Abstract

Oral infection of C57BL/6 mice with 100 cysts of the protozoan parasite Toxoplasma gondii results in the development of small intestinal Th1-type immunopathology. In contrast, infection with intestinal helminths results in the development of protective Th2-type responses. We investigated whether infection with the helminth Nippostrongylus brasiliensis influences the development of T. gondii-induced Th1 responses and immunopathology in C57BL/6 mice infected with T. gondii. Prior as well as simultaneous infection of mice with N. brasiliensis did not alter the course of infection with 100 cysts of T. gondii. Coinfected mice produced high levels of interleukin-12 (IL-12) and gamma interferon (IFN-γ), developed small intestinal immunopathology, and died at the same time as mice infected with T. gondii. Interestingly, local and systemic N. brasiliensis-induced Th2 responses, including IL-4 and IL-5 production by mesenteric lymph node and spleen cells and numbers of intestinal goblet cells and blood eosinophils, were markedly lower in coinfected than in N. brasiliensis-infected mice. Similar effects were seen when infection with 10 T. gondii cysts was administered following infection with N. brasiliensis. Infection of C57BL/6 mice with 10 T. gondii cysts prior to coinfection with N. brasiliensis inhibited the development of helminth-induced Th2 responses and was associated with higher and prolonged N. brasiliensis egg production. In contrast, oral administration of Toxoplasma lysate prior to N. brasiliensis infection had only a minor and short-lived effect on Th2 responses. Thus, N. brasiliensis-induced Th2 responses fail to alter T. gondii-induced Th1 responses and immunopathology, most likely because Th1 responses develop unchanged in C57BL/6 mice with a prior or simultaneous infection with N. brasiliensis. Our findings contribute to the understanding of immune regulation in coinfected animals and may assist in the design of immunotherapies for human Th1 and Th2 disorders.

Infection with the obligate intracellular protozoan parasite Toxoplasma gondii is acquired primarily through the inadvertent ingestion of undercooked or raw meat containing tissue cysts or of food or water contaminated with oocysts shed by cats (24). Therefore, initial entry of the parasite and the interaction with the host immune system take place in the intestine. Infection with 10 cysts of the ME49 strain of T. gondii results in a Th1-type response characterized by the production of gamma interferon (IFN-γ) by lymphocyte populations in the small intestine (7, 8, 11, 24) and later in the periphery (8). Regardless of the genetic background, mice survive acute infection with 10 cysts and develop cysts in their brains. In contrast, infection with 100 cysts of the same strain of T. gondii results in death of C57BL/6 mice at 7 to 13 days after infection, whereas BALB/c mice survive (27). Susceptible C57BL/6 mice develop massive necrosis in their small intestines, which is associated with Th1-type immunopathology mediated by CD4+ T cells secreting IFN-γ, tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), and NO in the small intestinal lamina propria (20, 26, 27, 33).

This situation contrasts with that occurring during infection with gastrointestinal nematodes, e.g., Nippostrongylus brasiliensis. Third-stage larvae of mouse-adapted strains of the parasite infect mice through the skin, migrate to the lungs, are coughed up and swallowed, and develop into mature adults. These reside in the gut lumen, produce eggs that are excreted in the feces, and are themselves expelled (36, 47). Th2-type responses characterized by CD4+ T-cell-mediated overlapping and additive functions of interleukin-4 (IL-4), IL-5, and IL-13 develop and result in blood eosinophilia, increases in serum immunoglobulin E (IgE), intestinal mastocytosis, and expulsion of the parasite (23, 31, 47). The gastrointestinal phase of the Th2 response is initiated after 5 to 6 days, and a maximum cytokine response is observed 10 to 14 days following infection (14, 34).

Since coinfections are a widespread problem in the developing world (2), analysis of immune responses in mice with concurrent infections has gained increasing interest. Particular interest has centered on the analysis of immune responses to concurrent infections with Th2-inducing organisms (helminths) and Th1-inducing organisms (intracellular pathogens), since these responses may have reciprocal counterregulatory properties. However, little is known about local immune responses, e.g., in the gut in coinfected hosts. Recently, Marshall et al. (30) reported that C57BL/6 mice chronically infected with Schistosoma mansoni and subsequently infected with 100 cysts of T. gondii show elevated plasma TNF-α and aspartate transaminase levels associated with severe liver pathology and subsequent death. Interestingly, Th2 responses mounted after infection with S. mansoni appeared to have ameliorated the intestinal Th1-type immunopathology in T. gondii-infected mice (34). However, those authors did not focus their study on local immune responses in the small intestine but instead focused on those systemic responses resulting in liver pathology and mortality. Khan et al. (21) reported a protective role of infection with the nematode Trichinella spiralis in a murine model of Th1-driven experimental colitis. Furthermore, eggs of helminthes were shown to ameliorate experimental colitis in mice (12), and products of Ascaris suum skewed immune responses against ovalbumin towards a Th2-type response (37).

In the present study, we used a model of coinfection with N. brasiliensis and T. gondii as two paradigm Th2 and Th1 pathogens to investigate reciprocal counterregulatory properties of these organisms. We found that infection of C57BL/6 mice with N. brasiliensis did not alter immune responses to subsequent infection with 100 cysts of T. gondii and did not alleviate gut pathology or prevent death of mice. The lack of counterregulatory effects of infection with N. brasiliensis was also observed after coinfection with 10 cysts of T. gondii. In contrast, infection with T. gondii markedly suppressed both established and developing Th2 responses induced by infection with N. brasiliensis. Down-regulatory properties of infection with T. gondii on N. brasiliensis-induced Th2 responses were dependent on the genetic background of the mice and live parasites.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals, parasites, and parasite antigen.

Female C57BL/6, BALB/c, and NMRI mice were bred and maintained under specific-pathogen-free conditions in the animal facility of the Institut für Infektionsmedizin, Charité Campus Benjamin Franklin. Sex- and age-matched mice were 8 to 12 weeks of age when used, and there were at least five mice in each experimental group for the study of mortality and three mice in each group for the remaining analyses. Each experiment was repeated at least three times unless otherwise indicated. Cysts of the ME49 strain of T. gondii (kindly provided by J. S. Remington, Research Institute, Palo Alto Medical Foundation, Palo Alto, Calif.) were obtained from brains of NMRI mice that had been infected intraperitoneally (i.p.) with 10 cysts for 2 to 3 months as previously described (6). For peroral infection, mice were infected with either 100 or 10 cysts by gavage. A mouse-adapted strain of N. brasiliensis was maintained and passed in Lewis rats at the Zentrum für Infektionsforschung, Universität Würzburg. Feces were collected from stock rats and served as a source of L3 after incubation of the fecal slurry. Seven hundred fifty L3 larvae were injected subcutaneously (s.c.) to establish infection. All animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Review Board.

Toxoplasma lysate antigen (TLA) was prepared by sonification of tachyzoites obtained from the peritoneal cavities of BALB/c mice infected 3 days prior with 106 tachyzoites of the virulent BK strain of T. gondii (kindly provided by K. Janitschke, Robert Koch-Institut, Berlin, Germany). For in vivo experiments, 1,000 μg was administered orally by gavage. For in vitro restimulation of cells, TLA was prepared as described above; optimal concentrations of TLA were determined prior to use.

N. brasiliensis egg counts.

To enumerate N. brasiliensis eggs, stool samples from infected mice were collected for 24 h. Stool samples from mice in one group were pooled, and two aliquots of 0.3 g of stool each were processed individually for microscopy. The number of N. brasiliensis eggs in three aliquots of 20 μl of supernatant each was counted by two investigators (O.L. and I.R.D.). The numbers of eggs in stool samples are given number per gram of stool per 24 h.

Histopathology.

Mice were euthanatized by asphyxiation with CO2 at indicated time points after infection (14 days after infection with N. brasiliensis). Their small intestines were fixed in a solution containing 10% formalin, 70% ethanol, and 5% acetic acid. Sections of small intestines were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). The length of necrosis in the ileum was measured with a ruler. Three villi chosen at random from the proximal and distal areas of the small intestine were evaluated microscopically to measure the numbers of goblet cells. Sections were stained by the immunoperoxidase method with rabbit anti-T. gondii IgG antibody as previously described (10). Briefly, a female Sandy-Loop rabbit was infected orally with 20 cysts of the ME49 strain of T. gondii. A s.c. challenge infection with the virulent BK strain (105 tachyzoites) was given 4 weeks later. Anti-T. gondii antibody titers were >1:10.000. The numbers of parasitophorous vacuoles that contained tachyzoites in the ileum were counted at a magnification of ×400 in two areas of 1 cm in length (one in the proximal part and the other in the distal part) chosen at random for each section. Results of histological evaluations were consistent between individual mice in the same group.

Blood eosinophil numbers and serum IgE levels.

Blood smears were prepared and analyzed for numbers of eosinophils following Pappenheim staining (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany). One hundred white cells were counted per mouse, and the number of eosinophils per 100 white cells was determined. Total serum IgE levels were measured by using the OptEIA Mouse IgE Set (PharMingen, Hamburg, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Lymphocyte culture and cytokine responses.

Mesenteric lymph nodes (MLN) and spleens were removed from mice, and single-cell suspensions were prepared. Cells were resuspended in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, 2 mM l-glutamine, 100 U of penicillin per ml, and 100 μg of streptomycin per ml (all from Biochrom, Berlin, Germany) and left untreated or stimulated at 37°C and 5% CO2 with a predetermined optimal concentration of either concanavalin A (ConA) (5.0 μg/ml) (Sigma, Deisenhofen, Germany) or TLA (5.0 μg/ml). Cell-free supernatants were harvested after 48 h and stored at −70°C.

Cytokine assays.

Cytokine analysis was carried out by sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) with paired monoclonal antibodies to detect IL-4 (clones 11B11 and BVD6-24G2), IL-5 (clones TRFK5 and TRFK4), IL-10 (clones JES5-2A5 and SXC-1), IL-12 (clones C15.6 and C17.8), IFN-γ (clones R4-6A2 and XMG1.2), and TNF-α (clones G281-2626 and MP6-XT3) (all PharMingen). IL-13 was detected by sandwich ELISA with paired monoclonal antibodies (clones 38213.11 and BAF413; R&D Systems, Wiesbaden, Germany). Cytokines were quantified by reference to commercially available recombinant murine standards (all from PharMingen except for recombinant IL-13 [R&D Systems]), and the sensitivity of the assays was determined by calculation of the mean ± 3 standard deviations (SD) for medium controls.

Statistics.

Levels of significance for time to death and mortality of mice, histological changes, numbers of parasitophorous vacuoles containing tachyzoites, levels of serum IgE, blood eosinophils, and cytokine production were determined by using Student's t test and the alternate Welsh t test. Nonparametric analyses were conducted with the Wilcoxon rank sum test. Probability values of <0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

Experimental design.

s.c. infection with N. brasiliensis results in egg deposition by mature adult worms in the small intestines at 5 to 6 days after infection, which is associated with a strong intestinal Th2-type cytokine response that peaks at 10 to 14 days after infection. Oral infection of susceptible mice with 100 cysts of T. gondii results in massive replication of the parasite in the small intestines, and T. gondii replication is associated with a strong local Th1-type response that results in development of necrosis in their ilea and death of mice at 7 to 13 days after infection (20, 26, 27). To synchronize maximum immune responses in the intestines, we infected mice s.c. with 750 LIII larvae of N. brasiliensis at day 0 and coinfected these mice orally with 100 or 10 cysts of the ME49 strain of T. gondii 7 days later. In a second series of experiments, the reverse sequence of infections was used: 10 cysts of T. gondii were orally administered 2 or 4 weeks prior to infection with N. brasiliensis. Furthermore, 1,000 μg of TLA was orally administered to C57BL/6 mice 1, 2, or 4 weeks before infection with N. brasiliensis. Analyses of systemic and local immune responses were performed at 14 days after N. brasiliensis infection in all experiments.

Infection with N. brasiliensis does not prevent Th1-mediated immunopathology following oral infection of C57BL/6 mice with T. gondii.

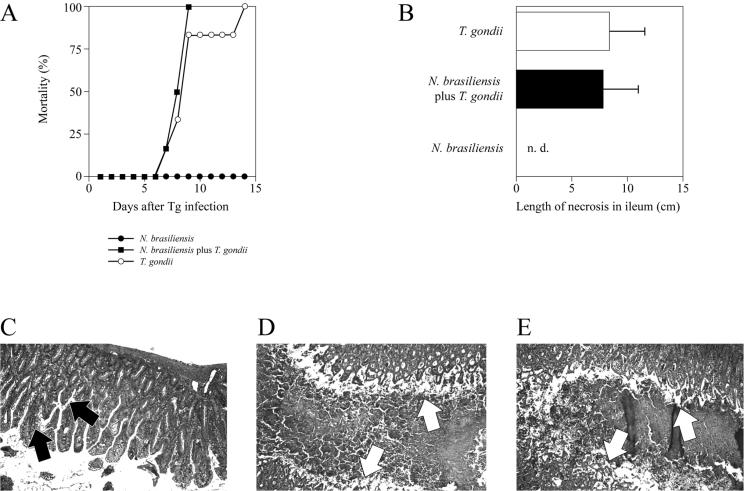

Since infection with S. mansoni was reported to ameliorate Th1-type immunopathology following oral infection with 100 cysts of T. gondii (but instead resulted in lethal TNF-α-mediated liver pathology) (30), we investigated whether coinfection with N. brasiliensis prevented immunopathology without causing lethal TNF-α-mediated liver pathology. Mice coinfected with N. brasiliensis and subsequently with T. gondii did not differ in their mortality and time to death from mice infected with T. gondii alone (Fig. 1A). Both coinfected mice and mice infected with T. gondii alone showed large areas of necrosis in the ilea (Fig. 1B, D, and E), whereas mice infected with N. brasiliensis did not develop intestinal necrosis (Fig. 1B); the latter mice also showed increased goblet cell numbers in the gut (Fig. 1C). We did not observe significant differences in numbers of parasitophorous vacuoles containing T. gondii tachyzoites in the ilea of coinfected mice and mice infected with T. gondii alone (mean numbers of parasitophorous vacuoles ± SD in 3 mice were 62.50 ± 37.94/cm of ileum and 75.33 ± 67.29/cm of ileum, respectively). Furthermore, the numbers and sizes of inflammatory infiltrates around vessels and in the parenchyma of livers were similar in the two groups of mice (data not shown). These results indicate that infection with N. brasiliensis does not alter the course of infection with 100 cysts of T. gondii and does not induce lethal TNF-α-mediated liver pathology.

FIG. 1.

Infection with N. brasiliensis does not prevent early death and intestinal pathology in C57BL/6 mice infected with 100 cysts of T. gondii. Mice were infected with N. brasiliensis (750 LIII larvae s.c.) and orally challenged with 100 cysts of T. gondii 7 days thereafter. Mortality (A) was documented daily. Small intestines were removed from mice infected with N. brasiliensis (C), N. brasiliensis plus T. gondii (D), or T. gondii (E) at 7 days after infection with T. gondii or 14 days after infection with N. brasiliensis, immediately fixed, and stained with H&E. Arrows in panel C indicate goblet cells; arrows in panels D and E delineate the borders between the mucosal surface and lumen of the small intestines filled with necrotic material (original magnification, ×40). (B) The length of small intestinal necrosis in coinfected mice was determined in H&E-stained sections by using a ruler. Results are expressed as mean + SD. n.d., not detectable. The length of necrosis did not differ significantly in coinfected mice and those infected with T. gondii alone; necrosis was not detectable in N. brasiliensis-infected mice (P < 0.001 versus mice infected with N. brasiliensis).

Coinfected mice show decreased systemic and local Th2 responses, while Th1 responses develop unchanged, compared to those in mono-infected mice.

To investigate the reasons for the unaltered course of infection with T. gondii in coinfected mice, we compared local and systemic markers of Th1 and Th2 responses in coinfected compared to mono-infected mice.

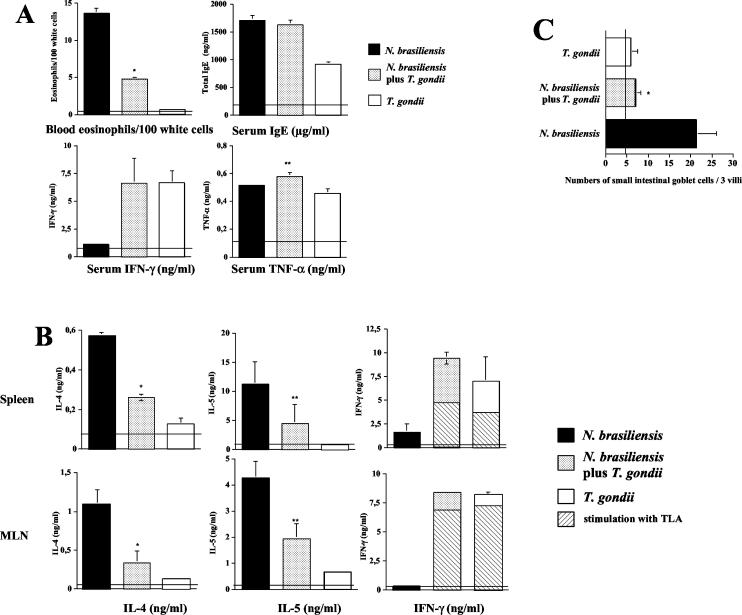

Mice infected with N. brasiliensis showed increases in typical Th2 markers, including blood eosinophilia, elevated serum IgE levels (Fig. 2A), and increased concentrations of IL-4 and IL-5 in supernatants of spleen and MLN cells (Fig. 2B). We found increased IL-13 concentrations early (days 3 and 6) after infection with N. brasiliensis; IL-13 was not detectable at the time of coinfection (day 7) and at 14 days after infection in any group (data not shown). In contrast, infection with T. gondii resulted in a marked increase in the production of Th1 markers, including IFN-γ in serum (Fig. 2A) and in supernatants of spleen and MLN cells (Fig. 2B).

FIG. 2.

Coinfection with T. gondii inhibits systemic and local Th2 immune responses in mice with established N. brasiliensis infection. C57BL/6 mice were infected with N. brasiliensis (750 LIII larvae s.c.) and orally challenged with 100 cysts of T. gondii 7 days thereafter. (A) At 7 days after T. gondii infection, blood was obtained. Blood smears were prepared and analyzed following Pappenheim staining; concentrations of total IgE, IFN-γ, and TNF-α in serum were determined by ELISA as described in Materials and Methods. Horizontal lines indicate numbers or concentrations in naive control mice. Results (expressed as mean + SD) of one representative experiment of three performed are shown. *, numbers of eosinophils per 100 white cells were significantly reduced in coinfected mice compared to mice infected with N. brasiliensis alone (P = 0.0022). **, TNF-α levels were significantly increased in coinfected mice compared to mice infected with T. gondii alone (P > 0.05). (B) Spleen and MLN cells were prepared and cultured in the presence of ConA (or TLA, as indicated by hatched bars) for 48 h. Levels of IL-4, IL-5, and IFN-γ in supernatants were determined by ELISA. Horizontal lines indicate cytokine levels in naive mice. Results (expressed as mean + SD) of one representative experiment of three performed are shown. *, P < 0.002 compared to levels in mice infected with N. brasiliensis alone; **, P < 0.01 compared to mice infected with N. brasiliensis alone. (C) Numbers of small intestinal goblet cells in three villi chosen at random were determined microscopically; the vertical line indicates goblet cell numbers in naive mice. Pooled results obtained by two independent investigators + SD are given (*, P = 0.0009 versus N. brasiliensis-infected mice).

In coinfected mice, we observed a marked reduction in the numbers of blood eosinophils and IL-4 and IL-5 concentrations in spleens and MLN compared to N. brasiliensis-infected mice (Fig. 2A and B). In contrast, concentrations of IFN-γ in serum and in supernatants of spleen and MLN cells following in vitro restimulation with ConA were markedly increased in coinfected mice compared to N. brasiliensis-infected mice; concentrations in coinfected mice were similar to those observed in T. gondii-infected mice (Fig. 2A and B). The observed increases in IFN-γ concentrations appeared to be T. gondii specific, since in vitro restimulation of spleen and MLN cells with TLA resulted in IFN-γ concentrations that were between 40 and 90% of those obtained after in vitro restimulation with ConA (Fig. 2B). The production of IL-12 was significantly increased in supernatants of MLN cells in coinfected mice compared to mice infected with N. brasiliensis alone (mean IL-12 concentrations ± SD in three mice were 0.53 ± 0.05 and 1.11 ± 0.17 ng/ml; P < 0.0001) but did not differ between coinfected mice and mice infected with T. gondii alone. Serum levels of TNF-α increased to moderate levels following infection with either pathogen alone (Fig. 2A); coinfected mice had increased TNF-α levels compared to T. gondii-infected mice (Fig. 2A). Both infection with N. brasiliensis and infection with T. gondii resulted in increased IL-10 production in supernatants of spleen and MLN cells; these levels did not differ significantly in N. brasiliensis-infected, T. gondii-infected, or coinfected mice (data not shown). IgE concentrations were increased to similar levels in sera of N. brasiliensis-infected mice and coinfected mice (Fig. 2A); infection with T. gondii resulted in a less pronounced increase in serum IgE levels. In addition to the above-mentioned changes in immunological parameters, we also observed markedly reduced numbers of small intestinal goblet cells in coinfected compared to N. brasiliensis-infected mice; goblet cell numbers in the former mice did not differ from those in mice infected with T. gondii (Fig. 2C).

These results indicate that N. brasiliensis does not alter T. gondii-induced Th1 responses and therefore does not alter the clinical course of infection with 100 cysts of T. gondii. In contrast, infection with T. gondii shows a dramatic down-regulation of N. brasiliensis-induced local and systemic Th2 responses.

Infection with N. brasiliensis does not alter Th1 responses in mice infected with a low dose of T. gondii, but established Th2 responses induced by N. brasiliensis infection are down-regulated by T. gondii infection.

Since infection with N. brasiliensis did not alter Th1 responses induced by infection with 100 cysts of T. gondii, we infected mice with a 10-fold-lower inoculum of T. gondii (which results in protective rather then pathological Th1 responses). We observed that levels of IFN-γ in spleens and MLN did not differ in coinfected mice and mice infected with T. gondii alone on day 14 after infection with N. brasiliensis. In contrast, markers of Th2 responses, including blood eosinophil numbers and levels of IL-4 and IL-5 in spleens and MLN, were significantly and markedly lower in coinfected than in N. brasiliensis-infected mice (Table 1). These results indicate that infection with N. brasiliensis does not alter protective Th1 responses induced by infection with 10 cysts of T. gondii. In contrast, systemic and local Th2 responses induced by N. brasiliensis are down-regulated by concurrent infection with T. gondii. Infection with either 10 or 100 cysts of T. gondii thus is sufficient to down-regulate helminth-induced Th2 responses.

TABLE 1.

Markers of Th1- and Th2-type responses in blood, MLN, and spleens in C57BL/6 mice coinfected with N. brasiliensis and 10 cysts of T. gondiia

| Marker (unit) | Organ | Valve for the following group of mice:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Naive | Monoinfected with N. brasiliensis (compared to naive mice) | Coinfected with N. brasiliensis and T. gondii (compared to N. brasiliensis-infected mice) | Monoinfected with T. gondii (compared to naive mice) | ||

| Eosinophils (no./100 white cells) | Blood | 0.2 ± 0.21 | 6.0 ± 1.6b | 1.0 ± 0.8c | 0.8 ± 0.9d |

| Total IgE (μg/ml) | Serum | 0.4 ± 0.1 | 0.9 ± 0.1b | 0.8 ± 0.1d | 0.2 ± 0.1d |

| MLN | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 1.3 ± 0.4b | 0.4 ± 0.1c | 0.3 ± 0.1d | |

| IL-4 (ng/ml) | |||||

| Spleen | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 1.8 ± 0.3b | 0.5 ± 0.2c | 0.2 ± 0.1d | |

| MLN | 0.1 ± 0.1 | 0.8 ± 0.1b | 0.1 ± 0.1c | 0.1 ± 0.1d | |

| IL-5 (ng/ml) | |||||

| Spleen | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 1.1 ± 0.1b | 0.3 ± 0.1c | 0.1 ± 0.1d | |

| MLN | 1.0 ± 0.4 | 0.5 ± 0.1d | 4.4 ± 0.9b | 4.4 ± 1.1b | |

| IFN-γ (ng/ml) | |||||

| Spleen | 0.2 ± 0.3 | 1.0 ± 0.2d | 4.3 ± 0.1b | 4.1 ± 0.3b | |

C57BL/6 mice were infected s.c. with 750 stage III larvae of N. brasiliensis and perorally with 10 cysts of T. gondii 7 days thereafter. Blood, spleens, and MLN were obtained at 14 days after infection with N. brasiliensis from all mice. Mononuclear cells were cultured in the presence of ConA (5 μg/ml). Supernatants were harvested after 48 h of culture.

Significant increase (P < 0.05) compared to indicated control group.

Significant decrease (P < 0.05) compared to indicated control group.

No difference compared to indicated control group.

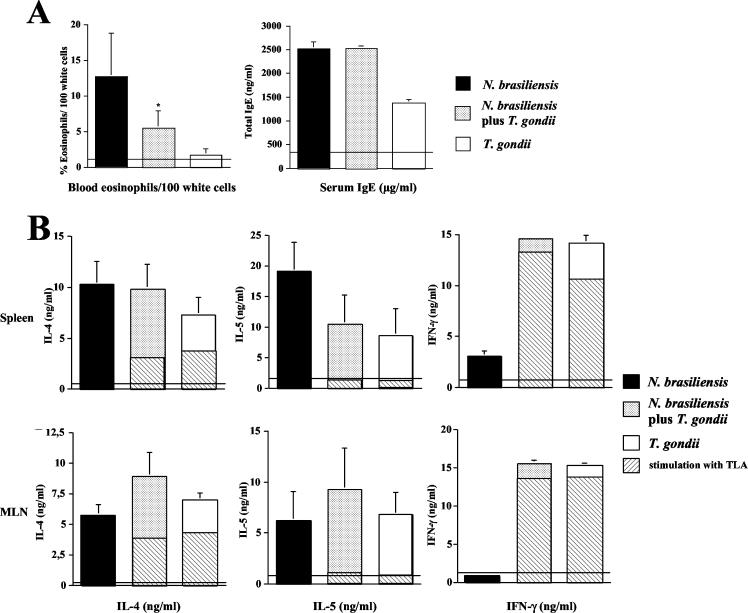

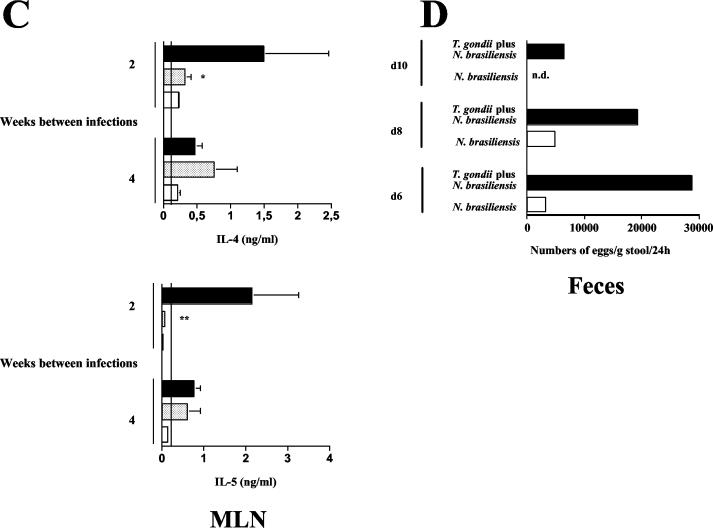

Down-regulation of established Th2 responses by T. gondii infection is dependent on the genetic background of the mice.

Since immune responses to infection with T. gondii and other parasites are genetically regulated (24, 27, 45, 53), we coinfected BALB/c mice with N. brasiliensis and T. gondii. Coinfection resulted in down-regulation of blood eosinophil numbers compared to infection with N. brasiliensis alone; serum IgE concentrations did not differ significantly between the two groups (Fig. 3A). However, in striking contrast to the results obtained with C57BL/6 mice, N. brasiliensis-induced IL-4 and IL-5 production remained unchanged in spleens and MLN of coinfected mice (Fig. 3B). Serum levels of IL-4 and IL-5 were unchanged in mice infected with N. brasiliensis alone and in coinfected mice (data not shown). We observed high IFN-γ concentrations in the same organs, and IFN-γ concentrations did not differ in spleens and MLN in coinfected and T. gondii-infected BALB/c mice. IFN-γ concentrations in supernatants from cells restimulated in vitro with ConA and TLA did not differ between coinfected mice and those infected with T. gondii alone. We found that IL-4 and IL-5 concentrations in supernatants as measured by ELISA were markedly higher following restimulation of spleen and MLN cells with ConA compared to restimulation with TLA, whereas IFN-γ concentrations in the same supernatants were similar (Fig. 3B). In conclusion, both C57BL/6 and BALB/c mice developed marked Th1 responses upon infection with T. gondii; however, the down-regulation of systemic and local N. brasiliensis-induced Th2 response was only observed in C57BL/6 mice, suggesting that the genetic background of the mice affects the modulatory capacity of T. gondii-induced Th1 responses.

FIG. 3.

Down-regulation of N. brasiliensis-induced Th2 responses by T. gondii is dependent on the genetic background of mice. BALB/c mice were infected with N. brasiliensis (750 LIII larvae s.c.) and orally challenged with 10 cysts of T. gondii 7 days thereafter. (A) At 7 days after T. gondii infection, blood was obtained. Blood smears were prepared and analyzed following Pappenheim staining. Horizontal lines indicate levels in naive mice. Results (expressed as mean + SD) of one representative experiment of three performed are shown. *, P = 0.038 compared to mice infected with N. brasiliensis alone. (B) Spleen and MLN cells were prepared and cultured in the presence of ConA (or TLA, as indicated by hatched bars) for 48 h. Levels of IL-4, IL-5, and IFN-γ in supernatants were determined by ELISA. Horizontal lines indicate cytokine levels in noninfected mice. Results (expressed as mean + SD) of one representative experiment of three performed are shown.

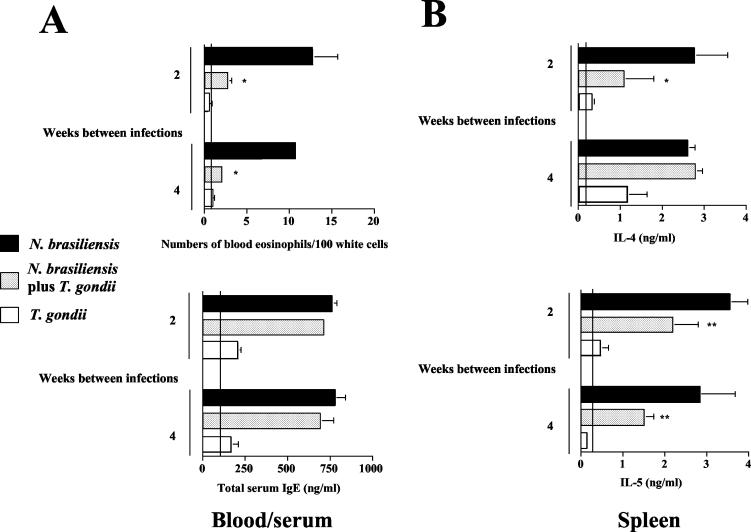

Prior infection with T. gondii suppresses the development of local and systemic N. brasiliensis-induced Th2 immune responses.

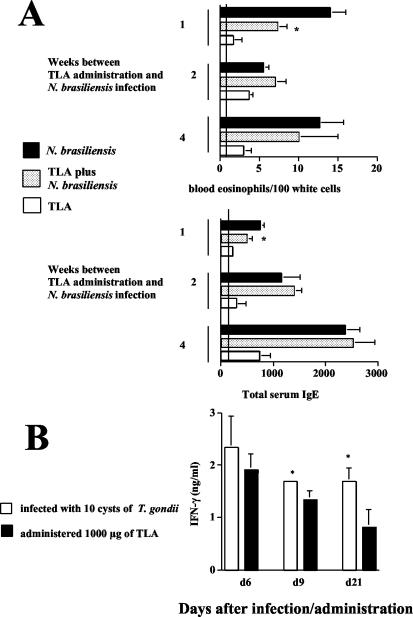

The results described above show that oral infection with T. gondii reduces the strength of established helminth-induced Th2 responses in C57BL/6 mice. To investigate whether oral infection with T. gondii can also suppress the development of N. brasiliensis-induced Th2 responses, we reversed the sequence of infections. Ten cysts of T. gondii were orally administered 2 or 4 weeks prior to infection with N. brasiliensis. When mice were infected with N. brasiliensis at 2 weeks after oral infection with T. gondii, we observed a significant reduction in N. brasiliensis-induced eosinophilia compared to mice infected with N. brasiliensis alone (Fig. 4A). Total serum IgE levels were increased in N. brasiliensis-infected and coinfected mice but did not differ significantly between these groups (Fig. 4A). The production of IL-4 and IL-5 by spleen (Fig. 4B) and MLN (Fig. 4C) cells was increased in N. brasiliensis-infected compared to naive mice; mice that had been infected with T. gondii 2 weeks prior to infection with N. brasiliensis showed significantly lower levels of these cytokines than mice infected with N. brasiliensis alone. The suppression of Th2 cytokines also correlated with markedly higher and prolonged N. brasiliensis egg production (Fig. 4D).

FIG. 4.

Prior infection with T. gondii suppresses the development of N. brasiliensis-induced Th2 responses. C57BL/6 mice were infected with 10 cysts of T. gondii and challenged s.c. with 750 LIII larvae of N. brasiliensis 2 or 4 weeks thereafter. (A) At 14 days after infection with N. brasiliensis, blood was obtained. Blood smears were prepared and analyzed following Pappenheim staining; concentrations of total IgE in serum were determined by ELISA. Vertical lines indicate levels in naive control mice. Results (expressed as mean + SD) of one representative experiment of three performed are shown. *, P < 0.001 compared to mice infected with N. brasiliensis alone. (B and C) Spleen (B) and MLN (C) cells were prepared and cultured in the presence of ConA for 48 h. Levels of IL-4, IL-5, and IFN-γ in supernatants were determined by ELISA. Vertical lines indicate cytokine levels in naive mice. Results (expressed as mean + SD) of one representative experiment of three performed are shown. *, P < 0.02 compared to mice infected with N. brasiliensis alone. **, P < 0.025 compared to mice infected with N. brasiliensis alone. (D) N. brasiliensis egg production was determined microscopically from group samples of feces collected for 24 h at the indicated time points. n.d., not detectable.

Interestingly, when the time between infection with T. gondii and infection with N. brasiliensis was prolonged to 4 weeks, the observed suppressive effect of infection with T. gondii on N. brasiliensis-induced Th2 responses was observed for blood eosinophil numbers and IL-5 production only by spleen cells and not by MLN cells (Fig. 4B and C). Taken together, these results indicate that infection with T. gondii markedly reduces not only established but also developing local and systemic N. brasiliensis-induced Th2 responses. The suppressive effect appeared to be short-lived locally (in MLN) but more sustained in the periphery (blood and spleen).

Oral administration of TLA results in only weak and short-lived down-regulation of N. brasiliensis-induced Th2 responses.

The results presented thus far showed a marked suppressive effect of infection with T. gondii on both developing and established Th2 responses. Since injection of TLA has been reported to result in the rapid induction of IL-12 by splenic dendritic cells (39), TLA (rather than infection with T. gondii) was used to modulate helminth-induced Th2 responses. For this purpose, 1,000 μg of TLA was administered orally to C57BL/6 mice 1, 2, or 4 weeks prior to infection with N. brasiliensis. TLA treatment at 1 but not 2 or 4 weeks before infection resulted in a significant reduction in N. brasiliensis-induced blood eosinophilia compared to that in control mice (Fig. 5A). Serum IgE levels showed a mild reduction in those mice treated with TLA at 1 but not 2 or 4 weeks before infection with N. brasiliensis compared to mice infected with N. brasiliensis alone (Fig. 5A). Systemic and local markers of Th2 responses, including IL-4 and IL-5 production in spleens and MLN, did not differ between TLA-treated, N. brasiliensis-infected mice and mice infected with N. brasiliensis alone (data not shown).

FIG. 5.

Oral administration of TLA results in weak and short-lived suppression of N. brasiliensis-induced Th2 responses. Groups of mice were orally given 1,000 μg of TLA by gavage and infected with 750 LIII larvae of N. brasiliensis s.c. 7, 14, and 28 days thereafter. (A) At 14 days after infection with N. brasiliensis, blood smears were prepared and analyzed by Pappenheim staining; total serum IgE concentrations were determined by ELISA. Vertical lines indicate levels in noninfected control mice. Results (expressed as mean + SD) of one representative experiment are shown. *, P < 0.02 compared to mice infected with N. brasiliensis. (B) To compare levels of IFN-γ production, C57BL/6 mice either were given 1,000 μg of TLA by gavage or were infected with 10 cysts of T. gondii orally. At the indicated time points, MLN were isolated and IFN-γ production was measured by ELISA following in vitro restimulation with TLA.

To understand differences in the modulatory capacity of TLA versus infection with live parasites, the production of IFN-γ in MLN in mice administered TLA or infected with T. gondii was determined. Six days after oral administration of TLA, IFN-γ production by MLN was increased, but it significantly declined at 9 and 21 days (Fig. 5B). In contrast, T. gondii-infected mice showed high levels of IFN-γ that were maintained throughout the observation period; mice infected with T. gondii showed significantly higher IFN-γ levels in MLN at 9 and 21 days than mice administered TLA (Fig. 5B). Interestingly, in vitro restimulation of MLN cells with TLA resulted in increased IFN-γ production by cells obtained from infected mice, whereas cells obtained from mice that had received TLA did not increase their IFN-γ production. These results indicate that administration of TLA provides only short-term and mild suppressive effects on N. brasiliensis-induced Th2 responses. The suppressive effect was tightly associated with production of IFN-γ.

DISCUSSION

The generation of Th1 effector cells that produce IFN-γ promotes protection against intracellular pathogens but may lead to immunopathology. In contrast, Th2 effector cells produce IL-4 and promote protection against helminthes but are also involved in allergic responses. Since each cytokine pattern is known to inhibit production of the opposing pattern, recent interest has focused on the modulation of Th1-type (Crohn's disease and rheumatoid arthritis) or Th2-type (allergy) immunopathologies by using microorganisms and their products (12-14, 16, 18, 21, 29, 30, 37, 44, 50).

We have previously reported that C57BL/6 mice develop Th1-type immunopathology characterized by severe small intestinal necrosis and early death following peroral infection with T. gondii (27). These pathological changes are mediated by (over)production of IFN-γ, TNF-α, and NO (20, 26, 27, 33) and therefore show broad similarities with the immunopathology observed in patients with Crohn's disease and murine models of inflammatory bowel disease (25). To investigate the capacity of Th2 microorganisms to modulate T. gondii-induced Th1 immunopathology, Marshall and coworkers (3, 30) coinfected mice with the trematode S. mansoni and T. gondii. The polarized Th2 responses induced by infection with S. mansoni blocked IFN-γ and NO production and appeared to have ameliorated the intestinal pathology associated with T. gondii infection. However, TNF-α-mediated severe liver pathology developed and resulted in the death of coinfected mice (30). We therefore chose a different helminth, N. brasiliensis, and studied its capacity to modulate T. gondii-induced Th1 immunopathology. Comparing local and systemic immune responses, the present study focused on the importance of (i) the sequence and dose of infection, (ii) the genetic background of the mice, and (iii) differences between effects induced by live parasites and by a Toxoplasma lysate.

We observed that infection of C57BL/6 mice with N. brasiliensis did not protect against the development of T. gondii-induced Th1-type immunopathology. Coinfected mice did not differ in the time to death, the extent of intestinal necrosis, or the numbers of Toxoplasma parasites following infection with 100 cysts of T. gondii. The lack of modulatory effects was likely caused by the failure to alter the development of T. gondii-induced Th1 responses. Infection with N. brasiliensis failed to suppress T. gondii-specific IFN-γ production. In striking contrast, coinfection with T. gondii had a dramatic down-regulatory effect on Th2 responses. Whereas N. brasiliensis-infected mice mounted strong systemic and local Th2 responses (increases in serum IgE, IL-4, IL-5, blood eosinophils, and goblet cell numbers), these Th2 markers were all markedly down-regulated in coinfected mice. Whereas the decreased production of IL-5 (which is known to promote eosinophil differentiation and the release of eosinophils from the bone marrow into the circulation [9, 22]) was associated with a decrease in numbers of blood eosinophils and intestinal goblet cells in coinfected mice, down-regulation of IL-4 in coinfected mice did not significantly alter serum IgE levels throughout the experiments performed. We speculate that the sensitivity of eosinophils to the counterregulatory effects of IFN-γ may be higher than the sensitivity of IgE to the effects of IFN-γ during N. brasiliensis infection (46). Alternatively, the long half-life of IgE and the fact that total rather than N. brasiliensis-specific IgE was determined in the present study may have contributed to the lack of down-regulation of IgE in coinfected mice.

The lack of counterregulatory effects of N. brasiliensis infection on the development of Th1 immunopathology and parasite replication is in striking contrast to the findings for mice coinfected with S. mansoni and T. gondii (3, 30). These results may be caused by differences in the strength of Th2 responses, since eggs of S. mansoni are known to induce vigorous Th2 responses that modulate Th1 responses in murine and human Th1-dominated infections (1, 5, 38). In this regard, serum TNF-α levels were increased in mice coinfected with N. brasiliensis and T. gondii; however, TNF-α concentrations in coinfected mice in our study were markedly lower than those reported to cause lethal liver pathology in mice coinfected with S. mansoni and T. gondii (30).

One may argue that the experimental design chosen in the present study did not allow exclusion of the time between infections as an important factor for counterregulatory effects. However, mice infected simultaneously with N. brasiliensis and T. gondii as well as mice with a secondary N. brasiliensis infection also developed Th1-type immunopathology (data not shown). We therefore investigated whether protective (10-cyst infection [8, 11]) rather than detrimental (100-cyst infection) Th1 immune responses can be counterregulated by N. brasiliensis-induced Th2 responses. N. brasiliensis-induced Th2 responses were unable to counterregulate Th1 responses associated with a nonlethal 10-cyst infection with T. gondii. Systemic and local Th2 markers were markedly decreased in coinfected compared to N. brasiliensis-infected mice, whereas IFN-γ production was similar in the two groups. Thus, N. brasiliensis-induced Th2 responses, regardless of (i) the inoculum size, (ii) the time point of coinfection and (iii) the quality of the Th1 response (protective or detrimental), were insufficient to counterregulate T. gondii-induced Th1 responses. In contrast, infection with T. gondii, regardless of the inoculum size, showed a marked down-regulatory effect on N. brasiliensis-induced Th2 responses.

Since susceptibility to infection with T. gondii is genetically regulated (11, 27, 45) and C57BL/6 mice are known to mount strong Th1 responses, we investigated the down-regulatory capacity of N. brasiliensis-induced Th2 responses on T. gondii-induced Th1 responses in BALB/c mice, which are known to mount strong Th2 responses. Interestingly, BALB/c mice coinfected with N. brasiliensis and 10 cysts of T. gondii showed the simultaneous presence of Th1 and Th2 markers. MLN and spleens of coinfected mice showed increases in IL-4 and IL-5 as well as IFN-γ production compared to those of control mice. However, levels of Th2 markers in the two groups of mice did not differ. In BALB/c but not C57BL/6 mice, infection with T. gondii alone was associated with increased production of IL-4 and IL-5. This marked production of IL-4 and IL-5 was observed only in supernatants of cells restimulated in vitro with ConA and not in those restimulated with TLA. The role of Th2 cytokines in infection with T. gondii is controversial. IL-4 has been reported to contribute to protection against infection with T. gondii by preventing overwhelming Th1 responses (41), whereas IL-5 plays a detrimental role during acute (35) and a protective role during chronic (49) infection with T. gondii.

Since N. brasiliensis-induced Th2 responses were down-regulated by subsequent infection with T. gondii, we investigated immune regulation during the reverse sequence of infections (infection with T. gondii followed by infection with N. brasiliensis). Strong suppressive effects of T. gondii-induced Th1 responses on the development of systemic and local N. brasiliensis-induced Th2 responses were found when infection with T. gondii was followed 2 weeks later by infection with N. brasiliensis. The suppression of Th2 responses in coinfected mice also resulted in increased and prolonged N. brasiliensis egg production. Of interest is that the suppressive effect of infection with T. gondii on developing N. brasiliensis-induced Th2 responses waned when infections were given 4 weeks apart.

Since infection with T. gondii strongly suppressed the development of N. brasiliensis-induced Th2 responses, we finally asked whether a similar suppression of Th2 responses is achievable by using a TLA. When oral administration of TLA preceded infection with N. brasiliensis by 1 but not 2 or 4 weeks, a mild and transient suppression of N. brasiliensis-induced blood eosinophilia was observed. This effect was associated with increases in IFN-γ production in MLN in coinfected mice. IFN-γ production was most likely caused by uptake of TLA by dendritic cells and subsequent IL-12 production. This mechanism has been observed following i.p. injection of mice with a TLA (similar to the preparation orally administered in our study), resulting in recruitment of dendritic cells to T-cell areas in the spleen and rapid IL-12 production (39). However, infection with T. gondii, suggesting parasite replication, represented a significantly stronger stimulus of Th1 responses than that with TLA. The stimulus provided by infection was strong enough to suppress developing Th2 responses and down-regulate established Th2 responses induced by helminth infection. Of interest is that the route of infection did not appear to influence the suppressive effects, since mice infected i.p. with T. gondii showed suppressive effects on Th2 responses induced by N. brasiliensis that were similar to those shown by mice infected orally. This suppressive capacity is remarkable, since other immunotherapies failed to show this effect. Finkelman et al. (17) reported the failure of recombinant IL-12 to modulate N. brasiliensis-induced Th2 responses, including serum IgE levels and mucosal mast cell and eosinophil numbers, when administered after but not during the initiation of the Th2 response. In contrast, CpG oligonucleotides have been reported to successfully reverse established Th2 responses to Th1 responses in murine models of allergic diseases (16).

Microorganisms and their products have been discussed as potential therapeutic agents for the treatment of Th1 (13, 44) or Th2 (4, 16, 29, 50) disorders. The results of the present study emphasize that the outcome of immunomodulatory strategies depends on the unique characteristics of the coinfecting organisms and other variables, including the sequence of infection, the dose and form of administration of the microorganisms (infection versus lysate injection), and the genetic background of the host. In this regard, we recently reported (15) that infection with N. brasiliensis did not interfere with elimination of Mycobacterium bovis BCG from the lung and the Th1 response induced by the latter infection. In these experiments, infection with M. bovis BCG did not down-regulate N. brasiliensis-induced Th2 responses. Thus, T. gondii appears to be a particularly strong Th2 suppressor.

Interestingly, coinfection studies involving T. gondii have been performed in the distant past, with a focus on the role of the activated macrophage and IFN-γ production (19, 28, 32, 40, 42, 48). In those studies, cross-protection by infection with T. gondii against unrelated organisms, including intracellular bacteria (42), viruses (40), fungi (19), protozoa (32), and helminths (including Trichinella [48] and Schistosoma [28]), was demonstrated. More recently, Santiago et al. (43) successfully used i.p. infection of BALB/c mice with T. gondii to convert a nonhealing-phenotype infection with Leishmania major into a healing-type infection dominated by Th1-type cytokine production.

In conclusion, the results of the present study demonstrate the failure of N. brasiliensis-induced Th2 responses to modulate T. gondii-induced Th1 responses, and, vice versa, T. gondii showed strong suppressive effects on both developing and established N. brasiliensis-induced Th2 responses. These findings contribute to our understanding of the regulation of immune responses during intestinal coinfections, which are especially frequent in children in developing countries (2). Since the immunopathogenesis of oral infection with 100 cysts of T. gondii resembles that which is operative in patients with Crohn's disease and murine models of inflammatory bowel disease (25), our findings may also contribute to the design of Th2-inducing protocols that will modulate Th1 disorders, including Crohn's disease.

Acknowledgments

We thank Andrea Maletz, Solvy Wolke, and Tobias Went for technical assistance and Ralf Ignatius for critical discussion.

This study was supported in part by grants from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (Lie 638/2-1 to O.L. and ER 363/1-1 to K.J.E.), the Charité Campus Benjamin Franklin (Forschungsschwerpunkt “Entzündliche Erkrankungen”) (to O.L.), and “Infektionsforschung”-Scholarships from the German Ministry of Research and Technology (BMFT) to O.L. and K.J.E.

Editor: S. H. E. Kaufmann

REFERENCES

- 1.Actor, J. K., M. Shirai, M. C. Kullberg, R. M. Buller, A. Sher, and J. A. Berzofsky. 1993. Helminth infection results in decreased virus-specific CD8+ cytotoxic T-cell and Th1 cytokine responses as well as delayed virus clearance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90:948-952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Agnew, D. G., A. A. Lima, R. D. Newman, T. Wuhib, R. D. Moore, R. L. Guerrant, and C. L. Sears. 1998. Cryptosporidiosis in northeastern Brazilian children: association with increased diarrhea morbidity. J. Infect. Dis. 177:754-760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Araujo, M. I., S. K. Bliss, Y. Suzuki, A. Alcaraz, E. Y. Denkers, and E. J. Pearce. 2001. Interleukin-12 promotes pathologic liver changes and death in mice coinfected with Schistosoma mansoni and Toxoplasma gondii. Infect. Immun. 69:1454-1462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bashir, M. E., P. Andersen, I. J. Fuss, H. N. Shi, and C. Nagler-Anderson. 2002. An enteric helminth infection protects against an allergic response to dietary antigen. J. Immunol. 169:3284-3292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bentwich, Z., A. Kalinkovich, Z. Weisman, G. Borkow, N. Beyers, and A. D. Beyers. 1999. Can eradication of helminthic infections change the face of AIDS and tuberculosis? Immunol. Today. 20:485-487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Candolfi, E., C. A. Hunter, and J. S. Remington. 1994. Mitogen- and antigen-specific proliferation of T cells in murine toxoplasmosis is inhibited by reactive nitrogen intermediates. Infect. Immun. 62:1995-2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chardes, T., D. Buzoni-Gatel, A. Lepage, F. Bernard, and D. Bout. 1994. Toxoplasma gondii oral infection induces specific cytotoxic CD8 alpha/beta+ Thy-1+ gut intraepithelial lymphocytes, lytic for parasite-infected enterocytes. J. Immunol. 153:4596-4603. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chardes, T., F. Velge-Roussel, P. Mevelec, M. N. Mevelec, D. Buzoni-Gatel, and D. Bout. 1993. Mucosal and systemic cellular immune responses induced by Toxoplasma gondii antigens in cyst orally infected mice. Immunology 78:421-429. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coffman, R. L., B. W. Seymour, S. Hudak, J. Jackson, and D. Rennick. 1989. Antibody to interleukin-5 inhibits helminth-induced eosinophilia in mice. Science 245:308-310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Conley, F. K., K. A. Jenkins, and J. S. Remington. 1981. Toxoplasma gondii infection of the central nervous system. Use of the peroxidase-antiperoxidase method to demonstrate toxoplasma in formalin fixed, paraffin embedded tissue sections. Hum. Pathol. 12:690-698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Denkers, E. Y., and R. T. Gazzinelli. 1998. Regulation and function of T-cell-mediated immunity during Toxoplasma gondii infection. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 11:569-588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Elliott, D. E., J. Li, A. Blum, A. Metwali, K. Qadir, J. F. Urban, Jr., and J. V. Weinstock. 2003. Exposure to schistosome eggs protects mice from TNBS-induced colitis. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 284:G385-G391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Elliott, D. E., J. J. Urban, C. K. Argo, and J. V. Weinstock. 2000. Does the failure to acquire helminthic parasites predispose to Crohn's disease? FASEB J. 14:1848-1855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Erb, K. J., J. W. Holloway, A. Sobeck, H. Moll, and G. Le Gros. 1998. Infection of mice with Mycobacterium bovis-Bacillus Calmette-Guerin (BCG) suppresses allergen-induced airway eosinophilia. J. Exp. Med. 187:561-569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Erb, K. J., C. Trujillo, M. Fugate, and H. Moll. 2002. Infection with the helminth Nippostrongylus brasiliensis does not interfere with efficient elimination of Mycobacterium bovis BCG from the lungs of mice. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 9:727-730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Erb, K. J., and G. Wohlleben. 2002. Novel vaccines protecting against the development of allergic disorders: a double-edged sword? Curr. Opin. Immunol. 14:633-643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Finkelman, F. D., K. B. Madden, A. W. Cheever, I. M. Katona, S. C. Morris, M. K. Gately, B. R. Hubbard, W. C. Gause, and J. F. Urban, Jr. 1994. Effects of interleukin 12 on immune responses and host protection in mice infected with intestinal nematode parasites. J. Exp. Med. 179:1563-1572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fox, J. G., P. Beck, C. A. Dangler, M. T. Whary, T. C. Wang, H. N. Shi, and C. Nagler-Anderson. 2000. Concurrent enteric helminth infection modulates inflammation and gastric immune responses and reduces helicobacter-induced gastric atrophy. Nat. Med. 6:536-542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gentry, L. O., and J. S. Remington. 1971. Resistance against Cryptococcus conferred by intracellular bacteria and protozoa. J. Infect. Dis. 123:22-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Khan, I. A., J. D. Schwartzman, T. Matsuura, and L. H. Kasper. 1997. A dichotomous role for nitric oxide during acute Toxoplasma gondii infection in mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:13955-13960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Khan, W. I., P. A. Blennerhasset, A. K. Varghese, S. K. Chowdhury, P. Omsted, Y. Deng, and S. M. Collins. 2002. Intestinal nematode infection ameliorates experimental colitis in mice. Infect. Immun. 70:5931-5937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kopf, M., F. Brombacher, P. D. Hodgkin, A. J. Ramsay, E. A. Milbourne, W. J. Dai, K. S. Ovington, C. A. Behm, G. Kohler, I. G. Young, and K. I. Matthaei. 1996. IL-5-deficient mice have a developmental defect in CD5+ B-1 cells and lack eosinophilia but have normal antibody and cytotoxic T cell responses. Immunity 4:15-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kopf, M., G. Le Gros, M. Bachmann, M. C. Lamers, H. Bluethmann, and G. Kohler. 1993. Disruption of the murine IL-4 gene blocks Th2 cytokine responses. Nature 362:245-248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liesenfeld, O. 1999. Immune responses to Toxoplasma gondii in the gut. Immunobiology 201:229-239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liesenfeld, O. 2002. Oral infection of C57BL/6 mice with Toxoplasma gondii: a new model of inflammatory bowel disease? J. Infect. Dis. 185(Suppl. 1):S96-S101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liesenfeld, O., H. Kang, D. Park, T. A. Nguyen, C. V. Parkhe, H. Watanabe, T. Abo, A. Sher, J. S. Remington, and Y. Suzuki. 1999. TNF-α, nitric oxide and IFN-y are all critical for development of necrosis in the small intestine and early mortality in genetically susceptible mice infected perorally with Toxoplasma gondii. Parasite Immunol. 21:365-376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liesenfeld, O., J. Kosek, J. S. Remington, and Y. Suzuki. 1996. Association of CD4+ T cell-dependent, interferon-gamma-mediated necrosis of the small intestine with genetic susceptibility of mice to peroral infection with Toxoplasma gondii. J. Exp. Med. 184:597-607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mahmoud, A. A., K. S. Warren, and G. T. Strickland. 1976. Acquired resistance to infection with Schistosoma mansoni induced by Toxoplasma gondii. Nature 263:56-57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Major, T., G. Wohlleben, B. Reibetanz, and K. J. Erb. 2002. Application of heat killed Mycobacterium bovis-BCG into the lung inhibits the development of allergen-induced Th2 responses. Vaccine 20:1532-1540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marshall, A. J., L. R. Brunet, Y. van Gessel, A. Alcaraz, S. K. Bliss, E. J. Pearce, and E. Y. Denkers. 1999. Toxoplasma gondii and Schistosoma mansoni synergize to promote hepatocyte dysfunction associated with high levels of plasma TNF-alpha and early death in C57BL/6 mice. J. Immunol. 163:2089-2097. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McKenzie, G. J., P. G. Fallon, C. L. Emson, R. K. Grencis, and A. N. McKenzie. 1999. Simultaneous disruption of interleukin (IL)-4 and IL-13 defines individual roles in T helper cell type 2-mediated responses. J. Exp Med. 189:1565-1572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mengs, U., and B. Pelster. 1982. The course of Plasmodium berghei infection in mice latently infected with Toxoplasma gondii. Experientia 38:570-571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mennechet, F. J., L. H. Kasper, N. Rachinel, W. Li, A. Vandewalle, and D. Buzoni-Gatel. 2002. Lamina propria CD4+ T lymphocytes synergize with murine intestinal epithelial cells to enhance proinflammatory response against an intracellular pathogen. J. Immunol. 168:2988-2996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mohrs, M., K. Shinkai, K. Mohrs, and R. M. Locksley. 2001. Analysis of type 2 immunity in vivo with a bicistronic IL-4 reporter. Immunity 15:303-311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nickdel, M. B., F. Roberts, F. Brombacher, J. Alexander, and C. W. Roberts. 2001. Counter-protective role for interleukin-5 during acute Toxoplasma gondii infection. Infect. Immun. 69:1044-1052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ogilvie, B. M., and D. J. Hockley. 1968. Effects of immunity of Nippostrongylus brasiliensis adult worms: reversible and irreversible changes in infectivity, reproduction, and morphology. J. Parasitol. 54:1073-1084. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Paterson, J. C., P. Garside, M. W. Kennedy, and C. E. Lawrence. 2002. Modulation of a heterologous immune response by the products of Ascaris suum. Infect. Immun. 70:6058-6067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pearce, E. J., and A. S. MacDonald. 2002. The immunobiology of schistosomiasis. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2:499-511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Reis e Sousa, C., S. Hieny, T. Scharton-Kersten, D. Jankovic, H. Charest, R. N. Germain, and A. Sher. 1997. In vivo microbial stimulation induces rapid CD40 ligand-independent production of interleukin 12 by dendritic cells and their redistribution to T cell areas. J. Exp. Med. 186:1819-1829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Remington, J. S., and T. C. Merigan. 1969. Resistance to virus challenge in mice infected with protozoa or bacteria. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 131:1184-1188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Roberts, C. W., D. J. Ferguson, H. Jebbari, A. Satoskar, H. Bluethmann, and J. Alexander. 1996. Different roles for interleukin-4 during the course of Toxoplasma gondii infection. Infect. Immun. 64:897-904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ruskin, J., and J. S. Remington. 1968. Immunity and intracellular infection: resistance to bacteria in mice infected with a protozoan. Science 160:72-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Santiago, H. C., M. A. Oliveira, E. A. Bambirra, A. M. Faria, L. C. Afonso, L. Q. Vieira, and R. T. Gazzinelli. 1999. Coinfection with Toxoplasma gondii inhibits antigen-specific Th2 immune responses, tissue inflammation, and parasitism in BALB/c mice infected with Leishmania major. Infect. Immun. 67:4939-4944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Summers, R. W., D. E. Elliott, K. Qadir, J. F. Urban, Jr., R. Thompson, and J. V. Weinstock. 2003. Trichuris suis seems to be safe and possibly effective in the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 98:2034-2041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Suzuki, Y., M. A. Orellana, S. Wong, F. K. Conley, and J. S. Remington. 1993. Susceptibility to chronic infection with Toxoplasma gondii does not correlate with susceptibility to acute infection in mice. Infect. Immun. 61:2284-2288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Urban, J. F., Jr., K. B. Madden, A. W. Cheever, P. P. Trotta, I. M. Katona, and F. D. Finkelman. 1993. IFN inhibits inflammatory responses and protective immunity in mice infected with the nematode parasite, Nippostrongylus brasiliensis. J. Immunol. 151:7086-7094. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Urban, J. F., Jr., N. Noben-Trauth, D. D. Donaldson, K. B. Madden, S. C. Morris, M. Collins, and F. D. Finkelman. 1998. IL-13, IL-4Ralpha, and Stat6 are required for the expulsion of the gastrointestinal nematode parasite Nippostrongylus brasiliensis. Immunity 8:255-264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wing, E. J., and J. S. Remington. 1978. Role for activated macrophages in resistance against Trichinella spiralis. Infect. Immun. 21:398-404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang, Y., and E. Y. Denkers. 1999. Protective role for interleukin-5 during chronic Toxoplasma gondii infection. Infect. Immun. 67:4383-4392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zuany-Amorim, C., E. Sawicka, C. Manlius, A. Le Moine, L. R. Brunet, D. M. Kemeny, G. Bowen, G. Rook, and C. Walker. 2002. Suppression of airway eosinophilia by killed Mycobacterium vaccae-induced allergen-specific regulatory T-cells. Nat. Med. 8:625-629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]