Abstract

Background

To our knowledge, no whole brain investigation of morphological aberrations in dissociative disorder is available to date. Previous region-of-interest studies focused exclusively on amygdalar, hippocampal and parahippocampal grey matter volumes and did not include patients with depersonalization disorder (DPD). We therefore carried out an explorative whole brain study on structural brain aberrations in patients with DPD.

Methods

We acquired whole brain, structural MRI data for patients with DPD and healthy controls. Voxel-based morphometry was carried out to test for group differences, and correlations with symptom severity scores were computed for grey matter volume.

Results

Our study included 25 patients with DPD and 23 controls. Patients exhibited volume reductions in the right caudate, right thalamus and right cuneus as well as volume increases in the left dorsomedial prefrontal cortex and right somatosensory region that are not a direct function of anxiety or depression symptoms.

Limitations

To ensure ecological validity, we included patients with comorbid disorders and patients taking psychotropic medication.

Conclusion

The results of this first whole brain investigation of grey matter volume in patients with a dissociative disorder indentified structural alterations in regions subserving the emergence of conscious perception. It remains unknown if these alterations are best understood as risk factors for or results of the disorder.

Introduction

Depersonalization disorder (DPD), classified as a dissociative disorder in DSM-5, is characterized by symptoms of detachment from one’s mental processes, disembodiment, emotional numbing and derealization. Reality testing remains intact, and patients do not experience a fragmentation of identity. Depersonalization disorder is often chronic and severely disabling.1,2 Its prevalence is estimated to lie between 0.8% and 2.4% in the general population.3–5 Dissociation, defined as a disruption in usually integrated mental functions of consciousness, memory, identity or perception, is the constitutive element of dissociative disorders. Dissociative disorders have been conceptualized as trauma-related clinical symptoms, resulting in defined neural responses that differ from those associated with anxiety-related responses.6–8 However, little empirical data on structural brain alterations subserving the lack of integration in dissociative disorders have been published to date. To our knowledge, this is the first study reporting data on structural brain alterations in patients with DPD. Functional brain imaging studies previously identified activation differences in patients with DPD in a variety of brain regions. During the resting state, hypoperfusion in temporal regions as well as hyperperfusion in the precuneus and temporoparietal junction were observed,9 while hypoactivation of the insula10 and the amygdala11 have been reported in reaction to emotional stimuli.

Aberrations in patients with other dissociative disorders

In recent years, voxel-based morphometry (VBM) has been used to identify localized differences in grey matter density in patients with other dissociative disorders. This method relies on a segmentation of brain matter into grey and white matter and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) based on voxel intensities. In the absence of structural data in patients with DPD, empirical evidence for morphological alterations and aberrant activations in patients with other dissociative disorders may be informative. To date, 4 studies on grey matter alterations in patients with dissociative identity disorder (DID) have been published.12–15 The available volumetric neuroimaging studies in patients with DID exclusively provide region-of-interest analyses of the amygdala, hippocampus and the parahippocampal gyrus rather than whole brain assessments. Compared with healthy controls, patients with DID were reported to have smaller amygdalar,12,13 hippocampal12–14 and parahippocampal brain volumes.12 In addition, one of these studies analyzed data from 13 patients with a dissociative disorder not otherwise specified; they also exhibited bilaterally reduced volumes in the amygdala, hippocampus and parahippocampal gyrus, albeit to a lesser degree than the DID sample.12 These 3 analyses were carried out on small samples ranging from 1 to 15 participants. However, an additional study based on a mixed sample of 13 patients with either DID or dissociative amnesia reported preserved amygdalar and hippocampal volumes.16 Previous studies also identified varied functional alterations in patients with DID implicating cortical regions, such as the middle and superior frontal gyri and pre- and postcentral gyri, and occipital regions as well as subcortical structures, such as the amygdala and caudate.17–19 In patients with dissociative amnesia, functional hypoactivations, mainly within the insula and ventrolateral prefrontal regions, have been demonstrated in small samples,20,21 but no empirical data on structural brain alterations are available.

Neural correlates of dissociation in posttraumatic stress disorder

Dissociative symptoms are also regularly reported by patients with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and the distinction of a dissociative subtype has been suggested.7,8 However, in PTSD, dissociation is thought to be a transitory state that lasts from a few seconds to a few hours, whereas dissociative disorders are typically characterized by rather stable, chronic dissociative symptoms. To date, only 1 study has analyzed the structural brain correlates of dissociative symptoms in patients with PTSD. Nardo and colleagues22 reported a positive correlation between the severity of dissociative symptoms and the volume of the medial superior frontal gyrus, the bilateral temporal poles and the angular gyrus as well as a negative correlation with the volume of the putamen. Functional correlates of dissociative processing in patients with PTSD entail medial prefrontal and anterior cingulate regions as well as the amygdala, insula, putamen and thalamus.23–26

Aims of the study

To our knowledge, this is the first study to report structural brain alterations in patients with a dissociative disorder at the whole brain level. We conducted a voxel-based analysis of structural MRI data in a sample of severely impaired patients with DPD as compared with matched, healthy controls. In addition, we computed correlations between grey matter volume and a measure of DPD symptom severity within the patient group.

Methods

Participants

We recruited participants via advertisements posted online, within the community and in mental health treatment centres. The DPD and control groups were matched for sex, age and handedness. All participants underwent a full clinical examination using 3 structured interviews.27–29 The diagnosis of DPD was established by J.K.D. based on the German version of the Structured Clinical Interview for Dissociative Disorders.27 Participants fulfilled the criteria of DPD according to DSM-IV (300.6) as well as the criteria of the depersonalization-derealization syndrome according to ICD-10 (F48.1). In addition, we assessed personality disorders using the International Personality Disorder Examination.28 To ensure ecological validity, we generally did not exclude patients with comorbid disorders, except for patients with a history of lifetime psychotic disorders, substance addiction in remission for less than 6 months (as assessed by the German version of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV29) and current PTSD. As there is considerable symptom overlap with the suggested dissociative subtype of PTSD, we opted to exclude patients with current PTSD to disambiguate the diagnostic status. Healthy controls underwent the same assessment procedures and were included in the control group only if no mental disorder was identified. Further exclusion criteria were current use of benzodiazepines or opioids, lifetime neurologic disorders, serious head injury, pregnancy, insufficient command of the German language and MRI-incompatible metallic implantations.

The research ethics board at the Charité Universitätsmedizin Berlin approved our study protocol. After complete description of the study, we obtained written informed consent from all participants.

Measures

Both the German 30-item trait version and the 22-item state version of the Cambridge Depersonalization Scale (CDS)30 were used to assess symptom severity of depersonalization and de-realization. The trait version served as an initial screening tool, whereas the state version was administered on the day of the MRI scan. For the CDS trait version (α = 0.981), items are scored independently for frequency and duration. Frequency is scored on a 4-point Likert scale, and duration is scored on a 6-point scale. Only patients scoring above 60 on the trait version were invited for clinical interviews. For the state version, items are scored on a 10-point Likert scale. In addition, participants completed the German versions of the Dissociative Experiences Scale (DES31), the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI32), the Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale,33 the trait version of the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (LSAS34), the questionnaire for functional and dysfunctional self-focused attention,35 the Emotion Regulation Questionnaire,36 the Kentucky Inventory of Mindfulness Skills,37 the Toronto Alexithymia Scale,38 the Sheehan Disability Scale39 and the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire Short Form.40 In order to measure executive control, participants also underwent the Trail Making Test.41

MRI acquisition

Participants were scanned on a 3 T Siemens Tim Trio scanner. T1-weighted images were acquired with the following parameters: magnetization-prepared rapid acquisition with gradient echo sequence, repetition time 1.9 ms, echo time 2.52 ms, inversion time 900 ms, flip angle 9°, field of view 256 mm, 192 slices, 1 mm isovoxels, 50% distancing factor.

VBM processing

Voxel-based morphometry analysis was performed using SPM8 (Wellcome Trust Centre for Neuroimaging, www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm) and Matlab 7.8.0 (MathWorks). First, all T1-weighted anatomic images were manually reoriented to place the anterior commissure at the origin of the 3-dimensional Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) space. The images were then segmented into grey matter, white matter and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). The DARTEL algorithm was used to generate a group-specific template based on 23 participants from each group. For each participant, a flow field storing the deformation information for warping the participants’ scans onto the template was created. These were then used to spatially normalize grey matter images to MNI space using affine spatial normalization as implemented in the normalization algorithm included in the DARTEL toolbox. This last step involved smoothing with an 8-mm full-width at half-maximum (FWHM) isotropic Gaussian kernel. Anatomic labelling was carried out using the Automated Anatomic Labelling (AAL) atlas42 included in the SPM toolboxes WFU_PickAtlas and xjView. For the thalamus, probable cortical connectivities were identified based on the probabilistic tractography atlas43 included in the anatomy toolbox (all SPM toolboxes are available at www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm/ext/).

Statistical analyses

Voxel-wise comparisons of grey matter volume between groups were performed using 2-sample t tests with absolute threshold masking at 0.2. In this exploratory whole brain analysis, we opted to use a statistical threshold of p < 0.001 in combination with a nonstationary threshold to balance the risks of type-I and type-II errors.44 The nonstationary extent threshold was computed with the VBM-8 toolbox for SPM (http://dbm.neuro.uni-jena.de/vbm). As reduced grey matter volumes in the amygdala, hippocampus and parahippocampal gyrus have previously been reported for patients with other dissociative disorders, region-of-interest analyses with p < 0.001 and a more liberal extent threshold of k ≥ 10 were performed on these structures. Age, sex and total grey matter volume (analyzed with the SPM extension Easy volumes; www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm/ext) were included as covariates of no interest in all analyses. To ensure that group differences in grey matter volume were not solely due to group differences in depression or anxiety severity, the group contrast was masked by the results of a correlation between grey matter volume (corrected for age, sex and total grey matter volume) and depression as measured with the BDI as well as anxiety as measured with the STAI. As 9 patients were on psychotropic medication at the time of the scan, we computed a subgroup analysis excluding these patients to investigate if the observed effects are stable.

In order to elucidate the basis of the observed group differences in grey matter volume, correlational analyses (all thresholded at p = 0.001 with a nonstationary extent threshold) were carried out with all questionnaire scales yielding significant group differences. These correlational analyses were then masked by the main effect of group to identify any potential overlap.

All behavioural statistics were carried out with SPSS version 15.0 (IBM, www-01.ibm.com/software/analytics/spss) using 2-sided tests thresholded at p < 0.05.

Results

Sample characteristics

The sample consisted of 25 patients with DPD and 23 healthy controls, matched for sex (18 female patients, 18 female controls), age and handedness. Overall, 12.5% of the sample did not graduate from high school, whereas for 29.2% high school graduation was the highest education level, 8.4% successfully completed a structured apprenticeship, 10.4% had a college diploma, and 39.6% had a university degree. The 2 groups did not differ significantly regarding their education level (Mann– Whitney U = 277, p = 0.83). Nine patients were using psychotropic medication at the time of the scan: antipsychotic plus lamotrigine (n = 1), antidepressant plus lamotrigine (n = 1), anti-depressants (n = 6) and β-blocker (n = 1). These 9 patients did not differ significantly on any of the questionnaire measures from the remaining 16 unmedicated DPD patients. However, there was a trend toward higher alexithymia scores as measured with the Toronto Alexithymia Scale38 (t22 = 1.774, p = 0.09). For 24 of 25 patients with DPD, information regarding age at symptom onset was available. The DPD symptoms commenced on average when patients were in their late teens (mean 17.08 ± 5.81 yr), but there was a considerable range from 4 years to 27 years of age. At the time of the scan, patients had been living with DPD on average for 13.71 ± 9.48 (range 2–36) years. In most cases, the symptoms had been chronic since their onset, with no or only short-lived interruptions. The patient group showed a trend toward more childhood trauma (p = 0.05) and reported significantly more childhood physical neglect (p = 0.017; Table 1).

Table 1.

Descriptive sample statistics

| DPD | Control | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||

| Factor | No. | Mean ± SD | No. | Mean ± SD | t score | p value |

| Age, yr | 25 | 31.60 ± 8.09 | 23 | 29.96 ± 7.99 | 0.708 | 0.48 |

| Grey matter volume, L | 25 | 0.7078 ± 0.0643 | 23 | 0.7190 ± 0.0691 | −0.583 | 0.56 |

| Intracranial volume, L | 25 | 1.3567 ± 0.1461 | 23 | 1.2916 ± 0.1609 | 1.469 | 0.15 |

| CDS-30 | 25 | 147.44 ± 42.23 | 23 | 9.61 ± 12.04 | 15.644 | < 0.001 |

| DES | 25 | 21.24 ± 10.48 | 23 | 1.80 ± 1.95 | 9.102 | < 0.001 |

| TAS-20 | 25 | 60.16 ± 8.47 | 23 | 46.61 ± 7.53 | 5.834 | < 0.001 |

| LSAS | 25 | 43.40 ± 30.53 | 23 | 17.43 ± 16.35 | 3.713 | 0.001 |

| STAI-T | 25 | 57.12 ± 11.68 | 23 | 34.00 ± 11.37 | 6.937 | < 0.001 |

| BDI | 25 | 21.20 ± 10.95 | 23 | 2.48 ± 3.41 | 8.133 | < 0.001 |

| ERQ_App | 25 | 3.63 ± 1.22 | 23 | 3.17 ± 1.23 | 3.404 | 0.001 |

| ERQ_Sup | 25 | 3.78 ± 1.49 | 23 | 5.13 ± 1.26 | −2.275 | 0.028 |

| KIMS | 25 | 104.96 ± 18.76 | 23 | 142.22 ± 13.19 | −7.905 | < 0.001 |

| DFS_Func | 25 | 23.56 ± 6.31 | 23 | 32.04 ± 4.45 | −5.343 | < 0.001 |

| DFS_Dysf | 25 | 50.56 ± 10.32 | 23 | 32.83 ± 9.78 | 6.099 | < 0.001 |

| CTQ_Sum | 24 | 52.46 ± 16.89 | 23 | 44.22 ± 10.33 | 2.028 | 0.05 |

| CTQ_SA | 24 | 6.33 ± 2.85 | 23 | 5.65 ± 1.72 | 0.985 | 0.33 |

| CTQ_PA | 25 | 6.56 ± 2.77 | 23 | 5.91 ± 1.91 | 0.935 | 0.36 |

| CTQ_EA | 25 | 11.08 ± 5.81 | 23 | 8.35 ± 3.71 | 1.957 | 0.06 |

| CTQ_PN | 25 | 7.72 ± 3.04 | 23 | 6.00 ± 1.54 | 2.506 | 0.017 |

| CTQ_EN | 25 | 12.44 ± 6.01 | 23 | 9.57 ± 5.27 | 1.755 | 0.09 |

| TMT-A | 22 | 24.45 ± 5.44 | 21 | 24.90 ± 6.80 | −0.240 | 0.81 |

| TMT-B | 22 | 51.68 ± 13.93 | 21 | 53.19 ± 18.59 | −0.302 | 0.76 |

App = appraisal; BDI = Beck Depression Inventory; CDS = Cambridge Depersonalization Scale; CTQ = Childhood Trauma Questionnaire; DES = Dissociative Experiences Scale; DFS = Questionnaire for functional and dysfunctional self-focused attention; DPD = depersonalization disorder; EA = emotional abuse; EN = emotional neglect; ERQ = Emotion Regulation Questionnaire; KIMS = Kentucky Inventory of Mindfulness Skills; LSAS = Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale; PA = physical abuse; PN = physical neglect; SA = sexual abuse; SD = standard deviation; STAI-T = State-Trait Anxiety Scale, trait version; Sup = suppression; TAS = Toronto Alexithymia Scale, TMT = Trail Making Test.

The patients exhibited a number of current comorbid disorders, predominantly anxiety disorders (panic disorder [n = 2], social anxiety disorder [n = 13], specific phobia [n = 2], obsessive–compulsive disorder [n = 2], generalized anxiety disorder [n = 1]) and mood disorders (major depressive disorder [n = 2]). A smaller proportion also had personality disorders (emotionally unstable — impulsive type [n = 1], emotionally unstable — borderline type [n = 1], anxious avoidant [n = 1], dependent [n = 1]). At the time of the scan, 18 of the 25 patients (72%) had current comorbid disorders, but lifetime prevalences were notably higher, with a total of 20 patients (80%) reporting lifetime comorbidities: major depressive disorder (n = 13), panic disorder (n = 3), social anxiety disorder (n = 13), specific phobia (n = 2), obsessive–compulsive disorder (n = 2), PTSD (n = 1), generalized anxiety disorder (n = 1), conversion disorder (n = 1), impulse control disorder (n = 1), eating disorders (n = 5) and substance dependence (n = 1).

The patient group also exhibited significantly more trait dissociation, alexithymia, social phobia, trait anxiety and depressive symptoms than the control group (Table 1). Convergently, patients reported significantly less mindfulness, less use of reappraisal strategies and more use of suppression to regulate their emotions, as well as less functional and more dysfunctional self-focus. All questionnaire measures were highly correlated with symptom severity, as measured with CDS-30 (see the Appendix, Table S1, available at jpn.ca).

VBM results

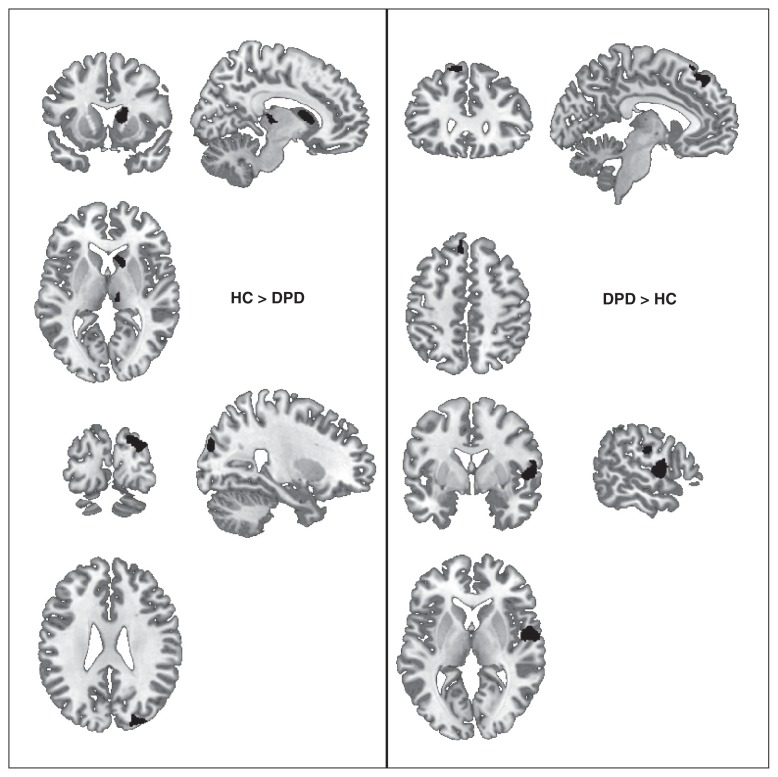

The DPD group exhibited significant decreases in grey matter volume in the right caudate (spanning body and head subregions), the right thalamus (including mostly pulvinar and ventral lateral nucleus subregions) and the right middle and superior occipital gyri. The thalamus region showing a significant volume reduction in the patient group entails subregions probably structurally connected with prefrontal and temporal cortical regions.43 Significant volume increases were detected in the DPD group compared with the control group in the left medial superior frontal gyrus as well as the right superior temporal and postcentral gyri (Table 2 and Fig. 1). The region-of-interest analyses on the amygdala, hippocampus and parahippocampal gyrus did not return significant group differences. All regions characterized by significant group differences also showed a significant correlation between grey matter volume and symptom severity, as measured with the CDS-30 (Table 2).

Table 2.

Grey matter volume reductions in the DPD group versus the control group and explorative correlational results*

| Group; hemisphere | MNI coordinates, x, y, z | t score | Cluster size, k | Brain region† | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 23 control > 25 DPD, k > 49 | ||||||

| Right | 20 | −87 | 30 | 4.80 | 278 | Superior occipital gyrus (BA 19) |

| Right | 29 | −87 | 24 | 4.21 | Middle occipital gyrus (BA 19) | |

| Right | 15 | 9 | 7 | 3.93 | 572 | Caudate |

| Right | 8 | −18 | 1 | 3.77 | 96 | Thalamus (prefrontal prob. 94%) |

| Right | 9 | −25 | 12 | 3.43 | Thalamus (pulvinar) (temporal prob. 82%) | |

| 25 DPD > 23 control, k > 49 | ||||||

| Right | 59 | −13 | 27 | 4.77 | 95 | Postcentral gyrus (BA 3, BA 4) |

| Left | −9 | 30 | 60 | 4.72 | 315 | Medial superior frontal gyrus (BA 6, BA 8) |

| Left | −6 | 41 | 48 | 4.25 | Medial superior frontal gyrus | |

| Left | −20 | 21 | 55 | 3.71 | Superior frontal gyrus | |

| Right | 53 | −1 | 3 | 4.71 | 604 | Superior temporal gyrus (BA 22) |

| Right | 60 | 0 | 15 | 3.74 | Postcentral gyrus | |

| Subgroup analysis masked by full sample contrast, 23 control > 16 DPD | ||||||

| Right | 21 | −87 | 31 | 5.69 | 273 | Superior occipital gyrus |

| Right | 29 | −87 | 24 | 5.00 | Middle occipital gyrus (BA19) | |

| Right | 9 | −25 | 13 | 4.63 | 96 | Thalamus (temproal prob 80%) |

| Right | 9 | −15 | 3 | 4.17 | Thalamus (ventral lateral nucleus) (prefrontal prob. 92%) | |

| Right | 8 | 21 | 1 | 4.45 | 468 | Caudate |

| Right | 15 | 8 | 7 | 4.31 | Caudate | |

| Right | 17 | 9 | 21 | 3.63 | Caudate | |

| Subgroup analysis masked by full sample contrast, 16 DPD > 23 control | ||||||

| Right | 54 | −1 | 3 | 5.30 | 410 | Superior temporal gyrus (BA 22) |

| Right | 59 | −13 | 27 | 4.39 | 57 | Postcentral gyrus (BA 4) |

| Positive correlation between grey matter and CDS-30 scores (masked by group contrast) | ||||||

| Left | −8 | 36 | 49 | 4.40 | 110 | Medial superior frontal gyrus (BA 8) |

| Right | 59 | −13 | 25 | 4.09 | 53 | Postcentral gyrus (BA 3) |

| Right | 56 | 0 | 4 | 4.08 | 222 | Superior temporal gyrus (BA 22) |

| Negative correlation between grey matter and CDS-30 scores (masked by group contrast) | ||||||

| Right | 18 | 9 | 18 | 3.97 | 430 | Caudate |

| Right | 15 | 12 | 7 | 3.90 | Caudate | |

| Right | 8 | −25 | 13 | 3.78 | 93 | Thalamus (temporal prob. 82%) |

| Right | 9 | −16 | 3 | 3.75 | Thalamus (prefrontal prob. 93%) | |

| Right | 32 | −87 | 27 | 3.72 | 70 | Middle occipital gyrus |

| Right | 20 | −87 | 30 | 3.59 | Superior occipital gyrus (BA 19) | |

| Negative correlation between grey matter and DES scores (masked by group contrast) | ||||||

| Right | 18 | 9 | 19 | 4.09 | 148 | Caudate |

| Right | 11 | −16 | 4 | 4.02 | 78 | Thalamus (prefrontal prob. 95%) |

| Negative correlation between grey matter and DFS–dysfunctional scores (masked by group contrast) | ||||||

| Right | 20 | 9 | 16 | 3.63 | 54 | Caudate |

| Positive correlation between grey matter and KIMS scores (masked by group contrast) | ||||||

| Right | 9 | −16 | 3 | 3.85 | 72 | Thalamus (prefrontal prob. 93%) |

| Negative correlation between grey matter and KIMS scores (masked by group contrast) | ||||||

| Left | −9 | 36 | 49 | 4.40 | 218 | Medial superior frontal gyrus (BA 8) |

| Left | −15 | 30 | 60 | 4.32 | Superior frontal gyrus (BA 6) | |

| Positive correlation between grey matter and LSAS scores (masked by group contrast) | ||||||

| Left | −18 | 21 | 54 | 4.30 | 47 | Superior frontal gyrus |

| Negative correlation between grey matter and STAI-T scores (masked by group contrast) | ||||||

| Right | 29 | −88 | 22 | 3.92 | 55 | Middle occipital gyrus (BA 19) |

| Positive correlation between grey matter and TAS-20 scores (masked by group contrast) | ||||||

| Left | −21 | 23 | 55 | 4.10 | 111 | Superior frontal gyrus |

| Left | −12 | 29 | 60 | 3.95 | Superior frontal gyrus (BA 6) | |

BA = Brodmann area; CDS-30 = Cambridge Depersonalization Scale; DES = Dissociative Experiences Scale; DFS = Questionnaire for functional and dysfunctional self-focused attention; DPD = depersonalization disorder; KIMS = Kentucky Inventory of Mindfulness Skills, LSAS = Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale, MNI = Montreal Neurological Institute; STAI-T = State-Trait Anxiety Scale, trait version, TAS = Toronto Alexithymia Scale.

All analyses were thresholded at p < 0.001 with nonstationary cluster extent correction at k > 49. The following had no significat results: positive correlation between grey matter and DES scores (masked by group contrast), positive correlation between grey matter and DFS-dysfunctional scores (masked by group contrast), negative correlation between grey matter and LSAS scores (masked by group contrast), positive correlation between grey matter and STAI-T scores (masked by group contrast), negative correlation between grey matter and TAS-20 scores (masked by group contrast).

Thalamus subregions are additionally defined by their probabilistic connectivity with cortical regions43 (including the probability in percent).

Fig. 1.

Significant differences in grey matter volume in patients with depersonalization disorder (DPD; n = 25) compared with healthy controls (HC; n = 23), thresholded at p < 0.001 with nonstationary cluster extent correction k > 49.

To elucidate the basis for the observed group differences, explorative correlations between additional questionnaire measures and grey matter volume were computed and masked by the results of the group comparison in order to identify any overlap. However, they were strictly exploratory owing to the high intercorrelation between all questionnaire measures and the CDS-30. The caudate region exhibiting a significant volume reduction in the patient group showed a significant negative correlation between grey matter volume and the severity of dissociative symptoms as measured with the DES as well as with the severity of dysfunctional self focus as measured with the DFS. Similarly, the thalamus region showing a significant volume reduction in the patient group also exhibited a negative correlation between grey matter volume and severity of dissociative symptoms as measured with the DES as well as a positive correlation with mindfulness as measured with the KIMS. The volume reduction in the right cuneus region in the patient group showed a negative correlation with the severity of trait anxiety as measured with STAI-T. The medial superior frontal gyrus region characterized by a volumetric increase in the DPD group demonstrated a positive correlation with social anxiety as measured with LSAS and alexithymia as measured with TAS-20 as well as a negative correlation with mindfulness as measured with the KIMS. Importantly, correlational analyses with measures of childhood trauma (CTQ sum scores, CTQ physical neglect score), depression (BDI) and emotion regulation (ERQ) did not return volumetric correlates in the brain regions identified by the group contrast.

The subgroup analysis excluding 9 patients on psychotropic medication at the time of the scan returned very similar group differences (albeit with smaller cluster extents as expected owing to the lower statistical power) plus additional grey matter reductions in the patient group in the left caudate, left thalamus and right angular gyrus as well as additional grey matter increases in bilateral temporal poles (see the Appendix, Table S2).

Discussion

As evidenced by both self-report data and clinical diagnostics, patients with DPD are severely impaired and report longstanding chronicity of their symptoms as well as a high number of lifetime comorbid disorders. On average, the disorder was established by the end of puberty, although there was a considerable range in age at symptom onset. The observed high rates of comorbid mood and anxiety disorders are in accordance with previous reports.45 Significantly higher rates of childhood neglect were reported by the DPD group than the control group.

The DPD group exhibited significantly reduced grey matter volume in the right caudate, the right thalamus and the right cuneus compared with healthy controls. Notably, amygdalar and hippocampal volumes showed no between-group differences, even at the very lenient threshold used for the region-of-interest analyses.

In addition, the DPD group showed significant volume increases in the right postcentral and superior temporal gyri as well as in the left superior frontal gyrus.

All volumetric alterations were significantly correlated with symptom severity of DPD as measured with the CDS-30 and exhibited stability after exclusion of all medicated patients.

Reductions in grey matter volume in patients with DPD

The DPD group showed significantly reduced grey matter volume in the right caudate and thalamus. Interestingly, the subgroup analysis excluding medicated patients extended these findings to the homologous structures in the left hemisphere. Grey matter volume in these regions was significantly negatively correlated with symptom severity, trait dissociation and dysfunctional self focus (for the caudate) and was significantly positively correlated with mindfulness (for the thalamus).

The thalamus is considered to be the gateway for sensory input to the corresponding cortical areas. It has therefore been implicated in the emergence of sensory awareness,46 which is severely impaired in patients with dissociative disorders, such as DPD. The temporal binding between oscillations in remote brain regions is thought to be a prerequisite for awareness. Previous studies have indicated that during discrete, consciously perceived events the thalamic γ activity matches the cortical γ activity,47 and it has been suggested that the thalamus drives this coherence and thus enables cross-modal consciousness.48 Rather than exerting unidirectional governance, the thalamus is thought to be a central node in complex cortico–thalamo–cortical loops.46 The central recipient of cortical feedback is the caudate, which in turn back-projects to the thalamus. Importantly, the caudate is known to receive input from emotion processing areas, such as the amygdala and insula, and has been implicated in dissociative analgesia.26 Any anatomic alteration of the thalamus and the caudate is therefore likely to impact communicative integration and might be associated with alterations in emotional and sensory awareness. Convergently, the reduction of subjective body ownership has been associated with lesions in the thalamus and caudate,49 and acute lesions through infarction in these regions have previously been associated with the onset of severe depersonalization and derealization symptoms in 2 single case studies.50,51 Divergent activations of the thalamus and the caudate were previously reported in patients with DID, depending on the identity state,18 and in patients with dissociative PTSD when subliminally confronted with fear faces.25 Interestingly, the only study investigating the correlation between trait dissociation in PTSD and grey matter volume also reported a significant negative correlation with a large cluster in the basal ganglia, centred on the putamen.22

The occipital cortex region showing grey matter reductions in the DPD group is thought to subserve motion perception, particularly the perception of depth conveyed by moving stimuli.52 This finding could possibly be related to the reduction in 3-dimensional vision reported subjectively by the patients. Future studies might follow up on this finding with visual tasks measuring surface perception objectively.

Increases in grey matter volume in patients with DPD

The DPD group exhibited increased grey matter volume in a right-lateralized cluster spanning the postcentral and superior temporal gyri as well as in a left-lateralized cluster in the superior frontal gyrus. Grey matter volume in the superior frontal gyrus was significantly positively correlated with symptom severity, social anxiety and alexithymia as well as significantly negatively correlated with mindfulness. This region is known to subserve executive control of attention and emotion53,54 and is functionally connected with the thalamus.54,55 Volumetric increases in the medial superior frontal gyrus have previously been reported in patients with obsessive–compulsive disorder,56 potentially linking the volume increases in patients with DPD to the dysfunctional self-focus and aberrant emotion regulation observed in this group. In a recent meta-analysis, the homologous area in the right hemisphere has been associated with the disruption of the sense of self-agency and an external attribution of the action effect.57 In conjunction, this region could potentially be involved in the hyperregulation of affect and agency as suggested by recent models of trauma-related dissociation.7

The detected increase in grey matter volume in the right postcentral and superior temporal gyri is particularly interesting, as this part of the primary somatosensory cortex (Brodmann area [BA] 3) receives thalamocortical projections from the sensory input fields and is involved in the processing of proprioception and body ownership.49 Future studies should therefore aim at elucidating the link between volumetric grey matter alterations in this region and the subjective sense of self.

Limitations

Owing to the cross-sectional nature of this study, it remains unknown if the observed structural brain differences are best understood as risk factors for the development of DPD or as a result of the disorder. Future studies should aim at capturing possible neuroplastic adjustments over the course of the disorder, using a longitudinal design and a sample of patients with recent symptom onset.

In order to ensure ecological validity, we opted not to exclude patients with comorbid disorders except for patients with a history of lifetime psychotic disorders, substance addiction in remission for less than 6 months and PTSD. We can therefore not ascertain that the reported differences in brain anatomy are directly and solely related to the diagnosis of DPD, but we did not find significant correlations between grey matter volume and symptoms of anxiety or depression in the patient group alone or in the full sample in these regions. However, as only 20% of the DPD sample had no lifetime comorbid disorders, it remains debatable whether the conceptualization of comorbidity is rightfully applicable to this disorder or whether anxiety and depressive symptoms should rather be understood as integral components of the disorder itself. Similarly, the neuroplastic effects of previous and current pharmacological treatments could not be estimated, as most patients had tried various drug combinations over the course of their illness. We therefore opted to exclude current use of benzodiazepines and opioids, but we refrained from including current medication status as an additional regressor in the model, as previous medication use might have had comparable effects. Future studies should try to include patients who never received psychotropic medication to control for this potential confound.

Conclusion

Patients with DPD are characterized by extensive, but circumscribed alterations in brain anatomy rather than large-scale morphological aberrations as seen in patients with schizophrenia. The central finding of our study is the grey matter volume reduction in the thalamus and the caudate — 2 key nodes of cortico–thalamo–cortical networks required for the emergence of sensory awareness and consciousness.

Footnotes

Competing interests: The authors reported no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest. The work presented in the manuscript was supported by grant no. II/84051 from the Volkswagen Foundation to H. Walter.

Contributors: All authors designed the study. J. Daniels, M. Gaebler and J.-P. Lamke acquired the data, which J. Daniels and H. Walter analyzed. J. Daniels wrote the article, which all authors reviewed and approved for publication.

References

- 1.Simeon D, Knutelska M, Nelson D, et al. Feeling unreal: a depersonalization disorder update of 117 cases. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64:990–7. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v64n0903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baker D, Hunter E, Lawrence E, et al. Depersonalisation disorder: clinical features of 204 cases. Br J Psychiatry. 2003;182:428–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johnson JG, Cohen P, Kasen S, et al. Dissociative disorders among adults in the community, impaired functioning, and axis I and II comorbidity. J Psychiatr Res. 2006;40:131–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2005.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hunter ECM, Sierra M, David AS. The epidemiology of depersonalisation and derealisation. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2004;39:9–18. doi: 10.1007/s00127-004-0701-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Michal M, Wiltink J, Subic-Wrana C, et al. Prevalence, correlates, and predictors of depersonalization experiences in the German general population. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2009;197:499–506. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e3181aacd94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lanius RA, Frewen PA, Vermetten E, et al. Fear conditioning and early life vulnerabilities: two distinct pathways of emotional dys-regulation and brain dysfunction in PTSD. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2010;1 doi: 10.3402/ejpt.v1i0.5467. [Epub 2010 Dec. 10] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lanius RA, Brand B, Vermetten E, et al. The dissociative subtype of posttraumatic stress disorder: rationale, clinical and neurobiological evidence, and implications. Depress Anxiety. 2012;29:701–8. doi: 10.1002/da.21889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lanius RA, Vermetten E, Loewenstein RJ, et al. Emotion modulation in PTSD: clinical and neurobiological evidence for a dissociative subtype. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167:640–7. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09081168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Simeon D, Guralnik O, Hazlett EA, et al. Feeling unreal: a PET study of depersonalization disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:1782–8. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.11.1782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Phillips ML, Medford N, Senior C, et al. Depersonalization disorder: thinking without feeling. Psychiatry Res. 2001;108:145–60. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4927(01)00119-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lemche E, Anilkumar A, Giampietro VP, et al. Cerebral and autonomic responses to emotional facial expressions in depersonalisation disorder. Br J Psychiatry. 2008;193:222–8. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.107.044263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ehling T, Nijenhuis ER, Krikke AP. Volume of discrete brain structures in complex dissociative disorders: preliminary findings. Prog Brain Res. 2008;167:307–10. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(07)67029-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vermetten E, Schmahl C, Lindner S, et al. Hippocampal and amygdalar volumes in dissociative identity disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:630–6. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.4.630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tsai GE, Condie D, Wu MT, et al. Functional magnetic resonance imaging of personality switches in a woman with dissociative identity disorder. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 1999;7:119–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weniger G, Lange C, Sachsse U, et al. Amygdala and hippocampal volumes and cognition in adult survivors of childhood abuse with dissociative disorders. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2008;118:281–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2008.01246.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weniger G, Lange C, Sachsse U, et al. Amygdala and hippocampal volumes and cognition in adult survivors of childhood abuse with dissociative disorders. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2008;118:281–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2008.01246.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sar V, Unal SN, Ozturk E. Frontal and occipital perfusion changes in dissociative identity disorder. Psychiatry Res. 2007;156:217–23. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2006.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reinders AATS, Nijenhuis ERS, Quak J, et al. Psychobiological characteristics of dissociative identity disorder: a symptom provocation study. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;60:730–40. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reinders AATS, Nijenhuis ERS, Paans AMJ, et al. One brain, two selves. Neuroimage. 2003;20:2119–25. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2003.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fujiwara E, Piefke M, Lux S, et al. Brain correlates of functional retrograde amnesia in three patients. Brain Cogn. 2004;54:135–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brand M, Eggers C, Reinhold N, et al. Functional brain imaging in 14 patients with dissociative amnesia reveals right inferolateral prefrontal hypometabolism. Psychiatry Res. 2009;174:32–9. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2009.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nardo D, Hogberg G, Lanius RA, et al. Gray matter volume alterations related to trait dissociation in PTSD and traumatized controls. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2013;128:222–33. doi: 10.1111/acps.12026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Daniels JK, Coupland NJ, Hegadoren KM, et al. Neural and behavioral correlates of peritraumatic dissociation in an acutely traumatized sample. J Clin Psychiatry. 2012;73:420–6. doi: 10.4088/JCP.10m06642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hopper JW, Frewen PA, van der Kolk BA, et al. Neural correlates of reexperiencing, avoidance, and dissociation in PTSD: symptom dimensions and emotion dysregulation in responses to script-driven trauma imagery. J Trauma Stress. 2007;20:713–25. doi: 10.1002/jts.20284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Felmingham K, Kemp AH, Williams L, et al. Dissociative responses to conscious and non-conscious fear impact underlying brain function in post-traumatic stress disorder. Psychol Med. 2008;38:1771–80. doi: 10.1017/S0033291708002742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mickleborough MJ, Daniels JK, Coupland NJ, et al. Effects of trauma-related cues on pain processing in posttraumatic stress disorder: an fMRI investigation. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2011;36:6–14. doi: 10.1503/jpn.080188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gast U, Oswald P, Zündorf F, et al. Das Strukturierte Klinische Interview für DSM-IV-Dissoziative Störungen. Interview und Manual. Göttingen (DE): Hogrefe; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mombour W, Zaudig M, Berger P, et al. International Personality Disorder Examination. Bern (DE): Hogrefe; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wittchen H-U, Zaudig M, Fydrich T. Strukturiertes Klinisches Interview für DSM-IV. Göttingen (DE): Hogrefe; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Michal M, Sann U, Niebecker M, et al. [The measurement of the depersonalisation-derealisation-syndrome with the German version of the Cambridge Depersonalisation Scale (CDS)]. Psychother Psychosom Med Psychol. 2004;54:367–74. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-828296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Spitzer C, Stieglitz RD, Stieglitz RD. Fragebogen zu Dissoziativen Symptomen. Ein Selbstbeurteilungsverfahren zur syndromalen Diagnostik dissoziativer Phänomene. Bern (DE): Huber; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hautzinger M, Bailer M, Worrall H, et al. Beck-Depressions-Inventar. Bern (DE): Huber; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stangier U, Heidenreich T. Die Liebowitz Soziale Angst-Skala (LSAS) Göttingen (DE): Hogrefe; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Laux L, Spielberger CD. Das State-Trait-Angstinventar: STAI. Weinheim (DE): Beltz; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hoyer C. Der Fragebogen zur Dysfunktionalen und Funktionalen Selbstaufmerksamkeit (DFS) Diagnostica. 2000;46:140–8. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Abler B, Kessler H. Emotion Regulation Questionnaire — Eine deutschsprachige Fassung des ERQ von Gross und John. Diagnostica. 2009;55:144–52. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ströhle G, Nachtigall C, Michalak J, et al. Die Erfassung von Achtsamkeit als mehrdimensionales Konstrukt. Z Klin Psychol Psychother. 2010;39:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bach M, Bach D, de Zwaan M, et al. Validierung der deutschen Version der 20-Item Toronto-Alexithymie-Skala bei Normalpersonen und psychiatrischen Patienten. Psychother Psychosom Med Psychol. 1996;46:23–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gräfe K. Sheehan Disability Scale (SDS) In: Hoyer J, Margraf J, editors. Angstdiagnostik grundlagen und testverfahren. Berlin (DE): Springer; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wingenfeld K, Spitzer C, Mensebach C, et al. Fragebogen zu Dissoziativen Symptomen (FDS): ein Selbstbeurteilungsverfahren zur syndromalen Diagnostik dissoziativer. 2010. Apr 1, [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stanczak DE, Lynch MD, McNeil CK, et al. The expanded trail making test: Rationale, development, and psychometric properties. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 1998;13:473–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tzourio-Mazoyer N, Landeau B, Papathanassiou D, et al. Automated anatomical labeling of activations in SPM using a macroscopic anatomical parcellation of the MNI MRI single-subject brain. Neuroimage. 2002;15:273–89. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2001.0978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Behrens TE, Johansen-Berg H, Woolrich MW, et al. Non-invasive mapping of connections between human thalamus and cortex using diffusion imaging. Nat Neurosci. 2003;6:750–7. doi: 10.1038/nn1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lieberman MD, Cunningham WA. Type I and Type II error concerns in fMRI research: re-balancing the scale. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2009;4:423–8. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsp052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Michal M, Wiltink J, Till Y, et al. Distinctiveness and overlap of depersonalization with anxiety and depression in a community sample: results from the Gutenberg Heart Study. Psychiatry Res. 2011;188:264–8. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2010.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Van der Werf YD, Witter MP, Groenewegen HJ. The intralaminar and midline nuclei of the thalamus. Anatomical and functional evidence for participation in processes of arousal and awareness. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2002;39:107–40. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(02)00181-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Steriade M. Corticothalamic resonance, states of vigilance and mentation. Neuroscience. 2000;101:243–76. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(00)00353-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Min BK. A thalamic reticular networking model of consciousness. Theor Biol Med Model. 2010;7:10. doi: 10.1186/1742-4682-7-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gandola M, Invernizzi P, Sedda A, et al. An anatomical account of somatoparaphrenia. Cortex. 2012;48:1165–78. doi: 10.1016/j.cortex.2011.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Duggal HS. A lesion approach to neurobiology of dissociative symptoms. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2003;15:245–6. doi: 10.1176/jnp.15.2.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lambert MV, Sierra M, Phillips ML, et al. The spectrum of organic depersonalization: a review plus four new cases. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2002;14:141–54. doi: 10.1176/jnp.14.2.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Beer AL, Watanabe T, Ni R, et al. 3D surface perception from motion involves a temporal-parietal network. Eur J Neurosci. 2009;30:703–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2009.06857.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Xu J, Rees G, Yin X, et al. Spontaneous neuronal activity predicts intersubject variations in executive control of attention. Neuroscience. 2014;263:181–92. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2014.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kohn N, Eickhoff SB, Scheller M, et al. Neural network of cognitive emotion regulation — an ALE meta-analysis and MACM analysis. Neuroimage. 2014;87:345–55. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhang S, Ide JS, Li CS. Resting-state functional connectivity of the medial superior frontal cortex. Cereb Cortex. 2012;22:99–111. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhr088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tan L, Fan Q, You C, et al. Structural changes in the gray matter of unmedicated patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder: a voxel-based morphometric study. Neurosci Bull. 2013;29:642–8. doi: 10.1007/s12264-013-1370-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sperduti M, Delaveau P, Fossati P, et al. Different brain structures related to self- and external-agency attribution: a brief review and meta-analysis. Brain Struct Funct. 2011;216:151–7. doi: 10.1007/s00429-010-0298-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]