Abstract

Mice that were transgenic for a T-cell receptor (TCR) specific for ovalbumin peptide323-339 (DO11.10) were able to survive an infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis for approximately 80 days. This limited early control of infection was associated with gamma interferon production, inducible nitric oxide synthase expression within the lung, and an influx of clonotypic lymphocytes. The control of M. tuberculosis was lost in DO11.10 mice bred in a rag mutant background, demonstrating that the immune responsiveness was recombinase dependent and likely to be associated with the expression of an alternative α TCR by DO11.10 mice. A characterization of the antigen specificity in DO11.10 TCR transgenic mice demonstrated that the specificity was limited and dominated by the 26-kDa (Rv1411c) lipoprotein of M. tuberculosis. This study identifies this lipoprotein as an important and potent inducer of protective T cells within the lungs of mice infected with M. tuberculosis and therefore as a possible target for vaccination.

The control of an infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis requires multiple overlying immune responses that result in the generation of protective CD4 T cells, gamma interferon (IFN-γ) production, and a cessation of mycobacterial growth within the lungs (10). These overlapping immune mechanisms serve to obscure the role that any single antigen-specific response may play in controlling mycobacterial disease. This is particularly important because current screening strategies employ antigen-specific IFN-γ production for the identification of putative protective antigens, despite the fact that several antigens can have deleterious effects on the expression of protective immunity (13, 23, 32).

To determine the minimal requirements for the control of an infection with M. tuberculosis, we used a T-cell receptor (TCR) transgenic mouse, DO11.10, in which the antigen specificity of the TCRs is highly restricted. DO11.10 mice that have been backcrossed onto a Rag−/− background (DO11.10<rag>) are unable to initiate recombination events, resulting in the exclusive expression of the clonotypic α and β TCR chains (17, 19) and the recognition of a single peptide of ovalbumin (peptide323-339) in the context of I-Ad (21). In contrast, in the presence of rag genes DO11.10 mice can, fortuitously, undergo a limited alternative TCR α chain rearrangement, resulting in the generation of a restricted TCR repertoire against antigens other than that which the mice were originally engineered to recognize (17, 26).

The use of DO11.10 TCR transgenic mice (21), which can undergo a limited alternative TCR rearrangement, allowed us to uncover a restricted CD4-T-cell response against the mycobacterial 26-kDa lipoprotein, Rv1411c. In vitro culturing of lung cells from M. tuberculosis-infected DO11.10 TCR transgenic mice with the 26-kDa lipoprotein resulted in antigen-specific IFN-γ production by CD4 T cells that expressed the clonotypic TCR. This very limited T-cell response was essential for the control of bacterial growth within the lungs after an aerosol challenge with M. tuberculosis but was insufficient to provide long-term survival. The data presented here demonstrate that inducing a limited Th1 CD4-T-cell response in the lungs, resulting in macrophage activation, is insufficient for survival from this chronic disease.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice.

Specific-pathogen-free female BALB/c and SCID (BALB/cByJSmn-Prkdcscid/j) mice were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, Maine). Male and female mice (in the BALB/c background) that were transgenic for the DO11.10 αβ TCR (21) were a kind gift from Kenneth Murphy (Washington University, St. Louis, Mo.), and DO11.10<rag> mice were a gift from Thomas Mitchell (National Jewish Medical and Research Center, Denver, Colo.) (19). Mice were bred in-house under barrier conditions at Colorado State University (CSU). Mice of 6 to 8 weeks of age were selected for the study. These animals were kept in biosafety level 3 biohazard facilities throughout the experiments and were maintained with sterile water, bedding, and mouse chow. The specific-pathogen-free nature of the mouse colonies was demonstrated by testing sentinel animals. These were shown to be negative for 12 known mouse pathogens. The CSU Animal Care and Use Committee approved all animal procedures performed at CSU.

Bacterial infections.

M. tuberculosis Erdman was originally obtained from the Trudeau Mycobacteria Collection (Saranac Lake, N.Y.) and was grown in Proskauer-Beck medium (25) to mid-log phase, divided into aliquots, and frozen at −70°C. Mice were exposed to a particle mist of M. tuberculosis Erdman by use of an aerosol generation device (Glas-Col, Terre Haute, Ind.) (25). The numbers of viable bacteria in the lungs were determined by plating whole organ homogenates onto 7H11 agar (25) and counting the bacterial colonies after 21 days of incubation at 37°C. The data are expressed as the mean log10 numbers of bacteria recovered per organ from four animals. The results are representative of three individual experiments. For each experiment, the initial inoculum delivered to the mice was determined by homogenizing and plating the lungs of four individual mice 1 day after the aerosol exposure.

Histological analysis and immunohistochemistry.

After being harvested, the right caudal lung lobe of each mouse was inflated with, and stored in, 10% neutral buffered formalin. Tissues were prepared and sectioned routinely for light microscopy to allow for the maximum surface area of each lobe to be seen. Consecutive sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin and examined by a veterinary pathologist with no prior knowledge of sample identification. The figures shown are representative of the experimental groups. Sections from formalin-fixed tissue were deparaffinized and placed in 10 mM sodium citrate buffer (pH 6), followed by pressure cooking for exactly 1 min (5). After being blocked for 20 min in a 1% H2O2 solution, the slides were incubated with an appropriately diluted polyclonal rabbit anti-mouse NOS2 antibody (Genzyme-Virotech, Russelsheim, Germany) in Tris-buffered saline-10% fetal calf serum for 30 min in a humid chamber. An appropriately diluted goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG)-peroxidase (Dianova, Hamburg, Germany) was used as a bridging antibody, and a diluted rabbit anti-goat IgG-peroxidase (Dianova) was used as a tertiary antibody in sequential incubations of 30 min each. Development was performed with DAB (Sigma) and urea superoxide (Sigma), and hemalum was used to counterstain the slides.

Reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR).

A portion of lung tissue was suspended in Ultraspec (Cinna/Biotecx, Friendswood, Tex.), homogenized, and frozen rapidly for storage at −70°C. The total cellular RNA was extracted and reverse transcribed with murine Moloney leukemia virus reverse transcriptase (Life Technologies, Grand Island, N.Y.). A PCR was performed with specific primers for IFN-γ and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS). The PCR product was Southern blotted and probed with specific, labeled oligonucleotides, and the blots were developed by the use of an enhanced chemiluminescence kit (ECL; Amersham, Arlington Heights, Ill.). The hypoxanthine phosphoribosyltransferase housekeeping gene was also amplified for each sample and was used to confirm that equivalent amounts of readable RNA were present in all samples (7).

Lung cell cultures.

Mice were infected via the aerosol route with 102 viable M. tuberculosis cells, and the lungs were harvested after 30 or 50 days of infection. The lungs were inflated via the heart with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 50 U of heparin (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.)/ml. Lungs from individual mice were finely teased apart and incubated with collagenase A (type XI) (0.7 mg/ml; Sigma) and type IV bovine pancreatic DNase (30 μg/ml; Sigma) at 37°C for 30 min to digest the lung tissue. Cells were passed through a mesh sieve, washed once, and resuspended at 5 × 106 cells/ml prior to incubation with viable M. tuberculosis cells (5 × 105 bacteria/well), ovalbumin (10 μg/ml; Sigma), or individual antigens (16, 19, 26/27, 30 to 32, and 38 kDa) of M. tuberculosis H37Rv (10 μg/ml). After 5 days of incubation at 37°C with 5% CO2, the plates were frozen at −70°C.

IFN-γ ELISA and Greiss reaction.

Supernatants were assayed for the presence of IFN-γ by an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). The antibodies used were purchased from Pharmingen (San Diego, Calif.). Briefly, the primary antibody (clone R4-6A2) was incubated overnight in 96-well flat-bottomed Immulon 2 plates in a carbonated coating buffer. Excess antibody was washed away with PBS-Tween 20 (PBS-T). The wells were blocked with 3% bovine serum albumin in PBS-T. The samples were dispensed in duplicate into the wells. The presence of the cytokine was detected by the addition of a secondary biotinylated antibody (clone XMG1.2), followed by avidin peroxidase and a substrate (2,2′-azino-bis[3-ethylbenz-thiazoline-6-sulfonic acid]). The supernatants were also incubated in duplicate with Greiss reagent (1% sulfanilamide, 0.1% naphthylethylene diamine dihydrochloride, 2.5% H3PO4) to determine the nitrate concentration.

Flow cytometry.

A single-cell suspension was prepared from lung tissue as described previously (29). Cells from each individual mouse were incubated with a specific antibody (25 μg/ml) for 30 min at 4°C in the dark. After two washes in D-RPMI lacking biotin and phenol red (Irvine Scientific, Santa Ana, Calif.), the cells were analyzed on a Becton Dickinson FACSCalibur instrument. The cell surface markers analyzed were a phycoerythrin-pan-NK marker (clone DX5), peridinin chlorophyll protein (PerCP)-CD4 (clone RMA4-5), allophycocyanin (APC)-βTCR (clone H57-597), and an APC-KJ1-26 clonotype-specific antibody. Antibodies against CD4, DX5, βTCR, and the appropriate isotype antibodies were purchased from Pharmingen. The IgG1 isotype and KJ1-26 antibodies were purchased from Caltag Laboratories (Burlingame, Calif.). Data were acquired on a Becton Dickinson FACSCalibur instrument and analyzed with CellQuest software.

Intracellular cytokine staining.

The measurement of intracellular IFN-γ was carried out by preincubating lung cells with 0.1 μg of anti-CD3ɛ antibody (clone 145-2C11)/ml and 1 μg of anti-CD28 antibody (clone 37.51)/ml in the presence of 3 μM monensin for 4 h at 37°C in 5% CO2. The cells were stained with a phycoerythrin-anti-DX5, PerCP-anti-CD4, APC-anti-APC-βTCR, or APC-anti-KJ1-26 antibody prior to a permeabilization step according to the manufacturer's instructions (Fix/Perm kit; Pharmingen). A fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated anti-IFN-γ antibody (clone XMG1.2) or an IgG1 isotype control antibody was incubated with the cells for 30 min, washed twice, and resuspended in D-RPMI prior to analysis.

Antigen-specific IFN-γ production.

Bone-marrow-derived macrophages were prepared as described previously (30) and pulsed overnight with antigens from M. tuberculosis (16 kDa, 26 kDa, 27 kDa, or cell wall) at a final concentration of 1 μg/ml. Lung cells were isolated (as described above) from DO11.10 or BALB/c mice that had been infected 30 days previously with M. tuberculosis and were cultured at a concentration of 2 × 106 cells/ml with antigen-pulsed macrophages for 24 h. An anti-CD28 antibody (clone 37.51) (1 μg/ml) and 3 μM monensin were added 4 h prior to analysis, and the cells were analyzed by flow cytometry as previously described.

Antigen preparation.

Mycobacterial antigen preparations (the cell wall [CW], sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS]-soluble cell wall proteins [SCWPs], culture filtrate proteins [CFPs], and the 30- to 32-kDa Ag85 complex) were prepared from a log-phase culture of M. tuberculosis strain H37Rv grown in glycerol-alanine salts medium (27) as previously described (1, 14, 16).

The fractionation of cell wall proteins was performed by preparative SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) and electroelution. Specifically, the cell wall subcellular fraction was washed several times with 10 mM NH4CO3. An aliquot (300 mg of wet weight) of crude cell wall was suspended in 500 μl of a solution containing 0.06 M Tris-HCl (pH 6.8), 10% glycerol, 2% SDS, 5% β-mercaptoethanol, 0.01% bromophenol blue, and 4 M urea and heated at 100°C for 4 min. The insoluble material was removed from the suspension by centrifugation at 14,000 × g for 5 min, and the supernatant was applied to a 16- by 20-cm preparative SDS-15% polyacrylamide gel. The proteins were resolved and electroeluted as previously described (8).

The 16-kDa α-crystallin homologue of M. tuberculosis was purified from the cell wall by extraction of the cell wall pellet with PBS (0.01 M sodium phosphate, pH 7.4, and 0.15 M sodium chloride) and 1% N-octylthioglucoside, followed by isoelectric separation on a Rotofor apparatus (Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif.) as described previously (8). Fractions containing the 16-kDa α-crystallin protein were pooled and dialyzed against 0.01 M ammonium bicarbonate. Purification of the 16-kDa protein was achieved by using a Sephacryl S-200 column with a size exclusion buffer of 0.02 M Tris-HCl (pH 7.6), 0.15 M sodium chloride, 3 M urea, and 0.1% N-octylthioglucoside. The purified 16-kDa protein was concentrated and exchanged into 0.01 M ammonium bicarbonate by ultrafiltration.

Purification of the 26/27-kDa protein complex, the 19-kDa lipoprotein, and the 38-kDa PhoS1 protein was achieved by preparative SDS-PAGE and electroelution of the Triton X-114-soluble proteins of M. tuberculosis. The TX-114-soluble protein fraction was generated as described previously (11), and preparative SDS-PAGE and electroelution were performed as described for the fractionation of cell wall proteins. The 26/27-kDa protein fraction was further separated by concanavalin A (ConA) affinity chromatography. Specifically, the 26/27-kDa protein fraction obtained by preparative SDS-PAGE was exchanged into ConA binding buffer (0.05 M potassium phosphate [pH 5.7], 0.5 M sodium chloride, and 1.0 mM [each] calcium chloride, manganese chloride, magnesium chloride, and dithiothreitol). ConA-conjugated Sepharose 4B beads (Sigma) were washed to remove loosely bound ConA and were equilibrated into ConA buffer. The 26/27-kDa preparation was directly applied to the beads and incubated with gentle agitation at 4°C for 2 h. The suspension was centrifuged at 1,000 × g and the supernatant was removed. The settled beads were sequentially washed with ConA binding buffer, and the washes were added to the supernatant. The protein bound to the ConA beads was removed by competition with 1 M methyl α-d-mannopyranoside in ConA binding buffer. The pooled washes and eluent were dialyzed against 0.01 M ammonium bicarbonate and then were lyophilized.

The protein concentrations of all preparations were determined by a bicinchoninic acid assay (Pierce Chemical Co.). The purity or content of individual protein fractions was determined by SDS-PAGE (15) using a 10- by 7.5-cm SDS-10% polyacrylamide gel and staining with silver nitrate (20).

Molecular identification of the 26- and 27-kDa cell envelope proteins.

The 26- and 27-kDa proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE using 4 to 12% NuPAGE bis-Tris polyacrylamide gels and morpholineethanesulfonic acid-SDS running buffer (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif.). The gels were stained with Coomassie brilliant blue R-250 (9). The desired protein bands were excised from the gel, and an in-gel digestion with modified trypsin (Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Indianapolis, Ind.) was performed (12). The resulting peptides were dried, suspended in 15 ml of 5% acetonitrile-0.1% acetic acid, and applied to a 0.2- by 50-mm C18 reversed-phase capillary high-performance liquid chromatography column (Michrom BioResources, Inc., Auburn, Calif.). The peptides were eluted with an increasing acetonitrile gradient at a flow rate of 5 μl per min by use of an Eldex MicroPro capillary solvent delivery system (Napa, Calif.). The effluent was introduced directly into a Finnigan (San Jose, Calif.) LCQ electrospray ion-trap mass spectrometer. The electrospray needle of the mass spectrometer was operated at 4 kV, with a sheath gas flow of nitrogen at 20 lb/in2 and a heated capillary temperature of 200°C. Data-dependent tandem mass spectrometry (MS) was employed to generate fragment ions of individual peptides. The most intense ion from the full MS scan was selected for fragmentation. Tandem MS was acquired for each precursor ion a maximum of two times before being placed on the dynamic exclusion list for 1 min. Ion fragmentation was achieved with 40% normalized collision energy. The data acquired from tandem MS were interrogated against the M. tuberculosis genome database (6) by using SEQUEST analysis software (31).

Statistical analysis.

Statistical significance was determined by the Student t test: data were found to be significant (P < 0.05), highly significant (P < 0.005), or not significant, as shown in the figures. Statistical analyses of multiple comparisons (Fig. 1) were performed by a one-way analysis of variance with Bonferroni's posttest correction.

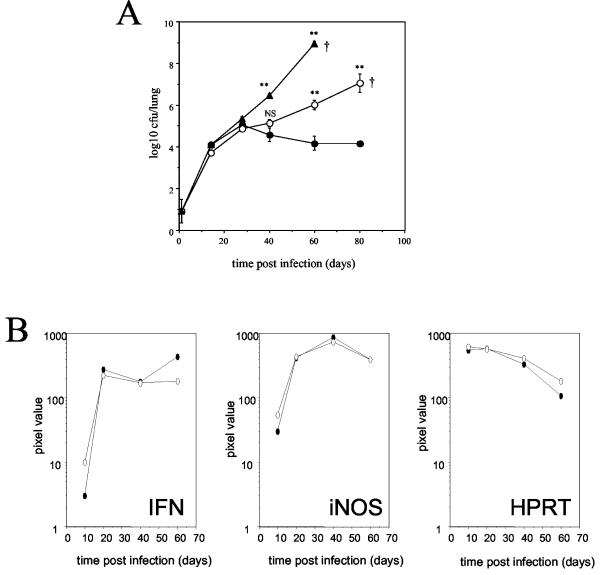

FIG. 1.

Partial ability to control pulmonary M. tuberculosis by DO11.10 TCR transgenic mice. (A) BALB/c (solid circles), DO11.10 TCR transgenic (open circles), and SCID (solid triangles) mice were given a low-dose aerosol infection with M. tuberculosis Erdman. Bacterial loads were determined and expressed as the mean log10 CFU per lung for four individual mice at each time point. The data are representative of three individual experiments †, mouse mortality. Statistical significance compared to BALB/c mice was determined by a one-way analysis of variance with Bonferroni's posttest correction. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.005. (B) Total cellular RNA was extracted and reverse transcribed, and PCR was performed with specific primers for IFN-γ and iNOS. The PCR product was Southern blotted and probed with specific, labeled oligonucleotides. The hypoxanthine phosphoribosyltransferase housekeeping gene was also amplified for each sample and used to confirm that equivalent amounts of readable RNA were present in all samples. The data are depicted as pixel values of band intensity and are representative of two independent experiments. Solid circles, BALB/c mice; open circles, DO11.10 TCR transgenic mice.

RESULTS

TCR transgenic mice are able to transiently limit bacterial growth within the lungs.

BALB/c, SCID, and DO11.10 αβ TCR transgenic mice were aerosol infected with a low dose of M. tuberculosis Erdman (Fig. 1A). All mice showed evidence of progressive bacterial growth in the lung for the first 30 days, after which the infection was brought under control and maintained at a constant level for the duration of the experiment in BALB/c mice only. The ability of the DO11.10 TCR transgenic mice to initially limit the growth of M. tuberculosis within the lung until day 40 was particularly interesting. As the infection progressed, however, the bacterial load gradually increased within the lungs, and the DO11.10 TCR transgenic mice were euthanized at approximately 80 days postinfection when they showed signs of respiratory distress. In contrast, the SCID mice showed progressive bacterial growth over a period of 60 days, at which time the mice began to show signs of distress and were euthanized. Measurements of mRNA within the lung tissue showed that DO11.10 TCR transgenic mice were capable of producing both IFN-γ and iNOS in response to an infection with M. tuberculosis at levels similar to those observed for BALB/c mice (Fig. 1B). Equivalent iNOS and IFN-γ mRNA levels were observed in the lungs of SCID mice (data not shown).

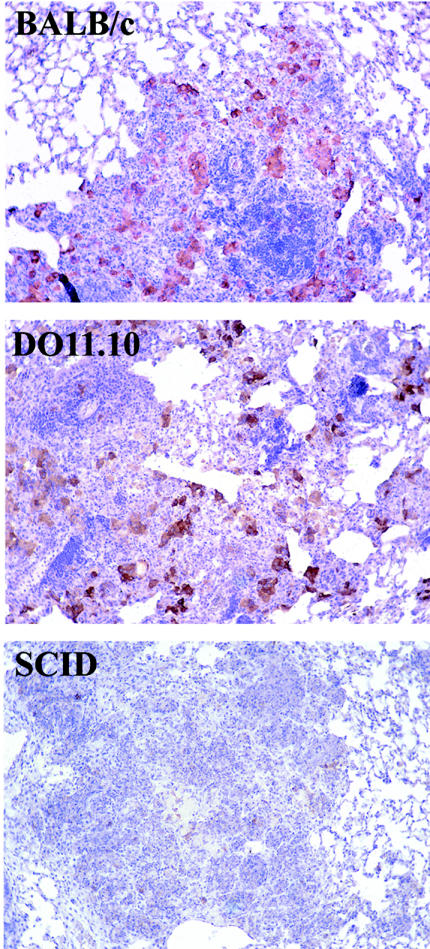

Immunohistochemical labeling of tissues for iNOS protein (Fig. 2) showed that abundant iNOS expression was apparent within the lung lesions of BALB/c and DO11.10 TCR transgenic mice after 60 days of infection with M. tuberculosis (the small lesion size made it difficult to interpret iNOS expression over the first 40 days of infection). Very little iNOS was detectable within the lung lesions of infected SCID mice. The extent of cellular infiltration into the lungs was characterized by using a hematoxylin and eosin stain (Fig. 2 and Table 1) and was graded as mild, moderate, or marked/extensive, as previously described in detail elsewhere (24). The lesions within the lungs of BALB/c mice progressed from a very mild interstitial pneumonia to a gradual accumulation of macrophages and the localization of lymphocytes around and within the macrophage lesions. After 60 days of infection, the BALB/c mice showed evidence of small, organized lung lesions consisting of many lymphocytes and foamy macrophages. In contrast, the DO11.10 TCR transgenic mice showed a more prominent interstitial pneumonia after 14 days of infection, which developed into lesions of predominantly foamy macrophages associated with lymphocytes and neutrophils. This early inflammation abated, and after 40 days of infection occasional macrophage lesions were evident, as was some perivascular lymphocyte aggregation. After 60 days of infection, the lung lesions consisted predominantly of foamy macrophages associated with neutrophils, although scattered lymphocytes were still noticeable within the lung. SCID mice showed very little evidence of lung lesion formation throughout the early stages of infection, instead presenting with a mild interstitial pneumonia until 40 days postinfection, when highly disorganized lesions, consisting mainly of macrophages and neutrophils, developed. After 60 days of infection, the majority of SCID lungs were necrotic.

FIG. 2.

Cellular composition of the infected lung. The right caudal lung lobe of each mouse was processed as described in Materials and Methods. Consecutive tissue sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin. The figures shown are representative of the experimental groups. Sections from formalin-fixed tissue were deparaffinized, incubated with appropriately diluted polyclonal rabbit anti-mouse-NOS2, and counterstained with hemalum. The presence of NOS2 is indicated by pinkish-red staining. Magnification, ×400.

TABLE 1.

Histological analysis of infected lungs

| Time of analysis (days postinfection) | Histological characteristics in mouse lungs

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| BALB/c | DO11.10 | SCID | |

| 14 | Mild small lesions, lymphocytes, macrophages | Mild small lesions, foamy macrophages, lymphocytes, some neutrophils | Mild interstitial pneumonia |

| 28 | Mild small lesions, macrophages, lymphocytes | Mild small lesions, few macrophages, interstitial pneumonia. | Mild interstitial pneumonia |

| 40 | Moderate small organized lesions, macrophages, lymphocytes | Moderate small macrophage lesions, plus neutrophils, scattered lymphocytes, interstitial pneumonia. | Extensive disorganized lesions, macrophages and neutrophils |

| 60 | Moderate small organized lesions, foamy macrophages and lymphocytes | Extensive lesions, foamy macrophages, neutrophils, scattered lymphocytes, interstitial pneumonia. | Extensive lesions, macrophages and neutrophils, necrosis |

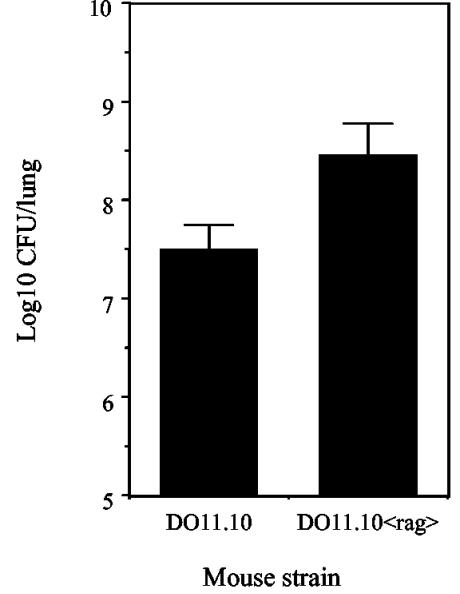

DO11.10<rag> mice fail to control an infection with M. tuberculosis.

The capacity of DO11.10 TCR transgenic mice to produce IFN-γ in response to an infection with M. tuberculosis suggested that T cells specific for a single ovalbumin peptide could also respond to antigens from M. tuberculosis. A BLAST search of the M. tuberculosis genome (http://genolist.pasteur.fr/Tuberculist), however, demonstrated no sequence homology between M. tuberculosis proteins and the ova323-339 peptide. Despite being reactive with a clonotypic antibody that is specific for the Vα13 Vβ8.2 TCR, it is also known that DO11.10 TCR transgenic mice can rearrange alternative α-chain TCRs and express other α-chain TCRs simultaneously with Vα13 (17, 26). CD4 T cells from DO11.10 TCR transgenic mice could potentially generate alternative α chains that are sufficient to specifically react with antigens from M. tuberculosis and to limit the infection within the lung. DO11.10<rag> TCR transgenic mice (which exclusively express Vα13 Vβ8.2) and DO11.10 mice were infected with M. tuberculosis. The bacterial loads were equivalent within the lungs of DO11.10 and DO11.10<rag> mice at day 21 (data not shown), but the load was substantially increased in the lungs of DO11.10<rag> mice at 40 days postinfection (Fig. 3). Later time points were unavailable due to mortality within the DO11.10<rag> group.

FIG. 3.

DO11.10<rag> TCR transgenic mice fail to control infection with M. tuberculosis. DO11.10 and DO11.10<rag> TCR transgenic mice were given a low-dose aerosol infection with M. tuberculosis Erdman. After 40 days of infection, the bacterial load was determined within the lungs. The data are expressed as the mean log10 CFU per lung for four individual mice and are representative of two independent experiments. BALB/c mice were included in each study and had approximately 1 log fewer CFU within the lungs than DO11.10 TCR transgenic mice (data not shown).

CD4 T cells from the lungs of M. tuberculosis-infected DO11.10 TCR transgenic mice can produce IFN-γ.

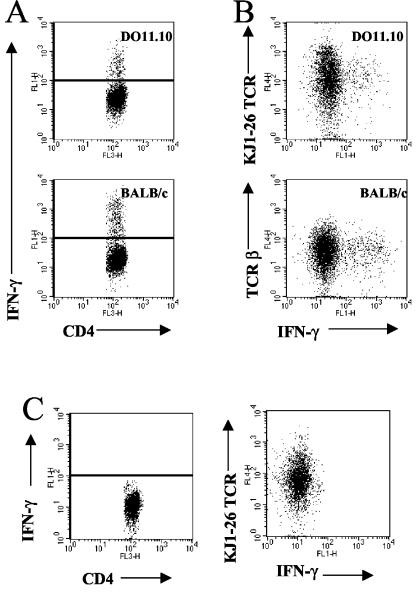

To determine whether CD4+ T cells from the lungs of DO11.10 TCR transgenic mice were responsible for the observed IFN-γ mRNA production during infection with M. tuberculosis, we performed intracellular cytokine staining. The isolation of lung cells and subsequent analysis by flow cytometry demonstrated that CD4 T cells isolated from the infected lungs of DO11.10 TCR transgenic mice were the predominant cell type capable of producing IFN-γ in response to an infection with M. tuberculosis (Fig. 4A and Table 2). Only a small proportion of the NK and NK T cells isolated from the lungs of DO11.10 TCR transgenic mice or BALB/c mice were capable of producing IFN-γ (Table 2). A further characterization of the cells from the infected lungs of DO11.10 TCR transgenic mice revealed that CD4+ αβ T cells expressing the clonotypic TCR (reactive with KJ1-26 antibody) were the primary source of IFN-γ (Fig. 4B). In contrast, CD4 T cells isolated from the lungs of infected DO11.10<rag> TCR transgenic mice were unable to produce IFN-γ (Fig. 4C). These data demonstrate that the ability of the clonotypic CD4 T cells to produce IFN-γ is recombinase dependent and therefore is likely a result of the dual expression of a novel α-chain TCR.

FIG. 4.

Intracellular IFN-γ production by CD4 T cells from the lungs of infected mice. (A) Lung cells were isolated from mice infected for 30 days and were incubated with CD3/CD28 and monensin for 4 h. The cells were surface stained with PerCP-CD4 in combination with the APC-KJ1-26 clonotypic antibody (DO11.10 mice) or the APC-TCRβ chain (BALB/c mice). After a permeabilization step, cells were labeled with FITC-IFN-γ. Lymphocytes were gated by size and granularity. Data for at least 100,000 events were analyzed with Cellquest software. (B) Representative dot plots are shown depicting IFN-γ-positive CD4+ TCR+ cells. Isotype antibody staining was 0.16% (±0.2%; n = 11). IFN-γ was not detected in noninfected controls (0.41% ± 0.2%; n = 4). The data are the means and standard errors for four mice per group and are representative of three independent experiments. (C) Intracellular cytokine labeling of cells isolated from the lungs of DO11.10<rag> TCR transgenic mice that had been infected with M. tuberculosis for 30 days revealed that CD4 T cells from DO11.10<rag> TCR transgenic mice could not produce IFN-γ (0.30% ± 0.1%). The data are representative of two independent experiments.

TABLE 2.

Quantification of intracellular IFN-γ production by cells in the lungs of infected mice, as determined by flow cytometry

| Cell population | % IFN-positive cells | SEM |

|---|---|---|

| DO11.10 NK | 0.08 | 0.04 |

| DO11.10 NK T | 0.71 | 0.07 |

| DO11.10 CD4 | 6.10 | 0.60 |

| BALB/c NK | 2.98 | 1.20 |

| BALB/c NK T | 1.72 | 0.40 |

| BALB/c CD4 T | 8.40 | 0.80 |

Infection of DO11.10 TCR transgenic mice with M. tuberculosis results in ovalbumin-specific T cells within the lungs.

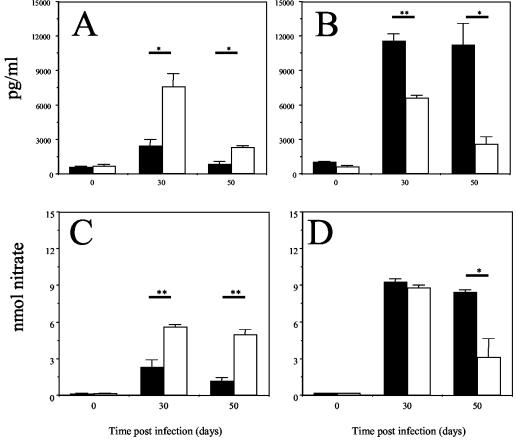

To determine whether CD4 T cells from DO11.10 TCR transgenic mice were able to respond to defined antigens from M. tuberculosis, we exposed lung cells from DO11.10 TCR transgenic and BALB/c mice that were infected with M. tuberculosis for 30 days to an antigen in vitro. Day 30 was chosen because the DO11.10 TCR transgenic and BALB/c mice had equivalent bacterial loads (Fig. 1A) and comparable total numbers of cells within the lungs (1.53 × 107 ± 0.2 × 107 [mean ± standard error of the mean] and 1.35 × 107 ± 0.2 × 107, respectively; n = 8 for each group) at this time. Lung cell cultures were also isolated from mice who were infected for 50 days. Cells isolated from the lungs of M. tuberculosis-infected DO11.10 TCR transgenic mice and cultured with ovalbumin-pulsed macrophages produced IFN-γ (Fig. 5A), demonstrating that the differentiated clonotypic CD4+ T cells from DO11.10 TCR transgenic mice entered the lung in response to M. tuberculosis infection; the ovalbumin-specific response abated by 50 days of M. tuberculosis infection. The same lung cells from infected DO11.10 TCR transgenic mice cultured in the presence of M. tuberculosis-infected macrophages also produced IFN-γ (Fig. 5B); again, while the response was strong at 30 days, it had waned by 50 days. Lung cells from BALB/c mice infected for 30 and 50 days produced IFN-γ in response to M. tuberculosis-infected macrophages (Fig. 5B), but not in response to macrophages pulsed with ovalbumin. These data demonstrate that DO11.10 TCR transgenic mice infected with M. tuberculosis are able to recruit differentiated clonotypic CD4 T cells into the lungs and that these cells are capable of producing IFN-γ in response to both ovalbumin-pulsed and M. tuberculosis-infected macrophages. It should also be noted that in all cases, IFN-γ production resulted in the activation of macrophages and the production of nitric oxide, as determined by the presence of nitrates in the culture supernatants (Fig. 5C and D).

FIG. 5.

Production of IFN-γ by lung cells cocultured with antigen-pulsed macrophages. Lung cells were isolated from BALB/c (solid bars) or DO11.10 TCR transgenic (open bars) mice infected for 30 or 50 days and were incubated with macrophages that were prepulsed with ovalbumin (A and C) or virulent M. tuberculosis (B and D). Culture supernatants were assayed for the presence of IFN-γ by ELISA (A and B) or by measuring nitrates by the Greiss reaction (C and D). The data are expressed as the means for four individual mice plus standard errors of the means and are representative of three independent experiments. Statistical significance comparing BALB/c and DO11.10 TCR transgenic mice at each time point was determined by the Student t test. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.005.

TCR transgenic mice produce IFN-γ in response to cell wall components of M. tuberculosis.

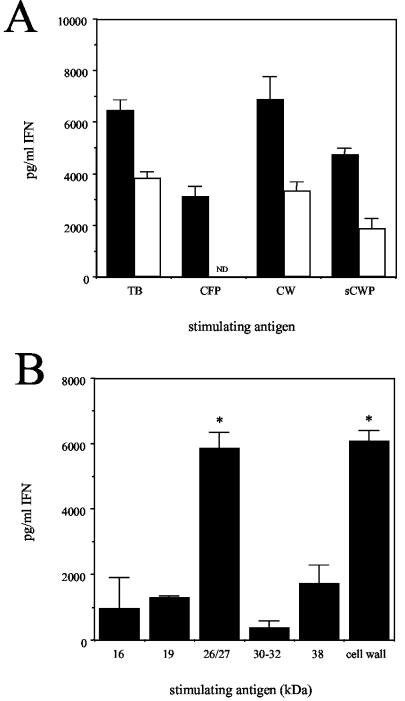

Although activated and differentiated CD4 T cells will traffic through an inflamed lung in a non-antigen-specific manner, they are unlikely to remain there in the absence of a specific antigen. To identify the antigen specificity of the IFN-γ-producing cells recruited to the lungs of infected DO11.10 mice, we cultured lung cells with bone-marrow-derived macrophages that were incubated overnight with either whole M. tuberculosis or its subunit components. Not surprisingly, the lung cells from infected BALB/c mice produced IFN-γ in response to live M. tuberculosis as well as the CFP, CW, and SCWP components of this bacterium (Fig. 6A). In contrast, lung cells from the infected DO11.10 TCR transgenic mice produced IFN-γ in response to live M. tuberculosis and the cell wall preparations (CW and SCWP), but not to the CFP (Fig. 6A). Further size fractionation of the soluble cell wall proteins of M. tuberculosis revealed a peak of IFN-γ production by lung cells from the infected DO11.10 TCR transgenic mice in response to fractions with molecular masses ranging from 15 to 40 kDa (data not shown). To more accurately define the M. tuberculosis product(s) that stimulated IFN-γ production, we cultured lung cells from M. tuberculosis-infected DO11.10 TCR transgenic mice with macrophages that were pulsed with a panel of purified or partially purified cell wall antigens of M. tuberculosis. These analyses revealed that lung cells from M. tuberculosis-infected DO11.10 TCR transgenic mice preferentially produced IFN-γ in response to the 26/27-kDa protein fraction from a Triton X-114-soluble extract of M. tuberculosis (Fig. 6B).

FIG. 6.

Lung cells from DO11.10 mice express reactivity with the cell wall-associated antigens of M. tuberculosis. (A) Lung cells were isolated from DO11.10 TCR transgenic (open bars) or BALB/c (solid bars) mice that had been infected with M. tuberculosis for 30 days. Cells were cultured with bone-marrow-derived macrophages that had been incubated overnight with M. tuberculosis (5 × 106 CFU/ml) or the CFP (10 μg/ml), CW (10 μg/ml), or SCWP (10 μg/ml) component. Culture supernatants were assayed for the presence of IFN-γ by ELISA. The data are representative of 12 individual mice from three independent experiments. ND, not detected. (B) Lung cells were isolated from DO11.10 TCR transgenic mice that were infected for 30 days and were cultured with antigen-pulsed bone-marrow-derived macrophages. All antigens were used at a final concentration of 10 μg/ml. Culture supernatants were assayed for the presence of IFN-γ by ELISA. The medium control value (1,583 ± 168) was subtracted from the antigen-specific values. The data are the means ± standard errors of the means for three individual DO11.10 mice from three independent experiments. Statistical significance was determined by comparing IFN-γ production in response to individual antigens and in response to the 16-kDa antigen by the Student t test. *, P < 0.05.

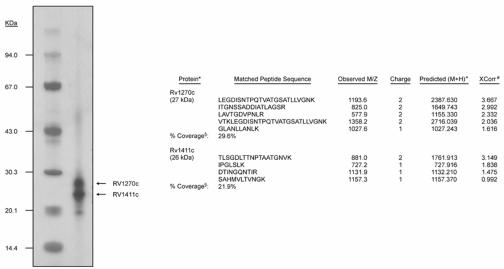

An analysis of the 26/27-kDa fraction by SDS-PAGE in the NuPAGE bis-Tris polyacrylamide gel system revealed the presence of two proteins (Fig. 7). These proteins were excised from the gel, subjected to an in-gel digestion with trypsin, and identified by tandem MS of the resulting peptides. The analysis of the peptides derived from the 26-kDa protein by tandem MS yielded four peptides with fragmentation patterns that could be mapped to theoretical fragmentation patterns of peptides of Rv1411c with a high degree of confidence. A similar analysis of trypsin-derived peptides of the 27-kDa protein resulted in five peptides that produced fragmentation patterns that were mapped to Rv1270c with a high degree of confidence. In all, these peptides provided 22 and 30% sequence coverage, corresponding to the M. tuberculosis gene products Rv1411c and Rv1270c, respectively (Fig. 7). Both of these gene products are putative lipoproteins, and no peptides corresponding to other M. tuberculosis proteins were observed in the tandem MS analysis of these proteolytic digests.

FIG. 7.

Analysis of 26/27-kDa proteins. The figure shows an SDS-PAGE analysis of the 26/27-kDa Triton X-114-soluble protein fraction of M. tuberculosis. Arrows denote the two products identified by tandem MS. The right panel shows the results of a SEQUEST search of the tandem MS data for 26- and 27-kDa products. *, the identity of the protein as denoted in the TubercuList genome database (http://genolist.pasteur.fr/TubercuList/); +, the monoisotopic mass calculated from the singly charged ion of the matched peptide; #, the correlation coefficient of the assigned peptide pattern of MS and tandem MS spectra to the observed MS and tandem MS spectra versus all of the other peptides in the database; §, the percentage of the total protein sequence covered by tandem MS analysis.

CD4 T cells from DO11.10 TCR transgenic mice produce IFN-γ specifically to the 26-kDa lipoprotein antigen (Rv1411c) of M. tuberculosis.

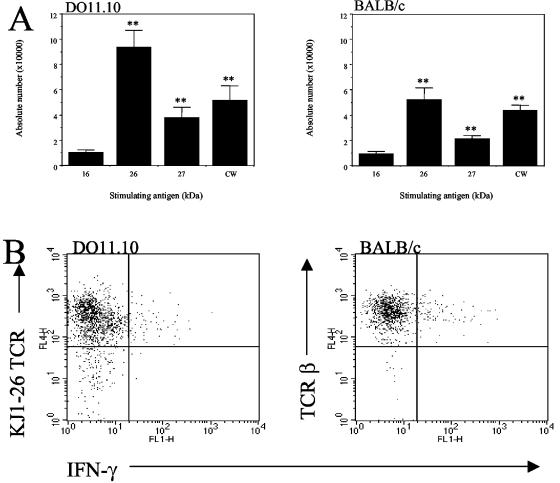

We identified the 26-kDa Rv1411c antigen as a ConA-reactive glycoprotein (J. Belisle and K. Dobos, unpublished results). Thus, fractionation via ConA affinity chromatography was used to further purify Rv1411c and Rv1270c. An analysis by tandem MS of the protein(s) contained in the nonbinding and ConA binding fractions resulting from this chromatographic procedure revealed that the bound material was pure Rv1411c, whereas the nonbinding material was predominantly Rv1270c, with a slight contamination by Rv1411c (data not shown). To determine whether lung cells from infected DO11.10 TCR transgenic mice could respond specifically to purified Rv1411c or the enriched Rv1270c antigen, we cultured cells for 24 h with Rv1411c-, enriched Rv1270c-, or 16-kDa α-crystallin (negative control)-pulsed macrophages. The ability of the cells to produce IFN-γ in response to these specific antigens was determined by intracellular staining. CD4 T cells from both DO11.10 TCR transgenic and BALB/c mice produced significantly more IFN-γ when cultured with macrophages pulsed with the cell wall antigen (Fig. 8A) than with the 16-kDa α-crystallin of M. tuberculosis. IFN-γ production was, however, substantially and significantly increased in response to the purified Rv1411c lipoprotein from M. tuberculosis, demonstrating a specific CD4-T-cell reactivity to this single antigen (Fig. 8B). IFN-γ production in response to the enriched Rv1270c lipoprotein was significantly lower than that to purified Rv1411c, and therefore the IFN-γ production observed was interpreted as residual Rv1411c contamination (Fig. 8B). Further analysis demonstrated that CD4 T cells from DO11.10 TCR transgenic mice that were capable of producing IFN-γ in vitro in response to Rv1411c were positive for the clonotypic TCR (Fig. 8B).

FIG. 8.

Lung cells from DO11.10 mice produce IFN-γ specifically in response to the 26-kDa lipoprotein from M. tuberculosis. (A) Lung cells were isolated from DO11.10 TCR transgenic or BALB/c mice that had been infected 30 days previously with M. tuberculosis. Cells were cultured with antigen-pulsed macrophages for 24 h. Anti-CD28 and monensin were added 4 h prior to analysis. Cells were surface stained with PerCP-CD4 and APC-TCRβ chain (BALB/c) or APC-KJ1-26 (DO11.10), followed by a permeabilization step and intracellular FITC-IFN-γ staining. Lymphocytes were gated by size and granularity, and CD4+ T cells were identified by the expression of a specific labeled antibody. The data were analyzed with Cellquest software. Graphs depict the absolute numbers of CD4+ T cells from DO11.10 or BALB/c mice that could produce IFN-γ in response to specific antigens of M. tuberculosis. The data are representative of two independent experiments. Statistically significant increases were determined by the Student t test, and the differences were found to be highly significant (**, P < 0.005) when compared to the 16-kDa antigen. (B) Representative dot plots are gated on CD4+ cells and show IFN-γ production versus expression of the clonotypic TCR (DO11.10) or β TCR (BALB/c).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we found that CD4 T cells from DO11.10 TCR transgenic mice were able to produce IFN-γ in response to a 26-kDa lipoprotein of M. tuberculosis (Rv1411c) and that this limited reactivity mediated the control of M. tuberculosis growth within the lung during the early stage of infection. The ability of DO11.10 TCR transgenic mice to contain an infection with M. tuberculosis for an extended period of time was, however, limited. We also demonstrated that DO11.10<rag> TCR transgenic mice, which solely express Vα13 Vβ8.2, specific for ovalbumin peptide323-339 (19), were unable to produce IFN-γ in response to or survive an infection with M. tuberculosis, thereby implicating a specific TCR rearrangement in the recognition of the Rv1411c antigen.

The capacity of DO11.10, but not DO11.10<rag>, TCR transgenic mice to limit an infection with M. tuberculosis therefore demonstrates that the early control of infection in this transgenic mouse model is recombinase dependent and indicates that DO11.10 TCR transgenic mice express a second TCR with reactivity to antigens other than ovalbumin peptide323-339 (17, 26). In support of this, KJ1-26+ clonotypic CD4 T cells could also produce IFN-γ in response to antigens from M. tuberculosis. Interestingly, the fluorescence intensity of the clonotypic signal was lower on IFN-γ+ cells than that found on non-IFN-γ+ CD4 T cells from DO11.10 TCR or DO11.10<rag> TCR transgenic mice, and this appears to be associated with the expression of an alternative α-chain TCR in other TCR transgenic mouse models (18).

The potential for dual TCR expression on CD4 T cells from DO11.10 TCR transgenic mice would result in the recognition of antigens other than ovalbumin peptide323-339, but the limited TCR rearrangement would substantially diminish the repertoire of antigens that could be recognized. This appeared to be the case here, as cells from TCR transgenic mice were able to produce IFN-γ in response to ovalbumin and to M. tuberculosis, but our analysis further defined the antigen specificity to identify Rv1411c as a single dominant antigen that is capable of stimulating the production of IFN-γ by CD4 T cells in both DO11.10 TCR transgenic mice and BALB/c mice. We cannot fully rule out the probability that additional TCR combinations could occur in DO11.10 mice, resulting in TCR specificities against other mycobacterial antigens; however, the identification of one single antigen from the cell wall of M. tuberculosis which was superior to other cell wall proteins in its capacity to induce IFN-γ-producing CD4 T cells suggests that Rv1411c is a dominant antigen.

Rv1411c was previously identified in both Mycobacterium bovis and M. tuberculosis as P27 (2, 3) and has been described as an immunogen for both the humoral and cellular immune responses (3, 13). Despite its documented immunogenicity, vaccination studies with P27 not only failed to provide any protection against a subsequent challenge with M. tuberculosis but also reversed the known protective efficacy of M. bovis BCG (13). The deleterious effect of P27 in a vaccine regimen seems to be contrary to our observations in DO11.10 TCR transgenic mice, in which the recognition of the Rv1411c lipoprotein appears to result in a protective response. Whether the combination of the 26/27-kDa antigens (Rv1411c and Rv1270c) (13) used in the vaccine studies resulted in conflicting cellular responses was not addressed, but our data suggest that Rv1411c alone is protective and therefore that Rv1270c may be detrimental to the generation of protective immunity, as has been suggested for other antigens (23, 32). By further examining the relative abilities of Rv1411c and Rv1270c to generate and maintain protective antigen-specific CD4-T-cell responses in vivo, we will determine whether either, or both, is a suitable vaccine candidate.

The potential for mycobacterial antigens to interfere with protective immune responses is not unique. The 19-kDa lipoprotein can, for example, stimulate IFN-γ secretion in vitro, yet it does not afford any protection when used in a vaccination protocol (23). In fact, when presented as a recombinant antigen by Mycobacterium vaccae, the 19-kDa lipoprotein actually exacerbated infection (32). This interesting phenomenon is now hypothesized to be a result of prolonged exposure of the host TLR2 to the bacterial lipoprotein (22, 28). It is intriguing to postulate that the immune downregulation mediated by lipoproteins such as the 19-kDa lipoprotein (4, 22) may serve to limit T-cell responses in the lung. In this light, it is important to note that the Rv1411c antigen could stimulate bone-marrow-derived macrophages to produce interleukin-12 p40 and tumor necrosis factor in a TLR2-dependent mechanism (data not shown). Whether the induction of these cytokines contributes to the protective response or serves to limit cellular responses was not addressed here, but this possibility further supports the importance of determining the role of specific lipoproteins in mediating both protection and disease.

One interesting difference between the response in the DO11.10 TCR transgenic mice and the BALB/c mice was the loss of the antigen-specific response in the DO11.10 TCR transgenic mice by day 50. Our inability to observe a similar immunological shift in BALB/c mice suggests that the development of a complex in vivo immune response in an immunocompetent host is required for long-term survival. This requirement may reflect the need to compensate for the immunosuppressive influences of antigens such as lipoproteins.

These studies, therefore, show that a highly restricted T-cell response is sufficient to initially limit bacterial growth within the lungs of M. tuberculosis-infected mice. This ability was short-lived, however, thus confirming that the recognition of multiple antigens is an absolute requirement for maintaining a long-term containment of M. tuberculosis within the lung. The identification of Rv1411c as a potentially protective antigen was highlighted by the use of TCR transgenic mice and its role in inducing protective (or potentially negative) cellular responses during tuberculosis should be further examined.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grants AI-40488 and AI-44042 and contract NO1 AI-75320.

Editor: A. D. O'Brien

REFERENCES

- 1.Belisle, J. T., V. D. Vissa, T. Sievert, K. Takayama, P. J. Brennan, and G. S. Besra. 1997. Role of the major antigen of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in cell wall biogenesis. Science 276:1420-1422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bigi, F., A. Alito, M. I. Romano, M. Zumarraga, K. Caimi, and A. Cataldi. 2000. The gene encoding P27 lipoprotein and a putative antibiotic-resistance gene form an operon in Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Mycobacterium bovis. Microbiology 146:1011-1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bigi, F., C. Espitia, A. Alito, M. Zumarraga, M. I. Romano, S. Cravero, and A. Cataldi. 1997. A novel 27 kDa lipoprotein antigen from Mycobacterium bovis. Microbiology 143:3599-3605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brightbill, H. D., D. H. Libraty, S. R. Krutzik, R.-B. Yang, J. T. Belisle, J. R. Bleharski, M. Maitland, M. V. Norgard, S. E. Plevy, S. T. Smale, P. J. Brennan, B. R. Bloom, P. J. Godowski, and R. L. Modlin. 1999. Host defense mechanisms triggered by microbial lipoproteins through Toll-like receptors. Science 285:732-736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cattoretti, G., S. Piteri, C. Parraricini, M. A. G. Becker, S. Poggi, C. Bifulco, G. Key, E. S. L D'Amato, E. Fendale, F. Geynolds, J. Gerdes, and F. Rilke. 1993. Antigen unmasking on formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue sections. J. Pathol. 171:83-98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cole, S. T., R. Brosch, J. Parkhill, T. Garnier, C. Churcher, D. Harris, S. V. Gordon, K. Eiglmeier, S. Gas, C. E. Barry III, F. Tekaia, K. Badcock, D. Basham, D. Brown, T. Chillingworth, R. Connor, R. Davies, K. Devlin, T. Feltwell, S. Gentles, N. Hamlin, S. Holroyd, T. Hornsby, K. Jagels, B. G. Barrell, et al. 1998. Deciphering the biology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from the complete genome sequence. Nature 393:537-544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cooper, A. M., A. D. Roberts, E. R. Rhoades, J. E. Callahan, D. M. Getzy, and I. M. Orme. 1995. The role of interleukin-12 acquired immunity in Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. Immunology 84:423-432. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Covert, B. A., J. S. Spencer, I. M. Orme, and J. T. Belisle. 2001. The application of proteomics in defining the T cell antigens of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Proteomics 1:574-586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Diezel, W., G. Kopperschlager, and E. Hofmann. 1972. An improved procedure for protein staining in polyacrylamide gels with a new type of Coomassie brilliant blue. Anal. Biochem. 48:617-620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Flynn, J. L., and J. Chan. 2001. Immunology of tuberculosis. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 19:93-129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heinzel, A. S., J. E. Grotzke, R. A. Lines, D. A. Lewinsohn, A. L. McNabb, D. N. Streblow, V. M. Braud, H. J. Grieser, J. T. Belisle, and D. M. Lewinsohn. 2002. HLA-E-dependent presentation of Mtb-derived antigen to human CD8+ T cells. J. Exp. Med. 196:1473-1481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hellman, U., C. Wernstedt, J. Gonez, and C. H. Heldin. 1995. Improvement of an “In-Gel” digestion procedure for the micropreparation of internal protein fragments for amino acid sequencing. Anal. Biochem. 224:451-455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hovav, A.-H., J. Mullerad, L. Davidovitch, Y. Fishman, F. Bigi, A. Cataldi, and H. Bercovier. 2003. The Mycobacterium tuberculosis recombinant 27-kilodalton lipoprotein induces a strong Th1-type response deleterious to protection. Infect. Immun. 71:3146-3154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hunter, S. W., B. Rivoire, V. Mehra, B. R. Bloom, and P. J. Brennan. 1990. The major native proteins of the leprosy bacillus. J. Biol. Chem. 265:14065-14068. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Laemmli, U. K. 1970. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 227:680-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee, B. Y., S. A. Hefta, and P. J. Brennan. 1992. Characterization of the major membrane protein of virulent Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infect. Immun. 60:2066-2074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee, W. T., J. Cole-Calkins, and N. E. Street. 1996. Memory T cell development in the absence of specific antigen priming. J. Immunol. 157:5300-5307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Linton, P.-J., L. Haynes, N. R. Klinman, and S. L. Swain. 1996. Antigen-independent changes in naive CD4 T cells with aging. J. Immunol. 184:1891-1900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lukin, K., M. Cosyns, T. Mitchell, M. Saffry, and A. Hayward. 2000. Eradication of Cryptosporidium parvum infection by mice with ovalbumin-specific T cells. Infect. Immun. 68:2663-2670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morrissey, J. H. 1981. Silver stain for proteins in polyacrylamide gels: a modified procedure with enhanced uniform sensitivity. Anal. Biochem. 117:307-310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Murphy, K. M., A. B. Heimberger, and D. Y. Loh. 1990. Induction by antigen of intrathymic apoptosis of CD4+ CD8+ TCRlo thymocytes in vivo. Science 250:1720-1723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Noss, E., R. K. Pai, T. J. Sellati, J. D. Randolf, J. Belisle, D. T. Golenbock, W. H. Boom, and C. V. Harding. 2001. Toll-like receptor 2-dependent inhibition of macrophage class II MHC expression and antigen processing by 19-kDa lipoprotein of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Immunol. 167:910-918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Post, F. A., C. Manca, O. Neyrolles, B. Ryffel, D. B. Young, and G. Kaplan. 2001. Mycobacterium tuberculosis 19-kilodalton lipoprotein inhibits Mycobacterium smegmatis-induced cytokine production by human macrophages in vitro. Infect. Immun. 69:1433-1439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rhoades, E. R., A. A. Frank, and I. M. Orme. 1997. Progression of chronic pulmonary tuberculosis in mice aerogenically infected with virulent Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 78:57-66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roberts, A. D., A. M. Cooper, J. T. Belisle, J. Turner, M. Gonzalez-Juarrero, and I. M. Orme. 2002. Murine model of tuberculosis. Methods Microbiol. 32:433-462. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Saparov, A., L. A. Kraus, Y. Cong, J. Marwill, X. Y. Xu, C. O. Elson, and C. T. Weaver. 1999. Memory/effector T cells in TCR transgenic mice develop via recognition of enteric antigens by a second, endogenous receptor. Int. Immunol. 11:1253-1264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Takayama, K., H. K. Schnoes, E. L. Armstrong, and R. W. Boyle. 1975. Site of inhibitory action of isoniazid in the synthesis of mycolic acids in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Lipid Res. 16:308-317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tobian, A. A. R., N. S. Potter, L. Ramachandra, R. K. Pai, M. Convery, W. H. Boom, and C. V. Harding. 2003. Alternate class I MHC antigen processing is inhibited by Toll-like receptor signaling pathogen-associated molecular patterns: Mycobacterium tuberculosis 19-kDa lipoprotein, CpG DNA, and lipopolysaccharide. J. Immunol. 171:1413-1422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Turner, J., M. Gonzales-Juarrero, D. L. Ellis, R. J. Basaraba, A. Kipnis, I. M. Orme, and A. M. Cooper. 2002. In vivo IL-10 production reactivates chronic pulmonary tuberculosis in C57BL/6 mice. J. Immunol. 169:6343-6351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Turner, J., M. Gonzalez-Juarrero, B. Saunders, J. V. Brooks, P. Marietta, A. A. Frank, A. M. Cooper, and I. M. Orme. 2001. Immunological basis for reactivation of tuberculosis in mice. Infect. Immun. 69:3264-3270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yates, J. R., III, J. K. Eng, A. L. McCormack, and D. Schieltz. 1995. Method to correlate tandem mass spectra of modified peptides to amino acid sequences in the protein database. Anal. Chem. 67:1426-1436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yeremeev, V. V., I. V. Lyadova, B. V. Nikonenko, A. S. Apt, C. Abou-Zeid, J. Inwald, and D. B. Young. 2000. The 19-kD antigen and protective immunity in a murine model of tuberculosis. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 120:274-279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]