Abstract

Cystathionine β-synthase (CBS) catalyzes metabolic reactions that convert homocysteine to cystathionine. To assess the role of CBS in human glioma, cells were stably transfected with lentiviral vectors encoding short hairpin RNA (shRNA) targeting CBS or a non-targeting control shRNA and subclones were injected into immunodeficient mice. Interestingly, decreased CBS expression did not affect proliferation in vitro but decreased the latency period prior to rapid tumor xenograft growth after subcutaneous injection and increased tumor incidence and volume following orthotopic implantation into the caudate-putamen. In soft agar colony formation assays, CBS knockdown subclones displayed increased anchorage-independent growth. Molecular analysis revealed that CBS knockdown subclones expressed higher basal levels of the transcriptional activator hypoxia-inducible factor 2α (HIF-2α/EPAS1). HIF-2α knockdown counteracted the effect of CBS knockdown on anchorage-independent growth. Bioinformatic analysis of mRNA expression data from human glioma specimens revealed a significant association between low expression of CBS mRNA and high expression of angiopoietin-like 4 (ANGPTL4) and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) transcripts, which are HIF-2 target gene products that were also increased in CBS knockdown subclones. These results suggest that decreased CBS expression in glioma increases HIF-2α protein levels and HIF-2 target gene expression, which promotes glioma tumor formation.

Implications

CBS loss of function promotes glioma growth.

Keywords: anchorage-independent growth, CBS, HIF-2α, hypoxia-inducible factor

Introduction

Cystathionine β-synthase (CBS) is a metabolic enzyme that catalyzes the reaction of homocysteine with either cysteine or serine to form cystathionine and either hydrogen sulfide or water, respectively (1). A study of colon cancer reported increased CBS expression in tumor compared to adjacent normal tissue and found that short hairpin RNA (shRNA) mediated silencing of CBS expression in colon cancer cell lines resulted in decreased proliferation, migration and invasion that was attributable to decreased hydrogen sulfide production (2). In contrast, CBS gene expression is silenced by promoter hypermethylation in gastric cancer (3). Thus, CBS may function to either promote or suppress tumor growth, depending on the cancer cell type.

In the brain, CBS is expressed by glia and astrocytes (4), which are the cells from which gliomas arise. Neural stem cells also express CBS and the addition of the substrate L-cysteine to culture media stimulated the in vitro differentiation of neural stem cells to neurons and astroglia, whereas knockdown of CBS expression by small interfering RNA suppressed L-cysteine-induced stem cell differentiation (5). Analysis of cancer stem cells from human gliomas revealed that expression of the transcriptional activator hypoxia-inducible factor 2α (HIF-2α) was increased in stem cells as compared to the bulk cancer cells and that HIF-2α promoted glioma stem cell self-renewal and survival (6, 7).

In this study, we analyzed the effect of CBS loss of function in U87-MG human glioma cells on tumor formation after subcutaneous or intracranial injection in immunodeficient mice. CBS knockdown decreased the latency time to rapid tumor xenograft growth and increased the incidence and volume of intracranial tumors. CBS knockdown also increased in vitro colony formation in a soft agar assay and increased the expression of HIF-2α and target genes encoding angiopoietin-like 4 (ANGPTL4) and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). HIF-2α knockdown counteracted the stimulatory effect of CBS knockdown on ANGPTL4 and VEGF expression as well as colony formation. In human glioma samples, decreased CBS expression was associated with increased ANGPTL4 and VEGF expression. Thus, decreased CBS expression in gliomas may promote tumorigenesis by increasing HIF-2α expression.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture

U87-MG cells (8) were cultured in DMEM with 10% FBS, 100 units/ ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ ml streptomycin (Invitrogen) at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2, 95% air incubator. Hypoxic exposure was carried out in a modular incubator chamber (Billups-Rothenberg). Fresh media containing 25 mM HEPES was added to the cells, the chamber was flushed with a gas mixture consisting of 1% O2, 5% CO2, and 94% N2, sealed, and incubated at 37°C.

Lentivirus production and gene knockdown

Lentiviruses were produced in HEK293T cells by transfection of the following plasmids: pMD.G, pCMV-ΔR8.91, and pLKO.1 shRNA expression vector as described (9). shRNA vectors targeting CBS and shNT non-targeting control vector were purchased from Sigma. A scrambled shRNA control vector (shScr) was constructed by insertion of an oligonucleotide containing the sequence 5′-cctaaggttaagtcgccctcg-3′ into pLKO.1. Construction of the lentiviral vector for expression of shRNA targeting HIF-2α (shHIF-2a#3) was described previously (9).

Tumor xenograft model

Animal protocols were in accordance with the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the Johns Hopkins University Animal Care and Use Committee. Mycoplasma-free U87-MG subclones were injected into 6–8 week-old male SCID mice. 5 × 106 cells were suspended in PBS, mixed with an equal volume of Matrigel (BD Bioscience), and injected subcutaneously into the flank. Tumor size was measured with calipers twice per week. Tumor volume (mm3) was calculated using the following formula: length (mm) × width (mm) × height (mm) × 0.52. Tumors were excised and stored at −80°C for RNA and protein extraction or fixed in 10% formalin for paraffin embedding. For immunohistochemistry, paraffin sections were dewaxed, hydrated, and antigens were retrieved with citrate buffer (10 mM citric acid, 2 mM EDTA, 0.05% Tween-20, pH 6.2). Immunohistochemistry was performed with an LSAB+ System HRP Kit (Dako) and anti-CD31 (Dianova) or anti-Ki67 (Novus Biologicals) antibody.

Orthotopic injection model

Male SCID/NCr mice (6–7 weeks old) were maintained in accordance with a protocol approved by the New York University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. U87-MG subclones were implanted stereotactically into mouse brains. Mice were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection with xylazine chloride hydrate (10 mg/kg) and ketamine (90 mg/kg) and a burr hole was drilled into the skull 0.1 mm posterior to the bregma and 2.3 mm lateral to the midline. U87-MG cells in 2 μl of medium were injected using a stereotactic head frame (David Kopf Instruments) in the defined location of the caudate/putamen using a 10-μl Hamilton syringe with a 1-inch 30-gauge needle attached and inserted into a Kopf microinjection unit (Model 5000 with Model 5001 Hamilton syringe holder). The needle was advanced to a depth of 2.35 mm from the cortical surface and the cell suspension was delivered over 3–4 minutes. Following injection, the needle was left in place for 2 minutes, then raised to a depth of 1.5 mm below the dura and left in place for an additional minute. Upon withdrawal of the needle, the burr hole was filled with bone wax and the incision sutured. On day 36, mice were anesthetized, perfused intracardially with PBS followed by 4% paraformaldehyde, and brains were harvested and placed in cold 4% paraformaldehyde overnight, followed by paraffin embedding. Tumor volume was calculated from hematoxylin- and eosin-stained sections using the formula: L × S2 × 1/2, where L and S are the long and short axis of the tumor. Depth of invasion was assessed as previously described (10).

Immunohistochemistry was performed on paraformaldehyde-fixed, paraffin-embedded, 4-μm sections using goat anti-mouse CD105/Endoglin (R&D Systems), rabbit anti-mouse/human cleaved caspase 3 (Cell Signaling Technology), or rabbit anti-mouse/human Ki67 (Thermo Scientific). For CD105 and Ki67, sections were deparaffinized, rehydrated, epitope retrieval was performed in a 1200-Watt microwave oven at 100% power in 10 mM sodium citrate buffer, pH 6.0 for 20 minutes and detection was carried out at 40°C on a NexES instrument (Ventana Medical Systems) using reagent buffer and detection kits from Ventana unless otherwise noted. For cleaved caspase 3, the Discovery XT instrument (Ventana Medical Systems) was used with online deparaffinization and antigen retrieval in citrate buffer for 32 minutes. Endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked with hydrogen peroxide. Antibodies were diluted in Dulbecco’s phosphate buffered saline (Life Technologies) as follows: CD105, 1:200; Ki67, 1:400; and cleaved caspase 3, 1:100. CD105 samples were incubated overnight at room temperature, whereas Ki-67 and cleaved caspase 3 sections were incubated at 40°C for 30 minutes and 4 hours, respectively. CD105 and Ki67 were detected with biotinylated horse anti-goat diluted 1:100 and biotinylated goat anti-rabbit diluted 1:200 (Vector Laboratories), respectively, followed by application of streptavidin-horseradish-peroxidase conjugate. Cleaved caspase 3 was detected using anti-rabbit multimer (HRP). The complex was visualized with 3,3 diaminobenzidene and enhanced with copper sulfate. Slides were washed in distilled water, counterstained with hematoxylin, dehydrated and mounted with permanent media. Appropriate positive and negative controls were included with the study sections.

Soft agar assay

2,500 U87-MG cells were suspended in 0.3% top agar and plated on 0.6% bottom agar. Both agar layers contained DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 units/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin. Plates were incubated for 3 to 4 weeks at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2, 95% air incubator.

Reverse transcription and quantitative real-time PCR (RT-qPCR)

Total RNA was isolated with TRIZOL (Invitrogen), treated with DNase I (Ambion), and cDNA was synthesized using the iScript cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad). qPCR was performed using SYBR Green (Bio-Rad). The target mRNA expression was calculated, relative to 18S rRNA levels in the same sample, based on the Δ(ΔCt) method: ΔCt = Cttarget − Ct18S; Δ(ΔCt) = Cttest-subclone − Ctcontrol-subclone. Primer sequences are listed on Supplemental Table 1.

Immunoblot assays

Whole cell lysates and tissue lysates were prepared in modified RIPA buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.6], 150 mM NaCl, 1% IGEPAL CA-630, 1% Sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS) supplemented with protease inhibitors (Roche). Antibodies against following proteins were used: HIF-1α (BD Biosciences), HIF-2α (Novus Biologicals), CBS (Abnova), and Actin (Santa Cruz).

Statistical analysis

Data from U87-MG subclones were compared by Student’s t test or analysis of variation, prior to data normalization. Gene expression profiles from human brain cancers (11) were obtained from the GEO database (GSE4290). To analyze the correlation between CBS and VEGF or ANGPTL4 mRNA expression, Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r) was determined and the associated p value was calculated using GraphPad Prism software.

Results

CBS loss of function decreases tumor xenograft latency

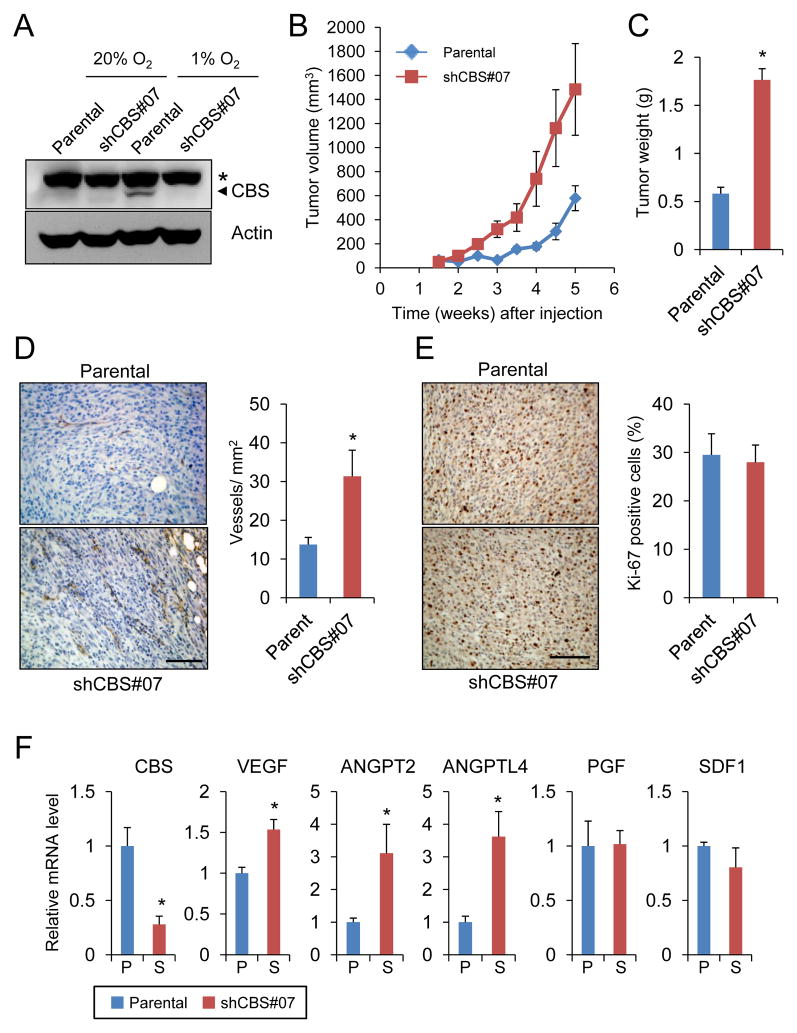

To assess the role of CBS in glioma tumorigenesis, we established a U87-MG subclone, designated shCBS#07 that stably expressed an shRNA designed to inhibit CBS expression, which is induced by hypoxia in U87-MG cells (9). Thus, parental U87-MG and shCBS#07 cells were exposed to 20% or 1% O2 for 3 days and CBS expression was analyzed by immunoblot assay. CBS expression was induced by hypoxia in parental cells but not in the shCBS#07 subclone (Fig. 1A).

Figure 1.

Effect of CBS knockdown on the growth of U87-MG tumor xenografts. (A) U87-MG subclones were exposed to 1% or 20% O2 for 3 days and immunoblot assays were performed to analyze CBS and actin protein levels. Asterisk indicates a non-specific band and arrowhead points to CBS-specific band. (B) Parental and CBS knockdown U87-MG cells were injected subcutaneously into the flank of SCID mice and tumor volume was determined (mean ± SEM, n = 4) by serial caliper measurements. (C) Tumors were harvested at 5.5 weeks after injection and weight was determined (mean ± SEM, n = 4); *p < 0.05 vs parental. (D) Anti-CD31 immunohistochemistry and hematoxylin counterstaining were performed (left panel; scale bar = 100 μm) and blood vessel density in tumor sections was determined (right panel; mean ± SEM, n = 8); *p < 0.05. (E) Anti Ki-67 immunohistochemistry and hematoxylin counterstaining were performed (left panel; scale bar = 100 μm) to quantify Ki-67+ proliferating cells in tumors derived from injection of parental U87-MG cells and shCBS#07 subclone (right panel; mean ± SEM, n = 8). (F) Levels of mRNAs encoding CBS and angiogenic growth factors in harvested tumor samples were determined by reverse transcription and quantitative real-time PCR (RT-qPCR) and normalized to the parental samples (mean ± SEM, n = 4); *p < 0.05.

To evaluate the role of CBS in tumorigenesis, parental U87-MG and shCBS#07 cells were subcutaneously injected into the flank of severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) mice. Whereas the latency period before rapid tumor growth after injection of parental U87-MG cells was 3 weeks, rapid tumor growth was observed less than 2 weeks after injection of the shCBS#07 subclone. When the tumors were harvested 5 weeks after injection, the parental tumors had reached a mean volume of 600 mm3 and weight of 0.5 g, whereas the shCBS#07 tumors were 1500 mm3 and 1.7 g (Fig. 1B, C). Immunohistochemical analysis of tumor sections was performed with an antibody against CD31 and the number of CD31+ blood vessels was counted. As shown in Fig. 1D, shCBS#07 tumors had a significantly higher vessel density than parental tumors. Ki-67 immunohistochemistry revealed that there was no significant difference in cell proliferation between parental and shCBS#07 tumors (Fig. 1E), which was consistent with the similar tumor growth rates by the end of the experiment (Fig. 1B). Consistent with the increased vessel density, the expression of mRNAs encoding three angiogenic growth factors, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), angiopoietin 2, and angiopoietin-like 4 (ANGPTL4), was significantly increased in shCBS#07 tumors as compared to parental tumors, whereas expression of placental growth factor (PGF) and stromal-derived factor 1 (SDF1) was similar between subclones (Fig. 1F).

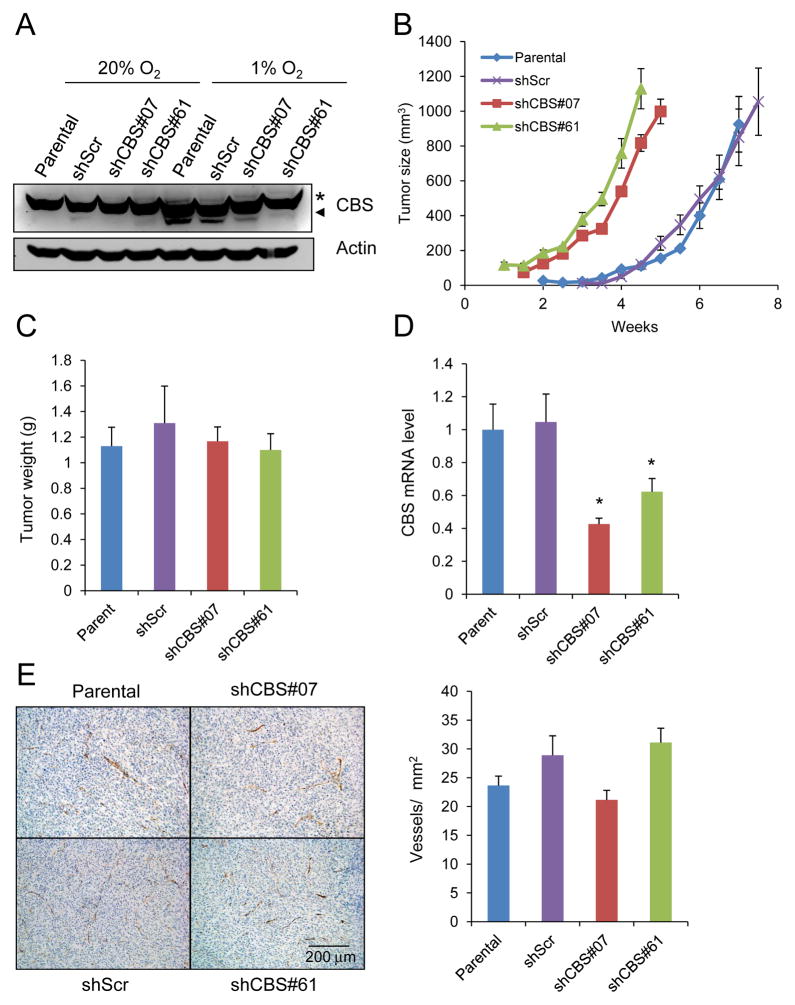

In order to establish that the difference in tumorigenesis between the cell lines was specifically due to CBS loss of function, two additional subclones were generated (Fig. 2A). One subclone expressed an shRNA that targeted a different sequence in CBS mRNA (shCBS#61). The other subclone expressed a scrambled shRNA sequence that did not target CBS (shScr). There was no significant difference between subclones with respect to in vitro cell proliferation at either 20% or 1% O2 (Supplementary Fig. S1). We hypothesized that the increased angiogenesis in shCBS#07 tumors was a reflection of their more advanced growth due to the decreased latency period. To test this hypothesis, rather than harvesting tumors at the same time point, tumors were harvested when they reached a volume of 1000 mm3 (Fig. 2B, C). As in the previous experiment, after subcutaneous injection the subclones with CBS expression (parental and shScr) showed a latency period of 3 weeks and reached 1000 mm3 by 7 to 7.5 weeks after injection, whereas the subclones with CBS loss of function showed a latency period of less than 2 weeks and reached 1000 mm3 within 4.5 to 5 weeks; however, by the end of the experiment, the growth rates were identical in all four subclones (Fig. 2B). The tumors were harvested and analyzed by RT-qPCR, which demonstrated a significant decrease in CBS mRNA levels in shCBS#07 and shCBS#61 tumors compared to parental and shScr tumors (Fig. 2D). Although shCBS#07 tumors had higher vessel density than parental U87-MG cells when they were harvested at the same time point (Fig. 1D), parental, shScr, shCBS#07 and shCBS#61 tumors had similar vessel density when they were harvested at the same tumor volume (Fig. 2E). The parallel late-stage tumor growth curves (Fig. 2B) and absence of any difference in Ki-67 staining (Fig. 1E) suggest that the tumor promoting effect of CBS deficiency occurs early in tumorigenesis.

Figure 2.

Analysis of 1000-mm3 tumor xenografts derived from subcutaneous injection of U87-MG subclones. (A) Immunoblot assays were performed to analyze CBS and actin protein levels in lysates of U87-MG subclones that were cultured under 1% or 20% O2 for 3 days. Asterisk indicates a non-specific band and arrowhead points to CBS-specific band. (B) U87-MG subclones were injected subcutaneously into the flank of SCID mice and tumors were harvested when they reached a volume of 1000 mm3 (mean ± SEM, n = 4). (C) The harvested tumors were weighed (mean ± SEM, n = 4). (D) CBS mRNA levels in tumor samples were determined by RT-qPCR and normalized to the parental samples (mean ± SEM, n = 4); *p < 0.05 vs shScr. (E) Anti-CD31 immunohistochemistry and hematoxylin counterstaining of tumor sections (left panel; scale bar = 0.2 mm) were performed to determine blood vessel density (right panel; mean ± SEM, n = 8).

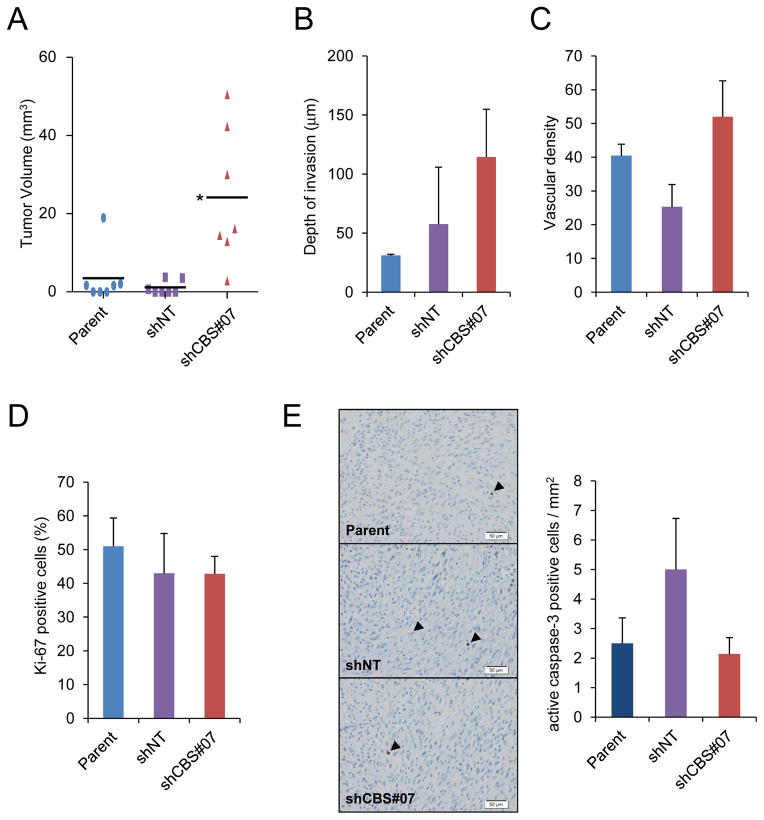

CBS loss of function increases tumor incidence and volume after orthotopic transplantation

Because the consequences of gene knockdown in a mouse model of astrocytoma were found to differ dramatically after subcutaneous as compared to orthotopic transplantation (12), we performed orthotopic injection of parental U87-MG and shCBS#07 cells as well as a subclone expressing a non-targeting shRNA (shNT). Five weeks after injection of 1×105 cells into the brains of SCID mice, the brains were harvested and scored for the presence and volume of tumor tissue. All 7 mice that were injected with shCBS#07 cells formed tumors, whereas tumors formed in only 4 out of 7 mice injected with parental cells and 3 out of 7 mice injected with shNT cells. Consistent with data from the subcutaneous injection model, the mean volume of shCBS#07 tumors was significantly greater than parental tumors (Fig. 3A), whereas there was no significant difference with respect to depth of invasion into the brain (Fig. 3B) or vascular density (Fig. 3C). In addition, by the end of the experiment there was no significant difference with respect to proliferation, as determined by Ki-67 immunohistochemistry (Fig. 3D), or apoptosis, as determined by immunohistochemistry using an antibody specific for cleaved caspase 3, which revealed low levels of apoptosis in all tumor sections (Fig. 3E).

Figure 3.

Analysis of orthotopic tumors. (A) Tumor volume was measured 5 weeks after stereotactic injection of U87-MG subclones into the brains of SCID mice (bar = mean, n = 7); *p < 0.05 vs shNT. (B) Depth of invasion was measured from brain tumor sections (mean ± SEM, n = 3–6). (C) Anti-CD105 immunohistochemistry was performed and vessel density in tumor sections was determined (mean ± SEM, n = 6–14). (D) Anti-Ki-67 immunohistochemistry was performed and Ki-67+ cells were counted (mean ± SEM, n = 3–7). (E) Immunohistochemistry was performed (left panel; scale bar = 50 μm) with an antibody that selectively recognizes cleaved (active) caspase-3 (arrowheads). Positive cells were counted (right panel; mean ± SEM, n = 3–7).

Because the major difference observed was with respect to tumor incidence, we repeated the experiment, but this time injected a 10-fold lower number of cells (i.e. 1×104). Again, tumors formed in all 7 mice injected with shCBS#07, whereas tumors formed in only 5 out of 7 mice injected with shNT cells, and 6 out of 7 mice injected with parental U87-MG cells. We also assessed tumor volume, depth of invasion, vascular density, cell proliferation, and cell apoptosis and again observed a significant difference only with respect to tumor volume (Supplementary Fig. S2). Taken together, the xenotopic and orthotopic models indicate that CBS loss of function increases tumorigenicity.

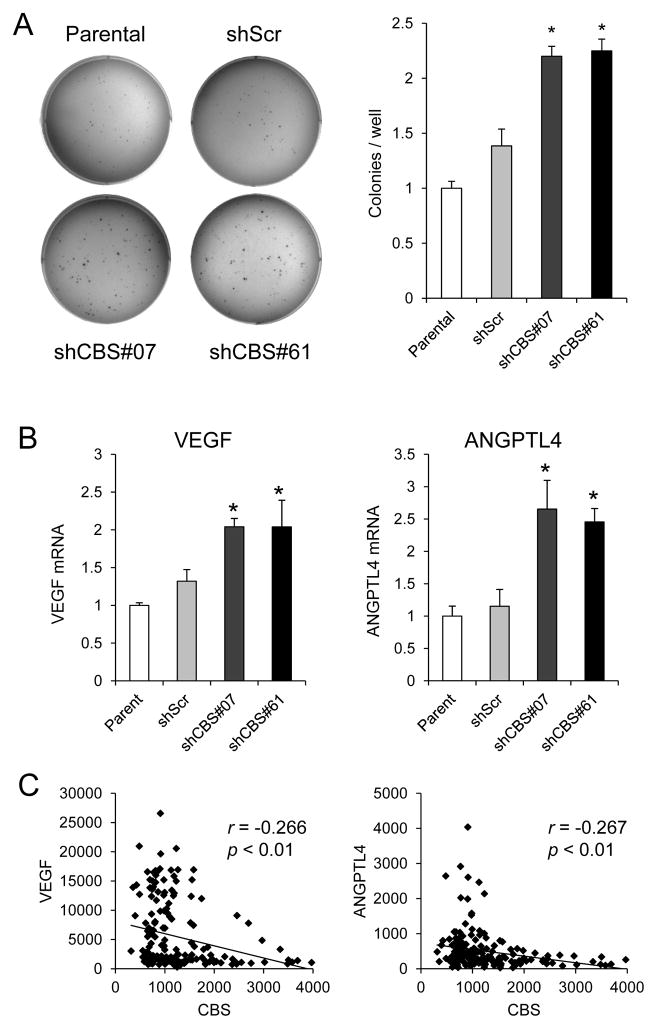

CBS loss of function increases anchorage-independent cell growth

Immediately after injection, cancer cells are in an anchorage-independent state in which they are detached from extracellular matrix, which can trigger a form of programmed cell death known as anoikis (13). Anchorage-independent cell growth can be investigated by analyzing colony formation in soft agar. As shown in Fig. 4A, shCBS#07 and shCBS#61 cells formed a significantly greater number of colonies in soft agar as compared to parental U87-MG or shScr cells. ANGPTL4 and VEGF have been reported to promote anchorage independent growth and protect against anoikis in cancer cells (14, 15). VEGF and ANGPTL4 mRNA levels were significantly higher in the two CBS-deficient subclones than in parental and shScr cells (Fig. 4B). To determine the clinical relevance of these observations, we investigated whether CBS mRNA levels were correlated with VEGF or ANGPTL4 mRNA levels in 180 primary patient-derived gliomas by interrogating a microarray dataset in the GEO database (GSE4290) (7). As shown in Fig. 4C, CBS mRNA levels showed negative correlations with VEGF and ANGPTL4 mRNA levels that were statistically significant (p < 0.01). These results suggest that CBS expression negatively regulates VEGF and ANGPTL4 expression in human glioma.

Figure 4.

Analysis of colony formation in soft agar and gene expression in U87-MG subclones and patient-derived glioma tissue. (A) U87-MG subclones were grown in soft agar (left panel), colonies were counted, and normalized to the parental cells (right panel; mean ± SEM, n = 6); *p < 0.05 vs shScr. (B) VEGF (left panel) and ANGPTL4 (right panel) mRNA expression in U87-MG subclones cultured at 20% O2 were determined by RT-qPCR and normalized to the parental samples (mean ± S.E.M., n = 3); *p < 0.05 vs shScr. (C) The signal intensity for CBS vs VEGF (left panel) or CBS vs ANGPTL4 (right panel) mRNA microarray data obtained from 180 patient-derived glioma samples in the GEO database (GSE4290) was plotted. For each plot, the Pearson r statistic and derived p value are shown.

CBS deficiency increases HIF-2α expression and anchorage-independent cell growth

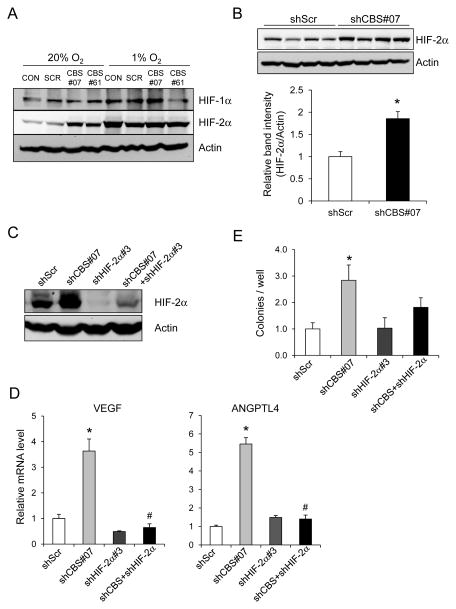

Expression of ANGPTL4 (16) and VEGF (17) is regulated by HIFs in cancer cells and H2S has been reported to inhibit HIF-1α protein expression in vitro (18, 19), suggesting that CBS loss of function might increase HIF-dependent ANGPTL4 and VEGF expression. To test this hypothesis, we analyzed HIF-1α and HIF-2α protein levels in U87-MG subclones that were exposed to 20% or 1% O2 for 3 days. Immunoblot assays revealed no consistent difference in HIF-1α protein levels between control and CBS-deficient subclones, whereas HIF-2α protein levels were increased in CBS-deficient subclones under non-hypoxic conditions (Fig. 5A). Densitometric analysis of HIF-2α immunoblot band intensity in lysates prepared from 5 replicate cultures of shScr and shCBS#07 subclones incubated at 20% O2 confirmed that HIF-2α levels were significantly higher in shCBS#07 cells (Fig. 5B). In contrast, HIF-2α mRNA levels were not increased in CBS-deficient subclones (Supplementary Fig. S3), indicating an effect on HIF-2α protein synthesis or stability.

Figure 5.

Analysis of HIF-2α expression in U87-MG subclones. (A) Immunoblot assays were performed to analyze HIF-1α, HIF-2α and actin protein levels in lysates from U87-MG subclones that were exposed to 1% or 20% O2 for 3 days. (B) Immunoblot assays were performed to analyze HIF-2α expression in five replicate cultures of shScr and shCBS#07 subclones cultured at 20% O2 for 3 days (top panel). Densitometry was performed and the ratio of HIF-2α/actin band intensity was determined (bottom panel; mean ± SEM, n = 4); *p < 0.05. (C) Immunoblot assays were performed to analyze HIF-2α levels in shScr, shCBS#07, shHIF-2α#3, and shCBS#07+HIF-2α#3 subclones cultured under 20% O2. (D) VEGF (left panel) and ANGPTL4 (right panel) mRNA levels in shScr, shCBS#07, shHIF-2α#3, and shCBS#07+shHIF-2α#3 subclones cultured under 20% O2 were determined by RT-qPCR and normalized to shScr (mean ± SEM, n = 3); *p <0.05 vs shScr; #p < 0.05 vs shCBS#07. (E) Colony formation ability of U87-MG subclones was measured by soft agar assay and normalized to shScr (mean ± SEM, n = 4); *p < 0.05 vs shScr.

We next stably transfected parental U87-MG cells and the shCBS#07 subclone with an shRNA targeting HIF-2α (shHIF-2α#3), which efficiently reduced HIF-2α protein levels in both subclones (Fig. 5C). VEGF and ANGPTL4 mRNA levels were significantly reduced in these HIF-2α-deficient subclones (Fig. 5D). Soft agar assays revealed that the increase in colony formation associated with CBS deficiency was lost when HIF-2α expression was also silenced (Fig. 5E). Taken together, the data presented in Fig. 5 indicate that decreased CBS expression results in increased HIF-2α protein levels, which stimulate ANGPTL4 and VEGF expression, leading to increased anchorage-independent growth, thereby providing a potential explanation for the increased tumorigenicity of the CBS-deficient subclones.

Discussion

In this study, we found that shRNA-dependent inhibition of CBS in U87-MG glioma cells increased tumor xenograft growth by decreasing the latency period prior to exponential growth. CBS also increased the incidence and volume of brain tumors after orthotopic injection, without affecting tumor cell proliferation, which is also consistent with a decreased latency period. CBS deficiency did not affect the in vitro proliferation of adherent U87-MG cells, but significantly increased colony formation in soft agar assays of anchorage-independent growth. Taken together, the results of both in vivo and in vitro assays suggest that reduced CBS expression promotes glioma tumorigenesis. Here, we use the term tumorigenesis to emphasize that the effect of CBS deficiency occurs at an early step in the process of tumor formation and is not due to intrinsic differences in cell proliferation. Tumorigenesis should be distinguished from carcinogenesis, the process of mutation and selection, which does not occur when U87-MG cells are transplanted into mice.

Molecular analyses indicated that CBS knockdown was associated with increased HIF-2α protein expression and HIF-2α-dependent expression of ANGPTL4 and VEGF, which have been shown to protect against anoikis in other cancer cell lines (14, 15), providing a potential, but currently unproven, mechanism for the increased tumorigenicity of CBS deficient subclones, although increased HIF-2α protein levels may have affected the expression of multiple HIF target genes (20). It should be noted that although expression of the ANGPTL4 and VEGF genes is regulated by both HIF-1 and HIF-2, increased expression of these genes in CBS-deficient U87-MG cells appears to be due specifically to increased HIF-2α protein levels.

Two prior studies demonstrated that treatment of various human cancer cell lines with H2S donors inhibited HIF-1α protein expression, but one group implicated changes in HIF-1α and HIF-2α stability (18), whereas the other group reported effects on HIF-1α synthesis (19), and it is uncertain whether data obtained by pharmacological treatment of cell lines is physiologically relevant. If CBS loss of function in U87-MG cells was associated with changes in H2S production, it is not clear why only HIF-2α expression was affected by CBS knockdown, although it should be noted that CBS activity impacts on other metabolic pathways including those affecting protein and DNA methylation (1, 21). Thus, extensive additional studies may be required to resolve this issue.

CBS expression was negatively correlated with ANGPTL4 and VEGF mRNA levels in 180 patient-derived glioma samples, which suggests that the findings from our analysis of U87-MG cells are clinically relevant. Further studies are required to determine whether CBS expression in gliomas is repressed by promoter hypermethylation as reported for gastric carcinoma (3).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to: Karen Padgett (Novus Biologicals) for generously providing antibodies against HIF-2α and Ki-67; Maimon Hubbi (Johns Hopkins University Scool of Medicine) for helpful discussions; and the Histopathology and Immunohistochemistry Core of the NYU Cancer Institute.

Grant Support

We thank Maimon Hubbi (Johns Hopkins University) for helpful discussions and Karen Padgett (Novus Biologicals) for providing HIF-2α antibody. This work was supported in part by the Japan Science and Technology Agency Exploratory Research for Advanced Technology and by funds from the Johns Hopkins Institute for Cell Engineering. The Histopathology and Immunohistochemistry Core of the NYU Cancer Institute is supported in part by NIH grant P30-CA016087. G.L.S. is an American Cancer Society Research Professor and the C. Michael Armstrong Professor at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine.

Footnotes

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest: there are no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Kajimura M, Fukuda R, Bateman RM, Yamamoto T, Suematsu M. Interactions of multiple gas-transducing systems: hallmarks and uncertainties of CO, NO, and H2S gas biology. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2010;13:157–92. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.2657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Szabo C, Coletta C, Chao C, Modis K, Szczesny B, Papapetropoulos A, et al. Tumor-derived hydrogen sulfide, produced by cystathionine β-synthase, stimulates bioenergetics, cell proliferation, and angiogenesis in colon cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:12474–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1306241110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhao H, Li Q, Wang J, Su W, Ng KM, Qiu T, et al. Frequent epigenetic silencing of the folate-metabolizing gene cystathionine β–synthase in gastrointestinal cancer. PLoS One. 2012;7:e49683. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0049683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morikawa T, Kajimura M, Nakamura T, Hishiki T, Nakanishi T, Yukutake Y, et al. Hypoxic regulation of the cerebral microcirculation is mediated by a carbon monoxide-sensitive hydrogen sulfide pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:1293–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1119658109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang Z, Liu D, Wang F, Zhang Q, Du Z, Zhan J, et al. L-cysteine promotes the proliferation and differentiation of neural stem cells via the CBS/H2S pathway. Neuroscience. 2013;237:106–17. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2012.12.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li Z, Bao S, Wu Q, Wang H, Eyler C, Sathornsumetee S, et al. Hypoxia-inducible factors regulate the tumorigenic capacity of glioma stem cells. Cancer Cell. 2009;15:501–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Seidel S, Garvalov BK, Wirta V, von Stechow L, Schänzer A, Meletis K, et al. A hypoxic niche regulates glioblastoma stem cells through hypoxia-inducible factor 2α. Brain. 2010;133:983–95. doi: 10.1093/brain/awq042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pontén J, Macintyre EH. Long term culture of normal and neoplastic human glia. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand. 1968;74:465–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1968.tb03502.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Takano N, Peng YJ, Kumar GK, Luo W, Hu H, Shimoda LA, et al. Hypoxia-inducible factors regulate human and rat cystathionine β-synthase gene expression. Biochem J. 2014;458:203–11. doi: 10.1042/BJ20131350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mendez O, Zavadil J, Esencay M, Lukyanov Y, Santovasi D, Wang SC, et al. Knock down of HIF-1α in glioma cells reduces migration in vitro and invasion in vivo and impairs their ability to form tumor spheres. Mol Cancer. 2010;9:133. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-9-133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sun L, Hui AM, Su Q, Vortmeyer A, Kotliarov Y, Pastorino S, et al. Neuronal and glioma-derived stem cell factor induces angiogenesis within the brain. Cancer Cell. 2006;9:287–300. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blouw B, Song H, Tihan T, Bosze J, Ferrara N, Gerber HP, et al. The hypoxic response of tumors is dependent on their microenvironment. Cancer Cell. 2003;4:133–46. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00194-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Paoli P, Giannoni E, Chiarugi P. Anoikis molecular pathways and its role in cancer progression. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1833:3481–98. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2013.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhu P, Tan MJ, Huang RL, Tan CK, Chong HC, Pal M, et al. Angiopoietin-like 4 protein elevates the prosurvival intracellular O2(−):H2O2 ratio and confers anoikis resistance to tumors. Cancer Cell. 2011;19:401–15. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Desai S, Laskar S, Pandey BN. Autocrine IL-8 and VEGF mediate epithelial-mesenchymal transition and invasiveness via p38/JNK-ATF-2 signalling in A549 lung cancer cells. Cell Signal. 2013;25:1780–91. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2013.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang H, Wong CC, Wei H, Gilkes DM, Korangath P, Chaturvedi P, et al. HIF-1-dependent expression of angiopoietin-like 4 and L1CAM mediates vascular metastasis of hypoxic breast cancer cells to the lungs. Oncogene. 2012;31:1757–70. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 17.Forsythe JA, Jiang BH, Iyer NV, Agani F, Leung SW, Koos RD, et al. Activation of vascular endothelial growth factor gene transcription by hypoxia-inducible factor 1. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:4604–13. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.9.4604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kai S, Tanaka T, Daijo H, Harada H, Kishimoto S, Suzuki K, et al. Hydrogen sulfide inhibits hypoxia- but not anoxia-induced hypoxia-inducible factor 1 activation in a von Hippel-Lindau- and mitochondria-dependent manner. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2012;16:203–16. doi: 10.1089/ars.2011.3882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wu B, Teng H, Yang G, Wu L, Wang R. Hydrogen sulfide inhibits the translational expression of hypoxia-inducible factor-1α. Br J Pharmacol. 2012;167:1492–505. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2012.02113.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Semenza GL. Hypoxia-inducible factors: mediators of cancer progression and targets for cancer therapy. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2012;33(4):207–14. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2012.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yamamoto T, Takano N, Ishiwata K, Ohmura M, Nagahata Y, Matsuura T, et al. Reduced methylation of PFKFB3 in cancer cells shunts glucose towards the pentose phosphate pathway. Nat Commun. 2014;5:3480. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.