Abstract

Objective

Since conflicting results have been published on the role of tobacco smoking on the risk of endometriosis, we provide an up-to-date summary quantification of this potential association.

Design

We performed a PubMed/MEDLINE search of the relevant publications up to September 2014, considering studies on humans published in English. We searched the reference list of the identified papers to find other relevant publications. Case–control as well as cohort studies have been included reporting risk estimates on the association between tobacco smoking and endometriosis. 38 of the 1758 screened papers met the inclusion criteria. The selected studies included a total of 13 129 women diagnosed with endometriosis.

Setting

Academic hospitals.

Main outcome measure

Risk of endometriosis in tobacco smokers.

Results

We obtained the summary estimates of the relative risk (RR) using the random effect model, and assessed the heterogeneity among studies using the χ2 test and quantified it using the I2 statistic. As compared to never-smokers, the summary RR were 0.96 (95% CI 0.86 to 1.08) for ever smokers, 0.95 (95% CI 0.81 to 1.11) for former smokers, 0.92 (95% CI 0.82 to 1.04) for current smokers, 0.87 (95% CI 0.70 to 1.07) for moderate smokers and 0.93 (95% CI 0.69 to 1.26) for heavy smokers.

Conclusions

The present meta-analysis provided no evidence for an association between tobacco smoking and the risk of endometriosis. The results were consistent considering ever, former, current, moderate and heavy smokers, and across type of endometriosis and study design.

Keywords: GYNAECOLOGY, EPIDEMIOLOGY

Strengths and limitations of this study.

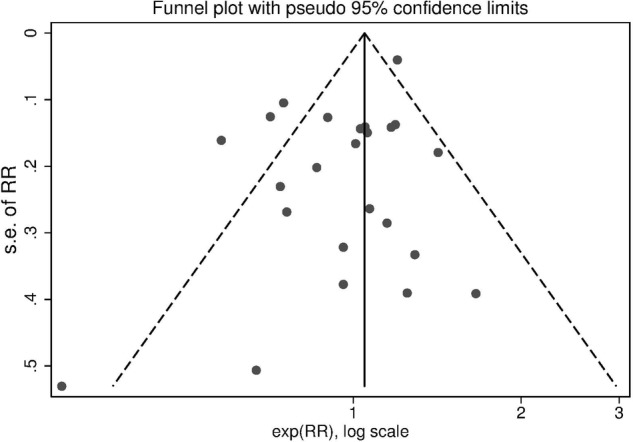

Meta-analysis including 38 papers without any relevant asymmetry in the funnel plot.

The Egger's test was not statistically significant.

In some studies, choice of cases as asymptomatic without distinguishing factors related to endometriosis to those associated with pelvic pain or infertility.

In some studies, choice of controls in whom disease was not laparoscopically ruled out.

Tobacco smoking based on patients’ self-reported information.

Introduction

Endometriosis is an oestrogen-dependent, chronic inflammatory gynaecological condition characterised by the proliferation of functional endometrial tissue that develops outside the uterine cavity, which may cause pain and infertility.1 However, despite its relatively high prevalence, which spans from 20% in asymptomatic women2 to 30% in women with infertility,3 and 45% in women with pain symptoms,4 risk factors for this condition remain largely unknown.

Among the risk factors investigated, some studies have examined the role of tobacco smoking. In a Portuguese study investigating clinical and lifestyle factors in infertile women, current smokers had a decreased risk of endometriosis as compared to non-smokers or former smokers.5 In a case–control study from Turkey evaluating the interaction between tobacco smoking and glutathione-S-transferase gene polymorphism as a risk factor for endometriosis, an inverse association between smoking and endometriosis was observed.6 In a case–control study carried out in the USA, infertile women with endometriosis and fertile controls were compared, and a decreased risk of endometriosis was found, though limited to women who had begun smoking at an early age and were heavy smokers.7 Other studies did not find significant association.3 8–14

The biological plausibility potentially linking smoking and endometriosis resides in its endocrine and inflammatory mechanisms. Smoke compounds disrupt steroidogenesis, leading to impairment of E2 synthesis15 16 and progesterone synthesis deficiency.17–19 Moreover, smoking has a strong effect on inflammatory mediators in the pulmonary as well as extra-pulmonary environments and can further trigger inflammation associated with the disease, resulting in pro-inflammatory gene overexpression.20

A clear definition of the relation between smoking and endometriosis risk is required in order to better understand the role of oestrogens, in consideration of the potential antioestrogenic effect of smoking. Otherwise, in clinical terms, a direct association as reported in some studies6 7 may suggest preventive measures.

Thus, in order to investigate the possible relation between tobacco smoking and endometriosis, and to provide an overall quantitative estimate of any such relation, we combined all published data on the issue in a meta-analysis.

Materials and methods

Search strategy

We performed a PubMed/MEDLINE search of papers published between 1966 and September 2014, using the terms “tobacco” or “smoking” or “cigarette” in combination with “risk factor” or “epidemiology”, and “endometriosis”, following the MOOSE (Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) guidelines21; details on the search terms are provided in online supplementary appendix. We selected only studies on humans, published as full-length papers in English. No effort was made to identify papers published in other languages or unpublished studies. Moreover, we reviewed the reference lists of the retrieved papers to identify any other relevant publications. Studies were included in the meta-analysis if: (1) they were based on case–control or cohort studies, reporting original data; (2) they reported information on the association between tobacco smoking and endometriosis, including estimates of the relative risk (RR) (approximated by the odds ratio (OR), in case-control studies), with the corresponding 95% CIs, or frequency distribution to calculate them; (3) diagnosis of endometriosis was histologically confirmed and/or clinically based. When we found more than one publication based on the same study population and data, we included only the one with most detailed information, or published most recently.

We used the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale22 to assess the quality of individual studies and performed a sensitivity analysis according to the quality of each study.

Data extraction for the meta-analysis

Two authors (FB and SC) reviewed the manuscripts and independently selected the eligible manuscripts; disagreements were resolved by discussion. From each publication we extracted the following information: country of origin; study design; number and characteristics of subjects (cases, controls or cohort size); age, if available; categories of tobacco smoking, if available; measures of association (RR or OR) of endometriosis and corresponding 95% CI for every category of tobacco smoking, or frequency distribution to calculate them; and confounding variables allowed for in the statistical analysis, if any. When more than one regression model was provided, estimates adjusted for the largest number of confounding variables were considered.

Statistical analysis

For some studies, we pooled estimates of different categories of cases or controls using the method by Hamling et al,23 which allows combining of the estimates originally shown in the paper, changing the reference category and taking into account their correlation. We obtained the summary estimates of the RR using the random effect model (ie, as weighed averages on the sum of the inverse of the variance of the log RR and the moment estimator of the variance between studies).24 We assessed the heterogeneity among studies using the χ2 test25 and quantified it using the I2 statistic, which represents the percentage of the total variation across studies that is attributable to heterogeneity rather than chance.26 Results were defined as heterogeneous for p values less than 0.10.

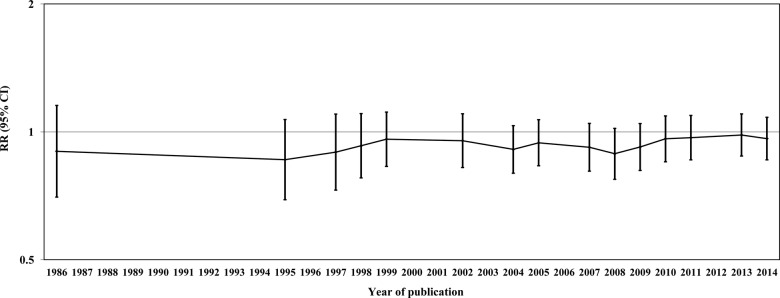

We computed summary estimates for ever tobacco smokers, former smokers, current smokers, moderate current smokers and heavy current smokers, as compared to never-smokers. Different cut-points for moderate and heavy smoking were chosen, depending on those shown in the papers. We also carried out a cumulative meta-analysis to determine whether the association between tobacco smoking and endometriosis changed over time. In the cumulative meta-analysis, studies are added one at a time, ordered by year of publication, and the results are pooled as each new study is added. In the graph, the vertical line corresponding to each year represents the RR and corresponding CI of the results of the meta-analysis of the studies published up to that year, rather than the results of a single study.27 Furthermore, we performed subgroup analyses according to the type of controls (fertile, infertile, both/not specified). Publication bias was evaluated using a funnel plot28 and was quantified by the Egger's test.29

Results

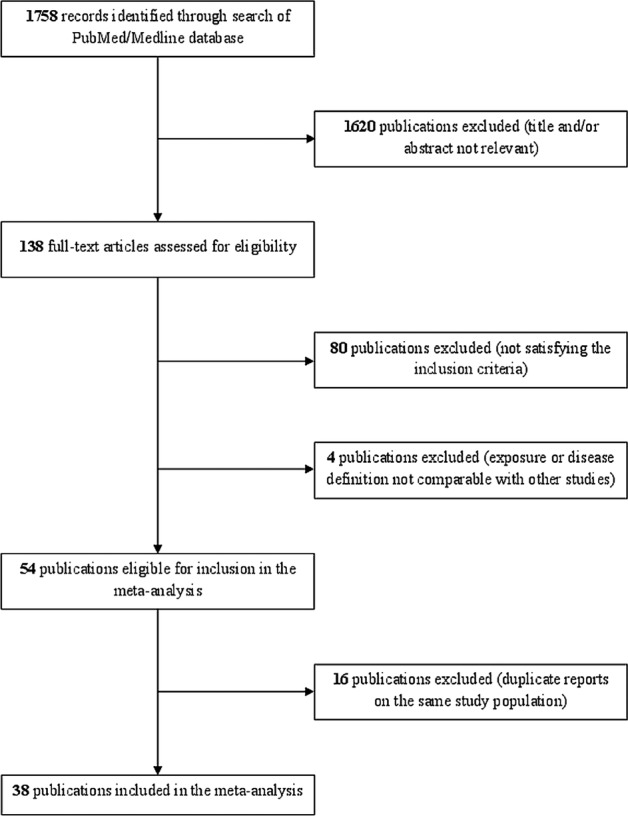

Figure 1 shows the flow chart of the selection of publications. The literature search yielded 1758 reports, of which 1620 were excluded after evaluation of abstract and full text, because they did not report any information on the relationship between tobacco smoking and risk of endometriosis, and 80 because they did not satisfy the inclusion criteria. Moreover, four studies were not comparable with the others, since reported estimates for lifetime smoking30 included former or light smokers in the reference category,11 included women with stage I endometriosis in the comparison group,31 or reported serum cotinine as measure of exposure to tobacco smoking (including passive smoking),32 and thus we excluded those studies from the meta-analysis.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the selection of studies on tobacco smoking and risk of endometriosis included in the meta-analysis.

Furthermore, we excluded 16 studies based on the same data of other included publications.33–48 Thus, in the present meta-analysis we combined data from 38 studies, including a total of 13 129 women with endometriosis (see online supplementary file table S1).3 5–10 12–14 49–76

Online supplementary file table S1 shows the main characteristics of the studies included in the present meta-analysis. Most publications were based on case–control studies, while nine were cohort studies in which, however, the role of smoking was evaluated at the same time of the disease diagnosis,13 50 52 54 58 70 74 except in two cases, in which smoking status was assessed at baseline.5 49 Of these, 16 studies were from Europe,3 5 9 10 49 52 54–57 60 62 66 68 69 71 13 from the USA,7 12–14 50 53 58 61 64 65 67 70 72 2 from Canada,8 63 5 from Asia6 51 59 74 75 and 2 from Australia.73 76

Twenty-four studies reported information on ever smokers,5 7–10 13 14 49 50 52 54 56 57 60 61 64 67 68 71–76 16 on former smokers5 7–10 13 52 54 56 57 61 64 68 71–73 and 30 on current smokers.3 5–10 12 13 51–59 61–66 68–73 Among these, eight reported more categories of current smokers, thus we could calculate separate estimates for moderate and heavy current smokers. We used different cut-points for various study populations, depending on those presented in the papers: thus the cut-point between moderate and heavy smokers was defined as 20 cigarettes per day in five studies,5 8 53 71 72 15 cigarettes per day in two studies13 58 and 10 cigarettes per day in one study.10

For some studies reporting separate estimates for different types of patients and/or controls, we computed a pooled estimate. In particular, Coccia et al52 reported separate estimates for monolateral and bilateral endometriosis, Heilier et al57 for endometriosis and deep endometriotic nodules, Parazzini et al68 for deep endometriosis, and pelvic and ovarian endometriosis, Signorello et al14 for fertile and infertile controls, and Tsuchiya et al75 for stage I/II and stage III/IV endometriosis. Moreover, Calhaz-Jorge et al5 reported separate estimates for grade I/II and grade III/IV endometriosis, as well as for any type of endometriosis, and the Gruppo Italiano per lo Studio dell'endometriosi,10 including two separate groups of cases and controls undergoing laparoscopy for pelvic pain or infertility, showed separate as well as pooled estimate; in both cases we included the combined estimates in the meta-analysis; further, Pollack et al70 included an operative cohort comprising women scheduled for laparoscopy/laparotomy and an age-matched population cohort of women who underwent pelvic MR for the detection of endometriosis, and we summed up the two groups.

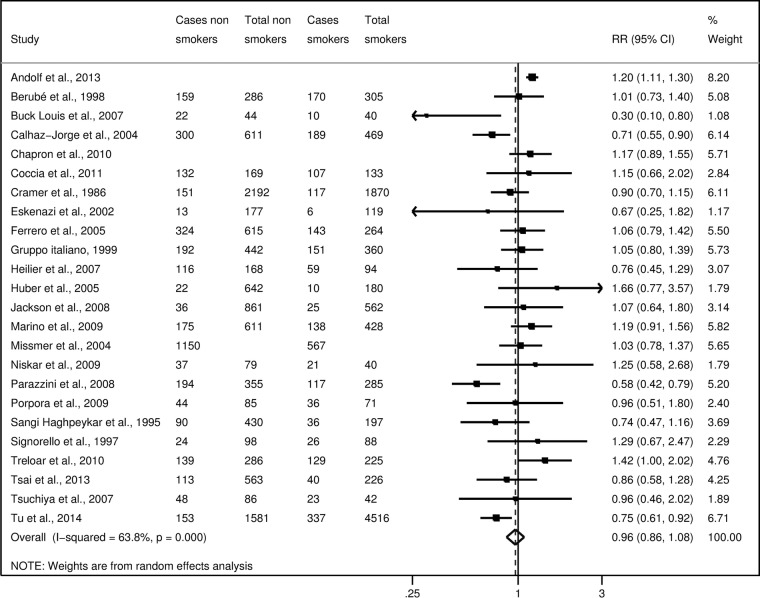

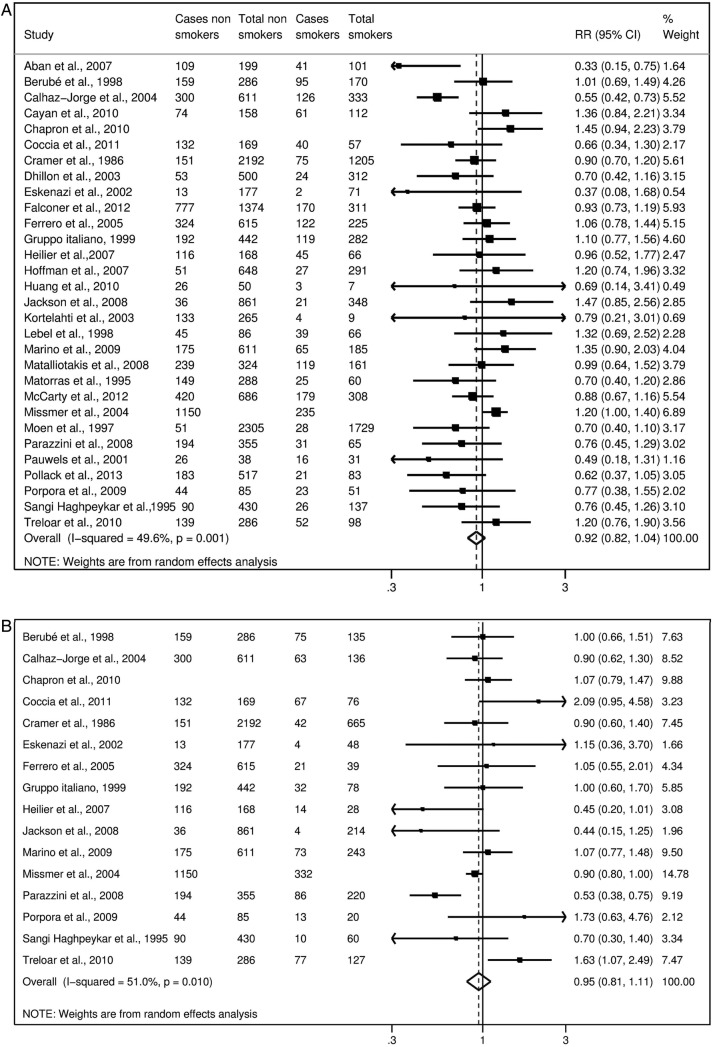

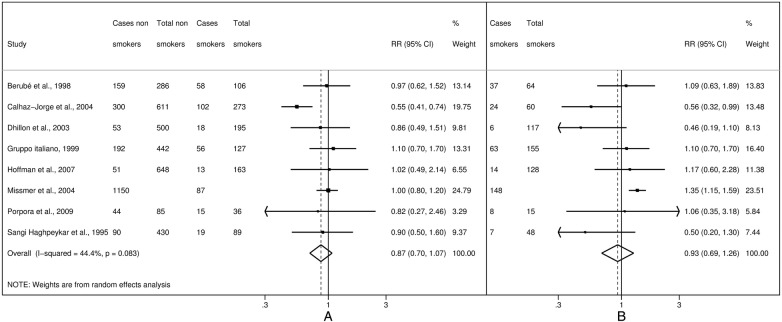

Considering ever smokers or, separately, former smokers, current smokers, moderate smokers and heavy smokers, no statistically significant association emerged (figures 2–4).

Figure 2.

Study-specific and summary relative risks (RR) of endometriosis for ever smokers versus never-smokers.

Figure 3.

Study-specific and summary relative risks (RR) of endometriosis for current (A) and former smokers (B) versus never-smokers.

Figure 4.

Study-specific and summary relative risks (RR) of endometriosis for moderate (A) and heavy (B) current smokers versus never-smokers.

Figure 5 shows the funnel plot for ever smokers versus non-smokers. There was no evidence of publication bias (p=0.054).

Figure 5.

Funnel plot of studies on tobacco smoking and risk of endometriosis (RR, relative risk for ever smokers versus never-smokers).

When we restricted the analyses to nine studies reporting risk estimates adjusted for confounding variables, risk estimates were 1.01 (95% CI 0.86 to 1.19) for ever smokers, 0.94 (95% CI 0.85 to 1.03) for former smokers, 0.87 (95% CI 0.64 to 1.17) for current smokers, 0.85 (95% CI 0.60 to 1.20) for moderate current smokers and 0.90 (95% CI 0.57 to 1.43) for heavy current smokers versus never-smokers.

In subgroup analyses according to type of controls, estimates for ever smokers versus non-smokers were 1.06 (95% CI 0.89 to 1.27) for 7 studies including fertile women, 0.92 (95% CI 0.75 to 1.12) for 7 studies including infertile women and 0.95 (95% CI 0.81 to 1.12) for 14 studies including both or not specified types of controls. Moreover, when we restricted the analyses to studies with cases and controls laparoscopically or surgically confirmed, the risk estimates were 0.97 (95% CI 0.87 to 1.07) for ever smokers, 0.94 (95% CI 0.85 to 1.03) for former smokers, 0.90 (95% CI 0.77 to 1.04) for current smokers, 0.86 (95% CI 0.66 to 1.12) for moderate smokers and 0.97 (95% CI 0.70 to 1.35) for heavy smokers.

Quality score ranged between 2 and 7 (median 4.5). When we restricted the meta-analysis to 19 high-quality studies (with quality score ≥5) the pooled estimates did not materially change (data not shown). Figure 6 shows the cumulative meta-analysis of endometriosis risk for ever smokers versus non-smokers over time, from 1986 to 2014: small variations in the RR estimates emerged over time.

Figure 6.

Cumulative meta-analysis of studies on tobacco smoking and risk of endometriosis (RR, relative risk for ever smokers versus never-smokers).

Discussion

The present meta-analysis does not support an association between smoking and endometriosis risk. No association emerged considering subgroups of ever, former, current, moderate and heavy smokers, nor in sensitivity and subgroup analyses.

However, this work may be affected by limitations and biases intrinsic to the original observational studies included in the meta-analysis, as well as to the limits that we chose to apply to the bibliographic search, including the restriction to searching PubMed only and the exclusion of languages other than English. Regarding the characteristics of the observational studies, a major concern is the ascertainment of the presence or absence of endometriosis. Some studies compared symptomatic cases with asymptomatic controls, and thus could not distinguish factors related to endometriosis with those associated with pelvic pain or infertility. Moreover, generally asymptomatic controls did not undergo laparoscopy or other surgical procedures, and therefore the presence of asymptomatic endometriosis in these women cannot be ruled out. Another concern is the fact that in some studies diagnosis of endometriosis was self-reported. Thus, a misclassification of cases and controls could not be definitively excluded. However, when we restricted the analyses to women in whom laparoscopy or a surgical procedure had confirmed the presence or absence of endometriotic lesions, we still did not find any significant association between smoking and endometriosis. Further, tobacco smoking is based on patients’ self-reported information, thus some misclassification may have occurred. However, information on tobacco smoking in observational studies has been shown to be satisfactorily reproducible and valid.77–79 For most studies included in the present meta-analysis, only raw estimates were available, since tobacco smoking was not the main topic of the paper and it was only reported as a confounding variable. However, estimates from these studies were similar to those from studies specifically investigating the role of smoking, thus allowing us to rule out major publication bias on this issue. Moreover, we did not find any relevant asymmetry in the funnel plot, and the Egger's test was not statistically significant. Thus, publication bias is unlikely to have appreciably modified the relation between tobacco smoking and endometriosis. Although previous studies have reported an association between endometriosis and menstrual and reproductive factors, such as early menarche,7 12 longer duration of bleeding,7 intra-uterine device use,80 or a lifelong regular menstrual pattern of shorter cycles and heavy flows,7 12 72 81 nulliparity or low parity,14 30 38 82 only some studies included in the present meta-analysis have accounted for the role of these factors in the estimate of the relation between tobacco smoking and endometriosis. However, analyses based on adjusted estimates only were comparable to those based on raw estimates.

Since endometriosis is an oestrogen-dependent condition, the inverse association between smoking and endometriosis found in some studies has generally been attributed to the anti-oestrogenic effect of tobacco.83 Some authors have suggested that oestradiol might modulate the mediators of immune system molecules or those involved in tissue cell adhesion and invasion.84 85 Moreover, a favourable effect of smoking has been observed in other benign and malignant oestrogen-related diseases, such as endometrial cancer86 and fibroids.87 The antioestrogenic effect of smoking on these conditions could support a protective effect of smoking on endometriosis. Indeed, earlier studies tended to support some inverse association, which, however, declined over time, and accumulating evidence suggests the presence of some false-positive findings in earlier studies.88 Furthermore, tobacco smoking has been associated with female infertility,89 and thus the interpretation of the relation between smoking and endometriosis may be influenced by the role of infertility.

Despite the high prevalence of this condition, the epidemiology of endometriosis still needs to be elucidated for several reasons. Endometriosis is a complex condition in which a genetic contribution and environmental factors seem to be involved.90 Further, it is a disease characterised by an yet poorly defined phenotype. The disease stage depends on the type (cysts, implants, nodules), location (ovary, peritoneum, bladder, ureter, etc), and appearance and depth of invasion of the lesions, which can vary greatly among patients. The clinical presentation can be so variable and the lesions of such diverse morphology that none of the pathogenetic models proposed (retrograde menstruation, coelomic metaplasia, embryological origin) can fully explain the various aspects of endometriosis, and none has been recognised as an ultimately valid explanatory model for all the different forms and manifestations of the disease.90 Moreover, an invasive procedure is needed to diagnose it.90 91 Furthermore, published studies differ in the case and control selection and population definition, depending on the choices to consider fertile or infertile cases, and healthy controls or patients with conditions other than endometriosis. Despite these possible sources of variation, the consistency of results observed weighs against any relevant role of tobacco on endometriosis.

In conclusion, the present meta-analysis failed to identify an association between tobacco smoking and endometriosis. However, given the possible limitations of the present study, further studies are needed to evaluate, in depth, the relationship and potential effect of smoking on different type of endometriosis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Mrs I Garimoldi for editorial assistance.

Footnotes

Contributors: FP conceived the idea and planned the research. FB and SC performed the statistical analysis. FB, FC, ER and VC retrieved the data. FP, FB, PV and CLV wrote the entire draft of the article and all subsequent drafts after critical review by all co-authors. All authors gave significant input in the preparation of the article and analysis. FP is the guarantor.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Donnez J, Van Langendonckt A, Casanas-Roux F et al. Current thinking on the pathogenesis of endometriosis. Gynecol Obstet Invest 2002;54(Suppl 1):52–8; discussion 59–62. 10.1159/000066295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moen MH, Muus KM. Endometriosis in pregnant and non-pregnant women at tubal sterilization. Hum Reprod 1991;6:699–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Matorras R, Rodiquez F, Pijoan JI et al. Epidemiology of endometriosis in infertile women. Fertil Steril 1995;63:34–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.[No authors listed] Prevalence and anatomical distribution of endometriosis in women with selected gynaecological conditions: results from a multicentric Italian study. Gruppo italiano per lo studio dell'endometriosi. Hum Reprod 1994;9:1158–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Calhaz-Jorge C, Mol BW, Nunes J et al. Clinical predictive factors for endometriosis in a Portuguese infertile population. Hum Reprod 2004;19:2126–31. 10.1093/humrep/deh374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aban M, Ertunc D, Tok EC et al. Modulating interaction of glutathione-S-transferase polymorphisms with smoking in endometriosis. J Reprod Med 2007;52:715–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cramer DW, Wilson E, Stillman RJ et al. The relation of endometriosis to menstrual characteristics, smoking, and exercise. JAMA 1986;255:1904–8. 10.1001/jama.1986.03370140102032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berube S, Marcoux S, Maheux R. Characteristics related to the prevalence of minimal or mild endometriosis in infertile women. Canadian Collaborative Group on Endometriosis. Epidemiology 1998;9:504–10. 10.1097/00001648-199809000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chapron C, Souza C, de Ziegler D et al. Smoking habits of 411 women with histologically proven endometriosis and 567 unaffected women. Fertil Steril 2010;94:2353–5. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2010.04.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.[No authors listed] Risk factors for pelvic endometriosis in women with pelvic pain or infertility. Gruppo Italiano per lo Studio dell’ endometriosi. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 1999;83:195–9. 10.1016/S0301-2115(98)00332-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hemmings R, Rivard M, Olive DL et al. Evaluation of risk factors associated with endometriosis. Fertil Steril 2004;81:1513–21. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2003.10.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Matalliotakis IM, Cakmak H, Fragouli YG et al. Epidemiological characteristics in women with and without endometriosis in the Yale series. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2008;277:389–93. 10.1007/s00404-007-0479-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Missmer SA, Hankinson SE, Spiegelman D et al. Incidence of laparoscopically confirmed endometriosis by demographic, anthropometric, and lifestyle factors. Am J Epidemiol 2004;160:784–96. 10.1093/aje/kwh275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Signorello LB, Harlow BL, Cramer DW et al. Epidemiologic determinants of endometriosis: a hospital-based case-control study. Ann Epidemiol 1997;7:267–741. 10.1016/S1047-2797(97)00017-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sanders SR, Cuneo SP, Turzillo AM. Effects of nicotine and cotinine on bovine theca interna and granulosa cells. Reprod Toxicol 2002;16:795–800. 10.1016/S0890-6238(02)00049-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vidal JD, VandeVoort CA, Marcus CB et al. In vitro exposure to environmental tobacco smoke induces CYP1B1 expression in human luteinized granulosa cells. Reprod Toxicol 2006;22:731–7. 10.1016/j.reprotox.2006.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miceli F, Minici F, Tropea A et al. Effects of nicotine on human luteal cells in vitro: a possible role on reproductive outcome for smoking women. Biol Reprod 2005;72:628–32. 10.1095/biolreprod.104.032318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Paksy K, Rajczy K, Forgacs Z et al. Effect of cadmium on morphology and steroidogenesis of cultured human ovarian granulosa cells. J Appl Toxicol 1997;17:321–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Piasek M, Laskey JW. Acute cadmium exposure and ovarian steroidogenesis in cycling and pregnant rats. Reprod Toxicol 1994;8:495–507. 10.1016/0890-6238(94)90032-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goncalves RB, Coletta RD, Silverio KG et al. Impact of smoking on inflammation: overview of molecular mechanisms. Inflamm Res 2011;60:409–24. 10.1007/s00011-011-0308-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA 2000;283:2008–12. 10.1001/jama.283.15.2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ottawa Hospital Research Institute. The Newcastel-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses.

- 23.Hamling J, Lee P, Weitkunat R et al. Facilitating meta-analyses by deriving relative effect and precision estimates for alternative comparisons from a set of estimates presented by exposure level or disease category. Stat Med 2008;27:954–70. 10.1002/sim.3013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials 1986;7:177–88. 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Greenland S. Quantitative methods in the review of epidemiologic literature. Epidemiol Rev 1987;9:1–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med 2002;21:1539–58. 10.1002/sim.1186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lau J, Antman EM, Jimenez-Silva J et al. Cumulative meta-analysis of therapeutic trials for myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 1992;327:248–54. 10.1056/NEJM199207233270406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thornton A, Lee P. Publication bias in meta-analysis: its causes and consequences. J Clin Epidemiol 2000;53:207–16. 10.1016/S0895-4356(99)00161-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M et al. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 1997;315:629–34. 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Darrow SL, Vena JE, Batt RE et al. Menstrual cycle characteristics and the risk of endometriosis. Epidemiology 1993;4:135–42. 10.1097/00001648-199303000-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Itoh H, Iwasaki M, Hanaoka T et al. Urinary phthalate monoesters and endometriosis in infertile Japanese women. Sci Total Environ 2009;408:37–42. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2009.09.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Buck Louis GM, Chen Z, Peterson CM et al. Persistent lipophilic environmental chemicals and endometriosis: the ENDO Study. Environ Health Perspect 2012;120:811–16. 10.1289/ehp.1104432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Beral V, Rolfs R, Joesoef MR et al. Primary infertility: characteristics of women in North America according to pathological findings. J Epidemiol Community Health 1994;48:576–9. 10.1136/jech.48.6.576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cooney MA, Buck Louis GM, Hediger ML et al. Organochlorine pesticides and endometriosis. Reprod Toxicol 2010;30:365–9. 10.1016/j.reprotox.2010.05.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ferrero S, Pretta S, Bertoldi S et al. Increased frequency of migraine among women with endometriosis. Hum Reprod 2004;19:2927–32. 10.1093/humrep/deh537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Louis GM, Weiner JM, Whitcomb BW et al. Environmental PCB exposure and risk of endometriosis. Hum Reprod 2005;20:279–85. 10.1093/humrep/deh575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gagne D, Rivard M, Page M et al. Blood leukocyte subsets are modulated in patients with endometriosis. Fertil Steril 2003;80:43–53. 10.1016/S0015-0282(03)00552-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Grodstein F, Goldman MB, Cramer DW. Infertility in women and moderate alcohol use. Am J Public Health 1994;84:1429–32. 10.2105/AJPH.84.9.1429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Grodstein F, Goldman MB, Ryan L et al. Relation of female infertility to consumption of caffeinated beverages. Am J Epidemiol 1993;137:1353–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Heilier JF, Verougstraete V, Nackers F et al. Assessment of cadmium impregnation in women suffering from endometriosis: a preliminary study. Toxicol Lett 2004;154:89–93. 10.1016/j.toxlet.2004.07.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Marino JL, Holt VL, Chen C et al. Shift work, hCLOCK T3111C polymorphism, and endometriosis risk. Epidemiology 2008;19:477–84. 10.1097/EDE.0b013e31816b7378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nagle CM, Bell TA, Purdie DM et al. Relative weight at ages 10 and 16 years and risk of endometriosis: a case-control analysis. Hum Reprod 2009;24:1501–6. 10.1093/humrep/dep048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Phipps WR, Cramer DW, Schiff I et al. The association between smoking and female infertility as influenced by cause of the infertility. Fertil Steril 1987;48:377–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Trabert B, De Roos AJ, Schwartz SM et al. Non-dioxin-like polychlorinated biphenyls and risk of endometriosis. Environ Health Perspect 2010;118:1280–5. 10.1289/ehp.0901444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tsuchiya M, Tsukino H, Iwasaki M et al. Interaction between cytochrome P450 gene polymorphisms and serum organochlorine TEQ levels in the risk of endometriosis. Mol Hum Reprod 2007;13:399–404. 10.1093/molehr/gam018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tsukino H, Hanaoka T, Sasaki H et al. Associations between serum levels of selected organochlorine compounds and endometriosis in infertile Japanese women. Environ Res 2005;99:118–25. 10.1016/j.envres.2005.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Upson K, De Roos AJ, Thompson ML et al. Organochlorine pesticides and risk of endometriosis: findings from a population-based case-control study. Environ Health Perspect 2013;121:1319–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Louis GM, Peterson CM, Chen Z et al. Perfluorochemicals and endometriosis: the ENDO study. Epidemiology 2012;23:799–805. 10.1097/EDE.0b013e31826cc0cf [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Andolf E, Thorsell M, Kallen K. Caesarean section and risk for endometriosis: a prospective cohort study of Swedish registries. BJOG 2013;120:1061–5. 10.1111/1471-0528.12236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Buck Louis GM, Hediger ML, Pena JB. Intrauterine exposures and risk of endometriosis. Hum Reprod 2007;22:3232–6. 10.1093/humrep/dem338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cayan F, Ertunc D, Aras-Ates N et al. Association of G1057D variant of insulin receptor substrate-2 with endometriosis. Fertil Steril 2010;94:1622–6. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.09.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Coccia ME, Rizzello F, Mariani G et al. Ovarian surgery for bilateral endometriomas influences age at menopause. Hum Reprod 2011;26:3000–7. 10.1093/humrep/der286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dhillon PK, Holt VL. Recreational physical activity and endometrioma risk. Am J Epidemiol 2003;158:156–64. 10.1093/aje/kwg122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Eskenazi B, Mocarelli P, Warner M et al. Serum dioxin concentrations and endometriosis: a cohort study in Seveso, Italy. Environ Health Perspect 2002;110:629–34. 10.1289/ehp.02110629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Falconer H, Sundqvist J, Xu H et al. Analysis of common variations in tumor-suppressor genes on chr1p36 among Caucasian women with endometriosis. Gynecol Oncol 2012;127:398–402. 10.1016/j.ygyno.2012.08.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ferrero S, Petrera P, Colombo BM et al. Asthma in women with endometriosis. Hum Reprod 2005;20:3514–17. 10.1093/humrep/dei263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Heilier JF, Donnez J, Nackers F et al. Environmental and host-associated risk factors in endometriosis and deep endometriotic nodules: a matched case-control study. Environ Res 2007;103:121–9. 10.1016/j.envres.2006.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hoffman CS, Small CM, Blanck HM et al. Endometriosis among women exposed to polybrominated biphenyls. Ann Epidemiol 2007;17:503–10. 10.1016/j.annepidem.2006.11.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Huang PC, Tsai EM, Li WF et al. Association between phthalate exposure and glutathione S-transferase M1 polymorphism in adenomyosis, leiomyoma and endometriosis. Hum Reprod 2010;25:986–94. 10.1093/humrep/deq015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Huber A, Keck CC, Hefler LA et al. Ten estrogen-related polymorphisms and endometriosis: a study of multiple gene-gene interactions. Obstet Gynecol 2005;106(5 Pt 1):1025–31. 10.1097/01.AOG.0000185259.01648.41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jackson LW, Zullo MD, Goldberg JM. The association between heavy metals, endometriosis and uterine myomas among premenopausal women: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1999–2002. Hum Reprod 2008;23:679–87. 10.1093/humrep/dem394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kortelahti M, Anttila MA, Hippelainen MI et al. Obstetric outcome in women with endometriosis—a matched case-control study. Gynecol Obstet Invest 2003;56:207–12. 10.1159/000074815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lebel G, Dodin S, Ayotte P et al. Organochlorine exposure and the risk of endometriosis. Fertil Steril 1998;69:221–8. 10.1016/S0015-0282(97)00479-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Marino JL, Holt VL, Chen C et al. Lifetime occupational history and risk of endometriosis. Scand J Work Environ Health 2009;35:233–40. 10.5271/sjweh.1317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.McCarty CA, Berg RL, Welter JD et al. A novel gene-environment interaction involved in endometriosis. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2012;116:61–3. 10.1016/j.ijgo.2011.10.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Moen MH, Schei B. Epidemiology of endometriosis in a Norwegian county. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 1997;76:559–62. 10.3109/00016349709024584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Niskar AS, Needham LL, Rubin C et al. Serum dioxins, polychlorinated biphenyls, and endometriosis: a case-control study in Atlanta. Chemosphere 2009;74:944–9. 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2008.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Parazzini F, Cipriani S, Bianchi S et al. Risk factors for deep endometriosis: a comparison with pelvic and ovarian endometriosis. Fertil Steril 2008;90:174–9. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.05.059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Pauwels A, Schepens PJ, D'Hooghe T et al. The risk of endometriosis and exposure to dioxins and polychlorinated biphenyls: a case-control study of infertile women. Hum Reprod 2001;16:2050–5. 10.1093/humrep/16.10.2050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Pollack AZ, Louis GM, Chen Z et al. Trace elements and endometriosis: the ENDO study. Reprod Toxicol 2013;42:41–8. 10.1016/j.reprotox.2013.05.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Porpora MG, Medda E, Abballe A et al. Endometriosis and organochlorinated environmental pollutants: a case-control study on Italian women of reproductive age. Environ Health Perspect 2009;117:1070–5. 10.1289/ehp.0800273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sangi-Haghpeykar H, Poindexter AN III. Epidemiology of endometriosis among parous women. Obstet Gynecol 1995;85:983–92. 10.1016/0029-7844(95)00074-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Treloar SA, Bell TA, Nagle CM et al. Early menstrual characteristics associated with subsequent diagnosis of endometriosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2010;202:534 e1–6. 10.1016/j.ajog.2009.10.857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Tsai CW, Ho CY, Shih LC et al. The joint effect of hOGG1 genotype and smoking habit on endometriosis in Taiwan. Chin J Physiol 2013;56:263–8. 10.4077/CJP.2013.BAB142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Tsuchiya M, Miura T, Hanaoka T et al. Effect of soy isoflavones on endometriosis: interaction with estrogen receptor 2 gene polymorphism. Epidemiology 2007;18:402–8. 10.1097/01.ede.0000257571.01358.f9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Tu FF, Du H, Goldstein GP et al. The influence of prior oral contraceptive use on risk of endometriosis is conditional on parity. Fertil Steril 2014;101:1697–704. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2014.02.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.D’ Avanzo B, La Vecchia C, Katsouyanni K et al. Reliability of information on cigarette smoking and beverage consumption provided by hospital controls. Epidemiology 1996;7:312–15. 10.1097/00001648-199605000-00018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lee MM, Whittemore AS, Lung DL. Reliability of recalled physical activity, cigarette smoking, and alcohol consumption. Ann Epidemiol 1992;2:705–14. 10.1016/1047-2797(92)90015-I [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Patrick DL, Cheadle A, Thompson DC et al. The validity of self-reported smoking: a review and meta-analysis. Am J Public Health 1994;84:1086–93. 10.2105/AJPH.84.7.1086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kirshon B, Poindexter AN III. Contraception: a risk factor for endometriosis. Obstet Gynecol 1988;71(6 Pt 1):829–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Parazzini F, Ferraroni M, Fedele L et al. Pelvic endometriosis: reproductive and menstrual risk factors at different stages in Lombardy, northern Italy. J Epidemiol Community Health 1995;49:61–4. 10.1136/jech.49.1.61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Candiani GB, Danesino V, Gastaldi A et al. Reproductive and menstrual factors and risk of peritoneal and ovarian endometriosis. Fertil Steril 1991;56:230–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Baron JA, La Vecchia C, Levi F. The antiestrogenic effect of cigarette smoking in women. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1990;162:502–14. 10.1016/0002-9378(90)90420-C [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Boucher A, Mourad W, Mailloux J et al. Ovarian hormones modulate monocyte chemotactic protein-1 expression in endometrial cells of women with endometriosis. Mol Hum Reprod 2000;6:618–26. 10.1093/molehr/6.7.618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Osteen KG, Bruner KL, Sharpe-Timms KL. Steroid and growth factor regulation of matrix metalloproteinase expression and endometriosis. Semin Reprod Endocrinol 1996;14:247–55. 10.1055/s-2007-1016334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Parazzini F, La Vecchia C, Bocciolone L et al. The epidemiology of endometrial cancer. Gynecol Oncol 1991;41:1–16. 10.1016/0090-8258(91)90246-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Parazzini F, Negri E, La Vecchia C et al. Uterine myomas and smoking. Results from an Italian study. J Reprod Med 1996;41:316–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Boffetta P, McLaughlin JK, La Vecchia C et al. False-positive results in cancer epidemiology: a plea for epistemological modesty. J Natl Cancer Inst 2008;100:988–95. 10.1093/jnci/djn191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Smoking and infertility: a committee opinion. Fertil Steril 2012;98:1400–6. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.07.1146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Viganò P, Somigliana E, Panina P et al. Principles of phenomics in endometriosis. Hum Reprod Update 2012;18:248–59. 10.1093/humupd/dms001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Gentilini D, Perino A, Vigano P et al. Gene expression profiling of peripheral blood mononuclear cells in endometriosis identifies genes altered in non-gynaecologic chronic inflammatory diseases. Hum Reprod 2011;26:3109–17. 10.1093/humrep/der270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.