Abstract

Median lethal dose (LD50) testing in mice is the ‘gold standard’ for evaluating the lethality of snake venoms and the effectiveness of interventions. As part of a study to determine the murine LD50 of the venom of 3 species of rattlesnake, temperature data were collected in an attempt to more precisely define humane endpoints. We used an ‘up-and-down’ methodology of estimating the LD50 that involved serial intraperitoneal injection of predetermined concentrations of venom. By using a rectal thermistor probe, body temperature was taken once before administration and at various times after venom exposure. All but one mouse showed a marked, immediate, dose-dependent drop in temperature of approximately 2 to 6 °C at 15 to 45 min after administration. The lowest temperature sustained by any surviving mouse was 33.2 °C. Surviving mice generally returned to near-baseline temperatures within 2 h after venom administration, whereas mice that did not survive continued to show a gradual decline in temperature until death or euthanasia. Logistic regression modeling controlling for the effects of baseline core body temperature and venom type showed that core body temperature was a significant predictor of survival. Linear regression of the interaction of time and survival was used to estimate temperatures predictive of death at the earliest time point and demonstrated that venom type had a significant influence on temperature values. Overall, our data suggest that core body temperature is a useful adjunct to monitoring for endpoints in LD50 studies and may be a valuable predictor of survival in venom studies.

Abbreviations: OECD, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

LD50 testing in mice has been used for many years to evaluate lethality of potential toxins, such as snake venoms, and is identified by the World Health Organization as the essential assay for preclinical evaluation of antivenins.61Strict adherence to the LD50 concept mandates using death as the endpoint for all animals under study. Nevertheless, as called for in the Guide, efforts have been applied toward identifying earlier endpoints to refine protocols to minimize pain and distress.27 For example, several groups have assessed core body temperature as an adjunct to determining endpoints in many areas of research, including LD50 evaluation of pathogen virulence and metal and alcohol toxicity; viral, bacterial and fungal infectious disease; and longevity studies.3,22,26,29-31,36,37,39,40,43,50,51,53-55,57,58,60 Using such an approach in venom toxicity studies holds promise for minimizing pain and distress by identifying earlier time points for euthanasia. In addition, body temperature may serve as a more robust and objective measure to use as a euthanasia criterion in experiments (such as Kaplan–Meier survival studies) when accurately measuring duration of survival is important.16 Potentially, investigators could euthanize animals based in part on a predetermined body temperature thereby mitigating error from subjective evaluation of clinical signs alone. With this goal in mind, we hypothesized that body temperature would prove to be a useful adjunct to monitoring for endpoints in a study we conducted in mice to estimate the LD50 of 3 rattlesnake venoms. The data we gathered support the use of temperature guidelines to assist in determining humane endpoints for mice used in rattlesnake venom LD50 studies.

Materials and Methods

Animals.

Outbred Swiss Webster (Taconic, Hudson, NY) female mice (age, 8 to 10 wk) were selected as the model of choice on the basis of their outbred genetic diversity and according to guidelines from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and Environmental Protection Agency.17,42 Mice were acclimated for 72 h and housed in an ABSL2, AAALAC-accredited biocontainment facility. Mice were group-housed in individually ventilated caging (56 air changes hourly; Innovive, San Diego, CA) with corncob bedding (Innovive). Mice were group-housed at 5 mice per cage approximately 1 wk prior to the experiment. For the experiment, mice were individually housed. Surviving mice then were group-housed (2 to 5 per cage) as available. Each cage was enriched with a 1-in.2 Nestlet (Ancare, Bellmore, NY). Mice were SPF for mouse parvovirus, minute virus of mice, mouse norovirus, mouse hepatitis virus, Sendai virus, lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus, polyomavirus, K virus, pneumonia, virus of mice, mouse adenovirus, epizootic diarrhea of infant mice (rotavirus), mouse encephalomyelitis virus, reovirus, ectromelia virus, Mycoplasma pulmonis, and endo- and ectoparasites. All mice were fed NIH31 diet (Harlan Teklad, Madison, WI) and offered reverse-osmosis–purified, acidified (pH 2.5 to 3.0) water ad libitum. The room was maintained at 20 to 21 °C, a relative humidity of 30% to 70%, 10 to 15 room air changes hourly, and on a 12:12-h photoperiod. The use of mice in this study was approved by the IACUC of the University of California, Los Angeles.

Test and control articles preparation and administration.

Test mice received a single, 0.2-mL IP injection of various concentrations of 1 of 3 types of rattlesnake venoms (Table 1). Lyophilized Western Diamondback (Crotalus atrox) venom was obtained from the Kentucky Reptile Zoo (lot no.1412; Slade, KY). Northern Pacific (C. oreganus oreganus) and Southern Pacific (C. oreganus helleri) venoms were harvested from snakes collected from various regions throughout northern and southern California and lyophilized by one of the authors (JGM). These venoms were selected in light of an ongoing study to evaluate the degree of cross-protection afforded by a canine rattlesnake vaccine. By using sterile water for injection, venom was reconstituted from lyophilized samples to establish various concentrations, as indicated in the previously described ‘up-and-down’ LD50 testing paradigm.8,13,14,17,42,44,46,48,62 According to the guidance from the up-and-down LD50 protocol, 6 mice were challenged with Western Diamondback venom, 6 mice were challenged with Northern Pacific venom, and 12 mice were challenged with Southern Pacific venom. Control mice (n = 6) received a single, 0.2-mL IP injection of 0.9% sterile saline. During the course of the LD50 assay, rectal temperatures from these venom-challenged and saline-control mice were measured as described in the following. Mice were not habituated to handling or rectal temperature recording prior to the procedures conducted in the study. Table 1 provides further details on dosing and disposition of mice.

Table 1.

Venom source, dose, and disposition of the 24 experimental and 6 control mice used in the study

| LD50 (mg/kg) | Dose |

|||||

| Venom source | no. of LD50 | mg/kg | Live | Dead | Total | |

| Western diamondback rattlesnake | 2.81 | 0.6 | 1.58 | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| 1.8 | 5.00 | 0 | 3 | 3 | ||

| Northern Pacific rattlesnake | 1.69 | 0.6 | 0.95 | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| 1.8 | 3.00 | 0 | 3 | 3 | ||

| Southern Pacific rattle snake | 1.50 | 0.3 | 0.47 | 4 | 0 | 4 |

| 1.0 | 1.50 | 3 | 2 | 5 | ||

| 3.1 | 4.70 | 0 | 3 | 3 | ||

| Total | 13 | 11 | 24 | |||

| Saline | — | — | — | 6 | 0 | 6 |

Temperature recording.

Temperature data were collected as part of routine monitoring for endpoints in a pilot study to determine the LD50 of 3 snake venoms to be used in a larger study to investigate the effectiveness of a canine rattlesnake vaccine. In the OECD Up-and-Down LD50 approach41,42 used, each animal was singly housed, closely supervised and no more than one animal dosed per day. As described by OECD Guidelines, temperatures were taken during the course of monitoring these mice for endpoints whereby animals were sequentially dosed on a logarithmic scale until specific stopping criteria were met and an LD50 value was calculated from an established algorithm. Core body temperature was recorded from mice manually restrained at the base of the tail once before venom or saline administration and then at various time points after administration. Core body temperature was measured by using a 1.5-cm thermistor probe (Physitemp, Clifton, NJ) inserted via the rectum into the mid- to distal colon. Temperatures were recorded after the probe reading stabilized, at approximately 5 s after insertion. Generally, temperatures were taken every 10 to 30 min for the first 2 h after injection and then every 1 to 2 h thereafter until 8 h after injection or euthanasia.

Euthanasia.

Mice were euthanized according to AVMA Guidelines32 by exposure to gradual-flow 100% CO2 gas, with flow maintained for at least 1 min after apparent respiratory arrest. Primary CO2 euthanasia was followed by cervical dislocation as a secondary measure. Nonsurviving mice were euthanized when they became moribund (head and body lying flat on cage bedding with little or no response to stimuli) or in respiratory distress (agonal breathing or intermittent gasping or both). Surviving mice were euthanized 1 wk after injection of the venom or saline.

Written and photographic documentation of clinical signs.

Subjective evaluations of clinical signs for all mice were recorded just before baseline temperature measurement and at other time points as needed. A series of photographs were taken of 3 mice to document progression of clinical signs subsequent to venom dosing.

Statistical analysis.

Two-tailed, unequal variance, Student t tests (a = 0.05, Microsoft Excel, Redmond, WA) were used to compare baseline body temperatures of venom-challenged mice and saline controls and body weights of surviving compared with nonsurviving envenomated mice. Graphs of core body temperature measured over time were generated for each of the 3 types of venom and saline controls. Logistic regression modeling controlling for effects of baseline temperature and venom type was accomplished to determine whether death was predicted by core body temperature (a = 0.05). Linear regression modeling was used to evaluate the interaction of time and survival in establishing the temperature that significantly predicted death at the earliest time point (a = 0.01; Stata Corporation, College Station, TX). Analysis was conducted for combined venom data as well as individual venom data. A more restrictive α value was chosen for the actual time and temperature values given the small number of mice available for individual analysis of 2 of the 3 venoms (n = 6). Combined data are reported for completeness, limited data size, and for the fact that the venoms tested were all from snakes of the same genus. Conceivably results could generally apply to other species of Crotalus or serve as a starting point for additional analysis.

Results

Student t test of baseline core body temperature and body weight.

Baseline temperatures did not differ significantly between venom-challenged mice and saline controls (0.18 < P < 0.79), and body weights did not differ significantly between surviving and nonsurviving mice (0.27 < P < 0.95).

Body temperature over time.

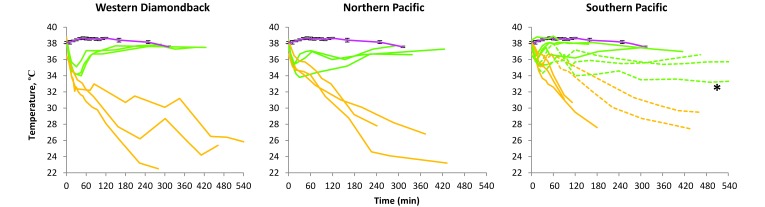

Figure 1 shows the core body temperature of mice over time for all 3 venoms and average temperature of 6 age- and sex-matched controls. All but one venom-challenged mouse showed a marked, immediate, dose-dependent drop in temperature of 2 to 6 °C at 15 to 45 min after venom administration. After the temperature drop, most surviving mice returned to at least near-baseline temperature by 2 to 4 h after injection. The lowest temperature of any surviving mouse was 33.2 °C. All mice with temperatures lower than 33.2 °C either died or were euthanized due to prolonged moribundity or marked respiratory distress.

Figure 1.

Core body temperature over time. For all venoms, green lines represent surviving mice, orange lines represent nonsurviving mice, and pink lines represent averaged temperatures of 6 saline-control mice. For Western Diamondback and Northern Pacific venoms, green lines also represent a dose of 0.6 LD50, and orange lines represent a dose of 1.8 LD50. For Southern Pacific venom, solid green lines represent a dose of 0.3 LD50, solid orange lines represent a dose of 3.1 LD50, and dashed lines (green or orange) represent an LD50 dose. The asterisk denotes the lowest body temperature of any surviving mouse of any venom type (33.2 °C). Error bars on the saline-control (pink) line represent the SEM.

Logistic and linear regression analyses.

Logistic regression data of combined data as well as for each separate venom type are compiled in Table 2. For combined data, neither baseline temperature nor venom type nor concentration was significant predictors of survival (P = 0.504, P = 0.198, and P = 0.602, respectively). Logistic regression analysis of combined data showed significance (P < 0.0001) for predicting death from core body temperature.

Table 2.

Logistic regression modeling predicting death from core body temperature

| All Venoms | Western Diamondback | Northern Pacific | Southern Pacific | |

| n | 24 | 6 | 6 | 12 |

| no. of observations | 268 | 76 | 54 | 138 |

| Probability> F value | <0.00001 | 0.0001 | 0.0314 | 0.0057 |

| Pseudo R-squared | 0.3966 | 0.6570 | 0.4577 | 0.2382 |

| P (predict death from temperature) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.009 | 0.001 |

| (1.74–3.59) | (1.85–6.46) | (1.36–9.00) | (1.30–2.96) | |

| P (effect of baseline temperature) | 0.504 | 0.378 | 0.692 | 0.902 |

| (0.41–6.04) | (0.21–63.35) | (0.10–33.49) | (0.10–7.80) | |

| P (effect of venom type) | 0.602 | not applicable | not applicable | not applicable |

| (0.211–2.46) |

Bolded values are significant. Values in parentheses are 95% confidence intervals.

In addition, venoms were analyzed separately. Baseline temperature was not a significant predictor of mortality for any of the venoms, although confidence intervals were wide for the Western Diamondback and Northern Pacific venoms, likely because of the small sample size of these groups (n = 6). Likewise, concentration-associated effects specific for each could not be evaluated because only 2 concentrations were used for Western Diamondback and Northern Pacific venoms and 3 concentrations for Southern Pacific venom. Separate analysis of venoms showed that death could be predicted from core body temperature for all 3 venoms.

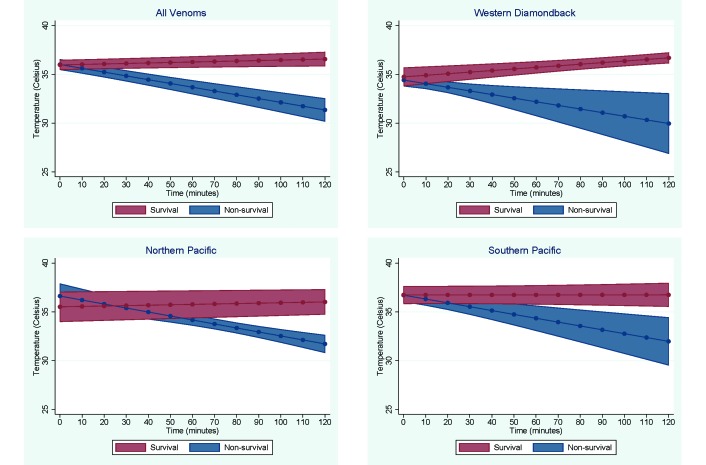

Linear regression modeling of the interaction of time and survival was used to estimate the temperature that predicts death as an outcome at the earliest significant time point (a = 0.01, Figure 2). These temperature and times were 35 °C at 25 min for combined venoms, 33.5 °C at 25 min for Western Diamondback, 33.3 °C at 60 min for Northern Pacific, and 34.3 °C at 80 min for Southern Pacific. Baseline temperature was not a significant predictor of time or temperature in this analysis (P = 0.261). In contrast, venom type significantly (P = 0.006) influenced time and temperature values.

Figure 2.

Graphs of linear regression models predicting temperature from the interaction of time and survival. Graphs show linear regression of temperatures over time for surviving and nonsurviving mice for each venom and combined venoms.

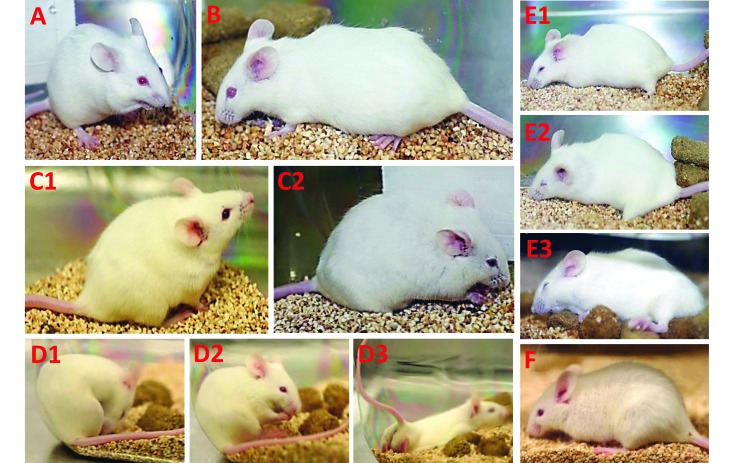

Written and photographic documentation of clinical signs.

Representative documentation from 392 written observations and 453 photos are presented in Figure 3. Subjectively, clinical signs were consistent among mice and occurred in a dose-dependent manner. In general, increased severity and more rapid decline in clinical signs were associated with lower temperatures whereas improved disposition was associated with normal or near-normal temperatures.

Figure 3.

Clinical signs, photographs, and temperatures of select mice. A. Normal mouse. Temperature before venom injection, 37.3 °C.B. Nonsurviving mouse:dose, 3LD50;temperature at 15 min after injection, 35.6 °C. Eyes open, intermittent sniffing, minimal voluntary movement, cervical ventroflexion, intermittent mild skin and body twitch, moderate dyspnea (decreased rate, increased effort), short bout of mouth and abdominal grooming. C. Surviving and nonsurviving mice at 30 min after injection. C1. Surviving mouse; LD50 dose; temperature, 35.9 °C. C2. Nonsurviving mouse: dose, 3LD50; temperature, 33.7 °C. Marked piloerection present in both mice; dyspnea (decreased rate, increased effort) in both mice, with C1 (mild to moderate) less dyspneic than C2 (severe). C2 shows eye squint or grimace, mouth grooming, cervical ventroflexion, and pinned back ears. D. Examples of typical intermittent behavior after venom injection in a surviving mouse, LD50 dose. Immediately through 2 h after injection, D1 and D2 show abdominal and mouth grooming. D3 shows abdominal pressing, body stretching, and tail elevation,which we considered to be signs of acute abdominal pain and discomfort, similar to the behavior in the standardized writhing test.24,25,49,52 E. Progression of clinical signs in a high-dose (3LD50), nonsurviving mouse. E1 is at 1 h after injection; temperature, 32.6 °C. Mouse is sternal with body and nose touching floor, eyes nearly shut, no voluntary movement but weakly responsive to stimuli (moderate resistance when handled), extremities pale, significant piloerection, marked abdominal respiratory effort. E2 is at 2 h after injection;temperature, 29.5 °C. Mouse is sternal with body and head flat on cage floor, eyes shut, pale extremities, no voluntary movement but responsive to stimuli (mild to moderate resistance when handled but tires easily), slow shallow breathing at rest, open-mouth breathing. E3 is at 3 h after injection; temperature, 27.6 °C. Mouse is sternal with body and head lying flat on wet food pile (many mice preferred to lie on or near wet food provided on the cage floor), very weakly responsive to stimuli, moderate piloerection, pale extremities, slow shallow breathing, ears pinned back, open-mouth breathing, intermittent gasping; mouse euthanized. F. Surviving mouse: LD50 dose; 6 h after injection; temperature, 35.4 °C. At several hours after injection, many mice exhibited this characteristic presentation, embodied by minimal to no voluntary movement, marked piloerection, cervical ventroflexion, mouth slightly open, mildly squinted eyes, and pinned-back ears.

Discussion

The principle of the 3Rs calls for researchers to refine techniques to minimize or eliminate animal pain and suffering in experiments. Administering high doses of a toxin such as snake venom generally results in clear signs of impending death, such as agonal breathing, myoclonus, writhing, and lateral recumbency with no response to external stimuli. In such instances, determining endpoints based on clinical assessment are straightforward. However, in the case of intermediary doses, clinical signs alone may not be sufficiently reliable to clearly predict whether an animal will succumb, and animals may experience prolonged periods of moribundity before death. In that vein, we attempted to identify an objective, early endpoint based on core body temperature to assist in predicting mortality of mice in an LD50 study of 3 snake venoms.

Our results showed core body temperature can be useful as an adjunct to identifying objective endpoints and can be used as a signal for preemptive euthanasia in LD50 studies in mice. Specifically, we found that core body temperature as measured with a thermistor probe significantly predicted death in mice regardless of venom type or baseline temperature. In contrast, the specific temperature at which death is reliably predicted at the earliest possible time point differed between venoms. Analysis of snake venom reveals it to be a complex milieu of peptides and proteins, and venom from related species and subspecies can differ markedly in composition.2,9,35 It is therefore not surprising to see differences between venoms in the more specific analysis of the actual temperatures that are predictive of survival and, for the sake of completeness, we have reported data for both all venoms combined and each toxin individually. Overall, in the present study, linear regression modeling showed that temperatures at or below 33.3 °C at 80 min were highly predictive of death for all venoms tested, and no mouse survived that had a temperature at or below 33.2 °C. Furthermore, we suggest that this assessment could be extended to other survival assays (such as Kaplan–Meier survival analysis) in which it may be critical to assess the duration of survival in addition to mortality. Formulating a more objective endpoint that is based in part on changes in core body temperature over time may help to reduce error due to subjective evaluation of clinical signs (moribundity) for euthanasia and increase the ease with which the precise time of death in multiple animals can be monitored simultaneously.

We also present subjective clinical observations and photography to catalog the clinical signs and trends than might be expected in venom toxicity studies. To our knowledge, such assessment has not been published and may be a useful reference to those unfamiliar with these studies. In general, clinical signs mirrored temperature fluctuations. Surviving mice demonstrated a sharp deterioration of clinical signs during the first 30 to 45 min after venom injection, followed by complete or nearly complete recovery within 2 to 3 h. Nonsurviving mice had a similar, immediate deterioration in clinical signs. However, depending on the dose or venom type, some nonsurviving mice demonstrated a brief (15 to 20 min) period during which clinical signs slightly improved or remained stable. Thereafter, nonsurviving animals generally underwent a gradual decline until death or euthanasia. Specific clinical signs were consistent among animals and are summarized in Figure 3. We propose that a more objective clinical scoring metric could be applied or developed, but this goal is beyond the scope of this study.

We acknowledge several potential confounders to our study. One possible source of variability is the use of rectal thermometry compared with implantable telemetry devices, the only available technology that allows for real-time, highly accurate recording of core body temperature without handling the mice or disturbing their housing. Inherent limitations to rectal thermometry include inadvertent hyperthermia due to handling stress; an inability to routinely take continuous, real-time temperatures; and the risk of rectal or colonic trauma.5,10,45 In our study, the mice likely had stress hyperthermia due to handling, given that baseline temperatures were 2 to 3° higher than typically expected (as measured by telemetry) at the time of day measured. In contrast, advantages to using rectal thermometry include a realistic and cost-effective approach to large-scale studies and no requirement for an invasive and time-consuming surgical procedure. Furthermore, in the case of LD50 studies, using a telemetric device would not altogether eliminate handling hyperthermia, because mice must be restrained for weight assessment and injection of venom. Restraining a mouse by the tail can lead to a significant rise (approximately 1 °C as measured by telemetry) in core temperature that lasts for about 1 h,34 which is well into the timeframe of a venom LD50 study. Implantable subcutaneous microchip transponders and infrared thermometry could be viable, less expensive, and less invasive alternatives to rectal thermometry. However, these technologies have their own unique drawbacks, such as necessitating animal restraint in some cases, disturbing housing to make measurements, and reporting of surface compared with true core temperature (although comparing the rate of the temperature drop with absolute core body temperature is plausible). Nevertheless, additional evaluation is required before these devices are used in LD50 studies.

In addition, recording core body temperature in a vivarium setting introduces many potential variables relative to those of absolute temperature measurements. In our study, mice had to be transferred between a laminar flow hood and individually ventilated home cages. This process likely added minor variability in ambient temperature in the hood compared with the cage. Theoretically, a shift in ambient temperature can alter the dose–response and hypothermic efficacy of the toxins. In fact, it has long been recognized that mice (including those in this study) typically are housed and manipulated at suboptimal ambient temperatures.12,20,23 The typical vivarium ambient temperature of approximately 22 °C is significantly below the lower critical ambient temperature of the thermoneutral zone of mice (30 to 31 °C), and ambient temperature has been shown to contribute to variability in experimental outcomes.2,18,59 Nevertheless, in our case, the cooler ambient temperatures may be desirable from a humane perspective, because warmer temperatures could slow the rate of core temperature cooling and prolong pain and suffering. In addition, animal temperatures can fluctuate according to circadian rhythm, and this effect should be accounted for when reporting temperature measurements.21,33,56 Lastly, all of the mice used in the current study were female, in accordance with OECD recommendations for toxicity testing.14 These guidelines are based on previous work that has shown that female rodents tend to be more sensitive to toxin exposure than are male rodents. Because the primary goal of the LD50 study was to determine accurate and widely accepted estimations of LD50 for the venoms, we chose to be consistent with the OECD guidelines and use only female mice. It seems reasonable to assume that male mice would respond similarly to venom intoxication as would female mice, but we point out this potential confounder to the study. We were unable to find any literature that evaluated differences between male and female responses to snake venom.

We took several steps to control for these confounders. First, logistic regression analysis was designed to control for baseline temperature, and baseline temperature was not a significant factor influencing death of mice in our model. Second, to minimize potential differences due to circadian rhythm, we conducted experiments within the light (somnolent) phase for all mice. Third, to control for variability between groups, we handled and housed all mice in the same way to include equal amounts of time in the hood and cages and the same pattern of weighing and injection. Finally, we also present data of saline-control mice that were handled and housed in the same manner as were test animals.

Another potential confounder to the study is we did not allow mice to spontaneously die in most cases. Rather, we euthanized mice according to a subjective clinical assessment of moribundity as recommended in the OECD guidelines,41,42 adopted by the Environmental Protection Agency,17 and allowable under our approved animal-use protocol. Although every effort was made to accurately identify mice that would not recover, some animals conceivably could have recovered after enduring a substantial period of moribundity and registering core body temperatures less than 33.2 °C.

From these data, we suggest the following prudent approach to determining an objective endpoint in murine LD50 studies of viperid snake venom. During the first 30 min after the administration of venom, mice are monitored according to clinical signs. Mice given high doses and displaying obvious terminal clinical signs, such as agonal breathing, myoclonus, and lateral or sternal recumbency with no response to external stimuli, are euthanized. Measurement of core body temperatures of obtunded or potentially moribund animals begins at 30 min after injection. Clinically normal animals need not be measured. Mice with equivocal clinical signs and temperatures at or below 35.0 °C are monitored for clinical signs every 15 min and continue to have temperatures taken every 15 to 30 min until clinical signs improve and temperature increases to 36 °C or higher. If the temperature drops below 33.0 °C with continued moribundity or the mouse displays obvious terminal clinical signs (as described earlier), the animal is euthanized.

Why such temperature changes occur in rodents after toxin exposure is not well understood. Some studies have examined this phenomenon.4,6,7,15,19,28,38,47 However, speculation regarding the physiology behind the change in core body temperature as it specifically relates to venom is beyond the scope of this report.

In conclusion, our data suggest that core body temperature can be a useful adjunct to identifying objective endpoints in snake venom LD50 studies. Because venom type influenced the temperature that predicted death at the earliest significant time point and because of the small sample size for 2 of the venoms analyzed, future studies may involve assessing the technique as it specifically applies to other types of snake venoms. Indeed, research has shown that the specific temperature that is predictive of death is unique to a given study, and this finding likely extends to studies evaluating the effects of venom.11,22,30,31,36,50,54,60 Additional research may be valuable to verify the approach used in other types of survival studies (such as Kaplan–Meier analysis, which takes into account the length of survival) to provide a more objective method of determining study endpoints.

Acknowledgments

We thank the UCLA Institute for Digital Research and Education Academic Technology Services for providing assistance with statistical analysis.

References

- 1.Aird SD. 1985. A quantitative assessment of variation in venom constituents within and between three nominal rattlesnake subspecies. Toxicon 23:1000–1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altman PL, Katz DD. 1966. Environmental biology. Bethesda (MD): Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson WH, Brodersen R. 1949. Hypothermia in the mouse as a bio-assay of endotoxin protection factor in impure penicillin. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med 70:322–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Assi AA, Nasser H. 1999. An in vitro and in vivo study of some biological and biochemical effects of Sistrurus Malarius Barbouri venom. Toxicology 137:81–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bae DD, Brown PL, Kiyatkin EA. 2007. Procedure of rectal temperature measurement affects brain, muscle, skin, and body temperatures and modulates the effects of intravenous cocaine. Brain Res 1154:61–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barenholz-Paniry V, Ishay JS, Freeman S, Sohmer H. 1990. Evoked potential changes in cats following injection of an extract from the venom sac of the oriental hornet (Vespa orientalis). Toxicon 28:1317–1324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Benton AW, Heckman RA, Morse RA. 1966. Environmental effects of venom toxicity in rodents. J Appl Physiol 21:1228–1230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bruce RD. 1985. An up-and-down procedure for acute toxicity testing. Fundam Appl Toxicol 5:151–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chippaux JP, Williams V, White J. 1991. Snake venom variability: methods of study, results and interpretation. Toxicon 29:1279–1303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clement JG. 1993. Experimentally induced mortality following repeated measurement of rectal temperature in mice. Lab Anim Sci 43:381–382. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clement JG, Mills P, Brockway B. 1989. Use of telemetry to record body temperature and activity in mice. J Pharmacol Methods 21:129–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.David JM, Chatziioannou AF, Taschereau R, Wang H, Stout DB. 2013. The hidden cost of housing practices: using noninvasive imaging to quantify the metabolic demands of chronic cold stress of laboratory mice. Comp Med 63:386–391. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dixon WJ. 1965. The up-and-down method for small samples. J Am Stat Assoc 60:967–978. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dixon WJ, Massey FJ. 1983. Introduction to statistical analysis. New York (NY): McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dutta AS, Chaudhuri AK. 1991. Neuropharmacological studies on the venom of Vipera russelli. Indian J Exp Biol 29:937–942. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Efron B. 1988. Logistic regression, survival analysis, and the Kaplan–Meier curve. J Am Stat Assoc 83:414–425. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Environmental Protection Agency . 2002. Health Effects Test Guidelines OPPTS 870.1100 Acute Oral Toxicity. Washington DC. US Government Printing Office. [Cited 12 November 2014]. Available at: http://ntp.niehs.nih.gov/iccvam/suppdocs/feddocs/epa/epa_870r_1100.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gordon CJ. 1993. Temperature regulation in laboratory rodents. Cambridge (England): Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gordon CJ. 2005. Temperature and toxicity. Boca Raton (FL): CRC Press. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gordon CJ. 2005. Temperature and toxicology: an integrative, comparative, and environmental approach. Boca Raton (FL): Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gordon CJ. 2012. Thermal physiology of laboratory mice: defining thermoneutrality. J Therm Biol 37:654–685. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gordon CJ, Fogelson L, Highfill JW. 1990. Hypothermia and hypometabolism: sensitive indices of whole-body toxicity following exposure to metallic salts in the mouse. J Toxicol Environ Health 29:185–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gordon CJ, Spencer PJ, Hotchkiss J, Miller DB, Hinderliter PM, Pauluhn J. 2008. Thermoregulation and its influence on toxicity assessment. Toxicology 244:87–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gyires K, Torma Z. 1984. The use of the writhing test in mice for screening different types of analgesics. Arch Int Pharmacodyn Ther 267:131–140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harada T, Takahashi H, Kaya H, Inoki R. 1979. A test for analgesics as an indicator of locomotor activity in writhing mice. Arch Int Pharmacodyn Ther 242:273–284. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hendriksen CF. 2009. Replacement, reduction and refinement alternatives to animal use in vaccine potency measurement. Expert Rev Vaccines 8:313–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Institute for Laboratory Animal Research 2011. Guide for the care and use of laboratory animals. Washington (DC): National Academies Press. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ishay JS, Shemesh E, Lilling I. 1983. Hypothermia induced in mice by injection of venom sac extract of hornets (Vespa orientalis, vespinae: hymenoptera). Experientia 39:53–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jennings M, Morton DB, Charton E, Cooper J, Hendriksen C, Martin S, Pearce MC, Price S, Redhead K, Reed N, Simmons H, Spencer S, Willingale H. 2010. Application of the three Rs to challenge assays used in vaccine testing: tenth report of the BVAAWF/FRAME/RSPCA/UFAW Joint Working Group on Refinement. Biologicals 38:684–695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kort WJ, Hekking-Weijma JM, TenKate MT, Sorm V, VanStrik R. 1998. A microchip implant system as a method to determine body temperature of terminally ill rats and mice. Lab Anim 32:260–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Krarup A, Chattopadhyay P, Bhattacharjee AK, Burge JR, Ruble GR. 1999. Evaluation of surrogate markers of impending death in the galactosamine-sensitized murine model of bacterial endotoxemia. Lab Anim Sci 49:545–550. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Leary S, Underwood W, Anthony R, Cartner S, Corey D, Grandin T, Greenacre CB, Gwaltney-Bran S, McCrackin MA, Meyer R, Miller D, Shearer J, Yanong R. 2013 [Internet]. AVMA guidelines for the euthanasia of animals: 2013 ed. [Cited 12 November 2014]. Available at: http://works.bepress.com/cheryl_greenacre/14. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Martin SS, Bakken RR, Lind CM, Reed DS, Price JL, Koeller CA, Parker MD, Hart MK, Fine DL. 2009. Telemetric analysis to detect febrile responses in mice following vaccination with a live-attenuated virus vaccine. Vaccine 27:6814–6823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Meijer MK, Spruijt BM, van Zutphen LF, Baumans V. 2006. Effect of restraint and injection methods on heart rate and body temperature in mice. Lab Anim 40:382–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Minton SA, Weinstein SA. 1986. Geographic and ontogenic variation in venom of the western diamondback rattlesnake (Crotalus atrox). Toxicon 24:71–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mohler FS, Gordon CJ. 1991. Hypothermic effects of a homologous series of short-chain alcohols in rats. J Toxicol Environ Health 32:129–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Morton DB. 2000. A systematic approach for establishing humane endpoints. ILAR J 41:80–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Murthy KR, Zare MA. 1998. Effect of Indian red scorpion (Mesobuthus tamulus concanesis, Pocock) venom on thyroxine and triiodothyronine in experimental acute myocarditis and its reversal by species specific antivenom. Indian J Exp Biol 36:16–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nemzek JA, Xiao HY, Minard AE, Bolgos GL, Remick DG. 2004. Humane endpoints in shock research. Shock 21:17–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Olfert ED, Godson DL. 2000. Humane endpoints for infectious disease animal models. ILAR J 41:99–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development 2000. Guidance document on the recognition, assessment, and use of clinical signs as humane endpoints for experimental animals used in safety evaluation.Joint Meeting of the Chemicals Commitee and the Working Party on Chemicals, Pesticides and Biotechnology. Paris (France): OECD Environmental Health and Safety Publications. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development 2008. OECD guidelines for testing of chemicals. Paris (France): Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ray MA, Johnston NA, Verhulst S, Trammell RA, Toth LA. 2010. Identification of markers for imminent death in mice used in longevity and aging research. J Am Assoc Lab Anim Sci 49:282–288. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rispin A, Farrar D, Margosches E, Gupta K, Stitzel K, Carr G, Greene M, Meyer W, McCall D. 2002. Alternative methods for the median lethal dose (LD(50)) test: the up-and-down procedure for acute oral toxicity. ILAR J 43:233–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Romanovsky AA, Kulchitsky VA, Simons CT, Sugimoto N. 1998. Methodology of fever research: why are polyphasic fevers often thought to be biphasic? Am J Physiol 275:R332–R338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rowe AH, Rowe MP. 2008. Physiological resistance of grasshopper mice (Onychomys spp.) to Arizona bark scorpion (Centruroides exilicauda) venom. Toxicon 52:597–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rubin Y, Duvdevani P, Ishay JS. 1993. Cardiovascular haemodynamics of oriental hornet venom sac extract. Pharmacol Toxicol 72:268–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sevcik C. 1987. LD50 determination: objections to the method of Beccari as modified by Molinengo. Toxicon 25:779–783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Singh PP, Junnarkar AY, Varma RK. 1987. A test for analgesics: incoordination in writhing mice. Methods Find Exp Clin Pharmacol 9:9–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Soothill JS, Morton DB, Ahmad A. 1992. The HID50 (hypothermia-inducing dose 50): an alternative to the LD50 for measurement of bacterial virulence. Int J Exp Pathol 73:95–98. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stiles BG, Campbell YG, Castle RM, Grove SA. 1999. Correlation of temperature and toxicity in murine studies of staphylococcal enterotoxins and toxic shock syndrome toxin 1. Infect Immun 67:1521–1525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Team Fiction. [Internet]. Writhing test. [Cited 12 November 2014]. Available at: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aSYxNF7h2ug.

- 53.Toth LA, Hughes LF. 2006. Sleep and temperature responses of inbred mice with Candida albicans-induced pyelonephritis. Comp Med 56:252–261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Toth LA, Rehg JE, Webster RG. 1995. Strain differences in sleep and other pathophysiological sequelae of influenza virus infection in naive and immunized mice. J Neuroimmunol 58:89–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Trammell RA, Toth LA. 2011. Markers for predicting death as an outcome for mice used in infectious disease research. Comp Med 61:492–498. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.van Bogaert MJ, Groenink L, Oosting RS, Westphal KG, van der Gugten J, Olivier B. 2006. Mouse strain differences in autonomic responses to stress. Genes Brain Behav 5:139–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Vlach KD, Boles JW, Stiles BG. 2000. Telemetric evaluation of body temperature and physical activity as predictors of mortality in a murine model of staphylococcal enterotoxic shock. Comp Med 50:160–166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Warn PA, Brampton MW, Sharp A, Morrissey G, Steel N, Denning DW, Priest T. 2003. Infrared body temperature measurement of mice as an early predictor of death in experimental fungal infections. Lab Anim 37:126–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Watkinson WP, Gordon CJ. 1993. Caveats regarding the use of the laboratory rat as a model for acute toxicological studies: modulation of the toxic response via physiological and behavioral mechanisms. Toxicology 81:15–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wong JP, Saravolac EG, Clement JG, Nagata LP. 1997. Development of a murine hypothermia model for study of respiratory tract influenza virus infection. Lab Anim Sci 47:143–147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.World Health Organization . 2010. WHO Guidelines for the Production Control and Regulation of Snake Venom Immunoglobulins. 59th Meeting of the WHO Expert Committee on Biological Standardization, 17 Oct 2008. Geneva (Switzerland). WHO Press, World Health Organization. [Cited 13 November 2014]. Available at: http://www.who.int/bloodproducts/snake_antivenoms/snakeantivenomguideline.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yam J, Reer PJ, Bruce RD. 1991. Comparison of the up-and-down method and the fixed-dose procedure for acute oral toxicity testing. Food Chem Toxicol 29:259–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]