Abstract

Background

Alcoholism is a complex behavioral disorder in which interactions between stressful life events and heritable susceptibility factors contribute to the initiation and progression of disease. Neural substrates of these interactions remain largely unknown. Here, we examined the role of the nociceptin/orphanin FQ (N/OFQ) system, using an animal model in which genetic selection for high alcohol preference has led to co-segregation of elevated behavioral sensitivity to stress (msP rats).

Methods

msP and Wistar rats trained to self-administer alcohol received central injections of N/OFQ. In situ hybridization, and receptor binding assays were also performed to evaluate N/OFQ receptor (NOP) function in naïve msP and Wistar rats.

Results

Intracerebroventricular (ICV) injection of N/OFQ significantly inhibited alcohol self-administration in msP but not in nonselected Wistar rats. NOP receptor mRNA expression and binding was upregulated across most brain regions in msP compared to Wistar rats. However, in msP rats [35S]GTPγS binding revealed a selective impairment of NOP receptor signaling in the central amygdala (CeA). Ethanol self-administration in msP rats was suppressed after N/OFQ microinjection into the CeA but not into the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis or the basolateral amygdala.

Conclusions

These findings indicate that dysregulation of N/OFQ-NOP receptor signaling in the CeA contributes to excessive alcohol intake in msP rats, and that this phenotype can be rescued by local administration of pharmacological doses of exogenous N/OFQ. Data are interpreted based of the anti-CRF actions of N/OFQ and the significance of the CRF system in promoting excessive alcohol drinking in msP rats.

Keywords: Addiction, Nociceptin/Orphanin FQ; NOP receptors; Central Amygdala; Alcohol Preferring Rats; Alcoholism

Introduction

Nociceptin/Orphanin FQ (N/OFQ) is the endogenous ligand of the opioid receptor-like 1 receptor, recently included in the opioid receptor family and re-named NOP (1,2 ). Neuroanatomical studies (3,4) have shown a wide distribution of N/OFQ and its receptor in structures involved in motivational effects of addictive drugs (5,6,7), including the amygdala, the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BNST), the nucleus accumbens and various fronto-cortical areas. Evidence for a role of the N/OFQ system in behavior motivated by drugs of abuse is particularly robust in the case of alcohol (8,9,10,11). Studies in genetically selected Marchigian Sardinian alcohol-preferring (msP) rats demonstrated that intracerebroventricular (ICV) treatment with N/OFQ inhibits ethanol-induced conditioned place preference, home cage ethanol drinking, operant ethanol self-administration and relapse (8,9,12,13).

Recent data suggest that preclinical findings with N/OFQ may have a good potential for clinical translation. In fact, the opioid agonist/partial agonist buprenorphine, that has long been in clinical use for the treatment of pain (14,15,16) and management of heroin dependence (17,18,19) reduces alcohol drinking in msP rats via activation of NOP receptors (20). Consistent with this finding there are clinical data indicating that buprenorphine given to heroin addicts lowers not only opiate but also alcohol consumption (17,19). These data point to the possibility that buprenorphine effects on alcohol drinking are mediated by activation of NOP receptors.

In the perspective of future clinical application of novel and selective NOP agonists, here we examined the effects of N/OFQ in msP rats, in which genetic selection for high ethanol preference has co-segregated with hypersensitivity to stress and anxiety (21, 22). We first evaluated the effect of subchronic ICV application of N/OFQ on ethanol self-administration in msP rats and compared it with effects obtained in nonselected Wistar rats. The results revealed that N/OFQ significantly inhibits alcohol drinking in msP rats, but not Wistar rats. An extensive brain in situ hybridization and NOP receptor autoradiography study showed that NOP receptors are upregulated in msP, compared to Wistar rats. Surprisingly, however, N/OFQ-stimulated [35S]GTPγS binding in the central amygdala (CeA) was lower in msP rats indicating dysregulated NOP receptor/G protein coupling mechanisms in this brain area that renders the system hypofunctional. Subsequent brain microinjection studies demonstrated that administration of N/OFQ into the CeA, but not into the BNST or the basolateral amygdala (BLA) selectively reduces ethanol self-administration in msP rats. Together, these findings suggest that dysregulation of the NOP receptor system in the CeA contributes to the elevated alcohol drinking of msP rats and that, exogenous administration of NOP receptor agonists may act by restoring N/OFQ neurotransmission in this brain area.

Methods and Materials

Subjects

Male genetically selected Marchigian Sardinian alcohol-preferring (msP) and nonselected Wistar rats (bw 350−450) were studied. msP rats were bred at the Department of Experimental Medicine and Public Health of the University of Camerino (Italy). Wistar rats, purchased from Charles River (Germany) were habituated to the same housing condition as msP rats for one month before the beginning of the experiments. Experiments were conducted during the dark phase of a 12-h/12-h light/dark (lights on 8:00 p.m.). All procedures were conducted in adherence with the European Community Council Directive for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Drugs

Nociceptin/Orphanin FQ was a generous gift of Dr. R. Guerrini (University of Ferrara, Italy); it was dissolved in sterile isotonic saline and injected in a volume of 1.0 μl per rat or 0.5 μl per site/rat into the lateral cerebroventricle or into the specific brain areas, respectively.

Intracranial surgery

Anaesthetized rats were stereotaxically implanted (for coordinates see Table 1) with guide cannula aimed at the respective brain structure. Experiments began 1 week after surgery. After completion of the experiments, rats were killed and cannula placements were verified by histological analysis.

Table 1.

Brain stereotaxic coordinates for cannula placement. Rats were anethetized by intramuscular injection of 100−150 μl of a solution containing tiletamine cloridrate (58.17 mg/ml) and zolazepam cloridrate (57.5 mg/ml). Guide cannulas (0.65 mm outside diameter) werte stereotaxically implanted and cemented to the skull.

| Region | Antero-Posterior | Lateral | Ventral |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lateral Cerebroventricle (ICV) | −1.0 | 1.8 | 2.0 |

| Bed Nucleus of the Stria Terminalis (BNST) | −0.1 | ±1.3 | 6.0 |

| Central Amygdala (CeA) | −1.5 | ±4.3 | 7.0 |

| Basolater Amygdala (BLA) | −1.5 | ±5.1 | 7.0 |

N/OFQ, was injected through a stainless-steel injector (0.25 mm outside diameter) protruding beyond the cannula tip: 2.5 mm for the lateral ventricle; 1.2 mm for the BNST; and 1.5 mm for the CeA, and the BLA.

Alcohol self-administration training

Rats were trained to self-administer 10% (v/v) ethanol in 30-min daily sessions under a fixed-ratio 1 (FR1) schedule of reinforcement where each response resulted in delivery of 0.1 ml of fluid. A saccharin fading procedure was used to train the rats to 10% ethanol self-administration (9,23). Briefly, animals were first trained to lever press for 0.2% (w/v) saccharin solution. After successful acquisition of saccharin-reinforced responding for 2 days rats were trained to self-administer 0.2% saccharin solution containing 5.0% ethanol. Beginning on day 3, the concentration of ethanol was gradually increased from 5.0% to 8.0% and finally 10%, while the concentration of saccharin was correspondingly decreased to 0%. From the first day, rats began to press for 10% ethanol, the house light located on the front panel was turned on for 5.0 s.

During the experiments responses at the active and the inactive levers were always recorded.

Experiment 1. Effect of subchronic ICV injections of N/OFQ on alcohol self-administration in msP and Wistar rats

After acquisition of a stable 10% ethanol self-administration baseline (10 days), msP rats (n=21) and Wistar rats (n=27) were divided into three and four groups, respectively. During the last 4 days of training (pre-treatment), immediately prior to the self-administration sessions, rats were given 1 μl of ICV saline to familiarize them with the injection procedure. Then, for six consecutive days msP (n=7/group) and Wistar rats (n=6−7/group) received 0.0, 0.5 and 1.0 μg/rat or 0.0, 1.0, 2.0 and 4.0 μg/rat of N/OFQ or its vehicle. Rats were tested for 10% ethanol self-administration immediately after drug administration. At completion of drug testing ethanol self-administration was monitored for additional 4 days (post-treatment) during which all rats received only ICV saline.

Experiment 2. N/OFQ and NOP receptor in situ hybridization

For in situ hybridization, receptor binding and receptor activity (see also Experiments 3 and 4) rats were sacrificed in their inactive phase by decapitation, brains were quickly removed, snap frozen in −40 °C isopentane and stored at −70 °C. 10 μm coronal brain sections were taken at Bregma levels as illustrated in Figure 1 according to the atlas of Paxinos and Watson (1998) and stored at −70 °C until use (24).

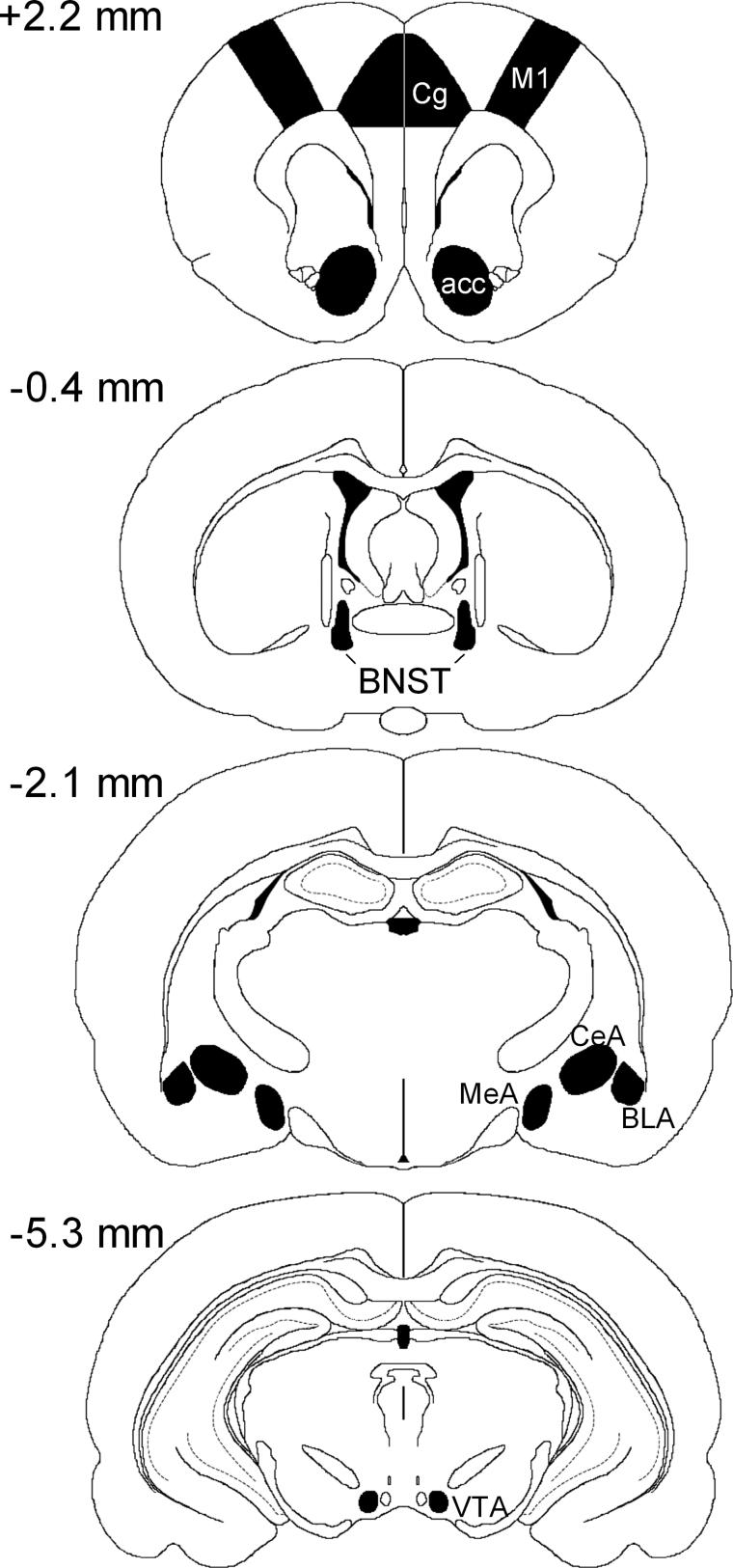

Fig 1.

Schematic representation of the sampled areas for the densitometric evaluation of mRNAs in a coronal section through the rat forebrain at Bregma levels +2 to −5 mm. CG, cingulate cortex; M1, primary motor cortex; n acc, nucleus accumbens; BNST, bed nucleus of stria terminalis; CeA, central amygdaloid nucleus; MeA, medial amygdaloid nucleus; BLA, basolateral amygdaloid nucleus; VTA, ventral tegmental area

In situ hybridization for rat specific riboprobes for N/OFO (gene reference sequence in PubMed database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Entrez/): NM_013007, position 275 to 535 bp) and NOP receptor (gene reference sequence in PubMed database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Entrez/): NM_031569, position 879 − 1142 bp) have been recently shown in Hansson et al (2006) (22). Procedures for RNA probe synthesis in both antisense and sense direction and all the hybridization steps have been in detail described in Hansson et al (2003) (25).

For data visualization phosphor imaging plates (Fuji-film for BAS-5000, Fujifilm corp., Japan) were exposed for 48 hours to hybridized sections. Phosphor imager (Fujifilm Bio-Imaging Analyzer Systems, BAS-5000, Fujifilm corp., Japan) generated digital images were analyzed using MCID Image Analysis Software (Imaging Research Inc., UK). Regions of interest were defined by anatomical landmarks as described in the atlas Paxinos & Watson (1998) (24) and illustrated in Figure 1. Signal density was measured as photostimulable luminescence per mm2 and converted into integrated optical density values, expressed in calibration standards units (nCi/g) using a C14 standard curve (Microscale C14, AMERSHAM GE Healthcare, UK). For detailed visualization, films (Kodak BioMax MR, Eastman Kodak Company, New York) were subsequently exposed for 1 month to hybridized sections.

Experiment 3. NOP receptor autoradiography

For autoradiography, sections were brought up to room temperature, incubated for 15 minutes at room temperature in 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.5) containing 5 mM MgCl2 and 1 mM EDTA. This incubation step was repeated with a fresh buffer. Sections were then transferred into humidified chambers and 800 μl of reaction mix was applied to each slide and sections were incubated for 2 hours at room temperature. Reaction mix contained 1 nM [3H]-nociceptin (specific activity 90 Ci/mmol, New England Nuclear, USA) prepared in a buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EDTA, 0.1 mM bacitracin and 0.1% bovine serum albumine. Non-specific binding was measured on adjacent sections by adding 1 μM UFP-101 (N/OFQ receptor antagonist, Tocris Bioscience, Ellisville, Missouri, USA). Incubation was stopped by washing the sections twice in ice cold buffer followed by a dip in ice-cold deionized water. Sections were dried under a stream of cold air, and were used to expose Fuji BAS-5000 Phosphorimager tritium plates for 10. Density values were measured as described above and compared against standard curves generated using [3H]-microscales (Amersham) and data (nCi/mg) were converted to fmol receptor per mg protein tissue equivalence. Specific binding was defined as a difference between total and non-specific binding.

Experiment 4. NOP receptor signaling

Sections were brought up to room temperature and incubated for 15 minutes at room temperature in a 50mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) buffer containing 5 mM MgCl2 and 1 mM EDTA. Incubation was repeated once and sections transferred into humidified chambers. 500 μl of incubation buffer (50mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EDTA, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT, 0.1%BSA) containing 1 mM GDP was applied to each slide and sections were incubated for 15 minutes at room temperature. Solution was discarded and a mix of 50 pM [35S]GTPγS, 1 mM GDP and 1 μM N/OFQ or vehicle in incubation buffer were applied. Sections were incubated for 60 minutes at 30°C and incubation was stopped by washing the slides for two minutes in ice cold buffer followed by a dip in ice cold deionized water. Sections were dried under a stream of cold air and used to expose Fuji BAS-5000 Phosphorimager plates. Agonist stimulated and baseline [35S]GTPγS binding was measured on adjacent sections as described above using [14C]-microscales (Amersham) standard curve. Percent stimulation was calculated as difference between agonist stimulated and baseline bindings and expressed as percent of baseline value in the same region and animal.

Experiment 5. Effect of N/OFQ microinjections into the CeA, the BLA or the BNST on alcohol self-administration in msP rats

Using the same procedure described in Experiment 1 msP rats were trained to operant ethanol self-administration until stable baseline of responding was reached. At this point rats were subjected to intracranial surgery and then ethanol self-administration baseline was reestablished. One group of msP rats (n=30) with brain cannulae implanted bilaterally into the CeA was subdivided into three groups that were treated with N/OFQ 0.125 or 0.25 μg site/rat or drug vehicle, respectively. A second group of msP rats (n=30) with brain cannulae implanted bilaterally into the BLA was subdivided into three groups to receive N/OFQ 0.25, 0.5 μg site/rat or N/OFQ vehicle, respectively. A third group of rats (n=24) implanted bilaterally with cannulae aimed at the BNST was subdivided into 3 groups to receive N/OFQ 0.25, 0.5 μg site/rat or N/OFQ vehicle, respectively.

On experimental day 1 (pre-treatment) all rats were subjected to a mock bilateral injection of vehicle to familiarize them with the treatment procedure. On day 2 (test day), rats were tested for the effect of N/OFQ, whereas on day 3 (post-treatment), all rats received 0.5 μl site/rat of vehicle again. Immediately after brain microinjections, rats were placed in the self-administration chambers and tested for 10% ethanol self-administration.

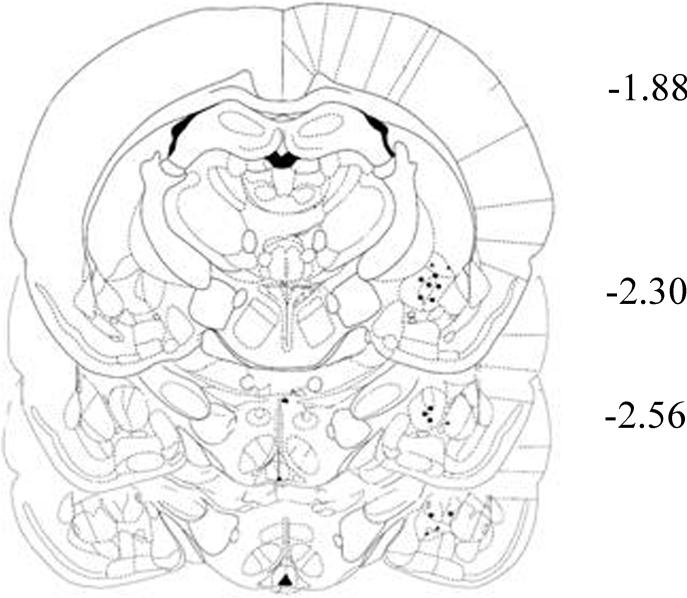

At the end of the experiments, cannula placement was verified by histological analysis. Correct cannulae placement was confirmed in 21 of 30 rats in the CeA (Fig. 2), 22 of 30 rats in the BLA, and 19 of 24 rats in the BNST. Only data obtained in rats with correct cannulae placement were subjected to statistical evaluation.

Fig 2.

Representation of the location of the tips of the injectors (filled circles) within the CeA. Numbers indicate the distances from bregma in millimeters (adapted from Paxinos and Watson 1998)

Statistical analysis

Data from experiments with subchronic N/OFQ treatment (Exp. 1) were analyzed by means of two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with one within-subjects factor (test session) and one between subjects factor (N/OFQ dose). The effect of N/OFQ given into the CeA, BNST and BLA (Exp. 5) was analyzed by one-way ANOVA with one between subject factor (N/OFQ dose). For behavioral experiments post-hoc comparisons were performed by Newman-Keuls tests. Gene expression (Exp. 2), receptor binding (Exp. 3) and receptor activity (Exp. 4) data had homogeneous variances within respective regions and were, therefore, compared by region-wise one-way parametric ANOVAs, followed by Holm-Bonferroni correction.

Results

Experiment 1. Effect of subchronic ICV injections of N/OFQ on alcohol self-administration inmsP and Wistar rats

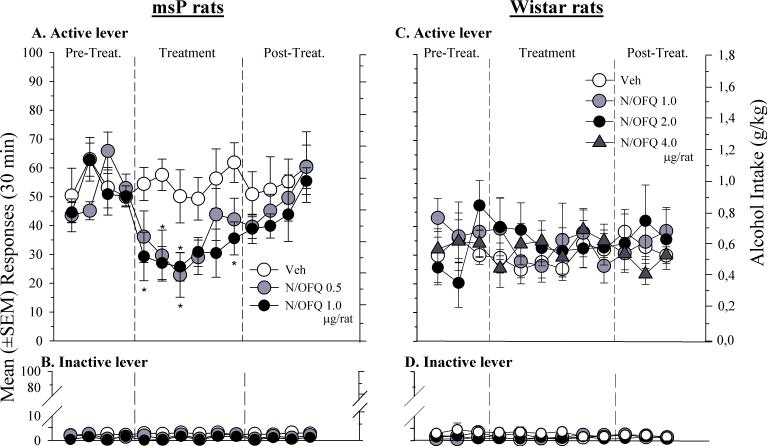

As shown in Fig. 3A, subchronic (6 days) ICV treatment with N/OFQ (0.5 and 1.0 μg/rat) markedly reduced responding on the active lever in msP rats [F(2,18) = 6.7, p < .01]. Newman-Keuls post-hoc test confirmed a significant difference between controls and rats treated with 0.5 and 1.0 μg/rat of N/OFQ.

Fig 3.

Self-administration for 10% ethanol under a FR-1 schedule of reinforcement in: Left Panel) msP rats treated ICV for 6 consecutive days with 0.5, 1.0 μg/rat of N/OFQ or its vehicle (Veh), and, Right Panel) Wistar rats treated ICV for 6 consecutive days with 1.0, 2.0 and 4.0 μg/rat of N/OFQ or its vehicle (Veh). Figures A) and C) correspond to the number of reinforced active lever presses, whereas, B) and D) correspond to the number of inactive lever presses. Values represent the mean (± SEM) of 6−7 subject/group. Difference from vehicle * P < 0.05; ** P< 0.01.

Conversely, N/OFQ, did not significantly modify [F(3,23) = 0.44, p = ns] ethanol-maintained responding in Wistar rats (Fig. 3C). In these rats the peptide was given at doses up to 8 times higher than that effective in reducing alcohol self-administration in msP rats. Responses on the inactive lever were negligible in all treatment conditions for both msP [F(2,18) = 2.731, p = ns] (Fig. 3B) and Wistar rats [F(3,23) = 2.02, p = ns] (Fig. 3D).

Experiment 2. N/OFQ and NOP receptor in situ hybridization

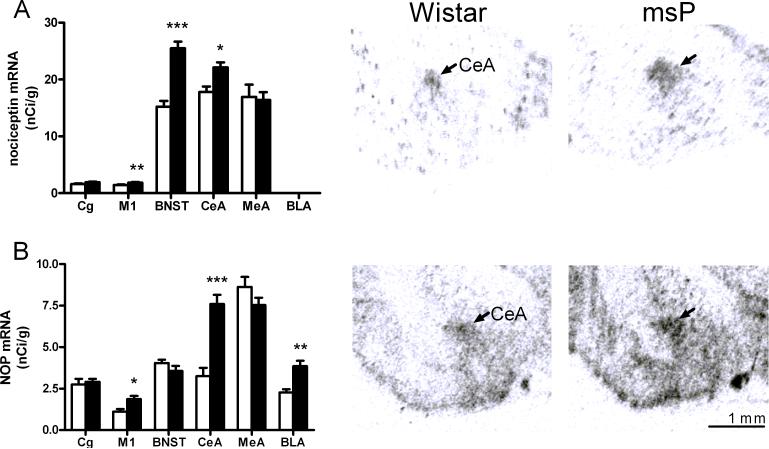

Consistent with existing literature, N/OFQ and NOP receptor mRNAs showed an overlapping pattern of distribution. The highest expression of N/OFQ mRNA was found in the CeA, the BNST and the medial amygdala. Moderate expression was identified in various hippocampal subregions, while in the BLA expression of the peptide precursor was undetectable. The expression of NOP transcript was highest in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus, moderate levels were measured in the BNST and in various amygdaloid and hippocampal subregions. Comparison between msP and Wistar rats revealed that N/OFQ and NOP receptor mRNA levels were significantly higher in the alcohol-preferring rats. As shown in Table 2 (supplementary material) and Figure 4, the largest differences between the lines were identified in the motor cortex (M1), BNST and CeA for the N/OFQ precursor, and in the BNST, CeA and M1 for the NOP precursor, respectively.

Fig 4.

A) Left panel: Up-regulated N/OFQ mRNA expression in msP rats compared with Wistar rats (nCi/g ± SEM., n=7−8; ***P<0.001; **P<0.01; * P<0.05). Right panel : Illustrative autoradiogram showing increased N/OFQ expression in msP (Scale bars, 1 mm.). B) Left panel: Up-regulated NOP receptor mRNA expression in msP rats (black bars) compared with Wistar (white bars) rats (nCi/g ± SEM., n=7−8; ***P<0.001; ** P<0.01; * P<0.05). Right panel : Illustrative autoradiogram showing increased NOP expression in msP. (Scale bars, 1 mm.). For abbreviations see Figure 1, for details on treatment, see Material and Methods.

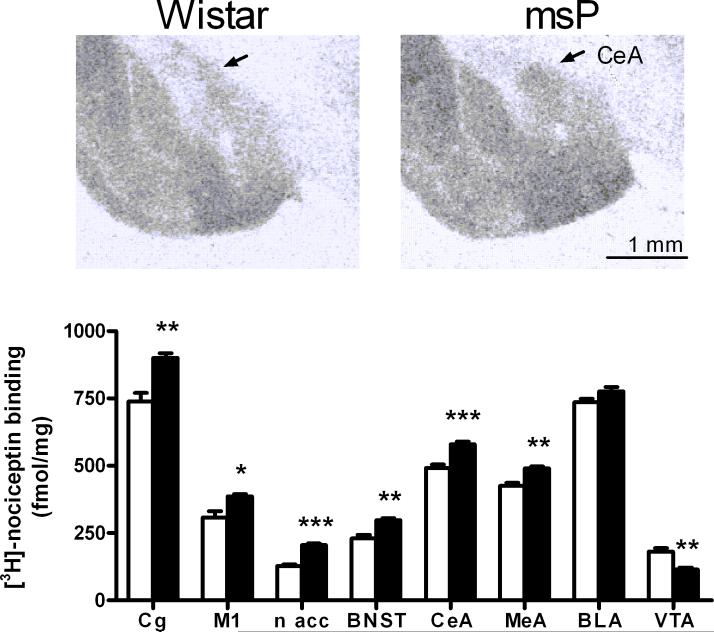

Experiment 3. NOP receptor autoradiography

To evaluate if differences in NOP mRNA expression translate into changes in binding capacity, a binding study was carried out. Confirming existing data (26,27), we found high levels of NOP receptor binding in various cortical and amygdaloid subregions including M1, cingulate cortex, CeA, MeA and BLA. Moderate NOP receptor density was found in the BNST. As shown in Table (supplementary material) and in Fig. 5, comparison between msP and Wistar rats revealed that NOP receptor density was significantly higher in the alcohol-preferring line. The largest differences were found in the CeA, MeA, BNST, nucleus accumbens, and cingulate cortex. In the BLA, the difference between rat strains was not significant.

Fig 5.

Lower panel: Elevated NOP mRNA expression in msP rats was accompanied by increased density of NOP binding sites in numerous brain regions, shown with [3H]-nociceptin using UFP-101 (N/OFQ receptor antagonist) to measure non-specific binding (rats; n = 8 per group; mean ± SEM; *** P < 0.001; ** P <0.01; * P <0.05). Upper panel: Illustrative autoradiogram showing increased total [3H]-nociceptin binding in msP rats. For abbreviations see Figure 1, for details on treatment see Material and Methods.

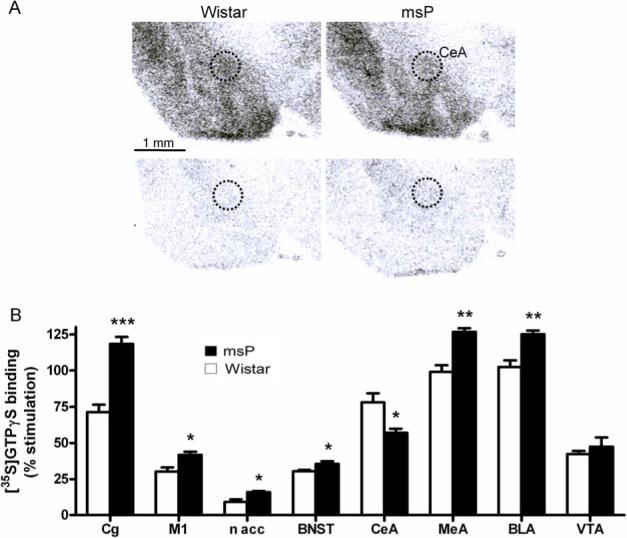

Experiment 4. NOP receptor signaling

An autoradiographic [35S]GTPγS binding assay was used to measure G-protein signaling following activation of the NOP receptor. Consistent with the receptor autoradiographic results, agonist stimulated NOP receptor function was generally higher in msP rats, presumably reflecting the increased receptor density (Table 3; supplementary material). Surprisingly, however, following N/OFQ stimulation, a significantly lower response was detected in the CeA of msP rats despite higher NOP receptor density in this region (Fig.6). This unexpected finding prompted us to further investigate NOP receptor functionality by analyzing the effect of N/OFQ microinjection into the CEA on ethanol self-administration in msP rats.

Fig 6.

A). Illustrative autoradiogram showing [35S]GTPγS binding in stimulated (upper panel) and baseline condition (lower panel). MsP rats show lower nociceptin stimulated [35S]GTPγS binding in CeA (right upper panel) as compared to Wistar rats (left upper panel). B) Nociceptin stimulated [35S]GTPγS binding. Percent stimulation was calculated as a difference between agonist stimulated and baseline bindings and expressed as percent of baseline value in the same region and animal (rats; n = 8 per group; mean ± SEM; *** P < 0.001; ** P <0.01; * P <0.05). Results depicted a general increase of NOP receptor functionality in msP rats except in the central amygdala where it was significantly lower. For abbreviations see Figure 1, for details on treatment see Material and Methods.

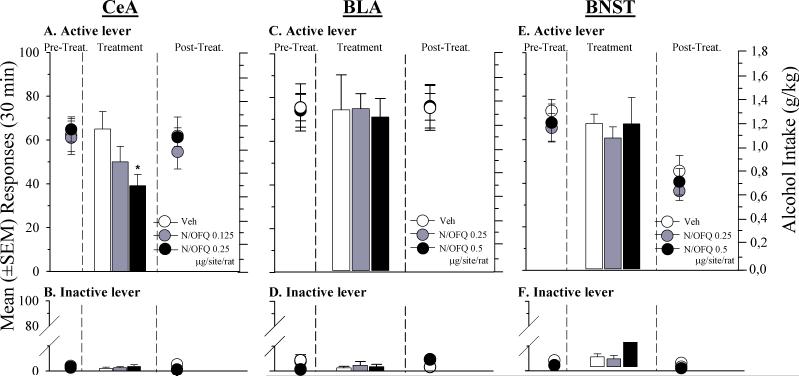

Experiment 5. Effects of N/OFQ microinjections into the CeA, BLA or BNST on alcohol self-administration in msP rats

All rats acquired responding reinforced by 10% ethanol and developed stable ethanol self-administration. Analysis of variance revealed a main effect of treatment [F(2,18) = 0.61, p < .05] in rats injected into the CeA. As shown in Fig. 7A, Newman-Keuls post-hoc tests showed that microinjection of N/OFQ (0.25 μg per site/rat) into this brain area markedly reduced ethanol self-administration in msP rats (p < .05). Following treatment with a lower dose of N/OFQ (0.125 μg per site/rat), a trend toward reduced ethanol self-administration was observed, although this effect was not statistically significant (Fig. 7A).

Fig 7.

Self-administration for 10% ethanol under a FR-1 reinforcement schedule in msP rats treated into: Left Panel) the central amygdala (CeA) with 0.125 and 0.25 μg/site/rat of N/OFQ or its vehicle (Veh); Central Panel) the basolateral amygdala (BLA) with 0.25 and 0.5 μg/site/rat of N/OFQ or its vehicle (Veh); Right Panel) the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BNST) with 0.25 and 0.5 μg/site/rat of N/OFQ or its vehicle (Veh) at: A, B, C) Number of reinforced active lever presses; D, E, F) Number of inactive lever presses. Values represent the mean (± SEM) of 6−8 subject/group. Difference from controls (vehicle) * P < 0.05.

In the BLA (Fig. 7C) and in the BNST (Fig. 7E) microinjection of N/OFQ, at doses two times higher than those used in the CeA, did not significantly modify ethanol self-administration [F(2,19) = 0.02, p = ns and F(2,16) = 0.21, p = ns, respectively]. During the post-treatment phase of the BNST study, we observed a trend-level [F(4,32) = 0.07, p = ns] reduction of lever presses after both N/OFQ and vehicle microinfusion. This effect appears to be non specific and is presumably related to the microinjection procedure rather than to a drug effect.

Responses at the inactive lever (Figs. 7B, 7D and 7F) were almost absent in all treatment conditions and were not affected by intracerebral injections of the peptide ([F(2,18) = 0.63, p = ns], [F(2,19) = 0.09, p = ns] and [F(2,16) = 0.83, p = ns] in the CeA, BLA and BNST, respectively).

Discussion

In agreement with previous reports, we show here that subchronic ICV administration of N/OFQ significantly reduces ethanol self-administration in msP rats (9). In contrast, in nonselected Wistar rats tested under the same experimental conditions N/OFQ did not alter ethanol consumption. These findings parallel recently published data showing that administration of corticotropin releasing factor (CRF) receptor-1 antagonists reduces ethanol drinking in msP but not in unselected non-dependent Wistar rats (22, 28). Several previous studies have demonstrated that N/OFQ acts as a functional antagonist at the extrahypothalamic CRF1 receptor system (29). For example, central administration of the peptide prevents several behavioral effects of stress, including anorexia elicited by intracranial injection of CRF or footshock-induced reinstatement of alcohol-seeking (29,30,31).

msP rats are highly sensitive to stress, show an anxious phenotype and exhibit depression-like behavioral signs that recover following ethanol drinking (21, 32). Elevated expression and function of the CRF1 receptor in numerous brain areas has recently been identified as a molecular substrate of both the anxious, stress-sensitive phenotype, and the high alcohol preference of msP rats (22). We therefore hypothesize that exogenous administration of N/OFQ, through its ability to reduce CRF1 mediated activity, may help to reduce the negative affective state of msP rats, and therefore lower their excessive ethanol intake by reducing the ethanol negative reinforcement. In contrast, in nonselected Wistar rats, ethanol drinking is predominantly positively reinforced via activation of the brain reward systems, an action that occurs independently from the brain CRF1 receptors system.

The in situ hybridization results showed higher expression of N/OFQ and NOP receptor mRNAs in numerous brain areas of msP rats compared to Wistar rats. In particular, we found significantly higher levels of N/OFQ mRNA in the M1, BNST, and CeA of msP rats, while NOP receptor transcript was higher in the M1, CeA and BLA of msP rats. Autoradiographic analysis showed that these gene expression changes were accompanied by significant increases in NOP receptor binding capacity in several brain areas, including the CeA, the BNST, the ventral tegmental area, and various cortical structures. Furthermore, the results of the [35S]GTPγS assay showed that this upregulation of NOP binding sites was also accompanied by a substantial increase in agonist-induced NOP receptor signaling in almost all the brain areas investigated. Based on these findings we propose that upregulation of the N/OFQ/NOP system occurs in msP rats in response to, and in an attempt to compensate the up-regulation of CRF1 receptors in this line of rats (22). This adaptive response may be one of several compensatory functional adaptations that occur in msP rats, such as upregulation of neuropetide Y and its receptors (22).

While consistent up-regulation of NOP receptor expression, binding and signaling were observed in msP vs. Wistar rats in the majority of brain regions examined, a distinct and unexpected pattern of differences was found in the CeA. In this brain region N/OFQ-stimulated [35S]GTPγS binding was significantly lower in msP rats than in Wistar rats despite elevated NOP receptor expression and binding in the msP line. This finding suggests uncoupling of the NOP receptor from its G proteins, leading to lower responsiveness to NOP receptor stimulation in CeA cells of msP rats. This in turn suggests that while the N/OFQ system is generally recruited in msP rats to counteract up-regulated CRF activity, uncoupling of the NOP receptor in CeA leads to selective breakdown of this adaptation in CeA. This is of particular interest, since recent data obtained in postdependent rats indicate that CRF activity in this structure is critical for the regulation of excessive ethanol self-administration (33, 34).

This hypothesis predicts that stimulation of NOP receptor activity in the CeA might help restore CeA functional equilibrium. In agreement with this prediction, we found that agonist administration into this brain area suppressed ethanol self-administration, at doses lower than those needed to reduce alcohol consumption following ICV administration. Alcohol self-administration was not affected by microinjection of N/OFQ into the BNST or BLA (two areas adjacent and neuroanatomically connected to the CeA), supporting the notion that the CeA is the brain site of action for this effect of N/OFQ.

Ethanol mediates its reinforcing properties through interactions with several neuronal systems (5). Among these, the CeA has recently been identified as a key region (35, 36), and GABAergic transmission in this brain area seems to play an important role. In fact, microinjection of GABAA receptor antagonists into the CeA significantly reduces ethanol self-administration in the rat (37, 38). In addition, electrophysiological studies show an increased GABAergic transmission in the CeA after ethanol superfusion (39), an effect blocked by N/OFQ pretreatment (10).

Interestingly, within CeA, CRF is expressed in GABAergic neurons, where it is co-released with GABA (40, 41), and ethanol-induced increase in GABAergic transmission within the CeA depends on CRF1 receptor activation (42). To our knowledge no studies have until now examined the interaction between GABA, N/OFQ and the CRF systems in the CeA. However, based on these indirect data one may speculate that reduction of ethanol intake following CeA injection of N/OFQ depends on the ability of this neuropeptide to inhibit ethanol-induced GABA release via functional CRF antagonism.

Activation of NOP receptors also results in marked functional anti-opioid activity (43) that may contribute to the effect of N/OFQ on ethanol self-administration. It is known, in fact, that treatment with anti-opioidergic agents significantly reduces alcohol drinking in rats, and the CeA has been found to be an important site for these effects (44). However, opioid antagonists reduce alcohol consumption not only in msP rats (21, 45), but also in non selected Wistars (44, 46, 47). Given our finding that N/OFQ selectively reduces alcohol self-administration in msP rats, it is unlikely that N/OFQ-induced reduction of ethanol drinking depends on its antiopioid activity.

In conclusion, present findings together with previously published reports, suggest that msP rats have an upregulated CRF1 receptor-mediated activity in the CeA and that the compensatory increase in NOP receptor neurotransmission found in other brain regions is absent or attenuated in this structure because of uncoupling of receptors from G proteins. We speculate that the imbalance between these “stress” (CRF) and “anti-stress” (N/OFQ) systems may play a causal role in sustaining excessive ethanol drinking in msP rats. Restoration of the stress response set point, either by administration of CRF1 receptor antagonists or NOP receptor agonist, may re-establish equilibrium in CeA function thereby reducing ethanol drinking in msP rats.

Lastly, the results of the present investigation support that agonism at NOP receptors or antagonism at CRF1 receptors may both be attractive pharmacotherapeutic strategies for alcohol addiction treatment. The combined anti-CRF and anti-opioid actions of N/OFQ may be synergistic and thus particularly attractive. These findings provide a rationale for evaluating N/OFQ agonism as a mechanism to treat alcohol dependence.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by funding from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Intramural Research Program and National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, NIH/NIAAA grant AA014351 (FW; subcontract RC) and PRIN 2006 (MM).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The authors report no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest. We wish to thank Mr. Marino Cucculelli for skilful technical assistance.

References

- 1.Meunier JC, Mollereau C, Toll L, Suaudeau C, Moisand C, Alvinerie P, Butour JL, Guillemot JC, Ferrara P, Monsarrat B, Mazarguil H, Vassart G, Parmentieer M, Costentin J. Isolation and structure of the endogenous agonist of opioid receptor- like ORL1 receptor. Nature. 1995;377:532–535. doi: 10.1038/377532a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reinscheid RK, Nothacker HP, Bourson A, Ardati A, Henningsen RA, Bunzow JR, Grandy DK, Langen H, Monsma FJ, Jr, Civelli O. Orphanin FQ: neuropeptide that activates an opioidlike G protein-coupled receptor. Science. 1995;270:792–794. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5237.792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Darland T, Heinricher MM, Grandy DK. Orphanin FQ/nociceptin: a role in pain and analgesia, but so much more. Trends Neurosci. 1998;21:215–221. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(97)01204-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mollereau C, Mouledous L. Tissue distribution of the opioid receptor-like (ORL1) receptor. Peptides. 2000;21:907–917. doi: 10.1016/s0196-9781(00)00227-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Koob GF, Roberts AJ, Schulteis G, Parsons LH, Heyser CJ, Hyytia P, Merlo-Pich E, Weiss F. Neurocircuitry targets in ethanol reward and dependence. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1998;22:3–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wise RA. Drug-activation of brain reward pathways. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1998;51:13–22. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(98)00063-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Everitt BJ, Wolf ME. Psychomotor stimulant addiction: a neural systems perspective. J Neurosci. 2002;22:3312–3320. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-09-03312.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ciccocioppo R, Panocka I, Polidori C, Regoli D, Massi M. Effect of nociceptin on alcohol intake in alcohol-preferring rats. Psychopharmacology. 1999;141:220–224. doi: 10.1007/s002130050828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ciccocioppo R, Economidou D, Fedeli A, Angeletti S, Weiss F, Heilig M, Massi M. Attenuation of ethanol self-administration and of conditioned reinstatement of alcohol-seeking behaviour by the antiopioid peptide nociceptin/orphanin FQ in alcohol-preferring rats. Psycopharmacology. 2004;172:170–178. doi: 10.1007/s00213-003-1645-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roberto M, Siggins GR. Nociceptin/orphanin FQ presynaptically decreases GABAergic transmission and blocks the ethanol-induced increase of GABA release in central amygdala. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:9715–9720. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601899103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kuzmin A, Kreek MJ, Bakalkin G, Liljequist S. The nociceptin/orphanin FQ receptor agonist Ro 64−6198 reduces alcohol self-administration and prevents relapse-like alcohol drinking. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2007;32:902–910. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ciccocioppo R, Angeletti S, Panocka I, Massi M. Nociceptin/orphanin FQ and drugs of abuse. Peptides. 2000;21:1071–1080. doi: 10.1016/s0196-9781(00)00245-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Martin-Fardon R, Ciccocioppo R, Massi M, Weiss F. Nociceptin prevents stress-induced ethanol- but not cocaine-seeking behavior in rats. Neuroreport. 2000;11:1939–1943. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200006260-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gundersen RY, Andersen R, Narverud G. Postoperative pain relief with high-dose epidural buprenorphine: a double-blind study. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1986;30:664–667. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.1986.tb02497.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vanacker B, Vandermeersch E, Tomassen J. Comparison of intramuscular buprenorphine and a buprenorphine/naloxone combination in the treatment of post-operative pain. Curr Med Res Opin. 1986;10:139–144. doi: 10.1185/03007998609110432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Picard PR, Tramer MR, McQuay HJ, Moore RA. Analgesic efficacy of peripheral opioids (all except intra-articular): a qualitative systematic review of randomised controlled trials. Pain. 1997;72:309–318. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(97)00040-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ling W, Wesson DR, Charuvastra C, Klett CJ. A controlled trial comparing buprenorphine and methadone maintenance in opioid dependence. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1996;53:401–407. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830050035005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johnson RE, McCagh JC. Buprenorphine and naloxone for heroin dependence. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2000;2:519–526. doi: 10.1007/s11920-000-0012-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kakko J, Svanborg KD, Kreek MJ, Heilig M. 1-year retention and social function after buprenorphine-assisted relapse prevention treatment for heroin dependence in Sweden: a randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2003;361:662–668. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12600-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ciccocioppo R, Economidou D, Rimondini R, Sommer W, Massi M, Heilig M. Buprenorphine reduces alcohol drinking through activation of the nociceptin/orphanin FQ-NOP receptor system. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;61:4–12. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ciccocioppo R, Economidou D, Cippitelli A, Cucculelli M, Ubaldi M, Soverchia L, Lourdusamy A, Massi M. Genetically selected Marchigian Sardinian alcohol-preferring (msP) rats: an animal model to study the neurobiology of alcoholism. Addict Biol. 2006;11:339–355. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2006.00032.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hansson AC, Cippitelli A, Sommer WH, Fedeli A, Bjork K, Soverchia L, Terasmaa A, Massi M, Heilig M, Ciccocioppo R. Variation at the rat Crhr1 locus and sensitivity to relapse into alcohol seeking induced by environmental stress. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:15236–15241. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604419103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weiss F, Lorang MT, Bloom FE, Koob GF. Oral alcohol self-administration stimulates dopamine release in the rat nucleus accumbens: genetic and motivational determinants. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1993;267:250–258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Paxinos G, Watson C. The rat brain in stereotaxic coordinates. 4th ed Academic; North Ryde, Australia: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hansson AC, Sommer W, Rimondini R, Andbjer B, Strömberg I, Fuxe K. c-fos reduces corticosterone-mediated effects on neurotrophic factor expression in the rat hippocampal CA1 region. J Neurosci. 2003;23:6013–6022. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-14-06013.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Anton B, Fein J, To T, Li X, Silberstein L, Evans CJ. Immunohistochemical localization of ORL-1 in the central nervous system of the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1996;368:229–251. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19960429)368:2<229::AID-CNE5>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sim LJ, Childers SR. Anatomical distribution of mu, delta, and kappa opioid- and nociceptin/orphanin FQ-stimulated [35S]guanylyl-5'-O-(gamma-thio)-triphosphate binding in guinea pig brain. J Comp Neurol. 1997;386:562–572. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19971006)386:4<562::aid-cne4>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gehlert DR, Cippitelli A, Thorsell A, Le AD, Hipskind PA, Hamdouchi C, Lu J, Hembre EJ, Cramer J, Song M, McKinzie D, Morin M, Ciccocioppo R, Heilig M. 3-(4-Chloro-2-morpholin-4-yl-thiazol-5-yl)-8-(1-ethylpropyl)-2,6-dimethyl-imidazo[1,2-b]pyridazine: a novel brain-penetrant, orally available corticotropin-releasing factor receptor 1 antagonist with efficacy in animal models of alcoholism. J Neurosci. 2007;27:2718–2726. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4985-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ciccocioppo R, Fedeli A, Economidou D, Policani F, Weiss F, Massi M. The bed nucleus is a neuroanatomical substrate for the anorectic effect of corticotropin-releasing factor and for its reversal by nociceptin/orphanin FQ. J Neurosci. 2003;23:9445–9451. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-28-09445.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ciccocioppo R, Martin-Fardon R, Weiss F, Massi M. Nociceptin/orphanin FQ inhibits stress- and CRF-induced anorexia in rats. Neuroreport. 2001;12:1145–1149. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200105080-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ciccocioppo R, Cippitelli A, Economidou D, Fedeli A, Massi M. Nociceptin/orphanin FQ acts as a functional antagonist of corticotropin-releasing factor to inhibit its anorectic effect. Physiol Behav. 2004;82:63–68. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2004.04.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ciccocioppo R, Panocka I, Froldi R, Colombo G, Gessa GL, Massi M. Antidepressant-like effect of ethanol revealed in the forced swimming test in Sardinian alcohol-preferring rats. Psychopharmacology. 1999;144:151–157. doi: 10.1007/s002130050988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Funk CK, O'Dell LE, Crawford EF, Koob GF. Corticotropin-releasing factor within the central nucleus of the amygdala mediates enhanced ethanol self-administration in withdrawn, ethanol-dependent rats. J Neurosci. 2006;26:11324–11332. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3096-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sommer WH, Rimondini R, Hansson AC, Heilig M. Upregulation of Voluntary Alcohol Intake, Behavioral Sensitivity to Stress, and Amygdala Crhr1 Expression Following a History of Dependence. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;63:139–145. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Koob GF. Alcoholism: allostasis and beyond. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2003;27:232–243. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000057122.36127.C2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Koob GF. A role for GABA mechanisms in the motivational effects of alcohol. Biochem Pharmacol. 2004;68:1515–1525. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2004.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hyytia P, Koob GF. GABAA receptor antagonism in the extended amygdala decreases ethanol self-administration in rats. Eur J Pharmacol. 1995;283:151–159. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(95)00314-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Roberts AJ, Cole M, Koob GF. Intra-amygdala muscimol decreases operant ethanol self-administration in dependent rats. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1996;20:1289–1298. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1996.tb01125.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Roberto M, Madamba SG, Moore SD, Tallent MK, Siggins GR. Ethanol increases GABAergic transmission at both pre- and postsynaptic sites in rat central amygdale neurons. Neuroscience. 2003;4:2053–2058. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0437926100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Veinante P, Stoeckel ME, Freund-Mercier MJ. GABA- and peptide-immunoreactivities co-localize in the rat central extended amygdala. Neuroreport. 1997;8:2985–2989. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199709080-00035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Day HE, Curran EJ, Watson SJ, Jr, Akil H. Distinct neurochemical populations in the rat central nucleus of the amygdala and bed nucleus of the stria terminalis: evidence for their selective activation by interleukin-1beta. J Comp Neurol. 1999;413:113–128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nie Z, Schweitzer P, Roberts AJ, Madamba SG, Moore SD, Siggins GR. Ethanol augments GABAergic transmission in the central amygdala via CRF1 receptors. Science. 2004;303:1512–1514. doi: 10.1126/science.1092550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mogil JS, Grisel JE, Reinscheid RK, Civelli O, Belknap JK, Grandy DK. Orphanin FQ is a functional anti-opioid peptide. Neuroscience. 1996;75:333–337. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(96)00338-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Heyser CJ, Roberts AJ, Schulteis G, Koob GF. Central administration of an opiate antagonist decreases oral ethanol self-administration in rats. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1999;3:1468–1476. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Perfumi M, Santoni M, Cippitelli A, Ciccocioppo R, Froldi R, Massi M. Hypericum perforatum CO2 extract and opioid receptor antagonists act synergistically to reduce ethanol intake in alcohol-preferring rats. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2003;27:1554–1562. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000092062.60924.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stromberg MF, Volpicelli JR, O'Brien CP. Effects of naltrexone administered repeatedly across 30 or 60 days on ethanol consumption using a limited access procedure in the rat. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1998;22:2186–2191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hyytiä P, Kiianmaa K. Suppression of ethanol responding by centrally administered CTOP and naltrindole in AA and Wistar rats. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2001;25:25–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2001.tb02123.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.