Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Patients with combined esophageal atresia (EA), tracheoesophageal fistula (TEF), and duodenal atresia (DA) pose a rare management challenge.

PRESENTATION OF CASE

Three patients with combined esophageal atresia (EA), tracheoesophageal fistula (TEF), and duodenal atresia safely underwent a staged approach inserting a gastrostomy tube and repairing the EA/TEF first followed by a duodenoduodenostomy within one week. None of the patients suffered significant pre- or post-operative complications and our follow-up data (between 12 and 24 months) suggest that all patients eventually outgrow their reflux and respiratory symptoms.

DISCUSSION

While some authors support repair of all defects in one surgery, we recommend a staged approach. A gastrostomy tube is placed first for gastric decompression before TEF ligation and EA repair can be safely undertaken. The repair of the DA can then be performed within 3–7 days under controlled circumstances.

CONCLUSION

A staged approach of inserting a gastrostomy tube and repairing the EA/TEF first followed by a duodenoduodenostomy within one week resulted in excellent outcomes.

Keywords: Esophageal atresia, Tracheo-esophageal fistula, Duodenal atresia, Surgical management

1. Introduction

The incidence of esophageal atresia (EA) is approximately 1 in 3000 live births. It is often associated with other anomalies such as vertebral anomalies, anal atresia, cardiovascular anomalies, tracheoesophageal fistula (TEF), renal anomalies, limb defects (VACTERL). A large population study revealed that 46% of TEF patients have at least one other VACTERL malformation.1

Surgical therapy of the TEF is evolving, with open thoracic ligation being the gold standard, however thoracoscopic ligation is increasingly being performed.2–4 Repair of the EA depends on the distance between the proximal and distal pouch: For short gap EA, primary repair is the preferred approach. For long gap EA the Foker technique with axial traction or the Kimura advancement with extrathoracic spit fistula (SF) are surgical options.5 However, a recent study from the University of Southern California, Los Angeles reported that in very low-birth-weight infants (<1500 g) a staged repair of EA/TEF with initial TEF ligation and delayed primary EA repair resulted in fewer anastomotic complications and decreased morbidity.6

Duodenal atresia is a major etiology of congenital intestinal obstruction. It occurs in approximately 1 in 6000–10,000 live births and is associated with an approximately 5% mortality and long-term complications.7 Duodenal atresia (DA) is present in only about 3–6% of EA patients.8,9

The combined presence of TEF, EA and DA presents several management challenges. On one hand, the presence of TEF predisposes the patient to respiratory compromise from aspiration. TEF also fills the stomach with air that cannot traverse through the rest of the gastrointestinal tract due to the DA. This gastric distension also cannot be decompressed with a nasogastric tube due to the EA. Which condition should be addressed first, and should the defects be repaired together or in a staged fashion? Due to the rare occurrence of having all three anomalies, no consensus exists regarding the optimal treatment strategy for this complicated patient population. Studies pertaining to those questions include patients that underwent surgery as along as 40 years ago. This case series presents our management strategy and patient outcome in the current era (Table 1).

Table 1.

Overview of patient characteristics and tabular hospital course.

| Patient #1 | Patient #2 | Patient #3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Length of stay | 21 days | 25 days | 13 days |

| Gender | Male | Female | Male |

| Birth weight (g) | 1388 | 2153 | 1924 |

| Weight at time of discharge (g) | 1660 | 2374 | 2176 |

| Gestational age | 34 weeks | 35 weeks | 33 weeks |

| Prenatal diagnosis | Polyhydramnios, double bubble, twin B | Polyhydramnios, double bubble | polyhydramnios, premature rupture of membrane |

| Cardiac condition | Misaligned ventricular septal defect, right-sided aortic arch | Atrioseptal defect | None |

| Other associated conditions/anomalies | Intrauterine growth retardation, large misaligned ventricular septal defect, GERD, hyperbilirubinemia | Sacral dimple, atrioseptal defect | Hyperbilirubinemia, malrotation, left undescended testicle, |

| Side of aortic arch | Right | Left | Left |

| First surgery | DOL#1 Gastrostomy tube placement, bronchoscopy, right posterior lateral thoracotomy, ligation of tracheoesophageal fistula, repair of esophageal atresia, right chest tube |

DOL#2 Gastrostomy tube placement, bronchoscopy, right posterior lateral thoracotomy, ligation of tracheoesophageal fistula, repair of esophageal atresia, right chest tube |

DOL#2 Gastrostomy tube placement, bronchoscopy, right posterior lateral thoracotomy, ligation of tracheoesophageal fistula, repair of esophageal atresia, right chest tube |

| Second surgery | DOL#4 Exploratory laparotomy: duodenoduodenostomy |

DOL#7 Exploratory laparotomy: duodenoduodenostomy | DOL#7 Exploratory laparotomy: malrotation duodenoduodenostomy, LADD's procedure |

| Enteral feeds started | DOL#5 | DOL#13 | DOL#11 |

| Post-OP course | DOL#7 extubated DOL#14 chest tube removed | DOL#10 extubated DOL#16 chest tube removed | DOL#8 extubated DOL#13 chest tube removed |

| Complications | None | None | Tracheomalacia |

| Follow-up information | 12 months: tolerating feeds, intermittent respiratory distress | 2 years: no problems | 2 years: no problems |

2. Methods

The study was approved by the Tufts Health Sciences Campus Institutional Review Board (IRB#10488). Medical records of three patients with combined TEF/EA and DA from 2010 to 2012 treated at the Floating Hospital for Children at Tufts Medical Center were reviewed.

3. Patients

3.1. Patient 1

The patient was one of a twin gestation (mono-di) after in vitro fertilization. On prenatal ultrasound, the patient was noted to have a double bubble and polyhydramnious with concerns for duodenal atresia. The patient was delivered via c-section at 34 weeks due to nonreassuring heart rate tracings with decelerations and weighing 1388 g at birth. His Apgar scores were 8 at one minute and 9 at five minutes. His anus was patent, and his renal ultrasound was within normal limits. Postnatal echo showed a misaligned ventricular septum and a right-sided aortic arch. Chest and abdominal X-rays revealed the presence of EA/TEF and DA without any vertebral anomalies (Fig. 1A).

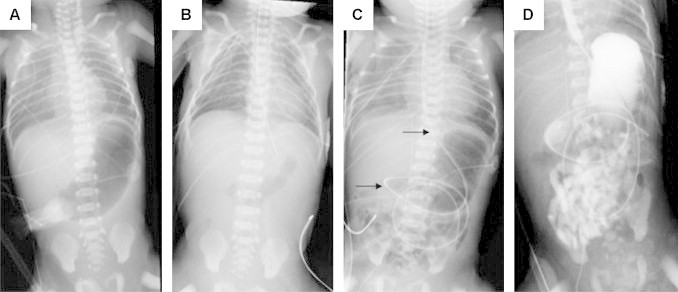

Fig. 1.

X-ray series of patient #1. (A) Prior to surgery with distended stomach and nasogastric tube in the upper esophageal pouch. (B) After gastrostomy tube placement, repair of TEF and EA, and insertion of a nasogastric tube. (C) Two days after DA repair. Arrows mark long NG tube. (D) Upper GI study with patent esophageal conduit and opacification of the small bowel without signs of anastomotic leakage.

On day of life (DOL) #1 the patient was taken urgently to the operating room first for placement of a gastrostomy tube (Malecot, 10 Fr) followed by bronchoscopy, right posterior lateral thoracotomy, ligation of the tracheoesophageal fistula, and primary repair of esophageal atresia. Due to an iatrogenic pleural defect an intrapleural instead of an extrapleural chest tube was inserted in the right chest (Fig. 1B). The patient was kept intubated, and on DOL#4 the patient underwent exploratory laparotomy and duodenoduodenostomy (Fig. 1C). A nasojejunal feeding tube was placed during the DA repair.

The patient was extubated on DOL#7, and enteral feedings were begun via a nasojejunal tube on DOL#6. As oral feeding was increased, feedings via the nasojejunal tube was decreased. The patient reached full volume oral feeds on DOL#16 when the nasojejunal tube was removed. The chest tube was removed on DOL#14. When the patient was discharged on DOL#21, he weighed 1660 g. At the three-month follow-up the patient weighed 3460 g. At one year, the patient was tolerating enteral feedings with only intermittent respiratory distress or reflux.

3.2. Patient 2

The patient was a female delivered at 35 weeks via vaginal delivery and weighed 2153 g. Apgar scores were 7 and 8 at one and five minutes, respectively. A prenatal ultrasound demonstrated polyhydramnios and a double bubble. The initial chest and abdominal X-rays showed no vertebral anomalies but a distended stomach, suggesting duodenal obstruction. An inability to pass a nasogastric tube confirmed the presence of EA and TEF. Her anus was patent, and the renal ultrasound was within normal limits.

A cardiac echo revealed a left sided aortic arch and an atrioseptal defect. On DOL#2 the patient went to surgery for placement of a 12 Fr gastrostomy tube, followed by a right thoracotomy with ligation of the TEF, and primary repair of the EA. An extrapleural chest tube was also placed in the right chest. The patient was kept intubated, and on DOL#8 the patient returned to the OR for duodenoduodenostomy to address the annular pancreas and duodenal atresia. The patient was extubated on DOL#10, and the chest tube was removed on DOL#16. On DOL#13 the patient had a swallow study that showed no esophageal or duodenal leakage. On DOL#14, enteral feeds were initiated and by DOL#22 the infant received full volume oral feeds. The patient was discharged on DOL#25 weighing 2374 g. At the six-month follow-up appointment, the patient showed adequate growth, without signs of reflux or respiratory problems. The patient remained well at two years with appropriate weight gain.

3.3. Patient 3

The patient was a premature male (33 weeks, 5 days) who weighed 1924 g at birth after vaginal delivery. Apgar scores were 8 and 9 at one and five minutes, respectively. The pregnancy was complicated by advanced maternal age, and prenatal ultrasound demonstrated polyhydramnios. He was pink and vigorous on room air. His anus was patent and he had an undescended left testicle.

A nasogastric tube could not be placed, and an abdominal X-ray showed a distended stomach. There was no air noted in the distal bowel and there was malformation of the 6th lumbar vertebra. The patient also required phototherapy for hyperbilirubinemia. On DOL#2 the patient first underwent an open gastrostomy tube placement followed by a right thoracotomy, with extrapleural ligation of the TEF and primary EA repair. An extrapleural right chest tube was inserted. The patient remained intubated, and on DOL#7 the patient underwent a duodenoduodenostomy and a Ladd's procedure for annular pancreas and malrotation. The patient was extubated on DOL#8 and the chest tube was removed on DOL#13. Oral feedings were initiated on DOL#12 after the swallow study revealed no esophageal or duodenal leakage. The patient was discharged on DOL#13 weighing 2176 g. At age 7 months the patient exhibited mild symptoms of reflux and noisy breathing. These symptoms improved significantly and resolved by 13 months of age. The patient remained well at two years.

4. Discussion

In all our patients polyhydramnios was diagnosed during pre-natal ultrasound evaluation. Each of our patients underwent a staged repair: during the first operation, a gastrostomy tube was inserted first to allow gastric decompression, then the TEF-EA repair was undertaken via a posterolateral thoracotomy using an extrapleural approach. The DA repair was performed within one week afterwards, after routine performance of a contrast study. None of the patients suffered significant pre- or post-operative complications, and none of the associated anomalies compromised the patient's recovery. There was no mortality. The average hospital stay was 20 days. Our follow-up data (between 12 and 24 months) suggest that all patients eventually outgrow their reflux and respiratory symptoms.

In 1981, Spitz et al. described the management of 18 infants with combined TEF/EA and DA. The study reported a 33% early survival rate. The authors also recommended a staged repair addressing gastric decompression and EA/TEF first, followed by duodenoduodenostomy a few days later.8

A more recent study from the Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto that included 17 patients with combined defects between the 1971 and 2000 reported an overall 88% survival rate. The group recommended a staged repair preferably within one week. Of note, the majority of deaths resulted from failure to initially diagnose the duodenal atresia.10

In a 2007 case series from Royal Children's Hospital, Melbourne, three patients with combined TEF, EA, and DA were reported. One patient underwent simultaneous EA/TEF and DA repair on DOL#1. Another patient developed respiratory distress and underwent only a decompressing gastrostomy and feeding jejunostomy on DOL#3. This patient ultimately expired on DOL#11. The third patient was a 28-week old female twin (808 g) diagnosed with EA/TEF and underwent repair on DOL#2. Increasing abdominal distension led to an exploratory laparotomy on DOL#21. DA could not be ruled out at that time. The infant expired on DOL#42 and a post-mortem diagnosis of DA was made.11 This underlines again that patients with TEF and EA should undergo early evaluation for DA as failure to diagnose may lead to devastating outcomes.10,11

A case series from the Children's Hospital, Randwick, Australia included 10 patients (1976–2000) with combined TEF, EA, and DA. The authors concluded that a primary simultaneous repair of these anomalies without a gastrostomy was adequate without notable increase in morbidity or mortality compared to a staged approach. In addition, the authors argue that the use of the Kimura diamond anastomosis for DA allows for early functioning of the duodenal anastomosis and may preclude the use of a gastrostomy in patients with EA and DA.12 Five of nine patients had anastomotic strictures, three of nine patients required fundoplication due to severe gastroesophageal reflux disease, one patient had recurrent TEF, and one required tapering of a megaduodenum.12

Holder et al. in a case series study from Mercy Hospital, Kansas City Missouri argued for a repair of the DA first, followed by EA repair after approximately one week. This would allow for return of function at the duodenal anastomosis and protect it from alkaline reflux.13

Based on our experience we would recommend a staged approach of two surgeries. During the first surgery, the gastrostomy tube is placed prior to ligation of the TEF and repair of the EA. This gastric decompression serves to prevent abdominal distension and subsequently respiratory compromise. Should respiratory compromise be noted due to preferential ventilation of the stomach, the tube can be intermittently clamped until the fistula ligation is completed. Once this emergent issue has been resolved, TEF ligation and EA repair can be safely undertaken with decreased risk of contaminating the chest with gastric contents under pressure. The repair of the DA can then be performed within 3–7 days under controlled circumstances.

Our experience lends validity to the strategy of a staged approach. While our patient number is low and our follow-up information is relatively short, none of our patients suffered significant peri-operative complications that have been described in the literature. At the end of the available follow-up intervals, all patients were able to tolerate enteral feeds without significant sequelae from their congenital conditions or their surgeries.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Funding

None declared.

Ethical approval

This chart review case series has been IRB approved. This IRB approval can be reviewed as per Editor-in-Chief request.

Author contributions

CSN involved in chart review, composition of manuscript. BC involved in editing of manuscript, conceptual planning. CCJ involved in editing of manuscript. WJC involved in editing of manuscript, conceptual planning.

References

- 1.McMullen K.P., Karnes P.S., Moir C.R., Michels V.V. Familial recurrence of tracheoesophageal fistula and associated malformations. Am J Med Genet. 1996;63(June (4)):525–528. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-8628(19960628)63:4<525::AID-AJMG3>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tovar J.A., Fragoso A.C. Current controversies in the surgical treatment of esophageal atresia. Scand J Surg. 2011;100(4):273–278. doi: 10.1177/145749691110000407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ma L., Liu Y.Z., Ma Y.Q., Zhang S.S., Pan N.L. Comparison of neonatal tolerance to thoracoscopic and open repair of esophageal atresia with tracheoesophageal fistula. Chin Med J (Engl) 2012;125(October (19)):3492–3495. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rothenberg S.S. Thoracoscopic repair of esophageal atresia and tracheo-esophageal fistula in neonates: evolution of a technique. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2012;22(March (2)):195–199. doi: 10.1089/lap.2011.0063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sroka M., Wachowiak R., Losin M., Szlagatys-Sidorkiewicz A., Landowski P., Czauderna P. The Foker technique (FT) and Kimura advancement (KA) for the treatment of children with long-gap esophageal atresia (LGEA): lessons learned at two European centers. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2013;23(February (1)):3–7. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1333891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Petrosyan M., Estrada J., Hunter C., Woo R., Stein J., Ford H.R. Esophageal atresia/tracheoesophageal fistula in very low-birth-weight neonates: improved outcomes with staged repair. J Pediatr Surg. 2009;44(December (12)):2278–2281. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2009.07.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Escobar M.A., Ladd A.P., Grosfeld J.L., West K.W., Rescorla F.J., Scherer L.R., 3rd Duodenal atresia and stenosis: long-term follow-up over 30 years. J Pediatr Surg. 2004;39(June (6)):867–871. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2004.02.025. discussion-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Spitz L., Ali M., Brereton R.J. Combined esophageal and duodenal atresia: experience of 18 patients. J Pediatr Surg. 1981;16(February (1)):4–7. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(81)80105-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Andrassy R.J., Mahour G.H. Gastrointestinal anomalies associated with esophageal atresia or tracheoesophageal fistula. Arch Surg. 1979;114(October (10)):1125–1128. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1979.01370340031004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ein S.H., Palder S.B., Filler R.M. Babies with esophageal and duodenal atresia: a 30-year review of a multifaceted problem. J Pediatr Surg. 2006;41(March (3)):530–532. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2005.11.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stark Z., Patel N., Clarnette T., Moody A. Triad of tracheoesophageal fistula-esophageal atresia, pulmonary hypoplasia, and duodenal atresia. J Pediatr Surg. 2007;42(June (6)):1146–1148. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2007.01.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dave S., Shi E.C. The management of combined oesophageal and duodenal atresia. Pediatr Surg Int. 2004;20(September (9)):689–691. doi: 10.1007/s00383-004-1274-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Holder T.M., Ashcraft K.W., Sharp R.J., Amoury R.A. Care of infants with esophageal atresia, tracheoesophageal fistula, and associated anomalies. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1987;94(December (6)):828–835. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]