Abstract

Background:

This study aimed to assess the efficacy of topiramate, a glutamate-modulating agent, in patients with treatment-resistant obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) as an adjunct to serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SRIs).

Materials and Methods:

Thirty-eight patients with refractory OCD, were randomly assigned to receive topiramate or placebo. This study was designed as a 12 weeks, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Primary outcome measures were the change in Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS) score and the rate of treatment response in each group at the study end point. Treatment response was considered as 25% or more reduction in Y-BOCS score.

Results:

A total of 13 patients in the topiramate group and 14 ones in the placebo group completed the trial. Topiramate-assigned patients showed significantly improved mean Y-BOCS score over time (P < 0.001). Although differences between two groups were significant in the Y-BOCS score at the first 2 months (P = 0.01), this was not significant at the end of the study (P = 0.10). Changes of Clinical Global Impression (CGI)-Severity of Illness Scale score and CGI-Improvement Scale score were not significantly different between two groups (P > 0.05). Treatment response was almost significantly different in the topiramate group comparing placebo group (P = 0.054). Mean topiramate dosage was 137.5 mg/day (range, 100-200).

Conclusion:

This study didn’t show efficacy of topiramate as an agent to augment SRIs in treatment-resistant OCD patients.

Keywords: Clinical global impression scale, obsessive-compulsive disorder, randomized controlled trials, topiramate, Yale-Brown obsessive-compulsive scale

INTRODUCTION

Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) is a common, neuropsychiatric disorder that can have debilitating effects on both genders throughout their life. The lifetime prevalence of the disorder is about 2-3%.[1]

Although selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and clomipramine are recommended as first-line agents for drug treatment of OCD,[2] it is estimated that more than 40-60% of the SSRIs treated population are treatment resistant.[3] Treatment-resistant OCD patients are described as those who received adequate trials of first-line therapies, but a reduction in their Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS) is <25% or <35% with respect to baseline.[4]

An adequate trial of first-line therapies is described as at least 10-12 weeks of highest tolerated dose of serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SRIs).[5] In another description, Pallanti and Quercioli defined treatment response stages; 35% or greater reduction in Y-BOCS as “full response,” ≥25% but <35% as “partial response,” and <25% as “nonresponse.”[6]

There are lots of strategies to augment the treatment response in nonresponsive patients ranging from adding cognitive-behavioral therapy[7,8,9] to pharmacotherapy augmentations such as Antipsychotics,[10,11,12,13] a combination of another SRIs,[14,15] lamotrigine,[16] etc., or even the use of neurosurgical procedures.[17] One of the strategies, investigate in recent years, to treat the refractory OCD has been adding glutamate-modulating agents (GMAs) to the existing treatment.

With respect to many neuroimaging[18,19,20] and glutamate concentration studies[21] glutamate may has a role in the pathophysiology of OCD. Animal models of OCD and also genetic studies provided us additional support; in one study McGrath et al. showed that transgenic mice with increased glutamate output to the striatum revealed a phenotype similar to comorbid OCD and Tourette syndrome.[22] Two linkage studies have proposed that the gene Solute Carrier Family 1, Member 1 (SLC1A1) that is found in chromosome region 9p24 may contribute to OCD. SLC1A1 encodes for the glutamate transporter, excitatory amino acid carrier-1 (EAAC1). EAAC1 has a central role in preserving normal levels of glutamate in the extrasynaptic space and terminating the action of glutamate at the synapse.[18] In addition, Arnold PD and Dickel DE, showed an interrelation between the glutamate transporter gene SLC1A1 and OCD.[23,24]

Until now numerous studies have been designed to assess the effect of GMAs such as riluzsole, memantine and N-Acetylcysteine as add-on treatment for refractory OCD.[5,25,26,27]

Topiramate is an antiepileptic agent that is effective against both partial and generalized seizures and has some positive psychotropic effects.[28] Topiramate directly inhibits glutamate action through the Amino-3-Hydroxy-5-Methyl-4-Isoxazole Propanoic Acid 9/kainite subtype of glutamate receptors and also potentiate the activity of gamma-aminobutyric acid at nonbenzodiazepine sites.[29] It means that it has antiglutamatergic effects.

Few studies have been conducted to assess the efficacy of adding topiramate to treat refractory OCD. A few case reports and a retrospective, open-label case series showed some beneficial effects in topiramate augmentation for the treatment of resistant OCD.[30,31] In a trial Berlin et al. demonstrated that topiramate augmentation may be beneficial for compulsions but not obsessions.[32] The opposite effects also have been reported on topiramate.[33] With respect to these contradictory results and also because few randomized clinical trials (RCT) have been conducted in this field, we designed a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical study to evaluate the efficacy of topiramate in patients with resistant OCD as an adjunct to SRIs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design

The study was designed as a 12 weeks randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. The patients were recruited from psychosomatic and psychiatric clinics affiliated to the Isfahan University of Medical Science from February 2013 to November 2013.

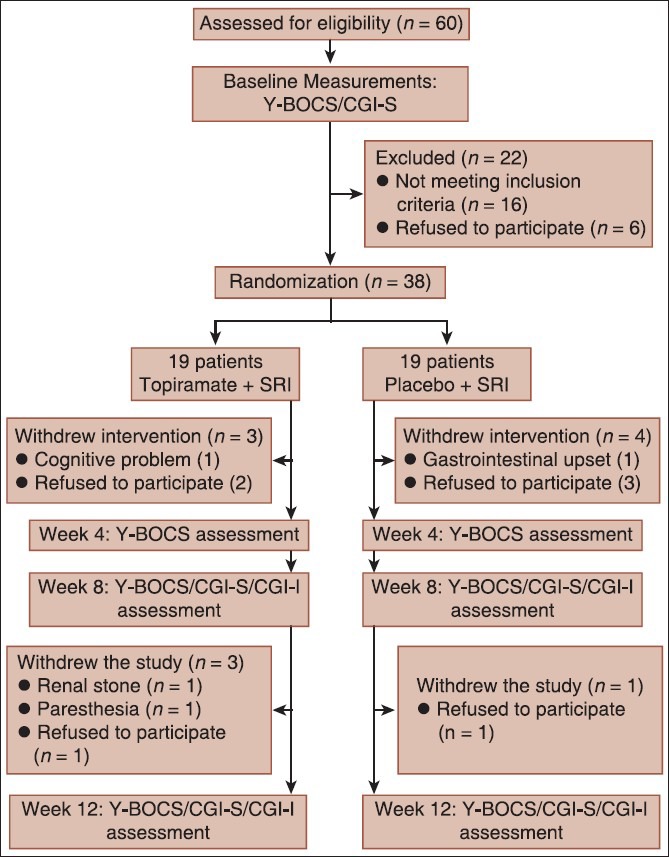

We screened 60 patients totally using convenience sampling (based on exclusion and inclusion criteria). Finally, 38 eligible patients were randomly allocated to either the topiramate or placebo group using random number generator software [Figure 1]. To contemplate blindness, the researcher who assigned patients had no role in the treatment or collection of data, and the examiner who was responsible for the treatment of patients and filling Clinical Global Impression (CGI) scale was not notified about patients’ medication.

Figure 1.

Study profile

The study protocol was explained to patients, and informed consent was obtained. This trial was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Isfahan University of Medical Science and registered in the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials (www.irct.ir, identifier: IRCT 2013012312252N1). All phases of this study were performed about the declaration of Helsinki ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects.

Participants

Men and women aged 22-60 years with refractory OCD and without having any exclusion criteria.

Patients were diagnosed by an experienced psychiatrist using Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, third revision (DSM-IV-TR) criteria for OCD and comorbid conditions.

Exclusion criteria were any uncontrolled medical conditions (like hypertension, diabetes mellitus, etc.), any primary diagnosis of psychotic or bipolar disorder, substance abuse or dependence, current pregnancy or lactation or an intention to get pregnant during the period of intervention, convulsive disorders, suicidal thoughts, previous use of topiramate and past history of having renal stone or being under psychotherapy. From 38 patients that were recruited, seven ones dropped out of the study because of unwillingness or side effects [Figure 1].

Treatment failure is considered as a Y-BOCS score of 16 or greater after at least 12 weeks of SRI treatment with an adequate dose.

Intervention

Patients in the intervention group received topiramate with an initial dose of 25 mg/day which increased 25 mg weekly to a maximum dose of 200 mg/day with respect to patients’ tolerance. Another group received matching placebos. SRIs treatment continued during the study with the same dose as the preintervention phase. Placebo tablets were made in Arya Pharmaceutical Company (Tehran, Iran) with the same shape and color as topiramate tablets. Dosage increase was performed similarly in each of two groups. The mean topiramate dosage was 137.5 mg/day (range, 100-200 mg/day).

Efficacy measures

The patients were interviewed at baseline and every 4 weeks by the psychiatrist using the semi-structural clinical interview of DSM-IV-TR and also assessed via Y-BOCS questionnaire. Symptoms severity was evaluated by the CGI Severity of Illness (CGI-S) scale at the beginning and on weeks 8 and 12. Clinical improvement on weeks 8 and 12 was evaluated via CGI Improvement (CGI-I) scale.

The primary efficacy measures were the changes in the Y-BOCS and also the response rate in each of two groups at the end point. We considered treatment response as ≥25% reduction in the Y-BOCS score.

The Y-BOCS is a 10 items reliable clinician-rated instrument. Each item is rated from 0 to 4 so total score ranges from 0 to 40. Each of CGI-S and CGI-I scales has a 7-point scale.

Safety assessments

All patients were screened through a physical examination and medical history (with special attention to not having past personal or family history of renal stone) before the study. To evaluate safety and tolerability of topiramate, the researcher asked the patients to report adverse effects, and also they were assessed through rates of premature termination due to adverse events.

Statistical analysis

Baseline demographic characteristics are shown as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or number (%). Independent samples t-test and Fisher's exact test were used to compare quantitative and qualitative variables between topiramate and placebo groups respectively. To assess the significance of differences in the rate of adverse events between the two groups the Fisher's exact test was used.

To evaluate differences of Y-BOCS score in weeks 0, 4, 8 and 12 and differences of CGI-S in weeks 0, 8 and 12 repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used. It was also performed to evaluate the effect of treatment, sex and duration of illness on the changes over time. For CGI-I paired-samples t-test was used to compare the differences in two measurements. Furthermore, Independent samples t-test was performed to compare CGI-I changes between the two groups.

The Statistical Package for Social Sciences software (SPSS) version 19.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) were used for analyses. P < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

RESULTS

Patient's characteristics

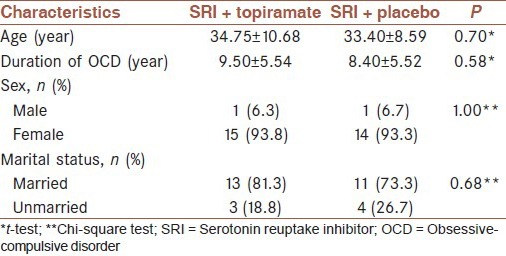

The mean ± SD of age for the 38 patients was 34.53 ± 8.59 years (range, 22-60 years). Thirty-six patients (93.5%) were women, and the remaining were men. The patients were recruited in the topiramate (n = 19) or placebo (n = 19) group. There were no statistically significant differences respecting age, sex, marital status and duration of illness between the groups [Table 1]. Similarly, The Y-BOCS and CGI-S scale scores were comparable at the beginning of the study.

Table 1.

Comparison of baseline characteristics in topiramate and placebo groups

Three patients (15.7%) from topiramate group and four patients (21.05%) from the placebo group withdrew the trial before week 4. One patient from the placebo group and three ones from topiramate group left the study at the end of month 2 [Figure 1].

Efficacy results

Within-group analyses using repeated measure ANOVA demonstrated that in the topiramate group there are significant differences of the Y-BOCS (P < 0.001) and the CGI-S scale score (P < 0.001) during the study but not in the CGI-I (P = 0.121). However, in the placebo group, within-group differences were not significant for Y-BOCS and CGI-I but was significant for CGI-S (P = 0.020).

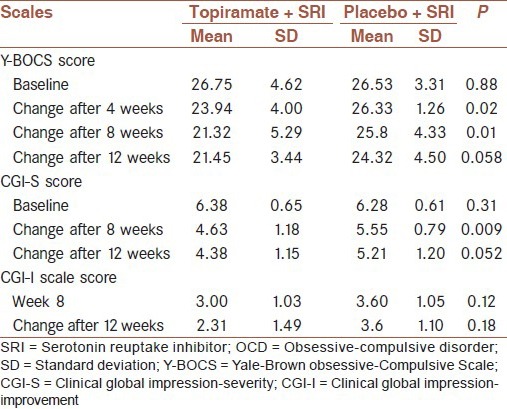

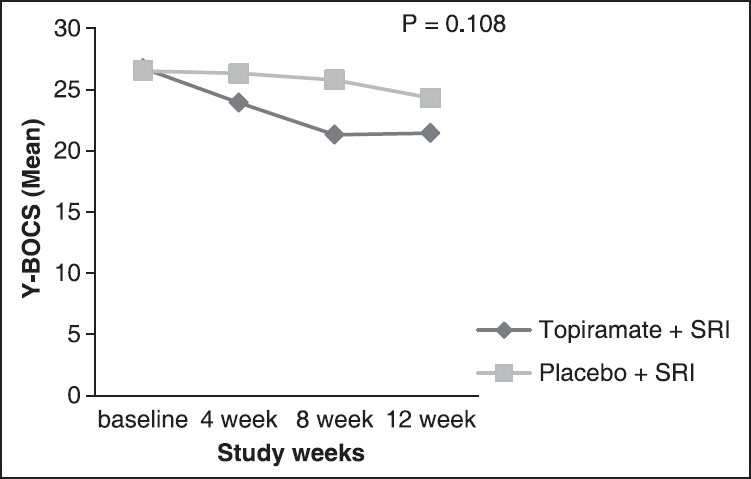

Pairwise analyses of changes for each time point are reviewed in Table 2. As shown, improvement in the Y-BOCS in the topiramate group was significantly different from that of the placebo group at the end of week 4 (P = 0.01) and especially at the end of week 8 (P = 0.01), but not at the study end point [P = 0.058, Figure 2]. The difference in CGI-S scale score was statistically significant in week 8 (P = 0.009), but not in week 12 (P = 0.052).

Table 2.

Analayses of changes in the OCD symptoms severity, improvement indices, in topiramate and placebo groups

Figure 2.

Trend of changes of Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale over time in topiramate group comparing placebo group

To use all the data and adjust effects of dropping outs, we used EM algorithm to missing value imputation; the results weren’t different.

Full clinical response in the topiramate group was 53.84% (7/13) but in the placebo group, two patients (14.28%) had full clinical response, this was not statistically significant (P = 0.054).

Safety and tolerability

Topiramate was not well tolerated by some patients. The adverse effects reported during the study were renal stone (n = 1), paresthesia (n = 5), micturation frequency (n = 2), decreased appetite (n = 1), weight loss (n = 3), cognitive problems (n = 3) in the topiramate group and gastrointestinal disturbance (n = 2) in the placebo group (P > 0.05). At the end of month 2, two patients from the topiramate group withdrew the trial because of adverse events.

DISCUSSION

This study did not show superior efficacy of topiramate over placebo as an add-on agent for treatment-refractory OCD. However, reduction of Y-BOCS was significantly higher in the topiramate group comparing placebo for the first 2 months. Full clinical response in the topiramate group was almost significantly higher than a placebo group.

As the same with the study performed by Mowla, et al. and an open-label case series,[28,31] our finding for the first two, emphasize that topiramate may be an useful augmentation for patients with refractory OCD; However it wasn’t beneficial at the end of our study. In another RCT by Berlin, et al. topiramate augmentation was an effective strategy to improve compulsions but not obsessions.[32] The opposite result was also demonstrated by Ozkara, et al. whereas they reported topiramate related OCD.[33]

It is conceivable that the usefulness of topiramate for the first 2 months relates to the antianxiety effects of topiramate. Unpredictable psycho-social stresses might have been the factor to stop the response to the treatment. The inefficacy of topiramate at the end of the study might have been a temporary phenomenon. If the study had been continued for a longer time (a few more months), the efficacy of this strategy might have been demonstrated. Higher doses might have been necessary to continue the efficacy of topiramate. But, since the patients in this study couldn’t tolerate doses higher than 200 mg, the usefulness of topiramate wasn’t observed at the end of the 3rd month.

About adverse effects, in our study, the most common, but not significant side effect was paresthesia. Although Ko, et al. trial and Afshar, et al. study showed paresthesia was significantly higher in patients taking topiramate compared with placebo as adjunctive therapy in schizophrenia patients.[34,35]

In our study one patient receiving topiramate, who had full clinical response at the end of 2nd month, had to leave the study because of renal stone.

One of our study limitations was a high rate of premature termination. This is similar to Berlin et al. trial[32] where the rate of dropping outs was high too. Other study limitations include a small number of cases, short follow duration and limited dose of topiramate. Significant results might have been observed if the study had included longer follow-up and larger sample volume.

Patients did not tolerate doses above 200 mg/day, whereas doses up to 400 mg/day had been used in some studies before. Likewise, in the Berlin et al. study topiramate was not well tolerated, and they had to reduce the dose in about 39% of patients.[32] Higher doses of topiramate may lead to getting more confirmatory results.

CONCLUSION

Although our study didn’t show topiramate as a useful option to augment standard treatment in treatment-resistant OCD patients, but it may be effective for some patients and results are still contradictory and further large-scale controlled studies need to prove this.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors have contributed in designing and conducting the study. HA and SHA and EZ collected the data. BM analyzed data. All authors have assisted in preparation of the first draft of the manuscript or revising it critically for important intellectual content. All authors have read and approved the content of the manuscript and confirmed the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

This work was partially supported by Isfahan University of Medical Sciences (IUMS), Deputy of Research. The authors wish to thank all physician and nurses of psychosomatic research centre and Nour & Aliasghar hospital of Isfahan.

Footnotes

Source of Support: This work was partially supported by Isfahan University of Medical Sciences (IUMS), Deputy of Research.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ruscio AM, Stein DJ, Chiu WT, Kessler RC. The epidemiology of obsessive-compulsive disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Mol Psychiatry. 2010;15:53–63. doi: 10.1038/mp.2008.94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stein DJ, Ipser JC, Baldwin DS, Bandelow B. Treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder. CNS Spectr. 2007;12:28–35. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vasile D, Vasiliu O, Mangalagiu AG, Gabriela Ojog D. Augmentation strategies in selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors resistant obsessive-compulsive disorder: A systematic literature review. Ther Pharmacol Clin Toxicol. 2011;15:83–92. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Albert U, Aguglia A, Bramante S, Bogetto F, Maina G. Treatment-resistant obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD): Current knowledge and open questions. Clin Neuropsychiatry. 2010;10:19–30. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Afshar H, Roohafza H, Mohammad-Beigi H, Haghighi M, Jahangard L, Shokouh P, et al. N-acetylcysteine add-on treatment in refractory obsessive-compulsive disorder: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2012;32:797–803. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0b013e318272677d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pallanti S, Quercioli L. Treatment-refractory obsessive-compulsive disorder: Methodological issues, operational definitions and therapeutic lines. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2006;30:400–12. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2005.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tolin DF, Maltby N, Diefenbach GJ, Hannan SE, Worhunsky P. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for medication nonresponders with obsessive-compulsive disorder: A wait-list-controlled open trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65:922–31. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v65n0708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tundo A, Salvati L, Busto G, Di Spigno D, Falcini R. Addition of cognitive-behavioral therapy for nonresponders to medication for obsessive-compulsive disorder: A naturalistic study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68:1552–6. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v68n1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Anand N, Sudhir PM, Math SB, Thennarasu K, Janardhan Reddy YC. Cognitive behavior therapy in medication non-responders with obsessive-compulsive disorder: A prospective 1-year follow-up study. J Anxiety Disord. 2011;25:939–45. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2011.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sareen J, Kirshner A, Lander M, Kjernisted KD, Eleff MK, Reiss JP. Do antipsychotics ameliorate or exacerbate Obsessive Compulsive Disorder symptoms? A systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2004;82:167–74. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2004.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bloch MH, Landeros-Weisenberger A, Kelmendi B, Coric V, Bracken MB, Leckman JF. A systematic review: Antipsychotic augmentation with treatment refractory obsessive-compulsive disorder. Mol Psychiatry. 2006;11:622–32. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Skapinakis P, Papatheodorou T, Mavreas V. Antipsychotic augmentation of serotonergic antidepressants in treatment-resistant obsessive-compulsive disorder: A meta-analysis of the randomized controlled trials. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2007;17:79–93. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2006.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dold M, Aigner M, Lazenberger R, Kasper S. Antipsychotic augmentation of serotonin reuptake inhibitors in treatment-resistant obsessive-compulsive disorder.: A meta-analysis of double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trials. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2013;16:557–74. doi: 10.1017/S1461145712000740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marazziti D, Golia F, Consoli G, Presta S, Pfanner C, Carlini M, et al. Effectiveness of long-term augmentation with citalopram to clomipramine in treatment-resistant OCD patients. CNS Spectr. 2008;13:971–6. doi: 10.1017/s1092852900014024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Diniz JB, Shavitt RG, Pereira CA, Hounie AG, Pimentel I, Koran LM, et al. Quetiapine versus clomipramine in the augmentation of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors for the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder: A randomized, open-label trial. J Psychopharmacol. 2010;24:297–307. doi: 10.1177/0269881108099423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bruno A, Micò U, Pandolfo G, Mallamace D, Abenavoli E, Di Nardo F, et al. Lamotrigine augmentation of serotonin reuptake inhibitors in treatment-resistant obsessive-compulsive disorder: A double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Psychopharmacol. 2012;26:1456–62. doi: 10.1177/0269881111431751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Decloedt EH, Stein DJ. Current trends in drug treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2010;6:233–42. doi: 10.2147/ndt.s3149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pittenger CH, Bloch M, Wegner R, Teitelbaum C, Krystal J, Coric V. Glutamatergic dysfunction in obsessive-compulsive disorder and the potential clinical utility of glutamate-modulating agents. Prim Psychiatry. 2006;13:65–77. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rosenberg DR, Mirza Y, Russell A, Tang J, Smith JM, Banerjee SP, et al. Reduced anterior cingulate glutamatergic concentrations in childhood OCD and major depression versus healthy controls. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2004;43:1146–53. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000132812.44664.2d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rosenberg DR, MacMaster FP, Keshavan MS, Fitzgerald KD, Stewart CM, Moore GJ. Decrease in caudate glutamatergic concentrations in pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder patients taking paroxetine. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2000;39:1096–103. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200009000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chakrabarty K, Bhattacharyya S, Christopher R, Khanna S. Glutamatergic dysfunction in OCD. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2005;30:1735–40. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McGrath MJ, Campbell KM, Parks CR, Burton FH. Glutamatergic drugs exacerbate symptomatic behavior in a transgenic model of comorbid Tourette's syndrome and obsessive-compulsive disorder. Brain Res. 2000;877:23–30. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)02646-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Arnold PD, Sicard T, Burroughs E, Richter MA, Kennedy JL. Glutamate transporter gene SLC1A1 associated with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63:769–76. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.7.769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dickel DE, Veenstra-VanderWeele J, Cox NJ, Wu X, Fischer DJ, Van Etten-Lee M, et al. Association testing of the positional and functional candidate gene SLC1A1/EAAC1 in early-onset obsessive-compulsive disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63:778–85. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.7.778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Coric V, Taskiran S, Pittenger C, Wasylink S, Mathalon DH, Valentine G, et al. Riluzole augmentation in treatment-resistant obsessive-compulsive disorder: An open-label trial. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;58:424–8. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.04.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Poyurovsky M, Weizman R, Weizman A, Koran L. Memantine for treatment-resistant OCD. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:2191–2. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.11.2191-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stewart SE, Jenike EA, Hezel DM, Stack DE, Dodman NH, Shuster L, et al. A single-blinded case-control study of memantine in severe obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2010;30:34–9. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0b013e3181c856de. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mowla A, Khajeian AM, Sahraian A, Chohedri AH, Kashkoli F. Topiramate augmentation in resistant OCD: A double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial. CNS Spectr. 2010;15:613–7. doi: 10.1017/S1092852912000065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ketter TA, Wang PW. Anticonvalsants: Gabapentine, levetiracetam, pregabalin, tiagabin, topiramate, zonisamide. In: Sadock BJ, Sadock VA, Ruiz P, editors. Kaplan and Sadock's Comprehensive Textbook of Psychiatry. 9th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2009. p. 3029. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Van Ameringen M, Mancini C, Patterson B, Bennett M. Topiramate augmentation in treatment-resistant obsessive-compulsive disorder: A retrospective, open-label case series. Depress Anxiety. 2006;23:1–5. doi: 10.1002/da.20118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hollander E, Dell’Osso B. Topiramate plus paroxetine in treatment-resistant obsessive-compulsive disorder. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2006;21:189–91. doi: 10.1097/01.yic.0000199453.54799.cc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Berlin HA, Koran LM, Jenike MA, Shapira NA, Chaplin W, Pallanti S, et al. Double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of topiramate augmentation in treatment-resistant obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72:716–21. doi: 10.4088/JCP.09m05266gre. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ozkara C, Ozmen M, Erdogan A, Yalug I. Topiramate related obsessive-compulsive disorder. Eur Psychiatry. 2005;20:78–9. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2004.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ko YH, Joe SH, Jung IK, Yalug I. Topiramate as an adjuvant treatment with atypical antipsychotics in schizophrenic patients experiencing weight gain. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2005;28:169–75. doi: 10.1097/01.wnf.0000172994.56028.c3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Afshar H, Roohafza H, Mousavi G, Golchin S, Toghianifar N, Sadeghi M, et al. Topiramate add-on treatment in schizophrenia: A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. J Psychopharmacol. 2009;23:157–62. doi: 10.1177/0269881108089816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]