I. Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a syndrome encompassing a number of phenotypic subtypes with differing clinical features. These comorbid processes may be due to a mechanical interdependence with the lung (i.e. hyperinflation and impaired ventricular filling), a localized or systemic inflammatory response to chronic tobacco smoke exposure (i.e. atherosclerosis, cachexia), or potentially an admixture of the two[1]. It is clear though that the presence and severity of such comorbidities has a significant impact on a patient’s health status and mortality, and a better understanding of the prevalence and etiology of such conditions may improve medical care. One such condition that has long been associated with increased health care costs and mortality in smokers is right sided heart dysfunction and pulmonary vascular disease [2]. Despite 50 years of clinical observations supporting this contention, however, there are still only limited tools available to assess pulmonary vascular remodeling in smokers. Joint appearance of coronary artery disease in COPD either presenting with cardiac or pulmonary symptoms is also being increasingly recognized as another potential manifestation of the relationship between COPD and the circulation [3, 4].

The process by which chronic tobacco smoke exposure leads to pulmonary vascular remodeling is not clear. It has been observed clinically in subjects with severe emphysema and histopathologically even in smokers with normal lung function [5]. While the former may be due to compression of the intraparenchymal vasculature or even pruning of the vessels, the latter likely represents an inflammatory process that could be the precursor for clinically significant hemodynamic changes[6]. Given the multitude of causes for this condition and the generally modest resultant increase in pulmonary arterial pressure, clinical and therapeutic investigation in this heterogeneous cohort is challenging.

Thoracic imaging is playing an increasingly central role in screening for and monitoring pulmonary vascular disease and has potential to be used in a complementary manner with functional studies such as right heart catheterization. Such imaging includes assessment of extra and intra parenchymal pulmonary vascular morphology, regional lung perfusion, and both right and left ventricular function. This article provides a brief overview of the mechanisms that may contribute to pulmonary vascular remodeling in smokers followed by a more detailed description of the imaging techniques that are increasingly being used to refine our understanding of this disease. In addition, it offers a brief overview of the known interplay between COPD and coronary artery disease.

I. Clinical Implications of Pulmonary Vascular Disease in COPD

Estimates of the prevalence of clinically significant pulmonary vascular disease in patients with moderate to severe COPD ranges from 25 to over 50%. [2]. For example, one study found that 63 out of 105 patients in whom the right ventricular (RV) systolic pressure was estimated had pulmonary hypertension[7]. In another study, of the 215 patients with severe COPD referred for surgical therapy receiving cardiac catheterizations, 50% had elevated pulmonary artery (PA) pressures [8]. Ninety one percent of patients catheterized as part of the National Emphysema Treatment Trial had PA systolic pressures greater than 20 mmHg [9].

Most patients with pulmonary hypertension in COPD are categorized as mild, with one study finding 13.5% of patients with elevated pulmonary pressures of greater than 35mmHg [8] and another finding 5.8% with more than mild elevation of pulmonary pressures. It is important, however, to consider the effect of mild pulmonary hypertension (PH) when superimposed on the already existing activity limitations caused by COPD. Additionally, resting pulmonary hypertension may significantly underestimate the effect of PH on exercise tolerance in patients with COPD [10].

Despite the heterogeneous prevalence of PH, it has been well known that it worsens exercise tolerance and is a predictor of hospitalization and mortality [11–13]. Treatment with oxygen has been thought to improve at least the pulmonary vasconstrictive effect of hypoxemia in COPD patients; however, despite treatment with long-term oxygen, PH continues to be predictive of mortality. The relationship between mortality and pulmonary hypertension may in part be due to the observation that pulmonary pressures tend to be particularly worsened during COPD exacerbations. The relationship between pulmonary hypertension and other cardiac morbidities associated with COPD remains difficult to quantify.

II. Mechanisms of Cardiopulmonary coupling in COPD

Increased pulmonary vascular resistance and accompanying RV dysfunction defines a specific pathophysiologic entity, cor pulmonale. The relationship of this process with airway disease, its selective progression, and the coupling of pulmonary vascular remodeling to right ventricular failure remains an area of intense research.

Initial studies of pulmonary vascular disease in smokers focused on the mechanical effects of emphysema and hyperinflation on perfusion. This is thought to predominantly affect the more compressible vasculature such as the alveolar capillary beds. Despite their peripheral anatomic location, interruption of blood flow at these sites has the potential for significant contribution to the overall vascular resistance [14]. More recent data from the National Emphysema Treatment Trial, however, suggests that a reduction in hyperinflation through surgical lung volume reduction does not systematically result in a significant improvement in hemodynamics [15, 16]. It is possible that although this mechanism plays a role in the development of the vascular disease, it has led to irreversible changes in patients eligible for lung volume reduction surgery. Alternatively, surgical excision of intact vascular beds may in some cases offset any improvements in pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) caused by a reduction in vessel compression.

Other causes of increased pulmonary vascular resistance include hypoxemia and hypercapnia. These processes, often found in patients with sleep disordered breathing and more severe expiratory airflow obstruction, appear to act synergistically to promote pulmonary vasoconstriction and remodeling. Under normoxic conditions, pulmonary vascular resistance will return to normal following transient changes in O2 and CO2. It has been suggested that prolonged exposure to hypoxemia may lead to irreversible remodeling of the vasculature; however, clinical observations suggest that the administration of supplemental oxygen attenuates the progression of pulmonary hypertension in COPD. Additional factors such as tissue destruction with emphysema, increased viscosity due to polycythemia and worsening acidosis may all contribute to the worsening pulmonary hypertension[17].

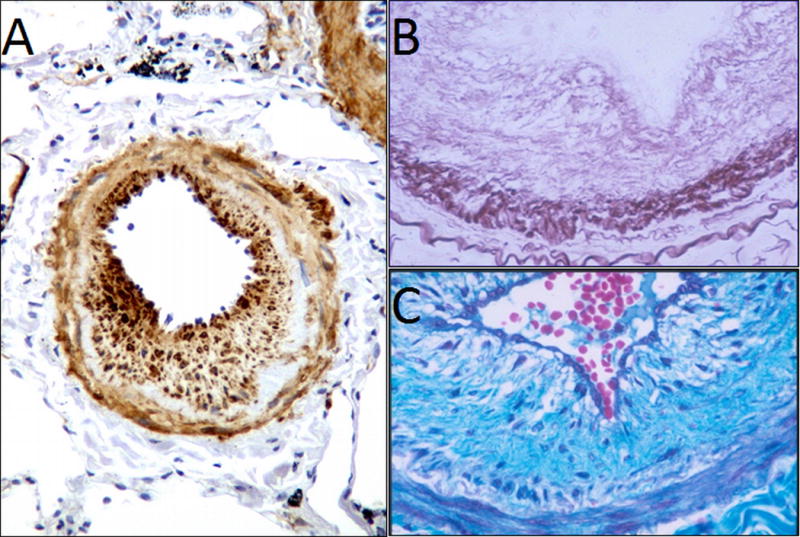

Despite the number of potential changes in the vascular environment associated with COPD, the irreversible remodeling of the pulmonary vasculature is thought to be the key common pathway marking disease progression [6, 18]. This process of remodeling has been extensively described and involves multiple stages thought to begin with endothelial dysfunction [19].Tobacco smoke exposure initiates an inflammatory cascade that results in thickening of the vessel walls (intimal hyperplasia), deposition of collagen and ultimately smooth muscle cell proliferation (Figure 1) [20]. It is thought that this process precedes the development of pulmonary hypertension in COPD [6, 18] since such vascular changes are also noted in smokers with normal lung function [5].

Figure 1.

Pathology of pulmonary hypertension in COPD showing the various progressive processes including smooth muscle proliferation, hyperplasia and deposition of collagen fibers [6] –

Despite the presence of progressive vascular remodeling, the extent of pulmonary hypertension and ventricular failure remain difficult to predict from the degree of vascular remodeling on histopathology [21]. In addition, it has been noted that aberrant angiogenesis may play an additional role in increased pulmonary vascular resistance [22] and that disturbance of the molecular constituents of pulmonary vascular bed may play a key role in the development and progression of COPD [23, 24]. Recently, it has been further appreciated that COPD may be considered as a systemic disease and that impairments in metabolism and inflammatory cascades as a whole may lead to the many manifestations of this disease including the vascular changes and right heart failure which may all evolve together [23]. For example, a study in 157 COPD patients showed a correlation between arterial stiffness as measured in the upper limb and the CT-based extent of emphysema [18]. In addition, Maclay et al demonstrated that there is systemic elastin degradation in COPD, which leads to loss of lung parenchyma and also has effects on the vasculature with increased peripheral resistance and on the skin with loss of elasticity [25]. All these effects compound on the increased pulmonary vascular resistance and right heart strain.

III. Diagnosis and Monitoring of pulmonary vascular disease in COPD: Role of Imaging

Right heart catheterization is the gold standard for the diagnosis of pulmonary vascular disease, but its invasiveness precludes its use in large study cohorts. Spirometry is used to diagnose COPD and monitor disease progression; however, studies have shown that the degree of expiratory airflow obstruction in smokers is neither sensitive nor specific for the presence of pulmonary vascular disease [17]. The diffusion length of carbon monoxide (DLCO) can be reduced due to pulmonary vascular disease, but it is not reliable when emphysema is also present, which may alter DLCO independently [26]. Imaging may provide a non-invasive tool to assess pulmonary vascular morphology, lung perfusion, inflammation, and cardiac coupling. The following is a brief overview of multiple imaging modalities divided into the study of the right ventricle, the pulmonary vascular anatomy (both proximal and distal) and lastly imaging of lung perfusion.

Imaging of the Right Ventricle

The hallmark radiographic findings suggestive of emphysema and hyperinflation include narrowing of the cardiac silhouette suggestive of underfilling of the cardiac chambers[23]. A subset of smokers, however, are found to have cardiomegaly with dilation of the right ventricle (RV). While radiographs are insensitive to the detection of early stage disease, it was historically well understood that by the time cardiomegaly is evident on conventional radiographs, that the prognosis was fairly poor.

The advent and availability of the echocardiogram has revolutionized screening and the diagnosis of pulmonary hypertension in patients with COPD. Specifically, estimations of the right ventricular (RV) systolic pressure using tricuspid regurgitation, [27] have been explored extensively in patients with COPD [28, 29]. Most often patients receive an echocardiogram as part of a work-up for cardiac ischemic disease, heart failure or dyspnea that appears out of proportion to their COPD. There remains concern, however, that echocardiography is inaccurate in detecting pulmonary hypertension in patients with more severe COPD[30]. This inaccuracy may be in part due to the rapid pressure changes in the chest cavity in the presence of significant parenchymal lung disease as well as inaccuracy introduced by increased distance between the probe and the heart [26, 30].

In addition to providing an estimate of pulmonary pressures, echocardiography has the advantage of providing a functional assessment of the right ventricle. A decrease in RV ejection fracture, and evidence of RV or right atrial (RA) dilation may all be indicative of progressive right sided heart failure and may prompt more aggressive treatment or further investigation by right heart catheterization. Recently, other more specific cardiac imaging markers have gained more widespread use in assessment of pulmonary hypertension. For example, the tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion (TAPSE), the distance travelled by the wall of the right ventricle as defined by the plane of the tricuspid valve, is measured during systole [31] and is thought to be a more reliable assessment of RV function than ejection fraction alone [32, 33]. Another functional echocardiographic parameter, the Myocardial Performance Index (Also referred to as the Tei index) has been further developed from the concept of assessing the time that the right heart spends in isovolumetric contraction and isovolumetric relaxation compared to the time it spends actually pumping blood [34]. This method has been studied in pulmonary hypertension patients and has been found to have good prognostic potential [34, 35].

Despite such advances in echocardiography, there remains significant concern about not capturing the full mechanical effect of the pressure-volume relationship that governs cardiac function with a simple 2D geometric model of the right ventricle. Such concerns may be addressed using 3-Dimensional echocardiography[36] and additional techniques such as tissue doppler imaging with the latter being leveraged to quantify the velocity of cardiac contraction and ejection of blood from the heart [37].

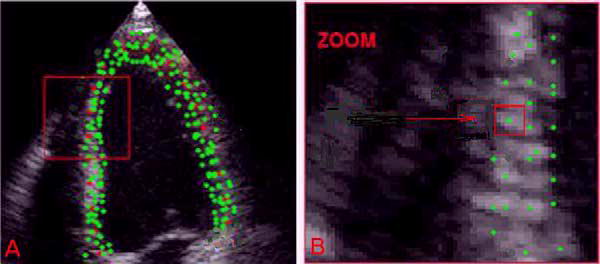

Another more recently developed technique, speckle tracking, takes advantage of the stable tissue based acoustic patterns that form which do not change their relationship with respect to each other significantly during cardiac motion (Figure 2) [38]. These natural markers or “speckles” are then tracked through the cardiac cycle giving a representation of muscle movement throughout the cardiac chamber. Both doppler tissue imaging and the refined speckle tracking can be used to estimate not only chamber anatomy but also a 2 or 3 dimensional strain pattern for the cardiac muscle [39]. These dynamic measurements of strain complement measurements of chamber size in providing a more complete mechanical view of the right heart chamber including estimation of pressure volume relationships [40] and are currently under investigation for short term monitoring and long-term prognostication in pulmonary vascular disease [41, 42].

Figure 2.

Speckle tracking using echocardiography. Speckles are identified on the echocardiogram and their movement is used to assess the relative position of the segments of the ventricular wall [38].

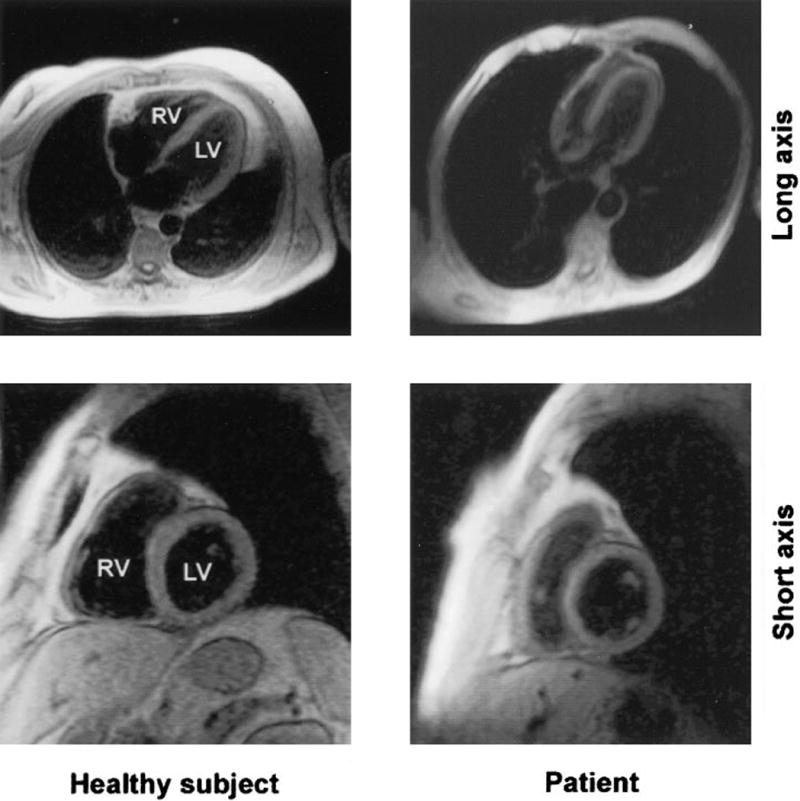

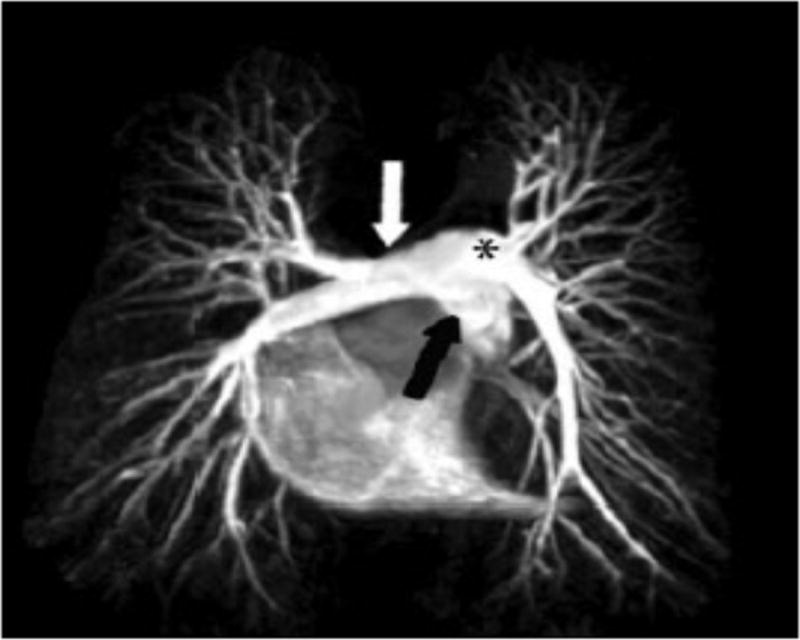

While echocardiograms have become widely available and are the standard for non-invasive monitoring of right ventricular function, recent advances in cardiac MRI have made it a fast growing alternative. Cardiac MRI naturally lends itself to 3D mapping of cardiac structure and function and changes such as increases in RV mass and decreases in stroke volume can be readily quantified. Recently it was observed that during exercise the RV stroke volume response was reduced in patients with COPD, likely due to exercise induced increases in pulmonary vascular pressures (figure 3) [43]. These signs of pressure overload detectable by cardiac MRI may even be present before decreased ejection fraction is noted [44]. For example, an index of adaptive change in RV measured by RV mass divided by RV end diastolic volume was significantly increased in mildly hypoxemic COPD patients as compared to normal controls, despite there being no difference in RV ejection fraction or estimated pulmonary pressures [45].

Figure 3.

Images of cardiac MRI showing RV anatomical changes in a COPD patient compared to a healthy subject [45].

The MRI data can further be used to estimate cardiac pressures and pulmonary vascular resistance [46]. Other more sophisticated measures of cardiac myocyte work-load, such as the kinetic energy contained in the muscle walls, can be derived [47]. Finally, phase contrast methods can be used to estimate blood flow and be combined with right heart catheterization to give a complete quantitative mechanical description of right heart function and its coupling to the pulmonary vasculature [48]. Parameters such as pulmonary artery (PA) capacitance, elasticity, distensibility, RV ejection fraction, RV end systolic volume, and right ventricular work index can all be monitored simultaneously. Using these techniques, PA stiffness predicts RV dysfunction even when accounting for increased pulmonary pressures suggesting that RV dysfunction may be driven in part by pulsatile work load [48].

Imaging of the Pulmonary Vasculature

Early angiographic studies of the lungs of smokers suggested that emphysema was associated with distal vascular narrowing and pruning [5, 20, 49, 50]. While providing some of the first in-vivo assessments of pulmonary vascular morphology, such techniques are limited in the subjective data that they may provide. Multi-detector CT (MDCT) scanning has made possible volumetric acquisition of isotropic data in a single breath hold. This improved acquisition time, resolution, and noise reduction, combined with increasing capabilities in storage and post-processing software have made this technology ideal for objective assessments of proximal and distal vascular structure.

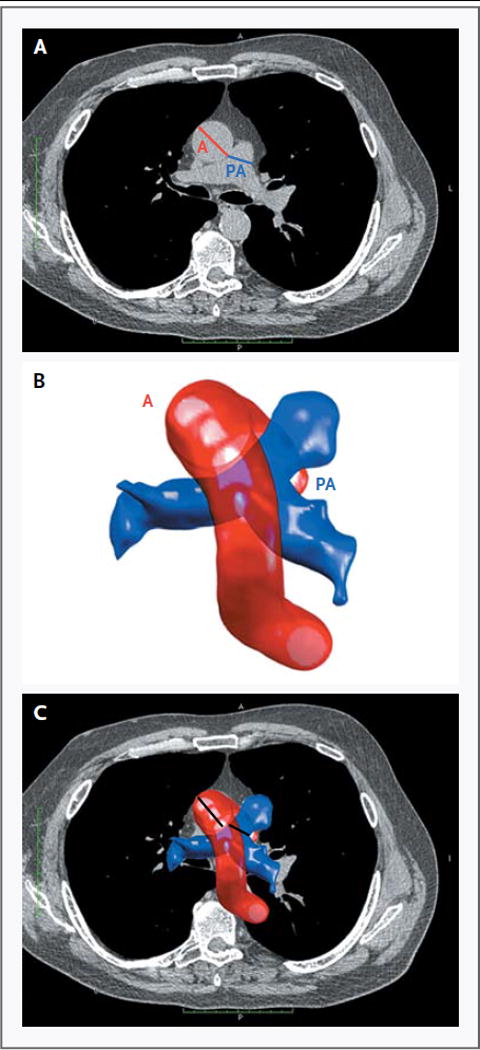

Even in the early era of CT scans, precise measurements of the proximal pulmonary artery were noted to be useful in predicting pulmonary hypertension[51]. This observation has been further refined by dividing the pulmonary artery diameter by the diameter of the descending aorta, finding not only the presence of pulmonary arterial enlargement but additionally good correlation with invasive hemodynamic measurements [52]. The result of these studies has yielded the general clinically used heuristic that a PA to Aortic diameter ratio greater than one should raise suspicion for clinically relevant pulmonary hypertension. In a large multicenter trial with over 3400 patients with COPD, analysis of this ratio was shown to be correlated with frequency of exacerbations (Figure 4) [53].

Figure 4.

Computation of PA diameter to aortic diameter ratio in patients with COPD. This ratio has been shown to be predictive of the presence of elevated pulmonary arterial pressures and correlated with frequency of exacerbations [53].

More dynamic assessments of proximal vascular morphology, such as PA distensibility, have been demonstrated to be predictive of the degree of pulmonary vascular disease. [54, 55] including subjects with COPD [56]. While the exact pathophysiological sequence leading to changes in the size and mechanical properties of the proximal vasculature remains to be elucidated, such changes may precede the development of RV dysfunction or even be a risk factor for it to develop. Decreased vascular distensibility may lower the efficiency of the heart by mechanically decoupling the RV from the arterial bed [57, 58].

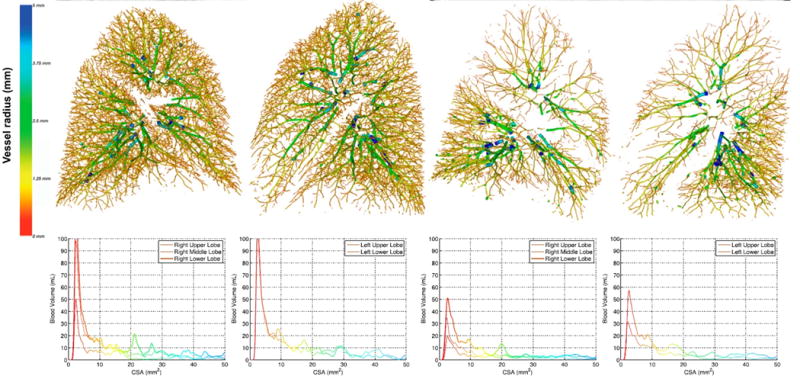

Quantitative assessment of microvascular morphology is generally beyond the resolution of most imaging modalities. While Gadolinium-enhanced MRI may provide measures of alveolar capillary perfusion, it cannot provide insight into capillary structure. However, distal remodeling and luminal occlusion eventually leads to pruning and occlusion of more proximal vessels and these can be visualized using CT and pulmonary angiography [59]. This relationship was first leveraged by Matsuoka et al who developed a technique for measuring the vascular cross sectional area (CSA) on non-volumetric axial HRCT data in smokers [60]. By limiting the structures of interest to those that appear circular in the axial plane, they were able to assess the aggregate cross sectional area of vessels of different sizes. Using CT and RHC data from the National Emphysema Treatment Trial, the total cross sectional area of vessels with area less than 5mm2 was shown to correlate with pulmonary arterial pressures in patients with severe emphysema. Current MDCT technology allows volumetric acquisition and isotropic reconstruction of structural data in the chest, and it is now possible to objectively assess vascular 3-dimensional structures. Advanced post-processing techniques have been developed that can identify blood vessels and the relative blood vessel volume as a function of aggregate vascular cross sectional area [61]. This measurement has been shown to have clinical implications in smokers beyond standard spirometric measures of lung function (Figure 5) [62]. These tools may provide a basis for monitoring of disease progression and treatment response using widely available imaging modalities in an anatomic site that is closer to where much of the pathophysiology may be taking place.

Figure 5.

Quantification of pulmonary vascular blood volume from volumetric CT scans and comparison of a non-smoker and a smoker with advanced COPD showing loss of pulmonary vasculature and decreased blood volume in the smaller vessels[62].

Functional Imaging: Perfusion

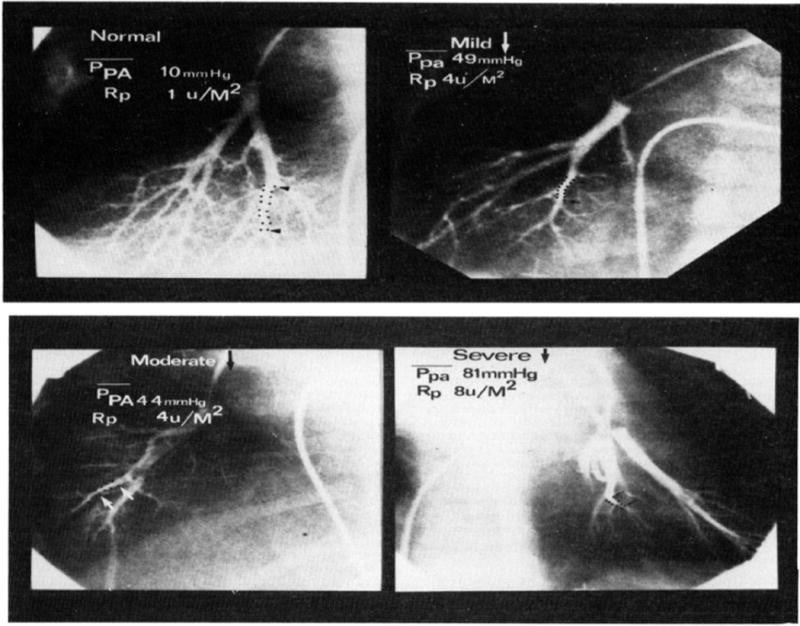

Pulmonary angiography has served as the gold standard for assessing proximal pulmonary anatomy as well as for providing insight into the relative perfusion of the various lung segments [63]. It is an invasive procedure that requires placement of a right heart catheter (RHC) followed by the fluoroscopic visualization of contrast medium injected directly into the pulmonary arteries (Figure 6). While this has significant clinical utility in the assessment for pulmonary embolism and extrinsic compression of the central vessels, it is limited to a series of 2D projections of 3D data and the need for placement of a RHC precludes its use in large scale studies.

Figure 6.

Classic angiogram showing distal vessel pruning in various stages of pulmonary hypertension associated with congenital heart defects [63].

With the advent of CT angiography and MR angiography, contrast injections are followed by high resolution image acquisition and post-processing, which give a similar visualization of the pulmonary vessels receiving blood (Figure 7) [64, 65]. However, because conventional angiography provides an animation of blood filling of the pulmonary vasculature, it can yield a non-quantitative but visual understanding of the relative perfusion of different segments.

Figure 7.

Angiogram constructed using MRI showing the pulmonary arterial anatomy[65].

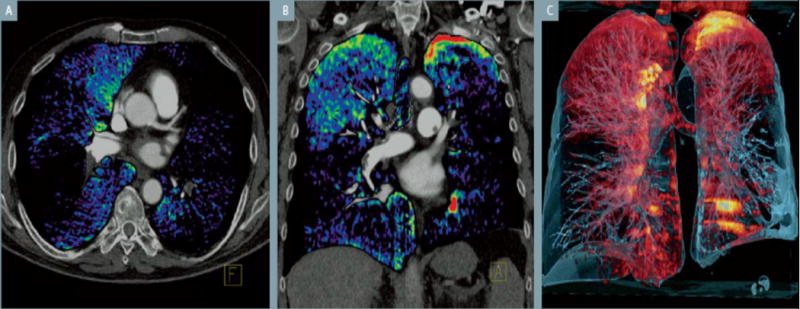

Dual energy CT imaging leverages tissue specific absorption of photons and two sources of radiation at different energies to produce an image that can differentiate structures not discernable on standard CT scanning [66]. In the lung, this can be exploited to measure the degree of penetration of contrast into the tissue and thus acquire a perfusion map of the lungs. Dual-energy CT scanning shows promise in looking at perfusion [67] and has been explored in applications such as detection of pulmonary emboli and chronic thromboembolic disease (figure 8) [68, 69]. This technique has also been applied in smokers, leading to the finding that lung perfusion is compromised in regions of emphysema proportional to the degree of parenchymal destruction [70]. The use of inhaled contrast agents such as hyper-polarized noble gases also allows for direct observation ventilation. As a contrast agent, 129-Xenon has the added benefit of being freely diffusible across that alveolar capillary boundary which further enables assessment of the most basic function of the lung, ventilation and perfusion matching in health and disease [71, 72].

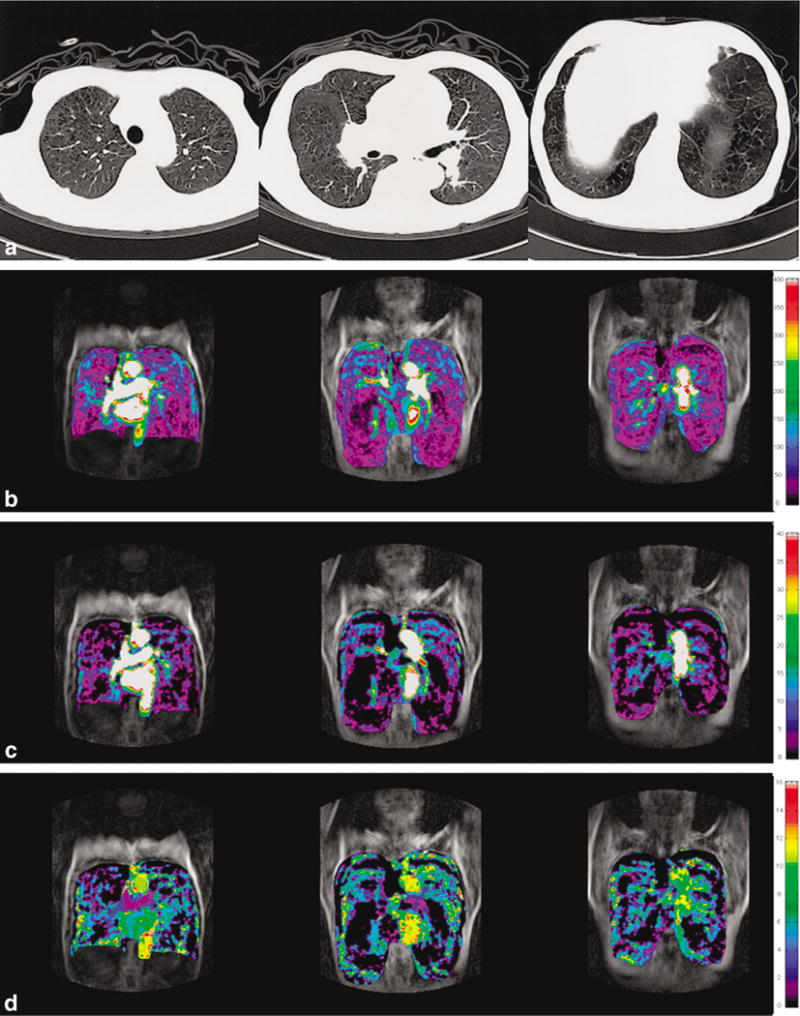

Figure 8.

Dual energy CT used to detect areas of perfusion defect, in this case caused by a pulmonary embolus. A) Axial reconstruction with color-coded dual energy perfusion, showing perfusion defects in both lungs. B) Coronal reconstruction with perfusion defects throughtout except the apices. C) Volume rendered image. (From Siemen’s booklet on their dual CT device)

Similar to MDCT, contrast enhanced MRI can be used to assess regional lung perfusion. With MRI, the progressive dilution of contrast can be followed, from which multiple markers of tissue perfusion can be derived, including time of transit of blood through the pulmonary circulation, pulmonary blood flow and pulmonary blood volume [73]. This has been shown to correlate with disease severity in patients with pulmonary hypertension [74]. Additionally, some correlation has been shown with invasive hemodynamic measurements in pulmonary hypertension [75] and this method has also been demonstrated to be useful in distinguishing between patients with group 1 PH and those with chronic thromboembolic disease [76]. For more information on this technique, also see the accompanying article by Swift et al in this issue.

Another method that may be useful for quantifying perfusion is use of the radioisotope 15-Oxygen to assess the degree of perfusion. Since the development of positron emission tomography (PET), it has been investigated as a tool for studying the pulmonary vasculature [77] and more recently to quantify parenchymal perfusion abnormalities in patients with asthma, pulmonary embolism and COPD (Figure 9) [78, 79]. One advantage of PET scanning is that it allows for temporal monitoring of perfusion and ventilation during both quiescent observation and following therapeutic intervention.

Figure 9.

Pulmonary perfusion as assessed by contrast dilution techniques. Panel a shows the reference chest CT with panlobular emphysema. Panel b shows heterogeneously decreased regional pulmonary blood flow. Panel c shows heterogeneously decreased blood volume. Panel d shows decreased regional mean transit time of blood [73].

IV. Treatment of pulmonary vascular disease in COPD

Because of the known link between hypoxemia and pulmonary vasoconstriction, continuous oxygen therapy has been extensively studied as a therapy of pulmonary hypertension in COPD. This is particularly true if hypoxemia is worsened by sleep disordered breathing at nights. Oxygen therapy has been shown to stabilize the progression of pulmonary hypertension despite worsening airway disease and offer minor improvement in hemodynamics [80] as well as exercise tolerance [81]. The treatment effects however, have not led to complete amelioration of symptoms and progression, leading to a search for better therapeutic options.

Treatment with medications used in pulmonary arterial hypertension (WHO group 1) has not yet been shown to be consistently beneficial in COPD patients. There have been conflicting reports of the utility of cycloxygenase inhibitors in this context [82]. An early small trial of prostacyclin in COPD patients in acute respiratory failure did not demonstrate improvement [83], but animal models have suggested that prostacyclin may have a protective effect in development of pulmonary hypertension in COPD [84]. Additionally, there has been a case-report of prostacycline being used in a COPD patient to treat disproportionate PH [85]. A clinical trial of Bosentan, an endothelin antagonist FDA approved for treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension, did not show improvement in hemodynamics, functional capacity or quality of life [86]. Currently no specific medication is FDA approved for use in pulmonary hypertension in COPD.

Surgical treatment with lung volume reduction surgery can help relieve obstructive airway disease hyperinflation. However, there is no evidence that LVRS improves hemodynamics, though by this advanced disease stage vascular remodeling may be irremediable [16] leaving lung transplantation as the only therapeutic option [87].

Currently the role of imaging in treatment of PH in COPD has been limited to monitoring the progression of pulmonary hypertension and the development of RV dysfunction as discussed above. Dynamic perfusion imaging with MRI or assessment of pulmonary parenchymal vascular morphology with MDCT may be useful in detecting pulmonary vascular abnormalities early on when treatments such as oxygen may have a more protective effect. Furthermore, phenotypic characterization of pulmonary vascular anatomy and perfusion may be useful in characterizing subtypes which may prove to respond to various therapies that have not yielded results in the general COPD population. Imaging based animal models may be useful in assess potential therapeutic targets as well as monitoring treatment efficacy and safety in humans.

V. Coronary Artery Disease and COPD

It is of interest to mention the correlation between COPD and coronary artery disease, which is likely a direct reflection of the systemic effects of cigarette smoking. With the use of large-scale studies screening for coronary artery calcification as a marker for coronary artery disease, it became apparent that many patients have comorbid disease of emphysema [3]. Similarly, large cohort studies evaluating the extent of COPD have found many patients also demonstrate coronary artery calcifications [4, 88] Furthermore, several studies have shown that this relationship is responsible for significant comorbidity and affects the outcome of patients with COPD and coronary artery disease.

Several studies demonstrated a correlation between COPD and cardiovascular fatal and non-fatal events [33, 35]. The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA), a large cohort study of 2,816 asymptomatic subjects being screened for coronary artery disease, showed a linear relationship between increasing CT-determined emphysema and decreasing MRI determined left ventricular function [3]. An MRI study evaluating left ventricular (LV) function also showed that LV function was diminished in patients with emphysema[89]. The same research group had also shown in a previous study that LV function improved following lung volume reduction surgery [29] supporting the hypothesis that hyperinflation may play a role in worsening heart function. A further study in 138 COPD patients showed that the size of cardiac chambers decreased with more severe COPD, and that impaired left ventricular diastolic filling pattern negatively impacted the 6 minute walking distance [31]. Lastly, the Evaluation of COPD Longitudinally to Identify Predictive Surrogate Endpoints ECLIPSE study, which evaluated the extent of COPD using CT in relation to smoking history, demonstrated that the coronary artery calcification was directly correlated with COPD as assessed by CT, the degree of dyspnea, exercise capacity and all cause mortality[32].

VI. Conclusion

Pulmonary vascular disease and subsequent right heart failure is a key mechanism of cardiopulmonary coupling in COPD. It has high prevalence, has been associated with symptomatic and functional impairment, and is a poor prognostic sign. The mechanism by which it develops includes hypoxemia, inflammation, vascular deformation due to hyperinflation, remodeling, and loss of vessels, all of which may lead to right ventricular dysfunction and failure. In addition, coronary artery disease and COPD are directly correlated, likely due to a common etiology with smoking history a key factor.

Imaging has been integrated into standard clinical practice, and echocardiography is commonly used to screen for pulmonary vascular disease in smokers. Coronary artery calcium scoring with CT is commonly employed in patients with risk factors for coronary artery atherosclerosis and will also yield pulmonary parenchymal information. In addition, phenotypic markers derived from anatomic and functional examination of the lung parenchyma are becoming increasingly available. These include three dimensional reconstruction of the intraparenchymal vasculature, as well as objective assessments of lung ventilation and perfusion. These phenotypic markers may be used in the future to assess potential therapeutic targets, identify more homogeneous subsets of disease for therapeutic investigation, and as an intermediate study endpoint for clinical investigation.

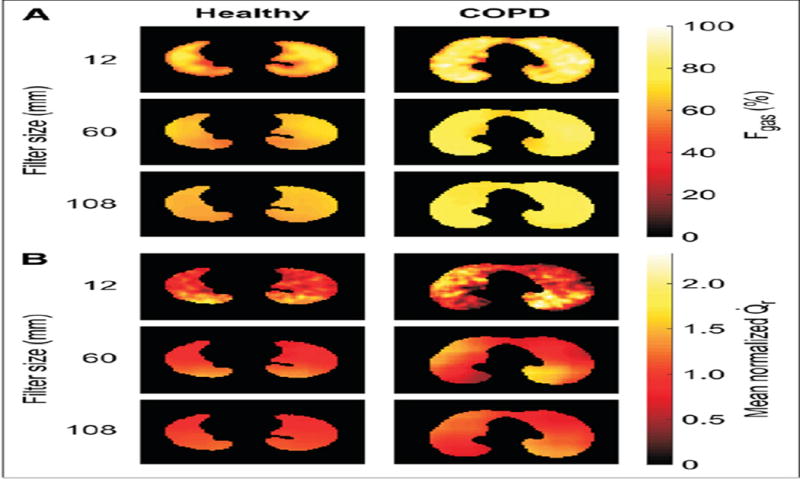

Figure 10.

PET imaging used to quantify the heterogeneity of regional ventilation and regional perfusion in lungs of a normal patient and a patient with COPD. Larger spatial filter length scales are used to highlight heterogeneity on different scales. Using this method it was demonstrated that the heterogeneity in perfusion was greater in patients with COPD and that it is not wholly accounted for by the heterogeneity in regional ventilation[79].

Contributor Information

Farbod N. Rahaghi, Email: frahaghi@partners.org, The Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Pulmonary and Critical Care, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, 75 Francis Street, PBB – CA 3, Boston, MA 02115.

Edwin J.R. van Beek, Email: edwin-vanbeek@ed.ac.uk, Director of Clinical Research Imaging Centre, University of Edinburgh, CO.19, QMRI, 47 Little France Crescent, Edinburgh, EH16 4TJ.

George R. Washko, Email: gwashko@partners.org, The Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Pulmonary and Critical Care, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, 75 Francis Street, PBB – CA 3, Boston, MA 02115.

References

- 1.Divo M, et al. Comorbidities and risk of mortality in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;186(2):155–61. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201201-0034OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Minai OA, Chaouat A, Adnot S. Pulmonary hypertension in COPD: epidemiology, significance, and management: pulmonary vascular disease: the global perspective. Chest. 2010;137(6 Suppl):39S–51S. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-0087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barr RG, et al. Subclinical atherosclerosis, airflow obstruction and emphysema: the MESA Lung Study. Eur Respir J. 2012;39(4):846–54. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00165410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Budoff MJ, et al. Coronary artery and thoracic calcium on noncontrast thoracic CT scans: comparison of ungated and gated examinations in patients from the COPD Gene cohort. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr. 2011;5(2):113–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jcct.2010.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Santos S, et al. Characterization of pulmonary vascular remodelling in smokers and patients with mild COPD. Eur Respir J. 2002;19(4):632–8. doi: 10.1183/09031936.02.00245902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barbera JA. Mechanisms of development of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease-associated pulmonary hypertension. Pulm Circ. 2013;3(1):160–4. doi: 10.4103/2045-8932.109949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fayngersh V, et al. Pulmonary hypertension in a stable community-based COPD population. Lung. 2011;189(5):377–82. doi: 10.1007/s00408-011-9315-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thabut G, et al. Pulmonary hemodynamics in advanced COPD candidates for lung volume reduction surgery or lung transplantation. Chest. 2005;127(5):1531–6. doi: 10.1378/chest.127.5.1531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Scharf SM, et al. Hemodynamic characterization of patients with severe emphysema. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166(3):314–22. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2107027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weitzenblum E, et al. Medical treatment of pulmonary hypertension in chronic lung disease. Eur Respir J. 1994;7(1):148–52. doi: 10.1183/09031936.94.07010148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oswald-Mammosser M, et al. Prognostic factors in COPD patients receiving long-term oxygen therapy. Importance of pulmonary artery pressure. Chest. 1995;107(5):1193–8. doi: 10.1378/chest.107.5.1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kessler R, et al. “Natural history” of pulmonary hypertension in a series of 131 patients with chronic obstructive lung disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164(2):219–24. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.164.2.2006129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sims MW, et al. Impact of pulmonary artery pressure on exercise function in severe COPD. Chest. 2009;136(2):412–9. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-2739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shepard JM, et al. Lung microvascular pressure profile measured by micropuncture in anesthetized dogs. J Appl Physiol (1985) 1988;64(2):874–9. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1988.64.2.874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sciurba FC, et al. Improvement in pulmonary function and elastic recoil after lung-reduction surgery for diffuse emphysema. N Engl J Med. 1996;334(17):1095–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199604253341704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Criner GJ, et al. Effect of lung volume reduction surgery on resting pulmonary hemodynamics in severe emphysema. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;176(3):253–60. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200608-1114OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chaouat A, Naeije R, Weitzenblum E. Pulmonary hypertension in COPD. Eur Respir J. 2008;32(5):1371–85. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00015608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McAllister DA, et al. Arterial stiffness is independently associated with emphysema severity in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;176(12):1208–14. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200707-1080OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barr RG. The epidemiology of vascular dysfunction relating to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and emphysema. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2011;8(6):522–7. doi: 10.1513/pats.201101-008MW. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hale KA, Niewoehner DE, Cosio MG. Morphologic changes in the muscular pulmonary arteries: relationship to cigarette smoking, airway disease, and emphysema. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1980;122(2):273–8. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1980.122.2.273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wright JL, Petty T, Thurlbeck WM. Analysis of the structure of the muscular pulmonary arteries in patients with pulmonary hypertension and COPD: National Institutes of Health nocturnal oxygen therapy trial. Lung. 1992;170(2):109–24. doi: 10.1007/BF00175982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hopkins N, McLoughlin P. The structural basis of pulmonary hypertension in chronic lung disease: remodelling, rarefaction or angiogenesis? J Anat. 2002;201(4):335–48. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-7580.2002.00096.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Van Beek EJR MS, Murchison JT. Radiology of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. In: MPaHA, editor. A colour atlas for COPD. Clinical Publishing; NY: 2013. In Press. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Voelkel NF, Douglas IS, Nicolls M. Angiogenesis in chronic lung disease. Chest. 2007;131(3):874–9. doi: 10.1378/chest.06-2453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maclay JD, et al. Systemic elastin degradation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax. 2012;67(7):606–12. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2011-200949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fisher MR, et al. Estimating pulmonary artery pressures by echocardiography in patients with emphysema. Eur Respir J. 2007;30(5):914–21. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00033007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yock PG, Popp RL. Noninvasive estimation of right ventricular systolic pressure by Doppler ultrasound in patients with tricuspid regurgitation. Circulation. 1984;70(4):657–62. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.70.4.657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tramarin R, et al. Doppler echocardiographic evaluation of pulmonary artery pressure in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. A European multicentre study. Working Group on Noninvasive Evaluation of Pulmonary Artery Pressure. European Office of the World Health Organization, Copenhagen. Eur Heart J. 1991;12(2):103–11. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a059855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jorgensen K, et al. Effects of lung volume reduction surgery on left ventricular diastolic filling and dimensions in patients with severe emphysema. Chest. 2003;124(5):1863–70. doi: 10.1378/chest.124.5.1863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Arcasoy SM, et al. Echocardiographic assessment of pulmonary hypertension in patients with advanced lung disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;167(5):735–40. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200210-1130OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Watz H, et al. Decreasing cardiac chamber sizes and associated heart dysfunction in COPD: role of hyperinflation. Chest. 2010;138(1):32–8. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-2810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Williams MC, Edwards LD MJ, et al. Artery calcification is increased in patients with COPD and associated with increased mortality and morbidity. Thorax. 2013 doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2012-203151. In Press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mapel DW, Dedrick D, Davis K. Trends and cardiovascular co-morbidities of COPD patients in the Veterans Administration Medical System, 1991–1999. COPD. 2005;2(1):35–41. doi: 10.1081/copd-200050671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tei C, et al. Noninvasive Doppler-derived myocardial performance index: correlation with simultaneous measurements of cardiac catheterization measurements. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 1997;10(2):169–78. doi: 10.1016/s0894-7317(97)70090-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Curkendall SM, et al. Cardiovascular disease in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, Saskatchewan Canada cardiovascular disease in COPD patients. Ann Epidemiol. 2006;16(1):63–70. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2005.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Di Bello V, et al. Advantages of real time three-dimensional echocardiography in the assessment of right ventricular volumes and function in patients with pulmonary hypertension compared with conventional two-dimensional echocardiography. Echocardiography. 2013;30(7):820–8. doi: 10.1111/echo.12137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rajagopalan N, et al. Utility of right ventricular tissue Doppler imaging: correlation with right heart catheterization. Echocardiography. 2008;25(7):706–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8175.2008.00689.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Leitman M, et al. Two-dimensional strain-a novel software for real-time quantitative echocardiographic assessment of myocardial function. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2004;17(10):1021–9. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2004.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Leong DP, et al. Nonvolumetric echocardiographic indices of right ventricular systolic function: validation with cardiovascular magnetic resonance and relationship with functional capacity. Echocardiography. 2012;29(4):455–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8175.2011.01594.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Russell K, et al. A novel clinical method for quantification of regional left ventricular pressure-strain loop area: a non-invasive index of myocardial work. Eur Heart J. 2012;33(6):724–33. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hardegree EL, et al. Role of serial quantitative assessment of right ventricular function by strain in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am J Cardiol. 2013;111(1):143–8. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2012.08.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Motoji Y, et al. Efficacy of right ventricular free-wall longitudinal speckle-tracking strain for predicting long-term outcome in patients with pulmonary hypertension. Circ J. 2013;77(3):756–63. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-12-1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Holverda S, et al. Stroke volume increase to exercise in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease is limited by increased pulmonary artery pressure. Heart. 2009;95(2):137–41. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2007.138172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Marcus JT, et al. MRI evaluation of right ventricular pressure overload in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Magn Reson Imaging. 1998;8(5):999–1005. doi: 10.1002/jmri.1880080502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vonk-Noordegraaf A, et al. Early changes of cardiac structure and function in COPD patients with mild hypoxemia. Chest. 2005;127(6):1898–903. doi: 10.1378/chest.127.6.1898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Swift AJ, et al. Noninvasive Estimation of PA Pressure, Flow, and Resistance With CMR Imaging: Derivation and Prospective Validation Study From the ASPIRE Registry. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2013.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Carlsen J, et al. Pulmonary arterial lesions in explanted lungs after transplantation correlate with severity of pulmonary hypertension in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2013;32(3):347–54. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2012.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stevens GR, et al. RV dysfunction in pulmonary hypertension is independently related to pulmonary artery stiffness. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2012;5(4):378–87. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2011.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jacobson G, et al. Vascular changes in pulmonary emphysema. The radiologic evaluation by selective and peripheral pulmonary wedge angiography. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med. 1967;100(2):374–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Magee F, et al. Pulmonary vascular structure and function in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax. 1988;43(3):183–9. doi: 10.1136/thx.43.3.183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kuriyama K, et al. CT-determined pulmonary artery diameters in predicting pulmonary hypertension. Invest Radiol. 1984;19(1):16–22. doi: 10.1097/00004424-198401000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ng CS, Wells AU, Padley SP. A CT sign of chronic pulmonary arterial hypertension: the ratio of main pulmonary artery to aortic diameter. J Thorac Imaging. 1999;14(4):270–8. doi: 10.1097/00005382-199910000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wells JM, et al. Pulmonary arterial enlargement and acute exacerbations of COPD. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(10):913–21. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1203830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Revel MP, et al. Pulmonary hypertension: ECG-gated 64-section CT angiographic evaluation of new functional parameters as diagnostic criteria. Radiology. 2009;250(2):558–66. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2502080315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Paz R, Mohiaddin RH, Longmore DB. Magnetic resonance assessment of the pulmonary arterial trunk anatomy, flow, pulsatility and distensibility. Eur Heart J. 1993;14(11):1524–30. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/14.11.1524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ertan C, et al. Pulmonary artery distensibility in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Echocardiography. 2013;30(8):940–4. doi: 10.1111/echo.12170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fourie PR, Coetzee AR, Bolliger CT. Pulmonary artery compliance: its role in right ventricular-arterial coupling. Cardiovasc Res. 1992;26(9):839–44. doi: 10.1093/cvr/26.9.839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Vonk Noordegraaf A, Naeije R. Right ventricular function in scleroderma-related pulmonary hypertension. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2008;47(Suppl 5):v42–3. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ken284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Engelke C, et al. High-resolution CT and CT angiography of peripheral pulmonary vascular disorders. Radiographics. 2002;22(4):739–64. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.22.4.g02jl01739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Matsuoka S, et al. Pulmonary hypertension and computed tomography measurement of small pulmonary vessels in severe emphysema. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;181(3):218–25. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200908-1189OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Estepar RS, et al. Computational Vascular Morphometry for the Assessment of Pulmonary Vascular Disease Based on Scale-Space Particles. Proc IEEE Int Symp Biomed Imaging. 2012:1479–1482. doi: 10.1109/ISBI.2012.6235851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Estepar RS, et al. Computed tomographic measures of pulmonary vascular morphology in smokers and their clinical implications. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;188(2):231–9. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201301-0162OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rabinovitch M, et al. Quantitative analysis of the pulmonary wedge angiogram in congenital heart defects. Correlation with hemodynamic data and morphometric findings in lung biopsy tissue. Circulation. 1981;63(1):152–64. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.63.1.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Schoepf UJ, et al. The Age of CT Pulmonary Angiography. J Thorac Imaging. 2005;20(4):273–9. doi: 10.1097/01.rti.0000185142.35361.da. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Junqueira FP, et al. Pulmonary arterial hypertension: an imaging review comparing MR pulmonary angiography and perfusion with multidetector CT angiography. Br J Radiol. 2012;85(1019):1446–56. doi: 10.1259/bjr/28150079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Johnson TR, et al. Material differentiation by dual energy CT: initial experience. Eur Radiol. 2007;17(6):1510–7. doi: 10.1007/s00330-006-0517-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Remy-Jardin M, et al. Thoracic applications of dual energy. Radiol Clin North Am. 2010;48(1):193–205. doi: 10.1016/j.rcl.2009.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hoey ET, et al. Dual-energy CT angiography for assessment of regional pulmonary perfusion in patients with chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension: initial experience. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2011;196(3):524–32. doi: 10.2214/AJR.10.4842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Pontana F, et al. Lung perfusion with dual-energy multidetector-row CT (MDCT): feasibility for the evaluation of acute pulmonary embolism in 117 consecutive patients. Acad Radiol. 2008;15(12):1494–504. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2008.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Pansini V, et al. Assessment of lobar perfusion in smokers according to the presence and severity of emphysema: preliminary experience with dual-energy CT angiography. Eur Radiol. 2009;19(12):2834–43. doi: 10.1007/s00330-009-1475-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lu GM, et al. Dual-energy CT of the lung. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2012;199(5 Suppl):S40–53. doi: 10.2214/AJR.12.9112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Washko GR, Parraga G, Coxson HO. Quantitative pulmonary imaging using computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging. Respirology. 2012;17(3):432–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2011.02117.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ohno Y, et al. Quantitative assessment of regional pulmonary perfusion in the entire lung using three-dimensional ultrafast dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging: Preliminary experience in 40 subjects. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2004;20(3):353–65. doi: 10.1002/jmri.20137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ohno Y, et al. Primary pulmonary hypertension: 3D dynamic perfusion MRI for quantitative analysis of regional pulmonary perfusion. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2007;188(1):48–56. doi: 10.2214/AJR.05.0135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ley S, et al. Value of MR phase-contrast flow measurements for functional assessment of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Radiol. 2007;17(7):1892–7. doi: 10.1007/s00330-006-0559-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ley S, et al. Value of high spatial and high temporal resolution magnetic resonance angiography for differentiation between idiopathic and thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension: initial results. Eur Radiol. 2005;15(11):2256–63. doi: 10.1007/s00330-005-2792-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Schuster DP, Mintun MA. Studying the pulmonary circulation with positron emission tomography. J Thorac Imaging. 1988;3(1):15–24. doi: 10.1097/00005382-198801000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Harris RS, Schuster DP. Visualizing lung function with positron emission tomography. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2007;102(1):448–58. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00763.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Vidal Melo MF, et al. Spatial heterogeneity of lung perfusion assessed with (13)N PET as a vascular biomarker in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Nucl Med. 2010;51(1):57–65. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.109.065185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Zielinski J, et al. Effects of long-term oxygen therapy on pulmonary hemodynamics in COPD patients: a 6-year prospective study. Chest. 1998;113(1):65–70. doi: 10.1378/chest.113.1.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Fujimoto K, et al. Benefits of oxygen on exercise performance and pulmonary hemodynamics in patients with COPD with mild hypoxemia. Chest. 2002;122(2):457–63. doi: 10.1378/chest.122.2.457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Park J, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of pulmonary hypertension specific therapy for exercise capacity in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Korean Med Sci. 2013;28(8):1200–6. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2013.28.8.1200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Archer SL, et al. A placebo-controlled trial of prostacyclin in acute respiratory failure in COPD. Chest. 1996;109(3):750–5. doi: 10.1378/chest.109.3.750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Nana-Sinkam SP, et al. Prostacyclin prevents pulmonary endothelial cell apoptosis induced by cigarette smoke. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175(7):676–85. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200605-724OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Shimizu M, et al. Disproportionate pulmonary hypertension in a patient with early-onset pulmonary emphysema treated with specific drugs for pulmonary arterial hypertension. Intern Med. 2011;50(20):2341–6. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.50.5995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Stolz D, et al. A randomised, controlled trial of bosentan in severe COPD. Eur Respir J. 2008;32(3):619–28. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00011308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Bjortuft O, et al. Pulmonary haemodynamics after single-lung transplantation for end-stage pulmonary parenchymal disease. Eur Respir J. 1996;9(10):2007–11. doi: 10.1183/09031936.96.09102007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Romme EA, et al. CT-measured bone attenuation in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: relation to clinical features and outcomes. J Bone Miner Res. 2013;28(6):1369–77. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.1873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Jorgensen K, et al. Reduced intrathoracic blood volume and left and right ventricular dimensions in patients with severe emphysema: an MRI study. Chest. 2007;131(4):1050–7. doi: 10.1378/chest.06-2245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]