Abstract

Objectives

To investigate the impact of Australia's plain tobacco packaging policy on two stated purposes of the legislation—increasing the impact of health warnings and decreasing the promotional appeal of packaging—among adult smokers.

Design

Serial cross-sectional study with weekly telephone surveys (April 2006–May 2013). Interrupted time-series analyses using ARIMA modelling and linear regression models were used to investigate intervention effects.

Participants

15 745 adult smokers (aged 18 years and above) in New South Wales (NSW), Australia. Random selection of participants involved recruiting households using random digit dialling and selecting the nth oldest smoker for interview.

Intervention

The introduction of the legislation on 1 October 2012.

Outcomes

Salience of tobacco pack health warnings, cognitive and emotional responses to warnings, avoidance of warnings, perceptions regarding one's cigarette pack.

Results

Adjusting for background trends, seasonality, antismoking advertising activity and cigarette costliness, results from ARIMA modelling showed that, 2–3 months after the introduction of the new packs, there was a significant increase in the absolute proportion of smokers having strong cognitive (9.8% increase, p=0.005), emotional (8.6% increase, p=0.01) and avoidant (9.8% increase, p=0.0005) responses to on-pack health warnings. Similarly, there was a significant increase in the proportion of smokers strongly disagreeing that the look of their cigarette pack is attractive (57.5% increase, p<0.0001), says something good about them (54.5% increase, p<0.0001), influences the brand they buy (40.6% increase, p<0.0001), makes their pack stand out (55.6% increase, p<0.0001), is fashionable (44.7% increase, p<0.0001) and matches their style (48.1% increase, p<0.0001). Changes in these outcomes were maintained 6 months postintervention.

Conclusions

The introductory effects of the plain packaging legislation among adult smokers are consistent with the specific objectives of the legislation in regard to reducing promotional appeal and increasing effectiveness of health warnings.

Keywords: PUBLIC HEALTH, PREVENTIVE MEDICINE

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Study strengths are: the use of population-level data collected over a long time period, with a large sample of adult smokers; the use of a time-series approach with multiple data points before the intervention; and the inclusion of important time-related and sample-related potential covariates.

Limitations of the study include the use of landline-only telephone numbers and a somewhat low response rate, potentially leading to some bias in sample composition. The response rate was consistent across the study period, limiting the impact on study findings.

On 1 December 2012, Australia became the first country to introduce mandatory plain packaging for all tobacco products.1 The new plain packs are olive green cardboard packages devoid of all brand design elements, with brand name and number of cigarettes written in a standardised font and location on each pack. The new packs continue to carry coloured graphic health warnings (GHWs) covering 90% of the back of packs, with the warnings on the front of the pack enlarged from 30% to 75%. Manufacturers were required to produce the new packs from 1 October 2012 and they started appearing for sale from that date; approximately 80% of smokers were using plain packs by mid-November.2

The plain packaging legislation aims to discourage people from taking up smoking, encourage smokers to give up smoking and discourage relapse.1 The stated purpose of the legislation is to regulate the packaging and appearance of tobacco products in order to: (1) reduce the appeal of tobacco products to consumers, (2) increase the effectiveness of health warnings and (3) reduce the ability of packaging to mislead consumers about the harmful effects of smoking. As this was the first time any such legislation had been implemented, the expected outcomes of the new packs were informed by a body of research consisting primarily of experimental studies, summarised in recent reviews.3–6

Studies in which participants were presented with mocked-up plain and branded tobacco packs show that plain packaging has the potential to reduce the promotional appeal of a pack, diminish positive perceptions about smokers of cigarettes from that pack and reduce the appeal of smoking in general.7–13 Such studies also suggest that health warnings are both more noticeable and more effective when presented on plain rather than branded packs,14 15 with researchers suggesting that brand imagery diffuses the impact of health warnings.16 These results have been corroborated in naturalistic studies in which smokers are assigned to smoke their normal cigarettes from either plain or branded packs for a period of time, with plain pack smokers reporting increased negative perceptions about their packs and about smoking, along with an increased impact of health warnings.17 18 A limitation of these previous studies, however, is the inability to differentiate the impact of plain packaging from the novelty impact of a pack, which is simply different from the packs that smokers are used to seeing. No studies to date have been able to investigate the impact of plain tobacco packaging on tobacco pack appeal and the salience and effects of health warnings in the context of mandatory plain packaging, when all packs with which smokers are in contact are devoid of any branding other than a name in a standard font.

In the current study, we use cross-sectional survey data collected weekly for a period of 7 years to investigate the impact of the new packaging on adult smokers’ responses to the health warnings on their packs and perceptions of their packs. It was hypothesised that, after the introduction of the new packs, smokers would find the health warnings more salient, would have an increased response to the warnings, and would hold less favourable perceptions of their packs. The continuous nature of the data allowed us to track how these outcomes changed after the introduction of the new packs, investigating whether any observed changes were sustained in the 6 months following their introduction. This approach builds on our previous study evaluating the impact of the introduction of the plain packaging legislation on calls to a smoking cessation helpline.19 Additionally, given that responses to graphic pack warnings had been tracked since their initial introduction in 2006, we were able to assess changes in these responses in the context of longer term trends.

Method

Study design and participants

The Cancer Institute's Tobacco Tracking Survey (CITTS) is a serial cross-sectional telephone survey with approximately 50 interviews conducted per week throughout the year. The CITTS monitors smoking-related cognitions and behaviours among adult smokers and recent quitters (quit in the past 12 months) in New South Wales (NSW), Australia's most populous state. Households are recruited using random digit dialling (landline telephone numbers only) and a random selection procedure is used to recruit participants within households (selecting the nth oldest eligible adult). Analyses for this study are limited to smokers interviewed between April 2006 and May 2013 (total n=15 745), with an average response rate of 40% (American Association for Public Opinion Research Response Rate #4).20

Outcome measures

Following the introduction of the original graphic health warnings on tobacco packs in March 2006, questions were included in the CITTS relating to smokers’ responses to the warnings. These questions assessed cognitive response to the warnings (‘the graphic warnings encourage me to stop smoking’) and emotional response (‘with the graphic warnings, each time I get a cigarette out I worry that I shouldn't be smoking’). From April 2007, warning avoidance was also assessed (‘they make me feel that I should hide or cover my packet from the view of others’). From October 2011, the salience of the warnings was also assessed (‘the only thing I notice on my cigarette pack is the graphic warnings’). All answers were given on a 5-point Likert scale (1=strongly disagree–5=strongly agree). The distributions of responses to these items over the study period are shown in online supplementary figure S1. Responses to these items were used in two ways. The first was collapsing responses for each item into a binary variable indicating strong agreement versus not. The second was averaging the responses to these items to create a scale indicating ‘Graphic Health Warning Impact’, with higher scores indicating greater overall impact (Cronbach's α=0.70).

From October 2011, smokers were asked a battery of questions relating to their perceptions of their packs: ‘The look of my cigarette pack…’ (1) is attractive; (2) says something good about me to other smokers; (3) influences the brand I buy; (4) makes my brand stand out from other brands; (5) is fashionable; and (6) matches my style (1=strongly disagree–5=strongly agree). Distributions of responses to these items over the study period are shown in online supplementary figure S2. Responses to each item were dichotomised into strongly disagree versus not, and they were also reverse scored and averaged to create a scale indicating ‘Negative Pack Perceptions’ (Cronbach's α=0.87), with higher scores indicating more negative perceptions.

Covariates

Data on sex, age, total household income and educational attainment (low=less than high school; moderate=high school diploma or vocational college; high=tertiary) were included in the CITTS. Socioeconomic status (SES) was indicated by a variable that combined responses to household income and educational attainment.21 22 High SES was defined as having a household income of more than AUD$80 000 (and any education level), or an income of AUD$40–80 000 and moderate-high education. Moderate SES was defined as either an income below AUD$40 000 and high education, or an income of AUD$40–80 000 and moderate education. Low SES was defined as either an income below AUD$40 000 and low or moderate education, or an income AUD$40–80 000 and low education. Those with missing data on one variable were classified based on the other.

Frequency of smoking was used to classify smokers as ‘daily’, ‘weekly’ or ‘less frequent’ smokers. The average number of cigarettes smoked per day was used to indicate heaviness of smoking (light=less than 10 cigarettes per day; moderate=11–20 cigarettes per day; heavy=more than 20 cigarettes per day). As smokers’ responses to GHWs and perceptions of their cigarette packs might conceivably be related to their quitting experiences or propensity towards quitting, we also included quit attempts in the past 12 months as a control variable (1=tried to quit at least once in the past 12 months, 0=did not).

Respondents’ pack perceptions and responses to health warnings might also possibly be influenced by the timing of their interview in terms of variations in antismoking advertising activity, changes in the costliness of cigarettes or shifting social norms. Respondents’ level of exposure to antismoking advertising in the 3 months prior to their interview was measured in terms of Target Audience Rating Points (TARPs). TARPs are a product of the percentage of the target audience exposed to an advertisement (reach) and the average number of times a target audience member would be exposed (frequency). Hence, 200 TARPs might represent 100% of the target audience receiving the message an average of two times over a specified period, or 50% reached four times. Exposure to advertising over a 3-month period was chosen based on previous research suggesting that advertising effects occur within this time frame.22 23 We ascertained TARPs for each of the advertisements broadcast in NSW during the study period based on OZTAM Australian TV Audience Measurements for adults aged 18 years and older for free-to-air and cable TV (M=1590, SD=758).24

A variable indicating cigarette costliness25 at the time of the interview was calculated as the ratio of the average quarterly recommended retail pack price of the two top-selling Australian cigarette brands (obtained from the retail trade magazine Australian Retail Tobacconist, volumes 65–87) to the average weekly earnings in the same quarter (M=1.54, SD=0.17).26

The influence of changing social norms was accounted for by statistically accounting for a time-based trend in the data, described below.

Statistical analyses

Two approaches to statistical analysis were used to assess the impact of the new packs on each outcome. The first approach used interrupted time series analysis, in which data collected at multiple instances before and after an intervention are used to detect whether the intervention has an effect significantly greater than the underlying secular trend. The advantages of using this approach include the ability to account for background trends, control for seasonal variations, adjust for autocorrelation in the data (when each value is correlated with the previous value), and to assess changes in the outcome in the context of longer term trends. We also used multiple linear regression analyses to compare the scores for the two constructed scales in the months prior to and following the new packaging legislation, controlling for sociodemographic and smoking characteristics.

In the time-series analysis, weekly data were aggregated at the monthly level (to ensure sufficient sample size at each time point). We assessed the impact of the introduction of the new packs on (1) the proportion of the sample strongly agreeing with each of the GHW statements, (2) the mean GHW Impact score, (3) the proportion of the sample strongly disagreeing with each of the pack perception statements and (4) the mean Negative Pack Perception score. We used autoregressive integrated moving average (ARIMA) analysis in SAS V.9.327 to model the effects of the introduction of the new packaging on the outcomes of interest, while accounting for background trends, seasonal variation, the effects of television antitobacco advertising, and changes in cigarette costliness. ARIMA modelling was chosen because the data for each of the outcomes of interest were autocorrelated.

ARIMA modelling comprising model investigation, estimation and diagnostic checking followed the methods of Box et al.28 This modelling enables investigation of the size and statistical significance of changes in an outcome after a specified time point, adjusting for background trends and confounders. An indicator term was created to represent the week of the introduction of the intervention (the ‘phasing in’ of the new packs on 1 October 2012). The potential confounders of antismoking advertising activity (TARPs) and cigarette costliness were included in all models. In the models predicting responses to GHWs, terms indicating the months of December and January were also included to account for the potential for seasonal variations (not included for pack perception outcomes due to limited data points). Owing to the large number of outcomes to be reported, we do not report the effects of these covariates (available from authors on request).

Next, we used multiple linear regression analyses to assess changes in scores on the GHW Impact and Negative Pack Perception scales, using month of interview as the indicator, focusing on the period of the introduction of the new packs (August 2012–May 2013).29 The months preceding and following the intervention were represented by a five-level term: (1) the 2 months preceding the change (August–September, ‘pre-plain packs (PP)’); (2) the 2 months of ‘phase-in’ (October–November); (3) the 2 months ‘immediate post-PP’ (December–January); (4) ‘3–4 months post-PP’ (February–March); and (5) ‘5–6 months post-PP’ (April-May). Demographic and smoking characteristics were included as covariates, along with recent antismoking advertising activity. Since changes in cigarette costliness were based on quarterly data, there was a high degree of multicollinearity between costliness and time of interview (VIF=26), resulting in inflated SEs and unstable estimates of regression coefficients. We therefore included a variable indicating ‘increase in cigarette costliness’ in the past 12 weeks (as a percentage of costliness) as a covariate in these models. To provide a point of comparison, these models were also fitted to 2011–2012 data for the same months. An α level of 0.05 was used for all statistical tests. Stata V.11 was used for the regression analyses.30

Owing to a slight over-representation of females, older respondents and regional residents (living outside the capital city) in the CITTS sample compared to the NSW population,31 weights were constructed using age, sex and region of residence to make the sample more similar to the NSW population. Weights were applied in the multiple linear regression analyses (using ‘p’ weights).

Results

The response rate for the survey was an average of 40% in the period 2006–2013.

Sample characteristics are shown in table 1.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics from the Cancer Institute's Tobacco Tracking Survey (CITTS) April 2006–May 2012 (smokers only; n=15 745)

| N | Per cent | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Female | 8298 | 50 |

| Male | 7503 | 50 |

| Age (years) | ||

| 18–29 | 2405 | 21 |

| 30–55 | 8470 | 48 |

| 55+ | 4924 | 31 |

| Socioeconomic status | ||

| Low | 6577 | 41 |

| Moderate | 4071 | 27 |

| High | 4974 | 33 |

| Smoking frequency | ||

| Daily | 14 025 | 88 |

| Weekly | 950 | 6 |

| Less than weekly | 826 | 6 |

| Smoking | ||

| Low | 5827 | 41 |

| Moderate | 5837 | 38 |

| High | 3473 | 22 |

| Quit attempts in past 12 m | ||

| None | 9443 | 60 |

| At least one | 6145 | 40 |

| Year | ||

| 2006 | 1600 | 10 |

| 2007 | 2289 | 15 |

| 2008 | 2094 | 13 |

| 2009 | 2135 | 14 |

| 2010 | 2146 | 14 |

| 2011 | 2157 | 14 |

| 2012 | 2126 | 13 |

| 2013 | 1254 | 8 |

Ns are unweighted, %s are weighted for age, sex and regional residence.

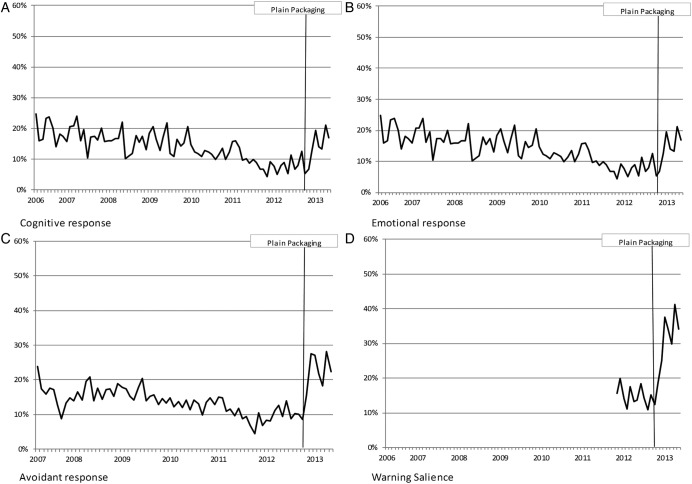

Responses to GHWs

Figure 1 shows the monthly proportions of the smoker sample strongly agreeing with each of the GHW responses over time. In general, strong agreement about the impact of the warnings had been decreasing since their introduction in 2006. Of the smokers interviewed in 2006: 21% reported strong cognitive responses to the warnings, decreasing to 12% in 2011; and 20% reported strong emotional responses, decreasing to 12% in 2011.

Figure 1.

Monthly proportions of smokers strongly agreeing that: (A) the graphic warnings encourage me to stop smoking (cognitive response); (B) with the graphic warnings, each time I get a cigarette out I worry that I should not be smoking (emotional response); (C) they make me feel that I should hide or cover my packet from the view of others (avoidant response); (D) the only thing I notice on my cigarette pack is the graphic warnings (warning salience).

The results of the interrupted time series analyses investigating the impact of the new packaging on responses to GHWs are shown in table 2. For all models, the residuals were uncorrelated and normally distributed and all other model diagnostics indicated a suitable model fit. After controlling for background trends, seasonality, antismoking advertising activity and cigarette costliness, there was a significant increase in the proportion of smokers having strong cognitive, emotional and avoidant responses to graphic warnings after the introduction of the new packs. The increase in the avoidant response occurred 2 months after the new packs were introduced (from 10% in September 2012 to 28% in December), and the increase in cognitive and emotional responses occurred after 3 months (cognitive: from 13% in September 2012 to 20% in January 2013; emotional: from 13% to 27%). In the time-series analysis, the change in the proportion of smokers strongly agreeing that the warnings were the only thing they noticed on their packs after the introduction of the new packs was not significant.

Table 2.

Results of interrupted time series analyses investigating the impact of new tobacco packaging on smokers’ responses to graphic health warnings and pack attitudes

| Increase in % strongly agree (95% CI) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|

| Responses to graphic health warnings | ||

| Cognitive* | 9.8 (3.0 to 16.5) | 0.005 |

| Emotional* | 8.6 (1.7 to 15.4) | 0.010 |

| Avoidant† | 9.8 (4.2 to 15.3) | <0.001 |

| Warning salience‡ | 2.5 (−10.1 to 15.1) | 0.700 |

| GHW impact‡ | 0.38 (0.05 to 0.70)§ | 0.02 |

| Increase in % strongly disagree (95% CI) | ||

| Pack perceptions | ||

| Attractive‡ | 57.5 (38.0 to 77.1) | <0.001 |

| Says something good about me‡ | 54.5 (36.9 to 72.1) | <0.001 |

| Influences the brand I buy‡ | 40.6 (23.2 to 58.0) | <0.001 |

| Makes my brand stand out‡ | 55.6 (35.0 to 76.2) | <0.001 |

| Is fashionable‡ | 44.7 (28.1 to 61.2) | <0.001 |

| Matches my style‡ | 48.1 (32.2 to 64.0) | <0.001 |

| Negative Pack Perceptions‡ | 0.21 (0.02 to 0.40)§ | 0.03 |

All models adjusted for TARPs, cigarette costliness and seasonal variations (where possible); full results available from authors on request; all effects occurred at 3 months lag, except for ‘avoidant’ responses to the graphic health warnings and GHW Impact (2-month lag).

*Data available April 2006–May 2013.

†Data available April 2007–May 2013.

‡Data available October 2011–May 2013.

§Increase in Mean score.

GHW, graphic health warning.

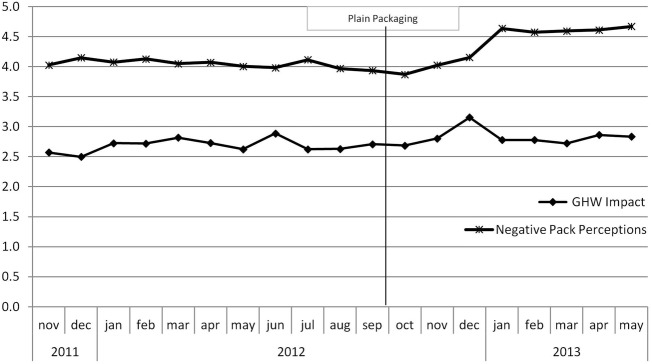

The monthly average of the GHW Impact scale is shown in figure 3. The results of the interrupted time series analysis investigating the impact of the new packaging on GHW Impact scores are shown in table 2. The residuals were uncorrelated and normally distributed, and all other model diagnostics indicated a suitable model fit. There was a significant increase in scores on the GHW Impact scale 2 months after the introduction of the new packs, not attributable to background trends, seasonality, antismoking advertising activity or cigarette costliness.

Figure 3.

Monthly mean score for Graphic Health Warning Impact and Negative Pack Perception.

The results of the multiple linear regression model predicting scores on the GHW Impact scale are shown in table 3. Compared with the preplain packaging period (August/September 2012), scores on the scale were significantly higher in the immediate postplain packaging period (December/January) and in the 5–6 month postplain packaging period (April/May). These effects were independent of any differences between the samples on socio-demographic or smoking characteristics, antismoking advertising activity or increases in cigarette costliness. There were no significant differences in scores on this scale over the months of the comparison period.

Table 3.

Results from linear regression models predicting Graphic Health Warning Impact and Negative Pack Perceptions from month of interview in the plain packaging and comparison periods

| Comparison period (2011–2012) |

Plain packaging period (2012–2013) |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | (SD) | β | 95% CI |

p Value | M | (SD) | β | 95% CI |

p Value | |||

| GHW impact | ||||||||||||

| Month | ||||||||||||

| Aug/Sept | NA | 2.67 | (0.93) | Ref | ||||||||

| Oct/Nov | 2.57 | (0.90) | Ref | 2.75 | (0.97) | 0.00 | −0.16 | 0.18 | 0.932 | |||

| Dec/Jan | 2.62 | (0.99) | −0.01 | −0.25 | 0.21 | 0.847 | 2.88 | (1.16) | 0.09 | 0.07 | 0.46 | 0.008 |

| Feb/March | 2.77 | (0.89) | 0.10 | −0.19 | 0.58 | 0.323 | 2.75 | (1.15) | 0.07 | −0.04 | 0.39 | 0.110 |

| April/May | 2.67 | (0.96) | −0.01 | −0.52 | 0.48 | 0.930 | 2.85 | (1.21) | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.34 | 0.043 |

| Negative pack perceptions | ||||||||||||

| Month | ||||||||||||

| Aug/Sept | NA | 3.95 | (0.76) | Ref | ||||||||

| Oct/Nov | 4.03 | (0.60) | Ref | 3.96 | (0.75) | 0.02 | −0.47 | 1.06 | 0.449 | |||

| Dec/Jan | 4.11 | (0.64) | 0.06 | −0.43 | 1.46 | 0.286 | 4.50 | (0.63) | 0.27 | 2.74 | 4.18 | <0.001 |

| Feb/March | 4.08 | (0.59) | 0.03 | −1.40 | 1.88 | 0.775 | 4.58 | (0.61) | 0.37 | 3.14 | 4.75 | <0.001 |

| April/May | 4.03 | (0.69) | 0.07 | −1.61 | 2.80 | 0.598 | 4.64 | (0.63) | 0.40 | 3.87 | 5.21 | <0.001 |

Models controlled for demographics (sex, age, SES), smoking characteristics (frequency and level of smoking, 12 m quitting history), antismoking advertising activity (TARPs), and recent increases in cigarette costliness (% increase in past 12 weeks); M's and SD's are unweighted.

β, standardised coefficient; GHW, graphic health warnings; M, Mean (range 1–5).

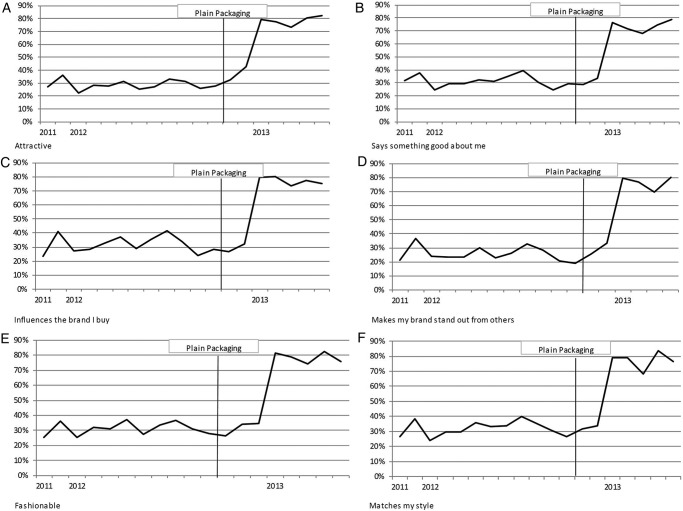

Pack perceptions

The monthly proportions of smokers strongly disagreeing with each of the pack attitude items are shown in figure 2. The results of the interrupted time series analysis (table 2) show that, 3 months following the introduction of the new packs, there was a significant increase in the proportion of smokers strongly disagreeing that the look of their cigarette pack is attractive (from 26% in September 2012 to 80% in January 2013), says something good about them (from 27% to 76%), influences the brand they buy (from 27% to 77%), makes their brand stand out (from 22% to 78%), is fashionable (from 27% to 80%), and matches their style (from 31% to 77%). This effect was independent of any influence of long-term background trends, cigarette costliness or antismoking advertising activity.

Figure 2.

Monthly proportions of smokers strongly disagreeing that their cigarette pack is: (A) attractive; (B) says something good about me to other smokers; (C) influences the brand I buy; (D) makes my brand stand out from other brands; (E) is fashionable; (F) matches my style.

The monthly average of the Negative Pack Perception scale is shown in figure 3, and the results of the interrupted time series analysis investigating the impact of the new packaging on these scores are shown in table 2. The residuals were uncorrelated and normally distributed, and all other model diagnostics indicated a suitable model fit. There was a significant increase in scores on the Negative Pack Perception scale 3 months after the introduction of the new packs, not attributable to background trends, seasonality, antismoking advertising activity or cigarette costliness.

The multiple linear regression model predicting Negative Pack Perception scores over the pp-periods showed that scores on this scale were significantly higher in each of the post-pp periods than in the pre-pp period (table 3). For the comparison period, there were no significant differences in scores on this scale.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the population-level impact of the new tobacco plain packs on Australian adult smokers’ responses to their packs. This is an important first step in evaluating the policy as these outcomes relate closely to the intended purpose of the legislation. In the months following the introduction of the new packs, there was an increase in the proportion of smokers reporting strong cognitive and emotional responses to the warnings, avoidant behaviours related to the on-pack warnings, and salience of warnings. There was also an increase in the proportion of smokers with strong negative perceptions about their packs. These changes were not attributed to variations in exposure to antismoking advertising activity, tobacco prices, secular trends, seasonality or changes in sample composition.

Consistent with the results of experimental research,14 15 17 we found that the introduction of the new packs was associated with an increase in the salience and the self-reported impact of the health warnings, such that smokers were more likely to report that the warnings are the only thing they see on their packs, that they feel they should hide or cover their pack, that the warnings encourage them to stop smoking, and that they make them worry that they should not be smoking. Prominent GHWs on tobacco products have been shown to increase health knowledge and perceptions of risk from smoking,32 33 reduce consumption levels and increase cessation behaviour among smokers,33 34 and support former smokers in remaining abstinent.35 Importantly, the impact of GHWs on smoking behaviours appears to be a function of the depth of smokers’ cognitive processing of and responses to the warnings (such as those monitored in this study),34–36 suggesting that if plain packaging can intensify smokers’ responses to warnings, flow-on effects on consumption and quitting are likely.

Research shows that the impact of pictorial health warnings declines over time.33 37 Of note is the fact that the introduction of the new packs appears to have reversed a downward trend in smokers’ cognitive, emotional and avoidant responses to the GHWs that had been occurring since their initial introduction. On the current plain packaging, the warnings are having an equal or greater impact on adult smokers than they have since their inception. Owing to the simultaneous introduction of the plain packs and changes in the size and content of the warnings themselves, the relative contribution of the warning and pack changes to this increase in smoker responses cannot be determined in this study. Nonetheless, recent evidence from eye-tracking studies suggests that plain packing itself can increase visual attention towards warning information on cigarette packs.38 39 Future research should assess whether the downward trend in responses to health warnings resumes following the introductory period of plain packaging.

Extending experimental evidence on the influence of plain packaging on brand appeal,7–9 40 this study demonstrates an impact of the new packs on adult smokers’ perceptions that their own packs are fashionable or attractive, that they match their style or say something good about them to other smokers, or that the pack makes their brand stand out or influences the brand they buy. There is a wide body of evidence from the marketing literature that shows how branding and packaging can modify the expected and actual subjective experience of products.41 Notably, changes in the way smokers perceive their pack have the potential to augment smokers’ subjective experience of smoking, leading to a more negative perception of the taste of their cigarettes and less enjoyment in the act of smoking.7 Indeed, anecdotal evidence suggests that Australian smokers reported that their cigarettes tasted worse with the introduction of plain packaging,42 43 and smokers smoking from plain packs during the phase-in period perceived their cigarettes to be less satisfying and lower in quality than a year ago.2 The likely impact of changes in the perceived experience of smoking is an important avenue for future studies, but research identifying enjoyment of smoking as a barrier to quitting suggests that smokers who find their smoking less enjoyable might be more likely to try and quit.44

The temporal pattern of changes found in this study is consistent with other early evaluations of the impact of the new plain packs. The proportion of smokers reporting negative responses to their packs and the warnings on them increased throughout the phase-in period, corresponding to the increasing proportion of plain packs observed in public venues during that period,45 and the number of smokers reporting to be smoking from plain packs.2 The earliest effects of the new packs have been detected during this phase-in period, with declines in rates of active smoking observed in outdoor dining venues in October-November,45 and calls to a cessation helpline peaking in November.19 From the current time-series analysis, smokers’ tendency to avoid the on-pack health warnings increased significantly in December, 2 months after the plain packs started appearing, when plain packs became mandatory for sale. This coincides with an observed decline in rates of pack display and an increase in concealment of packs in outdoor venues.45 Other changes observed in this study (cognitive and emotional responses to GHWs, and negative pack perceptions) reached significance in January, at a time when less than 5% of packs observed in outdoor venues were fully branded.45 These changes occurred just after an increase in the number of smokers rating their cigarettes as being lower in quality and less satisfying than 1 year ago.2 All changes in pack-related responses observed in this study were maintained at 8 months after the first appearance of the new packs, the last data point in the current series.

The strengths of this study include the use of population-level data collected over a long time period, resulting in a large sample of adult smokers. As recommended in a recent review of the plain packaging literature,5 the use of a time-series approach with multiple data points before the intervention increased the power to detect any effects over and above the long-term background and seasonal trends, and the inclusion of important time-related potential covariates decreased threats to the validity of the findings. The regression analyses allowed us to control for any changes in sample composition in regard to demographic characteristics such as SES and smoking levels. We note that the sample for this study consisted of current smokers only, and therefore any smokers who quit in the postplain packaging period would be excluded. This might have resulted in a sample of smokers somewhat resistant to this intervention, and as such the estimates provided in this study might be more conservative than if we had also surveyed smokers who quit during this time.

Limitations of the study include the use of landline-only telephone numbers and a somewhat low response rate, possibly leading to some bias in sample composition. The rate of mobile-only households in Australia, recently estimated at 19%, increased over the years of this study.46 Recent dual-frame surveys have shown that samples recruited via mobile phone are more likely to include younger respondents and males than landline samples.47 The impact of these demographic differences are likely to be reduced in this study due to the inclusion of age and gender as covariates, the use of data weighted for these variables where appropriate, and the inclusion of smoking-related covariates related to these demographic characteristics. The response rate of CITTS is similar to that of other population telephone surveys on tobacco use in Australia,48 and was consistent across the study period, limiting its influence on the observed pattern of results.

In an environment of strict tobacco promotion prohibition such as Australia, cigarette packaging had become the key tool used by the tobacco industry to attract and retain customers.49 50 The purpose of the plain packaging legislation was to deprive tobacco companies of an ongoing opportunity to promote their products in the community. The introductory effects of the plain packaging legislation observed in this study are consistent with the specific objectives of the legislation in regard to increasing the salience and impact of health warnings, and reducing the promotional appeal of tobacco packaging. Owing to the fact that tobacco packs are handled every time a smoker takes out a cigarette, those who smoke more than a pack per day were potentially exposed to their new packs almost 4000 times in the first 6 months of the legislated changes. The findings of this study suggest that the new packs are decreasing smokers’ identification with their packs and making them think more closely about the health warnings contained on them, potentially moving them closer to cessation. Future research should extend this study by considering any relationships between smokers’ responses to their plain packaging packs and changes in smoking behaviours, investigating whether the introductory effects identified in this study were apparent in youth smokers, and monitoring the impact of plain packaging on perceptions about smoking among non-smoking youth and adults.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: SMD, DP and JMY conceived the study. DP and SMD acquired the data. SMD searched the literature and extracted the data. TD and SMD performed the analyses. SMD drafted the manuscript. TD, JMY, DP and DCC contributed to the initial revision of the manuscript. SMD, TD, JMY, DP and DCC contributed to the critical revision of the manuscript before publication. SMD is the guarantor. All authors interpreted the data. All authors had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Funding: This study was internally funded by the Cancer Institute NSW.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: The CITTS has ethics approval from the NSW Population Health Services Research Ethics Committee (HREC/10/CIPHS/13). All respondents gave informed consent before taking part in the study.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Tobacco Plain Packaging Act 2011 (No. 148, 2011), Australian Commonwealth Government, 2011.

- 2.Wakefield M, Hayes L, Durkin S et al. Introduction effects of the Australian plain packaging policy on adult smokers: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2013;3:e003175 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stead M, Moodie C, Angus K et al. Is consumer response to plain/standardised tobacco packaging consistent with framework convention on tobacco control guidelines? A systematic review of quantitative studies. PLoS One 2013;8:e75919 10.1371/journal.pone.0075919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Quit Victoria CCV. Plain packaging of tobacco products: a review of the evidence. Melbourne: Cancer Council Australia; 2011. http://www.cancervic.org.au/plainfacts/browse.asp?ContainerID=plainfacts-evidence [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moodie C, Stead M, Bauld L et al. Plain Tobacco Packaging: A Systematic Review. http://phrc.lshtm.ac.uk/papers/PHRC_006_Final_Report.pdf (accessed 10 Apr 2014). University of Stirling, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Hammond D. “Plain packaging” regulations for tobacco products: the impact of standardizing the color and design of cigarette packs. Salud Publica Mex 2010;52(Suppl 2):S226–32. 10.1590/S0036-36342010000800018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wakefield M, Germain D, Durkin S. How does increasingly plainer cigarette packaging influence adult smokers’ perceptions about brand image? An experimental study. Tob Control 2008;17:416–21. 10.1136/tc.2008.026732 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wakefield M, Germain D, Durkin S et al. Do larger pictorial health warnings diminish the need for plain packaging of cigarettes? Addiction 2012;107:1159–67. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2012.03774.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Germain D, Wakefield MA, Durkin SJ. Adolescents’ perceptions of cigarette brand image: does plain packaging make a difference? J Adolesc Health 2010;46:385–92. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.08.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hammond D, Daniel S, White CM. The effect of cigarette branding and plain packaging on female youth in the United Kingdom. J Adolesc Health 2013;52:151–7. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gallopel-Morvan K, Moodie C, Hammond D et al. Consumer perceptions of cigarette pack design in France: a comparison of regular, limited edition and plain packaging. Tob Control 2012;21:502–6. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moodie C, Ford A, Mackintosh AM et al. Young people's perceptions of cigarette packaging and plain packaging: an online survey. Nicotine Tob Res 2012;14:98–105. 10.1093/ntr/ntr136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Scheffels J, Lund I. The impact of cigarette branding and plain packaging on perceptions of product appeal and risk among young adults in Norway: a between-subjects experimental survey. BMJ Open 2013;3:e003732 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003732 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McCool J, Webb L, Cameron LD et al. Graphic warning labels on plain cigarette packs: Will they make a difference to adolescents? Soc Sci Med 2012;74:1269–73. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.12.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goldberg ME, Liefeld J, Madill J et al. The effect of plain packaging on response to health warnings. Am J Public Health 1999;89:1434–5. 10.2105/AJPH.89.9.1434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Freeman B, Chapman S, Rimmer M. The case of plain packaging of tobacco products. Addiction 2008;103:580–90. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02145.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moodie C, Mackintosh AM, Hastings G et al. Young adult smokers’ perceptions of plain packaging: a pilot naturalistic study. Tob Control 2011;20:367–73. 10.1136/tc.2011.042911 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moodie CS, Mackintosh AM. Young adult women smokers’ response to using plain cigarette packaging: a naturalistic approach. BMJ Open 2013;3:pii: e002402 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-002402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Young J, Stacey I, Dobbins T et al. The association between tobacco plain packaging and Quitline calls: a population-based, interrupted time series analysis. Med J Aust 2014;200:29–32. 10.5694/mja13.11070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.American Association for Public Opinion Research. Standard definitions: final dispositions of case codes and outcome rates for surveys. Lenexa, Kansas: AAPOR, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wakefield MA, Bowe SJ, Durkin SJ et al. Does tobacco-control mass media campaign exposure prevent relapse among recent quitters? Nicotine Tob Res 2013;15:385–92. 10.1093/ntr/nts134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wakefield M, Spittal MJ, Yong HH et al. Effects of mass media campaign exposure intensity and durability on quit attempts in a population-based cohort study. Health Educ Res 2011;26:988–97. 10.1093/her/cyr054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dunlop S, Perez D, Cotter T et al. Televised antismoking advertising: effects of level and duration of exposure. Am J Public Health 2013;103:e66–73. 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.OzTAM. Weekly TARP data for all television markets in NSW, Australia, 2005–2013. Prepared for The Cancer Institute NSW. North Sydney, Australia: OzTAM Pty Ltd, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wakefield M, Durkin S, Spittal M et al. Impact of tobacco control policies and mass media campaigns on monthly adult smoking prevalence. Am J Public Health 2008;98:1443–50. 10.2105/AJPH.2007.128991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Australian Bureau of Statistics. Average Weekly Earnings. Canberra, Australia: Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 27.SAS Institute Inc. SAS version 9.3. Cary, NC, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Box GEP, Jenkins GM, Reinsel GC. Time series analysis: forecasting and control. 4th edn Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cohen J, Cohen P, West S et al. Applied Multiple Regression/Correlation Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. 3rd edn Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum, 2003:64–99. [Google Scholar]

- 30.StataCorp. Stata v11.1 Texas, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Australian Bureau of Statistics. Population by age and sex, Australian states and territories, June 2006. Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2007. Contract No.: cat no. 3201.0. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miller CL, Hill DJ, Quester PG et al. Response of mass media, tobacco industry and smokers to the introduction of graphic cigarette pack warnings in Australia. Eur J Public Health 2009;19:644–9. 10.1093/eurpub/ckp089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hammond D. Health warning messages on tobacco products: a review. Tob Control 2011;20:327–37. 10.1136/tc.2010.037630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Borland R, Yong HH, Wilson N et al. How reactions to cigarette packet health warnings influence quitting: findings from the ITC Four-Country survey. Addiction 2009;104:669–75. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02508.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Partos TR, Borland R, Yong HH et al. Cigarette packet warning labels can prevent relapse: findings from the International Tobacco Control 4-Country policy evaluation cohort study. Tob Control 2013;22:e43–50. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yong HH, Borland R, Thrasher JF et al. Mediational pathways of the impact of cigarette warning labels on quit attempts. Health Psychol 2014;33:1410–20. 10.1037/hea0000056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Borland R, Wilson N, Fong GT et al. Impact of graphic and text warnings on cigarette packs: findings from four countries over five years. Tob Control 2009;18:358–64. 10.1136/tc.2008.028043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Maynard OM, Munafo MR, Leonards U. Visual attention to health warnings on plain tobacco packaging in adolescent smokers and non-smokers. Addiction 2013;108:413–19. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2012.04028.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Munafo MR, Roberts N, Bauld L et al. Plain packaging increases visual attention to health warnings on cigarette packs in non-smokers and weekly smokers but not daily smokers. Addiction 2011;106:1505–10. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03430.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Goldberg ME, Kindra G, Lefebvre J et al. When packages can't speak: possible impacts of plain and generic packaging of tobacco products. Expert panel report prepared at the request of Health Canada, 1995. Contract No.: 521716345/6771.

- 41.Wakefield M. Welcome to cardboard country: how plain packaging could change the subjective experience of smoking. Tob Control 2011;20:321–2. 10.1136/tc.2011.044446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dunlevy S, Stark P. Plain packaging leaves bad taste in smokers’ mouths. Herald Sun 30 November 2012.

- 43.Hagan K, Harrison D. Plain packs ‘put off’ smokers. The Age 30, November 2012.

- 44.Hyland A, Borland R, Li Q et al. Individual-level predictors of cessation behaviours among participants in the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Four Country Survey. Tob Control 2006;15(Suppl 3):iii83–94. 10.1136/tc.2003.007237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zacher M, Bayly M, Brennan E et al. Personal tobacco pack display before and after the introduction of plain packaging with larger pictorial health warnings in Australia: an observational study of outdoor café strips. Addiction 2014;109:653–62. 10.1111/add.12466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Australian Communications and Media Authority (ACMA). Communications report 2010–11 series: Report 2—Converging communications channels: Preferences and behaviours of Australian communications users ACMA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Barr ML, van Ritten JJ, Steel DG et al. Inclusion of mobile phone numbers into an ongoing population health survey in New South Wales, Australia: design, methods, call outcomes, costs and sample representativeness. BMC Med Res Methodol 2012;12:177 10.1186/1471-2288-12-177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Thompson ME, Fong GT, Hammond D et al. Methods of the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Four Country Survey. Tob Control 2006;15(Suppl 3):iii12–18. 10.1136/tc.2005.013870 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wakefield M, Morley C, Horan JK et al. The cigarette pack as image: new evidence from tobacco industry documents. Tob Control 2002;11(Suppl 1):i73–80. 10.1136/tc.11.suppl_1.i73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Carter SM. The Australian cigarette brand as product, person, and symbol. Tob Control 2003;12(Suppl 3):iii79–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.