Abstract

Streptococcus mutans NG5 failed to anchor antigen P1 to the cell surface, and such a failure could be attributed to a defective SrtA, which was made defective by a point mutation within the srtA gene. Without a functional SrtA, S. mutans NG5 was not able to perform a number of cell surface-related activities, including saliva-mediated adherence and aggregation.

Streptococcus mutans is the etiological agent for dental caries (8, 18). The organism produces the major cell surface protein P1, also known as antigen I/II (ca. 185 kDa), that interacts with a high-molecular-weight salivary agglutinin (17). Such an interaction has been shown to promote the adherence of S. mutans to hydroxylapatite in vitro (17) and is implicated in S. mutans colonization of teeth in vivo (6, 15). In rats, the isogenic P1-negative mutant (6) and an srtA mutant that failed to surface express P1 (15) were less cariogenic than the wild-type strain. In addition, antigen P1 has been given much attention as a potential vaccine against dental caries (23).

Antigen P1 carries a common C-terminal domain that includes a hydrophilic (cell wall-associated) region, a highly conserved LPXTG motif, a hydrophobic (membrane-spanning) domain, and a charged tail (10, 12). It was previously demonstrated that the C-terminal domain is responsible for anchoring P1 to the cell wall (10, 11, 16). Recently it was shown that sortase (SrtA) was responsible for sorting and anchoring P1 to the cell wall of S. mutans NG8 (15). SrtA is a transpeptidase, and in Staphylococcus aureus SrtA cleaves between the thr and gly residues in the LPXTG motif of protein A and amide bonds protein A to the cross bridge of peptidoglycan (26).

Various strains of S. mutans differ in their ability to retain P1 on the cell surface. S. mutans NG8 is considered a retainer strain because the P1 protein is cell surface associated, whereas S. mutans NG5 is considered a nonretainer strain because P1 protein is found predominantly in the culture fluid rather than being cell surface associated (3, 13). Previous studies by Brady et al. (5) suggest that the nonretainer phenotype could not be attributed to loss of the C terminus of the P1 protein. In addition, the sequence of the P1 gene from the NG5 strain did not reveal any premature termination codons (12). In fact, when the P1 gene cloned from NG5 was expressed in an isogenic P1-negative mutant of NG8, the gene product was surface localized (10). The nature of the difference in the retainer versus nonretainer phenotype is unknown. The nonretainer phenotype could be the result of a defective sortase which fails to anchor the protein to the cell wall. Alternatively, it could be due to defects in the peptidoglycan structure itself (e.g., the cross bridges), to which the P1 protein is linked.

Amino acid composition of peptidoglycan samples.

To investigate whether there were any anomalies in the peptidoglycan structure, trypsinized peptidoglycan was prepared from the cell walls of S. mutans NG8 and NG5 using methods described previously (11). The peptidoglycan samples were analyzed for amino acid content (Protein Sequencing Facility, University of Calgary). Peptidoglycan samples were hydrolyzed in a solution of 6N HCl and 0.1% β-mercaptoethanol at 150°C for 1 h in vacuo. Hydrolysis of peptidoglycan in 6N HCl with 4% thioglycolic acid for tryptophan (19) and performic acid oxidation for cysteine (9) were also conducted at 150°C for 1 h. Hydrolysis of peptidoglycan in 6N HCl at 100°C for 6 h in vacuo was completed for amino sugar analysis. The amino acids were analyzed on a Beckman 6300 amino acid analyzer with ninhydrin detection. Norleucine was added to the sample prior to hydrolysis as an internal standard. Each amino acid was quantitated by the external standard method with the Beckman System Gold software (Beckman Coulter, Inc., Quebec, Canada). The analysis data was converted to moles percent and amino acid composition by using software created at the Protein Sequencing Facility.

The amino acid composition of the peptidoglycan from both NG8 and NG5 indicated a similar molar ratio for the predominant amino acids, glu:ala:lys, which was 1:3.6:1 (Table 1). Trace amounts of all other amino acids were present after acid hydrolysis of the samples. Threonine, a component of the peptide cross bridge of S. mutans, which is predominantly L-Lys-L-Thr-L-Ala (25), was also found in trace amounts. This finding is not unexpected, because threonine is often partially destroyed by acid hydrolysis. These results suggest that there are no major structural differences between the peptidoglycans from NG8 and NG5.

TABLE 1.

Amino acid composition of isolated peptidoglycan from the S. mutans P1 retainer strain NG8 and the P1 nonretainer strain NG5

| Amino acid | NG8

|

NG5

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pmol | mol%a | Amino acid ratiob | pmol | mol% | Amino acid ratio | |

| Asp | 312 | 0.76 | 329 | 0.88 | ||

| Thr | 184 | 0.45 | 194 | 0.52 | ||

| Ser | 382 | 0.93 | 455 | 1.22 | ||

| Glu | 7,390 | 18.02 | 1.01 | 6,684 | 17.93 | 1.00 |

| Gly | 236 | 0.58 | 387 | 1.04 | ||

| Ala | 26,325 | 64.20 | 3.61 | 23,923 | 64.18 | 3.59 |

| Val | 221 | 0.54 | 295 | 0.79 | ||

| Met | 32 | 0.08 | 73 | 0.19 | ||

| Ile | 172 | 0.42 | 320 | 0.86 | ||

| Leu | 216 | 0.53 | 431 | 1.16 | ||

| Tyr | 110 | 0.27 | 137 | 0.37 | ||

| Phe | 219 | 0.53 | 343 | 0.92 | ||

| His | 42 | 0.10 | 60 | 0.16 | ||

| Lys | 7,284 | 17.77 | 1.00 | 6,668 | 17.89 | 1.00 |

| Trp | 23 | 0.06 | ND | |||

| Arg | NDc | 78 | 0.21 | |||

| Pro | 92 | 0.23 | 142 | 0.38 | ||

| Nled | 236 | 513 | ||||

Moles percent was calculated as (picomoles of amino acids/total picomoles) × 100. The total picomoles for NG8 and NG5 were 41,000.28 and 37,276.38, respectively.

Ratio of the three predominant amino acids Gly, Ala, and Lys. The moles percent of Lys was used to normalize the values for Gly and Ala.

ND, not detected.

Nle, norleucine (internal standard).

Cloning and analysis of srtA.

Because there are no anomalies in the gene encoding the NG5 P1 protein or in the peptidoglycan composition, the reason P1 fails to anchor covalently to the cell wall may be due to a defect in sortase activity. Such a failure would explain the predominance of P1 in the culture supernatant of P1 nonretainer strain NG5.

The srtA gene, including ca. 300 bp of upstream sequence, was amplified from S. mutans NG5 by PCR using a high-fidelity DNA polymerase (Deep VentR; New England Biolabs, Mississauga, Ontario, Canada) and the primers SL177 and SL189 as described previously for NG8 (15). The PCR product was cloned into pBluescript and was sequenced with T3 and T7 primers (Applied Biosystems/Dalhousie University—National Research Council joint laboratory facilities). Sequence analysis showed that the S. mutans NG5 SrtA was 98% identical to the NG8 SrtA, including the 40-amino-acid signal sequence, the putative active site (VTLVTCTD), and upstream sequences that contain a putative promoter region, an inverted repeat sequence, and the putative DNA gyrase A protein. However, NG5 SrtA contained a stop codon at amino acid residue 132, which was 70 amino acids upstream of the putative enzyme active site. The stop codon arose from a single base substitution from G to T at the codon GAA, which codes for glutamic acid in NG8. These results indicate that NG5 SrtA contains a nonsense mutation that may have led to premature termination and defective cell wall sorting activity.

srtA complementation.

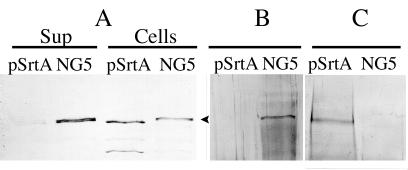

To demonstrate that the inability to sort P1 to the cell wall is due to a defective sortase, the functional srtA gene previously cloned from NG8 and carried on pSrtA (15) was introduced into NG5 by natural transformation (10). The transformant obtained was designated NG5(pSrtA). P1 produced by NG5 and NG5(pSrtA) was analyzed by Western blotting. As shown in Fig. 1A, P1 produced by NG5 was found in the culture supernatant and cell extract while P1 produced by NG5(pSrtA) was only found in the cell extract fraction. When P1 produced by the two strains was analyzed for the C-terminal hydrophobic domain and charged tail by Western blotting, only P1 produced by NG5 reacted with the antibody specific for this domain (Fig. 1B). This result indicates that NG5 P1 has not been enzymatically processed by SrtA while NG5(pSrtA) P1 was processed. To examine the nature of association of NG5 P1 with the peptidoglycan, cell walls were prepared from the two strains and were subjected to boiling sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) extraction (10, 16). The cell walls were then solubilized by mutanolysin treatment and were analyzed for P1. As shown in Fig. 1C, the NG5 cell wall was devoid of P1 after the boiling SDS treatment, while the NG5(pSrtA) cell wall still retained P1 after a similar treatment. This result suggests that NG5 P1 was not covalently linked to the peptidoglycan and that complementing NG5 with a functional SrtA resulted in covalent linkage of P1 to the peptidoglycan

FIG. 1.

Western immunoblots of P1 from S. mutans NG5 and NG5(pSrtA). (A) P1 was extracted from cells with boiling SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis buffer as described previously (10, 16) or was precipitated from culture supernatant fluids (Sup) by trichloroacetic acid. P1 was detected with the monoclonal anti-P1 antibody 4-10A (1/7,000) (1), which recognized an epitope to the central part of P1. (B) Cell-associated P1 extracted with SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis buffer was detected by a rabbit polyclonal antibody raised against the C-terminal hydrophobic domain and charged tail of P1 (1/100) (16). (C) P1 in mutanolysin digests of hot SDS-extracted cell walls was detected by the monoclonal antibody 4-10A. The arrowhead indicates the ca. 185-kDa P1.

Collectively, the above results strongly indicate that the inability of NG5 to anchor P1 to the cell wall is due to defective SrtA. Murakami et al. (22) previously showed that another S. mutans strain, GS5, was unable to surface localize P1, but this defect was due to a frame shift mutation within the P1 gene resulting in premature termination. Other laboratories have previously reported that strains of S. mutans will lose the P1 retainer phenotype upon subculturing (14, 21, 24). The reason behind such a phenomenon is not known, but it is possible that these strains have acquired a mutation in srtA upon subculturing. Findings from this study are consistent with those described for S. aureus (20), Listeria monocytogenes (2, 7), and Streptococcus gordonii (4) that showed SrtA is responsible for surface expression of LPXTG-containing proteins in these bacteria.

Surface-related biological properties.

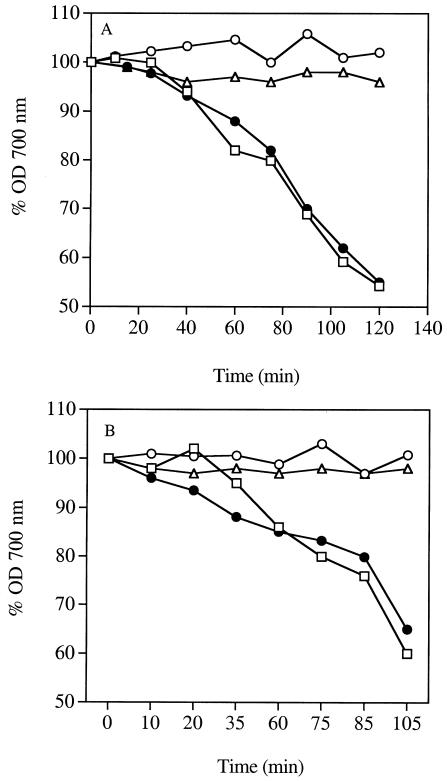

The cell surface-related properties of S. mutans NG5 and NG5(pSrtA) were investigated in aggregation, adherence, and hydrophobicity assays using methods described previously (15). In saliva-induced aggregation, NG5(pSrtA) and NG8 aggregated upon incubation with saliva but NG5 failed to aggregate (Fig. 2A). Similar results were observed with salivary agglutinin (Fig. 2B).

FIG. 2.

Saliva- (A) and salivary agglutinin-induced (B) aggregation of S. mutans NG5, NG5(pSrtA), and NG8. Aggregation was conducted in the presence of 200 μl of freshly clarified whole saliva and 800 μl of NG8 (closed circles), NG5 (open circles), or NG5(pSrtA) cells (squares). For panel B, salivary agglutinin (0.1 μg) was used in place of saliva. Triangles represent NG5(pSrtA) cells in the absence of saliva or salivary agglutinin. OD 700 nm, optical density at 700 nm.

When the cells were assayed for adherence to saliva- or agglutinin-coated hydroxylapatite, a striking difference between the NG5, NG5(pSrtA), and NG8 was observed. NG5 was nonadherent, with the percentages of adherence (means ± standard deviations) to saliva-coated and agglutinin-coated hydroxylapatite being 5.4% ± 3.2% and 2.4% ± 2.1%, respectively. In contrast, NG5(pSrtA) showed 50.5% ± 4.8% and 51.6% ± 1.3% adherence to saliva-coated and agglutinin-coated hydroxylapatite, respectively. The P1 retainer strain NG8 behaved in a manner similar to that of NG5(pSrtA), with 55.9% ± 3.4% and 53.7% ± 6.1% adherence to the respective surfaces. NG5 was markedly less hydrophobic than NG5(pSrtA) and NG8. The percentages of cells adsorbed to hexadecane (means ± standard deviations) for NG5, NG5(pSrtA), and NG8 were 2.2% ± 6%, 57.2% ± 6%, and 58.9% ± 10%, respectively.

These results indicate that NG5 was nonadherent to hydroxylapatite, nonaggregating in the presence of saliva or salivary agglutinin, and hydrophilic. These phenotypes could be converted to one similar to that of a P1 retainer strain (i.e., adherent, aggregating, and hydrophobic) by complementation with a functional SrtA. The above results are in good agreement with previous srtA inactivation studies in which the S. mutans NG8 srtA mutant was shown to be nonadherent, nonaggregating, and hydrophilic (15). The findings are also in agreement with those reported for S. gordonii in which the srtA mutant was shown to display a decreased adherence to immobilized fibronectin (4).

Conclusions.

S. mutans NG5 failed to anchor antigen P1 to the cell surface, and such a failure could be attributed to a defective SrtA, which was made defective by a point mutation within the srtA gene. Without a functional SrtA, S. mutans NG5 was not able to perform a number of cell surface-related activities, including saliva-mediated adherence and aggregation.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The sequence described in this study can be obtained from GenBank under accession number AY462103.

Acknowledgments

We thank L. Tao and Y. J. Li for their technical assistance.

This study was supported by NSERC.

Editor: V. J. DiRita

REFERENCES

- 1.Ayakawa, G. Y., L. W. Boushell, P. J. Crowley, G. W. Erdos, W. P. McArthur, and A. S. Bleiweis. 1987. Isolation and characterization of monoclonal antibodies specific for antigen P1, a major surface protein of mutans streptococci. Infect. Immun. 55:2759-2767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bierne, H., S. K. Mazmanian, M. Trost, M. G. Pucciarelli, G. Liu, P. Dehoux, L. Jansch, F. Garcia-del Portillo, O. Schneewind, and P. Cossart. 2002. Inactivation of the srtA gene in Listeria monocytogenes inhibits anchoring of surface proteins and affects virulence. Mol. Microbiol. 43:869-881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bleiweis, A. S., P. C. F. Oyston, and L. J. Brady. 1992. Molecular, immunology and functional characterization of the major surface adhesin of Streptococcus mutans, p. 229-241. In J. E. Ciardi et al. (ed.), Genetically engineered vaccines. Plenum Press, New York, N.Y. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Bolken, T. C., C. A. Franke, K. F. Jones, G. O. Zeller, C. H. Jones, E. K. Dutton, and D. E. Hruby. 2001. Inactivation of the srtA gene in Streptococcus gordonii inhibits cell wall anchoring of surface proteins and decreases in vitro and in vivo adhesion. Infect. Immun. 69:75-80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brady, L. J., D. A. Piacentini, P. J. Crowley, and A. S. Bleiweis. 1991. Identification of the monoclonal antibody-binding domains within antigen P1 of Streptococcus mutans and cross-reactivity with related surface antigens of oral streptococci. Infect. Immun. 59:4425-4435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crowley, P. J., L. J. Brady, S. M. Michalek, and A. S. Bleiweis. 1999. Virulence of a spaP mutant of Streptococcus mutans in a gnobiotic rat model. Infect. Immun. 67:1201-1206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Garandeau, C., H. Reglier-Poupet, I. Dubail, J. L. Beretti, P. Berche, and A. Charbit. 2002. The sortase SrtA of Listeria monocytogenes is involved in processing internalin and in virulence. Infect. Immun. 70:1382-1390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hamada, S., and H. D. Slade. 1980. Biology, immunology, and cariogenicity of Streptococcus mutans. Microbiol. Rev. 44:331-384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hirs, C. H. W. 1967. Determination of cystine as cysteic acid. Method Enzymol. 10:59-62. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Homonylo-McGavin, M. K., and S. F. Lee. 1996. Role of the C terminus in antigen P1 surface localization in Streptococcus mutans and two related cocci. J. Bacteriol. 178:801-807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Homonylo-McGavin, M. K., S. F. Lee, and G. H. Bowden. 1999. Subcellular localization of the Streptococcus mutans P1 protein C terminus. Can. J. Microbiol. 45:536-539. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kelly, C., P. Evans, J. K.-C. Ma, L. A. Bergmeier, W. Taylor, L. J. Brady, S. F. Lee, A. S. Bleiweis, and T. Lehner. 1990. Sequence and characterization of the 185 kDa cell surface antigen of Streptococcus mutans. Arch. Oral Biol. 35:33S-38S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Knox, K. W., L. N. Hardy, and A. J. Wicken. 1986. Comparative studies on the protein profiles and hydrophobicity of strains of Streptococcus mutans serotype c. J. Gen. Microbiol. 132:2541-2548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koga, T., H. Asakawa, N. N. Okashashi, and I. Takahashi. 1989. Effect of subculturing on expression of a cell-surface protein antigen by Streptococcus mutans. J. Gen. Microbiol. 135:3119-3207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee, S. F., and T. L. Boran. 2003. Roles of sortase in surface expression of the major protein adhesin P1, saliva-induced aggregation and adherence, and cariogenicity of Streptococcus mutans. Infect. Immun. 71:676-681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee, S. F., and L.-Q. Gao. 2000. Mutational analysis of the C terminus of Streptococcus mutans P1 protein: role of the LPXTGX motif in P1 association with the cell wall. Can. J. Microbiol. 46:584-592. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee, S. F., A. Progulske-Fox, G. W. Erdos, G. A. Ayakawa, P. J. Crowley, and A. S. Bleiweis. 1989. Construction and characterization of isogenic mutants of Streptococcus mutans deficient in the major surface protein antigen P1. Infect. Immun. 57:3306-3313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Loesche, W. J. 1986. Role of Streptococcus mutans in human dental decay. Microbiol. Rev. 50:353-380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Matsubara, H., and R. M. Sasaki. 1969. High recovery of tryptophan from acid hydrolysates of proteins. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 35:175-181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mazmanian, S. K., G. Liu, E. R. Jensen, E. Lenoy, and O. Schneewind. 2000. Staphylococcus aureus sortase mutants defective in the display of surface proteins and in the pathogenesis of animal infections. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:5510-5515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McBride, B. C., M. Song, B. Krasse, and J. Olsson. 1984. Biochemical and immunological differences between hydrophobic and hydrophilic strains of Streptococcus mutans. Infect. Immun. 44:68-75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Murakami, Y., Y. Nakano, Y. Yamashita, and T. Koga. 1997. Identification of a frameshift mutation resulting in premature termination and loss of cell wall anchoring of the Pac antigen of Streptococcus mutans GS5. Infect. Immun. 65:794-797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Russell, M. W. 1992. Immunization against dental caries. Curr. Opin. Dent. 2:72-80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Russell, R. R. B., and K. Smith. 1986. Effect of subculturing on location of Streptococcus mutans antigens. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 35:319-323. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schleifer, K. H., and O. Kandler. 1972. Peptidoglycan types of bacterial cell walls and their taxonomic implications. Bacteriol. Rev. 36:407-477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ton-That, H., G. Liu, S. K. Mazmanian, K. F. Faull, and O. Schneewind. 1999. Purification and characterization of sortase, the transpeptidase that cleaves surface proteins of Staphylococcus aureus at the LPXTG motif. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:12424-12429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]