Abstract

Efficient attachment and ingestion of Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis by cultured epithelial cells requires the expression of a fibronectin (FN) attachment protein homologue (FAP-P) which mediates FN binding by M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis. Invasion of Peyer's patches by M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis occurs through M cells, which, unlike other intestinal epithelial cells, express integrins on their luminal faces. We sought to determine if the interaction between FAP-P of M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis and soluble FN enabled targeting and invasion of M cells by M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis in vivo via these surface integrins. Wild-type and antisense FAP-P mutant M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis strains were injected alone or coinjected with blocking peptides or antibodies into murine gut loops, and immunofluorescence microscopy was performed to assess targeting and invasion of M cells by M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis. Nonopsonized M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis preferentially invaded M cells in murine gut loops. M-cell invasion was enhanced 2.6-fold when M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis was pretreated with FN. Invasion of M cells by the antisense FAP-P mutant of M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis was reduced by 77 to 90% relative to that observed for the control strains. Peptides corresponding to the RGD and synergy site integrin recognition regions of FN blocked M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis invasion of M cells by 75 and 45%, respectively, whereas the connecting segment 1 peptide was noninhibitory. Antibodies against the α5, αV, β1, and β3 integrin subunits inhibited M-cell invasion by 52 to 73%. The results indicate that targeting and invasion of M cells by M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis in vivo is mediated primarily by the formation of an FN bridge formed between FAP-P of M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis and integrins on M cells.

Paratuberculosis is a chronic granulomatous enteritis of domestic and wild ruminants that is caused by Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis, a slow-growing intracellular acid-fast bacillus. Animals are usually infected within the first few months of life; however, the chronic wasting and profuse diarrhea that characterize clinical paratuberculosis are usually not observed until 3 or more years after infection (4, 7).

M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis enters intestinal tissue through M cells present in the dome epithelium covering the continuous Peyer's patches in the distal ileum of calves and goats (22, 32). The discrete Peyer's patches in the intestinal tracts of other mammals and the jejunum of ruminants are secondary lymphoid organs, in which an adaptive immune response can be initiated following exposure to foreign antigens. In contrast, the continuous Peyer's patch in the ruminant ileum is a primary lymphoid organ, wherein B-cell development occurs (36).

Fibronectin attachment proteins (FAPs) are a family of fibronectin (FN)-binding proteins present in several species of mycobacteria (25, 28-30, 42). Attachment and internalization of Mycobacterium bovis BCG, M. leprae, and M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis by epithelial cells in vitro have been shown to be dependent on the interaction between FAP and FN (18, 29, 31). β1 integrins have been identified as the host cell receptor for FN-opsonized mycobacteria in vitro (3, 18). M cells are unique among cells of the intestinal epithelium in that they display β1 integrins on their luminal faces at high density (6). Thus, the interaction between cell surface integrins and FN bound by organisms may explain why M cells are the portals of entry for M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis. However, adherence and internalization assays with macrophages, monocytes, and epithelial cell lines give only a general picture of the adhesive and invasive potential of mycobacteria. The nature and density of potential host cell receptors vary for each culture system to such an extent that the significance of host-pathogen interactions observed in vitro must be interpreted with caution. Moreover, the distribution of receptors on cells in culture is often markedly different from that on cells in intact tissue, particularly for intestinal epithelial cells (8, 15, 37). Thus, it is imperative that putative adhesins and invasins be evaluated in in vivo model systems before any degree of significance can accurately be attributed to their expression.

The expression of FAP was found to be important for attachment of M. avium subsp. avium to respiratory explants and attachment of M. bovis BCG to murine bladder mucosa in vivo (20, 41). However, demonstration of FAP-mediated mycobacterial attachment required exposure of the extracellular matrix. This mechanism is insufficient to explain M-cell targeting by M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis. Thus, the contribution of the FAP of M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis (FAP-P) to the invasive potential of M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis for intestinal tissue in vivo remains uncertain. The purpose of the present study was to determine whether the interaction of FAP-P with soluble FN is required for selective targeting and invasion of murine intestinal M cells in vivo by M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis. We observed that M cells were selectively invaded by M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis and that this effect was enhanced when the organism was opsonized with FN. Attenuation of FAP-P expression effectively eliminated the selective invasion of M cells by M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis. Similarly, blocking of the interaction between FN and host cell integrins with FN peptides or anti-integrin antibodies abolished M-cell targeting. However, in vivo invasion of villous epithelial cells by M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis occurred by an FN-independent mechanism.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis strain 5781 was propagated in Middlebrook 7H9 broth (Becton Dickinson, Cockeysville, Md.) supplemented with 10% oleic acid-albumin-dextrose-catalase (Becton Dickinson), 0.05% Tween 80 (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.), and 2 μg of mycobactin J (Allied Monitor, Fayetteville, Mo.) per ml in tissue culture flasks. M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis strains 5781/26A, 5781/28F, 5781/28H, and 5781/W4C were propagated in Middlebrook 7H9 broth supplemented as above plus 50 μg of kanamycin sulfate (Fisher, Pittsburgh, Pa.) per ml in tissue culture flasks. The bacterial strains used in this investigation are described in Table 1. Bacterial cultures used in each experiment were prepared from low-passage freezer stocks and grown to mid- to late logarithmic phase.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains used in this investigationa

| Strain | Plasmid | Description | FAP-P expression (% of control) | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5781 | None | Wild type | 100 | 30 |

| 5781/W4C (control) | pWES4 | Vector control strain, expresses green fluorescent protein | 100 | 23, 31 |

| 5781/26A | pTS026 | Antisense FAP-P expression cassette 1 | 90 | 31 |

| 5781/28F | pTS028 | Antisense FAP-P expression cassette 2, genomic copy of FAP-P contains point mutations at positions 678 and 1092 of the coding sequence | 70 | 31 |

| 5781/28H | pTS028 | Antisense FAP-P expression cassette 2 | 70 | 31 |

Plasmids used to create the vector control and antisense FAP-P mutant strains were prepared from the mycobacterial shuttle vector pMV261 (35).

Antibodies, lectin, and peptides.

Rabbit anti-M. bovis BCG immunoglobulin G (IgG) (anti-BCG IgG) was obtained from Dako (Carpinteria, Calif.). Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG and Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated rabbit anti-goat IgG were acquired from Molecular Probes (Eugene, Oreg.). Hamster IgG and rat IgG were supplied by Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories (West Grove, Pa.). Hamster anti-mouse αV integrin (clone H9.2B8), hamster anti-mouse β1 integrin (clone HMβ1-1), hamster anti-mouse β3 integrin (clone 2C9.G2), and rat anti-mouse α5 integrin (clone 5H10-27) monoclonal antibodies were obtained from BD Pharmingen (San Diego, Calif.). Goat anti-human α5β1 integrin antiserum, rabbit anti-bovine FN antiserum, rabbit anti-human αV integrin antiserum (multispecies cross-reactivity), and goat IgG were obtained from Chemicon (Temecula, Calif.). Rabbit IgG was purified from normal rabbit serum by protein A-agarose chromatography (Pierce, Rockford, Ill.). Tetramethyl rhodamine isothiocyanate (TRITC)-conjugated Ulex europaeus lectin (UEA-1), which is a specific marker for M cells (6), was purchased from Sigma. RGD (GRGDSP) and RGD control (GRADSP) peptides were obtained from Calbiochem (San Diego, Calif.). Connecting segment (CS)-1 peptide (EILDV) was purchased from Bachem (King of Prussia, Pa.). Synergy site (DRVPPSRNSIT), synergy site control (VPPDRNTISRS), and CS-1 control (EILAV) peptides were synthesized with fluorenylmethoxycarbonyl chemistry and purified by high-pressure liquid chromatography (Sigma-Genosys, The Woodlands, Tex.). Peptides were dissolved in ANT buffer (10 mM ammonium acetate, 0.85% sodium chloride, 0.05% Tween 20, pH 6) or ANT buffer (pH 6) containing 10% dimethyl sulfoxide (CS-1 and CS-1 control peptides) to a final concentration of 5 mM.

Preparation of bacterial inoculum.

M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis cultures were centrifuged for 15 min at 1,600 × g. Bacterial pellets were resuspended by vigorous pipetting and vortexing in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 0.05% Tween 20 (PBST) (Sigma) in a volume sufficient to yield 2 × 108 CFU/ml. For the first experiment, three 10-ml aliquots of bacterial suspension were centrifuged as above, and the pellets were resuspended in 10 ml of ANT buffer (pH 3). After incubation for 5 min at room temperature, the suspensions were centrifuged as before. Two pellets were each resuspended in 10 ml of ANT (pH 6). Twenty micrograms of bovine FN (Biomedical Technologies, Stoughton, Mass.) was added to one of these tubes (2 μg of FN/ml of buffer). The remaining pellet was resuspended in 10 ml of ANT (pH 6) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). After incubation for 1 h at 37°C, the bacterial suspensions were centrifuged as before to separate M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis from unbound opsonins. Each pellet was resuspended in 1 ml of ANT (pH 6) containing 0.04% trypan blue (Sigma) and kept on ice until inoculation into murine gut loops. For subsequent experiments, a single suspension of each bacterial strain used was prepared and treated with bovine FN as described above.

Gut loop assay.

Six- to 8-week-old BALB/c mice (Harlan, Indianapolis, Ind.) were held at the Purdue Veterinary Animal Housing Facility for 3 to 4 days before use. Feed was withdrawn for 4 h, after which mice were anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital at a dose of 50 to 67 mg/kg. The small intestine and cecum were exposed from the abdomens of anesthetized mice, and ligations were made at the ileocecal junction and 4 to 5 cm proximal to the ileocecal junction for each mouse. Each ligated loop contained at least one Peyer's patch. Fifty microliters of M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis (108 CFU) was injected into the ligated segment. For peptide blocking experiments, 250 nmol of peptide was coinjected with 108 CFU of M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis in a total volume of 100 μl. For antibody blocking experiments, 50 μg of antibody was coinjected with 108 CFU of M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis in a total volume of 100 μl. Exposed intestinal tissue was replaced in the abdominal cavity after injection. After 2 h, gut loops were excised and frozen, and mice were euthanized. This procedure was reviewed for compliance with federal and university guidelines and approved by the Purdue Animal Care and Use Committee prior to the initiation of animal studies.

Double immunofluorescence assay.

Frozen intestinal segments were mounted in cryoembedding resin (Triangle Biomedical Supply, Durham, N.C.). Cross sections (6 to 8 μm thick) were cut through Peyer's patches at 30- to 40-μm intervals with a Minotome Plus cryostat (Triangle Biomedical Supply). Unstained tissue sections were examined for integrity by microscopic examination for trypan blue exclusion. After fixation for 10 min in acetone, sections were blocked for 30 min in PBST with 5% bovine serum albumin (PBSTB). Mycobacteria in frozen tissue sections were labeled for 30 min with rabbit anti-M. bovis BCG IgG diluted 1:100 in PBSTB, followed by Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG. M cells were labeled with 5 mg of TRITC-UEA-1 per ml of PBSTB for 30 min.

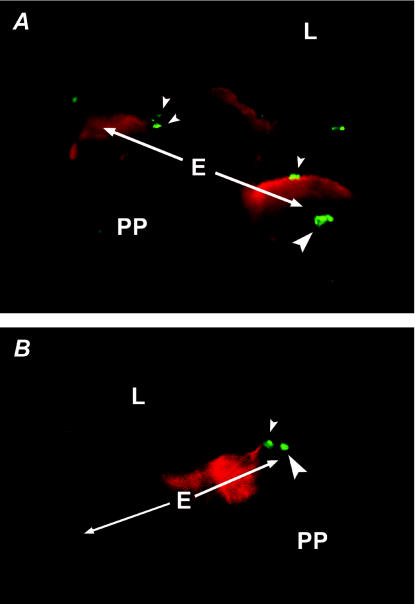

Fluorescence microscopy was used to examine the follicle-associated epithelium and subepithelial layer of three to five ileal Peyer's patch sections from each of at least five mice per treatment, and the number of infected cells was recorded. For a cell to be scored as infected, M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis had to be in the same focal plane as the cytoplasm of cells at 1,000× magnification. Infected cells were grouped as M cells (intense red apical staining) or villous epithelial (VE) cells (Fig. 1). If infected cells in the subepithelial layer were observed immediately beneath uninfected M cells, these were included as infected M cells. Infected subepithelial cells found below uninfected VE cells were scored as infected VE cells.

FIG. 1.

M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis attaches to and invades cells of the follicle-associated epithelium in the murine ileum. Bacteria were stained with a rabbit anti-M. bovis BCG primary antibody and FITC-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody. M cells were labeled with UAE-1 conjugated to TRITC, which binds to carbohydrate residues on the M-cell surface. Images of ileal dome epithelia in panels A and B were captured separately with filters for FITC and TRITC and then combined. The dome epithelium (E) in the focal planes of both panels is indicated by the arrows. PP, Peyer's patch; L, intestinal lumen. (A) Adherence to and invasion of M cells by M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis. Organisms are attached to M cells on the left and right (small arrowheads). Several organisms have been ingested by the M cell on the right (large arrowhead). The M cell in the center of this image lies below the plane of focus. (B) Binding and ingestion of M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis by VE cells. A bacterium is shown attached to the apical membrane of a VE cell immediately to the right of an M cell (small arrowhead), and another organism has been internalized by the adjacent VE cell (large arrowhead). Magnification, ×1,650.

Demonstration of FN opsonization in situ.

Cross sections of gut loops injected with M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis treated with buffer only, 10% FBS, or FN were fixed in acetone for 10 min. After blocking the tissue sections as described above, sections were treated with rabbit anti-bovine FN antiserum, rabbit anti-M. bovis BCG IgG, or normal rabbit serum IgG (diluted 1:20, 1:100, and 1:100, respectively, in PBSTB), and stained with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG. The relative number of green-fluorescent M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis in the lumens of anti-FN-treated sections was compared with that in anti-M. bovis BCG-treated sections for each experimental group.

Detection of αV integrin subunits on M cells.

Cross sections through Peyer's patches of murine gut loops were fixed in acetone and blocked as described above. Sections were treated with 1:50 dilutions (in PBSTB) of rabbit anti-αV integrin antiserum or normal rabbit serum IgG for 30 min, followed by Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG. M cells were labeled with TRITC-UEA-1 as described above. Sections were examined at 1,000× magnification for colocalization of red and green fluorochromes on the apical faces of cells of the follicle-associated epithelium.

Integrin colocalization.

HEp-2 cells were propagated in minimal essential medium with Earle's salts, l-glutamine, and nonessential amino acids (MEM) (Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, Md.) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and antibiotic-antimycotic solution (Life Technologies). Cells (5 × 104) were seeded into each well of eight-well chamber slides (Lab-Tek II, Nunc, Napierville, Ill.). Chamber slides were incubated for 20 h at 37°C in 5% CO2. It was assumed that one round of cell division occurred during this period (12). Cultures of M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis strains 5781 and 5781/28H were centrifuged for 15 min at 1,600 × g, and the bacterial pellets were resuspended in PBST to a density equivalent to 2 × 108 CFU/ml. Four milliliters of each bacterial suspension was centrifuged as above, and the pellets were resuspended in 4 ml of ANT buffer (pH 3). After incubation for 5 min at room temperature, the suspensions were centrifuged as before. The pellet was resuspended in 4 ml of ANT (pH 6) and incubated with FN (2 μg/ml) for 1 h at 37°C. The suspensions were centrifuged as before, and each pellet was resuspended in 4 ml of MEM without serum or antibiotics (basal medium).

HEp-2 slide cultures were washed twice with warm PBS, infected with either strain 5781 or strain 5781/28H at a ratio of 400 organisms/cell, and incubated at room temperature. Separate cultures were incubated with goat anti-human α5β1 integrin antiserum diluted 1:100 in basal medium (integrin clustering positive control) or goat IgG (antibody negative control). At 5, 60, or 120 min postinfection, cultures were washed twice with PBS and fixed overnight in neutral buffered formalin. After blocking in PBSTB, fixed cultures were labeled with goat anti-human α5β1 integrin antiserum diluted 1:100 in PBSTB. Immunoreactive integrins were stained with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated rabbit anti-goat IgG diluted 1:100 in PBSTB. Bacteria and cell nuclei were stained with propidium iodide (4 μg/ml in PBS).

Fluorescence images were captured with an MRC 1024 confocal laser scanning microscope system (Bio-Rad Hercules, Calif.) equipped with a Nikon Diaphot 300 inverted microscope (Melville, N.Y.), an argon-krypton laser (Ion Laser Technology, Salt Lake City, Utah), and LaserSharp software (Bio-Rad). Specimens were examined with a Plan-APO 60X/1.4n.a. differential interference contrast oil immersion objective. Multiple focal planes were examined with 3.1-fold zoom enhancement to verify that the bacteria in the fields examined were on the surface of cells. Integrin clustering intensity was measured in captured confocal images with Optimas version 6.1 software (Media Cybernetics, Silver Spring, Md.). The number of yellow and green pixels (hue values of 47 to 79 on a scale of 1 to 255) with a minimum intensity value of 95 (scale of 1 to 255; maximum saturation) were counted in a 64-pixel area centered on bacteria attached to HEp-2 cells at 2 h postinfection. Thirty-five areas were measured for each treatment.

Statistical analysis.

Treatment groups were compared by one-way analysis of variance and Tukey's multiple comparison test. Comparisons between cell types within a treatment group and α5β1 integrin clustering intensities in HEp-2 cells infected with M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis strain 5781 or 5781/28H were performed with Student's t test.

RESULTS

Effect of FN on invasion of M cells.

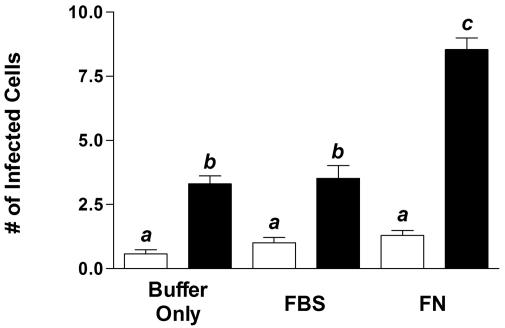

To assess the contribution of FN to the invasion of intestinal epithelial cells by M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis, nonopsonized, serum-opsonized, and FN-opsonized M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis strain 5781 cells were injected into murine gut loops. M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis preferentially invaded M cells over VE cells in the follicle-associated epithelium, regardless of treatment (Fig. 2). This indicates that the murine gut loop model may be suitable for the early events in the pathogenesis of Johne's disease. Pretreatment of M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis with 10% FBS had no effect on the invasion of either cell type by M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis relative to that observed for nonopsonized M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis. However, injection of FN-opsonized M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis resulted in a 2.6-fold increase in the number of M cells invaded. Although FN-opsonized M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis invaded VE cells more often than did nonopsonized M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis, this observation was not statistically significant (P > 0.05). Large numbers of bacteria labeled with anti-FN antibodies were seen in the lumens of gut loops injected with FN-treated M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis, whereas anti-FN-reactive bacteria were only infrequently observed in gut loops injected with buffer- or serum-treated M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis (data not shown). These results demonstrate that FN selectively enhances the ability of M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis to invade M cells. Fibronectin-opsonized M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis cells were used in all subsequent experiments.

FIG. 2.

FN opsonization enhances internalization of M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis by M cells but not VE cells. M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis was treated with pH 6 buffer only, buffer containing 10% FBS, or buffer containing 2 μg of FN/ml for 1 h prior to injection into murine gut loops. Bacteria within cryosectioned tissues were stained with rabbit anti-M. bovis BCG IgG followed by Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG. M cells were labeled with TRITC-conjugated UEA-1. The number of M cells (solid bars) and non-M VE cells (open bars) containing M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis were enumerated by fluorescence microscopy. Tissue sections from five or six mice were examined for each treatment group. Treatment groups were compared by one-way analysis of variance and Tukey's multiple-comparison test. Groups with different letters were significantly different from each other at P < 0.05.

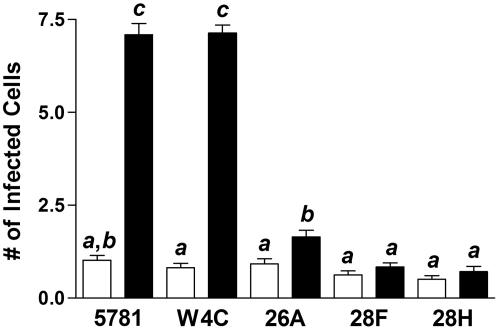

Intestinal epithelial cell invasion by antisense FAP-P mutants.

In a previous investigation, antisense FAP-P mutants were observed to have a significantly diminished capacity to adhere to and invade intestinal epithelial cells in vitro (31). These mutants were treated with FN and injected into murine gut loops in order to determine whether FAP-P was necessary for M-cell targeting in vivo. Disruption of FAP-P expression in M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis strains 5781/26A, 5781/28F, and 5781/28H significantly impaired the ability of these strains to invade M cells but had little effect on invasion of VE cells relative to that observed for the parent wild-type (5781) and vector control (5781/W4C) strains (Fig. 3). Strain 5781/26A invaded M cells more frequently than VE cells (P = 0.002). However, no significant difference in cell type invasion was evident for strains 5781/28F and 5781/28H (P = 0.17 and 0.25, respectively). Overall, M-cell invasion by antisense FAP-P mutant M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis was reduced by 77 to 90% relative to that of the vector control strain. These data show that FAP-P mediates M-cell targeting in vivo.

FIG. 3.

FAP of M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis (FAP-P) is required for M-cell invasion. M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis 5781 parent strain (wild type), M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis 5781, containing an expression vector (vector control), and three M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis strains with expression vectors containing antisense FAP-P cassettes (5781/26A, 5781/28F, and 5781/28H) were treated in buffer containing 2 μg of FN/ml for 1 h prior to inoculation into murine gut loops. The numbers of M cells (solid bars) and non-M VE cells (open bars) containing M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis were enumerated by fluorescence microscopy. Tissue sections from 9 or 10 mice were examined for each bacterial strain used. Treatment groups were compared by one-way analysis of variance and Tukey's multiple-comparison test. Groups with different letters were significantly different from each other at P < 0.05.

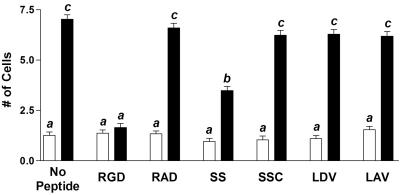

Peptide blocking of M-cell invasion.

To demonstrate that M cells interact specifically with FN to engulf FN-opsonized M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis, peptides corresponding to the integrin recognition motifs of FN (13, 26) were coinjected with FN-opsonized organisms. RGD and SS peptides interfered with the invasion of M cells by FN-opsonized M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis (Fig. 4). Neither of these peptides affected VE cell invasion. M cells and VE cells ingested M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis with similar frequencies in the presence of RGD (P = 0.28). The LDV peptide had no effect on the invasion of either epithelial cell category. M-cell invasion was inhibited by 75 and 44% in the presence of the RGD and SS peptides, respectively. These observations indicated that specific recognition and binding of FN by M-cell surface receptors, most probably integrins, was necessary for M-cell targeting and invasion by M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis.

FIG. 4.

Peptides corresponding to the RGD and synergy site domains of FN block binding of FN-opsonized M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis to M cells. M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis was treated with buffer containing 2 μg of FN/ml for 1 h prior to inoculation. RGD, synergy site (SS), and CS-1 (LDV) peptides were coinjected with M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis into murine gut loops. Control peptides for RGD, SS, and LDV (RAD, SSC, and LAV, respectively) were separately coinjected with M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis. The numbers of M cells (solid bars) and non-M VE cells (open bars) containing M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis were enumerated by fluorescence microscopy. Tissue sections from six or seven mice were examined for each peptide used. Treatment groups were compared by one-way analysis of variance and Tukey's multiple-comparison test. Groups with different letters were significantly different from each other at P < 0.05.

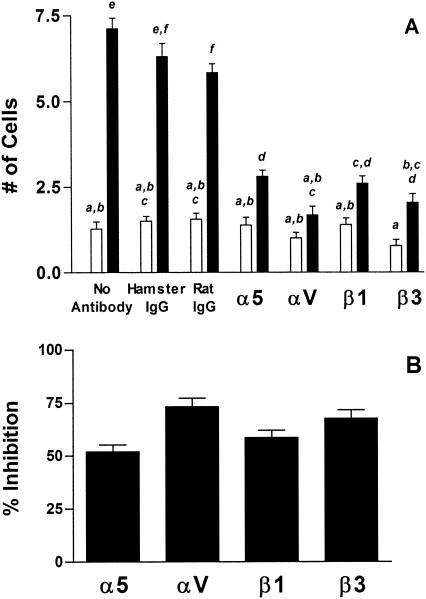

Antibody blocking of M-cell invasion.

The fact that both the RGD and SS peptides inhibited M-cell invasion of M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis suggested that α5β1 integrin, the classic FN receptor (38), was responsible for M-cell recognition by FN-opsonized M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis. However, because the RGD peptide was more inhibitory than the SS peptide, it was suspected that more than one integrin type might be mediating the binding and ingestion of M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis by M cells. To identify the M-cell surface integrins that participated in the binding and ingestion of FN-opsonized M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis, function-blocking monoclonal antibodies against α5, αV, β1, and β3 integrin subunits were coinjected with FN-opsonized M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis strain 5781. All four monoclonal antibodies inhibited the invasion of M cells by FN-opsonized M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis but did not affect ingestion of this organism by VE cells (Fig. 5A). Antibodies to the α5, αV, β1, and β3 integrin subunits inhibited M-cell invasion by 52, 73, 58, and 67%, respectively (Fig. 5B). These results confirmed the participation of α5β1 integrin in the selective invasion of M cells by M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis targeted and also implied the involvement of αVβ3 integrin in this process. This conclusion was supported by the observation of weak but specific binding of anti-αV antibodies to the apical surfaces of M cells by fluorescence microscopy (Fig. 6).

FIG. 5.

Invasion of M cells by M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis is blocked by monoclonal antibodies to the α5, αV, β1, and β3 integrin subunits. M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis was treated with buffer containing 2 μg of FN/ml for 1 h prior to inoculation. Buffer, hamster anti-mouse α5 integrin, hamster anti-mouse αV integrin, hamster anti-mouse β1 integrin, hamster anti-mouse β3 integrin, hamster IgG, or rat IgG1 was coinjected with M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis into murine gut loops. (A) Comparative invasion frequency. The numbers of M cells (solid bars) and non-M VE cells (open bars) containing M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis were enumerated by fluorescence microscopy. Tissue sections from six mice were examined for each peptide used. Treatment groups were compared by one-way analysis of variance and Tukey's multiple-comparison test. Groups with different letters were significantly different from each other at P < 0.05. (B) Percent inhibition of M-cell invasion. The proportionate reduction in M-cell invasion in the presence of blocking antibodies was determined by dividing the number of M cells ingesting M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis in each section for each antibody by the mean M-cell invasion frequency of M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis in the presence of the respective antibody control.

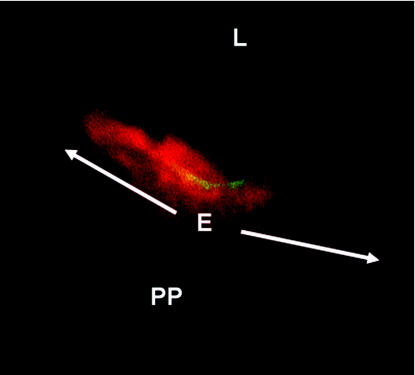

FIG. 6.

αV integrins are expressed on the apical faces of M cells in the murine ileum. Cross-sections of mouse ileal Peyer's patches were incubated with rabbit anti-αV integrin antiserum followed by FITC-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG. M cells were labeled with UEA-1 conjugated to TRITC, which binds to carbohydrate residues on the M-cell surface. A single M cell is present in this figure, flanked by two (nonfluorescing) villous epithelial cells. Images were captured separately with filters for FITC and TRITC and then combined. The dome epithelium (E) in this focal plane is indicated by the arrows. PP, Peyer's patch; L, intestinal lumen. Magnification, ×1,650.

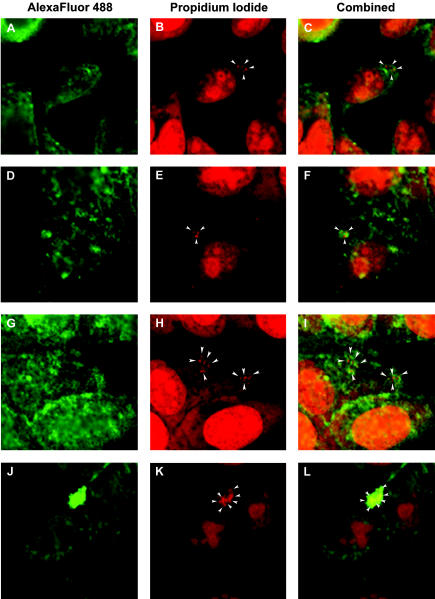

Effect of attenuated FAP-P expression on integrin colocalization.

Because the level of attenuation of FAP-P synthesis by the antisense FAP-P mutants used in this study was relatively modest (31), it was postulated that the abolition of M-cell invasion observed for these mutants could be explained by the impaired ability of these mutants to promote integrin clustering, a requisite condition for integrin-mediated bacterial ingestion (10, 14). To investigate this possibility, M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis strains 5781 and 5781/28H were treated with FN and used to infect HEp-2 cells. Confocal laser scanning microscopy was used to examine infected cells for colocalization of α5β1 integrin with bacteria attached to the cell surface. Very few cells were observed to have attached bacteria at 5 min postinfection regardless of the bacterial strain used. No colocalization of integrins with bacteria was observed at this time, and no clustering was observed in positive control cultures (data not shown).

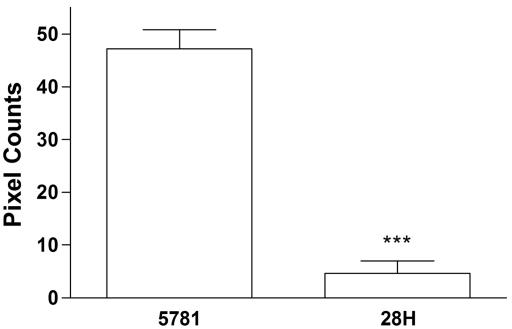

At 1 h postinfection, attached strain 5781/28H bacteria were seen to be very weakly associated with α5β1 integrin on the surface of HEp-2 cells (Fig. 7A to C). Colocalization of cell surface integrins with this strain increased slightly at 2 h postinfection (Fig. 7G to I). In contrast, strong colocalization of α5β1 integrins with M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis strain 5781 attached to HEp-2 cells was noted at 1 h postinfection (Fig. 7D to F), and cell surface integrin colocalization with attached M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis strain 5781 increased markedly by 2 h postinfection. (Fig. 7J to L). The intensity of HEp-2 integrin colocalization with strain 5781/28H bacteria attached to HEp-2 cells was 10-fold lower than that observed with strain 5781 organisms (Fig. 8). These observations demonstrate that M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis antisense FAP-P mutants are deficient in their ability to colocalize with α5β1 integrin, which may account for their significantly diminished capacity to invade M cells.

FIG. 7.

Attenuated expression of the FN attachment protein of M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis (FAP-P) results in diminished integrin colocalization with M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis in infected cells. M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis strain 5781/28H (A to C and G to I) or strain 5781 (D to F and J to L) was treated with FN (2 μg/ml) for 1 h and used to infect HEp-2 cells at a ratio of 400 organisms/cell. Cultures were fixed at 1 h (A to F) or 2 h (G to L) postinfection. Fixed cultures were labeled with goat anti-human α5β1 integrin and stained with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated rabbit anti-goat IgG. Bacteria (arrowheads) were stained with propidium iodide, which also stained cell nuclei. Images were captured by confocal laser scanning microscopy. Magnification, ×690.

FIG. 8.

α5β1 integrin colocalization intensity is affected by the level of FN attachment protein expressed by M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis. ΗΞp-2 cells infected with FN-treated M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis strain 5781 or 5781/28H at a ratio of 400 organisms/cell were fixed at 2 h postinfection. Cells were treated with goat anti-human α5β1 integrin and stained with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated rabbit anti-goat IgG. Bacteria were labeled with propidium iodide. Yellow and green pixels with intensities equal to or greater than 95 (on a scale of 1 to 255) in images captured by confocal laser scanning microscopy were counted in a 64-pixel region centered on bacteria bound to the surface of HEp-2 cells. Thirty-five regions were counted for each bacterial strain. ***, P < 0.0001.

DISCUSSION

We report herein that M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis invades murine intestinal tissue primarily through M cells. The predilection of M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis for M cells is governed primarily by an FN-dependent mechanism that involves the binding of FN by FAP-P expressed on M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis and by integrins present on the lumenal surface of M cells. Disruption of FN binding, either by M cells or by M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis, abolishes M-cell targeting and markedly diminishes the invasive potential of the organism.

Ruminant gut loop models have been used to identify the portal of entry used by M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis to invade intestinal tissue. These systems are not practical for mechanistic studies in which numerous inhibitors or mutant bacterial strains must be evaluated. The observation that M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis primarily invades M cells in the murine ileum is consistent with those obtained for M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis in ruminant gut loop systems (22, 32). This illustrates that the murine gut loop model may be a useful system in which to study the host-pathogen interactions that occur very early in the pathogenesis of paratuberculosis. Others have found that M. avium subsp. avium primarily invades VE cells in a murine gut loop system (27). Thus, the tropism of these two very closely related organisms (11) for different intestinal epithelial cell types reiterates the inherent differences in pathobiology between M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis and M. avium subsp. avium. The basis for the observed differences is not immediately clear and certainly merits further investigation.

FN present in the intestinal lumen is suspected to have mediated the preferential invasion of M cells seen with nonopsonized M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis. Had preferential targeting of M cells involved a significant FN-independent component, disruption of FN binding (either by the organism or by M cells) would not have prevented selective invasion. However, antisense FAP-P mutant strains 5781/28F and 5781/28H did not exhibit a preference for M-cell invasion. Similarly, the RGD peptide effectively obliterated M-cell targeting.

The concentration of FN in commercial lots of FBS has been estimated to be approximately 50 μg/ml (34). It was therefore surprising that treatment of M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis with 10% FBS under conditions that favor soluble FN binding (30) had no effect on M-cell invasion. It is possible that other serum opsonins may have sterically prevented the interaction between M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis and FN or M-cell receptors. Alternatively, FN in serum may have been organized into higher-order structures (i.e., other than soluble dimeric FN) and thereby limited the ability of M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis to interact with FN or integrins in a manner that would result in bacterial ingestion under the experimental conditions used. No qualitative differences were observed between FBS-treated and FN-treated M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis cells with respect to association of the organisms with the apical membranes of M cells. However, in most cases it was not possible to distinguish the random apposition of bacteria with host cell membranes from specific attachment.

Ingestion of FN-opsonized M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis by VE cells was slightly higher than that seen for nonopsonized M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis. This may have resulted from the exposure of lateral integrins on these cells as a consequence of the hydrostatic pressure exerted by the inoculum. This possibility is supported by the observation that VE cell invasion by strains 5781/28F and 5781/28H was less frequent than that by the control strains, although this difference was not significant. Nevertheless, VE cell invasion was fairly constant regardless of experimental treatment. This suggests that invasion of VE cells occurs by a nonopsonic mechanism. In addition, because disruption of FN binding failed to completely eliminate M-cell invasion by M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis, it is apparent that M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis can invade M cells in a manner that is independent of FN. Considering that the frequency of M-cell invasion by M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis in the presence of FN binding inhibitors was similar to that of VE cells, it is reasonable to postulate that this organism uses the same mechanism for nonselective invasion of intestinal epithelial cells. Recent evidence has implicated the product of the mce1 gene of M. tuberculosis as a nonopsonic invasin (5). An mce homologue has been identified in M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis (J. M O'Mahony and C. J. Hill, GenBank accession no. AY074798). The involvement of the M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis mce homologue in VE cell invasion presents an attractive hypothesis. Nevertheless it remains to be proven that this protein is a functional homologue of mce1.

The diminished capacity of antisense FAP-P mutants to invade murine M cells corresponded to the level of FAP-P expressed by these mutants (10, 30, and 30% reductions in FAP-P expression for strains 5781/26A, 5781/28F, and 5781/28H, respectively) (31). With the exception of reduced FAP-P secretion by antisense FAP-P mutants, no salient differences between the secreted protein profiles of antisense FAP-P mutants and the parent wild-type M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis have been observed (our unpublished observations). However, the relatively modest attenuation of FAP-P expression by antisense FAP-P mutants had profound consequences for the invasive potential of these strains. These mutants exhibited a similar, disproportionately large reduction in invasive capacity when used to infect epithelial cells in vitro in an earlier investigation (31). Because the extent of integrin clustering elicited in vitro by strain 5781/28H was clearly inferior to that observed for the parent strain, it appears that the degree of integrin clustering promoted by FN-opsonized M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis determines the likelihood of ingestion of the organism by M cells. Because the antisense FAP-P mutants are somewhat limited in their ability to bind FN, this automatically restricts the number of integrins that can be captured and confined in a single focus on the M-cell surface.

The requirement for α5β1 integrin to engage the synergy site of FN in order for high-affinity binding of FN via the RGD motif to occur is not absolute and depends on the activation state of this integrin (9). A proportion of the α5β1 integrin population on the apical membranes of M cells may be intrinsically active or might be activated independently of synergy site ligation via inside-out signaling initiated by the engagement of other receptors (16). This could account for the differential inhibition of the RGD and SS peptides. Still, the fact that monoclonal antibodies to the αV and β3 integrin subunits strongly inhibited the ingestion of M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis indicates that integrins other than α5β1 may also play a role in the internalization of FN-opsonized M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis by M cells.

αVβ3 integrin has been detected on the mucosal surface of cells in the small intestine of dogs, pigs, and cattle (33). The results of this investigation extend these findings to include the apical membrane of M cells in murine ileal Peyer's patches. Transfection of α5β1 integrin-expressing K562 cells with αVβ3 integrin enhanced the ability of these cells to ingest FN-coated latex beads. However, treatment of transfected K562 cells with vitronectin or antibodies to αVβ3 integrin blocked α5β1 integrin-mediated phagocytosis and migration without affecting the anchoring function of the latter integrin (1). It was subsequently demonstrated that antibody ligation of αVβ3 integrin interferes with α5β1 integrin-mediated phagocytosis of FN-coated latex beads by suppressing α5β1 integrin-dependent activation of calcium- and calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (2). This may explain the increased inhibitory effects observed for anti-αV and anti-β3 monoclonal antibodies in vivo in comparison with those of monoclonal antibodies against α5 and β1 integrin subunits in the present study.

The possibility that other integrins may bind FN-opsonized M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis cannot be excluded, as the α3β1 and αVβ1 integrins also bind FN via the RGD motif (39). Although αIIbβ3 also binds FN via the RGD and SS motifs, the participation of this integrin was not considered because its expression is restricted to platelets (38). The involvement of integrins that recognize the CS-1 domain of FN, such as α4β1, was discounted because M-cell invasion was not inhibited by the CS-1 peptide. This observation was not unexpected, in view of the fact that the heparin binding site of FN, which is recognized by FAP (25, 42), overlaps the CS-1 domain (39).

Although others have reported the presence of FN in the murine intestine (17), anti-FN immunoreactivity was observed on only a very few organisms in the ileal lumens of mice injected with nonopsonized M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis in the present study. The pH in this region of the intestine is approximately 8 in ruminants (24); however, M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis binds FN poorly at pHs of >7 (30). This indicates that M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis is unlikely to become opsonized with FN in this region of the small intestine. Because the ability of M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis to bind FN is enhanced by acid treatment, it has been proposed that the FN binding by M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis activated by passage through the ruminant abomasum, which maintains a pH of 3, and binds FN found in bile secretions in the duodenum, which has a pH of ≤4.5 (24, 30, 40). Thus, we suspect that in natural infections, M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis cells flowing into the ileum have already been opsonized with FN. The concentration of FN used to opsonize M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis in this investigation (2 μg/ml) is equivalent to those reported for human bile (2 to 26 μg/ml) (21, 40). Hence, we believe that the use of FN-opsonized organisms in this investigation more closely resembles the situation in natural infections.

To our knowledge, the present study is the first to directly demonstrate FN-mediated bacterial invasion in vivo. This report identifies FAP-P as an opsonic adhesin and quite possibly an invasin. In addition, we have distinguished selective M-cell invasion, which occurs through the formation of an FN bridge between FAP-P on M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis and M-cell surface integrins, from invasion of VE cells, which is accomplished by a mechanism that has yet to be characterized.

Several lines of experimental evidence have indicated that FAP-P is not expressed on the surface of M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis: (ii) FN binding by M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis was inhibited only when anti-FAP IgG was added together with FN; (ii) immunofluorescent detection of FAP-P on M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis required the extraction of cell envelope lipids; (iii) FAP-P was identified in the crude cytoplasmic fraction (including the soluble phase of the cell envelope) of M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis lysates but not in the cell wall fraction; and (iv) by immunoelectron microscopy, FAP-P was located immediately outside the peptidoglycan layer and beneath the exterior surface of the cell wall of M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis (30). Because FAP-P would therefore not be able to engage FN directly, it was postulated that one or more proteins might interact with FN to facilitate its ultimate interaction with FAP-P (30). Recently, it has been shown that antigen 85B and FAP act synergistically to promote attachment of M. tuberculosis to human respiratory mucosal tissue (19). It would be reasonable to hypothesize that these proteins function similarly in M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis. Whether antigen 85B and FAP-P bind FN simultaneously, sequentially, or independently is one of the subjects of current studies, as is the applicability of the results obtained in this investigation to oral infections with M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis in bovine calves.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Jennie Sturgis of the Purdue University Cytometry Laboratories for performing the confocal laser scanning microscopy described herein.

This work was supported by a Purdue University School of Veterinary Medicine internal grant.

Editor: S. H. E. Kaufmann

REFERENCES

- 1.Blystone, S. D., I. L. Graham, F. P. Lindberg, and E. J. Brown. 1994. Integrin alpha V beta 3 differentially regulates adhesive and phagocytic functions of the fibronectin receptor alpha 5 beta 1. J. Cell Biol. 127:1129-1137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blystone, S. D., S. E. Slater, M. P. Williams, M. T. Crow, and E. J. Brown. 1999. A molecular mechanism of integrin crosstalk: alphavbeta3 suppression of calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II regulates alpha5beta1 function. J. Cell Biol. 145:889-897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Byrd, S. R., R. Gelber, and L. E. Bermudez. 1993. Roles of soluble fibronectin and beta 1 integrin receptors in the binding of Mycobacterium leprae to nasal epithelial cells. Clin. Immunol. Immunopathol. 69:266-271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chiodini, R. J., H. J. Van Kruiningen, and R. S. Merkal. 1984. Ruminant paratuberculosis (Johne's disease): the current status and future prospects. Cornell Vet. 74:218-262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chitale, S., S. Ehrt, I. Kawamura, T. Fujimura, N. Shimono, N. Anand, S. Lu, L. Cohen-Gould, and L. W. Riley. 2001. Recombinant Mycobacterium tuberculosis protein associated with mammalian cell entry. Cell. Microbiol. 3:247-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clark, M. A., B. H. Hirst, and M. A. Jepson. 1998. M-cell surface beta1 integrin expression and invasin-mediated targeting of Yersinia pseudotuberculosis to mouse Peyer's patch M cells. Infect. Immun. 66:1237-1243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cocito, C., P. Gilot, M. Coene, M. de Kesel, P. Poupart, and P. Vannuffel. 1994. Paratuberculosis. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 7:328-345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cruz, N., X. Alvarez, R. D. Specian, R. D. Berg, and E. A. Deitch. 1994. Role of mucin, mannose, and beta-1 integrin receptors in Escherichia coli translocation across Caco-2 cell monolayers. Shock 2:121-126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Danen, E. H., S. Aota, A. A. van Kraats, K. M. Yamada, D. J. Ruiter, and G. N. van Muijen. 1995. Requirement for the synergy site for cell adhesion to fibronectin depends on the activation state of integrin alpha 5 beta 1. J. Biol. Chem. 270:21612-21618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dersch, P., and R. R. Isberg. 1999. A region of the Yersinia pseudotuberculosis invasin protein enhances integrin-mediated uptake into mammalian cells and promotes self-association. EMBO J. 18:1199-1213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harris, N. B., and R. G. Barletta. 2001. Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis in veterinary medicine. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 14:489-512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jaffe, B. M. 1974. Prostaglandins and cancer: an update. Prostaglandins 6:453-461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johansson, S., G. Svineng, K. Wennerberg, A. Armulik, and L. Lohikangas. 1997. Fibronectin-integrin interactions. Front. Biosci. 2:d126-146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jones, S. L., F. P. Lindberg, and E. J. Brown. 1999. Phagocytosis, p. 997-1020. In W. E. Paul (ed.), Fundamental immunology, 4th ed. Lippincott-Raven Publishers, Philadelphia, Pa.

- 15.Kerneis, S., A. Bogdanova, J. P. Kraehenbuhl, and E. Pringault. 1997. Conversion by Peyer's patch lymphocytes of human enterocytes into M cells that transport bacteria. Science 277:949-952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kinashi, T., T. Asaoka, R. Setoguchi, and K. Takatsu. 1999. Affinity modulation of very late antigen-5 through phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase in mast cells. J. Immunol. 162:2850-2857. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kingsley, R. A., R. L. Santos, A. M. Keestra, L. G. Adams, and A. J. Baumler. 2002. Salmonella enterica serotype Typhimurium ShdA is an outer membrane fibronectin-binding protein that is expressed in the intestine. Mol. Microbiol. 43:895-905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kuroda, K., E. J. Brown, W. B. Telle, D. G. Russell, and T. L. Ratliff. 1993. Characterization of the internalization of bacillus Calmette-Guerin by human bladder tumor cells. J. Clin. Investig. 91:69-76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Middleton, A., M. Chadwick, A. Nicholson, A. Dewar, R. Groger, E. Brown, T. Ratliff, and R. Wilson. 2002. Interaction of Mycobacterium tuberculosis with human respiratory mucosa. Tuberculosis 82:69-78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Middleton, A. M., M. V. Chadwick, A. G. Nicholson, A. Dewar, R. K. Groger, E. J. Brown, and R. Wilson. 2000. The role of Mycobacterium avium complex fibronectin attachment protein in adherence to the human respiratory mucosa. Mol. Microbiol. 38:381-391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miquel, J. F., C. Von Ritter, R. Del Pozo, V. Lange, D. Jungst, and G. Paumgartner. 1994. Fibronectin in human gallbladder bile: cholesterol pronucleating and/or mucin “link” protein? Am. J. Physiol. 267:G393-400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Momotani, E., D. L. Whipple, A. B. Thiermann, and N. F. Cheville. 1988. Role of M cells and macrophages in the entrance of Mycobacterium paratuberculosis into domes of ileal Peyer's patches in calves. Vet. Pathol. 25:131-137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Parker, A. E., and L. E. Bermudez. 1997. Expression of the green fluorescent protein (GFP) in Mycobacterium avium as a tool to study the interaction between mycobacteria and host cells. Microb. Pathog. 22:193-198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Phillipson, A. T. 1977. Ruminant digestion., p. 250-286. In M. J. Swenson (ed.), Dukes' physiology of domestic animals, 9th ed. Comstock Publishing Assoc., Ithaca, N.Y.

- 25.Ratliff, T. L., R. McCarthy, W. B. Telle, and E. J. Brown. 1993. Purification of a mycobacterial adhesin for fibronectin. Infect. Immun. 61:1889-1894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Redick, S. D., D. L. Settles, G. Briscoe, and H. P. Erickson. 2000. Defining fibronectin's cell adhesion synergy site by site-directed mutagenesis. J. Cell Biol. 149:521-527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sangari, F. J., J. Goodman, M. Petrofsky, P. Kolonoski, and L. E. Bermudez. 2001. Mycobacterium avium invades the intestinal mucosa primarily by interacting with enterocytes. Infect. Immun. 69:1515-1520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schorey, J. S., M. A. Holsti, T. L. Ratliff, P. M. Allen, and E. J. Brown. 1996. Characterization of the fibronectin-attachment protein of Mycobacterium avium reveals a fibronectin-binding motif conserved among mycobacteria. Mol. Microbiol. 21:321-329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schorey, J. S., Q. Li, D. W. McCourt, M. Bong-Mastek, J. E. Clark-Curtiss, T. L. Ratliff, and E. J. Brown. 1995. A Mycobacterium leprae gene encoding a fibronectin binding protein is used for efficient invasion of epithelial cells and Schwann cells. Infect. Immun. 63:2652-2657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Secott, T. E., T. L. Lin, and C. C. Wu. 2001. Fibronectin attachment protein homologue mediates fibronectin binding by Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis. Infect. Immun. 69:2075-2082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Secott, T. E., T. L. Lin, and C. C. Wu. 2002. Fibronectin attachment protein is necessary for efficient attachment and invasion of epithelial cells by Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis. Infect. Immun. 70:2670-2675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sigurđardóttir, Ó. G., C. M. Press, and Ø. Evensen. 2001. Uptake of Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis through the distal small intestinal mucosa in goats: an ultrastructural study. Vet. Pathol. 38:184-189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Singh, B., N. Rawlings, and A. Kaur. 2001. Expression of integrin alphaVbeta3 in pig, dog and cattle. Histol. Histopathol. 16:1037-1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Steele, J. G., B. A. Dalton, G. Johnson, and P. A. Underwood. 1995. Adsorption of fibronectin and vitronectin onto Primaria and tissue culture polystyrene and relationship to the mechanism of initial attachment of human vein endothelial cells and BHK-21 fibroblasts. Biomaterials 16:1057-1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stover, C. K., V. F. de la Cruz, T. R. Fuerst, J. E. Burlein, L. A. Benson, L. T. Bennett, G. P. Bansal, J. F. Young, M. H. Lee, G. F. Hatfull, et al. 1991. New use of BCG for recombinant vaccines. Nature 351:456-460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tizard, I. 2000. Veterinary immunology: an introduction, 6th ed. W. B. Saunders, Philadelphia, Pa.

- 37.Vachon, P. H., J. Durand, and J. F. Beaulieu. 1993. Basement membrane formation and re-distribution of the beta 1 integrins in a human intestinal coculture system. Anat. Rec. 235:567-576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang, X., C. A. Lessman, D. B. Taylor, and T. K. Gartner. 1995. Fibronectin peptide DRVPHSRNSIT and fibronectin receptor peptide DLYYLMDL arrest gastrulation of Rana pipiens. Experientia 51:1097-1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yamada, K. M. 1991. Adhesive recognition sequences. J. Biol. Chem. 266:12809-12812. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yu, J. L., R. Andersson, and A. Ljungh. 1996. Protein adsorption and bacterial adhesion to biliary stent materials. J. Surg. Res. 62:69-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhao, W., J. S. Schorey, M. Bong-Mastek, J. Ritchey, E. J. Brown, and T. L. Ratliff. 2000. Role of a bacillus Calmette-Guerin fibronectin attachment protein in BCG-induced antitumor activity. Int. J. Cancer 86:83-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhao, W., J. S. Schorey, R. Groger, P. M. Allen, E. J. Brown, and T. L. Ratliff. 1999. Characterization of the fibronectin binding motif for a unique mycobacterial fibronectin attachment protein, FAP. J. Biol. Chem. 274:4521-4526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]