Abstract

OBJECTIVE

Prior studies suggest that ligament and meniscus tears cause osteoarthritis (OA) when changes in joint kinematics bring underused and underprepared regions of cartilage into contact. This study aims to test the hypothesis that material and tribological properties vary throughout the joint according to the local mechanical environment.

METHOD

The local tribological and material properties of bovine stifle cartilage (N=10 joints with 20 samples per joint) were characterized under physiologically consistent contact stress and fluid pressure conditions.

RESULTS

Overall, cartilage from the bovine stifle had an equilibrium contact modulus of Ec0=0.62±0.10MPa, a tensile modulus of Et=4.3±0.7MPa, and a permeability of k=2.8±0.9×10−3 mm4/Ns. During sliding, the cartilage had an effective friction coefficient of μeff =0.024±0.004, an effective contact modulus of Ec=3.9±0.7MPa and a fluid load fraction of F′=0.81±0.03. Tibial cartilage exhibited significantly poorer material and tribological properties than femoral cartilage. Statistically significant differences were also detected across the femoral condyle and tibial plateau. The central femoral condyle exhibited the most favorable properties while the uncovered tibial plateau exhibited the least favorable properties.

CONCLUSIONS

Our findings support a previous hypothesis that altered loading patterns can cause OA by overloading underprepared regions. They also help explain why damage to the tibial plateau often precedes damage to the mating femoral condyle following joint injury in animal models. Because the variations are driven by fundamental biological processes, we anticipate similar variations in the human knee, which could explain the OA risk associated with ligament and meniscus tears.

Keywords: Articular Cartilage, Bovine, Friction, Osteoarthritis, Knee

1. Introduction

Anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) ruptures and meniscal tears are among the known risk factors for osteoarthritis (OA). The increased risk of OA under these conditions has been attributed to altered joint kinematics, which includes increased stresses, abnormal motions, unfavorable muscle adaptations, and new cartilage contact patterns 1, 2. Andriacchi et al. found that ACL deficiency in humans causes a shift in contact location2. They hypothesize that these kinematic shifts can initiate OA when they initiate contact in areas that are unaccustomed to or otherwise functionally underprepared for normal tribological contact stresses; we call this the ‘altered loading’ hypothesis hereon. Previous animal model studies appear to support this hypothesis. Bendele, for example, found that medial meniscus transection in a rat model caused nearly immediate fibrillation on the tibial plateau3, but had no damaging effect on the mating condylar cartilage until far later in disease progression. This observation suggests that the two tissues respond differently to the same tribological stresses. Furthermore, damage consistently occurred at a specific location (outer third of the surface). This suggests that the region normally covered by meniscus may be functionally underprepared compared to areas that contact the femoral condyle in a healthy joint.

Several studies have demonstrated that properties of cartilage vary systematically. Ebara et al. showed that the tensile stiffness of bovine humeral cartilage was significantly higher than that of bovine glenoid cartilage4. Akizuki et al. showed that the tensile modulus of human cartilage was higher for the patellar groove than the femoral condyle5 while Mow et al. showed that the aggregate modulus of bovine cartilage was higher on the lateral condyle than on the patellar groove6. Others have shown that cartilage properties, namely thickness, vary systematically across a single surface in the human knee. Generally, the regions of highest contact pressures7 and direct cartilage-cartilage contact (as opposed to interposed meniscus)6, 8, 9 are thickest. The cartilage shielded by the meniscus is correspondingly thinner and has a higher aggregate modulus than the cartilage not shielded by meniscus6. These results indicate that properties reflect the local mechanical spectrum in the healthy joint and support the altered loading hypothesis of OA2.

Despite strong evidence that material properties of cartilage vary in response to the local mechanical environment of the healthy joint, there is no direct experimental evidence to suggest that tribological properties vary concurrently. In fact, most studies of tribological properties do not report the sample extraction location from the surface of interest 10–12, which implies location-independence. It is known, however, that interstitial lubrication depends on biphasic material properties13. For example, Ateshian and Wang 14 and Li et al. 15 used biphasic theory to show that thickness and aggregate modulus should theoretically affect tribological function. It is therefore reasonable to expect that tribological properties also vary according to the local mechanical environment of the healthy joint.

Although location-specific tribological properties have significant implications for our understanding of the OA, it remains unclear if and to what extent such variations exist. This paper aims to establish the location-specific functional properties (fluid load support, contact modulus, effective friction coefficient) and material properties (permeability, equilibrium contact modulus, tensile modulus) of bovine stifle cartilage to test the hypotheses that: 1) functional properties vary spatially; 2) material properties vary spatially; 3) location-specific variations in properties are consistent with location-specific differences in the mechanical environment.

2. Methods

SPECIMEN PREPARATION

Each of the N=10 independent mature (18–24 months) bovine stifle joints used in this study was retrieved on the day of butchering. Half of the freshly butchered joints (N=5) were frozen at −80°C to test for an effect of freezing. Frozen joints were thawed overnight in ambient lab conditions prior to sample extraction. Osteochondral plugs, 12.7mm in diameter, were removed by a coring saw either on the day of retrieval or after defrosting. Twenty samples were extracted from each joint, with the locations shown in Figure 1. The tibial plateau was divided into shielded (by meniscus) and uncovered regions, whereas the femoral condyle was subdivided based on the variations in the contacting surface during articulation. The outer sample contacts meniscus only, the inner contacts cartilage only, and the central contacts cartilage and meniscus throughout full articulation. Following extraction, specimens were rinsed in copious tap water to remove debris and submerged in 0.15M Dulbecco’s phosphate buffered saline (PBS). Samples were stored at 2°C immediately following dissection and extraction. Because each test required several hours to complete, each sample spent anywhere from 0 to 5 days in refrigerated storage prior to testing. The testing order of the locations was randomized to test for storage time effects.

Figure 1.

Definitions of sample sites within the bovine stifle and the regions classified for purposes of comparison. Left: the frontal plane view of a bovine stifle joint. Center: the sagittal plane view for three flexion angles in which different samples experience cartilage-cartilage contact. Right: sampling locations on the femoral condyles and tibial plateau. The comparisons of interest are the femoral condyles vs tibial plateau, medial vs lateral, and outer femoral condyles (O) vs central femoral condyles (C) vs inner femoral condyles (I) vs shielded tibial plateau (S) vs uncovered tibial plateau (U).

TESTING APPARATUS AND FUNCTIONAL CHARACTERIZATION

Tribological and material properties were measured using the custom microtribometer illustrated in Figure 2. The vertical loading assembly consists of a vertical piezoelectric stage (0–250μm ± 25nm), which is used to indent the cartilage by a measureable amount, and a two-directional load cell for measuring normal and friction forces. A 3.2mm diameter stainless steel sphere with an average roughness of Ra<80 nm was submerged in a PBS bath during testing. A tilt-stage (not shown) was used to align the surface normal at the measurement location with the z-axis of the instrument prior to measurement. A linear translation stage imposed the prescribed sliding conditions.

Figure 2.

Illustration of the custom microtribometer used to measure the material and functional properties of bovine articular cartilage.

MATERIAL PROPERTIES CHARACTERIZATION

The indentation solution for a sphere on cartilage16 was chosen for materials characterization over the traditional plane-ended creep solution 17, 18 due to several important advantages: 1) it is analytical and generally applicable without requiring master-solution datasets or interpolation from published curves, 2) it presents no stress concentrators that can damage tissue, thus enabling follow-up tribological testing at the same location, 3) it probes areas and depths that are consistent with those probed during sliding, 4) permeability fits involve physiologically-consistent combinations of fluid pressures and strains (as opposed to large strains, small fluid pressures), 5) it translates directly to tribological testing. The solution, provided in Equation 116, gives the fluid load fraction (F′) as a continuous function of mechanical conditions (δ̇: indentation rate, R: probe radius) and material properties (Et: tensile modulus, Ec0: equilibrium contact modulus, k: permeability):

| (1) |

The physical meaning of this equation is important. The first term is an asymptotic limit governed by the dimensionless modulus, 19, 20. The second term describes the rate-driven approach toward that asymptote and is governed by the Peclet number, Pe=δ̇·R/(Ec0·k. Fluid load support is negligible when Pe≪1, 50% of the asymptote when Pe=1, and at the asymptote when Pe≫113. It should be noted that this form of Pe is specific to Hertzian indentation and not necessarily appropriate for other contact situations21.

The rate-dependent fluid load fraction was measured for each sample using indentation at nominal rates of 50, 0.5, 5, 20, and 10μm/s; this randomized order was chosen to remove any hysteresis effects. The rate-dependent force-displacement curves for a representative sample are shown in Figure 3. Each curve was best-fit to Hertz’ equation: (Fn: normal force and δ: deformation) to determine the effective contact modulus, Ec, as a function of indentation rate. Following the last indent, the Z-stage was held at 175μm until steady-state to determine the equilibrium contact modulus, Ec0, directly using equilibrium force and indentation depth11. The fluid load fraction at each indentation rate was calculated using the equilibrium contact modulus and effective contact modulus: . The fluid load fraction is plotted for representative high and low-functioning samples as a function of indentation rate in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Representative data to illustrate the characterization of material properties. Left: force verses displacement curves for nominal speeds of 50, 0.5, 5, 20, and 10μm/s, in that randomized order for a representative high functioning sample. Following the last indent the stage is held fixed until equilibrium is reached. The equilibrium contact modulus is obtained directly from that point and the dotted line represents the predicted Hertzian relationship between force and deformation. Right: the fluid load fraction is calculated for representative high and low functioning samples as a function of the prescribed indentation rate. The dark labels correspond to the force-displacement data on the left. The fits to the biphasic model from Moore and Burris16 are shown in red and were used to determine tissue permeability and tensile modulus.

These data were fit to Eq. 1 to determine the permeability (k) and tensile modulus (Et) of the sample. The asymptotic limits (Pe=inf.) for the samples shown were 97% and 80%, which, by Eq. 1, gives E* values of 32 and 4, respectively. These values are used with the measured equilibrium contact modulus of the sample to determine Et. Permeability, the only remaining unknown, is fit independently using the shape of the rate dependence. For illustration, the filled data in Figure 3 represent a tensile modulus of 10.9MPa and a permeability of 0.0031mm4/Ns. The unfilled data represent a sample with a much lower tensile modulus (0.9MPa) but comparable permeability (0.0030mm4/Ns).

TRIBOLOGICAL CHARACTERIZATION

The cartilage was reconditioned by sliding the probe under load (~100mN) against the surface for 2 minutes at 5mm/s over a 1.5mm long wear track. The sample was taken out of contact for 5 additional minutes before initiating reciprocation (5mm/s over 1.5mm) and displacing the Z-stage 175μm.

Ideally, force and indentation depth would be constant, but since the two are related by a variable effective contact modulus, it is not only impossible to hold both constant, but to hold either constant causes variations in the other which exceed the measurement range of the sensor. Holding the Z-stage constant instead damps the effects of modulus and maintains a tighter range on both; the normal force varied from 25–160mN and the indentation depth varied from 134–41μm for the most and least compliant samples, respectively. This migrating contact configuration (MCA) 22 promoted a physiologically consistent lubrication environment with Pe≫1 (Pe=V·a/(Ec0·k)) 13, 16, 21–23. The lowest Peclet number for any sample during functional characterization was 100 and, according to Eq.1, the fluid load fraction was within 1% of the asymptotic value.

The effective friction coefficient, μeff, was calculated with , where FXf is the tangential force in the forward direction, FXr is the tangential force in the reverse direction, and FZavg is the average vertical force 24. In-situ penetration depth (δ) measurements were used with the measured force and probe radius to determine the effective contact modulus based on Hertz’s equation: . The fluid load fraction was determined for each sample as described in the previous section. Only depth and force data from the central 200μm portion of the track (at the indentation location) were used to determine statistics on a cycle-by-cycle basis; this strategy eliminates transient effects near reversals, maintains spatial specificity, and eliminates curvature effects. Data were collected over 50 cycles after reaching steady state, which typically happened between cycle 50 and 150 for these small contacts. The test length was just long enough to ensure steady-state, which minimized the potential for surface damage and its effect on friction.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

The effective friction coefficient, effective contact modulus, and fluid load fraction, were correlated to each tested material property (Ec0, Et, and k) and the combinations appearing in Eq. 1 (Et/Ec0 and Ec0·k) to explore the relationships between material and functional properties. The model type chosen for the fit reflects visual trends that emerged after plotting the variables; a linear fit was used if no trend was obvious.

Samples from a single joint/animal were treated dependently25. For example, when comparing the lateral compartment to the medial compartment, the average of the measurements from all 10 locations within the lateral compartment of a single joint were averaged, and this average was treated as one single independent observation out of N=10 total observations. One-way ANOVA’s (P<0.05) were run to test whether freezing, refrigeration and location significantly affected material and tribological properties. When a significant difference was detected a Tukey-Kramer post-hoc test was conducted to determine significantly different pairs.

3. Results

Neither freezing (−80°C, <2 months) nor refrigerated storage time (2°C, 0–5 days) had a statistically significant effect on the tribological or material properties of the cartilage; results are provided in Table 1.

Table I.

Sample means ± standard deviations for different storage conditions. P-values for each comparison are listed. Storage conditions did not present any significant differences, P>0.05.

| sample size (N=) | tribological properties | material properties | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| effective friction coefficient | effective contact modulus (MPa) | fluid load fraction | equilibrium contact modulus (MPa) | permeability (10−3·mm4/Ns) | tensile modulus (MPa) | |

|

| ||||||

| fresh (100) | 0.025±0.014 | 4.0±2.6 | 0.81±0.09 | 0.62±0.37 | 2.5±1.8 | 4.1±2.2 |

| frozen (100) | 0.022±0.010 | 3.8±2.4 | 0.81±0.09 | 0.63±0.40 | 3.1±4.0 | 4.5±2.4 |

| P value | 0.7383 | 0.4481 | 0.4761 | 0.9662 | 0.1415 | 0.5332 |

|

| ||||||

| day 0 (25) | 0.021±0.009 | 4.1±2.8 | 0.84±0.06 | 0.62±0.40 | 2.9±3.2 | 4.4±2.4 |

| day 1 (66) | 0.023±0.009 | 4.1±2.7 | 0.81±0.10 | 0.65±0.40 | 3.1±4.5 | 4.4±2.6 |

| day 2 (63) | 0.026±0.017 | 3.7±2.2 | 0.80±0.10 | 0.63±0.37 | 2.9±2.0 | 4.1±2.1 |

| day 3 (26) | 0.024±0.012 | 3.9±2.5 | 0.81±0.08 | 0.65±0.37 | 2.2±1.4 | 4.4±2.4 |

| day 4 (10) | 0.022±0.006 | 3.5±3.7 | 0.82±0.11 | 0.45±0.41 | 2.4±1.4 | 4.1±3.1 |

| day 5 (10) | 0.020±0.003 | 3.4±2.2 | 0.84±0.06 | 0.51±0.29 | 2.4±1.8 | 4.0±1.7 |

| P value | 0.0586 | 0.2810 | 0.6733 | 0.1175 | 0.7940 | 0.3394 |

The results from all 200 samples from N=10 bovine stifle joints are provided in Table II. Overall, cartilage from N=10 bovine stifles had an equilibrium contact modulus of Ec0=0.62±0.10MPa, a tensile modulus of Et=4.3±0.7MPa, and a permeability of k=2.8±0.9×10−3 mm4/Ns. Under physiologically consistent tribological conditions (MCA, Pe≫1) the effective friction coefficient under PBS lubrication was μeff =0.024±0.004, the effective contact modulus was Ec=3.9±0.7MPa and the fluid load fraction was F′=0.81±0.03.

Table II.

Regional means ± standard deviations for N=10 joints. P-values for each comparison are listed. Significantly different pairs are indicated by dissimilar letters. A significant difference is defined as P<0.05.

| spatial region (N=10) | tribological properties | material properties | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| effective friction coefficient | effective contact modulus (MPa) | fluid load fraction | equilibrium contact modulus (MPa) | permeability (10−3·mm4/Ns) | tensile modulus (MPa) | |

| all samples | 0.024±0.004 | 3.9±0.7 | 0.81±0.03 | 0.62±0.10 | 2.8±0.9 | 4.3±0.7 |

|

| ||||||

| medial | 0.025±0.006 | 3.6±1.2 | 0.80±0.04 | 0.60±0.19 | 3.4±1.7 | 3.8±1.3 |

| lateral | 0.022±0.004 | 4.2±0.6 | 0.82±0.03 | 0.65±0.11 | 2.3±0.2 | 4.7±0.9 |

| P value | 0.3581 | 0.1688 | 0.1507 | 0.5145 | 0.0586 | 0.1051 |

|

| ||||||

| femoral | 0.021±0.004 | 4.9±1.0 A | 0.83±0.03 | 0.77±0.14 A | 1.9±0.6 A | 5.2±0.9 A |

| tibial | 0.026±0.005 | 2.9±0.9 B | 0.79±0.03 | 0.48±0.14 B | 3.8±1.3 B | 3.4±1.0 B |

| P value | 0.1789 | 0.0142 | 0.5189 | 0.0052 | 0.0064 | 0.0427 |

|

| ||||||

| femoral C | 0.020±0.005 A | 5.9±1.1 A | 0.85±0.03 A | 0.88±0.21 A | 1.5±0.4 A | 6.0±1.0 A |

| femoral O | 0.021±0.003 A | 3.6±0.9 B | 0.85±0.03 A | 0.55±0.19 B | 2.6±1.2 A | 4.2±1.0 B |

| femoral I | 0.022±0.004 A | 3.1±1.6 B,C | 0.77±0.05 B | 0.66±0.26 A,B | 2.2±1.4 A | 3.6±1.7 B |

| tibial S | 0.024±0.008 A,B | 3.5±0.9 B | 0.85±0.02 A | 0.50±0.10 B | 2.7±0.6 A | 4.2±0.8 B |

| tibial U | 0.030±0.007 B | 2.1±0.6 C | 0.70±0.06 C | 0.46±0.14 B | 5.3±2.5 B | 2.1±0.8 C |

| P value | 0.0039 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 |

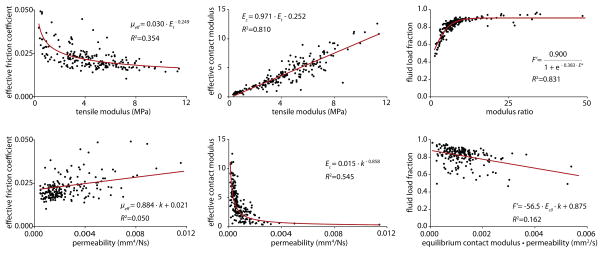

CORRELATION BETWEEN FUNCTIONAL AND MATERIAL PROPERTIES

Each functional property correlated best to a tensile property (either tensile modulus or modulus ratio) as shown in Figure 4. The friction coefficient was the most difficult functional property to predict based on material properties (R2=0.354); generally, friction decreased with increased tensile modulus. The effective contact modulus, when fit to a linear function of the tensile modulus, produced R2=0.810. The fluid load fraction, when fit to a logistical function of the modulus ratio, produced R2=0.831.

Figure 4.

Correlations between the functional performance and material properties for bovine articular cartilage. The functional properties of interest are the effective friction coefficient (Left), effective contact modulus (Center) and fluid load fraction (Right). The Top row contains the best overall correlation for each functional metric. The Bottom row contains the best overall correlation for each functional metric against Ec0, k, and Ec0·k.

The best correlations to a property or combination of properties not including tensile modulus are shown in the bottom row of Figure 4. The effective contact modulus was best fit to a non-tensile property with a power law fit to permeability producing R2=0.54; otherwise, permeability and aggregate modulus were relatively poor predictors of tribological function.

MEDIAL VS LATERAL

The comparison of tribological and material properties between the medial and lateral regions is shown in Table II. The cartilage in the lateral compartment uniformly produced more favorable average tribological and material properties, although differences were not statistically significantly.

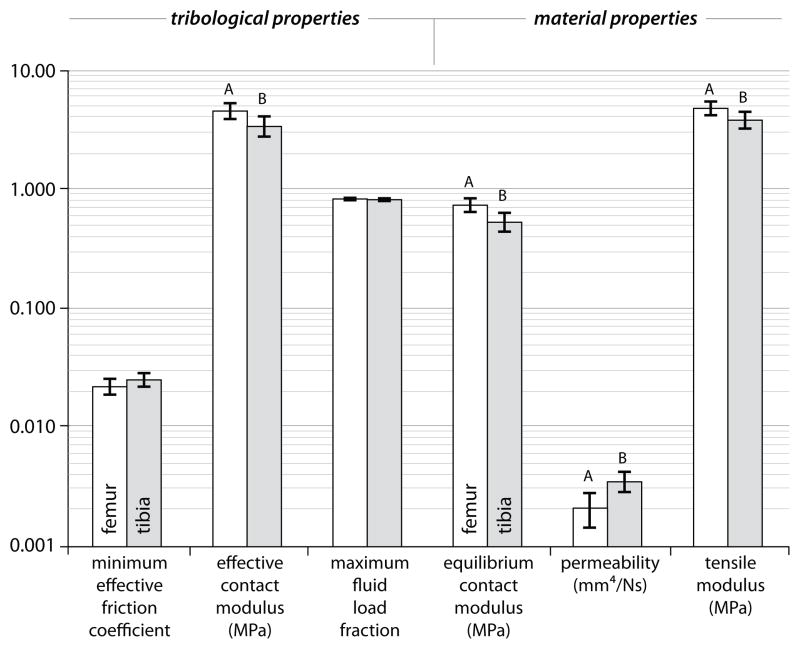

FEMORAL VS TIBIAL

The cartilage samples of the femoral condyles consistently and significantly outperformed those of the tibial plateau (Fig. 5). With μeff=0.021±0.004, Ec=4.9±1.0MPa, and F′max=0.83±0.03 the femoral condyles exhibited superior functional properties although only the difference between the effective contact moduli were statistically significant. Differences in each material property showed statistical significance. The equilibrium modulus and tensile modulus of femoral cartilage were 60% and 50% greater than those of the tibial cartilage, respectively (Table I). The permeability of femoral cartilage (1.9±0.6×10−3 mm4/Ns) was half that of the tibial cartilage. It is also worth noting that the femoral cartilage exhibited far lower variability in permeability with the standard deviation being roughly half that of tibial cartilage.

Figure 5.

Comparisons of the tribological and material properties for the femoral condyles and tibial plateaus of the bovine stifle joint. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. Significant differences are indicated by dissimilar letters, P<0.05.

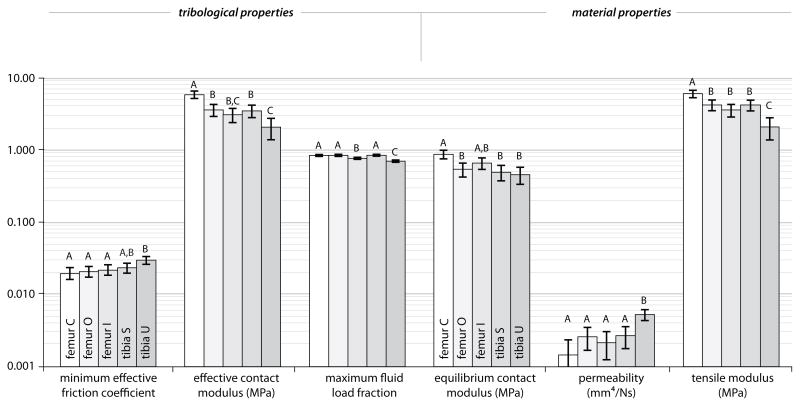

VARIATIONS DUE TO DIFFERENCES IN LOCAL CONTACT

Despite the relatively weak correlations between functional and material properties overall (Figure 4), the mean values in Figure 6 show clear evidence that each functional metric is strongly related to each material property. In general, tribological functionality (reduced friction, increased modulus, increased fluid load support) increases with increasing equilibrium contact modulus, decreasing permeability, and increasing tensile modulus.

Figure 6.

Comparisons of the tribological and material properties for the femoral central (C), outer (O), inner (I), and tibial shielded (S) and uncovered (U) regions of the bovine stifle joint. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. Significant differences are indicated by dissimilar letters, P<0.05.

The differences in mean values between the groups were statistically significant in many cases. The central femoral and uncovered tibial regions were the best and worst performers, respectively, and were statistically different with P<0.005 for each metric. The effective friction coefficient of uncovered tibial cartilage was 50% higher than that of central femoral cartilage (0.030 vs. 0.020). In addition, the mean effective contact modulus and fluid load fraction of the central femoral region were 180% and 20% greater than those of the uncovered tibial region, respectively. The difference in material properties between these two regions were of comparable magnitude; the equilibrium and tensile moduli of the central femoral cartilage were 90% and 185% greater, respectively, than those of the uncovered tibial region. The mean permeability of the uncovered tibial cartilage was 350% larger than that of the central femoral region; the standard deviation was 600% larger in the uncovered region. Despite significant differences in individual properties, only the uncovered tibial region had a significantly different product Ec0·k, the parameter governing the time constant. The outer femoral cartilage and the shielded tibial cartilage, the only regions in the study that are continually mated against the meniscus, were statistically indistinguishable in every metric.

4. Discussion

MEAN PROPERTIES OF THE BOVINE STIFLE JOINT

A new high spatial-resolution method was used here to characterize the well-studied material properties and less well-studied tribological properties of bovine articular cartilage to determine whether varied mechanical conditions within the joint create different material populations. The primary limitation of the study is that it uses an untested Hertzian contact model to characterize biphasic properties. While validation is outside the scope of this paper, comparison against existing results helps establish credibility. A second limitation is the reporting of the equilibrium contact modulus, , of cartilage, which, like the aggregate modulus, depends on two independent material properties. Early studies using linear biphasic theory report values upward of ν=0.318, 26. However, these results are now known to be artifacts of model linearity20; these values reflect the use of Poisson’s ratio to account for phenomena driven by tension-compression non-linearity, not the Poisson effect. More recent and direct measurements indicate that ν ~ 0.0420, 27, 28 in the directions relevant to this study. This value is close enough to zero to neglect differences between Ec0, aggregate modulus: Ha, and equilibrium Young’s modulus: E−y.

The values of Ec0 =0.62±0.10MPa reported here are consistent with published results for hyaline cartilage, which typically range from Ha =0.55–0.90MPa from a variety of joints and species12, 18, 26–31. The permeability measurements reported here were 2.8±0.9 × 10−3 mm4/(Ns) for the whole population. These values fall in the middle of the reported values of permeability which range between k=0.4×10−3 mm4/(Ns) and 7.6×10−3 mm4/(Ns)12, 18, 20, 26, 29–32. The permeability can vary by an order magnitude due to variations in effective strain30 and reported differences are at least partially attributable to experimental differences. The tensile moduli from this study (4.3±0.7MPa) are similarly aligned with those from the literature, which range from 3.5 to 14MPa5, 20, 29, 33. The mean values reported here are on the low end, which likely reflects the fact that the measurements occur toward the nonlinear ‘toe’ of the stress-strain curve.

This study also revealed statistics for the tribological response of bovine cartilage. The friction coefficient is not a material property but an interface property that involves the nature of both contacting surfaces and the lubricant 34. The steel-on cartilage configuration used here was decidedly non-physiological, but necessary to eliminate a second cartilage sample as a variable. As Caligaris and Ateshian showed, the friction coefficient of a rigid sphere on cartilage is quantitatively similar to that of self-mated cartilage22. The use of PBS as the lubricant detracted further from physiological relevance but was important to eliminate synovial fluid variability from the measurements. Our own unpublished measurements and those from Caligaris and Ateshian have failed to detect statistical differences22 when using PBS in place of synovial fluid, most likely because the bound species responsible for boundary lubrication remain strongly adhered under the mild conditions of relatively brief MCA testing.

Caligaris and Ateshian report similar friction statistics for the tibial plateau using MCA glass on cartilage with PBS lubricant (μeff=0.024±0.010 versus 0.026±0.005); this suggests general agreement between measurement approaches, consistency among different populations of bovine subjects, and a lack of effect from the probe material (glass and stainless are expected to be effectively inert in this environment). The fluid load fraction values reported here are consistent with our prior measurements of fluid load support 11, 16 and published ratios of the effective and equilibrium friction coefficients22, 35, 36. The effective contact modulus was Ec=3.9±0.7MPa for the whole joint and is a measure of the tissue’s capacity for load support (force per area) in Hertzian contact.

THE DISTRIBUTION OF CARTILAGE PROPERTIES

This study revealed significant differences across the bovine stifle. While there were no statistically significant differences between the material and functional properties of medial and lateral compartments it is worth noting that every property measured for the lateral compartment was superior to the corresponding measurement for the medial compartment, which carries most of the joint load 37. The more obvious differences were observed between the femoral condyle and the tibial plateau. The tribological properties of the femoral condyles were uniformly superior to those of the tibial plateau. The favorable tribological properties are accompanied by increased equilibrium modulus (60%), increased tensile modulus (50%) and decreased permeability (50%).

In general, the results from the entire data set reflected the theoretical property-function relationships16. For example, the fluid load fraction is theoretically a sigmoidal function of the modulus ratio and it can be shown that the effective contact modulus depend linearly on tensile modulus. The correlations are imperfect because 1) each tribological property depends on multiple material properties that aren’t perfectly coupled and 2) some properties affect tribological function more directly than others. For example, because the second term of Eq. 1 is very close to 1 (Pe≫1), fluid load support is more sensitive to the modulus ratio than other properties.

These differences in tribological and material properties have interesting implications for OA. Firstly, the medial compartment tends to be more prone to OA, which is consistent with the added load and less favorable properties. Secondly, Bendele and coworkers consistently find fibrillation of the tibial cartilage almost immediately following medial meniscus tear surgery with no evidence of damage on the mating femoral cartilage despite the fact that the tissues experience the same interface conditions3. This observation and the trends from this study suggest that femoral cartilage is better equipped than tibial cartilage for tribological contact.

Although we have demonstrated differences in the cartilage properties in the joint, it is unclear how significant those differences are in the context of joint disease. Prior studies provide the framework necessary to interpret this significance. Kempson, for example, has shown that the superficial zone of human articular cartilage reaches a peak tensile strength near age 25 and decreases by 75% at age 90 38. Such changes in tensile modulus have been mainly associated with changes in the superficial zone, the zone that dominates the tribological response 39. Akizuki et al. reported that fibrillation decreases the mean tensile modulus of human articular cartilage 5.6MPa to 4.5MPa; with osteoarthritic tissue, the tensile modulus decreases to 1.8MPa5. Interestingly, they found that cartilage from low-weight bearing regions had higher tensile moduli than cartilage from high weight bearing regions, which is consistent with differences observed here between the lateral and medial compartments as well as between shielded and uncovered regions of the tibial plateau. Elliott et al. found that osteoarthritis caused by meniscectomy in a canine model caused a 40% decrease in tensile modulus 33. Similarly, Setton et al. found that anterior cruciate ligament rupture in a canine model caused a 60% decrease in tensile modulus, a 20% decrease in the equilibrium compression modulus, and a 50% increase in permeability 40. In this study, we found that the uncovered region of the tibial plateau was 65% less stiff in tension and 250% more permeable than the central femoral condyle. These variations, being consistent with those induced by OA, supports the hypothesis that altered loads can initiate OA by causing contact at underprepared regions.

The results were inconsistent with our expectation that the shielded region would exhibit poorer tribological and material properties due a lack of exposure to sliding in a healthy joint. Instead, the uncovered regions, which appear to be subjected to continuous tribological contact in the healthy joint, exhibited far worse performance by every metric; this observation is consistent with tribological damage. Perhaps more alarmingly, this region had significantly increased variability and was therefore much more likely to exhibit very poor properties. These results combined with Bendele’s observation that OA initiates in the thinner, stiffer, covered region following meniscectomy3 suggests that damage is favored in the region with more favorable material and tribological properties. In this case, we believe initiation is driven by stresses not properties. With the meniscus removed, contact stresses would be much higher in these stiffer thinner areas.

Bovine results have limited implications for human OA. However, these differences in regional properties are almost certainly driven by the same fundamental biological processes that govern tissue development in other animal joints. This suggests that the results are generally applicable and can be cautiously extrapolated to the human knee. Although the results support the hypothesis that overloading of underprepared regions causes damage, it remains unclear whether differences in strength, tribological response to sliding contact, or cellular sensitivity to tribological stresses dominate a region’s tolerance to damage. It is clear, however, that 1) different regions do have different damage tolerance, 2) OA causes significant changes in material properties, 3) regions of the healthy tibial plateau have properties comparable to those of osteoarthritic cartilage, 4) those regions also suffer deficits in tribological performance that can lead to increased shear stresses and initiate OA by mechanical failure, biochemical degradation, or a combination of the two.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge financial support from the NIH (Grant P20-RR016458) for the development of the experimental and theoretical methods described in the paper.

Funding Declaration

The research was not directly funded externally.

Footnotes

Contributions

Both authors contributed equally to the experimental design, measurement, data interpretation, manuscript drafting, manuscript revision, and final approval.

Competing Interest

The authors have no competing interest to report.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Lohmander LS, Englund PM, Dahl LL, Roos EM. The long-term consequence of anterior cruciate ligament and meniscus injuries - Osteoarthritis. American Journal of Sports Medicine. 2007;35:1756–69. doi: 10.1177/0363546507307396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andriacchi TP, Mundermann A, Smith RL, Alexander EJ, Dyrby CO, Koo S. A framework for the in vivo pathomechanics of osteoarthritis at the knee. Annals of Biomedical Engineering. 2004;32:447–57. doi: 10.1023/b:abme.0000017541.82498.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bendele AM. Animal models of osteoarthritis. J Musculoskel Neuron Interact. 2001;4:363–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ebara S, Kelkar R, Bigliani L. Bovine glenoid cartilage is less stiff than humeral head cartilage in tension. Trans Orthop Res Soc. 1994;19:146. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Akizuki S, Mow VC, Muller F, Pita JC, Howell DS, Manicourt DH. Tensile Properties of Human Knee-Joint Cartilage .1. Influence of Ionic Conditions, Weight Bearing, and Fibrillation on the Tensile Modulus. Journal of Orthopaedic Research. 1986;4:379–92. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100040401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mow VC, Gu WY, Chen FH. Structure and Function of Articular Cartilage and Meniscus. In: Mow VC, Huskies R, editors. Basic Orthopedic Biomechanics and Mechanobiology. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Koo S, Rylander JH, Andriacchi TP. Knee joint kinematics during walking influences the spatial cartilage thickness distribution in the knee. Journal of Biomechanics. 2011;44:1405–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2010.11.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coleman JL, Widmyer MR, Leddy HA, Utturkar GM, Spritzer CE, Moorman CT, et al. Diurnal variations in articular cartilage thickness and strain in the human knee. Journal of Biomechanics. 2013;46:541–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2012.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li G, Park SE, DeFrate LE, Schutzer ME, Ji LN, Gill TJ, et al. The cartilage thickness distribution in the tibiofemoral joint and its correlation with cartilage-to-cartilage contact. Clinical Biomechanics. 2005;20:736–44. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2005.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shi L, Brunski DB, Sikavitsas VI, Johnson MB, Striolo A. Friction coefficients for mechanically damaged bovine articular cartilage. Biotechnology and Bioengineering. 2012;109:1769–78. doi: 10.1002/bit.24435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bonnevie ED, Baro VJ, Wang LY, Burris DL. In Situ Studies of Cartilage Microtribology: Roles of Speed and Contact Area. Tribology Letters. 2011;41:83–95. doi: 10.1007/s11249-010-9687-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McCutchen CW. The frictional properties of animal joints. Wear. 1962;5:1–17. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ateshian GA. The role of interstitial fluid pressurization in articular cartilage lubrication. Journal of Biomechanics. 2009;42:1163–76. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2009.04.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ateshian GA, Wang HQ. A Theoretical Solution for the Frictionless Rolling-Contact of Cylindrical Biphasic Articular-Cartilage Layers. Journal of Biomechanics. 1995;28:1341–55. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(95)00008-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li JY, Stewart TD, Jin ZM, Wilcox RK, Fisher J. The influence of size, clearance, cartilage properties, thickness and hemiarthroplasty on the contact mechanics of the hip joint with biphasic layers. Journal of Biomechanics. 2013;46:1641–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2013.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moore AC, Burris DL. An analytical model to predict interstitial lubrication of cartilage in migrating contact areas. Journal of Biomechanics. 2014;47:148–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2013.09.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mak AF, Lai WM, Mow VC. Biphasic Indentation of Articular-Cartilage .1. Theoretical-Analysis. Journal of Biomechanics. 1987;20:703–14. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(87)90036-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mow VC, Gibbs MC, Lai WM, Zhu WB, Athanasiou KA. Biphasic Indentation of Articular-Cartilage .2. A Numerical Algorithm and an Experimental-Study. Journal of Biomechanics. 1989;22:853–61. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(89)90069-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Park SH, Krishnan R, Nicoll SB, Ateshian GA. Cartilage interstitial fluid load support in unconfined compression. Journal of Biomechanics. 2003;36:1785–96. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(03)00231-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Soltz MA, Ateshian GA. A conewise linear elasticity mixture model for the analysis of tension-compression nonlinearity in articular cartilage. Journal of Biomechanical Engineering. 2000;122:576–86. doi: 10.1115/1.1324669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bonnevie ED, Baro VJ, Wang L, Burris DL. Fluid load support during localized indentation of cartilage with a spherical probe. Journal of Biomechanics. 2012;45:1036–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2011.12.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Caligaris M, Ateshian GA. Effects of sustained interstitial fluid pressurization under migrating contact area, and boundary lubrication by synovial fluid, on cartilage friction. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage. 2008;16:1220–7. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2008.02.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ateshian GA, Wang H. Rolling resistance of articular cartilage due to interstitial fluid flow. Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers Part H-Journal of Engineering in Medicine. 1997;211:419–24. doi: 10.1243/0954411971534548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Burris DL, Sawyer WG. Addressing Practical Challenges of Low Friction Coefficient Measurements. Tribology Letters. 2009;35:17–23. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ranstam J. Repeated measurements, bilateral observations and pseudoreplicates, why does it matter? Osteoarthritis and Cartilage. 2012;20:473–5. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2012.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Athanasiou KA, Rosenwasser MP, Buckwalter JA, Malinin TI, Mow VC. Interspecies Comparisons of Insitu Intrinsic Mechanical-Properties of Distal Femoral Cartilage. Journal of Orthopaedic Research. 1991;9:330–40. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100090304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jurvelin JS, Buschmann MD, Hunziker EB. Optical and mechanical determination of Poisson’s ratio of adult bovine humeral articular cartilage. Journal of Biomechanics. 1997;30:235–41. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(96)00133-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang CCB, Chahine NO, Hung CT, Ateshian GA. Optical determination of anisotropic material properties of bovine articular cartilage in compression. Journal of Biomechanics. 2003;36:339–53. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(02)00417-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Basalo IM, Nauck RL, Kelly TA, Nicoll SB, Chen FH, Hung CT, et al. Cartilage interstial fluid load support in unconfined compression following enzymatic digestion. Journal of Biomechanical Engineering. 2004;126:779–86. doi: 10.1115/1.1824123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mow VC, Kuei SC, Lai WM, Armstrong CG. Biphasic Creep and Stress-Relaxation of Articular-Cartilage in Compression - Theory and Experiments. Journal of Biomechanical Engineering-Transactions of the Asme. 1980;102:73–84. doi: 10.1115/1.3138202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen AC, Bae WC, Schinagl RM, Sah RL. Depth- and strain-dependent mechanical and electromechanical properties of full-thickness bovine articular cartilage in confined compression. Journal of Biomechanics. 2001;34:1–12. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(00)00170-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Williamson AK, Chen AC, Sah RL. Compressive properties and function-composition relationships of developing bovine articular cartilage. Journal of Orthopaedic Research. 2001;19:1113–21. doi: 10.1016/S0736-0266(01)00052-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Elliott DM, Guilak F, Vail TP, Wang JY, Setton LA. Tensile properties of articular cartilage are altered by meniscectomy in a canine model of osteoarthritis. Journal of Orthopaedic Research. 1999;17:503–8. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100170407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dunn AC, Sawyer WG, Angelini TE. Gemini Interfaces in Aqueous Lubrication with Hydrogels. Tribology Letters. 2014;54:59–66. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Krishnan R, Kopacz M, Ateshian GA. Experimental verification of the role of interstial fluid prezzurization in cartilage lubrication. Journal of Orthopaedic Research. 2004;22:565–70. doi: 10.1016/j.orthres.2003.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Caligaris M, Canal CE, Ahmad CS, Gardner TR, Ateshian GA. Investigation of the frictional response of osteoarthritic human tibiofemoral joints and the potential beneficial tribological effect of healthy synovial fluid. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage. 2009;17:1327–32. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2009.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schipplein OD, Andriacchi TP. Interaction between Active and Passive Knee Stabilizers during Levelwalking. Journal of Orthopaedic Research. 1991;9:113–9. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100090114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kempson GE. Relationship between the Tensile Properties of Articular-Cartilage from the Human Knee and Age. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 1982;41:508–11. doi: 10.1136/ard.41.5.508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Temple MM, Bae WC, Chen MQ, Lotz M, Amiel D, Coufts RD, et al. Age- and site-associated biomechanical weakening of human articular cartilage of the femoral condyle. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage. 2007;15:1042–52. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2007.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Setton LA, Mow VC, Muller FJ, Pita JC, Howell DS. Mechanical-Properties of Canine Articular-Cartilage Are Significantly Altered Following Transection of the Anterior Cruciate Ligament. Journal of Orthopaedic Research. 1994;12:451–63. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100120402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]