Abstract

Most adults remain chronically infected with HHV-6 after resolution of a primary infection in childhood, with the latent virus held in check by the immune system. Iatrogenic immunosuppression following solid organ transplantation (SOT) or hematopoetic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) can allow latent viruses to reactivate. HHV-6 reactivation has been associated with increased morbidity, graft rejection, and neurological complications post-transplantation. Recent work has identified HHV-6 antigens that are targeted by the CD4+ and CD8+ T cell response in chronically infected adults. T cell populations recognizing these targets can be expanded in vitro and are being developed for use in autologous immunotherapy to control post-transplantation HHV-6 reaction.

Introduction

The increasing clinical importance of HHV-6 demands effective treatment options. Currently, individuals with complicated HHV-6 infection or reactivation are treated with ganciclovir or similar drugs approved for managing other viral infections [1]. However these drugs have significant toxicity [2] and in some cases are ineffective against HHV-6 [3]. Immunotherapies based on antibodies, expanded T cells, or vaccines potentially could provide an alternative or adjunctive approach to controlling HHV-6 infection. Immunotherapy for human herpesviruses has been in development since the early 1990’s [4], and has been shown to be a safe and practical approach to controlling related human herpesviruses human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) [5], Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) [6,7] and herpes simplex virus (HSV) [8]. For HHV-6, little is known about the immune mechanisms that control infection, and current understanding is based largely on a few studies and extrapolation from HCMV [9]. Here we review recent progress in characterizing the immune response to HHV-6 and discuss implications for development of immunotherapies in immunocompromised patients.

Challenges to characterizing the immune response to HHV-6

The lack of a basic understanding of the immune response to HHV-6 has delayed the development of HHV-6 specific immunotherapies. Several aspects of HHV-6 biology interfere with straightforward application of conventional approaches to characterizing antiviral immunity. First, two closely related viruses HHV-6A and HHV-6B have been treated as a single species until very recently [10]. Mounting evidence suggests important differences in the biology of these two viruses and the immune response that they induce [11], but in general they have not been distinguished in studies of the immune response to HHV-6. Second, antibody titers to HHV-6 and frequencies of T cells recognizing HHV-6 are low, making detection of these responses challenging [12]. Blood samples obtained during active viremia might exhibit higher antibody titers or T cell responses, but symptomatic viremia occurs primarily in young children or immunosuppressed patients from whom sufficient blood samples are difficult to obtain. Third, HHV-6 is a lymphotropic virus that prefers T cells for replication, but also is capable of infecting a variety of antigen presenting cells [1,13]. Profound effects on the normal function of both infected T cells and infected antigen presenting cells have been demonstrated [14–17], and these effects interfere with ex vivo analyses. Finally, HHV-6 infection is restricted to humans and closely-related primates [18,19], so the lack of a small animal model has inhibited detailed mechanistic studies. Despite these limitations, recently there have been notable advances in defining HHV-6-specific T cell responses and in developing approaches to adoptive immunotherapy.

HHV-6B protective immunity

The observation that primary HHV-6B infection is a mild febrile disease from which most children recover rapidly without complications suggests that protective HHV-6B immune responses are commonly elicited. After primary infection, HHV-6B is able to persist as a chronic or latent infection controlled by the adaptive immune response. The virus can reactivate under conditions of deficient cell-mediated immunity [20]. Although immunity to HHV-6B could evolve over time, there is evidence that lifelong responses to HHV-6B are imprinted very early after the first onset of HHV-6B infection [21]. Neonates are usually protected from HHV-6B infection by maternal-derived antibodies until titers wane over 3–9 months after birth, making older children susceptible to infection [22]. Primary infection occurs usually before the second year of age, and induces antibodies that persist throughout life [22]. Evidence that T cells are required to control HHV-6B replication is inferred from persistent HHV-6B viral replication in immunosuppressed patients who do not have proliferative T cell responses [20].

Antibody responses

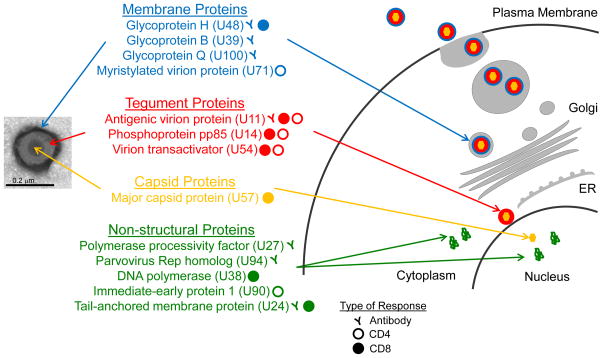

Most studies of the antibody response to HHV-6 have aimed to develop diagnostic methods that differentiate between the three closely-related roseoloviruses, HHV-6A, HHV-6B and HHV-7. Little is known about the range of antigens targeted by antibodies recognizing these viruses [23,24]. A few HHV-6 antigens prominently targeted by the antibody response have been identified. These include the major antigenic virion protein U11 [25], the major glycoproteins gH (U48) [26,27] and gQ (U100) [28], the polymerase processivity factor (U27) [29], the late antigen U94 [30], and the tail-anchored membrane protein U24 [31,32] (Figure 1). Serological assays that utilize U11 as antigen are in development for the definition of roseolovirus-specific antibodies. Neutralizing antibodies have been found mainly after primary infection and in transplant recipients but also in some healthy adult donors, which might indicate subclinical reactivation of the virus [33]. Monoclonal neutralizing antibodies targeting gH [34–36], gQ [37] and gB [38] have been described.

Figure 1. Targets of the adaptive immune response to HHV-6.

Antibody and T cell responses target the viral surface membrane, tegument, and capsid components of the virion as well as non-structure proteins expressed in infected cells. Inset (left) shows a purified viral particle with components indicated, and cartoon (right) shows intracellular locations for the expected stepwise viral assembly process.

T cell responses

The T cell response to HHV-6 mostly has been characterized using peripheral blood from healthy adults. Responding T cells, measured as the number of IFN-γ producing cells, are present at low frequency (on the order of a few cells per 1000 (or <0.2%) [12,39,40], which contrasts sharply with the stronger responses that are observed for HCMV (up to 4%) [41]. T cell responses have been reported to be higher in HSCT patients [42], but few studies have focused on this population. Despite the low frequency of responding T cells in healthy adults, strong CD4+ and CD8+ T cell proliferative responses are observed [43–45], primarily restricted to memory cells. Proliferation of HHV-6-specific T cells in response to viral antigen allows these low-frequency T cell populations to be expanded in vitro for detailed study. The expanded population consists mainly of CD4+ T cells that secrete IFN-γ and exhibit cytotoxic capacity [12,39,46]. A prominent sub-population secretes IL-10 [12,47]. IL-4 and low amounts of IL-2 also are also produced [12], a profile similar to that reported in serum of children with roseola [48]. The reason for CD4+ T cell skewing and limited CD8+ T cells in expanded populations is not clear. The lower frequency of responding CD8+ T cells in blood (~10−5) certainly is a factor [40], but viral evasion mechanisms also might be responsible.

Shortly after the discovery of HHV-6, the immunosuppressive properties of this virus were recognized. Initially it was reported that HHV-6 arrests IL-2 synthesis and T cell proliferation [49,50]. Subsequent studies identified immune modulation by effects in both infected and non-infected cells (reviewed in [51]). In infected CD4+ T cells, HHV-6 induces apoptosis [52], inhibition of IL-2 synthesis [14], cell cycle arrest [16], and TCR and MHC-I down modulation [11]. In antigen-presenting cells, HHV-6 induces MHC-I down-modulation [53] and reduces the ability of these cells to present antigens and activate T cells [11]. In addition, IL-10 secreted by CD4+ T cells responding to HHV-6 modulates proliferation of other T cell populations [47]. Different subsets of regulatory T cells (Tregs) have been observed in vitro after HHV-6-specific expansion or cloning [12,39,54].

Targets of the T cell response to HHV-6

The HHV-6 genome encodes ~100 proteins, and many of them are >1000 amino acids in length, making the identification of immunodominant epitopes a laborious and time consuming task. Information on the particular peptide epitopes recognized by T cells is required for indentification, characterization, and modulation of T responses specific to HHV-6 as compared to closely-related viruses. Approaches used to limit the number of antigens/peptides to screen have included focusing on HHV-6 proteins present at high levels in virus preparations [12], or HHV-6 homologues of antigens defined for HCMV [39,40]. Our group used the first approach to define 11 CD4+ T cell epitopes [12]. These derived from 4 virion proteins (the major capsid protein U57, the tegument proteins U11 and U14, and the glycoprotein U48) and from a non-structural protein (DNA polymerase U38) (Table 1). CD4+ T cells expanded with peptides corresponding to these epitopes responded to APC treated with virus preparations and produced IFN-γ and expressed markers associated with cytotoxic potential. Using the second approach, Martin et al were able to expand CD8+ T cell lines and clones that showed reactivity to peptides from tegument proteins U11 and U54 and showed pro-inflammatory and cytotoxic capabilities [40]. Also using the second approach and T cell lines expanded in vitro, Gerdemann et al demonstrated T cell responses to peptide epitopes derived from the immediate-early protein U90, the tegument proteins U11, U14 and U54, and the myristylated virion protein U71 [39]. The expanded T cells produced IFN-γ and TNF-α and killed antigen-pulsed autologous target cells. Although the expanded T cell populations consisted mainly of CD4+ T cells, epitopes were identified only for the minor component of CD8+ T cells. Additional CD8+ T cell epitopes in U90 were identified recently by Iampietro et al [55]. Overall twelve CD8+ T cell epitopes were defined: three from U11, two from U54 [40], six from U90 and one from U14 [39], to complement the twelve CD4+ T cell epitopes described above. In agreement with earlier reports, many of the mapped T cell responses are crossreactive between HHV-6A and HHV-6B, and so cannot be used as markers of virus-specific responses. Non-crossreactive responses have been reported for capsid antigens, but specific epitopes were not defined [56]. Additionally, three putative HHV-6 epitopes have been defined by virtue of cross-reactivity with human self antigens (Table 1). T cell responses to a HHV-6 U24 peptide that shares homology with the multiple-sclerosis autoantigen myelin basic protein (MBP) have been reported, but any significance of this crossreactive response in multiple sclerosis is controversial [32,57]. CD4+ T cells recognizing the diabetes-associated glutamic acid decarboxylase islet autoantigen GAD95 were shown to cross-react with a similar peptide sequence from HHV-6A U95 [58], but whether these cells recognize naturally processed antigens is not known. A summary of HHV-6 proteins targeted by CD4+ and CD8+ T cell responses is shown in Figure 1, with specific epitopes listed in Table 1.

HHV-6B reactivation after solid organ transplantation

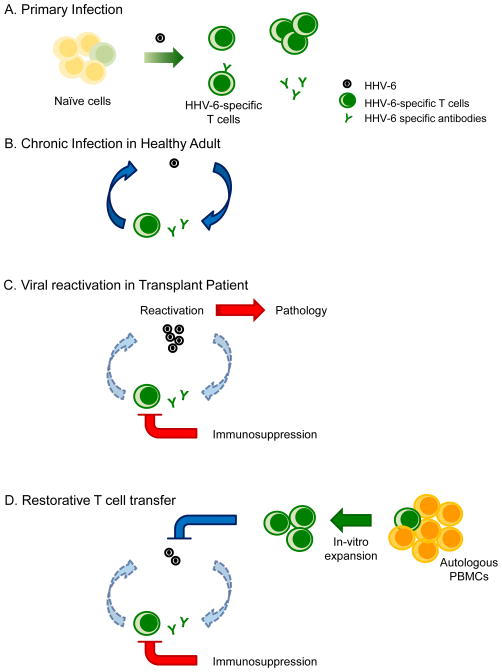

In the period following immunosuppression, transplant recipients are highly susceptible to common viruses such as herpesviruses, adenoviruses, and seasonal viruses like influenza. HHV-6 reactivation, mostly by HHV-6B [59], occurs in over 40% of HSCT and in up to 60% of solid organ transplant (SOT) recipients [59] during the first weeks after transplantation. HHV-6 reactivation in HSCT patients is associated with graft-versus-host disease, delayed engraftment [60], and CNS dysfunction, including encephalitis that may have long term effects [61–63]. In SOT patients, HHV-6B reactivation is associated with prolonged anti-HHV-6 immunosuppression [64], fever, rash, hepatitis, pneumonitis, encephalitis and colitis [59]. In the months after transplantation, T cell proliferative responses to HHV-6 are absent in most individuals. By comparison, proliferative responses to HCMV develop over several weeks (although they do not reach levels observed in healthy donors) [64]. Autologous immune enhancement therapy, in which pre-transplantation T cell populations are expanded ex vivo and re-introduced (Figure 2), could provide a way to boost the post-transplantation T cell response and help control HHV-6 reactivation.

Figure 2. Autologous immune enhancement therapy.

A) Primary infection with HHV-6 virus elicits antibody and T cell responses. B) During chronic infection virus levels are controlled by antibody and T cell responses. C) In transplantation patients, iatrogenic immunosuppression interferes with immune control of HHV-6 and allows virus reactivation with consequent pathology. D) HHV-6-specific T cells expanded in vivo can be reintroduced after transplantation to control virus reactivation.

Autologous immune enhancement therapy

Susceptibility to HHV-6B and other common viruses is associated with deficiency of T cell responses in immunosuppressed individuals [20,65]. Restoration of protective T cell responses against other herpesviruses such as HCMV and EBV has been achieved by transfer of T cells expanded in vitro using purified virus, recombinants proteins, or synthetic versions of known immunodominant antigens to stimulate T cell proliferation [5]. A turning point in the immunotherapy to HHV-6B has been the identification of immunodominant antigens and the demonstration that HHV-6B-specific T cells can be expanded in large numbers if cytokines that support T cell expansion are provided in culture [12,39,66]. This knowledge has been rapidly transferred to a small clinical trial that attempted the reconstitution of immune responses to HHV-6B, HCMV, BK virus, EBV, and adenovirus by expansion of PBMCs with a mixture of peptides from these viruses [67]. The Phase I clinical trial showed that adoptive transfer of peptide-expanded T cells for these viruses was safe, did not induce high levels of cytokines, and did not induce allo-specific responses. Expansion of HHV-6B T cells was performed with overlapping peptides of the immediate early protein 1 (U90) and the tegument proteins U11 and U14 shown to be important targets of the HHV-6B T cell response [12,39,40]. The transferred T cell population consisted of ~60% CD4+ and 35% CD8+ T cells. Although T cell lines were generated from a relatively small number of cells (15 million), and a large number of peptides were included (opening the possibility of peptide competition for binding to MHC proteins), almost 30% of the developed T cell lines had responses to all five 5 viruses and 70% to at least 3 viruses. More important and striking was that virus levels were reduced after adoptive transfer of T cells, and this reduction was accompanied by an increase in the number of IFN-γ producing cells. Moreover, three patients that received expanded T cells as prophylaxis were protected from virus reactivation beyond 3 months after the adoptive transfer. However, as indicated by the authors, the clinical trial did not have enough participants to support a claim that reduction in virus levels was a result of infused of T cells rather than other host or viral factors. The T cell population transferred was highly enriched in CD4+ T cells with a minor component of CD8+ T cells, which may have been beneficial since allo-specific disease has been associated with higher frequency of HHV-6-specific CD8+ T cells [42].

Future Directions

Although the outcome of the first human HHV-6 immunotherapy by transfer of in vitro expanded T cells was favorable, we do not know the epitope specificity of the transferred cells, how the transferred cells contributed to the virus control, or even if the antigens used to expand these cells are the major mediators of protective immune responses. Although a handful of both CD4+ and CD8+ T cell epitopes have been identified, in most cases these were identified by reference to homologous HCMV antigens, and it is not clear how broadly these represent the overall HHV-6-specific response. A better understanding of the repertoire of peptides recognized by HHV-6-specific T cells would provide additional possibilities for in vitro T cell expansion for adoptive immunotherapy. In general studies of HHV-6 T cell epitopes have been performed using blood samples from healthy but chronically-infected adults. Characterization of the T cell responses induced by primary infection in childhood, or by virus reactivation in transplantation patients where viremia is controlled, would be helpful to identify protective epitopes. Experiments using in vitro expanded T cell populations have identified both productive and suppressive responses, but these have not been associated with particular epitopes. Several in vitro studies have suggested that IL-10 produced by CD4+ T cells could play a major role in limiting the expansion of both CD4 and CD8 T cell responses. A better understanding of various types and functions of T cells recognizing HHV-6 antigens might allow beneficial responses to be preferentially expanded. New adoptive immunotherapy protocols incorporating this information might allow protection to be obtained with a lower number of transferred cells, limiting the time and resources needed for expansion and reducing the possibility of expansion of unwanted cell responses.

Conclusions

Important advances in defining the T cell response to HHV-6 have allowed the first clinical trial in HHV-6 immmunotherapy. Although responses to HHV-6 antigens are present in PBMCs at low frequency, CD4+ and CD8+ T cell antigens have been identified from a variety of viral proteins. Sufficient numbers of cells for immunotherapies can be generated if cells are expanded in medium containing antigen and cytokines. Promising results from a clinical trial reported a decrease in virus load in patients with HHV-6 reactivation after transfer of in vitro expanded T cells, suggesting that immunotherapies for HHV-6 are possible without large numbers or antigenic specificities of responding cells. Whether the observed reduction in virus load was mediated by CD4+ or CD8+ T cells and the epitope specificity of these responses remains unknown. Since HHV-6 T cell reactivity has been associated with multiple sclerosis and other autoimmune diseases, future studies should distinguish protective and allo-specific epitopes to minimize potentially cross-reactive autoimmune responses. Nevertheless, efforts to improve the efficacy of HHV-6 therapies will greatly benefit the populations at risk of severe viral disease.

Table I.

CD4 and CD8 T cell epitopes defined for HHV-6

| Epitope | HLA1 | ORF2 | Protein | Evidence3 | Specificity4 | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GILDFGVKL | A2 | U11 | Antigenic virion protein | Cyto; grzB | 6B | [40] |

| MLWYTVYNI | A2 | U11 | Antigenic virion protein | Cyto; grzB; Tet | 6B | [40] |

| SLMSGVEPL | A2 | U11 | Antigenic virion protein | Cyto; grzB | 6B | [40] |

| ILYGPLTRI | A2 | U54 | Virion transactivator | CTL; Cyto; grzB; Tet | 6B | [40] |

| LLCGNLLIL | A2 | U54 | Virion transactivator | Cyto; grzB | 6B | [40] |

| TEMMNDARL | B40 | U14 | Phosphoprotein pp85 | CTL; Cyto | n.d. | [39] |

| FESLLFPEL | B40 | U90 | Immediate-early protein 1 | CTL; Cyto | n.d. | [39] |

| VEESIKEIL | B40 | U90 | Immediate-early protein 1 | CTL; Cyto | n.d. | [39] |

| CIQSIGASV | A2 | U90 | Immediate-early protein 1 | CTL; Cyto | 6A/6B | [55] |

| CYAKMLSGK | A3 | U90 | Immediate-early protein 1 | CTL; Cyto | 6B/6A? | [55] |

| STSMFILGK | A3 | U90 | Immediate-early protein 1 | CTL; Cyto | 6B/6A? | [55] |

| NPEISNKEF | B7 | U90 | Immediate-early protein 1 | CTL; Cyto | 6B/6A? | [55] |

| SLESYSASKAFSVPENG | DR1 | U11 | Antigenic virion protein | Cyto | 6A/6B | [12] |

| RDNSYMPLIALSLHENG | DR1 | U14 | Phosphoprotein pp85 | Cyto | 6A/6B | [12] |

| VVGKYSLQDSVLVVRLF | DR1 | U38 | DNA polymerase | Cyto; Tet | 6A/6B | [12] |

| GIYYIRVVEVRQMQYDN | DR1 | U48 | Glycoprotein H | Cyto; Tet | 6A/6B | [12] |

| VDEEYRFISDATFVDET | DR1 | U48 | Glycoprotein H | Cyto; Tet | 6A/6B | [12] |

| TRPLYITMKAQKKNSRI | DR1 | U54 | Virion transactivator | Cyto; Tet | 6A/6B | [12] |

| FKSLIYINENTKILEVE | DR1 | U57 | Major capsid protein | Cyto; Tet | 6A/6B | [12] |

| IRHHVGIEKPNPSEGEA | DR1 | U57 | Major capsid protein | Cyto | 6A/6B | [12] |

| SLLSIMTLAAMHSKLSP | DR1 | U57 | Major capsid protein | Cyto; Tet | 6A/6B | [12] |

| TTNPWASLPGSLGDILY | DR1 | U57 | Major capsid protein | Cyto; Tet | 6A/6B | [12] |

| DPSRYNISFEALLGIYS | DR1 | U57 | Major capsid protein | Cyto; Tet | 6A/6B | [12] |

| KELLQSYVSKNNN | DR53 | U95 | Immediate-early protein | Cyto | 6A?; GAD95 | [58] |

| MDRPRTPPPSYSE | n.d. | U24 | Tail-anchored mb. protein | Prolif; Cyto | 6A/B; MBP | [32] |

| RPRTPPPSY | n.d. | U24 | Tail-anchored mb. protein | Prolif; CTL | 6B?; MBP | [68] |

HLA restriction. HLA-A2 and HLA-B40 are class I MHC proteins recognized by CD8+ T cells. HLA-DR1 and HLA-DR53 are class II MHC proteins recognized by CD4+ T cells. n.d., not defined.

HHV-6 open reading frame

CTL, cytotoxicity (cell killing) assay; Cyto, cytokine release; Grzb, granzyme B release; Prolif, cell proliferation assay; Tet, MHC tetramer staining.

Specificity for HHV-6A or HHV-6B, or self antigens, where defined. ?, presumptive specificity; n.d. not defined.

Highlights.

Chronic HHV-6 infection is controlled by antibody and T cell immune responses

Post-transplantation immunosuppression allows HHV-6 reactivation and pathology

Targets of the immune response to chronic HHV-6 infection have been identified

CD4+ and CD8+ T cells recognizing HHV-6 antigens can be expanded ex vivo

Autologous T cell immunotherapy might prevent post-transplantation viral reactivation

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the US National Institute of Health grant U19-AI10958. We thank the reviewers of the manuscript for helpful suggestions.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References and recommended reading

Papers of particular interest, published within the period of review, have been highlighted as:

• of special interest

•• of outstanding interest

- 1.De Bolle L, Naesens L, De Clercq E. Update on human herpesvirus 6 biology, clinical features, and therapy. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2005;18:217–245. doi: 10.1128/CMR.18.1.217-245.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Biron KK. Antiviral drugs for cytomegalovirus diseases. Antiviral research. 2006;71:154–163. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2006.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zerr DM, Gupta D, Huang ML, Carter R, Corey L. Effect of antivirals on human herpesvirus 6 replication in hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients. Clinical infectious diseases: an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2002;34:309–317. doi: 10.1086/338044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Riddell SR, Watanabe KS, Goodrich JM, Li CR, Agha ME, Greenberg PD. Restoration of viral immunity in immunodeficient humans by the adoptive transfer of T cell clones. Science. 1992;257:238–241. doi: 10.1126/science.1352912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hanley PJ, Bollard CM. Controlling cytomegalovirus: helping the immune system take the lead. Viruses. 2014;6:2242–2258. doi: 10.3390/v6062242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moosmann A, Bigalke I, Tischer J, Schirrmann L, Kasten J, Tippmer S, Leeping M, Prevalsek D, Jaeger G, Ledderose G, et al. Effective and long-term control of EBV PTLD after transfer of peptide-selected T cells. Blood. 2010;115:2960–2970. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-08-236356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Icheva V, Kayser S, Wolff D, Tuve S, Kyzirakos C, Bethge W, Greil J, Albert MH, Schwinger W, Nathrath M, et al. Adoptive transfer of epstein-barr virus (EBV) nuclear antigen 1-specific t cells as treatment for EBV reactivation and lymphoproliferative disorders after allogeneic stem-cell transplantation. Journal of clinical oncology: official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2013;31:39–48. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.8495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Belshe RB, Leone PA, Bernstein DI, Wald A, Levin MJ, Stapleton JT, Gorfinkel I, Morrow RL, Ewell MG, Stokes-Riner A, et al. Efficacy results of a trial of a herpes simplex vaccine. The New England journal of medicine. 2012;366:34–43. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1103151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang FZ, Pellett PE. HHV-6A, 6B, and 7: immunobiology and host response. In: Arvin A, Campadelli-Fiume G, Mocarski E, Moore PS, Roizman B, Whitley R, Yamanishi K, editors. Human Herpesviruses: Biology, Therapy, and Immunoprophylaxis. 2007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ablashi D, Agut H, Alvarez-Lafuente R, Clark DA, Dewhurst S, DiLuca D, Flamand L, Frenkel N, Gallo R, Gompels UA, et al. Classification of HHV-6A and HHV-6B as distinct viruses. Archives of virology. 2014;159:863–870. doi: 10.1007/s00705-013-1902-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dagna L, Pritchett JC, Lusso P. Immunomodulation and immunosuppression by human herpesvirus 6A and 6B. Future virology. 2013;8:273–287. doi: 10.2217/fvl.13.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **12.Nastke MD, Becerra A, Yin L, Dominguez-Amorocho O, Gibson L, Stern LJ, Calvo-Calle JM. Human CD4+ T cell response to human herpesvirus 6. Journal of virology. 2012;86:4776–4792. doi: 10.1128/JVI.06573-11. Report of the first antigen-specific CD4 T cell epitopes from HHV-6, and characterization of the cytokine response to HHV-6 in healthy adults. Development of HLA-DR1 tetramers for the study of CD4+ T cell responses to HHV-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Takahashi K, Sonoda S, Higashi K, Kondo T, Takahashi H, Takahashi M, Yamanishi K. Predominant CD4 T-lymphocyte tropism of human herpesvirus 6-related virus. J Virol. 1989;63:3161–3163. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.7.3161-3163.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Iampietro M, Morissette G, Gravel A, Flamand L. Inhibition of Interleukin-2 Gene Expression by Human Herpesvirus 6B U54 Tegument Protein. Journal of virology. 2014 doi: 10.1128/JVI.02030-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gupta S, Agrawal S, Gollapudi S. Differential effect of human herpesvirus 6A on cell division and apoptosis among naive and central and effector memory CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell subsets. J Virol. 2009;83:5442–5450. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00106-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li L, Gu B, Zhou F, Chi J, Wang F, Peng G, Xie F, Qing J, Feng D, Lu S, et al. Human herpesvirus 6 suppresses T cell proliferation through induction of cell cycle arrest in infected cells in the G2/M phase. Journal of virology. 2011;85:6774–6783. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02577-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smith AP, Paolucci C, Di Lullo G, Burastero SE, Santoro F, Lusso P. Viral replication-independent blockade of dendritic cell maturation and interleukin-12 production by human herpesvirus 6. Journal of virology. 2005;79:2807–2813. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.5.2807-2813.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Santoro F, Kennedy PE, Locatelli G, Malnati MS, Berger EA, Lusso P. CD46 is a cellular receptor for human herpesvirus 6. Cell. 1999;99:817–827. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81678-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leibovitch E, Wohler JE, Cummings Macri SM, Motanic K, Harberts E, Gaitan MI, Maggi P, Ellis M, Westmoreland S, Silva A, et al. Novel marmoset (Callithrix jacchus) model of human Herpesvirus 6A and 6B infections: immunologic, virologic and radiologic characterization. PLoS pathogens. 2013;9:e1003138. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang FZ, Linde A, Dahl H, Ljungman P. Human herpesvirus 6 infection inhibits specific lymphocyte proliferation responses and is related to lymphocytopenia after allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Bone marrow transplantation. 1999;24:1201–1206. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1702058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koide W, Ito M, Torigoe S, Ihara T, Kamiya H, Sakurai M. Activation of lymphocytes by HHV-6 antigen in normal children and adults. Viral Immunol. 1998;11:19–25. doi: 10.1089/vim.1998.11.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Okuno T, Takahashi K, Balachandra K, Shiraki K, Yamanishi K, Takahashi M, Baba K. Seroepidemiology of human herpesvirus 6 infection in normal children and adults. Journal of clinical microbiology. 1989;27:651–653. doi: 10.1128/jcm.27.4.651-653.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Balachandran N, Amelse RE, Zhou WW, Chang CK. Identification of proteins specific for human herpesvirus 6-infected human T cells. Journal of virology. 1989;63:2835–2840. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.6.2835-2840.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yamamoto M, Black JB, Stewart JA, Lopez C, Pellett PE. Identification of a nucleocapsid protein as a specific serological marker of human herpesvirus 6 infection. Journal of clinical microbiology. 1990;28:1957–1962. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.9.1957-1962.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pellett PE, Sanchez-Martinez D, Dominguez G, Black JB, Anton E, Greenamoyer C, Dambaugh TR. A strongly immunoreactive virion protein of human herpesvirus 6 variant B strain Z29: identification and characterization of the gene and mapping of a variant-specific monoclonal antibody reactive epitope. Virology. 1993;195:521–531. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Qian G, Wood C, Chandran B. Identification and characterization of glycoprotein gH of human herpesvirus-6. Virology. 1993;194:380–386. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Anderson RA, Gompels UA. N- and C-terminal external domains of human herpesvirus-6 glycoprotein H affect a fusion-associated conformation mediated by glycoprotein L binding the N terminus. J Gen Virol. 1999;80 ( Pt 6):1485–1494. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-80-6-1485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pfeiffer B, Berneman ZN, Neipel F, Chang CK, Tirwatnapong S, Chandran B. Identification and mapping of the gene encoding the glycoprotein complex gp82-gp105 of human herpesvirus 6 and mapping of the neutralizing epitope recognized by monoclonal antibodies. J Virol. 1993;67:4611–4620. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.8.4611-4620.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chang CK, Balachandran N. Identification, characterization, and sequence analysis of a cDNA encoding a phosphoprotein of human herpesvirus 6. J Virol. 1991;65:7085. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.12.7085-.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Caselli E, Boni M, Bracci A, Rotola A, Cermelli C, Castellazzi M, Di Luca D, Cassai E. Detection of antibodies directed against human herpesvirus 6 U94/REP in sera of patients affected by multiple sclerosis. Journal of clinical microbiology. 2002;40:4131–4137. doi: 10.1128/JCM.40.11.4131-4137.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Soldan SS, Berti R, Salem N, Secchiero P, Flamand L, Calabresi PA, Brennan MB, Maloni HW, McFarland HF, Lin HC, et al. Association of human herpes virus 6 (HHV-6) with multiple sclerosis: increased IgM response to HHV-6 early antigen and detection of serum HHV-6 DNA. Nature medicine. 1997;3:1394–1397. doi: 10.1038/nm1297-1394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tejada-Simon MV, Zang YC, Hong J, Rivera VM, Zhang JZ. Cross-reactivity with myelin basic protein and human herpesvirus-6 in multiple sclerosis. Annals of neurology. 2003;53:189–197. doi: 10.1002/ana.10425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Suga S, Yoshikawa T, Asano Y, Nakashima T, Yazaki T, Fukuda M, Kojima S, Matsuyama T, Ono Y, Oshima S. IgM neutralizing antibody responses to human herpesvirus-6 in patients with exanthem subitum or organ transplantation. Microbiology and immunology. 1992;36:495–506. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1992.tb02047.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Foa-Tomasi L, Boscaro A, di Gaeta S, Campadelli-Fiume G. Monoclonal antibodies to gp100 inhibit penetration of human herpesvirus 6 and polykaryocyte formation in susceptible cells. Journal of virology. 1991;65:4124–4129. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.8.4124-4129.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu DX, Gompels UA, Foa-Tomasi L, Campadelli-Fiume G. Human herpesvirus-6 glycoprotein H and L homologs are components of the gp100 complex and the gH external domain is the target for neutralizing monoclonal antibodies. Virology. 1993;197:12–22. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Takeda K, Haque M, Sunagawa T, Okuno T, Isegawa Y, Yamanishi K. Identification of a variant B-specific neutralizing epitope on glycoprotein H of human herpesvirus-6. The Journal of general virology. 1997;78 ( Pt 9):2171–2178. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-78-9-2171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kawabata A, Oyaizu H, Maeki T, Tang H, Yamanishi K, Mori Y. Analysis of a neutralizing antibody for human herpesvirus 6B reveals a role for glycoprotein Q1 in viral entry. Journal of virology. 2011;85:12962–12971. doi: 10.1128/JVI.05622-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Foa-Tomasi L, Guerrini S, Huang T, Campadelli-Fiume G. Characterization of human herpesvirus-6(U1102) and (GS) gp112 and identification of the Z29-specified homolog. Virology. 1992;191:511–516. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(92)90222-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **39.Gerdemann U, Keukens L, Keirnan JM, Katari UL, Nguyen CT, de Pagter AP, Ramos CA, Kennedy-Nasser A, Gottschalk SM, Heslop HE, et al. Immunotherapeutic strategies to prevent and treat human herpesvirus 6 reactivation after allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Blood. 2013;121:207–218. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-05-430413. Report of additional CD8+ T cell epitope restricted by HLA-B*40 HHV-6 T cell epitopes, ex vivo expansion of HHV-6 specific cytotoxic CD8+ T cells and suggestions that these could be used in immunotherapy. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **40.Martin LK, Schub A, Dillinger S, Moosmann A. Specific CD8(+) T cells recognize human herpesvirus 6B. European journal of immunology. 2012;42:2901–2912. doi: 10.1002/eji.201242439. Report of the first antigen-specific CD8+ T cell epitope from HHV-6, and observation of a low frequency of HHV-6 antigen-specific CD8+ T cells recognizing these epitopes in healthy adults. Development of HLA-A2 tetramers for study of HLA-A2 T cell responses to HHV-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sylwester AW, Mitchell BL, Edgar JB, Taormina C, Pelte C, Ruchti F, Sleath PR, Grabstein KH, Hosken NA, Kern F, et al. Broadly targeted human cytomegalovirus-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cells dominate the memory compartments of exposed subjects. J Exp Med. 2005;202:673–685. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.de Pagter AP, Boelens JJ, Scherrenburg J, Vroom-de Blank T, Tesselaar K, Nanlohy N, Sanders EA, Schuurman R, van Baarle D. First analysis of human herpesvirus 6T-cell responses: specific boosting after HHV6 reactivation in stem cell transplantation recipients. Clinical immunology. 2012;144:179–189. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2012.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yakushijin Y, Yasukawa M, Kobayashi Y. T-cell immune response to human herpesvirus-6 in healthy adults. Microbiol Immunol. 1991;35:655–660. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1991.tb01597.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tejada-Simon MV, Zang YC, Hong J, Rivera VM, Killian JM, Zhang JZ. Detection of viral DNA and immune responses to the human herpesvirus 6 101-kilodalton virion protein in patients with multiple sclerosis and in controls. Journal of virology. 2002;76:6147–6154. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.12.6147-6154.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Haveman LM, Scherrenburg J, Maarschalk-Ellerbroek LJ, Hoek PD, Schuurman R, de Jager W, Ellerbroek PM, Prakken BJ, van Baarle D, van Montfrans JM. T-cell response to viral antigens in adults and children with common variable immunodeficiency and specific antibody deficiency. Clinical and experimental immunology. 2010;161:108–117. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2010.04159.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yakushijin Y, Yasukawa M, Kobayashi Y. Establishment and functional characterization of human herpesvirus 6-specific CD4+ human T-cell clones. J Virol. 1992;66:2773–2779. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.5.2773-2779.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *47.Wang F, Yao K, Yin QZ, Zhou F, Ding CL, Peng GY, Xu J, Chen Y, Feng DJ, Ma CL, et al. Human herpesvirus-6-specific interleukin 10-producing CD4+ T cells suppress the CD4+ T-cell response in infected individuals. Microbiol Immunol. 2006;50:787–803. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2006.tb03855.x. Report showing that in vitro expanded HHV-6-specific T cells secrete high levels of IL-10, which inhibits CD4 and CD8 T cell responses. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **48.Yoshikawa T, Kato Y, Ihira M, Nishimura N, Ozaki T, Kumagai T, Asano Y. Kinetics of cytokine and chemokine responses in patients with primary human herpesvirus 6 infection. Journal of clinical virology: the official publication of the Pan American Society for Clinical Virology. 2011;50:65–68. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2010.09.017. Unique analysis of the cytokine and chemokine response to HHV-6 in childeren suffering from roseola. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Flamand L, Gosselin J, Stefanescu I, Ablashi D, Menezes J. Immunosuppressive effect of human herpesvirus 6 on T-cell functions: suppression of interleukin-2 synthesis and cell proliferation. Blood. 1995;85:1263–1271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Horvat RT, Parmely MJ, Chandran B. Human herpesvirus 6 inhibits the proliferative responses of human peripheral blood mononuclear cells. J Infect Dis. 1993;167:1274–1280. doi: 10.1093/infdis/167.6.1274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lusso P. HHV-6 and the immune system: mechanisms of immunomodulation and viral escape. Journal of clinical virology: the official publication of the Pan American Society for Clinical Virology. 2006;37 (Suppl 1):S4–10. doi: 10.1016/S1386-6532(06)70004-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Furukawa M, Yasukawa M, Yakushijin Y, Fujita S. Distinct effects of human herpesvirus 6 and human herpesvirus 7 on surface molecule expression and function of CD4+ T cells. J Immunol. 1994;152:5768–5775. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Glosson NL, Hudson AW. Human herpesvirus-6A and -6B encode viral immunoevasins that downregulate class I MHC molecules. Virology. 2007;365:125–135. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2007.03.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *54.Wang F, Chi J, Peng G, Zhou F, Wang J, Li L, Feng D, Xie F, Gu B, Qin J, et al. Development of virus-specific CD4+ and CD8+ regulatory T cells induced by human herpesvirus 6 infection. Journal of virology. 2014;88:1011–1024. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02586-13. First report of classical regulatory T cells recognizing HHV-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Iampietro M, Morissette G, Gravel A, Dubuc I, Rousseau M, Hasan A, O’Reilly RJ, Flamand L. Human herpesvirus 6B immediate early I protein contains functional HLA-A*02, A*03 and B*07 class I-restricted CD8 T cell epitopes. European journal of immunology. 2014 doi: 10.1002/eji.201444931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wang FZ, Dahl H, Ljungman P, Linde A. Lymphoproliferative responses to human herpesvirus-6 variant A and variant B in healthy adults. Journal of medical virology. 1999;57:134–139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cirone M, Cuomo L, Zompetta C, Ruggieri S, Frati L, Faggioni A, Ragona G. Human herpesvirus 6 and multiple sclerosis: a study of T cell cross-reactivity to viral and myelin basic protein antigens. Journal of medical virology. 2002;68:268–272. doi: 10.1002/jmv.10190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Uemura Y, Senju S, Maenaka K, Iwai LK, Fujii S, Tabata H, Tsukamoto H, Hirata S, Chen YZ, Nishimura Y. Systematic analysis of the combinatorial nature of epitopes recognized by TCR leads to identification of mimicry epitopes for glutamic acid decarboxylase 65-specific TCRs. Journal of immunology. 2003;170:947–960. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.2.947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Razonable RR, Zerr DM. HHV-6, HHV-7 and HHV-8 in solid organ transplant recipients. American journal of transplantation: official journal of the American Society of Transplantation and the American Society of Transplant Surgeons. 2009;9 (Suppl 4):S100–103. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2009.02899_2.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ablashi DV, Devin CL, Yoshikawa T, Lautenschlager I, Luppi M, Kuhl U, Komaroff AL. Review Part 3: Human herpesvirus-6 in multiple non-neurological diseases. Journal of medical virology. 2010;82:1903–1910. doi: 10.1002/jmv.21860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *61.Ogata M, Satou T, Kadota J, Saito N, Yoshida T, Okumura H, Ueki T, Nagafuji K, Kako S, Uoshima N, et al. Human herpesvirus 6 (HHV-6) reactivation and HHV-6 encephalitis after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation: a multicenter, prospective study. Clinical infectious diseases: an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2013;57:671–681. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *62.Scheurer ME, Pritchett JC, Amirian ES, Zemke NR, Lusso P, Ljungman P. HHV-6 encephalitis in umbilical cord blood transplantation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Bone marrow transplantation. 2013;48:574–580. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2012.180. These two papers show that encephalitis is a major complication in HSCT transplantation. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **63.Zerr DM, Fann JR, Breiger D, Boeckh M, Adler AL, Xie H, Delaney C, Huang ML, Corey L, Leisenring WM. HHV-6 reactivation and its effect on delirium and cognitive functioning in hematopoietic cell transplantation recipients. Blood. 2011;117:5243–5249. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-10-316083. This prospective study of CNS dysfunction in hematopoietic stem cell transplantation patients shows an association between HHV-6 reaction and neurocognitive decline in the first 3 months following the transplant. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Singh N, Bentlejewski C, Carrigan DR, Gayowski T, Knox KK, Zeevi A. Persistent lack of human herpesvirus-6 specific T-helper cell response in liver transplant recipients. Transplant infectious disease: an official journal of the Transplantation Society. 2002;4:59–63. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3062.2002.t01-1-02001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.de Pagter PJ, Boelens JJ, Jacobi R, Schuurman R, Nanlohy NM, Sanders EA, van Baarle D. Increased proportion of perforin-expressing CD8+T-cells indicates control of herpesvirus reactivation in children after stem cell transplantation. Clinical immunology. 2013;148:92–98. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2013.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *66.Gerdemann U, Keirnan JM, Katari UL, Yanagisawa R, Christin AS, Huye LE, Perna SK, Ennamuri S, Gottschalk S, Brenner MK, et al. Rapidly generated multivirus-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes for the prophylaxis and treatment of viral infections. Molecular therapy: the journal of the American Society of Gene Therapy. 2012;20:1622–1632. doi: 10.1038/mt.2012.130. Protocol for the generation of multivirus-specific CTL, to 7 viruses including HHV-6, CMV, EBV, adenovirus, BK, RSV and flu is presented and is the basis for the clinical trial reported by Papadopoulou 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **67.Papadopoulou A, Gerdemann U, Katari UL, Tzannou I, Liu H, Martinez C, Leung K, Carrum G, Gee AP, Vera JF, et al. Activity of broad-spectrum T cells as treatment for AdV, EBV, CMV, BKV, and HHV6 infections after HSCT. Science translational medicine. 2014;6:242ra283. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3008825. First report of HHV-6 immunotherapy in HSCT patients in a small clinical trial. Virus load was controlled by transfer of in vitro expanded T cells. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Cheng W, Ma Y, Gong F, Hu C, Qian L, Huang Q, Yu Q, Zhang J, Chen S, Liu Z, et al. Cross-reactivity of autoreactive T cells with MBP and viral antigens in patients with MS. Frontiers in bioscience. 2012;17:1648–1658. doi: 10.2741/4010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]