Abstract

Black women are traditionally underserved in all aspects of cancer care. This disparity is particularly evident in the area of psychosocial interventions where there are few programs designed to specifically meet the needs of Black breast cancer survivors. Cognitive-behavioral stress management intervention (CBSM) has been shown to facilitate adjustment to cancer. Recently, this intervention model has been adapted for Black women who have recently completed treatment for breast cancer. We outline the components of the CBSM intervention, the steps we took to adapt the intervention to meet the needs of Black women (Project CARE) and discuss the preliminary findings regarding acceptability and retention of participants in this novel study.

Keywords: health psychology, content, multiculturalism, race/ethnicity, dimensions of diversity

Black women are traditionally underserved in all aspects of cancer care (National Cancer Institute Center to Reduce Cancer Health Disparities, 2007). Despite lower incidence of disease, Black women have a higher mortality rate than other racial and ethnic groups (Carey et al., 2006; Lannin, Mathews, Mitchell, & Swanson, 2002; Reynolds et al., 1994, 2000). In addition, Black women with breast cancer are more likely to be diagnosed with later stage disease, imparting a poorer prognosis and greater need of social support (Coates et al., 1992; Eley et al., 1994; Lannin et al., 1998). Later stage disease also requires more invasive treatments to eradicate the cancer, resulting in diminished quality of life and more physical discomfort (Aziz & Rowland, 2002). Whether Black Americans experience poorer cancer-related quality of life is a controversial topic in a growing body of literature; the mixed findings are most likely the result of differences in sample composition with regard to income, neighborhood characteristics, sociodemographic factors, stage of disease, and other medical and treatment variables (Ashing-Giwa, Ganz & Peterson, 1999; Ashing-Giwa & Lim, 2001; Giedzinska, Meyerowitz, Ganz, & Rowland, 2004; Hao et al., 2011; Janz et al., 2009; Matthews, Tejada, Johnson, Berbaum, & Manfredi, 2012; Paskett et al., 2008). In a notable study with a very large representative sample of survivors that used data from the Women’s Health Initiative,Paskett et al. (2008) reported significant disparities for health-related quality of life between African American breast cancer survivors and White survivors in the areas of physical functioning, role limitations due to emotional health, and general health but not in other patient-reported outcomes such as emotional wellbeing, sleep disturbance, and depression. However, there is a robust influence of socioeconomic status on quality of life, such that women of lower socioeconomic status perceive poorer quality of life (Ashing-Giwa & Ganz, 1997; Beder, 1995; Ell & Nishimoto, 1989), and regrettably, this factor affects the majority of Black breast cancer survivors in the United States.

In this article, we describe the development and preliminary testing of an evidence-based psychosocial intervention for Black breast cancer survivors, Project CARE (Cope, Adapt, Renew, Empower). The intervention was derived from an empirically validated behavioral medicine program based on cognitive-behavioral theory (i.e., cognitive-behavioral stress management [CBSM]; Antoni, 2003) and was then adapted to be sensitive to cultural and social norms for Black women. We outline the components of the overall CBSM intervention and the psychosocial needs of Black breast cancer survivors and comment on the cultural adaptation of the intervention. Finally, we present some preliminary findings regarding acceptability and retention of participants in this novel study. The development of this program is presented here to highlight the important role that counseling psychologists can play in assisting women who have undergone treatment for breast cancer and to highlight important factors to consider when adapting evidence-based interventions to Black clients with breast cancer.

Psychosocial Interventions for Women with Breast Cancer

The 10-week Cognitive-behavioral stress management (CBSM) intervention approaches stress management from a multifocal view: cognitive-behavioral skills and relaxation skills training in a group environment setting. The manual of the initial psychosocial intervention study for women with breast cancer is available elsewhere (Antoni, 2003); a summary is presented here for convenience. Each CBSM session is divided into two parts: a relaxation skills component and a CBSM component. Relaxation techniques include progressive muscle relaxation, visual imagery, deep breathing, and meditation techniques. The didactic and experiential components of CBSM have been specifically designed to teach strategies to reduce arousal and anxiety, change negative stressor appraisals (e.g., cognitive restructuring), provide coping skills training (e.g., enhancing adaptive coping skills, accurate matching of problem-focused or emotion-focused strategies on the basis of the controllability of the stressor, acceptance of uncontrollable stressors), interpersonal skills training (e.g., communication skills, anger management and assertiveness training), and enhance social networks (e.g., identifying tangible and emotional sources of support, spousal or partner communication and support) (Antoni, Lechner, et al., 2006). The facilitator encourages emotional expression and provides the opportunity to experience social support, replaces feelings of doubt with a sense of confidence, and discourages avoidance while encouraging reframing and acceptance as coping responses.

The CBSM intervention was developed within Miami’s multicultural population and thus needed to be responsive to the needs of women of many cultural and economic backgrounds. The CBSM intervention has been validated in individuals with various medical conditions, including cancer (Antoni et al., 1991, 2001, 2008; Antoni, Lechner, et al., 2006; Antoni, Wimberly, et al., 2006; Lopez et al., 2011; Lutgendorf et al., 1997; Penedo et al., 2004). These studies show that stress management interventions have been highly effective in enhancing adaptation to illness. However, one of the primary limitations of this work in our breast cancer populations was that the samples consisted of mostly middle-class, non-Hispanic White women with breast cancer, thus limiting generalizability to other women with breast cancer. Our preliminary, unpublished evidence showed that CBSM intervention was equally as effective in the small percentage of the sample from minority backgrounds as it was in White women. Thus, the next logical step was to test whether the intervention imparted benefits to a sample of community-dwelling minority women.

Despite compelling evidence that psychosocial interventions are efficacious in attenuating difficulties in aspects of quality of life in cancer survivors (for meta-analyses, see Meyer & Mark, 1995; Osborn, Demoncada, & Feuerstein, 2006; Rehse & Pukrop, 2003; Tatrow & Montgomery, 2006), there is little racial and ethnic diversity in most samples of psychosocial intervention trials to date. Reviews of intervention research with cancer patients reveal that psychosocial interventions reduce emotional distress, improve quality of life, enhance coping, foster social support, and encourage stress management (Andersen, 1992; Antoni, Lechner, et al., 2006; Classen et al., 2001; Luebbert, Dahme, & Hasenbring, 2001; Trijsburg, van Knippenberg, & Rijpma, 1992). In one of the few intervention studies designed to evaluate an intervention for Black women,Taylor et al. (2003) found that a psychoeducational group-based intervention was efficacious for low-income Black women with nonmetastatic breast cancer. The research group highlighted the need for culturally appropriate interventions that address the specific concerns of minority women with breast cancer.

Our targeted intervention helps women enhance social support, coping, and relaxation strategies during an important milestone: the end of cancer treatment. This phase is a particularly troubling time for many women, who may think “Now what?” and may feel abandoned by the formal health care system when they are no longer receiving active curative treatment (Holland & Reznik, 2005). In fact, the end of breast cancer treatment has been cited as a time of great stress and distress, characterized by ongoing side effects from treatment, anxiety about recurrence, feeling misunderstood by social support networks (“Treatment is over, why aren’t you happy?”), uncertainty about how to develop strategies for healthy living posttreatment in the face of conflicting information, and feeling that one has been profoundly changed by the challenging life experience (Hewitt, Greenfield, & Stovall, 2005).

Needs of Black Breast Cancer Survivors

To inform our adaptation of the intervention, we started with an extensive literature review. We found that low-income Black women may have some unique concerns, in addition to the issues that plague breast cancer survivors in general (Ashing-Giwa, Padilla, Tejero, & Kim, 2004; Taylor et al., 2003). Ashing-Giwa et al. (2004) suggested that race and ethnicity can play an important role in a woman’s personal experience of breast cancer. This literature provided several clues about content areas that should be covered in interventions for Black breast cancer survivors. Black women have specific concerns about feeling attractive after breast surgery, the possibility of forming keloid scars, the lack of prosthetic devices that match skin tone, how to live with a chronic illness, and the erosion of social support (Ashing-Giwa et al., 2004; Spencer et al., 1999; Wilmoth & Sanders, 2001). In fact, social support during the breast cancer experience may be of great importance. In a 2003 study of Black and White women with breast cancer, lower perceived emotional support at diagnosis predicted higher risk for death over a 10-year follow-up period (Soler-Vila, Kasl, & Jones, 2003). Such findings suggest that Black women with breast cancer could benefit greatly from supportive interventions that teach them skills to maintain and enhance their social support networks. By addressing the aforementioned concerns in a group context, women can also support one another, validate their experiences and their concerns, and reduce feelings of isolation.

Tailoring of CBSM Intervention for Minority Women

All of this information led us to focus on two categories of adaptation to the treatment manual: the content of the material and the process of the intervention.

Tailoring the Content of CBSM Modules

Changes were made to specific didactic portions to increase salience to minority women. The in-session examples, language, scenarios, and role-plays were adapted to fit Black preferences without sacrificing the main tenets of the issue being discussed. Three specific examples of adaptation are presented here for reference; however, nearly every page of the more than 200-page treatment manual was edited to make the content culturally relevant to the Black subgroups in the study.

Coping skills

Black women report using religious and spiritual coping strategies more so than their White counterparts (Culver, Arena, Antoni, & Carver, 2012), as well as coping by suppressing emotions, wishful thinking, and positive reappraisal (Reynolds et al., 2000). Because there may be women in the group who use these strategies to the exclusion of all other coping strategies, it is useful to emphasize the importance of having a wide coping repertoire. Religious coping and the beliefs associated with this coping strategy coincide with some of the messages of the CBSM intervention, such as respecting the use of religious behaviors (e.g., praying) as a legitimate coping strategy and matching specific coping strategies to the controllability of stressors. In this CBSM intervention, we use the serenity prayer as an example of matching coping strategies to the uncontrollable and controllable aspects of a given situation.

Social support (informational, tangible, and emotional)

Because churches are a common source of support for Black women (McRae, Carey, & Anderson-Scott, 1998), the role of a higher power is highlighted as a resource in a manner that was not used in previous versions of the intervention because it was not culturally relevant. In addition, Black women may be more likely than Caucasians to turn to family members and/or spouses for medical information and decision making (Sanchez-Hucles, 2000), so the intervention works with women to find ways to elicit support without alienating others. Minority women tend to be given less detail about their disease and medical options and may therefore have a greater need for informational support (Moore, 2001). Project CARE not only provides information but coaches women on ways to enhance the doctor-patient relationship and how to optimally communicate with medical staff members. Black women may keep their cancer diagnoses to themselves and their immediate families, limiting opportunities for social support (Wilmoth & Sanders, 2001). We explicitly recognize this fact in the sessions, providing the opportunity to process this cultural phenomenon. The intervention groups then provide opportunities for support from other cancer survivors who are familiar with similar cultural taboos. The interventionist guides participants on methods to elicit and use optimal social support from family and friends. Our previous nonintervention work showed that women with breast cancer often experience an erosion of social support after treatment, during a time when they need it most (Alferi, Carver, Antoni, Weiss, & Durán, 2001), again highlighting the need for encouragement in reaching out for social support. Also, Black women report a desire to talk about intimate relationships and report issues related to sexual attractiveness after a breast cancer diagnosis (Taylor et al., 2003) but also note the scarcity of open discussions of sexuality, even among close female friends (Wilmoth & Sanders, 2001). CBSM intervention aids in encouraging quality of life specifically as it relates to sexuality for women with breast cancer (Wimberly, Carver, Laurenceau, Harris, & Antoni, 2005).

Relaxation and imagery exercises

Relaxation skills exercises may be foreign to low-income Black women. We deemphasize techniques for which group members may not have prior exposure, knowledge, or experience and accentuate more familiar techniques that do not require extensive practice. To this end, the intervention focuses on deep breathing techniques and guided imagery techniques, which were well received in previous studies. Because progressive muscle relaxation is an unfamiliar skill to most women and is a complex, learned skill requiring practice, we reduced its complexity by introducing fewer muscle groups. Meditation is presented as a beneficial health behavior devoid of religious associations (Speca, Carlson, Goodey, & Angen, 2000) for those women who might see meditation as a conflict with their religious beliefs.

Tailoring the Process of CBSM Modules

The group-based exercises in our intervention are designed to facilitate feelings of trust, safety, and empowerment. Developing trust is important in any group but may be particularly relevant for Black Americans, who have a history of marginalization or exclusion by institutions, as well as mistreatment by researchers, the U.S. Public Health Service Syphilis Study in Tuskegee being one of the most notorious examples, though there are others (Corbie-Smith, 1999; Gamble, 1997). Because the groups are held in community (rather than academic) locations, and because members of churches and other community organizations have recommended the program, women report that they feel more comfortable addressing concerns in the group setting. Within the Black community, a stigma still surrounds breast cancer diagnosis and treatment, and confidentiality remains a major concern to Black women (Sisters Network Inc., 2007). Group interventionists encourage participants to explore concerns and spend more time on this topic than in past studies. Other important factors that guided our tailoring of the intervention are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Examples of Cultural Factors That Were Considered When Adapting the Cognitive-Behavioral Stress Management Intervention for Black Breast Cancer Survivors

| Cultural Factor |

Culture-Specific Definition |

Intervention Adaptation |

|---|---|---|

| Interpersonal orientation | The group or collective is emphasized over the individual. | The concept of sisterhood is woven throughout the intervention as a means of creating lasting bonds and empowering women to make healthy choices for themselves. |

| Spirituality and religiosity | There exists a force greater than oneself, and faith in God is an important aspect of daily life. | There are explicit discussions about the role of spirituality and religion in the intervention, and women are encouraged to view religiosity and spirituality as naturally derived strengths to bolster them during challenging times. |

| Harmony | All aspects of one’s life are connected and must be balanced. | Guided by the notion that all individuals are embedded in, and affected by, larger social and cultural spheres of influence, stress is presented as a facet of life that must be balanced. Too much stress creates tension, whereas too little stress may result in a situation in which a person feels unmotivated. Stress can affect individuals internally and externally, which has an impact on larger social units. |

| Time as a social phenomenon | Time is not an entity in itself but is created as a consequence of interpersonal interaction. | Groups do not begin on time. |

| Negativity to positivity | Value is placed on being able to turn bad situation into something good. | Women are encouraged to find balance between viewing situations as inherently “good” or “bad” but that all events are an opportunity for growth and empowerment. |

Source: Adapted from Belgrave, Brome, and Hampton (2000).

Methods

Recruitment

Recruitment took place through a variety of different venues, including community-based breast cancer programs, local churches of several denominations, community centers, health fairs, hospitals, private physicians within the community, public service announcements in local media that cater to the Black community in the South Florida area, and cultural activities. The project was also promoted through culturally appropriate communication channels, such as local radio programs and print media.

Women were eligible to participate in Project CARE if they met the following criteria: age 21 years or older, English speaking, self-identify as Black (African American, African, Caribbean Black, Black Hispanic), have been diagnosed with breast cancer (any stage of disease, any type of breast cancer), have received at least one type of traditional medical treatment for breast cancer (i.e., surgery, chemotherapy, radiation therapy) and completed treatment within 6 months of enrollment, have no previous history of cancer, have a self-reported life expectancy of 12 months or longer, have endorsed moderate stress or distress (a score of 4 or greater on a scale of 0 to 10), have had no inpatient psychiatric treatment for severe mental illness (e.g., psychosis) within the past year, have no active suicidality, and have no substance dependence within the past year.

Participants were between 27 and 77 years old (M = 49.45 years, SD = 8.82 years). Approximately half of the participants were employed full-time or part-time (49%), while 9% were retired, 18% were on disability, and 24% were unemployed. The average education level was about 13 years (range = 9 to 18 years), and the average income was about $31,000 (range = $0 to $130,000). One hundred percent of participants reported affiliation with Christian denominations, although there was variance in attendance at religious services and study groups (from not at all to several times a week). Table 2 presents the sample characteristics classified by intervention condition.

Table 2.

Demographics of Project CARE Participants

| Variable | EE Condition | CBSM Condition |

F | χ2 | df | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), M (SD) | 50.32 (10.06) | 48.88 (7.80) | 0.35 | 1, 53 | >.50 | |

| Years of education, M (SD) | 13.14 (1.70) | 13.33 (2.36) | 0.48 | 1, 52 | >.70 | |

| Income (thousands of dollars annually), M (SD) | 28.23 (25.20) | 32.79 (28.02) | 0.38 | 1, 53 | >.50 | |

| Months since breast cancer diagnosis, M (SD) | 13.41 (5.51) | 14.39 (6.74) | 0.32 | 1,53 | >.50 | |

| Work status | 0.63 | 3 | >.80 | |||

| Unemployed | 6 (27%) | 7 (21%) | ||||

| Employed | 11 (50%) | 16 (48%) | ||||

| On disability/leave | 3 (14%) | 7 (21%) | ||||

| Retired | 2 (9%) | 3 (9%) | ||||

| Marital status | 1.13 | 4 | >.90 | |||

| Single, never married | 5 (23%) | 6 (18%) | ||||

| Married/partnered | 7 (32%) | 10 (30%) | ||||

| Separated | 4 (18%) | 4 (12%) | ||||

| Divorced | 5 (23%) | 10 (30%) | ||||

| Widowed | 1 (4%) | 3 (9%) | ||||

| Have children | 20 (91%) | 28 (85%) | 0.44 | 1 | >.50 | |

| Breast cancer stage | 5.35 | 4 | >.20 | |||

| 0 | 3 (14%) | 2 (6%) | ||||

| I | 8 (36%) | 5 (15%) | ||||

| II | 7 (32%) | 16 (48%) | ||||

| III | 4 (18%) | 9 (27%) | ||||

| IV | 0 (0%) | 1 (3%) | ||||

| Underwent surgery | 21 (96%) | 31 (94%) | 0.06 | 1 | >.80 | |

| Received chemotherapy | 15 (71%) | 29 (88%) | 2.30 | 1 | >.10 | |

| Received radiation | 16 (73%) | 23 (70%) | 0.06 | 1 | >.80 | |

| Received hormonal therapy | 12 (57%) | 19 (58%) | 0.00 | 1 | >.90 | |

| Received targeted therapies | 3 (15%) | 9 (31%) | 1.65 | 1 | .20 |

Note: CARE = Cope, Adapt, Renew, Empower; CBSM = cognitive-behavioral stress management; EE = enhanced breast cancer education.

Control Condition: Enhanced Breast Cancer Education

In this article, we report the adaptation of the CBSM intervention to meet the needs of Black women with breast cancer. As a randomized controlled trial, the control condition was also made salient for the needs of survivors by using a time-matched psychoeducation condition. This condition used a classroom setting and structured PowerPoint slides to present information on breast cancer incidence, control, and treatment, as well as healthy lifestyle information. Because of the study team’s ethical obligation to provide a relevant and culturally sensitive group for women randomized to control, the psychoeducation condition was specifically designed to be a pleasant and enriching experience. The development of the enhanced education program is discussed in detail elsewhere (Lechner, Dumercy, Ennis-Whitehead, Phillips, & Vargas, 2008).

Procedure

All study procedures were approved and monitored by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Miami. Participants were self-referred and did not require medical provider referral to enroll. Screening for eligibility and in-person assessments were conducted by a Black female assessor who was supervised by a licensed clinical psychologist. Assessments took place in the participant’s home or a location of her choice (e.g., a private room in a community center). Given that we expected a wide range of literacy and educational levels within the sample, all of the scales were given in interview format, with printed prompts for each of the response sets that were formatted in a manner to increase understanding. Assessors were trained in how to reword items that were unclear without influencing the participant’s responses. After completing the interviews, participants were paid for their participation.

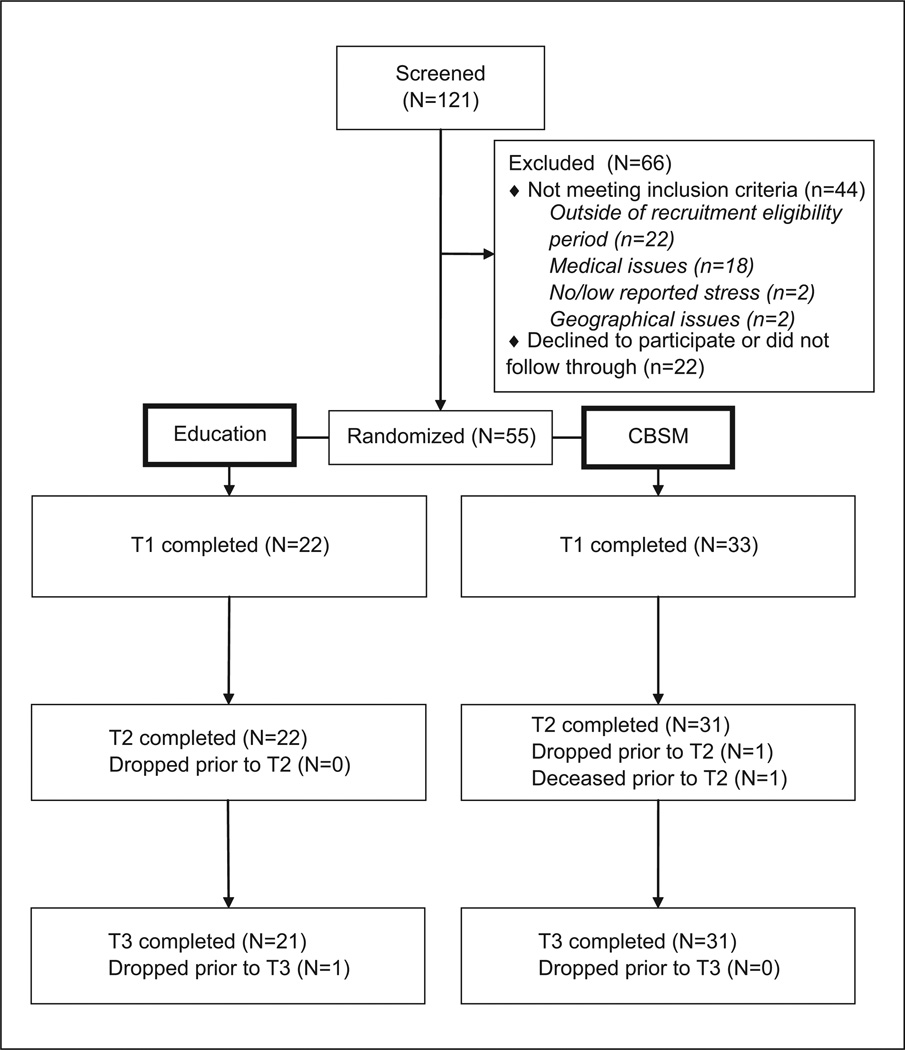

Participants (overall n = 55 at baseline) were randomized into the 10-week group CBSM intervention (n = 33) or a time-matched group psychoeducational program (n = 22). The Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) flowchart is depicted in Figure 1. Participants completed a battery of assessments at three time points: at study entry and prior to beginning the CBSM or psychoeducation groups (Time 1), at the conclusion of the CBSM or psychoeducational groups (Time 2), and 6 months after the conclusion of the groups (Time 3, not analyzed for the current article). Of interest here, a series of items were administered at the end of the second assessment battery (i.e., after the completion of the CBSM or psychoeducational group) to measure the acceptability of the CBSM and psychoeducational programs, the group leaders, the assessments and surveys, and the Project CARE staff. While the other psychosocial questionnaires were administered via structured interview and entered electronically by project assessors, the acceptability items were completed directly by the participant on a laptop computer. Participants were informed that these responses would not be reviewed by the interviewer and would be kept confidential to reduce the possibility of social desirability influences.

Figure 1. Flow of Project CARE Participants From Screening Through Follow Up.

Note: CARE = Cope, Adapt, Renew, Empower; CBSM = cognitive-behavioral stress management; T = time.

Measures

Retention percentages at Times 2 and 3 were calculated as the number of women who completed each of these assessments divided by the number of women who were randomized and completed the baseline assessment (Time 1).

A 14-item scale assessed the acceptability of the CBSM and psychoeducational programs, the group leader, the assessments and surveys, and the Project CARE staff. Participants were asked to rate their levels of agreement with various statements on a 4-point scale ranging from completely agree to completely disagree. See Table 3 for item content. Participants in both the experimental and control conditions completed this questionnaire. The acceptability questions are administered at the second assessment time point (the first postintervention time point). Because many of acceptability items are related to general study participation, such as scheduling appointments, these questions are administered to everyone who completes the Time 2 assessment, not just those who attended the intervention groups. Women who did not attend the study sessions were not forced to decline the items that related to the group, and thus, these women who did not attend study intervention sessions provided data regarding study acceptability. See Figure 1 for the CONSORT flowchart of participants in the study.

Table 3.

Frequencies and Percentages for Intervention Acceptability Questions Administered After the Conclusion of the 10-Week Program

| Item | Rating | All Participants (n = 52) |

EE Condition (n = 21)a |

CBSM Condition (n = 31) |

Attended at Least 1 of the 10 Sessions (n = 48) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| This program was a good use of my time | Completely agree | 45 (86%) | 17 (81%) | 28 (90%) | 43 (90%) |

| Agree | 5 (10%) | 3 (14%) | 2 (6%) | 4 (8%) | |

| Disagree | 1 (2%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (3%) | 1 (2%) | |

| Completely disagree | 1 (2%) | 1 (5%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| This program was helpful | Completely agree | 44 (85%) | 17 (81%) | 27 (87%) | 42 (88%) |

| Agree | 7 (13%) | 3 (14%) | 4 (13%) | 6 (12%) | |

| Disagree | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Completely disagree | 1 (2%) | 1 (5%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| This program will be helpful in my daily life | Completely agree | 41(80%) | 15 (71%) | 26 (87%) | 39 (83%) |

| Agree | 9 (18%) | 5 (24%) | 4 (13%) | 8 (17%) | |

| Disagree | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Completely disagree | 1 (2%) | 1 (5%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Declined to answer | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| This program has helped me deal with my breast cancer | Completely agree | 42 (81%) | 15 (71%) | 27 (87%) | 40 (83%) |

| Agree | 7 (13%) | 4 (19%) | 3 (10%) | 7 (15%) | |

| Disagree | 1 (2%) | 1 (5%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Completely disagree | 2 (4%) | 1 (5%) | 1 (3%) | 1 (2%) | |

| I felt comfortable with my group leader | Completely agree | 44 (86%) | 17 (81%) | 27 (90%) | 42 (89%) |

| Agree | 6 (12%) | 3 (14%) | 3 (10%) | 5 (11%) | |

| Disagree | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Completely disagree | 1 (2%) | 1 (5%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Declined to answer | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| The group leader made everyone feel welcome and understood | Completely agree | 47 (92%) | 19 (90%) | 28 (93%) | 45 (96%) |

| Agree | 3 (6%) | 1 (5%) | 2 (7%) | 2 (4%) | |

| Disagree | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Completely disagree | 1 (2%) | 1 (5%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Declined to answer | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| It was easy to participate in the weekly groups | Completely agree | 42 (81%) | 17 (81%) | 25 (81%) | 40 (83%) |

| Agree | 7 (13%) | 3 (14%) | 4 (13%) | 7 (15%) | |

| Disagree | 2 (4%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (6%) | 1 (2%) | |

| Completely disagree | 1 (2%) | 1 (5%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| The staff made it easy to schedule my appointments | Completely agree | 45 (86%) | 18 (86%) | 27 (87%) | 44 (92%) |

| Agree | 5 (10%) | 1 (5%) | 4 (13%) | 4 (8%) | |

| Disagree | 1 (2%) | 1 (5%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Completely disagree | 1 (2%) | 1 (5%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| It was easy to do the surveys and questionnaires | Completely agree | 39 (75%) | 14 (67%) | 25 (81%) | 37 (77%) |

| Agree | 12 (23%) | 6 (29%) | 6 (19%) | 11 (23%) | |

| Disagree | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Completely disagree | 1 (2%) | 1 (5%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| The Participant Workbook was easy to read and understand | Completely agree | 41 (79%) | 16 (76%) | 25 (81%) | 40 (83%) |

| Agree | 9 (17%) | 4 (19%) | 5 (16%) | 7 (15%) | |

| Disagree | 1 (2%) | 1 (5%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Completely disagree | 1 (2%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (3%) | 1 (2%) | |

| The program staff was friendly and helpful | Completely agree | 48 (92%) | 19 (90%) | 29 (94%) | 45 (94%) |

| Agree | 3 (6%) | 1 (5%) | 2 (6%) | 3 (6%) | |

| Disagree | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Completely disagree | 1 (2%) | 1 (5%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Overall, this was a good program | Completely agree | 47 (92%) | 18 (86%) | 29 (97%) | 45 (96%) |

| Agree | 3 (6%) | 2 (10%) | 1 (3%) | 2 (4%) | |

| Disagree | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Completely disagree | 1 (2%) | 1 (5%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Declined to answer | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| This program was applicable to my life experience | Completely agree | 44 (85%) | 15 (71%) | 29 (94%) | 42 (88%) |

| Agree | 6 (12%) | 5 (24%) | 1 (3%) | 5 (10%) | |

| Disagree | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Completely disagree | 2 (4%) | 1 (5%) | 1 (3%) | 1 (2%) | |

| I would recommend this program to other women who have had breast cancer | Completely agree | 47 (90%) | 18 (86%) | 29 (94%) | 45 (94%) |

| Agree | 3 (6%) | 2 (10%) | 1 (3%) | 2 (4%) | |

| Disagree | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Completely disagree | 2 (4%) | 1 (5%) | 1 (3%) | 1 (2%) |

Note: CBSM = cognitive-behavioral stress management; EE = enhanced breast cancer education.

One participant had missing data for this questionnaire.

Intervention Adaptation and Design

Project CARE was designed to test the effects of a relatively brief, culturally informed, psychosocial intervention with a strong evidence base. The project recruits, assesses, and delivers the intervention in the community settings where women obtain most health-related information and health care. Consistent with one of the basic tenets of counseling psychology, the intervention is strength based and focuses on skill building to facilitate personal and interpersonal adaptation over the life span (Corey, 2008). Drawing on the need for wider cultural acceptability and support of this project, as well as principles of community-based participatory research, an aim of Project CARE is to have a seamless collaboration with community organizations that are dedicated to the underserved with a strong community presence.

The literature on adapting an evidence-based intervention to meet the needs of specific cultural groups recommends that researchers focus on aspects of cultural sensitivity (e.g., interdependence among group members, spirituality, the experience of discrimination), ecological validity (which includes language, persons, metaphors, content, concepts, goals, methods, and context to reduce the discrepancy between the psychotherapist’s assumptions and the actual ethnocultural experience of participants; Bernal, Jiménez-Chafey & Domenech Rodríguez, 2009) as well as the unique mechanisms that may influence uptake in a specific group of people (Castro, Barrera, & Holleran Steiker, 2010; Hays, 2009). In this study, we not only adapted the intervention manual but also employed Black psychologists and research associates so that there was a match between participants, group facilitators, and assessors, in addition to mandatory cultural sensitivity training for the entire research team (Griner & Smith, 2006).

The Project CARE CBSM intervention was guided by a conceptual model of culture derived from several theoretical frameworks (e.g., Cross, 1991; Krieger, 2001; Marín & Marín, 1991; Meyerowitz, Richardson, Hudson, & Leedham, 1998; Phinney, 1996; Williams, 1997). These theories conceptualize ethnicity as multidimensional, composed of cultural values and norms, ethnic identity, and social implications of minority status. We relied heavily upon three recommended constructs to make the Project CARE intervention culturally relevant as we adapted the treatment program: culture, ethnic identity, and minority status. Black culture is not a unitary construct and needed to account for a variety of African American cultural values, as well as Black Hispanic and Caribbean Black cultures as well. We focused on several common threads that run through these cultural groups (including respect for others and a flexible orientation to meeting start time) to make the intervention salient to these Black subgroups. Second, although each subgroup maintains its own unique identity, we focused on the commonalities of the experience of being a Black woman living in the United States and the experience of subtle and overt discrimination to strengthen bonds between group members while appreciating and acknowledging such differences among members. Finally, to address issues related to the social implications of minority status, interventionists addressed the confounds of Black race/ethnicity and income. Although being Black does not necessarily imply that one is low income, sadly, this is the case in much of our local area. Statistics show that 28.6% of Black women in Miami-Dade County live below the poverty level, and there is an overall median household income of about $33,000 per year for Black women (U.S. Census Bureau, 2002). South Florida’s large population of Black women may face several challenges in addition to issues related to breast cancer, including poverty, discrimination, inadequate housing, a high proportion of single-parent families, addiction, low educational attainment, and residence in noisy and overcrowded neighborhoods (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2012).

Briefly, the steps taken to adapt the CBSM intervention included a needs assessment, a focus group of members of the target community, a focus group with stakeholders, an iterative process of manual adaptation, pilot testing with a small group of participants, and now a large-scale controlled clinical trial (Barrera & Castro, 2006; Wingood & DiClemente, 2008). In this article, we focus on the preliminary results of the acceptability of the intervention as determined by the pilot group and the first seven intervention waves of the larger clinical trial. The first focus group was composed of Black breast cancer survivors who ranged from 6 months to 5 years after diagnosis. We specifically queried about the cultural sensitivity of specific components of the adapted CBSM intervention and elicited culturally sensitive examples for use in the treatment manual. We asked about their psychosocial needs during specific phases of breast cancer treatment and issues related to survivorship. The focus group provided valuable in-group insights into cultural norms, gender roles, and power differentials that could affect women’s opinion of the intervention. The group revealed information regarding norms of social support networks, highlighted the influence of religious organizations as a common source of support, and outlined the ways in which women turn to extended family members and/or spouses for medical information and decision making. We queried about gaps in knowledge about breast cancer, medical options, and doctor-patient relationships. Participants felt that our program of stress management would be warmly received by their peers and would be meaningful and able to meet the needs of Black breast cancer survivors, and several participants were excited to help us spread the word about the study.

We also conducted a focus group of community stakeholders in addition to our team from the university. This group provided information on recruitment strategies, community organizations and locations, logistics of home visit assessments and intervention locations, and their perceptions of community acceptance of the program. Next, we hired a Black female community consultant who was a licensed psychologist to survey for culturally relevant themes within the intervention. She scrutinized the manual and edited the content of several sections to add relevant examples, role-plays, and descriptions. She detailed the ways in which the flow of the sessions needed to be revised to reflect those values relevant to women of African American and Black Caribbean backgrounds, especially in relation to starting the groups on time and communication patterns.

Retention Strategies

Retention of ethnic/racial minorities in cancer studies is of great concern to psycho-oncology researchers (Sears et al., 2003). Focus group data revealed that it is critical to develop a strong collaborative relationship between participants and members of the research team, and this relationship begins at the moment of first contact between the recruiter and potential participant (Anderson, 2004; Brown, Fouad, Basen-Engquist, & Tortolero-Luna, 2000). Women welcome an atmosphere in which they know that they are making a contribution and that their efforts have the potential to improve other people’s experiences (Needham, 2004). By expressing appreciation verbally and in writing, the research team fosters participants’ desire to remain in the study. Participants also feel valued when they receive newsletters and flyers with useful and pertinent information. Project CARE sends regular updates and information on resources, local events, and breast cancer information. Participants have especially appreciated holiday cards, token gifts such as pens or notepads with study information and contact numbers, and certificates of completion (Needham, 2004).

Interventionist Training

All interventionists participated in a structured training program that was delivered by the first and second authors. This training provides education on the basic concepts in breast cancer biology, epidemiology, treatment, and psychosocial aspects of cancer. The training was also used to increase the multicultural competencies of the therapist. Specifically, we emphasized an awareness of cultural code switching and its use in therapeutic process, the impact of stereotypes held by each group, and the importance of acculturation and Black identity on the individual and group process. Even though interventionists for Project CARE are required to be Black themselves, the expected diversity within our sample necessitated multicultural competence of the interventionists per recommendations of the American Psychological Association (2012b) and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2005). Counseling psychologists are well versed in attending to multicultural issues and social justice factors in community-based settings, which makes counseling psychologists particularly well suited to delivering this type of intervention (Corey, 2008).

Results

The findings presented here reflect preliminary testing of the intervention on the basis of the first 7 waves of the larger clinical trial, which will include a total of 12 waves of assessment and intervention delivery when it is complete.

Acceptability

Table 3 presents acceptability data from (a) all participants (irrespective of assigned group condition), (b) participants in the psychoeducation condition, (c) participants in the CBSM condition, and (d) those who attended at least one group session. Note that the acceptability questionnaire was given to all participants at Time 2, irrespective of attendance (see the “Methods” section). As expected, women are highly satisfied with the program, and participants in both conditions rated the program favorably. Average attendance rates at group sessions, which may be considered an indicator of investment in the program, was 7 out of 10 sessions.

Retention

Project CARE has enjoyed an exceptionally high retention rate (see Figure 1). Participant tracking revealed a 96% retention rate between baseline and the immediate postintervention assessment and a 95% retention rate between baseline and 6-month follow-up. Given the competing demands and hardships facing the sample, attendance rates and retention rates speak to the extremely high satisfaction of participants.

Discussion

Project CARE is the first intervention study of its kind to test a CBSM intervention that was designed specifically for Black breast cancer survivors. In this article, we provide the rationale for the adaptation of an empirically validated psychosocial intervention and the methodology used to create the adapted intervention manual, and we highlight some of the many issues that need to be considered in developing a culturally sensitive targeted treatment for Black breast cancer survivors. Adjustment to breast cancer is affected by many factors, and we capitalized on the potential role of culturally sanctioned behavioral and social responses that might influence a woman’s adaptation to this stressful life event to adapt the intervention.

This type of intervention is especially relevant for counseling psychologists who work with cancer survivors in a variety of settings and venues. Counseling psychologists are attuned to assisting clients with adapting to life circumstances via focusing on strengths and building on the clients’ unique assets (American Psychological Association, 2012a). As readers are well aware, counseling psychology focuses not only on treatment for emotional and physical disorders but also on normal psychological development over the lifespan in diverse groups (Sue & Sue, 2007). The CBSM intervention is consistent with this approach and encourages women to use stress management skills to both manage cancer-related and life stress and enhance social support, increase benefit finding, and improve psychosocial well-being.

Through this formative work, we have learned that the transition from conducting clinical research in academic settings into implementing an evidence-based intervention in community settings is extremely challenging and requires a great deal of flexibility on the part of the research team and community organizations. Future directions for this research program include developing an Internet-based, live videoconference protocol to further disseminate the intervention to groups of isolated Black women who might not have the opportunity to meet with others in a group in their geographical locations.

In sum, CBSM intervention combines psychoeducation with client-centered counseling techniques to enhance each participant’s ability to cope with cancer and its aftermath. Preliminary acceptability findings from Project CARE suggest that it is one example of efficacious treatment modalities for women who have survived cancer, and future work should focus on developing interventions that can enhance psychosocial adaptation over the life courses of those who have been diagnosed with cancer.

Acknowledgment

We thank the participants and our community partners for their contributions to this research project. We gratefully acknowledge the support and assistance of Dina Dumercy, PharmD, for her role in developing the enhanced breast cancer education materials and facilitating intervention groups. We thank Gabrielle Hazan for her assistance with manuscript preparation and study implementation. We thank Arnetta Phillips for her recruitment and assessment efforts. We acknowledge the Biopsychosocial Oncology Shared Resource of Sylvester Comprehensive Cancer Center and the Disparities and Community Outreach Shared Resource of Sylvester Comprehensive Cancer Center.

Funding

The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research and/or authorship of this article: This publication was made possible by Grant CA R01 131451 from the National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health.

Biographies

Suzanne C. Lechner, PhD, is Research Assistant Professor of Psychiatry and Psychology at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine and Core Leader of the Biopsychosocial Oncology Shared Resource of the Sylvester Comprehensive Cancer Center at the University of Miami. Her research in psycho-oncology focuses on positive adaptation to cancer and health disparities among cancer survivors. This NIH-funded research examines how people adjust to illness and whether psychological, physical, and physiological adjustment is modifiable using stress management and breast cancer education. Her research interests include psychosocial interventions for individuals with cancer, health disparities and psychoneuroimmunology.

Nicole Ennis-Whitehead, PhD, is Assistant Professor in the Department of Clinical and Health Psychology, College of Public Health and Health Professions at the University of Florida in Gainesville, FL. She is a licensed Clinical Psychologist with over 12 years of experience in the psychosocial aspects of disease processes. She earned her doctorate at Kent State University. Her research interests focus on health behaviors, health outcomes and health disparities in minority women.

Belinda Ryan Robertson is a Research Associate in the Cancer Prevention and Control Division of University of Miami Sylvester Comprehensive Cancer Center. She holds a BA in psychology from George Mason University, and facilitated oncology education and support groups with the Life with Cancer Family Center in Merrifield, VA. Her research interests include Minority Women’s Health, psycho-oncology and the effects of psychosocial interventions on health and quality of life of women with cancer.

Debra W. Annane, MA, is currently the Project Manager for Project CARE. She has an MA in journalism from the University of Texas at Austin, and is currently in the graduate program at the University of Miami Department of Epidemiology and Public Health. She holds a BA in anthropology from Florida State University. Her research interests include stress management interventions, disparities research, and public health communication campaigns.

Sara Vargas, MS, is currently a doctoral candidate in psychology at the University of Miami. She has been involved in health-related research since 2004, and has worked on projects related to HIV prevention and quality of life among breast cancer patients.

Charles S. Carver, PhD, is Distinguished Professor of Psychology at the University of Miami. He is the Director of the Adult Division of the graduate program at the University of Miami. His research interests include self-regulation processes, impulse and constraint, two-mode models and depression, coping with cancer, optimism, assessment of coping, behavioral approach and avoidance systems, adult attachment qualities, dynamic systems, and catastrophe theory.

Michael H. Antoni, PhD, is Professor of Psychology and Psychiatry at the University of Miami and holds the title of Sylvester Professor. He leads the Biobehavioral Oncology Research Program at the Sylvester Comprehensive Cancer Center at the University of Miami and directs the Center for Psycho-Oncology Research. His research interests focus on psychoneuroimmunology, examining the effects of stressors and stress management interventions on the adjustment to, and physical course of, diseases such as breast cancer, cervical neoplasia, prostate cancer, chronic fatigue syndrome, and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Alferi SM, Carver CS, Antoni MH, Weiss S, Durán RE. An exploratory study of social support, distress, and life disruption among low-income Hispanic women under treatment for early stage breast cancer. Health Psychology. 2001;20:41–46. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.20.1.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychological Association. About counseling psychologists. 2012a Retrieved from http://www.div17.org/students_defining.html.

- American Psychological Association. Guidelines on Multicultural Education, Training, Research, Practice, and Organizational Change for Psychologists - American Psychological Association. 2012b doi: 10.1037/0003-066x.58.5.377. Retrieved from http://www.apa.org/pi/oema/resources/policy/multicultural-guidelines.aspx. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Andersen BL. Psychological interventions for cancer patients to enhance the quality of life. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1992;60:552–568. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.60.4.552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen DL. Community, physician and consumer outreach strategies to meet recruitment goals. In: Andersen DL, editor. A guide to patient retention and recruitment. Boston, MA: CenterWatch; 2004. pp. 179–197. [Google Scholar]

- Antoni MH. Stress management intervention for women with breast cancer. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Antoni MH, Baggett L, Ironson G, LaPerriere A, August S, Klimas N, Fletcher MA. Cognitive-behavioral stress management intervention buffers distress response and immunologic changes following notification of HIV-1 seropositivity. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1991;59:906–915. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.59.6.906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antoni MH, Lechner SC, Kazi A, Wimberly SR, Sifre T, Urcuyo KR, Carver CS. How stress management improves quality of life after treatment for breast cancer. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74:1143–1152. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.6.1152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antoni MH, Lehman JM, Kilbourn KM, Boyers AE, Culver JL, Alferi SM, Carver CS. Cognitive-behavioral stress management intervention decreases the prevalence of depression and enhances benefit finding among women under treatment for early-stage breast cancer. Health Psychology. 2001;20:20–32. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.20.1.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antoni MH, Pereira DB, Marion I, Ennis N, Andrasik MP, Rose R, O’Sullivan MJ. Stress management effects on perceived stress and cervical neoplasia in low-income HIV-infected women. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2008;65:389–401. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2008.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antoni MH, Wimberly SR, Lechner SC, Kazi A, Sifre T, Urcuyo KR, Carver CS. Reduction of cancer-specific thought intrusions and anxiety symptoms with a stress management intervention among women undergoing treatment for breast cancer. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;163:1791–1797. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.10.1791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashing-Giwa K, Ganz P, Petersen L. Quality of life in African American and White long-term breast cancer survivors. Cancer. 1999;85:418–426. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19990115)85:2<418::aid-cncr20>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashing-Giwa K, Ganz PA. Understanding the breast cancer experience of African-American women. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology. 1997;15:19–35. doi: 10.1300/J077v24n03_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashing-Giwa K, Lim J. Examining emotional outcomes among a multiethnic cohort of breast cancer survivors. Oncology Nursing Forum. 2011;38:279–292. doi: 10.1188/11.ONF.279-288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashing-Giwa KT, Padilla GV, Tejero JS, Kim J. Breast cancer survivorship in a multiethnic sample. Cancer. 2004;101:450–465. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aziz NM, Rowland JH. Cancer survivorship research among ethnic minority and medically underserved groups. Oncology Nursing Forum. 2002;29:789–801. doi: 10.1188/02.ONF.789-801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrera M, Castro FG. A heuristic framework for cultural adaptations of interventions. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2006;13:311–316. [Google Scholar]

- Beder J. Perceived social support and adjustment to mastectomy in socioeconomically disadvantaged Black women. Social Work in Health Care. 1995;22:55–71. doi: 10.1300/j010v22n02_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belgrave FZ, Brome DR, Hampton C. The contribution of Africentric values and racial identity to the prediction of drug knowledge, attitudes, and use among African American youth. Journal of Black Psychology. 2000;26:386–401. [Google Scholar]

- Bernal G, Jiménez-Chafey MI, Domenech Rodríguez MM. Cultural adaptation of evidence-based treatments for ethno-cultural youth. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2009;40:361–368. [Google Scholar]

- Brown D, Fouad M, Basen-Engquist K, Tortolero-Luna G. Recruitment and retention of minority women in cancer screening, prevention, and treatment trials. Annals of Epidemiology. 2000;10:S13–S21. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(00)00197-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey LA, Perou CM, Livasy CA, Dressler LG, Cowan D, Conway K, Millikan RC. Race, breast cancer subtypes, and survival in the Carolina breast cancer study. JAMA. 2006;295:2492–2502. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.21.2492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro FG, Barrera M, Holleran Steiker LK. Issues and challenges in the design of culturally-adapted evidence-based interventions. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2010;6:213–239. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-033109-132032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Classen C, Butler LD, Koopman C, Miller E, DiMiceli S, Giese-Davis J, Spiegel D. Supportive-expressive group therapy and distress in patients with metastatic breast cancer: A randomized clinical intervention trial. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2001;58:494–501. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.5.494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coates RJ, Bransfield DD, Wesley M, Hankey B, Eley JW, Greenberg RS Black/White Cancer Survival Study Group. Differences between Black and White women with breast cancer in time from symptom recognition to medical consultation. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 1992;84:938–950. doi: 10.1093/jnci/84.12.938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbie-Smith G. The continuing legacy of the Tuskegee syphilis study: Considerations for clinical investigation. American Journal of the Medical Sciences. 1999;317:5–8. doi: 10.1097/00000441-199901000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corey G. Theory and practice of counseling and psychotherapy. 8th ed. Pacific Grove, CA: Brooks/Cole; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Cross WE. Shades of Black: Diversity in African-American identity. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Culver JL, Arena PL, Antoni MH, Carver CS. Coping and distress among women under treatment for early stage breast cancer: Comparing African Americans, Hispanics and non-Hispanic Whites. Psycho-Oncology. 2002;11:495–504. doi: 10.1002/pon.615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eley JW, Hill HA, Chen VW, Austin DF, Wesley MN, Muss HB, Edwards BK. Racial differences in survival from breast cancer. Results of the National Cancer Institute Black/White Cancer Survival Study. JAMA. 1994;272:947–954. doi: 10.1001/jama.272.12.947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ell KO, Nishimoto RH. Coping resources in adaptation to cancer: Socioeconomic and racial differences. Social Service Review (Chicago) 1989;63:433–446. [Google Scholar]

- Gamble VN. Under the shadow of Tuskegee: African Americans and health care. American Journal of Public Health. 1997;87:1773–1778. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.11.1773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giedzinska AS, Meyerowitz BE, Ganz PA, Rowland JH. Health-related quality of life in a multiethnic sample of breast cancer survivors. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2004;28:39–51. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm2801_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griner D, Smith TB. Culturally adapted mental health interventions: A metaanalytic review. Psychotherapy. 2006;43:531–548. doi: 10.1037/0033-3204.43.4.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao Y, Landrine H, Smith T, Kaw C, Corral I, Stein K. Residential segregation and disparities in health-related quality of life among Black and White cancer survivors. Health Psychology. 2011;30:137–144. doi: 10.1037/a0022096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hays PA. Integrating evidence-based practice, CBT, and multicultural therapy: 10 steps for culturally competent practice. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2009;40:354–360. [Google Scholar]

- Hewitt M, Greenfield S, Stovall E. From cancer patient to cancer survivor: Lost in transition. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Holland JC, Reznik I. Pathways for psychosocial care of cancer survivors. Cancer. 2005;104:2624–2637. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janz NK, Mujahid MS, Hawley ST, Griggs JJ, Alderman A, Hamilton AS, Katz SJ. Racial/ethnic differences in quality of life after diagnosis of breast cancer. Journal of Cancer Survivorship. 2009;3:212–222. doi: 10.1007/s11764-009-0097-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieger N. Theories for social epidemiology in the 21st century: An ecosocial perspective. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2001;30:668–677. doi: 10.1093/ije/30.4.668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lannin DR, Mathews HF, Mitchell J, Swanson MS. Impacting cultural attitudes in African-American women to decrease breast cancer mortality. American Journal of Surgery. 2002;184:418–423. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(02)01009-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lannin DR, Mathews HF, Mitchell J, Swanson MS, Swanson FH, Edwards MS. Influence of socioeconomic and cultural factors on racial differences in late-stage presentation of breast cancer. JAMA. 1998;279:1801–1807. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.22.1801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lechner SC, Dumercy D, Ennis-Whitehead N, Phillips K, Vargas S. Enhanced education program for Black women who have completed treatment for breast cancer. 2008 Unpublished treatment manual. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez C, Antoni M, Penedo F, Weiss D, Cruess S, Segotas MC, Fletcher MA. A pilot study of cognitive behavioral stress management effects on stress, quality of life, and symptoms in persons with chronic fatigue syndrome. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2011;70:328–334. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2010.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luebbert K, Dahme B, Hasenbring M. The effectiveness of relaxation training in reducing treatment-related symptoms and improving emotional adjustment in acute non-surgical cancer treatment: A meta-analytical review. Psycho-Oncology. 2001;10:490–502. doi: 10.1002/pon.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutgendorf SK, Antoni MH, Ironson G, Klimas N, Kumar M, Starr K, Schneiderman N. Cognitive-behavioral stress management decreases dysphoric mood and herpes simplex virus-type 2 antibody titers in symptomatic HIV-seropositive gay men. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1997;65:31–43. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.1.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marín G, Marín BV. Research with Hispanic populations. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Matthews AK, Tejeda S, Johnson TP, Berbaum ML, Manfredi C. Correlates of quality of life among African American and white cancer survivors. Cancer Nursing. 2012 doi: 10.1097/NCC.0b013e31824131d9. Retrieved from http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=ovftm&NEWS=N&AN=00002820-900000000-99713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- McRae MB, Carey PM, Anderson-Scott R. Black churches as therapeutic systems: A group process perspective. Health Education & Behavior. 1998;25:778–789. doi: 10.1177/109019819802500607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer TJ, Mark MM. Effects of psychosocial interventions with adult cancer patients: A meta-analysis of randomized experiments. Health Psychology. 1995;14:101–108. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.14.2.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyerowitz BE, Richardson J, Hudson S, Leedham B. Ethnicity and cancer outcomes: Behavioral and psychosocial considerations. Psychological Bulletin. 1998;123:47–70. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.123.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore RJ. African American women and breast cancer: Notes from a study of narrative. Cancer Nursing. 2001;24:35–42. doi: 10.1097/00002820-200102000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Cancer Institute Center to Reduce Cancer Health Disparities. Cancer health disparities. 2007 Retrieved from http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/types/disparities.

- Needham J. The importance of retention. In: Anderson DL, editor. A guide to patient recruitment and retention. Boston, MA: CenterWatch; 2004. pp. 167–178. [Google Scholar]

- Osborn RL, Demoncada AC, Feuerstein M. Psychosocial interventions for depression, anxiety, and quality of life in cancer survivors: Meta-analyses. International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine. 2006;36:13–34. doi: 10.2190/EUFN-RV1K-Y3TR-FK0L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paskett ED, Alfano CM, Davidson MA, Andersen BL, Naughton MJ, Sherman A, Hays J. Breast cancer survivors’ health-related quality of life: Racial differences and comparisons with noncancer controls. Cancer. 2008;113:3222–3230. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penedo FJ, Dahn JR, Molton I, Gonzalez JS, Kinsinger D, Roos BA, Antoni MH. Cognitive-behavioral stress management improves stress-management skills and quality of life in men recovering from treatment of prostate carcinoma. Cancer. 2004;100:192–200. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS. When we talk about American ethnic groups, what do we mean? American Psychologist. 1996;51:918–927. [Google Scholar]

- Rehse B, Pukrop R. Effects of psychosocial interventions on quality of life in adult cancer patients: Meta analysis of 37 published controlled outcome studies. Patient Education and Counseling. 2003;50:179–186. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(02)00149-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds P, Boyd PT, Blacklow RS, Jackson JS, Greenberg RS, Austin DF, Edwards BK. The relationship between social ties and survival among Black and White breast cancer patients. National Cancer Institute Black/White Cancer Survival Study Group. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention. 1994;3:253. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds P, Hurley S, Torres M, Jackson J, Boyd P, Chen VW. Use of coping strategies and breast cancer survival: Results from the Black/White cancer survival study. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2000;152:940–949. doi: 10.1093/aje/152.10.940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Hucles J. The first session with African Americans: A step-by-step guide. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Sears SR, Stanton AL, Kwan L, Krupnick JL, Rowland JH, Meyerowitz BE, Ganz PA. Recruitment and retention challenges in breast cancer survivorship research: Results from a multisite, randomized intervention trial in women with early stage breast cancer. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention. 2003;12:1087–1090. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sisters Network Inc. Home page. 2007 Retrieved from http://www.sistersnetworkinc.org.

- Soler-Vila H, Kasl SV, Jones BA. Prognostic significance of psychosocial factors in African-American and white breast cancer patients: A population-based study. Cancer. 2003;98:1299–1308. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speca M, Carlson LE, Goodey E, Angen M. A randomized, waitlist controlled clinical trial: The effect of a mindfulness meditation-based stress reduction program on mood and symptoms of stress in cancer outpatients. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2000;62:613–622. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200009000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer SM, Lehman JM, Wynings C, Arena P, Carver CS, Antoni MH, Love N. Concerns about breast cancer and relations to psychosocial well-being in a multiethnic sample of early-stage patients. Health Psychology. 1999;18:159–168. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.18.2.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sue DW, Sue D. Counseling the culturally diverse: Theory and practice. 4th ed. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Tatrow K, Montgomery GH. Cognitive behavioral therapy techniques for distress and pain in breast cancer patients: A meta-analysis. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2006;29:17–27. doi: 10.1007/s10865-005-9036-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor KL, Lamdan RM, Siegel JE, Shelby R, Moran-Klimi K, Hrywna M. Psychological adjustment among African American breast cancer patients: One-year follow-up results of a randomized psychoeducational group intervention. Health Psychology. 2003;22:316–323. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.22.3.316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trijsburg RW, van Knippenberg FC, Rijpma SE. Effects of psychological treatment on cancer patients: A critical review. Psychosomatic Medicine. 1992;54:489–517. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199207000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- USCensus Bureau. Table DP-1. Profile of general demographic characteristics: 2000. 2002 Retrieved from http://censtats.census.gov/data/FL/05012086.pdf.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. What is Cultural Competency? 2005 Retrieved from http://minorityhealth.hhs.gov/templates/browse.aspx?lvl=2&lvlID=11.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. African American Profile. 2012 Retrieved from http://minorityhealth.hhs.gov/templates/browse.aspx?lvl=2&lvlid=51.

- Williams DR. Race and health: Basic questions, emerging directions. Annals of Epidemiology. 1997;7:322–333. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(97)00051-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilmoth MC, Sanders LD. Accept me for myself: African American women’s issues after breast cancer. Oncology Nursing Forum. 2001;28:875–879. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wimberly SR, Carver CS, Laurenceau J, Harris SD, Antoni MH. Perceived partner reactions to diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer: Impact on psychosocial and psychosexual adjustment. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73:300–311. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.2.300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wingood GM, DiClemente RJ. The ADAPT-ITT model: A novel method of adapting evidence-based HIV interventions. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2008;47(Suppl. 1):S40–S46. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181605df1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]