HIV is a major public health concern that disproportionately affects older Black women, and Black women between the ages of 50–64 comprised approximately 40% of the newly diagnosed cases in 2010 with heterosexual contact being the most common route of transmission (87%) (CDC, 2012). Nevertheless, there is a paucity of research focused on HIV sexual risk and protective behaviors that targets this vulnerable population (Jacob & Kane, 2011; Paranjape, Berstein, St. George, Doyle, Henderson, & Corbie-Smith, 2006). Data on sexual risk behaviors in older women are scarce because research has focused primarily on younger Black women (Cornelius et al, 2008; Jacobs, 2008). However, older Black women are sexually active and are more likely to engage in high-risk sexual behaviors than their younger counterparts (Mack, & Ory, 2003; Lindau, Leitsch, Lundberg, & Jerome, 2006). Cornelius, Moneyham, and Legrand (2008) assert that older Black women view condom use primarily as a form of contraception. Therefore, because older Black women are typically post-menopausal and not likely to become pregnant they may be less likely to use condoms as a form of protection from HIV and other sexually transmitted infections. Further, Sterk, Klein, and Elifson (2004) reported that older women have less experience with condoms than younger women.

Stampley, Mallory and Gabrielson (2005) conducted an integrative literature review, 1987–2003, that focused on HIV risk and prevention in midlife and older Black women (ages 40–65) and highlighted factors related to perceived vulnerability, socio-economics, sexual assertiveness, and risk taking behaviors. The integrative review provided important early insight regarding HIV risk in mid-life and older women. Therefore, to expand this body of literature, our study sought to provide a more current understanding of HIV sexual risk in Black American women over the age of 50.

Although 50 is chronologically defined as middle-aged, historical patterns purported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention stratifies individuals with HIV/AIDS into categories with individuals age 50 and older considered “older adults.” This age classification is further indicated in current HIV literature (CDC, 2012; Cornelius Moneyham, & Legrand, 2008; Emlet, Tozay, & Raveis, 2010) and for the purpose of this study “older women” will be denoted as age 50 and over.

The purpose of this systematic review was to appraise the current literature on HIV sexual risk practices in older Black women and to answer the question: What are the sexual practices in older Black women associated with HIV risk?

Methods

This systematic review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, Altman, et al., 2009).

Search Strategy

With guidance from an information specialist, a literature search was conducted using four electronic databases: CINAHL, PubMed, MEDLINE, and Web of Knowledge. Criteria for inclusion of articles were: quantitative and qualitative primary research studies published in English between January 1, 2003 and December 31, 2013. We aimed at identifying studies which focused on HIV sexual risk and protective practices among heterosexual older Black American women so we restricted our search of the population to the United States. As previously mentioned, older women are defined as age 50 and beyond. Abstracts, unpublished dissertations or other manuscripts and editorials and commentaries were excluded.

Initially two reviewers (TS, EL) mutually agreed upon appropriate search terminology and keywords that were deduced and culminated in results derived from the four databases. One reviewer independently screened abstract titles, which were then reviewed and confirmed by the second reviewer. Differences were resolved by discussion and consensus.

The literature search was conducted in three stages: 1) conducting the initial broad search of the literature; 2) screening titles and abstracts for inclusion/exclusion criteria; and 3) evaluating full-text articles deemed appropriate based on the screening process. EndNote X6 software was used for bibliographic management.

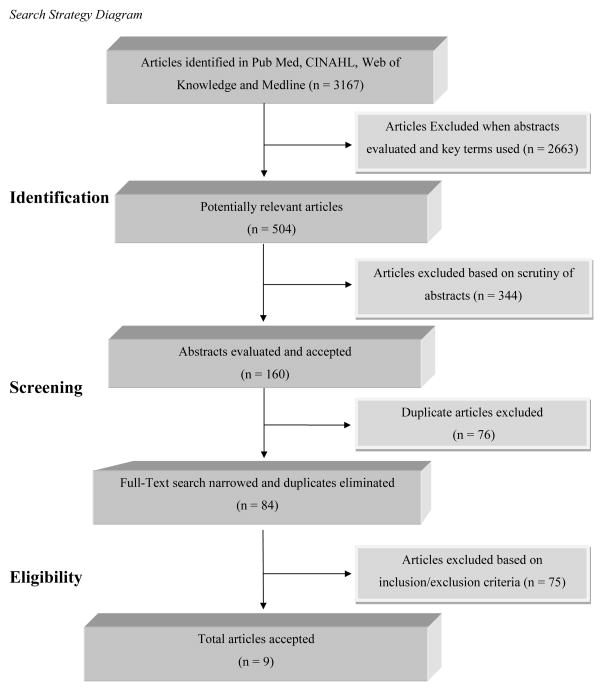

Initially, broad terms were combined such as “HIV risk” and “African American women” which yielded 3167 potential research articles of interest: CINAHL (N = 170), PubMed (N = 597), OVID Medline (N = 1333) and Web of Knowledge (N = 1067). The numbers of potentially relevant articles were then reduced to 504 when titles and abstracts were reviewed and more specific key terms were searched such as: “HIV sexual risk” and “older African American women,” “middle aged,” “HIV sexual risk behaviors,” “women’s health,” “unsafe sex,” “aged African American women,” “risk factors,” “Blacks,” and “older women.” Abstracts were scrutinized closely for relevance; 344 were excluded and 160 were accepted for evaluation. When search terms were narrowed and duplicate publications were eliminated the number of potentially relevant articles decreased to 84.

Upon further review of the 84 potentially relevant studies, 24 were eliminated because they provided data on HIV sexual risk-taking practices on women between the ages of 18–44. Ten additional studies were deleted due to lack of clarity regarding age parameters in the findings. For instance, although ten studies reported data on HIV sexual risk practices of ‘middle aged’ Black women, the findings did not distinguish between women in their 40s and those 50 years or older. Thirty studies were omitted because they focused exclusively on HIV knowledge and testing, or were HIV risk interventions and studies that included data on men at risk for HIV. Six studies were not published during the prescribed time frame, and 5 studies focused solely on older Black women who were already living with HIV. The final yield of full-text studies retained for analysis after the inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied, was 9 which included 2 studies retrieved from review of the reference lists. See corresponding search strategy diagram in Figure 1. Although one study was conducted on an ethnically diverse sample of older women already infected with HIV (Neundorfer et al., 2005), the authors of the study focused exclusively on the sexual risk factors for HIV as opposed to the lived experience of HIV within the target population; therefore, the study was retained for this analysis.

Figure 1.

Search Strategy Diagram

Data Analysis and Quality Assessment

Data from each study were summarized as follows: research purpose and design, theoretical framework, sample characteristics, measures used in the study, data analysis and the major research findings. The qualitative and quantitative studies were critically appraised using two assessment tools adapted from Web & Roe (2007) for qualitative studies and West and colleagues (2007) for quantitative designs. The adapted quality assessment tool by West et al. (2007) included seven major domains: abstract clarity; focused aim; description and consistency of the sample characteristic and study design; clarity of predictor variable and outcome measurements; appropriateness of the statistical analyses; clarity of results, and the presentation of the discussion including biases and limitations. Similar domain characteristics were adapted and incorporated for the qualitative analysis (Web & Roe, 2007) with minor variations in the data analysis and results domain.

We modified the quality assessment tools and appraised the studies based on 18 criteria to determine whether the studies adequately addressed each of the aforementioned components of the domains. These domain characteristics were evaluated and scored on a 2-point scale based on whether the studies (2) completely met (1), partially met, or (0) failed to meet each of the components and subcomponents of the domain. Inter-rater reliability was established based on a comparison between independently scored ratings. Consensus estimates were utilized whereby percentages were calculated by adding the points in each category of the individual items and dividing them by the total number of points and a summary score was produced (Stemler, 2004). Based on the assessed summary score, percentages were placed in one of three categories high (90–100%), medium (75–89%) or low (less than 75%). Quality scores within 2 points of each other were considered to be in agreement and the studies were retained for this systematic review. Scores with larger variations were evaluated by the authors to ensure the criteria were being interpreted similarly. The authors independently assessed the quality of the articles using the adapted appraisal tool and disagreements were resolved through dialogue and consensus. Based on the critical evaluation process of the articles, the results were ranked in terms of their level of impact. Studies received high scores if all of the components of the domains were fully addressed and low scores if they were not.

Results

All studies that met inclusion criteria were descriptive in nature: 8 used a quantitative cross-sectional design and 1 used a qualitative design. The characteristics and findings of the studies are summarized in Table 1. Established theoretical frameworks and models guided some of the studies (n = 4): AIDS Risk Reduction Model (AARM) (Winningham et al., 2004a), Health Belief Model (HBM) (Winningham et al., 2004b), Social Cognitive Theory and the Theory of Gender and Power (Jacob & Kane, 2011), and the Socio-ecological Framework (Jacob & Thomilson, 2009). The qualitative study by Neundorfer et al. (2005) used grounded theory and developed a model that assessed the risk factors for HIV among older women.

Table 1.

Study Characteristics and Quality Score

| Author | Purpose | Study Design | Sample | HIV Sexual Risk Measures | Data Analysis | Results | Quality Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jacob & Kane (2011) | To explore how self- esteem is related to other variables that may influence high risk sexual practices in women over 50 | Cross- sectional | Sample frames are the same for both Studies: Convenience sample of 572 women, mean age 63.6, ethnicity: Black 12.7%, White 58.9%, Hispanic 22%, from community sites in south Florida, setting: variety of community sites women’s clubs, hair salon, primary health clinics |

Predictors: Age, Ethnicity, Years in the US, Sensation Seeking Scale, Self-Silencing Scale, Sexual Assertiveness Scale, HIV Related Stigma Scale Outcome: Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale |

Linear Regression | Sensation seeking, self-silencing, sexual assertiveness, HIV stigma significant predictors of self-esteem (p < .05) | 87% |

| Jacob & Thomilson (2009) | To examine relationship between psychosocial variables and safer sex behaviors | Cross- sectional |

Predictors: Self- Silencing Scale Rosenberg, Self-Esteem Scale, Sensation Seeking Scale, Sexual Assertiveness Scale, AIDS Related Stigma Scale Outcome: Safe Sex Behavior Questionnaire |

Hierarchical multiple regression analysis | Negative association-silencing, stigma and condom use (p < .05) (p < .05). Age predictor of safe sex behavior |

87% | |

| Lindau, Leitsch, Lundberg, Jerome (2006) | To examine the effects of race and marriage on the sexual attitudes, behavior, and patient- physician communication about HIV among older women | Cross- sectional | Convenience sample of 55 women, median age 72, African American 31.5%, White including Hispanics 68.5%, from multiple inner city neighborhoods in Chicago using census tract data for racial and socioeconomic diversity | Variables: Recent sexual relationship and behaviors, attitudes about sexuality and HIV and patient- physician communication | Anova Chi-Square Fisher’s Exact Test |

Almost 60% of the single women reported they did not use condoms in their sexual relationships. African American women were more likely to report changes in their sexual behavior due to HIV risk |

80% |

| Neundorfer, Harris, Britton, Lynch (2005) | To examine stories of mid-life and older women to determine the risk factors that was associated with them contracting HIV | Qualitative | Purposive sample of 24 women, mean age 51, African American 58%, White 17%, Latina 17%, settings: from HIV outpatient clinics and social agencies-North East Metropolitan Area | Semi-structured questionnaires using an interview guide | Transcripts were read by two investigators, categories were made of risk factors that contributed to HIV exposure and themes emerged | 5 Themes: Risk factors that contributed to HIV exposure: 1) Drug and alcohol use, 71%; 2) Not knowing the HIV-risk histories of their sexual partner, 67%; 3) Mental health issues, 46%; 4) Engaged in high risk sexual behavior to maintain their relationship, 38%; 5) Lack of HIV prevention information, 38% | 93% |

| Paranjape, Bernstein, St. George, Doyle, Henderson & Corbie-Smith (2006) | To determine the effects of relationship factors on safe sex decision making in older Black women | Cross- sectional | Convenience sample, 514 women, mean age 59.4, ethnicity: African American 78%, White 1.9%, Hispanic .6%, from primary health clinics of large inner city hospitals |

Predictors: Series of relationship factor questions: Hobfoll (1993) Outcomes: Two questions: In your current relationship: 1) how do you define your sexual activity? 2) Do you use condoms during sexual activity? |

Multivariate Logistic regression | Women who trusted their partner were less likely to report safe sex (OR = 0.3) Women who obtained condoms were more likely to report safe sex practices (OR = 12.3) Safe sexual practices were more common among women who depended on their partners for condoms (OR = 9.2) |

90% |

| Sormanti & Shibusawa (2007) | To examine predictors of HIV sexual risk factors among midlife and older women seeking medical services | Cross- sectional | Convenience sample of 1, 280 women, mean age 56, Hispanics 52%, Black 38%, Whites 4%, Participants were recruited from multiple sites: from an emergency room and several outpatient primary health clinics servicing underserved populations in the northeast region |

Predictors: Relationship status: questions within the past 2 years Outcomes: Sexual risk factors: questions within the past 6 month, HIV testing |

Multiple logistic regression | Condom use was associated with: more years of education, not living with a partner, being HIV positive, being younger, living alone, and being recruited from the ER (p < .05) | 87% |

| Sormanti, Wu, El-Bassel (2004) | To examine association between experiencing Intimate partner violence in a primary heterosexual relationship and HIV risk behaviors | Cross- sectional | Convenience sample of 139 women, mean age 55, African Americans 44%, Latina 56%, settings: participants were recruited from multiple primary outpatient health clinics of larger urban hospitals servicing predominantly low- income communities in NYC |

Predictors: HIV risk perception: single item, Intimate Partner Violence Outcome: Sexual Risk Behavior Questionnaire |

Binary Logistic Regression | 86% women reported no condom-use with their main partner in the past 3 months, 15% had multiple sex partners in past year. Women reporting multiple sexual partners were: younger (p < .01), African American vs. Latina (OR = 4.8) African American women were more likely than Latinas to report life time intimate partner violence (OR = 3.3) and more likely to report current Intimate Partner Violence (OR = 4.5) |

90% |

| Winningham, Corwin, Moore, Richter, Sargent, Gore-Felton (2004a) | To examine theoretical predictors associated with HIV risk behavior among older African American women | Cross- Sectional | Convenience sample of 181 women, mean age 58, African American 100%, setting: surveys were conducted in churches and subjects’ homes and subjects’ were from three rural counties in South Carolina |

Predictors: Perceived Susceptibility Scale, Self-Efficacy Scale, Partner Communication Scale Outcome: Sexual risk behaviors during the past 5 years: five questions |

Hierarchical logistic regression | 60% women engaged in at least 1 of 5 sexual risk behaviors in the past 5yrs, 48% admitted to having more than 1 sex partner in the past 5yrs, 26% admitted their partner was having sex with other women, 12% reported their partner was having sex with men. Condom use self- efficacy was higher with women who reported lower sex risk behavior (p < .05). Women at lower HIV risk were more likely to report comfort sexual communication with partners |

83% |

| Winningham, Richter, Corwin, Gore- Felton (2004b) | To explore factors associated with perceived vulnerability to HIV among older African American women | Cross- Sectional | Convenience sample of 167 women, age range from 50–81, ethnicity: African American, from three rural counties in South Carolina, Settings: churches and subjects’ homes |

Predictors: Partner approval: Single item measure, Partner-risk behaviors, Self-risk behaviors, Partner Communication Scale, response efficacy Outcome: Perceived Vulnerability Scale |

Hierarchical linear multiple regression | Greater perceived vulnerability to HIV were associated with: women who were not married/living with a partner, women who had more comfort in communication with their partners about sex (p < .05). Lower perceived vulnerability to HIV was associated with partner approval for condom use (p < .05) | 87% |

Eight of the studies used convenience sampling; one used purposive sampling (Neundorfer et al., 2005). All of the studies had small to moderate sample sizes (range: 24 to 1,280) and none provided a power analysis. While the samples varied in ethnicity and race, more than half of the studies focused predominantly on older Black women. Most of the sample populations were recruited from large urban communities (n = 7) in New York City, Chicago, and South Florida, and two studies were conducted in rural communities in South Carolina (Winningham et al., 2004a; 2004b). Most of the studies (n = 6) received a medium quality score which ranged from 80–87% and only three studies scored high (90–93%) (Table 1).

Sexual Practices

All studies consistently identified at least one of three major variables that contribute to HIV sexual risk practices in Black women: behavioral (inconsistent condom use and multiple sexual partners), psychological (risk perception, depression/stress, trauma, and self-esteem issues), and social factors (economics, education, and drugs/alcohol-use) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Major Variables Identified which Contribute to HIV Sexual Risk Practices

| 1st Author (Year) |

Behavioral Factors | Psychological Factors | Social Factors | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||||||

| Multiple Sexual Partnerships | Inconsistent Condom Use | Risk Perception | Self- Efficacy | Mental Health Factors/Trauma | Communication | Economics | Education | Drug/Alcohol Abuse | |

| Jacob (2009) | X | ||||||||

| Jacob (2011) | X | ||||||||

| Lindau (2006) | X | ||||||||

| Neundorfer (2005) | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Parnjape (2006) | X | X | |||||||

| Sormanti (2007) | X | X | X | ||||||

| Sormanti (2004) | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Winningham (2004a) | X | X | X | ||||||

| Winningham (2004b) | X | X | X | ||||||

Behavioral Factors

Inconsistent condom use

Five studies reported that Black women are sexually active and do engage in high risk sexual practices (e.g., unprotected sex). Paranjape and colleagues (2006) examined HIV sexual risk factors among 155 older women (approximately 80% Black) and found that although 81% of the women were sexually active while only 13% practiced consistent condom use. In addition, of the women who reported safer sexual behaviors, only 18% knew that condoms were effective in preventing HIV transmission. Likewise, Sormanti and Shibusawa (2007) found that although 73% of 623 ethnic minority women (approximately 40% Black) reported having vaginal sex in the past 6 months, only 12% reported consistent condom use. Further, Sormanti and colleagues (2004) found that almost 90% of the older ethnic women (nearly 50% Black) never used condoms with their primary partners in their recent sexual encounters (Sormanti et al., 2004).

The studies in this review collectively explicated many factors that were contributory to inconsistent condom use among older Black women. Neundorfer and colleagues (2005) conducted a qualitative study with 24 older women (approximately 60% Black) to determine the practices that placed these women at risk for HIV and found that nearly half of the women reported they were unaware of their risk for HIV and lacked HIV prevention education. Inconsistent condom use in this population may also be compounded by relationship factors. Older Black women tended to be married or in long-term relationships (Winningham et al., 2004a; Jacobs & Thomilson, 2009) and were less likely to use condoms with their primary sexual partners.

Other relationship factors contributing to high risk sexual practices (e.g., inconsistent condom use) included: trust in partners’ fidelity (Paranjape et al., 2006), lack of power in the relationship and fear of violence (Sormanti et al., 2004) and difficulty negotiating or asserting safer sexual practices (Jacobs & Thomlison, 2009; Sormanti et al., 2004). These findings are consistent with one of the themes from the qualitative study (Neundorfer, et al., 2006) that purports that 38% of the older women engaged in unprotected sexual behaviors to maintain their intimate relationship. Many of the women in the ethnically diverse qualitative study stated that being older with limited dating opportunities affects their decision to engage in risk-taking sexual activities (e.g., inconsistent condom use). For instance, one participant expressed concerns regarding relationship loss stating, “Older women are happy if someone wants to look at them. At our age I wonder if I am going to find someone” (Neundorfer, et al., 2006, p. 623).

Multiple sexual partners

Sormanti, Wu, and El-Bassel (2004) examined HIV risk and intimate partner violence among older Black and Latina women. This was the only study that found a small percentage (15% of 139) of the women who reported having multiple sexual partners. The two characteristics identified among these women were that they tended to be Black and significantly younger (p < .01) (Sormanti et al., 2004). Similarly, Jacobs and Thomilson (2009) reported that older women were more likely to be in monogamous relationships and less likely to use condoms with their primary sexual partner (Jacobs & Thomlison, 2009). Further, multiple sexual partnerships among older women were attributed to partner related risk factors (e.g., having a partner with multiple sexual partners) (Neundorfer et al., 2005; Sormanti et al., 2004; Winningham et al, 2004a; 2004b).

Winningham et al. (2004a) evaluated the sexual risk practices among 181 older Black women living in the rural south and found that although 67% of older Black women were in committed, sexual relationships, 26% reported that their sexual partners were having sex with other women, and 12% reported that their partners were having sex with men. Similarly, Neundorfer et al. (2005) found that most of the women in their study (approximately 70%) were not aware of the HIV history of their sexual partners or that their long-term partner contracted HIV as a result of multiple sexual partnerships with females or males. One woman was infected with HIV from her husband and discussed her view on multiple sexual partnerships, stating: “I knew that he was probably messing around with women, but I never thought he was messing around with guys” (Neundorfer et al., 2005, p. 622).

Winningham and associates (2004b) examined perceptions of HIV vulnerability among older Black women (n = 167) and the sexual behaviors of their intimate partners and found that perceptions of HIV risk were strongly associated with their partners’ risk behaviors. The partners’ HIV-related risk behavior varied from having sex with multiple women (77%) to having sex with multiple men (33%) as well as other related health factors (e.g., intravenous drug use). Thus, there seems to be a consistent trend in the aforementioned studies regarding partner-related risk factors (e.g., multiple sexual partners) influencing older Black women’s HIV-related sexual risk practices.

Psychological Factors

HIV sexual risk practices of older Black women were also associated with psychological and/or social factors in eight of the studies. Three studies identified the association between HIV risk perception and sexual practices (protective or risk-taking behavior) among older Black women (Neundorfer et al., 2005; Sormanti et al., 2004; Winningham et al., 2004b). Winningham et al. (2004b) noted that more than half of the women who reported a self-risk behavior (e.g., multiple sexual partners) perceived themselves to be at lower risk for HIV than those who did not report self-risk behavior (p < .001). In addition, a third of the women in their study reported a lower perceived risk for HIV, as compared with women who did not report risk-taking sexual behaviors, even though they were in relationships with partners who engaged in risky sexual practices. The authors also found that lower perceptions of HIV risk were associated with marriage/steady partnerships and partner approval of condom use in the sexual relationship.

Similarly, Neundorfer et al. (2005) found that about two-thirds of the women who were in long-term relationships did not use condoms because they did not perceive themselves as being at risk for HIV, but were subsequently infected with HIV. Women who perceive that they are at risk for HIV may alter their high risk sexual practices (Neundorfer et al., 2005; Winningham et al., 2004b). However, research findings on women’s risk perception were not entirely consistent. Paranjape and colleagues (2006) compared women who practiced safe sex to those who did not and found no significant difference in risk perception between groups. The authors reported that both groups of women had a high perception of risk for HIV and attributed that finding to social factors such as living in low income communities with high HIV sero-prevalence.

Two studies examined the influence of self-efficacy and its relationship to the sexual practices of older Black women. Winningham et al. (2004a) found self-efficacy to be higher among women who practiced safe sexual behaviors, which is consistent with the findings of Paranjape et al. (2006) that indicated women who obtained their own condoms were more likely to report consistent condom in their current sexual relationship.

Neundorfer and associates (2005) identified mental health factors associated with childhood trauma, intimate partner violence (IPV), and related life stressor as contributory factors for HIV sexual risk practices among 46% (n = 24) of the women in their study. Likewise, Sormanti et al. (2004) examined the relationship between IPV and HIV risk behaviors among older women of color and found that women who reported history of IPV were more likely to engage in risky sexual behaviors (e.g., multiple sexual partnerships). In this study, Black women were more likely to report lifetime and current IPV than women of other ethnicities. Further, older Black women in this study who were in relationships with men with known HIV risk were more likely to report a history of IPV (Sormanti et al., 2004). Self-esteem was also associated with high risk sexual behaviors among older women. Jacobs and Kane (2011) conducted a study with 572 multiethnic women and found that women with low self-esteem were less likely to be sexually assertive or communicate their need for safe sex in the intimate relationship.

Three studies examined communication and sexual decision making in relation to high risk sexual practices among older Black women (Jacobs & Kane, 2011; Jacobs & Thomilson, 2009; Winningham et al., 2004a) and consistently found that high-risk sexual behaviors were associated with women’s decreased comfort level discussing safe sex with their partners. Two studies described communication in the sexual relationship as ‘self-silencing’ (Jacobs & Kane, 2011; Jacobs & Thomilson, 2009), the way in which women keep silent or suppress their voice, thoughts and abilities to negotiate safer sex practices with their sexual partners. Jacobs and Kane (2011) examined self-silencing and age and found that they were both strong predictors of safe sexual behaviors among women; women aged 60 years and beyond who communicated their sexual needs and desires were more likely to practice safe sex in their intimate relationship. However, only 12.7% of the (n = 572) participants were Black.

Social Factors

Several studies found that Black women in impoverished communities were at greatest risk of developing HIV (Jacobs & Thomlison, 2009; Winningham et al., 2004). Winningham et al. (2004a) found that risky sexual behaviors were associated with limited education and Sormanti and Shibusawa (2007) reported that consistent condom use was directly associated with higher education and employment. Drugs and alcohol were other social factors identified as influential for HIV sexual risk in older Black women. Neundorfer et al. (2005) reported that alcohol and drug abuse were the most prevalent risk factor contributing to HIV risk behaviors; 71% (n = 24) of women in their study reported that intravenous drug use and risky sexual behavior contributed to them contracting HIV. Similarly, Sormanti, Wu and El-Bassel (2004) found that HIV sexual risk behaviors were significantly associated with intravenous drug use by older women and/or their partners’ risk behaviors.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the only current systematic literature review that evaluated the sexual risk practices of older Black women in regards to HIV transmission. The findings suggest consistent patterns and highlight behavioral, psychological, and social factors that contribute to the HIV sexual risk practices of older Black women. Although similar to some of the findings of Stampley, Mallory and Gabrielson (2005), our review consolidates information in regards to the multifaceted complex factors influencing older Black women’s risk for HIV and provides a basis for future HIV risk prevention research. While the purpose of this review was to examine the sexual risk practices of older Black women, only 7 studies focused on the outcome variables related to sexual risk practices (multiple sexual partnerships and inconsistent condom use). The other studies described the psychosocial and contextual factors that mitigate or improve the sexual risk behaviors of older Black women.

The results of this study confirmed that older Black women are engaged in risk-taking sexual behaviors. These behaviors may be explained by some of the individual-level variables identified in this study. For instance, older Black women did not perceive their own risk for HIV and their beliefs were associated with lack of HIV awareness, monogamy and other relational factors. This corresponds with the findings in existing literature which propose that knowledge deficit of HIV risk and low perceived susceptibility to HIV are barriers to HIV prevention efforts as it makes it difficult for older Black women to enact self-protective behaviors (Corneille et al., 2008; Young, Salem, & Bybee, 2010; Zablotsky & Kennedy, 2003). Lack of knowledge regarding HIV risk in this population may be ascribed to the notion that their formal education preceded the emergence of the HIV epidemic and the sexual education that followed it

However, relational factors, including trust in the relationship, may also play a crucial role in older Black women’s lack of HIV awareness or perceived susceptibility to HIV (Whyte, Whyte, & Cormier, 2008). One finding in this study indicated that the majority of the women in long-term relationships with their primary partners were not aware of their risk for HIV and were consequently infected with HIV by their partners (Neundorfer et al., 2005). This finding is consistent with prior research that asserts that older Black women in committed relationships with their main partners were more likely to engage in unprotected sexual activities than those who were in casual relationships (Tawk, Simpson, & Mindel, 2004; Zablotsky & Kennedy, 2003). This may indicate that trust may be an adaptive process linked to inconsistent condom use because of an older Black woman’s strong desire to maintain her relationship and/or avoid the perception of infidelity. If there is no perceived threat for HIV transmission in the sexual relationship, precautionary health outcomes are less likely to occur.

As specified in this study, HIV acquisition in older Black women, in regards to multiple sexual partnerships, was found to be mostly a function of men not disclosing their sexual risk-taking behaviors (e.g., multiple sexual partnerships) to their female sexual partners (Jacob & Thomilson, 2009). This study also revealed that even when some women were aware of their partner’s extra-relational sexual risk behaviors they still engaged in unprotected sexual activities. Therefore, given the current epidemiological profile of HIV among older Black women (CDC, 2012), it is imperative that nurses, doctors and other health care providers examine the impact of relational factors, including partners’ risk, among older Black women as a potential contributor to high-risk sexual practices. This heath assessment is needed in order to develop age-appropriate interventional programs to combat known barriers to sexual protection.

Another aspect of low perceived risk among older Black women is how it influences behavior within the context of social norms. Many older Black women are also at greater risk for HIV because they are in a long-term sexual relationship with men who have non-disclosed, extra-relational sex with men. Social norms often stigmatize homosexuality and a study found that Black men were less likely than White men to identify themselves as being homosexual or bisexual for fear of being marginalized in their community (O’Leary, Fisher, Purcell, Spikes, & Gomez, 2007). Non-disclosure contributes to the continuation of unsafe sexual practices and the high rates of HIV among older heterosexual Black women (Whyte et al., 2008). Further research is warranted on stigma and nondisclosure of sexual behavior in Black men in order to develop effective strategies aimed at decreasing the overall incidence of HIV among Black women.

This study also highlighted other relationship factors that may contribute to HIV sexual risk behaviors among older Black women including power imbalances in the relationship, IPV, ineffective communication and/or difficulty negotiating sexual protective needs (Paranjape et al., 2006; Sormanti et al., 2004; Jacobs & Thomlison, 2009). However, these factors are complex in nature and should be viewed within the broader social and cultural context of health in this vulnerable population. Consistent with previous literature, social and cultural factors including sex-ratio and gender power imbalances may influence women’s intentions to use condoms consistently (Woolf & Maisto, 2008). Black women who perceived that there were fewer eligible Black men were more likely to perceive less power in their heterosexual relationships (Corneille, Zyzniewsk, & Belgrave, 2008; Jarma, Belgrave, Bradford, Young, & Honnold, 2010). The sex-ratio imbalances in the Black community may impact women’s ability to communicate or negotiate for condom use with their intimate male partners. With fewer available male partners, Black men have more options available which may interfere with women’s ability to initiate communication regarding their needs for sexual protection due to fears of losing the relationship (Corneille et al., 2008; Jarma et al., 2010; Jacob, 2008).

Low socio-economic status was a social contributing factor that was emphasized in this study and was associated with HIV risk among older Black women which confirms the findings of existing literature. Black women who live in impoverished communities are at the greatest risk for developing HIV (Adimora, Schoenbach, & Floris-Moor, 2009). In the U.S., the HIV sero-prevalence rates tend to be higher in urban, low income communities where poverty, crime and drug addiction are pervasive (Levy, Ory, & Crystal, 2003; US Census Bureau, 2010).

This study also indicated that childhood trauma, IPV and other mental health issues may influence risk-taking sexual practices among older Black women and lead to HIV acquisition. Research documents the link between childhood sexual abuse, IPV and risky sexual behavior among Black women (El-Bassel, Calderia, Ruglass, Gilbert, 2009; McNair & Prather, 2004).

There were a few noteworthy limitations in this study. As in any literature review, it is possible that relevant manuscripts were missed, particularly since the search was limited to publications only in English. Studies reviewed were small in number and designs were cross-sectional and correlational; therefore, no causal inferences can be drawn nor was a meta-analysis possible. Studies were inconsistent in how variables were measured, participants were selected primarily by convenience and hence it is not possible to assess generalizability and representativeness of the findings. There were only four studies that were guided by a theoretical framework and this lack of theory-based research may be associated with some of the inconsistencies in findings. In studies that fail to report a theoretical frame work, it may be difficult to articulate the conceptual rationale for the study variables.

Finally, several studies included ethnic and racial groups other than elder Black women. While it is important to examine the sexual risk practices across ethnicities, older Black women are at greatest risk for HIV and future studies should focus primarily on the target population and note the intra-cultural disparities. In addition, future research is needed to explore the relationship between IPV, childhood trauma and other mental health issues in relation to HIV sexual risk as well as the social, economic and cultural predictors for HIV risk behaviors among older Black women. In addition, research should also explore the primary male sexual partners’ risk influencing women’s HIV sexual risk practices. Despite these limitations, this study achieved its purpose and contributes to the knowledge base of identifying the individual and psychosocial and cultural factors influencing the HIV sexual risk behaviors of older Black American women.

Implications for Practice and/or Policy

The findings of this systematic review suggest that many older Black women are engaged in sexual risk-taking behaviors and are vulnerable to contracting HIV. This study has implications for clinical practice, research, and policy. The health care needs of older black women are unique and clinical approaches must be developed that take into consideration their distinct individual, psychosocial, and cultural characteristics. Some of the major highlights of this study related to older Black women’s HIV risk were perceived HIV risk, communication, condom-negotiation, sexual decision-making, and relationship factors.

Many of the women in this study indicated that they were monogamous, in long-term heterosexual relationships and did not perceive their susceptibility for HIV. Nurses and other health providers can communicate with older Black women to clarify the facts of HIV transmission and risk and assist in accurate self-appraisal of their risk. Further, this study highlighted women’s perceptions of their partners’ risk factors for HIV. Thus, health educational messages and programs should be created to empower older Black women to determine their partners’ trustworthiness and risk for HIV as this may lead to sexual protective practices. One effective HIV prevention effort could be to offer HIV testing to all older Black women, which is consistent with the 2006 CDC recommendations for individuals up to the age of 65 (CDC, 2012). Thus, the health care provider should also educate the patient on the importance of HIV partner testing before initiating sexual contact as well as help Black women recognize the signs that their partners may be at risk for HIV (e.g. drug abuse, multiple sexual partners) and teach them how to effectively communicate their sexual needs and condom negotiation skills to effect safer sexual decisions (Neundorfer et al., 2005).

The results of this systematic review indicated that IPV and trauma were associated with HIV risk in older Black women. Studies have found that skill-building interventions were efficacious in reducing HIV risk behavior in Black women who were exposed to childhood sexual trauma (El-Bassel et al., 2009; Wyatt et al., 2004). It is necessary for nurses and other clinicians to develop strategies that will teach skills in communication and condom negotiation as well as ways to identify and avoid IPV relationships. These skills will help to increase condom use and reduce risk taking behavior, thereby reducing HIV and STI rates.

Thus far, efforts to reduce the risk of HIV among older Black women remain abysmal and to our knowledge there have been no randomized controlled experimental studies on HIV risk reduction targeting this population. This limits our ability to make causal inference regarding HIV prevention interventions tailored to the needs of older Black women. Clinical trials and intervention strategies continue to predominately focus on younger Black women without consideration of the feasibility of the target population (Cornelius et al., 2008). It is imperative that future HIV research include randomized controlled clinical trials to ensure that efficacious, age-appropriate intervention programs are designed and implemented to prevent the spread of HIV among this vulnerable population.

Additionally, HIV interventions for older Black women will require a multiple level approach that goes beyond the individual level to include the sexual dyad, organizational, community and policy. First, relationships occur within the context of a dyad, and couple-based interventions may create a safe environment for older Black women to communicate their HIV protective sexual needs with their partners (Jacob, 2008; McNair & Prather, 2004). Second, organizational interventions are needed that target older Black women and should include implementing faith-based interventions and educational messages on HIV risk reduction given the importance of the role of the church in the Black community (Coon, Lipman, & Ory, 2003; Cornelius et al., 2008; El-Bassel, et al, 2009). Next, health interventions at the community level are needed to increase HIV and STI awareness among older Black women. These community interventions may be comprised of media campaigns and community level seminars that specifically target older Black women and includes messages of safe senior sex and condom negotiation and training. Finally, health interventions that impact policy may include establishing local and national HIV prevention advocacy groups (Coon, Lipman, & Ory, 2003; Cornelius et al., 2008; El-Bassel, et al, 2009). Further, establishing HIV prevention policies for older Black women through theory-based, culturally relevant research that targets eliminating ageism regarding sex, IPV, and power differentials between men and women is an area for future research.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors report no real or perceived vested interests that relate to this article that could be construed as a conflict of interest.

Authors’ Certification:

I certify that this material has not been published previously and is not under consideration by another journal. I further certify that I have had substantive involvement in the preparation of this manuscript and am fully familiar with its content.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Dr. Tanyka K. Smith, Postdoctoral Research Fellow at Columbia University School of Nursing, 617 West 168th Street, New York, NY 10032, (Cell) 347-224-5351, (Work) 212-342-0851, (Fax) 212-305-0723. Dr. Smith was supported as a postdoctoral trainee by the National Institute of Nursing Research, National Institutes of Health (Training in Interdisciplinary Research to Prevent Infections, T32 NR013454).

Dr. Elaine Larson, Email: Ell23@columbia.edu, Anna C. Maxwell Professor of Nursing Research and an Associate Dean for Nursing Research at Columbia School of Nursing. She is also Professor of Epidemiology, at Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health and an Editor for the American Journal of Infection Control. Dr. Larson’s contact information: 617 W. 168th St, Room 330 New York, NY 10032, 212-305-0723, Fax: 212-305-0722.

References

- Adimora AA, Schoenbach VJ, Floris-Moore MA. Ending the epidemic of heterosexual HIV transmission among African Americans. American Journal of Preventative Medicine. 2009;37:468–471. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.06.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Diagnoses of HIV Infection among adults aged 50 years and older in the United States dependent Areas 2007 –2010. 2012 Retrieved on November 15, 2013 from http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/statistics_2010_HIV_Surveillance_Report_vol_18_no_3.pdf.

- Coon DW, Lipman PD, Ory MG. Designing Effective HIV/AIDS Social and Behavioral Interventions for the population of those age 50 and older. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome. 2003;33:S194–S205. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200306012-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corneille MA, Zyzniewski LE, Belgrave FZ. Age and HIV risk and protective behavior among African American women. Journal of Black Psychology. 2008;34:217–233. [Google Scholar]

- Cornelius JB, Moneyham L, LeGrand S. Adaptation of an HIV curriculum for use with older African American women. Journal of Association in AIDS Care. 2008;19:16–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2007.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Bassel N, Caldeira NA, Ruglass LM, Gilbert L. Addressing the unique needs of African American women in HIV prevention. American Journal of Public Health. 99:996–1001. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.140541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs RJ. Theory-based community practice for HIV prevention in midlife and older women. Journal of Community Practice. 2008;16:403–421. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs RJ, Kane MN. Theory-based policy development for HIV prevention in racial/ethnic minority midlife and older women. Journal of Women Aging. 2011;21:19–32. doi: 10.1080/08952840802633586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs RJ, Thomilson B. Self-silencing and age as risk factors for sexually acquired HIV in midlife and older women. Journal of Aging and Health. 2009;21:102–128. doi: 10.1177/0898264308328646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarama SL, Belgrave FZ, Bradford J, Young M, Honnold JA. Family, cultural and gender role aspects in the context of HIV risk among African American women of unidentified HIV status: An exploratory qualitative study. AIDS Care. 2010;19:307–317. doi: 10.1080/09540120600790285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy JA, Ory MG, Crystal S. HIV/AIDS interventions for midlife and older adults: Current status and challenges. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome. 2003;33:S59–S67. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200306012-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindau DT, Leitsch SA, Lundberg KL, Jerome J. Older women’s attitudes, behavior, and communication about sex and HIV: A community-based study. Journal of Women’s Health. 2006;15:747–753. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2006.15.747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mack KA, Ory AIDS and older Americans at the end of the twentieth century. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2003;33:S68–S75. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200306012-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNair LD, Prather CM. African American women and AIDS: Factors influencing risk and reaction to HIV disease. Journal of Black Psychology. 2004;30:106–123. [Google Scholar]

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG the Prism Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Physical Therapy. 2009;89:878–880. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Napper LE, Fisher GD, Reynolds GL, Johnson ME. HIV risk behavior self- report reliability at different recall periods. AIDS Behavior. 2010;14:152–161. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9575-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neundorfer MM, Harris PB, Britton PJ, Lynch DA. HIV risk factors for midlife and older women. The Gerontologist. 2005;45:617–625. doi: 10.1093/geront/45.5.617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Leary A, Fisher HH, Purcell DW, Spikes PS, Gomez CA. Correlates of risk patterns and race/ethnicity among HIV positive men who have sex with men. AIDS and Behavior. 2007;11:706–715. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9205-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paranjape A, Bernstein L, St George MD, Doyle J, Henderson S, Corbie-Smith G. Journal of Women’s Health. 2006;15:90–97. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2006.15.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sormanti M, Shibusawa T. Predictors of condom use and HIV testing among midlife and older women seeking medical services. Journal of Aging Health. 2007;19:705–719. doi: 10.1177/0898264307301173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sormanti M, Wu E, El-Bassel N. Considering HIV risk and intimate partner violence among older women of color: A descriptive analysis. Women and Health. 2004;39:45–63. doi: 10.1300/J013v39n01_03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stampley CD, Mallory C, Gabrielson M. HIV/AIDS among midlife African American women: An integrated review of literature. Research in Nursing & Health. 2005;28:295–305. doi: 10.1002/nur.20083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stemler SE. A comparison of consensus, consistency, and measurement approaches to estimating inter-rater reliability. Practical Assessment, Research & Evaluation. 2004;9:66–78. [Google Scholar]

- Sterk CE, Klein H, Elifson KW. Self-esteem and “at risk” women: Determinants and relevance to sexual and HIV-related risk behaviors. Women & Health. 2004;40:75–92. doi: 10.1300/j013v40n04_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tawk H, Simpson J, Mindel A. Condom use in multi-partnered females. International Journal of STD and AIDS. 2004;14:405–432. doi: 10.1258/095646204774195263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. Census Data for the State of New York. 2010 Retrieved from http:/www.census.gov/2010census.

- Web C, Roe B. Reviewing research evidence for nursing practice. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing Ltd; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- West S, King V, Carey TS, Lohr KN, Mckoy N, Sutton SF, Lux L. Systems to rate the strength of scientific evidence. Evidence Report Technology Assessment Summary. 2002;47:1–11. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whyte J, Whyte MD, Cormier E. Down low sex, older African American women, and HIV infection. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care. 2008;19:423–431. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2008.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winningham A, Corwin S, Moore C, Richter D, Sargent R, Gore-Felton C. The changing age of HIV: Sexual risk among older African American women living in rural communities. Preventive Medicine. 2004a;39:809–814. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winningham A, Ritcher D, Corwin S, Gore-Felton C. Perceptions of vulnerability to HIV among older African American: The role of intimate partners. Journal of HIV/AIDS and Social Services. 2004b;3:25–42. [Google Scholar]

- Wyatt GE, Longshore D, Chin D, Carmona JV, Loeb TB, Myers HF, et al. The efficacy of an integrative risk reduction intervention for HIV-positive women with child sexual abuse histories. AIDS and Behavior. 2004;8:453–462. doi: 10.1007/s10461-004-7329-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young SN, Salem D, Bybee D. Risk revisited: The perception of HIV risk in a community sample of low-income African American women. Journal of Black Psychology. 2010;36:49–74. [Google Scholar]

- Zablotsky D, Kennedy M. Risk factors and HIV transmission to mid-life and older women: Knowledge, options, and the initiation of safer sexual practices. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome. 2003;33:122–133. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200306012-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]