Abstract

The cell adhesion molecule (CAM), N-cadherin, has emerged as an important oncology therapeutic target. N-cadherin is a transmembrane glycoprotein mediating the formation and structural integrity of blood vessels. Its expression has also been documented in numerous types of poorly differentiated tumours. This CAM is involved in regulating the proliferation, survival, invasiveness and metastasis of cancer cells. Disruption of N-cadherin homophilic intercellular interactions using peptide or small molecule antagonists is a promising novel strategy for anti-cancer therapies. This review discusses: the discovery of N-cadherin, the mechanism by which N-cadherin promotes cell adhesion, the role of N-cadherin in blood vessel formation and maintenance, participation of N-cadherin in cancer progression, the different types of N-cadherin antagonists and the use of N-cadherin antagonists as anti-cancer drugs.

Keywords: N-cadherin antagonists, ADH-1, endothelial cells, angiogenesis, cancer

1. Introductory comments concerning N-cadherin and calcium-dependent cell adhesion

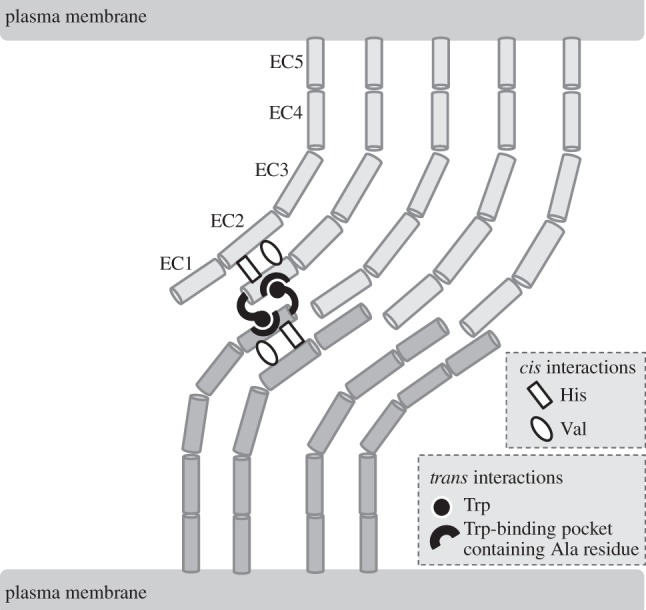

Neural (N)-cadherin is an integral membrane, calcium-binding glycoprotein that mediates the intercellular adhesion of neuronal cells and many other types of non-neuronal cells [1–3]. The extracellular domain of N-cadherin is composed of five subdomains (EC1–EC5; figure 1) [1,2]. Three calcium ions bind between each successive duo of subdomains (i.e. EC1-EC2, EC2-EC3, EC3-EC4 and EC4-EC5). The binding of calcium ions stabilizes the elongated, curved structure of N-cadherin thus enabling the proper function of this cell adhesion molecule (CAM) [2].

Figure 1.

Diagram showing the extracellular domains of N-cadherin monomers simultaneously interacting within the plane of the cell's plasma membrane (referred to as cis interactions) and at adhesive contacts between apposed cells (referred to as trans interactions). His and Val residues within the first extracellular (EC1) subdomain of N-cadherin monomers mediate cis interactions with the second extracellular (EC2) subdomain of adjacent N-cadherin monomers. The Trp and Ala residues within the EC1 subdomain of N-cadherin monomers directly mediate trans interactions. The Trp residue at the N-terminus of each N-cadherin monomer inserts into an apposed hydrophobic pocket containing an Ala residue. See text for further details.

Cells comprising vertebrate tissues have been shown to possess calcium-dependent and calcium-independent adhesion mechanisms [4,5]. The calcium-dependent adhesion mechanism is resistant to proteolysis in the presence of calcium, whereas the calcium-independent adhesion mechanism is not. Treatment of cells with proteases (e.g. trypsin) in the presence of ethylene gycol tetraacetic acid (EGTA, which results in the removal of calcium from the medium) abolishes calcium-dependent adhesion.

N-cadherin was identified in the 1980s by two groups: Volk & Geiger [6–8] and Hatta & Takeichi [9]. Volk and Geiger were seeking to elucidate the CAMs present in a particular intercellular junction, known as the adherens junction. They prepared an intercalated disc-enriched membrane fraction containing adherens junctions from chicken cardiac muscle and then extracted it with detergent [6]. This detergent extract was used to immunize mice and generate hybridomas. One of the hybridomas was found to secrete a monoclonal antibody (designated ID-7.2.3) that recognized a membrane glycoprotein component of adherens junctions present in intercalated discs, as judged by immunoelectron microscopy [6,7]. Volk and Geiger named this glycoprotein adherens junction-specific CAM (A-CAM) [7]. They proceeded to demonstrate that A-CAM was degraded by trypsin in the presence of EGTA. It is noteworthy that the formation of adherens junctions does not occur in the absence of calcium. Finally, monovalent Fab fragments of ID-7.2.3 were shown to be capable of blocking the formation of adherens junctions by cultured cells [8]. Collectively, these observations provided strong evidence that A-CAM was directly involved in mediating the calcium-dependent formation of adherens junctions. It was later shown that A-CAM was identical to N-cadherin [10].

Hatta & Takeichi [9] speculated that surface proteins present on cells after treatment with trypsin in the presence of calcium were candidate CAMs responsible for mediating calcium-dependent adhesion. They immunized rats with cells obtained from the neural retina of 6-day-old chick embryos dissociated by trypsin in the presence of calcium and subsequently generated hybridomas from the splenocytes of these animals. The monoclonal antibodies secreted by the hybridomas were then screened against western blots containing protein extracts of either cells treated with trypsin in the presence of calcium or cells treated with trypsin in the presence of EGTA. A hybridoma was indentified that secreted a monoclonal antibody (designated NCD-2) which recognized an antigen (molecular mass 127 kDa) on western blots prepared from the protein extracts of cells treated with trypsin in the presence of calcium, but not from cells treated with trypsin in the presence of EGTA. NCD-2 reacted with the surface of cells dissociated from neural retina of 6-day-old chick embryos by trypsin in the presence of calcium. Furthermore, NCD-2 blocked the aggregation of these cells. Finally, NCD-2 recognized the antigen in all neuronal tissues examined, as well as the heart, as judged by probing western blots of protein extracts from these tissues with this monoclonal antibody. The antigen was not detected in skin, liver, kidney and lung protein extracts. This distribution was similar to that observed in mouse embryos [11]. Based on these observations, the antigen was named N-cadherin.

The nucleotide sequence of cDNA encoding chicken N-cadherin was subsequently determined and the amino acid sequence was deduced from this information [1]. The data suggested that N-cadherin had extracellular, transmembrane and cytoplasmic domains. An expression vector containing N-cadherin cDNA was transfected into mouse L cells that do not express this CAM or display calcium-dependent cell adhesion. The transfected cells exhibited calcium-dependent aggregation in suspension. NCD-2 prevented the aggregation of these cells. These observations substantiate the contention that N-cadherin is a calcium-dependent CAM.

2. Mechanism by which N-cadherin promotes cell adhesion

N-cadherin monomers exist in many different states within the plane of the cell's plasma membrane and at intercellular adhesive contacts, where they function as homophilic CAMs [2,12,13]. In order to form stable intercellular adhesive junctions, the monomers apparently must interact within the plane of the plasma membrane (referred to as cis interactions) and also with monomers on the surface of apposing cells (referred to as trans interactions) (figure 1). These cis and trans interactions are centred around the cell adhesion recognition (CAR) sequence Histidine–Alanine–Valine (His79–Ala80–Val81) which is found towards the end of the first extracellular (EC1) subdomain of N-cadherin [1,2,13,14]. This sequence was predicted to be directly involved in mediating cell adhesion over two decades ago [14,15]. Recent studies suggest that the His79 and Val81 residues promote cis interactions, whereas the Ala80 residue facilitates trans interactions [2,12,13]. The Ala80 residue is a constituent of a hydrophobic pocket into which docks a tryptophan (Trp2) residue at the N-terminus of an apposed N-cadherin EC1 domain, thus promoting intercellular adhesion (figure 1).

3. Role of N-cadherin in the vasculature

N-cadherin is intimately involved in the formation of blood vessels (a process known as angiogenesis) and the maintenance of their integrity [3,16–18]. Blood microvessels are composed of endothelial and mural cells (pericytes). One of the fundamental functions of pericytes is to stabilize mature microvessels [17,18]. N-cadherin is found at adhesive complexes between endothelial cells and the pericytes that ensheath them [3,16–18]. Inhibition of N-cadherin function destabilizes microvessels [16,18]. For example, antibodies directed against N-cadherin disrupt endothelial cell–pericyte adhesive complexes and cause microvessels to haemorrhage [16]. These observations underline the importance of N-cadherin-mediated endothelial cell–pericyte adhesive interactions to microvessel stablilty.

4. Role of N-cadherin in tumour growth and progression

Increased tumour growth is dependent on an adequate blood supply [19,20]. Angiogenesis therefore plays a central role in enabling tumour growth. As discussed in §3, N-cadherin is involved in angiogenesis and the maintenance of blood vessel stability. Tumour growth is consequently dependent on N-cadherin. Antagonists of this CAM could conceivably affect tumour growth.

N-cadherin is also expressed by many tumour types: poorly differentiated carcinomas [21], melanoma [22], neuroblastoma [23] and multiple myeloma [6].

Normal epithelial cells express epithelial (E)-cadherin, a CAM closely related to N-cadherin [3,21,24]. Poorly differentiated carcinoma cells cease to express E-cadherin and instead display N-cadherin. Numerous studies have shown that loss of E-cadherin and the aberrant expression of N-cadherin causes tumour cells to lose their polarity, resist apoptosis, become invasive and metastatic. N-cadherin antagonists therefore have the potential of causing tumour cell apoptosis and suppressing metastasis. The ability of N-cadherin to regulate the behaviour of tumour cells has been attributed in part to the interaction with, and activation of, fibroblast growth factor receptor [24–26]. In vivo, further complexities are apparent in the molecular mechanisms underlying the ability of N-cadherin to influence cancer cell metastasis which remain to be fully elucidated. In particular, the N-cadherin-mediated interactions between tumour cells and either endothelial or stromal cells during the metastatic process have not been thoroughly investigated. Studies are also needed to determine the role of N-cadherin in the establishment of metastases at secondary sites [27].

5. N-cadherin antagonists

Several types of N-cadherin antagonists have been discovered. Three types of antagonists are based on the CAR sequence His–Ala–Val (HAV): synthetic linear peptides, synthetic cyclic peptides and non-peptidyl peptidomimetics [28].

Synthetic linear peptides containing the HAV motif were the first peptides shown to be capable of inhibiting N-cadherin-dependent processes [14,29–31]. For example, the decapeptide N-Ac-LRAHAVDING-NH2, whose sequence is identical to that found in the EC1 subdomain of human N-cadherin, was shown to block neurite outgrowth [29], myoblast fusion [30] and Schwann cell migration on astrocytes [31].

Synthetic cyclic peptides harbouring the HAV motif were subsequently shown to act as N-cadherin antagonists [32]. The most studied cyclic peptide is N-Ac-CHAVC-NH2 (designated ADH-1) [3]. This cyclic peptide, like the linear peptide, is capable of disrupting a wide variety of N-cadherin-mediated processes. Importantly, ADH-1 has been shown to inhibit angiogenesis [33]. In addition, studies have demonstrated that ADH-1 can cause apoptosis of multiple myeloma [34], neuroblastoma [23] and pancreatic [35] cancer cells. Not all tumour cells displaying N-cadherin undergo apoptosis when exposed to ADH-1. For example, this cyclic peptide does not cause apoptosis in various melanoma cell lines that express N-cadherin [36]. Instead, ADH-1 appears to sensitize these cells to the cytotoxic agent melphalan. The mechanism by which ADH-1 increases the cytotoxic effects of melphalan remains to be elucidated. ADH-1 has been shown to inhibit pancreatic and melanoma tumour growth in animal models when used alone [35], or in combination with cytotoxic agents [36], respectively.

Non-peptidyl peptidomimetics of ADH-1 have also been identified [3,37]. Unlike peptides which are rapidly degraded by gastrointestinal enzymes, such small molecule inhibitors might be suitable for oral administration. The biological properties of these peptidomimetics remain to be determined.

A different type of N-cadherin antagonist has recently been discovered [38]. This type of antagonist is a synthetic linear peptide that harbours a Trp residue in the second position from the N-terminus (similar to N-cadherin). The peptide H-SWTLYTPSGQSK-NH2 inhibits endothelial cell tube formation in vitro indicating that it has anti-angiogenic properties [38]. The biological properties of this peptide have not been extensively investigated.

The final type of N-cadherin antagonist to be developed is monoclonal antibodies. Two such monoclonal antibodies directed against the N-cadherin extracellular domain are capable of inhibiting the invasiveness and proliferation of N-cadherin expressing PC3 human prostate carcinoma cells in vitro [39]. These antibodies also suppress PC3 tumour growth and lymph node metastases in vivo.

Collectively, these observations indicate the potential of N-cadherin antagonists for serving as inhibitors of tumour growth and metastasis.

6. N-cadherin antagonists as anti-cancer drugs

The use of N-cadherin antagonists in the clinic as oncology therapeutics is at an early stage of investigation. Only a few clinical trials have been conducted with ADH-1 and there have been no trials with other N-cadherin antagonists. ADH-1 was not toxic at the doses tested in animals [36] and humans [40] indicating that this N-cadherin antagonist does not affect the normal vasculature. There have been indications that ADH-1 might be useful in treating ovarian cancer [40]. In addition, clinical trials testing ADH-1 in combination with melphalan have shown promise in the treatment of melanoma [41].

7. Summary and future directions

The CAM N-cadherin is capable of regulating the proliferation, survival, invasiveness and metastasis of certain tumour cell types, as well as blood vessel formation and stability. Consequently, N-cadherin antagonists can potentially affect many aspects of tumour growth and progression.

The N-cadherin antagonist ADH-1 has been shown to be an anti-angiogenic agent and can cause tumour cell apoptosis. Limited clinical trials with ADH-1 have suggested that it may be useful as an anti-cancer drug. Clearly, more studies are needed to test this hypothesis. It also remains to be determined which tumour types are most responsive to ADH-1.

The identification of orally available, small molecule N-cadherin antagonists is encouraging. Studies are needed to determine the effects of these antagonists on tumours and their vasculature.

References

- 1.Hatta K, Nose A, Nagafuchi A, Takeichi M. 1988. Cloning and expression of cDNA encoding a neural calcium-dependent cell adhesion molecule: its identity in the cadherin gene family. J. Cell Biol. 106, 873–881. ( 10.1083/jcb.106.3.873) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harrison OJ, et al. 2011. The extracellular architecture of adherens junctions revealed by crystal structures of type I cadherins. Structure 19, 244–256. ( 10.1016/j.str.2010.11.016) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blaschuk OW, Devemy E. 2009. Cadherins as novel targets for anti-cancer therapy. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 625, 195–198. ( 10.1016/j.ejphar.2009.05.033) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Takeichi M. 1988. The cadherins: cell–cell adhesion molecules controlling animal morphogenesis. Development 102, 639–655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Magnani JL, Thomas WA, Steinberg MS. 1981. Two distinct adhesion mechanisms in embryonic neural retina cells. I. A kinetic analysis. Dev. Biol. 81, 96–105. (doi:10.0012-1606(81)90351-1) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Volk T, Geiger B. 1984. A 135-kd membrane protein of intercellular adherens junctions. EMBO J. 3, 2249–2260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Volk T, Geiger B. 1986. A-CAM: a 135-kD receptor of intercellular adherens junctions. I. Immunoelectron microscopic localization and biochemical studies. J. Cell Biol. 103, 1441–1450. ( 10.1083/jcb.103.4.1441) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Volk T, Geiger B. 1986. A-CAM: a 135-kD receptor of intercellular adherens junctions. II. Antibody-mediated modulation of junction formation. J. Cell Biol. 103, 1451–1464. ( 10.1083/jcb.103.4.1451) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hatta K, Takeichi M. 1986. Expression of N-cadherin adhesion molecules associated with early morphogenetic events in chick development. Nature 320, 447–449. ( 10.1038/320447a0) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Volk T, Volberg T, Sabanay I, Geiger B. 1990. Cleavage of A-CAM by endogenous proteinases in cultured lens cells and in developing chick embryos. Dev. Biol. 139, 314–326. ( 10.1016/0012-1606(90)90301-X) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hatta K, Okada TS, Takeichi M. 1985. A monoclonal antibody disrupting calcium-dependent cell-cell adhesion of brain tissues: possible role of its target antigen in animal pattern formation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 82, 2789–2793. ( 10.1073/pnas.82.9.2789) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bunse S, Garg S, Junek S, Vogel D, Ansari N, Stelzer EH, Schuman E. 2013. Role of N-cadherin cis and trans interfaces in the dynamics of adherens junctions in living cells. PLoS ONE 8, e81517 ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0081517) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brasch J, Harrison OJ, Honig B, Shapiro L. 2012. Thinking outside the cell: how cadherins drive adhesion. Trends Cell Biol. 22, 299–310. ( 10.1016/j.tcb.2012.03.004) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blaschuk OW, Sullivan R, David S, Pouliot Y. 1990. Identification of a cadherin cell adhesion recognition sequence. Dev. Biol. 139, 227–229. ( 10.1016/0012-1606(90)90290-Y) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blaschuk OW, Pouliot Y, Holland PC. 1990. Identification of a conserved region common to cadherins and influenza strain A hemagglutinins. J. Mol. Biol. 211, 679–682. ( 10.1016/0022-2836(90)90065-T) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gerhardt H, Wolburg H, Redies C. 2000. N-cadherin mediates pericyte–endothelial interaction during brain angiogenesis in the chicken. Dev. Dyn. 218, 472–479. () [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gaengel K, Genové G, Armulik A, Betsholtz C. 2009. Endothelial-mural cell signalling in vascular development and angiogenesis. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 29, 630–638. ( 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.161521) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Paik J-H, Skoura A, Chae S-S, Cowan AE, Han DK, Proia RL, Hla T. 2004. Sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor regulation of N-cadherin mediates vascular stabilization. Genes Dev. 18, 2392–2403. ( 10.1101/gad.1227804) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Folkman J. 2007. Angiogenesis: an organizing principle for drug discovery? Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 6, 273–286. ( 10.1038/nrd2115) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Naumov GN, Folkman J, Straume O, Akslen LA. 2008. Tumor-vascular interactions and tumor dormancy. APMIS 116, 569–585. ( 10.1111/j.1600-0463.2008.01213.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Berx G, van Roy F. 2009. Involvement of members of the cadherin superfamily in cancer. Cold Spring Harbor Perspect. Biol. 1, a003129 ( 10.1101/cshperspect.a003129) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Beasley GM, et al. 2011. Prospective multicenter phase II trial of systemic ADH-1 in combination with melphalan via isolated limb infusion in patients with advanced extremity melanoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 29, 1210–1215. ( 10.1200/JCO.2010.32.1224) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lammens T, et al. 2012. N-Cadherin in neuroblastoma disease: expression and clinical significance. PLoS ONE 7, e31206 ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0031206) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wheelock MJ, Shintani Y, Maeda M, Fukumoto Y, Johnson KR. 2008. Cadherin switching. J. Cell Sci. 121, 727–735. ( 10.1242/jcs.000455) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Suyama K, Shapiro I, Guttman M, Hazan RB. 2002. A signaling pathway leading to metastasis is controlled by N-cadherin and the FGF receptor. Cancer Cell 2, 301–314. ( 10.1016/S1535-6108(02)00150-2) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Qian X, et al. 2013. N-cadherin/FGFR promotes metastasis through epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and stem/progenitor cell-like properties. Oncogene 33, 3411–3421. ( 10.1038/onc.2013.310) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grinberg-Rashi H, et al. 2009. The expression of three genes in primary non-small cell lung cancer is associated with metastatic spread to the brain. Clin. Cancer Res. 15, 1755–1761. ( 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-2124) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Blaschuk OW. 2012. Discovery and development of N-cadherin antagonists. Cell Tissue Res. 348, 309–313. ( 10.1007/s00441-011-1320-5) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Doherty P, Rowett LH, Moore SE, Mann SE, Walsh FS. 1991. Neurite outgrowth in response to transfected N-CAM and N-cadherin reveals fundamental differences in neuronal responsiveness to CAMs. Neuron 6, 247–258. ( 10.1016/0896-6273(91)90360-C) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mege RM, Goudou D, Diaz C, Nicolet M, Garcia L, Geraud G, Rieger F. 1992. N-cadherin and N-CAM in myoblast fusion: compared localisation and effect of blockade by peptides and antibodies. J. Cell Sci. 103, 897–906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wilby MJ, Muir EM, Fok-Seang J, Gour BJ, Blaschuk OW, Fawcett JW. 1999. N-cadherin inhibits Schwann cell migration on astrocytes. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 14, 66–84. ( 10.1006/mcne.1999.0766) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Blaschuk OW, Gour B. 2000. Compounds and methods for modulating cell adhesion. United States Patent Number 6,031,072.

- 33.Blaschuk OW, Gour BJ, Farookhi R, Anmar A. 2003. Compounds and methods for modulating endothelial cell adhesion. United States Patent Number 6,610,821.

- 34.Sadler NM, Harris BR, Metzger BA, Kirshner J. 2013. N-cadherin impedes proliferation of the multiple myeloma cancer stem cells. Am. J. Blood Res. 3, 271–285. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shintani Y, Fukumoto Y, Chaika N, Grandgenett PM, Hollingsworth MA, Wheelock MJ, Johnson KR. 2008. ADH-1 suppresses N-cadherin-dependent pancreatic cancer progression. Int. J. Cancer 122, 71–77. ( 10.1002/ijc.23027) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Augustine CK, Yoshimoto Y, Gupta M, Zipfel PA, Selim MA, Febbo P, Pendergast AM, Peters WP, Tyler DS. 2008. Targeting N-cadherin enhances antitumor activity of cytotoxic therapies in melanoma treatment. Cancer Res. 68, 3777–3784. ( 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5949) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gour BJ, Blaschuk OW, Ali A, Ni F, Chen Z, Michaud S, Wang S, Hu Z. 2007. Peptidomimetic modulators of cell adhesion. United States Patent Number 7,268,115.

- 38.Devemy E, Blaschuk OW. 2008. Identification of a novel N-cadherin antagonist. Peptides 29, 1853–1861. ( 10.1016/j.peptides.2008.06.025) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tanaka H, et al. 2010. Monoclonal antibody targeting of N-cadherin inhibits prostate cancer growth, metastasis and castration resistance. Nat. Med. 16, 1414–1420. ( 10.1038/nm.2236) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Perotti A, et al. 2009. Clinical and pharmacological phase I evaluation of Exherin (ADH-1), a selective anti-N-cadherin peptide in patients with N-cadherin expressing solid tumours. Ann. Oncol. 20, 741–745. ( 10.1093/annonc/mdn695) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Beasley GM, et al. 2009. A phase 1 study of systemic ADH-1 in combination with melphalan via isolated limb infusion in patients with locally advanced in-transit malignant melanoma. Cancer 115, 4766–4774. ( 10.1002/cncr.24509) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]