3 functional activity. Further, our microarray data demonstrated that the transcription of the gene for a putative positive regulator of TTSS3, bsaN, was reduced during growth with arabinose. BsaN is predicted to be a member of the AraC family of transcriptional regulators, which appear to be common in mammalian-targeting TTSS clusters, such as VirF, PerA, ExsA, MxiE, and InvF in Yersinia, enteropathogenic E. coli, Pseudomonas, Shigella, and Salmonella, respectively. AraC, in E. coli, acts as either a positive or negative regulator and is encoded within the arabinose utilization operon, and its activity is affected by the direct binding of arabinose (for review, see reference 29). We hypothesize that arabinose directly binds the AraC homologue, BsaN, and thereby inactivates the positive transcriptional regulation of TTSS3 genes in B. pseudomallei. The studies to test this hypothesis are ongoing, and the results from these studies could have significant implications for a wide range of TTSSs in mammalian pathogens whereby arabinose may act as an inhibitor of TTSS-mediated pathogenesis.

The abundance of l-arabinose in the environment presumably provides B. thailandensis a means of easily acquiring necessary carbon as well as the ability to compete with other soil microorganisms. However, arabinose metabolism may have been detrimental to an organism shifting from a soil environment to the environment of an animal host, resulting in negative selection for arabinose metabolism genes. As such, l-arabinose assimilation genes may be classified as antivirulence genes, as put forth by Maurelli et al. (22). Loss of this function may have had little consequence in regard to survival in tropical soils, where a variety of other carbohydrates might be readily available, but this loss may have been critical for success as an animal pathogen. Loss of an antivirulence metabolic pathway combined with the acquisition of virulence genes, such as those responsible for capsule synthesis (26) and TTSSs, may have allowed B. pseudomallei a means of thriving in both soil and animal environments. It has been proposed that B. mallei evolved from B. pseudomallei (17) and, thus, it is likely that the advantages that loss of arabinose assimilation genes provided were shared with B. mallei as it adapted to the more restrictive environment presented to a host-adapted pathogen unable to persist outside of an equine host.

It was interesting that the ability of the B. thailandensis arabinose utilization locus to affect expression of virulence genes in B. pseudomallei and B. mallei using whole-genome DNA microarray analysis provided results similar to those obtained using significantly smaller 200-gene microarrays. Most certainly, small gene arrays have been used in other studies with different organisms and have yielded important and significant results (2, 18-20). In our studies, we have provided additional documentation for the utility of small gene arrays in the analysis of gene expression, and it is clear that intuitive selection of specific genes for the construction of small gene arrays can lead to important conclusions regarding gene expression under various environmental conditions.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the Department of Defense contract no. DAMD 17-03-C0062 and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (MOP-36343). D.E.W. is a Canada Research Chair in Microbiology.

We thank Marina Tom and Patricia Baker for excellent technical assistance throughout various stages of this work.

Editor: J. T. Barbieri

REFERENCES

- 1.Altshul, S. F., W. Gish, W. Miller, E. W. Meyers, and D. J. Lipman. 1990. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 215:403-410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Asai, K., H. Yamaguchi, C. Kang, K. Yoshida, Y. Fujita, and Y. Sodaie. 2003. DNA microarray analysis of Bacillus subtilis sigma factors of extracytoplasmic function family. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 220:155-160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Attree, O., and I. Attree. 2001. A second type III secretion system in Burkholderia pseudomallei: who is the real culprit? Microbiology 147:3197-3199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bjarnason, J., C. M. Southward, and M. G. Surette. 2003. Genomic profiling of iron-responsive genes in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium by high-throughput screening of a random promoter library. J. Bacteriol. 185:4973-4982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blatny, J. M., T. Brautaset, H. C. Winther-Larsen, K. Haugan, and S. Valla. 1997. Construction and use of a versatile set of broad-host-range cloning and expression vectors based on the RK2 replicon. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:370-379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boyer, H. W., and D. Roulland-Dussoix. 1969. A complementation analysis of the restriction and modification of DNA in Escherichia coli. J. Mol. Biol. 41:459-472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brett, P. J., D. DeShazer and D. E. Woods. 1997. Characterization of Burkholderia pseudomallei and Burkholderia pseudomallei-like strains. Epidemiol. Infect. 118:137-148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brett, P. J., D. DeShazer, and D. E. Woods. 1998. Burkholderia thailandensis sp. nov., a Burkholderia pseudomallei-like species. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 48:317-320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brett, P. J., M. N. Burtnick, and D. E. Woods. 2003. The wbiA locus is required for the 2-O-acetylation of lipopolysaccharides expressed by Burkholderia pseudomallei and Burkholderia thailandensis. FEMS Microbiol. 218:323-328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.DeShazer, D., D. M. Waag, D. L. Fritz, and D. E. Woods. 2001. Identification of a Burkholderia mallei polysaccharide gene cluster by subtractive hybridization and demonstration that the encoded capsule is an essential virulence determinant. Microb. Pathog. 30:253-269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.DeShazer, D., and D. E. Woods. 1999. Animal models of melioidosis, p. 199-203. In O. Zak and M. Sande (ed.), Handbook of animal models of infection. Academic Press, London, England.

- 12.DeShazer, D., and D. E. Woods. 1999. Pathogenesis of melioidosis: use of Tn5-OT182 to study the molecular basis of Burkholderia pseudomallei virulence. J. Infect. Dis. Antimicrob. Agents 16:91-96. [Google Scholar]

- 13.DeShazer, D., P. J. Brett, and D. E. Woods. 1998. The type II O-antigenic polysaccharide moiety of Burkholderia pseudomallei lipopolysaccharide is required for serum resistance and virulence. Mol. Microbiol. 30:1081-1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.DeShazer, D., P. J. Brett, R. Carlyon, and D. E. Woods. 1997. Mutagenesis of Burkholderia pseudomallei with Tn5-OT182: isolation of motility mutants and molecular characterization of the flagellin structural gene. J. Bacteriol. 179:2116-2125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Duncan, M. J. 1979. l-Arabinose metabolism in rhizobia. J. Gen. Microbiol. 113:177-179. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Figurski, D. H., and D. R. Helinski. 1979. Replication of an origin-containing derivative of plasmid RK2 dependent on a plasmid function provided in trans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 76:1648-1652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Godoy, D., G. Randle, A. J. Simpson, D. M. Aanensen, T. L. Pitt, R. Kinoshita, and B. G. Spratt. 2003. Multilocus sequence typing and evolutionary relationships among the causative agents of melioidosis and glanders, Burkholderia pseudomallei and Burkholderia mallei. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:2068-2079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hot, D., R. Antoine, G. Renauld-Mongenie, V. Caro, B. Hennuy, E. Levillain, L. Huot, G. Wittmann, D. Poncet, F. Jacob-Dubuisson, C. Guyard, F. Rimlinger, L. Aujame, E. Godfroid, N. Guiso, M. J. Quentin-Millet, Y. Lemoine, and C. Locht. 2003. Differential modulation of Bordetella pertussis virulence genes as evidenced by DNA microarray analysis. Mol. Genet. Genomics 269:475-486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kazmierczak, M. J., S. C. Mithoe, K. J. Boor, and M. Wiedmann. 2003. Listeria monocytogenes σB regulates stress response and virulence functions. J. Bacteriol. 185:5722-5734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Masarrat, J., and S. A. Hashsham. 2003. Customized cDNA microarray for expression profiling of environmentally important genes of Pseudomonas stutzeri strain KC. Teratogen. Carcinogen. Mutagen. 23:283-294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mathias, A. L., L. U. Rigo, S. Funayama, and F. O. Pedrosa. 1989. l-Arabinose metabolism in Herbaspirillum seropedicae. J. Bacteriol. 171:5206-5209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maurelli, A. T., R. E. Fernandez, C. A. Bloch, C. K. Rode, and A. Fasano. 1998. “Black holes” and bacterial pathogenicity: a large genomic deletion that enhances virulence of Shigella spp. and enteroinvasive Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:3943-3948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mongkolsuk, S., S. Rabibhadana, P. Vattanaviboon, and S. Loprasert. 1994. Generalized and mobilizable positive-selective cloning vectors. Gene 143:145-146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moore, R. A., D. DeShazer, S. Reckseidler, A. Weissmann, and D. E. Woods. 1999. Efflux-mediated aminoglycoside and macrolide resistance in Burkholderia pseudomallei. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:465-470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Novick, N. J., and M. E. Tyler. 1982. l-Arabinose metabolism in Azospirillum brasiliense. J. Bacteriol. 149:364-367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reckseidler, S. L., D. DeShazer, P. A. Sokol, and D. E. Woods. 2001. Detection of bacterial virulence genes by subtractive hybridization: identification of capsular polysaccharide of Burkholderia pseudomallei as a major virulence determinant. Infect. Immun. 69:34-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reed, L. J., and H. Muench. 1938. A simple method of estimating fifty percent endpoints. Am. J. Hyg. 27:493-497. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Saeed, A. I., V. Sharov, J. White, J. Li, W. Liang, N. Bhagabati, J. Braisted, M. Klapa, T. Currier, M. Thiagarajan, A. Sturn, M. Snuffin, A. Rezantsev, D. Popov, A. Ryltsov, E. Kostukovich, I. Borisovsky, Z. Liu, A. Vinsavich, V. Trush, and J. Quackenbush. 2003. TM4: a free, open source system for microarray data management and analysis. BioTechniques 34:374-378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schleif, R. 2003. AraC protein: a love-hate relationship. Bioessays 25:274-282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Simon, R., U. Priefer, and A. Puhler. 1983. A broad host range mobilization system for in vivo genetic engineering: transposon mutagenesis in gram negative bacteria. Bio/Technology 1:784-791. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sirisinha, S., N. Anuntagool, P. Intachote, V. Wuthiekanun, S. D. Puthucheary, J. Vadivelu, and N. J. White. 1998. Antigenic differences between clinical and environmental isolates of Burkholderia pseudomallei. Microbiol. Immunol. 42:731-737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]