Abstract

Background

Adolescent refugees face many challenges but also have the potential to become resilient. The purpose of this study was to identify and characterize the protective agents, resources, and mechanisms that promote their psychosocial well-being.

Methods

Participants included a purposively sampled group of 73 Burundian and Liberian refugee adolescents and their families who had recently resettled in Boston and Chicago. The adolescents, families, and their service providers participated in a two-year longitudinal study using ethnographic methods and grounded theory analysis with Atlas/ti software. A grounded theory model was developed which describes those persons or entities who act to protect adolescents (Protective Agents), their capacities for doing so (Protective Resources), and how they do it (Protective Mechanisms).

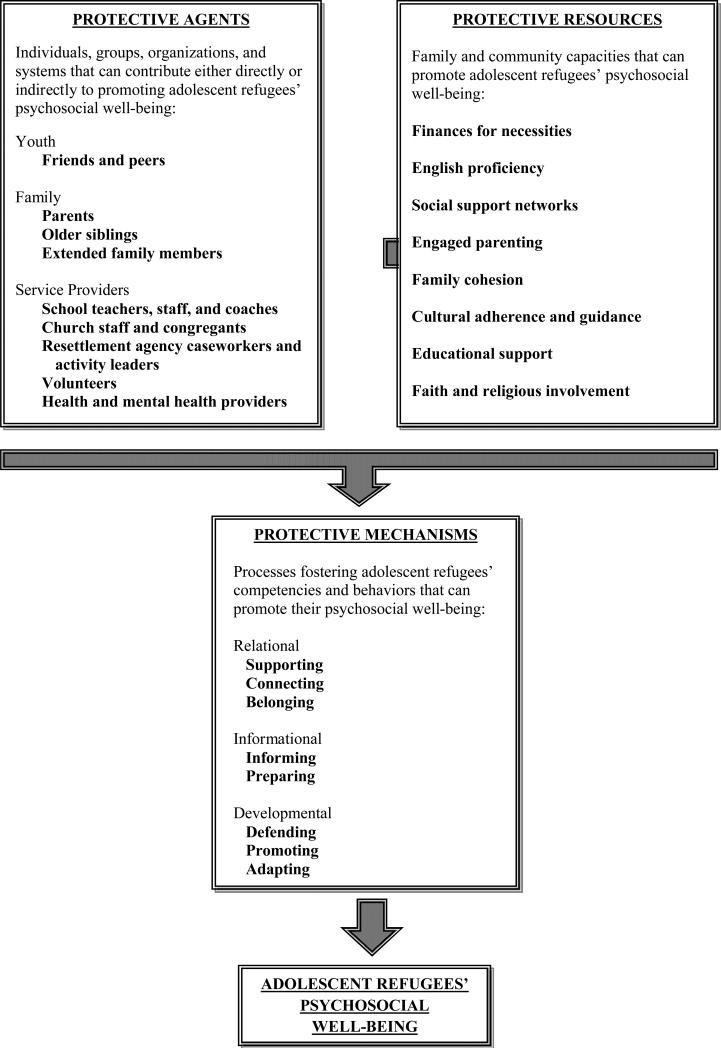

Protective agents are the individuals, groups, organizations, and systems that can contribute either directly or indirectly to promoting adolescent refugees’ psychosocial well-being. Protective resources are the family and community capacities that can promote psychosocial well-being in adolescent refugees. Protective mechanisms are the processes fostering adolescent refugees’ competencies and behaviors that can promote their psychosocial well-being.

Results

Eight family and community capacities were identified that appeared to promote psychosocial well-being in the adolescent refugees. These included 1) finances for necessities; 2) English proficiency; 3) social support networks; 4) engaged parenting; 5) family cohesion; 6) cultural adherence and guidance; 7) educational support; and 8) faith and religious involvement. Nine protective mechanisms identified were identified and grouped into three categories: 1) Relational (supporting, connecting, belonging); 2) Informational (informing, preparing), and; 3) Developmental (defending, promoting, adapting).

Conclusions

To further promote the psychosocial well-being of adolescent refugees, targeted prevention focused policies and programs are needed to enhance the identified protective agents, resources, and mechanisms. Because resilience works through protective mechanisms, greater attention should be paid to understanding how to enhance them through new programs and practices, especially informational and developmental protective mechanisms.

Keywords: Adolescents, African, protective resources, psychosocial, refugee

BACKGROUND

More than three million refugees have been resettled in the United States since 1975 (Refugee Council USA, 2013; US Department of State, 2013) with more than 58,000 resettled in 2012 (US Department of State, 2013). Since 2011, many of the resettled refugees have come from African countries, primarily Somalia, Liberia, Sudan, Ethiopia, and Burundi (Barnett, 2006) as determined by the processing priorities of the United States Refugee Admissions Program (U.S. Citizen and Immigration Services, 2011). The challenges that refugees face include trauma exposure, family loss and separation, poverty, learning English, low-wage work, troubled schools, inadequate housing, social and cultural transition, discrimination (racial, ethnic, and religious), and gender inequalities (Hodes, 2000; Kirmayer et al., 2011; Lustig et al. 2004). Prior research has documented the consequences of these challenges for the mental health of refugee adults and children, including post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, anxiety, somatic problems, alcohol and substance abuse, domestic violence, learning difficulties, and other behavioral and family problems (Drury & Williams, 2012; Lustig et al. 2004; Porter & Haslam, 2005).

Adolescent refugees in the U.S. are a particularly vulnerable group because their exposure to trauma and displacement coincides with key developmental transitions. Adolescents are at a time in their lives where they are experiencing shifts in responsibilities, identity explorations, and perhaps role confusion (Arnett, 2000). Adolescent refugees in the U.S. may experience a combination of both the child to adult transition familiar from the culture of their home country, and the adolescent transition seen in U.S. populations. Studies of adolescent refugees in resettlement show high rates of psychopathology (Becker, Weine, Vojvoda, & McGlashan, 2009; Muecke & Sassi, 1992; Tousignant, et al., 1999; Weine et al., 1995). Several longitudinal studies of psychiatric symptoms have shown high rates of PTSD and depressive symptoms (e.g. 50% in Cambodians) that generally diminish over time (Kinzie, Sack, Angell, Clarke, & Rath, 1986; Kinzie, Sack, Angell, Manson, Rath, 1989; Sack et al., 1993; Sack, Clarke, & Seeley, 1996; Sack, Him, & Dickason, 1999). Adolescent refugees with strong parental support and community engagement have diminished negative behavioral outcomes (Drury & Williams 2012; Geltman et al., 2005). Additionally, the adaptability that is part of adolescents’ development, may assist adolescent refugees in better adjusting to their new environments (Weine et al., 1995).

A prior study characterized the patterns of psychosocial adjustment among adolescent African refugees in U.S. resettlement (Weine et al, 2013). A purposive sample of 73 recently resettled refugee adolescents from Burundi and Liberia were followed for two years and qualitative and quantitative data was analyzed using a mixed methods exploratory design. The researchers first inductively identified 19 thriving, 29 managing, and 25 struggling youths based on review of cases. Multiple regressions indicated that better psychosocial adjustment was associated with Liberians and living with both parents. Logistic regressions showed that thriving was associated with Liberians and higher parental education, managing with more parental education, and struggling with Burundians and living parents. Qualitative analysis identified how these factors were proxy indicators for protective resources in families and communities.

The present study drew from the ethnographic data of that same study and aimed to build knowledge on the factors and processes that might account for differing patterns of adolescent refugee's adjustment, specifically their psychosocial well-being, which was defined as a state of mental and social well-being which is more than the absence of psychiatric symptoms or disorder.

Protective Agents, Resources, and Mechanisms Conceptual Framework

This research was grounded in family ecodevelopmental theory (Szapocznik et al., 1997; Szapocznik and Coatsworth 1999). Family ecodevelopmental theory envisions adolescents in the context of family systems and community networks interacting with educational, health, mental health, social service, and law enforcement systems. Ecodevelopmental theory explains how risk and protective factors may interact across adolescent's multiple social environments (Pantin, Schwartz, Sullivan, Coatsworth, & Szapocznik, 2003). Additionally, the study also drew upon trauma theories that explain the impact of and meaning of trauma exposure (Bracken, 2002; Friedman & Jaranson, 1994; Silove, 1999), and migration theories that explain why people move and how mobility impacts them (Falicov, 2003; Portes & Rumbaut, 2001; Portes & Zhou, 1993; Rumbout, 1991).We also drew upon resilience theory, which explains a person's or community's capacity to withstand or bounce back from adversity (Rutter, 1995; Walsh, 2003; 2006). Specifically, family therapists have used resilience to refer to domains of family life that may contribute to family adaptation after adversity, including shared family belief systems, family connectedness, and communication processes (Norris et al., 2008).

Based upon these theories, we first defined three new constructs so as to identify and deliberately distinguish between those which protect adolescents (protective agents), their capacities for protecting adolescents (protective resources), and how they do it (protective mechanisms). For the purposes of this study, these constructs were defined as follows.

Protective Agents are those individuals, groups, organizations, and systems that can contribute either directly or indirectly to promoting adolescent refugees’ psychosocial well-being. Protective agents can include parents, schools, and churches.

Protective Resources are the family and community capacities of protective agents that can promote adolescent refugees’ psychosocial well-being. Again, this means not only that they can stop, delay, or diminish negative mental health or behavioral outcomes among adolescent refugees, but also that they contribute to positive growth and development in a broader sense.

Protective Mechanisms are the processes fostering adolescent refugees’ competencies and behaviors that can promote their psychosocial well-being. Protective mechanisms are really about the unfolding of positive changes over time for adolescent refugees.

A conceptual framework was devised that maintained the distinction between protective agents, protective resources, and protective mechanisms as it endeavored to characterize their interactions. It posited that: 1) protective agents and resources exist in refugees’ family and social environments to protect against negative outcomes from their exposure to risks through war, migration, and resettlement; 2) through protective mechanisms, these protective agents and resources mitigate the family and ecological risks for negative individual behavioral (e.g. poor educational functioning) and mental health (e.g. depression) consequences and promote psychosocial well-being.

This framework, grounded in the previously mentioned theories, led us to focus this investigation on characterizing the protective mechanisms by which the protective agents and their protective resources yielded positive changes among refugee adolescents. It also informed our data collection and analysis in several ways. One, it helped in identifying domains of interest for the interviews and observations, including trauma experiences, family connectedness, and support networks in the community. Two, it helped in formulating questions used in minimally structured interviews and choosing sites and persons for observations. Three, it helped in identifying a priori domains of interest that focused the qualitative data analysis (Corbin & Strauss, 2008).

Prior Studies of Refugee Youth

To further inform this study of protective agents, resources, and mechanisms, we also reviewed prior studies of refugee youth that identified protective resources.

Several studies have identified protective resources that contributed to the psychosocial well-being of refugee youth. These included higher: acculturation, social support, collective self-esteem, strong ideological commitment, and family connectedness (Chung, Bemak, & Wong, 2000; Kovacev & Shute, 2004; McMichael, Gifford, & Correa-Velez, 2011; Punamaki, 1996; Rousseau, Drapeau, & Rahimi, 2003). Regarding school performance, other studies have identified: sense of belonging to family, school, and community and positive perceived school performance and commitment to education (Correa-Velez, Gifford, & Barnett, 2010; Kia-Keating & Ellis, 2007). Protective resources associated with refugee youth's school adaptation and outcomes include higher: acculturation, social support, social integration, goal commitment, and appropriate grade placement, as well as having healthy parents (Birman, Trickett, & Vinokurov, 2002; Lese & Robbins, 1994; Trickett & Birman, 2005; Wilkinson, 2002). Protective factors against psychiatric disorders include: having connectedness to family, peers, and the larger community, social support, strong religious beliefs, mothers with greater duration of education, higher socioeconomic status, and active community involvement in residential school system (Betancourt et al., 2012; Daud, Klinteberg, Rydelius, 2008; Montgomery, 2008; Servan-Schreiber, Lin, Birmaher, 1998).

These prior studies informed the conceptual framework, described in the previous section, which shaped data collection and analysis in several ways. One, data collection and analysis focused on protective agents in both family and community domains. Two, throughout the analysis, a distinction was maintained between those who protect adolescents (agents), their capacities for protecting adolescents (resources), and how they do it (mechanisms).

Burundian and Liberian Refugees

Burundians

In 1972, Burundians from the Hutu ethnic group fled a violent campaign from the Tutsi controlled government that led to the death of approximately 200,000 Burundians and the flight of 150,000 refugees to Tanzania, Rwanda, and the Democratic Republic of Congo (Cultural Orientation Resource Center, 2007; Weinstein, 1972). The genocide led by Michel Micombero, an army captain turned dictator, was designed to kill all educated Hutus older than fifteen years of age in order to prevent Hutus from coming to power (Krueger, 2007). Micombero was overthrown in 1976 by Lieutenant Colonel Jean-Baptiste Bagaza who continued to suppress and deny education to the Hutus (Krueger, 2007).

Living in exile in Tanzania for three decades, the so-called 1972 Burundian refugees experienced ongoing political and criminal violence, sexual assault, poverty, unemployment, dependency, no freedom of movement, family break-up, and poor education for children. While Burundians had access to food within the refugee camps, the lack of money caused many parents to send their oldest son to the capital, Dar es Salaam, to find a job (Sommers, 1999). Although illegal to move between refugee camps, some refugees were able to falsely identify themselves as Tanzanian (Sommers, 1999).

Ten thousand Burundian refugees from isolated Tanzanian refugee camps were resettled in the U.S. beginning in 2007. Many Burundians were unable to repatriate because of fear and the Tanzanian government's unwillingness to permanently resettle all Burundian refugees due to a large influx of refugees in the 1990s (COR Center, 2007). In relocating to the U.S., Burundian adolescents faced a unique resettlement paradigm because they were born and raised in refugee camps and lacked direct connections to their parents’ home country of Burundi. Burundian refugees in the United States have been resettled in small numbers and it is likely they do not have close relatives living in the United States (COR Center, 2007).

Liberians

From 1989 until 2003, Liberia suffered a series of ethnic conflicts among armed groups. Rebel forces, supported by Libya and Burkina Faso, led by Charles Taylor and Prince Johnson, tortured and killed Liberia's president Samuel Doe (Utas, 2003). It is estimated that up to forty percent of the combatants were child soldiers, under the age of eighteen with the youngest soldier documented to be six years old (Moran, 2006; Utas, 2003). An estimated 200,000 people were killed during the civil war and hundreds of thousands were forced to flee to other countries such as Guinea and Ivory Coast in 1990 (Bush pledges new aid, 2009; Toole & Waldman 1993). The World Health Organization stated that at least two-thirds of high school students in the capital city, Monrovia, had witnessed torture, rape, and murder, and were psychologically scarred (Fleischman & Whitman, 1994).

From 1992 to 2004, the U.S. resettled approximately 23,500 Liberian refugees who fled the war. Similar to Burundians, recently resettled Liberians did not have many family connections in the United States, with less than one third of those resettled in 2004 being reunited with relatives (Dunn-Marcos, Kollehlon, Ngovo, & Russ, 2005). In addition to family separation, they experienced economic, social, and cultural pressures in resettlement (Franz & Ives, 2008). Unlike the adolescent Burundians who were raised in Tanzanian refugee camps, many Liberian adolescent refugees experienced or participated in the war adding to the complexity of resettlement and integration into the American society.

Study Aims

This longitudinal ethnographic study addressed the following two research questions:

What protective agents and protective resources appear to contribute to psychosocial well-being in adolescent refugees?

What are the protective mechanisms through which these protective resources appear to contribute to psychosocial well-being in adolescent refugees?

Based upon the research findings, in the discussion the authors consider: How might policies, programs, and research better promote the protective agents, resources, and mechanisms that can contribute to refugee adolescents’ psychosocial well-being?

METHOD

Data Collection

This was a two-year, multi-site, longitudinal ethnographic study of Burundian and Liberian refugees resettled in Chicago, Illinois and Boston, Massachusetts. Study subjects were 73 purposively sampled at-risk refugee adolescents, their families, and service providers, interviewed within the first three years following resettlement. The sample consisted of 37 Liberian and 36 Burundian adolescent refugees with comparable numbers of Burundians and Liberians in Chicago and Boston. Based on a previous publication, there was no statistically significant difference between the psychosocial well-being of the adolescents resettled in Boston verses Chicago (Weine et al, 2013). The entire adolescent refugee population could be considered at-risk for psychosocial difficulties due to their exposure to trauma and displacement. However, for the purpose of this study, at-risk was defined as refugee youth with one or more of several specific factors that have been empirically associated with mental illness or behavioral problems in published studies of migrant youth (Hernandez, 2004). These were: 1) a one parent family; 2) poverty (monthly family income below U.S. Census poverty threshold (DeNavas-Walt, Proctor, & Mills, 2004); 3) living in a linguistically isolated household (e.g. no one in the house over age 14 speaks English very well; Perry & Schachter, 2003); 4) a mother or father with less than a high school education; 5) a parent who has sought or received mental health treatment (either counseling or medications). They were recruited from the refugee communities through refugee service organizations in metropolitan Chicago and Boston by fieldworkers from those communities. The purposive sampling strategy was intended to maximize diversity on three axes: 1) gender; 2) age; 3) Burundian or Liberian. All participants gave written informed consent as approved by the institutional review boards of the University of Illinois at Chicago College of Medicine and Harvard Medical School.

Data collection consisted of minimally-structured interviews and shadowing observations of individual study participants, and focused field observations carried out with each family in homes, communities, and service organizations. Minimally-structured interviews consisted of discussions with the participant that began with a small number of introductory questions (Sandelowski, 2000). The interviews included addressing the following domains: 1) Family and ecological protective factors; 2) Protective mechanisms linked to outcomes; 3) Experiences of outcomes by at-risk refugee adolescents; 4) Sociocultural contexts of protective factors, protective mechanisms, and outcomes. The conversation proceeded in whatever direction allowed the participant to speak most meaningfully to the research questions from his/her personal experience.

These interviews also gathered basic demographic characteristics (age, country of origin, family composition, parental education, parental employment) which enabled some quantitative exploration as described below and displayed in Table 1. Shadowing field observations involved the ethnographer accompanying the family or its members on his/her normal daily routine in a variety of sites (including home, school, community, and services). Shadowing observations allowed the ethnographers to directly witness the interactions between protective resources, risks, culture, and service sectors over time. Over the two-year study period, for each adolescent subject, we conducted six individual interviews, four hours of shadowing observation per quarter, plus four interviews with their family members and two interviews with their providers.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics.

| Variables | Values (n=73) |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 15.3 |

| Sex | |

| Female | 37 (51%) |

| Male | 36 (49%) |

| Country of Origin | |

| Burundian | 37 (51%) |

| Liberian | 36 (49%) |

| State of Resettlement | |

| Illinois | 40 (55%) |

| Massachusetts | 33 (45%) |

| Living Situation | |

| Lived with both parents | 39 (55%) |

| Lived with one parent | 34 (45%) |

| Parental Education | |

| Illiterate | 15 (21%) |

| Less than high school | 26 (36%) |

| High school | 31 (43%) |

The research team included several Liberians and several Burundians who were familiar with the community being studied, one psychologist, one nurse, one social worker, two public health academics, and one human development academic. The interviewers spoke the same language as the participants and were trained in ethnographic methods and supervised by the principal investigator and co-investigator, a psychiatrist and a medical anthropologist. All interviews and field notes were transcribed in English. Data was collected and analyzed based upon well-established approaches to ethnography and qualitative analysis (LeCompte & Schensul, 1999; Miles & Huberman, 1994). Because this study was trying to capture changes over time for each of the families, the investigators applied a case study research design whereby the data for each youth (transcribed interviews and field notes of observations) were read sequentially so as to identify factors that changed over time (Gillham, 2000).

Data Analysis

The initial study questions were refined through an iterative process of data collection and analysis that followed standardized qualitative methods utilizing a grounded theory approach to data analysis (Corbin & Strauss, 2008). We coded the same sections of text and compared their results, discussed, and resolved disagreements until a level of .80 agreement was reached. After establishing coder reliability, all transcripts were coded by multiple coders using an initial coding scheme agreed upon by the entire research team. The codebook consisted of codes that corresponded to demographic, contextual, and experiential matters, including gender, ethnicity, family, school, and trauma. Then, through pattern coding and memoing, the analysis formed typologies used to produce a grounded theory model. The different sources of data including adolescents, parents, and providers were first analyzed separately, and then they were integrated to enhance the value of multiple perspectives.

Not surprisingly, the data collected provided evidence of the challenges and difficulties that refugees face (e.g. family loss and separation, poverty, discrimination, and gender inequalities). However, these were not the focus of analysis, which was instead on building knowledge on possible protective agents, protective resources, and protective mechanisms. This model is described in the text and represented in Table 2 and Figure 1. All the findings were reviewed by the entire team to check for contrary evidence until consensus was achieved. The team determined the trustworthiness of the data based on the following techniques: 1) prolonged engagement by investing sufficient time to ensure accurate understanding of the phenomena being studied; 2) triangulation by using multiple sources, methods, theories, and investigators during the research process (Lincoln & Guba, 1985).

Table 2.

Integration of protective mechanisms by protective agents.

| Relational (supporting, belonging, connecting) | Informational (informing, preparing) | Developmental (defending, promoting, adapting) | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Youth (friends and peers) | + | - | - | + |

| Family (parents, older siblings, extended family members) | + | - | + | ++ |

| School (teachers, staff, coaches) | + | + | + | +++ |

| Church (staff and congregants) | + | + | - | ++ |

| Agency (resettlement agency case workers and activity leaders, volunteers) | + | + | + | +++ |

| Health Care (health and mental health providers) | - | - | - | 0 |

| Total | +++++ | +++ | +++ |

Figure 1.

Integrating Protective Agents, Protective Resources, and Protective Mechanisms

RESULTS

Protective Agents

Nine protective agents were grouped into three categories: 1) Youth; 2) Family; 3) Service Providers. These individuals, groups, organizations, and systems contributed either directly or indirectly to potentially promoting adolescent refugees’ psychosocial well-being.

Youth

Friends and peers

As for many teenagers, friends and peers played a central role in the daily lives of refugee adolescents. Because many of them lived, prayed, and went to school in neighborhoods heavily populated by other refugees and immigrants, their friends often came from their own ethnic community or another facing similar challenges. A 15-year-old Burundian boy talked about what he does with his friend, “J. is a close friend. We talk about everything that happens, do homework and play soccer and basketball together.” Most of these adolescents did not have friends who were part of the mainstream society.

Family

Parents

The adolescent refugees resettled in the U.S. with one or both parents or with other family caregivers. Parents provided their teens with emotional, material, and educational support, monitoring and supervision, cultural connections, and access to faith communities. A Liberian parent described the importance of family time for their children, “Once in a while my parents are here so we go and visit their grandparents. And they want to go to the pool, and I take them swimming. And they want to go to the park, and we go and play games from back home. And they like to go out, so once a month we go out to dinner at the restaurants around here. Just change the environment once in a while if I can afford it, I just want to make them feel happy once in a while.” However, most parents reported that they were highly burdened by concerns about their own well-being, family finances, and learning English, and these detracted from helping their children.

Older siblings

Some adolescent refugees had older siblings living with them who looked out for them in neighborhoods and schools, and served as cultural and language brokers. A 15-year-old Burundian boy explained how he helped his younger brother with schoolwork, “My younger brother knows division but he does not know multiplication...Yes, we help each other like that. I don’t show him the final result. I show him how to do it and he does it himself. I do that wanting to see if he has understood what I showed him.” Of course, older siblings shared that they also faced their own barriers to learning and adjusting.

Extended family members

Some adolescent refugees had extended family members close by or elsewhere in the U.S. These extended family provided family connectedness as well as material support. In some cases, when teens faced trouble at school or with the law, their parents sent them to live temporarily with their extended family. A Burundian mother explained how the children's grandparents lived in a different state but still provided material support to the family, “The children's grandparents in New Jersey send presents—clothes, shoes, and house things like plates.” However, extended family expressed that they often had their own worries and immediate family to provide for.

Service Providers

School teachers, staff, and coaches

Refugee adolescents worked with bilingual education or mainstream teachers. For most this took place in public schools, but for some it occurred in parochial schools or special schools for immigrants and refugees. The teachers’ work with adolescent refugees was not just instruction, but also counseling, family support, and conflict resolution. One teacher described her work with adolescent refugees as, “Success for any of my students would be for them to be able to understand their reality, and be able to manipulate and control it, to really enjoy engaging in the pursuit of knowledge. I really want these kids to have the foundation, so they have a chance in high school. These kids need the basic skills to help them, I mean, they have amazing insights, they have so much more lived experience than I do.” However, teachers and staff complained that they lacked specialized knowledge and skills on how to work with refugee children in resettlement, even though some had years of experience.

Church staff and congregants

Church members from multiple denominations provided spiritual guidance, material support such as rent money, food, and vehicles, after-school and social activities, and case-workers for adolescents experiencing trouble in school or at home. A 14-year-old Burundian boy explained, “This priest with two Ugandan fellow Christians have supported the family. The priest once in a while he gives food for the family, the two Ugandans have helped the father to get to the hospital when he was sick couple weeks ago.” However, church members stated that they lacked knowledge and training on how to work with refugee children in resettlement.

Resettlement agency caseworkers and activity leaders

Agency staff members were responsible for managing the logistics of resettlement which included travel, housing, initial material needs such as food and clothing, employment, job training, and language instruction. Agency caseworkers also connected families to financial resources, medical aid, after-school programs for youth, and tutoring, and helped youth get settled at their new schools. A Burundian parent explained how their caseworker has helped, “C is the family contact for health, financial, and school issues, he's the one who registers all the kids in a public school.” Resettlement agency caseworkers reported that they had limited time and resources for helping refugee families during resettlement and were often seen by the families as withholding money and not on their side.

Volunteers

Sometimes resettlement agencies or churches offered adolescent refugees and their families help through volunteers and sponsors. They augmented the support provided by resettlement agency staff by offering primarily companionship as well as help with paperwork, childcare, and financial assistance. A Liberian mother explained how a resettlement agency paired her with a volunteer, “She was my volunteer from the agency and for 3 months they pay your rent but you have to do everything on your own and they help you find a job and everything. And they put my son in school.” As volunteers, these persons reported that they often lacked time to provide ongoing support to refugee families after their initial resettlement.

Health and mental health providers

Teens were seen for routine care, or referred for special needs by teachers, school counselors, church staff, volunteers, and resettlement agency staff. An assistant principal explained how helpful the school social worker was, “I know that Z's dad has spoken to the social worker, but the problem is that she is the only social worker for 1200 kids. And she sees many kids individually with severe problems.” The health and mental health providers working with the refugee teens often reported being understaffed, under-supported, and under-trained to provide adequate care and support.

Protective Resources

The following eight family and community capacities appeared to potentially promote psychosocial well-being in the adolescent refugees.

Finances for necessities

Refugee families who had money for basic needs such as food, clothes, and school supplies, either via employment, entitlements, or community donations, appeared more able to provide stability and support for their teenage children. Parents who could afford these necessities felt more secure and were more confident providers. A Burundian father explained, “I decided to buy a computer with Internet access. She doesn't have to go to the library to do her homework. I want to avoid any kind of excuses. I want her to have what other American children have...if they can do it, she should be able to do it.”

English proficiency

Arriving in the U.S. already being able to speak English or learning English quickly upon resettlement helped refugee parents to find jobs, navigate social services for their families, and support their children's schooling. A Liberian father was better able to assist with his child's schooling by being able to communicate with the teachers, “The father has been to the school two times and he talks on the phone with the teachers frequently. He said that talking to the teachers was helpful because they tell him what is going on with his son and when he's good.” Families who arrived without English were able to attend English language classes at resettlement agencies or at community organizations.

Social support networks

Refugee families who were connected to and supported by members in their community, including friends, sponsors, church staff and congregants, and social service agencies, were better able to access and share information and resources for their adolescent children. For example, they were able to access tutoring and after-school activities for their children, or jobs that helped with family finances. A Burundian father stated, “The Burundians I found here introduced me to the agency. They helped me find a house and the agency paid the house rent for three months. They helped me find a job and had been giving me a ride to and from job until they contributed money for me to get me own car.”

Engaged parenting

Refugee parents who adapted their parenting styles and expectations through increased involvement and parent-child communication with their teenage children appeared better able to help their teens address issues of school and community adjustment, and making friends. A 15-year-old Liberian boy expressed the importance of his father's involvement in his life; “He always comes to things that I need him for. If I'm in school and I need a ride, I always call him, and he can come. Or a parent conference or something like that. Like yesterday, they had an honors breakfast, and I was invited, so he actually went there with me.”

Family cohesion

Families that shared positive family relationships with open communication, spending time together, and flexible attitudes, had more potential to add structure, security, and normalcy to their teens’ lives during resettlement. A Liberian mother stated, “We have family meetings and we all get together and talk about the problems that they are having with one another.”

Cultural adherence and guidance

Some families encouraged their adolescents to hold on to their traditional culture to prevent their teens from developing negative behaviors that are more associated with American culture. This was especially so for daughters. A Burundian father explained, “It's not good to lose the culture and I've been telling this to my daughters.” Although adhering to aspects that are deeply rooted in one's own culture, including religious beliefs and family values, may be protective for the adolescent, this does not suggest that adapting to some American traditions and behaviors, including learning the English and appropriate social behavior, are not protective as well.

Educational support

Parents, teachers, tutors, and the school encouraged the educational success of adolescent students by valuing education, talking about school days, offering homework assistance and support, problem solving, and mentoring. A 17-year-old Liberian girl described support from her teacher, she explained, “Teachers in the U.S. are good, they care about you a lot. They keep an eye out for me and my sister and try to make sure that we are getting the extra help we need. They push us to learn. They make sure we understand.”

Faith and religious involvement

Families with strong religious beliefs could use their faith to support adolescents in maintaining hope, making wise decisions, and developing effective coping skills. Attending church services and worshiping allowed families to feel spiritually connected, guided, and better able to overcome daily stressors and challenging transitions. A Liberian mother explained, “I believe God brought me here for a purpose, he brought my kids here for a purpose. He wants a better future for them, that's why he brought us here. I just decided to be strong enough and see a better future for my children.”

Protective Mechanisms

Nine protective mechanisms were identified. They are defined below and are grouped into three categories: 1) Relational; 2) Informational, and; 3) Developmental. The following protective mechanisms were processes fostering adolescent refugees’ competencies and behaviors that can promote their psychosocial well-being.

Relational

Supporting

Providing adolescent refugees with material, social, emotional, and advocacy needs. A Burundian father explained the support provided by the resettlement agency staff, “The case manager helped to get the social security cards, IDs, employment authorization documents. We told him about a problem with food stamps and he told us to talk to the food stamps director. He helps with social needs and he helped to register the kids in school.” A Burundian mother explained that their neighbor, a Somali woman, “helped us to get clothes and food and taught us how to take the bus.”

Connecting

Helping adolescent refugees become associated or joined with individuals, groups and organizations either in the resettlement or mainstream community. A 17-year-old Liberian student explained that he, “has stayed involved with the Student Leadership Program, which he attended the summer before he went to college. Sometimes a supervisor asks for recommendations for other students that he or past participants think would benefit from the program. One time a teen encouraged a friend to apply...”

Belonging

Providing close and loving relationships to adolescent refugees through acceptance, closeness, and attachment. A 14-year-old Liberian teen described quality time with his family, “We usually play games together, like board games and checkers. Sometimes on special occasions, like birthdays, or Father's or Mother's Day, we go out to eat and go to church. We spend a lot of time with our grandparents and other Liberians.” A Burundian adolescent described his closeness with three boys from his home country, he explained that they, “help one another, we correct each other when we are doing bad things. We keep each other's secrets and hang out all of the time. Because of our friendship, our parents are best friends.”

Informational

Informing

Imparting information to adolescent refugees regarding expectations, challenges, problems, opportunities, and help. A middle school teacher explained how she informs her students of expectations in the U.S., she stated, “ well, you know what, in this society, in this social structure, you need, you may want to consider, or you know, directly instruct that this, you need to do these things.” A pastor explained that he informs adolescents about laws and expectations because, “When people come and see such a freedom, they think, ‘Wow, I can just do anything.’ They don't realize that this country has laws and laws upon laws. For us who are pastors, when we come over is that we try to help them get over the cultural shocks. They need to know they are in a different society.”

Preparing

Getting adolescent refugees ready for future events such as for school transition, moving, employment, college applications, and family caregiving. A project coordinator from a school explained that she teaches the refugee adolescents social norms that they will be expected to know when they seek employment and also helps them to plan college visits. A Reverend explained that a host family requested a mentor to help a female adolescent succeed, “a Liberian young lady who is a psychology major at an outof-state university and a good Christian was asked by us to mentor her over the summer.”

Developmental

Defending

Keeping adolescent refugees from harm or danger in resettlement, especially concerning alcohol and drug use, gangs and criminality, and HIV/AIDS. A Liberian mother explained how she sent her teen to relatives to remove them from neighborhood trouble, “I gave my two children to them to help me straighten the children up, and to take care of them also.” A teacher explained the gangs and how he tries to help adolescents avoid negative influences: “new arrivals are not at risk for getting involved in gangs. These kids do not leave their homes at night but as time goes on and they begin to adjust to the culture they become more vulnerable.” He walk students home and talks with them about staying away from gangs.

Promoting

Advancing adolescent refugees maturation and development through being given new positions, responsibilities, or leadership. A 15-year-old Liberian youth explained his leadership position in school, “One of the positions they wanted me to take after they saw me in student council was sergeant of arms. Someone who will keep time, and keep the talking to a minimum when other people are talking. I signed up for that. They wanted me to give another speech again, so I had to write another one, and my worst teacher was the sponsor, and she told me that, “you can go out and do it because I am in there, and I will help you out if you need any help, so just talk to me,” so I said, “ok,” and I joined the African Club.”

Adapting

Facilitating adolescent refugees’ flexibility, responsiveness, and change regarding learning, working, interpersonal relations, identity, and future plans. A 17-year-old Liberian boy described how valuable his teacher was: “He was, like, really dedicated to teaching and ready to inspire any student who was ready to learn, and he was also helping every student to be the best that they can be. Like, he will stay in there and help you.” A teacher explained her approach to helping adolescent refugees in the classroom adjust to new circumstances: “I wondered how much of that type of behavior might be survival strategies learned previously, behaviors and mentalities that might have been necessary to survive in conditions of scarcity and uncertainty. Part of addressing their behavior is to create an environment that is safe and predictable, and where every student is assured of having everything they need in the classroom. Not needing to fight to get what they want.”

Integrating Protective Agents, Protective Resources, and Protective Mechanisms

Figure 1 summarizes the overall grounded theory model derived from investigation of the study sample characterizes how adolescent refugees’ psychosocial well-being is shaped by identifiable family and community protective agents and protective resources that are linked to protective mechanisms.

Protective Agents are the individuals, groups, organizations, and systems that can contribute either directly or indirectly to promoting adolescent refugees’ psychosocial well-being. The nine protective agents identified were grouped into three categories: 1) Youth (friends and peers); 2) Family (parents, older siblings, and extended family members); 3) Service Providers (school teachers, staff, and coaches; church staff and congregants; resettlement agency caseworkers and activity leaders; volunteers, and; health and mental health providers).

Protective Resources are the family and community capacities that can promote psychosocial well-being in adolescent refugees. The eight protective resources identified were: 1) finances for necessities; 2) English proficiency; 3) social support networks; 4) engaged parenting; 5) family cohesion; 6) cultural adherence and guidance; 7) educational support; and, 8) faith and religious involvement.

Protective Mechanisms are the processes fostering adolescent refugees’ competencies and behaviors that can promote their psychosocial well-being. Nine protective mechanisms identified were identified and grouped into three categories: 1) Relational (supporting, connecting, belonging); 2) Informational (informing, preparing), and; 3) Developmental (defending, promoting, adapting).

Table 2 summarizes the consensus patterns observed among protective agents and mechanisms in the study sample. Protective agents within the community domain were divided into sub-domains by location: school, church, agency, and health care. Overall, relational protective mechanisms were cited as being the most prevalent among the participants, followed by informational and developmental. The protective agents most actively involved with protective mechanisms were, from most to least active: school and agency (3+); followed by family and church (2+); youth (1+); health and mental health (0). Explanations for these different patterns of involvement are described below.

Discussion

This study looked at Burundian and Liberian refugee adolescents in U.S. resettlement. Despite abundant challenges and hardships, we found evidence of resilience in their families and communities. Using longitudinal ethnographic data and grounded theory analysis, and based on family-ecodevelopmental theory, we built a model that describes resilience in terms of the multilevel protective agents, resources, and mechanisms that appeared to promote adolescent refugees’ psychosocial well-being.

The study found that family members, teachers and peers, church members and volunteers were protective agents towards adolescents’ psychosocial well-being. However, regarding these protective agents, we found that as a whole these individuals, groups, and organizations were often overwhelmed, under-supported, lacked adequate knowledge and skills, and were disconnected from other protective agents. Despite some highly significant contributions, these deficiencies limited their capacities to promote the psychosocial well-being of refugee adolescents. These deficiencies should not be understood as predominantly individual deficiencies, but more as reflective of systems problems.

In particular, we found that health and mental health providers were under-performing relative to their potential contribution. This reflects both challenges accessing appropriate and affordable health and mental health services focused on adolescent refugees, but also the reluctance of adolescent refugees and their families to seek health or mental health services as a way of addressing their needs. Refugee adolescents and family members prefer turning to family and prayer for support rather than mental health services, which are often highly stigmatized. We also found that in the study sample, because the friends and peers were all refugees or immigrants who were generally no better integrated into mainstream society than the adolescent refugee themselves, they were not able to contribute much to their psychosocial well-being as protective agents.

Through examining the constructs of protective resources, we were able to better specify the capacities which protective agents need in order to be able to better promote refugee adolescents’ psychosocial well-being. Most importantly, their needs are multi-faceted in that they included both material, linguistic, social, familial, cultural, educational, and religious capacities. Some, such as faith, were more under the control of the refugees to maintain, whereas others, such as finances for necessities, were highly difficult for the refugees to negotiate without support from organizations and government.

Regarding protective mechanisms, we found that the nine identified were not distributed evenly, with developmental and informational mechanisms under-emphasized in comparison with relational mechanisms. Adolescent refugees were not being provided with adequate and accurate information and they were not being helped to anticipate, prepare for, and adjust to the many new challenges that they face. This does not mean that support is not critically important, but that informational and developmental assistance were harder to come by and call for more deliberate strategies to bring about.

Recommendations

Given the broad spectrum of family and community processes involved in fostering resilience, what can policymakers and service providers do to enhance the psychosocial well-being of refugee adolescents in U.S. resettlement? The results suggest that enhancing adolescent refugees’ psychosocial well-being could be approached through strengthening the protective agents, resources, and especially mechanisms that were identified in this study sample.

To start, it is important to recognize that a mental health or health clinician in practice seeing individual patients may not be able to do much to alter these family and community processes. However, clinicians who are engaged in service provision or consultation with schools, resettlement agencies, and faith-based organizations are better positioned. Furthermore, service providers do not only include clinicians, but refers also to a broad spectrum of workers who are positioned to help adolescent refugees in various contexts, including: school teachers, staff, and coaches; church staff and congregants; resettlement agency caseworkers and activity leaders; and volunteers. This broad spectrum of service providers can all function as protective agents for adolescent refugees.

Because the current limitations of protective agents reflect systems problems, it follows that protective agents could be strengthened through a systems approach that involves:

Building or strengthening the relationships between groups and organizations that can help refugee adolescents (e.g. between schools and faith institutions);

Convening dialogues about disruptions and solutions for refugee adolescents (e.g. about priority risks such as dropout, crime, drugs, HIV);

Linking informal networks with institutions involved with refugee adolescents (e.g. connect parents with schools);

Creating feedback loops regarding information pertinent to refugee adolescents (e.g. monitoring most urgent health and social issues needing attention);

Enhancing the abilities of groups and organizations to be flexible in addressing the needs of refugee adolescents (e.g. that practices and policies change in response to length of time in U.S.).

It is especially important to prioritize strengthening health providers and families, who in this study sample, appeared to be under-performing relative to their potential. Targeted trainings of health providers, and family support and education interventions for refugee families could be helpful.

Policymakers and service providers could focus new initiatives on sustaining those protective resources that were strong (cultural adherence and faith), strengthening those protective resources that were weak (finances for necessities, English proficiency, social support networks) and initiating those protective resources that were the weakest (engaged parenting and educational support). It is especially important for policymakers and service providers to focus on the protective mechanisms being promoted because these are the actual processes by which positive changes occur. The findings indicated that there were deficiencies in informational and developmental protective mechanisms that call for targeted interventions. Moreover, the model indicates that because resilience works through protective mechanisms, greater attention should be paid to understanding how to enhance them through new programs and practices.

Of course government cannot solve these problems alone. However, government can provide resources, support, and guidance to increase the capacities of service providers in places where adolescent refugees can be helped. These in turn can work directly with youth and parents. In particular, the three highest priorities that emerged from this study were: 1) parenting educating and support interventions; 2) promoting greater parental involvement in education; 3) adequate jobs for refugee families.

Programs and providers could use the results of this study to reflect upon their current work with adolescent refugees and to develop new strategies. They might begin by asking: 1) Do current strategies and actions help to strengthen the protective agents, resources, and mechanisms that were identified in this study? If so how? 2) What other protective agents, resources, and mechanisms are instead being targeted? 3) What are the obstacles to enhancing protective resources and mechanisms and how can these be ameliorated or overcome?

Study Limitations and Further Research

This study had several limitations. One, given differences in language and culture, misunderstandings were possible. This challenge was addressed through a multi-lingual research team and ongoing review of translation and cultural issues. Two, the sample was not representative of all Liberian and Burundian refugees, let alone other refugee groups in the U.S., or U.S. adolescents. Thus, the study findings might not be generalizable to these other groups. Three, two years was a reasonably generous period over which to study change, however, not long enough to document processes, let alone outcomes. There is a need for further research that builds knowledge on protective agents, resources, and mechanisms. One priority is to conduct intervention research in communities to examine: which acts of enhancing protective agents, resources, and mechanisms work with whom, under what circumstances, and why? A second priority is bring the insights from this study into a study using survey and quantitative methods that would test models of relationships between protective agents, resources, mechanisms, and a range of outcomes. Both of these research activities would also have to involve constructing assessment measures for protective resources and mechanisms, as well as other key constructs. A third priority is to look at a more granular level at how protective mechanisms work in the life cycle and daily lives of adolescent refugees such as through experience sampling method (Strauss, 1996).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was supported by NIMH R01MH076118

Footnotes

ABOUT THE AUTHORS:

Stevan Merrill Weine M.D. is Professor of Psychiatry in the Department of Psychiatry at the University of Illinois at Chicago

Norma Ware Ph.D. is Associate Professor in the Department of Psychiatry and the Department of Global Health and Social Medicine at Harvard Medical School

Leonce Hakizimana B.A. was Research Data Analyst in the Department of Psychiatry at the University of Illinois at Chicago

Toni Tugenberg M.S.W. is Senior Research Coordinator at the Department of Global Health and Social Medicine at Harvard Medical School

Madeleine Currie Ed.D. is Resident Dean of Freshmen for Oak Yard at Harvard

Gonwo Dahnweih M.S.W. was Coordinator of Clinical & Research Programs in the Department of Psychiatry at the University of Illinois at Chicago

Maureen Wagner M.A. is Registered Nurse at Boston Health Care for the Homeless

Chloe Polutnik M.P.H is Visiting Research Specialist in the Department of Psychiatry at the University of Illinois at Chicago

Jacqueline Wulu M.S. is Medical Student in the College of Medicine at the University of Illinois at Chicago

DISCLOSURES OF CONFLICTS OF INTEREST:

The authors confirm that this article content has no conflicts of interest.

References

- Arnett JJ. Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American psychologist. 2000;55:469. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett BD. A new era of refugee resettlement [online]. Center for Immigrant Studies; 2006. Retrieved from, http://www.cis.org/RefugeeResettlement>. [Google Scholar]

- Becker DF, Weine SM, Vojvoda D, McGlashan TH. PTSD symptoms in adolescent survivors of “ethnic cleansing”: Results from a 1-year follow-up study. Journal of the American Academy Child Adolescent Psychiatry. 1999;38:775–781. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199906000-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betancourt TS, Salhi C, Buka S, Leaning J, Dunn G, Earls F. Connectedness, social support and internalising emotional and behavioural problems in adolescents displaced by the Chechen conflict. Disasters. 2012;36:635–655. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7717.2012.01280.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birman D, Trickett EJ, Vinokurov A. Acculturation and adaptation of Soviet Jewish refugee adolescents: Predictors of adjustment across life domains. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2002;30:585–607. doi: 10.1023/A:1016323213871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bracken P. Trauma: Culture, meaning, and philosophy. Whurr; London, England and Philadelphia, PA: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Bush pledges new aid for Liberian school children Voice of America. 2009 Nov; Retrieved from < http://www.voanews.com/content/a-13-2008-02-21-voa31/344813.html>.

- Chung RC-Y, Bemak F, Wong S. Vietnamese refugees’ levels of distress, social support, and acculturation: Implications for mental health counseling. Journal of Mental Health Counseling. 2000;22:150–161. [Google Scholar]

- COR Center The 1972 Burundians. Cultural orientation resource center refugee backgrounder. 2007 Retrieved from < http://www.cal.org/co/pdffiles/backgrounder_burundians.pdf>.

- Corbin J, Strauss A. Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. Sage Publications; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Correa-Velez I, Gifford SM, Barnett AG. Longing to belong: Social inclusion and wellbeing among youth with refugee backgrounds in the first three years in Melbourne, Australia. Social Science & Medicine. 2010;71:1399–408. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daud A, Klinteberg B, Rydelius PA. Resilience and vulnerability among refugee children of traumatized and non-traumatized parents. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health. 2008;2:1–11. doi: 10.1186/1753-2000-2-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeNavas-Walt C, Proctor BD, Mills RJ. U.S. Census Bureau. Income, poverty, and health insurance coverage in the United States: 2003. Current Population Reports, P60-226. U.S. Government Printing Office; Washington, DC: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Drury J, Williams R. Children and young people who are refugees, internally displaced persons or survivors or perpetrators of war, mass violence and terrorism. Current Opinion in Psychiatry. 2012;25:277–84. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e328353eea6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn-Marcos WR, Kollehlon KT, Ngovo B, Russ E. Liberians: An introduction to their history and culture. Center for Applied Linguistics; Washington, DC: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Falicov CJ. Immigrant family process. In: Walsh F, editor. Normal Family Processes. 3rd ed. Guilford Press; New York, NY: 2003. pp. 280–300. [Google Scholar]

- Fleischman J, Whitman L. Easy prey: Child soldiers in Liberia. Human Rights Watch; New York, NY: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Franz B, Ives N. Wading through muddy water: Challenges to Liberian refugee family restoration in resettlement.. Paper presented at the Annual International Studies Association Convention; San Francisco, CA. Mar, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman MJ, Jaranson J. The applicability of the post-traumatic stress disorder concept to refugees. In: Marsella AM, Bornemann T, Ekblad S, Orley J, editors. Amidst peril and pain: The mental health and well-being of the world's refugees. American Psychological Association; Washington D.C.: 1994. pp. 207–227. [Google Scholar]

- Geltman PL, Grant-Knight W, Mehta SD, Lloyd-Travoglini C, Lustig S, Landgraf JM, Wise PH. The “lost boys of Sudan:” Functional and behavioral health of unaccompanied refugee minors resettled in the United States. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 2005;159:585–591. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.159.6.585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillham B. Case study research methods. Continuum; London, England and New York, NY: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez DJ. Demographic change and the life circumstances of immigrant families. The Future of Children, Special Issue on Children of Immigrants. 2004;14:16–47. [Google Scholar]

- Hodes M. Psychologically distressed refugee children in the United Kingdom. Child Psychiatry and Psychology Review. 2000;5:57–69. [Google Scholar]

- Kia-Keating M, Ellis BH. Belonging and connection to school in resettlement: Young refugees, school belonging, and psychosocial adjustment. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2007;12:29–43. doi: 10.1177/1359104507071052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinzie JD, Sack WH, Angell RH, Manson S, Rath B. The psychiatric effects of massive trauma on Cambodian children: I. the children. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1986;25:370–376. [Google Scholar]

- Kinzie JD, Sack WH, Angell R, Clarke G, Rath B. A three-year follow up of Cambodian young people traumatized as children. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1989;28:501–504. doi: 10.1097/00004583-198907000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirmayer LJ, Narasiah L, Munoz M, Rashid M, Ryder AG, Guzder J, Pottie K. Common mental health problems in immigrants and refugees: General approach in primary care. Canadian Medical Association Journal. 2011;183:E959–E967. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.090292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacev L, Shute R. Acculturation and social support in relation to psychosocial adjustment of adolescent refugees resettled in Australia. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2004;28:259–267. [Google Scholar]

- Krueger R, Krueger K. From bloodshed to hope in Burundi. University of Texas Press; Austin: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- LeCompte MD, Schensul JJ. Designing and conducting ethnographic research. AltaMira; Walnut Creek, CA: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Lese KP, Robbins SB. Relationship between goal attributes and the academic achievement of Southeast Asian adolescent refugees. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 1994;41:45–52. [Google Scholar]

- Lustig S, Kia-Keating M, Grant-Knight W, Geltman P, Ellis H, Kinzie, J. D., Saxe GN. Review of child and adolescent refugee mental health. Journal of the America Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2004;43:24–36. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200401000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMichael C, Gifford SM, Correa-Velez I. Negotiating family, navigating resettlement: Family connectedness amongst resettled youth with refugee backgrounds living in Melbourne, Australia. Journal of Youth Studies. 2011;14:179–195. [Google Scholar]

- Miles MB, Huberman AM. Qualitative data analysis. Sage Publications; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery E. Long-term effects of organized violence on young Middle Eastern refugees’ mental health. Social Science & Medicine. 2008;67:1596–603. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran MH. Liberia: The violence of democracy. University of Pennsylvania Press; Philadelphia, PA: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Muecke MA, Sassi L. Anxiety among Cambodian refugee adolescents in transit and resettlement. Western Journal of Nursing Research. 1992;14:267–291. doi: 10.1177/019394599201400302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pantin H, Schwartz SJ, Sullivan S, Coatsworth JD, Szapocznik J. Preventing substance abuse in Hispanic immigrant adolescents: An ecodevelopmental, parent-centered approach. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2003;25:469–500. [Google Scholar]

- Perry MJ, Schachter JP. U.S. Census Bureau. Migration of natives and the foreign born. U.S. Government Printing Office; Washington, DC: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Porter M, Haslam N. Predisplacement and postdisplacement of refugees and internally displaced persons: A meta-analysis. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2005;294:602–612. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.5.602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portes A, Zhou M. The new second generation: Segmented assimilation and its variants. Annals of the America Academy of Political and Social Sciences. 1993;530:74–96. [Google Scholar]

- Portes A, Rumbaut R. Legacies: The story of the second generation. University of California Press; Berkeley, CA: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Punamaki R-L. Can ideological commitment protect children's psychosocial well-being in situations of political violence? Child Development. 1996;67:55–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Refugee Council USA History of the U.S. refugee resettlement program. 2013 Retrieved from < http://www.rcusa.org/?page=history>.

- Rousseau C, Drapeau A, Rahimi S. The complexity of trauma response: A 4-year follow-up of adolescent Cambodian refugees. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2003;27:1277–1290. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2003.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rumbout R. Migration, adaptation, and mental health: The experience of Southeast Asian refugees in the United States. In: Alderman H, editor. Refugee policy: Canada and the United States. York Lanes Press; Toronto, Canada: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M. Psychosocial adversity: Risk, resilience and recovery. Southern African Journal of Child and Adolescent Mental Health. 1995;7:75–88. [Google Scholar]

- Sack WH, Him C, Dickason D. Twelve-year follow-up study of Khmer youths who suffered massive war trauma as children. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1999;38:1173–1179. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199909000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sack WH, Clarke G, Him C, Dickason D, Goff B, Lanham K, Kinzie JD. A 6-year follow-up study of Cambodian refugee adolescents traumatized as children. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1993;32:431–437. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199303000-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sack WH, Clarke GN, Seeley J. Multiple forms of stress in Cambodian adolescent refugees. Child Development. 1996;67:107–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandelowski M. Whatever happened to qualitative description? Research in Nursing & Health. 2000;23:334–340. doi: 10.1002/1098-240x(200008)23:4<334::aid-nur9>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Servan-Schreiber D, Lin BL, Birmaher B. Prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder and major depressive disorder in Tibetan refugee children. Journal of the American Academy in Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1998;37:874–879. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199808000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silove D. The psychological effects of torture, mass human rights violations, and refugee trauma: Toward an integrated conceptual framework. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 1999;187:200. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199904000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sommers M. Urbanization and its discontents: Urban refugees in Tanzania. Forced Migration Review. 1999;4:22–24. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss JS. Assessing schizophrenia in daily life: The experience sampling method. Journal of Nervous & Mental Disease. 1996;184:644–646. [Google Scholar]

- Szapocznik J, Kurtines WM, Santiesteban DA, Pantin H, Scopetta M, Mancilla Y, Coatsworth JD. The evolution structural ecosystemic theory for working with Latino families. In: Garcia J, Zea MC, editors. Psychological Interventions and Research with Latino Populations. Allyn & Bacon; Boston, MA: 1997. pp. 156–180. [Google Scholar]

- Szapocznik J, Coatsworth JD. An ecodevelopmental framework for organizing risk and protection for drug abuse: A developmental model of risk and protection. In: Glantz M, Hartel CR, editors. Drug Abuse: Origins and Interventions. American Psychological Association; Washington, D.C.: 1999. pp. 331–366. [Google Scholar]

- Toole MJ, Waldman RJ. Refugees and displaced persons: War, hunger, and public health. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1993;270:600–605. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tousignant M, Habimana E, Biron C, Malo C, Sidoli-LeBlanc E, Bendris N. The Quebec adolescent refugee project: Psychopathology and family variables in a sample from 35 nations. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1999;38:1426–1432. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199911000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trickett EJ, Birman D. Acculturation, school context, and school outcomes: Adaptation of refugee adolescents from the former Soviet Union. Psychology in the Schools. 2005;42:27–38. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Citizen and Immigration Services The United States Refugee Admissions Program Consultation and Worldwide Processing Priorities. 2011 Retrieved from < http://www.uscis.gov/portal/site/uscis/menuitem.5af9bb95919f35e66f614176543f6d1a/?vgnextchannel=385d3e4d77d73210VgnVCM100000082ca60aRCRD&vgnextoid=796b0eb389683210VgnVCM100000082ca60aRCRD>.

- U.S. Department of State Refugee admissions. 2013 Retrieved from < http://www.state.gov/j/prm/ra/>.

- Utas BM. Doctoral thesis. Uppsala University; Stockholm, Sweden: 2003. Sweet battlefields: Youth and the Liberian Civil War. Retrieved from < http://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:163000/FULLTEXT01.pdf>. [Google Scholar]

- Walsh F. Family resilience: A framework for clinical practice. Family Process. 2003;42:1–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2003.00001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh F. Strengthening family resilience. 2nd ed. Guilford Press; New York: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Weine SM, Becker DF, McGlashan TH, Vojvoda D, Hartman S, Robbins JP. Adolescent survivors of “ethnic cleansing”: Observations on the first year in America. Journal of the Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1995;34:1153–1159. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199509000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weine SM, Ware N, Tugenberg T, Hakizimana L, Dahnweih G, Currie M, Wagner M, Levin E. Thriving, managing, and struggling: A mixed method study of adolescent African refugees’ adjustment. Adolescent Psychiatry. 2013;3:72–81. doi: 10.2174/2210676611303010013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinstein W. Conflict and confrontation in Central Africa: The revolt in Burundi, 1972. Africa Today. 1972;19:17–39. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson L. Factors influencing the academic success of refugee youth in Canada. Journal of Youth Studies. 2002;5:173–193. [Google Scholar]