Abstract

Epidemiologic evidence on the association of antioxidant intake and prostate cancer incidence is inconsistent. Total antioxidant intake and prostate cancer incidence has not previously been examined. Using the ferric reducing antioxidant potential (FRAP) assay, the total antioxidant content (TAC) of diet and supplements were assessed in relation to prostate cancer incidence. A prospective cohort of 47,896 men aged 40-75 years was followed from 1986 to 2008 for prostate cancer incidence (N=5,656), and they completed food frequency questionnaires (FFQ) every 4 years. A FRAP value was assigned to each item in the FFQ, and for each individual, TAC scores for diet, supplements and both (total) were calculated. Major contributors of TAC intake at baseline were: coffee (28%), fruit and vegetables (23%) and dietary supplements (23%). In multivariate analyses for dietary TAC a weak inverse association was observed; (highest versus lowest quintiles: 0.91 (0.83-1.00, p-trend=0.03) for total prostate cancer, 0.81 (0.64-1.01, p-trend=0.04) for advanced prostate cancer); this association was mainly due to coffee. No association of total TAC on prostate cancer incidence was observed. A positive association with lethal and advanced prostate cancer was observed in the highest quintile of supplemental TAC intake: 1.28 (0.98-1.65, p-trend<0.01) and 1.15 (0.92-1.43), p-trend=0.04). The weak association between dietary antioxidant intake and reduced prostate cancer incidence may be related to specific antioxidants in coffee, to non-antioxidant coffee compounds, or other effects of drinking coffee. The indication of increased risk for lethal and advanced prostate cancer with high TAC intake from supplements warrants further investigation.

Keywords: Prostate cancer, Antioxidants, Oxidative stress, Diet, Risk factors

Introduction

Among men in western countries prostate cancer is the most commonly diagnosed cancer and the second leading cause of cancer death [1]. The 60-fold variation in incidence across countries may partly reflect differences in screening and diagnosis, but also suggests that modifiable lifestyle-related risk factors may contribute [2, 3]. One area of interest in prostate cancer research has been the hypothesis that foods rich in antioxidants may protect against prostate cancer, but the evidence is mixed [3].

The latest review from the World Cancer Research Fund concluded that there is evidence that intake of foods containing lycopene and selenium are associated with a lower risk of prostate cancer. For legumes and foods containing vitamin E and vitamin E supplements there is suggestive evidence for a protective effect. Intervention trials with single antioxidant supplements have consistently shown no beneficial effects of beta-carotene supplementation on prostate cancer risk. The evidence for a beneficial effect of selenium supplements is conflicting, and limited evidence suggests a protective effect of vitamin E among smokers[2, 4].

If antioxidants have cancer protective properties, because of their ability to reduce oxidative stress, examining the total intake of antioxidants rather than single antioxidants in relation to prostate cancer incidence may provide a stronger estimate of the effect. There is evidence suggesting that multiple antioxidants work synergistically to reduce oxidative stress [4-6]. For example, it is known that vitamin C (ascorbic acid) may recycle tocopherol radicals to tocopherols [7], but it is suggested that the concept of antioxidant recycling and networking could have a much broader validity [5-7].

The term “antioxidants” refers to several families of compounds, but only a few antioxidants have been studies so far. Examples of dietary antioxidants studied to some extent include ascorbic acid, tocopherols, β-carotene, lycopene, resveratrol, curcumin, quercetin, catechins and caffeic acid. Most of the dietary antioxidants are phytochemicals that originate in plants. There are probably more that 10,000 different phytochemicals in a normal diet, and most of these are antioxidants (i.e. that are redox active)[2, 6, 8]. These various antioxidants each have their specific bioavailability (absorption, transport and accumulation in tissues and subcellular localizations) and redox reactivity.

Hence, it would therefore not be expected that all dietary antioxidants would inhibit all oxidative stress-related pathogenesis. Such an inhibition would only occur if the specific dietary antioxidant (or one of its metabolites) is absorbed, transported to and accumulate at the relevant subcellular physiological site. Furthermore, the specific dietary antioxidant must also have the ability of react efficiently with the reactive molecular species that are involved in that particular disease development.

In the present study, we have focused on the concept of total intake of all dietary antioxidants combined. Several methods to quantify the total antioxidant capacity (TAC) in different foods have been developed [9]. The ferric-reducing antioxidant potential assay (FRAP), which measures the reduction of Fe3+ (ferric ion) to Fe2+ (ferrous ion), has been used extensively to quantify total antioxidants in foods [8, 10]. We have recently measured TAC of more than 3,100 foods used worldwide [8]. Other studies have examined a combined score of antioxidants and prooxidants in relation to prostate cancer risk . Agalliu and coworkers used a combined score consisting of 8 antioxidants and 5 prooxidants. They found no association with prostate cancer risk in the Canadian Study of Diet, Lifestyle and Health cohort [11]. In the Netherlands Cohort study, a combined pro- and antioxidant score were created consisting of 5 antioxidants and prooxidants. Geybels and coworkers found no association between the score and advanced and total prostate cancer incidence [12].

No study to date has examined total antioxidant capacity in relation to prostate cancer. In the Health Professionals Follow-up Study, a large prospective cohort of men, we examined the association between TAC intake, measured by FRAP, and the risk of prostate cancer during 22 years of follow-up and with updated data on diet.

Materials and methods

The Health Professionals Follow-up Study (HPFS) is a large prospective cohort study of 51,529 US male health professionals who were aged 40 to 75 years at baseline in 1986. Information on lifestyle and health is collected with biennial questionnaires, and dietary habits are assessed every four years. Men who completed the baseline food frequency questionnaire (FFQ) in 1986 form the study population for this analysis (N=49911). We excluded men with implausible energy intake, or who left more than 70 food items blank on the baseline FFQ. Men reporting a diagnosis of cancer (except non-melanoma skin cancer) prior to enrollment were also excluded, leaving a total of 47,896 men who were followed prospectively for prostate cancer incidence to 2008. The Health Professionals Follow-up Study is approved by the Human Subjects Committee at the Harvard School of Public Health.

Assessment of TAC intake

Dietary data were collected with semi-quantitative food frequency questionnaires (FFQs) at baseline in 1986 and again in 1990, 1994, 1998,2002 and 2006. Men were asked their frequency of consumption of over 130 food items over the previous year, with nine mutually exclusive response categories ranging from almost never to ≥6 times/day. Dietary supplement use was also reported including information on supplement type, dose, frequency and duration of use. All FFQ items were assigned a FRAP value from analyses at the Institute of Nutrition Research, University of Oslo [8]. When an FFQ item did not have a specified FRAP value, the value was imputed based on knowledge of foods and beverages with similar antioxidant profiles. FRAP values were also assigned to dietary supplements from analyses at the University of Oslo. To calculate each participant's TAC intake, the frequency of consumption of each item was multiplied by its FRAP value and summed across all items. Three exposure variables for TAC score were created: 1) Total TAC with the antioxidant contribution from foods, beverages and supplements, 2) Dietary TAC with the antioxidant contribution of only food and beverages and 3) Supplemental TAC was calculated by subtracting the dietary TAC from the total TAC value, giving the TAC value for each individual derived from dietary supplement use. To best reflect long-term diet, we used the daily cumulative average TAC intake in mmol as our exposure measure; that is, 1986 TAC was used for 1986-1990 follow-up, the average of 1986 and 1990 TAC was used for 1990-1994 follow-up, the average of 1986, 1990, and 1994 TAC was used for 1994-1998 follow-up, and so on. This also reduces within-person measurement error in the FFQ [13].

Ascertainment and classification of prostate cancer cases

Initial reporting of prostate cancer comes from participants on the biannual questionnaires. We seek to confirm prostate cancer using medical records and pathology reports, and 90 percent of prostate cancers are confirmed. All cases (N=5,656), including the remaining 10%, based on self-reports or death certificates were included, because the reporting of prostate cancer among men with medical records is quite accurate (>98%). Men with prostate cancer are sent additional questionnaires to monitor clinical outcomes, such as disease progression and development of metastases. Deaths are recorded through reports from family members and the National Death Index. An endpoints committee, using all available data including medical history, records, registry information and death certificates, determined the underlying cause of death. The prostate cancer cases were classified as follows: All incident prostate cancer (excluding T1a cancers, which are discovered incidentally during treatment for benign prostatic hyperplasia). Advanced prostate cancer were defined as cancer with seminal vesicle infiltration (T3b), invasion of adjacent organs (T4) or metastasis to lymph node (N+), or distant metastases (M1) at the time of diagnosis and included also men who developed lymph node, distal metastases or death from prostate cancer during follow up. Lethal cases, a subset of advanced cases, were defined as those who died from the disease or had distant metastases during follow-up. Localized cases included T1 and T2 cancers with no evidence of regional or distant metastases at diagnosis or during follow up. Cases were also categorized according to grade at diagnosis: High grade (Gleason score 8-10), Gleason score 7, and low grade (Gleason score 2-6) based on pathology reports from prostatectomy specimens or biopsies.

Statistical analysis

Participants contributed person-time from date of return of baseline questionnaire in 1986 until prostate cancer diagnosis, death or the end of study period, January 31, 2008. Participants were divided into quintiles of intake for the three TAC exposures (TAC from diet only, TAC from diet and supplements and TAC from supplements only) To calculate the incidence rates for prostate cancer we divided the number of incident cases in each quintile of different TAC intakes by the number of person –years in that quintile. TAC intakes were energy-adjusted using the residual method and adjusted for age and calendar time [13]. We used Cox proportional hazards regression to adjust for potential confounding by other factors. Multivariable models were adjusted for race (African-American, European-American, Asian and other), height (quartiles), BMI at age 21 (categories), current BMI (categories), vigorous physical activity (quintiles), smoking (current, former quit>10 years ago, former quit<10 years ago and never), diabetes mellitus (Type 1 or 2, yes/no), family history of prostate cancer (yes/no), history of PSA testing in the previous questionnaire period (yes/no), and intakes of calcium (quintiles), alpha-linolenic acid (quintiles), alcohol (categories) and energy (continuous). All covariates except race, height and BMI at age 21 were updated in each questionnaire cycle. To test for a linear trend across quintiles of antioxidant intake, we modelled the TAC intake as a continuous variable, using the median intake for each quintile.

We also examined the associations of the major contributors to dietary TAC with prostate cancer. Smoking increases oxidative stress and smokers have lower levels of circulating antioxidants, possibly due to increased utilization[14]. We therefore performed a subgroup analysis in never smokers, as the effect of antioxidant intake may be more apparent in these men. Analyses were performed using SAS version 9.1 (SAS Institute, Inc: Cary, NC). All P values were two-sided, with a P-value less than 0.05 considered to be statistically significant.

Results

The 47,896 men in HPFS contributed 879,879 person-years during which 5,656 men reported a prostate cancer diagnosis through 2008. Of these, 929 as advanced prostate cancer, and of those 670 were classified as lethal prostate cancer. 3,606 were classified as localized prostate cancer. There were 571 high-grade cases, 1,566 cases with Gleason score 7, and 2,340 low-grade cases. Gleason grade was not available for all men early in the follow up period. Some men that were diagnosed near the end of follow-up will be misclassified as non-advanced cancer because they didn't have time for disease progression before end of follow-up.

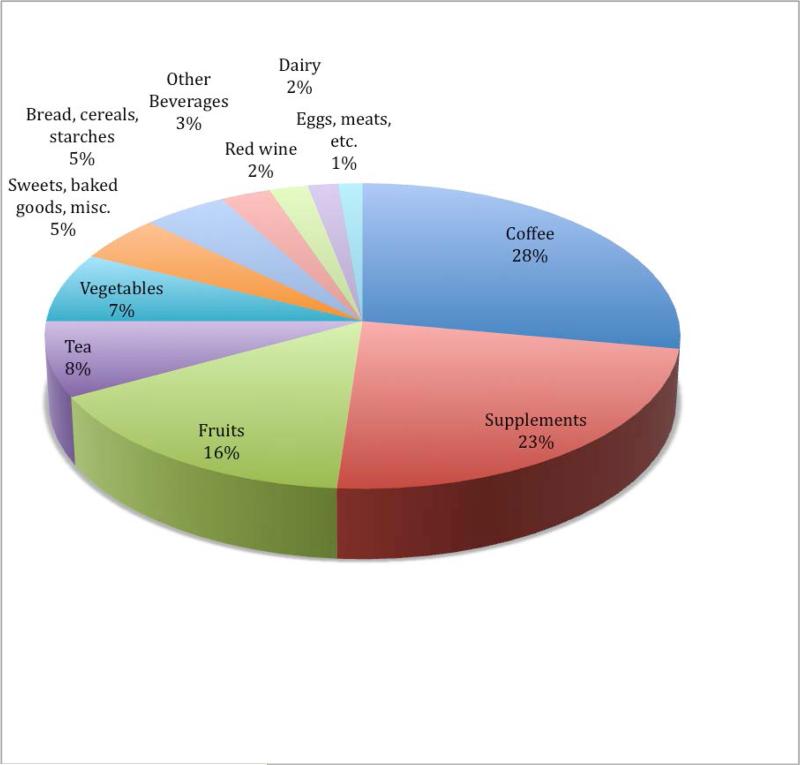

The cumulative average intake of energy-adjusted dietary TAC (from foods and beverages only) was 10.8 mmol/day and 3.4mmol/day for supplemental TAC (from supplements only). For total TAC the energy-adjusted intake was 14.1 mmol/day . The range of TAC for the whole cohort for dietary TAC was 1.8-41.9 mmol/day, for supplemental TAC: 0-68.5 mmol/day, and for total TAC: 1.9-76.7mmol/day. The cumulative average daily intake for dietary TAC compares well with results from other studies using TAC [15, 16]. The major contributors to TAC intake in the cohort in 1986 were: coffee (28%), dietary supplements (23%), fruits (16%), tea (8%) and vegetables (7%) (Figure 1). Vitamin C contributed three-quarters of the TAC from supplements. Among single foods and beverages the major contributors, in addition to coffee, were tea (8%), orange juice (5%), and red wine (2%). These four items together constituted almost half of TAC from foods and beverages in 1986. The change over time was very little among most items, but an increase in the amount of red wine contributing to TAC was seen over the years from 2 to 6 % from 1986- 2006. Over the same period of time, a decrease in the contribution from both coffee (28% to 20%) and tea (8% to 6%). Fruits & vegetables contribution was very stable over the period with 23 % in 1986 to 24% in 2006. The same was observed for dietary supplements (23% in 1986 to 22% in 2006).

Figure 1.

TAC (including supplements) by major contributors, food group and beverages according to 1986 Health Professionals Follow up Study food frequency questionnaire.

Dietary TAC showed inverse associations with total and advanced prostate cancer (multivariate-adjusted RR (MV-RR) for highest vs. lowest quintiles: 0.91(0.83-1.00), p- trend=0.03) and 0.80 (0.64-1.01, p- trend=0.04) (Table 2). With the other case definitions, there were no significant associations. There was no significant association between total TAC intake and total prostate cancer incidence, or for risk of disease based on stage or grade. We found a positive association with lethal and advanced prostate cancer in the highest quintile of supplemental TAC intake: 1.28 (0.98-1.65, p-trend<0.01) and 1.15 (0.92-1.43), p-trend=0.04) (Table 2). Vitamin C supplements and multivitamins are widely used in this cohort (30 % and 49 % respectively), and the TAC intake from dietary supplements is comprised mainly of vitamin C supplements and multivitamins.

Table 2.

Multivariable-adjusted hazard ratios (and 95% CIs) for prostate cancer according to energy-adjusted quintile of Dietary TAC, Supplementary TAC and Total TAC intake in the Health Professionals Follow up Study

| Dietary TAC | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | p trend |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All incident prostate cancer, N=5656 | 991 | 1187 | 1194 | 1203 | 1081 | |

| Multivariate RR | 1.00 | 0.97(0.89-1.06) | 0.92(0.85-1.01) | 0.93(0.85-1.01) | 0.91(0.83-1.00) | 0.03 |

| Lethal cases*, N=670 | 125 | 156 | 140 | 144 | 105 | |

| Multivariate RR | 1.00 | 1.06(0.83-1.35) | 0.94(0.73-1.22) | 1.05(0.81-1.35) | 0.87(0.66-1.14) | 0.30 |

| Advanced cases*, N=929 | 181 | 215 | 194 | 191 | 148 | |

| Multivariate RR | 1.00 | 1.00(0.81-1.22) | 0.89(0.72-1.10) | 0.92(0.74-1.14) | 0.80(0.64-1.01) | 0.04 |

| Localized prostate cancer**, N=3606 | 615 | 726 | 761 | 786 | 718 | |

| Multivariate RR | 1.00 | 0.93(0.83-1.04) | 0.90(0.81-1.01) | 0.91(0.82-1.02) | 0.91(0.81-1.02) | 0.16 |

| High grade cases***, N=571 | 93 | 123 | 128 | 116 | 111 | |

| Multivariate RR | 1.00 | 1.02(0.77-1.34) | 0.96(0.73-1.27) | 0.93(0.69-1.23) | 0.95(0.71-1.27) | 0.55 |

| Gleason score 7,N=1566 | 283 | 299 | 335 | 351 | 298 | |

| Multivariate RR | 1.00 | 0.85(0.72-1.01) | 0.88(0.75-1.04) | 0.90(0.76-1.06) | 0.83(0.70-0.99) | 0.12 |

| Low grade cases***, N=2340 | 408 | 490 | 468 | 500 | 474 | |

| Multivariate RR | 1.00 | 0.95(0.83-1.08) | 0.85(0.74-0.98) | 0.89(0.77-1.02) | 0.92(0.80-1.06) | 0.22 |

| Supplemental TAC | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All incident prostate cancer, N=5656 | 1001 | 1029 | 1170 | 1260 | 1196 | |

| Multivariate RR | 1.00 | 0.91(0.83-1.00) | 0.97(0.88-1.07) | 0.94(0.86-1.04) | 0.97(0.89-1.07) | 0.66 |

| Lethal cases*, N=670 | 127 | 114 | 136 | 137 | 156 | |

| Multivariate RR | 1.00 | 0.90(0.68-1.18) | 1.00(0.76-1.33) | 1.13(0.86-1.48) | 1.28(0.98-1.65) | <0.01 |

| Advanced cases*, N=929 | 180 | 158 | 192 | 196 | 203 | |

| Multivariate RR | 1.00 | 0.87(0.69-1.10) | 1.02(0.80-1.28) | 1.11(0.88-1.39) | 1.15(0.92-1.43) | 0.04 |

| Localized prostate cancer**, N=3606 | 616 | 654 | 740 | 835 | 761 | |

| Multivariate RR | 1.00 | 0.87(0.77-0.97) | 0.92(0.81-1.04) | 0.89(0.79-1.00) | 0.92(0.81-1.03) | 0.87 |

| High grade cases***, N=571 | 100 | 110 | 112 | 129 | 120 | |

| Multivariate RR | 1.00 | 0.91(0.68-1.22) | 0.83(0.61-1.13) | 0.88(0.66-1.19) | 0.95(0.71-1.27) | 0.72 |

| Gleason score 7,N=1566 | 272 | 294 | 311 | 357 | 332 | |

| Multivariate RR | 1.00 | 0.83(0.70-0.99) | 0.80(0.67-0.97) | 0.81(0.67-0.96) | 0.86(0.72-1.02) | 0.80 |

| Low grade cases***, N=2340 | 398 | 405 | 485 | 552 | 500 | |

| Multivariate RR | 1.00 | 0.91(0.78-1.05) | 1.05(0.90-1.22) | 1.04(0.90-1.20) | 1.03(0.89-1.18) | 0.43 |

| Total TAC | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | p trend |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All incident prostate cancer, N=5656 | 957 | 1178 | 1187 | 1164 | 1170 | |

| Multivariate RR | 1.00 | 1.01(0.93-1.11) | 0.98(0.89-1.07) | 0.96(0.88-1.05) | 0.98(0.89-1.07) | 0.40 |

| Lethal cases*, N=670 | 120 | 131 | 162 | 121 | 136 | |

| Multivariate RR | 1.00 | 0.98(0.76-1.27) | 1.31(1.02-1.67) | 1.02(0.78-1.33) | 1.18(0.91-1.53) | 0.22 |

| Advanced cases*, N=929 | 175 | 191 | 206 | 174 | 183 | |

| Multivariate RR | 1.00 | 0.96(0.78-1.19) | 1.09(0.88-1.34) | 0.97(0.78-1.20) | 1.05(0.84-1.30) | 0.67 |

| Localized prostate cancer**, N=3606 | 588 | 736 | 770 | 748 | 764 | |

| Multivariate RR | 1.00 | 1.00(0.90-1.12) | 0.97(0.86-1.08) | 0.94(0.84-1.05) | 0.96(0.86-1.08) | 0.37 |

| High grade cases***, N=571 | 89 | 129 | 112 | 124 | 117 | |

| Multivariate RR | 1.00 | 1.14(0.86-1.51) | 0.93(0.69-1.24) | 1.06(0.80-1.41) | 1.04(0.77-1.38) | 1.00 |

| Gleason score 7,N=1566 | 261 | 326 | 308 | 330 | 341 | |

| Multivariate RR | 1.00 | 1.01(0.85-1.19) | 0.87(0.73-1.03) | 0.93(0.78-1.10) | 0.97(0.82-1.15) | 0.72 |

| Low grade cases***, N=2340 | 391 | 453 | 525 | 466 | 505 | |

| Multivariate RR | 1.00 | 0.93(0.81-1.07) | 1.02(0.89-1.16) | 0.91(0.79-1.05) | 0.99(0.86-1.14) | 0.99 |

Multivariable RRs adjusted for: age in months, calendar time, race, height (quartiles), BMI at age 21(categories), BMI (categories), vigorous physical activity (quintiles), smoking status (current, former quit >10 years ago, former quit <10 years ago, never), diabetes, calcium intake (quintiles), alpha-linolenic acid(quintiles), alcohol intake (categories), energy intake (continuous), PSA testing in previous period (yes/no).

Lethal prostate cancer: Prostate cancer death or metastasis to bone. Advanced prostate cancer: Lethal, or Stage T3b, T4, N1 or M1 at diagnosis, or spread to lymph nodes or other metastases during follow-up.

Localized prostate cancer: T1 or T2 and N0/M0 at diagnosis with no spread to lymph nodes or other metastases or death during follow-up.

High grade cases: Gleason score 8-10. Low grade cases: Gleason score 2-6.

Since coffee is a large contributor to TAC intake and has previously been associated with lower risk of advanced and lethal prostate cancer in this cohort, we tested coffee along with the other contributors to dietary TAC in the multivariable models [17]. Including the major dietary contributors to TAC, we mutually adjusted for them in the analyses. As earlier published there was an inverse association with total prostate cancer incidence and coffee in this cohort. Now with longer follow up the results were more robust. (multivariate and mutually-adjusted RR (MV-RR) for individuals with highest intake vs. lowest intake: 0.77 (0.64-0.92, p- trend=0.01). The results were stronger for advanced cases: 0.46 (0.68-0.76), p- trend=0.01 and lethal cases: 0.41(0.22-0.76), p-trend=0.06. There were weak but significant inverse associations with total fruit and vegetable intakes and localized prostate cancer MV-RR: 0.82 (0.72-0.93, p-trend<0,01) and low grade prostate cancer MV-RR 0.83(0.71-0.97,p-trend=0.04) For the other main contributors to the dietary TAC, tea and red wine, the results were null with respect to the different prostate cancer outcomes (Table 3).

Table 3.

Multivariable hazard ratios (and 95% CIs) for prostate cancer according to intake of dietary contributors to TAC in the Health Professionals Follow up Study.

| Category or quintile of intake | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coffee (cups/day) | None | <1 | 1-3 | 4-5 | >5 | p-trend |

| All incident prostate cancer, N=5656 | 631 | 1336 | 2733 | 796 | 160 | |

| Multivariate RR | 1.00 | 0.93(0.84-1.03) | 0.92(0.84-1.01) | 0.89(0.80-1.00) | 0.77(0.64-0.92) | 0.01 |

| Lethal cases*, N=670 | 92 | 157 | 314 | 95 | 12 | |

| Multivariate RR | 1.00 | 0.75(0.57-0.98) | 0.73(0.56-0.94) | 0.79(0.58-1.08) | 0.41(0.22-0.76) | 0.06 |

| Advanced cases*, N=929 | 125 | 218 | 441 | 126 | 19 | |

| Multivariate RR | 1.00 | 0.79(0.62-0.99) | 0.76(0.61-0.95) | 0.75(0.57-0.98) | 0.46(0.28-0.76) | 0.01 |

| Localized prostate cancer**, N=3606 | 376 | 858 | 1740 | 526 | 106 | |

| Multivariate RR | 1.00 | 1.00(0.88-1.14) | 0.97(0.86-1.10) | 0.96(0.83-1.10) | 0.85(0.68-1.06) | 0.13 |

| High grade cases***, N=571 | 66 | 126 | 284 | 83 | 12 | |

| Multivariate RR | 1.00 | 0.74(0.54-1.02) | 0.80(0.60-1.07) | 0.79(0.56-1.11) | 0.50(0.27-0.95) | 0.22 |

| Gleason score 7, N=1566 | 182 | 357 | 727 | 254 | 46 | |

| Multivariate RR | 1.00 | 0.88(0.73-1.06) | 0.85(0.71-1.02) | 0.94(0.77-1.16) | 0.71(0.50-0.99) | 0.40 |

| Low grade cases***, N=2340 | 251 | 556 | 1139 | 324 | 70 | |

| Multivariate RR | 1.00 | 1.01(0.86-1.18) | 0.97(0.84-1.13) | 0.91(0.76-1.08) | 0.87(0.66-1.15) | 0.09 |

| Tea (cups/day) | None | <1 | 1 | 2 | >2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All incident prostate cancer, N=5656 | 1529 | 3339 | 130 | 413 | 245 | |

| Multivariate RR | 1.00 | 1.04(0.98-1.11) | 0.92(0.76-1.10) | 0.98(0.87-1.09) | 0.97(0.85-1.12) | 0.20 |

| Lethal cases*, N=670 | 211 | 356 | 33 | 31 | 39 | |

| Multivariate RR | 1.00 | 1.14(0.95-1.37) | 1.26(0.86-1.85) | 0.93(0.62-1.38) | 1.36(0.95-1.93) | 0.28 |

| Advanced cases*, N=929 | 290 | 509 | 35 | 46 | 49 | |

| Multivariate RR | 1.00 | 1.12(0.96-1.31) | 0.95(0.66-1.37) | 0.92(0.66-1.27) | 1.20(0.88-1.63) | 0.92 |

| Localized prostate cancer**, N=3606 | 924 | 2189 | 62 | 286 | 145 | |

| Multivariate RR | 1.00 | 1.02(0.94-1.11) | 0.84(0.65-1.09) | 0.97(0.84-1.11) | 0.91(0.76-1.09) | 0.12 |

| High grade cases***, N=571 | 143 | 359 | 11 | 36 | 22 | |

| Multivariate RR | 1.00 | 1.22(0.99-1.50) | 0.80(0.43-1.50) | 0.91(0.62-1.34) | 0.94(0.59-1.48) | 0.14 |

| Gleason score 7, N=1566 | 404 | 933 | 32 | 125 | 72 | |

| Multivariate RR | 1.00 | 1.01(0.89-1.14) | 0.93(0.65-1.35) | 0.98(0.79-1.21) | 1.01(0.78-1.31) | 0.86 |

| Low grade cases***, N=2340 | 626 | 1397 | 41 | 182 | 94 | |

| Multivariate RR | 1.00 | 1.01(0.91-1.12) | 0.78(0.57-1.07) | 0.97(0.82-1.15) | 0.89(0.72-1.11) | 0.17 |

| Red wine (glasses) | None | <1 glass/week | 1gl/w-0.5gl/d | >0.5 glass/day | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All incident prostate cancer, N=5656 | 2703 | 1683 | 945 | 325 | ||

| Multivariate RR | 1.00 | 0.98(0.91-1.05) | 1.02(0.93-1.12) | 1.05(0.92-1.20) | 0.27 | |

| Lethal cases*, N=670 | 406 | 157 | 79 | 28 | ||

| Multivariate RR | 1.00 | 1.14(0.91-1.41) | 1.19(0.90-1.57) | 1.29(0.85-1.96) | 0.19 | |

| Advanced cases*, N=929 | 537 | 236 | 120 | 36 | ||

| Multivariate RR | 1.00 | 1.08(0.90-1.29) | 1.12(0.89-1.41) | 1.06(0.73-1.52) | 0.66 | |

| Localized prostate cancer**, N=3606 | 1567 | 1135 | 653 | 251 | ||

| Multivariate RR | 1.00 | 0.93(0.85-1.02) | 0.95(0.85-1.06) | 1.04(0.89-1.21) | 0.37 | |

| High grade cases***, N=571 | 252 | 185 | 106 | 28 | ||

| Multivariate RR | 1.00 | 1.19(0.95-1.49) | 1.31(0.99-1.73) | 1.07(0.69-1.65) | 0.74 | |

| Gleason score 7, N=1566 | 701 | 480 | 285 | 100 | ||

| Multivariate RR | 1.00 | 0.92(0.80-1.05) | 0.95(0.80-1.12) | 0.99(0.78-1.26) | 0.82 | |

| Low grade cases***, N=2340 | 1032 | 733 | 417 | 158 | ||

| Multivariate RR | 1.00 | 0.97(0.87-1.09) | 0.98(0.86-1.13) | 1.03(0.85-1.25) | 0.63 |

| Total fruits and vegetables | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All incident prostate cancer, N=5656 | 902 | 1079 | 1142 | 1261 | 1272 | |

| Multivariate RR | 1.00 | 0.99(0.90-1.08) | 0.94(0.86-1.03) | 0.99(0.90-1.09) | 0.95(0.86-1.04) | 0.36 |

| Lethal cases*, N=670 | 96 | 123 | 131 | 140 | 180 | |

| Multivariate RR | 1.00 | 1.13(0.86-1.50) | 1.08(0.82-1.42) | 1.13(0.85-1.50) | 1.23(0.93-1.64) | 0.18 |

| Advanced cases*, N=929 | 142 | 181 | 183 | 190 | 233 | |

| Multivariate RR | 1.00 | 1.13(0.90-1.42) | 1.03(0.82-1.29) | 1.03(0.81-1.30) | 1.13(0.88-1.43) | 0.50 |

| Localized prostate cancer**, N=3606 | 585 | 701 | 727 | 830 | 763 | |

| Multivariate RR | 1.00 | 0.93(0.83-1.04) | 0.85(0.76-0.96) | 0.93(0.83-1.04) | 0.82(0.72-0.93) | <0.01 |

| High grade cases***, N=571 | 77 | 102 | 128 | 103 | 161 | |

| Multivariate RR | 1.00 | 1.11(0.82-1.50) | 1.20(0.89-1.62) | 0.90(0.66-1.24) | 1.32(0.96-1.80) | 0.11 |

| Gleason score 7, N=1566 | 248 | 303 | 318 | 361 | 336 | |

| Multivariate RR | 1.00 | 0.95(0.80-1.13) | 0.90(0.76-1.07) | 0.96(0.81-1.15) | 0.85(0.70-1.03) | 0.10 |

| Low grade cases***, N=2340 | 384 | 462 | 469 | 541 | 484 | |

| Multivariate RR | 1.00 | 0.96(0.83-1.10) | 0.87(0.75-1.00) | 0.96(0.83-1.10) | 0.83(0.71-0.97) | 0.04 |

Multivariable RRs adjusted for: age in months, calendar time, race, height (quartiles), BMI at age 21 (categories), BMI (categories), vigorous physical activity (quintiles),smoking status (current, former quit >10 years ago, former quit <10 years ago, never), diabetes, calcium intake (quintiles), alpha-linolenic acid(quintiles), alcohol intake (categories), energy intake (continuous), PSA testing in previous period (yes/no), additionally mutually adjusted for coffee intake (categories), tea intake (categories), red wine intake (categories), total fruit & vegetable intake (quintiles).

Lethal prostate cancer: Prostate cancer death or metastasis to bone. Advanced prostate cancer: Lethal, or Stage T3b, T4, N1 or M1 at diagnosis, or spread to lymph nodes or other metastases during follow-up.

Localized prostate cancer: T1 or T2 and N0/M0 at diagnosis with no spread to lymph nodes or other metastases or death during follow-up.

High grade cases: Gleason score 8-10. Low grade cases: Gleason score 2-6.

The results for dietary and total TAC intake among never smokers (N=21,358) were qualitatively similar to those for the whole cohort. For all incident prostate cancer (N=2,157) among never smokers, we observed an inverse association with dietary TAC MV-RR 0.81 (0.69-0.94, p-trend<0.01) for the highest vs. lowest quintile of intake. For lethal and advanced cases there were 36 % and 40 % risk reduction respectively in the highest quintile of dietary TAC compared to the lowest quintile, but the inverse associations were again stronger for coffee intake rather than for dietary TAC. [5-7]

Discussion

The results from this large prospective study did not provide evidence for a protective association of total TAC and prostate cancer incidence or progression. However for dietary TAC there was an inverse association with total and advanced prostate cancers. The opposite effect was seen for supplemental TAC and lethal and advanced cancers. There is a suggestion that different sources of TAC may have different associations with risk. For example, coffee, which comprises a large proportion of dietary TAC, was inversely associated with risk of total, advanced and lethal prostate cancer. This effect may either be related to the specific antioxidants found in coffee, or to non-antioxidant coffee compounds. One could argue that it is possible that some antioxidants in coffee, due to their in vivo distribution could reach higher concentration in prostate tissue as is the case with lycopene from tomatoes [18]. Other possible mechanisms for the apparent protective effect of coffee can be that coffee inhibits intestinal glucose absorption, and also lowers circulating levels of c-peptide. Coffee may also inflict on the levels of circulating sex-hormones since it affects the levels of SHBG (sex hormone-binding globulin) These and other possible mechanisms has been reviewed in the previous manuscript on coffee intake and prostate cancer risk in the Health Professionals Follow-up Study. [17]. Coffee intake is easier to measure more accurately than other different types of antioxidant containing foods that are consumed less frequently, and therefore easier to find a true association. Residual confounding could be the reason the other antioxidant containing foods were not significantly associated with prostate cancer risk since registration of for example different types of fruits are more uncertain.

However, the total TAC in the diet does not seem to provide any protective effect for prostate cancer. On the other hand, high intake of antioxidants derived from supplements was associated with increased risk for lethal and advanced prostate cancer. The main contributor to the antioxidant intake from supplements in the Health Professionals Follow-Up study is vitamin C. There are in vitro data suggesting that at higher concentrations, vitamin C, may work as a pro-oxidant [19, 20]. The PLCO trial reported no adverse effect of vitamin C, but the number of cases was considerably lower than in our study, and lethal/fatal prostate cancers were not analyzed separately [21]. A large cohort study from Netherlands looked at intake of vitamin C from diet and supplements and found no association between the exposure and prostate cancer incidence [22]. In Physicians Health Study II, the effect of supplemental Vitamin C and Vitamin E on prostate cancer incidence was tested in a factorial design. The Vitamin C dose used was 500 mg daily, and the adjusted RR for prostate cancer incidence was 1.02(0.90-1.15). For prostate cancer deaths the adjusted RR was 1.46 (0.92-2.31) with 45 deaths in the active group vs. 31 in the placebo group[23].

Multivitamins is the other big contributor to supplemental TAC intake. A few studies have addressed the issue with multivitamin intake and the association with prostate cancer. Lawson et. al who found almost 1.3-fold increased risk for advanced prostate cancer and almost 2-fold increased risk for fatal prostate cancer among those who consumed more than seven times per week compared to never users [24]. In the Cancer Prevention Study II, the authors reported increased prostate cancer mortality among multivitamin users with a high consumption of multivitamins [25]. Since the association was only seen in lethal and advanced cancer and not for total prostate cancer, it may be a chance finding. There is a higher intake of calcium in the highest quintile of supplementary TAC, and the association may be influenced by the higher calcium intake in these individuals. In the multivariate models calcium was adjusted for. Reverse causation may be another possible explanation. Cases in the lethal and advanced prostate cancer groups may experience disease related symptoms as fatigue and prostate related symptoms long before diagnosis, and could have been using supplements for some time. Whether the association with antioxidant intake derived from dietary supplement use and lethal and advanced prostate cancer is due to the supplement use itself, or an unidentified behavior related to the supplement use is unknown and warrants further investigation.

The inverse association between total fruit and vegetables (servings/day) was only seen in the less serious disease categories. This finding is in line with other publications reporting no or weak associations between fruit & vegetable intake and prostate cancer risk[26].

There are several limitations to this study. First, the FRAP assay only measures the in vitro antioxidant activity of foods and supplements. It does not necessarily reflect the in vivo situation, since the body's total antioxidant defense system is comprised of both endogenous and exogenous antioxidants. The endogenous antioxidant system can be induced by exposure to different stimuli such as diet, and antioxidant enzymes such as superoxide dismutase (SOD) may be more or less effective due to genetic polymorphisms [27-29]. The bioavailability of all the different antioxidants is not fully known, and different substances have different bioavailability and metabolism [30]. The analysis of total antioxidant content based on an in vitro assay is therefore an approximation. This may underestimate the true association between TAC intake and prostate cancer.

Second, the food frequency questionnaire was not originally designed to record specific antioxidant rich foods. Some specific exotic foods such as pomegranates, and exotic berries rich in antioxidants and different types of spices with very high antioxidant content were not recorded. Given the low frequency of consumption of such foods in the US, it is unlikely that this has biased the results. In addition, the FFQ has not been validated for TAC intake; however, the correlations between two-week dietary records and FFQ-reported intakes for the major food items contributing to TAC are high (Coffee: 0.92, Tea: 0.77, Orange juice: 0.78, Red wine: 0.83).

There are several strengths to this study. Most important, the large sample size and the 22 year follow-up with a large number of cases provides the opportunity to study various prostate cancer disease outcomes, which is important given the biological heterogeneity of prostate cancers. The repeated measurement of diets every four years reduces the random within-person measurement error and allows us to account for changes in diet over time [13]. During follow-up the information on possible confounding factors were also repeatedly updated allowing for an accurate control of confounding. We know many good dietary sources of well known antioxidants such as beta carotene, vitamin E and vitamin C. Natural foods contain a vast amount of different bioactive substances not yet identified. Their possible biological effects and antioxidant properties are not fully known. The FRAP assay will capture the antioxidant potential in each food with an electrochemical value regardless of the source of the contribution. Both known and unknown substances with antioxidant properties will be assessed. Possible synergistic effects will also be taken into account.

In conclusion, our study did not provide convincing evidence of an association between total antioxidant intake (TAC) measured by FRAP and incidence of prostate cancer. The possible protective effect seen for dietary TAC and total and advanced prostate cancer could be due to the association seen for coffee. The finding of an association between high intake of antioxidants derived from supplements (mainly vitamin C) and risk of lethal and advanced prostate cancer warrants further investigation.

Impact.

This is the first study to examine prostate cancer incidence and the association with total antioxidant intake. A weak inverse association between dietary antioxidant intake and prostate cancer incidence was accounted for by coffee intake. A positive association for lethal and advanced prostate cancer and antioxidant intake from dietary supplements was found.

Antioxidants from dietary supplements and diet were separately analyzed. Many cases and long follow up time gives the results a high validity.

Table 1.

Baseline (1986) characteristics of the HPFS population by Dietary TAC, supplementary TAC (supplements only) and Total TAC (diet and supplements) quintiles (energy-adjusted quintiles, Q1, Q3, Q5 are shown) (N=47,896)

| Dietary TAC | Supplementary TAC | Total TAC | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q1 | Q3 | Q5 | Q1 | Q3 | Q5 | Q1 | Q3 | Q5 | |

| No. of participants | 12005 | 8557 | 9912 | 14121 | 8769 | 9961 | 12170 | 8323 | 9717 |

| Mean age (years) | 53.3 | 55.1 | 54.4 | 54.5 | 54.2 | 56.2 | 53.5 | 54.7 | 54.7 |

| African-American (%) | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Asian (%) | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| Current smoker (%) | 6 | 9 | 14 | 10 | 10 | 9 | 7 | 10 | 11 |

| In highest quintile vigorous activity (%) | 14 | 15 | 15 | 13 | 15 | 19 | 13 | 15 | 19 |

| Diabetes mellitus (%) | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Mean body mass index at age 21 (kg/m2) | 22.8 | 23.0 | 23.3 | 23.1 | 22.9 | 23.1 | 22.8 | 23.1 | 23.1 |

| Mean body mass index (kg/m2) | 25.5 | 25.6 | 25.7 | 25.7 | 25.5 | 25.2 | 25.6 | 25.6 | 25.4 |

| Mean height (cm) | 178 | 178 | 178 | 177 | 178 | 178 | 178 | 178 | 178 |

| PSA test 1994 (%) | 34 | 39 | 38 | 31 | 38 | 40 | 33 | 39 | 40 |

| Family history of prostate cancer (%) | 13 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 13 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 |

| Mean intakes of: | |||||||||

| Total energy (kcal/day) | 1928 | 2050 | 1905 | 1532 | 2440 | 1904 | 1928 | 2061 | 1911 |

| Calcium (mg/day) | 945 | 876 | 877 | 795 | 856 | 1104 | 859 | 851 | 1061 |

| Alpha-linolenic acid (g/day) | 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.1 |

| Tomato sauce (servings/day) | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| Processed meat (servings/day) | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.3 |

| Red meat (servings/day) | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.9 | 0.8 | 1.3 | 0.8 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.8 |

| Fish (servings/day) | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.5 |

| Coffee (cups/day) | 0.4 | 1.8 | 3.8 | 1.9 | 2.1 | 1.7 | 0.5 | 2.2 | 2.6 |

| Red wine (glasses/day) | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| Tea (cups/day) | 0.1 | 0.4 | 0.9 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 0.7 |

| Fruit (servings/day) | 1.3 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.2 | 1.7 | 1.7 | 132 | 1.6 | 1.7 |

| Vegetables (servings/day) | 2.8 | 3.5 | 3.6 | 2.7 | 3.8 | 3.5 | 2.8 | 3.4 | 3.7 |

| Fruit and vegetables (servings/day) | 4.1 | 5.0 | 5.2 | 4.0 | 5.5 | 5.2 | 4.1 | 5.0 | 5.4 |

| Alcohol consumption (grams/day) | 7.2 | 12.5 | 14.1 | 9.2 | 13.4 | 11.3 | 7.9 | 12.6 | 12.7 |

| Supplementary Vitamin E use (%) | 19 | 19 | 18 | 3 | 9 | 57 | 6 | 14 | 48 |

| Multivitamin use (%) | 41 | 42 | 41 | 10 | 46 | 82 | 24 | 38 | 72 |

| Supplementary Vitamin C use (%) | 37 | 35 | 34 | 0 | 28 | 96 | 11 | 30 | 81 |

Abbreviations: HPFS, Health Professionals Follow-up Study, FRAP, Ferric-reducing antioxidant power

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Throne Holst Foundation (KMR) and Radiumhospitalets Legater (KMR), National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health (P01 CA055075), by NCI/NIH Training Grant T32 CA09001 (to KMW, JLK), NIH Research Training Grant R25 CA098566 (to MME), the American Institute for Cancer Research (to JLK), and the Prostate Cancer Foundation (to LAM). The funding organizations had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript. In addition, we would like to thank the participants and staff of the Health Professionals Follow-up Study, and in particular Betsy Frost, Lauren McLaughlin and Tara Entwistle, for their valuable contributions as well as the following state cancer registries for their help: AL, AZ, AR, CA, CO, CT, DE, FL, GA, ID, IL, IN, IA, KY, LA, ME, MD, MA, MI, NE, NH, NJ, NY, NC, ND, OH, OK, OR, PA, RI, SC, TN, TX, VA, WA, WY.

References

- 1.Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, et al. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61:69–90. doi: 10.3322/caac.20107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Food, nutrition, physical activity, and the prevention of cancer: a global perspective. World Cancer research fund; Washington DC: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Seifried HE, McDonald SS, Anderson DE, et al. The antioxidant conundrum in cancer. Cancer Res. 2003;63:4295–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lippman SM, Klein EA, Goodman PJ, et al. Effect of selenium and vitamin E on risk of prostate cancer and other cancers: the Selenium and Vitamin E Cancer Prevention Trial (SELECT). JAMA. 2009;301:39–51. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yeum KJ, Beretta G, Krinsky NI, et al. Synergistic interactions of antioxidant nutrients in a biological model system. Nutrition. 2009;25:839–46. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2009.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blomhoff R. Dietary antioxidants and cardiovascular disease. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2005;16:47–54. doi: 10.1097/00041433-200502000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Packer L, Kraemer K, Rimbach G. Molecular aspects of lipoic acid in the prevention of diabetes complications. Nutrition. 2001;17:888–95. doi: 10.1016/s0899-9007(01)00658-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carlsen MH, Halvorsen BL, Holte K, et al. The total antioxidant content of more than 3100 foods, beverages, spices, herbs and supplements used worldwide. Nutr J. 2010;9:3. doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-9-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pellegrini N, Serafini M, Colombi B, et al. Total antioxidant capacity of plant foods, beverages and oils consumed in Italy assessed by three different in vitro assays. J Nutr. 2003;133:2812–9. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.9.2812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Benzie IF, Strain JJ. The ferric reducing ability of plasma (FRAP) as a measure of “antioxidant power”: the FRAP assay. Anal Biochem. 1996;239:70–6. doi: 10.1006/abio.1996.0292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Agalliu I, Kirsh VA, Kreiger N, et al. Oxidative balance score and risk of prostate cancer: results from a case-cohort study. Cancer Epidemiol. 2011;35:353–61. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2010.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Geybels MS, Verhage BA, van Schooten FJ, van den Brandt PA. Measures of combined antioxidant and pro-oxidant exposures and risk of overall and advanced stage prostate cancer. Ann Epidemiol. 2012;22:814–20. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2012.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Willett W. Nutritional epidemiology. 2 ed. Oxford University Press; New York: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mena S, Ortega A, Estrela JM. Oxidative stress in environmental-induced carcinogenesis. Mutat Res. 2009;674:36–44. doi: 10.1016/j.mrgentox.2008.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Serafini M, Jakszyn P, Lujan-Barroso L, et al. Dietary total antioxidant capacity and gastric cancer risk in the European prospective investigation into cancer and nutrition study. Int J Cancer. 2012;131:E544–54. doi: 10.1002/ijc.27347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.La Vecchia C, Decarli A, Serafini M, et al. Dietary total antioxidant capacity and colorectal cancer: A large case-control study in Italy. Int J Cancer. 2013 doi: 10.1002/ijc.28133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wilson KM, Kasperzyk JL, Rider JR, et al. Coffee Consumption and Prostate Cancer Risk and Progression in the Health Professionals Follow-up Study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011 doi: 10.1093/jnci/djr151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zaripheh S, Erdman JW., Jr The biodistribution of a single oral dose of [14C]-lycopene in rats prefed either a control or lycopene-enriched diet. J Nutr. 2005;135:2212–8. doi: 10.1093/jn/135.9.2212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Osiecki M, Ghanavi P, Atkinson K, et al. The ascorbic acid paradox. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;400:466–70. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.08.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Podmore ID, Griffiths HR, Herbert KE, et al. Vitamin C exhibits pro-oxidant properties. Nature. 1998;392:559. doi: 10.1038/33308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kirsh VA, Hayes RB, Mayne ST, et al. Supplemental and dietary vitamin E, beta-carotene, and vitamin C intakes and prostate cancer risk. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:245–54. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schuurman AG, Goldbohm RA, Brants HA, van den Brandt PA. A prospective cohort study on intake of retinol, vitamins C and E, and carotenoids and prostate cancer risk (Netherlands). Cancer Causes Control. 2002;13:573–82. doi: 10.1023/a:1016332208339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gaziano JM, Glynn RJ, Christen WG, et al. Vitamins E and C in the prevention of prostate and total cancer in men: the Physicians' Health Study II randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2009;301:52–62. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lawson KA, Wright ME, Subar A, et al. Multivitamin use and risk of prostate cancer in the National Institutes of Health-AARP Diet and Health Study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99:754–64. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djk177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stevens VL, McCullough ML, Diver WR, et al. Use of multivitamins and prostate cancer mortality in a large cohort of US men. Cancer Causes Control. 2005;16:643–50. doi: 10.1007/s10552-005-0384-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Key TJ, Allen N, Appleby P, et al. Fruits and vegetables and prostate cancer: no association among 1104 cases in a prospective study of 130544 men in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC). Int J Cancer. 2004;109:119–24. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Balstad TR, Carlsen H, Myhrstad MC, et al. Coffee, broccoli and spices are strong inducers of electrophile response element-dependent transcription in vitro and in vivo - Studies in electrophile response element transgenic mice. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2011;55:185–97. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201000204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Myhrstad MC, Carlsen H, Dahl LI, et al. Bilberry extracts induce gene expression through the electrophile response element. Nutr Cancer. 2006;54:94–101. doi: 10.1207/s15327914nc5401_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sutton A, Khoury H, Prip-Buus C, et al. The Ala16Val genetic dimorphism modulates the import of human manganese superoxide dismutase into rat liver mitochondria. Pharmacogenetics. 2003;13:145–57. doi: 10.1097/01.fpc.0000054067.64000.8f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kahle K, Kempf M, Schreier P, et al. Intestinal transit and systemic metabolism of apple polyphenols. Eur J Nutr. 2010 doi: 10.1007/s00394-010-0157-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]