Abstract

Escherichia coli heat-labile enterotoxin has unique immunogenic and adjuvant properties when administered mucosally to mice. These properties have revealed the potential for its use in the development of mucosal vaccines, an area of increasing interest. However, the inherent toxicity mediated by the A subunit precludes its widespread use. This problem has led to attempts to dissociate toxicity from adjuvant function by use of the B subunit. The ability of the B subunit of E. coli heat-labile enterotoxin (EtxB) to enhance responses against antigens coadministered intranasally is demonstrated here with the use of the DO11.10 adoptive-transfer model, in which ovalbumin (OVA)-specific adoptively transferred T cells can be monitored directly by flow cytometry. Intranasal delivery of OVA with EtxB resulted in increased T-cell proliferative and systemic antibody responses against antigens. The increased Th2 cytokine production detected following in vitro restimulation of splenocyte and cervical lymph node (CLN) cells from the immunized mice correlated with increased OVA-specific immunoglobulin G1 antibody production. Flow cytometric analysis of T cells from mice early after immunization directly revealed the ability of EtxB to support antigen-specific clonal expansion and differentiation. Furthermore, while responses were first detected in the CLNs, they rapidly progressed to the spleen, where they were further sustained. Examination of CD69 expression on dividing cells supported the notion that activation induced by the presence of antigens is not sufficient to drive T-cell differentiation. Furthermore, a lack of CD25 expression on dividing cells suggested that EtxB-mediated T-cell clonal expansion may occur without a sustained requirement for interleukin 2.

The majority of soluble proteins are poorly immunogenic following mucosal delivery. Instead, soluble protein delivery by the oral or intranasal route usually triggers specific tolerance. This fact necessitates the identification of suitable adjuvants for mucosal vaccines. Both Escherichia coli heat-labile enterotoxin (Etx) and its relative, cholera toxin (Ctx), act as potent mucosal adjuvants potentiating local immunity and systemic immunity to admixed antigens (7, 12). Etx and Ctx consist of a single A subunit and five identical polypeptides that together form the B subunit. In the resulting hexamers, the A subunit is associated with a doughnut-shaped ring formed by the B subunit. The B-subunit pentamer is an extremely stable noncovalently associated protein complex (43). While the A subunit has ADP ribosyltransferase activity and is responsible for toxicity, the B subunits are nontoxic oligomers. Their primary function lies in binding receptors, particularly GM1 ganglioside, thus facilitating internalization of the A subunit into cells.

Extensive investigations into the adjuvant properties of Etx and Ctx have been carried out. For a long time, their use in humans was considered unacceptable due to their likely toxicity. More recently, Etx was used as an intranasal adjuvant for an influenza vaccine in humans. Although the precise role played by Etx cannot be accurately determined, a significant elevation in the numbers of recipients suffering from Bell's palsy was reported. Taken together with observations from animals which indicated that Ctx causes inflammation in the olfactory bulb, this observation effectively halted the use of the holotoxins as intranasal adjuvants (8, 32). Attempts to take advantage of their adjuvant properties while avoiding toxicity therefore have focused either on the use of recombinant B subunits alone (30, 39) or on the use of mutants of the holotoxins with reduced or absent ADP ribosyltransferase activity (reviewed in references 37 and 55). Although initial data derived by these approaches were discouraging (25), more recent studies supported the potency of both mutant molecules (10, 11, 20, 56) and the B subunit of Etx (EtxB) (30, 39) in enhancing responses to coadministered antigens.

Importantly, there are differences in the natures of the responses induced by these different toxin-derived adjuvants. For example, the response induced by Ctx holotoxins appeared to be more Th2 dominated than the response induced when Etx was used as an adjuvant. However, recombinant EtxB triggered a highly Th2-dominated response, and the B subunit of Ctx appeared to be a very poor adjuvant when used alone (reviewed in reference 41). EtxB augmented both systemic and mucosal antibody responses following intranasal delivery with either herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) glycoproteins (39) or hen egg lysozyme (HEL) (30). In vitro restimulation of lymph node cells from mice immunized with EtxB as an adjuvant resulted in increased proliferation and cytokine production (39). Further, intranasal immunization with EtxB as an adjuvant was extremely effective at reducing the incidence and severity of ocular infection with HSV-1. Interestingly, the B subunit of Ctx failed to augment T-cell or antibody responses to either HSV-1 glycoproteins or HEL at a wide range of doses (30, 39). Importantly, repeated intranasal administrations of EtxB to mice did not lead to any inflammation in the olfactory bulb (N. A. Williams et al., unpublished data).

Although the ability of EtxB to potentiate responses against coadministered antigens has been clearly demonstrated, the processes by which it alters the immune response are unclear. Receptor binding by the B subunit plays a critical role in its activity, as demonstrated by the failure of a non-receptor-binding mutant of EtxB, EtxB(G33D) (33), to potentiate a response to HEL (30). It is therefore widely assumed that receptor interactions with mucosal epithelial cells trigger translocation into the underlying lymphoid tissues, where the modulation of leukocytes affects the activation and differentiation of antigen-responsive T cells. Determination of the events involved requires the use of a model in which the early processes of specific T-cell activation can be monitored in vivo.

An adoptive-transfer system in which ovalbumin (OVA)-specific T cells from T-cell receptor-transgenic DO11.10 mice (31) are injected into normal BALB/c mice (21) has been used widely to monitor the fate of antigen-specific T cells in vivo. Studies with this system have investigated the processes associated with both the generation of an active immune response and the induction of tolerance (28, 34, 45, 49). This model has the advantage of allowing the identification of antigen-specific cells in an animal in which normal homeostatic controls are present and in which there is a diverse repertoire of potential antigen specificities within both the T-cell and the B-cell compartments. We have therefore used this system to monitor T-cell activation, differentiation, and clonal expansion following intranasal administration of OVA in the presence or absence of EtxB as a mucosal adjuvant. We clearly demonstrate that EtxB possesses the ability to drive enhanced T-cell division and differentiation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Experimental animals.

Female BALB/c mice (Harlan Olac, Bicester, United Kingdom) and T-cell receptor-transgenic DO11.10 mice (bred at University of Bristol animal facilities) were housed under barrier-maintained conditions. Animals were cared for in accordance with institutional guidelines for animal welfare under the regulation of the Home Office for the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland.

Reagents.

Recombinant preparations of EtxB and EtxB(G33D) were purified and depleted of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) as reported previously (50). The LPS content was routinely <30 endotoxin units/mg of protein. OVA (grade IV; Sigma) was reconstituted in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and dialyzed extensively prior to use. The protein concentration was determined after dialysis by using a bicinchoninic acid protein assay kit (Pierce).

Adoptive transfer and immunization.

A total of 6 × 106 T lymphocytes (>85% CD3+) isolated from the spleen and mesenteric lymph nodes of DO11.10 mice by using nylon wool (Du Pont Biotechnology, Boston, Mass.) were transferred intravenously into unirradiated syngeneic BALB/c mice. For some experiments, enriched T cells were labeled with carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester (CFSE; Molecular Probes) prior to adoptive transfer. On day 1 following adoptive transfer, recipient mice were immunized intranasally with 100 μg of OVA with or without 20 μg of EtxB or EtxB(G33D), with B subunits, or with PBS alone. Immunizations were repeated either on days 8 and 15 or on day 8 alone.

In vitro proliferation and cytokine assays.

Cells derived from the spleen and cervical lymph nodes (CLNs) (pooled superficial and internal jugular lymph nodes) of the immunized mice were prepared as described previously (16). Contaminating erythrocytes were removed from splenocyte suspensions by incubating the cells with ACK lysing buffer (BioWhittaker Inc.). Cells were cultured in 25-cm2 flasks with the alpha modification of Eagle's medium (Gibco-BRL) supplemented with 20 mM HEPES buffer, 100 μg of streptomycin sulfate/ml, 100 U of benzylpenicillin/ml, 4 mM l-glutamine, and 50 μM 2-mercaptoethanol (Sigma). Prior to culturing, 0.5% autologous mouse serum was added to cell suspensions, which were incubated in a humidified atmosphere of 5% carbon dioxide and 95% air at 37°C in the absence or presence of OVA at 200 μg/ml. At selected time points, triplicate 100-μl samples from the cultures were transferred to 96-well round-bottom plates and pulsed with 18.5 kBq of [3H]thymidine ([3H]TdR)/well for 6 h. Cells were harvested, [3H]TdR incorporation was measured by standard scintillation, and results were presented as mean and standard error of the mean (SEM) counts per minute.

The production of gamma interferon (IFN-γ), interleukin-4 (IL-4), or IL-10 was detected by a previously described method (1). Briefly, samples from cell cultures were incubated overnight at 37°C on enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) plates that had been coated with the appropriate anti-mouse cytokine antibodies (PharMingen, Biosource Inc.). Cytokines produced during this period were detected with biotinylated anticytokine antibodies (PharMingen) and a streptavidin-peroxidase conjugate (Sigma). Cytokine production was estimated by linear regression analysis of log10-transformed absorbance data from serial dilutions of recombinant cytokines by using Microplate Manager 4.0 (Bio-Rad Laboratories Inc.) software.

Measurement of OVA-specific antibody responses.

Animals were bled through the tail or by cardiac puncture at approximately 15 days following a third intranasal immunization, and the serum was used for the detection of OVA-specific immunoglobulin. OVA-coated plates were washed and blocked with 1% bovine serum albumin-PBS before serial dilutions of serum were added; the plates then were incubated for 2 h at 37°C. Subsequently, a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated immunoglobulin G1 (IgG1) or IgG2a antibody (Serotec) was added to the wells. The plates were developed with o-phenylenediamine dihydrochloride substrate (Sigma), and the optical densities of the plate wells were measured at 490 nm. Amounts of anti-OVA immunoglobulin were estimated from endpoint titers calculated by linear regression analysis of log10-transformed data by using Statistics, version W1.58 (Blackwell Scientific Publications Ltd., Oxford, United Kingdom).

Flow cytometric analysis.

Spleen or lymph node cells were stained with the following antibodies: anti-CD45RB (16A; PharMingen), anti-CD25 (PC61; PharMingen), anti-CD69 (H1.2F3; PharMingen), and anti-CD4 (CT-CD4; Caltag Laboratories). The anticlonotypic antibody KJ1-26, used for the detection of OVA-specific adoptively transferred T cells (17), was kindly provided by F. Powrie (University of Oxford). For the detection of biotinylated antibody KJ1-26, samples were incubated either with ExtrAvidin-fluorescein isothiocyanate or ExtrAvidin-phycoerythrin (Sigma) or with streptavidin-allophycocyanin (Caltag) as necessary. Staining was performed with Hanks balanced salt solution containing 0.02% sodium azide (Sigma) and 5% normal rat serum (Sigma). Samples were analyzed by using a FACScan (three-color analysis) or a FACSCalibur (four-color analysis) flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson). All analyses were performed with appropriate control samples, including isotype- and conjugate-matched controls. At least 2,000 gated CD4+ KJ1-26-positive (KJ1-26+) events were collected for each sample. Collected data files were analyzed by using WinMDI 2.8 (J. Trotter, Scripps Research Institute).

Quantitative assessment of T-cell clonal expansion from CFSE profiles.

Differences observed in CFSE profiles were quantitated by using a previously described mathematical model (14, 54). This model is based on the principle that the size of the antigen-specific daughter T-cell subset and the size of the precursor subset are related by the function 2n, where n is the number of division cycles achieved during clonal expansion. The events under each CFSE fluorescence peak represent a proportion of the antigen-specific T-cell population that has undergone n division cycles. If A is the total number of clonally expanded T cells at the peak of the response, then the percentages of cells under each fluorescence peak can be used to calculate the absolute number of T cells under each peak (En) as a percentage of A. The absolute number of precursors that gave rise to that number of cells then can be calculated by dividing the absolute number of T cells by 2n, where n is the number of divisions corresponding to that peak. The sum of the precursors for each division cycle (Ps) can be calculated from equation 1:

|

(1) |

This equation gives the size of the precursor sample pool that generated the cell sample with the given division pattern. Similarly, the size of the precursor sample pool that responded by dividing (Psr) can be determined by summing the absolute numbers of precursors from 1 to n division cycles with equation 2:

|

(2) |

The parameters of clonal expansion that can be calculated with the use of the above data are the responder frequency (R) (equation 3) and the proliferative capacity (Cp) (equation 4), representing the proportion of the precursor sample pool that responded to antigenic stimulation by dividing and the number of cells generated by an average responder cell, respectively:

|

(3) |

|

(4) |

As both the responder frequency and the proliferative capacity are independent of the net yield of antigen-specific clonally expanded T cells measured at the peak of the response and described as A for reasons of simplicity, calculations did not include the arithmetic values for A, although these values were measured during the experiments.

Statistical analysis.

Descriptive statistics were calculated and normality testing was carried out by using Graphpad Prism 3.02 (Graphpad Software Co.). For comparisons of multiple groups of parametric data, one-way analysis of variance was used. When a P value from analysis of variance was <0.05, the Newman-Keuls posttest for multiple comparisons was used to determine statistical significance for each treatment group in comparison to the others. For all statistical analyses, a P value of <0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Ability of EtxB to act as an adjuvant for OVA in DO11.10 BALB/c chimeric mice.

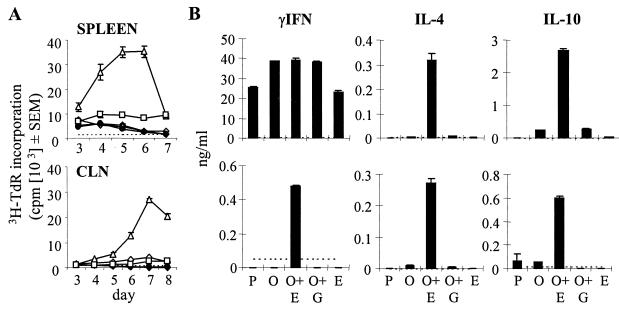

Initial experiments were performed to confirm that EtxB acts as an adjuvant for OVA in DO11.10 chimeric BALB/c mice. At 24 h after adoptive transfer, CD4+ KJ1-26+ cells represented approximately 1% of the CD4+ T cells in the spleen and lymph nodes (mesenteric, cervical, and inguinal) of recipient mice (data not shown). Recipients were given three intranasal immunizations at 1-week intervals with either EtxB, OVA, or PBS alone or with OVA in the presence of EtxB or EtxB(G33D). At 15 days after the final immunization, T-cell proliferative and cytokine responses in cultures of both splenic and CLN cells were monitored. While proliferative responses above background levels were detected in cultures from all mouse groups (Fig. 1A), a strong reaction indicative of a recall response was observed only in the group that had received OVA with EtxB. The addition of EtxB to OVA also markedly enhanced cytokine responses. While splenic cultures from all groups did produce some cytokines above background levels (most notably IFN-γ), high levels of IL-4 and IL-10 in addition to IFN-γ were seen only in cultures from mice immunized with OVA plus EtxB (Fig. 1B). Similarly, IL-4 and IL-10 were detected at high levels in cultures of CLN cells from mice treated with OVA plus EtxB but not other mice. IFN-γ was detectable only in CLN cultures from mice treated with OVA plus EtxB, but at levels much lower than those in splenocyte cultures from the same mice. The overall levels of proliferation and cytokine production were lower in cultures of CLN cells than in those of spleen cells. Similar results were obtained in four separate experiments.

FIG. 1.

(A) Intranasal exposure to OVA in the presence of EtxB enhances proliferation following stimulation with OVA in vitro. Isolated T cells from DO11.10 mice were adoptively transferred into normal BALB/c mice (day 0). At days 1, 8, and 15, the recipients were immunized intranasally with OVA (⋄), OVA plus EtxB (▵), or OVA plus EtxB(G33D) (□) (day 1). Control mice were given PBS (♦) or EtxB (•). At 15 days after the third immunization, splenocytes and CLN cells were derived and cultured in vitro with OVA. At the indicated days after the initiation of the cultures, triplicate samples were derived for the assessment of proliferation by [3H]TdR incorporation. The data are expressed as means and SEMs for triplicate samples. Maximal proliferation in cultures established in the absence of OVA is indicated by a broken horizontal line. (B) In vitro cytokine production in OVA-stimulated cultures from mice immunized intranasally with OVA in the presence of EtxB. Abbreviations: P, PBS; O, OVA; O+E, OVA plus EtxB; O+G, OVA plus EtxB(G33D); and E, EtxB. Cytokine production was measured by an ELISA at the peak days of the response, day 5 for the spleen and day 7 for the CLNs. The data are expressed as means and SEMs for triplicate samples. Maximal levels of the respective cytokines detected in cultures established in the absence of OVA are indicated by a broken horizontal line.

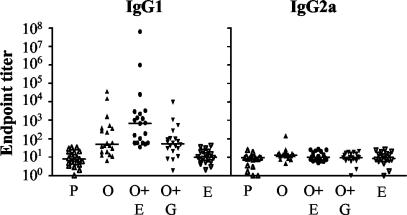

A comparison of OVA-specific IgG1 and IgG2a levels in serum samples taken from the different immunization groups revealed very low levels of these antibodies in mice that were not immunized with OVA (Fig. 2). Intranasal administration of OVA even in the absence of EtxB or in the presence of EtxB(G33D) significantly increased the levels of IgG1 (the P value was <0.05 for a comparison with the PBS- or EtxB-treated group) but not IgG2a. However, the addition of EtxB to OVA caused a much stronger IgG1 response, which was significantly greater than that in any other group [the P value was <0.05 for a comparison with the group treated with OVA, and the P value was <0.01 for a comparison with the group treated with OVA plus EtxB(G33D)]. The levels of OVA-specific IgG2a antibodies were not increased following any of the described intranasal immunization protocols. The endpoint titers for both IgG isotypes in mice that were given EtxB without OVA remained similar to those in the PBS-treated control mice. These results are for 20 mice per immunization group in four separate experiments.

FIG. 2.

Intranasal exposure to OVA in the presence of EtxB enhances OVA-specific systemic antibody production. Mice were bled at 15 days after the third immunization, and the levels of OVA-specific antibodies were quantified by an isotype-specific ELISA. See the legend to Fig. 1 for details. The data represent individual titers of OVA-specific IgG1 and IgG2a antibodies in the serum obtained from each mouse. The data from 20 mice in each group (5 mice in each of 4 identical experiments) were combined. The median titer in each group is indicated by a horizontal bar.

Flow cytometric analysis of cell surface markers following intranasal immunization with OVA and EtxB as an adjuvant.

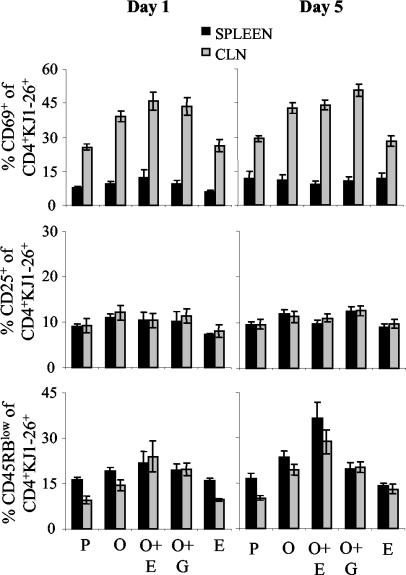

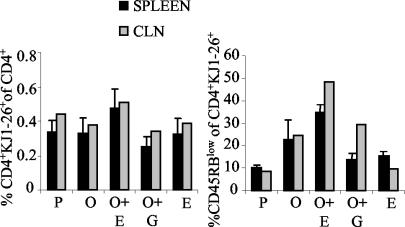

Having established that EtxB acts as a potent mucosal adjuvant in DO11.10 chimeric mice, we conducted experiments to investigate its effects on T-cell activation and differentiation. For this purpose, DO11.10 chimeric mice were immunized as described above on days 1 and 8. The phenotypes of the adoptively transferred cells in the spleen and mesenteric, cervical, and inguinal lymph nodes were assessed 1 and 5 days after the second immunization by flow cytometry. For this purpose, CD4+ KJ1-26+ cells were gated, and the expression of CD69, CD25, and CD45RB was monitored. Data from three separate experiments with three mice per group were analyzed similarly and pooled (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

CD69, CD45RB, and CD25 expression in OVA-specific CD4+ KJ1-26+ T cells following stimulation in vivo with OVA and EtxB as an adjuvant. Following adoptive transfer of DO11.10 T cells (day 0), mice were immunized intranasally on days 1 and 8 with OVA alone (O), OVA plus EtxB (O+E), or OVA plus EtxB(G33D) (O+G). Control mice were given PBS (P) or EtxB (E). CD69, CD45RB, and CD25 expression by CD4+ KJ1-26+ T cells from the spleen and CLNs of individual mice at 1 and 5 days after the second immunization was calculated as the percentage of CD69+, CD45RBlow, or CD25+ cells among the CD4+ KJ1-26+ population determined in density plots. The data in the graphs represent the means and SEMs for nine individual mice (three separate experiments each with three mice per group).

CD69 is an acute activation marker (46). When mice were given PBS alone, a smaller number of CD4+ KJ1-26+ cells expressed CD69 in the spleen (8%) than in the CLNs (25%). The administration of OVA either in the presence or in the absence of EtxB or EtxB(G33D) led to marked increases in the proportions of CD4+ KJ1-26+cells that expressed CD69 in the CLNs on days 1 and 5 (the P values were <0.05 [day 1] and <0.001 [day 5] for each group compared to the PBS-treated group). EtxB administered alone did not increase the number of cells expressing CD69 above that in mice given PBS (P > 0.05). Furthermore, coadministration of EtxB with OVA did not result in any further increase over that observed with OVA alone, and the differences among the three OVA-treated groups were not significant (P > 0.05). Similar changes were not seen in the spleen, where the low proportions of CD4+ KJ1-26+ cells expressing CD69 remained consistent between groups on days 1 and 5.

CD25 is the IL-2 receptor α chain and is expressed on activated T cells and certain regulatory T-cell populations (40). Small percentages of CD4+ KJ1-26+ T cells expressing CD25 were detected in PBS-treated mice (Fig. 3). These percentages were similar in both the spleen and the CLNs and were not altered in any of the treatment groups on days 1 and 5.

Levels of CD45RB decrease as T cells differentiate following activation (50). The percentage of cells with a low level of CD45RB expression in the CD4+ KJ1-26+ population was determined. On day 1, the percentage of CD45RBlow CD4+ KJ1-26+cells was increased in the CLNs of mice that had received OVA (Fig. 3). The greatest increase was observed in mice treated with OVA plus EtxB (the P value was <0.05 for a comparison with PBS- or EtxB-treated mice, and the P value was >0.05 for comparisons with other groups of mice). Similar changes observed in the spleen on day 1 were not statistically significant. On day 5, however, mice given OVA plus EtxB had significantly higher percentages of CD45RBlow cells in both the spleen and the CLNs than mice given OVA alone or OVA plus EtxB(G33D) [for the spleen and CLNs, respectively, the P values were <0.05 and <0.05 for a comparison with OVA and <0.001 and <0.05 for a comparison with OVA plus EtxB(G33D)]. The percentage of CD45RBlow cells in mice given OVA in the absence of EtxB was also higher than that in PBS-treated mice, although this difference was not significant. It should be noted that no changes were observed in the phenotypes of the CD4+ KJ1-26− T cells in these experiments, and analysis of cells isolated from the inguinal and mesenteric lymph nodes failed to reveal any consistent differences (data not shown).

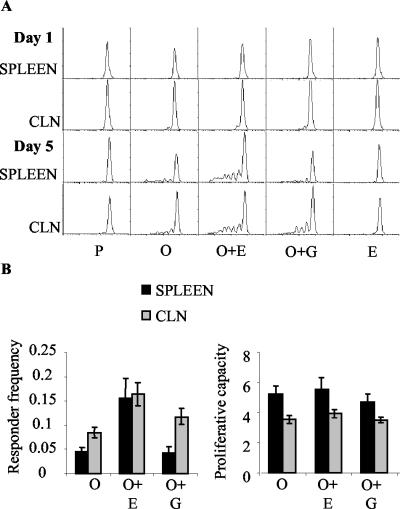

EtxB increases the responder frequency in the CLNs and spleen of OVA-immunized mice.

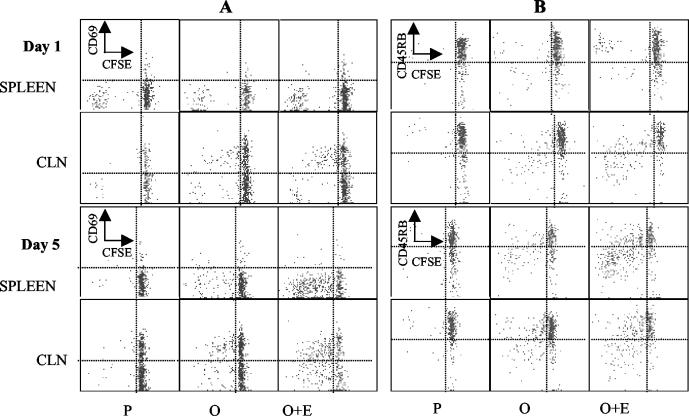

In order to determine whether the presence of EtxB altered clonal expansion in response to OVA, the vital dye CFSE was used (26). CFSE segregates equally between daughter cells upon division and can therefore be used to monitor cell proliferation in vivo. T cells from DO11.10 mice were labeled with CFSE prior to intravenous transfer into normal BALB/c mice, which were then immunized as described above. At 1 and 5 days after the second immunization, spleen and CLN cells were isolated and examined by flow cytometry. No divisions occurred in the groups that received PBS or EtxB alone (Fig. 4A). In the remaining three groups [receiving OVA, OVA plus EtxB, and OVA plus EtxB(G33D)], divisions were observed in the CLNs but not in the spleen on day 1, and divisions were observed in both tissues on day 5. For the CLNs, a very small number of cells were in the first cycles of division on day 1 in all three mouse groups that received OVA. The administration of EtxB with OVA did not appear to enhance cell divisions in the CLNs at that time point. On day 5, cell divisions in the CLNs had clearly progressed compared to those on day 1, and larger numbers of cells could be detected at initial and later rounds of division. In contrast to the results observed on day 1, the administration of EtxB with OVA appeared to have increased cell divisions in the CLNs on day 5. The results were similar for the spleen at that time point (day 5) (Fig. 4A). While divisions in the spleen were evident in all three groups, increased numbers of cells at later stages of division were observed in mice immunized with OVA plus EtxB. In all three groups, divisions in the spleen had progressed to later rounds than had those in the CLNs. EtxB appeared to enhance not only the numbers of divisions observed in the spleen and CLNs but also the percentages of cells dividing in response to OVA.

FIG. 4.

(A) Cell division in the OVA-specific CD4+-T-cell subset following stimulation in vivo with nominal antigen. CFSE-labeled DO11.10 T cells were adoptively transferred into normal BALB/c mice. The recipients were immunized as described in the legend to Fig. 3. At 1 and 5 days after the second immunization, cell division by gated CD4+ KJ1-26+ cells was assessed by the serial halving of CFSE fluorescence. (B) Responder frequency and proliferative capacity of adoptively transferred cells in mice immunized with OVA and EtxB as an adjuvant. The values for responder frequency and proliferative capacity were derived from the CFSE profiles of mice immunized with OVA alone or with OVA and EtxB or EtxB(G33D) at 5 days after the second immunization. Data from six individual mice in each group in two separate experiments are presented as means and SEMs.

The CFSE profiles from two separate experiments each including three mice per group were used to calculate the responder frequency and the proliferative capacity of the CD4+ KJ1-26+ population (Fig. 4B). The results from the analysis of the responder frequency showed that higher proportions of transferred cells divided in the spleen and CLNs from mice treated with OVA plus EtxB than in those from mice in the other two groups. The largest increase in responder frequency resulting from the presence of EtxB was seen in the spleen, where the response was lower than that seen in the CLNs for the other two groups. Accordingly, the difference in the responder frequency was significant only in the spleen (P < 0.01) and not in the CLNs. Examination of the proliferative capacity for the same samples showed that there were no differences between the numbers of daughter cells generated per precursor among the three groups for each tissue. The proliferative capacity in the spleen was higher than that in the CLNs for all groups.

Expression of cell surface molecules on dividing cells.

Costaining experiments were carried out to investigate the association between the altered phenotype of the CD4+ KJ1-26+ population and cell division as revealed by the levels of CFSE. When CD69 expression was examined simultaneously with CFSE fluorescence, the results showed that the upregulation of CD69 preceded entry into cell division in the CLNs (Fig. 5A). As cell divisions continued, CD69 expression was progressively reduced. This result was more evident for mice immunized with OVA plus EtxB due to a larger number of divisions. In contrast to those in the CLNs, divisions in the spleen were not accompanied by the expression of CD69 on the cell surface. Very few splenic CD4+ KJ1-26+ cells expressed CD69, and those that did were undivided cells that were seen in similar numbers in PBS-treated mice and OVA-treated mice. CD25 expression was not associated with the phenotype of dividing cells either in the spleen or in the CLNs. Small numbers of CD25+ CD4+ KJ1-26+ cells were detected in all mouse groups, and the majority of dividing cells did not express CD25 (data not shown).

FIG. 5.

(A) Association of cell division and CD69 expression in the OVA-specific CD4+-T-cell subset following stimulation in vivo with nominal antigen. Recipients of CFSE-labeled DO11.10 T cells were immunized as described in the legend to Fig. 3. The expression of CD69 and the division of CFSE fluorescence were estimated simultaneously for gated CD4+ KJ1-16+ T cells at the indicated time points and for the indicated tissues. (B) Association of cell division and CD45RB expression in the OVA-specific CD4+-T-cell subset following stimulation in vivo with nominal antigen. A vertical line is set at the base of the undivided peak, and a horizontal line separates the cells with increased CD69 expression or decreased CD45RB expression as those falling above or below, respectively.

Analysis of CD45RB expression showed that divisions in both the spleen and the CLNs were accompanied by a sequential reduction in CD45RB expression, while CD45RB levels remained high in groups in which no divisions were observed (PBS [Fig. 5] and EtxB [data not shown]). The simultaneous reductions in CFSE fluorescence and CD45RB expression during division were particularly evident in mice that were given OVA plus EtxB; in these mice, the numbers of divisions were increased and more cells exhibited a differentiated phenotype (CD45RBlow).

Correlation between increased T-cell proliferation in vitro and CD45RB expression.

The observed increased ability of cells from mice treated with OVA plus EtxB to proliferate in vitro in response to OVA could have been the result of clonal expansion leading to an increased precursor frequency in the tissues of these mice and/or enhanced differentiation of the cells allowing a more vigorous response. In order to investigate these possibilities, staining for CD45RB expression among CD4+ KJ1-26+ T cells was performed at the same time point at which the tissues were used for in vitro stimulation with OVA. When the overall percentages of CD4+ KJ1-26+ cells among the CD4 population were compared, a larger number of CD4+ KJ1-26+ cells was observed in mice immunized with OVA plus EtxB for both the spleen and the CLNs (Fig. 6). However, as there were no considerable differences between the groups, it is unlikely that this finding alone could have accounted for the increased proliferation in cultures from mice treated with OVA plus EtxB. Analysis of CD45RB expression on CD4+ KJ1-26+ T cells revealed that immunization with OVA in the presence of EtxB led to pronounced increases in the proportions of differentiated cells in both the spleen and the CLNs of immunized mice (Fig. 6). Although mice immunized with OVA alone or OVA in the presence of EtxB(G33D) exhibited some degree of differentiation in comparison to control mice (treated with PBS and EtxB), the coadministration of EtxB with OVA resulted in a 1.5-fold increase in the percentage of differentiated cells in the spleen and a 2-fold increase in that percentage in the CLNs.

FIG. 6.

Persistence and state of differentiation of CD4+ KJ1-26+ cells following an extended immunization protocol. Adoptive transfer, immunization, and flow cytometric staining were carried out as described in the legends to Fig. 1 and 3. At 15 days after the third immunization, the percentage of CD4+ KJ1-26+ cells among the CD4+ T cells and the percentage of CD45RBlow cells among the CD4+ KJ1-26+ cells in density plots were determined. Means and SEM for five mice are presented for the spleen; for the CLNs, the values were derived from mixed samples from five mice.

DISCUSSION

The ability of EtxB to enhance the immune response to intranasally coadministered antigens was demonstrated here with the use of the DO11.10 adoptive-transfer model. The addition of EtxB to OVA significantly increased both specific antibody production and T-cell proliferative and cytokine responses against OVA. The induction of high levels of anti-OVA IgG1 antibodies in the absence of detectable IgG2a indicates a Th2-dominated response when EtxB is used as an adjuvant. This finding was reflected by the stimulation of IL-4 and IL-10 production by splenic and CLN cells and is consistent with data obtained with the use of EtxB as an adjuvant for HSV-1 glycoproteins (39). As with HSV-1 antigen, the Th2-dominated antibody response occurred despite the presence of lymph node IFN-γ production, an observation indicating that the balance between Th1 and Th2 cytokines, rather than their presence or absence, determines the nature of the antibody response. Interestingly, the levels of IFN-γ produced in spleen cell cultures were relatively high in all groups, with similarly enhanced levels being observed in all animals that had received OVA. It is likely that these findings reflect the capacity of naive T cells to produce IFN-γ in primary responses that would occur in all of these cultures and that exposure to OVA in vivo led to partial priming of the spleen cell population for IFN-γ production regardless of the presence of EtxB. Importantly, the adjuvant activity of EtxB was entirely dependent on receptor binding, as the non-receptor-binding mutant EtxB(G33D) (33) failed to enhance both antibody and T-cell-mediated responses against OVA.

Flow cytometric analysis of OVA-specific T cells in the DO11.10 adoptive-transfer system revealed that EtxB was able to markedly alter T-cell activation, differentiation, and clonal expansion in response to intranasally administered antigen. In contrast to studies of other adjuvants and immunization routes in the same model, however, there were no significant increases in the overall numbers of KJ1-26+ cells in either the spleen or local lymph nodes (data not shown). Marked increases in OVA-specific cell numbers have been reported following intravenous administration of OVA peptide, subcutaneous injection of OVA, and oral feeding of OVA (34, 35, 45). In these reports, the presence of the antigen was adequate to induce significant clonal expansion, which was further increased when an adjuvant, such as LPS (22, 35, 36), complete Freund adjuvant (36), or Ctx (45), was added. The lack of such a difference in our system may reflect the route of administration, the timing of our observations (which followed a second antigen dose) or, more likely, the much lower dose of antigen used. The dose of OVA used by us induced a functionally significant response in the presence of EtxB, as displayed by the antibody and proliferation data, and was in keeping with the quantities of antigen used in other studies with this adjuvant (30, 39). Therefore, the observations that we made are physiologically relevant to the induction of the types of responses that we sought to study.

Phenotypic analysis of antigen-specific T cells in the spleen and CLNs following OVA administration showed that cell activation was associated with some upregulation of CD69 expression but no increase in the proportion of OVA-specific cells expressing CD25. Costaining in studies with CFSE confirmed that dividing KJ1-26+ cells did not express CD25. IL-2 usually drives the proliferative phase of the T-cell response (44) and, as divisions progress, the requirement for IL-2 diminishes and cells downregulate CD25 (48). Although our observations were unexpected, data describing T-cell proliferation in IL-2-deficient mice with LPS as an adjuvant (22) correlate with our findings. Indeed, IL-2 not only acts as a T-cell growth factor but also is a key factor in priming cells for activation-induced cell death (23, 51), a process that prevents the excessive accumulation of activated T cells (24). Accordingly, IL-2-deficient mice show evidence of dysregulated immune responses and autoimmunity (23). Avoidance of this pathway by the failure of T cells, activated as a result of the coadministration of EtxB, to upregulate CD25 may promote more persistent responses.

As expected, cell divisions were detectable in the CLNs but not in the spleen 1 day after antigen administration. T cells initiating divisions in the CLNs had upregulated CD69 expression irrespective of the administration of EtxB. This finding is consistent with reports that transient activation occurs not only prior to the induction of an active response but also during the induction of tolerance (18, 21, 34, 45, 49). Despite the administration of OVA, either alone or in the presence of EtxB(G33D), at a level sufficient to stimulate CD69 upregulation, receptor binding by EtxB was required to stimulate optimal differentiation and division. Thus, the downregulation of CD45RB was much more marked in animals given OVA with EtxB, and the proportion of cells with reduced levels of CFSE was much higher in this group. On day 5, large numbers of cells were also dividing in the spleen of mice given OVA with EtxB, although these cells were not expressing CD69. Indeed, CD69 expression was not observed on nondividing or dividing KJ1-26+ spleen cells in any of the groups.

Quantitation of CFSE profiles revealed that EtxB increased the responder frequency rather than the proliferative capacity of OVA-specific T cells in the spleen and the CLNs. The increased responder frequency was more evident in the spleen, where very few divided cells were detected in mice that did not receive OVA with EtxB. Interestingly, the addition of EtxB gave rise to essentially the same precursor frequencies in both the spleen and the CLNs. Moreover, the proliferative capacity was consistently lower in the CLNs than in the spleen for each group that received OVA. While this finding may indicate that cells entering the cell cycle in the spleen are more likely to go through multiple divisions than those in the CLNs, it should be noted that the analysis does not take into account cell migration. Thus, the data may also indicate that cells migrate to the spleen following activation and initial cell divisions in the CLNs. The latter possibility is also suggested by the lack of dividing spleen cells on day 1 and the absence of upregulated CD69 expression in this tissue.

The rapid regulation of CD69 expression means that its presence probably indicates the presentation of antigen locally. Therefore, our results suggest that the dose of OVA we used does not result in significant quantities entering the circulation, from which splenic antigen-presenting cells (APC) are most likely to acquire antigen. This suggestion is in contrast to the findings of previous reports with either orally (2, 15) or intranasally (29) administered antigens. However, the extent to which antigen enters the circulation following mucosal delivery is likely to be highly dependent on the dose delivered and the model used. The absence of CD69 expression in the spleen strongly suggests that local presentation of OVA is not the primary mechanism initiating cell divisions in the spleen. Further, the data suggest that CD69 expression is lost from activated cells as they migrate to the spleen from peripheral lymph nodes. The alternative—that migrating CLN cells belong to a distinct CD69− subset—is unlikely.

The presence of the more divided and differentiated antigen-specific T cells in the spleen is also consistent with our observations of the in vitro responses of these cells. The proliferative response in spleen cell cultures was stronger and reached an earlier peak than that in CLN cell cultures. Further, the differentiation of T cells into Th2 cells, as was observed with the use of EtxB as an adjuvant, has been associated with a loss of the ability to enter peripheral lymph nodes in favor of preferential homing to the spleen (19). This effect is probably due to the distinct expression of chemokine receptors (3, 42).

Interestingly, the intravenous administration of antigen has been reported to induce a high frequency of antigen-specific CD4 cells in both the lymph nodes and the spleen, followed by a decline in the numbers of antigen-specific T cells in the lymph nodes but not in the spleen (4). The trafficking and retention of memory CD4+ T cells in the spleen were proposed as mechanisms ensuring optimal protective responses against blood-borne antigens through the generation of memory B cells in the spleen (27). The precise location of the activated T cells in the spleens of mice given intranasal OVA with EtxB remains to be established, as does their role in promoting the observed systemic IgG1 antibody response. However, with our system, it is also likely that some component of the activated T-cell population reenters the mucosal tissues associated with the nasal cavity in order to support the local production of secretory antibodies that are seen there (30, 39, 52). Studies of nasal lymphoid tissue will be necessary to confirm this notion, and an investigation of chemokine receptor expression by differentiating KJ1-26+ cells would be interesting.

How does EtxB promote T-cell differentiation and division? Mechanisms associated with adjuvant function include the production of inflammatory cytokines (9, 35), the stimulation of APC to express costimulatory molecules (21, 24), and the control of dendritic cell migration (6, 17, 38, 45). EtxB has multiple activities on cells of the immune system as well as on mucosal epithelial cells. These include the ability to trigger polyclonal upregulation of the class II major histocompatibility complex and CD86 on B cells and to modulate APC cytokine production. In addition, Ctx has been shown to be capable of contributing directly to T-cell activation through negating the requirement for costimulation, a property thought to be related to its capacity to promote raft formation on the cell membrane (53). The quantities of free EtxB entering the lymph nodes following intranasal delivery are likely to be very low; therefore, the key effects of EtxB are probably associated with the modulation of APC. The capacity to activate B cells may enhance their stimulatory ability; however, microanatomic considerations probably preclude even activated B cells from coming into contact with significant numbers of naive T cells. If the modulation of B-cell antigen presentation is involved, then it is most likely involved in promoting the expansion of activated T cells and possibly in shaping their differentiation into Th2 cells. It is conceivable that this effect alone is sufficient to allow transiently activated T cells, which are initially stimulated in a manner identical to that which occurs after mucosal antigen delivery alone, to undergo productive differentiation rather than to become abortively activated, a process that may occur as part of tolerance. Alternatively, EtxB may also modify the activity of dendritic cells. While this possibility has yet to be tested, whole Ctx is known to modulate dendritic cell function, favoring Th2 differentiation (13), and EtxB can trigger TNF-α and IL-10 production by monocytes while at the same time inhibiting IL-12 secretion (5). Such a profile would be consistent with activating T cells but failing to promote Th1 differentiation. Elucidation of the precise effects of EtxB on APC populations in vivo will be necessary to determine which receptor-mediated activities are key to its capacity to promote T-cell activation, differentiation, and cell division. Such an understanding will allow the rational use of EtxB as a potentially nontoxic adjuvant for the development of important mucosal vaccines.

Acknowledgments

We thank T. R. Hirst and Martin Kenny for providing EtxB and EtxB(G33D) used in these studies.

N.A.W. is a Wellcome Trust Research leave fellow.

Editor: A. D. O'Brien

REFERENCES

- 1.Beech, J. T., T. Bainbridge, and S. J. Thompson. 1997. Incorporation of cells into an ELISA system enhances antigen-driven lymphokine detection. J. Immunol. Methods 205:163-168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benson, J. M., K. A. Campbell, Z. Guan, I. E. Gienapp, S. S. Stuckman, T. Forsthuber, and C. C. Whitacre. 2000. T-cell activation and receptor downmodulation precede deletion induced by mucosally administered antigen. J. Clin. Investig. 106:1031-1038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bonecchi, R., G. Bianchi, P. P. Bordignon, D. D'Ambrosio, R. Lang, A. Borsatti, S. Sozzani, P. Allavena, P. A. Gray, A. Mantovani, and F. Sinigaglia. 1998. Differential expression of chemokine receptors and chemotactic responsiveness of type 1 T helper cells (Th1s) and Th2s. J. Exp. Med. 187:129-134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bradley, L. M., J. Harbertson, and S. R. Watson. 1999. Memory CD4 cells do not migrate into peripheral lymph nodes in the absence of antigen. Eur. J. Immunol. 29:3273-3284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Braun, M. C., J. He, C.-Y. Wu, and B. L. Kelsall. 1999. Cholera toxin suppresses interleukin (IL)-12 production and IL-12 receptor β1 and β2 chain expression. J. Exp. Med. 189:541-552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cella, M., M. Salio, Y. Sakakibara, H. Langen, I. Julkunen, and A. Lanzavecchia. 1999. Maturation, activation, and protection of dendritic cells induced by double-stranded RNA. J. Exp. Med. 189:821-829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clements, J. D., N. M. Hartzog, and F. L. Lyon. 1988. Adjuvant activity of Escherichia coli heat-labile enterotoxin and effect on the induction of oral tolerance in mice to unrelated protein antigens. Vaccine 6:269-277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Couch, R. B. 2004. Nasal vaccination, Escherichia coli enterotoxin, and Bell's palsy. N. Engl. J. Med. 350:860-861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Curtsinger, J. M., C. S. Schmidt, A. Mondino, D. C. Lins, R. M. Kedl, M. K. Jenkins, and M. F. Mescher. 1999. Inflammatory cytokines provide a third signal for activation of naive CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. J. Immunol. 162:3256-3262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Di Tommaso, A., G. Saletti, M. Pizza, R. Rappuoli, G. Dougan, S. Abrignani, G. Douce, and M. T. De Magistris. 1996. Induction of antigen-specific antibodies in vaginal secretions by using a nontoxic mutant of heat-labile enterotoxin as a mucosal adjuvant. Infect. Immun. 64:974-979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Douce, G., C. Turcotte, I. Cropley, M. Roberts, M. Pizza, M. Domenghini, R. Rappuoli, and G. Dougan. 1995. Mutants of Escherichia coli heat-labile toxin lacking ADP-ribosyltransferase activity act as nontoxic, mucosal adjuvants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:1644-1648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Elson, C. O., and W. Ealding. 1984. Cholera toxin feeding did not induce oral tolerance in mice and abrogated oral tolerance to an unrelated protein antigen. J. Immunol. 133:2892-2897. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gagliardi, M. C., F. Sallusto, M. Marinaro, A. Langenkamp, A. Lanzavecchia, and M. T. De Magistris. 2000. Cholera toxin induces maturation of human dendritic cells and licences them for Th2 priming. Eur. J. Immunol. 30:2394-2403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gudmundsdottir, H., A. D. Wells, and L. A. Turka. 1999. Dynamics and requirements of T cell clonal expansion in vivo at the single-cell level: effector function is linked to proliferative capacity. J. Immunol. 162:5212-5223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gütgemann, I., A. M. Fahrer, J. D. Altman, M. M. Davis, and Y.-H. Chien. 1998. Induction of rapid T cell activation and tolerance by systemic presentation of an orally administered antigen. Immunity 6:667-673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harper, H. M., L. Cochrane, and N. A. Williams. 1996. The role of small intestinal antigen-presenting cells in the induction of T-cell reactivity to soluble protein antigens: association between aberrant presentation in the lamina propria and oral tolerance. Immunology 89:449-456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hartmann, G., G. J. Weiner, and A. M. Krieg. 1999. CpG DNA: a potent signal for growth, activation, and maturation of human dendritic cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:9305-9310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hoyne, G. F., B. A. Askonas, C. Hetzel, W. R. Thomas, and J. R. Lamb. 1996. Regulation of house dust mite responses by intranasally administered peptide: transient activation of CD4+ T cells precedes the development of tolerance in vivo. Int. Immunol. 8:335-342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Iezzi, G., D. Scheidegger, and A. Lanzavecchia. 2001. Migration and function of antigen-primed nonpolarized T lymphocytes in vivo. J. Exp. Med. 193:987-993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jakobsen, H., D. Schulz, M. Pizza, R. Rappuoli, and I. Jónsdóttir. 1999. Intranasal immunization with pneumococcal polysaccharide conjugate vaccines with nontoxic mutants of Escherichia coli heat-labile enterotoxins as adjuvants protects mice against invasive pneumococcal infections. Infect. Immun. 67:5892-5897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kearney, E. R., K. A. Pape, D. Y. Loh, and M. K. Jenkins. 1994. Visualization of peptide-specific T cell immunity and peripheral tolerance induction in vivo. Immunity 4:327-339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Khoruts, A., A. Mondino, K. A. Pape, S. L. Reiner, and M. K. Jenkins. 1998. A natural immunological adjuvant enhances T cell clonal expansion through a CD28-dependent, interleukin (IL)-2-independent mechanism. J. Exp. Med. 187:225-236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kneitz, B., T. Herrmann, S. Yonehara, and A. Schimpl. 1995. Normal clonal expansion but impaired Fas-mediated cell death and anergy induction in interleukin-2-deficient mice. Eur. J. Immunol. 25:2572-2577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lenardo, M. J., S. Boehme, L. Chen, B. Combadiere, G. Fisher, M. Freedman, H. McFarland, C. Pelfrey, and L. Zheng. 1995. Autocrine feedback death and the regulation of mature T lymphocyte antigen responses. Int. Rev. Immunol. 13:115-134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lycke, N., T. Tsuji, and J. Holmgren. 1992. The adjuvant effect of Vibrio cholerae and Escherichia coli heat-labile enterotoxins is linked to their ADP-ribosyltransferase activity. Eur. J. Immunol. 22:2277-2281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lyons, A. B., and C. R. Parish. 1994. Determination of lymphocyte division by flow cytometry. J. Immunol. Methods 171:131-137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.MacLennan, I. C., A. Gulbranson-Judge, K. M. Toellner, M. Casamayor-Palleja, E. Chan, D. M. Sze, S. A. Luther, and H. A. Orbea. 1997. The changing preference of T and B cells for partners as T-dependent antibody responses develop. Immunol. Rev. 156:53-66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Malvey, E.-N., M. K. Jenkins, and D. L. Mueller. 1998. Peripheral immune tolerance blocks clonal expansion but fails to prevent the differentiation of Th1 cells. J. Immunol. 161:2168-2177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Metzler, B., C. Burkhart, and D. C. Wraith. 1999. Phenotypic analysis of CTLA-4 and CD28 expression during transient peptide-induced T cell activation in vivo. Int. Immunol. 11:667-675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Millar, D. G., T. R. Hirst, and D. P. Snider. 2001. Escherichia coli heat-labile enterotoxin B subunit is a more potent mucosal adjuvant than its closely related homologue, the B subunit of cholera toxin. Infect. Immun. 69:3476-3482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Murphy, K. M., A. B. Heimberger, and D. Y. Loh. 1990. Induction by antigen of intrathymic apoptosis of CD4+CD8+TCRlo thymocytes in vivo. Science 250:1720-1723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mutsch, M., W. Zhou, P. Rhodes, M. Bopp, R. T. Chen, T. Linder, C. Spyr, and R. Steffen. 2004. Use of the inactivated intranasal influenza vaccine and the risk of Bell's palsy in Switzerland. N. Engl. J. Med. 350:896-903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nashar, T. O., H. M. Webb, S. Eaglestone, N. A. Williams, and T. R. Hirst. 1996. Potent immunogenicity of the B subunits of Escherichia coli heat-labile enterotoxin: receptor binding is essential and induces differential modulation of lymphocyte subsets. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:226-230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pape, K. A., R. Merica, A. Mondino, A. Khoruts, and M. K. Jenkins. 1998. Direct evidence that functionally impaired CD4+ T cells persist in vivo following induction of peripheral tolerance. J. Immunol. 160:4719-4729. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pape, K. A., A. Khoruts, A. Mondino, and M. K. Jenkins. 1997. Inflammatory cytokines enhance the in vivo clonal expansion and differentiation of antigen-activated CD4+ T cells. J. Immunol. 159:591-598. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pape, K. A., E. R. Kearney, A. Khoruts, A. Mondino, R. Merica, Z.-M. Chen, E. Ingulli, J. White, J. G. Johnson, and M. K. Jenkins. 1997. Use of adoptive transfer of T-cell-antigen-receptor-transgenic T cells for the study of T-cell activation in vivo. Immunol. Rev. 156:67-78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pizza, M., M. M. Giuliani, M. R. Fontana, E. Monaci, G. Douce, G. Dougan, K. H. G. Mills, R. Rappuoli, and G. Del Giudice. 2001. Mucosal vaccines: nontoxic derivatives of LT and CT as mucosal adjuvants. Vaccine 19:2534-2541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Reis e Sousa, C., S. Hieny, T. Scharton-Kersten, D. Jankovic, H. Charest, R. N. Germain, and A. Sher. 1997. In vivo microbial stimulation induces rapid CD40 ligand-independent production of interleukin 12 by dendritic cells and their redistribution to T cell areas. J. Exp. Med. 186:1819-1829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Richards, C. M., A. T. Aman, T. R. Hirst, T. J. Hill, and N. A. Williams. 2001. Protective mucosal immunity to ocular herpes simplex virus type 1 infection in mice by using Escherichia coli heat-labile enterotoxin B subunit as an adjuvant. J. Virol. 75:1664-1671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sakaguchi, S., N. Sakaguchi, M. Asano, M. Itoh, and M. Toda. 1995. Immunologic self-tolerance maintained by activated T cells expressing IL-2 receptor alpha-chains (CD25). Breakdown of a single mechanism of self-tolerance causes various autoimmune diseases. J. Immunol. 155:1151-1164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Salmond, R. J., J. A. Luross, and N. A. Williams. 2002. Immune modulation by the cholera-like enterotoxins. Expert Rev. Mol. Med. 2002:1-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Siveke, J. T., and A. Hamann. 1998. T helper 1 and T helper 2 cells respond differentially to chemokines. J. Immunol. 160:550-554. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sixma, T. K., K. H. Kalk, B. A. M. van Zanten, Z. Dauter, J. Kingma, B. Witholt, and W. G. J. Hol. 1993. Refined structure of Escherichia coli heat-labile enterotoxin, a close relative of cholera toxin. J. Mol. Biol. 230:890-918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Smith, K. A. 1988. Interleukin-2: inception, impact, and implications. Science 240:1169-1176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Smith, K. M., J. M. Davidson, and P. Garside. 2002. T cell activation occurs simultaneously in local and peripheral lymphoid tissue following oral administration of a range of doses of immunogenic or tolerogenic antigen although tolerized T cells display a defect in cell division. Immunology 106:144-158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Testi, R., D. D'Ambrosio, R. De Maria, and A. Santoni. 1994. The CD69 receptor: a multipurpose cell-surface trigger for hematopoietic cells. Immunol. Today 15:479-483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Thomas, M. L., and L. Lefrançois. 1988. Differential expression of the leucocyte-common antigen family. Immunol. Today 9:320-326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Thorstenson, K. M., and A. Khoruts. 2001. Generation of anergic and potentially immunoregulatory CD25+CD4 T cells in vivo after induction of peripheral tolerance with intravenous or oral antigen. J. Immunol. 167:188-195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tsitoura, D. C., R. H. DeKruyff, J. R. Lamb, and D. T. Umetsu. 1999. Intranasal exposure to protein antigen induces immunological tolerance mediated by functionally disabled CD4+ T cells. J. Immunol. 163:2592-2600. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Turcanu, V., T. R. Hirst, and N. A. Williams. 2002. Modulation of human monocytes by Escherichia coli heat-labile enterotoxin B-subunit; altered cytokine production and its functional consequences. Immunology 106:316-325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Van Parijs, L., A. Biuckians, A. Ibragimov, F. W. Alt, D. M. Willerford, and A. K. Abbas. 1997. Functional responses and apoptosis of CD25 (IL-2R alpha)-deficient T cells expressing a transgenic antigen receptor. J. Immunol. 158:3738-3745. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Verweij, W. R., L. de Haan, M. Holtrop, E. Agsteribbe, R. Brands, G. J. van Scharrenburg, and J. Wilschut. 1998. Mucosal immunoadjuvant activity of recombinant Escherichia coli heat-labile enterotoxin and its B subunit: induction of systemic IgG and secretory IgA responses in mice by intranasal immunization with influenza virus surface antigen. Vaccine 16:2069-2076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Viola, A., S. Schroeder, Y. Sakakibara, and A. Lanzavecchia. 1999. T lymphocyte costimulation mediated by reorganisation of membrane microdomains. Science 283:680-682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wells, A. D., H. Gudmundsdottir, and L. A. Turka. 1997. Following the fate of individual T cells throughout activation and clonal expansion. Signals from T cell receptor and CD28 differentially regulate the induction and duration of a proliferative response. J. Clin. Investig. 100:3173-3183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yamamoto, M., J. R. McGhee, Y. Hagiwara, S. Otake, and H. Kiyono. 2001. Genetically manipulated bacterial toxin as a new generation mucosal adjuvant. Scand. J. Immunol. 53:211-217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yamamoto, S., H. Kiyono, M. Yamamoto, K. Imaoka, M. Yamamoto, K. Fujihashi, F. W. Van Ginkel, M. Noda, Y. Takeda, and J. R. McGhee. 1997. A nontoxic mutant of cholera toxin elicits Th2-type responses for enhanced mucosal immunity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:5267-5272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]