Abstract

Introduction: More than one-third of U.S. adults are obese, which greatly increases their risks for type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and some types of cancer. Busy healthcare professionals need effective tools and strategies to facilitate healthy eating and increase physical activity, thus promoting weight loss in their patients. Communication technologies such as the Internet and mobile devices offer potentially powerful methodologies to deliver behavioral weight loss interventions, and researchers have studied a variety of technology-assisted approaches. Materials and Methods: The literature from 2002 to 2012 was systematically reviewed by examining clinical trials of technology-assisted interventions for weight loss or weight maintenance among overweight and obese adults. Results: In total, 2,011 citations from electronic databases were identified; 39 articles were eligible for inclusion. Findings suggest that the use of technology-assisted behavioral interventions, particularly those that incorporate text messaging or e-mail, may be effective for producing weight loss among overweight and obese adults. Conclusions: Only a small percentage of the 39 studies reviewed used mobile platforms such as Android® (Google, Mountain View, CA) phones or the iPhone® (Apple, Cupertino, CA), only two studies incorporated cost analysis, none was able to identify which features were most responsible for changes in outcomes, and few reported long-term outcomes. All of these areas are important foci for future research.

Key words: : randomized trial, weight loss, technology

Introduction

More than one-third of U.S. adults (35.7%) are obese,1 which greatly increases their risks for hypertension, hyperlipidemia, type 2 diabetes, heart disease, stroke, and some types of cancer. Even modest weight loss of 5–10% of initial body weight can reduce the risk of these negative health consequences.2 Although research has demonstrated the efficacy of behavioral interventions on weight loss, promotion and maintenance of such changes continue to be challenges.3–5 The established interventions are resource intensive and require frequent group or individual in-person counseling sessions, which can create barriers for full participation and ultimate translation. Busy health professionals need effective tools and strategies to facilitate healthy eating and increase physical activity in their patients, especially those who are overweight or obese.

Communication technologies such as the Internet and mobile devices offer a potentially powerful approach for addressing common barriers to health behavior change through the delivery of convenient, individually tailored, and contextually meaningful behavioral interventions. Several systematic reviews of technology interventions for weight loss and maintenance have evaluated this research.6–8

The 2011 scientific statement from the American Heart Association concluded that the Internet holds promise as a tool to promote weight loss; however, the data did not support the use of Internet interventions for weight maintenance.6 In addition, the authors stated that it was premature to draw definitive conclusions about the effectiveness of mobile phones.

Bacigalupo et al.8 concluded that there was consistent strong evidence from high-quality clinical trials that mobile technology interventions produce short-term weight loss and moderate evidence for their utility in longer-term weight loss. Coons et al.7 stated that technology-enhanced interventions may be effective in producing weight loss regardless of the technology platform. However, it is important to mention that only half of the reviewed trials reported statistically significant weight loss among those randomized to the technology interventions compared with controls. It was noted across these systematic reviews that many of the trials reported high attrition rates (20–80%), that they limited their analyses to those who completed the trial rather than the more rigorous intention-to-treat analysis, and that the majority of participants were white women.

We provide an updated review of the multiple types of technology-assisted interventions for weight loss and weight maintenance among obese adults focusing on the literature from 2002 through 2012 and completed in June 2013. We provide a summary of the trials, descriptions of the results and trends based on the type of technology-assisted intervention, evaluation of the risk of bias of the trials, and recommendations for future research. Although prior systematic reviews have addressed the effectiveness of technology-based weight loss interventions, this systematic review focuses only on randomized controlled trials, incorporates an evaluation of the quality of the evidence, and takes a comprehensive approach across a wide range of technology-based weight loss and weight maintenance interventions, thereby making a unique contribution to the current weight management literature. To examine whether the use of technology-assisted interventions can improve weight management, we reviewed randomized controlled trials that assessed the efficacy of the use of technology as compared with traditional strategies for weight loss and weight maintenance in overweight and obese adults.

Materials and Methods

Search Strategy and Study Selection

An agreed upon but unpublished protocol of the methods for this review was developed prior to the initiation of the study. We searched electronic databases (PubMed, CINAHL, Embase, and Cochrane) from 2002 to 2012 for English-language publications that report the results of randomized trials using technology to promote weight loss or maintenance in obese or overweight adults. We used the following text word and medical subject heading terms: “telecommunications” OR “Telephone” OR “ iPhone” OR “iPad” OR “smartphone” OR “smart phone” OR “Electronic Mail” OR “email” OR “e mail” OR “e-mail” OR “Internet” OR “world wide web” OR “social media” OR “personal electronic device” OR “PED” OR “PDA” OR “personal digital assistant” AND “obesity” OR “overweight” OR “weight gain” OR “weight loss” OR “body mass index” OR “waist-hip ratio” OR “over weight” OR “fat overload syndrome” OR “obes” OR “body mass ind” OR “waist-hip ratio” OR “skinfold thickness” AND “adult” AND “clinical trials” OR “clinical trial” OR “random” OR “random allocation” OR “randomized controlled trial” OR “randomized” OR “randomized trial.” The final search was completed on June 13, 2013.

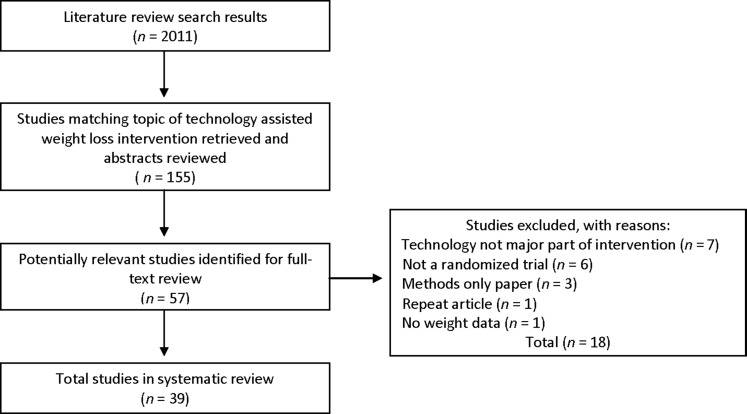

All retrieved titles and abstracts were screened by the three authors to determine eligibility. We excluded studies if they were not randomized trials, did not report weight as a primary outcome, did not use electronic technology as a major component of the intervention, were systematic reviews or reports of study methods only, or were self-described pilot studies. The three authors performed the initial abstract reviews. After exclusion of duplicate articles, 57 full-text articles were collected. Candidate articles were evaluated for inclusion by author dyads. A third author independent reviewer resolved any discrepancies between the dyads. Figure 1 provides a detailed description of our search results.

Fig. 1.

CONSORT diagram of search methods used in this article.

Data Abstraction

The three author reviewers abstracted information about each study, including the population studied (sample size, demographics), description of the intervention and control conditions, retention rate, outcome measures, and intervention results.

Risk of Bias Assessment

The risk of bias of each study was independently assessed by two of the authors (J.K.A. and J.S.) using the criteria in the Cochrane risk of bias tool9 (Table 1). Each item was scored according to the following recommended rubric: yes=1; no=0; unclear=0. An acceptable dropout rate was considered ≤20% for short-term follow-up studies (≤6 months) and ≤30% for long-term studies (>6 months). Acceptable compliance was considered ≥80% adherence. A study with at least 6 out of the 12 criteria met is considered a study with a low risk of bias; a study meeting fewer than 6 of the criteria or one with serious flaws (e.g., 80% dropout rate) is considered at high risk of bias.9 There was 95% agreement between the two raters. Any initial disagreement in ratings of the criteria for individual studies was resolved through discussion of the two reviewers. A third reviewer to arbitrate a decision was not needed.

Table 1.

Sources of Risk of Bias

| 1. Was the method of randomization adequate? |

| 2. Was the treatment allocation concealed? |

| 3. Was the patient blinded to the intervention? |

| 4. Was the care provider blinded by the intervention? |

| 5. Was the outcome assessor blinded to the intervention? |

| 6. Was the dropout rate described and acceptable? |

| 7. Were all randomized participants analyzed in the group to which they were allocated? |

| 8. Are reports of the study free of suggestion of selective outcome reporting? |

| 9. Were the groups similar at baseline regarding the most important prognostic indicators? |

| 10. Were co-interventions avoided or similar? |

| 11. Was the compliance acceptable in all groups? |

| 12. Was the timing of the outcome assessment similar in all groups? |

Adapted from Furlan et al.9

Results

Study Selection

In total, 2,011 citations from electronic databases were identified. After initial screening of 155 abstracts, we reviewed 57 full-text articles and excluded 18 of these studies. Table 2 presents a summary from the 39 unique randomized trials that were eligible for this systematic review.

Table 2.

Summary of Weight Management Clinical Trials

| STUDY (YEAR): DESCRIPTION | SAMPLE | INTERVENTION/CONTROL | OUTCOME MEASURES | ANALYSIS/RESULTS | RISK OF BIAS SCORE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Web site | |||||

| Brindal et al.12 (2012): 12-week study comparing three Web-based functional groups on retention and weight loss | n=2,648→435; 83.4% female; mean age, 45 years, mean BMI, 34.0 kg/m2 | All groups used a Web site with varying features depending on three functional groups: (1) information-based (static, noninteractive version of weight loss program); (2) supportive (social, interactive Web site; social networking, dietary information); (3) personalized supportive (same as supportive but with a personalized meal planner) | Primary outcomes: retention and weight loss | Retention: 40% loss after Week 1, 20% per week lost Weeks 2–12; 5.2% of users had activity in Week 12. Weight loss: n=435; lost 4.1% of initial body weight, 37.6% lost over 5% of their body weight. Information-based: lost 4.15% (±4.26%) Supportive: lost 4.22% (±4.34%) Personalized supportive: lost 3.97% (±3.73%) |

7 |

| Cussler et al.13 (2008): a 12-month Internet or self-directed intervention to compare weight regain in perimenopausal women following weight loss treatment | n=135; 100% female; average age, 48.2 years; mean BMI, 30.7 kg/m2 | Internet group: use of Web site for information, completion of logs (weight, diet, exercise) Self-directed group: no contact with staff |

Primary outcome: weight regain at 12 months | Weight regain: Internet, 0.4±5.0 kg; self-directed, 0.6±4.0 kg (p=0.5) | 6 |

| Lachausse14 (2012): 12-week weight loss study comparing three conditions, My Student Body program, an on-campus weight management course, and a control condition |

n=358±312 My Student Body: 78.3% female; 53.8% Hispanic; mean age, 26.6 years; 9.2% enrolled in PE course; n=106 On-campus course: 75.7% female; 38.6% Hispanic; mean age, 25.0 years; 10.8% enrolled in PE course; n=70 Control: 73.5% female; 39.0% Hispanic; mean age, 22.8 years; 6.9% enrolled in PE course; n=136 |

My Student Body (online): Internet-based program, provides nutrition and physical activity education, three information links, four rate myself links, and four main learning modules On-campus: The course met one time per week for 2 h for the entire 12 weeks and taught weight management, time management, eating behaviors, etc. Control: no intervention |

Primary outcome: BMI Secondary outcomes: fruit and vegetable consumption, aerobic exercise, exercise self- efficacy, attitudes toward exercise, stress, fruit and vegetable self-efficacy |

BMI: no change in BMI among the three groups Fruit and vegetable consumption: mean increased for the online group but not the other two groups from pre-test to post-test. Aerobic exercise: no change in frequency among the three groups Exercise self-efficacy: no changes in the three groups Stress: Perceived stress scale scores decreased in the online group but did not change in the other two groups. Attitudes toward exercise: no changes in the three groups Fruit and vegetable self-efficacy: scores increased in the online group, but no change in the other two groups. |

4 |

| Touger-Decker et al.15 (2010): 12-week workplace intervention for weight loss comparing an in-person versus online version | n=137±113; 93.4% female; 54% nonwhite; mean age, 46.5 years; 66.4% obese | All subjects: 90-min meeting with RD for baseline In-person: weighed weekly after education sessions Online: weekly education sessions over the Internet, asynchronous discussion board available |

Primary outcome: change in body weight Secondary outcomes: waist circumference, blood pressure, physical activity, nutrient intake, quality of life |

Weight loss: Weight loss within subjects was significant over time. Waist circumference: significant decrease in all subjects over 12 weeks Blood pressure: significant decrease in SBP in both groups Diet: significant reduction in calorie intake over time for all subjects Quality of life: significant decrease in number of physically and mentally unhealthy days in both groups Physical activity: increased in both groups |

5 |

| Web site plus e-mail, phone, or texting | |||||

| Appel et al.16 (2011): 24-month remote and in person behavioral weight loss intervention |

n=415→392; 63.6% women; 41.0% African American; mean age, 54 years Control: 63.8% women; 42.8% African American; mean age, 52.9 years Remote support: 63.3% women; 37.4% African American; mean age, 55.8 years In-person support: 63.8% women; 42.8% African American; mean age, 53.3 years |

Intervention: Remote support: weekly contact for first 3 months, monthly contact for remaining durations. Participants provided with support remotely through e-mail, telephone, and Web site support. In-person support: weekly sessions first 3 months, three contacts per month for next 3 months, two monthly contacts for remaining duration. Participants had group and individual sessions plus the e-mail, telephone, and Web site support. Control: met with a weight-loss coach at the time of randomization and, if desired, at 24 months. Received brochures and a list of recommended Web sites promoting weight loss |

Primary outcome: change in weight at 24 months Secondary outcomes: percentage of weight change from baseline, percentage of participants without weight gain, percentage of participants who lost at least 5% of their initial weight |

Change in weight at 24 months: remote support, −4.6 ± 0.7 kg (p<0.001); in-person support, −5.1±0.8 kg (p<0.001); control, −5.1±0.8 kg Percentage weight change: remote support, −5.0%; in-person support, −5.2%; control, −1.1% Percentage with no weight gain: remote support, 77.1% (p<0.001); in-person support, 74.4% (p<0.001); control, 52.3% Percentage with 5% weight loss: remote support, 38.2% (p<0.001); in-person support, 41.4% (p<0.001); control, 18.8% |

7 |

| Bennett et al.17 (2010): 12-week Web-based intervention for obese patients with hypertension |

n=101±85; 47.5% female; 30.7% African American; mean age, 54.4 years Intervention: n=51±43; 41.2% female; 37.3% African American; mean age, 54.4 years Control: n=50±42; 54% female; 24% African American; mean age, 54.5 years |

Both groups received “Aims for Healthy Weight” materials from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute. Intervention: four counseling sessions (two in-person and two telephone) and use of a comprehensive tailored Web site with behavior change goals for weight loss Control: UC, providers approached weight loss as they saw fit |

Primary outcome: weight loss at 12 weeks Secondary outcomes: change in BMI, blood pressure control (<140/90 mm Hg), and waist circumference | Weight loss: intervention, −2.71 kg; control, 0.34 kg; difference between condition (95% CI), −3.05 (−4.24, −1.85) Change in BMI: intervention, −0.94±1.16 kg/m2; control, 0.13±0.75 kg/m2; mean difference (95% CI), −1.07 kg/m2 (−1.49, −0.64) No group differences for waist circumference or blood pressure |

8 |

| Chambliss et al.18 (2011): 12-week weight management intervention using computer self-monitoring and feedback with and without an enhanced behavioral component | n=120±95; 83% female; 73% white; mean age, 45.0 years | Basic group: 1-h weight management seminar, daily self-monitoring (BalanceLog software), calorie goals, weekly structured e-mail feedback, monthly measurement visits Enhanced group: calorie goals, 2-h seminar on weight management and behavior change, daily self- monitoring (BalanceLog software), weekly behavior tracking forms, step counters, monthly newsletters, monthly telephone consultations, weekly structured e-mail feedback, monthly measurement visits Wait-list control: basic intervention after 12 weeks, monthly measurement visits |

Primary outcome: weight change Secondary outcomes: waist circumference, SBP |

Weight change: basic, −2.7±3.3 kg; enhanced, −2.5±3.1 kg; control, +0.3±2.2 kg (no significant difference between the two treatment groups, p=0.61) Waist circumference: basic, −3.4±4.6 cm; enhanced, −2.8±5.4 cm; control, −0.6±5.2 cm (basic group was statistically different from control, p=0.04) SBP, basic, −5.9±8.6 mm Hg; enhanced, −6.0±8.2 mm Hg; control, −2.5±8.2 mm Hg (the two treatment groups had a significant decrease from baseline, p<0.001) |

6 |

| Collins et al.19 (2012): 12-week weight loss program comparing a basic Web-based program with an enhanced Web-based program | n=309±260; 41.8% male; 90.6% Australian born; mean BMI, 32.3 kg/m2 | Basic: use of a Web-based weight loss program that was commercially available, including food and exercise diary, menu plans, community forums, newsletters, etc. Enhanced: Same features as basic plus personalized electronic feedback, reminder schedule, and automated personalized goals Control: wait-list control group with no access to weight loss program |

Primary outcome: change in BMI, weight Secondary outcomes: change in waist circumference, lipids, glucose, insulin, blood pressure, dietary intake, and physical activity |

BMI: basic, −0.72 kg/m2 (1.07); enhanced, −0.98 kg/m2 (1.38); control, 0.15 kg/m2 (0.82); enhanced and basic versus control, p<0.001 Weight: basic, −2.14 kg (3.32); enhanced, −2.98 kg (4.05); control, 0.36 kg (2.33); enhanced and basic versus control, p<0.001 Waist circumference: basic, −2.63 cm (3.99); enhanced, −3.18 cm (5.00); control, 0.26 cm (3.10); enhanced and basic versus control, p<0.001 Lipids: significant improvement in total cholesterol when comparing enhanced with control; no other significant changes in lipids. Blood pressure: significant change in systolic BP comparing enhanced with control (95% CI, 1.31, 7.17) Dietary intake: Enhanced group decreased intake more than control (p=0.03). Physical activity: no significant changes in METs; significant increase in step count comparing enhanced with control (p=0.005) |

9 |

| Gold et al.20 (2007): 12-month weight loss and weight maintenance study comparing a commercial self-help Web site (eDiets) with an online behavioral intervention (VTrim) |

n=185±88 VTrim: 77% female; 98% white; mean age, 46.5 years; n=62±40 eDiets: 86% female; 98% white; mean age, 48.9 years; n=62±48 |

VTrim: 6-month online therapist led weight loss program with weekly lessons, meetings, and feedback and tracking of dietary intake and weight; 6-month maintenance phase included same features but less frequent (biweekly meetings) eDiets: access to the eDiets.com Web site where participants self-guided and used the Web site; provided a meal plan, calorie plan, and recipes and encouraged exercise |

Primary outcome: body weight change Secondary outcomes: dietary intake, exercise, use of Web site features, eating behaviors, social influence components |

Change in weight: VTrim lost more weight than eDiets in the first 6 months (6.8±7.8 kg versus 3.3±5.8 kg, p=0.005). At 12 months, VTrim had maintained significantly higher weight loss than eDiets (5.1±7.1 kg versus 2.6±5.3 kg, p=0.034). Diet and exercise: Both groups changed over time, decreased calories by 457 kcal/day for both groups, and increased exercise by 372 kcal/day from 0 to 6 months. Usage of Web site: Significantly more log-ins (0–6 months) for VTrim versus eDiets (p<0.001), more self-reported weight for VTrim versus eDiets (p=0.002) Eating behavior: Mean change in score was significantly higher for VTrim than eDiets (5.5±4.0 versus 3.2±3.8; p=0.005), indicating more behaviors conducive to weight control for VTrim. Social influence: perceived social support higher in VTrim versus eDiets (6.7±3.2 versus 3.5±2.9; p<0.001) |

5 |

| Gabriele et al.21 (2011): 12-week weight loss program comparing directive and nondirective electronic coaching |

n=104→96 Nondirective: 80% female; 77.1% white; mean age, 42.91 years Directive: 85.70% female; 60% white; mean age, 46.57 years Minimal: 85.3% female; 76.47% white; mean age, 46.76 years |

Nondirective: weekly lesson e-mails, coach supported, individual to set goals, and weekly feedback Directive: weekly lesson e-mails, coach-set goals for participant, topics of discussion selected by coach, provided concrete, specific advice Minimal support: weekly lesson e-mail, no other support |

Primary outcome: weight change | Weight change: Minimal: females, −2.44 kg (3.04); males, −6.67 kg (5.32) Directive: females, −4.50 kg (3.73); males, −3.35 kg (5.88) Nondirective, females, −2.50 kg (3.36); males, −6.57 kg (6.63) Significance: minimal versus directive for females, p=0.01; nondirective versus directive for females, p=0.00 |

7 |

| Hersey et al.10 (2012): 15–18-month weight management program comparing three interventions with increasing intensity | n=1,755±509; 74% female; 83.6% non-Hispanic white; mean age, 47.6 years; mean baseline BMI, 33.6 kg/m2 | All participants were given weight loss medications during year 1 (4% reported use). RCT1: bookHEALTH manual and eHEALTH tools (basic Internet component) RCT2: same as RCT1 with interactive version of eHEALTH that provided tailored feedback RCT3: same as RCT2 with added telephonic coaching support every 2 weeks and personalized e-mail |

Primary outcome: change in weight Secondary outcomes: change in blood pressure and physical activity | Weight: Participants in all groups lost a mean of 4.6% at 6 months, 4.6% at 12 months, and 3.7% at 15–18 months (no differences between groups). Blood pressure: In all groups, mean SBP decreased (129.8 mm Hg to 124.3 mm Hg at 12 months; p<0.01). Exercise: The proportion of all participants engaging in regular physical activity increased 29.1% to 40.2% at 12 months and to 44.2% at 15–18 months. |

6 |

| Hunter et al.22 (2008): 6-month weight loss and weight gain prevention study comparing an Internet treatment with UC | n=451→446; U.S. Air force males and females; 50% female; mean age, 34 years; mean BMI, 29.0 kg/m2 | UC: one visit annually with primary care provider; access to workout facilities, cooking classes, nutrition consultations, expectation of three workouts per week (U.S. Air Force requirement) BIT: UC plus electronic food and exercise records, weekly counselor feedback, weight loss and calorie goals, weekly lessons, Web site information, two motivational interviewing calls |

Primary outcome: weight at 6 months Secondary outcomes: BMI, waist circumference, body fat percentage, 5% or more weight loss, diet intake, and physical activity |

Weight: BIT versus UC, −1.3±4.1 kg versus 0.6±3.4 kg (p<0.001) BMI: BIT versus UC, −0.5 versus +0.5 kg/m2 (p<0.001) Waist circumference: BIT versus UC, −2.1 versus −0.4 cm (p<0.001) Body fat percentage: BIT versus UC, −0.4% versus +0.6% (p<0.001) 5% weight loss: BIT versus UC, 22.6% versus 6.8% (p<0.001). Diet: significant group×time interaction for fruit and vegetable intake (p=0.002) and meat and snack intake (p=0.045) Physical activity: no difference between groups |

6 |

| Kraschnewski et al.23 (2011): 12-week weight loss study comparing a Web-based intervention with control | n=100±88; 69.7% female; 90.8% white; mean age, 50.3 years; mean BMI, 33.2 kg/m2 | Web site (ActiveTogether) guided to implement 36 weight control behaviors, entered weight weekly, Web site access, videos of role models, tailored feedback at log-in, e-mail reminders; n=50±43 Control: wait-list control; n=50±45 |

Primary outcome: change in weight Secondary outcomes: blood pressure, caloric intake, quality of life, use of weight control practices |

Weight: Web site versus control, 1.4 kg versus 0.6 kg (p<0.01) Blood pressure: Web site versus control SBP, −7.1 mm Hg versus −3.6 mm Hg (not significant); diastolic, −1.5 mm Hg versus 2.2 mm Hg (p<0.05) Quality of life: Web site versus control, 2.6 versus 0.6 (not significant) Weight control: Web site versus control, 0.4 versus 0.0 (p<0.05) Diet intake: Web site versus control, −174.9 kcal versus −139.8 kcal (not significant) |

8 |

| McConnon et al.24 (2007): 12-month study comparing a group receiving an Internet program for obesity management and a UC group |

n=221±131; 77% female; 95% white; mean age, 45.8 years; mean BMI, 34.4 kg/m2 Internet group: n=111±54 UC group: n= 110±77 |

Internet group: provided with access to a Web site with tool, advice, and information to support behavior change in terms of diet and physical activity patterns; individualized motivational feedback to participants and reminder e-mails for not visiting the Web site UC group: advised to follow same plan and given brief information |

Primary outcome: change in weight Secondary outcomes: physical activity level, lifestyle and dietary habits, quality of life |

Weight loss: The UC group lost 1.9 kg versus 1.3 kg in the Internet group (p=0.56) at 12 months. No significant changes in secondary outcomes between the two groups at 6 or 12 months. |

5 |

| Micco et al.25 (2007): 12-month RCT to compare weight loss outcomes on an Internet-only weight loss program with the same program supplemented by monthly in-person visits |

n=123→77 Internet only: n=62→39; 23% male; mean age, 46.5 years; mean BMI, 32.3 kg/m2 Internet+in-person: n=61→38; 12% male; mean age, 47.1 years; mean BMI, 31.0 kg/m2 |

Internet: Participants were divided into groups and met weekly on an online chat room, provided lessons that focused on behavior modification, prescribed a maximum caloric intake, encouraged to exercise 5–7 days/week, had weekly homework and also submitted weekly electronic food journals, and got positive reinforcement. Internet+in-person treatment: Participants were given the same intervention as above with the addition of an in-person meeting that took the place of a monthly online chat session. |

Primary outcome: weight loss at 6 and 12 months | There were no significant differences in weight loss between completers at 6 and 12 months. 6-month weight loss: Internet only, −9.2±7.0 kg; Internet+in-person, −6.9±4.2 kg (p=0.08) 12-month weight loss: Internet only, −8.1±7.5 kg; Internet+in-person, -–5.6±5.5 kg (p=0.10) |

9 |

| Morgan et al.26 (2011): 12-month weight loss study comparing a comprehensive Internet program (SHED-IT) with an information-only control group |

n=65 Internet: mean age, 37.5 years; mean weight, 99.1 kg Control group: mean age, 34.0 years; mean weight, 99.2 kg |

Internet group: a 75-min information and Web site training session, information booklet, access to a comprehensive Web site, and 3 months of online support Information only: received a 60-min information session identical to the Internet group and received a weight loss booklet |

Primary outcome: change in body weight and BMI Secondary outcomes: blood pressure, waist circumference |

Change in weight: Both groups maintained significant weight loss at 12 months (p<0.001). No difference between groups (p=0.408) BMI: significant decrease in BMI in both groups (p<0.001). No difference between groups. Blood pressure and waist circumference: reduction in both groups at 12 months (p<0.001). Significant difference in SBP between Internet (−11 mm Hg) and control (−6 mm Hg) (p=0.03) |

9 |

| Morgan et al.27 (2011): 3-month weight loss program to determine the effectiveness of a workplace program versus a control condition | n=110±86; 100% male; mean age, 44.4 years; mean BMI, 30.5 kg/m2 | Workplace program: study Web site, information session, handbook, Web site tutorial and user guide, seven individualized dietary feedback sheets, group-based financial incentives, pedometer Control: 14-week wait-listed |

Primary outcome: weight at 14 weeks Secondary outcomes: waist circumference, blood pressure, resting heart rate, physical activity, dietary habits |

Weight loss: mean difference of 4.3 kg between groups (p<0.001). Significantly more participants in the workplace group lost 5% or greater of body weight (p<0.001). Significant treatment effects found for BMI, resting heart rate, waist circumference, SBP, and physical activity |

6 |

| Mouttapa et al.28 (2011): 5-week weight loss intervention comparing a PNP with a control group | n=307→261; 100% female; 100% university staff; 59.1% white | Internet (PNP): Web site with nutrition information, goal-setting features, body assessments, individualized feedback Control: received no program |

Primary outcome: weight loss Secondary outcomes: dietary intake frequencies, opinions on program |

Weight loss: no significant intervention effect between pre-test and post-test. Intervention lost on average 1.3 lbs, whereas control lost 0.63 lbs. Dietary intake: no significant findings for vegetable and fruit intake. Significant increase in dairy intake for the PNP group compared with control (F=4.50, p<0.05) Opinions on program: Follow-up e-mails from the program averaged a score of 3.68/5. Program materials influencing weight loss behaviors scored a 3.04/5. |

5 |

| Paineau et al.29 (2008): 8-month family-based intervention to improve diet quality and reduce weight, comparison of three groups |

n=1,013 families→859 families Group A: 48.1% male children; 18.5% male adults; mean age of children, 7.7 years; mean age of adults, 40.4 years Group B: 50% male children; 16.1% male adults; mean age of children, 7.8 years; mean age of adults, 40.3 years Group C: 45.2% male children; 18.9% male adults; mean age of children, 7.6 years; mean age of adults, 40.6 years |

Group A: advised to reduce fat and increase complex carbohydrates, monthly phone counseling and Internet-based monitoring Group B: advised to reduce fat and sugar intake and to increase complex carbohydrate intake, plus monthly phone counseling and Internet-based monitoring Group C: control, no intervention |

Primary outcome: change in nutritional intake and BMI Secondary outcome: change in fat mass, physical activity, blood indicators, and quality of life |

BMI: no significant changes in children. For parents, significant difference between Group B and control (p=0.01) Dietary intake: decrease in energy intake for both Group A and B compared with control (children, p<0.001; adults, p=0.02) No significant differences among groups for anthropometric changes in children (all increased) Fat mass: significant decrease in Group B for adults Blood indicators: no significant differences Physical activity: no significant differences in changes in adults or children between groups |

6 |

| Patrick et al.30 (2011): 12-month weight loss program for men comparing a tailored Web site and modules with a control group | n=441; 100% male; 71% white; mean age, 43.9 years; two-thirds college graduates | Intervention: Web site with weekly modules, goal setting, and individualized feedback; focus on increasing fiber and fruits/vegetables, decreasing saturated fat intake, increasing steps per day and strength training Control: wait-list, given access to a Web site with information for men (hair loss, stress, injury prevention); at 12 months, crossed over to weight loss intervention |

Primary outcome: weight loss Secondary outcomes: waist circumference, percentage energy from saturated fat, grams of fibers, fruit/vegetable intake, walk minutes per day |

Weight loss: no significant differences between groups, but those who participated most in the intervention group had lower weights at 12 months compared with those who participated less. Waist circumference: no significant differences Percentage energy from saturated fat, grams of fiber and fruit/vegetable intake: significant increase (decrease in saturated fat) in intervention compared with control (p<0.001) Minutes walked per day: significant increase (16 min) in intervention compared with control (p<0.05) |

6 |

| Rothert et al.31 (2006): 6-month study comparing the use of a Web site with information only with a tailored behavioral management Web program (TES) |

n=2,862±585 TES: 82.9% female; 35.4% African American; mean age, 45.6 years; mean BMI, 33.3 kg/m2 Information only: 82.7% female; 35.8% African American; mean age, 45.2 years; mean BMI, 31.1 kg/m2 |

TES: individually tailored weight loss plan, opportunity to enroll a “buddy,” tailored action plans delivered at 1, 3, and 6 weeks, follow-up materials Information only: standard Kaiser Permanente Web site for weight loss and weight management |

Primary outcome: % weight loss | Weight loss: those in the tailored Web group lost significant more weight versus information only (–3±0.3% versus −1.2±0.4%; p<0.0004) | 6 |

| van Weir et al.32 (2009): 6-month intervention comparing information plus phone counseling, Web site plus e-mail counseling, and UC on weight loss in a population of overweight working adults | n=1,386→982; 67% male; mean age, 43 years; mean BMI, 29.6 kg/m2; 34% obese; 14.9% smokers | All groups received the same printed weight loss materials. Phone: phone counseling every 2 weeks, program in a binder (10 modules on diet and physical activity), received a pedometer Internet: received program on a Web site, individualized modules, counseling by e-mail, reminders by text messaging UC: materials and no counseling |

Primary outcome: weight loss Secondary outcome: fat, fruit and vegetable intake, physical activity, and waist circumference |

Weight loss: significant weight loss in phone (95% CI, −2.2, −0.8; p<0.001) and Internet (95% CI, −1.3, −0.01; p=0.045) groups compared with control Dietary intake: significant decrease in fat intake (95% CI, −1.7, −0.2; p=0.01) in phone group compared with UC Physical activity: increase by 866 METs minutes/week for phone group compared with control (95% CI, 203, 1,530; p=0.01) Waist circumference: significant decrease in Internet intervention (95% CI, −2.1, −0.4; p=0.01) compared with UC No changes in fruit/vegetable intake |

6 |

| Webber et al.33 (2008): 16-week study comparing a Web site Internet versus an enhanced Web site intervention for overweight and obese women | n=66±65; 100% female; 86% white; average age, 55 years; average BMI, 31.1 kg/m2 | Web site: study Web site and weekly lessons, message boards, self-monitoring, Web links Enhanced Web site: study Web site and weekly lessons, message boards, self-monitoring, Web links, weekly online chat room sessions led to using motivational techniques |

Primary outcome: change in weight and 5% weight loss Secondary outcome: change in lifestyle behaviors (calories consumed and calories burned) |

Weight change: Both groups lost significant weight (p<0.001). No group×time interaction (p=0.19). 67% of the minimal group and 46% of the enhanced group lost at least 5% of their baseline weight. Lifestyle changes: Both groups had a significant decrease in calorie consumption (p<0.01) and fat intake; no differences between groups. Both groups had a significant increase in calories burned per week (p<0.01); no difference between groups. |

5 |

| Tate et al.34 (2003): 12-month RCT comparing the effectiveness of basic Internet with Internet and electronic behavioral counseling on individuals at risk for type 2 diabetes |

n=92→77 Control: n=46→39; 11% male; 89% white; mean age, 47.3 years; mean weight, 89.4 kg; mean BMI, 33.7 kg/m2 Intervention: n=46→38; 9% male; 89% white; mean age, 49.8 years; mean weight, 86.2 kg; mean BMI, 32.5 kg/m2 |

Control: Participants were seen at baseline and 3, 6, and 12 months for measurements. All attended a 1-h introductory Internet instruction and behavioral counseling session. Control: Access to a study Web site that included a tutorial on weight loss, weight loss resources, a message board, and weekly e-mails for weight loss information and reminders to submit weight as Intervention: In addition to the methods above, participants communicated with a behavioral counselor, submitted diaries of caloric intake and exercise; counselors e-mailed feedback, reinforcement, recommendations, and answers to questions. |

Primary outcome: change in weight Secondary outcome: change in waist circumference |

Weight loss: significant difference between control (−2.0±5.7 kg) and intervention (−4.4±6.2 kg) (p=0.04) Waist circumference: significant difference between control (−4.4±5.7 cm) and intervention (−7.2±7.5 cm) (p=0.05) |

7 |

| Tate et al.35 (2006): 6-month RCT comparing effectiveness of HC and computer AF to improve self-directed weight loss |

n=192→155 Control: n=67→59; 18% male; 9% minority; mean age, 49.9 years; mean weight, 88.3 kg; mean BMI, 32.3 kg/m2 Computer AF: n=61→44; 13% male; 10% minority; mean age, 49.7 years; mean weight, 89.0 kg; mean BMI, 32.7 kg/m2 HC: n=64→52; 16% male; 13% minority; mean age, 47.9 years; mean weight, 89.0 kg; mean BMI, 32.8 kg/m2 |

All groups: All participants were recommended a calorie-restricted diet of 1,200–1,500 kcal/day plus the use of liquid weight loss beverages (Slim-Fast), encouraged to increase physical activity to expend 1,050 kcal/week, and instructed on how to use the Slim-Fast Web site. AF and HC: These groups had additional access to an electronic food and exercise monitoring diary and message boards with other participants in the group. The AF group received a preprogrammed computer e-mail based on diary submissions. The HC group received weekly e-mails from a human weight loss counselor whom they had not met in-person. |

Primary outcome: change in body weight | Weight loss at 6 months: control, −2.6±5.7 kg; AF, −4.9±5.9 kg; HC, −7.3±6.2 kg. Weight loss was significantly different between control and HC group (p<0.001). The AF group did not differ significantly from the control (p=0.16) or the HC group (p=0.15). | 7 |

| Text messaging or e-mail | |||||

| Haapala et al.36 (2009): 1-year RCT comparing weight loss using a text message intervention versus with a control group |

n=125 Control: n=63→40; 24% male; mean age, 38.0 years; mean weight, 86.4 kg; mean BMI, 30.4 kg/m2 Intervention: n=62→45; 21% male; mean age, 38.1 years; mean weight, 87.5 kg; mean BMI, 30.6 kg/m2 |

Control: received no intervention but was not discouraged from joining another weight loss program Intervention: received Weight Balance® program, which calculates energy requirements and sends texts indicating weight goals, amount of food to be consumed daily, and days remaining to achieve weight loss goals. It advised dieters to reduce unnecessary foods high in sugar and fat, increase physical activity, and regular weight reporting. |

Primary outcome: change in weight and waist circumference | Change in weight and waist circumference: no significant changes in control group. Significant weight loss in intervention: 4.5±5.0 kg (t=5.8, p<0.0001). Significant reduction in waist circumference in intervention: 6.3±5.3 cm | 6 |

| Patrick et al.37 (2009): 4-month RCT to determine the effectiveness of SMS and MMS on weight loss or weight maintenance versus a control group |

n=78→65 Intervention: n=39→26; 24% male; 18% Hispanic; 21% black; mean age, 47.4 years Control: n=39→26; 16% male; 31% Hispanic, 13% black; mean age, 42.4 years |

Intervention: SMS and MMS about behavioral and dietary strategies sent to participants based on preferences. Users could choose the time and frequency of the messages. Topics, questions, and tips tailored to participants' eating behaviors were sent via messaging. Received nutrition topics and strategies, a food and exercise journal, and 5–15-min monthly phone calls from a health counselor to encourage participation in the program Control: Participants were mailed two pages of printed material on weight loss and nutrition monthly. |

Primary outcome: weight change | Weight change: Intervention lost significantly more weight than control (–1.99 kg compared with control; p=0.04). | 6 |

| Shapiro et al.38 (2012): 12-month RCT to compare the effectiveness of receiving daily interactive text messages with a monthly electronic newsletter |

n=170→143→130 Intervention: n=81→64→57; 33% male; 68% white; mean age, 43.1 years Control: n=81→79→73; 36% male; 62% white; mean age, 40.9 years |

Intervention: received SMS and MMS four times/day, including tips, facts, and questions requiring a reply. Participants were asked to report step count daily (pedometer provided) and weights weekly and received personalized feedback. Received weekly message regarding weight change and a monthly electronic newsletter with diet and physical activity information Control: received the same monthly electronic newsletters |

Primary outcome: weight loss at 6 months | Weight loss: no significant difference in weight loss at 6 months between groups (control, 1.53±7.66 lbs; intervention, 3.72±9.37 lbs) | 8 |

| Thomas et al.39 (2010): Patients who lost ≥5% of initial body weight participated in a 6-month RCT determining the efficacy of e-mail support for weight maintenance. |

n=55→49 Intervention: n=28→26; mean age, 43.2 years; median body weight loss achieved (%) before entry into the study (IQR) (range), 11 (8) (6–20) Control: n=27→23; mean age: 46.2 years; median body weight loss achieved (%) before entry into the study (IQR) (range), 9.5 (7) (5–22) |

Intervention: received a weekly e-mail from a dietician with behavioral and exercise advice. Participants sent an e-mail including current weight monthly to the dietician. Control: no intervention |

Primary outcome: body weight maintained at the end of 6 months | Weight loss initial versus weight loss maintained: 11.2–7.8 kg (p=0.003) for control group and 12.4–10.9 kg (p=0.278) for intervention group, suggesting e-mail was successful in reducing amount of weight regain | 7 |

| Smartphone applications/mobile devices | |||||

| Burke et al.40 (2010): 24-month RCT comparing self-monitoring techniques on weight loss and dietary intake using PDA |

n=210→192 PDA: n=68→64; 14.7% male; 80.9% white; mean age, 46.7 years; mean BMI, 34.9 kg/m2 PDA+feedback, n=70→65; 15.7% male; 78.6% white; mean age, 46.4 years; mean BMI, 34.8 kg/m2 Paper record: n=72→63; 15.3% male; 76.4% white; mean age, 47 years; mean BMI, 34.8 kg/m2 |

All groups received the same standard behavioral intervention including daily self-monitoring of eating and exercise, group sessions, daily dietary goals, and weekly exercise goals. PDA: used a PDA with software to track exercise and energy and fat consumption PDA+feedback: used PDA with a custom software program to provide daily feedback messages providing positive reinforcement and guidance based on entries Paper record: Used standard paper diaries and were instructed to record caloric intake, fat gram content, and minutes of exercise |

Primary outcome: weight loss at 6 months | Percentage weight loss was statistically significant (p<0.01) for all treatment groups. Percentage (mean±SD): PDA, 5.5±7.0%; PDA+feedback, 7.3±6.6%; paper record, 5.3±5.9% | 6 |

| McDoniel et al.41 (2009): 12-week RCT comparing a standard nutritional program with computer self-monitoring |

n=111→80 Control: n=56→41; 37.5% male; 76.8% white; mean age, 44.9 years, mean BMI, 36.2 kg/m2; Internet and e-mail use (days/week), 6.0±1.6 Intervention: n=55→39; 38.2% male; 80.0% white; mean age, 45.9 years; mean BMI, 37.9 kg/m2; Internet and e-mail use (days/week), 5.7±1.7 |

Control: received a standard nutritional 3-day meal plan, 30-day paper journal for self-monitoring nutrition, activity, and body weight, and individual counseling by an exercise physiologist at 4 and 12 weeks. Intervention: received a nutritional program generated by MedGem© Analyzer based on individuals' measured resting metabolic rate, computerized self-monitoring software program (BalanceLog©), and individual counseling by an exercise physiologist at 4 and 12 weeks |

Primary outcome: body weight Secondary outcomes: arterial blood pressure, the Weight Efficacy Lifestyle questionnaire for assessing weight attitude, perceived behavioral control, and weight self-efficacy |

Body weight: There was no significant difference in body weight between groups over time (F1,110=1.77, p=0.19). Absolute change in body weight was significant for each group (control, −3.7±4.2 kg; intervention, −3.5±4.2 kg). Blood pressure: No difference in blood pressures between groups. Groups experienced a significant reduction in SBP (–4.0±11.8 mm Hg; p=0.02) Weight attitude, perceived behavioral control, and weight self-efficacy: showed significant improvement between baseline and 12 months in each group |

|

| Pellegrini et al.42 (2012): 6-month RCT comparing a technology-based system, an in-person behavioral weight loss intervention, and a combination of both |

n=51→39 SBWL: n=17→9; 0% male; 17.6% African American; mean age, 45.1 years; mean weight, 88.6 kg; mean BMI, 33.1 kg/m2 SBWL+technology: n=17→17; 23.5% male; 5.9% African American; mean age, 43.3 years; mean weight, 102.1 kg; mean BMI, 34.7 kg/m2 Technology: n=17→13; 17.6% male; 5.9% African American; mean age, 44.1 years; mean weight, 92.3 kg; mean BMI, 33.4 kg/m2 |

SBWL: Weekly meetings that encouraged behavioral modification, calorie restriction, increase in physical activity, and self-monitoring in paper diaries. Interventionists provided written feedback weekly. SBWL+technology: received the same meetings in addition to diet and exercise goals as SBWL. Received a BodyMedia (Pittsburgh, PA) Fit, an armband that tracked energy expenditure during waking hours. Interventionists provided written feedback weekly. Technology: Behavioral lessons were mailed each week. Participants received the same behavioral goals for diet and exercise and a monthly telephone call from a counselor. |

Primary outcome: Body weight Secondary outcome: physical activity |

Weight loss: significant for all groups but no significant difference among groups (SBWL, −7.1±6.2 kg; SBWL+technology, −8.8±5.0 kg; technology, −7.6±6.6 kg; p<0.001) Physical activity: significant increases reported in all groups but no significant difference among groups (SBWL, 473.9±800.7 kcal/week; SBWL+technology, 713.9±1,278.8 kcal.week; technology, 1,066.2±1,371 kcal/week) |

4 |

| Polzien et al.43 (2007): 12-week RCT to compare SBWP with INT-TECH and CON-TECH |

n=57→50 SBWP: n=19→16; 36.8% minority representation; mean age, 40.2 years; mean body weight, 89.1 kg; mean BMI, 33.6 kg/m2 INT-TECH: n=19→16; 36.8% minority representation; mean age, 41.1 years; mean body weight, 91.0 kg; mean BMI, 33.4 kg/m2 CON-TECH: n=19→18; 42.1% minority representation; mean age, 46.0 years; mean body weight, 86.6 kg; mean BMI, 32.6 kg/m2 |

SBWP: received seven in-person counseling sessions focused on diet and exercise behaviors; instructed to reduce caloric intake to 1,200–1,500 kcal/day, dietary fat ≤20% of total energy intake, and exercise to progress from 20 to 40 min/day 5 days/week CON-TECH: received all components of the SBWP with a wearable body monitor (Sensewear Pro armband; BodyMedia) for energy expenditure measurement. INT-TECH: received all components of SBWP, only used the armband during Weeks 1, 5, and 9, and were restricted to a paper diary during the “non-technology” weeks |

Primary outcome: weight loss Secondary outcomes: leisure-time physical activity and dietary intake |

Weight loss: SBWP, −4.1±2.8 kg; INT-TECH, 3.4±3.4 kg; CON-TECH, 6.2±4.0 kg. Significant weight loss was observed in all groups with no significant differences among groups. Leisure-time physical activity: significantly increased for all groups (p<0.01) Dietary intake: significantly decreased in all groups (p<0.01) with no significant differences among groups |

6 |

| Shuger et al.44 (2011): 9-month RCT comparing the efficacy of a caloric expenditure monitor with self-directed diet and group-based program on weight loss and waist circumference |

n=197→123 Standard care: n=50→26; 16% male; 60% white; mean age, 47.2 years GWL: n= 49→28; 20.4% male; 68.8% white; mean age, 46.8 years GWL+SWA: n=49→37; 18.4% male; 71.4% white; mean age, 45.7 years SWA: n= 49→32; 18.4% male; 67.4% white; mean age, 47.7 years |

Standard care: received a self-directed weight loss manual; asked to self-monitor intake and physical activity GWL: received 14 sessions over the first 4 months with weekly weigh-ins. During the final 5 months, participants received six personal phone-counseling sessions. SWA: received an armband, wristwatch, and Weight Management Solutions Web account. Participants received real-time feedback on energy expenditure and minutes spent in moderate and vigorous exercise. GWL+SWA: received all components of the GWL and SWA interventions |

Primary outcome: change in body weight Secondary outcome: waist circumference |

Weight reduction: There were significant reductions in weight for the GWL (1.86 kg), SWA (3.55 kg), and GWL+SWA (6.59 kg) groups (p≤0.05). GWL+SWA showed a significant weight reduction compared with the standard care group (p=0.04). Waist circumference: There was a significant reduction in waist circumference in all four groups (standard care, 3.49 cm [p<0.0004]; GWL, 2.42 cm [p<0.008]; SWA, 3.59 cm [p<0.001]; and GWL+SWA, 6.77 cm [p<0.001]). |

6 |

| Spring et al.45 (2013): 12-month RCT measuring weight loss through self-monitoring and coaching calls to supplement standard treatment |

n=70→69 Control: n=35; 43.4% male; 8.6% Hispanic, 22.9% black; mean age, 57.7 years; mean weight, 110.1 kg; mean BMI, 35.8 kg/m2 Intervention: n=35→34; 42% male; 2.9% Hispanic, 26.5% black; mean age, 57.7 years; mean weight, 113.7 kg; mean BMI, 36.9±5.4 kg/m2 |

Control: attendance at biweekly MOVE! sessions led by dieticians, psychologists, or physicians Intervention: attendance of the biweekly MOVE! Sessions. Self-monitoring caloric intake using a PDA every day for the first 2 weeks, then weekly until the end of 6 months, with biweekly individualized guidance based on uploaded data. During the weight maintenance phase (months 7–9) participants recorded data biweekly and then 1 week of data per month (months 10–12), with phone call feedback only provided if no data were submitted. |

Primary outcome: weight loss at 6 months and 12 months | Weight loss at 6 months: control, 1.0 kg (95% CI, −0.7, 2.5); intervention, 4.5 kg (95% CI, 2.1, 6.8) Weight loss at 12 months: control, −0.02 kg (95% CI, −2.1, 2.1); intervention, 2.9 kg (95% CI, 0.5, 6.2) |

7 |

| Turner et al.46 (2011): 6-month RCT comparing weight loss between podcast group and a podcast+mobile self-monitoring group |

n=96→86 Control: n=49→44; 27% male; 78% white; mean age, 43.2 years; mean BMI, 32.2 kg/m2 Intervention: n=47→42; 23% male; 75% white; mean age, 42.6 years; mean BMI, 32.9 kg/m2 |

Both groups received two podcasts per week for 3 months and two minipodcasts per week for 3–6 months; the content was designed using social cognitive theory constructs containing information on nutritional and physical activity, blogs, soap opera, and goal-setting activities. Control: received a book with calorie and fat gram amounts to assist with dietary intake Intervention: instructed to download a diet and physical activity monitoring application (FatSecret's Calorie Counter application) and Twitter. Participants logged onto Twitter at least once daily to read messages from the study coordinator and were encouraged to post daily. |

Primary outcome: change in body weight | Weight loss did not significantly differ by group at 6 months: control, –2.7±5.6%; intervention, −2.7±5.1% | 7 |

| Chat room | |||||

| Gow et al.47 (2010): 6-week RCT to demonstrate the feasibility of an online intervention to prevent weight gain among college students | n=159; 26% male; 22.2% African American, 10.8% Asian | Asked to report weekly weights and received a graph with individualized change in weight. Internet intervention: 45-min weekly sessions delivered via Blackboard© that focused on environmental, personal, and behavioral factors involved in healthy weight maintenance along with participatory activities Combined feedback and Internet intervention: Participants received the 6-week online intervention as well as weight and caloric feedback. |

Primary outcome: change in BMI | The combined intervention group had significantly lower BMI scores than the control group (mean, 24.13; SE, 0.09; p<0.05). The Internet intervention group and feedback group did not significantly differ on BMI compared with the control group (p>0.05). | 6 |

| Harvey-Berino et al.48 (2010): 6-month RCT to evaluate the efficacy of an Internet weight loss program and to determine if adding in-person sessions improves outcomes |

n=481→462 Internet: n=161→159; 8% male; 30% African American; mean age, 46.2 years; mean BMI, 35.6 kg/m2 In-person: n=158→150; 6% male; 29% African American; mean age, 46.7 years; mean BMI, 36.0 kg/m2 Hybrid: n=162→153; 6% male; 26% African American; mean age, 46.7 years; mean BMI, 35.6 kg/m2 |

All conditions received the 6-month behavioral weight loss program, which focused on modification of eating and exercise. In-person: Subjects in groups of 15–20; weekly sessions, a paper journal to monitor exercise and eating, and a calorie and fat counting book Internet: Participants met weekly in chat groups of 15–20 subjects and received materials for the session, access to an online database to monitor caloric intake in an online journal, and educational online resources. Hybrid: same resources as the Internet group but substituted one weekly online chat with an in-person meeting |

Primary outcome: weight loss and percentage of subjects achieving a 5% and 7% weight loss | Weight loss: in-person, −8.0±6.1 kg; Internet, −5.5±5.6 kg; hybrid, −6.0±5.5 kg (significant difference among conditions, p<0.01) Percentage of participants achieving 5% weight loss: no significant difference among groups (p=0.12) Percentage of participants achieving 7% weight loss: in-person, 56.0%; Internet, 37.7%; hybrid, 44.4% (significantly different) |

6 |

| Wing et al.49 (2006): 18-month RCT comparing Internet, face-to-face, and control interventions on weight maintenance |

n=314→291 participants who lost a mean of 19.3 kg over the previous 2 years were randomized to one of the three groups. Control: n=105→98; 17.1% male; mean age, 52.0 years; mean weight, 78.8 kg; mean BMI, 29.1 kg/m2; weight loss from highest weight in prior 2 years, 18.6±10.3 kg (17.9±7.0%) Internet: n=104→101; 19.2% male; mean age, 50.9 years; mean weight, 76.0 kg; mean BMI, 28.1 kg/m2; weight loss from highest weight in prior 2 years, 19.2±11.1 kg (18.3±7.7%) Face-to-face: n=105→92; 20.0% male; mean age, 51.0 years; mean weight, 78.6 kg; mean BMI, 28.7 kg/m2; weight loss from highest weight in prior 2 years, 20.0±11.6 kg (19.1±8.0%) |

Control: Participants received a quarterly newsletter with information about diet, exercise, and weight control. Face-to-face: attended weekly meetings for the first month and then monthly meetings. This included weigh-ins and group sessions. Participants were asked to weigh themselves weekly and report weight through an automated telephone system. Internet: Attended meetings with the same frequency as the face-to-face group but met online in a chat room, reviewing same content provided in the face-to-face group. They also had access to a message board and Web site that included treatment lessons |

Primary outcome: weight gain over a period of 18 months | Weight gain: face-to-face, 2.5±6.7 kg; Internet, 4.7±8.6 kg; control, 4.9±6.5 kg. There was a significant difference in weight gain between face-to-face and control groups (absolute difference, 2.4 kg; 95% CI, 0.002, 10.8; p=0.05) | 6 |

AF, automated feedback; BIT, behavioral Internet therapy; BMI, body mass index; CI, confidence interval; CON-TECH, continuous technology-based program; GWL, Group Weight Loss; HC, human e-mail counseling; INT-TECH, intermittent technology-based program; IQR, interquartile range; METs, metabolic equivalents to task; MMS, multimedia message service; PDA, personal digital assistant; PE, physical education; PNP, personalized nutrition planner; RCT, randomized controlled trial; RD, registered dietician; SBP, systolic blood pressure; SBWL, standard behavioral weight loss; SBWP, standard in-person behavioral weight control program; SD, standard deviation; SE, standard error; SMS, short message service; SWA, SenseWear armband; UC, usual care.

Data Synthesis

Total sample sizes ranged from 51 to 2,862 participants. Most studies (80%) included both men and women. Although 73% of the trials included more than one ethnic group, only 22% included more than 40% minorities. No studies reported results by sex or ethnicity. A little over half of the participants (58%) had a mean age of >45 years. Approximately one-quarter (23%) of the trials included obese individuals only, whereas the remaining 77% included both overweight and obese individuals.

A variety intervention strategies and delivery modes were represented in the trials; however, all of the interventions focused on providing information and/or counseling on both diet and physical activity. Technology intervention modes included online chat rooms (10%), text messaging or e-mail (15%), self-monitoring with smartphone/mobile device (17.5%), and Web-based (57.5%). Length of intervention periods varied from 5 weeks to 24 months. Adherence to the intervention was described in 73% of the studies; however, studies varied greatly on how adherence was defined. Attrition rates were reported in 34 (87%) of the trials. Among those trials that described attrition rates, attrition rates ranged from 1% to 84%, with 38% reporting attrition rates greater than 20%.

More than half of the trials (53%) reported statistically significant weight loss in the intervention group as compared with the control group. These results varied by technology mode: online chat rooms (50%), text messaging or e-mail (67%), self-monitoring with technology (43%), and Web-based (48%). In total, 70% of the trials completed an intention-to-treat analysis. Among those trials using intention-to-treat analysis, 62% reported statistically significant weight loss in the intervention compared with the control group. Only two studies10,11 reported on cost-effectiveness along with the main results.

The results of the Cochrane risk of bias scoring are presented in Table 2. Thirty-one of the studies (79%) were assessed as having a low risk of bias, and eight studies (21%) were assessed as presenting a high risk of bias according to Cochrane direction.

Discussion

This systematic review suggests that technology-assisted interventions may be effective for weight loss among overweight and obese adults. More specifically, a high proportion of the trials incorporating text messaging or e-mail showed that technology-assisted behavioral interventions produced significantly greater weight loss compared with controls. Receiving real-time feedback, encouragement, and/or coaching appeared to be an important component of the successful interventions. The lack of statistical significance using other technology modalities may be due to small sample sizes, high attrition rates, inadequate intervention dose due to lack of fidelity, or improved outcomes in the usual-care groups. Translation of an effective intervention into clinical practice depends largely on the cost-effectiveness of the intervention, yet there was little attention paid to economic analysis. Unlike what has been reported in other systematic reviews, the studies reviewed here had diversity in terms of the sex and ethnicity of participants.

Evaluation of potential bias yielded scores ranging from 4 to 9, with a large majority (79%) of studies rated as having a low risk of bias. However, the most common deficiency for the majority of studies across the rating criteria was a high rate of attrition, which is a common challenge in telehealth studies. Although intention-to-treat analyses were conducted in a majority of these studies, the impact of high attrition rates on the ability to translate the results is of concern.

There was inconsistent reporting of intervention fidelity across studies. For those who reported on adherence, various process measures were used, which makes it difficult to compare across studies.

Only a small percentage of the studies reviewed used mobile platforms such as Android® (Google, Mountain View, CA) phones or the iPhone® (Apple, Cupertino, CA) for the delivery of weight loss interventions. As smartphone software technology becomes more sophisticated and user-friendly and able to connect wirelessly with other monitoring devices, the potential to enable the delivery of behavioral weight loss interventions and monitor their effectiveness is exciting and should be a focus of future research.

Limitations

There were several limitations to this systematic review. The studies were too heterogeneous in intervention strategy to permit pooling of data for meta-analysis, which might have provided additional insights. The review was limited to the past 10 years, and the sample size was small. We were unable to identify unpublished studies or those not referenced in PubMed, CINAHL, or Embase. Thus, the study characteristics and findings are limited to those found in published reports. The inclusion criteria were somewhat stringent in an effort to maximize the likelihood of unbiased results, which may have resulted in the exclusion of some valuable studies.

Implications for Future Research

The results of this systematic review raise several important questions for future research in this area. What is the optimal combination and dose of intervention strategies? Which features are most responsible for changes in outcomes? What are the long-term outcomes of the interventions? What subgroups benefit most/least from the interventions? What is the cost- effectiveness of various interventions? What are the results when translated into real-world settings?

Conclusions

The findings of this review suggest that technology-assisted weight loss interventions may result in clinically significant weight loss among overweight and obese adults. Although there was considerable variability in the content and structure of the technology-assisted interventions, some common behavior change strategies included goal setting, self-monitoring, feedback, and support from coaches. Providers should assure that these components are present in technology-assisted weight loss interventions they recommend to their patients. There have been only a few published reports of the effectiveness of mobile phones for weight loss and maintenance. The widespread use of smartphones could significantly change our ability to deliver evidence-based weight loss interventions and empower individuals to take charge of their health.

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Ogden CL. Prevalence of obesity and trends in the distribution of body mass index among US adults, 1999–2010. JAMA 2012;307:491–497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clinical guidelines on the identification, evaluation, and treatment of overweight and obesity in adults—The evidence report. National Institutes of Health. Obes Res 1998;6(Suppl 2):51S–209S [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goodpaster BH, Delany JP, Otto AD, Kuller L, Vockley J, South-Paul JE, Thomas SB, Brown J, McTigue K, Hames KC, Lang W, Jakicic JM. Effects of diet and physical activity interventions on weight loss and cardiometabolic risk factors in severely obese adults: A randomized trial. JAMA 2010;304:1795–1802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Appel LJ, Champagne CM, Harsha DW, Cooper LS, Obarzanek E, Elmer PJ, Stevens VJ, Vollmer WM, Lin PH, Svetkey LP, Stedman SW, Young DR. Effects of comprehension lifestyle modification on blood pressure control: Main results of the PREMIER clinical trial. JAMA 2003;289:2083–2093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stewart KJ, Bacher AC, Turner KL, Fleg JL, Hees PS, Shapiro EP, Tayback M, Ouyang P. Effect of exercise on blood pressure in older persons: A randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med 2005;1665:756–762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rao G, Burke LE, Spring BJ, Ewing LJ, Turk M, Lichtenstein AH, Cornier MA, Spence JD, Coons M; American Heart Association Obesity Committee of the Council on Nutrition, Physical Activity and Metabolism, Council on Clinical Cardiology, Council on Cardiovascular Nursing, Council on the Kidney in Cardiovascular Disease, Stroke Council. New and emerging weight management strategies for busy ambulatory settings: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association endorsed by the Society of Behavioral Medicine. Circulation 2011;124:1182–1203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coons MJ, Demott A, Buscemi J, Duncan JM, Pellegrini CA, Steglitz J, Pictor A, Spring B. Technology interventions to curb obesity: A systematic review of the current literature. Curr Cardiovasc Risk Rep 2012;6:120–134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bacigalupo R, Cudd P, Littlewood C, Bissell P, Hawley MS, Buckley Woods H. Interventions employing mobile technology for overweight and obesity: An early systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Obes Rev 2013;14:279–291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Furlan AD, Pennick V, Bombardier C, van Tulder M; Editorial Board, Cochrane Back Review Group. 2009 updated method guidelines for systematic reviews in the Cochrane Back Review Group. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2009;34:1929–1941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hersey JC, Khavjou O, Strange LB, Atkinson RL, Blair SN, Campbell S, Hobbs CL, Kelly B, Fitzgerald TM, Kish-Doto J, Koch MA, Munoz B, Peele E, Stockdale J, Augustine C, Mitchell G, Arday D, Kugler J, Dorn P, Ellzy J, Julian R, Grissom J, Britt M. The efficacy and cost-effectiveness of a community weight management intervention: A randomized controlled trial of the health weight management demonstration. Prev Med 2012;54:42–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McClung HL, Sigrist LD, Smith TJ, Karl JP, Rood JC, Young AJ, Bathalon GP. Monitoring energy intake: A hand-held personal digital assistant provides accuracy comparable to written records. J Am Diet Assoc 2009;109:1241–1245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brindal E, Freyne J, Saunders I, Berkovsky S, Smith G, Noakes M. Features predicting weight loss in overweight or obese participants in a Web-based intervention: Randomized trial. J Med Internet Res 2012;14:e173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cussler EC, Teixeira PJ, Going SB, Houtkooper LB, Metcalfe LL, Blew RM, Ricketts JR, Lohman J, Stanford VA, Lohman TG. Maintenance of weight loss in overweight middle-aged women through the Internet. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2008;16:1052–1060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lachausse RG. My Student Body: Effects of an Internet-based prevention program to decrease obesity among college students. J Am Coll Health 2012;60:324–330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Touger-Decker R, Denmark R, Bruno M, O'Sullivan-Maillet J, Lasser N. Workplace weight loss program; comparing live and Internet methods. J Occup Environ Med 2010;52:1112–1118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Appel LJ, Clark JM, Yeh HC, Wang NY, Coughlin JW, Daumit G, Miller ER, 3rd, Dalcin A, Jerome GJ, Geller S, Noronha G, Pozefsky T, Charleston J, Reynolds JB, Durkin N, Rubin RR, Louis TA, Brancati FL. Comparative effectiveness of weight-loss interventions in clinical practice. N Engl J Med 2011;365:1959–1968 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bennett GG, Herring SJ, Puleo E, Stein EK, Emmons KM, Gillman MW. Web-based weight loss in primary care: A randomized controlled trial. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2010;18:308–313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chambliss HO, Huber RC, Finley CE, McDoniel SO, Kitzman-Ulrich H, Wilkinson WJ. Computerized self-monitoring and technology-assisted feedback for weight loss with and without an enhanced behavioral component. Patient Educ Couns 2011;85:375–382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Collins CE, Morgan PJ, Jones P, Fletcher K, Martin J, Aguiar EJ, Lucas A, Neve MJ, Callister R. A 12-week commercial Web-based weight-loss program for overweight and obese adults: Randomized controlled trial comparing basic versus enhanced features. J Med Internet Res 2012;14:e57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gold BC, Burke S, Pintauro S, Buzzell P, Harvey-Berino J. Weight loss on the web: A pilot study comparing a structured behavioral intervention to a commercial program. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2007;15:155–164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gabriele JM, Carpenter BD, Tate DF, Fisher EB. Directive and nondirective e-coach support for weight loss in overweight adults. Ann Behav Med 2011;41:252–263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hunter CM, Peterson AL, Alvarez LM, Poston WC, Brundige AR, Haddock CK, Van Brunt DL, Foreyt JP. Weight management using the Internet. A randomized controlled trial. Am J Prev Med 2008;34:119–126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kraschnewski JL, Stuckey HL, Rovniak LS, Lehman EB, Reddy M, Poger JM, Kephart DK, Coups EJ, Sciamanna CN. Efficacy of a weight-loss website based on positive deviance. A randomized trial. Am J Prev Med 2011;41:610–614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McConnon A, Kirk SF, Cockroft JE, Harvey EL, Greenwood DC, Thomas JD, Ransley JK, Bojke L. The Internet for weight control in an obese sample: Results of a randomised controlled trial. BMC Health Serv Res 2007;7:206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Micco N, Gold B, Buzzell P, Leonard H, Pintauro S, Harvey-Berino J. Minimal in-person support as an adjunct to Internet obesity treatment. Ann Behav Med 2007;33:49–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Morgan PJ, Lubans DR, Collins CE, Warren JM, Callister R. 12-month outcomes and process evaluation of the SHED-IT RCT: An Internet-based weight loss program targeting men. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2011;19:142–151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Morgan PJ, Collins CE, Plotnikoff RC, Cook AT, Berthon B, Mitchell S, Callister R. Efficacy of a workplace-based weight loss program for overweight male shift workers: The Workplace POWER (Preventing Obesity Without Eating like a Rabbit) randomized controlled trial. Prev Med 2011;52:317–325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mouttapa M, Robertson TP, McEligot AJ, Weiss JW, Hoolihan L, Ora A, Trinh L. The Personal Nutrition Planner: A 5-week, computer-tailored intervention for women. J Nutr Educ Behav 2011;43:165–172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Paineau DL, Beaufils F, Boulier A, Cassuto DA, Chwalow J, Combris P, Couet C, Jouret B, Lafay L, Laville M, Mahe S, Ricour C, Romon M, Simon C, Tauber M, Valensi P, Chapalain V, Zourabichvili O, Bornet F. Family dietary coaching to improve nutritional intakes and body weight control: A randomized controlled trial. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2008;162:34–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Patrick K, Calfas KJ, Norman GJ, Rosenberg D, Zabinski MF, Sallis JF, Rock CL, Dillon LW. Outcomes of a 12-month Web-based intervention for overweight and obese men. Ann Behav Med 2011;42:391–401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rothert K, Strecher VJ, Doyle LA, Caplan WM, Joyce JS, Jimison HB, Karm LM, Mims AD, Roth MA. Web-based weight management programs in an integrated health care setting: A randomized, controlled trial. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2006;14:266–272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.van Wier MF, Ariens GA, Dekkers JC, Hendriksen IJ, Smid T, van Mechelen W. Phone and e-mail counselling are effective for weight management in an overweight working population: A randomized controlled trial. BMC Public Health 2009;9:6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Webber KH, Tate DF, Michael Bowling J. A randomized comparison of two motivationally enhanced Internet behavioral weight loss programs. Behav Res Ther 2008;46:1090–1095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tate DF, Jackvony EH, Wing RR. Effects of Internet behavioral counseling on weight loss in adults at risk for type 2 diabetes: A randomized trial. JAMA 2003;289:1833–1836 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tate DF, Jackvony EH, Wing RR. A randomized trial comparing human e-mail counseling, computer-automated tailored counseling, and no counseling in an Internet weight loss program. Arch Intern Med 2006;166:1620–1625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Haapala I, Barengo NC, Biggs S, Surakka L, Manninen P. Weight loss by mobile phone: A 1-year effectiveness study. Public Health Nutr 2009;12:2382–2391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Patrick K, Raab F, Adams MA, Dillon L, Zabinski M, Rock CL, Griswold WG, Norman GJ. A text message-based intervention for weight loss: Randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res 2009;11:e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shapiro JR, Koro T, Doran N, Thompson S, Sallis JF, Calfas K, Patrick K. Text4Diet: A randomized controlled study using text messaging for weight loss behaviors. Prev Med 2012;55:412–417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thomas RE, Russell M, Lorenzetti D. Interventions to increase influenza vaccination rates of those 60 years and older in the community. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010;(9):CD005188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Burke L, Jancey J, Howat P, Lee A, Kerr D, Shilton T, Hills A, Anderson A. Physical Activity and Nutrition Program for Seniors (PANS): Protocol of a randomized controlled trial. BMC Public Health 2010;10:751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McDoniel SO, Wolskee P, Shen J. Treating obesity with a novel hand-held device, computer software program, and Internet technology in primary care: The SMART motivational trial. Patient Educ Couns 2010;79:185–191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pellegrini CA, Verba SD, Otto AD, Helsel DL, Davis KK, Jakicic JM. The comparison of a technology-based system and an in-person behavioral weight loss intervention. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2012;20:356–363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Polzien KM, Jakicic JM, Tate DF, Otto AD. The efficacy of a technology-based system in a short-term behavioral weight loss intervention. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2007;15:825–830 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shuger SL, Barry VW, Sui X, McClain A, Hand GA, Wilcox S, Meriwether RA, Hardin JW, Blair SN. Electronic feedback in a diet- and physical activity-based lifestyle intervention for weight loss: A randomized controlled trial. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2011;8:41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Spring B, Duncan JM, Janke EA, Kozak AT, McFadden HG, DeMott A, Pictor A, Epstein LH, Siddique J, Pellegrini CA, Buscemi J, Hedeker D. Integrating technology into standard weight loss treatment: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA Intern Med 2013;173:105–111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Turner JA, Mancl L, Huggins KH, Sherman JJ, Lentz G, LeResche L. Targeting temporomandibular disorder pain treatment to hormonal fluctuations: A randomized clinical trial. Pain 2011;152:2074–2084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gow RW, Trace SE, Mazzeo SE. Preventing weight gain in first year college students: An online intervention to prevent the “freshman fifteen.” Eat Behava 2010;11:33–39 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Harvey-Berino J, West D, Krukowski R, Prewitt E, VanBiervliet A, Ashikaga T, Skelly J. Internet delivered behavioral obesity treatment. Prev Med 2010;51:123–128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wing RR, Tate DF, Gorin AA, Raynor HA, Fava JL. A self-regulation program for maintenance of weight loss. N Engl J Med 2006;355:1563–1571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]