Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Multicystic biliary hamartoma is a rare liver tumor that was first described in 2005. Only nine cases are reported in the literature and all of them originate from Eastern patient populations, specifically Japan and Korea.

PRESENTATION OF CASE

Herein we report the occurrence of the tenth multicystic biliary hamartoma reported to date, arising in a Caucasian American woman initially presenting with abdominal pain. At 4.7 cm this is the second largest tumor reported to date and the only one arising in a Western patient population.

DISCUSSION

The patient underwent multimodality imaging and the tumor was biopsied preoperatively, but the diagnosis remained unclear. An extended right hepatectomy was performed for resection of her tumor, and the tumor was definitively diagnosed based on the surgically resected specimen. As all nine of the previously reported cases also underwent resection, the natural history of this lesion remains unknown. The lack of both recurrence and tumor spread in the previously reported cases indicates that this may be a benign lesion not requiring surgical resection unless symptomatic.

CONCLUSION

Multicystic biliary hamartoma is an extremely rare tumor. Increased awareness of the radiologic and pathologic features will likely lead to the diagnoses of further cases in both Western and Eastern populations and could potentially assist with preoperative diagnosis. The natural history and optimal management of this tumor remain uncertain.

Keywords: Hamartoma, Biliary neoplasm, Periductal, Cystic, Honeycomb

1. Introduction

Multicystic biliary hamartoma (MBH) is a rare liver lesion that has been described in the last decade as a distinct entity from other previously classified hepatobiliary cystic lesions.1 There are currently nine cases reported in the literature, with all previous reports originating from Japan or Korea (Table 1).1–5 Herein we report a case of a MBH occurring in a Caucasian woman presenting with abdominal pain. At 4.7 cm it is the second largest lesion reported in the literature, as well as the only one reported from a Western population to date.

Table 1.

Multicystic biliary hamartomas cases reported to date.

| Reference | Country of origin | Cases reported | Largest tumor measurement (cm) | Patients’ ages and genders | Surgical resection performed | Patient presentation | Co-existing liver disease |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Song et al. [2] | Korea | 1 | 2.7 | 52M | Not stated | Abdominal pain | None |

| Ryu et al.a[1] | Japan | 3 | 2.0–3.5b | 45M 58M 55F |

Partial resection Partial resection Lateral segmentectomy |

Incidental finding on US for routine checkup Incidental finding on US for routine checkup Elevated LFTs |

None None None |

| Kai et al. [3] | Japan | 1 | 5.0 | 55M | Partial resection of posterior segment | Finding on US during workup for Hepatitis B | Hepatitis B |

| Zen et al. [4] | Japan | 3 | 1.8 2.8 4.2 |

59M 69F 70F |

Left hepatectomy Resection of medial segment Left segmentectomy |

Right-sided abdominal pain Incidental on imaging Elevated LFTs |

None HCV cirrhosis None |

| Kobayashi et al. [5] | Japan | 1 | 3.6 | 30M | Partial hepatectomy | Incidental finding on imaging | None |

Ryu et al. actually reported the imaging findings of four cases, however one of the cases, that of the 70-year-old female, had been previously reported in the group's 2006 paper, Zen et al., so only the other three cases are summarized in this table.

A range of tumor sizes was provided in this paper but specific measurements of each tumor were not.

2. Presentation of case

In January 2014, we evaluated a 48-year-old woman for a newly diagnosed right liver mass. She was symptomatic with epigastric and right upper quadrant abdominal pain. Her past medical history was remarkable for recently diagnosed hepatitis C. She had undergone an open cholecystectomy 20 years previously for biliary colic and a hysterectomy 10 years earlier for abnormal uterine bleeding. She also reported that her paternal aunt had passed away in the 1980s from a very rare liver tumor.

Her workup prior to presentation at our hospital included an abdominal ultrasound demonstrating an echogenic 5.7 cm mass in the right lobe of the liver. CT scan showed a 5.6 × 3.4 cm lobulated subcapsular mass in segment 8 (Fig. 1). Two additional subcentimeter cystic lesions, consistent with microhamartomas, were noted in segment 7 (Fig. 1b). MRI highlighted its tubulocystic composition and intermingled normal hepatic tissue (Fig. 2). She had undergone a needle biopsy of this lesion at an outside hospital that on microscopic exam demonstrated thick, dense fibrous tissue containing cytologically bland, large caliber bile ducts with intermingled benign hepatocytes (Fig. 4c). Given the multicystic nature on imaging and microscopic findings, this was initially diagnosed as a possible biliary adenofibroma and the patient was referred to our institution for surgical evaluation. Complete laboratory studies including CBC, LFTs, CA19-9, CEA, AFP and hepatitis serologies were all within normal limits, aside from a HCV antibody that was positive. HCV RNA and viral load were non-detectable.

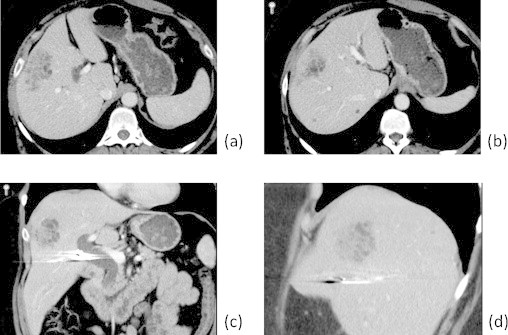

Fig. 1.

Axial (a and b), coronal (c) and sagittal (d) contrast-enhanced CT images through the liver demonstrate a 5.6 × 3.4 cm ill-defined lobulated mass located subcapsular in segment 8 of the liver. The lesion is predominantly composed of tubulocystic structures intermingled with strands of hepatic parenchyma. Two small additional microhamartomas are identified in segment 7 (b).

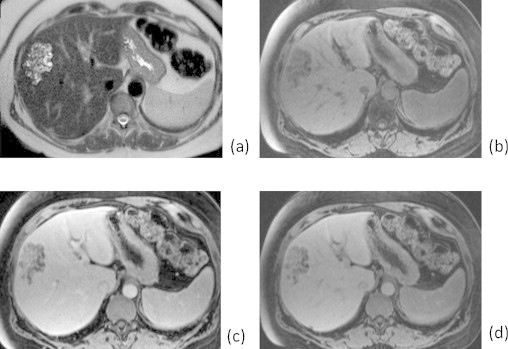

Fig. 2.

Axial fat-suppressed T2-weighted image (a) through the lesion better demonstrates its tubulocystic composition. Pre-gadolinium (b), early post-gadolinium (c), and delayed post-gadolinium (d) images are included. T1-weighted image (d) demonstrates the enhancement of the intermingled liver tissue similar to that of surrounding liver parenchyma.

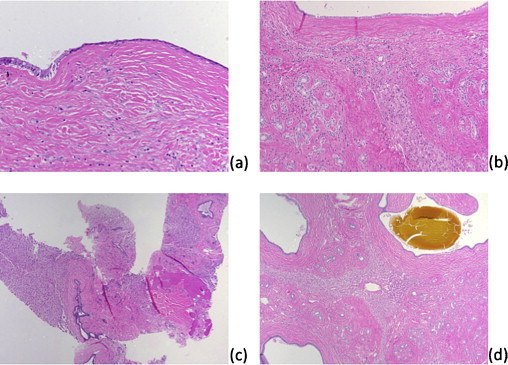

Fig. 4.

Resection, microscopic image: large duct with cystic dilation; the left shows the usual single layer, columnar cell morphology while the right shows an attenuated appearance with a cuboidal cell morphology, 200× magnification (a). Resection, microscopic image: large duct (top), periductal glands (left and right), hepatic parenchyma (center) and intervening dense fibrous tissue, 100× magnification (b). Biopsy, microscopic image: hepatic parenchyma (left and right) separated dense fibrous tissue containing large ducts (center and top right); the periductal glandular component is not seen in this field, 40× magnification (c). Resection, microscopic image: the tumor is composed of large ducts (corners of image, one duct containing bile-like material at upper right), periductal glands (best seen at lower right), entrapped hepatic parenchyma (center), and dense fibrous tissue between the former three components, 40× magnification (d).

Given the possible diagnosis of biliary adenomafibroma and the potential for malignancy, the patient underwent an extended right hepatectomy. Intraoperative ultrasound demonstrated tumor extension into segment 4A and involved part of the middle hepatic vein. During the dissection, note was made of a sizeable replaced left hepatic artery and a portal vein that lacked a right common trunk but instead gave direct rise to the right anterior and posterior branches at the bifurcation. The patient recovered without complication and was discharged from the hospital the following week. She is now eight months post-surgery and has yet to undergo any repeat abdominal imaging.

On pathologic examination, the lesion measured 4.7 × 4.3 × 4.0 cm and consisted of a subcapsular, intrahepatic, well-circumscribed mass with solid and cystic cut surfaces (Fig. 3). Microscopic exam revealed large bile ducts with varying degrees of cystic dilation, periductal glands surrounded by fibrous tissue with interspersed islands of benign hepatocytes, and bile-like material observed within some of the large ducts (Fig 4b and d). These features were consistent with a diagnosis of MBH.1,4 The background non-lesional liver demonstrated only mild macrovesicular steatosis without significant fibrosis.

Fig. 3.

Resection, macroscopic image: closeup showing entrapped hepatic parenchyma intermingled within central and peripheral areas of lesion. Cysts range in size from 0.1 to 1.3 cm.

3. Discussion

The diagnosis of MBH proved challenging, as demonstrated by the inability to preoperatively diagnose this lesion based on the radiographic studies and needle biopsies. In a series of four cases diagnosed by examination of surgically resected specimens from 1998 to 2007, two cases were originally diagnosed as unusual hepatobiliary hamartomas; only after retrospective review, in light of the original descriptions of the histologic findings published in 2006, were these diagnoses corrected.1 To our knowledge, our case is the first reported that demonstrates findings from preoperative needle core biopsies.

The nine previously reported cases in the literature all originated from Eastern patient populations, but beyond that commonality the patients’ characteristics and initial clinical presentations varied widely (Table 1). Patients’ ages at time of diagnosis ranged from 30 to 70 years (average 54.8 ± 12.1 years) and six were male. Two patients presented with abdominal pain; the other tumors were discovered incidentally on ultrasound imaging during routine surveillance or during workup for elevated LFTs. One patient had known HCV cirrhosis and one was positive for HBV surface antigen; the remaining seven had no known liver disease. Every case underwent resection with surgeries ranging from partial segmentectomies to lobectomies. Follow-up was reported for six of the nine cases, with all patients remaining disease free following resection. Follow-up times ranged from three months to 16 years. Tumors were solitary, ranged in size from 1.8 to 5.0 cm and were located in various segments in both liver lobes. Initial descriptions by Zen et al. summarized the pathology of three cases of MBHs as sharing the following characteristics1: location around the hepatic capsule near the falciform ligament,2 macroscopic protrusion from the liver,3 histologic composition consisting of ductal structures, periductal glands and fibrous connective tissue,4 bile-like material present within ducts and 5 a biliary-type cytokeratin profile by immunohistochemical studies on the ductal and glandular elements within the lesion.4 In subsequent reports, the majority of lesions occurred in a peripheral location (four cases) but only one case showed protrusion from the liver.1–3

The radiographic appearance of the lesion in our case is that of a peripherally located, tubulocystic, honeycomb-like mass in segment 8, consistent with an aggregate of dilated biliary ducts and intermingled normal hepatic parenchyma that is best demonstrated by the MRI (Fig. 2). Specific features that distinguish MBH from other liver masses such as hepatocelluar carcinoma include its tubulocystic appearance with interspersed normal hepatic tissue, a honeycomb-like appearance and the more common occurrence at the periphery rather than centrally.1

Pathologic examination of the surgically resected specimen revealed characteristic findings diagnostic of MBH: a circumscribed lesion with variably dilated cysts comprised of large caliber ducts and periductal glands within dense fibrous tissue (Fig. 4b and c), bile-like material within some ducts (Fig. 4d), no protrusion from the liver surface, and no clear association with the falciform ligament.4 Some pathologic findings of the tumor in this case were distinct from those previously reported, including variably sized macroscopic and microscopic islands of hepatic parenchyma within fibrous tissue that were not just at the periphery, but also in the center of the lesion. Two prior cases denote hepatic parenchyma within fibrous tissue between ducts but radiologic images in those cases implied that such intermingled hepatic parenchyma only occurred at the tumor periphery. Of interest, these two prior cases were part of a three case series where two did not protrude from the liver surface and appeared to be in more peripheral but intrahepatic locations.1 Entrapped hepatic parenchyma may therefore be more frequently observed in intrahepatic variants of this lesion or, given that no other reports mentioned the presence of hepatocytes within this lesion, variations in tumor growth and composition are also possible.1–5 Many cystically dilated ducts showed attenuated linings where epithelial cells appeared more cuboidal than columnar; in some ducts, the epithelium appeared flat enough to mimic mesothelial cells of the liver capsule (Fig. 4a).

Diagnosing MBH on the original needle biopsies proved to be very difficult due to limited sampling of the lesion and heterogeneity in distribution of the tumor components. Since entrapped hepatic parenchyma was present throughout, this was originally interpreted as liver parenchyma that was not part of the lesion. Second, some cystically dilated ducts showed attenuated epithelium that was confused with the peritoneal lining of the liver capsule. Third, only a rare focus showed the characteristic periductal glandular component. We infer that these three complicating factors were what lead to the interpretation of some of the large ducts surrounded by dense fibrous tissue as non-lesional, large caliber portal tracts, or possibly representing partial sampling of a biliary adenofibroma. In retrospect, such dense fibrous tissue and large caliber bile ducts in a peripheral, subcapsular location would be unusual for non-lesional liver parenchyma and features typical for biliary adenofibroma, specifically microcystic, more closely spaced, tubuloglandular elements with apocrine snouts separate by thin fibrous bands, are not seen.6 Given these challenges, a definitive diagnosis of MBH based on the needle core biopsies alone would have been extraordinarily difficult.

Early studies with immunohistochemistry demonstrated that the biliary components of this lesion (periductal glands and large caliber ducts) are positive for CK7, CK19 and variably positive for MUC1.4 While these markers were helpful in confirming a biliary immunophenotype in the glandular elements of the lesion, they are unlikely to be of assistance in clinical practice, as none of the above immunohistochemical stains can differentiate neoplastic from benign glands or reliably separate MBH from other entities in the differential.6 Future studies with novel markers may yet reveal a characteristic immunohistochemical phenotype or molecular genotype.

4. Conclusion

The diagnosis of MBH is challenging and requires a keen awareness of this entity. The radiologic and pathologic findings are distinctive and additional sampling in this case, potentially by intraoperative frozen section, may have led to an earlier diagnosis. The lack of recurrence reported in previous cases, along with the lack of tumor spread or metastasis, suggests that this is a benign condition. In this case, given the patient's symptoms, resection likely would have been performed regardless, however if a similar, asymptomatic lesion were detected in the future, it may be reasonable to simply observe the patient with serial imaging. Given that all of the reported cases underwent resection shortly after diagnosis, the natural history of this tumor's growth is unknown and remains a question to be answered.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and case series and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request.

Conflict of interest

Dr. Yee has received research support funding from Optimer Pharmaceuticals in the past (unrelated to this case/manuscript).

Funding

None.

Ethical approval

None.

Author contributions

Dr. Beard assisted in the patient's surgery and wrote and edited the manuscript.

Dr. Yee was the pathologist for the case and provided the pathology images, interpretation and commentary. Dr. Mortele was the radiologist for the case and provided the radiology images, interpretation and commentary. Dr. Khwaja was the patient's surgeon and contributed to the revisions and direction of the manuscript.

Key learning points

-

•

Increased awareness of a rare tumor–multicystic biliary hamartoma.

-

•

Knowledge of diagnostic pitfalls and difficulties.

-

•

Questions still remain regarding the natural history and optimal management of this entity.

References

- 1.Ryu Y., Matsui O., Zen Y., Ueda K., Abo H., Nakanuma Y. Multicystic biliary hamartoma: imaging findings in four cases. Abdom Imaging. 2010;35(5):543–547. doi: 10.1007/s00261-009-9566-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Song J.S., Noh S.J., Cho B.H., Moon W.S. Multicystic biliary hamartoma of the liver. Korean J Pathol. 2013;47(3):275–278. doi: 10.4132/KoreanJPathol.2013.47.3.275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kai K., Takahashi T., Miyoshi A., Yasui T., Tokunaga O., Miyazaki K. Intrahepatic multicystic biliary hamartoma: report of a case. Hepatol Res. 2008;38(6):629–634. doi: 10.1111/j.1872-034X.2007.00314.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zen Y., Terahata S., Miyayama S., Mitsui T., Takehara A., Miura S. Multicystic biliary hamartoma: a hitherto undescribed lesion. Hum Pathol. 2006;37(3):339–344. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2005.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kobayashi A., Takahashi S., Hasebe T., Konishi M., Nakagohri T., Gotohda N. Solitary bile duct hamartoma of the liver. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2005;40(11):1378–1381. doi: 10.1080/00365520510023387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Varnholt H., Vauthey J.N., Dal Cin P., Marsh Rde W., Bhathal P.S., Hughes N.R. Biliary adenofibroma: a rare neoplasm of bile duct origin with an indolent behavior. Am J Surg Pathol. 2003;27(5):693–698. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200305000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]