Abstract

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are key signaling molecules produced in response to biotic and abiotic stresses that trigger a variety of plant defense responses. Cross-tolerance, the enhanced ability of a plant to tolerate multiple stresses, has been suggested to result partly from overlap between ROS signaling mechanisms. Cross-tolerance can manifest itself both as a positive genetic correlation between tolerance to different stresses (inherent cross-tolerance), and as the priming of systemic plant tolerance through previous exposure to another type of stress (induced cross-tolerance). Research in model organisms suggests that cross-tolerance could be used to benefit the agronomy and breeding of crop plants. However, research under field conditions has been scarce and critical issues including the timing, duration, and intensity of a stressor, as well as its interactions with other biotic and abiotic factors, remain to be addressed. Potential applications include the use of chemical stressors to screen for stress-resistant genotypes in breeding programs and the agronomic use of chemical inducers of plant defense for plant protection. Success of these applications will rely on improving our understanding of how ROS signals travel systemically and persist over time, and of how genetic correlations between resistance to ROS, biotic, and abiotic stresses are shaped by cooperative and antagonistic interactions within the underlying signaling pathways.

Keywords: systemic resistance, oxidative stress, GST, oxylipin, quantitative disease resistance, acclimation

INTRODUCTION

As sessile organisms, plants must adapt to adversity. Diverse biotic and abiotic stresses trigger systemic defense responses that involve the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS). This review discusses overlap between ROS-inducing stress responses as a possible explanation for two distinct phenomena: the enhancement of plant stress tolerance following previous exposure to another type of stress (induced cross-tolerance), and the ability of specific genetic variants to provide resistance to multiple distinct stresses (inherent cross-tolerance). Since ROS-triggered reactions mediate stresses that impact crop yield and quality, we also consider the gaps in the knowledge required to translate this research from model plants to crops.

ROS HOMEOSTASIS AND LOCALIZATION

Reactive oxygen species are unstable molecules produced both as a result of normal aerobic metabolic processes inside the plant cell, and in response to abiotic stresses including drought, heat, high salinity, high light, osmotic stress, metal toxicity, and the presence of xenobiotics like herbicides and ozone (O3). ROS are also produced in response to biotic stresses during the ‘oxidative burst.’ ROS molecules include superoxide (O2-), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), and singlet oxygen (O2*), and cause cell damage through lipid and protein oxidation and nucleic acid degradation (Apel and Hirt, 2004). The conflict between ROS toxicity and signaling roles has led to a tightly regulated equilibrium between ROS generation and scavenging. Oxidative stress in plant cells results from a disturbance in this equilibrium (Halliwell, 2006) and triggers both enzymatic and non-enzymatic mechanisms for scavenging free oxygen radicals. Non-enzymatic scavenging mechanisms involve the production of antioxidants including anthocyanins, ascorbate, carotenoids, and glutathione. Enzymatic scavenging mechanisms include the production of superoxide dismutase (SOD), ascorbate peroxidase (APX), and catalase (CAT; Apel and Hirt, 2004). Glutathione S-transferases (GSTs) and cytochrome P450s also scavenge ROS or their by-products.

Reactive oxygen species localization is specific to the type of stress to which the plant is subjected. Physical stresses that lower the rate of carbon fixation lead to photooxidative stress, which involves light-dependent ROS overproduction in the chloroplast. Such stresses include drought, high salinity, high temperature and xenobiotic compounds like methyl viologen (MV; “paraquat”). In contrast, O3 treatment, H202 treatment, and pathogen attack induce the accumulation of ROS in the apoplast. O3 is delivered directly into the extracellular space via stomates, where it is broken down into hydrogen peroxide and superoxide (Vainonen and Kangasjärvi, 2014). During the oxidative burst produced in response to pathogen attack, a class of NADPH oxidases in the cell membrane (respiratory burst oxidase homologues, or RBOHs) reduce oxygen into superoxide, which quickly forms hydrogen peroxide and diffuses from cell to cell through the extracellular space. Specific isozymes of APX and SOD localize to the cytosol, chloroplasts, apoplast, peroxisomes and mitochondria, whereas CAT localizes exclusively to peroxisomes. Lipid-soluble non-enzymatic antioxidants like anthocyanins and carotenoids are associated with cell and organelle membranes, while water soluble ascorbate and glutathione localize to the cytosol, chloroplasts, and other subcellular compartments (Mittler, 2002).

ROS AS BASAL RESISTANCE SIGNALING MOLECULES LINKING BIOTIC AND ABIOTIC STRESS

SENSING

It is not clear exactly how plant cells sense ROS, as specific ROS receptors have not yet been identified. One possibility is that ROS directly modify redox-sensitive proteins, including phosphatases (Apel and Hirt, 2004), and heat shock transcription factors (HSFs; Miller and Mittler, 2006). In Arabidopsis, overexpression of HSF-A1b conferred higher resistance to both drought and bacterial infection; this response was found to be dependent on H2O2 signaling but independent of hormone signaling, placing it within the basal immune system (Bechtold et al., 2013). Transcriptome analysis of rice responses to cold, heat and oxidative stress also suggests that HSFs play a crucial role in basal immunity. Binding sites for HSFs were significantly enriched in the promoters of upregulated genes in all three stress treatments, leading to the hypothesis that “the HSF/HSP regulon may be regarded as the central regulator of plant stress responses involving ROS accumulation” (Mittal et al., 2012).

SIGNAL TRANSDUCTION

Zinc finger and WRKY transcription factors are both widely involved in the regulation of ROS-related defense genes. The expression of several zinc finger proteins in Arabidopsis, ZAT7 and ZAT12, is strongly upregulated by oxidative stress in APX knockouts and in response to H202 and MV treatment (Rizhsky, 2004). ZAT12 was later found to be involved in the regulation of resistance to high light, osmotic and oxidative stress, with overexpression mutants showing higher stress tolerance (Davletova et al., 2005). ZAT10 has a dual role as both inducer and repressor of ROS-responsive genes under salt, drought and osmotic stresses (Sakamoto et al., 2004; Mittler et al., 2006). ZAT6 positively regulates resistance to salt, drought, and chilling stress as well as resistance to bacterial infection by modulating ROS-level and SA-related gene expression (Shi et al., 2014). The WRKY transcription factor family includes several genes important for the disease response (Pandey and Somssich, 2009), and WRKY transcription factors participate in the cross-talk between biotic and abiotic resistance through ROS gene-related modulation (Mittler et al., 2011). WRKY25 is induced under heat, osmotic and oxidative stress, and appears to be regulated by ZAT12. Unlike ZAT12, however, its overexpression did not result in significantly higher tolerance (Rizhsky, 2004). WRKY70 is a key regulator of plant disease response and a known crossroads between the SA and JA pathways, being induced by the former and inhibited by the latter (Li et al., 2004), and interacts directly with ZAT7 (Ciftci-Yilmaz et al., 2007). WRKY30 is rapidly induced by inoculation with several pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), and oxidative (MV) stress; its overexpression in young plants conferred resistance to oxidative and salt stress (Scarpeci et al., 2013, p. 30).

SIGNAL AMPLIFICATION

Respiratory burst oxidase homologues (RBOHs) are a small family of membrane-bound proteins with a major role in the creation and amplification of the ROS signal in a variety of plant immune and developmental responses. RBOHs are responsible for releasing O2- into the apoplast and are regulated by Ca2+ through EF-hand motifs in the N terminus (Baxter et al., 2014). This extracellular ROS activity is thought to be responsible for the activation and amplification of a self-propagating ROS wave, thus explaining the systemic nature of the immune response (Mittler et al., 2011). Given the role of Ca2+ in activating RBOHs, calcium-dependent protein kinases (CDPKs) are another possible node of convergence in ROS signaling. Tobacco leaves infiltrated with a constitutively active version of NtCDPK2, usually only activated by pathogen attack, responded to mild abiotic stress with an expanding HR (Kobayashi et al., 2007). Additionally, plasma membrane Ca2+ transporters were shown to mediate tolerance to different oxidative stresses in virus-inoculated tobacco (Shabala et al., 2011).

ROLE OF ROS IN SYSTEMIC RESPONSES AND PROGRAMMED CELL DEATH

Systemic resistance primes plant-wide defense responses following an initial localized trigger. Systemic acquired resistance (SAR) refers to the enhanced response observed after pathogen attack, systemic acquired acclimation (SAA) to a similar response elicited from non-lethal doses of abiotic stressors, and induced systemic resistance (ISR) to the response to symbiotic associations with mutualistic microbes. Systemic responses to wounding and herbivory have also been described (Baxter et al., 2014). While these responses have distinct molecular signatures, they all involve ROS signaling. Comparison of Arabidopsis transcriptome responses to a variety of stressors (MV, O3, fungal toxin, 3-aminotriazole herbicide, and antioxidant-compromised mutants) identified a core set of ROS-dependent response genes (Gadjev, 2006).

Treatment with both O3 and fungal elicitors activates an oxidative burst response and components of the HR signaling pathway (Sandermann, 1996; Wohlgemuth et al., 2002). The rcd1 mutant in Arabidopsis displays both high sensitivity to O3 and a deficient programmed cell death (PCD) response, which is known to be regulated by ROS (De Pinto et al., 2012). Transcriptome analysis of the rcd1 mutant found clusters of O3-upregulated genes with enrichment of GO terms “response to salicylic acid stimulus” and “response to bacterium.” In addition WRKY70 and SGT1b, required for ubiquitin mediated protein degradation, were found to be involved in regulation of ROS-induced PCD (Brosché et al., 2014).

CROSS-TOLERANCE MAY RESULT FROM ROS SIGNAL OVERLAP

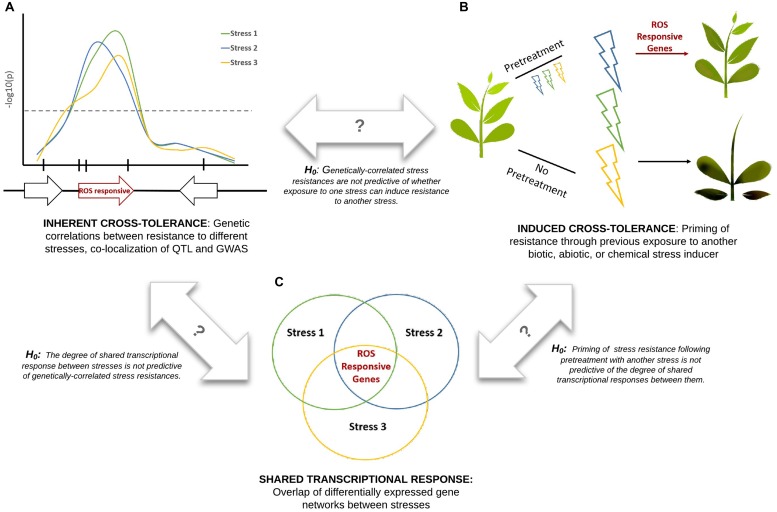

Cross-tolerance, also referred to as cross-resistance or cross-protection (Tippmann et al., 2006), refers to the enhanced ability of a plant to tolerate multiple stresses. Here we attempt to unify three distinct types of plant stress tolerance studies (Figure 1): datasets describing transcriptional overlap between stress responses; datasets describing the priming or suppression of plant stress responses following exposure to a different type of stress (induced cross-tolerance); and datasets describing genetic overlap between resistance to different stresses (inherent cross-tolerance). Comparison of these datasets within a single experimental system would create a powerful platform for understanding systemic resistance and would allow a series of null hypotheses to be tested (Figure 1). Correlations between these datasets may be due in part to common ROS signals that are refined to provide stress-specific information through differences in localization, amplitude, and frequency of the ROS electrical wave (Mittler et al., 2011).

FIGURE 1.

Integration of experimental approaches to studying plant cross-tolerance. Three hypothetical stresses (biotic or abiotic) are shown in blue, green, and yellow. Marker-trait association studies (A), pretreatment effect studies (B), and gene expression studies (C), when performed under consistent experimental conditions, can be used to test a series of null hypotheses. ROS signaling is proposed to play a key role in cross-tolerance responses.

INDUCED CROSS-TOLERANCE

Following the recognition of systemic resistance in plants, agronomists have pursued the possibility of inducing systemic resistance in crops through chemical means. A growing family of agrochemical products targeted as “defense-inducers” aims to emulate or induce the accumulation of H2O2 in SAR [thoroughly reviewed by (Gozzo and Faoro, 2013)]. Exogenously applied salicylic acid has been used to attempt to improve plant responses to drought (Alam et al., 2013), salt stress (Hasanuzzaman et al., 2014), iron-deficiency (Kong et al., 2014), pesticides (Singh et al., 2013), and heavy metals (Siddiqui et al., 2013). Some fungicides and herbicides appear to have fortuitous secondary uses as defense inducers. In field trials against soybean stem rot, early application of the diphenyl ether herbicide Lactofen was found to significantly reduce disease severity in a high disease-pressure environment (Dann et al., 1999), possibly due to the induced overexpression of PR proteins and thaumatin/osmotin-like proteins also involved in osmotic stress tolerance (Graham, 2005). Treatment of tobacco with the fungicide pyraclostrobin enhanced resistance to both tobacco mosaic virus and Pseudomonas spp. infection, even in SA-deficient mutants, suggesting a SA-independent response (Herms et al., 2002). Dual application of the fungicide chlorothalonil and the antiozonant compound EDU resulted in higher resistance to O3 injury and elevated levels of glutathione (Hassan, 2006). Pretreatment of potato roots with aluminum (Al3+) resulted in fourfold higher leaf resistance to late blight (Phytophthora infestans) and the accumulation of SA and distal NO (Arasimowicz-Jelonek et al., 2013). The common theme in these responses seems to be an initial disruption of cellular ROS homeostasis by the inducer, followed by enhanced detoxification capacity. The same principle is employed by herbicide safeners, which are chemical seed treatments that induce expression of detoxification enzymes (GSTs and cytochrome P450s) in the germinating seedling, protecting it from subsequent herbicide injury. The exact mechanisms through which safeners confer herbicide resistance are unknown, although oxidized lipids (“oxylipins”) have been proposed to play a key role (Riechers et al., 2010). A clear link between oxylipins and systemic resistance was demonstrated using the lipoxygenase3 (lox3) mutant of maize, which is deficient for 9-oxylipin production in roots and shows enhanced resistance to fungal diseases and constitutive ISR response (Constantino et al., 2013).

Direct application of ROS by oxidative agents has also been investigated as a potential means of inducing cross-tolerance. H2O2 is a known activator of antioxidant defenses and has been used as seed pretreatment for wheat planted into environments that experience drought and/or salt stress (Wahid et al., 2007; He and Gao, 2009). O3 is an attractive inducer because doses can be carefully calibrated for low toxicity. Inoculation of tobacco plants with either O3 or UV-light resulted in accumulation of SA and PR proteins and induced resistance to tobacco mosaic virus (Yalpani et al., 1994). Tomato plants showed increased resistance to cucumber mosaic virus after being regenerated from calli previously treated with a low dosage of O3 (Sudhakar et al., 2007), suggesting that the memory of oxidative stress persists through ontogeny.

The success of inducers has been varied, possibly due to limited understanding of the dynamics between triggers and resistant responses. For example, bean plants pretreated with BTH, a functional analog of SA, were more sensitive to O3 fumigation 1–2 days after BTH pre-treatment but more resistant to O3 fumigation 5–7 days after BTH pre-treatment (Iriti et al., 2003). Many other studies similarly highlight the importance of dosage and timing to the success of an inducer (Sandermann, 1996; Rao and Davis, 1999; Geetha and Shetty, 2002; Buschmann et al., 2005; Herman et al., 2008; Hayat et al., 2010).

INHERENT CROSS-TOLERANCE

Development of crop varieties with durable resistance to multiple stresses is a nearly universal goal in plant breeding. Qualitative, race-specific disease resistance can be quickly overcome because of the selective pressure it imposes on pathogen populations. Quantitative, broad-spectrum disease resistance (QDR) involves multiple loci encoding resistance alleles, usually of modest effect, that provide a more durable resistance against multiple races and species of pathogen. QDR has also been shown to improve the durability of qualitative resistance (Brun et al., 2010). Empirical evidence for QDR arises from QTL meta-analysis showing clustering of QTL for different diseases (Wisser et al., 2005), and from high genetic correlations between resistances to different diseases observed across collections of genetically diverse individuals (Wisser et al., 2011). The enhanced capacity of specific individuals within a species to resist multiple stresses could result from a variety of mechanisms, including plant and cell architecture, signal transduction, and the detoxification response (Poland et al., 2009). However, inherent cross-tolerance between widely divergent stresses suggests a basal generalized ability to avoid cellular redox disequilibrium.

A plant’s ability to tolerate exogenously applied ROS has been used as a simple initial screen for multiple stress resistance. A survey of diverse Arabidopsis accessions found great natural variation in O3 tolerance (Brosché et al., 2010). Shared resistance to O3, SO3 and MV was found between tolerant Lolium perenne and tobacco biotypes (Shaaltiel et al., 1988). A global survey of Medicago truncatula accessions found a positive correlation between tolerance to oxidative stress and drought stress, as well as a significant negative correlation between basal ROS level and oxidative stress tolerance (Puckette et al., 2007). Tolerances to oxidative stress and drought stress in a set of rice landraces and improved varieties were found to be strongly correlated both with each other and with population structure, with japonica lines and improved varieties showing higher tolerance to both stresses than indica lines (Iseki et al., 2013). A positive correlation between oxidative stress tolerance, antioxidant activity and drought tolerance was found in a set of maize inbred lines evaluated for resistance to MV, acifluorfen herbicide and SO2 (Malan et al., 1990). MV-based screening of progeny from a cross between a drought-tolerant and a drought-sensitive rice variety was used to predict drought tolerance in a dry-season rice breeding program (Iseki et al., 2014).

Glutathione-S-transferase (GST) genes play an important role in the maintenance of ROS equilibrium and have been widely reported to play a role in biotic and abiotic stress resistance (Wagner et al., 2002; Dean et al., 2005). Comparison of MV-induced stress transcriptomes between japonica and indica rice subspecies indicated GST activity as a major differentiated GO module (Liu et al., 2010). A multivariate GWAS to identify sources of multiple disease resistance in maize pinpointed a GST gene associated with resistance to three major fungal diseases (Wisser et al., 2011). In screens for resistance to specific diseases in the high resolution nested association mapping population of maize, GSTs, cytochrome P450s, and receptor-like kinases (RLKs) were identified as candidates (Kump et al., 2011). A meta-analysis of published QTL studies in rice for resistance to several diseases yielded a type III GST as a candidate gene for functional studies (Wisser et al., 2005). It is not clear whether GSTs are acting directly on specific, pathogen-derived toxins or indirectly on ROS-derived compounds, like peroxidized lipids, that result from stress.

MODEL TO CROP

Translational genomics relies on conservation of gene function and network architecture between model and crop species, and the likelihood of success is expected to depend on the model-crop divergence time. However, networks of co-expressed genes are more stable across evolutionary time than individual genes. For example, a study comparing abiotic stress-responsive gene networks between Arabidopsis and Medicago found that ~60% of Arabidopsis genes could be assigned a clear ortholog in Medicago despite a divergence time of ~125 million years (Hyung et al., 2014). Construction of weighted co-expression gene networks in Arabidopsis and rice under bacterial and drought stress identified a number of “response to oxidative stress”-annotated modules that were upregulated in both species in response to both stresses (Shaik and Ramakrishna, 2013), suggesting that with appropriate methodology, biological inferences can be translated between distantly related genomes. Another hurdle in translational genomics is the transition from greenhouse or growth chamber to a field environment. Stress factors in controlled environments are usually imposed in isolation, whereas crop plants under field conditions are nearly always exposed to multiple stresses that may interact with each other (Mittler, 2006). Sudden imposition of stress in controlled environments also downplays the importance of plant acclimation and the mild, chronic stresses that prevail in nature. Part of the solution may involve the adoption of new technologies that allow increased experimental control over field environments. For example, rainout shelters allow manipulation of soil water profile and drought stress in a field setting, and Free Air Concentration Enrichment (FACE) facilities alter atmospheric variables, including CO2 and O3 concentrations, to obtain realistic estimates of their effects on crop yields (Ort et al., 2006). Plant resistance to multiple stresses may be constrained by antagonistic interactions. However, evidence from transcriptional, quantitative genetic, and agronomic datasets shows that plants respond to multiple biotic and abiotic stresses using similar, ROS-mediated mechanisms. Deliberate integration of information between these different types of datasets will help us understand and exploit cross-tolerance, providing improved agronomic and genetic tools for a more sustainable, climate-resilient agriculture.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

Research supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant No. (PGR-1238030).

REFERENCES

- Alam M. M., Hasanuzzaman M., Nahar K., Fujita M. (2013). Exogenous salicylic acid ameliorates short-term drought stress in mustard (Brassica juncea L.) seedlings by up-regulating the antioxidant defense and glyoxalase system. Aust. J. Crop Sci. 7 1053–1063. [Google Scholar]

- Apel K., Hirt H. (2004). Reactive oxygen species: metabolism, oxidative stress, an,d signal transduction. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 55 373–399 10.1146/annurev.arplant.55.031903.141701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arasimowicz-Jelonek M., Floryszak-Wieczorek J., Drzewiecka K., Chmielowska-Bąk J., Abramowski D., Izbiańska K. (2013). Aluminum induces cross-resistance of potato to Phytophthora infestans. Planta 239 679–694 10.1007/s00425-013-2008-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baxter A., Mittler R., Suzuki N. (2014). ROS as key players in plant stress signalling. J. Exp. Bot. 65 1229–1240 10.1093/jxb/ert375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bechtold U., Albihlal W. S., Lawson T., Fryer M. J., Sparrow P. A. C., Richard F., et al. (2013). Arabidopsis HEAT SHOCK TRANSCRIPTION FACTORA1b overexpression enhances water productivity, resistance to drought, and infection. J. Exp. Bot. 64 3467–3481 10.1093/jxb/ert185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brosché M., Blomster T., Salojärvi J., Cui F., Sipari N., Leppälä J., et al. (2014). Transcriptomics and functional genomics of ROS-induced cell death regulation by RADICAL-INDUCED CELL DEATH1. PLoS Genet. 10:e1004112 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brosché M., Merilo E., Mayer F., Pechter P., Puzõrjova I., Brader G., et al. (2010). Natural variation in ozone sensitivity among Arabidopsis thaliana accessions and its relation to stomatal conductance. Plant Cell Environ. 33 914–925 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2010.02116.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brun H., Chèvre A.-M., Fitt B. D., Powers S., Besnard A.-L., Ermel M., et al. (2010). Quantitative resistance increases the durability of qualitative resistance to Leptosphaeria maculans in Brassica napus. New Phytol. 185 285–299 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2009.03049.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buschmann H., Fan Z., Sauerborn J. (2005). Effect of resistance-inducing agents on sunflower (Helianthus annuus L.) and its infestation with the parasitic weed Orobanche cumana Wallr. J. Plant Dis. Prot. 112 386–397. [Google Scholar]

- Ciftci-Yilmaz S., Morsy M. R., Song L., Coutu A., Krizek B. A., Lewis M. W., et al. (2007). The EAR-motif of the Cys2/His2-type zinc finger protein Zat7 plays a key role in the defense response of Arabidopsis to salinity stress. J. Biol. Chem. 282 9260–9268 10.1074/jbc.M611093200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Constantino N. N., Mastouri F., Damarwinasis R., Borrego E. J., Moran-Diez M. E., Kenerley C. M., et al. (2013). Root-expressed maize lipoxygenase 3 negatively regulates induced systemic resistance to Colletotrichum graminicola in shoots. Front. Plant Sci. 4:510 10.3389/fpls.2013.00510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dann E. K., Diers B. W., Hammerschmidt R. (1999). Suppression of Sclerotinia stem rot of soybean by lactofen herbicide treatment. Phytopathology 89 598–602 10.1094/PHYTO.1999.89.7.598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davletova S., Schlauch K., Coutu J., Mittler R. (2005). The zinc-finger protein Zat12 plays a central role in reactive oxygen and abiotic stress signaling in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 139 847–856 10.1104/pp.105.068254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean J. D., Goodwin P. H., Hsiang T. (2005). Induction of glutathione S-transferase genes of Nicotiana benthamiana following infection by Colletotrichum destructivum and C. orbiculare and involvement of one in resistance. J. Exp. Bot. 56 1525–1533 10.1093/jxb/eri145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Pinto M. C., Locato V., De Gara L. (2012). Redox regulation in plant programmed cell death. Plant Cell Environ. 35 234–244 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2011.02387.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadjev I. (2006). Transcriptomic footprints disclose specificity of reactive oxygen species signaling in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 141 436–445 10.1104/pp.106.078717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geetha H. M., Shetty H. S. (2002). Induction of resistance in pearl millet against downy mildew disease caused bySclerospora graminicola using benzothiadiazole, calcium chloride and hydrogen peroxide—a comparative evaluation. Crop Prot. 21 601–610 10.1016/S0261-2194(01)00150-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gozzo F., Faoro F. (2013). Systemic acquired resistance (50 years after discovery): moving from the lab to the field. J. Agric. Food Chem. 61 12473–12491 10.1021/jf404156x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham M. Y. (2005). The diphenylether herbicide lactofen induces cell death and expression of defense-related genes in soybean. Plant Physiol. 139 1784–1794 10.1104/pp.105.068676 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halliwell B. (2006). Reactive species and antioxidants. Redox biology is a fundamental theme of aerobic life. Plant Physiol. 141 312–322 10.1104/pp.106.077073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasanuzzaman M., Alam M. M., Nahar K., Ahamed K. U., Fujita M. (2014). Exogenous salicylic acid alleviates salt stress-induced oxidative damage in Brassica napus by enhancing the antioxidant defense and glyoxalase systems. Aust. J. Crop Sci. 8 631–639. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan I. A. (2006). Physiological and biochemical response of potato (Solanum tuberosum L. cv. Kara) to O3 and antioxidant chemicals: possible roles of antioxidant enzymes. Ann. Appl. Biol. 148 197–206 10.1111/j.1744-7348.2006.00058.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hayat Q., Hayat S., Irfan M., Ahmad A. (2010). Effect of exogenous salicylic acid under changing environment: a review. Environ. Exp. Bot. 68 14–25 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2009.08.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- He L., Gao Z. (2009). Pretreatment of seed with H2O2 enhances drought tolerance of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) seedlings. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 8:22. [Google Scholar]

- Herman M. A. B., Davidson J. K., Smart C. D. (2008). Induction of plant defense gene expression by plant activators and Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato in greenhouse-grown tomatoes. Phytopathology 98 1226–1232 10.1094/PHYTO-98-11-1226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herms S., Seehaus K., Koehle H., Conrath U. (2002). A strobilurin fungicide enhances the resistance of tobacco against tobacco mosaic virus and Pseudomonas syringae pv tabaci. Plant Physiol. 130 120–127 10.1104/pp.004432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyung D., Lee C., Kim J.-H., Yoo D., Seo Y.-S., Jeong S.-C., et al. (2014). Cross-family translational genomics of abiotic stress-responsive genes between Arabidopsis and Medicago truncatula. PLoS ONE 9:e91721 10.1371/journal.pone.0091721 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iriti M., Rabotti G., De Ascensao A., Faoro F. (2003). Benzothiadiazole-induced resistance modulates ozone tolerance. J. Agric. Food Chem. 51 4308–4314 10.1021/jf034308w [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iseki K., Homma K., Endo T., Shiraiwa T. (2013). Genotypic diversity of cross-tolerance to oxidative and drought stresses in rice seedlings evaluated by the maximum quantum yield of photosystem II and membrane stability. Plant Prod. Sci. 16 295–304 10.1626/pps.16.295 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Iseki K., Homma K., Shiraiwa T., Jongdee B., Mekwatanakarn P. (2014). The effects of cross-tolerance to oxidative stress and drought stress on rice dry matter production under aerobic conditions. Field Crops Res. 163 18–23 10.1016/j.fcr.2014.04.012 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi M., Ohura I., Kawakita K., Yokota N., Fujiwara M., Shimamoto K., et al. (2007). Calcium-dependent protein kinases regulate the production of reactive oxygen species by potato NADPH oxidase. Plant Cell 19 1065–1080 10.1105/tpc.106.048884 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong J., Dong Y., Xu L., Liu S., Bai X. (2014). Effects of foliar application of salicylic acid and nitric oxide in alleviating iron deficiency induced chlorosis of Arachis hypogaea L. Bot. Stud. 55 9–10 10.1186/1999-3110-55-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kump K. L., Bradbury P. J., Wisser R. J., Buckler E. S., Belcher A. R., Oropeza-Rosas M. A., et al. (2011). Genome-wide association study of quantitative resistance to southern leaf blight in the maize nested association mapping population. Nat. Genet. 43 163–168 10.1038/ng.747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Brader G., Palva E. T. (2004). The WRKY70 transcription factor: a node of convergence for jasmonate-mediated and salicylate-mediated signals in plant defense. Plant Cell Online 16 319–331 10.1105/tpc.016980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu F., Xu W., Wei Q., Zhang Z., Xing Z., Tan L., et al. (2010). Gene expression profiles deciphering rice phenotypic variation between Nipponbare (Japonica) and 93-11 (Indica) during oxidative stress. PLoS ONE 5:e8632 10.1371/journal.pone.0008632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malan C., Greyling M., Gressel J. (1990). Correlation between CuZn superoxide dismutase and glutathione reductase, and environmental and xenobiotic stress tolerance in maize inbreds. Plant Sci. 69 157–166 10.1016/0168-9452(90)90114-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miller G., Mittler R. (2006). Could heat shock transcription factors function as hydrogen peroxide sensors in plants? Ann. Bot. 98 279–288 10.1093/aob/mcl107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittal D., Madhyastha D. A., Grover A. (2012). Genome-wide transcriptional profiles during temperature and oxidative stress reveal coordinated expression patterns and overlapping regulons in rice. PLoS ONE 7:e40899 10.1371/journal.pone.0040899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittler R. (2002). Oxidative stress, antioxidants and stress tolerance. Trends Plant Sci. 7 405–410 10.1016/S1360-1385(02)02312-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittler R. (2006). Abiotic stress, the field environment and stress combination. Trends Plant Sci. 11 15–19 10.1016/j.tplants.2005.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittler R., Kim Y., Song L., Coutu J., Coutu A., Ciftci-Yilmaz S., et al. (2006). Gain- and loss-of-function mutations in Zat10 enhance the tolerance of plants to abiotic stress. FEBS Lett. 580 6537–6542 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.11.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittler R., Vanderauwera S., Suzuki N., Miller G., Tognetti V. B., Vandepoele K., et al. (2011). ROS signaling: the new wave? Trends Plant Sci. 16 300–309 10.1016/j.tplants.2011.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ort D. R., Ainsworth E. A., Aldea M., Allen D. J., Bernacchi C. J., Berenbaum M. R., et al. (2006). “SoyFACE: the Effects and Interactions of Elevated [CO2] and [O3] on Soybean,” in Managed Ecosystems and CO2 Ecological Studies eds Nösberger P. D. J., Long P. D. S. P., Norby P. D. R. J., Stitt P. D. M., Hendrey P. D. G. R., Blum D. H. (Heidelberg: Springer; ) 71–86. [Google Scholar]

- Pandey S. P., Somssich I. E. (2009). The role of WRKY transcription factors in plant immunity. Plant Physiol. 150 1648–1655 10.1104/pp.109.138990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poland J. A., Balint-Kurti P. J., Wisser R. J., Pratt R. C., Nelson R. J. (2009). Shades of gray: the world of quantitative disease resistance. Trends Plant Sci. 14 21–29 10.1016/j.tplants.2008.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puckette M. C., Weng H., Mahalingam R. (2007). Physiological and biochemical responses to acute ozone-induced oxidative stress in Medicago truncatula. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 45 70–79 10.1016/j.plaphy.2006.12.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao M. V., Davis K. R. (1999). Ozone-induced cell death occurs via two distinct mechanisms in Arabidopsis: the role of salicylic acid. Plant J. 17 603–614 10.1046/j.1365-313X.1999.00400.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riechers D. E., Kreuz K., Zhang Q. (2010). Detoxification without intoxication: herbicide safeners activate plant defense gene expression. Plant Physiol. 153 3–13 10.1104/pp.110.153601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizhsky L. (2004). The zinc finger protein Zat12 is required for cytosolic ascorbate peroxidase 1 expression during oxidative stress in Arabidopsis. J. Biol. Chem. 279 11736–11743 10.1074/jbc.M313350200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakamoto H., Maruyama K., Sakuma Y., Meshi T., Iwabuchi M., Shinozaki K., et al. (2004). Arabidopsis Cys2/His2-type zinc-finger proteins function as transcription repressors under drought, cold, and high-salinity stress conditions. Plant Physiol. 136 2734–2746 10.1104/pp.104.046599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandermann H., Jr. (1996). Ozone and plant health. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 34 347–366 10.1146/annurev.phyto.34.1.347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scarpeci T., Zanor M., Bernd Mueller R., Valle E. (2013). Overexpression of AtWRKY30 enhances abiotic stress tolerance during early growth stages in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Mol. Biol. 83 265–277 10.1007/s11103-013-0090-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaaltiel Y., Glazer A., Bocion P. F., Gressel J. (1988). Cross tolerance to herbicidal and environmental oxidants of plant biotypes tolerant to paraquat, sulfur dioxide, and ozone. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 31 13–23 10.1016/0048-3575(88)90024-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shabala S., Baekgaard L., Shabala L., Fuglsang A., Babourina O., Palmgren M. G., et al. (2011). Plasma membrane Ca2+ transporters mediate virus-induced acquired resistance to oxidative stress. Plant Cell Environ 34 406–417 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2010.02251.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaik R., Ramakrishna W. (2013). Genes and co-expression modules common to drought and bacterial stress responses in Arabidopsis and rice. PLoS ONE 8:e77261 10.1371/journal.pone.0077261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi H., Wang X., Ye T., Cheng F., Deng J., Yang P., et al. (2014). The Cysteine2/Histidine2-type transcription factor ZINC FINGER OF ARABIDOPSIS THALIANA6 modulates biotic and abiotic stress responses by activating salicylic acid-related genes and C-REPEAT-BINDING FACTOR genes in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 165 1367–1379 10.1104/pp.114.242404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siddiqui M. H., Al-Whaibi M. H., Ali H. M., Sakran A. M., Basalah M. O., AlKhaishany M. Y. Y. (2013). Mitigation of nickel stress by the exogenous application of salicylic acid and nitric oxide in wheat. Aust. J. Crop Sci. 7 1780–1788. [Google Scholar]

- Singh A., Srivastava A. K., Singh A. K. (2013). Exogenous application of salicylic acid to alleviate the toxic effects of insecticides in Vicia faba L. Environ. Toxicol. 28 666–672 10.1002/tox.20745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sudhakar N., Nagendra-Prasad D., Mohan N., Murugesan K. (2007). Induction of systemic resistance in Lycopersicon esculentum cv. PKM1 (tomato) against cucumber mosaic virus by using ozone. J. Virol. Methods 139 71–77 10.1016/j.jviromet.2006.09.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tippmann H. F., Schlüter U., Collinge D. B., Teixeira da Silva J. A. (2006). Common themes in biotic and abiotic stress signalling in plants. Floric. Ornam. Plant Biotechnol. 3 52–67. [Google Scholar]

- Vainonen J. P., Kangasjärvi J. (2014). Plant signaling in acute ozone exposure. Plant Cell Environ. 10.1111/pce.12273 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner U., Edwards R., Dixon D. P., Mauch F. (2002). Probing the diversity of the Arabidopsis glutathione S-transferase gene family. Plant Mol. Biol. 49 515–532 10.1023/A:1015557300450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahid A., Perveen M., Gelani S., Basra S. M. (2007). Pretreatment of seed with H2O2 improves salt tolerance of wheat seedlings by alleviation of oxidative damage and expression of stress proteins. J. Plant Physiol. 164 283–294 10.1016/j.jplph.2006.01.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wisser R. J., Kolkman J. M., Patzoldt M. E., Holland J. B., Yu J., Krakowsky M., et al. (2011). Multivariate analysis of maize disease resistances suggests a pleiotropic genetic basis and implicates a GST gene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108 7339–7344 10.1073/pnas.1011739108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wisser R. J., Sun Q., Hulbert S. H., Kresovich S., Nelson R. J. (2005). Identification and characterization of regions of the rice genome associated With broad-spectrum, quantitative disease resistance. Genetics 169 2277–2293 10.1534/genetics.104.036327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wohlgemuth H., Mittelstrass K., Kschieschan S., Bender J., Weigel H.-J., Overmyer K., et al. (2002). Activation of an oxidative burst is a general feature of sensitive plants exposed to the air pollutant ozone. Plant Cell Environ. 25 717–726 10.1046/j.1365-3040.2002.00859.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yalpani N., Enyedi A. J., León J., Raskin I. (1994). Ultraviolet light and ozone stimulate accumulation of salicylic acid, pathogenesis-related proteins and virus resistance in tobacco. Planta 193 372–376 10.1007/BF00201815 [DOI] [Google Scholar]