Highlights

-

•

Misperception of intraoperative anatomy is one of the leading causes of bile duct injuries.

-

•

The “critical view of safety” in laparoscopic cholecystectomy serves the unequivocal identification of the cystic duct before transection.

-

•

A sufficient mobilization of the gallbladder from its bed is essential in performing the “critical view of safety” in laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

Keywords: Laparoscopic cholecystectomy, Bile duct injury, Critical view of safety, Misperception

Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy is the most common laparoscopic surgery performed by general surgeons. Although being a routine procedure, classical pitfalls shall be regarded, as misperception of intraoperative anatomy is one of the leading causes of bile duct injuries. The “critical view of safety” in laparoscopic cholecystectomy serves the unequivocal identification of the cystic duct before transection. The aim of this manuscript is to discuss classical pitfalls and bile duct injury avoiding strategies in laparoscopic cholecystectomy, by presenting an interesting case report.

PRESENTATION OF CASE

A 71-year-old patient, who previously suffered from a biliary pancreatitis underwent laparoscopic cholecystectomy after ERCP with stone extraction. The intraoperative situs showed a shrunken gallbladder. After placement of four trocars, the gall bladder was grasped in the usual way at the fundus and pulled in the right upper abdomen. Following the dissection of the triangle of Calot, a “critical view of safety” was established. As dissection continued, it however soon became clear that instead of the cystic duct, the common bile duct had been dissected. In order to create an overview, the gallbladder was thereafter mobilized fundus first and further preparation resumed carefully to expose the cystic duct and the common bile duct. Consecutively the operation could be completed in the usual way.

DISCUSSION

Despite permanent increase in learning curves and new approaches in laparoscopic techniques, bile duct injuries still remain twice as frequent as in the conventional open approach. In the case presented, transection of the common bile duct was prevented through critical examination of the present anatomy. The “critical view of safety” certainly offers not a full protection to avoid biliary lesions, but may lead to a significant risk minimization when consistently implemented.

CONCLUSION

A sufficient mobilization of the gallbladder from its bed is essential in performing a critical view in laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

1. Introduction

The advent of laparoscopic cholecystectomy in the early 1990s led to a paradigm change and a shift from open approach towards minimally invasive techniques.1 Meanwhile, the laparoscopic cholecystectomy is the most common laparoscopic procedure in general surgery and considered to be the gold standard in the treatment of symptomatic cholelithiasis and acute/chronic cholecystitis.2,3 The laparoscopic technique results in lower postoperative pain, shorter hospital stays and a proper cosmesis.1–7 In times before the laparoscopic era the incidence of biliary injuries after conventional open cholecystectomy amounted ∼0.2%.8 However, despite of contemplated advantages, a rapid learning curve and constant improvements in methodology, the complication rates of bile duct injuries after laparoscopic cholecystectomy count from 0.4% to 0.5%, dependent on the underlying disease and remain higher than in the open approach.9,10 The most common cause of serious biliary injury is misidentification.11

Due to abovementioned significant divergence between open and laparoscopic procedures Strasberg and colleagues in 1995 first suggested a three-pronged strategy called the “critical view of safety” (CVS), to minimize the risk of bile duct injuries in laparoscopic cholecystectomy.12 This technique follows three principles: (1) dissection of the triangle of Calot from all fatty and fibrous tissue, (2) mobilization of the lowest part of the gallbladder from its bed and (3) the unambiguous identification of two and exclusively of two structures (cystic duct, artery cystica) entering the gallbladder [Fig. 1].

Fig. 1.

Critical view of safety by Strasberg et al. the unambiguous exposure of intraoperative anatomical situs before transection of the cystic duct and cystic artery.

In the following case report we highlight the importance of the CVS in laparoscopic cholecystectomy and its classical pitfalls.

2. Case report

A 71-year-old patient presented with upper abdominal pain in our outpatient department. The patient suffered from coronary heart disease and benign prostatic hyperplasia, there was no history of relevant pre-existing surgical conditions. After blood analysis revealed following results: pancreatic—amylase: 1214 U/L [normal range: 13–53 U/L], -lipase: 2619 U/L [13–60 U/L], gamma-GT: 500 U/L [10–71 U/L] and abdominal ultrasound showed presence of gallstones in the gallbladder and dilatation of the common bile duct a magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) was performed. Following the diagnosis of choledocholithiasis a papillotomy with stone extraction via endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) was executed. After an uneventful post-interventional period of two months laparoscopic cholecystectomy was conducted.

The patient signed a patient consent form and laparoscopic cholecystectomy was carried out in a classical four-port technique. After establishment of a pneumoperitoneum and installation of all four ports, a shrunk gallbladder was found [Fig. 2]. First, the gallbladder was grasped in the usual way at the fundus and pulled into the right upper abdomen, followed by dissection of the triangle of Calot [Fig. 3]. Despite adequate preparation and removal of all fatty and fibrose tissue only one structure entering the gallbladder was identified [Fig. 4]. Initially this formation was interpreted as the cystic duct. However, on the one hand the putative cystic duct appeared of strong calibre, on the other hand a successful lateralization of the gall bladder could not be performed. To provide clear anatomical conditions, the gall bladder was entirely dissected from its bed in a ‘fundus first’-approach [Fig. 5]. The initially misinterpreted structure, was now unequivocally identified as the common bile duct. Preparation was continued and finally the cystic duct, showing a long-segment adhesion with the common bile duct was properly identified in terms of a CVS, secured with clips and divided. Following haemostasis of all bleeding sites, inspection of the dissected cystic artery and cystic duct, retrieval of the gallbladder and drainage insertion the procedure could be finished in a conventional manner.

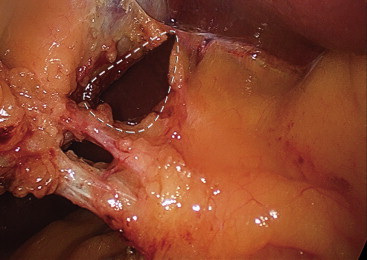

Fig. 2.

Intraoperative image of the shrunken stone gallbladder.

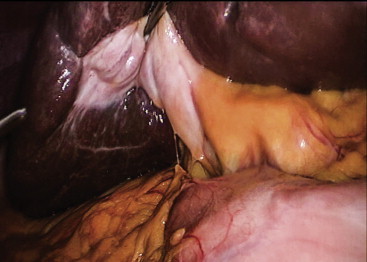

Fig. 3.

Attempt of the “critical view of safety” – only one structure entering the gallbladder can be clearly identified.

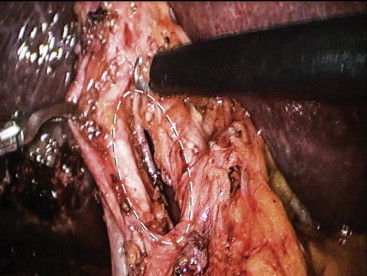

Fig. 4.

Dissection of the gallbladder from the gallbladder bed.

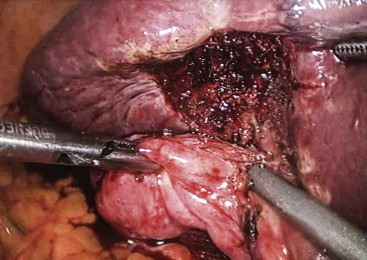

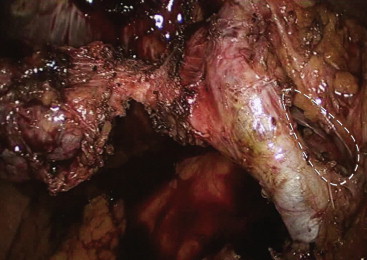

Fig. 5.

“Critical view of safety” – all structures (cystic duct, common bile duct) can be unequivocally identified. The original wrong preparation site is marked on the right.

Drains were removed on 2nd and 3rd postoperative day. The patient was dismissed on 7th postoperative day after an unremarkable postoperative course.

3. Discussion

Nowadays laparoscopic cholecystectomy is regarded as the gold standard in the treatment of gallbladder diseases. According to German Census Bureau 194,000 cholecystectomies are performed annually in Germany.13 The ratio of laparoscopic procedures averages between 90 and 95%.14 An initial rate of bile duct injuries from 0.74% to 2.8% at the onset of the laparoscopic era, could be reduced steadily to about 0.4% nowadays. Nonetheless, despite permanent increase in learning curves and new approaches, bile duct injuries still remain twice as frequent as in the conventional open approach. The introduction of Strasbergs’ CVS could not approximate the original 0.2% rate of bile duct injuries. Howbeit data show, that a consequent use of CVS technique may prevent some biliary injuries, there is no Level I evidence that this technique prevents bile duct injuries in general, as there are no randomized trials published up to date.15,16 The question remains to what extent we surgeons are willing to accept complications when adopting new surgical techniques. Considering minimally-invasive procedures, the assumed benefit of lesser trauma to the patient always has to be balanced against such – undisputable – higher complication rates compared to an open approach, no matter how low the total event rated may be. Like in the case with CVS, strict adherence to such safety nodal points throughout the procedure may help narrowing the gap between complication rates of open and minimally invasive procedures into acceptable bounds. This subject, which has given rise to considerable debate, is a very crucial one, as minimally-invasive methods more and more replace or supplement traditional open surgical approaches.

In the case presented, transection of the common bile duct was prevented through critical examination of the CVS. However, the importance of the CVS shall not be touted as a dogma. Instead, we recommend to use it as a framework, which shall help the surgeon to re-evaluate each surgical step before proceeding. Different anatomies can lead to misinterpretations and lead to pitfalls in hasty preparation situations. Injuries of the common bile duct are the most frequent bile duct injuries described in literature ranging from 66% to 72% of all bile duct lesions.17 Compliance with all three criteria of the CVS may prevent inadvertent bile duct injuries, as it indicates reliable exposure and identification of all structures in the triangle of Calot.

Reported short-term mortality of accidental bile duct injury is approximately 1.9%.18 However, morbidity is much higher. Only 1/3 of all injuries can be treated by ERCP and stenting. In 2/3 of all patients a further surgical biliary reconstruction is necessary. Here, the median hospital stay extends for 8 more days.18 It is difficult to number the impact of these complications on the economy. Stephan B. Archer and colleagues estimated a total annual economic damage of approximately $40 million in the U.S. at 600–700 bile duct injuries.17

The CVS certainly offers not a full protection to avoid biliary lesions, but may lead to a significant risk minimization when consistently implemented. Unfortunately, it can be assumed that probably misperception, rather than technical errors are the leading cause of biliary injuries, as most bile duct lesions occur to experienced surgeons (>200 cholecystectomies performed).17 Therefore, we believe that a consistent adherence of established guidelines in surgery is of particular importance.

4. Conclusion

The rate of bile duct injuries after laparoscopic cholecystectomy averages around 0.4% and can lead to far-reaching consequences for the patients in the postoperative course. The “critical view of safety” can be used as a safe tool to prevent bile duct injury and classical pitfalls under critical evaluation of the surgical process. An adequate mobilization of the gallbladder from its bed and unambiguous identification of the structures entering the gallbladder shall always be ensured.

Conflict of interest

None of the authors has any conflict of interest to disclose regarding this manuscript.

Funding

None.

Ethical approval

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request.

Author's contributions

Tomasz Dziodzio: writing the paper.

Sascha Weiss: proof reading, photo editing.

Robert Sucher: writing the paper.

Matthias Biebl: writing the paper, proof reading.

Johann Pratschke: proof reading.

References

- 1.Flum D.R., Cheadle A., Prela C., Dellinger E.P., Chan L. Bile duct injury during cholecystectomy and survival in medicare beneficiaries. JAMA. 2003;290:2168–2173. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.16.2168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vettoretto N., Saronni C., Harbi A., Balestra L., Taglietti L., Giovanetti M. Critical view of safety during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. JSLS. 2011;15:322–325. doi: 10.4293/108680811X13071180407474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.NIH Gallstones and laparoscopic cholecystectomy. NIH Consens Statement. 1992;10:1–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Soper N.J., Stockmann P.T., Dunnegan D.L., Ashley S.W. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy. The new ‘gold standard’? Arch Surg. 1992;127:917. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1992.01420080051008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schirmer B.D., Edge S.B., Dix J., Hyser M.J., Hanks J.B., Jones R.S. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Treatment of choice for symptomatic cholelithiasis. Ann Surg. 1991;213:665. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199106000-00018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wiesen S.M., Unger S.W., Barkin J.S., Edelman D.S., Scott J.S., Unger H.M. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy: the procedure of choice for acute cholecystitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1993;88:334. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wilson R.G., Macintyre I.M., Nixon S.J., Saunders J.H., Varma J.S., King P.M. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy as a safe and effective treatment for severe acute cholecystitis. BMJ. 1992;305:394. doi: 10.1136/bmj.305.6850.394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Adamsen S., Hansen O.H., Funch-Jensen P. Bile duct injury during laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a prospective nationwide series. J Am Coll Surg. 1997;184:571–578. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vollmer C.M., Jr., Callery M.P. Biliary injury following laparoscopic cholecystectomy: why still a problem? Gastroenterology. 2007;133:1039. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.07.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khan M.H., Howard T.J., Fogel E.L., Sherman S., McHenry L., Watkins J.L. Frequency of biliary complications after laparoscopic cholecystectomy detected by ERCP: experience at a large tertiary referral center. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;65:247. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2005.12.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Strasberg S.M., Brunt L.M. Rationale and use of the critical view of safety in laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Am Coll Surg. 2010;211:132–138. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2010.02.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Strasberg S.M., Hertl M., Soper N.J. An analysis of the problem of biliary injury during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Am Coll Surg. 1995;180:101–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gesundheitsberichterstattung des Bundes hrsg. vom Statistischen Bundesamt. www.gbe-bund.de.

- 14.Gutt C.N., Encke J., Köninger J., Harnoss J.C., Weigand K., Kipfmüller K. Acute cholecystitis: early versus delayed cholecystectomy, a multicenter randomized trial (ACDC Study, NCT00447304) Ann Surg. 2013;258:385–393. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3182a1599b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Avgerinos C., Kelgiorgi D., Touloumis Z., Baltatzi L., Dervenis C. One thousand laparoscopic cholecystectomies in a single surgical unit using the “critical view of safety” technique. J Gastrointest Surg. 2009;13:498–503. doi: 10.1007/s11605-008-0748-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yegiyants S., Collins J.C. Operative strategy can reduce the incidence of major bile duct injury in laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Am Surg. 2008;74:985–987. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Archer S.B., Brown D.W., Smith C.D., Branum G.D., Hunter J.G. Bile duct injury during laparoscopic cholecystectomy: results of a national survey. Ann Surg. 2001;234:549–558. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200110000-00014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pitt H.A., Sherman S., Johnson M.S., Hollenbeck A.N., Lee J., Daum M.R. Improved outcomes of bile duct injuries in the 21st century. Ann Surg. 2013;258:490–499. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3182a1b25b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]