Abstract

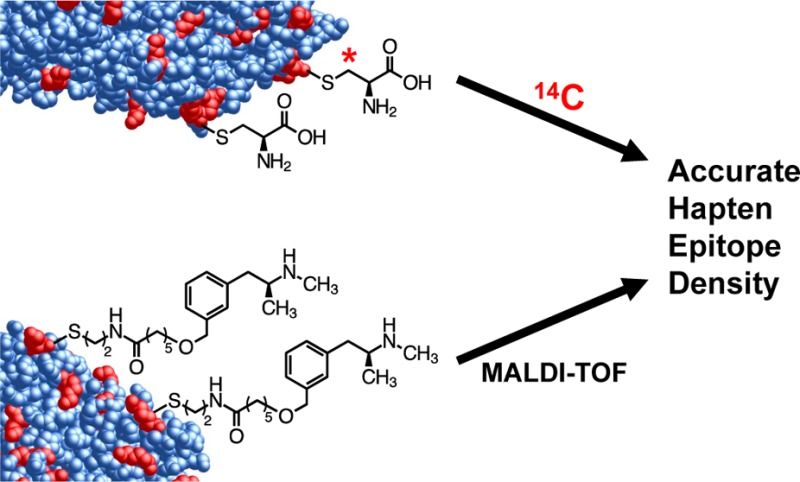

Control of small molecule hapten epitope densities on antigenic carrier proteins is essential for development and testing of optimal conditions for vaccines. Yet, accurate determination of epitope density can be extremely difficult to accomplish, especially with the use of small haptens, large molecular weight carrier proteins, and limited amounts of protein. Here we report a simple radiometric method that uses 14C-labeled cystine to measure hapten epitope densities during sulfhydryl conjugation of haptens to maleimide activated carrier proteins. The method was developed using a (+)-methamphetamine (METH)-like hapten with a sulfhydryl terminus, and two prototype maleimide activated carrier proteins, bovine serum albumin (BSA) and immunocyanin monomers of keyhole limpet hemocyanin. The method was validated by immunochemical analysis of the hapten–BSA conjugates, and least-squares linear regression analysis of epitope density values determined by the new radiometric method versus values determined by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization mass spectrometry. Results showed that radiometric epitope density values correlated extremely well with the mass spectrometrically derived values (r2 = 0.98, y = 0.98x + 0.91). This convenient and simple method could be useful during several stages of vaccine development including the optimization and monitoring of conditions for hapten–protein conjugations, and choosing the most effective epitope densities for conjugate vaccines.

To generate high affinity antibodies against small molecular weight chemicals and peptides (e.g., <1000 Da molecular weight), multiple copies of a hapten must be covalently attached to a suitable antigenic carrier protein to form a vaccine. The degree of haptenation (or epitope density) can influence both the affinity and titer of the resulting antibody immune response.1 However, the accurate measurement and optimization of epitope density is a critical and sometimes underappreciated aspect of vaccine development.

Two commonly used approaches for hapten–protein conjugation reactions are formation of a carboxamide2 bond between the hapten and a reactive terminal amino group of the carrier protein, or a thioether bond between the hapten and a maleimide activated protein.3,4 While the carboxamide chemistry is straightforward,2 it is often difficult to achieve reproducible high levels of epitope densities on proteins (e.g., >10 per bovine serum albumin [BSA] molecule),5 whereas with sulfhydryl chemistry it is relatively easy to achieve high epitope densities with maleimide activated proteins.4

In the process of developing an anti-methamphetamine (METH) vaccine, we realized the critical need to develop an inexpensive, rapid method for accurate quantitation of the epitope density on both small and large proteins. The colorimetric method of Ellman6 is perhaps the most often used procedure for determining the number of sulfhydryl groups available for conjugation. However, the technique does not work well with all hapten–protein combinations or with very small-scale conjugation reactions where the amount of protein or antigenic carrier is a limiting factor. Chemical modification of the carrier proteins to allow direct conjugation of more haptens also adds to the complexity of the analysis. For smaller, commonly used carrier proteins (<100 kDa) such as ovalbumin, BSA, and thyroglobulin (TG), matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF) is an accurate and reliable analytical method.5,7−9

Characterization of hapten–protein conjugates is especially difficult to achieve with large molecular weight proteins (e.g., >100 kDa) and very small haptens (e.g., <300 Da). For these larger carrier proteins and dimers (like ICKLH) or multimers, accurate determination of mass can sometimes be best accomplished with radiolabeled haptens or with very advanced mass spectrometry systems. Both techniques are costly and not feasible for most laboratories.

We report here the utility and validation of a simple radiochemical method for accurate quantitation of sulfhydryl hapten conjugations to maleimide activated proteins. The method uses 14C-cystine and the reduced form, 14C-cysteine (14C-Cys), as a tracer and maleimide activated carrier protein. To determine the feasibility of this analytical method we conjugated the METH-hapten SSMO9-METH [(S)-N-(2-(mercaptoethyl)-6-(3-(2-(methylamino)propyl)phenoxy)hexanamide] to BSA (Figure 1) and used MALDI-TOF as a reference method to validate our results. We have previously published the synthesis of HSMO9,4 and will publish the synthesis of SSMO9-METH in a future publication.

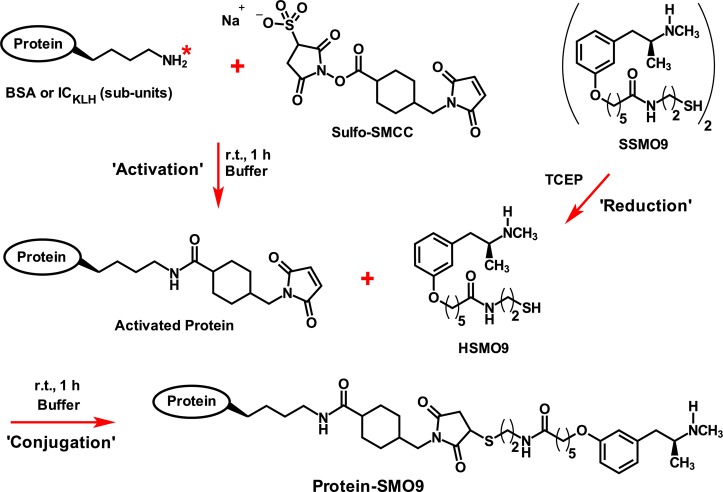

Figure 1.

METH conjugate vaccine synthesis overview. The available lysine groups on a protein (BSA or ICKLH) were “activated” with the cross-linker sulfo-SMCC in preparation for “conjugation”; for simplicity, only a single lysine terminal group is shown (*). Just prior to the conjugation step, TCEP is used as a reducing agent for the conversion of SSMO9 dimer to HSMO9 monomer. Starting with the dimer allows for just in time reduction of the highly reactive HSMO9 hapten. In the final step of the reaction, SMO9 is “conjugated” to the activated BSA or ICKLH to form the METH-conjugate vaccine (labeled Protein-SMO9). After conjugation was complete, any unreacted maleimide groups of the BSA-SMO9 or ICKLH-SMO9 vaccine were blocked or end-capped by the addition of a 4-fold excess of cysteine. This step was a precaution to prevent any potential chemical reactions of the vaccine with proteins in vivo.

We also tested the method for use in the development of anti-METH vaccine using maleimide activated Immunocyanin (ICKLH; Biosyn Corp., Carlsbad, CA) as the carrier protein (Figure 1). ICKLH is a large molecular weight protein derived from the native Keyhole limpet hemocyanin (KLH; 8000 to 32 000 kDa), which consists of two stable subunit monomers with masses of ∼360 and ∼390 kDa, with abundant lysine residues for hapten linkage.4,5,10,11 Relative to native KLH, ICKLH is a more uniform antigenic carrier that is used in human vaccine clinical trials.12,13 This ICKLH-SMO9 conjugate vaccine is in preclinical development for the potential treatment of METH addiction.4

SSMO9 (Figure 1) is a new dimeric precursor of the METH-like hapten HSMO9 (hereafter referred to as the deprotonated SMO9), used for conjugation to ICKLH,4 which is simpler to synthesize, does not require protection of the single SMO9 sulfhydryl group from degradation, and does not use mercuric acetate in the synthesis process. The elimination of possible mercury carryover in the reaction is a critical improvement for a potential human vaccine. In addition, the S–S dimer form of haptens can stabilize the labile SH group and protect it from unwanted side reactions during synthesis.14 This can also improve the storage stability and quality of sulfhydryl-containing haptens. The reduced form of this hapten, SMO9, was directly conjugated to the maleimide activated BSA or ICKLH (Figure 1). The activation, reduction, and conjugation reactions for the radiometric and MALDI-TOF analysis experiments as well as for vaccine production were performed similarly and are described in Supporting Information.

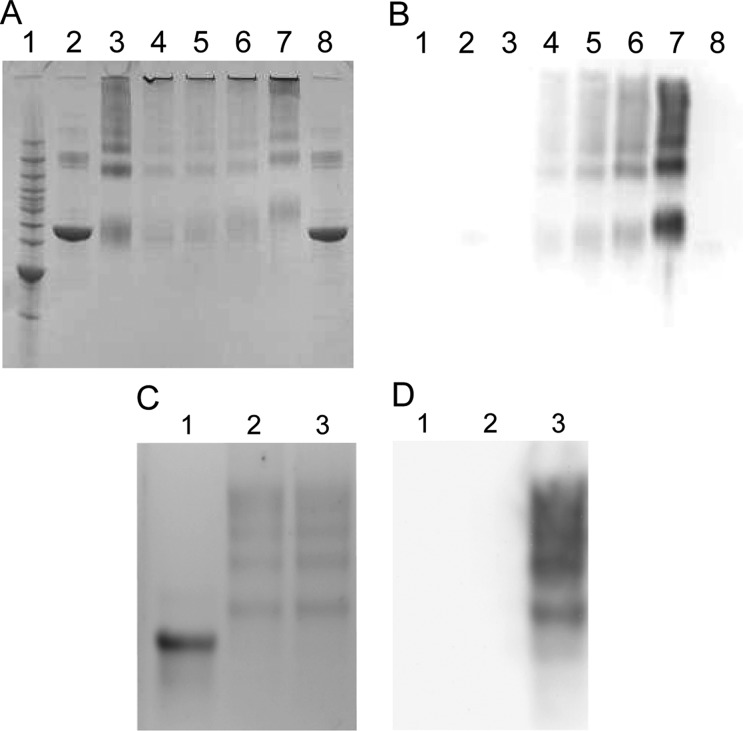

To characterize the maleimide activated proteins and confirm the conjugation of SMO9 to the activated protein, SMO9–activated BSA conjugates were evaluated by SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis (Figure 2A and B). SMO9–activated ICKLH conjugates were evaluated using an agarose gel system and Western blot (Figure 2C and D). Activation of both BSA (Figure 2A, lane 3) and ICKLH (Figure 2C, lane 2) resulted in the formation of large molecular weight protein bands that did not react with an anti-METH antibody upon Western blot analysis (Figure 2B, lane 3 and Figure 2D, lane 2), but did react with the anti-METH antibody when the activated proteins were conjugated with SMO9 (Figure 2B, lanes 4–7 and Figure 2D, lane 3). This confirmed the coupling of the SMO9 hapten to the various forms of the activated proteins.

Figure 2.

(A) SDS-PAGE showing BSA molecular weight increases as the ratio of SMO9 to BSA is increased. Lanes: (1) molecular weight markers; (2) unconjugated BSA at 1 mg/mL; (3) sulfo-SMCC activated BSA (1 mg/mL), (4–7) BSA:SMO9 ratios of 1:10, 1:15, 1:20, and 1:30, (8) unconjugated BSA at 1 mg/mL. (B) Western blot analysis of same lane order as 3A probed with anti-METH mAb4G9. Note the increase in image signal strength and in apparent molecular size as the ratio of BSA:SMO9 increases. (C) APE GEL analysis of ICKLH-SMO9 conjugates stained with Coomassie. Lanes: (1) unconjugated ICKLH; (2) maleimide activated ICKLH; (3) ICKLH:SMO9. (D) Western blot of same gel order as in C, probed with anti-METH mAb4G9.2

For the 14C-Cys radiometric analyses of BSA–hapten conjugations, we determined both the incorporation of 14C-Cys tracers in the presence of large amounts of SMO9 (SMO9-equivalents, a competitive reaction for protein conjugation sites), and the incorporation of the 14C-Cys tracers in the presence of unlabeled cysteine (reported as 14C-Cys-equivalents, a noncompetitive reaction). We hypothesized that parallel measurement of the incorporation of 14C-Cys-equivalents, conducted at the same time as SMO9 protein conjugation reactions, would be the most accurate predictor of SMO9-protein epitope density. It was not clear if 14C-Cys in the presence of large amounts of SMO9 would accurately predict epitope density, since the two molecules differed in structure and chemical properties. This could result in different rates for the completion of forming covalent bounds with the protein, and thereby produce an over or under estimation of the true SMO9 epitope density on the proteins.

To test this hypothesis we conducted three parallel conjugation reactions: (1) SMO9 with a 14C-Cys tracer, (2) unlabeled cysteine with a 14C-Cys tracer, and (3) SMO9 alone with a range of BSA:hapten ratios (1:10, 1:15, 1:20, and 1:30). The hapten epitope density of SMO9 alone (3) was determined by MALDI-TOF analysis, as described previously.4 This was deemed our reference method for assay validation. The samples containing 14C-Cys were quantitated by liquid scintillation spectrophotometry. Although the amount of the tracer radioligand bound to the protein was relatively low, we were able to use this incorporation of 14C-Cys as a relative measure of the amount of conjugation of unlabeled cysteine or SMO9.

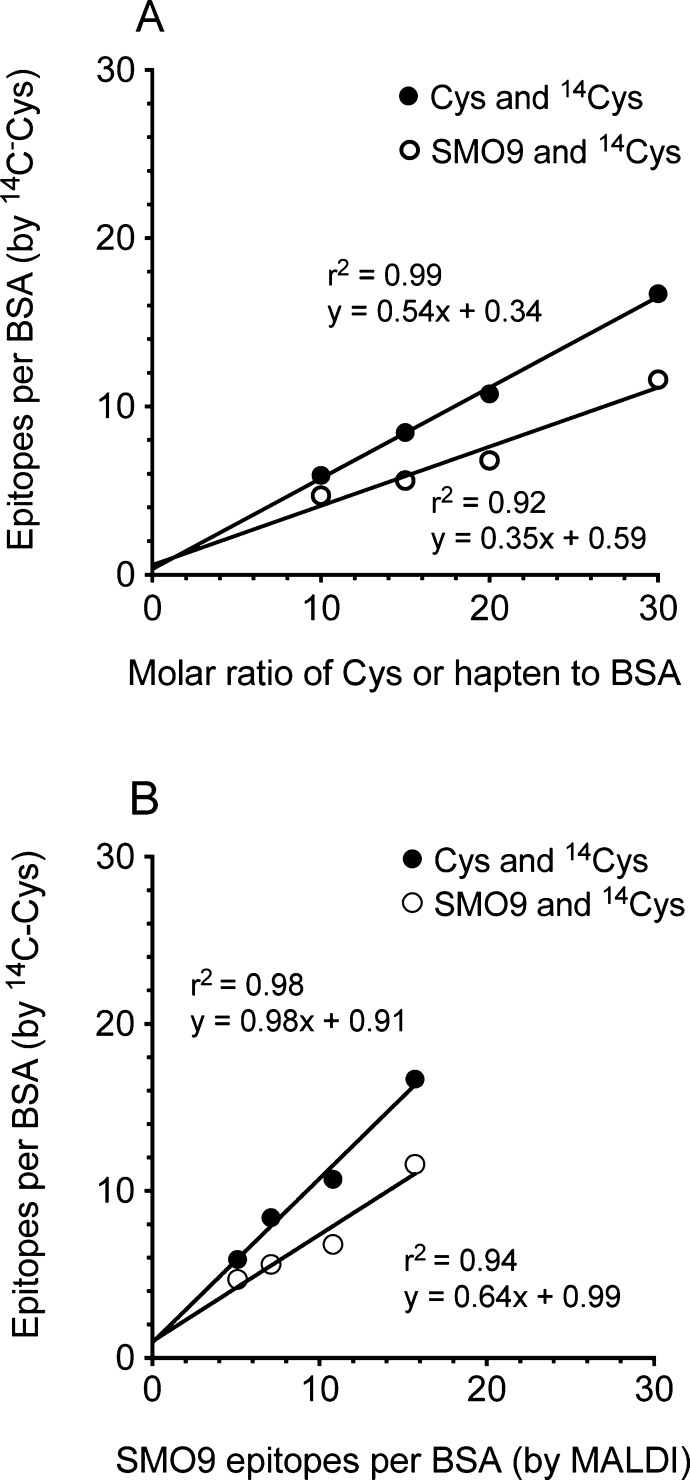

Since the values for coefficients of determination (r2) were near 1.0 (Figure 3A), both the noncompetitive and competitive radiometric assays showed a strong linear relationship throughout the range of BSA:hapten ratios. This indicated that the available maleimide groups did not reach saturation in either assay, but the differences in slopes between the noncompetitive and competitive radiometric assays (0.54 vs 0.35, respectively) suggested there was unequal competition for the covalent binding of 14C-Cys and SMO9.

Figure 3.

(A) Linear regression analysis of the number of epitopes incorporated in the radiometric assays (SMO9 with a 14C-Cys tracer: open symbol; and unlabeled cysteine with a 14C-Cys tracer: closed symbol) versus the ratio of SMO9 hapten to maleimide activated BSA. (B) Relationship between the predicted number of epitopes by the 14C-Cys radiometric assays and the number of observed SMO9 epitopes by MALDI-TOF analysis. As judged by linear regression analysis, there was an excellent correlation between predicted and observed values in the cysteine and 14C-Cys assay, but the SMO9 and 14C-Cys analysis significantly underpredicted the true number of SMO9 epitopes.

The epitope density values predicted from the two radiochemical assays in Figure 3A were then correlated with the direct MALDI-TOF measurements of SMO9 epitope density values using linear regression analysis (Figure 3B). Calculation of SMO9-equivalents based on the competitive SMO9-14C-Cys tracer assay indicated that this method underestimated the SMO9 epitope densities compared to the MALDI-TOF analysis of SMO9 epitopes (slope = 0.64, r2 = 0.94; Figure 3B). The measurement of epitope densities as 14C-Cys-equivalents in the noncompetitive assay proved to be the accurate measurement of SMO9 hapten incorporation based on the excellent values for the slope, y-intercept, and coefficient of determination (slope = 0.98, r2 = 0.99; Figure 3B). Using this new method we also determined the average SMO9 hapten density on the ICKLH dimers shown in Figure 2C and D was 14 haptens per ICKLH.

These findings suggest that under these (noncompetitive) reaction conditions both ligands are able to achieve the same maximal binding, but perhaps at a different rate. This positive result was aided by the fact that we carefully optimized each of the reactions to allow maximal binding, which resulted in the same final epitope densities for each ligand.

This simple and versatile radiometric method for determining the extent of hapten–protein conjugation with sulfhydryl linkages could potentially be broadly useful in determining the epitope density of therapeutic vaccines (for treating drug abuse or other medical or veterinary purposes), antibody–drug conjugates, antibody–nanoparticle conjugate, and other protein conjugations. However, further testing and validation of the method with other hapten and protein combinations will ultimately determine the broader applicability and accuracy of the method.

Even if the analysis of a carrier protein conjugate is feasible by mass spectrometry or colorimetric assays, this relatively quick method has advantages because it is inexpensive compared to mass spectrometry, does not require radioactive haptens, can be used for measurements of very large and complex proteins (e.g., ICKLH is a dimer), and, unlike protein colorimetric methods, only requires microgram quantities of protein. These advantages could be useful during the optimization and monitoring of conditions for hapten–protein conjugations, and choosing the most effective epitope densities for conjugate vaccines.

Acknowledgments

The National Institute on Drug Abuse (U01 DA023900, R01 DA026423, T32 DA022981), Arkansas Biosciences Institute, and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (UL1 TR000039) supported this work.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- BSA

bovine serum albumin

- 14C-Cys

carbon-14 labeled l-cysteine

- ICKLH

Immunocyanin monomers of Keyhole limpet hemocyanin

- KLH

Keyhole limpet hemocyanin

- MALDI-TOF

Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization Time of Flight

- SMO9

mercapto-hapten (S)-N-(2-(mercaptoethyl)-6-(3-(2-(methylamino)propyl)phenoxy)hexanamide

- METH

(+)-methamphetamine

- Sulfo-SMCC

sulfosuccinimidyl 4-[N-maleimidomethyl]cyclohexane-1-carboxylate

- TCEP

Tris (2-carboxyethyl)phosphine

Supporting Information Available

Detailed methods. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

The authors declare the following competing financial interest(s): SMO has financial interests in and serves as Chief Scientific Officer of InterveXion Therapeutics LLC (Little Rock, AR), a pharmaceutical biotechnology company focused on treating human drug addiction with antibody-based therapy..

Funding Statement

National Institutes of Health, United States

Supplementary Material

References

- Klaus G. G.; Cross A. M. (1974) The influence of epitope density on the immunological properties of hapten-protein conjugates. I. Characteristics of the immune response to hapten-coupled albumen with varying epitope density. Cell Immunol. 14, 226–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson E. C.; Gunnell M.; Che Y.; Goforth R. L.; Carroll F. I.; Henry R.; Liu H.; Owens S. M. (2007) Using hapten design to discover therapeutic monoclonal antibodies for treating methamphetamine abuse. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 322, 30–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno A. Y.; Mayorov A. V.; Janda K. D. (2011) Impact of distinct chemical structures for the development of a methamphetamine vaccine. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 6587–6595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll F. I.; Blough B. E.; Pidaparthi R. R.; Abraham P.; Gong P. K.; Deng L.; Huang X.; Gunnell M.; Lay J. O.; Peterson E. C.; Owens S. M. (2011) Synthesis of mercapto-(+)-methamphetamine haptens and their use for obtaining improved epitope density on (+)-methamphetamine conjugate vaccines. J. Med. Chem. 54, 5221–5228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll F. I.; Abraham P.; Gong P. K.; Pidaparthi R. R.; Blough B. E.; Che Y.; Hampton A.; Gunnell M.; Lay J. O.; Peterson E. C.; Owens S. M. (2009) The synthesis of haptens and their use for the development of monoclonal antibodies for treating methamphetamine abuse. J. Med. Chem. 52, 7301–7309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellman G. L. (1959) Tissue sulfhydryl groups. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 82, 70–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adamczyk M.; Buko A.; Chen Y. Y.; Fishpaugh J. R.; Gebler J. C.; Johnson D. D. (1994) Characterization of protein-hapten conjugates. 1. Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization mass spectrometry of immuno BSA-hapten conjugates and comparison with other characterization methods. Bioconjugate Chem. 5, 631–635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen M. K.; Sorensen N. S.; Heegaard P. M. H.; Beyer N. H.; Bruun L. (2006) Effect of different hapten-carrier conjugation ratios and molecular orientations on antibody affinity against a peptide antigen. J. Immunol. Methods 311, 198–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahouh F.; Hou S.-J.; Kováč P.; Banoub J. H. (2012) Determination of glycation sites by tandem mass spectrometry in a synthetic lactose-bovine serum albumin conjugate, a vaccine model prepared by dialkyl squarate chemistry. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 26, 749–758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rüedi-Bettschen D.; Wood S. L.; Gunnell M. G.; West C. M.; Pidaparthi R. R.; Carroll F. I.; Blough B. E.; Owens S. M. (2013) Vaccination protects rats from methamphetamine-induced impairment of behavioral responding for food. Vaccine 31, 4596–4602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swerdlow R. D.; Ebert R. F.; Lee P.; Bonaventura C.; Miller K. I. (1996) Keyhole limpet hemocyanin: structural and functional characterization of two different subunits and multimers. Comp. Biochem. Physiol., Part B: Biochem. Mol. Biol. 113, 537–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downham M. R.; Auton T. R.; Rosul A.; Sharp H. L.; Sjöström L.; Rushton A.; Richards J. P.; Mant T. G. K.; Gardiner S. M.; Bennett T.; Glover J. F. (2003) Evaluation of two carrier protein-angiotensin I conjugate vaccines to assess their future potential to control high blood pressure (hypertension) in man. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 56, 505–512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampson J. H.; Heimberger A. B.; Archer G. E.; Aldape K. D.; Friedman A. H.; Friedman H. S.; Gilbert M. R.; Herndon J. E.; McLendon R. E.; Mitchell D. A.; Reardon D. A.; Sawaya R.; Schmittling R. J.; Shi W.; Vredenburgh J. J.; Bigner D. D. (2010) Immunologic escape after prolonged progression-free survival with epidermal growth factor receptor variant III peptide vaccination in patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 28, 4722–4729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estévez M.-C.; Galve R.; Sánchez-Baeza F.; Marco M.-P. (2008) Disulfide symmetric dimers as stable pre-hapten forms for bioconjugation: a strategy to prepare immunoreagents for the detection of sulfophenyl carboxylate residues in environmental samples. Chemistry 14, 1906–1917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.