Abstract

Aim

To describe trends in the HIV epidemic among drug users (DUs) in China from 1995 to 2011.

Design, setting and participants

Datasets from China's national HIV/AIDS case reporting and sentinel surveillance systems as of December 2011 were used separately for descriptive analysis.

Measures

Changes in the geographic distribution of the number of HIV cases and HIV prevalence among injecting drug users (IDUs) and non-IDUs were examined. We also analyzed changes in HIV prevalence among the broader DU population, and drug use-related behaviors including types of drugs used, recent injecting, and recent needle sharing in the context of the rapid scale-up of DU sentinel sites and national harm reduction programs.

Findings

The HIV epidemic among China's DUs is still highly concentrated in five provinces. Here, HIV prevalence peaked at 30.3% (95% CI [28.6, 32.1]) among IDUs in 1999, and then gradually decreased to 10.9% (95% CI [10.6, 11.2]) by 2011. We observed a rapid increase in the use of “nightclub drugs” among DUs from 1.3% in 2004 to 24.4% in 2011. A decline in recent needle sharing among current IDU from 19.5% (95% CI [19.4, 19.6]) in 2006 to 11.3% (95% CI [11.2, 11.4]) in 2011 was found to be correlated with the rapid scale-up of methadone maintenance treatment (MMT; r(4) = - .94, p = 0.003) harm reduction efforts.

Conclusions

While needle sharing among current injecting drug users in China has declined dramatically and is correlated with the scale-up of national harm reduction efforts, the recent, rapid increased use of “nightclub drugs” presents a new challenge.

Keywords: HIV infection, drug user, behaviour, harm reduction, China

Introduction

The earliest evidence of an HIV epidemic in China was identified in 1989, among injecting drug users (IDUs) in southern Yunnan province [1]. Findings from geospatial analysis of HIV subtypes, behavioral surveys among IDUs and their sexual partners, and routine surveillance activities indicate that needle sharing among IDUs, and sexual contact between IDUs and sex workers, were the major driver of later sub-epidemics across mainland China [2]. As of the end of 2011, the number of people infected with HIV via injecting drug use was estimated at greater than 221,000 [3].

In 1985, the Chinese government had established a national HIV case reporting system (CRS) [4,5], when the first ever case of HIV on the mainland was identified in a foreign visitor [4]. From 1985 until 1995, CRS remained China's primary surveillance tool. In 1995, the government launched the sentinel surveillance system to conduct cross-sectional surveys in 42 sites among four key affected populations (KAPs)—drug users (DUs, including those who inject and those who do not), female sex workers, sexually transmitted disease clinic patients, and long-distance truck drivers. This system expanded and evolved in 2004 to monitor both HIV prevalence and HIV related behaviors [6,7] among HIV KAPs. By 2010, the total number of HIV sentinel surveillance sites had been expanded to 1,888, targeting eight KAPs. Since 2010, tests for HIV, syphilis, and hepatitis C virus (HCV) infections have been routinely performed for all participants recruited during the surveillance period [8].

In recent years, harm reduction programs have been implemented throughout China [9,10]. The two largest of these aimed at harm reduction among DUs are the national methadone maintenance treatment (MMT) program and needle exchange program (NEP). MMT was introduced in 1993 [11], and was backed as a treatment program since 2004 [12], then quickly expanded from its original eight clinics in 2004, to 320 clinics in 2006, and to 738 clinics in 2011. Opiate users covered by the MMT program increased from 1,209 in 2004, to 37,345 in 2006, and to 344,254 in 2011, cumulatively [3]. NEP was first introduced to increase commercial availability and accessibility of needles [13]. Until a successful intervention trial in Guangdong and Guangxi [14,15], 91 pilot NEP sites were established in 2003 [16]. Similar to the MMT program, expansion of NEP also occurred after 2006, increasing to 775 sites in 2007, and to 937 sites in 2011. IDUs covered by NEP average approximately 50,000 monthly since 2007 [3,17,18].

Roughly ten years have passed since the initiation of these harm reduction programs in China. Although studies of the initial pilot MMT and NEP programs provided sufficient evidence of their effectiveness to merit their expansion nationwide [19,20], their impact on the national HIV epidemic has not yet been reported. In the present study, we collected information from China's national HIV/AIDS case reporting system and sentinel surveillance system. We aimed to describe the characteristics and trends of the HIV epidemic among the DU, specifically the IDU, population in China over time (1995-2011) and secondarily, to describe changes in the behavior of DUs and IDUs over the same time period.

Methods

For the purposes of this study, a ‘DU’ was defined as a drug user who used “traditional drugs” (i.e., heroin, opium, opiate analgesics, cocaine, and marijuana, as defined in China's sentinel surveillance guidelines) [20-22] and/or the newer, so-called “nightclub drugs” (i.e., methamphetamine, ketamine, methylene dioxymetham-phetamine [MDMA], and Magu pills [a mixture of methamphetamine and caffeine]) by any means, including via injection. An ‘IDU’ was defined as a DU who had injected drugs in their lifetime. A ‘current IDU’ was defined as an IDU who had injected drugs in the past one month. A ‘non-IDU’ was defined as a DU who had never injected drugs in their lifetime.

Data sources and collection

All data included in this study were collected from the national HIV/AIDS CRS and the national HIV sentinel surveillance system. The datasets from each system were evaluated separately; they were not combined.

Issued in 1989, the Law of the People's Republic of China on the Prevention and Treatment of Infectious Diseases added HIV/AIDS to its listing of mandatorily reportable diseases. At hospitals, HIV testing became mandatory prior to surgery and other invasive diagnostic and treatment procedures. HIV testing was also conducted at voluntary counseling and testing sites, typically located at hospitals and local Center for Diseases Control and Prevention (CDC) clinics. Once HIV infection is confirmed (screening by two-ELISA method and a confirmatory test by Western blot), the provider informs the patient of their HIV-positive status and conducts a face-to-face interview to complete a case reporting form (CRF). Name, identification number, age, gender, occupation, and current address are collected as well as self-reported history of high-risk behavior. Likely transmission route is judged by the provider based on the patient's behavioral history. Thus, HIV-positive patients who self-report ever injecting drugs in their lifetime during this initial CRF interview are judged to be infected with HIV via drug injection. Completed CRFs are submitted to the local CDC. In 2005, the CRS was embedded into the newly-launched, web-based China Information System for Disease Control and Prevention, and HIV/AIDS cases are required to be reported online within 24 hours of identification [4]. The National Center for AIDS/STD Control and Prevention (NCAIDS) became responsible for regular auditing of data timeliness and quality.

The national HIV sentinel surveillance system was established in 1995 for the purpose of estimating HIV prevalence among high-risk groups, including DUs [5]. As of 2011, 303 sentinel sites focused primarily on DUs. Each year, an anonymous cross-sectional survey is conducted from April to June. For DU surveillance specifically, participants are recruited by a stratified snowball method within DU communities, regardless of their HIV testing history and serostatus. Seeds are selected from among peer educators, community volunteers, and others with extensive networks among the DU community. DUs already enrolled in methadone maintenance treatment (MMT) are excluded from sampling unless they have had at least one positive urine opiate screen result in the three months prior to the survey [20]. Target sample size for each DU sentinel site is 400. A uniform questionnaire is used for face-to-face interviewing of participants at all DU sentinel sites. At each interview, participants provide demographic information, drugs used, and drug use behavioral information (i.e., types of drugs used, method of drug use in the past one month, and frequency of drug use), and a blood sample for HIV testing (screening test by two-ELISA method) [21]. Syphilis testing was added in 2004 [7], and HCV testing was added in 2009 [22]. Prior to 2007, an EpiData (Version 3.1) database was used for data input and management and all sentinel surveillance data were reported to NCAIDS by encrypted EpiData files. In 2007, a client software program was designed for data input and management, which is uploaded in real-time to the web server at NCAIDS.

Data from both the national HIV/AIDS CRS and the national HIV sentinel surveillance system were used for this study. From the CRS, all records as of December 31, 2011 were downloaded, but only those cases judged to be infected by injecting drugs were selected (i.e., this dataset included IDUs only) and sorted by the year in which the case was first reported. From the sentinel surveillance system, all annual data as of December 31, 2011 were downloaded for all DUs (i.e., this dataset included all DUs, meaning IDUs and non-IDUs together). Those DU sentinel sites having sample sizes of less than 50 respondents in a single year were excluded from analysis.

Data analysis

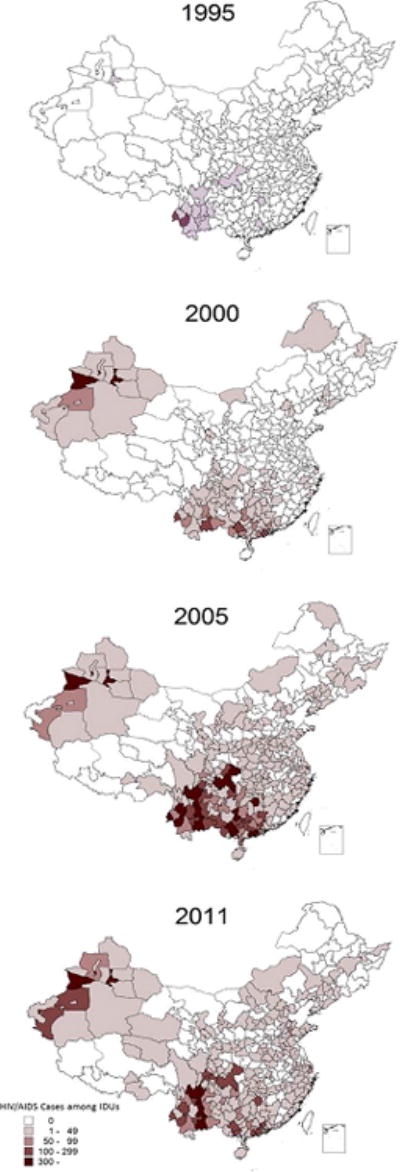

Annually reported HIV/AIDS cases from the national HIV/AIDS CRS were sorted by county and displayed on maps color-coded for numbers of cases using ArcInfo software (ESRI ® ArcMap™, Version 10.0) to examine geographical changes in the HIV epidemic in China over time (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Geographical distribution of the number of HIV/AIDS cases reported among IDUs in the years 1995, 2000, 2005, and 2011. Variation in color indicates the numbers of reported HIV/AIDS cases by county. Lines within the map indicate province and county borders. All data presented here originated from the national HIV/AIDS CRS and include those cases judged to be infected with HIV via unsafe injecting behaviors, thus all cases included are defined as IDUs.

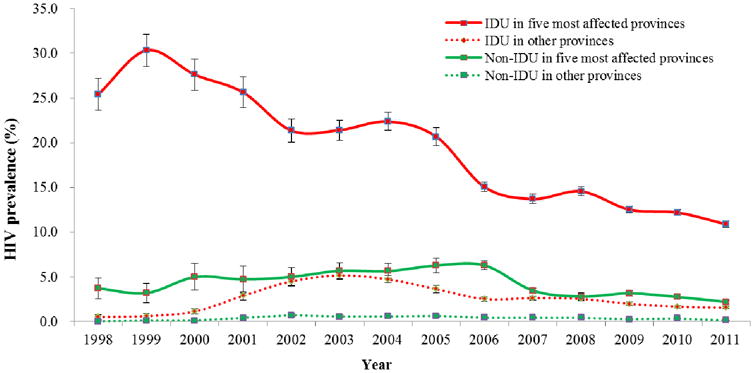

HIV prevalence data came from the national sentinel surveillance system, specifically DU sentinel sites, which include data for all DUs (both IDU and non-IDU). HIV prevalence estimates from the national HIV sentinel surveillance system were calculated for the five most affected provinces and for all other provinces, separated into IDU and non-IDU groups (Figure 2). Prevalence was calculated as the number of HIV-positive respondents as the numerator and the total number of respondents as the denominator and presented with 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Figure 2.

Graphical representation of changes in HIV prevalence over time (1998 to 2011) among IDUs (DUs judged to have become infected with HIV via unsafe injecting practices) and among non-IDUs (DUs judged to have become infected with HIV via transmission routes other than injecting drugs) in the five most affected provinces (red)—Yunnan, Guangxi, Sichuan, Xinjiang, and Guangdong—as compared to all other provinces (green). Bars at each data point represent the 95% confidence intervals of prevalence. All data presented here were obtained from the national HIV sentinel surveillance system.

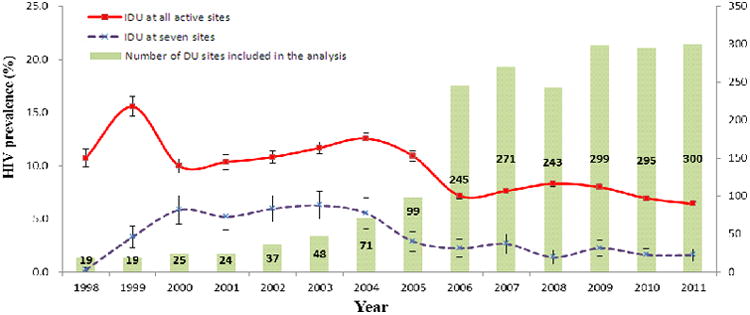

HIV prevalence among IDUs alone, nationwide, is taken from annual sentinel surveillance data. To illustrate the possible impact of the expansion of the number of DU sentinel surveillance sites in China after 2005, the overall HIV prevalence among IDUs only for all active sites each year and for the seven sites with the longest history (data collected at these seven sites each year between 1998 and 2011) was plotted along with the total number of active sentinel sites each year (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Graphical representation of the trends in HIV prevalence among IDUs only: nationwide (all active sentinel sites; red), and at the seven sites having longest surveillance time span form 1998 to 2011 (purple). Bars at each data point represent the 95% confidence intervals. The numbers of active sentinel sites for each year appear in the form of light green bars to highlight the rapid scale-up of China's national sentinel surveillance system after 2005. Those DU sentinel sites having sample sizes of less than 50 respondents in a single year were excluded from analysis (target sample size is 400 respondents per sentinel site). All data presented here came from the national HIV sentinel surveillance system.

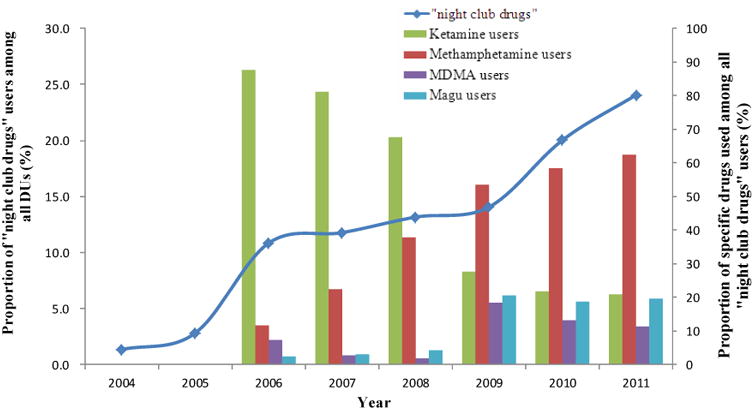

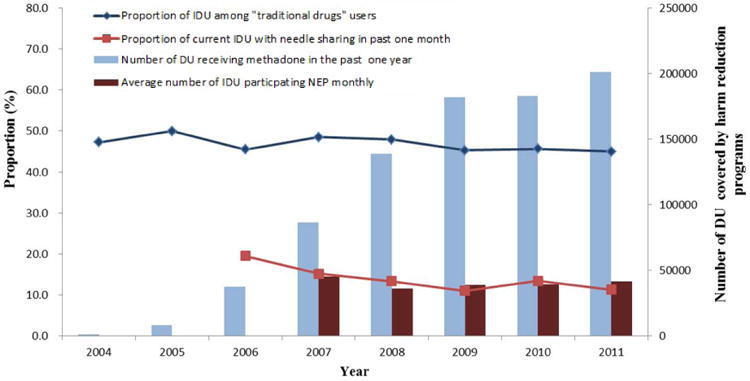

Data related to drug use behaviors among all DUs come from national sentinel surveillance data collected after 2004. To calculate the proportions of “nightclub drug” users, all DU respondents in the survey year was the denominator and all DU respondents who self-reported using “nightclub drugs” was the numerator. Similar calculations were done for each individual specific “nightclub drug” (Figure 4). To calculate the proportions of “traditional drug” users, all IDU respondents in the survey year was the denominator and all IDU respondents who self-reported using “traditional drugs” was the numerator. To calculate the proportions of current IDUs who engaged in recent needle sharing, all current IDU respondents in the survey year was the denominator and all IDU respondents who self-reported needle sharing in the past one month was the numerator (Figure 5).

Figure 4.

Graphical representation of the rapid increase in the prevalence of “nightclub drug” users among DU sentinel surveillance survey respondents from 2004 to 2011. Prevalence of use of the four most popular “nightclub drugs” among “nightclub drug” users. All data presented here came from sentinel surveillance system. These data illustrate the very recent and rapid escalation in use of “nightclub drugs” and the diversity of drugs used. Due to the large sample size, 95% confidence intervals are not shown in the figure.

Figure 5.

Graphical representation of changes over time (2004 to 2011) in the proportion of current IDUs (i.e., IDUs who self-reported injecting drugs in the most recent one month prior the sentinel surveillance survey) among “traditional drug” users and the proportion of current IDUs who self-reported recent needle sharing behavior. The scaling up of MMT and NEP harm reduction programs is also shown. All data were obtained from the national HIV sentinel surveillance system. Needle sharing information was not collected before 2006. Due to the large sample size, 95% confidence intervals are not shown in the figure.

Pearson correlation tests were used to investigate a possible relationship between trends in DU behavioral characteristics and the expansion of harm reduction programs. All data analysis was performed using with SPSS software (SPSS, Inc., Version 18.0.0).

Ethical approval

This study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of NCAIDS, China CDC. Data used in this study were collected via routine monitoring and surveillance. All personal identifiers were removed from the final national HIV/AIDS CRS dataset. National sentinel surveillance data were collected anonymously and were thus already free of name-linked information. Therefore, written informed consent was not required.

Results

Geographical trends in HIV prevalence

Figure 1 shows maps of the distribution of identified HIV/AIDS cases among IDUs. In 1995, the epidemic was highly concentrated in southwestern Yunnan province. Five years later in 2000, the HIV epidemic among IDU spread to neighboring southwest provinces and another sub-epidemic began in Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region in the northwest. In 2005, the epidemic among IDUs spread to the northeast, and by 2011, HIV-positive IDU had been reported in 1,703 prefectures nationwide. After two decades of expansion of the HIV epidemic among IDUs in China, it is clear that southwest provinces (Yunnan, Sichuan, Guangxi, and Guangdong) and Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region in the far northwest still bear a disproportionately large HIV burden relative to the rest of the country.

This geographical pattern in the distribution of the HIV epidemic is also reflected in data for all DUs (IDUs and non-IDUs) from the national sentinel surveillance system. As shown in Figure 2, the prevalence of HIV among both IDUs and non-IDUs was much higher and peaked earlier in the five most affected provinces than in all other provinces combined. HIV prevalence among IDUs in the five provinces peaked in 1999 at 30.3% (95% CI [28.6, 32.1]) and decreased to 10.9% (95% CI [10.6, 11.2]) by 2011. By contrast, HIV prevalence among IDUs in all other provinces peaked in 2003 at 5.2% (95% CI [4.7, 5.7]) and then declined to 1.6% (95% CI [1.4, 1.7]) by 2011. Non-IDUs in the five most affected provinces also had much higher HIV prevalence as compared to all other provinces from 1998 to 2011. HIV prevalence among non-IDU in five provinces reached 6.3% (95% CI [5.5, 7.1]) in 2005 and then declined to 2.2% (95% CI [2.0, 2.4]) by 2011, whereas HIV prevalence in all other provinces was less than 1% over the entire time period.

Nationwide trends in HIV prevalence

Figure 3 shows changes in the HIV prevalence among IDUs nationwide, annually from 1998 to 2011. After a rapid increase before 2000, HIV prevalence among IDUs nationwide increased moderately to a peak of 10.9% (95% CI [10.4, 11.4]) in 2004. Since 2004, there has been a decline, and as of 2011, nationwide HIV prevalence among IDUs was 6.4% (95% CI [6.2, 6.6]). This period of lower prevalence from 2006 to 2011 coincided with the rapid scale-up of sentinel surveillance sites, and thus could have resulted merely from a dilution effect (i.e., sentinel sites were opened in high prevalence areas first, and low prevalence areas later). To eliminate the potential dilution effect, data from the seven sentinel sites with the longest history (having HIV prevalence survey data each year from 1998 to 2011) was overlaid on the same graph. These data show that HIV prevalence at these seven sites reflects a trend similar to the national data, as HIV prevalence for these seven sites declined from 6.3% (95% CI [5.0, 7.6]) in 2003, to 1.6% (95% CI [1.0, 2.2]) in 2011.

Nationwide trends in drug use behaviors

As shown in Figure 4, DUs engaging in “nightclub drug” use increased from 1.3% in 2004, to 24.4% in 2011. The most popular of these drugs were ketamine and methamphetamine, which together accounted for the drugs of choice among the majority of “nightclub drug” users from 2004 to 2011.

Trends in injecting behavior in the past one month among “traditional drug” users and needle sharing among current IDUs (injecting in the past one month) are shown in Figure 5. While the proportion of IDUs among “traditional drug” users decreased slightly from 47.2% (95% CI [47.1, 47.3]) in 2004 to 44.8% (95% CI [44.9, 44.9]) in 2011, the proportion of current IDUs who reported sharing needles in the past one month decreased from 19.5% (95% CI [19.4, 19.6]) in 2006 to 11.3% (95% CI [11.2, 11.4]) in 2011. Pearson correlation test results show that this decrease in needle sharing was correlated with the expansion of MMT (r(4) = - .94, p = .003, data not shown).

Although MMT participants are excluded from sentinel surveys unless they have at least one positive urine opiate screen result in the three months prior to the survey, we compared the injection behavior among sentinel survey respondents who had ever participated in MMT to respondents who had never participated in MMT. We found that among DUs who had participated in MMT, fewer were current IDUs (74.3%, 95% CI [74.1, 74.5]) compared to DUs who had never participated (78.3%, 95% CI [78.1, 78.5], χ2 = 133.15, p < .001, data not shown).

Discussion

We found that despite the broad geographical expansion of China's HIV epidemic over the past two decades, most cases are still concentrated in the five provinces initially affected by the epidemic—Yunnan, Sichuan, Guangxi, Guangdong, and Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region. This geographical pattern has also been observed in several previous studies [23,24] and mirrors global drug trafficking activities, as the majority of heroin and opium in China was brought in from Myanmar into Yunnan, or from Vietnam into Guangxi, and a small proportion from the Middle East into Xinjiang [25]. The easy accessibility of drugs in these five provinces gave rise to the rapidly expanding HIV epidemic among IDUs in these areas.

As the epidemic matured over time, HIV spread to non-IDUs as well, likely via commercial and non-commercial sex. This is evidenced by Yunnan, Guangxi, and Xinjiang provinces reporting high HIV prevalence among female sex workers and their clients [26,27], as well as pregnant women [28,29], as early as 2004. Similar secondary sexual transmission patterns have been observed in several other countries in the region. For example, India and Pakistan have reported secondary HIV transmission among non-IDU spouses of HIV-positive IDU [30,31], and a molecular epidemiological study has identified linkages among the sexual and injecting drug use epidemics in Thailand [2]. Efforts to control the spread of HIV within and outside of these most-affected five provinces must therefore be focused on both IDUs and their sexual partners.

We also found that changes in drug use-related behaviors in recent years were correlated with the rapid scale-up of harm reduction programs in China from 2006 to 2011. For example, needle sharing behavior among current IDUs decreased significantly over this period, an effect which has a significant correlation with the expansion in coverage of MMT. Our results, which associate the positive influence of harm reduction programs with decreased dangerous drug use-related behaviors, are supported by past research, including several small studies which describe the successes of MMT and NEP as harm reduction interventions [19, 32]. Larger studies have variously reported a significant decrease in both high-risk sexual anddrug use behavior following MMT enrollment in Yunnan [14,15,33, 34].

DUs already enrolled in MMT are excluded from sentinel surveys unless they have at least one positive urine opiate screen result in the three months prior to the survey. This sampling criterion limited our analysis on the effect of MMT on DU behaviors. However, we did find that a smaller proportion of DUs who had ever received MMT services were current IDUs, compared to DUs who had never received MMT services. Some international studies have also found similar trends and changes, where MMT and NEP not only significantly reduced drug use-related behaviors, but also decreased HIV prevalence in Vietnam, Iran, and other countries [35-37]. In addition to the rapid scale-up of harm reduction programs in China, the Chinese government has also adopted more effective policies and cooperative measures targeting drug abuse problems, such as the Cross-Border Project, which was implemented in both northern Vietnam and southern China [38]. Legislation concerning compulsory rehabilitation centers has also changed since 2011, which may influence the drug use-related behaviors of drug users.

In order to prolong the life expectancy of AIDS patients living in rural regions of China, the Chinese government initiated the national free antiretroviral therapy (ART) program in 2002 [39]. Over 80,000 patients had received ART from 2002 to the end of 2009, and the free ART program had already expanded to 28 provinces of China by the end of 2005 [39, 40]. Earlier initiation of ART and increased treatment coverage can significantly reduce the mortality rate of HIV-infected people, but IDUs in China were less likely to receive ART compared with those infected with HIV through sexual behavior and plasma donation [41]. Although some studies indicate that ART may contribute to a reduction in risk behaviors associated with HIV transmission [42], and help HIV-infected people perceive the importance of safer practices [43], studies indicating a valid relationship between the free ART program and change in risk behaviors among DUs in China could not be found. Nonetheless, the combined influence of MMT, NEP, ART, and other systematic interventions on reducing risk behaviors among DUs should not be ignored.

Finally, we found a decreasing trend in HIV prevalence among DUs. Although the rapid scale-up of sentinel sites over the same time period and the limitations inherent in non-probability sampling methods reduced the representativeness of our finding, we also examined data from the seven sentinel sites that existed and actively collected annual survey data in each consecutive year during the time period we investigated. These data confirmed the decreasing trend of HIV prevalence among DUs. The observed decline in DU HIV prevalence may be due in part to a decline in the population of infected DUs and a low rate of new infections among this population [34]. Although the coverage of China's national ART program expanded greatly after 2003, the high degree of late diagnosis of HIV infection, co-infection with multiple viral strains, serious comorbidities such as HCV infection, and increasing drug resistance, gave rise to increasing numbers of AIDS patients [44] and disproportionately high HIV/AIDS-related mortality among DUs [45]. Government epidemic estimation efforts reported new infections among DUs were less than 8,000, yet deaths among DUs were more than 9,000 in 2011 [3]. Another potential reason for the decrease in HIV prevalence may be refusal to participate in the sentinel surveys and/or avoidance of testing among DUs. A recent study reported a difference in HIV prevalence among DUs responding to sentinel surveillance surveys and DUs in the broader community [46].

Our study has some limitations. As an observational study, we described trends and identified correlations, but were unable to examine causal relationships. Furthermore, sentinel surveillance data are based on a stratified snowball sampling method and thus may not be representative of the broader DU population in China.

In summary, while the HIV epidemic among DUs in China has expanded over the past two decades, it is still highly concentrated in five provinces. HIV prevalence and high risk behavior among IDU have declined and might be correlated with the scale-up of national harm reduction efforts. However, the recent rapid increase in the use of “nightclub drugs” presents a new challenge for China's Ministries of Public Security and Health in their joint effort to curb both drug use and the HIV epidemic.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Keming Rou and her team for assisting in providing information on harm reduction, and thank all provincial AIDS directors and their colleagues for collecting data for the HIV/AIDS case reporting system and for the HIV sentinel surveillance system.

Funding: This study was supported by the Chinese Government HIV/AIDS Program (131-11-0001-0501) and by the Fogarty International Center and the National Institute on Drug Abuse at the US National Institutes of Health (China ICOHRTA2, Grant # U2RTW006918). Funding organizations had no role in the development of study design, collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, or in the final decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

Declaration of interests: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Wang L, Zheng XW. Epidemiologic study on HIV infection among injecting drug users and former plasma donors. Chin J Epidemiol. 2003;24:1057–9. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saidel TJ, Jarlais DD, Peerapatanapokin W, Dorabjee J, Singh S, Brown T. Potential impact of HIV among IDU on heterosexual transmission in Asian settings: scenarios from the Asian Epidemic Model. Int J Drug Policy. 2003;14:63–74. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ministry of Health, People's Republic of China, Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS, World Health Organization. 2011 Estimates for the HIV/AIDS Epidemic in China. Beijing, China: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang Y, Qu S, Qin Q, Wang L, Li D, Gao X, et al. The analysis and evaluation of quality of the HIV/AIDS data before and after their integration into the web based case report system in China. Chin J AIDS STD. 2008;14:127–9. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sun X, Wang N, Li D, Zheng X, Qu S, Wang L, et al. The development of HIV/AIDS surveillance in China. AIDS. 2007;21:s33–8. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000304694.54884.06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization, Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. Guidelines for second generation HIV surveillance. Geneva, Switzerland: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li DM, Wang L, Wang LY, Wang L, Gao X, Qin QQ, et al. The history and actuality of HIV sentinel surveillance system in China. Chin J Prev Med. 2008;42:922–5. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lin W, Sanny C, Nicole S, Chen ZD, Keith S, Jesus GC, Marc B. Is the HIV sentinel surveillance system adequate in China? Findings from an evaluation of the national HIV sentinel surveillance system. Western Pacific Surveillance and Response. 2012;3(4):61–68. doi: 10.5365/WPSAR.2012.3.3.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu ZY, Wang Y, Mao YR, Sullivan SG, Juniper N, Bulterys M. The integration of multiple HIV/AIDS projects into a coordinated national programme in China. Bull World Health Organ. 2011;89:227–33. doi: 10.2471/BLT.10.082552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sun XH, Lu F, Wu ZY, Poundstone K, Zeng G, et al. Evolution of information-driven HIV/AIDS policies in China. Int J Epidemiol. 2010;39:ii4–13. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyq217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li JH, Ha TH, Zhang CM, Liu HJ. The Chinese government's response to drug use and HIV/AIDS: a review of policies and programs. Harm Reduct J. 2010;7:4–9. doi: 10.1186/1477-7517-7-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yin W, Hao Y, Sun X, Gong X, Li F, Li J, et al. Scaling up the national methadone maintenance treatment program in China: achievements and challenges. Int J Epidemiol. 2010;39:ii29–37. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyq210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yap L, Wu ZY, Liu W, Ming ZQ, Liang SL. A rapid assessment and its implications for a needle social marketing intervention among injecting drug user in China. Int J Drug Policy. 2002;13:57–68. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wu Z, Luo W, Sullivan SG, Rou K, Lin P, Liu W, Ming Z. Evaluation of a needle social marketing strategy to control HIV among injecting drug users in China. AIDS. 2007;21:S115–22. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000304706.79541.ef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lin P, Fan ZF, Yang F, Wu ZY, Wang Y, Liu YY, et al. Evaluation of a pilot study on needle and syringe exchange program among injecting drug users in a community in Guangdong, China. Chin J Prev Med. 2004;38:305–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ministry of Health, People's Republic of China, Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS, World Health Organization. 2005 Update on the HIV/AIDS Epidemic and Response in China. Beijing, China: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 17.State Council AIDS Working Committee Office UN Theme Group on AIDS in China. A joint assessment of HIV/AIDS prevention, treatment and care in China (2007) Beijing, China: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sullivan SG, Wu ZY. Rapid scale up of harm reduction in China. Int J Drug Policy. 2007;18:118–28. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2006.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang L, Yap L, Zhuang X, Wu ZY, Wilson DP. Needle and syringe program in Yunnan, China yield health and financial return. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:250. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wu ZY, Sullivan SG, Wang Y, Rotheram-Borus MJ, Detels R. Evolution of China's response to HIV/AIDS. Lancet. 2007;369:679–90. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60315-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.National Center for AIDS/STD Control and Prevention, Chinese Center for Diseases Control and Prevention. Guideline for HIV&STD Sentinel Surveillance in China (2012) Beijing, China: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 22.National Center for AIDS/STD Control and Prevention, Chinese Center for Diseases Control and Prevention. Guideline for HIV&STD Sentinel Surveillance in China (2009) Beijing: National Center for AIDS/STD Control and Prevention, Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Department of Disease Control, Minister of Health, China, National Center for AIDS Prevention and Control, Group of National HIV Sentinel Surveillance. National sentinel surveillance of HIV infection in China from 1995 to 1998. Chin J Epidemiol. 2000;21:7–9. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang L, Wang L, Ding Z, Yan R, Li D, Guo W, et al. HIV prevalence among population at risk, using sentinel surveillance data from 1995-2009 in China. Chin J Epidemiol. 2011;32:20–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Beyrer C, Razak MH, Lisam K, Chen J, Lui W, Yu XF. Overland heroin trafficking routes and HIV-1 spread in south and south-east Asia. AIDS. 2000;14:75–83. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200001070-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kretzschmar M, Zhang W, Mikolajczyk RT, Wang L, Sun X, Kraemer A, et al. Regional differences in HIV prevalence among drug users in China: potential for future spread of HIV? BMC Infect Dis. 2008;8:108. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-8-108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lu L, Jia MH, Zhang XD, Luo HB, Ma YL, Fu LR, et al. Analysis for epidemic trend of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome in Yunnan Province of China. Chin J Prev Med. 2004;38:309–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang L, Ma YL, Luo HB, Jia MH, Yang CJ, Wang MJ, et al. A dynamic analysis on incidence and trend of HIV-1 epidemics among intravenous drug users, attendants at the STD clinics and pregnant women in Yunnan province, China. Chin J Epidemiol. 2008;29:1204–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Duan S, Guo HY, Pang L, Yuan JH, Jia MH, Xiang LF, et al. Analysis of the epidemiologic patterns of HIV transmission in Dehong prefecture, Yunnan province. Chin J Prev Med. 2008;42:866–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Panda S, Chatterjee A, Bhattacharya SK, Manna B, Singh PN, Sarkar S, et al. Transmission of HIV from injecting drug users to their wives in India. Int J STD AIDS. 2000;11:468–73. doi: 10.1258/0956462001916137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ahmad S, Mehmood J, Awan AB, Zafar ST, Khoshnood K, Khan AA. Female spouses of injection drug users in Pakistan: a bridge population of the HIV epidemic? East Mediterr Health J. 2011;17:271–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cui Y, Liau A, Wu ZY. An overview of the history of epidemic of and response to HIV/AIDS in China: achievements and challenges. Chin Med J (Engl) 2009;122:2251–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhao L, Holzemer WL, Johnson M, Tulsky JP, Rose CD. HIV infection as a predictor of methadone maintenance outcomes in Chinese injection drug users. AIDS Care. 2012;24:195–203. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2011.596520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Duan S, Yang YC, Han J, Yang SS, Yang YB, Long YC, et al. Study on incidence of HIV infection among heroin addicts receiving methadone maintenance treatment in Dehong prefecture, Yunnan province. Chin J Epidemiol. 2011;32:1227–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Des Jarlais DC, Feelemyer JP, Modi SN, et al. High coverage needle/syringe programs for people who inject drugs in low and middle income countries: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2013;13(1):53. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nguyen T, Nguyen LT, Pham MD, et al. Methadone maintenance therapy in Vietnam: an overview and scaling-up plan. Advances in Preventive Medicine. 2012 doi: 10.1155/2012/732484. Article ID 732484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Heidari AR, Mirahmadizadeh AR, Keshtkaran A, et al. Changes in Unprotected Sexual Behavior and Shared Syringe Use Among Addicts Referring to Methadone Maintenance Treatment (MMT) Centers Affiliated to Shiraz University of Medical Sciences in Shiraz, Iran: An Uncontrolled Interventional Study. Journal of School of Public Health and Institute of Public Health Research. 2011;9(1):67–76. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hammett TM, Des Jarlais DC, Kling R, et al. Controlling HIV epidemics among injection drug users: eight years of cross-border HIV prevention interventions in Vietnam and China. PloS One. 2012;7(8):e43141. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0043141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang FJ, Jennifer P, Lan Y, et al. Current progress of China's free ART program. Cell Research. 2005;15(11):877–882. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7290362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wu Z, Wang Y, Detels R, et al. China AIDS policy implementation: reversing the HIV/AIDS epidemic by 2015. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2010;39(2):i1–i3. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyq220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bunnell R, Ekwaru JP, Solberg P, et al. Changes in sexual behavior and risk of HIV transmission after antiretroviral therapy and prevention interventions in rural Uganda. Aids. 2006;20(1):85–92. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000196566.40702.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kravcik S, Victor G, Houston S, et al. Effect of antiretroviral therapy and viral load on the perceived risk of HIV transmission and the need for safer sexual practices. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 1998;19(2):124–129. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199810010-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang F, Dou Z, Ma Y, et al. Effect of earlier initiation of antiretroviral treatment and increased treatment coverage on HIV-related mortality in China: a national observational cohort study. The Lancet infectious diseases. 2011;11(7):516–524. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70097-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang FJ, Haberer JE, Wang Y, Zhao Y, Ma Y, Zhao DC, et al. The Chinese free antiretroviral treatment program: challenges and responses. AIDS. 2007;21:S143–8. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000304710.10036.2b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Duan S, Zhang L, Xiang LF, Duan YJ, Yang ZJ, Jia MH, et al. Natural history of HIV infections among injecting drug users in Dehong prefecture, Yunnan province. Chin J Epidemiol. 2010;31(7):763–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lin P, Wang M, Li Y, Zhang Q, Yang F, Zhao J. Detoxification center-based sampling missed a subgroup of higher risk drug users, a case from Guangdong, China. PLoS One. 2012;7(4):e35189. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]